The competition in the Premier League is intensifying.

After seven rounds, Arsenal

are in third place with 17 points, tied with the defending champions Manchester Cityand trailing the current league leaders, Liverpool, by a single point.

The indicators are pretty promising for the Gunners, as they possess the third-strongest attack in the league, having scored 15 goals, trailing only Manchester City and Chelsea, who have scored 17 and 16 goals, respectively.

In terms of defensive performance, Mikel Arteta’s side boasts the second-strongest defence, having conceded only six goals.

This places them behind Liverpool, who have conceded only two goals.

There is nothing new to mention at the level of set pieces, as Arsenal are currently the team with the highest expected goals (xG) from set pieces in the Premier League, with a value of 3.57.

Analysts have rushed to study and analyse the reasons behind this distinction and its persistence despite opponents’ awareness of Mikel Arteta’s style of play.

However, when you think you are sufficiently impressed by the work of Arsenal set-piece coach Nicolas Jover, you realise that there is still greater potential for astonishment.

The aspect we will discuss is somewhat different from what analysts typically mention, yet it is of utmost importance.

This aspect is their defensive strength during corner kick attacks.

Yes, you read that correctly.

Defending during an attack has become one of the most critical elements in football, known as “rest defence.”

Regarding set-pieces, Arsenal not only focus on creating danger for the opponent’s goal but also ensure they are defensively secure during those attacks.

They can win the second ball and stifle counterattacks at their source while maintaining intense pressure on the opponent.

This allows them to regain possession and initiate new high-intensity offensive waves.

Even if the opponent succeeds in clearing the ball, which is rare, they remain secure at the back.

In this tactical analysis, we will discuss Mikel Arteta’s tactics to remain secure against counterattacks while executing attacks on the opponent’s goal.

Additionally, they can regain possession to threaten the opponent’s goal once again.

Targeting The Far Post With Floated In-swingers & Framing The Goal

We should first mention that Arsenal use in-swinging crosses to target only the six-yard, near or far post, without targeting any other zone.

This is what makes them so effective and harmful.

They keep the ball flying toward the opponent’s goal, not towards the pitch, as in the out-swinging crosses and other zones.

This extreme focus, supported by many strategies and principles, often yields outcomes that typically include threats to the opponent’s goal, goal kicks, additional corner kicks, or miraculous touches from the opponent’s goalkeeper or defender to clear the ball.

It is rare for the opposing team to gain control of the ball to clear it away effectively.

We will start by discussing how Arsenal, under Mikel Arteta’s coaching, don’t even allow opportunities to rebound the ball.

Before we do that, though, let’s quickly recap their attacking strategies from another perspective as they relate to “rest defence”.

