They say a rock-solid defence wins games. You know what else they say? Offence wins games for the top clubs. Or, if you like cliches, “the best attack is a good defence”. What’s the answer to that one? You guessed it: “the best defence is a good offence.”

Here’s my advice. Pick whichever phrase suits your team or opinion, and roll with it. If for example your team is suited more towards attacking, or you just want to be more attacking overall, pick ‘the best defence is a good offence’. If you’re coaching the Crystal Palaces of the world, then maybe go with ‘defence wins games’. This way you can sell your team on parking the bus à la Mourinho in his Inter days in the hopes of securing a point.

My point being, there’s no need for a philosophical argument of what’s more important: both are. I’ll show you three great defensive keys you can use to shore up your goal-leaking team and win more games.

Let’s start with teaching your defence to understand where the most valuable real estate is when defending.

Never behind

If your back-line never allowed any ball in behind, it would make life a lot harder for opposing teams. In terms of high-value chances (as opposed to shooting 30 yards from goal), getting behind the back-line of the opposing team is obviously quite high on the priority list.

See how in the example below one good pass behind the back-line from the player in possession, and the striker would be in a really good position to score.

The near-side centre back, in this case, is too focused on the dribbler and has lost sight of the striker who could get behind him. His priority has become the dribbler when it should be the striker (who is more dangerous at this moment), and at all costs not allowing the striker to get behind.

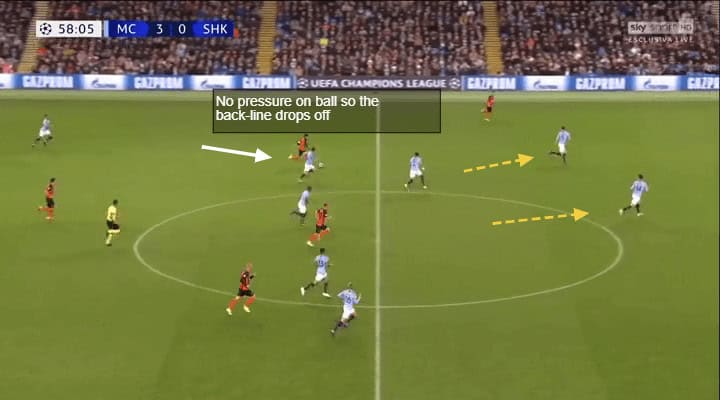

In this example, we see Manchester City doing a good job of protecting the space behind the backline. If there was pressure on the ball-carrier, which there isn’t, the centre backs could maybe hold their ground a bit more. With no pressure, however, that dribbler can easily penetrate them with one well-placed pass.

So how do we teach our teams to not allow balls in behind while not parking the bus?

The main reason the parked bus formula works so well is because there is no real estate left behind the back-line for good attacks to target. Of course, if you’re playing 2018 Manchester City, parking the bus will get you a one-way ticket to a solid 4-0 defeat.

The simple rule is that when you are defending and there is no pressure on the ball, your back-line should be dropping off. Just imagine David Silva dribbling at them with no defender near him. They still hold their ground thinking they are setting themselves for battle. With one beautifully weighted through-ball, Mr Silva will have set Sane on a break-away while your defenders are left wondering what just happened. A player without pressure can bypass a static defence easily. A back-line that is backing up in unison, however, is 10 times harder to beat with a through ball.

If there is pressure on the ball, your back-line can hold steady because the pressure means the attacking player’s head is down, and also the forward option should be covered. It’s why back-lines works as one and is constantly in motion. They want to constantly be squeezing space by moving forward, but only when they aren’t in danger of being penetrated behind.

Most back-lines can easily nail down the horizontal shifting, but most teams are no good at shifting vertically, which is easily just as important. Horizontal shifting is to avoid gaps between your defenders in the line so that no balls can be played between players. Vertical shifting is done in order to avoid balls being played over your defence. Notice how both are meant to stop, among other things, the ball being played behind.

It’s easy to shift horizontally according to the ball. It’s a little bit tougher to know when to shift vertically. However, this is usually because coaches do not know how to coach back-lines when to shift up or down. Remember, if the opposing player has the ball and there is no pressure on them, your back-line should be ready and dropping off. The second pressure is applied to the ball-carrier, or the ball is played backwards, they can move forward again to squeeze the space.

Delay, delay, delay

Delaying is critical. Let me demonstrate through a 1v1 example.

