I’m a Real Madrid fan. Guilty as charged.

But visiting the hollowed grounds of La Masia has long been a bucket-list item. When I visited Barcelona, the will of the coach and analyst overpowered that of the fan. Taking in the glory of the humble farmhouse was breathtaking, sending memories of players and El Clásicos past racing through my mind.

It’s a visit I’ll never forget.

As a coach with over a decade at the academy ranks, youth development methodology has always fascinated me. It pushed me to look at the way Barcelona trains players. Same for Sporting, Benfica and Porto, as well as Dinamo Zagreb, Ajax, PSV, Fiorentina and Motherwell. It’s a passion that supersedes fandom.

As Johan Cruyff said, “The future of football is in the hands of the youth.” Identifying the clubs with the greatest impact on youth development is the driving interest behind this data analysis.

Our goal today: discover which clubs offer the best developmental pathway for their players.

The flip side is seeing which clubs are perhaps better at identifying and recruiting top young players from their region and in which countries that is more common.

Secondarily, we also want to gain an understanding of clear development trends in the countries represented at the Euro U21s. In which countries are players more likely to stick with their academies and in which do we see more player movement during their teenage years? We want to see which clubs offer the best development for lead players and which are the best recruiters, swooping in later in the process.

Let’s see what the data says.

Process

This data analysis is limited to the nations represented in the Euro U21s. All information from this article was publicly sourced, including the rosters, which are based on the imperfect rosters available prior to the tournament. Some of the players have aged out, progressed to the full national team or even switched allegiances (during writing). That’s okay. We’re looking for general tendencies at the club and national level.

Each player’s youth and early pro careers were documented, tracing as far back as we could reliably source the information. Some nations have greater documentation of player movement than others.

Portugal’s squad was easily the best documented with each player having a full list of clubs dating back to their earliest forays into grassroots football. Meanwhile, Georgia and Israel were more difficult to verify and had less public documentation of career trajectories. Aside from those two nations, we were able to find the years that each player was with a specific club and add them to the spreadsheet.

Each stint at a club was recorded individually, so if a player represented Real Madrid, spent a year at Getafe and then came back to Real Madrid, those two stints at Real Madrid were recorded separately, but with all years associated with the club adding to Real Madrid’s overall developmental contribution.

The last note is that the clubs are determined based on who owns the player’s contract. Chelsea is renowned for a youth academy of top-level players, but they’re equally known for loaning their academy products out for many years. In this study, Chelsea would still be credited with the developmental contribution as the parent club.

For the most part, these loans were carried out as players entered the Performance Phase, officially starting their professional careers. The loan itself is a means of development, typically carried out by a club with a similar game model. As such, the parent club received credit for continuing the player’s developmental trajectory.

Club contribution to youth development of Euro U21 2023 players

As we start this data analysis, the first step is to identify which clubs have the greatest representation in the Euro U21s. Since this age group is comprised largely of players who are just beginning their professional careers, it is important to note that we will see a wide range of nations and clubs contributing players to the tournament.

It’s also important to note that the players in the tournament are some of the best their nations have to offer in the age group, at least generally speaking as national and club politics may play a role in player selection. That said, some of the best U21s may already be full national team players. Jude Bellingham immediately comes to mind; there’s no point in playing with the U21s.

In terms of studying the best U21s in Europe, we must also keep in mind that some players who weren’t selected to represent top teams could easily represent some of the weaker teams in the tournament, potentially even star for those sides. There are more elite U21s in Europe, and even the tournament’s teams than covered here, but this data analysis does give us a framework for evaluating top academies and developmental trends across these 16 nations.

