Since AC Milan sacked Marco Giampaolo in October 2019 after just seven league games in charge, Stefano Pioli has taken charge of the Rossoneri in their search for a return to European football.

In this tactical analysis, I’ll try to answer the question of have AC Milan improved under Stefano Pioli?

Reflecting on Giampaolo’s reign

In order to see whether or not Pioli has improved Milan or not we need to use analysis to examine the situation before Pioli and what he inherited.

After parting ways with club legend Gennaro Gattuso at the end of the 2018/19 season, AC Milan hired Giampaolo after a relatively successful 3-year stint at Sampdoria.

However, the 52-year-old was sacked after just 99 days in the job, so what went wrong for Giampaolo?

Giampaolo won three and lost four of the seven matches he served as Milan manager.

This record left Giampaolo with a 43% win rate and an average points per game total of 1.29.

If this record was maintained over the course of a 38 game season, Milan would have accumulated 49 points, a total which would have Milan finish 10th in last season’s table.

Of course, projecting where Milan would have finished based off of such a small sample size does not truly give us an accurate reflection.

Such a small sample size is why some have criticised Milan’s decision to sack Giampaolo, as Milan were just three points off of 5th placed Roma at the time, the situation was very much salvageable after less than two months into the season.

The seven matches which Giampaolo oversaw were:

- Udinese 1-0 Milan (L)

- Milan 1-0 Brescia (W)

- Hellas Verona 0-1 Milan (W)

- Milan 0-2 Inter (L)

- Torino 2-1 Milan (L)

- Milan 1-3 Fiorentina (L)

- Genoa 1-2 Milan (W)

Now that we’ve seen the results that Giampaolo received, let’s take a look at some other aspects of Giampaolo’s reign which led to his dismissal, as results are just one facet of managerial performance.

Uncertainty of playing style

In his seven matches, Giampaolo employed three formations, originally starting with the 4-4-2 diamond he has preferred throughout his managerial career, then migrating to a 4-3-2-1 and eventually a 4-3-3 in his final match, a win over Genoa.

He was also not sure what his best XI was, rotating heavily and using players in a multitude of different roles.

For example, Suso was used as the attacking midfielder in a diamond, a right winger in a 4-3-3, and one of the two players behind the forward in a 4-3-2-1.

Defending against width

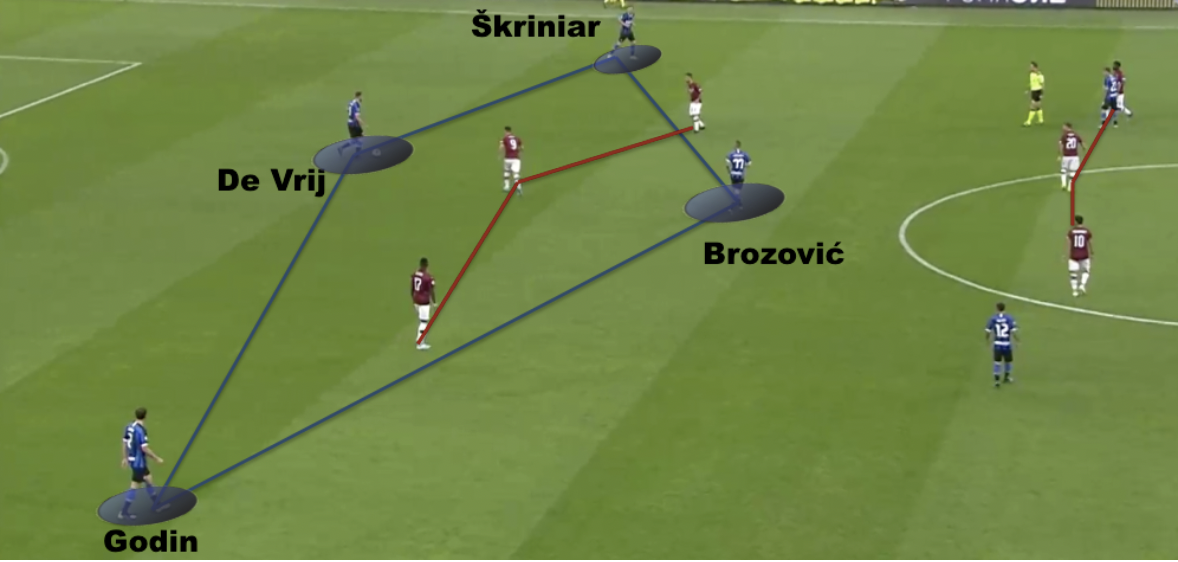

The defeat against Inter has countless examples of one of the biggest issues Milan faced: defending wide areas.

