The shortlist for the FIFA’s best men’s coach award is routinely dominated by Europe-based coaches, with this year’s final three being comprised of Premier League duo Pep Guardiola of Manchester City and the winner Thomas Tuchel of Chelsea, along with European Championship-winning Italy boss Roberto Mancini.

Meanwhile, Liverpool mastermind Jürgen Klopp came away with the award in both of the two years preceding this one.

These coaches are undoubtedly some of the best in world football today and, as such, are well deserving of their accolades.

However, while the pinnacle of world football is clearly the top of the European game in 2022, excessive Eurocentrism shouldn’t prevent outstanding coaches plying their trade in other parts of the world from receiving the global recognition they too have earned for their current coaching performances from FIFA — a global organisation.

Take Al Ahly boss Pitso Mosimane, for example.

He’s guided his team to two straight CAF Champions League titles and an impressive third-place finish in the 2021 FIFA World Club World Cup — earning a medal at this competition for the continent for the first time since 2013.

Despite this, the South African remains somewhat out of the spotlight as far as FIFA’s top showcases are concerned, with the 57-year-old himself recently explaining his view on the matter as: “It is not only Africa [that’s overlooked]. It is as though it does not mean as much when you win in the competitions that do not generate the most money, that do not have the biggest audiences”, via The New York Times.

To read more about Al Ahly’s exceptional coach, Pitso Mosimane, I’ve written about the South African here for Total Football Analysis: Mastermind Mosimane: Four fundamental tactical features fueling Egypt’s relentless Red Devils – tactical analysis.

Another non-Europe-based coach who’s delivered on an exceptional level of late is Palmeiras boss, Abel Ferreira.

Indeed, the Portuguese coach has worked in Europe in the past, having previously led Braga and PAOK — and done a pretty impressive job with both clubs.

However, his greatest success so far has come at Brazilian side Palmeiras, as Ferreira has managed to lead his side to one Copa do Brasil (2020) and, most impressively, back-to-back Copa Libertadores’ (2020 and 2021).

In this tactical analysis piece, I aim to provide some insight into Ferreira’s preferred style of play, strategy and tactics via analysis of his glorious Palmeiras side.

I hope that this analysis shines a light on how the 43-year-old masterminded two straight Copa Libertadores titles, helping Palmeiras to become the first team to achieve this difficult feat since Boca Juniors did so in 2000 and 2001 under Carlos Bianchi — Copa Libertadores’ most successful ever coach.

Abel Ferreira Formations

Under Ferreira, Palmeiras haven’t been an extremely aggressive side without the ball.

They ended the 2021 Brasileirão Série A with a relatively average PPDA of 10.71, indicating they press with relatively average intensity, a below-average number of defensive duels (63.02 per 90 — they do, however, have an above-average success rate of 58.2%) and a fairly low number of interceptions (34.12 per 90).

In Copa Libertadores last season, Palmeiras had a PPDA of 16.06 — which ranked quite high among Copa Libertadores sides, indicating that they pressed with relatively low intensity in that competition.

These numbers probably won’t come as much of a surprise if you’ve been watching Palmeiras, as they don’t tend to try and win the ball back right from opposition goal-kicks, in general.

They tend to be more passive at the beginning of an opposition move, with their line of engagement typically sitting around the halfway line.

Up until the opposition reaches that point, Ferreira is seemingly happy for his players to drop off and ultimately end up in a compact mid-block.

Then, from this point, it’s common to see Palmeiras perhaps start to defend with a bit more urgency.

Ferreira primarily used two main shapes in 2021 — the 5-4-1/5-2-3 and the 4-2-3-1.

Regardless of which shape they played with, their defensive strategy and tactics largely remained consistent, so most of what I’ll discuss here remains true regardless of shape.

However, I will show examples of the team lined up in both a 5-4-1/5-2-3 and a 4-2-3-1.

