Two years after winning the league, Atlético Mineiro find themselves in 10th place. Although only six points off of second-placed team Grêmio, the side have only managed one win in their last four games. After the sacking of Eduardo Coudet, Luiz Filipe Scolari agreed to take the reigns of the club, coming out of retirement in order to do so. However, the former Premier League and Brazil national team head coach has failed to win a game in his first four as boss.

This scout report will provide a tactical analysis of Scolari’s side and explain why Scolari’s principles and tactics in possession are yet to bear fruit in the attacking phase of the game.

Atlético Mineiro in attack: their general structure

Over the last four games, Atlético Mineiro have averaged 1.18 xG per game with 17.8 progressions into the final third. This suggests that the side have had trouble creating quality chances — and consistently being able to progress the ball into positions from where they can create chances.

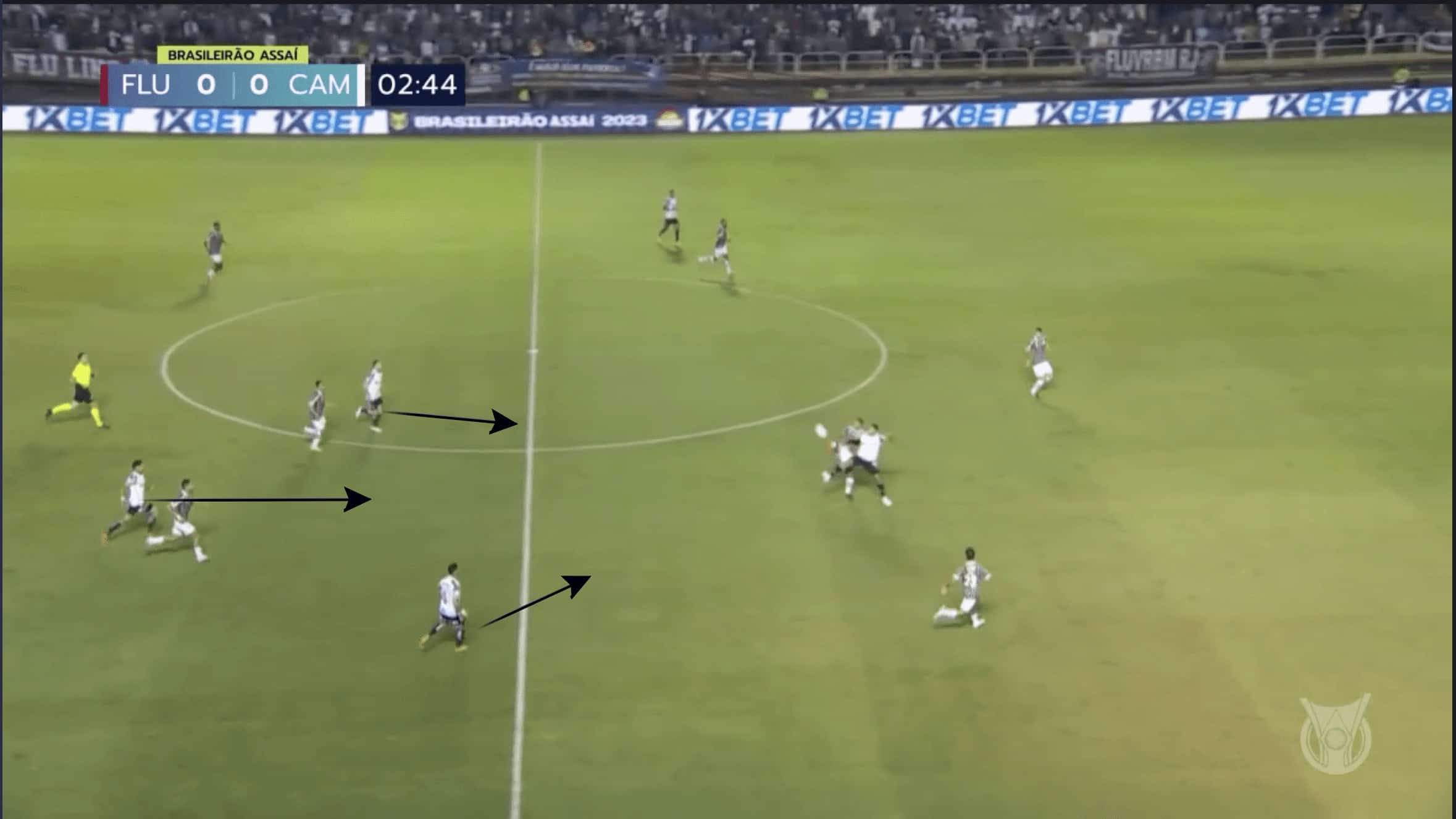

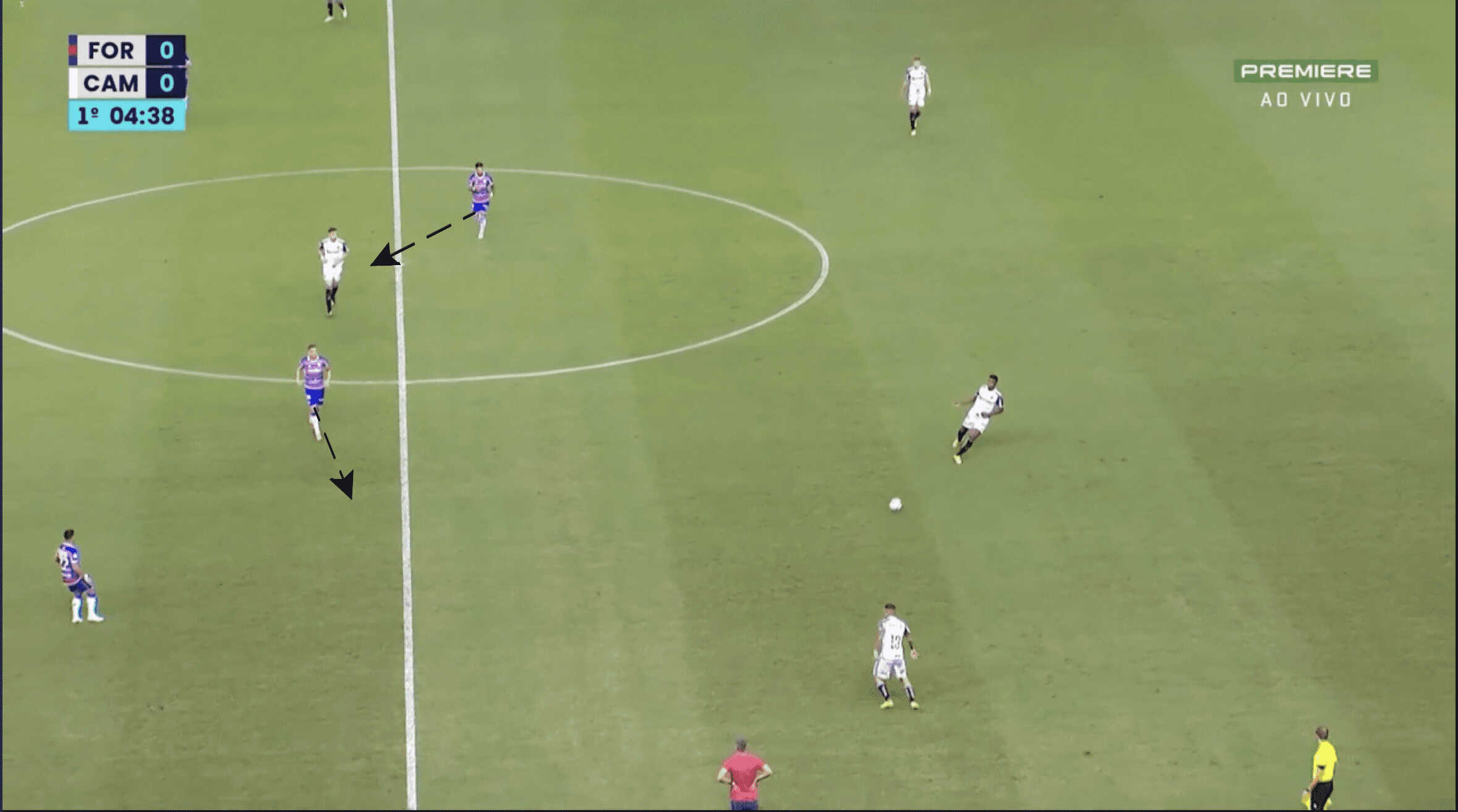

In their first games under Scolari, the side have lined up in a 4-3-3 with a consistent trend of using a back four in the build-up, with Rodrigo Battaglia as a lone pivot. One of the other two midfielders may drop deeper and occasionally join Battaglia. Still, both midfielders mostly advance close to the last line of the attack, with the wingers maintaining width. This can be seen in the image below.

Due to the nature of their structure and the positioning of their midfielders, it is unsurprising that Atlético Mineiro do not look to play passes on the ground through the centre. Nevertheless, there have been instances, especially in their first game under Scolari, where they have attempted to find these midfielders with vertical passes. The use of long balls to the striker has been consistent throughout all their games, as well as attempts to progress the ball through the wide areas, especially in the half of the opposition.

