Ligue 1 has been a rather predictable league for quite a while now with Paris Saint-Germain dominating the league since 2012/13 (although Monaco did break their championship streak in 2016/17). Strangely enough, legendary club Marseille, who are known as one of the most powerful clubs in France and the joint-most winners of the top tier of French football alongside Saint-Étienne – haven’t finished in the top three since 2012/13.

This year though, they have a chance to lift the curse and finally finish in the top three and perhaps even win the league if they’re lucky. Thanks to the brilliance of Portuguese tactician André Villas-Boas, Les Phocéens are currently sitting second in Ligue 1 behind none other than PSG.

In this tactical analysis, we’ll take a closer look at the philosophy and tactics behind Marseille’s success under the guidance of Villas-Boas.

Preferred formations

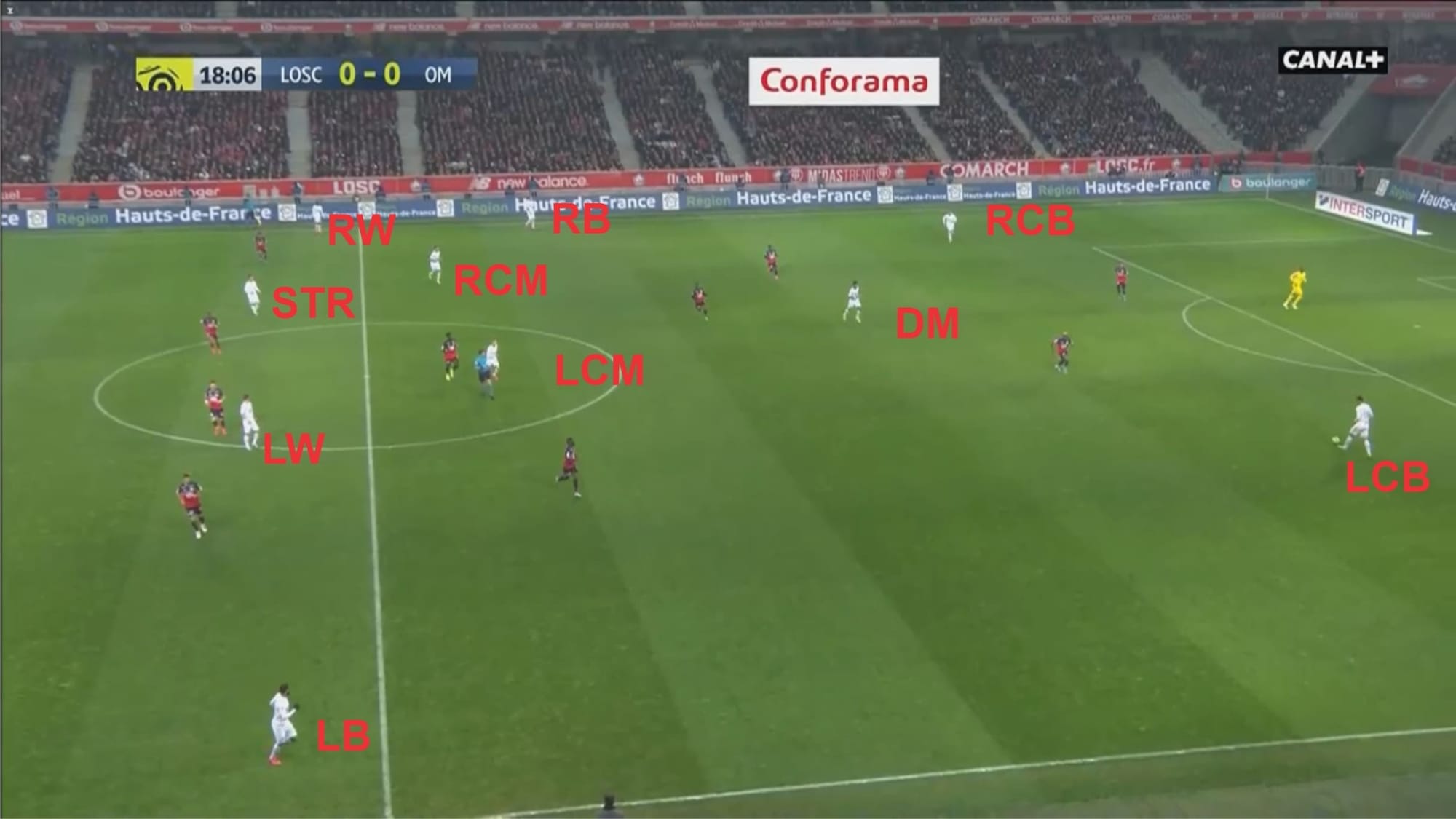

At Marseille, Villas-Boas is consistent in terms of tactics and system that he uses throughout the season. The Portuguese manager mainly uses 4-1-4-1 or 4-3-3 formation (those two are essentially the same formation), although at certain games he’d adopt a 4-2-3-1 formation and its variations (4-4-1-1, 4-4-2). Most of the times, when playing in a 4-2-3-1, 4-4-1-1, or 4-4-2 formation, the attacking midfielder or the second striker is given freedom of movement. Often this player would go from one side to the other, helping the team combine and create overloads in parts of the pitch.

Usually, in a 4-3-3 or 4-1-4-1 formation, either Boubacar Kamara or Kevin Strootman (and some other times, Valentin Rongier) plays as the defensive midfielder. The characteristics and attributes of these players are quite different though and this may have an effect on how Marseille play. Kamara’s tasks (when playing as a defensive midfielder) is mainly defensive. He’s the one who’s tasked to destroy opposition attacks and distribute the ball towards more creative players. Less playmaking, more defending. This is why the two centre-backs tend to play the ball directly to the full-backs rather than giving the ball to Kamara. Either that or one of the two eights will drop so that the centre-back can play the ball to him. If the access to full-back is blocked, then the centre-back will try to either pass the ball to Kamara, play the ball long, or drive forward himself.

Meanwhile, Strootman and Rongier are both quite solid in defence and proficient in playmaking. Usually, if central access is not blocked, these two players are vital and relied upon quite a lot to progress the ball and distribute the ball around.

Directness and verticality in attack

Under Villas-Boas, Marseille have turned into a very direct, straightforward, and vertical-oriented team. Despite that, they don’t use a lot of long balls, but they rely on quick short-medium pass combinations. They’d look to get forward as quickly as possible. Players often use only one or two touches when combining which gives their opponents less time to react to their actions. This is why Marseille’s attacks are quite hard to anticipate.

They mainly look to combine on the half-spaces and flanks and create chances from there rather than attacking centrally. The wingers (particularly Payet and Thauvin) usually will try to drive inside the box and try to take a shot or deliver a low cross there. At times, those two may also look to cut inside and curl one from outside the box.