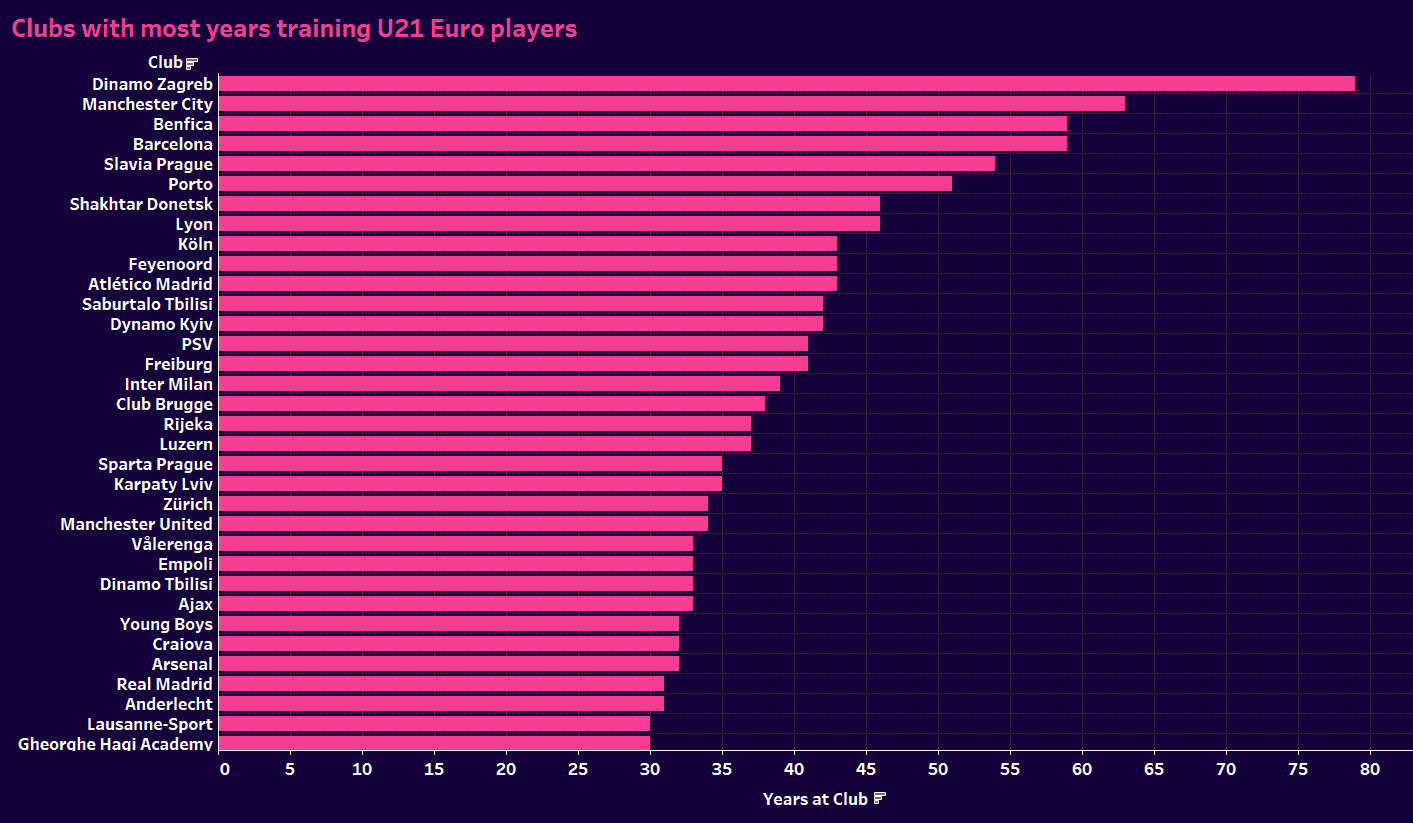

Listing each player, the clubs they represented and the number of years they were with each of these clubs, we built out a database to discover which academies have the greatest contributions to player development at the tournament. In this case, our top five are Dinamo Zagreb, Manchester City, Benfica, Barcelona and Slavia Prague. The Croatian side leads the way with 79 years of player development invested in the player pool. City added 63 years while Benfica and Barcelona came in tied at 59. Those five clubs, as well as Porto with 51 years of training Portugal’s U21s, have separated themselves from the pack.

The first graph gives an overarching view of the number of years clubs have contributed to the development of players heading to the Euro U21s. It’s a view specifically from the club’s perspective. These are the clubs contributing most to the success of the players in their respective countries.

What we don’t see is the number of consecutive years the players remained with each of these clubs. Anyone can pop in and out of an academy or sign with a big club and then spend the entirety of their four-year contract on loan. In those instances, the clubs play a more limited role in player development.

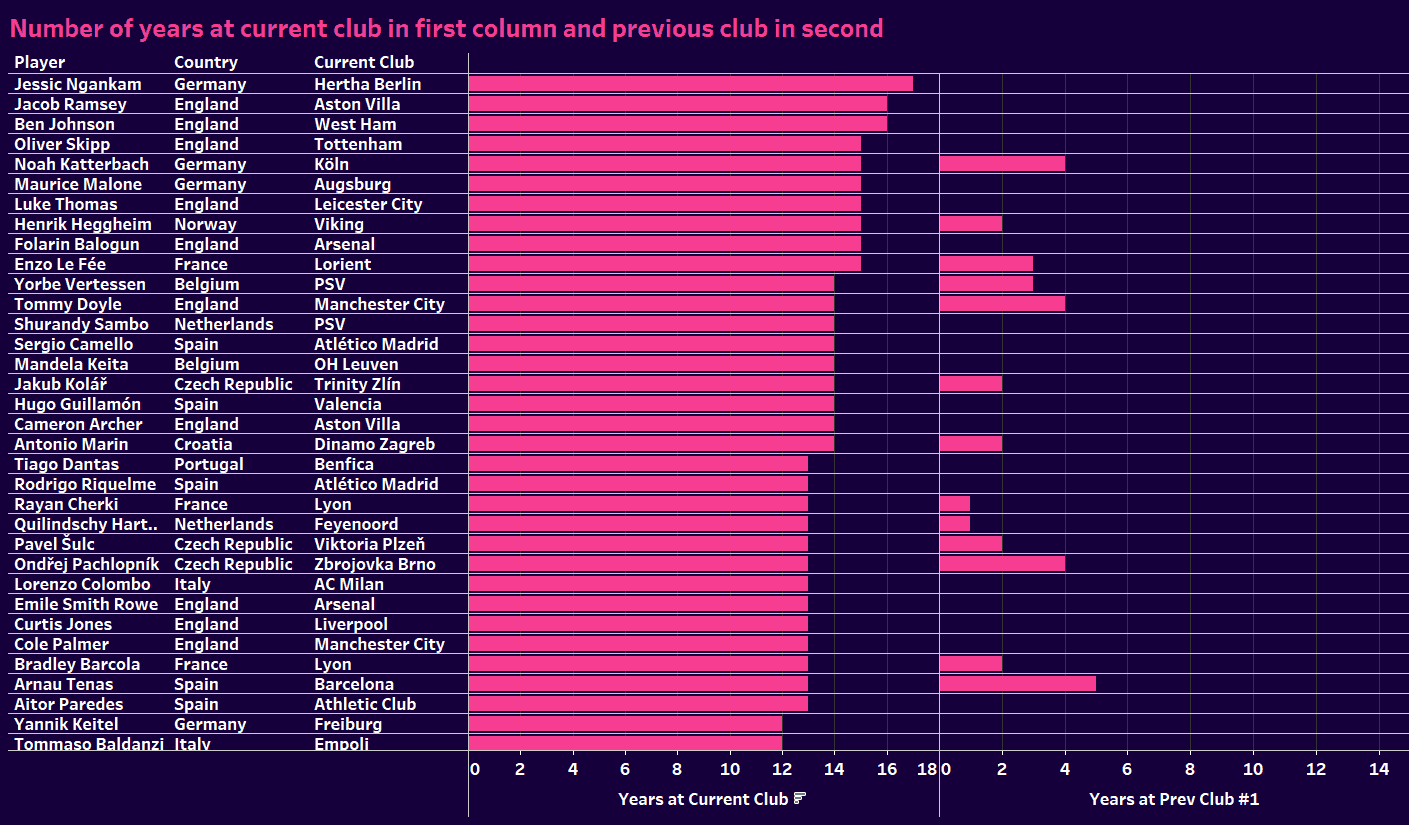

Our second graph takes a different angle. We start with the players and identify not only their current clubs but also how long they have been with each of those institutions. Of the two bars, the one on the left represents the number of years at their current clubs. The one on the right show the number of years at their previous clubs. In many cases, we don’t even see a second club. These players, like Jessic Ngankam of Hertha Berlin, are club lifers. The more frequently a club shows up on this list, the greater the role they have played in that player’s development.

Remember that the U21s are largely starting their careers. Some entered the first team setup as teenagers and are now in their early twenties. For some, they outgrew their current club or sought more frequent minutes, leading to a change in destination.