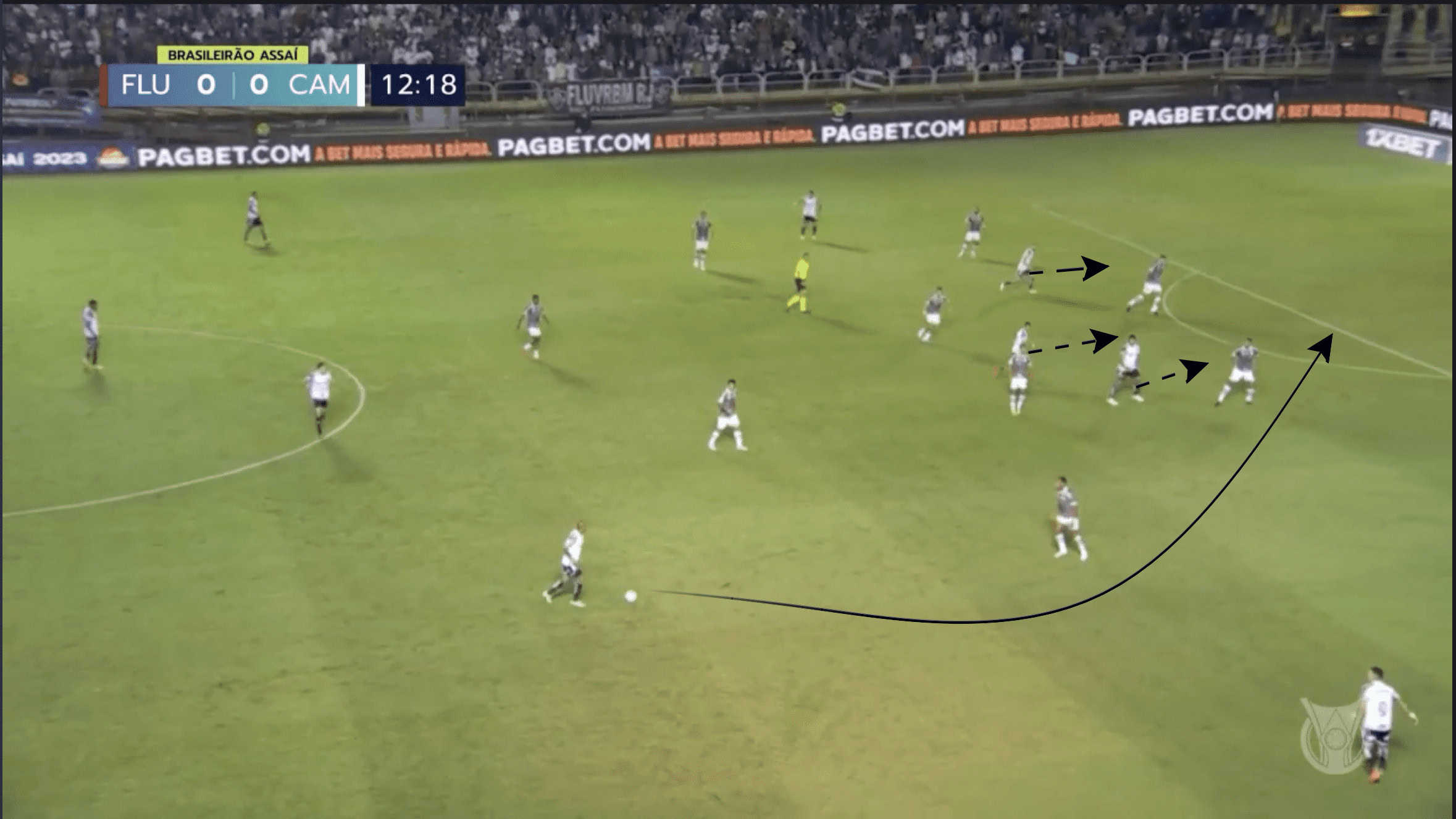

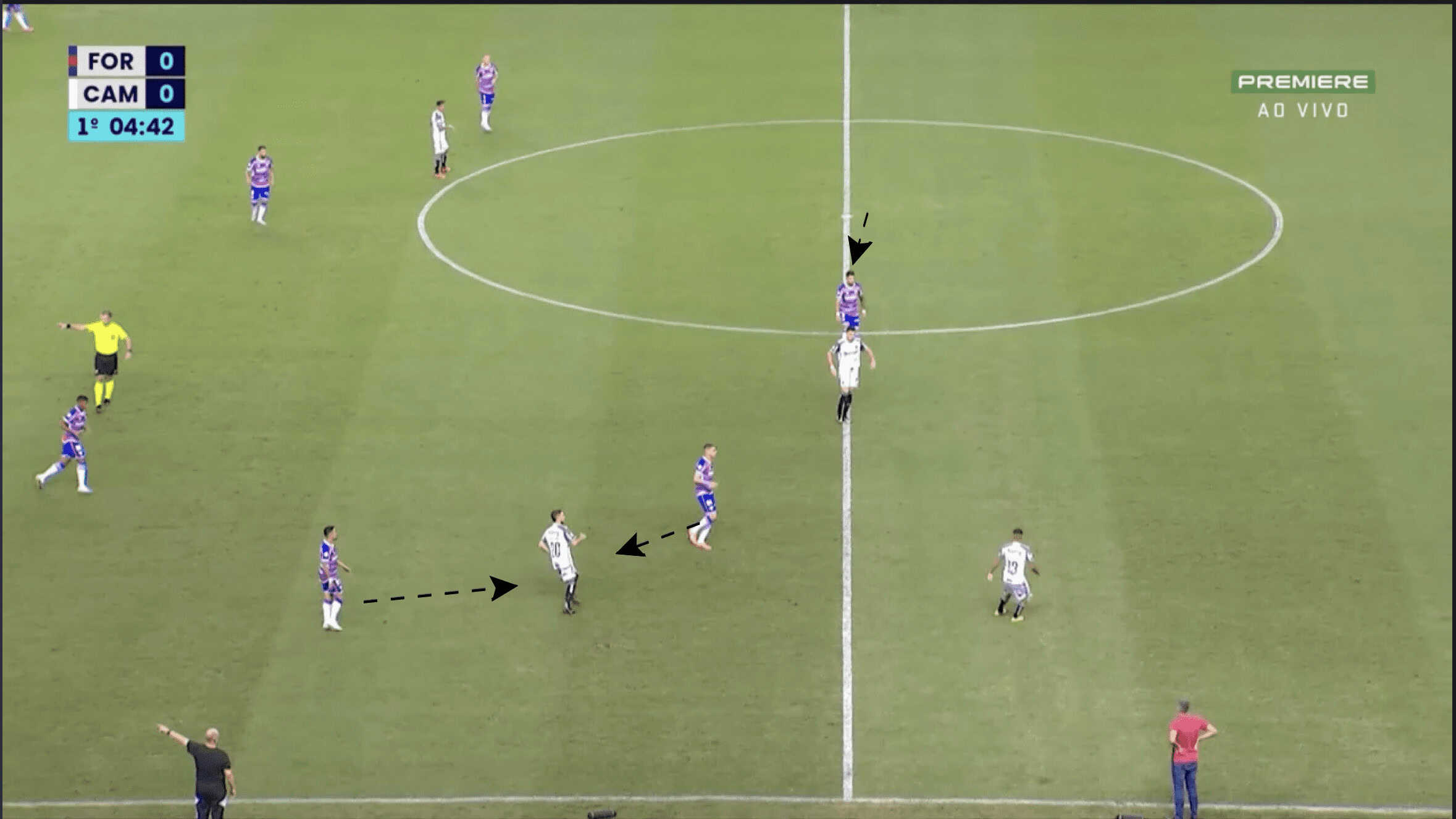

An example of how Atlético Mineiro’s structure allows their use of long balls to be more effective can be seen below. Rather than play the ball to the centre-backs or to Battaglia — Everson — the goalkeeper, plays a long ball to Hulk.

From this position, Hulk lays the ball off to the advanced central midfielders as well as the winger. Matías Zaracho, Hyoran Dalmuro and former MLS player Christian Pavon move closer to the ball in this scenario. In this type of situation, the midfielders, as well as the wingers, are in a closer position to receive the ball from Hulk and are also in close enough proximity to challenge for the second ball if the striker is not able to find any of them.