Their use of direct, aggressive runners/carriers are also visible. Having the likes of Bouna Sarr, Jordan Amavi, Dimitri Payet, Morgan Sanson, Nemanja Radonjić, and Florian Thauvin really helps the team a lot in terms of progression, space creation, and chance creation, especially as the team rely on the wide players a lot due to their tendency to combine and attack through the flanks. The full-backs are often seen carrying the ball forward from the back. Meanwhile, if the wingers receive the ball in advanced areas, it’s not rare to see them trying to drive into the box themselves rather than crossing from out wide. Meanwhile, it’s also not rare to see Sanson dropping to receive and then marauding forward with the ball and skipping past defenders all by himself.

Marseille most often look to play from the back with the goalkeeper playing the ball short. However, against teams with aggressive, high pressing, they’ll occasionally look to play the ball long either into space behind the opposing defence or in front of the opposing defence (and win second balls there). As mentioned before in this tactical analysis, they’re very direct and will break forward very quickly if they manage to find gaps to exploit. However, against teams with disciplined defence, whether it be medium or low-blocking teams, they’d be forced to play more patiently, moving the ball around and disrupting the opposition’s defensive structure so they can progress the ball and attack.

Often the two centre-backs are separated and sit quite far from each other. Meanwhile, the defensive midfielder tends to sit in front of the defence, creating a triangular shape with the two centre-backs instead of dropping and sitting in between or beside them.

The two eights usually sit quite high up the pitch and occupy the half-space. One of them occasionally would drop to receive if the centre-backs are struggling to find gaps to progress.