Good offensive players love defenders who just dive in. Diving in at the first moment possible is the opposite of delaying. Players who dive in with no intelligence provide the best case scenario for a good dribbler who can then completely beat you and have acres of space.

Now imagine the opposite: a player who just delays and retreats. Theoretically, if you were dribbling at someone who just kept on retreating, you would never get by them, and thus, would never fully beat them.

My point is that it’s really hard to beat someone who just retreats (delays). You can’t just delay the whole time, though. The issue is that most players and teams play the opposite way. They play as if you must engage at the very first opportunity.

Defences which engage at the first available opportunity allow way too many chances in the most valuable real estate on the field (see point one above). Defenders who do the same are not good at one-on-one defending, and are a liability to the entire team structure.

See how the defender looks, analyses, and realises if he engages, he will most likely lose the battle and then will leave his back-line even more out-numbered. This is one of the biggest keys to smart defending. You have to always be analysing and deciding when you should delay, and when you should engage.

Delay when you’re outnumbered, and delay until you’re covered. This is why we need intelligent defenders who think instead of simply rushing into the tackle whenever possible with the only thought being they must win the ball at all costs.

You can often prevent a great player, or even an attack where you’re outnumbered, simply by delaying and giving your team-mates a chance to get back and put the numbers in your favour again.

One up, three down

This is the core of some of the best defences we know about.

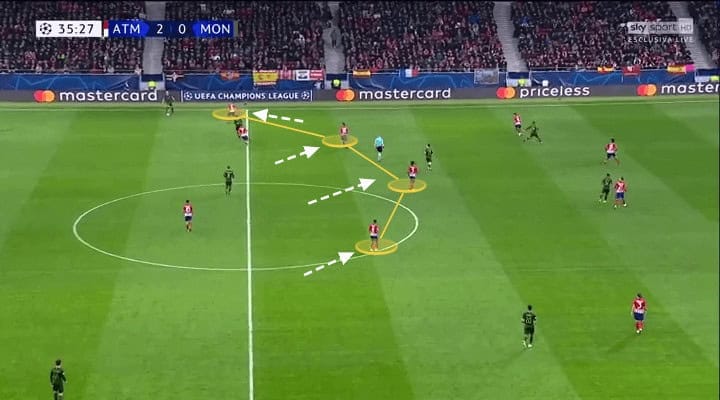

Look no further than Atletico Madrid. Watching them perform as a unit in order to shut down all space, allow zero shots, and take away all the creativity from the other team could be considered art.

On the other hand, Atletico Madrid are the last team you would want a casual fan to watch. If you appreciate an organized defensive juggernaut, though, then Atletico’s your team. They nail down the one up, three down concept that is crucial to having a great defence.

