For some time now, Barcelona have boasted one of the world’s most feared attacks. From 2011 when Pedro, Lionel Messi and David Villa lined up together, to the famous MSN combination of Messi, Luis Suárez and Neymar right through to the modern day, with Messi, Suárez and Antoine Griezmann,

Barcelona tactical evolution through this time has been substantial. From the glory days of tiki-taka under Pep Guardiola, through to the more pragmatic approaches preferred by his successors, as this analysis will prove by considering how the front line was affected by this transition.

This scout report will provide a tactical analysis of the Barcelona front line as it has evolved, in La Liga, in the Copa del Rey and in the Champions League between 2011 and 2020. It will give an analysis of his tactics within the set-ups of, primarily, Guardiola, Luis Enrique and Ernesto Valverde to show how Barcelona have combined some of the world’s greatest attackers.

Messi-Villa-Pedro

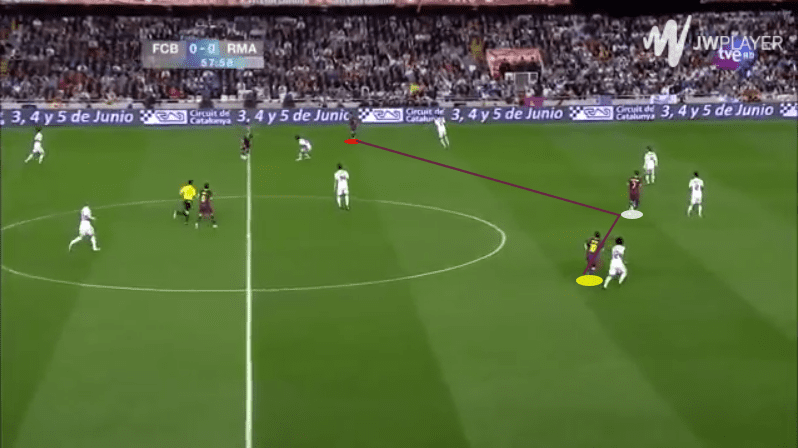

Many argued that the 2010/11 side of Barcelona was the greatest that the club had ever seen. It involved a front three of Messi, Villa and Pedro which was, without any doubt, the most flexible of any of the attacks which Barcelona have had. As can be seen in this example in a Copa del Rey final against Real Madrid, the default position would be to have Messi on the right, Villa through the middle and Pedro on the left. While that was often the line-up drawn out on teamsheets and in newspapers, it was rarely so fixed once the first whistle blew and that flexibility would become a key element to Barcelona’s success and how Guardiola kept baffling opposition defences so regularly.

It is also worth noting quite how heavily Barcelona relied upon width, at least on one flank. This will be one of the greatest changes throughout the decade, but as can be seen here, at almost all times at least one of the front three is hugging the touchline. Midfield runners like Andrés Iniesta would often make runs into the space between the winger and the centre-forward if required, but it would stretch play and help to avoid congestion as possession was retained. It also served to tired and frustrate opposition defences, few more than Jose Mourinho’s Real Madrid.

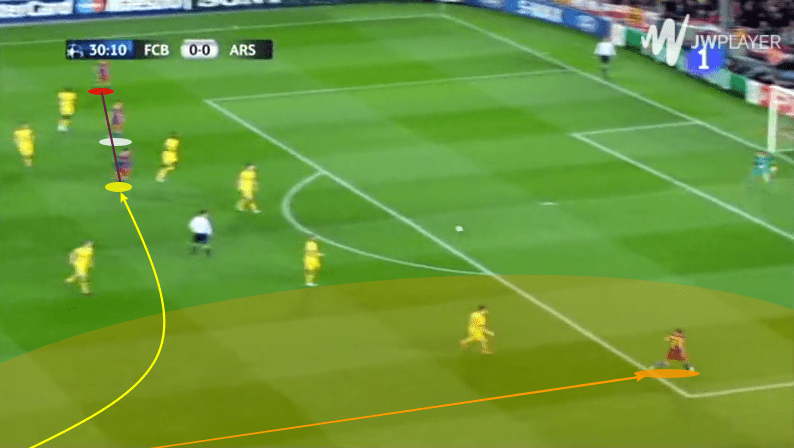

However, in order to fully understand the so-called MVP trident, you cannot ignore the role of Dani Alves at right-back. More of a forward than a defender, the Brazilian would play a crucial role, effectively converting this three-man attack into a four-man attack on almost every occasion. It was almost inevitable that this would happen as Messi became an increasingly central figure as he matured and Guardiola began to give him more freedom, no longer restricted to the right flank. As Messi drifted centrally, he would take at least one, regularly more, defenders with him. That left space for the quick Alves to burst into the open space, as can be seen here against Arsenal. It comes as no surprise with this in mind that only Messi and midfield maestro Xavi registered more assists per 90 minutes than the 0.36 that Alves recorded in all competitions.