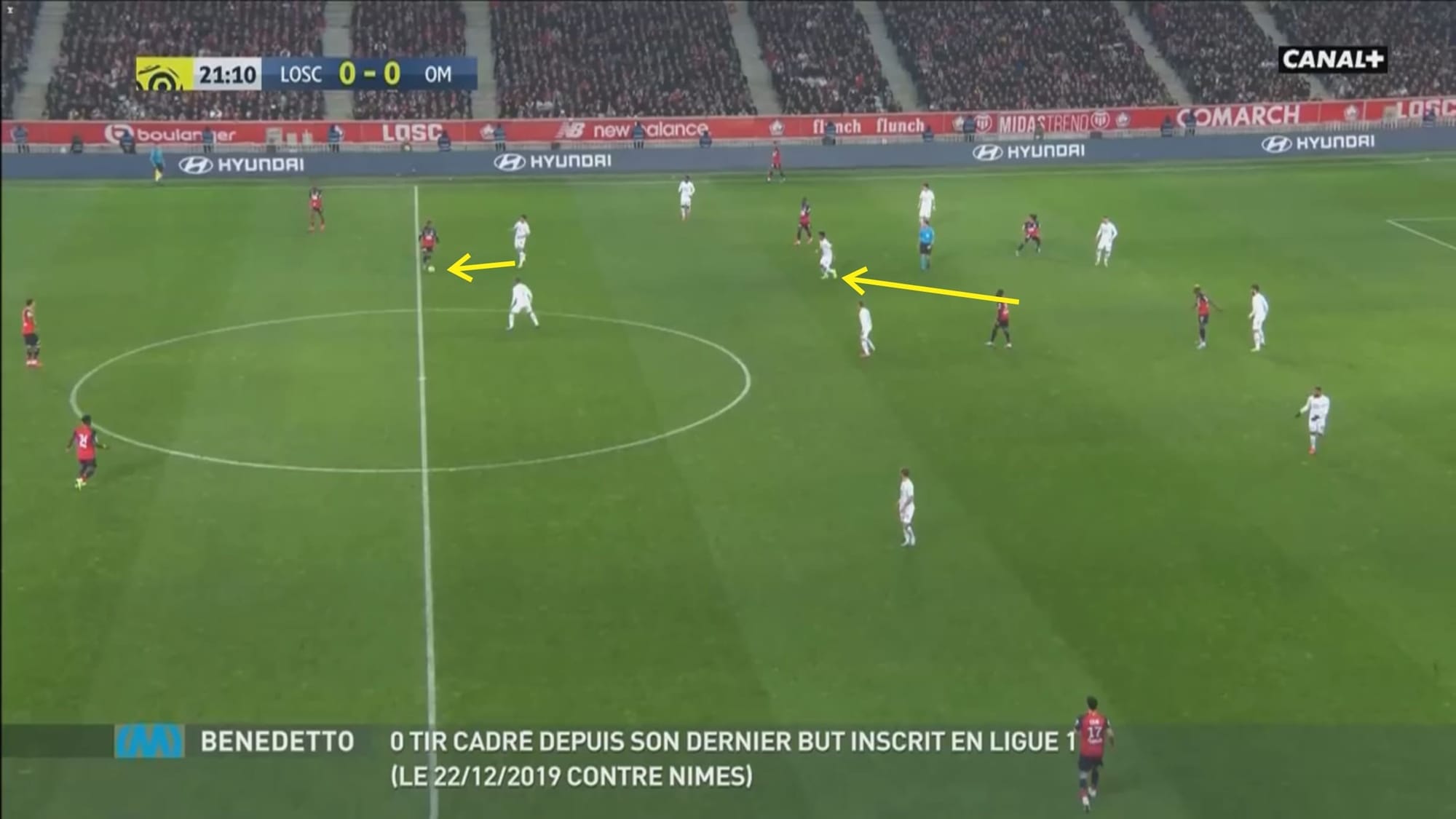

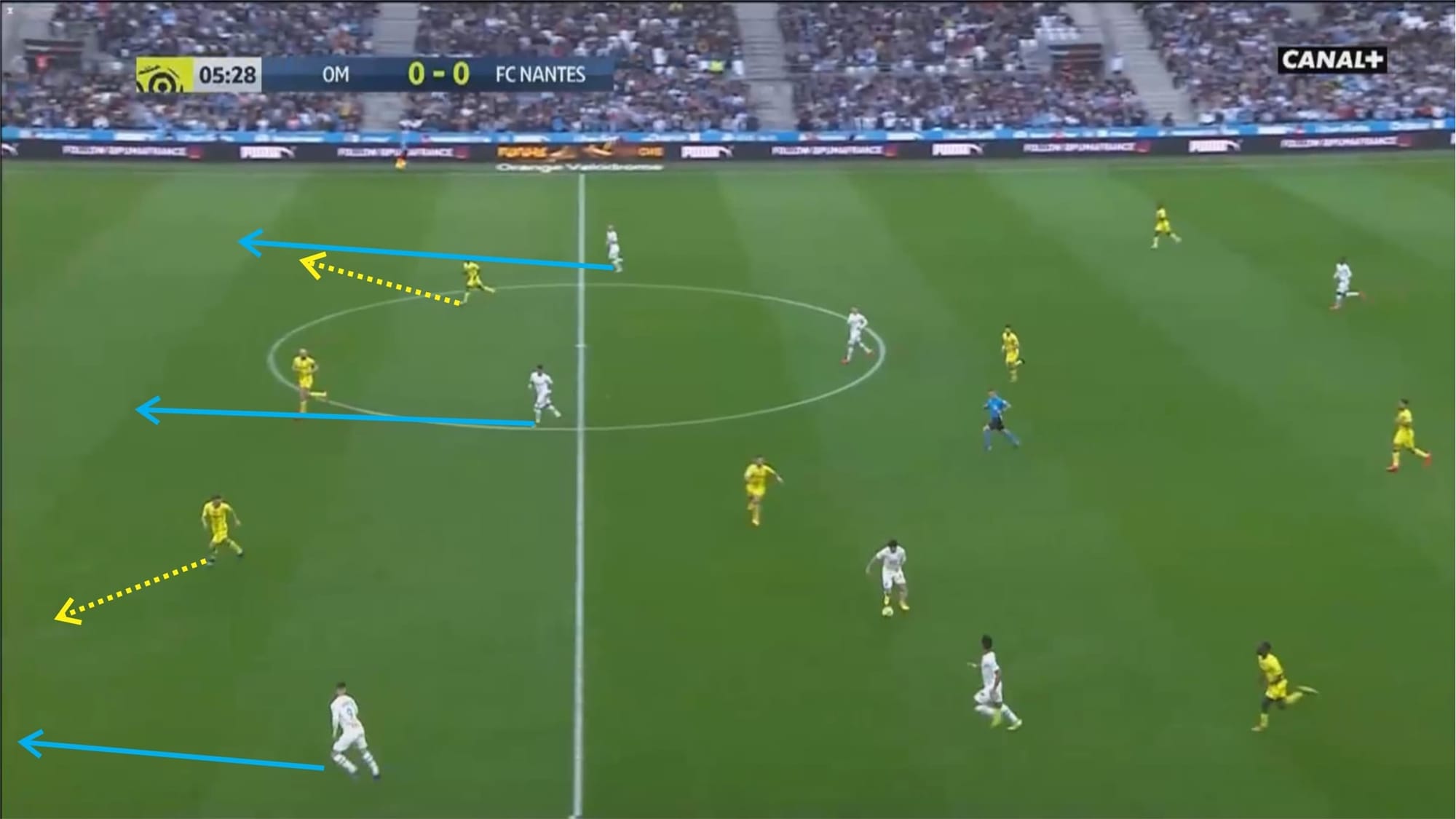

Above you can see Marseille’s structure in the early phase of their build-up. The two full-backs sit high up the pitch but while one sits higher up, the other sits a little bit lower down the pitch thus making the shape look asymmetrical. The full-back usually sits lower if the ball is on his side. In the image above, the ball was moved from the right side (Álvaro González) to the left side (Duje Ćaleta-Car). With the ball being moved from one side to the other, the structure also moved with Amavi (left-back) dropping to receive and Valère Germain (left-winger), Darío Benedetto (striker), and Sarr (right-winger) following by shifting to the right side and then Hiroki Sakai (right-back) would move up.

At certain games, they’d go against a team that look to overload the flank in order to prevent progression on the flanks. In this case, they’d certainly look to switch play often and have their wide players (full-backs or wingers) always sit near the touchline to stretch the defence.

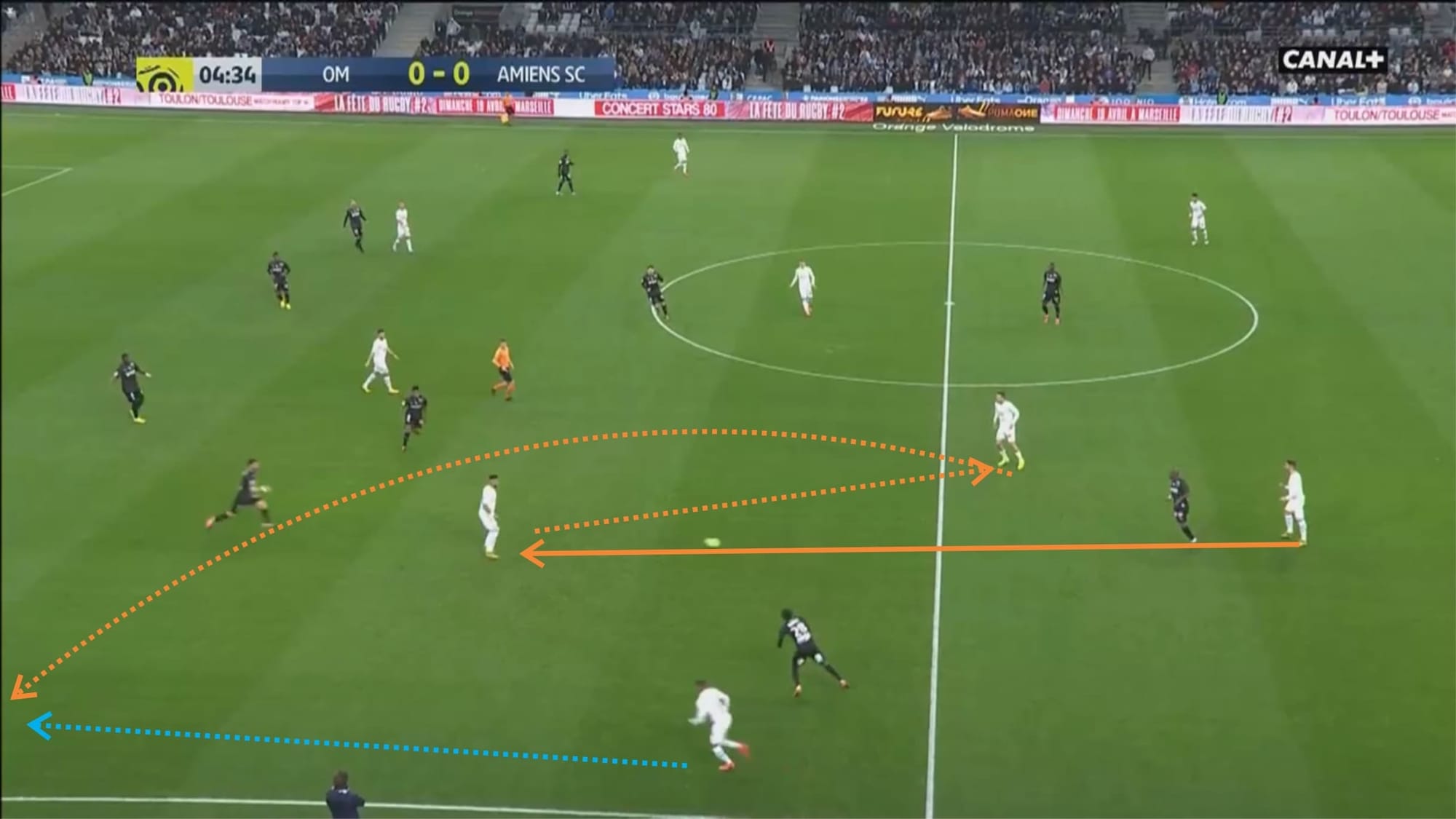

Marseille’s combinations on the flanks are quite simple in the eyes, but they’re quick, straightforward, and effective. Using only one-two touch combinations, wide rotations and third-man mechanisms, Marseille are often able to create imbalances in the opposing team’s defence and disorganise them. Usually, the full-back, winger, and central midfielder are the ones involved in these combinations but at times the winger or central midfielder may swap positions with the striker so the latter can join in and combine on the flank.