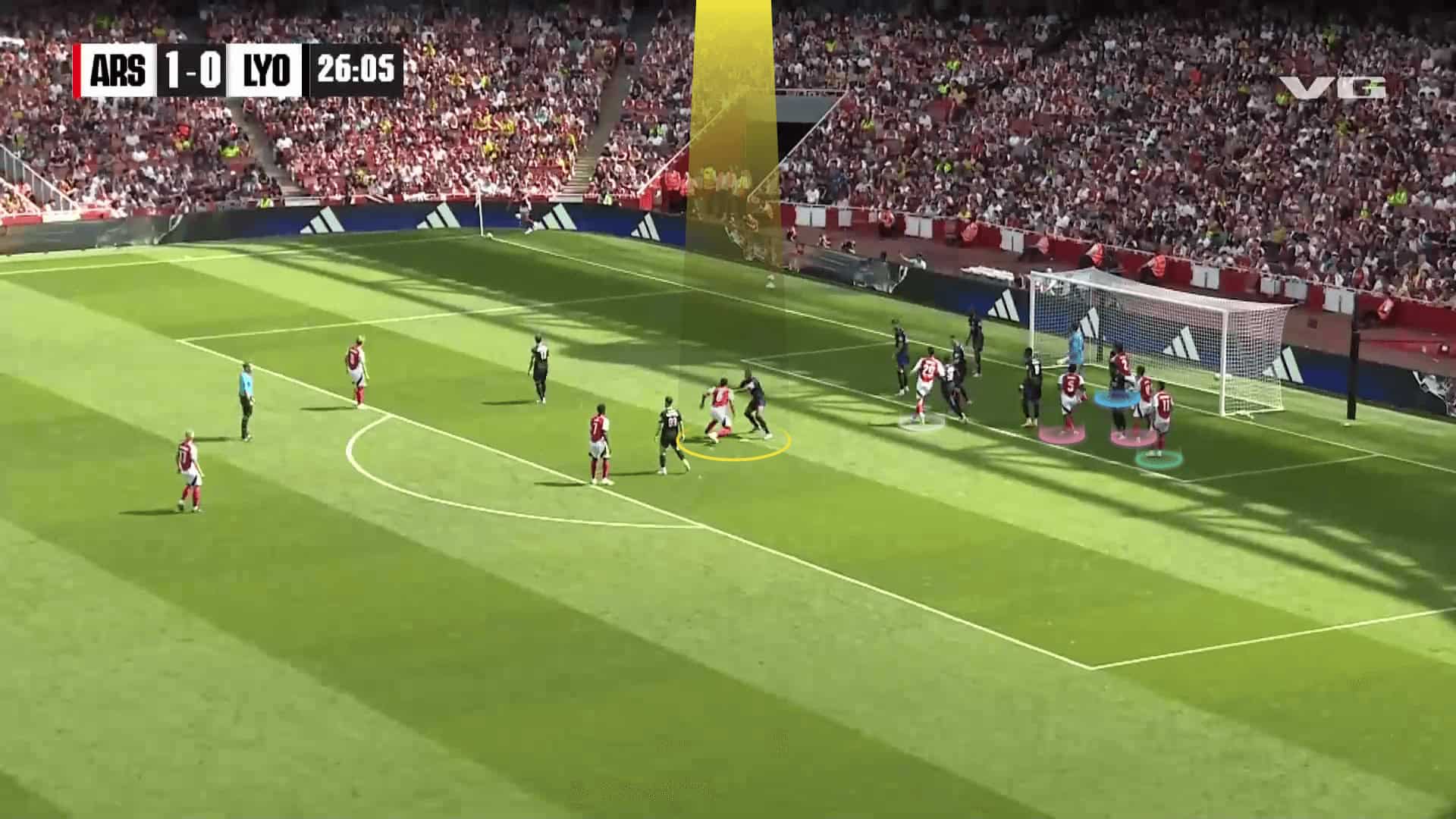

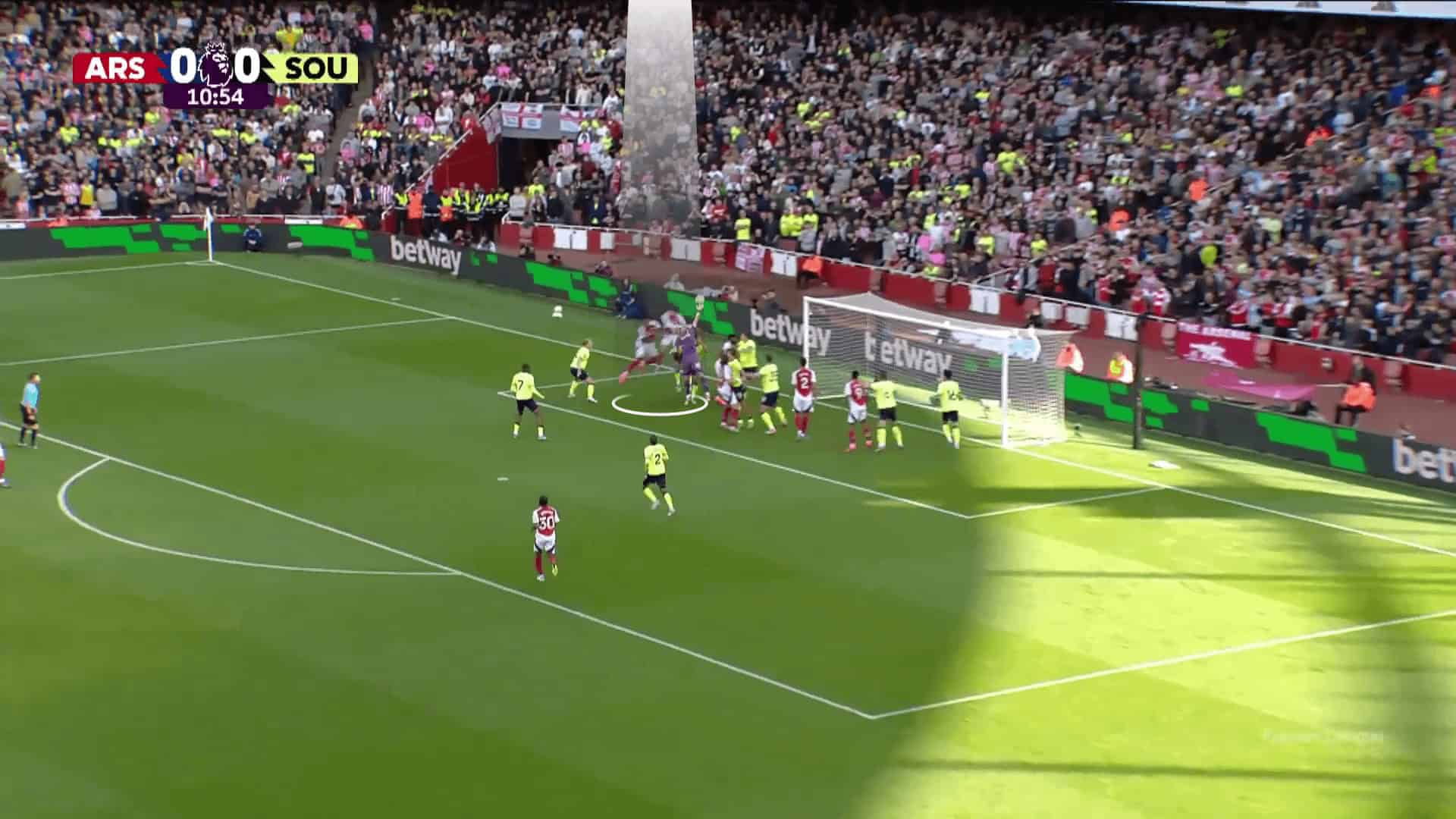

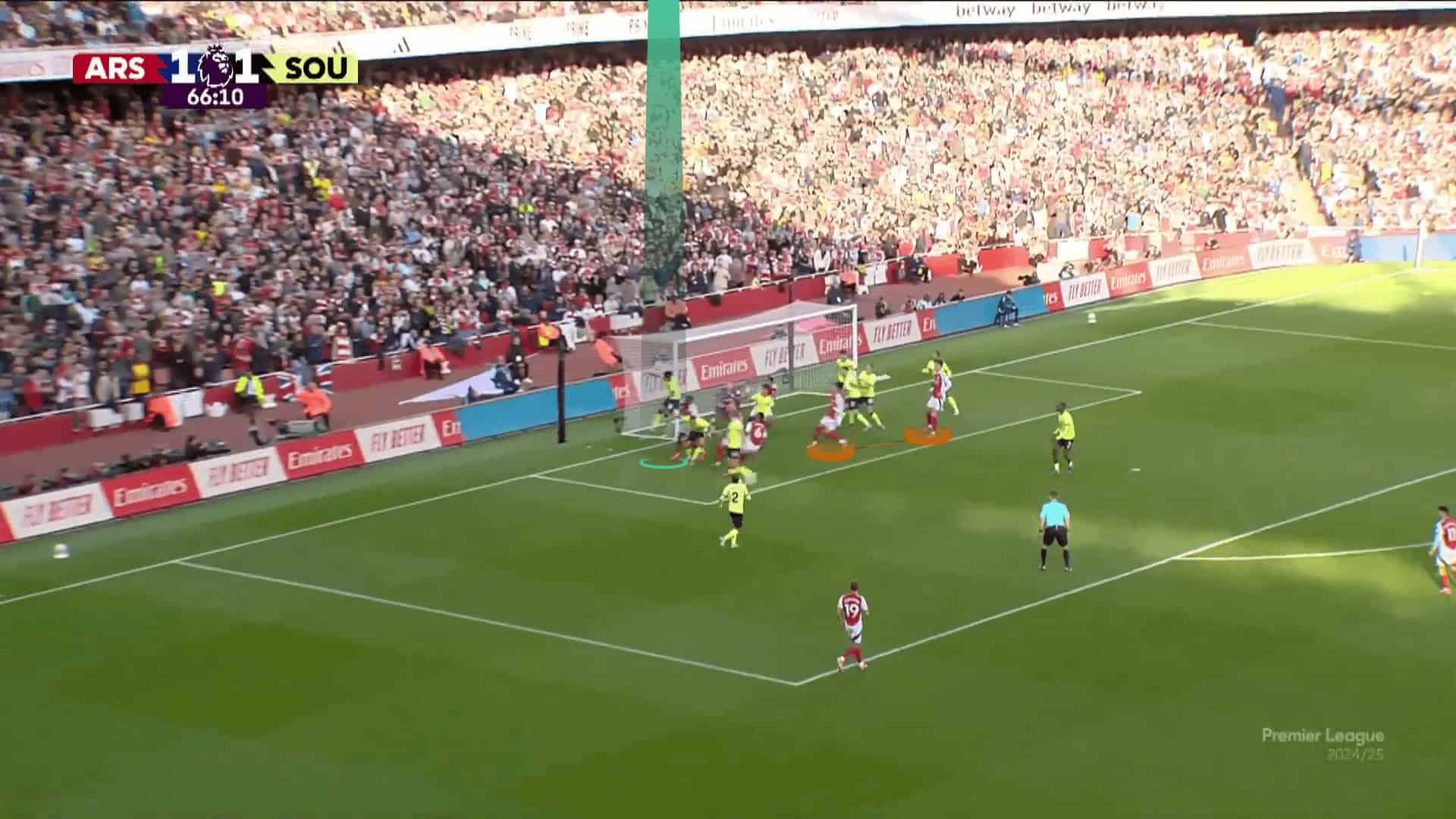

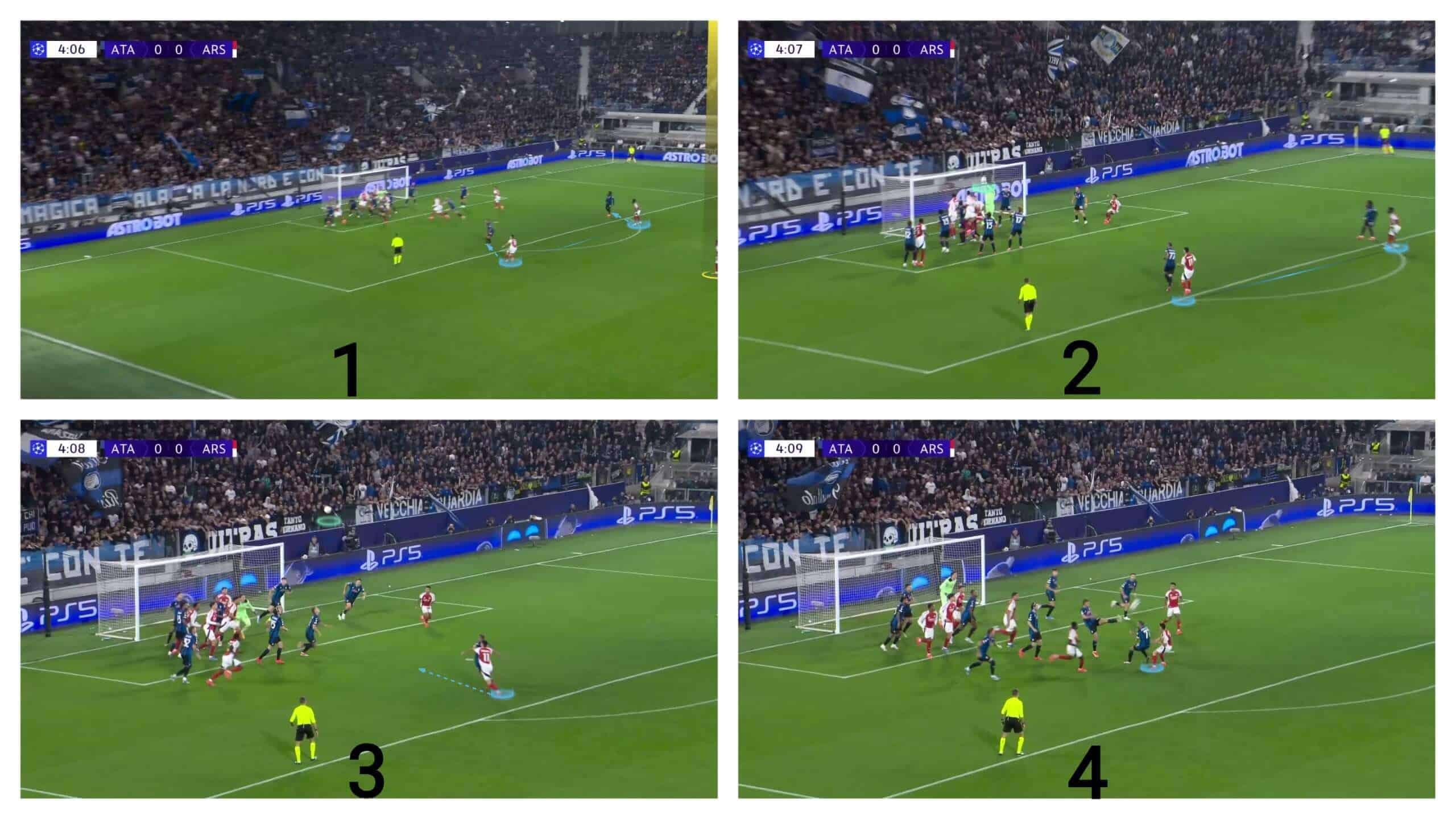

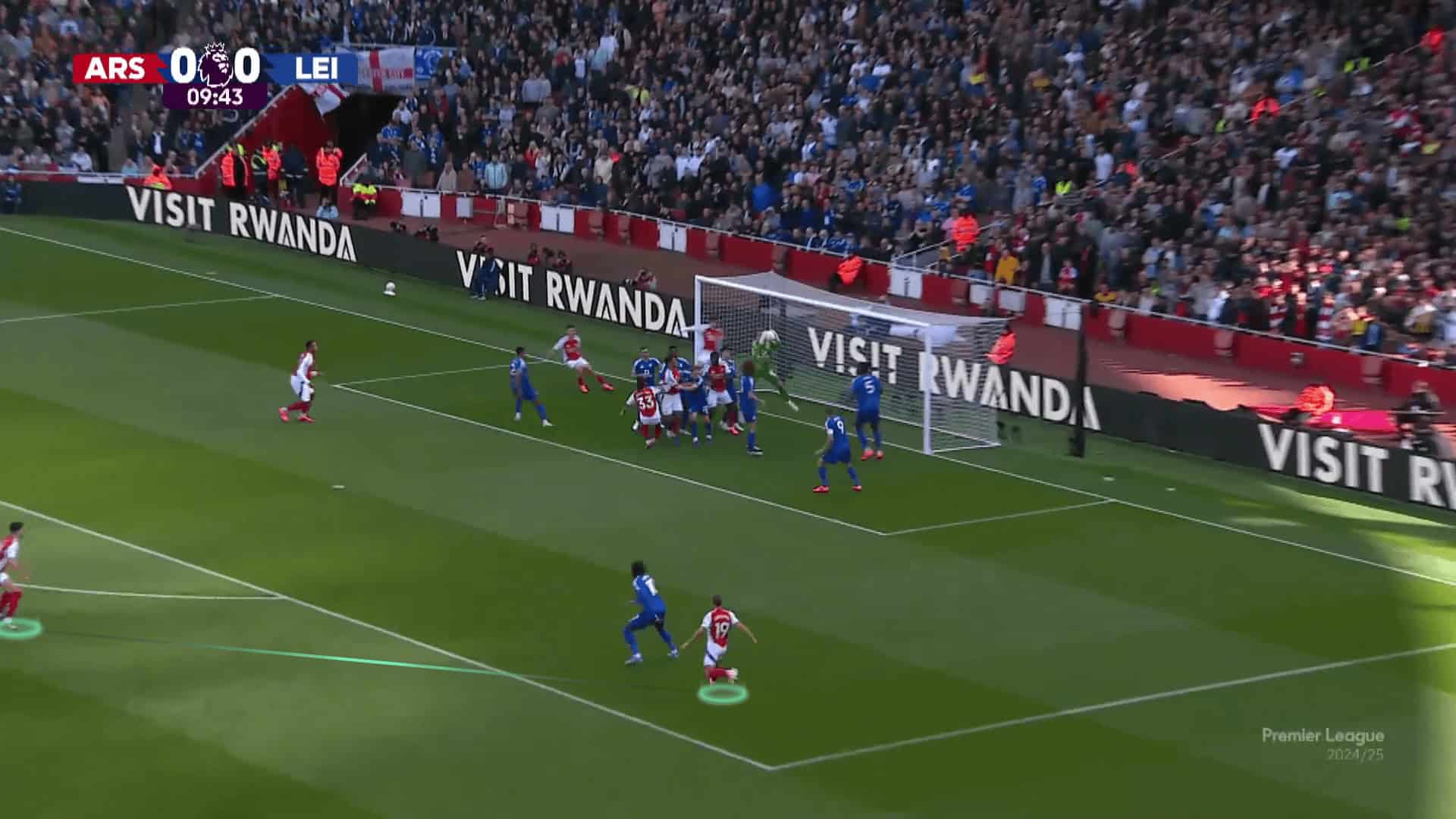

As shown in the photo below, they use a five-player pack beyond the far post, which puts them on the green zonal defenders’ blind side.

Thus, they can’t track the ball and the attackers in the air at the same time.

The same issue happens with the two-man markers in the white spot, which forces them to give their backs to the ball, and we call this issue the “orientation problem.”

Let’s move to why Gabriel Magalhães stands near the penalty spot.

Now we start with targeting the far post and how they do that, relating it to our topic.

In the photo below, Kai Havertz (white) drags his marker toward the near post and stays there to frame the goal, as we will explain.

William Saliba (blue) goes to block the goalkeeper or, let’s say, stand beside him, taking his attention and standing in his way to jump toward the far post to delay his reaction so as not to claim the ball.

This happens with many different approaches to avoid fouls, like using another player to be two players causing traffic, especially when they drag their man markers with them, standing between the goalkeeper and his way to claim the ball.

