There were several tantalising games in German football over this weekend, such as Bayer Leverkusen vs Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund‘s match against a resurgent Hertha Berlin. However, the 2. Bundesliga offered a significant encounter of epic proportions as 17th-placed Wehen Wiesbaden hosted Dynamo Dresden.

Wiesbaden weren’t expected to survive at the start of the season, and although the season seems like it will end that way, Wehen have shown to be a tricky side to get past. Dresden have the unfortunate role of playing eight games in June after missing two weeks due to being in lockdown thanks to Covid-19. This tactical analysis looks at the tactics from this entertaining encounter which saw an unlikely 3-2 win for Dresden.

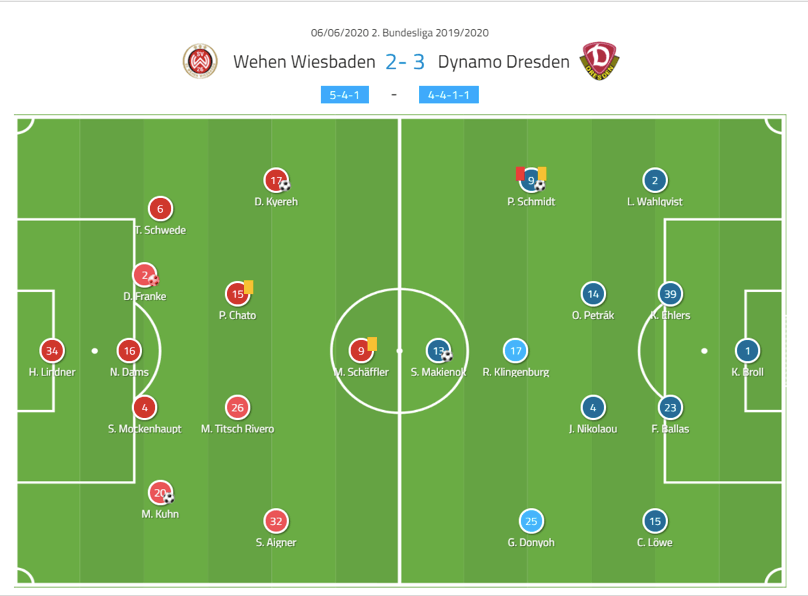

Lineups

Rüdiger Rehm has gained a reputation for producing the wicked and wild when it comes to tactical formations. It’s been suggested that Wiesbaden played in a 5-4-1 (defensive), but in truth, it was more of a 3-3-3-1 which we will explain. From the side that lost at Hamburger SV last weekend, there was just the one change with Tobias Schwede replacing Benedikt Röcker. Schwede played as a wing-back with Dominik Franke moving into the back three.

The return from the two weeks in lockdown had been trying for Markus Kauczinski with defeats to Stuttgart and Hannover. Worryingly, Dresden failed to score in both games. Kauczinski made nine changes to the side that lost in midweek in Hannover. There was almost a brand new defence with Chris Löwe, Kevin Ehlers, and Linus Wahlqvist coming in to replace Niklas Kreuzer, Jannik Müller, and Brian Hamalainen. Dzenis Burnić’s season is over due to injury while Marco Terrazzino, Patrick Ebert, and Sascha Horvath were dropped with Godsway Donyoh, René Klingenburg, and Patrick Schmidt coming in. Alexander Jeremejeff had next to no impact in Hannover, so Simon Makienok led the line.

Wehen’s infamous 3-3-3-1

When you look around the 2. Bundesliga, many teams play similar systems. Quick on the counter-attack, possession-based, or a combination of both depending on the situation. Wehen Wiesbaden plays an entirely different brand of football that the league hasn’t seen, a system which looks crazy on paper and when put into action, it has such an inconsistency in results. Let’s take a look at the Rehm system.