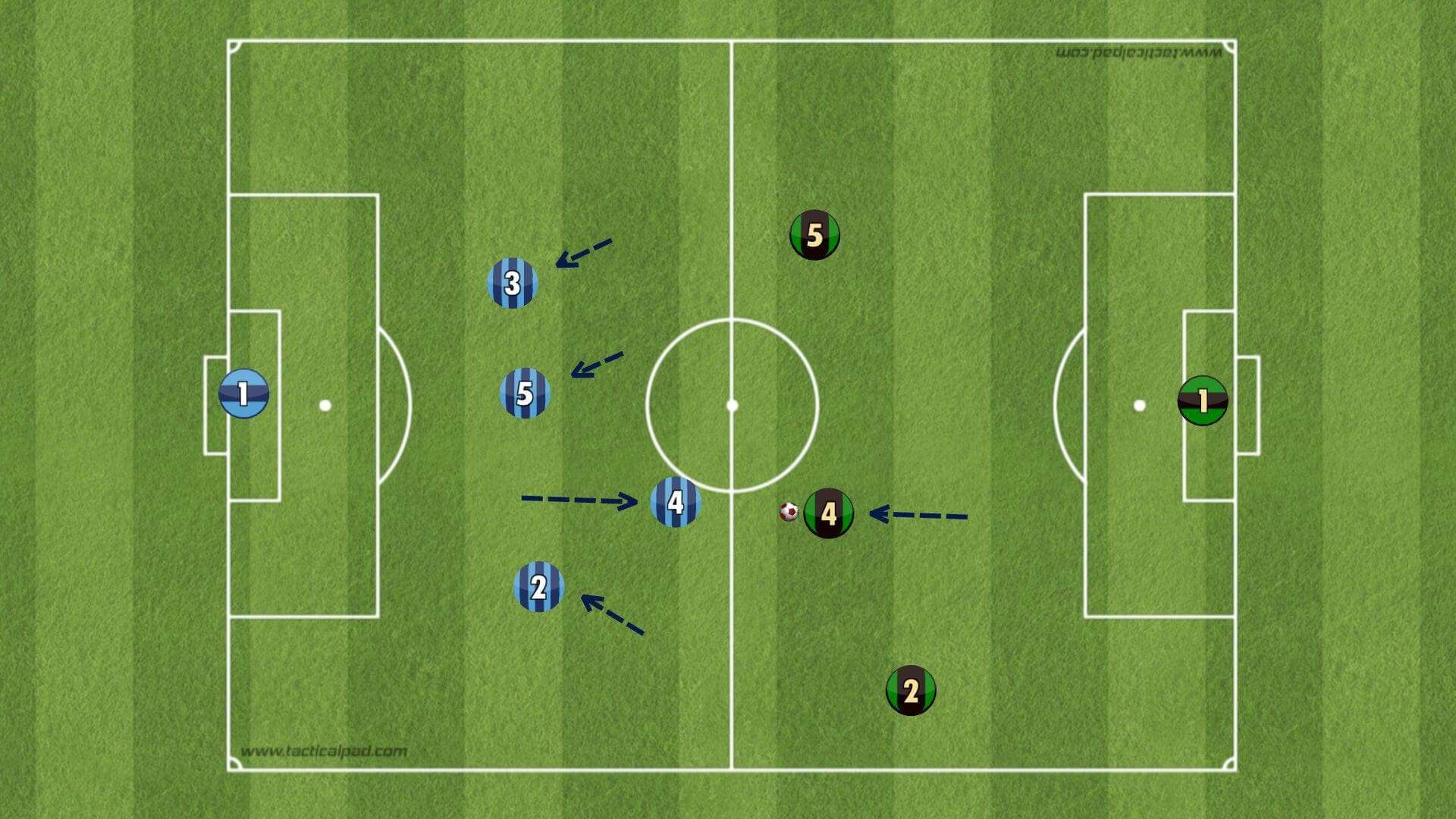

Barcelona only have three defenders here, which simply means it’s one up, two down in this scenario. Same concept. It is no different than if it was only two defenders: one would go, the other would cover. The issue is that coaches understand the concept from a two-man perspective. They don’t often enough teach an entire back-line how to apply the one up, three down principle.

Notice how the defender nearest the ball puts pressure, while most importantly the rest of the line (whether it be the midfield line or back-line), tucks in behind. One goes, the rest cover in behind. In fact, in the example above, Pique makes a mistake and would have allowed a break-away if the other defenders weren’t diligently tucking in behind to cover up.

Here you have the far winger pushing out to mark the player on the ball, while the rest of the line shifts over and behind. Tucking means to shift over and behind, not just behind. If players only shifted backward, and not in, then spaces would be open between the lines as well which has to be stopped. Remember, the player marking whoever has the ball pushes out while the rest of the line tucks in behind.

This principle basically covers all the most important aspects. It puts pressure on the ball, it provides cover behind, it covers gaps to stop through ball if tucked, and it provides balance through tucking.

Anytime a defender puts pressure on the ball carrier, or comes out to challenge a header, the rest of the line should be tucking in behind.