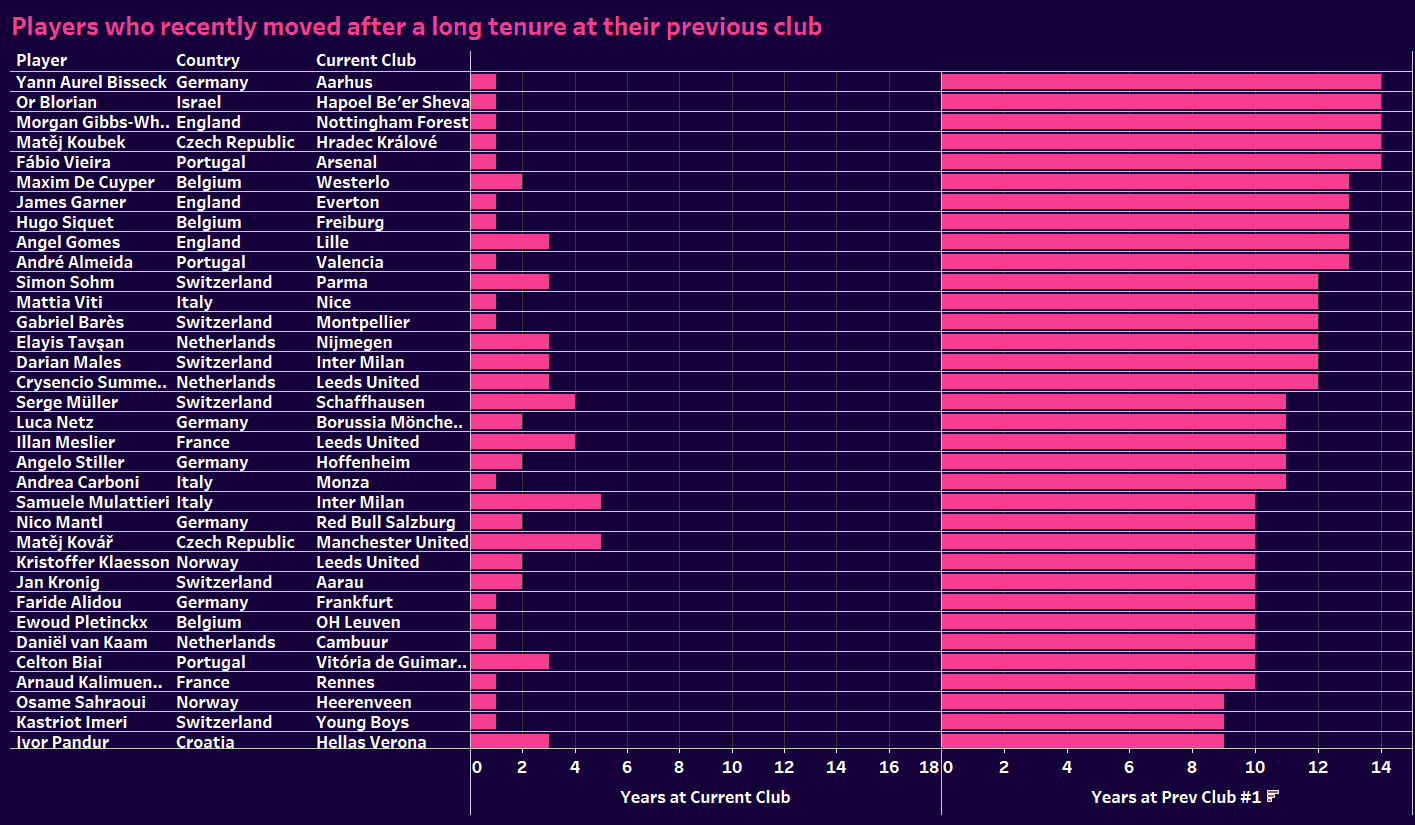

In the next graph, we reverse the priority. Rather than starting with their current clubs, we want to identify the players who have recently changed clubs and give credit to the academies that developed them. The cover player for this data analysis, Fábio Vieira, is the perfect example. Number five on the chart, he earned a transfer to Arsenal in June of 2022. Prior to his move, he had spent 14 years with Porto.

The keys to the section are the number of developmental years clubs provided to the Euro U21 2023 players and the longevity of the players’ tenure. These clubs are certainly recruiting the top players in their region, but they’re also providing the best pathway to a first-division professional career. The clubs that popped up throughout the section can realistically claim that they are among the best developmental hubs in Europe.

How long did the players stay at their academies?

One interesting discovery during this data analysis was that player movement between clubs also had a cultural component. In some countries, like England, club hopping was much less common. Portugal found its place on the other end of the spectrum. The players were much more likely to seek greener pastures. This is a trend we’ll look at in the next couple of sections.