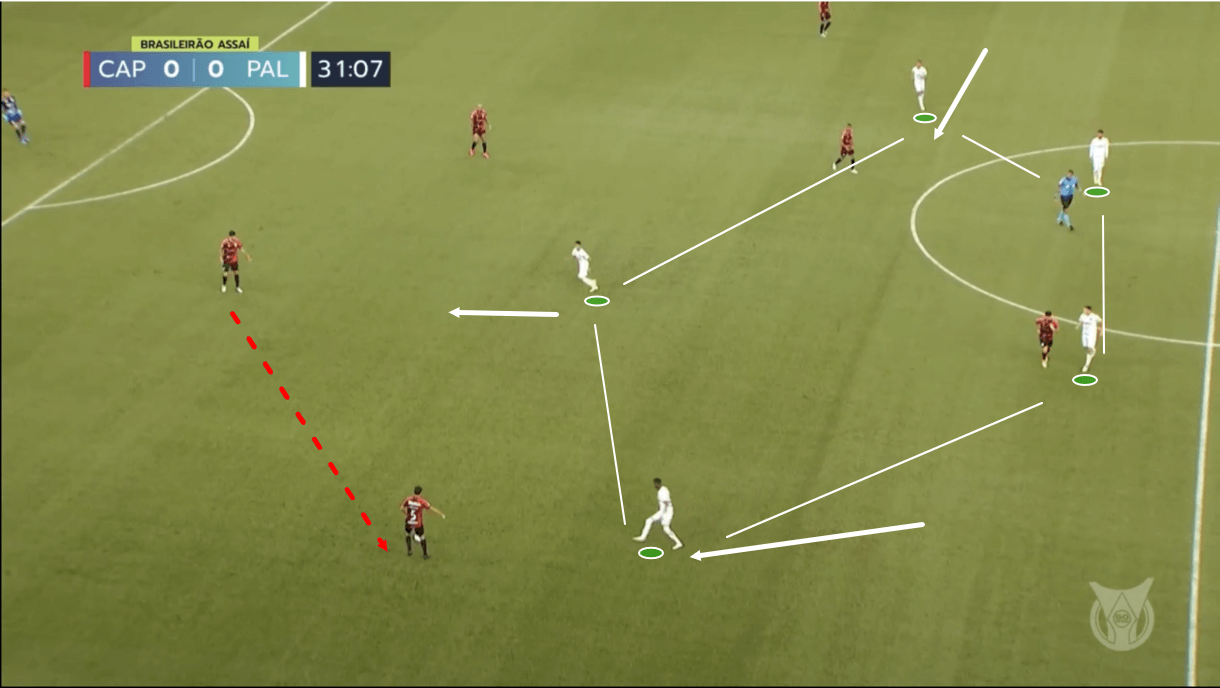

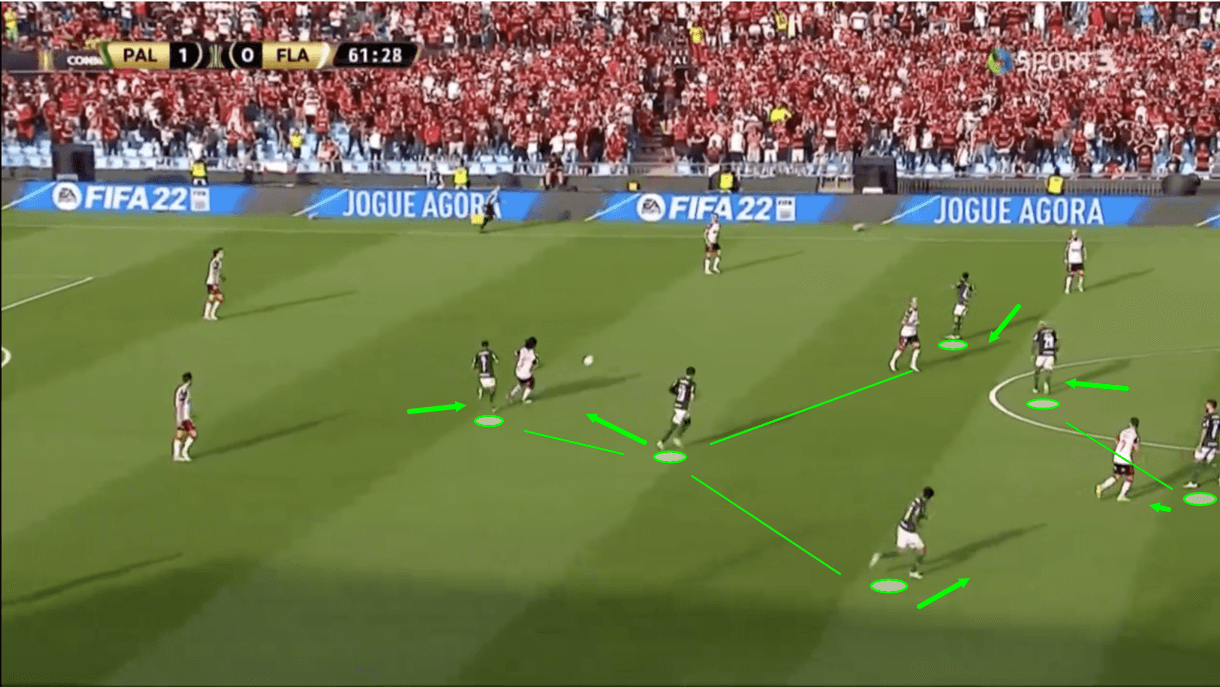

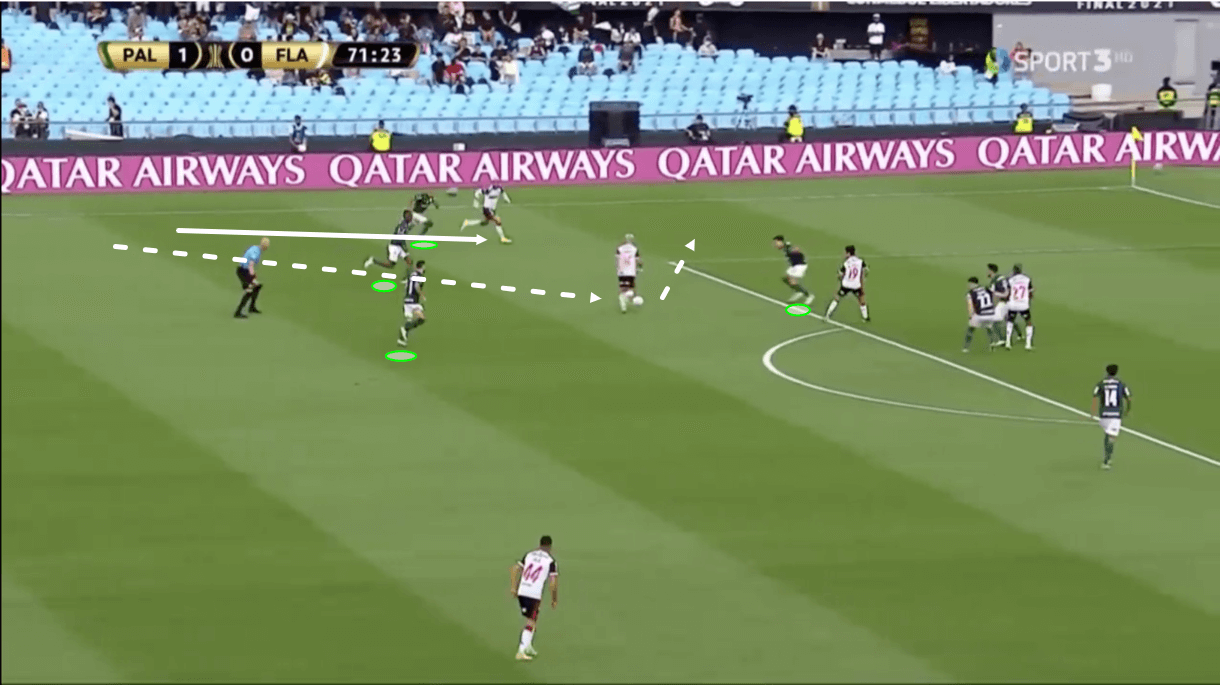

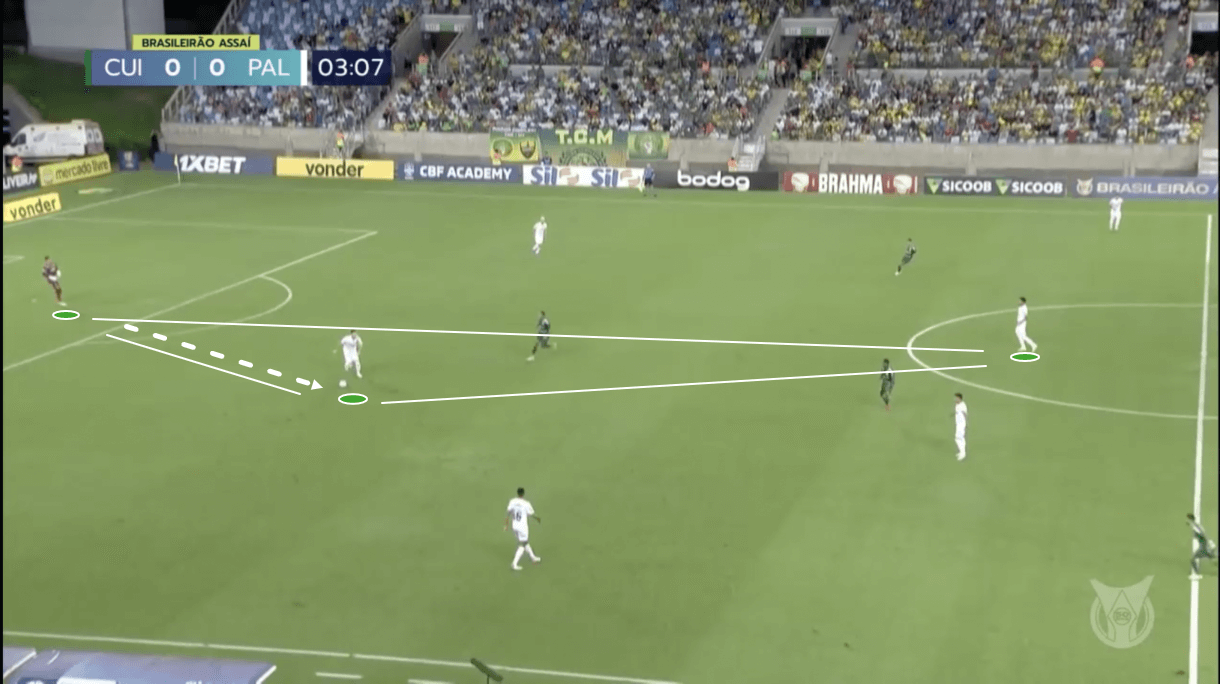

Firstly, the passage of play shown in figures 1-3 provides an example of Palmeiras playing in the 5-2-3/5-4-1 shape.

The placement of the wingers changes depending on how far the opposition has progressed upfield, which is where the difference between 5-2-3 and 5-4-1 becomes apparent.

Further upfield, as we see Palmeiras in figure 1, their wingers sit higher and the shape is more of a 5-2-3 but in deeper areas, the wingers drop deeper to turn this shape into more of a 5-4-1.

Palmeiras operate with a zonal marking system that’s position-oriented and generally quite organised.

The aim here is almost to create something of a fortress around the centre of the pitch, covering all passing angles into midfield and keeping the opposition out of this area.

This is clearly illustrated in figure 1, where the two central midfielders provide a base to the structure just in front of the halfway line, while the three players further upfield cut the passing lanes into midfield from the opposition backline.

In figure 1, we also see how Palmeiras react as the opposition send the ball out to the right-back from the right centre-back.

The ball-near winger closes the receiver down while still remaining in the passing lane between the receiver and the nearest midfielder, the ball-far winger comes narrower to basically add extra protection to midfield and cover the ball-far midfielder while still retaining access to the ball-far wing in case the switch is played, and the centre-forward begins to close down the ball-near centre-back on seeing that with his forward passing options cut off, the right-back is set to send the ball back to this centre-back — which is what we see as play moves on.

The one occasion on which Palmeiras’ press noticeably increases in intensity in higher areas like this is on a backwards pass.

Ferreira likes his side to react to backwards passes and increase the pressure on the opposition’s backline when they happen.

Opposition backwards passes provide a good opportunity for a team to gain some ground and congest the opposition’s field of play with a lower risk of being played through.

This is a common pressing trigger and Palmeiras like to use it to continue forcing the opposition backwards to ultimately force a riskier pass, including a long ball upfield into a position where Palmeiras can contest an aerial duel and win the second ball.