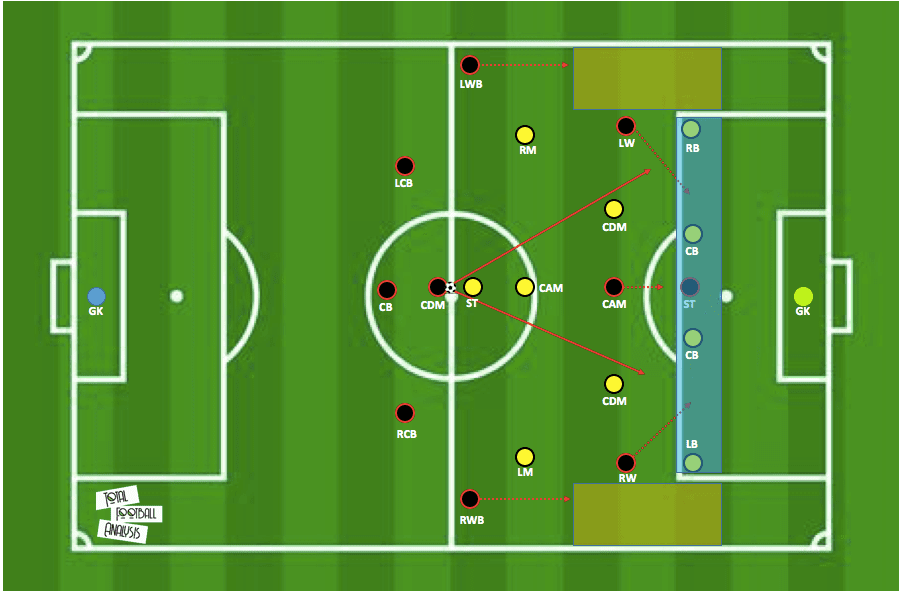

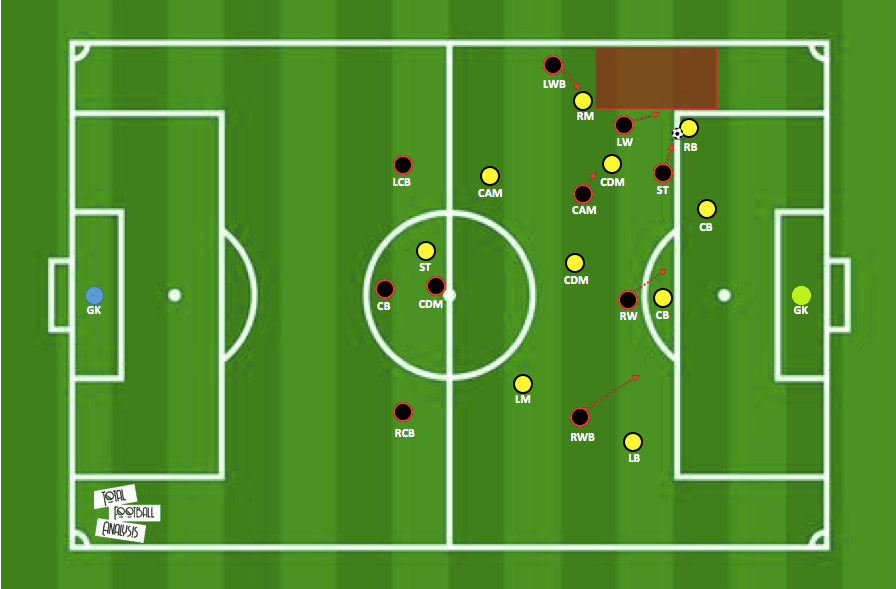

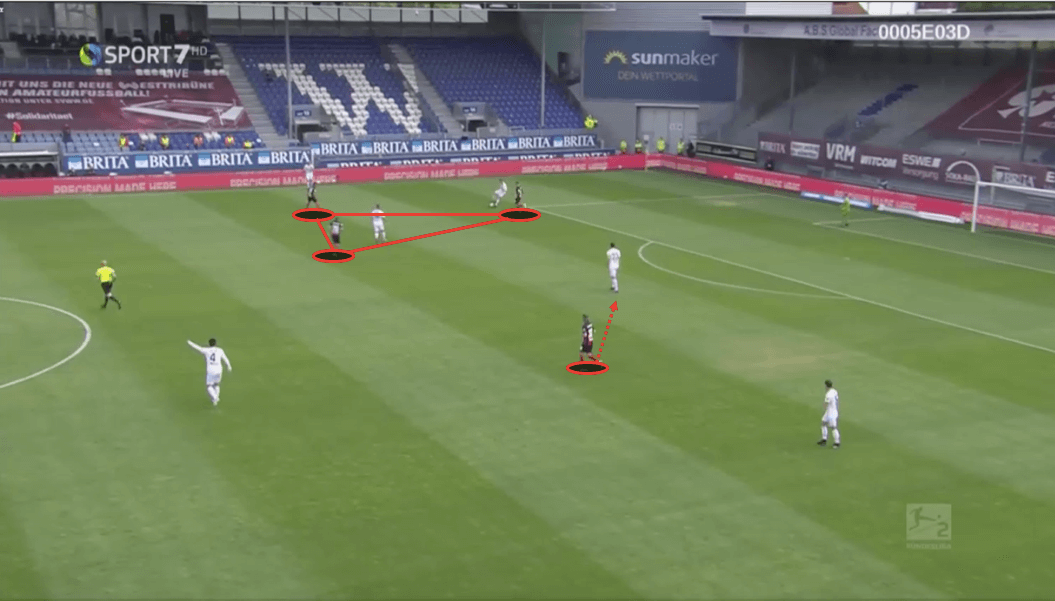

The formation is the 3-3-3-1 and Wiesbaden are the only team to use this formation. It’s heavily intensive on the fluidity of player movement and levels of progression through the use of wide players. Above is a formational table when the number six has possession. The “wing-backs” who operate next to the six will push up past the number 10 into the spaces highlighted. They remain the widest players on the pitch as the attacking wingers move diagonally alongside the striker. There are two ways Wiesbaden will distribute through the number six: long and diagonal to the attacking wingers with the number 10 positioning himself front and centre to receive, or quick movements to play wider to the wing-backs who can cross into the box. The objective of the 3-3-3-1 in attack is level the numbers to the defensive opponent and create chaotic situations.