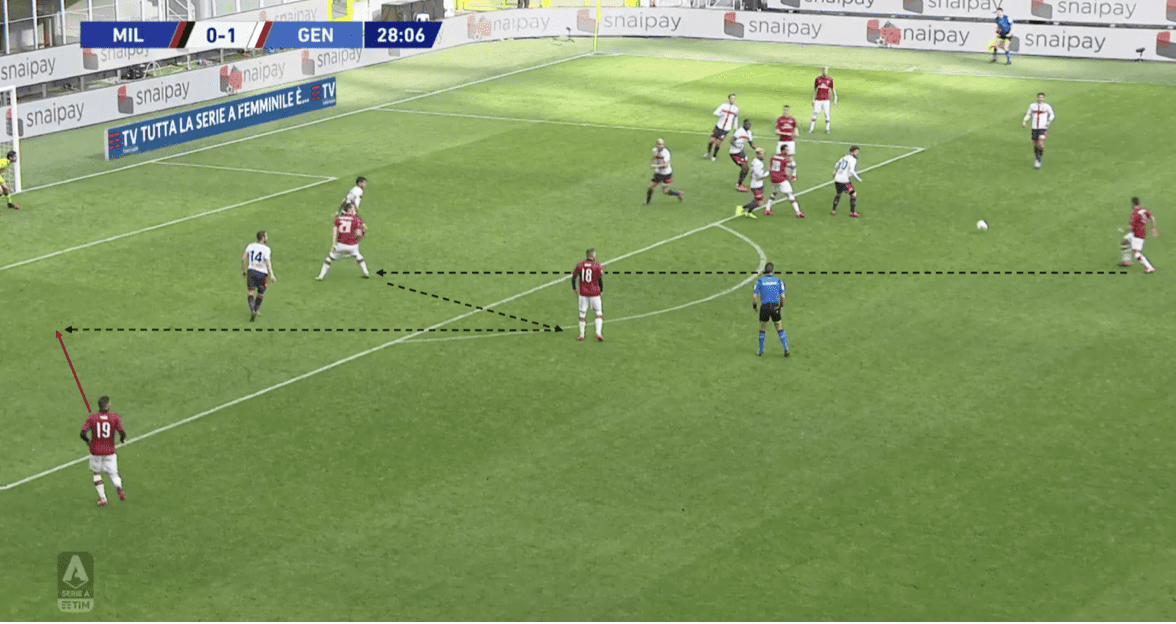

In the example below we can see Inter can easily play around Milan’s very narrow pressing structure.

In a different example, we can see how Milan heavily commit players to the press to shift over when defending width, leaving them extremely vulnerable to switches of play on the far side

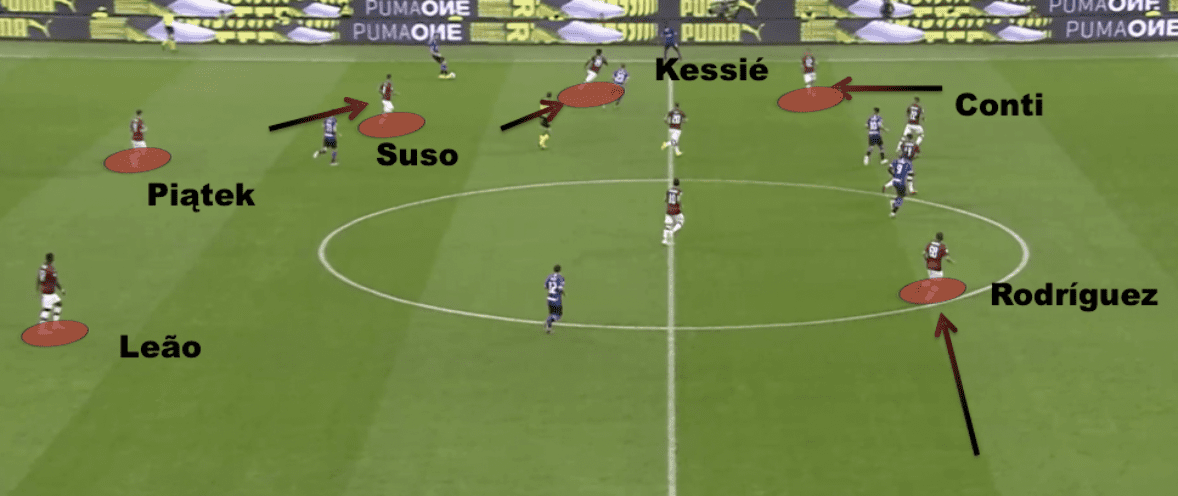

Kessié, Suso, Conti, and Rodríguez all shift to cover the width, which as we can see in the next example, leaves them open on the far side.

