This season one of the most remarkable turnarounds in European football has been the success of KV Oostende in the Belgian Pro League. The last term saw the Belgian side battling against relegation and only just surviving in the top-flight. Fast forward to this season and they have developed into one of the most interesting sides in European football and they are in touching distance of European qualification for next season.

Why though has there been such a turnaround at the Diaz Arena? It isn’t down to finances with only one player arriving for a fee this last summer, the forward Makhatar Gueye signed from Saint Etienne, while others arrived on loan, Jack Hendry from Celtic, or on free transfers in the case of Arthur Theate in defence from Standard Liege and my personal favourite Maxime D’Arpino in midfield from US Orleans. While Oostende are part of the Pacific Media Group, along with Barnsley, Esjberg, Nancy and Thun the intent behind the ownership group lies with the smart use and application of data in terms of player recruitment, but perhaps more pertinently in this instance with the recruitment of coaches.

Indeed, when looking in-depth at the performances of Oostende this season it appears that the catalyst behind their relative success this term has been the appointment of the 47-year-old German Alexander Blessin as the first-team coach prior to the start of the season.

Prior to moving to Belgium with Oostende, Blessin had spent his entire coaching career in various positions within the RB Leipzig system. Over the course of this season, we have seen clear indications that Blessin has adopted several principles of play that are synonymous with the preferred game model of teams within the Red Bull group. This extends from their model of play out of possession, with aggressive pressure in the opposition half, to in possession, with a more vertical approach to ball progression. What has also become abundantly clear is that Blessin has a tendency to trust and play young players.

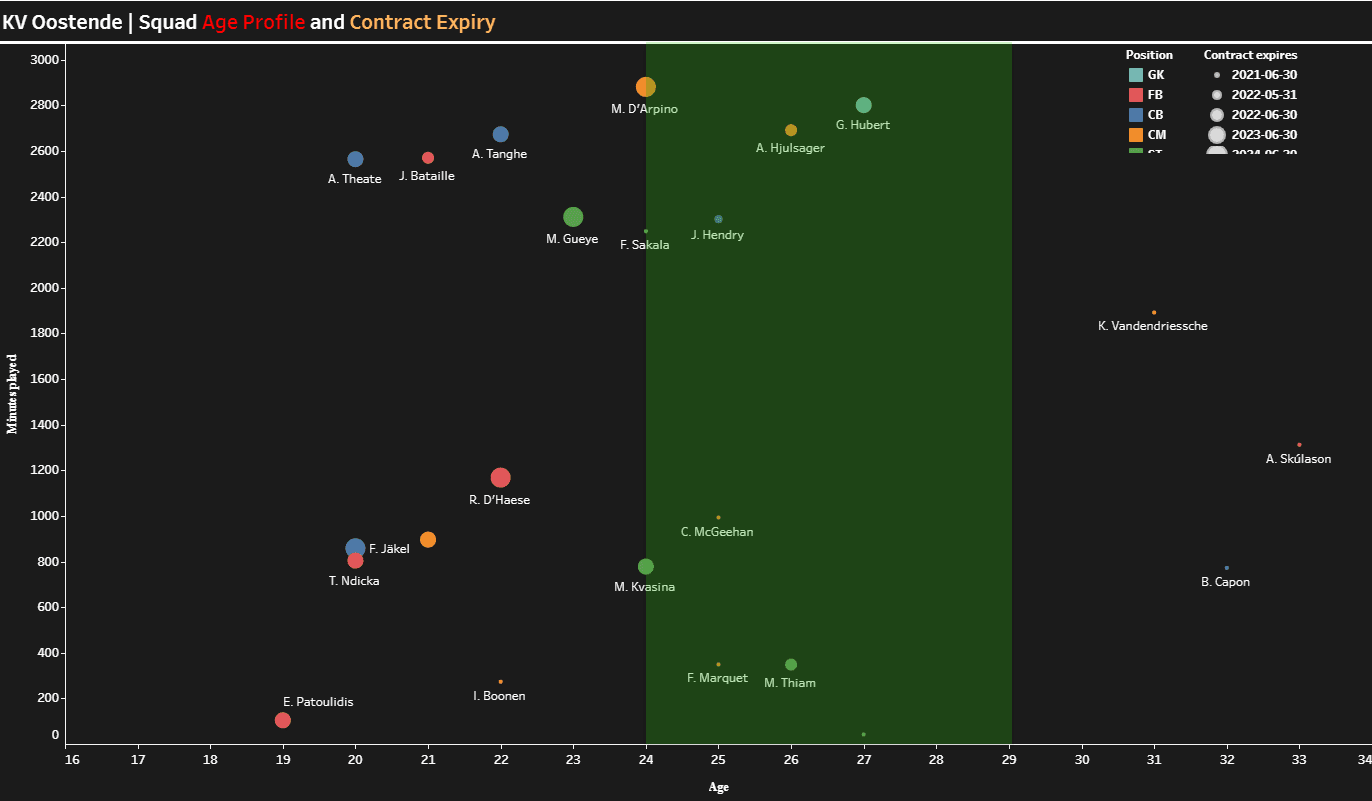

We can see from the above age profile for Oostende for this season, which shows player age and their minutes played this season along with contract expiry, that several key players are still to reach their peak age while those who are past their peak age, including the recently departed Ari Skulason are either playing less or coming to the end of their contract. With the Scottish defender Jack Hendry on loan from Celtic, there have already been talks between the two clubs surrounding a permanent transfer this summer.

Prior to starting this article, I spoke with two people whose knowledge of Belgian football far exceeds my own in Ben Jackson of the Belgian Football Podcast and the excellent @DrMukhrjeeS on Twitter. They both agreed that Blessin was the main reason that Oostende had been playing so well and both paid testament to how impressive the German coach had been in terms of creating a cohesive unit within the squad whilst also embedding not only a new set of players but a new set of playing principles that were different to those used by the previous regime.

As ever within football, however, success does not go unnoticed and clubs across Europe have begun casting admiring glances at Blessin. The most recent, and perhaps most serious, attention in Blessin has come from Sheffield United following their decision to part ways with Chris Wilder. The club are still, for now, in the Premier League although their relegation to the Championship looks all but certain. The club are looking for a new coach who will fit a very detailed brief. Tactical continuity is important and Blessin favours a 3-5-2 which is in keeping with the way that Wilder preferred to set up from a tactical perspective. The fact that Blessin favours the use of young players could also be important given that Sheffield United have a youth system that is promising to produce first-team players in the near future.

As the links to Sheffield United continue to grow and develop it feels like a good time to produce a tactical analysis of Oostende under Blessing to see just how the German coach likes his side to play. In order to do this we will consider how Oostende play in four phases of the game, the build-up, chance creation, immediate defensive transition and the established defensive phase through a combination of tactical and data analysis.

The build-up phase

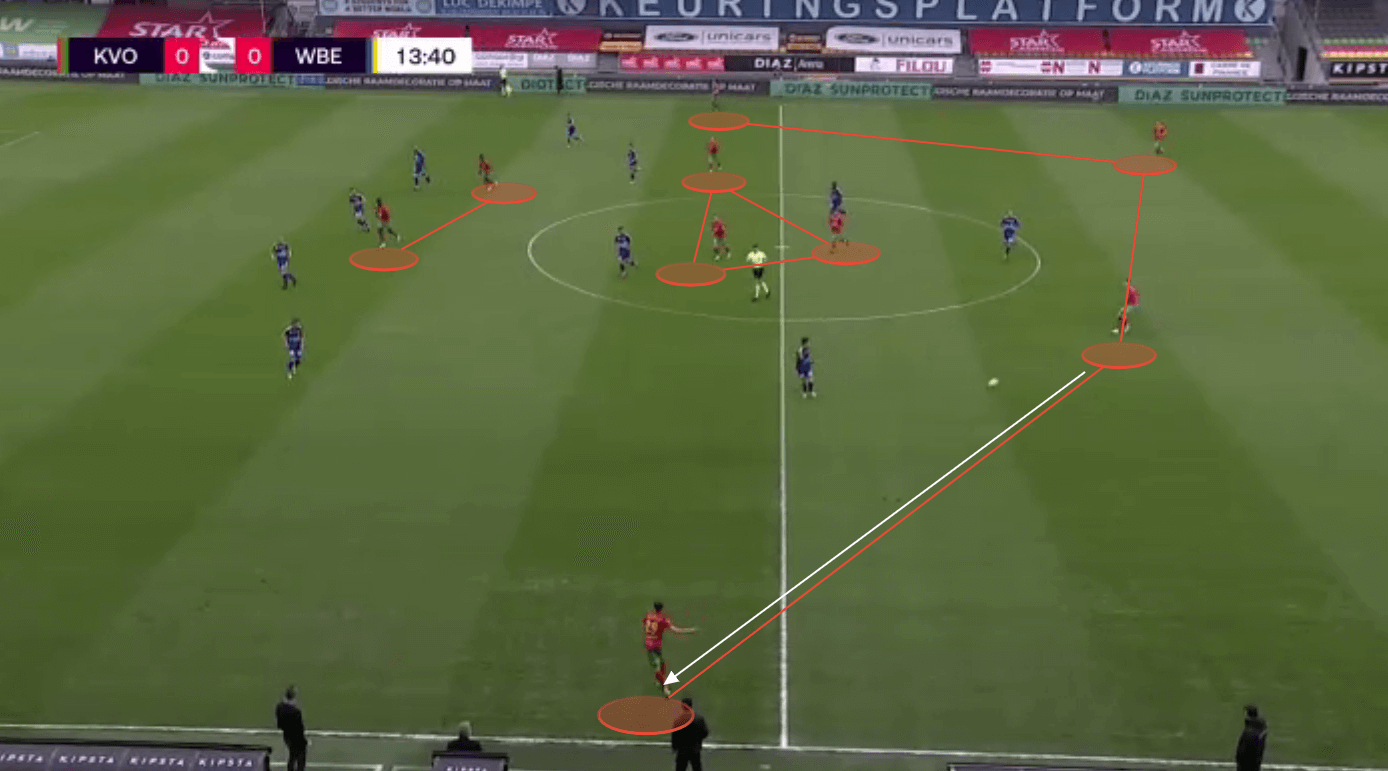

As mentioned above Oostende under Blessin play almost exclusively in a 3-5-2 shape with the wingbacks adapting their positioning depending on the phase of play or position of the ball. In the defensive phase, for example, they drop to the first line in order to create a back five. In the established attacking phase they push to the same line as the two ‘8’s and stretch the width of the pitch in the opposition half. It is in the initial ball progression phase of the build-up, however, that we see the most variance in this position. It is not unusual for the wingbacks to retain a second line position to allow the ball to travel forward cleanly before then moving to adopt a more advanced position to support the attack.