How about when one of the centre-backs has the ball? Well, three options are available for the playing in possession. The example above has Franke with the ball, he can try and find the number six if he is available and then the essential “quarterback” can play the ball forward. Franke can do the number six’s role and play directly to a cluster of players. Or he can take the space given and drive into the final third. The latter option works exceptionally well when Sascha Mockenhaupt had possession, with ill abandon he would bring the ball forward while Moritz Kuhn continued his wide movements. The issues can come when the centre-back is driving forward and loses the ball, as an overload is created so Wiesbaden can be left exposed if a counter-attacking opportunity is enabled.

This system is used less often in defence with the wing-backs dropping back in most cases to create a back five. Rehm encourages opportunistic pushes forward, and it can seem quite obvious for teams to attack out wide with the centre-backs remaining compact and linear. The image above reveals some of the shape with the attacking four, mostly given license to press.

Wiesbaden plays a nuanced scheme that insists on playing quick, decisively, and with reckless abandonment. In attack, the attempt to overload defences with waves of numbers is exciting. However, the direct approach at times leaves little to the imagination. We see defensively that adopted tactical approach can be exploited quite easily by offensively competent sides.

The impact of Paterson Chato

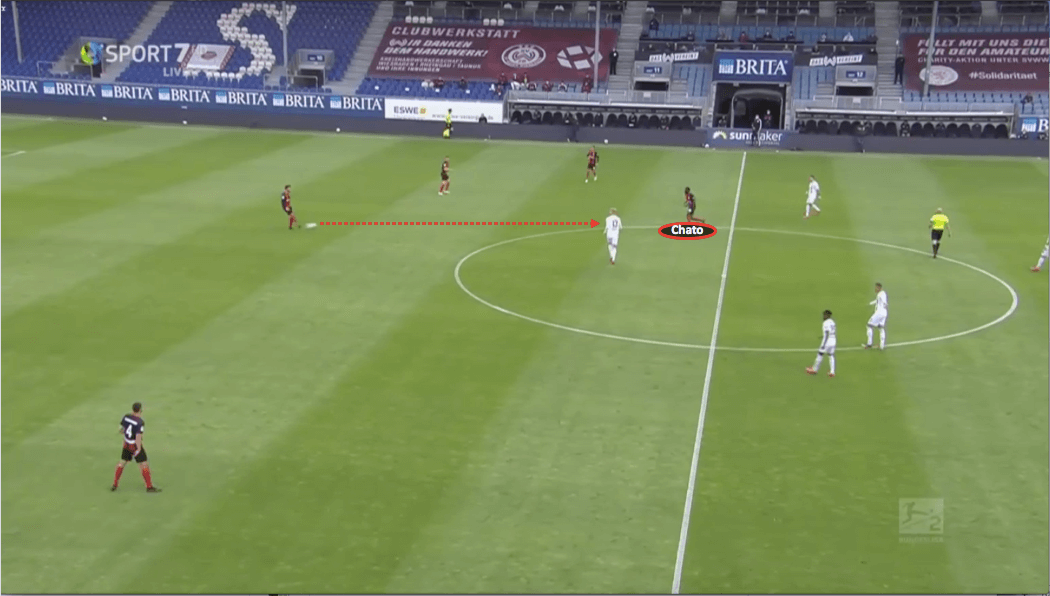

As touched on before, the number six plays a vital role in build play within the unique Wiesbaden set-up. The player enlisted to play this role is 23-year-old Paterson Chato. Chato is an ex Bayer Leverkusen junior who cut his teeth with SportFreunde Lotto in the 3. Liga last season where he made a significant contribution despite the side succumbing to relegation. Wiesbaden brought him in on a free with the Zaire born midfielder featuring 23 times this season. We delve into the importance of Chato’s influence and how Dresden tried to limit his impact on the game.

Chato’s impact was felt in the build-up play, against Dresden the midfielder completed 46 of 52 passes. It was the second-most passes attempted by a Wiesbaden player with only centre-back Dams completing more (58). On most occasions, we will see Chato drop deep to receive from the centre-back core. Once receiving possession, you’ll see Chato play direct and diagonal towards the attacking wingers or striker.