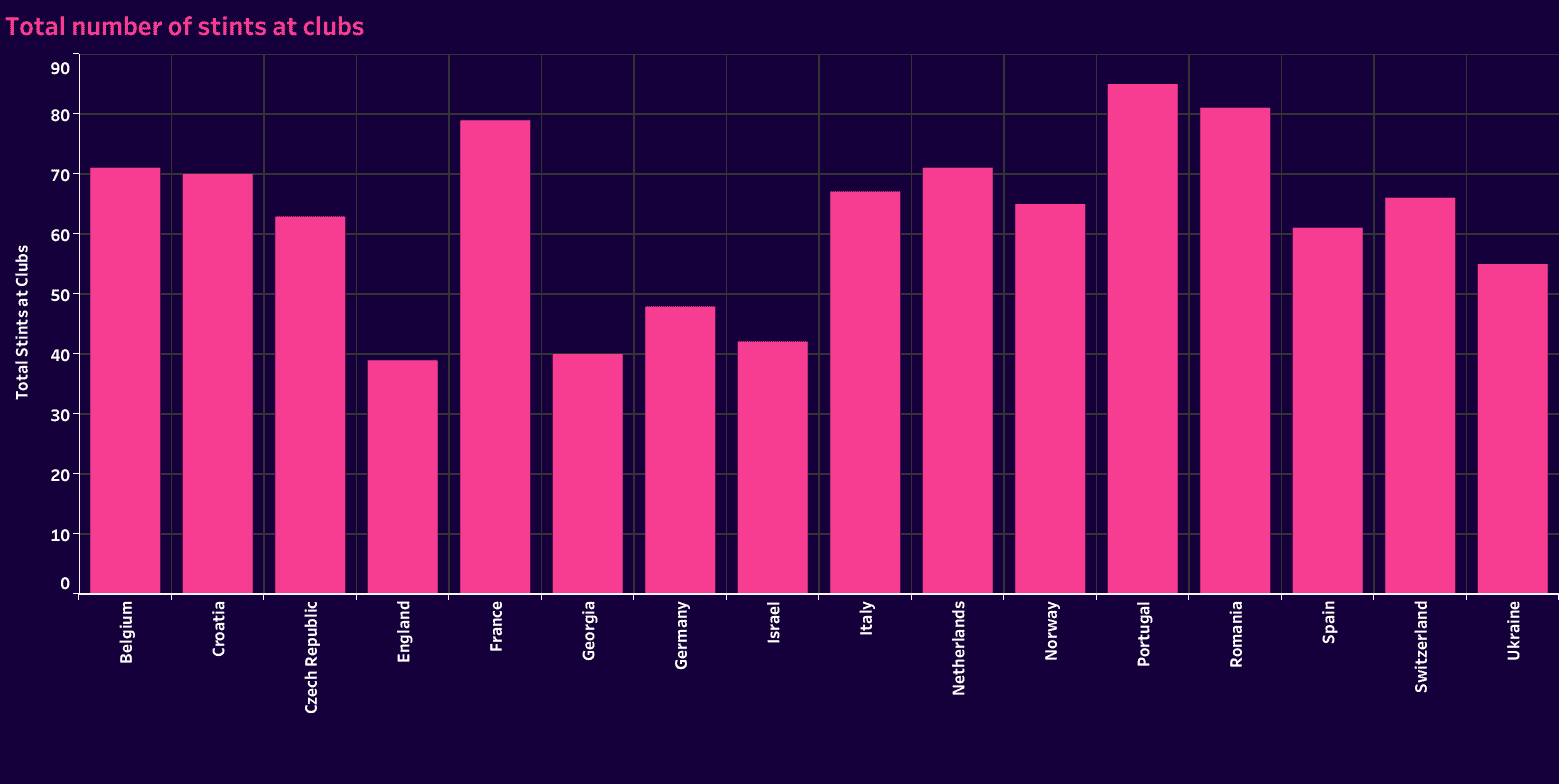

To start, we want to look at the total number of stints players had with clubs across their youth development. For example, Juan Miranda of Spain is in his third season with Real Betis, but he has spent nine with them overall. Years six and seven at Real Betis were separated by a seven-year stay with Barcelona. To put that in developmental terms, he spent ages 13 through 20 with Barcelona, so they’re arguably more responsible for his development than Real Betis.

Let’s take a look at the statistics on the total number of stints at clubs by the players. Portugal had the most player movement with 85 stints at various clubs. England, as mentioned, is at the other end of the scale with just 39 total stints.

One thing to note is that this is where the data on Georgia and Israel is less reliable. We’ve included them since they are represented in the 16-team field, but their lack of publicly available information makes them less reliable. The other 14 countries offered much better documentation. Some of the grassroots clubs gave an end date but not a start, but in most cases, these elite players left their respective grassroots clubs very early on, often before turning 10 years old. The grassroots clubs were merely feeders for clubs with a clear first-team pathway.

Culture also plays a role. In some cultures, players were less likely to join a first-division team’s academy until they were 12 or 13 years old. Their prior clubs still had first teams in lower divisions, but there is certainly a case of players making the jump to a larger academy as they enter the Development Phase.

