Centre-back is a position that has undergone immense tactical development throughout the history of the game.

Reportedly first used by Brazil in the 1950s, moulded in Italy, conventionalised in England and modernised in Spain, centre-back is still one of the most vital positions on the football pitch but has evolved to keep pace with the tactical evolution of the sport.

Formerly categorised as being ‘hard as nails’ and being solely on the pitch to defend and boot the ball long, central defenders have now become tempo-setters. Just look at Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton and Hove Albion, for instance.

Where midfielders always set the tempo and made their teams tick, it has become commonplace to see centre-backs performing these duties in certain possession-oriented teams. They are now the ones tasked with breaking the lines, picking the right time to progress forward and slowing the game down when necessary.

Apart from De Zerbi and Pep Guardiola to an extent, Xabi Alonso is a manager that relies heavily on his centre-backs in his game model at Bayer Leverkusen. In fact, the Spaniard has found several intriguing ways to utilise his central defenders in all phases of the game.

This tactical analysis piece will be a team scout report looking at how Alonso deploys his centre-backs in his tactics in the build-up phase, higher up the pitch and during defensive transitions.

Build-up phase

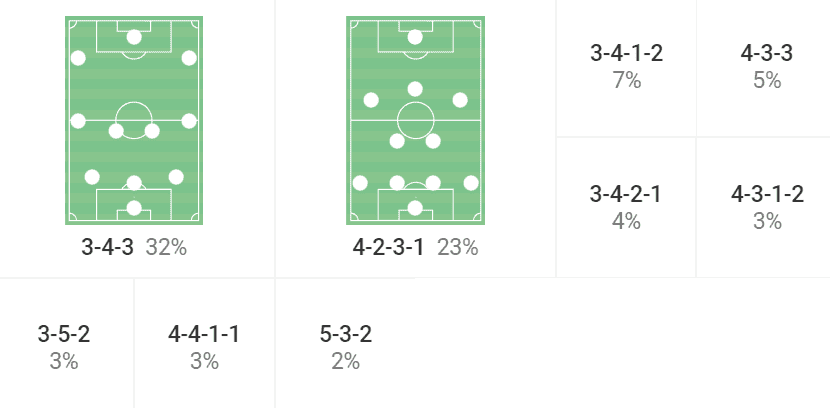

Before getting into the nitty and gritty analysis of Alonso’s central defenders, it is important to note his formation preference as a back four uses two centre-backs and a back three comprises of, well, three.

While in the early days of his tenure at the BayArena, the former Real Madrid and Liverpool midfield anchor preferred to line his players up in a 4-2-3-1.

The last time the young head coach opted to go with the formation that he saw such great success in during his playing career was in a 3-2 home defeat to Mainz back in February. From that day forward, Leverkusen have always started with either a 3-4-1-2 or a 3-4-2-1, depending on the positioning of the front three.

In fact, the Bundesliga club are unbeaten in all competitions since the loss to Bo Svensson’s Mainz and are now in the semi-final of the UEFA Europa League.

The three centre-backs have primarily been Odilon Kossounou on the right, Jonathan Tah in the middle and Edmond Tapsoba or Piero Hincapié on the left. Tapsoba can also play as a right centre-back when called upon due to being naturally right-footed.

Ultimately, Alonso employs a back three with players who are all comfortable receiving possession of the ball under pressure. However, in the build-up phase, the head coach takes a few pages from Antonio Conte’s playbook for how to play out with three centre-backs.