Thomas Partey and Ben White (pink) come from the last two zonal defenders’ blind side to block them, freeing the far post for Gabriel Magalhães. Gabriel Martinelli (green) frames the ball trajectory to have the chance to get the ball if Gabriel can’t.Martin Ødegaard and Bukayo Saka stand on the edge of the box while Oleksandr Zinchenko stays at the back for counterattacks. We will discuss this triangle further later on.

Regarding Gabriel Magalhães, he wants to ensure that he is separated from his marker, pushing his hands down before running to be free from any physical contact; he fakes movement to the near post and then attacks the far post.

Now, let’s see why.

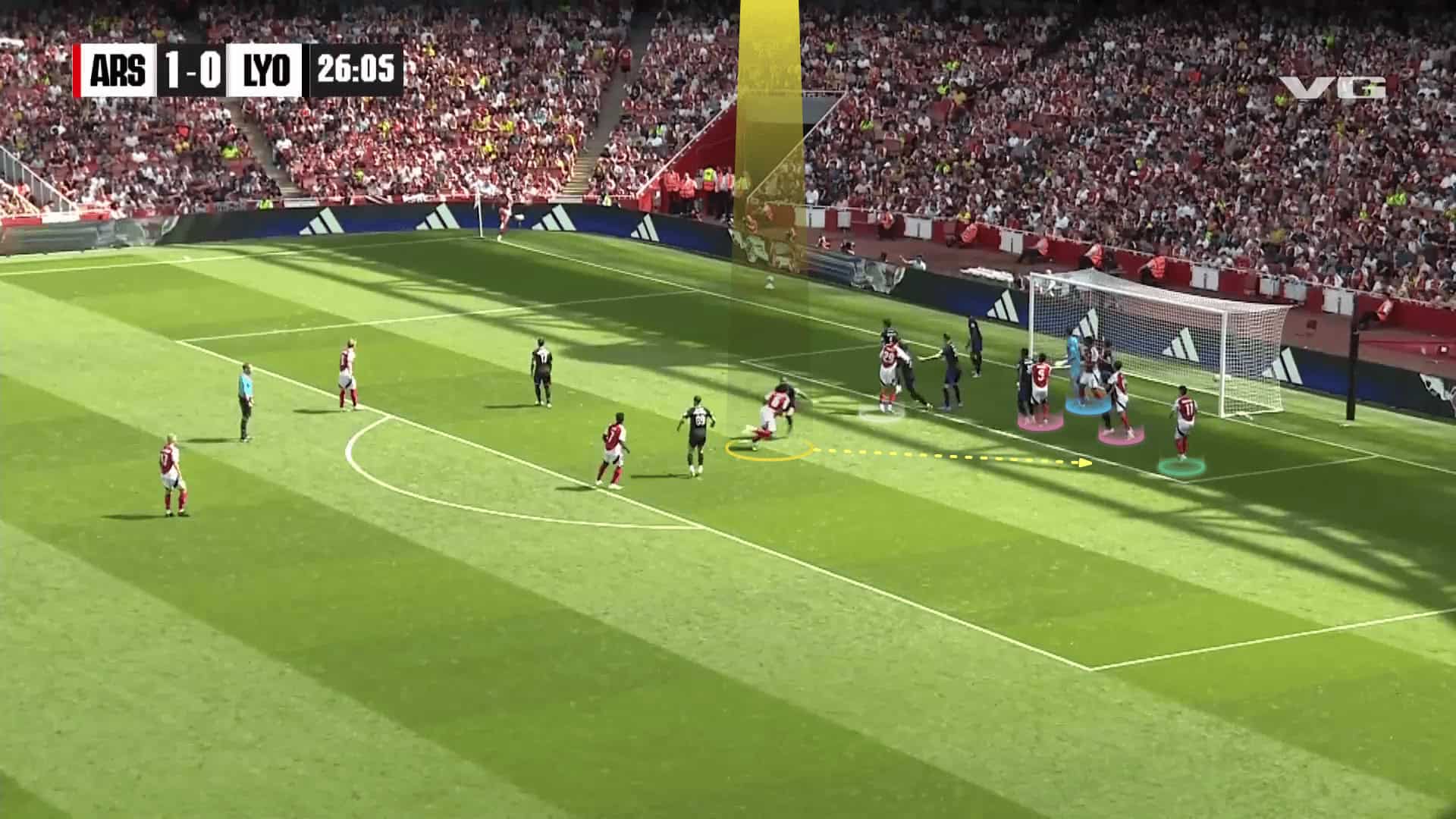

In the photo below, Gabriel Magalhães’ fake movement to the near post and then the far post gives his man markers two bad choices.

1- Turning around to keep tracking him and thus losing contact with the ball, as he did.

2- He keeps facing the ball, giving his back to Gabriel, losing contact with him.

This orientation problem gives Gabriel an advantage over his marker, but this isn’t the only advantage of this starting position.

Escaping from your man marker at this point means that he will run all that distance before reaching six yards, which means that he will have a dynamic mismatch over any stationary defender there.

In the photo below, the plan was successful, and Gabriel scored.

However, I want you to consider the potential scenarios for a floated inswinging cross that is out of reach of the goalkeeper and defenders, allowing Gabriel to showcase his abilities.

Additionally, consider the goal’s framing: you can anticipate that Martinelli is ready in case the cross is higher than Gabriel’s.

Four players are positioned on the width of the goal in case Gabriel is unable to convert the cross or if the goalkeeper saves it, ensuring they are ready to capitalise on any rebound.

This scenario limits the possibilities of a threat to the goal, whether directly or through framing the goal.

The ball could pass everyone, resulting in a goal kick, or it could be miraculously touched by the goalkeeper or a defender, turning it into a corner kick.

They generally apply the same principles with a few changes according to the opponent’s defence system.