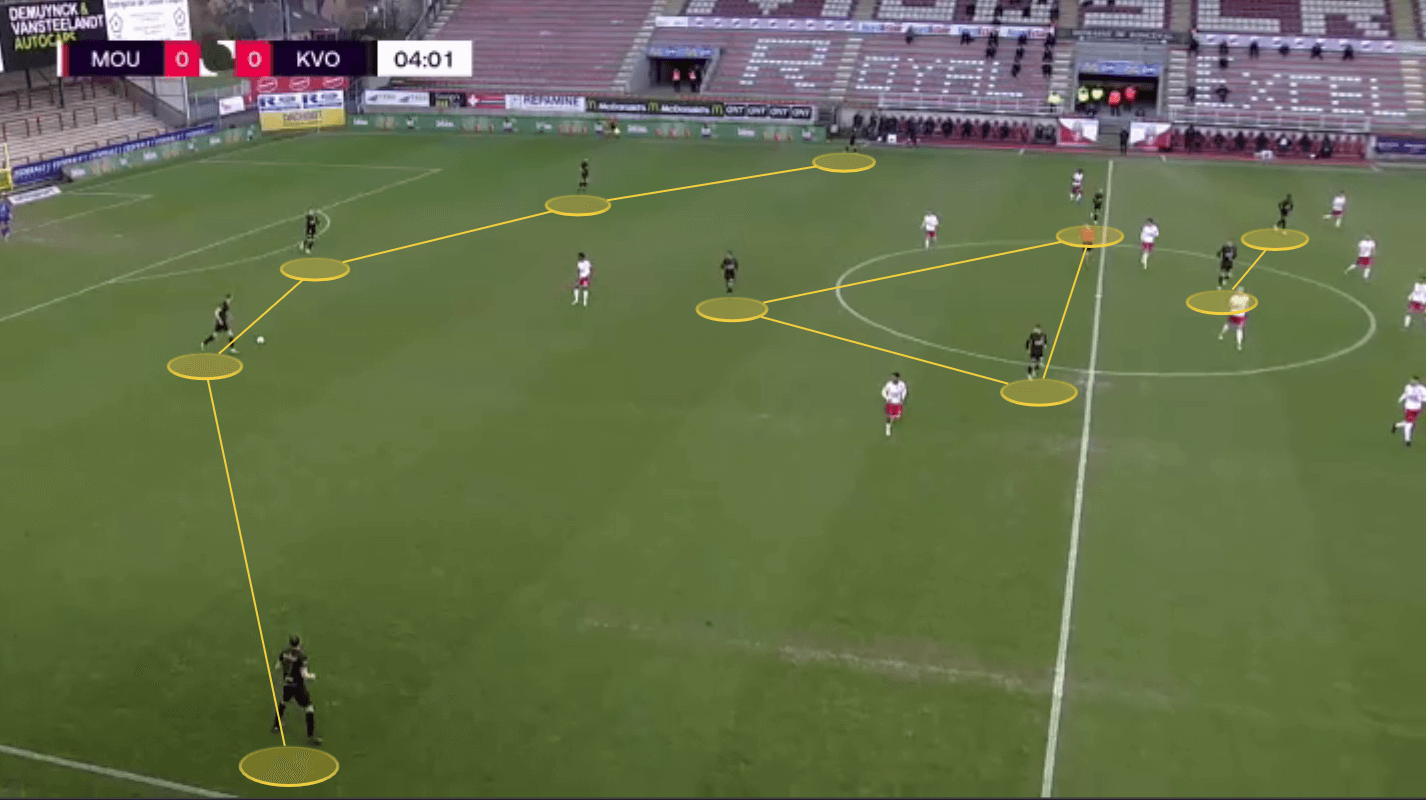

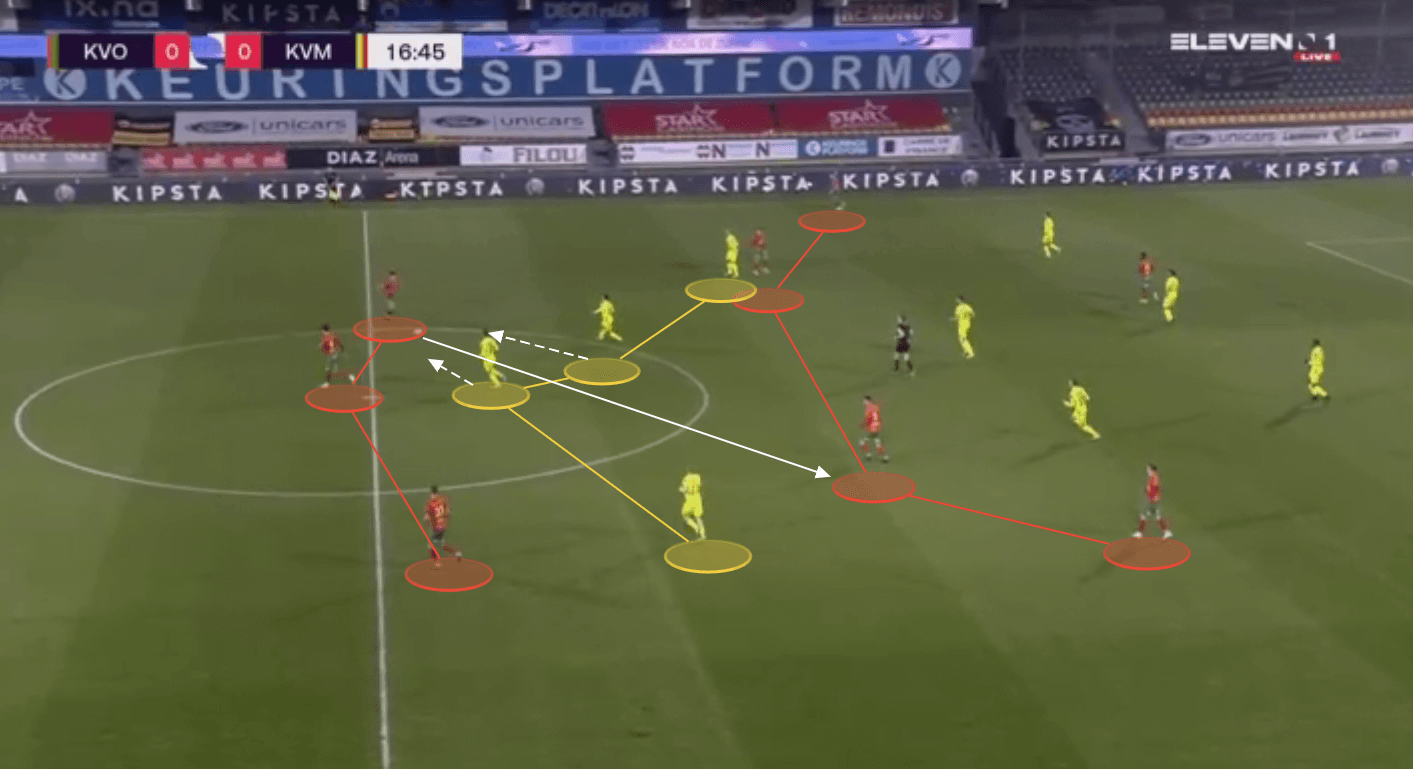

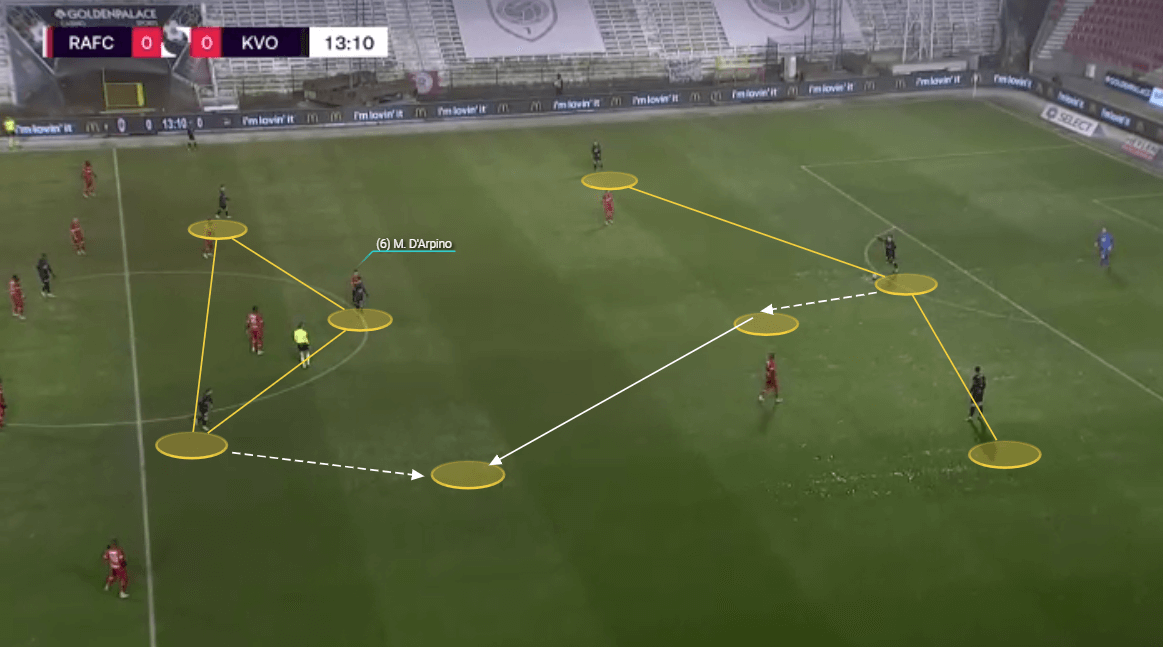

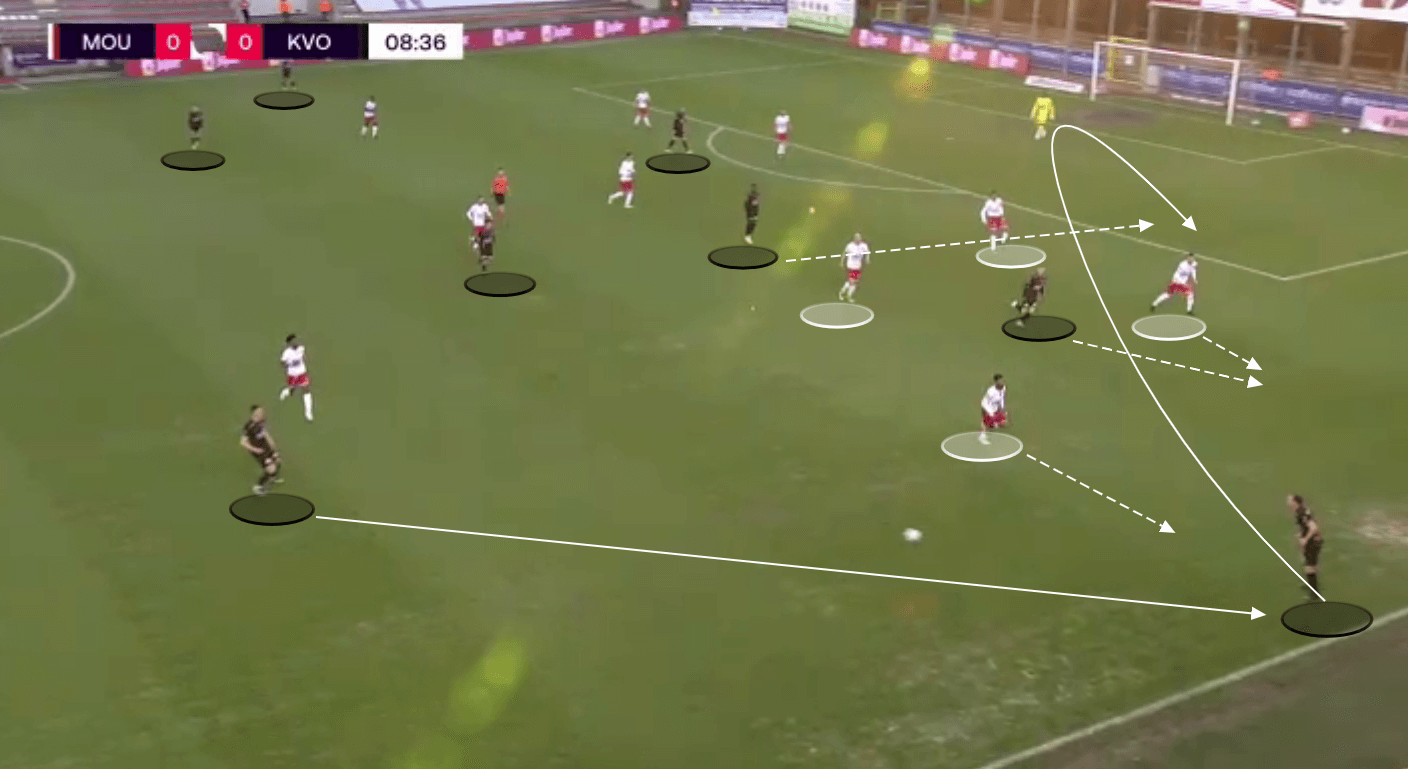

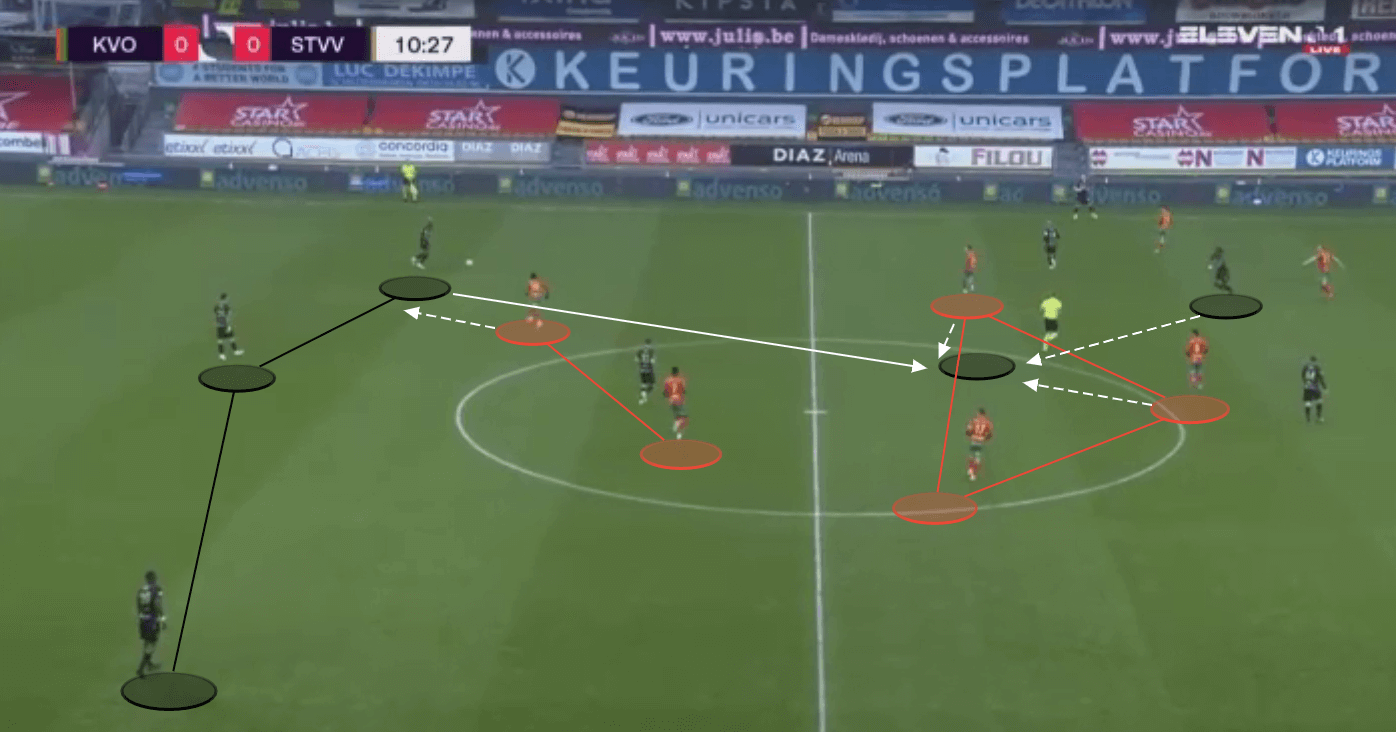

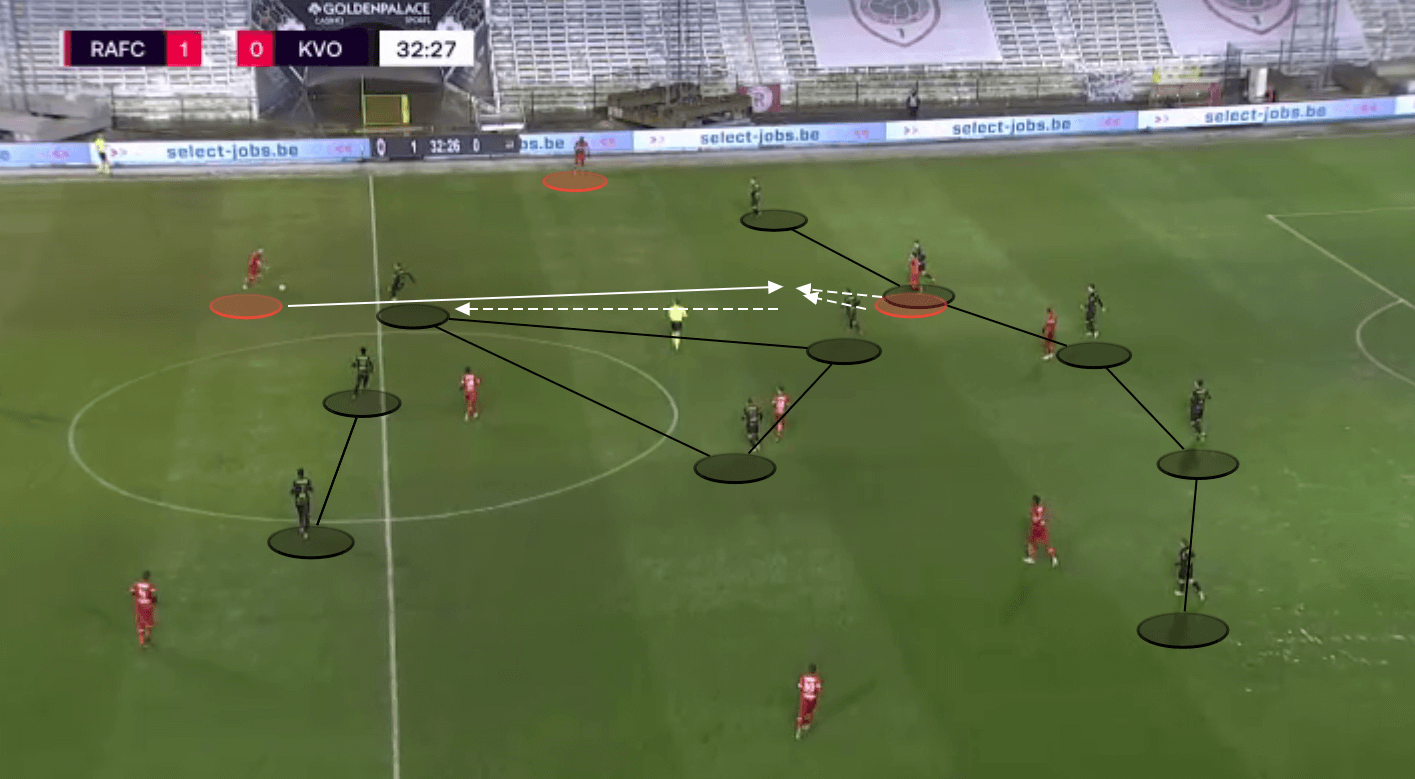

We see in this image the basic shape of the Oostende system as they are looking to progress the ball. The main ball progressors from the first-line are the wide central defenders where Arthur Theate, on the left and Anton Tanghe, on the right, are averaging 7.86 and 8.89 progressive passes per 90 respectively. This is compared to just 4.15 progressive passes per 90 from Jack Hendry as the central defender in the three. Maxime D’Arpino operates as the ‘6’ at the base of