Alternatively, it would open up other options. The flexibility of Villa and Pedro meant that they could interchange with any of the front three positions at ease. This allowed Messi to drop into a deeper midfield role, acting as a false nine more than ever before. Rather than leaving the central area vacated, Alves would bomb forwards down the flank, effectively providing a three-man attack with Pedro covering the central area. As such, defences would be left trying to handle a three-man attack whilst keeping an eye on the arrival of Messi coming in from deep having dropped to play the pass which would start the move.

This front three was deadly. In 2010/11 alone, they scored 62 goals in La Liga alone. Only two other clubs, Real Madrid and Valencia, managed more than these three men alone. The flexibility of allowing Villa, Pedro and Messi to drop and switch places, with Alves providing support, was crucial to creating success. Having three well-rounded players, all adept at finishing and creating, even if they lacked the individual talent that may arrive in later years, was essential. Having expelled Zlatan Ibrahimović the previous summer, it was evident that this was what Guardiola had been after. Rather than having a centre-forward to lead the line, he found in Villa a player who could provide a range of options and would bring pace to the attack. A target man was not what was required, rather Guardiola was after a dynamic and versatile front-man.

Messi-Suárez-Neymar

As teams became accustomed to Guardiola’s system, Villa’s form faded and Pedro struggled to maintain the consistency of that season, it became hard to keep up. Tito Villanova and Tata Martino both sought to maintain a similar approach, sticking to the front three with Messi as the main man and incorporating the likes of Alexis Sánchez more regularly, but it was not possible to maintain. By the time Luis Enrique arrived as coach, it was clear that he would take a more practical and direct route. 2014/15 was considered to be when he truly had his ideal front three firing on all cylinders for the first time in the form of Messi, Suárez and Neymar.

Unlike under Guardiola, this front three was more predictable. Neymar would line up on the left, bombing up and down the flank, Suárez would be the central man, looking to be on the last shoulder but occasionally dropping in, and Messi would be given the same free role on the right to drift centrally. This approach may have been easy to anticipate, but many defences simply could not stop it. With the speed of their movement, Barcelona’s attack would often wait until the last moment to make clear their intentions and make the move. As such, defenders could predict one of the options tactically but would be gambling. This led to many sides playing with a tightly packed midfield space to deny space for Messi or Suárez to drop into, affording greater space to the midfield and to the wide men.