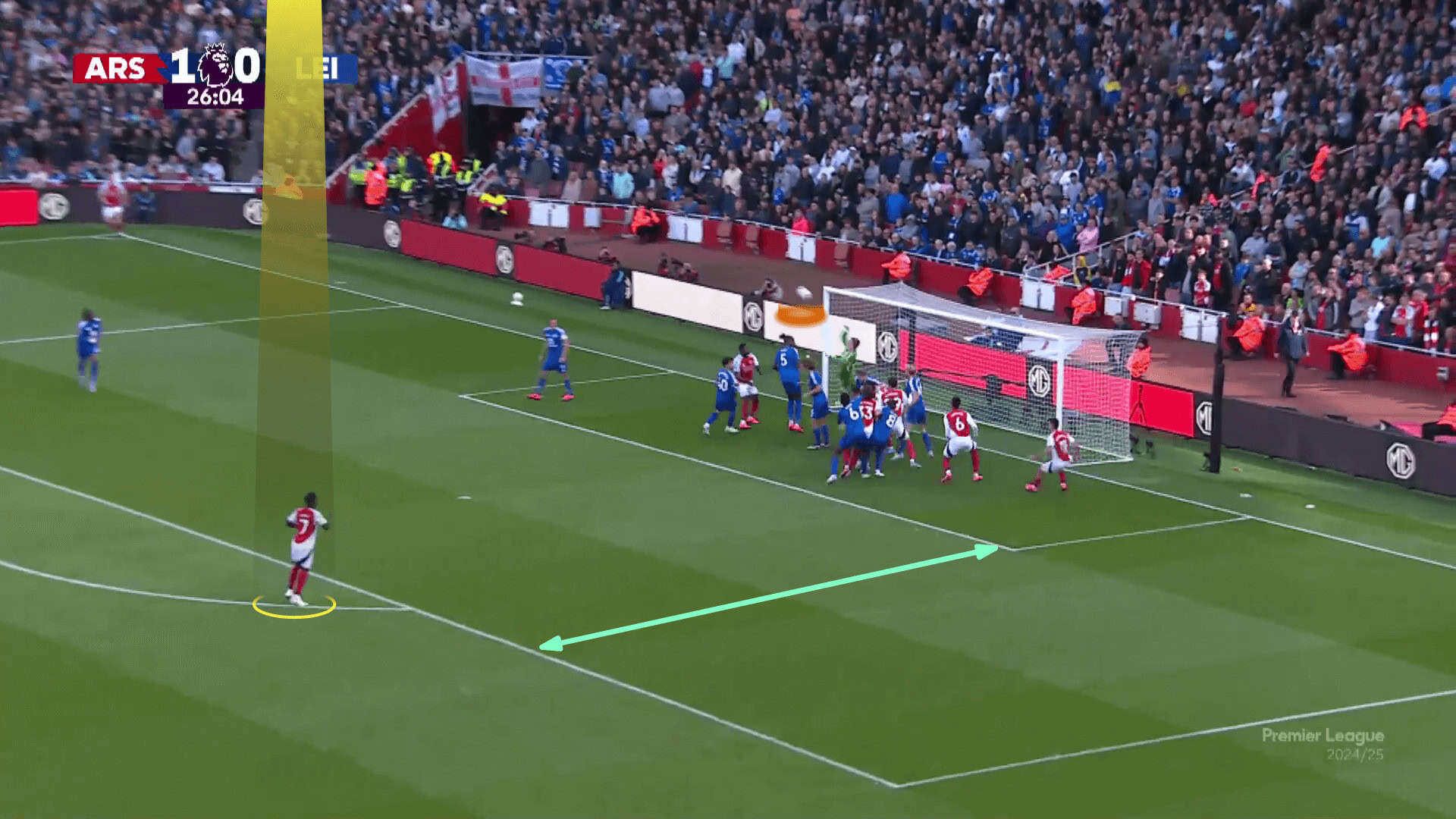

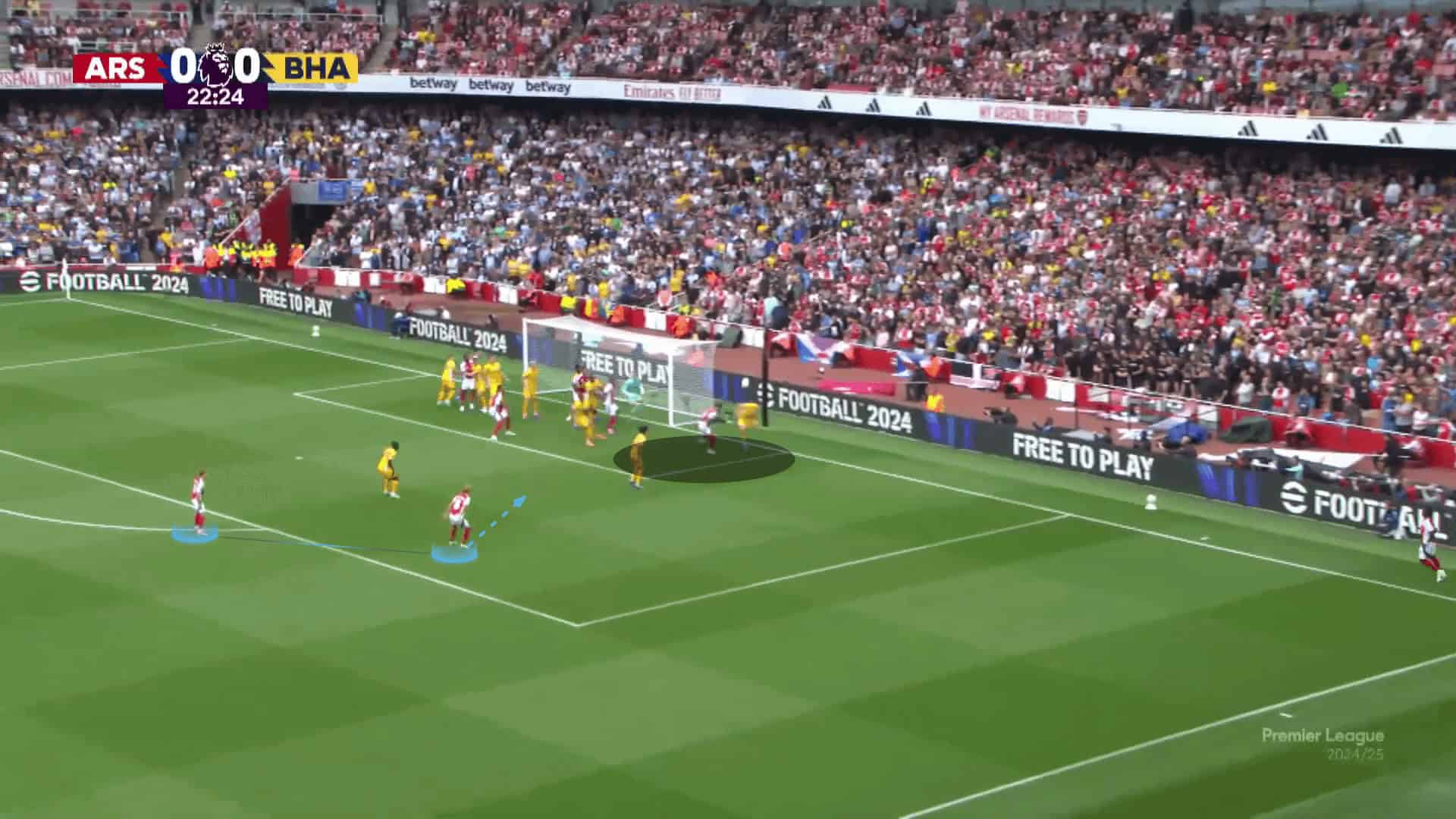

This small trick of framing the ball and the cross-flight helped them score many goals, including Leandro Trossard’s crucial third goal against Leicester City.

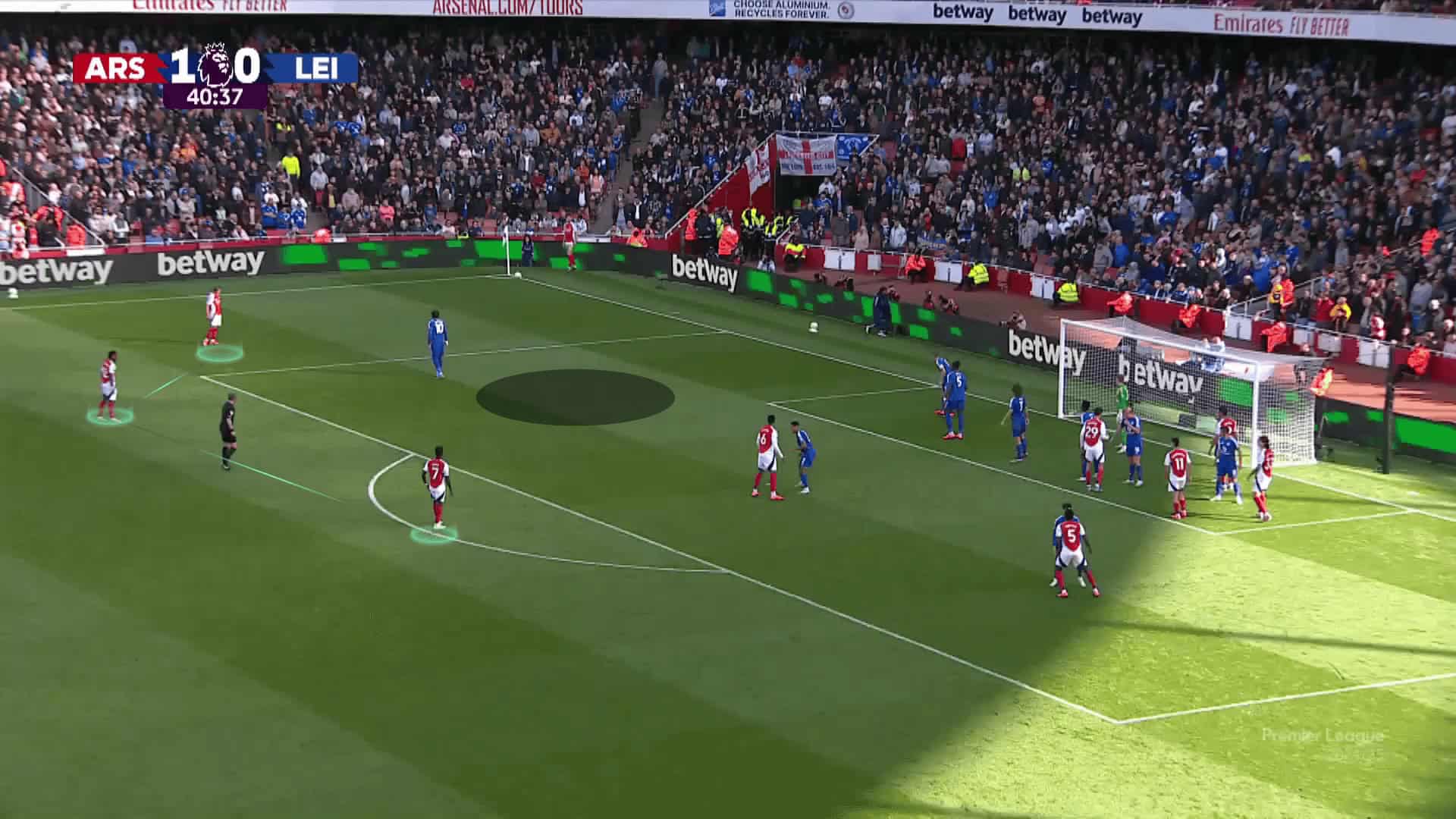

As shown in the photo below, the ball (green) is overhit, but Trossard is ready to get the ball while his teammates frame the goal inside the six-yard line.

The result was an own goal because of the incredible pressure and traffic inside the six-yard box after Trossard’s touch.

To sum up, we want to highlight that they don’t allow a vertical rebound ball from the beginning.

They keep the horizontal rebound or overhit safe while reducing the probability of a vertical dangerous rebound ball because of the floated, in-swinging cross.