the midfield and he tends to work hard in terms of his lateral movement in order to either get free in order to receive the ball from the first line or to move out and create a passing lane for the central defenders to play a pass that accesses the two ‘8’s in a more advanced position.

Depending on the orientation of the opposition press the wingbacks represent the option for the ball to be played out quickly either via an easy diagonal pass from the central defenders or as a quick bounce pass should D’Arpino receive the ball and be put under considerable pressure.

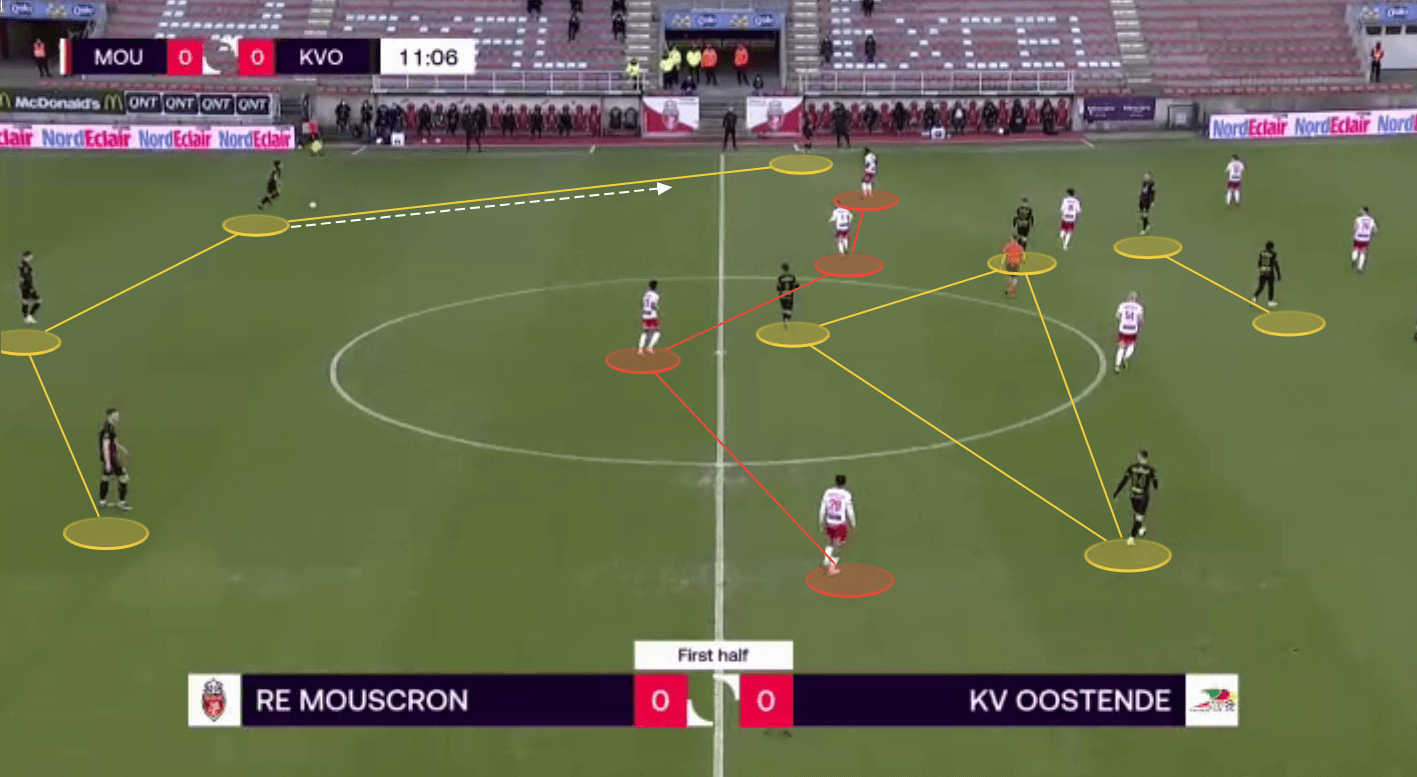

Here, for example, we see that Mouscron are sitting in a deep block with little intent to apply active pressure to the ball carrier on the first line. This takes away the opportunity for Oostende to play quickly and between the lines. Instead, Arthur Theate receives the ball in the LCB position and steps towards the opposition half with the ball. He then plays a simple pass to the left-sided wingback and stretches the width, forcing the opposition to defend wider and creating space for his teammates.

The key here is that Oostende obviously have a set principle in place, to ensure clean ball progression and break the first line of opposition pressure, but they also have the flexibility to adapt to what the opposition are showing them. This example achieves the same purpose, clean ball progression, but in a different way.