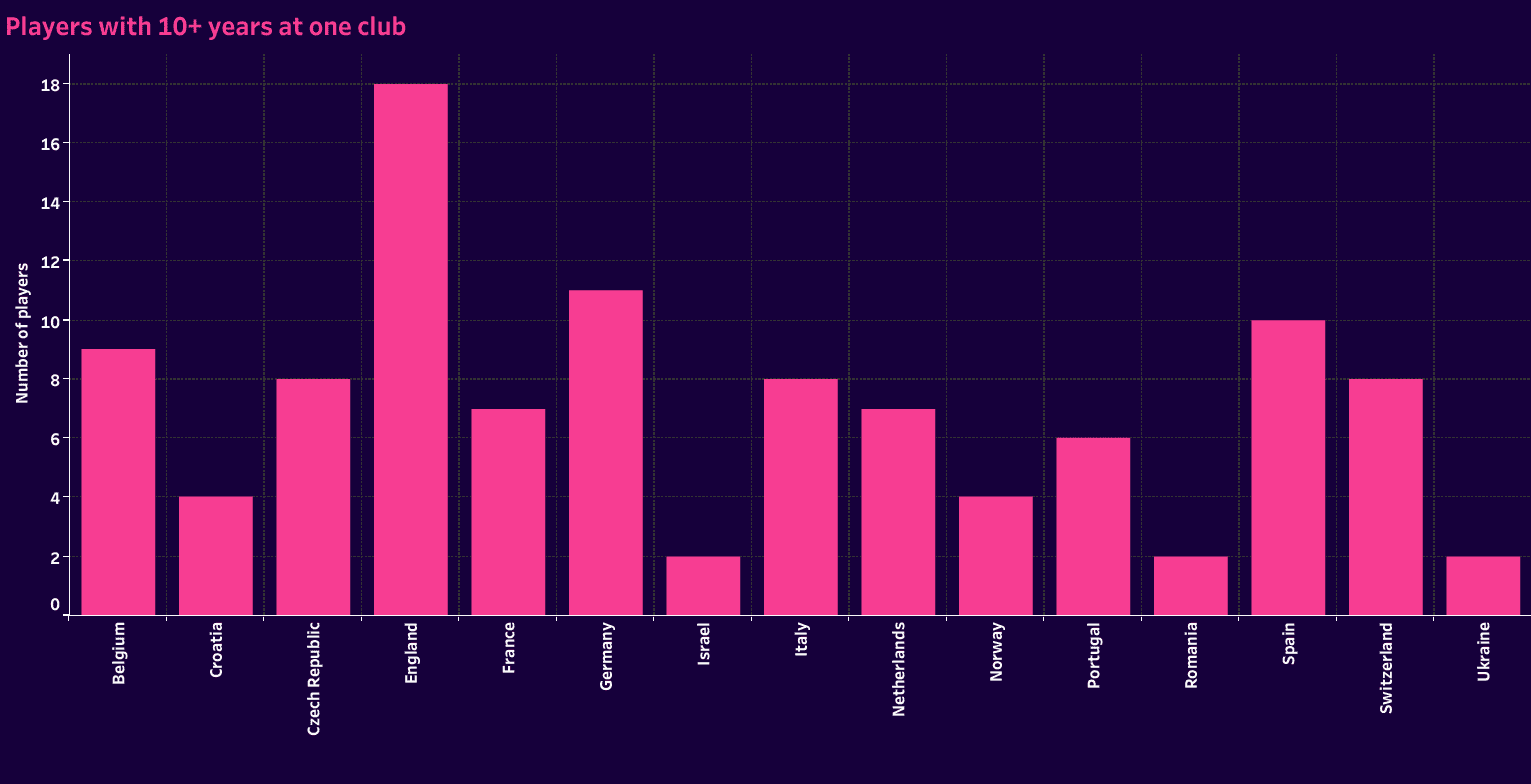

One way to visualize the developmental efficacy of clubs versus a youth academy model with a higher priority on player recruitment is to look at the number of occasions in which players have spent 10+ years at one club. England is the clear winner in the category and in a league of their own with 18. Germany, Spain and Belgium have nine or more players who spent 10 consecutive years with a single club. Czech Republic, Italy and Switzerland were right behind them with eight a piece. This is another good statistic to recognize the stability of the academy experience and the prioritization of player development.

But 10 years is a long time to remain with a single club. In most cases, that means kids were joining a club at roughly 10 years old and have remained with them since. There was a clear shift to more prominent clubs with sustained first-division presences as players hit their early teenage years. At 12 and 13 years old, many of these elite youth players were shifting from smaller academies to one of their country’s major players. That’s especially the case in countries with a smaller geographic area or less professional infrastructure.

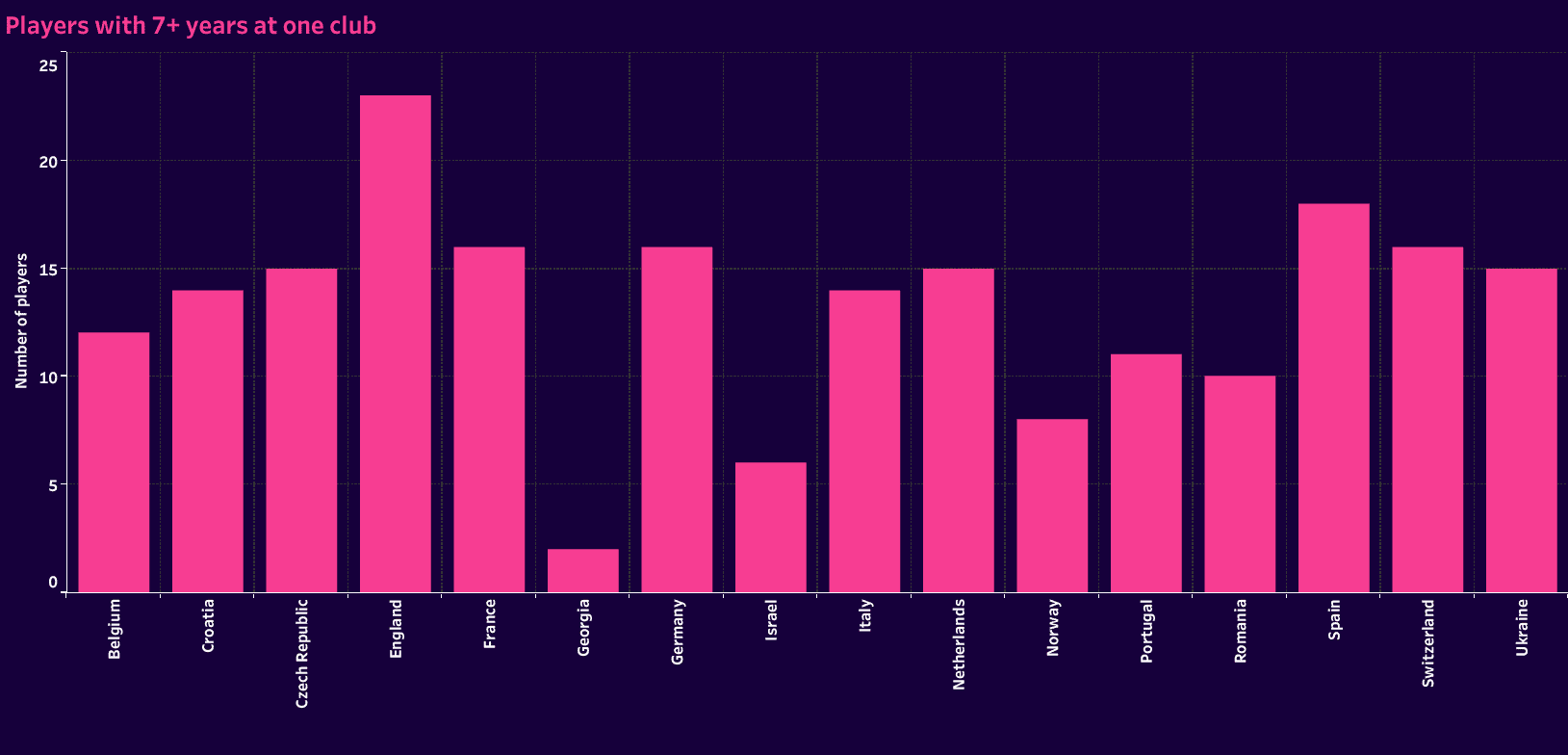

Changing the metrics to seven or more consecutive years at a single club, England is still the clear winner with all but four players achieving that mark. Elsewhere, we do find a dramatic increase for many of the countries involved. Again, look past Georgia and Israel due to the lack of information available, but those other countries give a pretty clear indication of what the Development Phases look like. In most cases, at least half of the U21 national team spent a minimum of seven consecutive years with a single club.