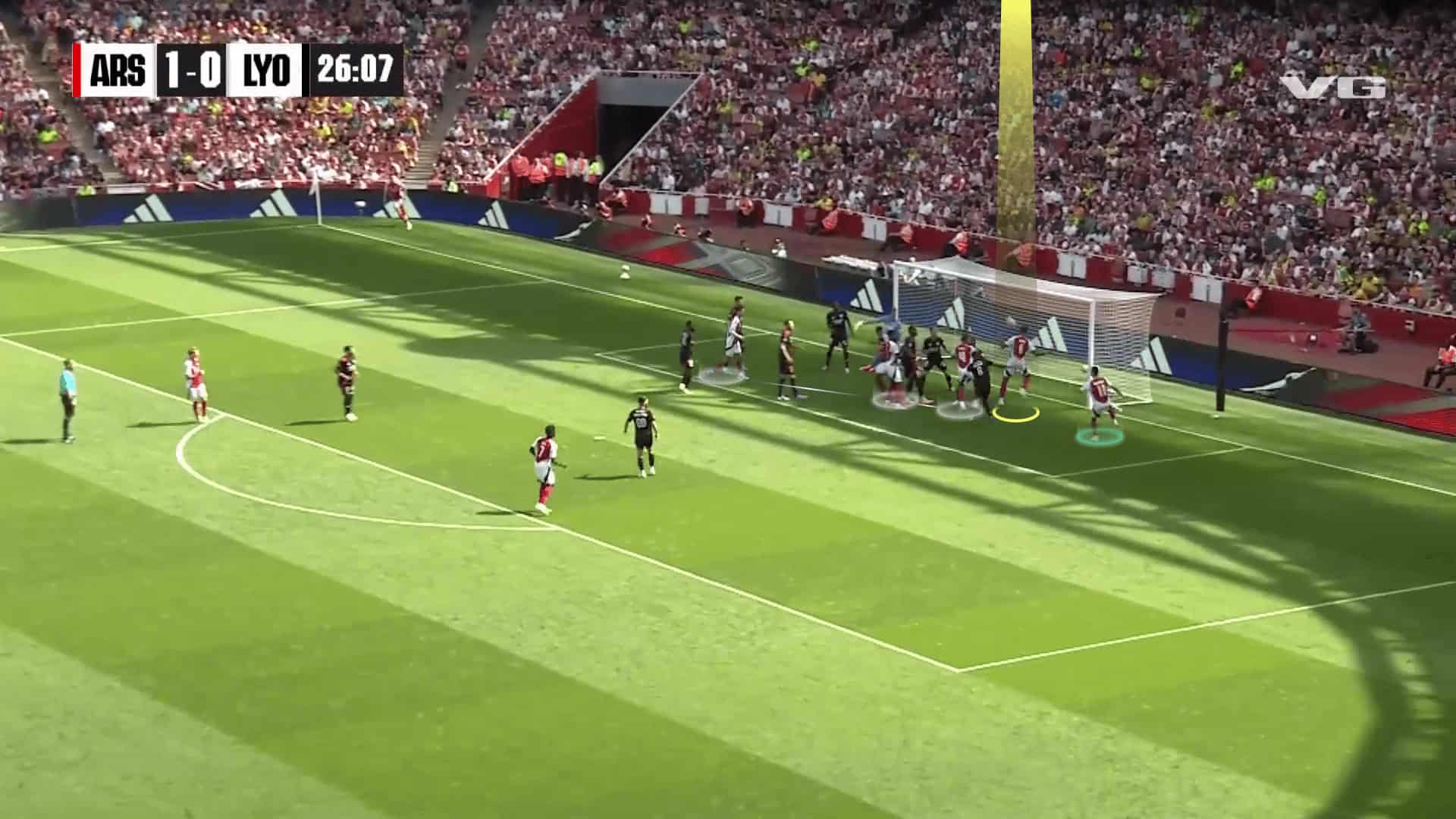

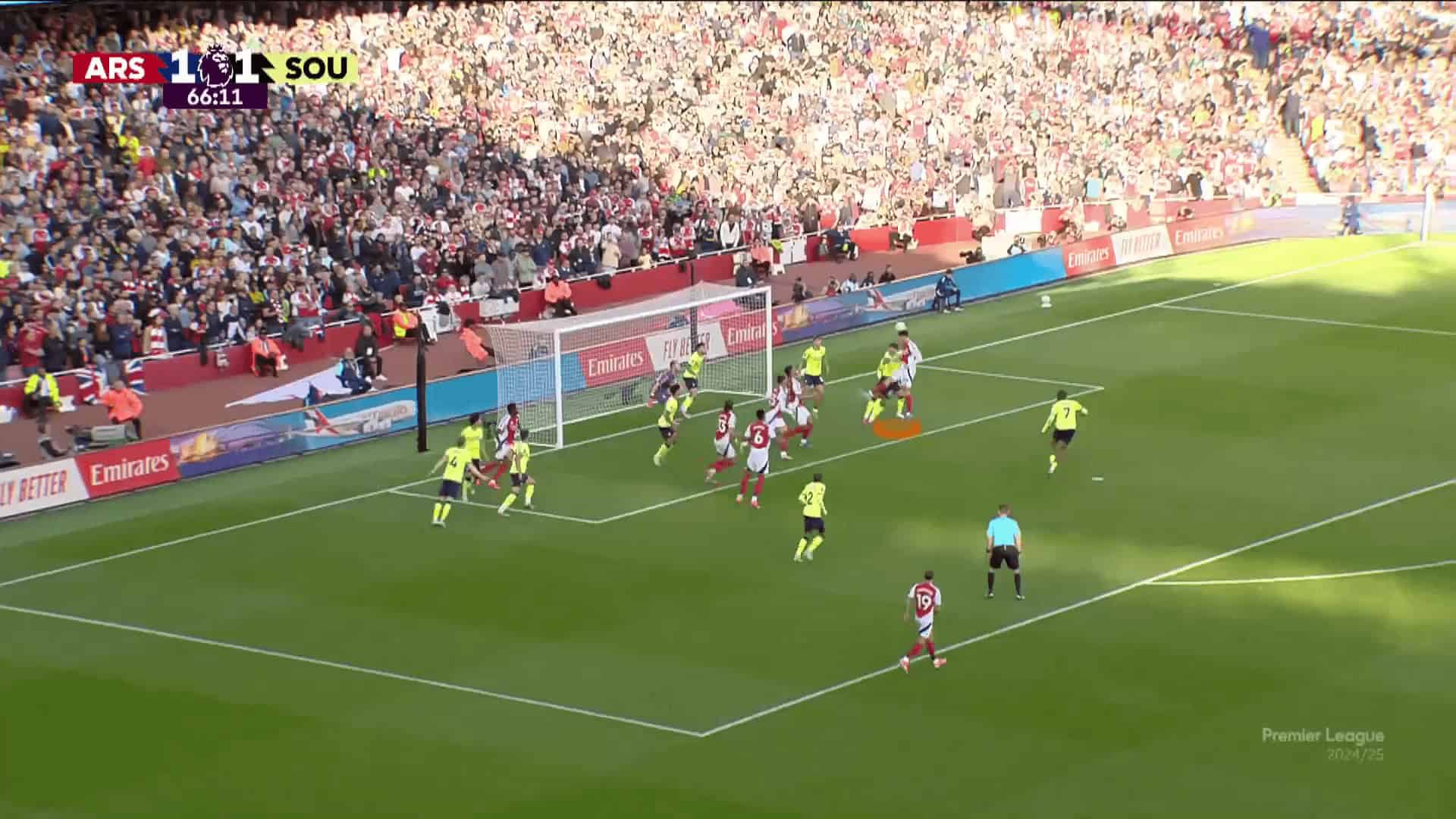

In the case below, we want to highlight how hard the goalkeeper can punch the ball into the ground to be a rebound ball.

Saliba (green) stands in his way to slow him down while the three blue players block the last zonal defenders, preventing them from stepping back to the targeted area beyond the far post for Havertz and Gabriel (Orange), who have a dynamic mismatch.

As shown below, the goalkeeper can push Saliba away, but there is still traffic between him and the targeted area.

In the end, he hardly touches the ball, which is the maximum action he can take, resulting in another corner without a second rebound wave.

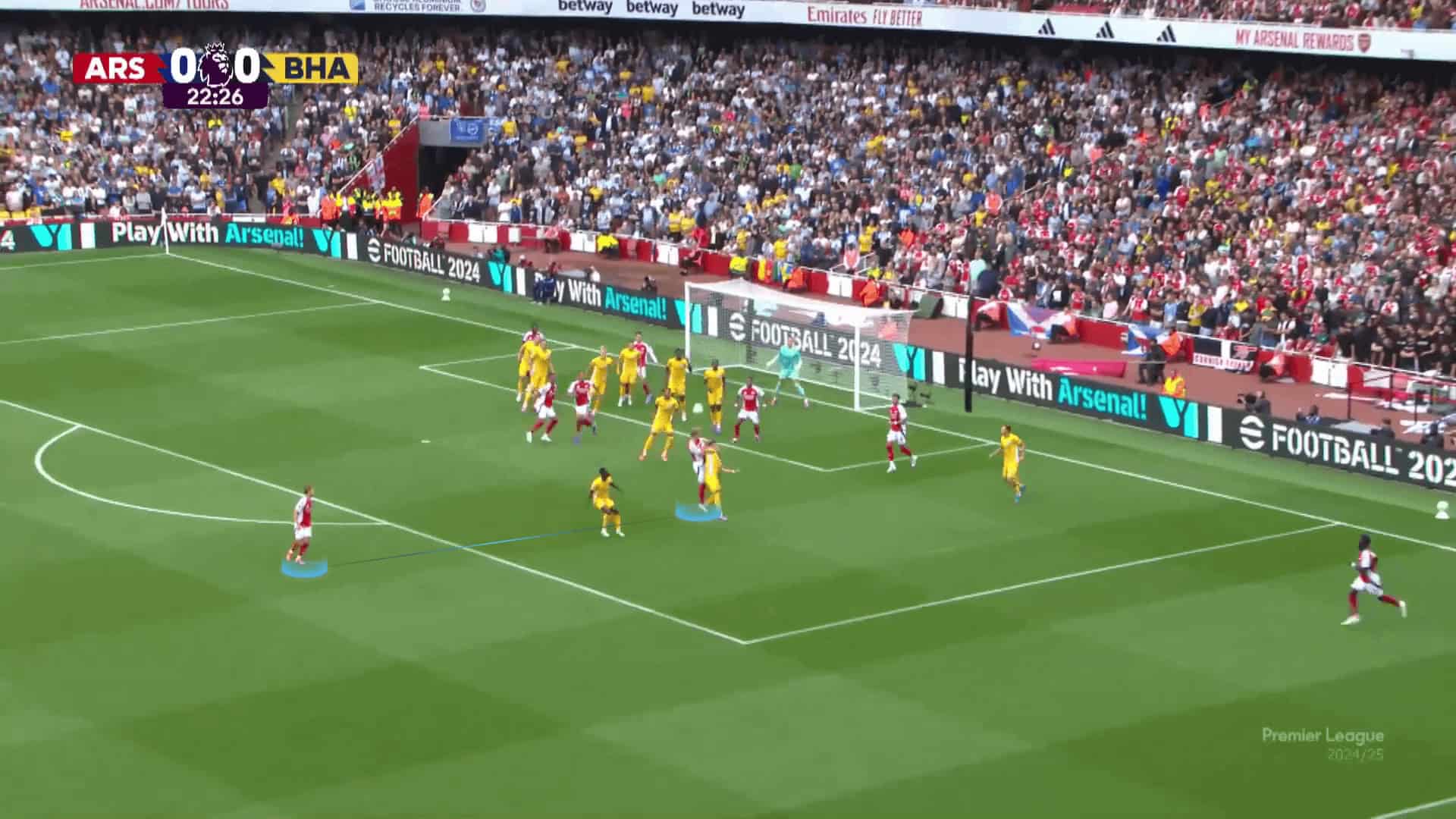

Targeting The Near Post With Overloading

As we have seen above, they want to overload the targeted area with more than the targeted player, but overloading is clearer while targeting the near post.