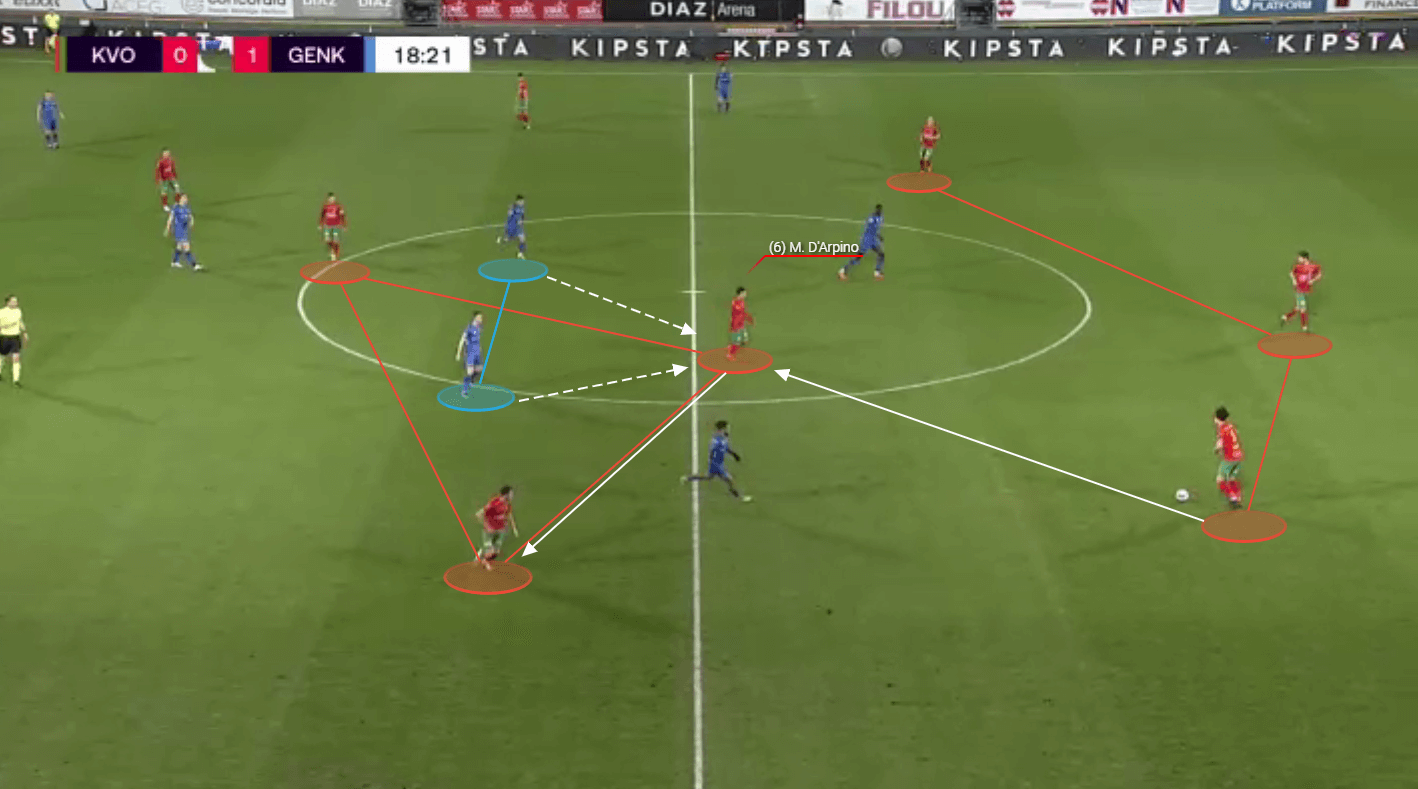

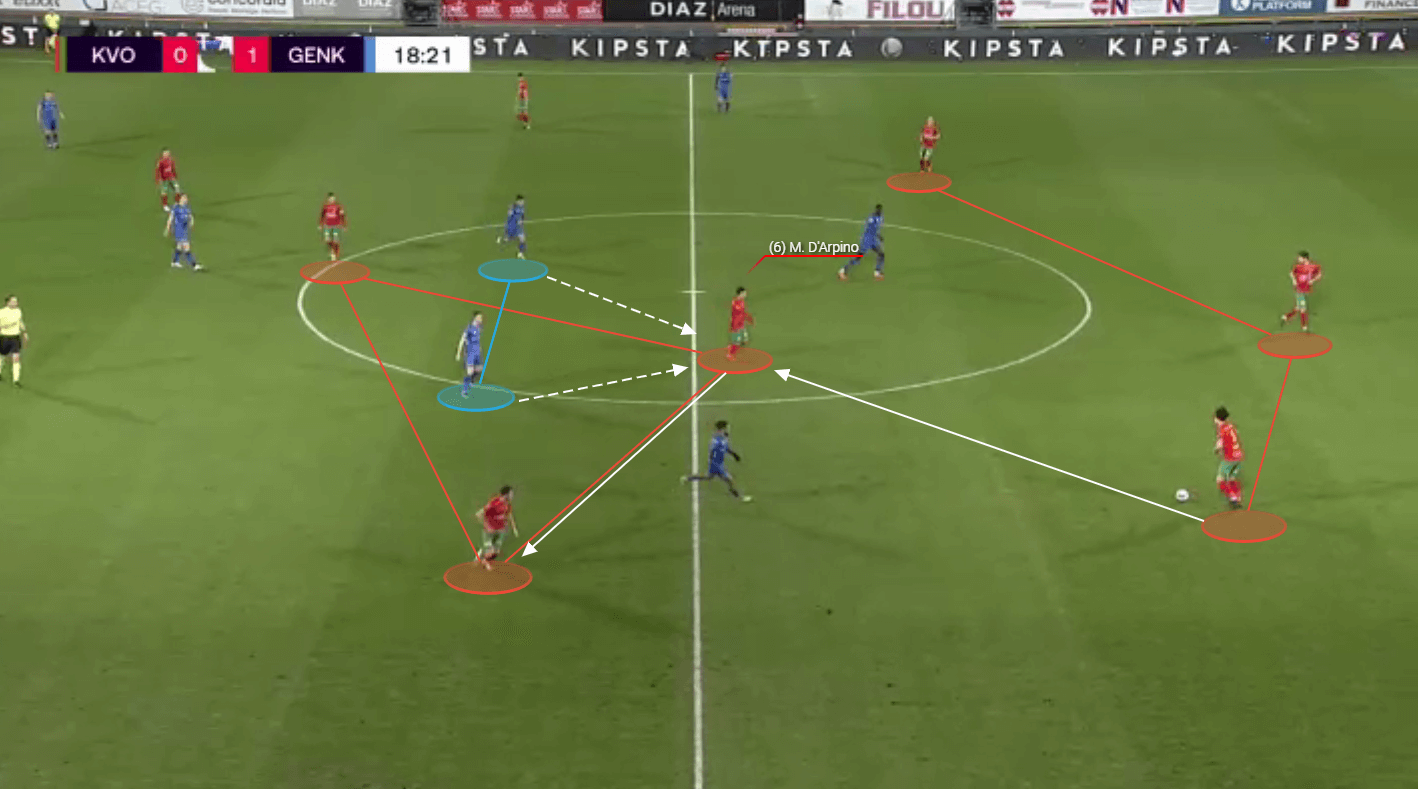

Here, we see an example from their game against Genk in which the pass to access D’Arpino is evident and Theate is again the player who finds the pass that outplays the first line of opposition pressure. As the Frenchman receives the ball, however, He is immediately engaged and pressed by two opposition players from behind. This is where the angle and position of the ‘8’s or wingbacks within the tactical structure becomes so important. As D’Arpino is pressed he is able to just quickly turn the ball around the corner to connect with a teammate on the near side. This essentially bypasses the two pressing midfielders and allows Oostende to progress the ball towards the final third with central superiority.

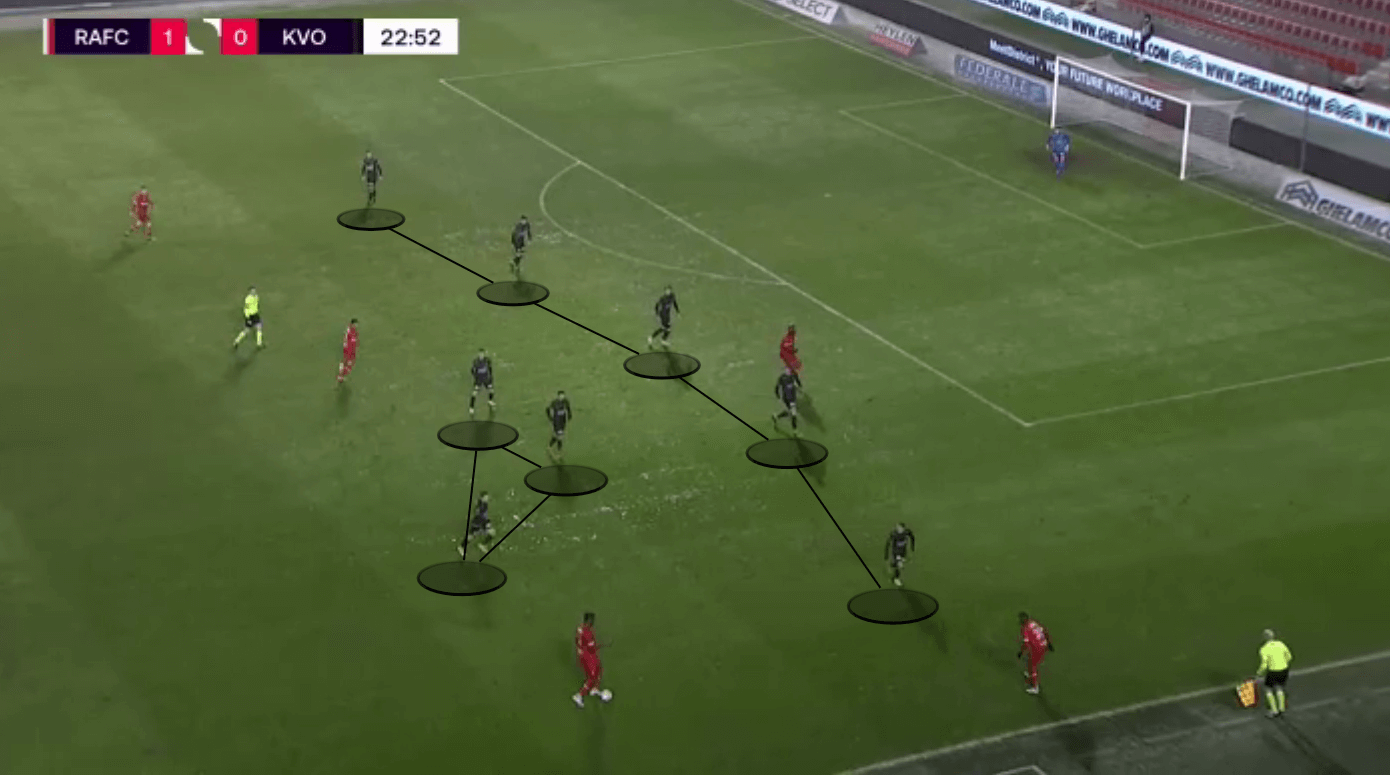

The ability of the wide central defenders to receive and play under pressure is one of the keys to the way that Oostende like to build out from the back and progress the ball towards the final third. Here, we again see an example of this and again it is Theate who has possession of the ball. There are two opposition players moving quickly to engage the ball and press Theate before he can find a passing option. Often in these situations, you would see the defender in possession look to play long and away from the press or back towards his own goalkeeper in order to escape the pressure. Instead, the young defender is calm and splits the two pressing players with a through ball that finds a teammate on the edge of the final third. This one pass effectively takes four opposition players out of the game.

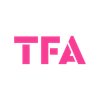

Here, we see another example of the tactical flexibility that Oostende shows when playing under Blessin. This time, the opposition have taken away the ball progression options of the two wide central defenders, the opposition strikers have split to cover them, and the ‘6’ as D’Arpino is covered. Antwerp have obviously done their opposition work thoroughly and understood that Jack Hendry is the worst progressive passer of the three defenders. They are essentially forcing Oostende to look to progress play and build-up through Hendry. As the, now, Scottish international is in possession he steps forward to further split the two opposition forwards. The near side’8′ then recognises that there are no safe passing options and he drops to the same line as the ‘6’ in order to receive the pass cleanly in the half-space. A creative and flexible solution to the problems that were presented by the opposition.

As you can see Oostende are a team who, under Blessin, play in a very specific manner when looking to progress the ball forward. They also, however, display a willingness to be flexible and create and this, in turn, suggests that the principles of play in this phase that Blessing wanted to implement have been well coached and well taught.