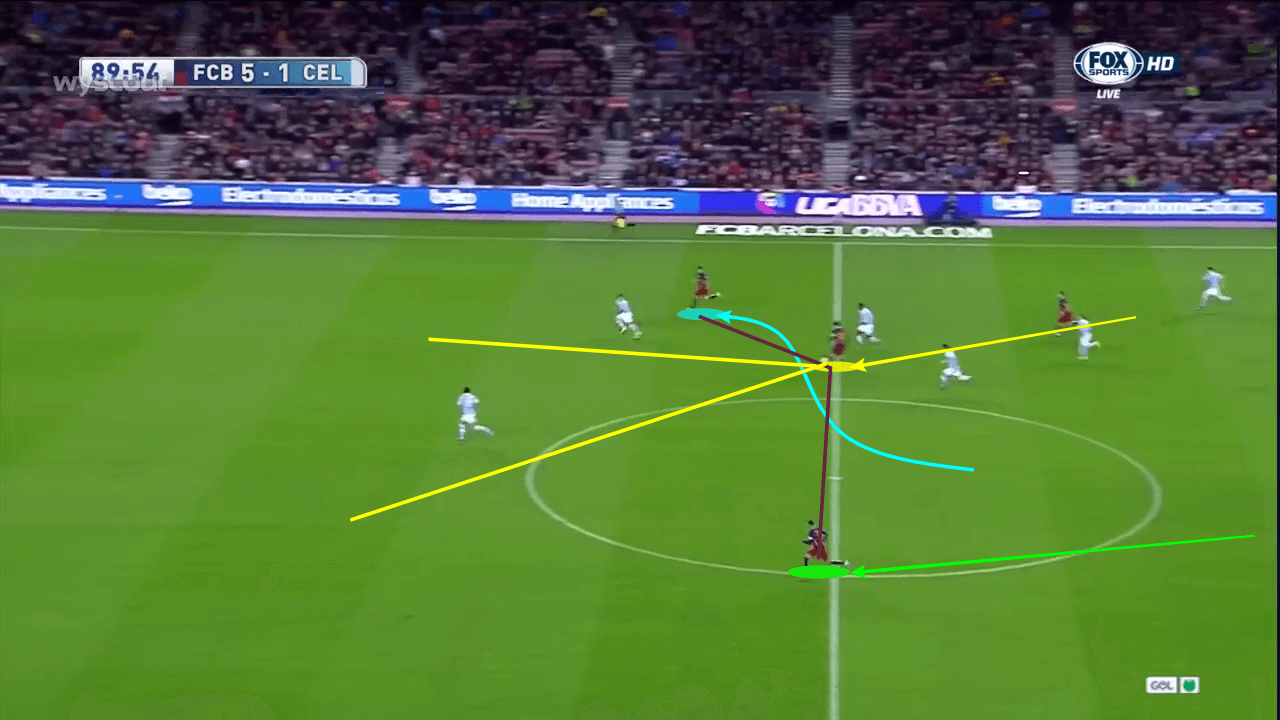

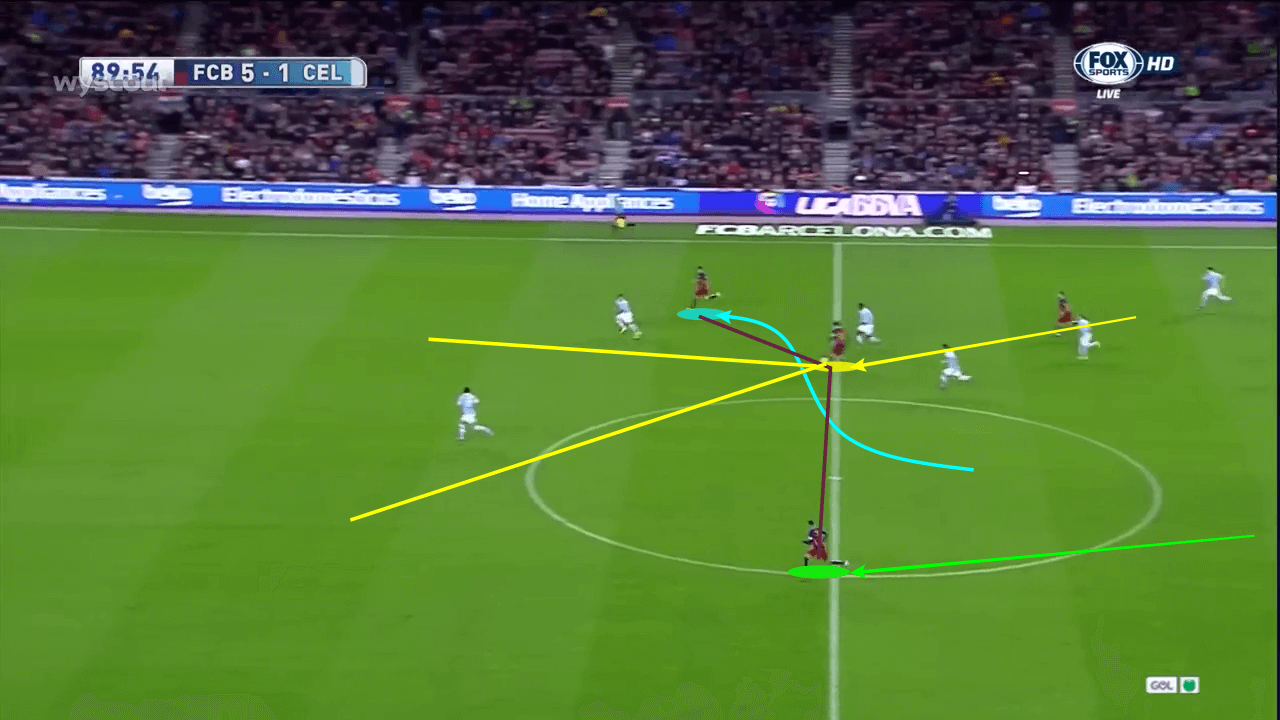

It was not in possession where Luis Enrique made substantial changes though, rather it was on the counter. At 2.98 counter-attacks per match, it was more a matter of being clinical when Barcelona did counter. Almost always, the ball would be given to Messi to carry through the central passage, with Neymar often in an advanced position to pull to the left and stretch the defence with Suárez manoeuvring to the right to do to the same on the opposite flank. The result would be to again force opposing defences to gamble on tracking a runner or stopping Messi. Either option would allow the Argentinian the choice to go forward himself or play in an unmarked team-mate. This example against Celta Vigo reflected just the kind of chance that Barcelona proved to be clinical with throughout the era under Luis Enrique.