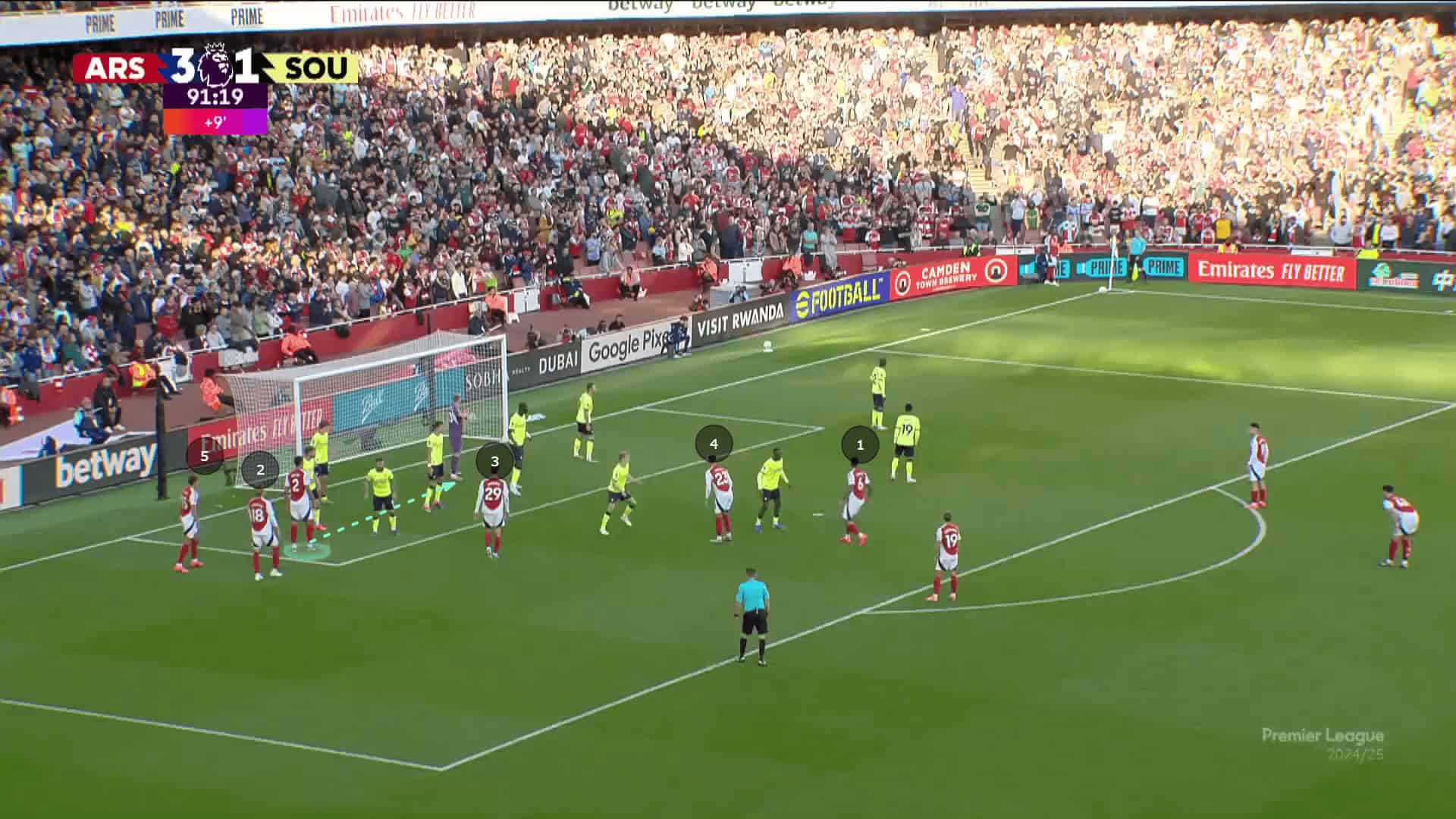

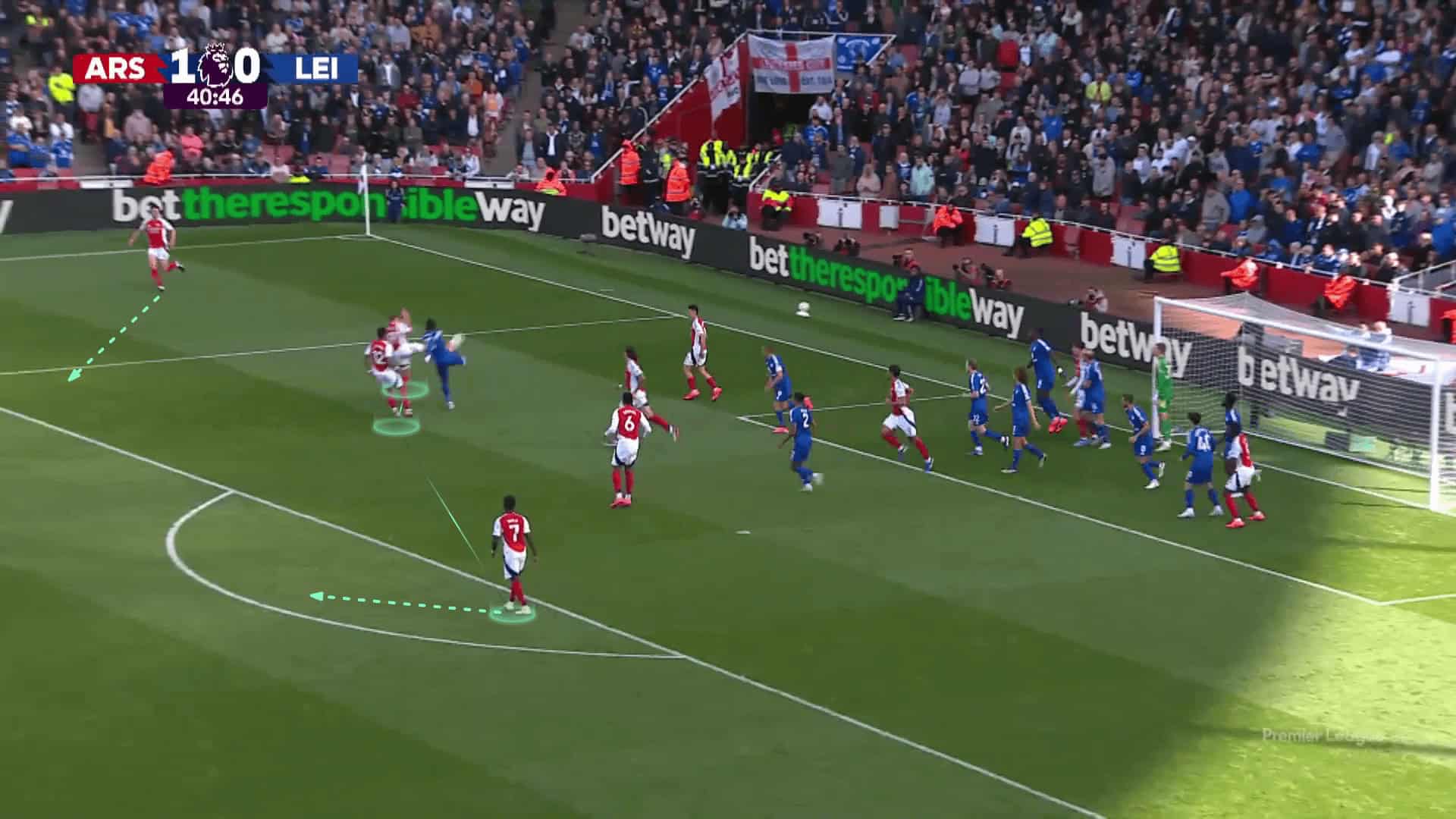

In the photo below, they target the near post, and the players are numbered according to their positions from the near post to the far post, while Saliba (green) goes to the goalkeeper as usual.

Their attacking strategy is to drag the first two zonal defenders inside the front of the six-yard box to overload the area behind them with the remaining three players.

The plan works, and Havertz flicks the ball on, as shown below

However, the goalkeeper saves it; then, the chaos begins in that overloaded area.

Below, you can see that Arsenal could score from a position near the post, highlighted in the image, in a very dangerous position thanks to their overloading, which causes the rebound ball to end here.

They also use the same frame of the goal to secure the rebound horizontally.

As shown below, the opponent manages to get the first touch at the near post, but two players frame the rest of the goalmouth.

One of them, Havertz, manages to get the second ball and threaten the opponent’s goal.

Being Ready For The Rebound

You may be asking, what if the goalkeeper or the defender manages to make a rare claim of the ball inside the box?

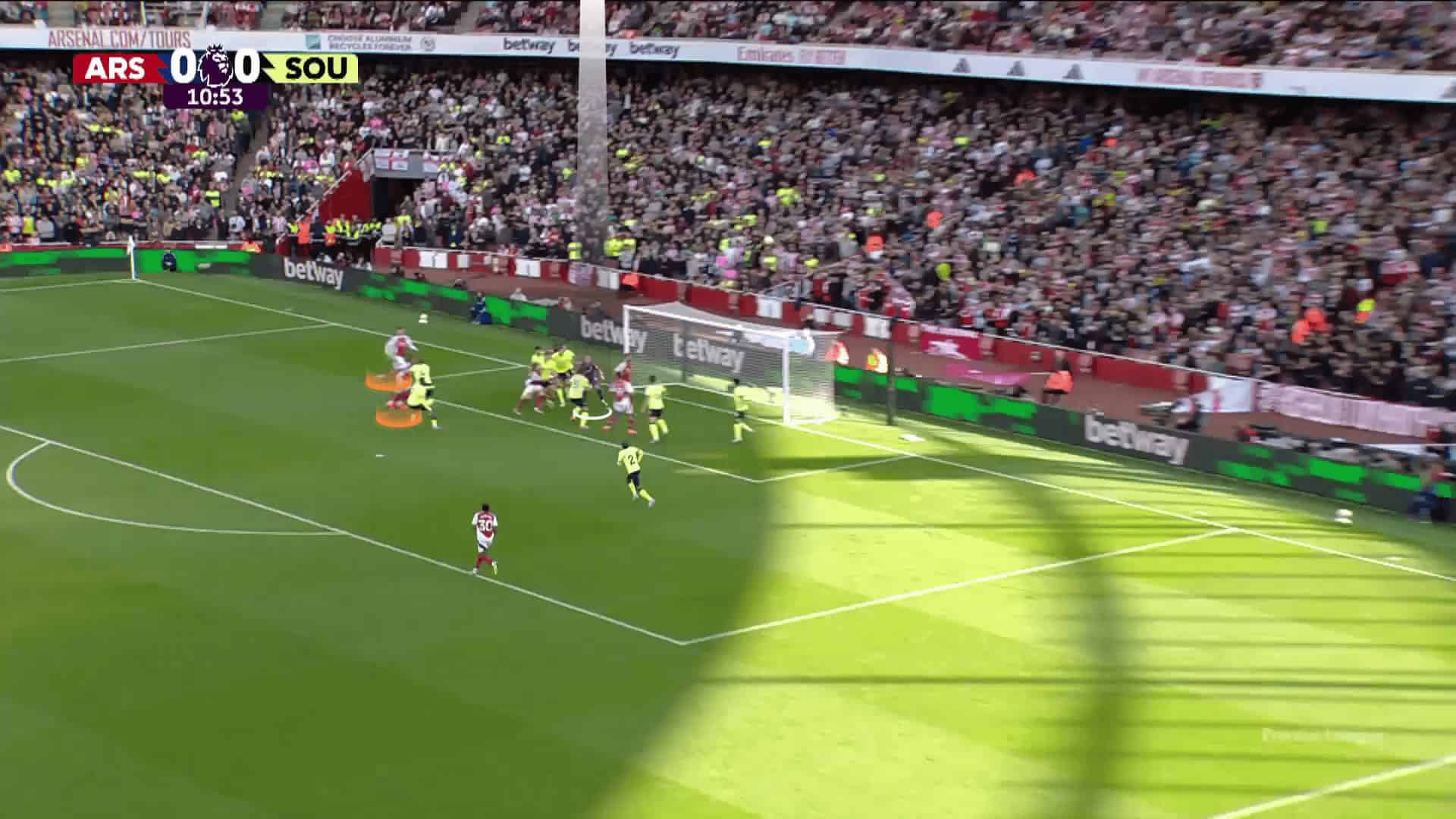

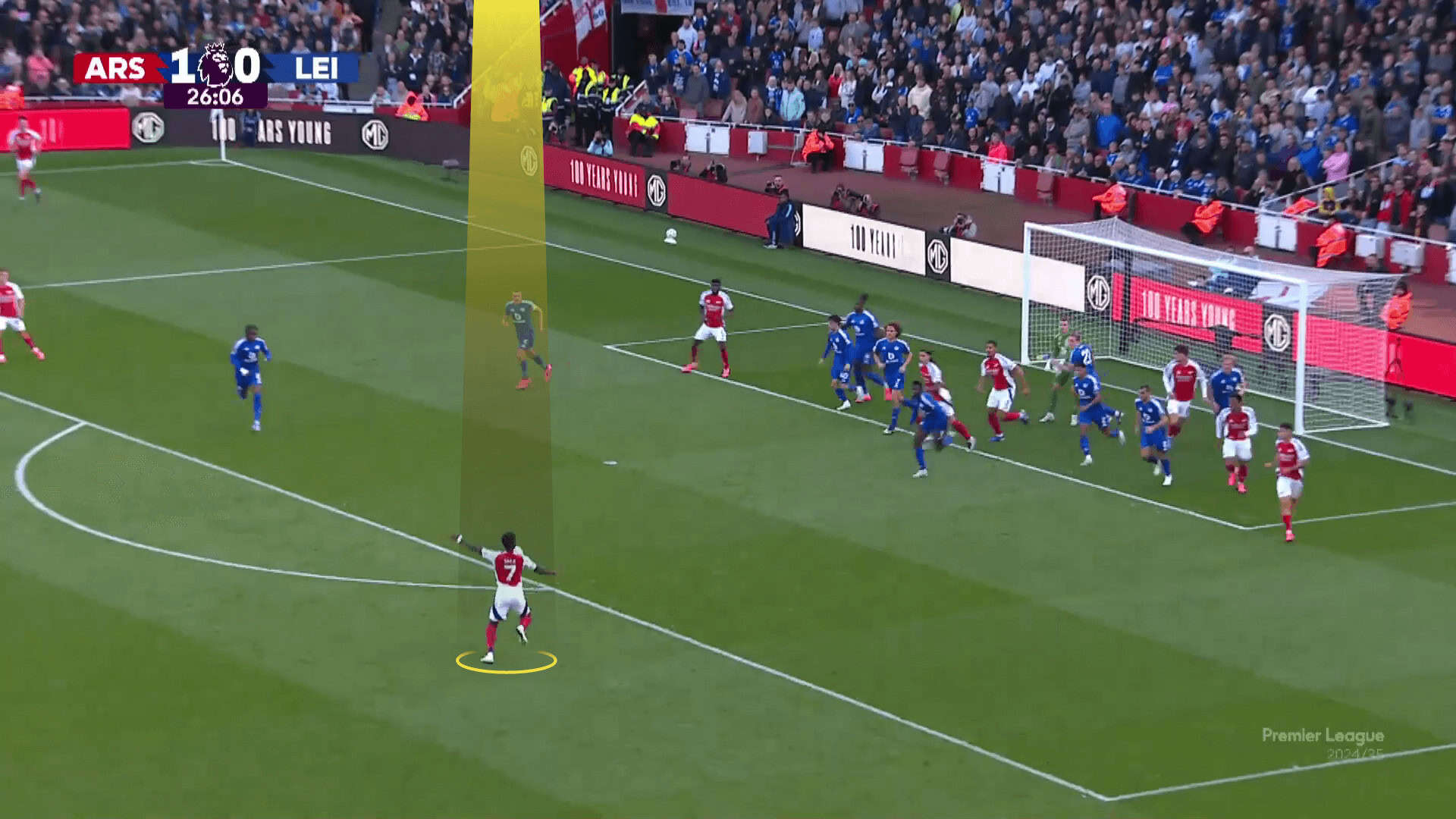

As shown below, they can harm opponents from the rebound because all of the defenders are dragged into the six-yard box, leaving one defender responsible for the edge of the box.