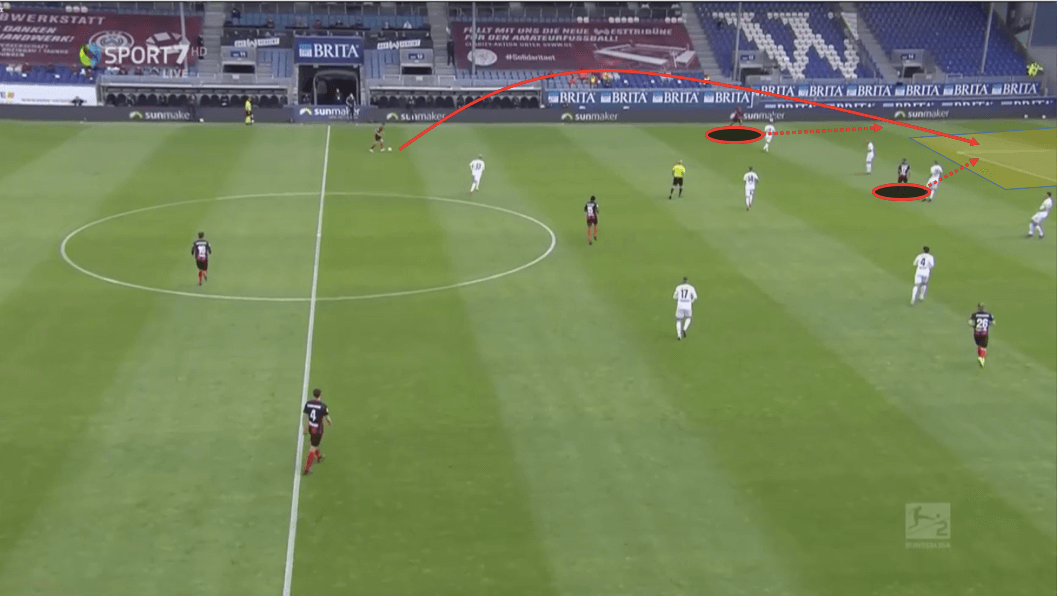

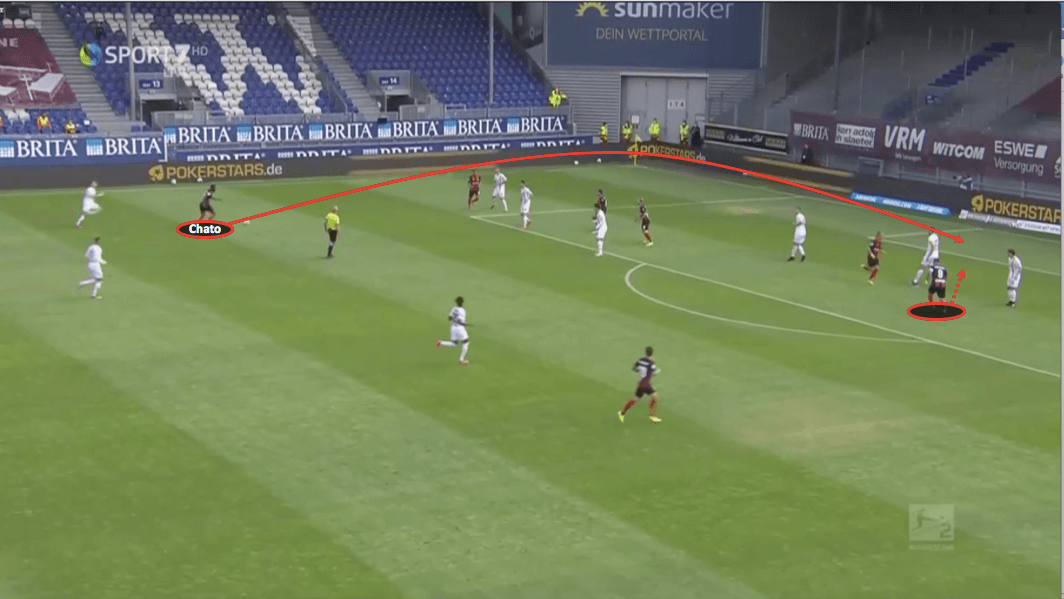

When Chato does get further forward, he is an asset providing long balls to his teammates. On Saturday, Chato completed all four of his long passes against Dresden. In this situation, Chato is afforded time and space and plays an excellent ball to Manuel Schäffler who can’t convert.

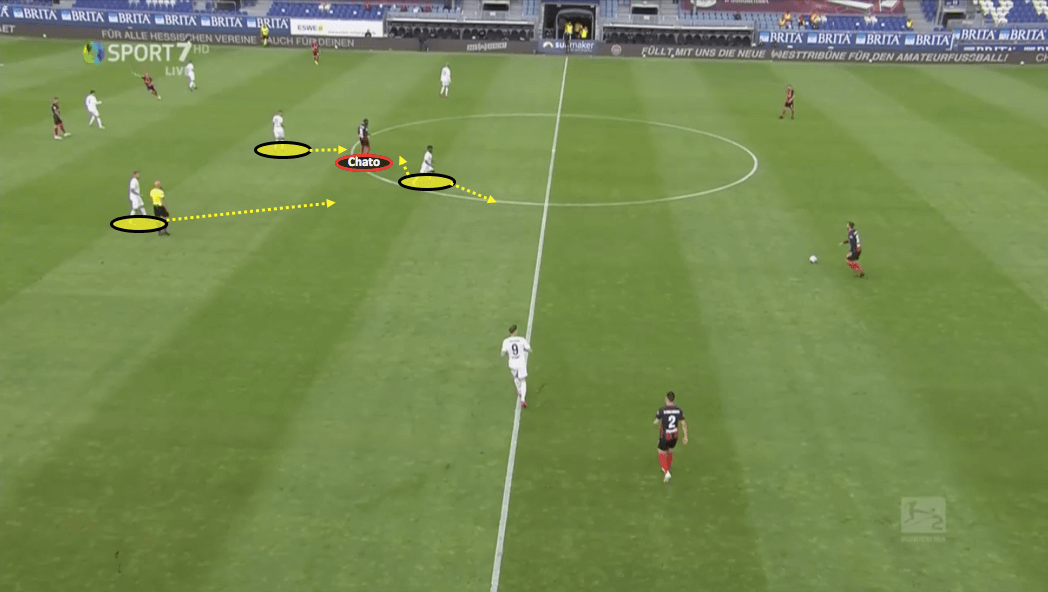

With Chato causing havoc and pulling the strings in the first half, Dresden provided the Wiesbaden midfielder plenty of attention. They did this several ways, namely having the number nine (Makienok) dropping into midfield to intercept the line of sight for Chato. In Australian Rules Football, this is considered as a tagging role and on many occasions in the half, Makienok would be hot on Chato’s heels. If Makienok went out wide, Klingenburg and Schmidt would press towards Chato with Godsway Donyoh playing front. This ensured the avenue to Chato was constantly blocked and forced the Wiesbaden defenders to be more direct in the approach.