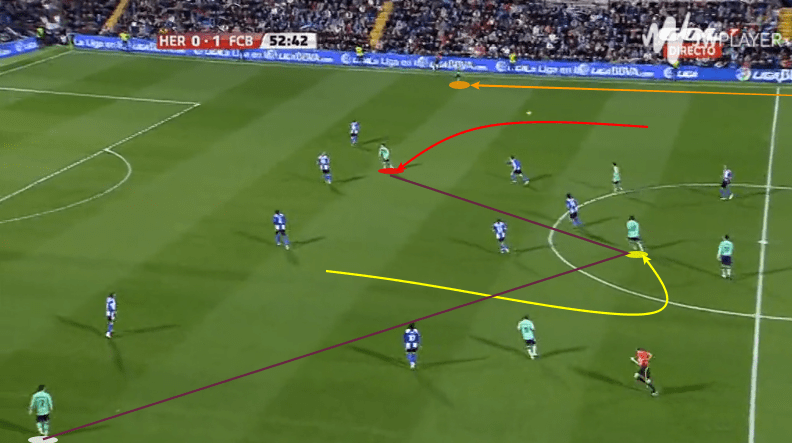

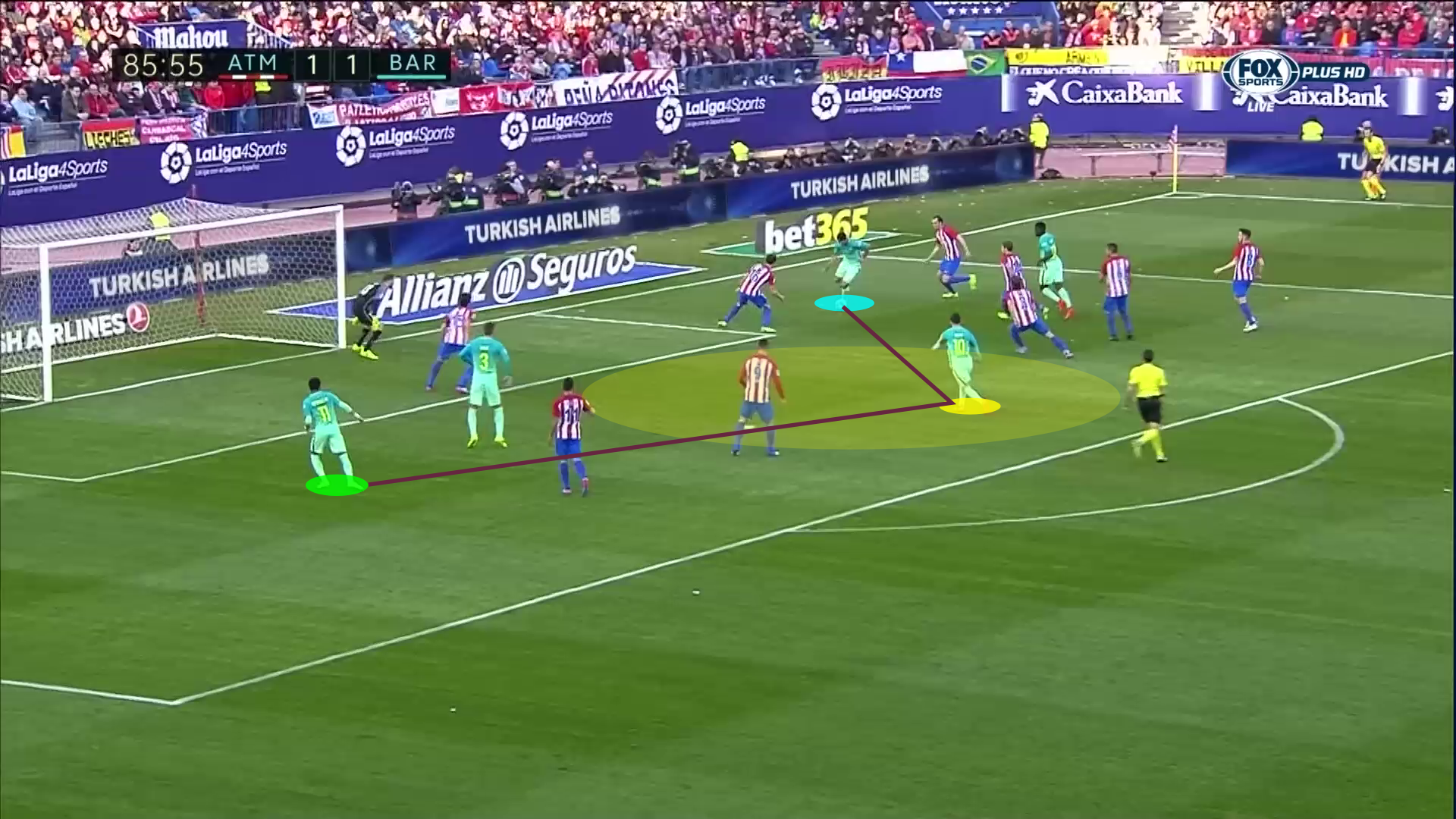

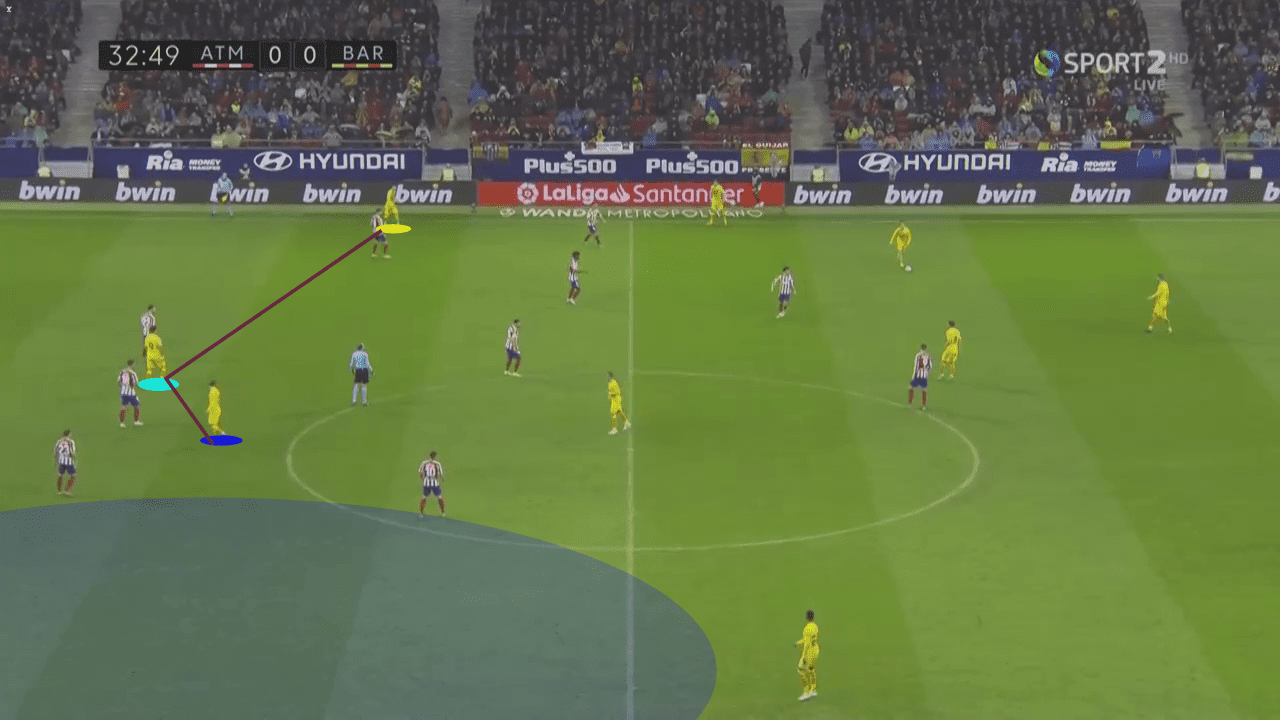

Equally, a mobile and quick Suárez provided the kind of flexibility that had previously been offered by Villa. Whilst the Spaniard was far more mobile and less physical than the Uruguayan, the comparison of the two reflects the change from Guardiola to Enrique. Similar in some ways, but with a whole lot more pragmatism. One such example can be seen here, against Atlético Madrid, where Suárez drifts to the right to collect the ball and allows Messi to arrive late into the box in a central area which has been vacated as Diego Godín tracks Suárez to the wide area and is beaten by his compatriot. With Neymar staying wide on the other side, Messi is not under pressure from defence or midfield. Such moves helped Barcelona to find spaces against even the most compact of defences like this Atlético outfit.

Much like in the previous years, this approach was built around getting the best out of Messi but this time by providing high-quality support around him. In Neymar and Suárez, defenders feared the alternatives just as much as the main man himself. In Neymar, his direct approach, regularly taking players on and looking to beat them, terrified opposition defenders who would be forced into fouling him. In 2015/16, he suffered 34% more fouls than any other player in La Liga.