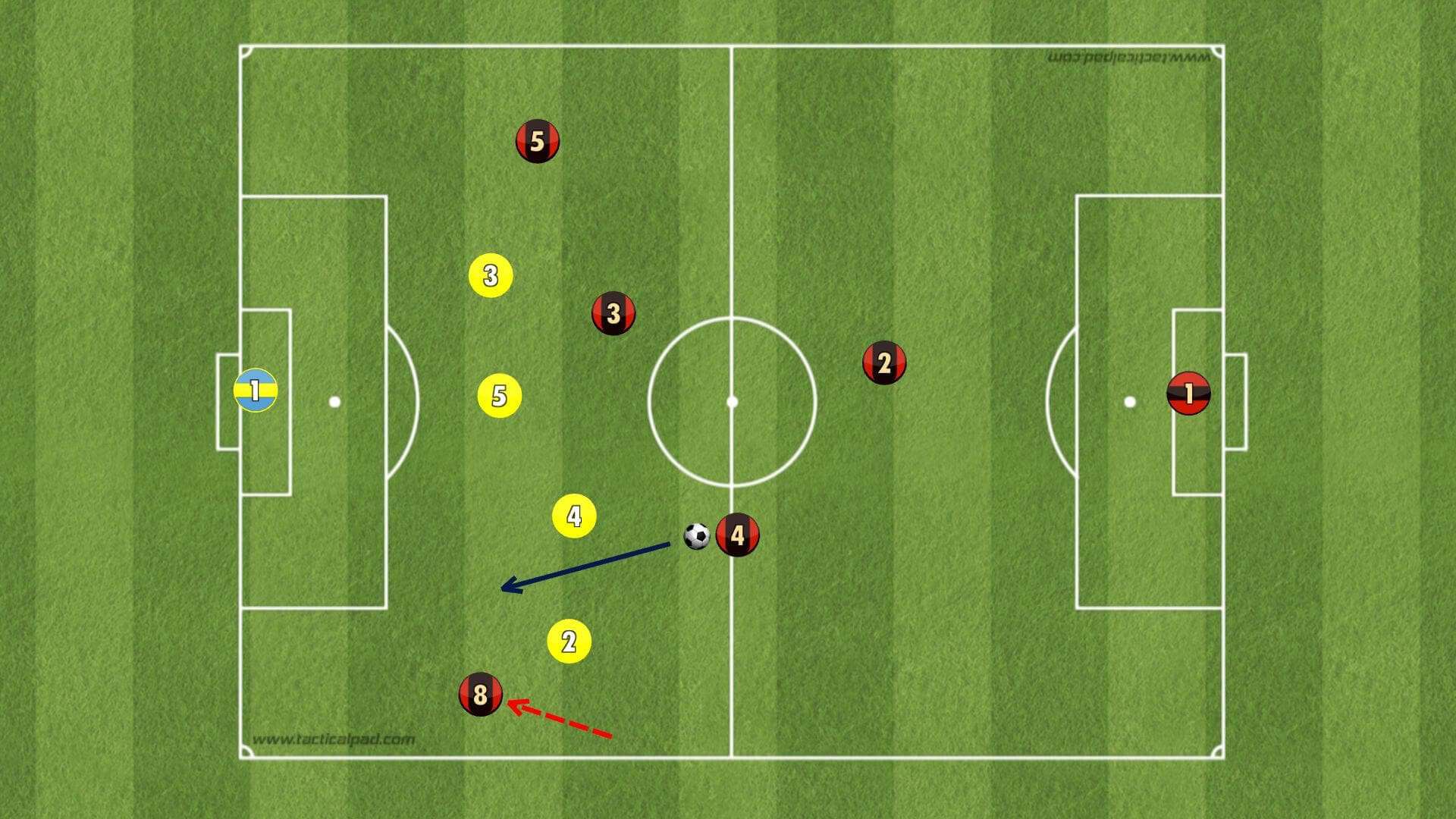

Some teams like Atletico nail it to a tee, some teams attempt it and have some success, and some teams don’t even know what it looks like. If for example two players in the line get caught high, gaps are open for the team on the ball to exploit with gusto.

See how by getting caught in a two up, two down scenario, there’s a massive gap for the ball-carrier to play a beautiful through-ball into? If #2 was tucked in behind like they should be, then there would be no space for a through-ball to be played into.

Also if the wrong player is caught high, i.e. not the player marking the ball-carrier, then gaps open up as well. It’s imperative that the defender in front of the ball carrier puts pressure while the rest of the line is tucked in behind.

If done well, the one up, three down concept is incredibly powerful. It takes some practice for players to synchronize well and to do it consistently, but it’s worth the work. Watch Atletico Madrid and you’ll start to understand why they’re so hard to break down. There are few concepts that show the break-down so quickly.

Train this principle and you’ll know every single time why it broke down. The ball got played through? Easy, two defenders were high while the other two were back. The ball got played through your lines again? Easy, the ball-near defender didn’t put pressure on the dribbler which opened gaps to play through. As a coach, you’ll be able to pinpoint where your team made mistakes in the one up, three down concept immediately.

There you have it: three keys to building a rock-solid defence to win more games. Alternatively, you can jump on the team bus, park it in your 18-yard box and you won’t worry about having to apply any key defensive principles. You might not ever see the other goalkeeper of course, but is that really important?

Your call.

Comments