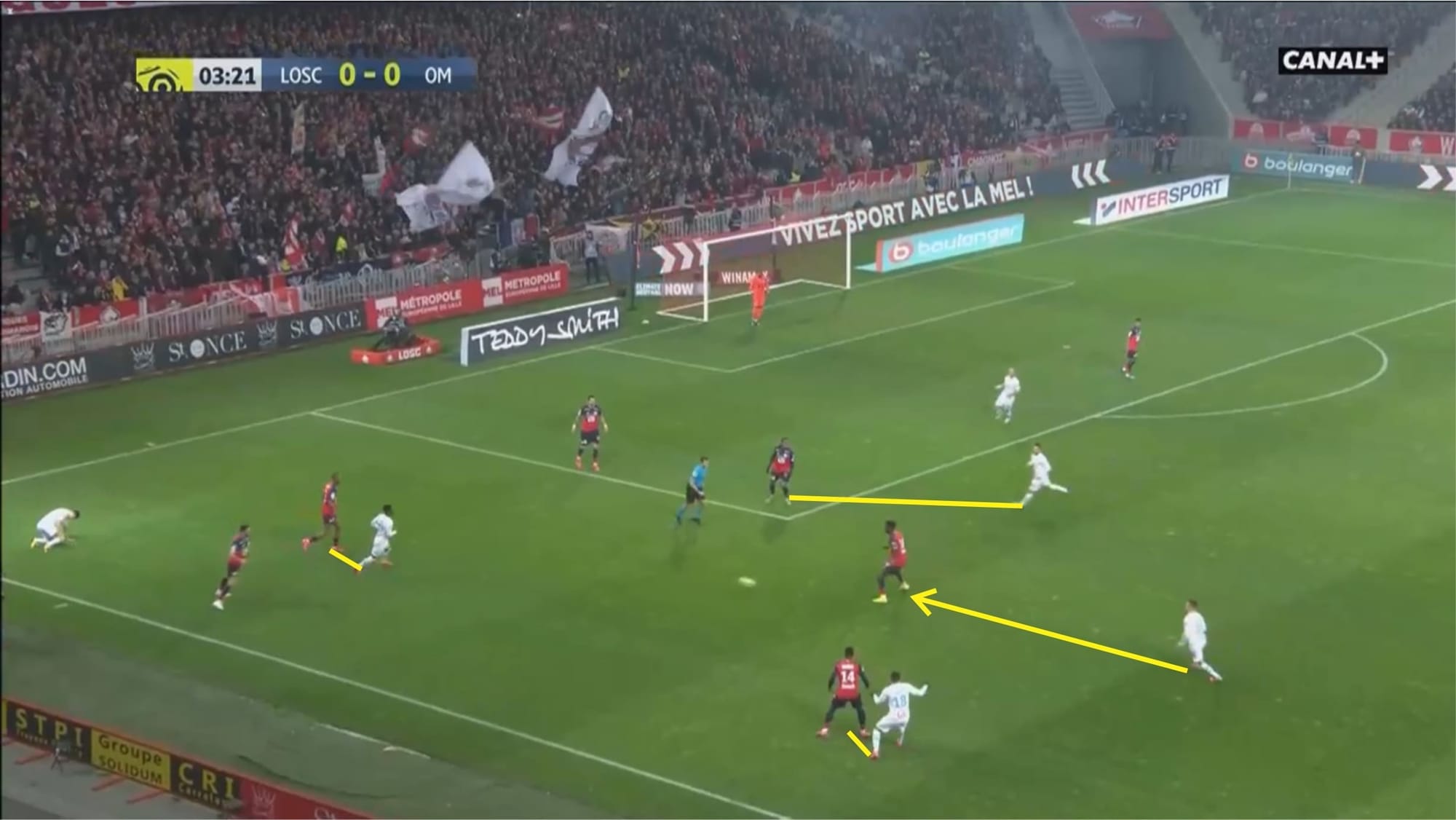

In the picture above, the left-winger dropped to receive, dragging the right-back with him and creating space. The left-sided central midfielder then saw this space and moved to occupy the space. Upon receiving the ball, the winger had the options whether to play the ball to feet or into space.