Width, pace and flexibility. Much like Guardiola’s approach, this side had many similarities, though they added greater physicality and a more direct approach in a compromise for some of the free-flowing movement. With arguably the three greatest forwards on the planet, excluding Cristiano Ronaldo, in one attacking trio, it is easy to see why some believe that it was an even more clinical approach than Guardiola had in his side.

Messi-Suárez-Griezmann

Eventually, Neymar would move on, fed up of not being the main man in a system so clearly built around Messi. Unfortunately for Valverde, he would do so before a ball had even been kicked in competitive action under his management. Seeking to find a replacement for him would go on to curse Valverde’s reign at Camp Nou. The initial replacement was Ousmané Dembélé. The most similar option available, he seemed the most likely to retain that style of a wide man who would attack defences with pace and skill. Injuries afflicted the young Frenchman, and continue to do so, which led to the arrival of Philippe Coutinho. While he had been part of a front three at Liverpool, The Brazilian was nothing like his compatriot. Rather than providing a wide option, he would regularly look to cut inside or shoot from distance, much more an attacking midfielder who would move inside in style than an out-and-out forward who would stay wide.

That left Valverde without a clear identity in attack. Rather than having a clear set-up, as had been the case ever since Guardiola’s appointment, having come through La Masia and used the same 4-3-3 shape as he had played in under Johan Cruyff, Valverde began to mix things up. Without a clear option, he would even sometimes play a 4-4-2 shape to greater accommodate the options available.