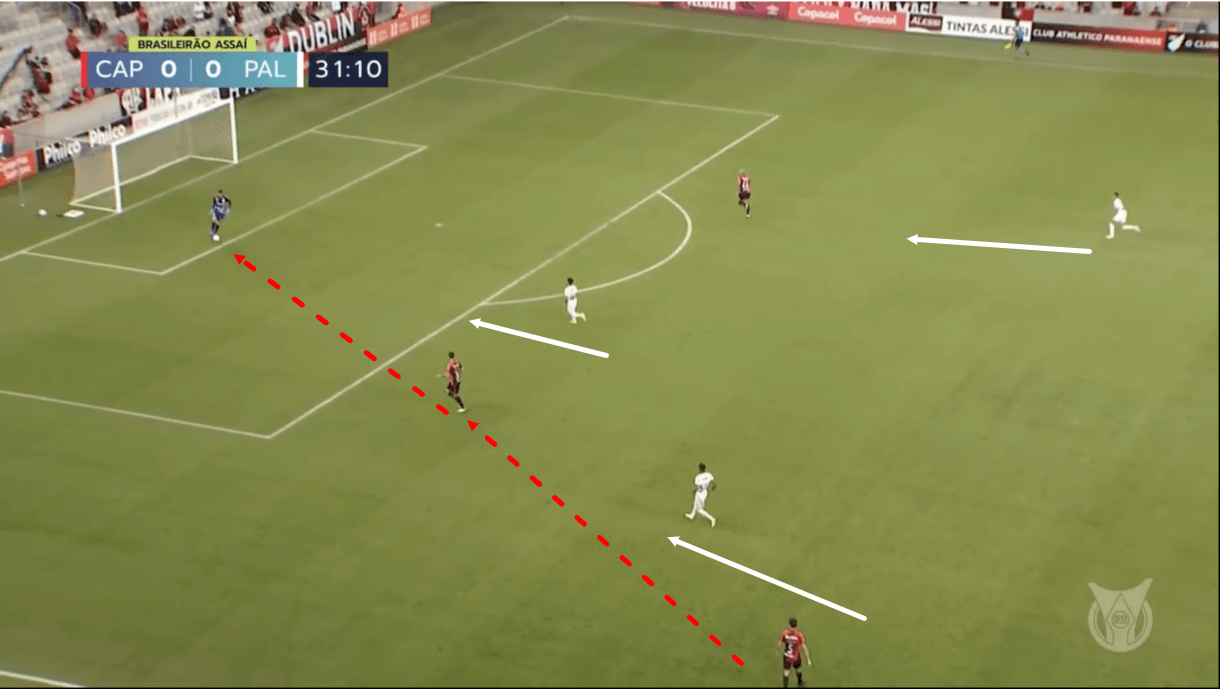

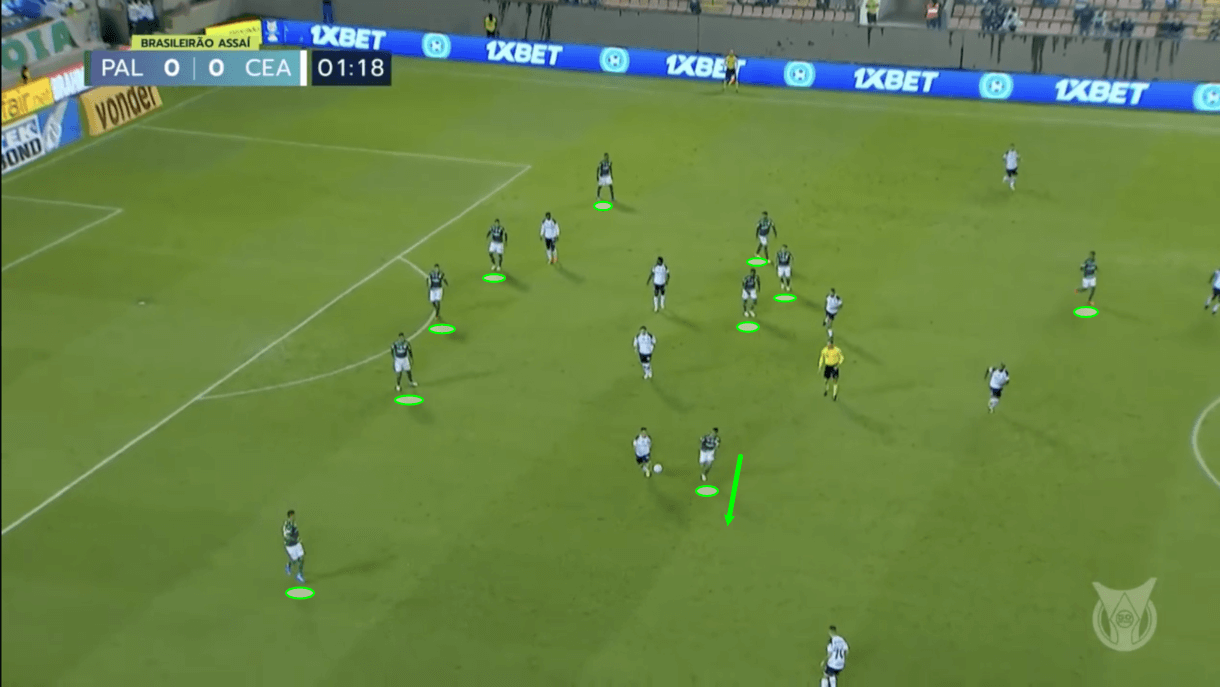

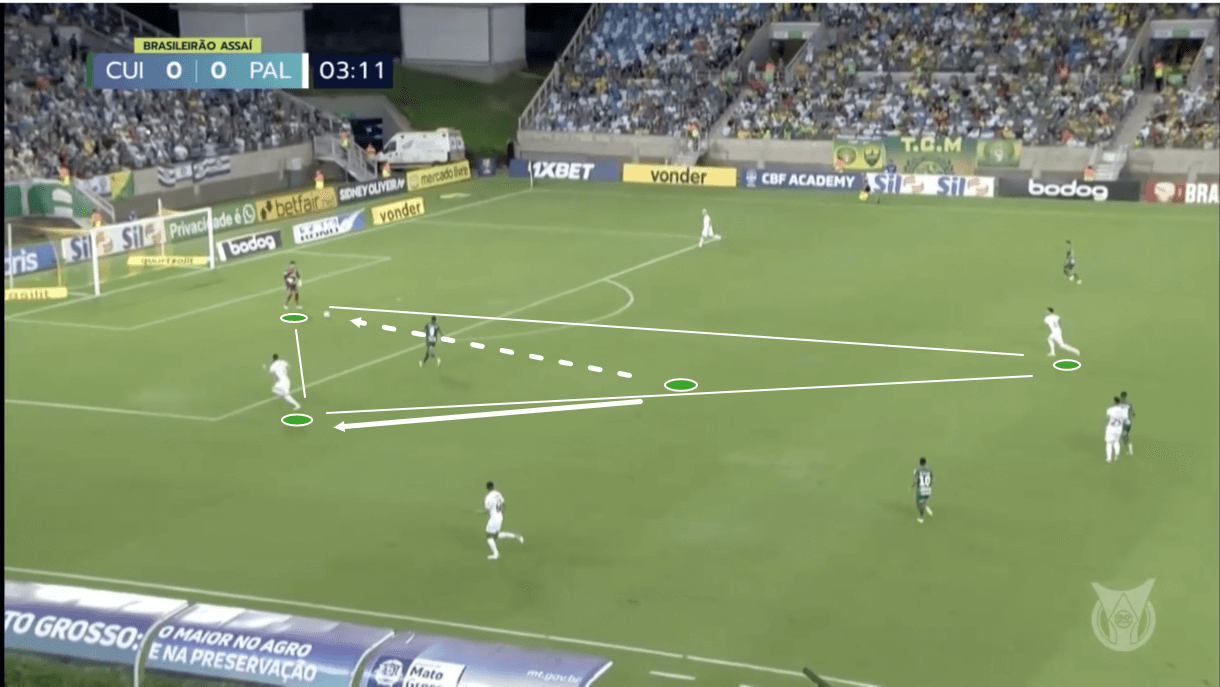

We see how this tactic plays out in figure 2, where after the backwards pass to the centre-back was played, Palmeiras’ front three, and the two central midfielders backing them up, push upfield while remaining compact and preventing gaps that could be played through from opening up.

As a result, they continue forcing the opposition back to the goalkeeper, as we see here.

With the ‘keeper’s near passing options all now under pressure thanks to Palmeiras’ pressing and no more space behind to play into, Ferreira’s side successfully force the ‘keeper into a rushed long ball upfield.