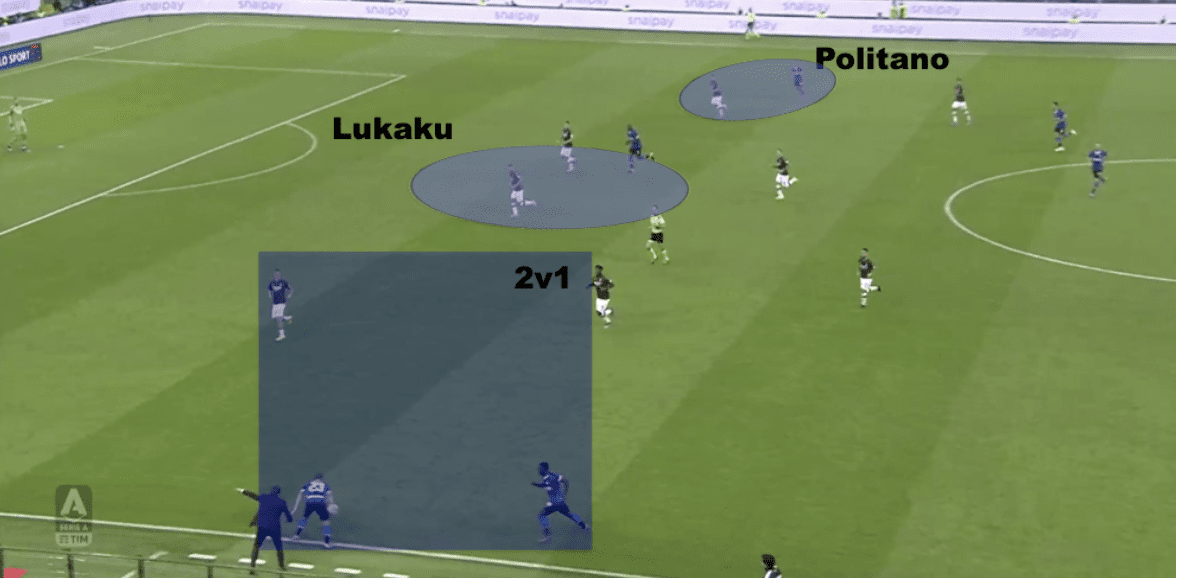

In the next example, Lukaku pins both Milan central defenders, while they create a 2v1 on the near side, and stretch the play by occupying the far side with Politano.

Comparing Pioli’s reign so far to Giampaolo’s

As I previously mentioned, using such a small sample size as a barometer for future appointments won’t give us very accurate results, however, we can see a rough idea of how Pioli is fairing in comparison to his predecessor, not only with results, but with playing style and team selection.

Taking a look at results first, at the time of writing Pioli has played 21 games, with 9 wins, 7 draws, and 5 defeats.

This leaves the former Inter manager with a superior points per game average of 1.62 in comparison to Giampaolo’s 1.29.

Interestingly, Giampaolo’s win percentage of 43% is better than Pioli’s 41%.