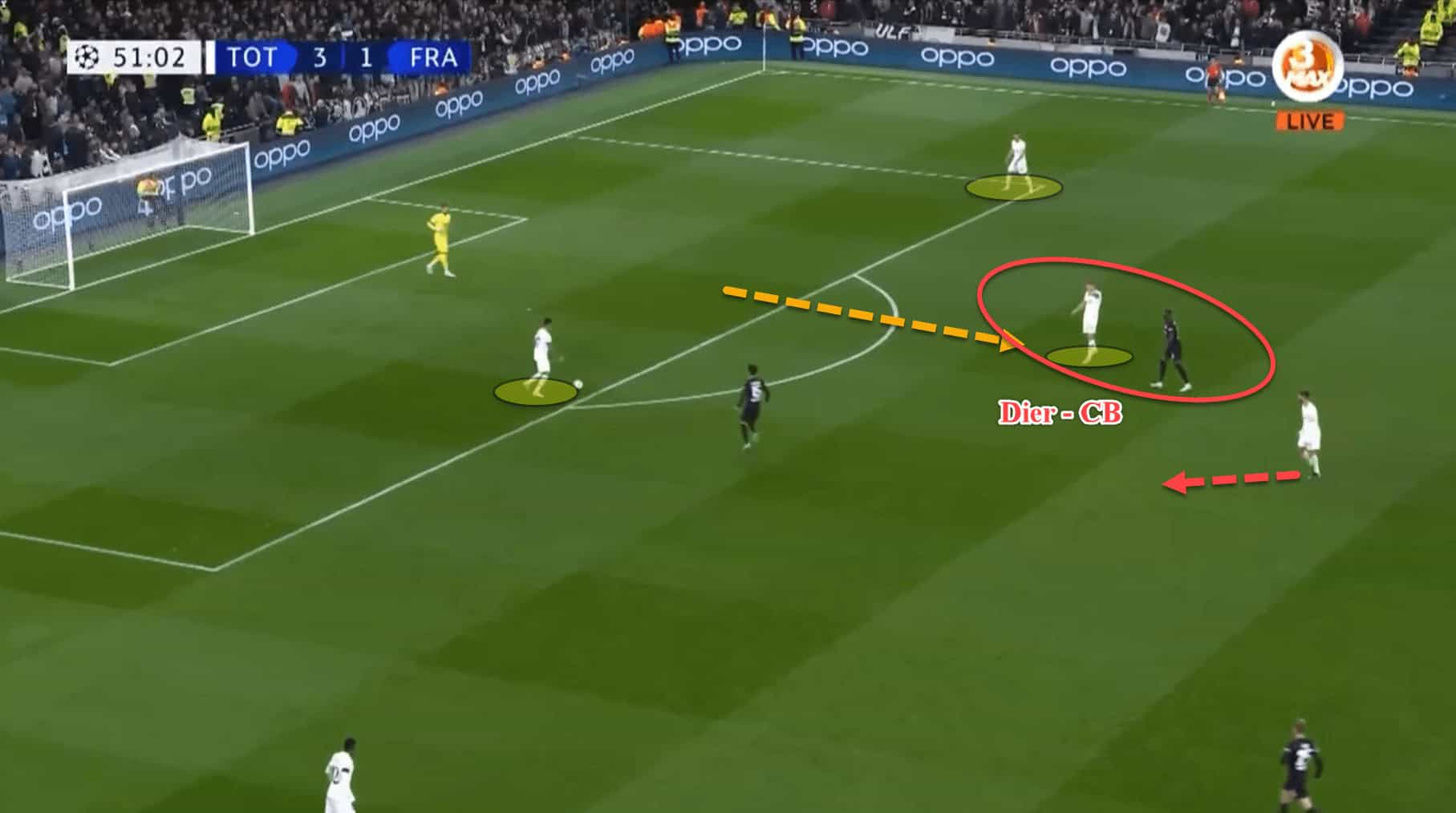

At Tottenham Hotspur, Conte would use Eric Dier in quite an unconventional role for a central defender. Some even labelled the England international’s role as that of an old-school ‘half-back’.

As shown in the previous screenshot, Dier would position himself beyond the opposition’s first line of pressure. The reason for doing this was so that he could attract one of the forwards to press or mark him, taking this player out of the press.

Furthermore, it meant that another player could drop into this area and receive the ball from the backline as the pressor was essentially being ‘pinned’ by Dier’s positioning.

Dier was also comfortable receiving possession of the ball if the goalkeeper or the remaining centre-backs opted to play it to him but getting the ball to him wasn’t a necessity. His job was to pin one of the forwards to create time and space for a teammate to get on the ball behind the first line.

This does require a lot of technical ability from the centre-back but also requires immense faith from the coaching staff. Instead, managers typically instruct their back five to build up play in a back four while one wingback advances forward.