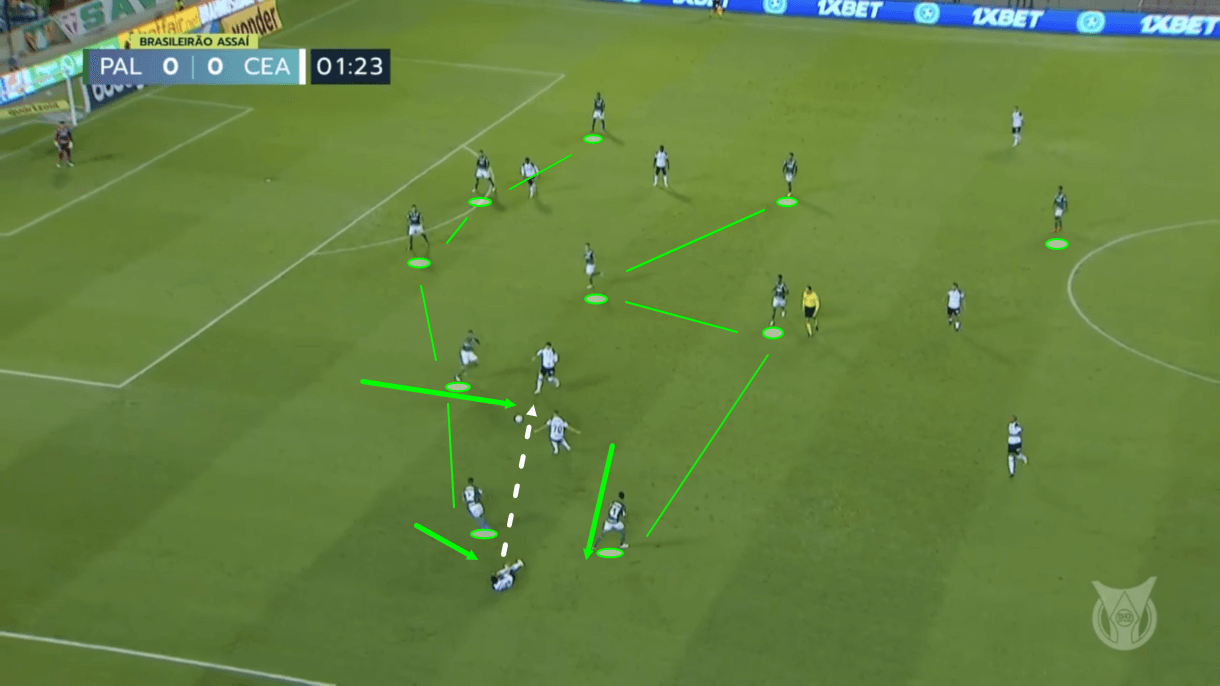

In figure 3, we see the result of this long ball, with Palmeiras’ right wing-back pushing out to contest the aerial duel.

Palmeiras have far more bodies positioned around the drop zone here to win the second ball — including the back three and the two central midfielders who remained tight to the front three but always behind the opposition’s midfielders.

As a result, possession is regained for Ferreira’s side as a result of his organised pressure following the clear trigger they’d prepared for.

Again, though, Palmeiras are generally a more passive side and only really press high on the backwards pass.

More often, we see them remain passive and compact in midfield focusing purely on preventing progression through the centre of the pitch via the positioning we saw in figure 1.

This positioning aims to either force a backwards pass, as was the case here, or force a riskier pass, either drawing the opposition into passing centrally and creating an opportunity for an interception, playing the ball out wide to where the wing-back typically jumps into action and closes the receiver down while using the limited space afforded in the wide areas to his defensive advantage or forcing them to play the ball long earlier.

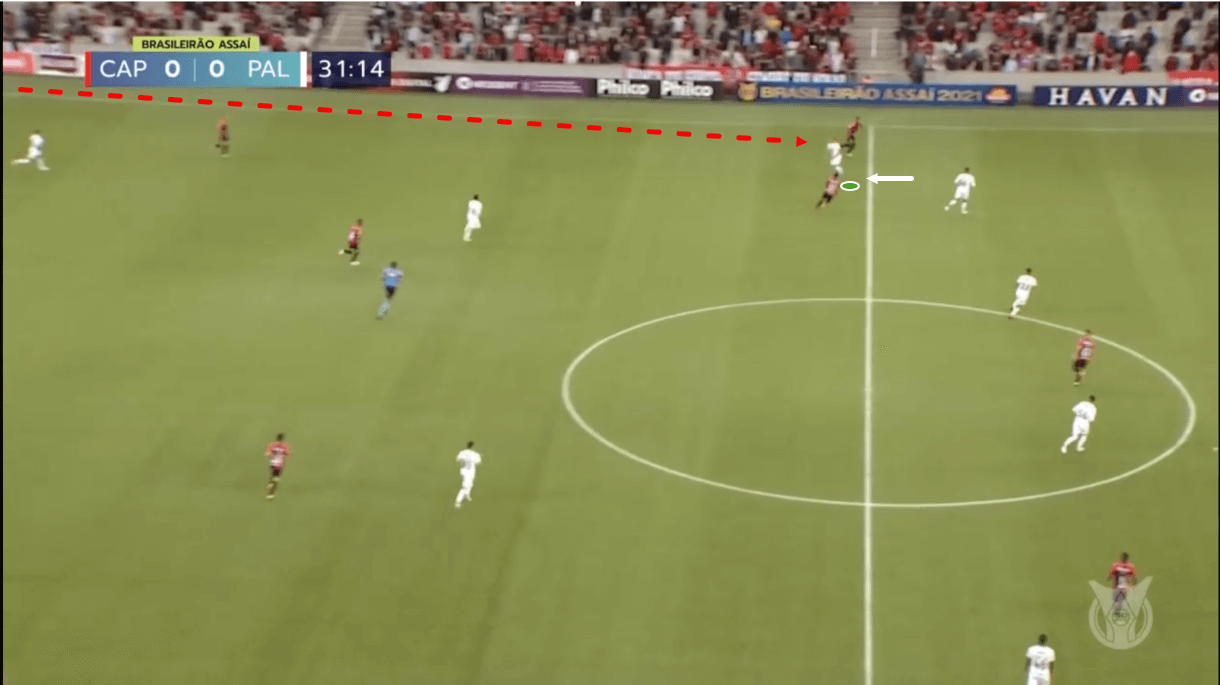

Figure 4 shows an example of Palmeiras as they start to drop into their 5-4-1, with the opposition having progressed to a slightly more advanced stage of their attack in this image than they had in the previous one.

Still, they are yet to reach the halfway line here, so Palmeiras remain patient and focus on protecting the centre without pressing the ball carrier aggressively.

Here, we see an opposition full-back dropping deep to give the ball carrier an option for progression out wide and as he drops, Palmeiras’ wing-back follows him closely.

This is a very common sight which further shows Palmeiras’ intent to protect the centre calmly and passively and force the opposition to play into a wide area, where the wing-back can then defend aggressively.

This image shows the wing-back preparing for this potential result.

If the ball is played to the full-back here, it does enter Palmeiras’ half which leads to pressure increasing anyway.

The Palmeiras wing-back is just readying himself for that possible move and aiming to get in the best possible position to access the wide man on receiving the ball and successfully prevent continued progression.