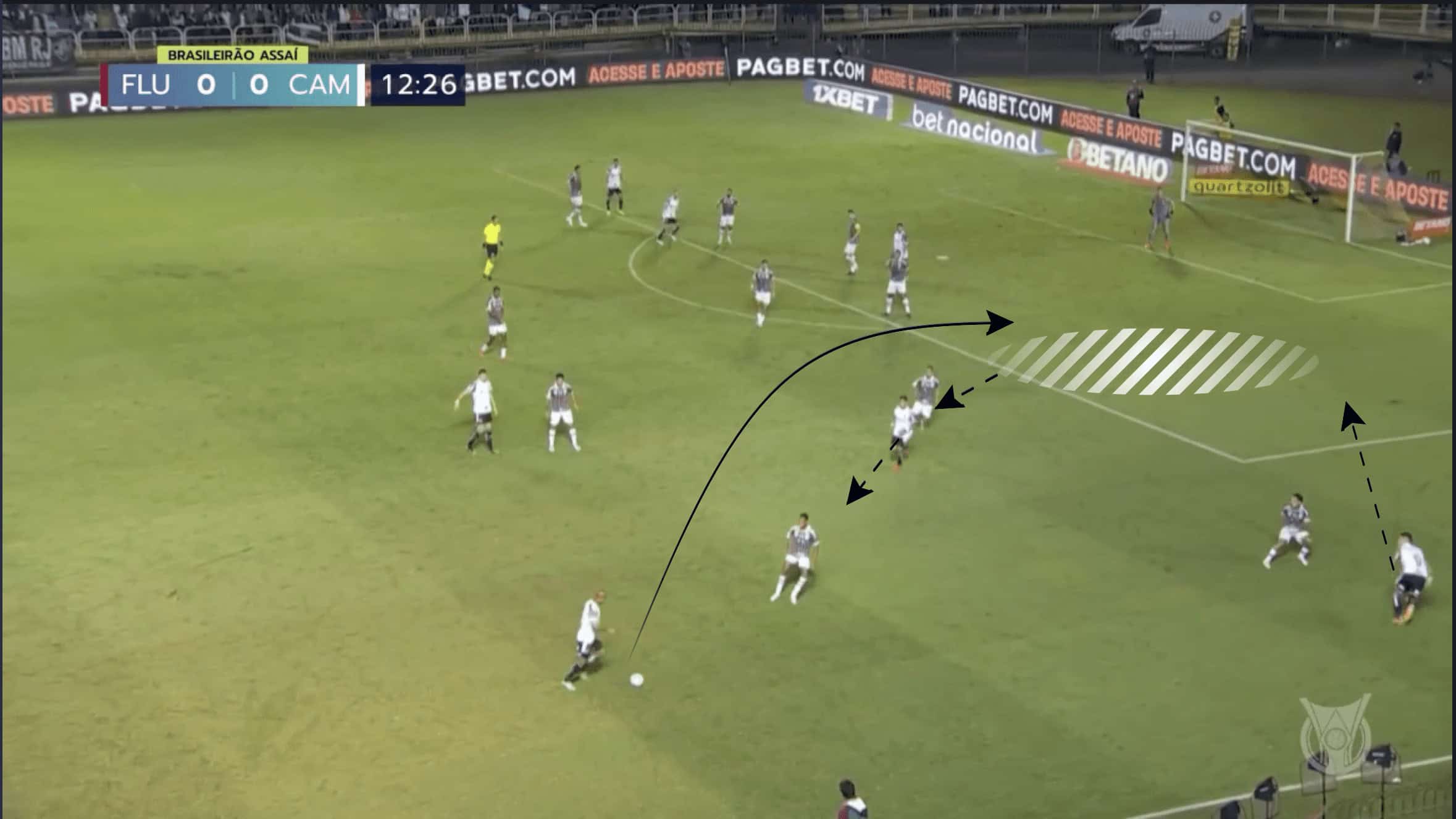

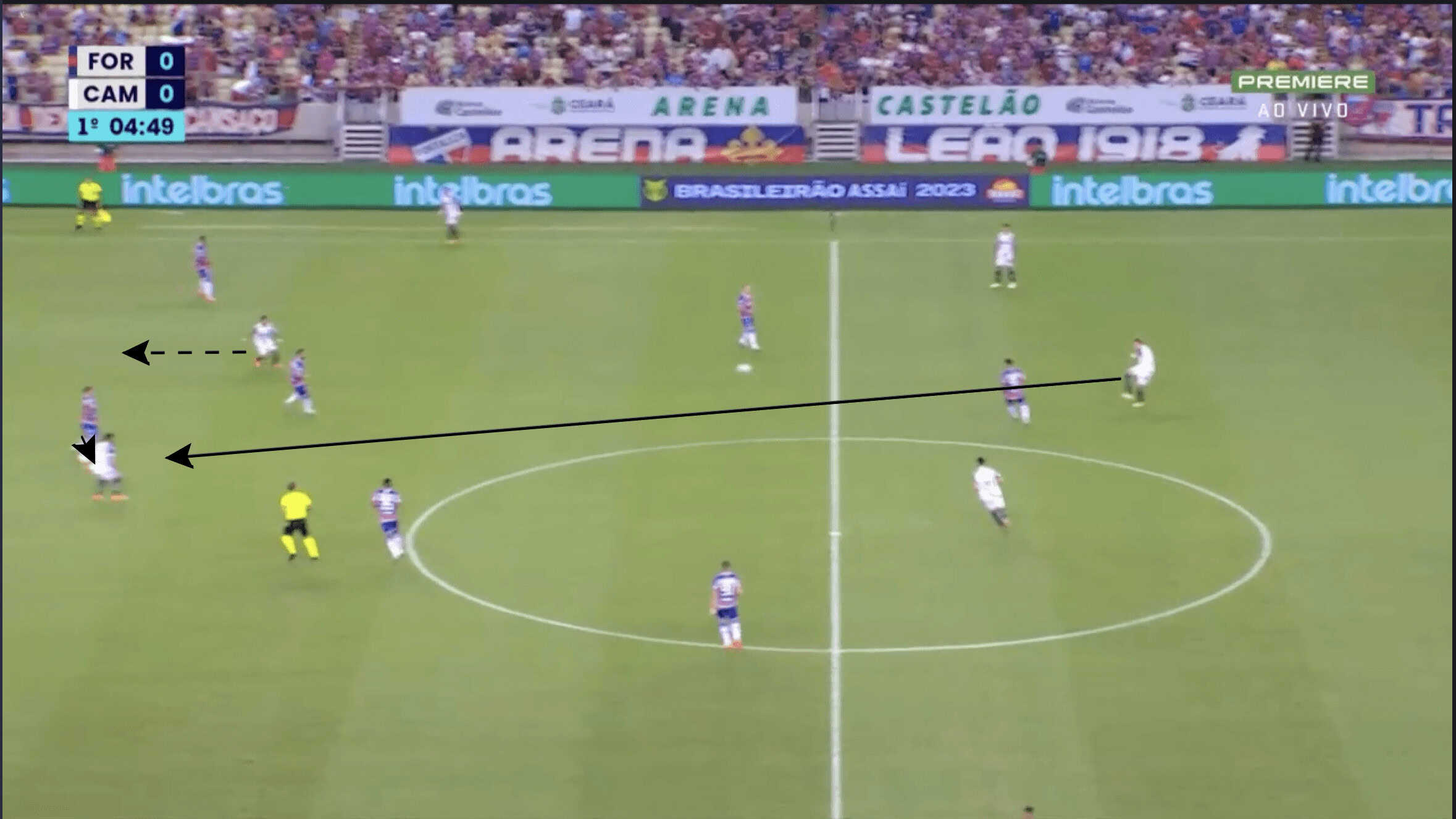

A common theme from this pattern is that the player receiving a pass from Hulk or winning back the second ball then looks to play the ball to the winger on the far side, as can be seen in the example below, with Hyoran playing a pass to the former Bundesliga left winger, Paulinho.