Chato’s influence was pivotal in the first half where he made a significant impact. However, when Dresden singled Chato out, his output in the game was minimised. Dresden were able to wrestle some momentum in their favour.

Dynamo’s success from crosses

Entering the game against Wehen, Dresden has had a real issue scoring goals. After 27 outings, Dynamo had managed just 25 goals which is ten worse than opponents Wiesbaden and St. Pauli. The man issue in Dresden hasn’t been the side’s ability to get the ball into the attacking, rather the inability to finish off said chances. In this game, Dresden had great success from crosses with two of the three goals coming thanks to deliveries into the box. This part of the analysis delves into Dresden’s ability to make Wiesbaden pay inside the box.

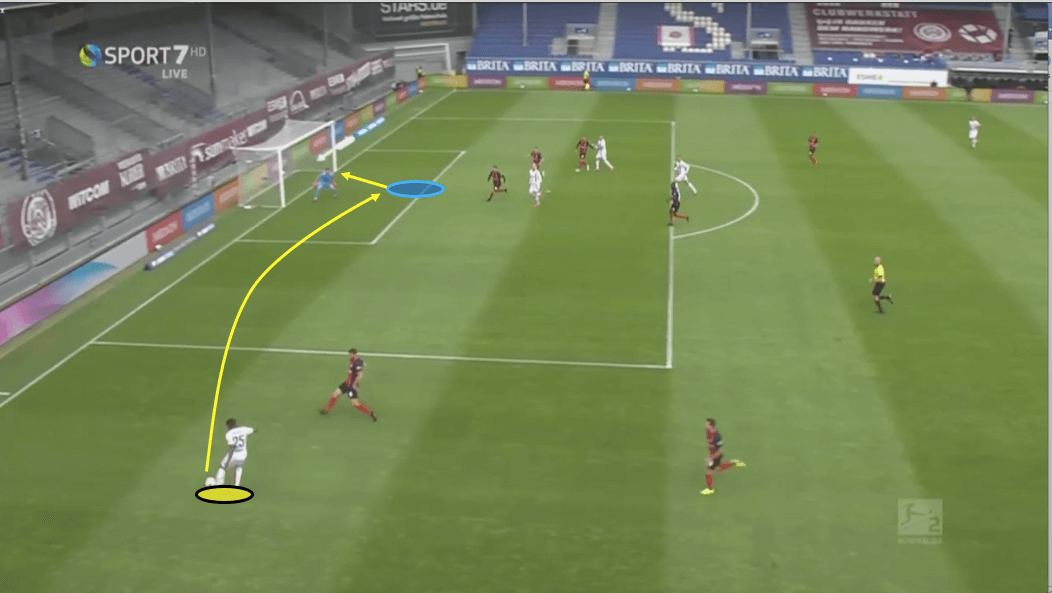

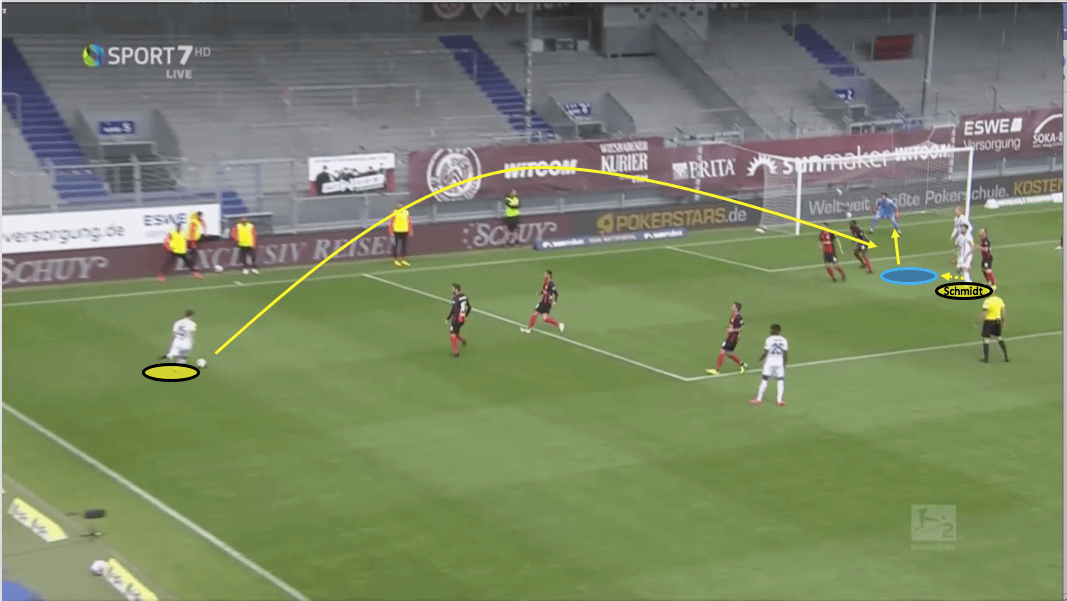

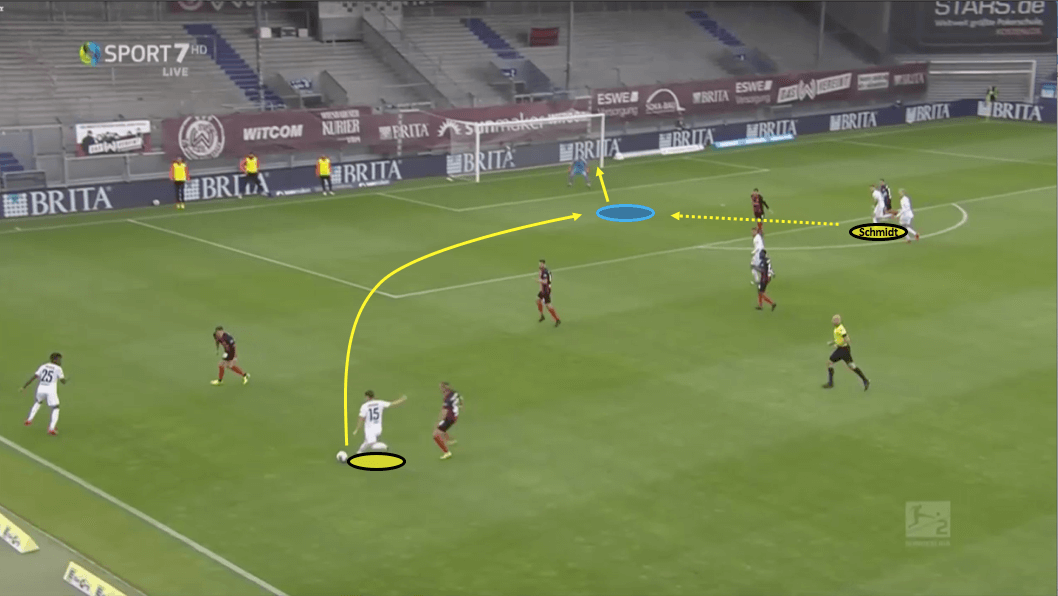

We have three situations to showcase with the first resulting in a goal. An own-goal, however, the way the play is set up and the ability to exploit defensive inadequacy is pivotal in Dresden scoring their first goal since the break. Donyoh is about to play the ball, and structurally Wiesbaden are providing some resistance. Both Schmidt and Makienok are marked, but Klingenburg can run in unchallenged. The cross from Donyoh is at the edge of the six, forcing Heinz Lindner to decide whether to come and claim or stay on his line. Lindner opts to stay on his line. The cross is hit well but missing Makienok’s run to the near post. Yet, Wiesbaden centre-back Franke bundles the ball into his own net. While the delivery didn’t find a teammate, it created the preserved pressure, which led to a catastrophic mistake.