Tactical Analysis of Pioli’s Milan

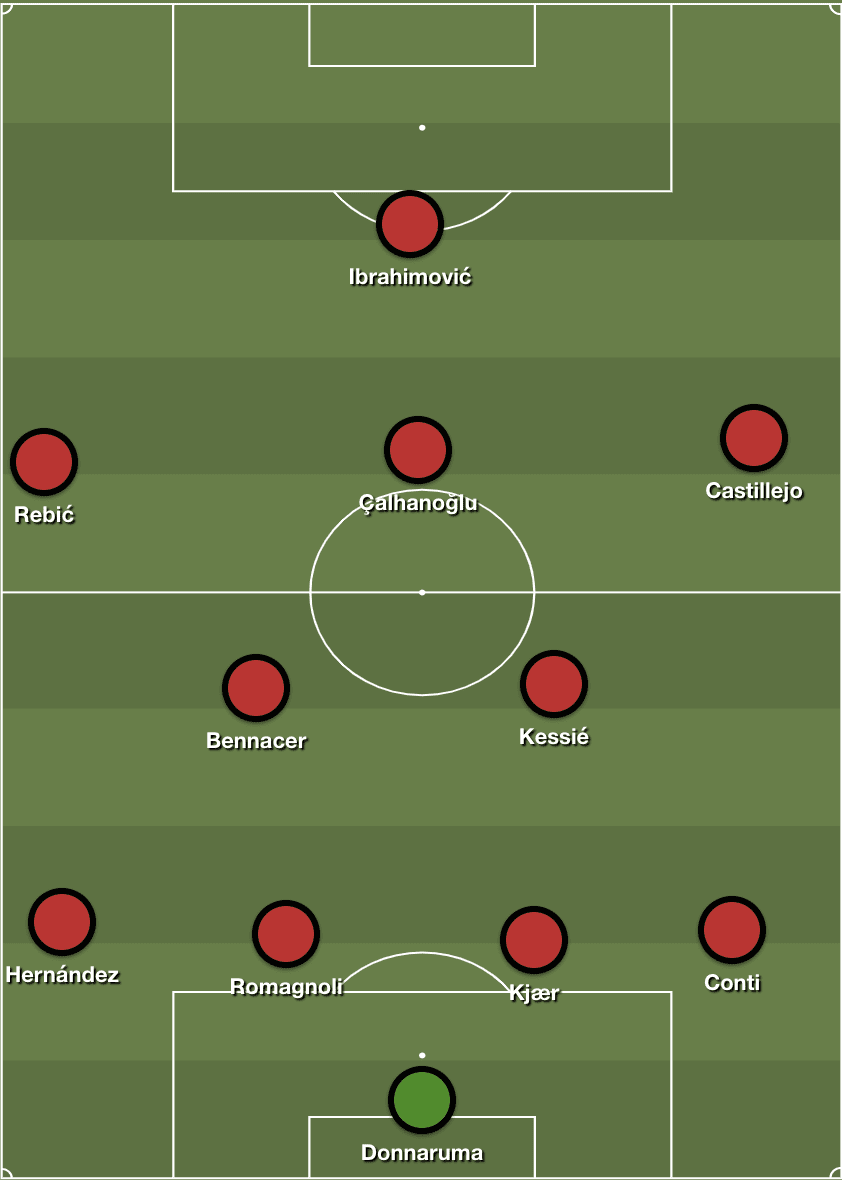

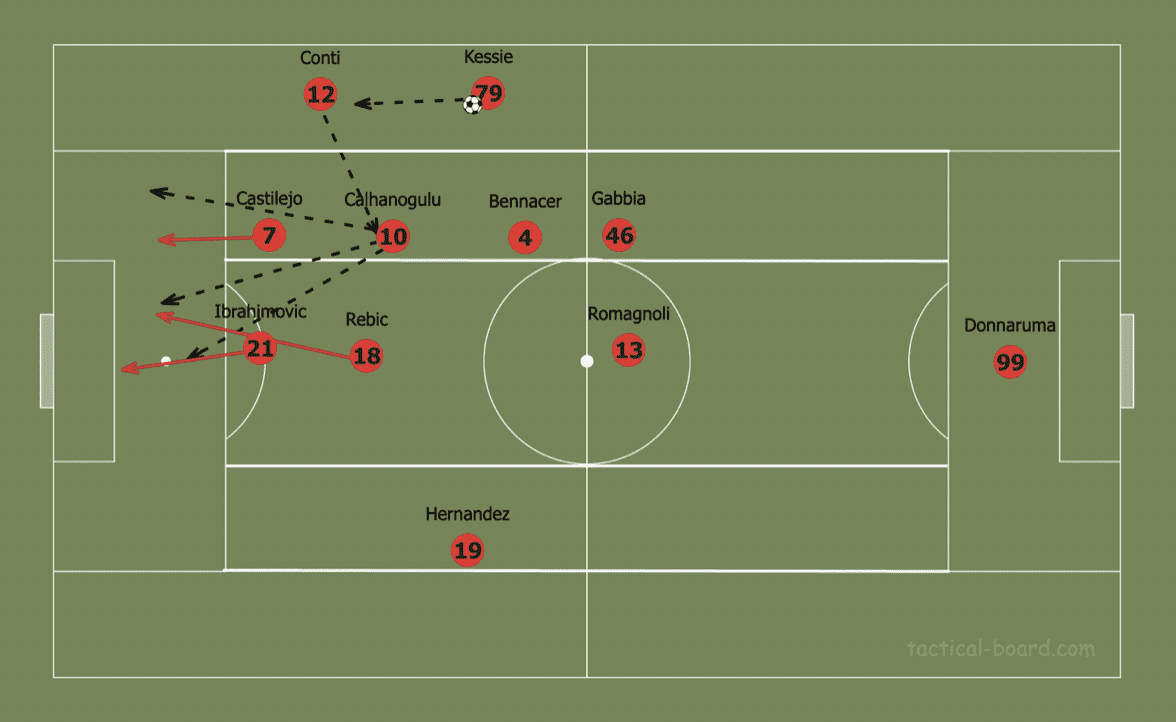

Pioli, unlike Giampaolo, has also found his preferred starting lineup with his favoured XI being shown below, this can be due to the time Pioli has been in the job compared to Giampaolo’s brief stint.

The only real uncertainty has been who partners Romagnoli in central defence, with Kjær, Gabbia, and Musacchio all featuring.

Donnarumma’s spot has also not been nailed down under Pioli due to recent injury problems, but the 21-year-old is still the first-choice goalkeeper.

The most common lineup is a hybrid between a 4-2-3-1 and a 4-3-3.

Bennacer plays as a deeper playmaking midfielder who acts as the left side of the double pivot at times, while Kessié’s role is as the right side of a traditional double pivot.

Çalhanoğlu usually plays as a traditional ‘number 10’, supplementing the attack, while stepping out to press at times in defense.