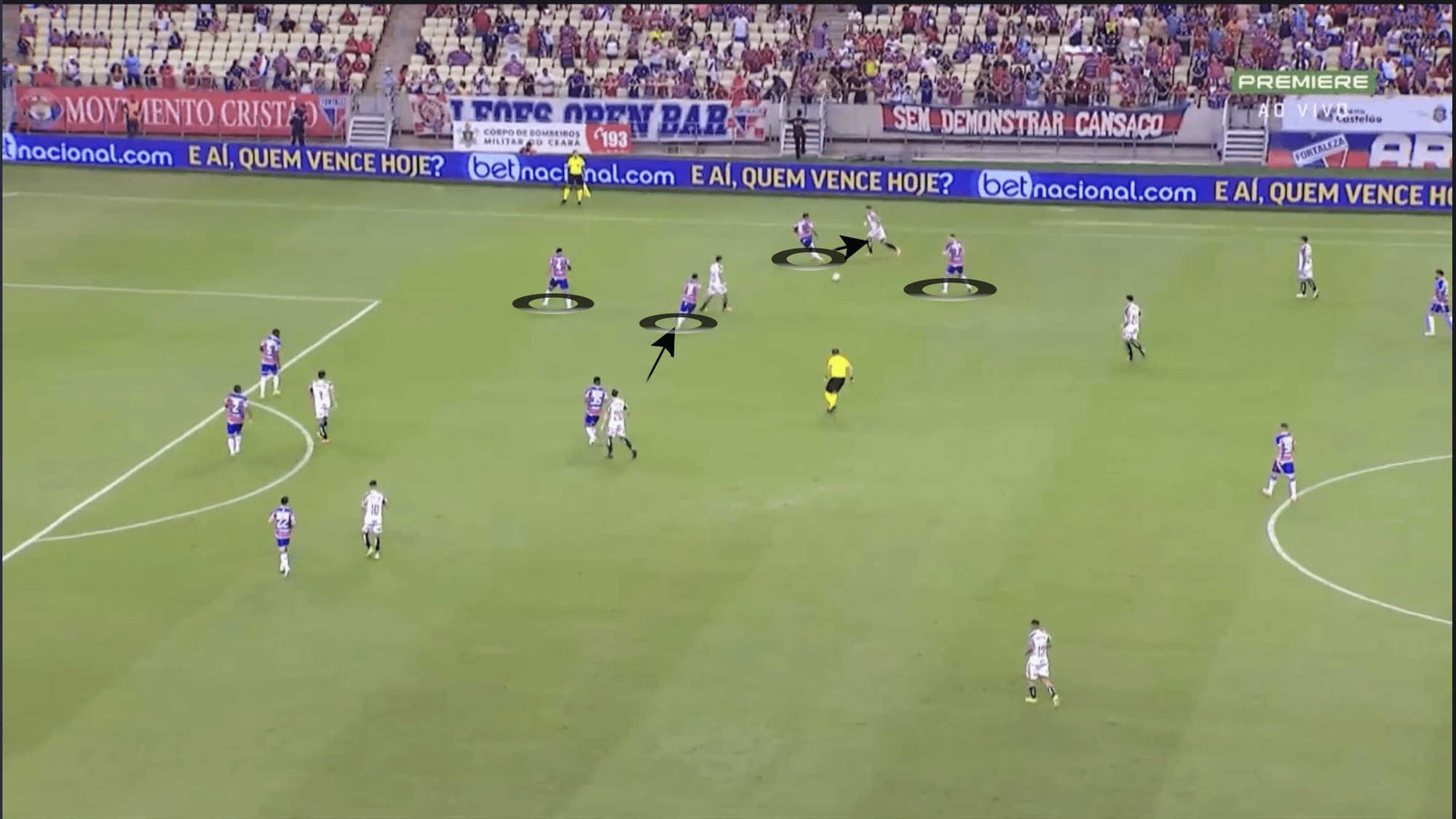

Alternatively, especially in Scolari’s first game against Fortaleza, Atlético Mineiro attempted to progress the ball in the channels. In this particular game, the wingers would drop deeper to provide an additional passing option for the deep full-backs, with the advanced midfielders moving towards the wide areas, again to provide additional support. An example of this can be seen in the image below.

Atlético Mineiro’s advanced midfielders are particularly crucial in the opposition’s half, with the two players advancing further forward to try and overload the opposition’s last line of defence. In the example below, Hyoran and Zaracho begin to advance, creating a 3v2 against the opposition centre-backs.

The advanced midfielders tend to make these runs when the full-backs have the ball deep and wide, with this positioning from the wing-backs creating a helpful angle for crosses. When the full-backs are in more advanced areas, one of the advanced midfielders will drop deeper in order to support them. This can be seen in the example below.

With the full-backs in high positions and an advanced midfielder dropping, an additional aspect that can be observed is a “drop & run” pattern. In the example below, the right-back, Mariano Filho, has the ball in a relatively high area. From this position, Zaracho, who initially attacked the last line of defence, looks to drop deeper in order to provide support for the full-back. In doing so, he pulls the opposition player with him, which creates space behind the opposition’s backline. From this position, Pavon looks to make a run forward to exploit this space, with Mariano playing the ball to the Argentine.

So where’s it all going wrong in attack?

As previously mentioned, Atlético Mineiro have relied on long balls as their primary means of progression under Scolari, with this direct approach also used in the opposition half. The weaknesses attached to this are rather obvious. Despite Hulk’s strength and excellent first touch, there are no guarantees that he will always be able to win the ball. With the positioning of the advanced midfielders as well as the winger, the side is equipped to contest for second balls quickly, but even this is not an aspect that can be relied upon to progress the ball consistently.

A more significant area of concern for the side lies in the wide areas, particularly in the opposition’s half. Throughout the last few games, Scolari’s side have struggled to advance the ball through the wide areas or even access the wide areas. Due to the position of their advanced midfielders, players in the wide areas are often outnumbered by the opposition. In the example below, Pavon, the winger, only has the support of Mariano behind him, with Zaracho and Hulk both in advanced central positions. This creates an easy scenario for the opposition to defend against, with Fluminense virtually having a 4v1 in the wide area.

An additional aspect that stifles progression in the opposition’s half is the depth of the full-backs, particularly the lack of dynamic action of the full-backs, which may be made worse due to their depth. The example below once again shows Atlético Mineiro outnumbered in the wide areas. Moments before, Renzo Saravia, the right-back, played the ball to Pavon. However, upon doing so, Saravia would stay in his position rather than provide overlapping or underlapping support.

These types of actions from full-backs lead to disruption in the opposition’s defensive lines by creating more than one threat in an attacking scenario aiding in reducing opposition cover. The defenders would have to decide whether to cover the player on the ball or the player making the run.