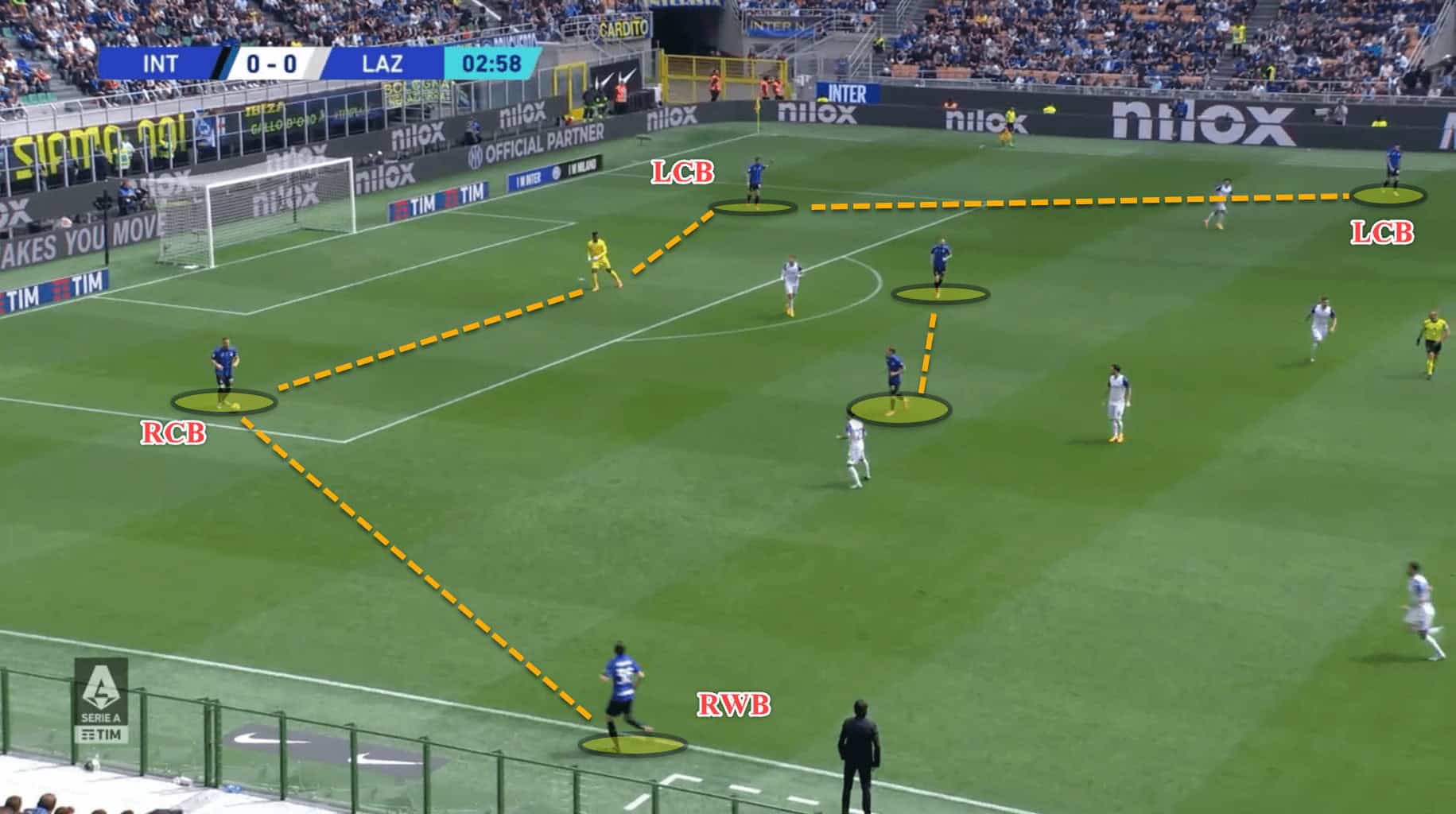

Here is an example of Internazionale playing out from the back during their recent 3-1 victory over Lazio. The left centre-back, Alessandro Bastoni, has pushed up to become an auxiliary left-back while the left wingback has advanced forward on the same flank to facilitate this.