Attacking play: build-up

Milan’s offensive organisation is all part of a structured game plan, with each phase of their attacking play leading to the next in a smooth, deliberate manner.

Their general attacking game plan is to overload the right side, then use combination play to progress the ball at pace to the left side.

Looking to overload and isolate.

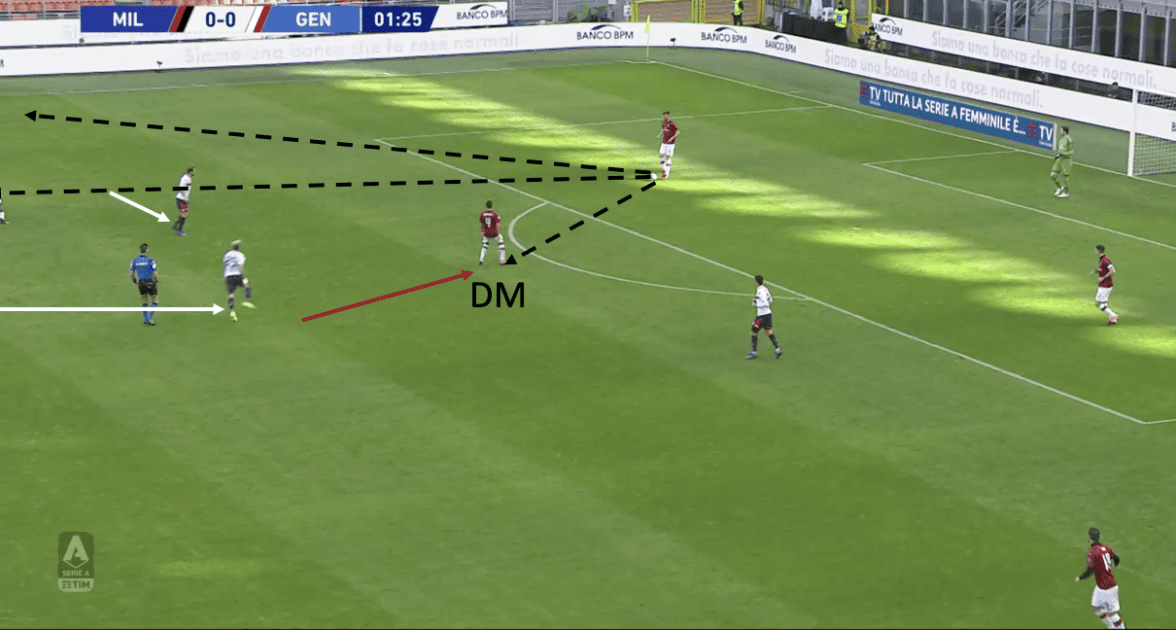

When playing out from the back, Milan open up space on the right side by dropping Bennacer deeper, who attracts opposition pressure towards the centre.

Kessié, who plays as the right-sided central midfielder, will shift wide to create a passing option alongside right-back Conti.

The opposing team will usually see the short pass to Bennacer in the middle as the greatest threat, hence they will vacate the nearby area to apply pressure to the Algerian.

This vacates the wide areas where Milan can play to the right.

The left-back (Hernández) will stay relatively wide to stretch the opposition.

If a Milan player receives the ball on the left, they’ll look to circulate the ball around the defence until it reaches an area which they can look to draw in a central press.