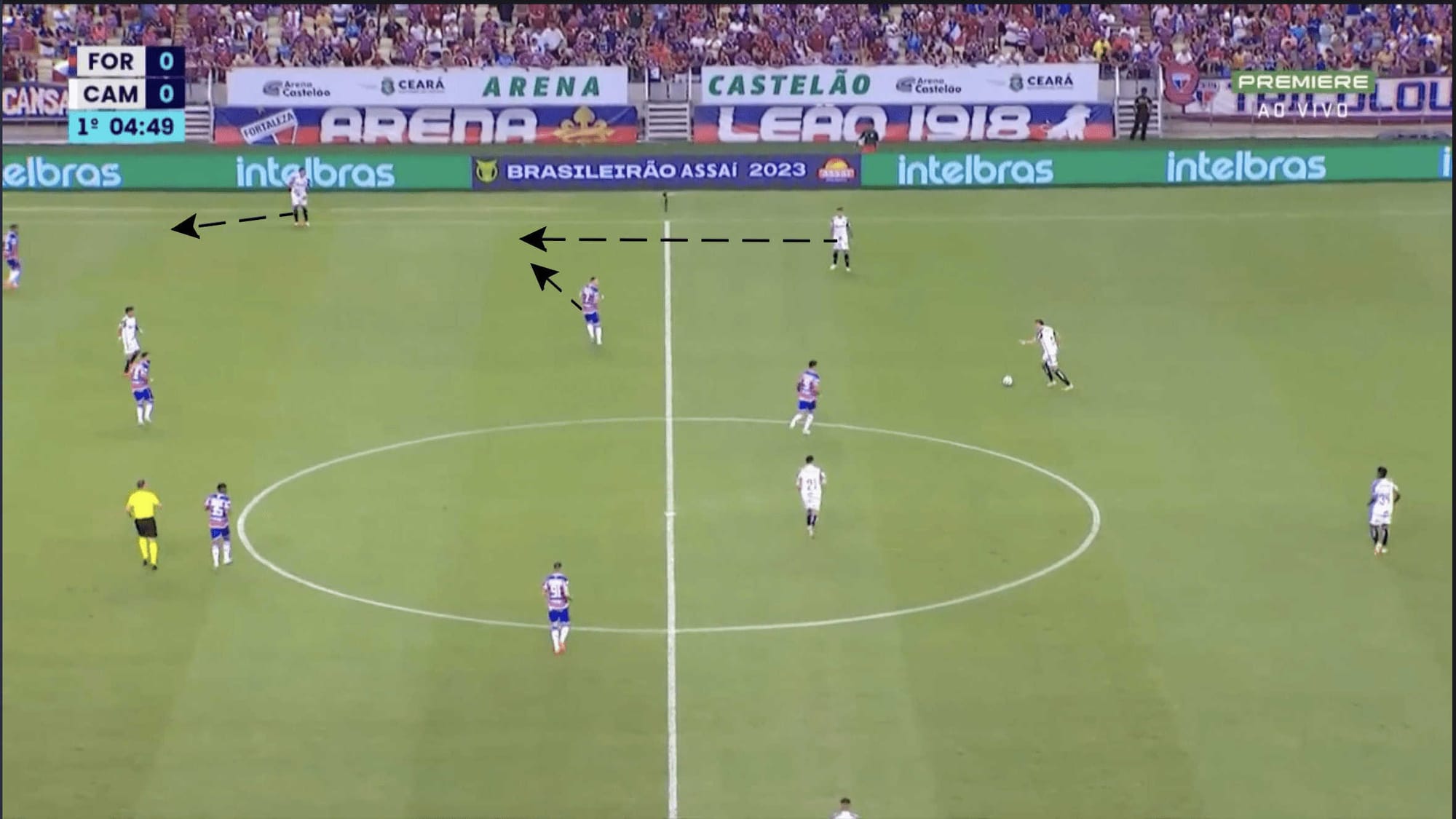

The Fortaleza game provides an example of a game in which the side have struggled to even access the wide areas. In this instance, Fortazela defended in a 4-4-2, with the ball-far second striker adjusting his position in order to cover Battaglia and the other striker shifting towards the wide areas; this can be seen in the image below.

This was particularly effective for Fortaleza, as with the two strikers covering Battaglia, none of their midfielders were forced to advance further forward to cover Atlético Mineiro’s pivot. This ultimately allowed them to keep the centre compact and meant that the midfield line of their defence could shift quickly to cover the wide areas.

As a result of this, Atlético Mineiro would circulate the ball at the back for long periods of time and started to play vertical passes to players in more advanced positions. However, in order for vertical passes to be effective for ball progression, the structure and positioning of a side need to be directed towards giving the recipient of the pass passing option.

As can be seen in the example below, after a pass is played to Hulk, there are no players for him to play the ball to, with both advanced midfielders in more advanced positions than he is. As a result, after Hulk received the pass, the side were unable to keep possession.

In these scenarios where the opposition are not particularly aggressive in pressing the centre-backs, Atlético Mineiro’s deep full-backs once again prevent them from being able to destabilise the opposition’s defence. Below, moments before the previous example, the deep position of Saravia, the right-back, can be seen.

This position creates a comfortable scenario for the opposition left-winger, as the right-back is positioned directly in front of him, with his teammates in good positions to cover the other Atlético Mineiro players. If Saravia were to advance further behind the opposition player, the task of the opposition winger would become less straightforward.

The opposition winger would have to decide whether to drop deeper in order to cover Saravia, which would give the centre-back more time and space to move forward with the ball. Alternatively, if the winger were to stay in his position, Atlético Mineiro would be able to create a 2v1 against the opposition full-back.

Conclusion

Ultimately, from a possession standpoint, Scolari has had a stuttering start at Atletico Mineiro. Although, at times, the side are able to combine well in wide areas, and from layoffs from long balls, these combinations do not occur consistently enough.

As the season is fully underway, it will be challenging to create the right foundations to address structural issues and the actions that players execute in this system. As this analysis has shown, Scolari will have to draw upon his wealth of experience to try and ensure that the side begins to operate with cohesion.

Comments