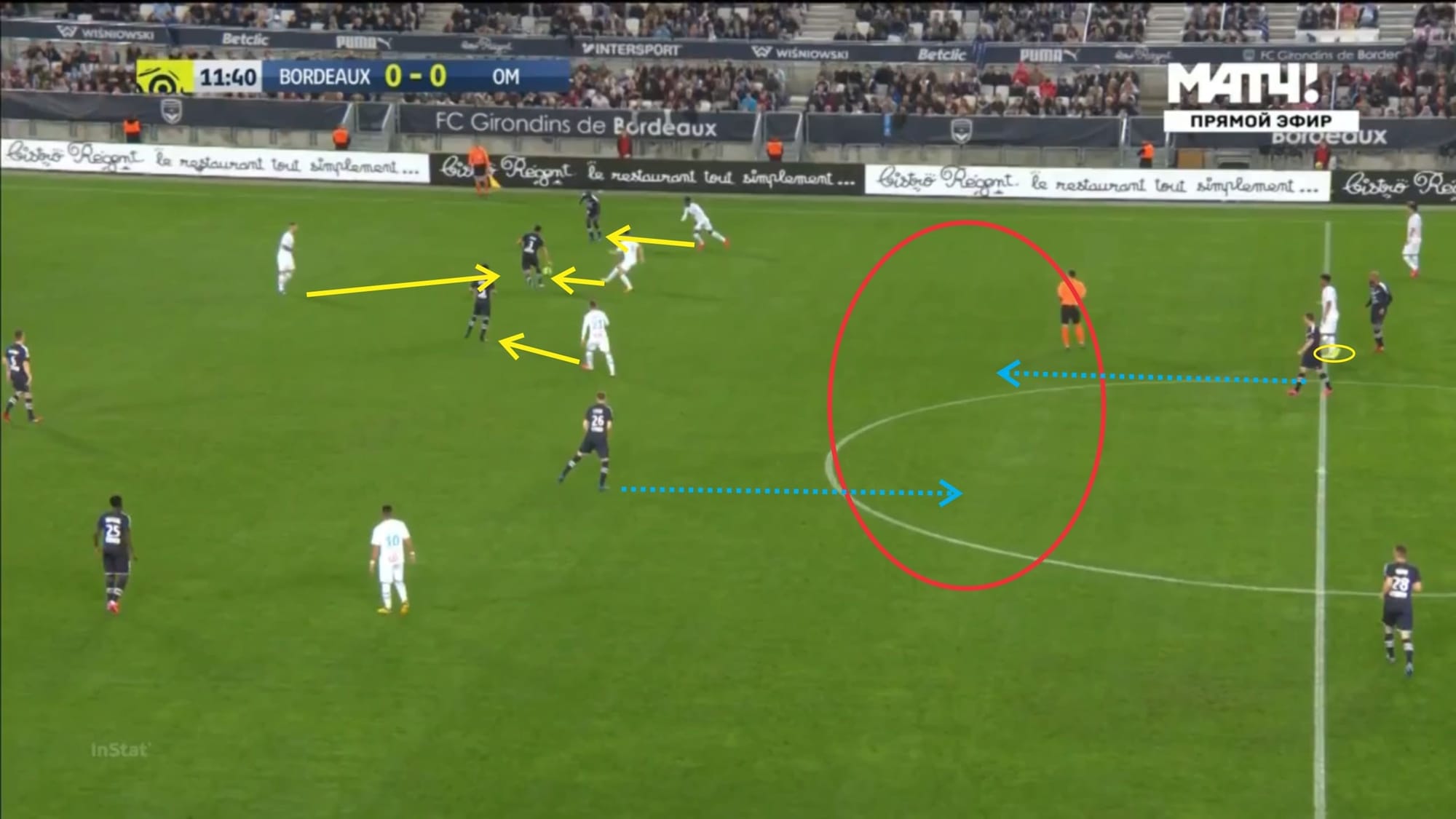

Similar tactics can be seen in the picture above. The left-winger dropped to receive and dragged the opposing right-back out of his position. This triggered the left-back to make a run to exploit that space. The left-sided defensive midfielder (Marseille used a 4-2-3-1 double pivot in this game) delivered a first-time pass onto the path of the advancing left-back after receiving the pass from the left-winger.

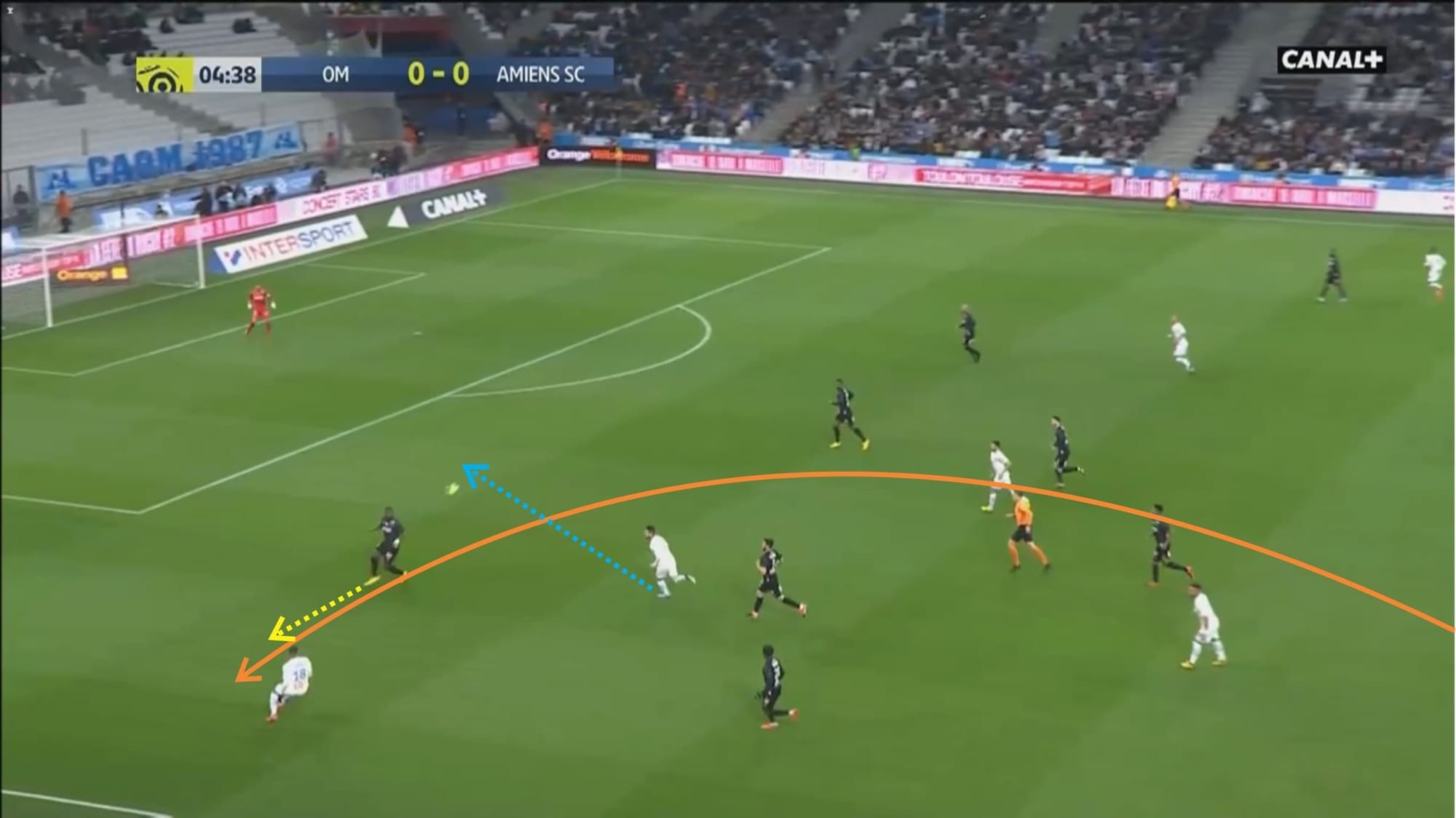

As mentioned before, their third-man mechanisms and active wide rotations are very effective in disrupting the opposing defence and creating imbalances, thus players can often dismark themselves and momentary numerical superiority can often be created in certain areas. The image above is an example. Marseille’s left-back escaped his marker (opposing right-winger) and received the ball in an advanced area on the flank. With the attacking midfielder sitting near the area, this created a 2v1 situation against the opposing right-sided centre-back and with the latter looking to close down the ball carrier, an opening was created and Marseille could craft a goalscoring chance there if the left-back could deliver an accurate pass. However, in this particular situation, the right-sided centre-back managed to anticipate the attack and prevented them from creating a goalscoring chance.