This defender is coming from a distance because of a probable short option.

In the end, the area between the six-yard box and the edge of the penalty box is so empty, especially against teams that have man markers who can be dragged inside the six-yard line, not a second line or just blockers outside the six-yard line.

Saka can exploit this zone and harm the opponent with a shot.

You may now ask about their reaction when the opponent has enough players on the edge of the box or between it and the six-yard area, so there is no escape from a rebound ball.

Let’s see below how they react when they need to retain pressure and kill the counterattack from the beginning.

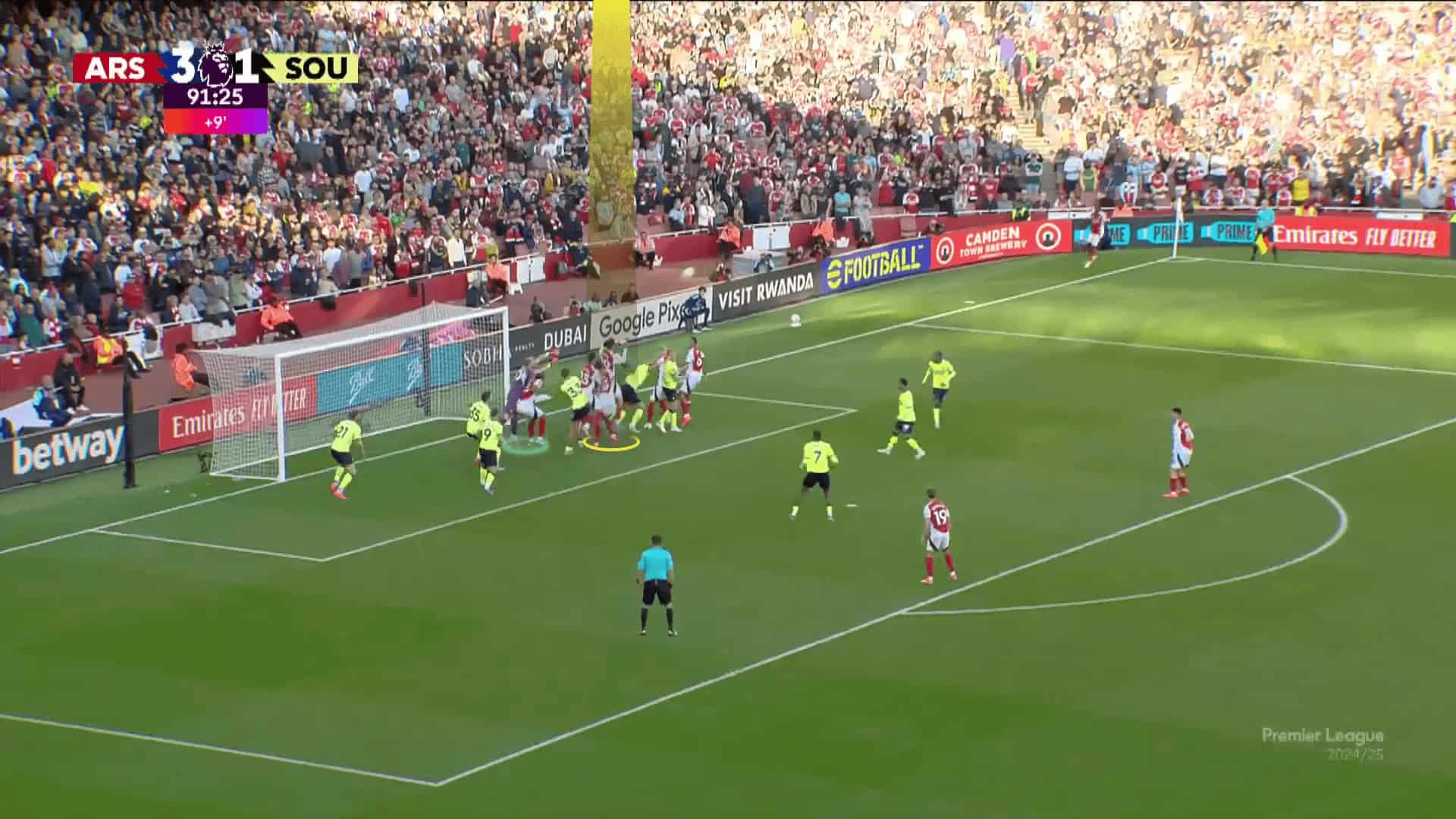

As in the case below, Arsenal’s two rebound players are standing very close to the edge of the box with a mentality of relentless pressure rather than retreating.

The player on the ball’s side goes into the box to press, preventing the opponent from setting up a good counterattack.

They also instruct these two players to adapt to the targeted area, meaning they stand toward the near post if the targeted area is there.

This allows these players to press in high positions and get the ball back to prevent any counterattack while also allowing them to keep their attack going, as in the two photos below.