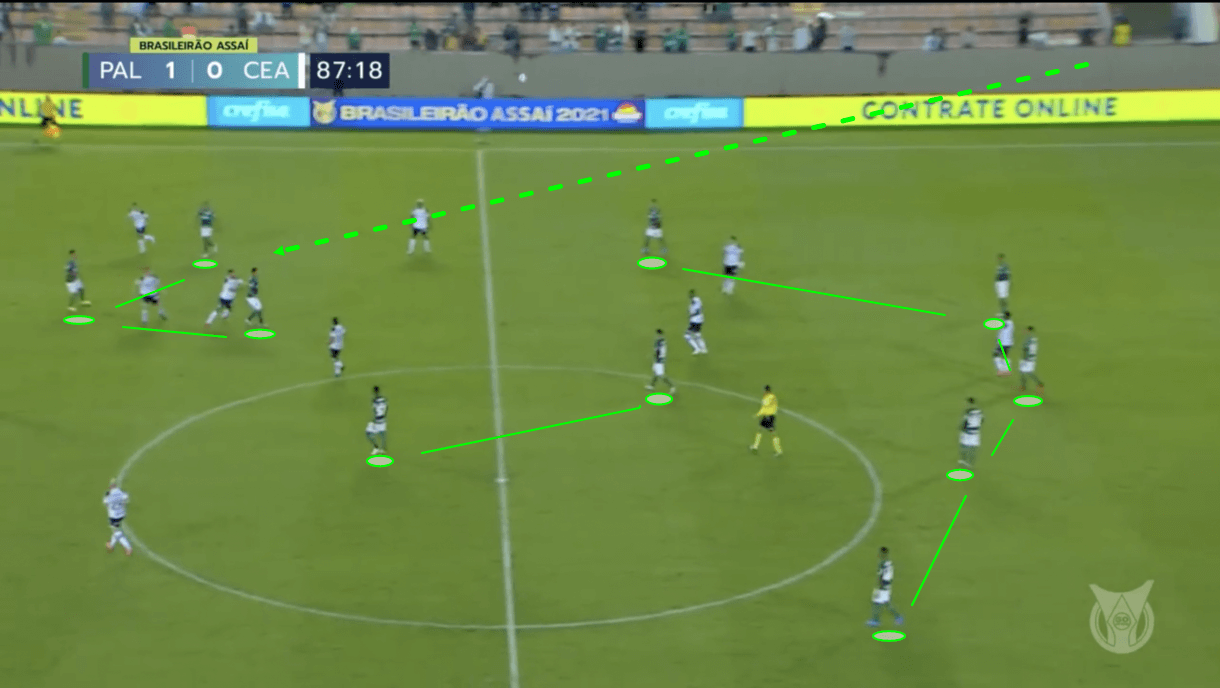

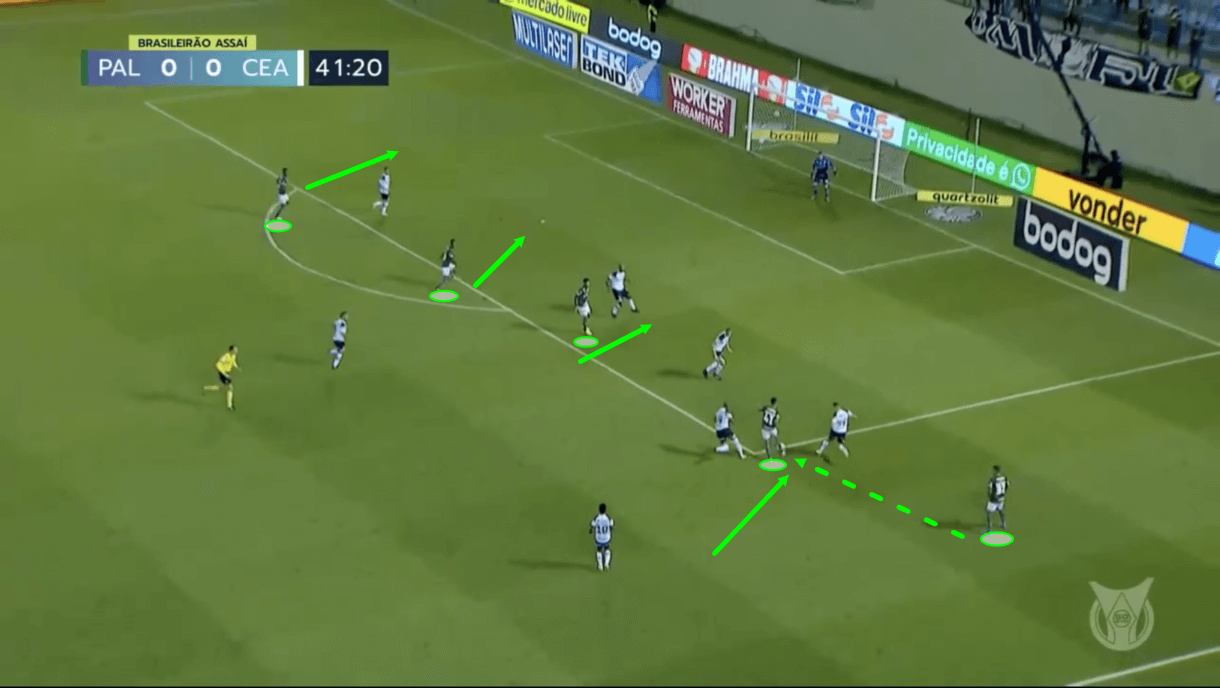

In figure 5, we see an example of Palmeiras operating similarly during an early phase of the opposition’s attack, except this time we see Verdão in the 4-2-3-1.

This shape gives Palmeiras even more presence centrally in higher areas, as another body joins the line just behind the centre-forward.

This can help to guard against a particularly dangerous opposition deep-lying playmaker, if one is there, as figure 5 shows with the centre-forward and the ‘10’ essentially doubling up on the opposition’s holding midfielder here, preventing him from enjoying enough time and space to play a more dangerous pass.

Instead, the deep midfielder is forced to play the ball out wide, still in his own half — a very non-threatening position.

The rest of Palmeiras’ tactics as discussed before are also on show here — a narrow, compact, position-oriented shape focused on protecting the centre and remaining quite passive until about the point that the halfway line is crossed.

Defending deeper

The previous section helps us to get an idea of why Palmeiras made a relatively low number of interceptions/engaged in a relatively low number of defensive duels in 2021 — they are a more passive team defensively, especially in the early portion of an opposition attack, and as such find themselves performing defensive actions less often.

They do need to engage attackers eventually, however, and as we mentioned before, they tend to become more aggressive on the opposition crossing the halfway line.

This next section of analysis will focus on Palmeiras’ defending in deeper areas, to discuss how they tend to operate when this happens.

Firstly, as mentioned previously, Palmeiras’ players will generally drop off at the beginning of opposition attacks and not engage the ball carrier aggressively until they reach the halfway line.

At that point, while the more central players, like the centre-backs and central midfielders, typically hold their position, it’s common to see a ball-near wide man, like the wingers or wing-backs close down the ball carrier if they’re nearby.

An example of how the wider Palmeiras players operate when defending in deeper areas is shown in figure 6.

Here, as the opposition play the ball out to the widest player on the left, that receiver is immediately closed down from the centre by the ball-near winger — who continues to protect the centre and the passing lanes into midfield — and the ball-near wing-back, who also acts aggressively as this wide man receives the ball to prevent him from enjoying too much time and space to make his next move.

At the same time, Palmeiras’ ball-far winger and wing-back move across to an extent with the central players to continue controlling the centre and prevent too much space from opening up between the ball-near pressing players and the rest of the defensive block.

If the pressing players aren’t backed up like this, then it can become too easy for the opposition to cut through them via runs and passes through the gaps that will inevitably open up in Palmeiras’ system.

If Palmeiras’ ball-far players come too far over, however, then it can result in too much space becoming open on the opposite wing and a weakness to switches of play appearing.

It’s worth noting that Palmeiras do still defend in a position-oriented manner and while they focus on remaining compact, they don’t do so very much to the detriment of space on the opposite wing and the ball-far players generally ensure that they retain access to the opposition’s ball-far players.

As play progresses into figure 7, we see how the opposition attempted to exploit space they’d hoped would open up behind the pressing players via passing and movement.

However, as already mentioned, Palmeiras’ deeper, more central players remain central and alert to movement in this space behind the ball-near pressing players.

As the pass was played into the space behind Palmeiras’ wing-back and winger, their right centre-back jumped out of the backline to close down the intended receiver and crucially regained possession for his side in a sensitive area.

This highlights how important it is that this space behind the more aggressive wide players in Palmeiras’ defensive system is protected vigilantly by the alert and disciplined more central players.

It’s common to see the wide centre-backs and holding midfielders dragged into defensive duels like this one, which makes their alertness and technical defensive ability very important.

They know that an important part of their role in this system is to protect space behind the aggressive wide players and sweep up any balls that get played into this space, should the winger/wing-back be unable to force the opposition backwards or win possession themselves via their aggressive pressure.

It’s paramount that Palmeiras’ winger/wing-back act aggressively and close the ball carrier down quickly as they receive the ball out wide, which we’ve now seen some example of in figures 4, 6 and 7, to prevent these players from enjoying too much time and space on the ball.

Even if they fail to win the ball themselves, as was the case in figures 6 and 7, their aggressive pressure can force the opposition into a rushed decision by limiting their decision-making time and then damaging their technical quality as a result.

An example of what can happen if Palmeiras’ wide men don’t apply enough pressure to the receivers in these wide areas as the opposition attempt to progress through them can be seen in figures 8-9.

Firstly, just before figure 8, the opposition’s left-sided wide man received the ball from a centre-back.

However, neither the Palmeiras full-back nor winger were very tight to the player at this stage, unlike what we’ve seen in previous examples, leading to this receiver being given enough time to turn on the ball and face Palmeiras’ goal.