Statistics-wise, Marseille have proven themselves to be effective and clinical in front of goal. They’re the fifth-highest scoring team in Ligue 1 this season with 41 goals scored albeit having only an aggregate of 35.83 xG in total. One might say that Villas-Boas’ side are lucky to outperform their xG this season which may be true to some extent, but their attacking flair, accuracy, and ability to score even from difficult situations should be credited as well.

Defensive approach

Marseille are the sixth on the rankings in terms of goals conceded this season, allowing the ball to get into the net 29 times throughout the season in Ligue 1. Aside from overperforming in attack, they also overperform in defence as they have collected a total of 31.04 xG this season. Aside from the brilliance of veteran goalkeeper Steve Mandanda, the defence in front of him have also been solid and disciplined.

Marseille would form a 4-1-4-1 medium block in defence with a moderate width. However, the shape may also shift into a 4-4-2 in certain situations as can be seen in the image below.

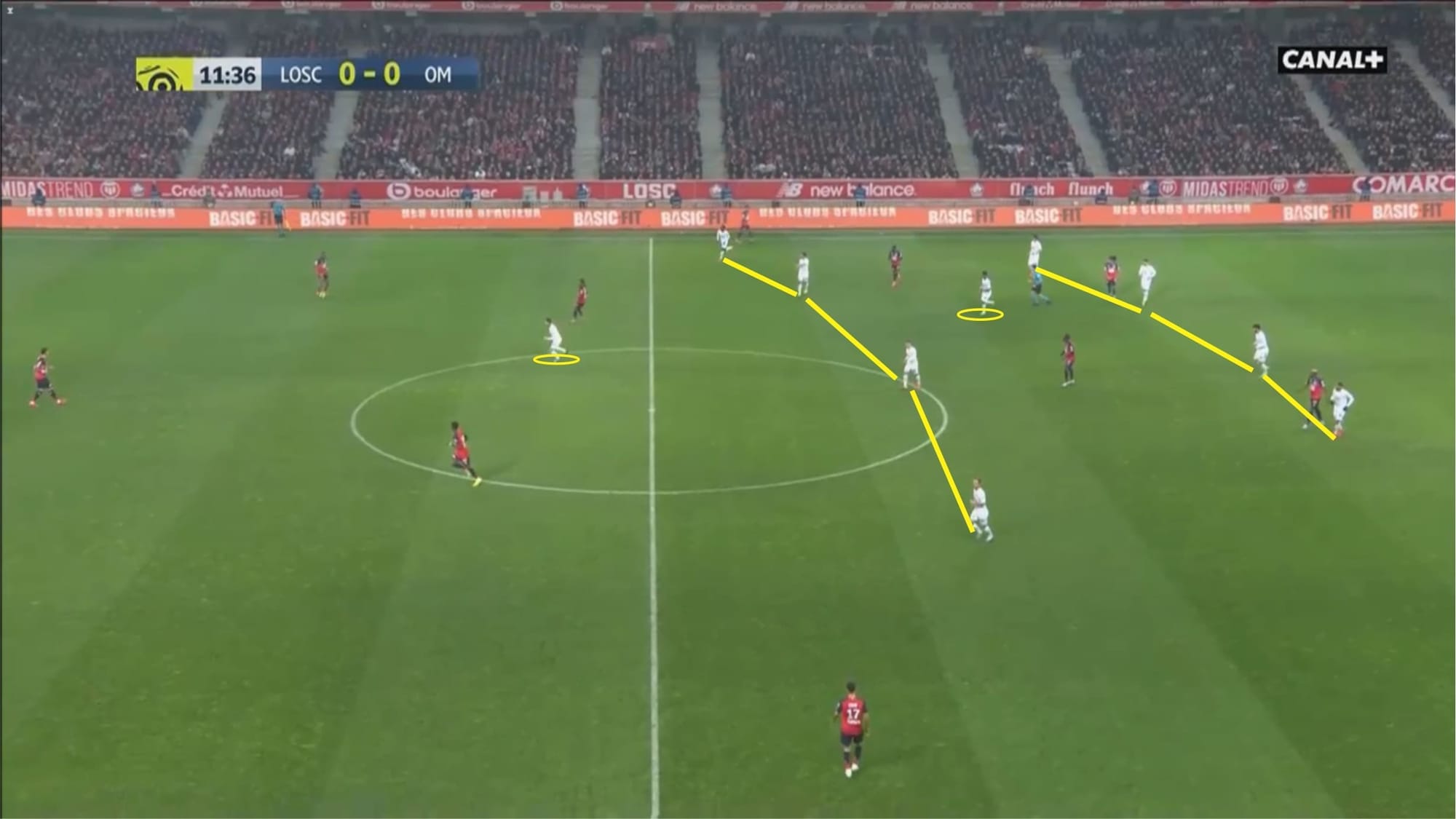

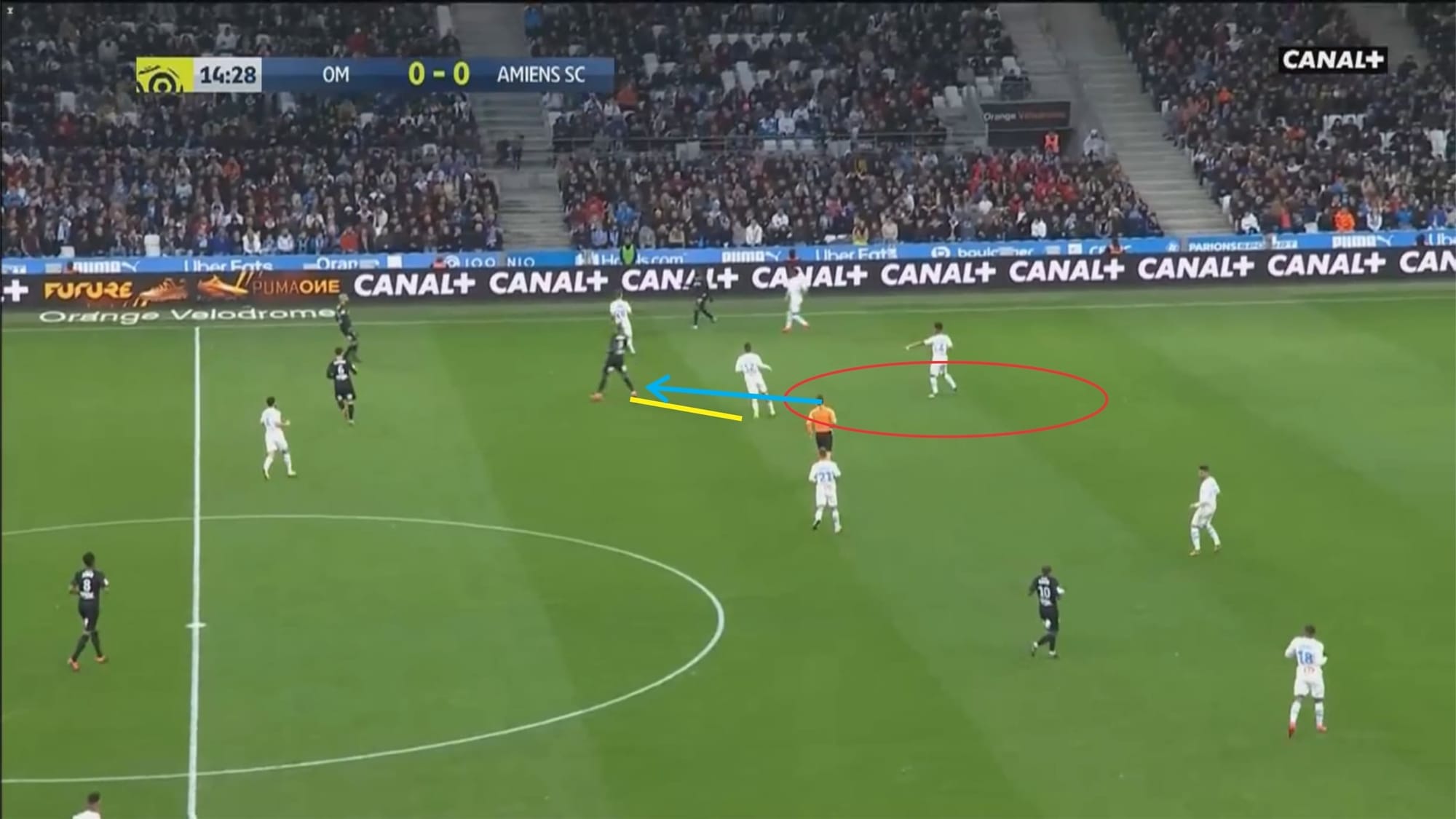

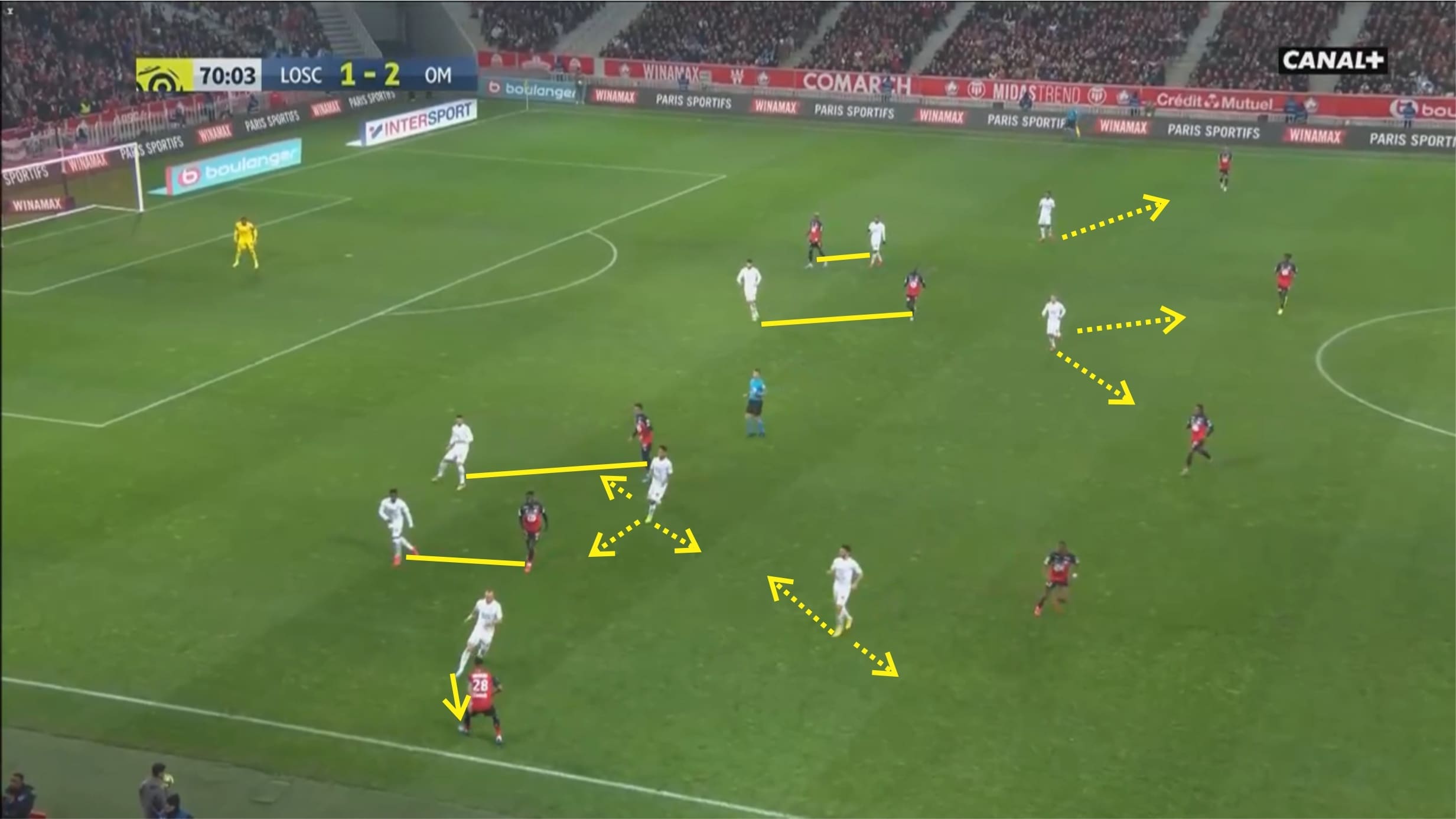

In the image above, you can see that the right-sided central midfielder stepped out to press Lille’s left-sided central midfielder. In that situation, the defensive midfielder moved up and covered the space, preventing a gap to be created.

Marseille press as a unit and though they originally are only moderately aggressive in pressing, if triggered, they’d push forward and pile aggressive pressure inside the opposing half. This is why although they mainly defend with a medium block, we can often see them blocking and pressing high deep in the opposing half. Usually, backpasses, heavy touches, or mistakes/miscommunications will trigger their press and the lines will immediately move forward to pile pressure and maintain compactness.

Marseille use a man-oriented approach in pressing where the closest man would press the ball. Meanwhile, the others mark the nearby options and restrict access to progress the ball or even to escape the pressure. This way they can isolate the ball carrier and potentially win the ball back. However, oftentimes, the defensive midfielder and defensive line are too slow to react to the trigger which means there are times where they don’t push forward in time and this creates a gap between the lines that can potentially be exploited by the opposing team.