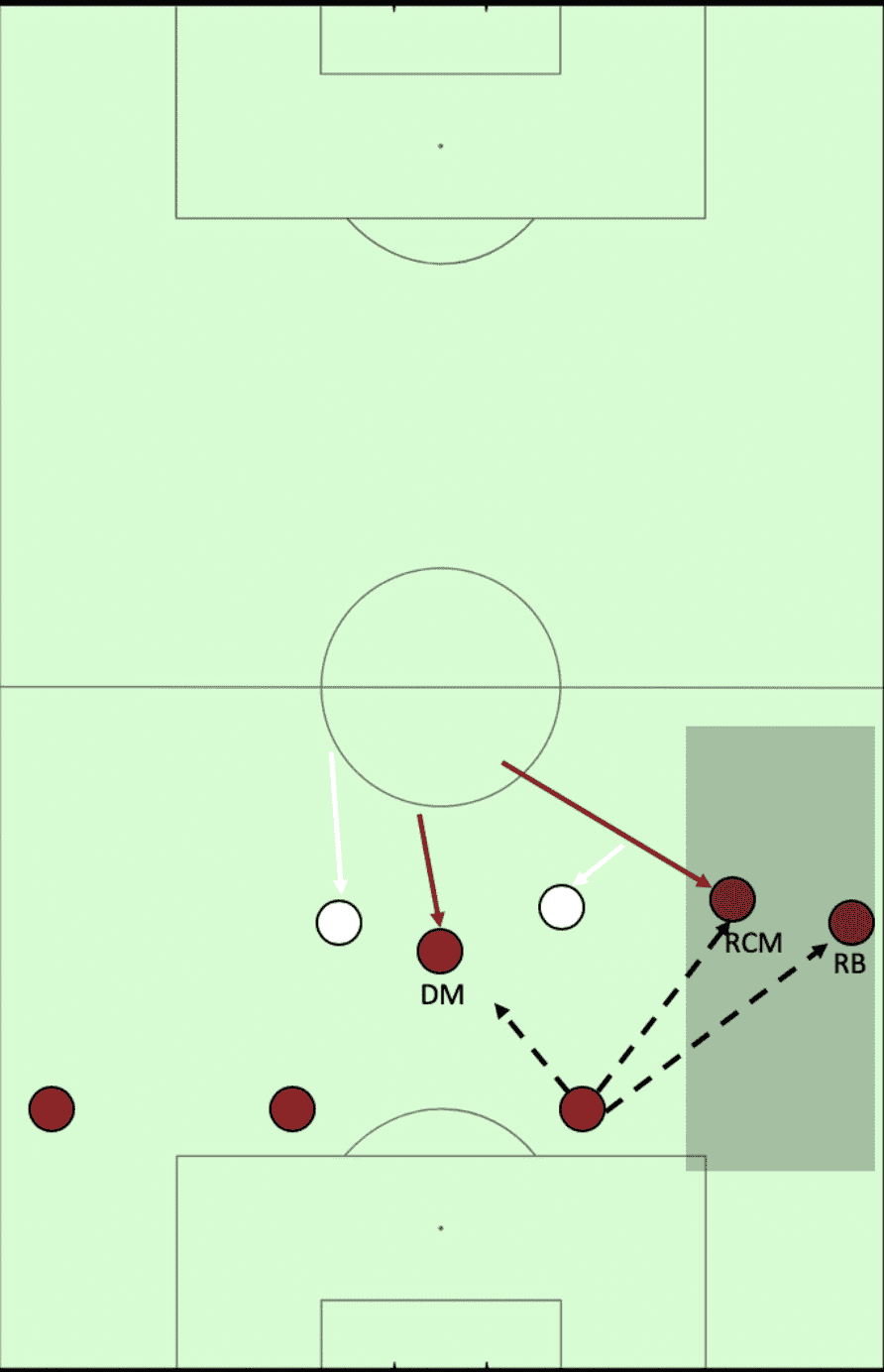

In the diagram shown below we can see this in action.

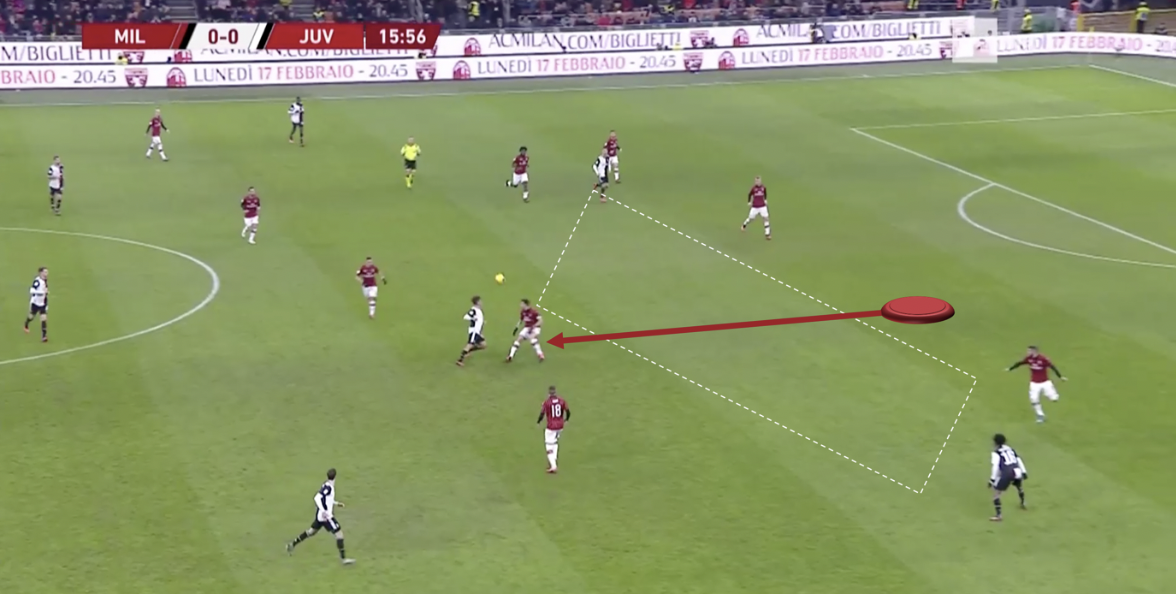

The DM (Bennacer) drops, attracting pressure, freeing up the wide space where the RCM (Kessié) shifts to take up a wide position next to the RB (Conti)

The image below is an example of such a scenario, although Kessié and Conti are not on screen.