This is a situation Ferreira will want his team to avoid at all costs — he doesn’t want the advanced receivers to be given enough time to turn and face his goal, he wants them to be under immediate pressure and either forced backwards, dispossessed or at least forced into a rushed decision.

That wasn’t the case here and as we can see, now the wide man is facing Palmeiras’ goal with plenty of space to get his head up, decide on his next move and even execute it.

As play moves on into figure 9, we see that thanks to the time afforded him by Palmeiras on the wing, the wide man was able to pick out some movement from an attacker ahead of him and behind Palmeiras’ midfield line, find him with a line-splitting pass, and progress to the edge of the box.

Again, this receiver wasn’t put under pressure and was given the time and space to turn and make his next move — a return pass through to the wide man who was then able to get his team into Palmeiras’ box.

All of this came from the initial lack of pressure on the opposition’s wide man and I hope this passage of play highlights why the constant, immediate pressure on opposition wide men when the ball is played out to them is such an important part of Ferreira’s defensive strategy and tactics.

Palmeiras understandably place most of their focus on protecting the centre — a more valuable area of the pitch — however, if the opposition is given too much space when the ball is played out wide, it can nullify their efforts at protecting the centre because players at this level will be able to exploit space between the lines regardless if they’re allowed to receive, turn and get their head up to assess their options.

This is where aggressiveness is crucial in Palmeiras’ system, even if, overall, they’re quite a passive side.

They need to remain aggressive in the right circumstances.

Abel Ferreira Build-up play

Palmeiras are not a heavily possession-based team under Ferreira.

In 2021, they kept a quite average 50.5% possession in Brazil’s top-flight, while they kept a relatively low 44.2% of the ball in Copa Libertadores last season, indicative of the fact they’re happy to spend larger periods without the ball than many top teams might be and as a result, in Copa Libertadores where they’ll come up against some of South America’s best teams, they’ll experience longer spells without the ball.

This is, in part, because of their relatively passive defensive strategy and tactics.

However, when they do have the ball, their performance doesn’t lend itself to sustained periods of possession either.

They don’t tend to play a lot of passes but do play plenty of long passes — an average of 42.07 per 90 in the league last season, the third most in Brasileirão Série A.

This is typical of their rather direct playing style; Ferreira’s team likes to get the ball forward into the final third as quickly as possible, and their effectiveness at doing this has been key to their attacking play and overall success under the Portuguese coach.

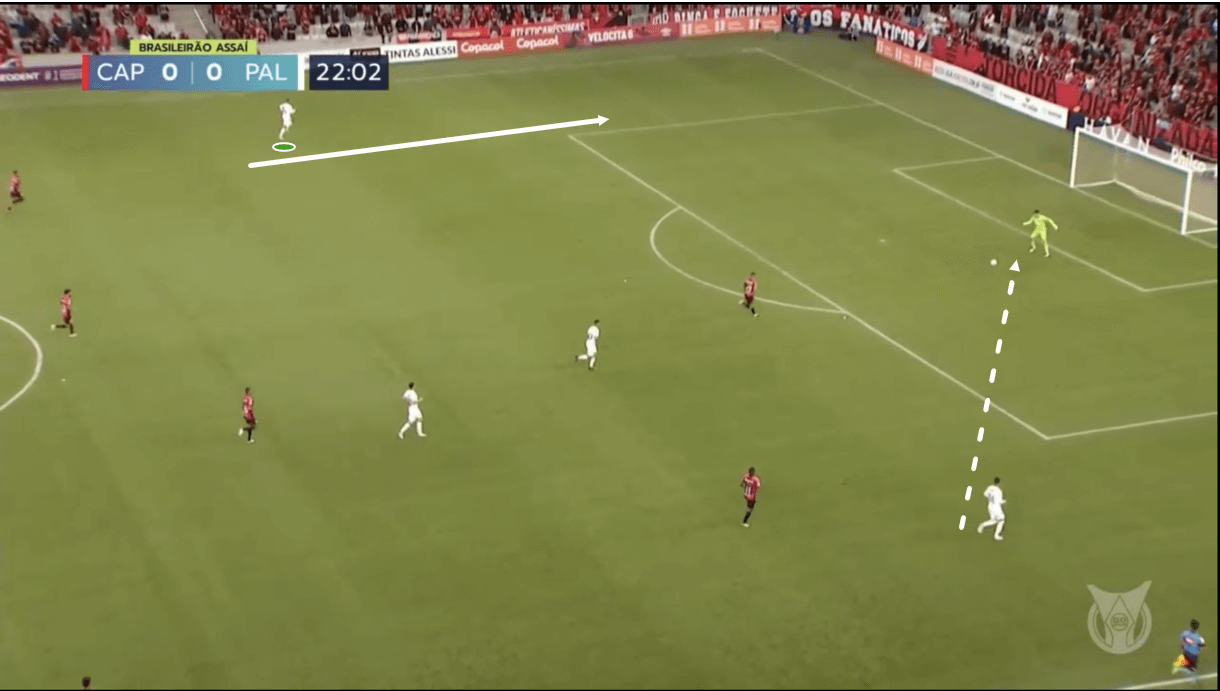

Firstly, from goal-kicks, it’s common to see Ferreira’s goalkeeper go long.

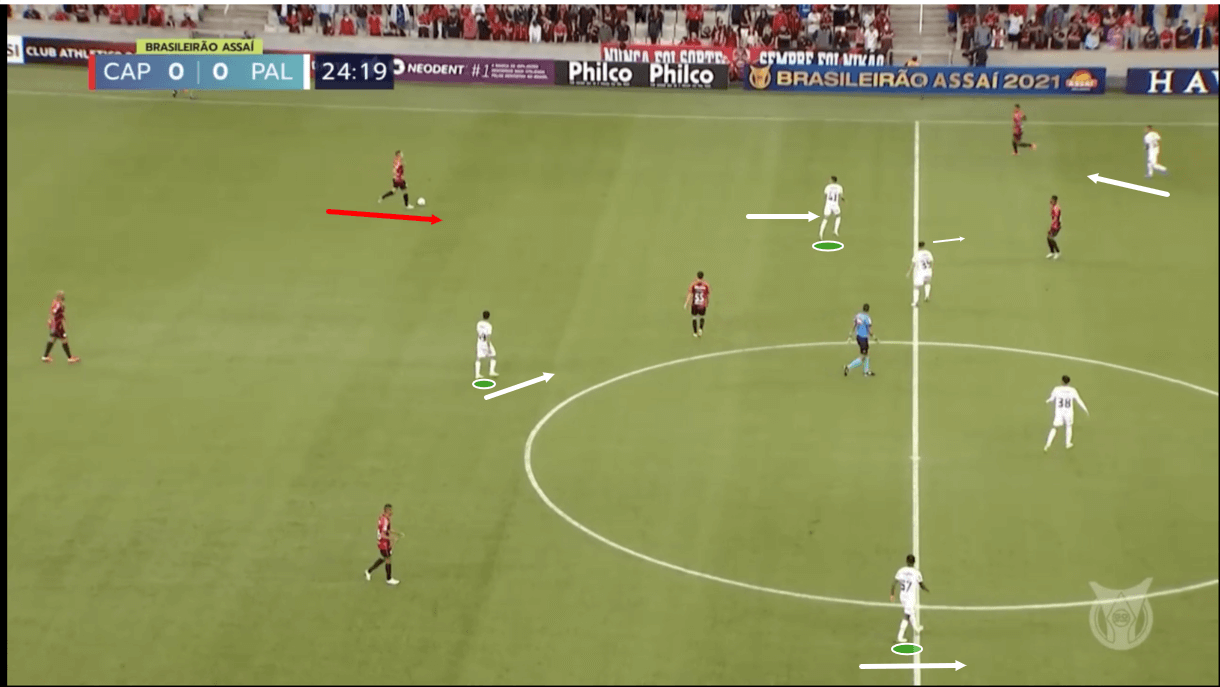

In figure 10, we see Palmeiras’ left-winger preparing to contest an aerial duel with an opposition defender while positioned quite centrally and actually more towards the right side of the pitch than the left, where he would be positioned in defensive phases.

It’s very common to see Palmeiras’ wingers come narrow during possession phases, getting closer to their centre-forward and freeing up space on the wing for the wing-backs to move forward into.

It’s especially common to see the wingers and centre-forward congregate in an area when contesting an aerial duel from the goal-kick, to help with winning the second ball.

Furthermore, as this image shows, it’s common to see Palmeiras’ central midfielders stagger during possession phases.

In this example, we see the left central midfielder has pushed higher while the right central midfielder remains deeper, in front of the backline.