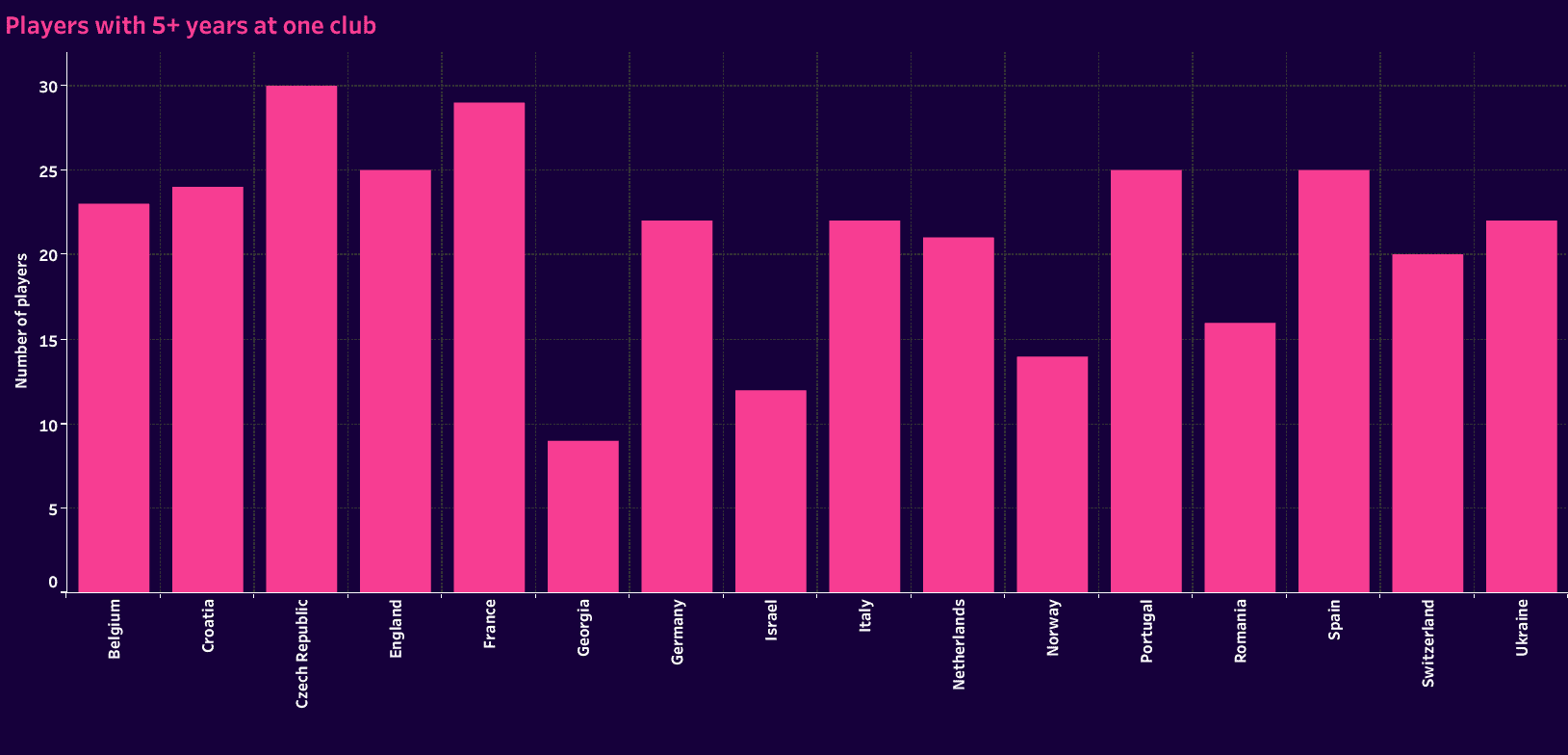

But which countries are more likely to identify players late? Which countries place a greater priority on player recruitment throughout the academy years? One way to tell is a discrepancy between the 7+ and 5+ year graphs.

Five years is still significant in a player’s development, but let’s say we’re talking about a 21-year-old — if he’s been with his current club for five years, that means he joined them at 16. At that point, especially with players of this calibre, it’s more a case of recruiting a player who has shown promise entering the Performance Phase. This is especially a case on the men’s side as players are hitting their final significant growth spurts. By 15 to 17 years old, we have a much better idea of the physical traits the players will possess.

Remember that a player can have multiple five-year stints with clubs. Two was very common. There are cases in which players bounce around between top academies within their city or region. This could be a case of getting cut from one team or squabbling with the coaching staff leading to the exit. It could also be a case of joining a lesser team to get more playing time but with a greater sense of responsibility and importance within the team.

Regardless, we do find that in some countries, the best players tend to stay at their academies, especially once they have earned a spot within a first-division club’s academy setup. In others, players are more likely to change clubs every few years, be it moving up the ladder or taking a slight step back.

In certain countries, like Croatia and Portugal, if you can get in with Dinamo Zagreb or Benfica, you take the offer and stay as long as you can. Any move prior to that roster spot is often positioning oneself within the academy pipeline. We will make no assumptions as to whether the cultural tendencies are club or player-led, but simply that each of the countries represented at the Euro U21 2023 has these tendencies at the academy level.