The second example is far more clinical – left-back Löwe has possession and surveying for an option. Wiesbaden have plenty of defensive prospects in the box, but it would seem a number of them haven’t picked up a player. Notably Mockenhaupt and Chato at the near post. The creates a pocket of space for Schmidt, who is already goal-side and has a front position on his opponent. Löwe’s cross comes, and Schmidt’s header is saved by Lindner, a clear sighter of what was to come.

It’s been clear that since joining Dresden on loan from Heidenheim in the winter, Schmidt has been revitalised after playing a cameo role for the Baden-Württemberg side. Four goals heading into this game and he would make it five for the season just before half-time. Löwe crosses from further back, yet the delivery is once again in an area which causes doubt for the goalkeeper. Both Schmidt and Makienok are options, but it’s clear that Schmidt’s run is towards the near post. As the ball comes in, Niklas Dams and Franke are covering Schmidt. Yet the strength and determination to win the header are fantastic, and the finish wasn’t half bad either. From the seven crosses into the box, three led to shots on target. Dresden finally took advantage of the self-made opportunities they created.

Wiesbaden pressing the issue

Wiesbaden isn’t a team known for it’s pressing, yet they possess a system which allows for systematic pressing. In their first season back in the 2. Bundesliga for over ten years, Wiesbaden had previously tried to adopt a more pragmatic defensive approach. What is clear is that hasn’t been working, so against the worst team in the league, Wiesbaden went pressing.