One option which worked well for Valverde, particularly in 2018/19 was to use Jordi Alba much in the same way as Guardiola had used Alves. Suárez would play in a much more rigid central role and would occasionally be supported by Philippe Coutinho coming from deep to provide a diagonal run, but Alba would take advantage of Coutinho’s central move to exploit the space on the left flank. Time after time he would cut the ball back once attacking the six-yard box to set up an assist. With 16 assists, it was the best season of his career in that regard and he was also Barcelona’s most prolific crosser with 184 crosses, 3.2 per 90, as Barcelona became a more direct side.

With Coutinho shipped out as a clearly illogical solution, the idea was that the issue would be resolved in the summer of 2019 when Griezmann joined the club. The Frenchman arrived from Atlético Madrid with plenty of question marks. Whilst he was more of a forward than Coutinho had been, he was not a wideman like Neymar had been. Again, it pointed to a change in approach from Valverde, yet it is one which remains to be without a clear plan.

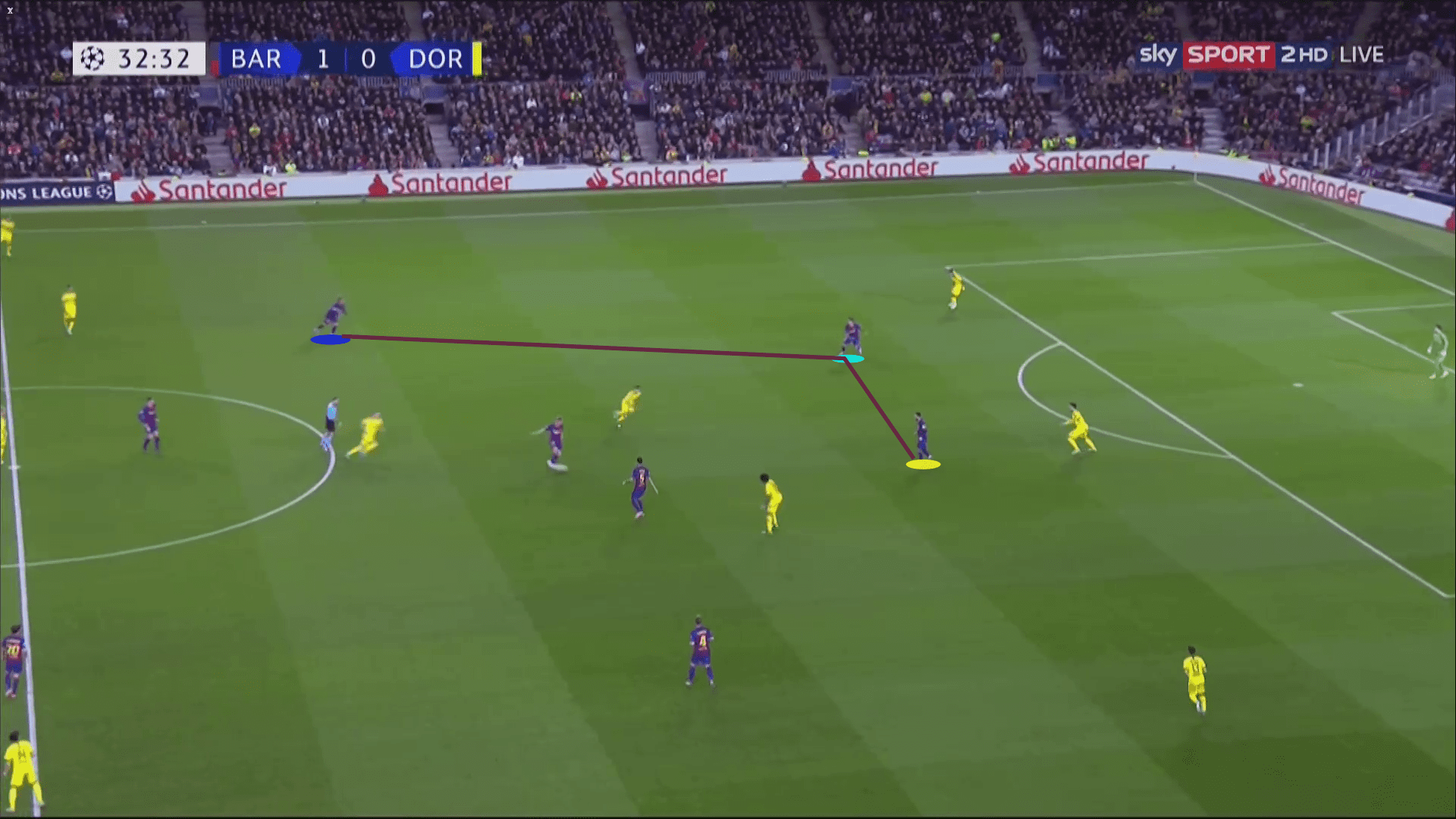

The coach would regularly line up with Griezmann as more of a midfield option, offering defensive stability and benefitting from his workhorse attitude picked up under Diego Simeone. The drawback of this was that it left Barcelona’s attack with many of the same issues that they had encountered with Coutinho in the role. As can be seen in this example against Borussia Dortmund, Messi and Suárez are left almost alone in attack, with the Frenchman entirely disconnected from play. In complete contrast to the rapid and clearly co-ordinated counter-attacks of the Luis Enrique era, the pace had been slowed down and there was less movement.