Progression into the middle and final third

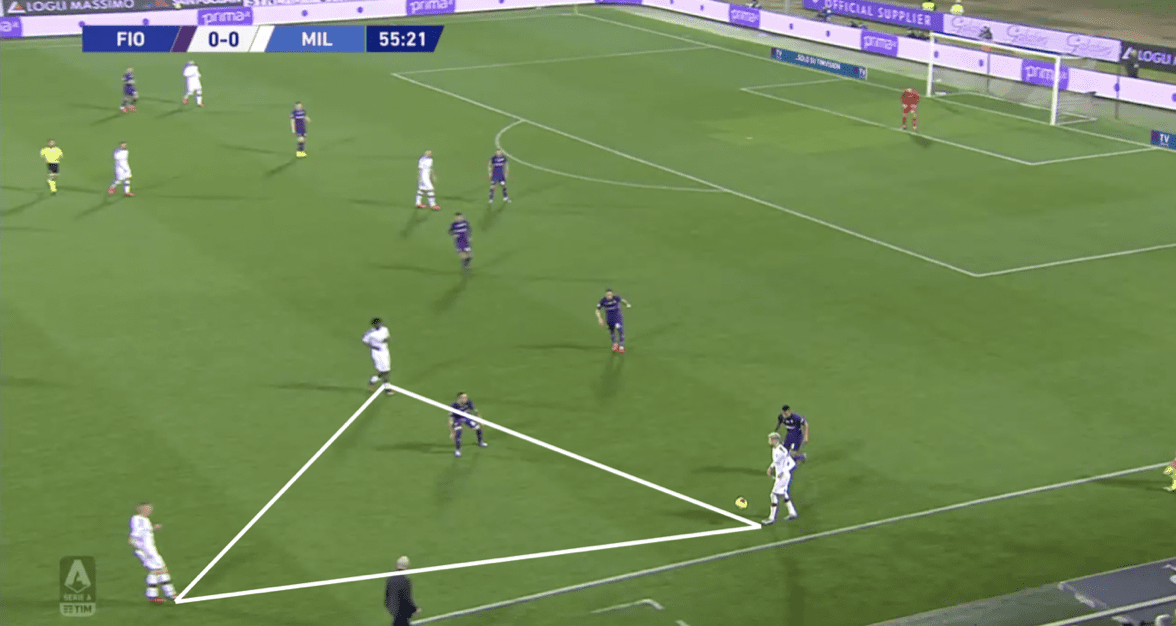

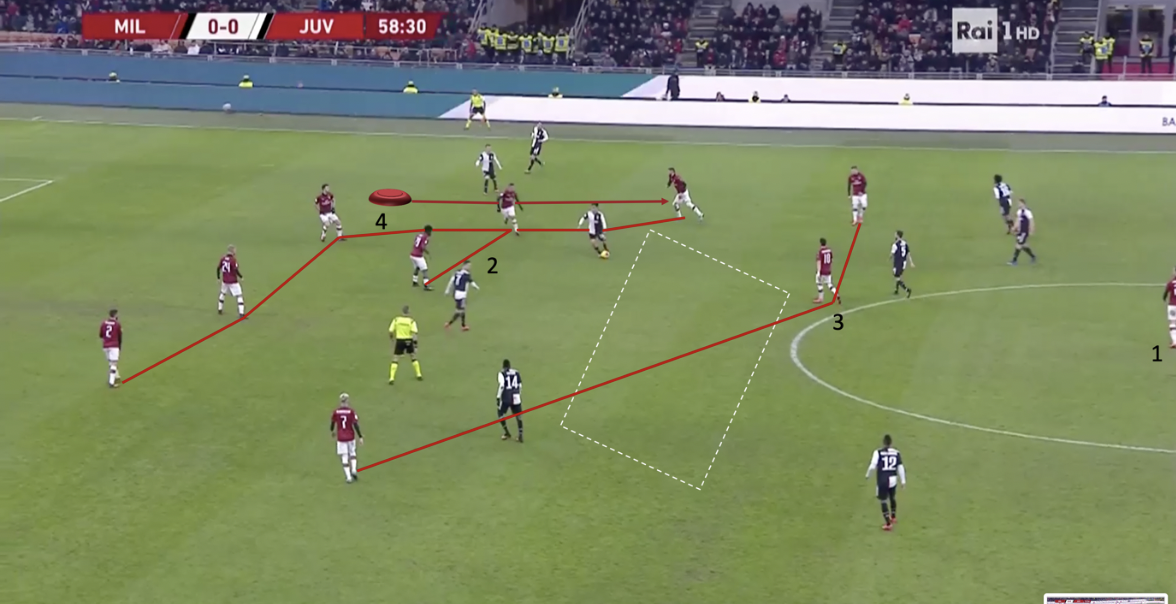

Continuing with the theme of prioritising right-sided attacks in the early phases of offensive organisation, the attacking midfielder or right-winger will supplement Kessié (who still continues to hold a wide position as Milan progress the ball) and Conti creating a triangle out wide.