Player movement by country

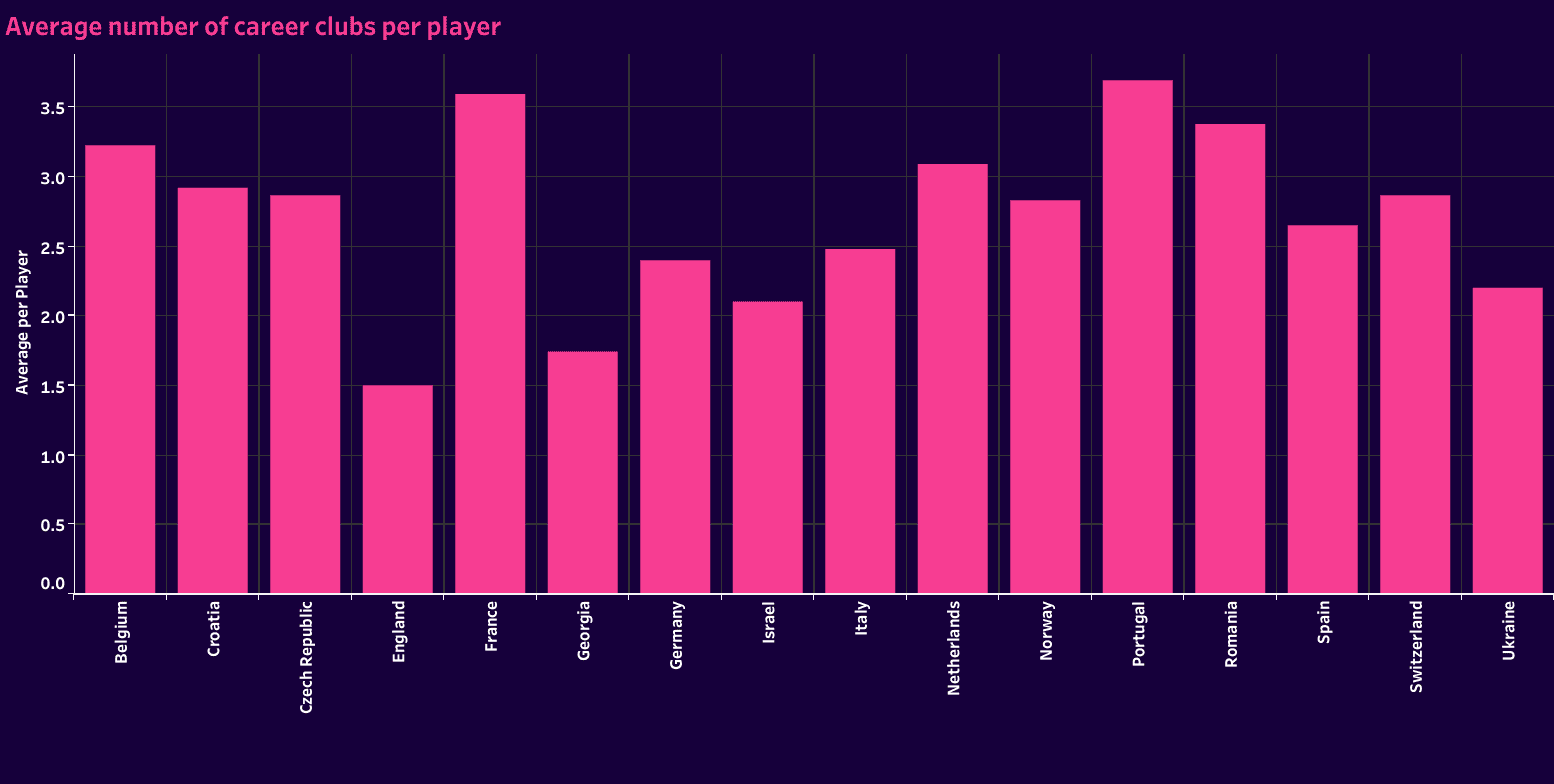

Let’s flesh out that last idea, that in some countries, players are more likely to have shorter stints with academies. Rather than looking at longevity, let’s look at the average number of clubs a player represented and the brevity of his stay.

This is the anti-football variation of our study. We’re looking specifically for the countries that focus more on player recruitment than bringing a 10-year-old through the ranks and into the first team.

Starting with the total number of clubs players have represented, we do find that Portugal and France lead the way. Portugal is perhaps the most interesting case study. Within the player pool, two players have only represented one club, six have played for two and three signed with three. That’s close to half the squad, which shows a good level of stability at the respective clubs. However, the country also has two players with six clubs, one with seven and the eight of goalkeeper Gonçalo Tabuaço. Those numbers give us some perspective on how four or five players can skew the statistics.

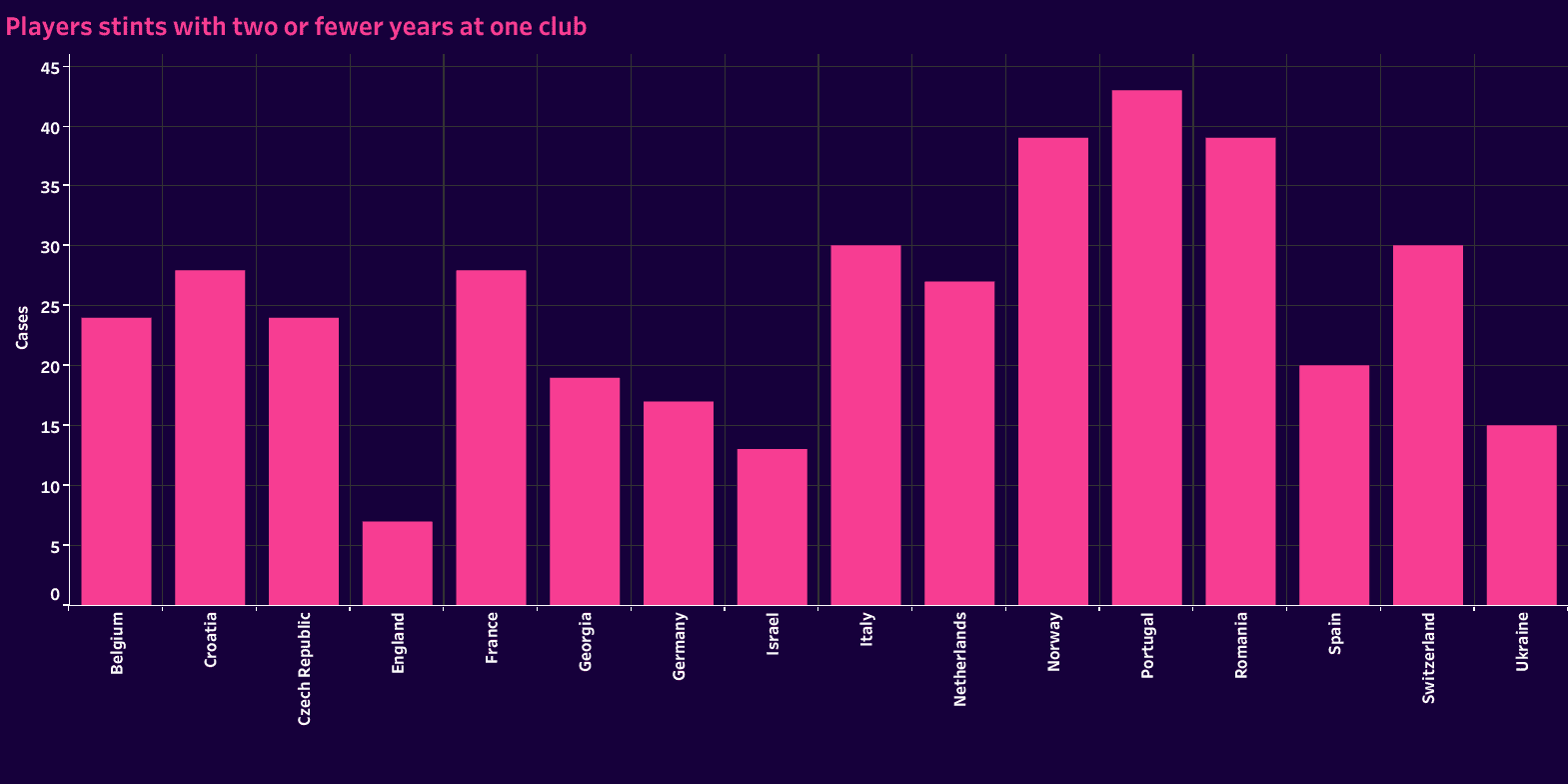

Even though the Portugal example shows us how a minority of players can greatly influence the data, we can push this analysis even further by looking at the number of occasions in which a player’s time at a club consisted of two or fewer years. Again, keep in mind that one player can have multiple appearances in this metric. Tabuaço himself accounts for eight of Portugal’s analysis-leading 43 cases. He was a club hopper, but certainly not the only one.