Chance creation

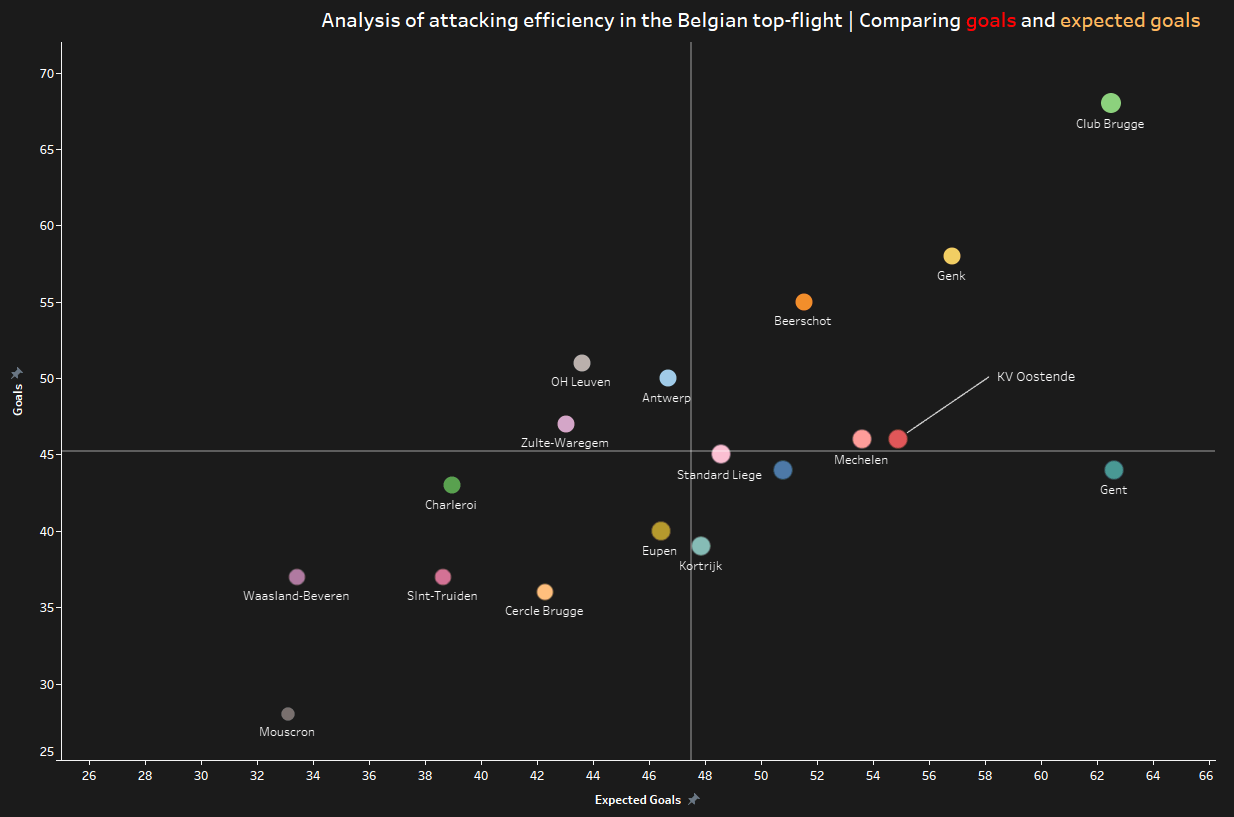

In term of chance creation and efficiency in front of goal, we can first turn our attention to Oostends’s performance in terms of goals vs expected goals. At the time of writing, Oostende have scored 46 goals in the Pro League although their xG sits at 54.89. This effectively means that they have underperformed expectations by 8.89 goals. With that said, however, they are just still in the golden top-right quadrant of our graph above.

The chance creation from Oostende largely follows on from the principles of play that we have seen in the build-up phase as Oostende clearly still prefer a measured approach with width and depth in the final third to create overloads against the opposition.