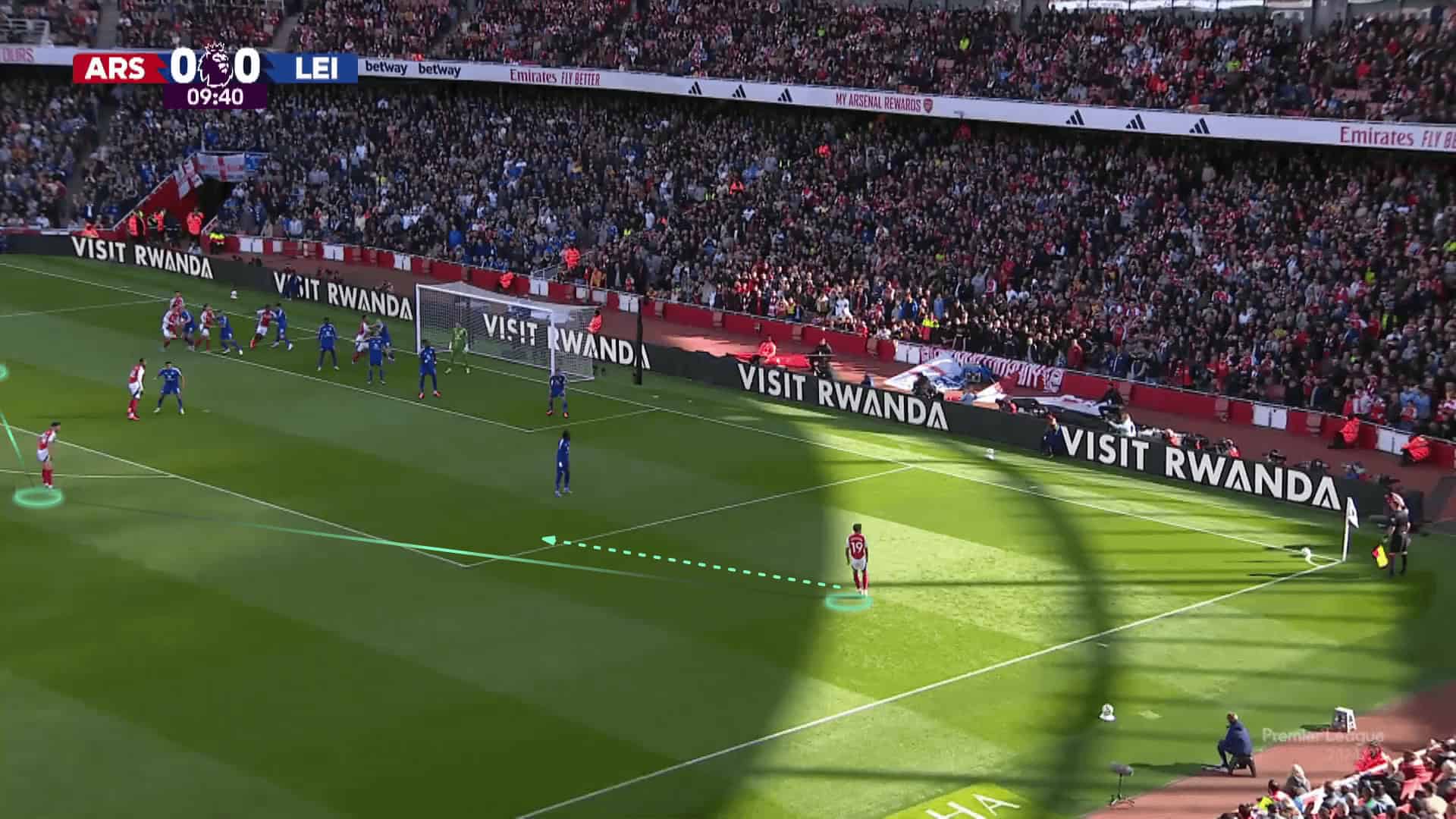

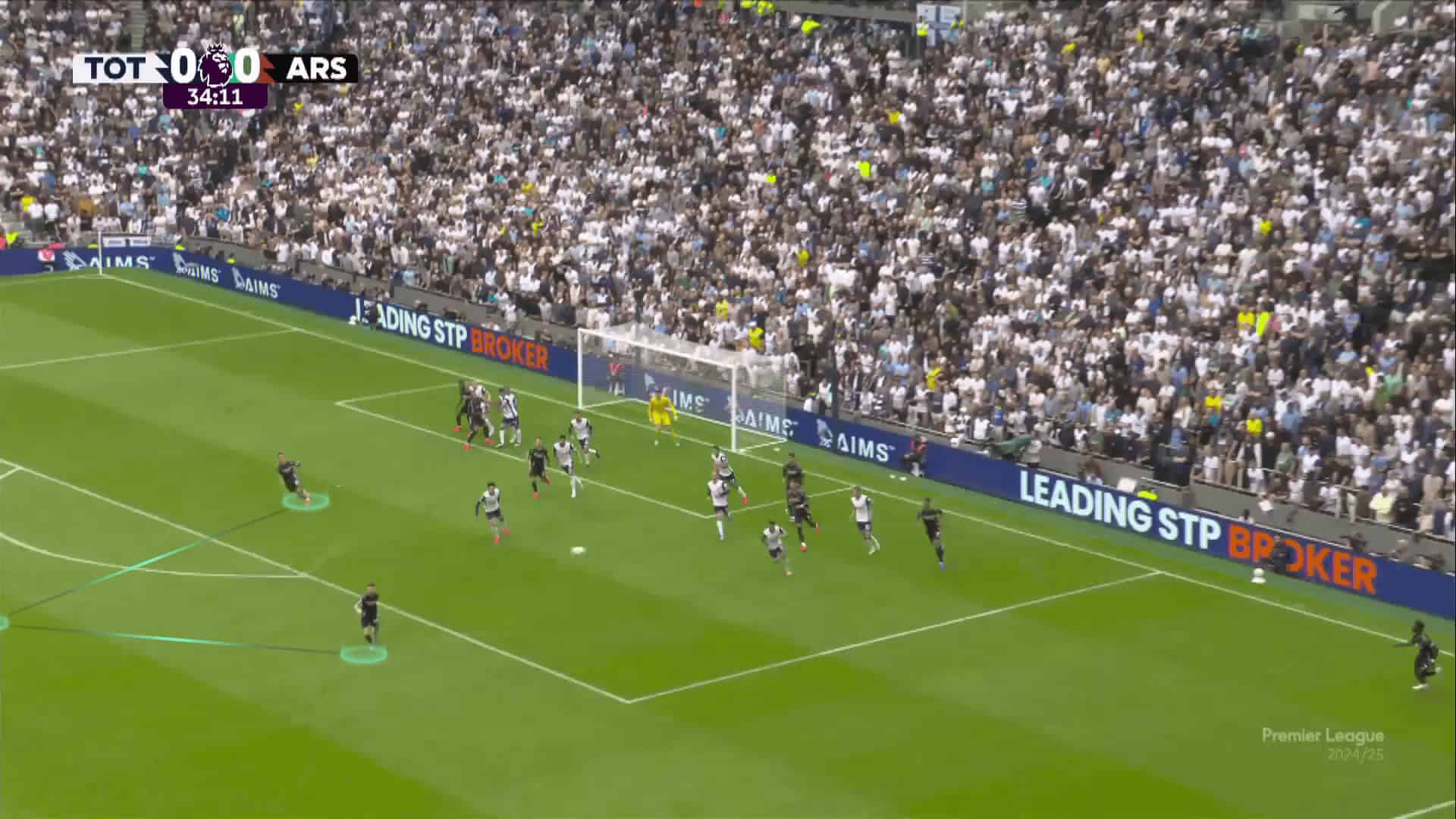

After the first two players are on the edge of the box, a ‘security player’ is behind them, ready for counterattacks in case the goalkeeper can catch the ball, which is rare.

Note: One of the rebound players may go near the taker at first as a fake short option to drag the first zonal defender further forward or for other tactical purposes.

However, he goes back inside as the taker moves to keep the same triangle ready.

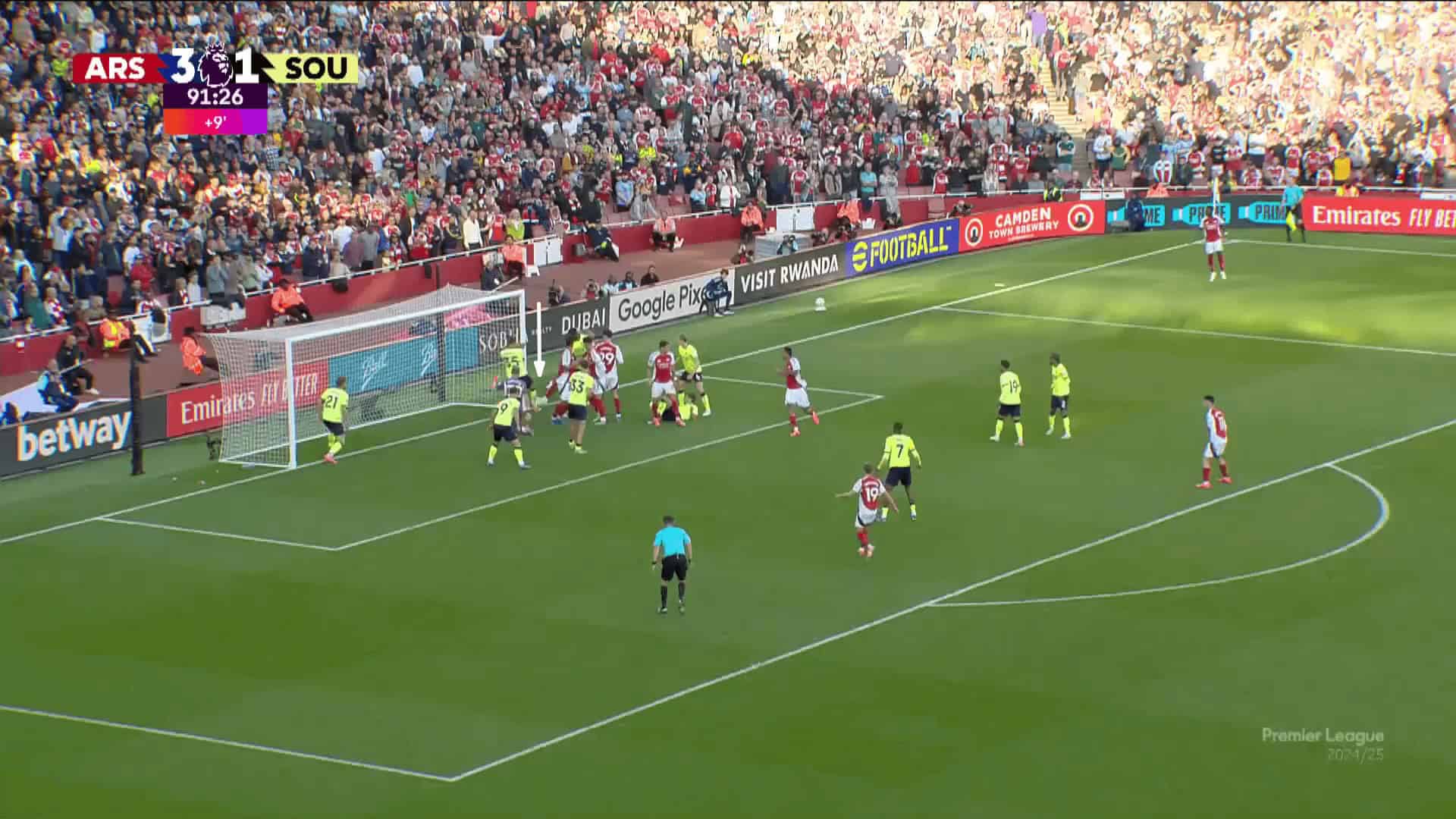

The goalkeeper manages to catch the ball and sends a long ball, so the security player in the middle will run back directly.

Below, we see the security plan being performed perfectly.

Even this security player in the middle can press roughly if the ball lands near him with the far rebound player and the taker cover behind him, as shown in the two photos below.

After all of that, the goalkeeper stands in the middle of the pitch trying to help in any probable counterattack, as in the two photos below.

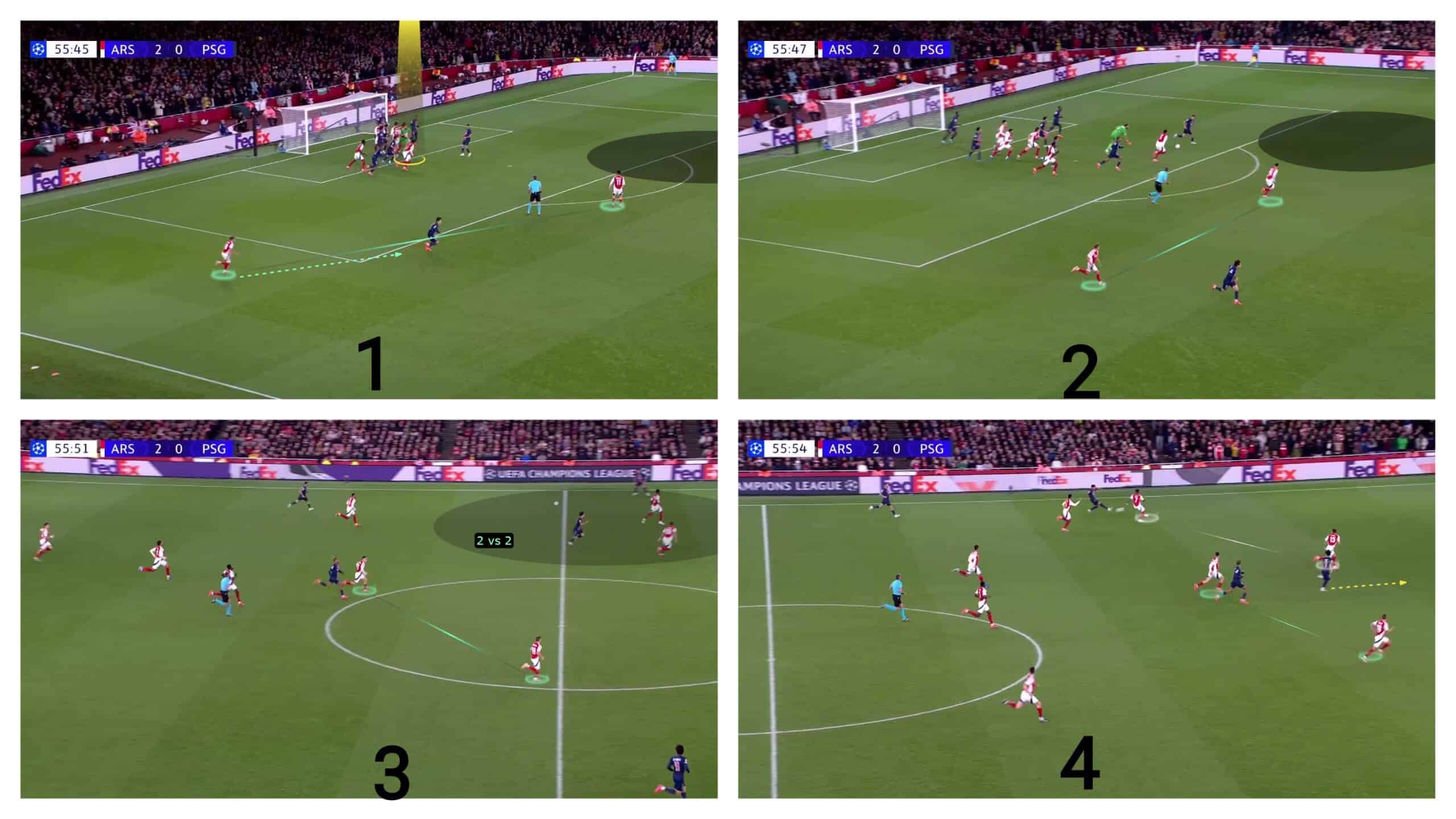

In terms of a weakness, against PSG, the French team put two attackers in the front during the corner, which may have been a prepared trick or a reaction to being down 2-0; nevertheless, let’s follow the consequences.

In the first photo below, Gianluigi Donnarumma catches the ball while we see two green rebound players, not three, so where is the third one on the right side?

In the second photo, he passes the ball to a player on the empty side who can dribble in a dangerous counterattack.

The answer is in the third photo, in which Arsenal fixed two players with them to be in a 2-v-2 situation at the back, dispensing with one of the six attackers inside the box and one of the three rebound players.

In the fourth photo, PSG’s player can perform a good through ball, but it isn’t accurate, so the goalkeeper gets it.

However, it is difficult to say that this is a weakness because they weren’t really troubled and because it is difficult to follow that strategy for the long term, leaving Arsenal’s monsters inside the box dispensing with two defenders, but it is just worth mentioning for probable future possibilities.

Conclusion

In this analysis, we have tried to explain Arsenal’s excellence in attacking corners from a different perspective than usual, highlighting that they always want to make sure that they are safe and secure defensively while attacking corners.

In this set-piece analysis, we have also shown how their attacking strategy has resulted in them not receiving a lot of counterattacks because they make it hard for the opponent to clear the ball comfortably besides their rebound scheme, which makes them excellent at rest defence and ready to press aggressively besides being safe at the same time.

Comments