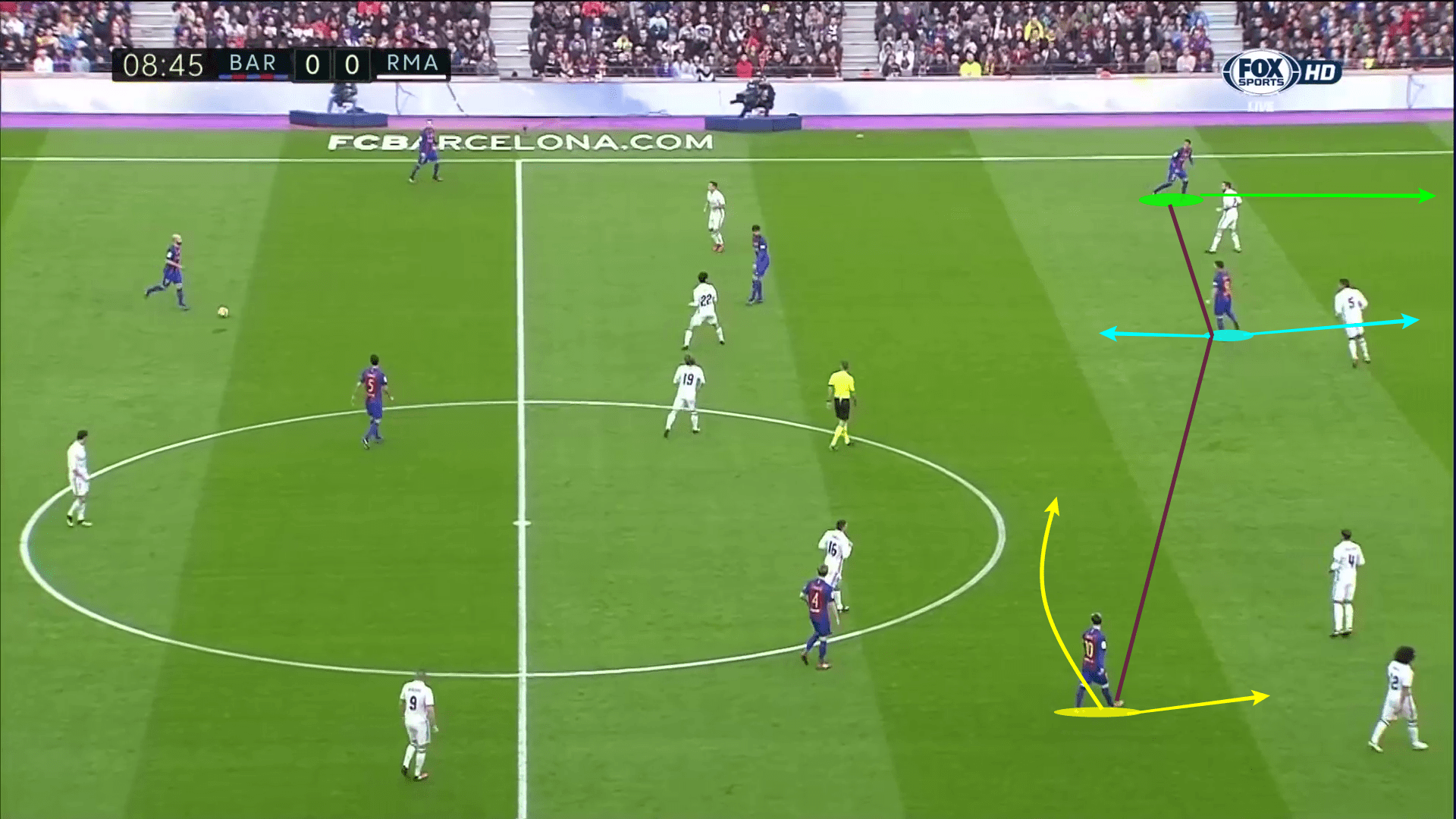

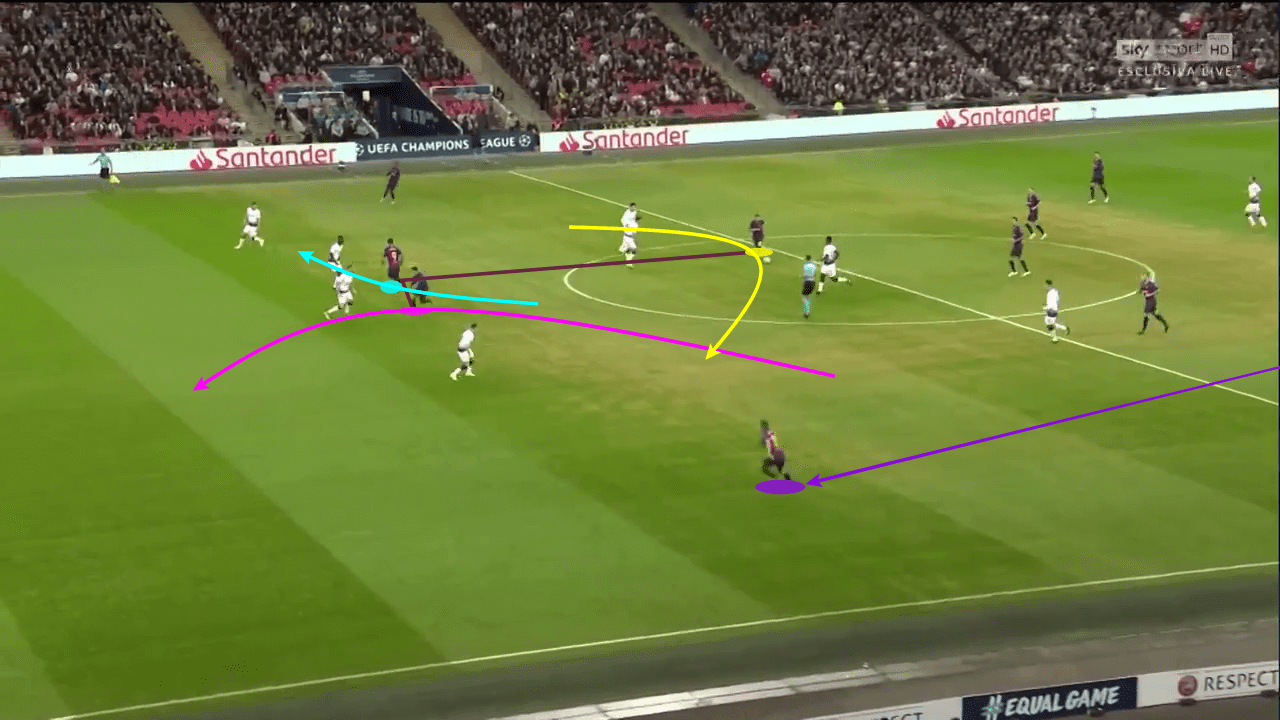

Equally, Griezmann is often guilty of drifting centrally. As time goes by, Suárez and Messi have both become less mobile and prefer to occupy those central areas which have become increasingly congested. Yet when Griezmann does so too, he is merely serving to add to that congestion and slow play down even more. Doing so allows teams to defend more narrowly and reduce the options for Barcelona, who no longer have the width to find holes in between opposition defenders as neither Griezmann nor Messi are on the touchline. Even if one is, as is the case below, it can be easily cancelled out by a structured defensive and midfield set-up.

There is no greater demonstration of the change than in the dribbling statistics. In Neymar’s final campaign, he registered 14.24 dribbles per game. Griezmann this season has recorded 1.59. The direct style and width that made Barcelona so deadly has disappeared and instead been replaced by a congester and snail pace attack which struggles to break down opposition defences. As Suárez and Griezmann continue to tread on each other’s toes, it is evident that one must make way. Under Quique Setién, his passing style of play is simply too easy to defend against by having such a narrow attack which allows teams to defend narrowly.

Conclusion

Barcelona are clearly adamant to stick to their shape of 4-3-3 which has been passed through the generations ever since the age of Cruyff’s Dream Team. Both Guardiola and Luis Enrique enacted it with their own touches, but neither Valverde nor Setién have yet perfected it. As ley personnel loose mobility and pace, the signing of Dembélé looked, on paper, to be the ideal match to replace Neymar. The decision to bring in Griezmann in his place after a disappointing first two seasons at the club made far less sense. Equally, Suárez increasingly resembles Ibrahimović in his physical style with little pace, a player binned by Guardiola for not fitting into the system.

Lacking all of the width, flexibility and pace which has defined Barcelona for much of the 2010s, the 2020s arrive with an intriguing challenge for Barcelona: to bring in the players for their system or to change approach. In the likes of pacey left-winger Ansu Fati, there are options available but Setién does not appear convinced. Much like those before him, he will hope to have time to build his own approach, as after all neither Guardiola nor Luis Enrique got their attack firing prolifically in their debut season. Time will be required, but the role of an ageing Messi and a decision on what Suárez can contribute should be priorities as Barcelona look to plan for the future.

Comments