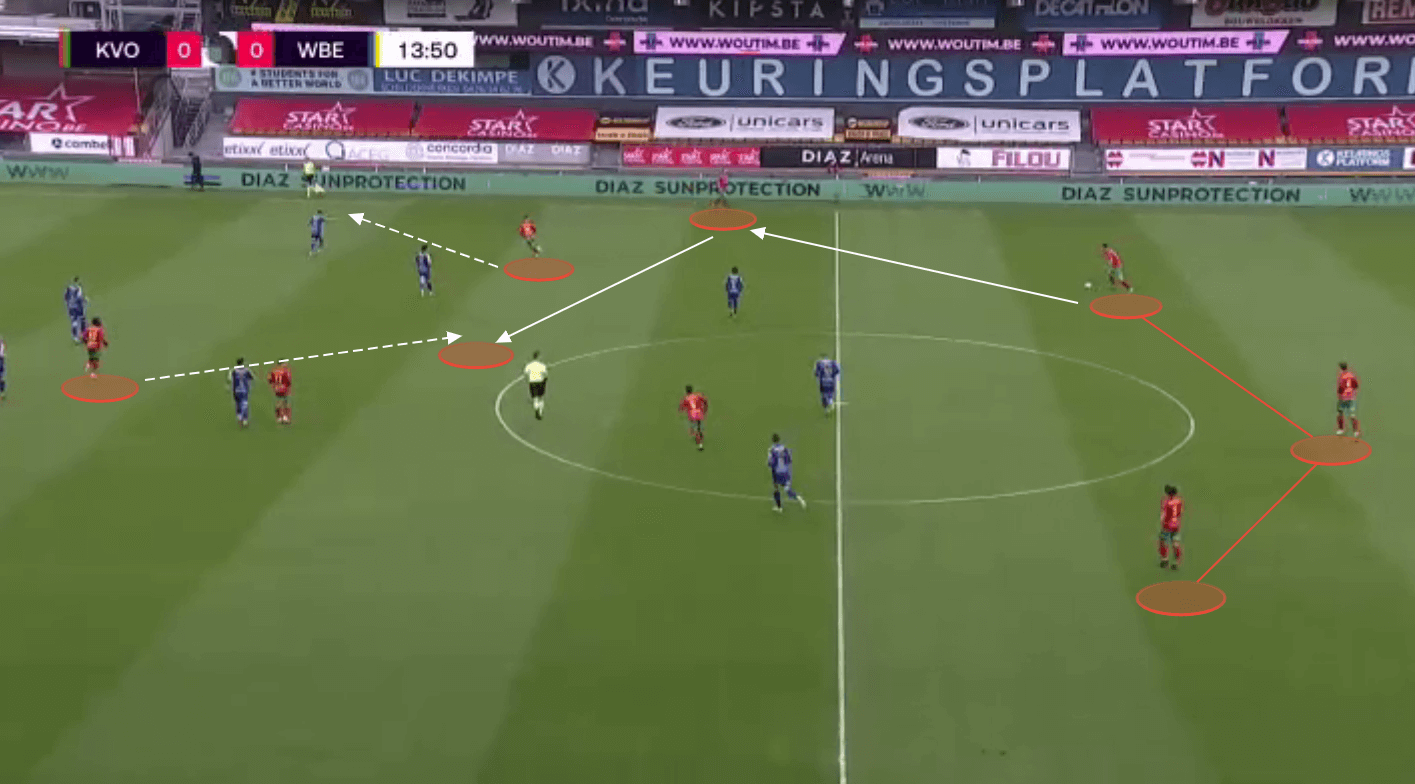

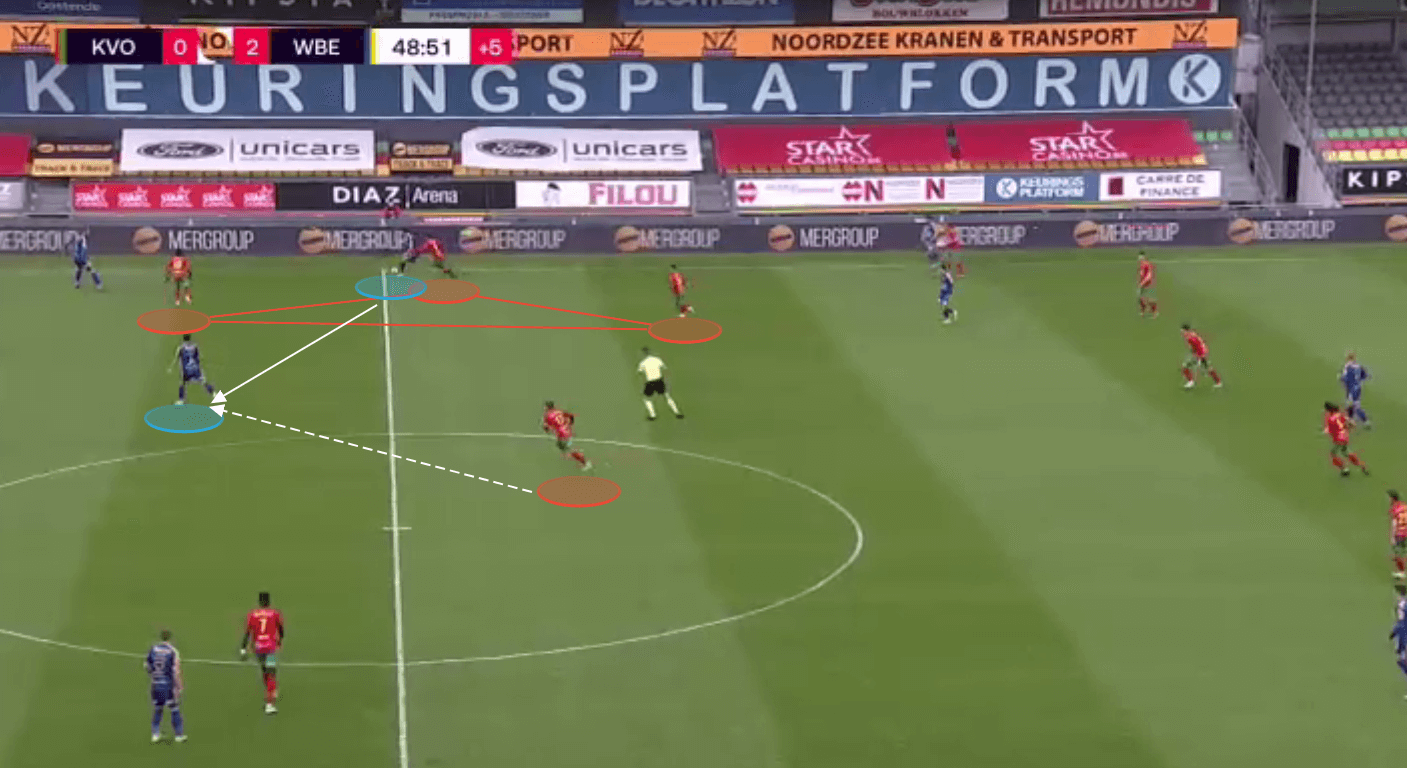

As mentioned earlier it is not unusual for the wingbacks to advance forward to occupy the same line as the ‘8’s in these situations with Jelle Bataille, on the right, being especially impressive in this regard. We see this in action above with Robbie D’Haese receiving the pass that accesses the wide area in which he has space to take possession and play. This pass immediately triggers the opposition to have to slide their block across in order to cover the wide space. This, in turn, creates the opportunity for space to open up for the ‘8’s and strikers as they move forward to occupy more advanced positions.

Rotations play a large role in terms of chance creation for Oostende with players understanding how and when to move out of pockets of space in order to drag defenders out of their slit and create opportunities for teammates. We see an example of this above as the ball is played out to Jelle Bataille in the wide position. As he receives the ball the nearest opposition defender has to move to engage and try to win the ball back. The near side ‘8’ also moves out to support in a slightly advanced position and this, in turn, allows the striker to make a vertical run past the defender in order to receive a pass into the area from Bataille.

Here, we see another example of rotation in order to create space in the opposition half. Again, the ball travels out to Bataille in the first instance and the ‘8’ on the ball side this time makes a vertical run away from the ball which attracts two defensive players away. This allows the striker to drop towards the ball in order to receive the ball at the edge of the final third in a pocket of space. This rotation and movement back towards the ball from the striker creates an advanced platform from which Oostende can attack into the final third and look to penetrate the penalty area.

For all of the talk so far of rotations and passes that break the line of the opposition there are times in which Oostende will look to play a more direct pass to the furthest line in order to quickly advance the ball and bypass a large portion of the opposition defensive block. We see an example of this here as the pass is progressed from Anton Tanghe as the right-sided central defender and finds the frame of Makhatar Gueye (195cm | 6’4″). The key, however, is the immediate intent from players from deeper positions and from wide to quickly move in and support Gueye as he receives the ball. This immediately creates opportunities for overloads in and around the opposition penalty area.

Pressing

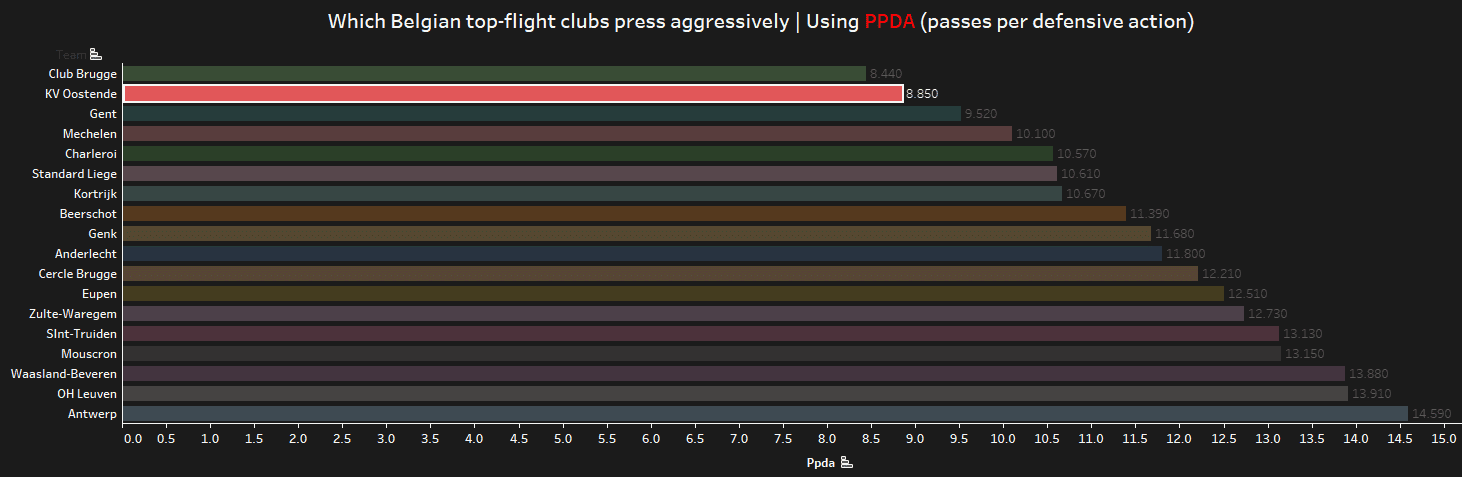

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a coach who developed at a Red Bull club, it is clear that Oostende under Blessin are an aggressive pressing team. As you can see from the graph above their PPDA (passes per defensive action) is, at 8.85, the second-lowest in the Belgian Pro League, behind only the league leaders Club Brugge. Oostende press both in terms of immediate transition and as the opposition penetrate into their own half and they tend to press with support and with groups making it very difficult for the opposition to easily play through the press.

The press is often triggered by one of the two strikers, often Fashion Sakala, who move to cut off lateral passing options for the defender in possession on the first line. This is designed both as an attempt to win the ball back but also to force the opposition to have to play forward. This is the case in this example as the defender has to play forward to a striker who has dropped into the midfield in order to receive the ball. As soon as the pass is played, however, and received by a player who is facing their own goal the press is triggered and two Oostende players move to regain possession of the ball and start the attack for their team.

This time we see an example of a second common pressing trigger from the Red Bull school as Oostende try to crowd and press the player that is in possession tight to the touchline. The press is escaped with a pass out into the central area but immediately we see a player moving to support the press and engaging the player who receives, once again facing his own goal. It is this support of pressure that is key for Oostende in not allowing the opposition to breathe when they are trying to progress the ball forward.