This more advanced central midfielder can also help with winning the second ball following the aerial duel, while this stagger in midfield is also important for creating passing angles for their teammates when the ball is on the ground while making it more difficult for the opposition to mark them.

This is a very common shape to see Palmeiras take up when contesting an aerial duel from the goal-kick while playing with a back-five, and their shape in such situations when playing a 4-2-3-1 is quite similar.

The focus is always on getting lots of bodies around the drop zone to win the second ball, keeping a stagger in midfield and keeping the wingers narrow to make space for the wing-backs to provide the width.

Meanwhile, the centre-forward remains highest, leading the line, but retains the freedom to move wider if necessary.

He’ll generally be looking to provide depth, but his exact position may change as he reacts to movement both from his teammates and the opposition, and how that influences space.

When playing out from the back shorter, which does happen at times as well, we also see a lot of what we mentioned previously — narrow wingers, wing-backs sitting high to provide the width and a staggered midfield duo — however, it’s also very common to see Palmeiras’ wide centre-backs position themselves very wide and drop very deep during the build-up.

In figure 11, we see that Palmeiras’ left centre-back has just passed the ball back to the goalkeeper here under pressure from the opposition.

As the ‘keeper prepares to receive the ball, Palmeiras’ right centre-back is dropping deep to get into his deep, wide position.

The right centre-back then receives the ball from the ‘keeper in his deep wide position; the pass must be played to the opposition’s goal-side of the centre-back to make it easier for him to turn and progress Palmeiras upfield.

Otherwise, this would create a difficult situation for Palmeiras and a very good pressing opportunity for the opposition.

Here, the pass was played well from the ‘keeper and figure 12 shows the results — Palmeiras’ right centre-back, in possession, facing the opposition half, assessing his forward passing options.

The purpose of this deep, wide positioning is that 1.

By coming so deep and wide it creates more of an angle for the ‘keeper and makes it more difficult for the opposition to cover all of the goalkeeper’s forward passing options and 2.

Sitting deep like this draws opposition players upfield and creates more space behind them for Palmeiras to target.

Figure 12 shows that the right centre-back was able to receive this pass as the opposition was unable to guard against him following his deep, wide movement while still marking Palmeiras’ other players, such as the deep-lying midfielder and the central centre-back.

Now, with the right centre-back attracting a lot of pressure from the opposition, a pass into the central centre-back is a decent option, as the opposition players struggle with covering everyone more thanks to the angles that have been created.

However, the right centre-back doesn’t take that option here, as an even more advanced pass is also on and Ferreira likes his side to get the ball upfield as quickly as possible quite early, so likely encourages playing the furthest forward available pass and some quite risky passing play.

This is part of why Palmeiras played the third-most long balls of any Brazilian top-flight side last season.

As the opposition are drawn upfield towards the deep centre-back, a pass into the right central midfielder becomes available, with that midfielder enjoying plenty of space behind the opposition’s now-advanced midfield line.

The right centre-back spots this by getting his head up and can execute the forward pass well, setting Palmeiras off on an attack.

From here, the receiver has the time and space to take the ball on the half-turn and continue this vertical play, progressing Palmeiras into the opposition’s half.

This is a typical example of Palmeiras’ shorter build-up play, which also generally sees Verdão making it out of their half in relatively few passes and playing quite vertically.

The tactics on display above are very common elements of their build-up play that have proven effective under Ferreira.

Another example of Palmeiras’ centre-backs dropping deep and wide is shown in figures 13-14, with a slightly different result.

Firstly, figure 13 shows Palmeiras’ right centre-back on the ball while the opposition is pressing high.

With no good forward passing options available, the centre-back opts to send the ball back to the ‘keeper and drop deep and wide, just like we saw in figures 11-12.

As play moves on into figure 14, we again see how this draws opposition bodies further upfield and creates more space to attack behind the midfield line.

However, the result of this particular example is different to the previous one and shows another big benefit of this tactic.

As mentioned before, this movement from the centre-backs makes it more difficult for the opposition to mark all of Palmeiras’ passing options and on this occasion, the opposition’s centre-forward remains close to the passing lane between the ‘keeper and the right centre-back.

However, by dropping deeper and wider, and drawing the opposition’s centre-forward with him, the right centre-back opens the passing lane between the ‘keeper and Palmeiras’ deep central midfielder who we see dropping at this moment.

As play moves on from here, we see the ‘keeper send the ball forward, into midfield and the feet of this dropping midfielder, who again, can turn from here and continue Palmeiras’ progress.

So, it’s clear how this movement has plenty of benefits for Ferreira’s side that they’ve used to progress past the opposition’s first line in different ways.

Abel Ferreira Tactics final third

Moving further upfield and into their play inside the final third, it’s common to see Palmeiras’ wingers in the half-spaces while the wing-backs provide width outside and the centre-forward stays centrally, forming a front five that can overload the opposition’s backline.

Furthermore, it’s fairly common to see one of Palmeiras’ central midfielders push forward to provide some additional support either as another crossing option or by making a late run into the box to hopefully arrive unmarked.

The wingers, centre-forward and wing-backs enjoy enough freedom to interchange their positions, which can make them more difficult to mark and free up a man, while also moving the opposition defenders around to create space between them.

It’s very common to see a lot of movement in the wider areas, with Palmeiras typically focusing a lot of their play in the final third on the wings, where they can, for example, overload opposition full-backs and/or pull them away from the rest of the backline to exploit space that appears between them and the nearest centre-back.

Ferreira’s direct side ended 2021 as the third-highest scorers in Brasileirão Série A (58 goals), while they also had the third-highest xG in the league (55.18 — indicating some overperformance but not to a crazily unsustainable level).

Interestingly, Palmeiras also ended last season with the most headed goals (12) of any Brazilian top-flight side, which is a direct result of their focus on wing play in the final third and the crossing opportunities they successfully created.

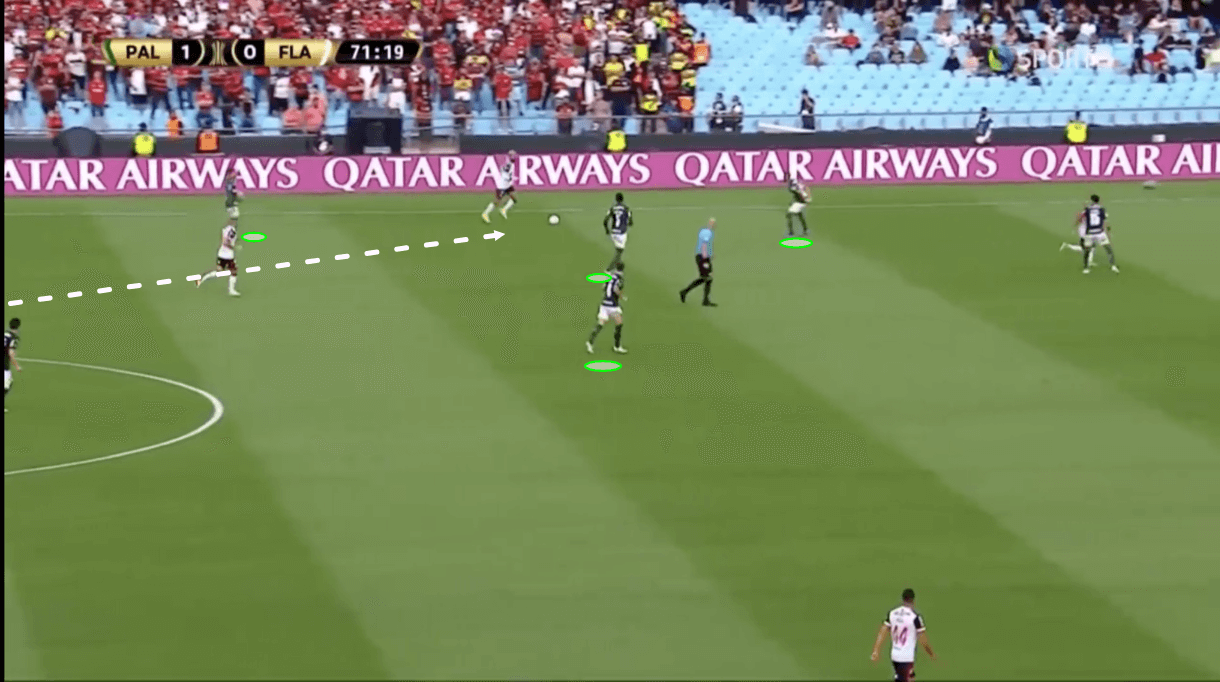

An example of Palmeiras’ front five and final third wing play to overload an opposition full-back is seen in figure 15.