This tendency to change clubs was also common in Norway and Romania, followed to a lesser degree by Italy and Switzerland.

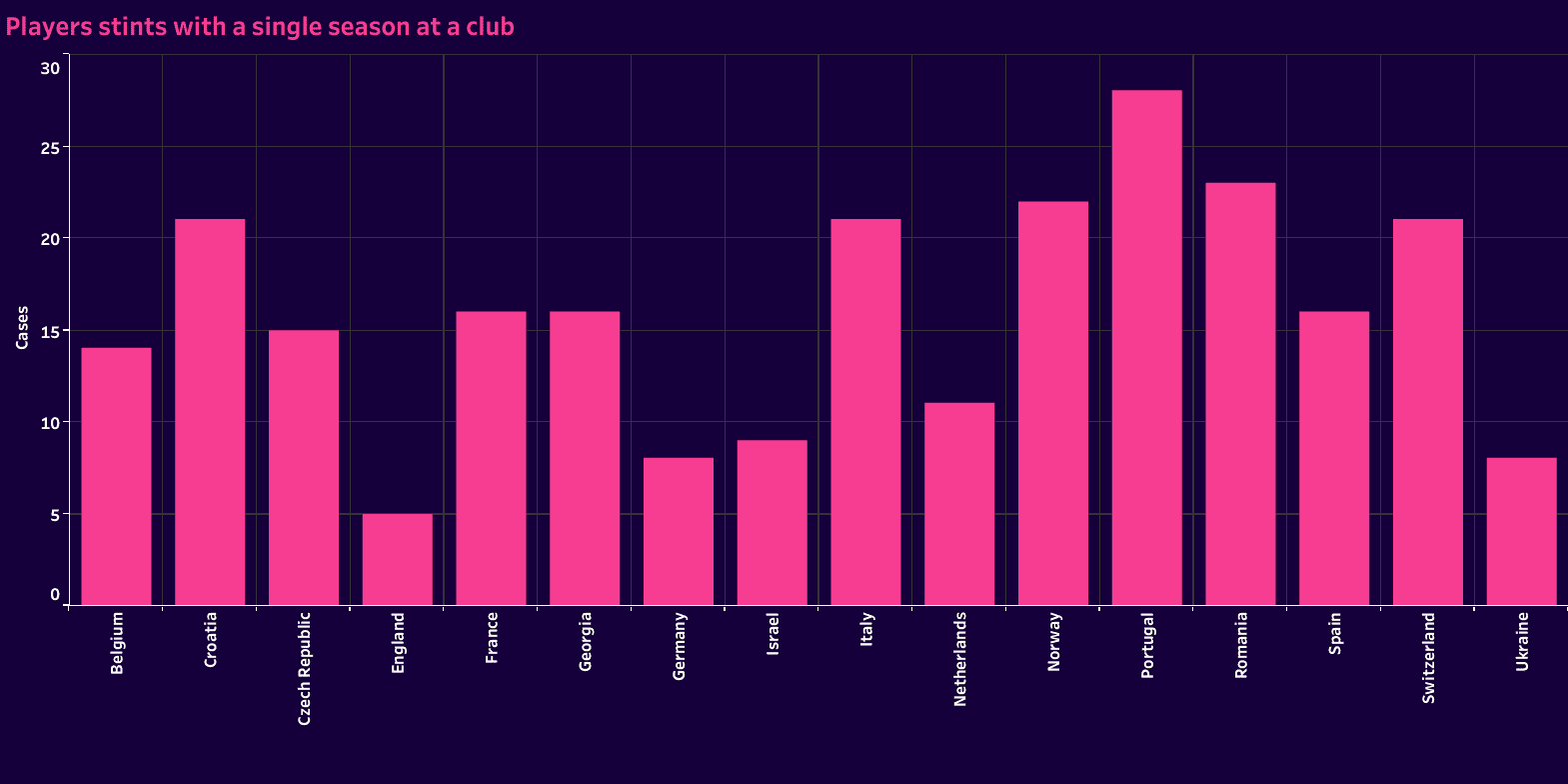

Pushing the negative number even further, our final image highlights the number of one-year stints that the players in each of the represented nations have had during their young careers and academy days. Once again, Portugal leads the way while England sits at the other end of the scale. Germany and Ukraine also perform well in this area.

Again, we won’t make assumptions as to why there’s greater movement within some countries than others. There are so many factors to consider and each decision has its own reasons which are generally unknown to the public. The one claim we’ll make is that if a player made it to one of the biggest clubs in their country, they tended to stay for as long as possible, fighting for a first-team role.

Conclusion

There are so many directions we could take with the info gained through this data analysis. We could look at the percentage of players in the academies of first-division teams that go on to achieve a first-division career. We could also look at how many professionals, across all divisions, these academies turn out. We could also look specifically at the academy trajectories of world-class players compared to those of journeymen veterans. So many angles, and so little time.

At the very least, this analysis has given us a data-driven look at academy trends within the countries represented at the Euros U21. We’ve also seen which clubs are more likely to produce top-level players. Certainly some surprising names, such as the impressive numbers of Köln and Freiburg, the dominance of Dinamo Zagreb and the under-the-radar quality of Manchester City.

For now, we’ll sign off with a greater understanding of the clubs that are best at developing elite players and intuit the clubs that are perhaps better at recruiting players to their academies.

We’ll end with the wisdom of Liverpool’s Pep Ljinders: “Academies should not be afraid to take risks. They should give young players opportunities to play and develop. This is the best way to identify and develop future talent.”

This summer, we’ll get to enjoy the fruits of academies and farmhouses across Europe.

Comments