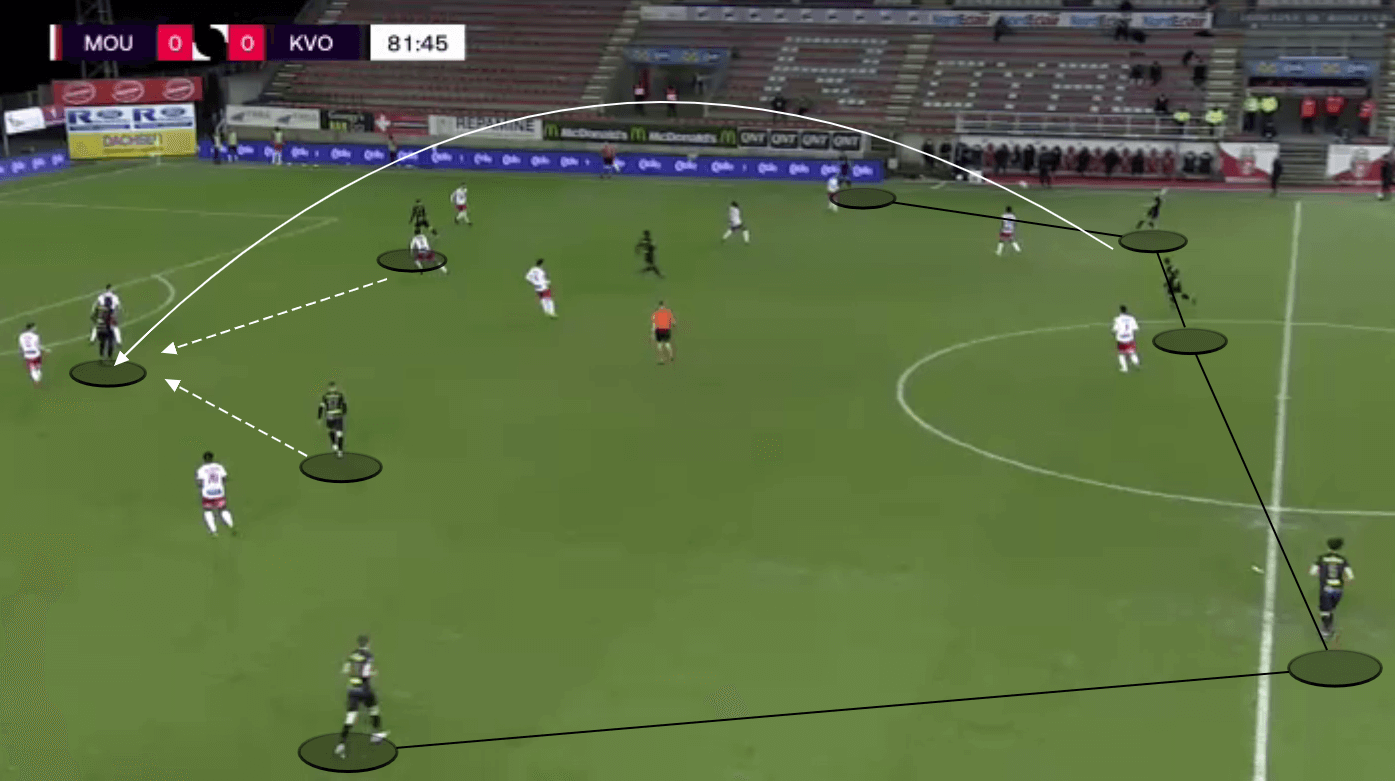

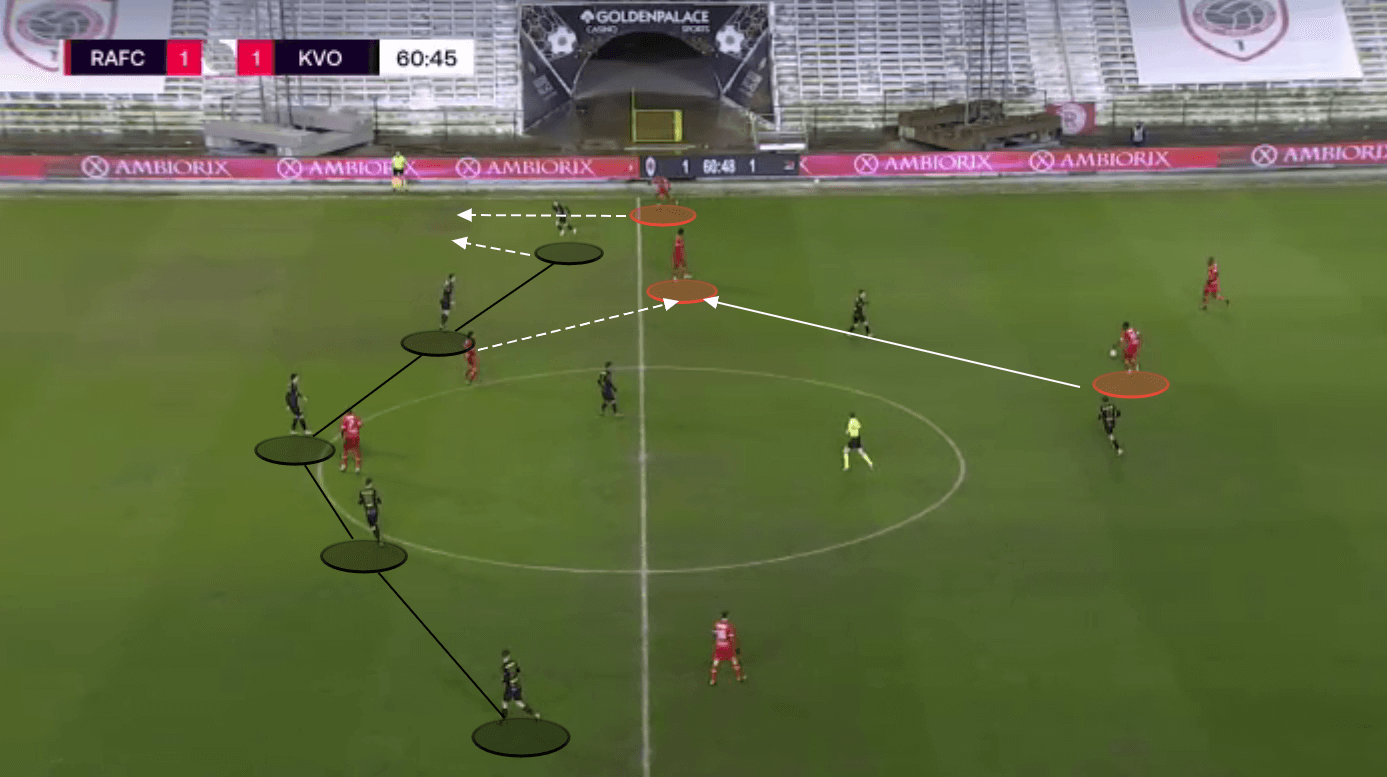

The press from Oostende also extends to the central defenders moving forward proactively in order to regain possession before the opposition attack can develop. In this example, the opposition are building from deep inside their own half and they have a player on the far side who is making a vertical run to break beyond the Oostende defensive line. That run is shadowed by the wingback on that side but this movement creates a clear passing lane to the opposition player who is positioned just inside his own half.

As the vertical pass is played towards this player though we see the central defender being proactive in coming out to win the ball back and regain possession for Oostende.

In pressing in this manner and, more crucially, in pressing with support Oostende are one of the most aggressive sides in Europe when it comes to regaining possession from the opposition.

Defensive organisation

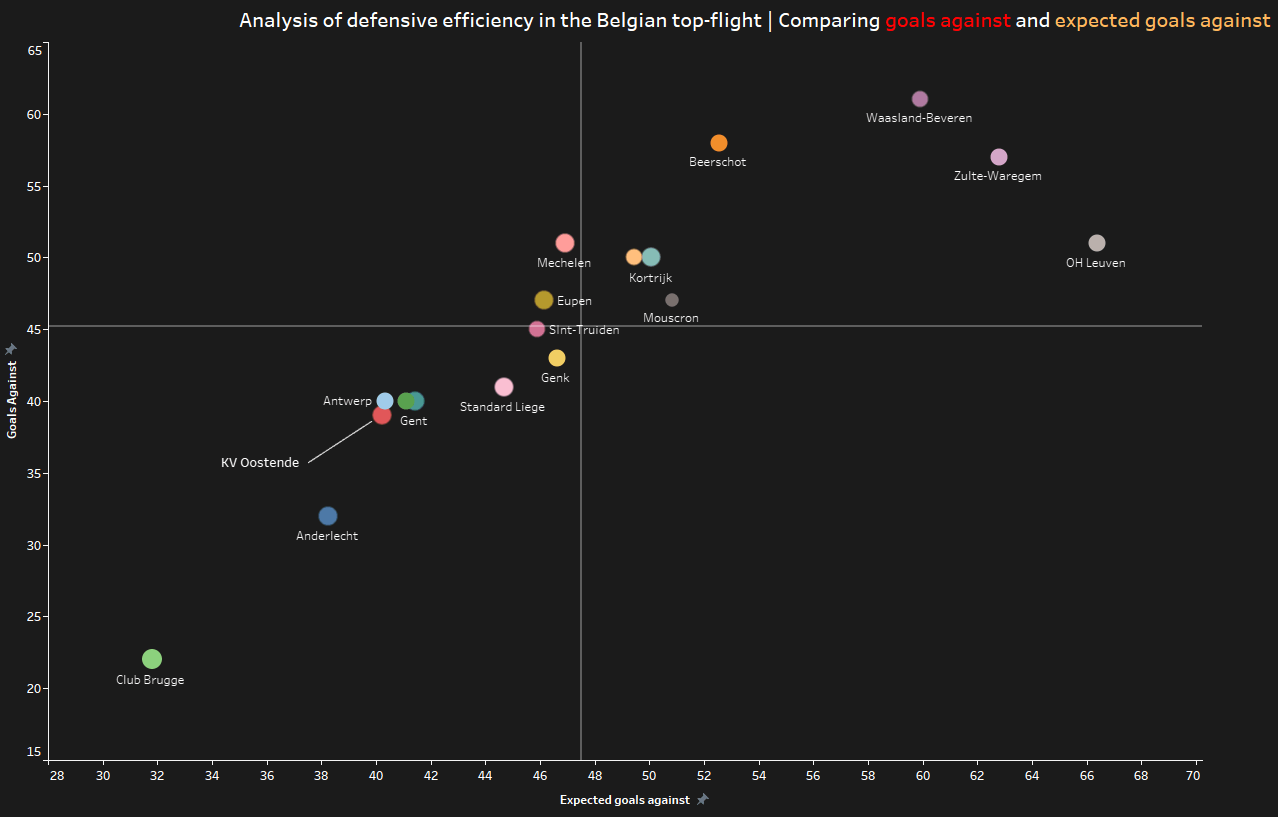

In terms of defensive organisation, it pays for us to first understand how Oostende have been performing in terms of goals against and expected goals against so far this season. On this occassion the bottom left is the ‘place to be’ with Club Brugge again performing as the clear standout. Oostende, however, are also very impressive from a defensive perspective and they have conceded 39 goals this season from an xGA of 40.21. An overperformance defensively of 1.21 goals.

The defensive structure from Oostende is flexible in that players can move out to press the ball without completely unbalancing the rest of the defensive structure. We see an example of this above with Antwerp in possession of the ball just inside their own half. One of the two ‘8’s has moved quickly to engage the ball carrier and this has created a pocket of space behind him. This is the pass that the opposition look to play in order to bypass the Oostende defence, as the striker drops to this space to receive, however, the defender who is covering him also drops and denies them the easy space to advance the ball. Notice the rest of the defensive structure is still balanced and the opposition have no space in which to attack into.

You can see that the defensive shape in the established defensive phase here. Both of the wingbacks are positioned in a deep position on the same line as the central defenders forming a back five with good spacing. the three midfielders are controlling the space in front of the defensive line, again in a compact shape, which means that should the opposition be able to shift the ball inside they will still meet a compact defensive shape that would prevent the ball from being moved easily into the central space.

Conclusion

There is no doubt in my mind that Alexander Blessin is a coach with a bright future in the game. The ease with which he has adapted to football in a new country, with associated language issues, while blending together a new set of players and instilling his own principles of play has been very impressive.

There is no doubt that representatives of clubs from across Europe will be watching Oostende and their coach closely. This is why a club like Sheffield United, who are actively looking for a new coach already, could have an advantage. Blessin appears ideally suited to a club like Sheffield United who wants to rebuild with a clear and concise game model running through the whole club.

Comments