If the attacking midfielder joins the triangle, Kessié and Conti will hold the extreme width, if it’s the right-winger, Kessié will stay slightly central while Conti and the winger hold width, as seen in the example shown below.

Once Milan have progressed far enough into the opponent’s half, they will use combination play to progress the ball horizontally.

Usually the first pass is to the attacking midfielder, who will look to feed the strikers and wingers who make penetrative runs.

In this phase, Milan’s positioning is quite structured.

Two players, usually Kessié and the right-back will stay near the touchline, the right-winger, attacking midfielder, defensive midfielder, and right-sided centre-back will occupy the right halfspace.

The striker and left-winger will be central, with the left winger deeper than the striker, acting as an auxiliary attacking midfielder.

The left-back (usually Hernández) will occupy the left halfspace, far enough wide to evade opposition, but central enough to threaten the opponent with a late run into the box.

For a left-back, Hernández is exceptional as a direct attacker, whereas most attacking full-backs focus on supplying crosses, Hernández is always an additional threat at goal, he has scored 5 goals this season, providing just 2 assists, showing how he is utilised as a direct threat more often than a supplementary player.

If the attacking midfielder is unable to feed the runners, he will look to play the ball into the feet of Ibrahimović, who is Pioli’s preferred striker.

If the attacking midfielder is entirely unable to get on the ball, the defensive midfielder (Bennacer) will make himself available, usually finding a large pocket of space, who will look to play to Ibrahimović, or feed the runners.

Ibrahimović’s hold up play is world class, and has the ability to consistently turn and get shots off on goal when he originally is facing away from goal.

If Ibrahimović is unable to shoot, he will lay off the ball to the left-winger, who is usually in space and has multiple options, in the below image, this sequence occurs and ends with Rebić feeding the ball into the run of Hernández, who has space to shoot due to Milan dragging the opponents to the right side.

This whole motion is quite similar to a traditional up, back, and through movement, but it differs as a normal up, back, and through sequence chiefly progresses the ball vertically, Milan’s overload and isolate combination play is more horizontal.

Although they prefer to build their attacking movements from the right side, Milan cannot always do so.

When attacking down the left, Hernández will be quite isolated, often forced into an early cross.

Milan try to avoid such a situation, as Bennacer will provide an option to Hernández to play away from the left side.

When the ball is in a central position, Milan will look to play wide, either circulating possession to the full-backs or playing directly to the wingers.

Occasionally, Ibrahimović can be used as a target man and can flick the ball onto runners beyond him.

Defensive organisation

Milan mainly defend in a 4-2-3-1 shape, with it transitioning to a 4-3-2-1 when defending on the wings, with the near side winger dropping deeper, in line with the midfield.

In the below example, Castillejo drops in line with the midfield when defending the right wing.

Their pressing intensity varies depending on the quality of the opponent they’re facing.

If Ibrahimović is playing, he’ll stay high up the pitch as he can be targeted in transition and can hold up the ball to bring others into play.

When the right back steps out to press, Kessié will shift to cover as seen in the image below.

Despite having fewer issues defending width as Giampaolo did, Pioli’s defensive system does have weaknesses of its own, with two major ones.

The first of which being very aggressive movement of defenders when they step out of the defensive line.

Often we’ll see an AC Milan defender vacate his position to press, many times this backfires, leaving massive gaps.

The second main weakness is large spaces between lines, in the two examples below, we can see both space in between the lines and aggressive defender positioning, leaving space in behind.

Conclusion

One could argue that Milan were wrong in the first place to sack Giampaolo, but what’s done is done, and we need to analyse whether or not Pioli is the right man to take Milan forward.

Pioli is doing an unremarkable job, keeping Milan in the race for the Europa League spots.

Milan have apparently been linked with other managers who are more suitable for long-term management and a rebuild seems to be on the cards.

This supports the theory that Pioli was hired by Milan as he is experienced with managing top Italian teams, and is a temporary solution to ‘steady the ship’ in the short to medium term.

Have AC Milan improved under Pioli? The short answer is yes, Milan have accumulated more points under Pioli per game than under Giampaolo.

However, given the tiny sample size of Giampaolo’s reign it’s difficult to draw an accurate conclusion.

With Atalanta’s place in the European spots in recent seasons, one of the so called ‘big’ Italian clubs will lose out on a top six place each season should Gasperini’s men continue to displace a team each season, it is up to Milan to ensure that they aren’t the team losing out on European football on a consistent basis.

Comments