Marseille always look to concentrate their player on one side of the pitch to create overloads to isolate and prevent progression as can be seen in the picture above. In the situation above, Marseille managed to outnumber Lille on the flank and with the ball carrier isolated and under pressure, the ball carrier had little time to difficult choices to make and very little time to make up his mind. If the ball was passed back, then Marseille would apply more pressure and they’d be in a very uncomfortable position. If he drove forward, there was a big possibility that the ball could be won by Marseille as they could swarm the ball carrier. In the end, the ball carrier decided to pass the ball through the legs of Germain but failed.

They mainly use a mix of man and zonal coverage in defence. In the picture above, for example, you can see that the back-four were mostly man-oriented while the second line of defence were a bit more passing-lane oriented and mainly cover space.

What’s quite interesting is their space-oriented man-marking approach. This can be seen in the picture below.

Above you can see the right-sided centre-back of Marseille tightly man-marking the opposing striker. The opposing striker was inside the right-sided centre-back’s “defensive zone” and therefore he would be followed around by him.

However, once the opposing striker left the area, the right-sided centre-back didn’t follow him but instead stayed in his area. The opposing striker now entered the “defensive zone” of the right-sided defensive midfielder and it’s his task now to stay close to the opposing striker so he could immediately attack him when the ball was played towards his man. This obviously requires excellent communication and understanding between players as well as great awareness of surroundings.

Transitions

Marseille are particularly quick and dangerous on the break and they adopt a direct approach as well when in an attacking transition.

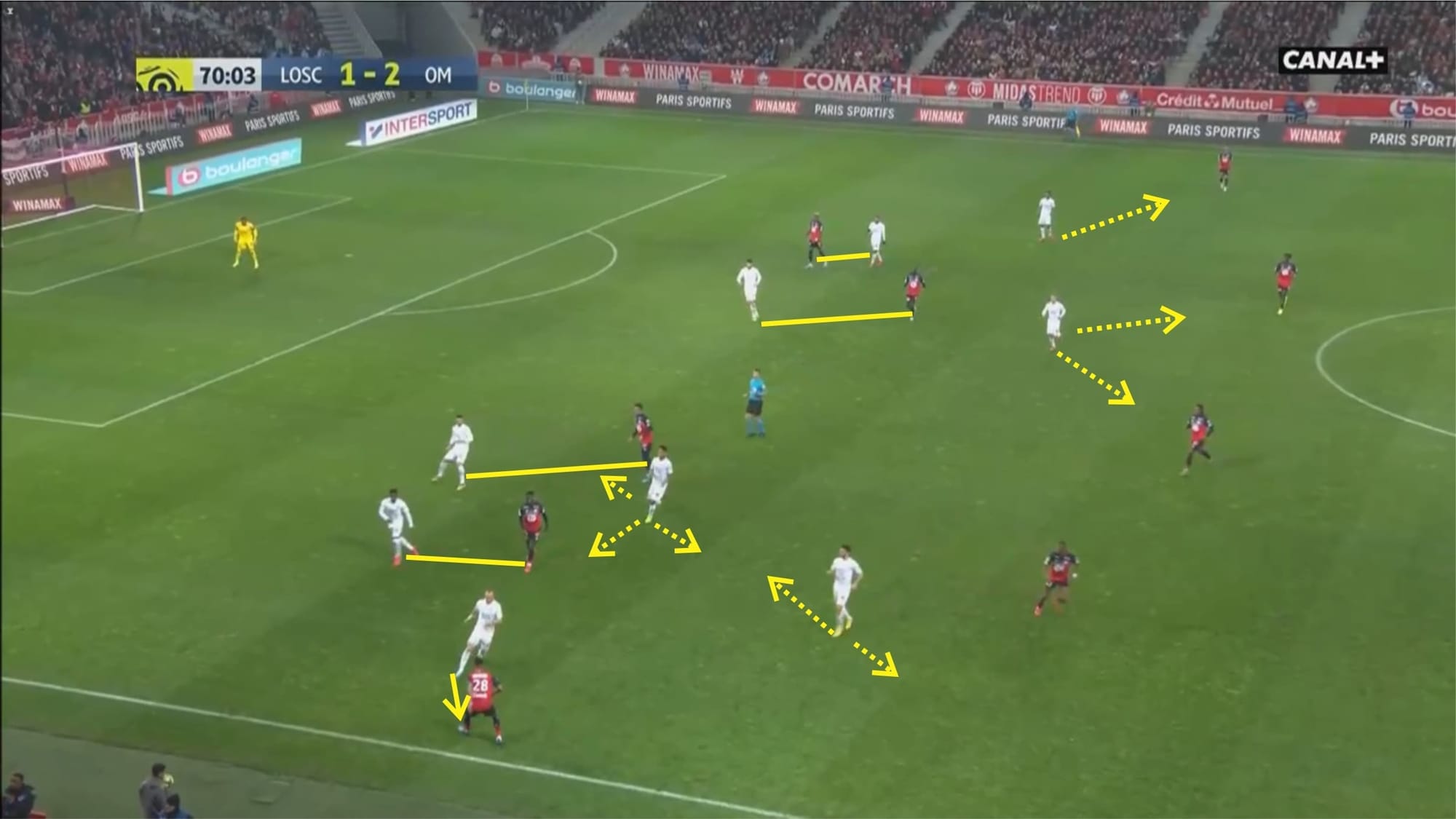

As you can see above, players will quickly get forward whenever the ball is recovered. They have the tendency to use sharp long passes into space rather than dribbling the ball forward and exchanging quick short passes to attack in an attacking transition. Usually, the passes are directed towards space in front of the wingers out wide. Then when received, the winger can choose to take on his marker (in a 1v1 duel) first or immediately take a shot or cross the ball towards his teammate inside the box.

As you can see, the wingers tend to hug the touchline or make an outward run (if they’re in the half-spaces) in order to separate and isolate the defenders to create 1v1 situations.

On the other hand, in a defensive transition, they’d utilise an access-oriented counter-pressing approach. This means that one or two nearest players will press the ball while the others will mark the ball-near options. They don’t seem to be very aggressive when pressing for the ball, but their approach seems effective enough to at least prevent quick counter-attacks from the opposing team. And of course, the pressure can even potentially force the ball carrier into making a mistake which can help them recover the ball deep inside the opposition half.

Conclusion

Under Villas-Boas this season, Marseille have become one of the most difficult team to defeat in Ligue 1 with them recording only four losses so far from 28 games in Ligue 1. With 16 wins and eight draws in their hands, Marseille have collected 56 points, eight points behind the league leaders. So mathematically, it’s still realistic – albeit quite optimistic – for Marseille to overtake PSG and top the table by the end of the season. That is, however, if all things go their way – meaning that PSG would have to drop points too. Certainly not impossible, but difficult to imagine Thomas Tuchel’s side bottling it late in this season.

Comments