Here, their right wing-back is holding the width, having just created some space between that player and the nearest centre-back by dragging them wider.

Meanwhile, Palmeiras’ right-winger is attacking that space after receiving a well-weighted and well-timed through pass from the wing-back to send him into the space between the opposition defenders.

As the right-winger carries the ball into the box, he has one option at the far post (the left wing-back making a run on the opposition right-back’s blind side), one option centrally (the ball-far winger) and one option at the near post (the centre-forward) to aim for, with those three players also now enjoying a 3v2 overload in the centre of the box, as the right-winger has bypassed the opposition left-back and is now drawing the left centre-back towards him.

This is an excellent example of how Palmeiras’ front five can create such dangerous situations inside the final third, initially with an overload on the opposition’s full-back out wide, and then inside the box after removing at least one defender from the occasion before approaching the box.

Their success at creating good crossing opportunities from this kind of attacking play in the final third has played a big part in their success with scoring so many headed goals under Ferreira.

The players’ movement and decision-making is crucial in such situations, as is the offensive structure that’s been created for them to work within.

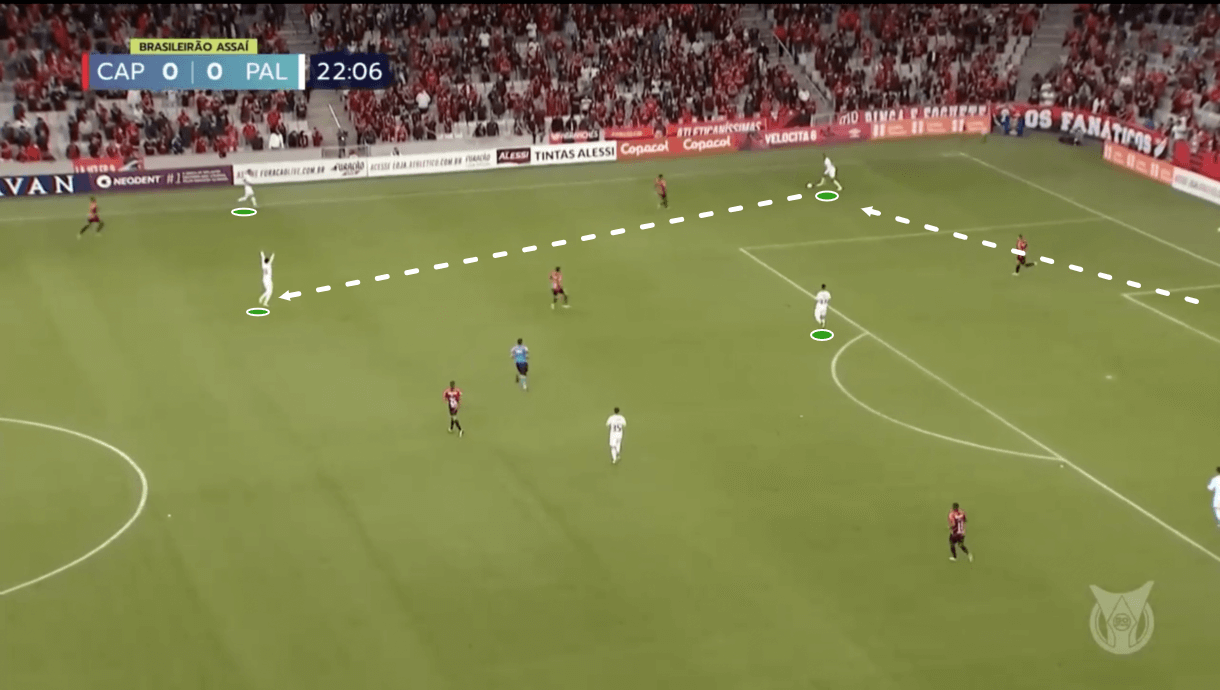

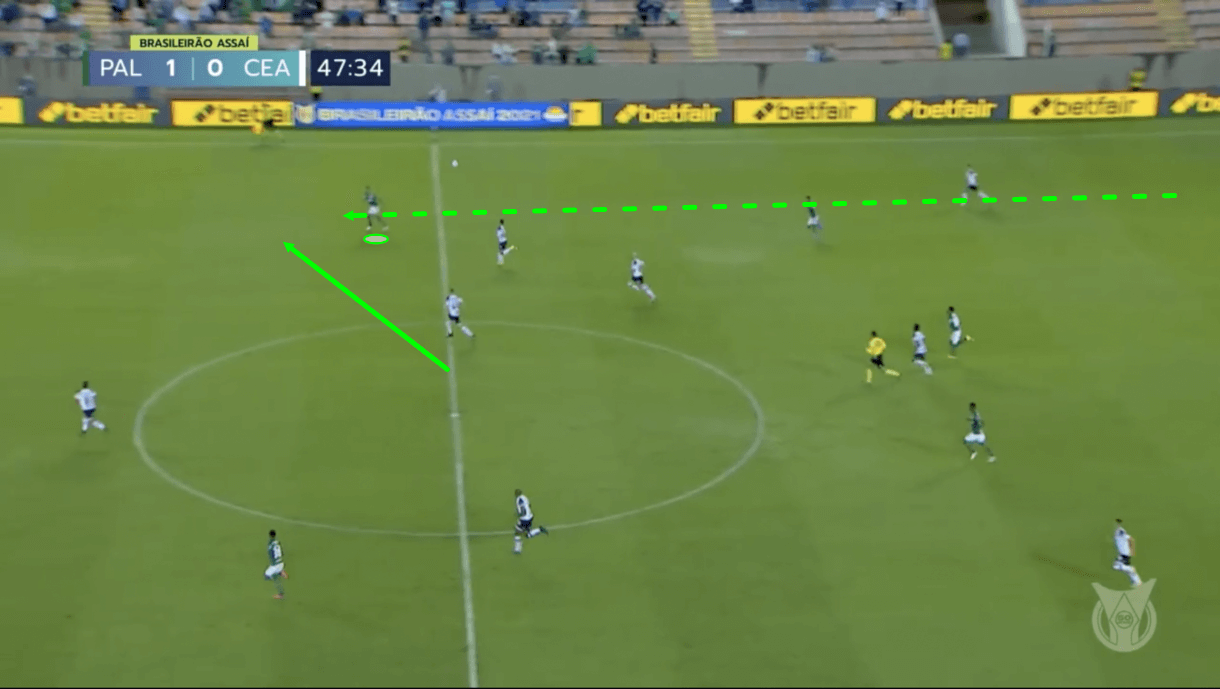

Under Ferreira, Palmeiras have been a dominant team in offensive transitions; they love counter-attacks and are good at getting the ball upfield quickly to exploit space that’s opened up in the opposition’s half due to their previous attack.

Figure 16 highlights one example of what they do in transition, and this particular example focuses on their centre-forward’s movement.

As previously mentioned, Palmeiras’ centre-forward always focuses on providing the offensive depth for Verdão but retains the freedom to move about laterally to exploit space where possible.

In this example, the opposition have just been dispossessed deep inside Palmeiras’ half, following an attack in which their full-backs got forward.

It’s quite common to see teams committing their full-backs forward in attack while their centre-backs stay deep to protect the area right in front of goal.

As a result, it can be common to see Palmeiras’ centre-forward vacating the centre and moving out to the wing when the ball is won deep to provide an immediate, dangerous out-ball for the deeper teammates.

With lots of space to attack, this player can then chase the long ball from the back to drive the team forward in transition.

Even if the ball isn’t immediately launched into space like we see in figure 16, it’s important for a Palmeiras attacker — mainly the centre-forward — to find space in which they can receive a long ball in transition, holding up the play while the other attacking teammates burst forward.

It’s also, then, important for the other attacking players — the wingers and wing-backs in particular — to be quick and hard-working immediately as the ball is turned over to ensure the ball carrier has plenty of options to play through behind the opposition’s backline as they quickly break into the final third.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis, I hope it’s clear how a rather passive, yet organised and aggressive in the correct, limited circumstances defensive system has played a major role in Palmeiras’ success under Ferreira.

On the other side of things, then, Palmeiras’ five-man frontline in attack — consisting of their centre-forward, wingers and wing-backs, is key to their attacking play with doubling-up on the opposition full-backs and overloading the backline, particularly in wide areas.

Meanwhile, their quick, direct transitions have also been very important contributors to their impressive goalscoring record of late, all a result of Ferreira’s vision and framework.

Comments