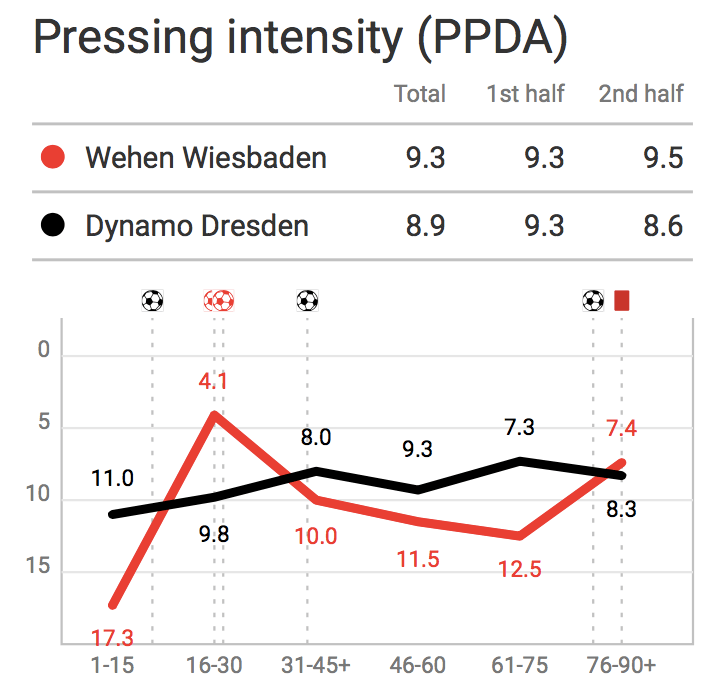

As shown in the Passing Per Defensive Action (PPDA) chart above, Wiesbaden really got their tails up between the 16th and 30th minute of the game. Like a predator stalking its prey, Wehen went for the kill, and as a result, they scored twice and should’ve had a couple more. The 4.1 intensity output is one of Wiesbaden’s highest PPDA of the season.

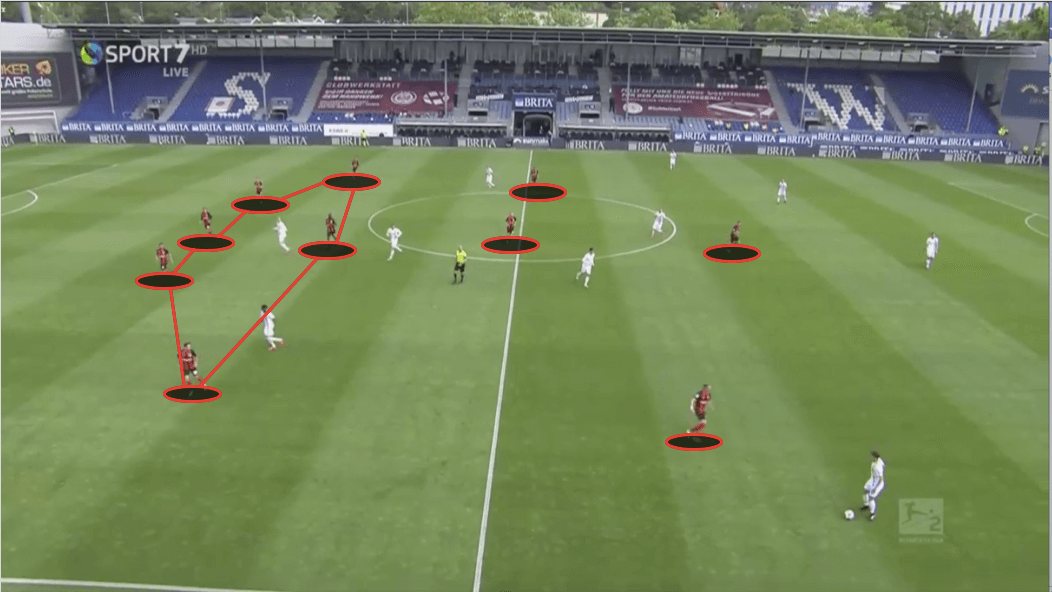

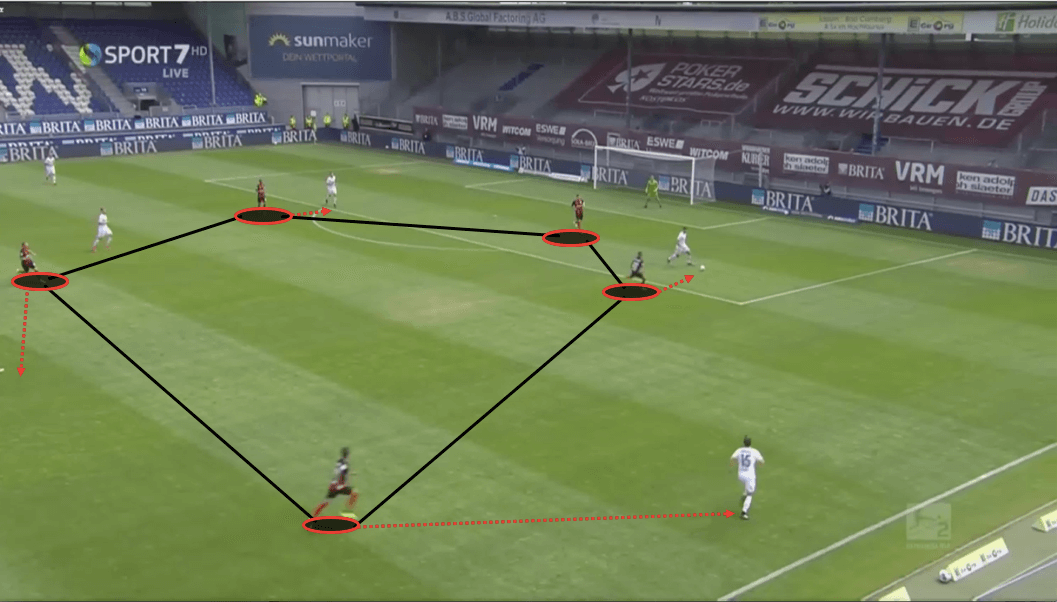

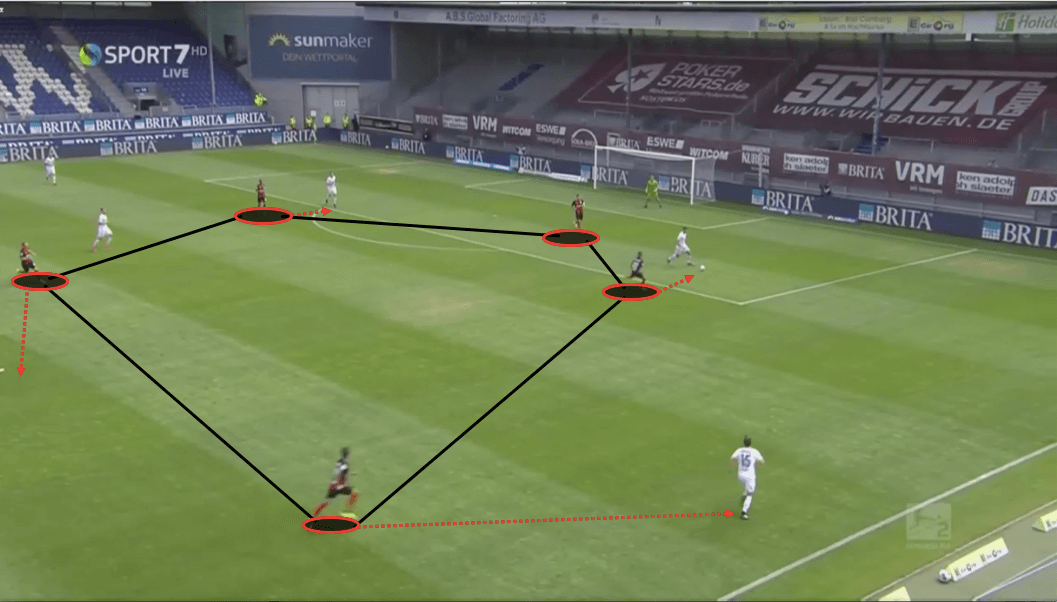

One of the quirks of the 3-3-3-1 formation is the ability to create condensed levels and force mistakes if appropriately applied. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, when Wiesbaden went after the Dresden defence in possession, they were not only able to win possession back, but the additional weight of number counteracted the defensive output of the opponent. The objective for Wiesbaden’s pressing is to win possession but also to force the ball wide and create problematic situations where the only option is backwards. When the right-back has the ball Wiesbaden shift to condense the space. If he goes to his left, the centre-back closest can play centrally to the number six. However, the CAM and the right-winger can close this avenue. It’s a tedious tight rope if your style of play is to move out of defence with the use of short passes. Let’s see this in action.

The first situation showcases how pressing and playing away from your tendencies can benefit the side. With Ehlers on the ball, the striker Schäffler, Marcel Titsch-Rivero, and Daniel-Kofi Kyerah are pressing. Each is marking a player with Schäffler hounding Ehlers. What is clear is Ehlers’ intent to go back to the keeper. However, with the intensive pressing Schäffler disposes of the defender and Wiesbaden can attack. What is critical is that if Dresden loses possession, Wiesbaden will ensure there is no numerical advantage.

Our last example articulates the pressing and unified defensive movement. Florian Ballas has possession for Dresden, and you can see the near minimal options at his disposal. Even a pass back to the keeper is risky. Ballas does have Löwe out wide, but when the ball is delivered, he will be under immense heat from the right wing-back Kuhn. Wiesbaden wants Dresden to go wide and the moment of indecisiveness leads to Stefan Aigner winning the ball and a three-v-two situation inside Dresden’s box.

It’s almost a shame that Wiesbaden doesn’t often press, in the 15 minutes or so when Wehen went hammer and tongs, and you would’ve forgotten that they were sitting 17th. Rehm’s side were superb structurally and was able to force countless Dresden mistakes in their defensive third.

Conclusion

Football can be a strange temptress when one team dominates a game from minute and finds a way to lose – it can be a bitter pill to swallow. And it is one which Wiesbaden will have to deal with, as Wehen did a lot of good in this game but failed to put Dresden away before half time which was the catalyst to their demise.

Dresden can count their lucky stars to steal victory at the BRITA-Arena when they really should’ve lost. Yet, deep into the second half, striker Makienok came up big to secure a vital win for Dynamo. Sitting a point behind Wehen Wiesbaden and three behind Karlsruhe in the relegation play-off spot with two games in hand, Dresden could very well run the gauntlet and at least gain temporary survival.

Comments