The right centre-back and central defender have split wide of the goalkeeper and the right wingback, Matteo Darmian, has dropped to be in line with the two deepest midfielders. In essence, Inter’s shape during build-up in this instance was a 4-2 structure.

Nevertheless, Alonso has adopted both methods for building out from the first third with a back three.

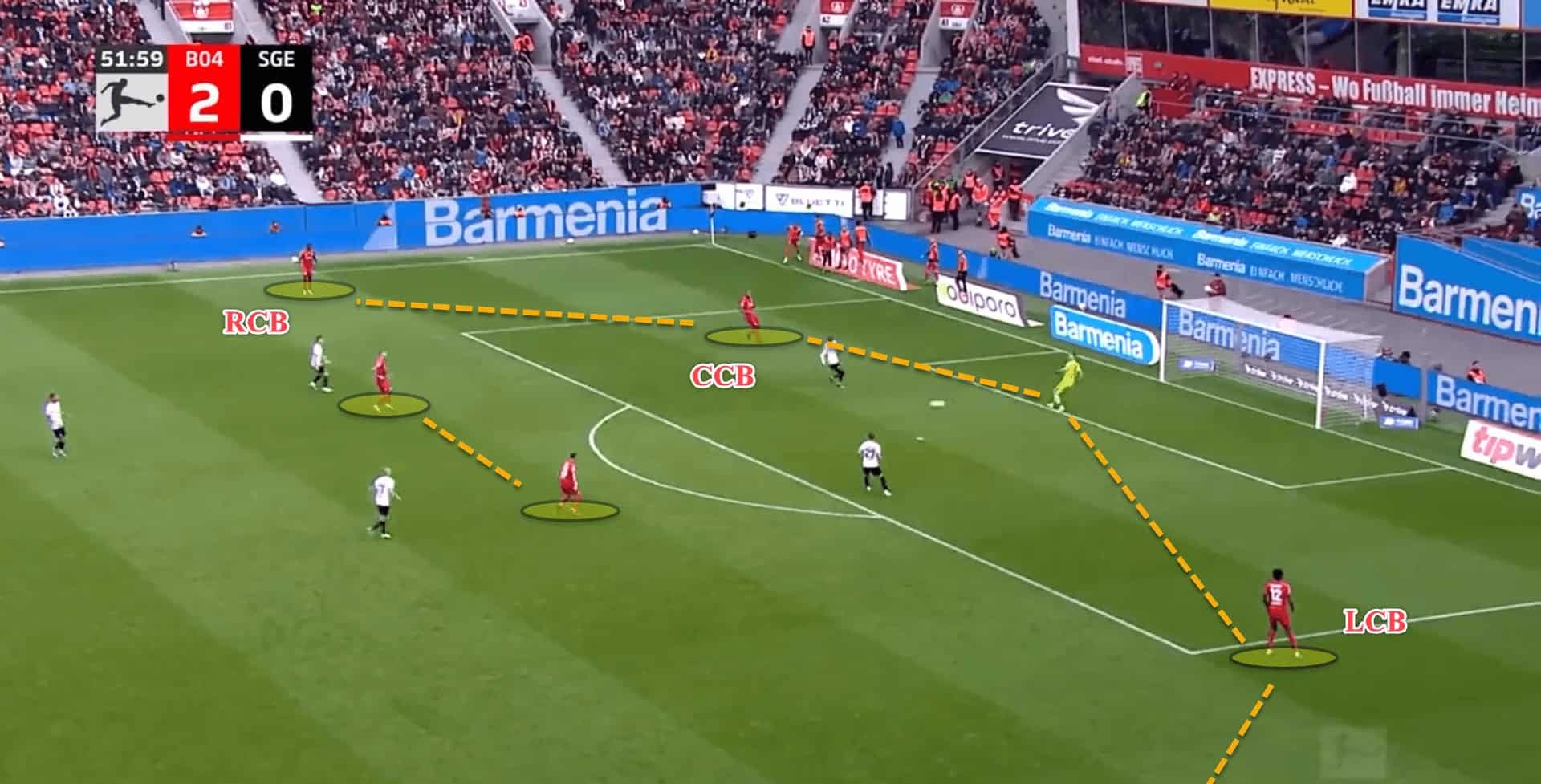

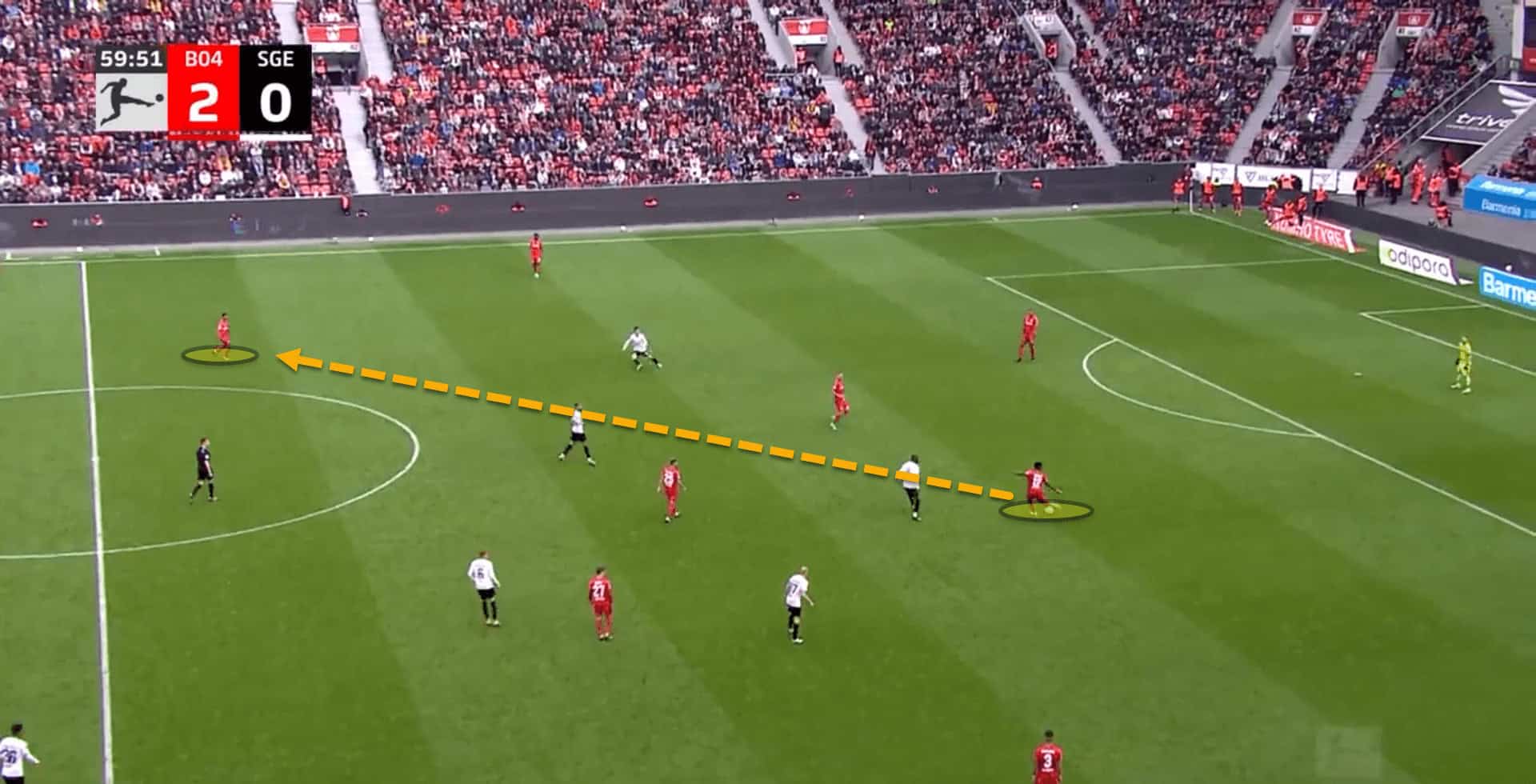

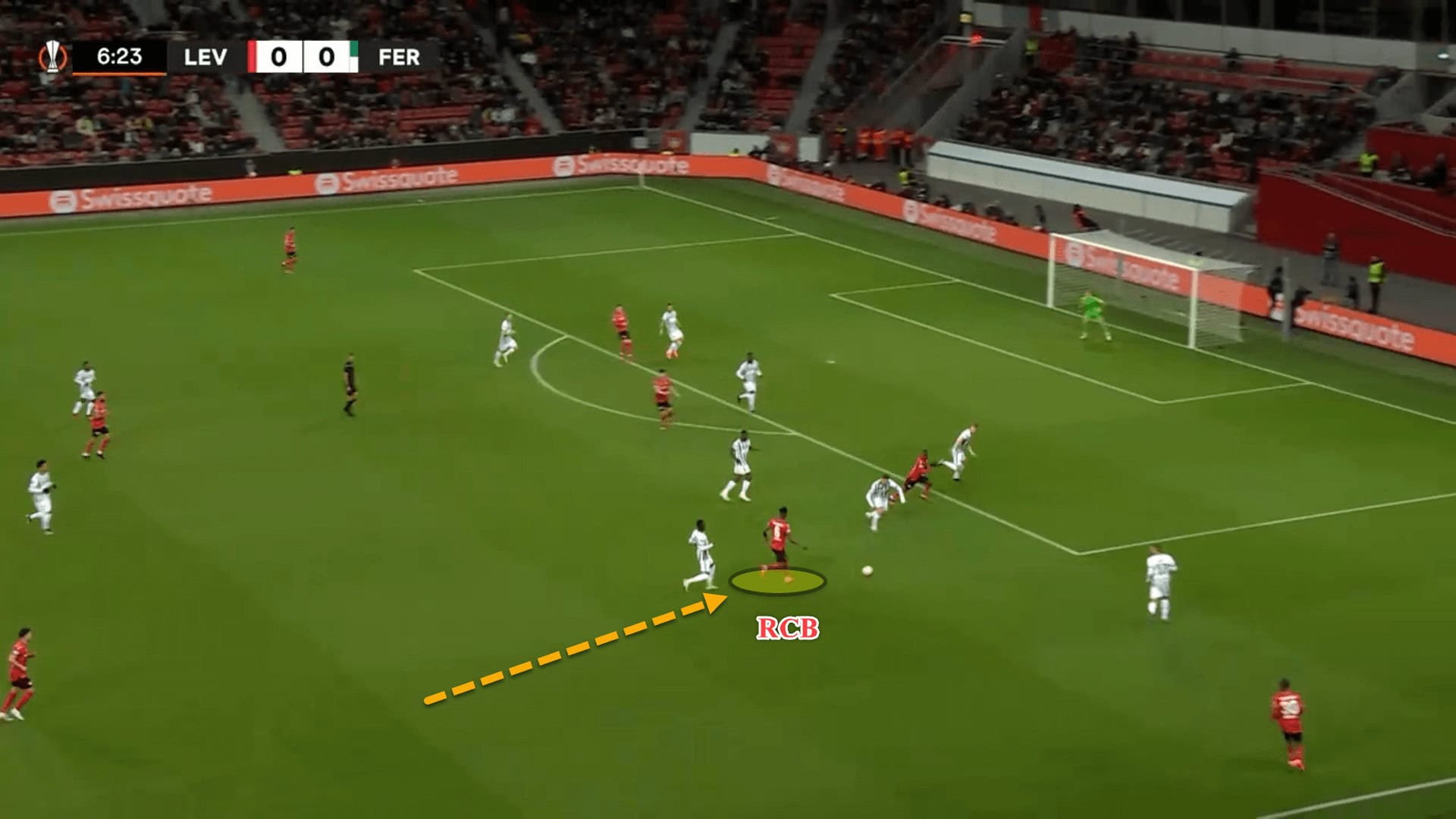

In this scenario, against Eintracht Frankfurt’s high block, Leverkusen set up in a 4-2 structure with the right centre-back, Kossounou, becoming a temporary right-back. Tah and Tapsoba split the goalkeeper, Hincapie dropped in as a left-back while right wingback Jeremie Frimpong pushed way up the pitch to allow Kossounou to position himself out wide.

Then, the double-pivot screened behind the opposition’s first line of pressure, looking to receive the ball to feet to eventually progress forward.

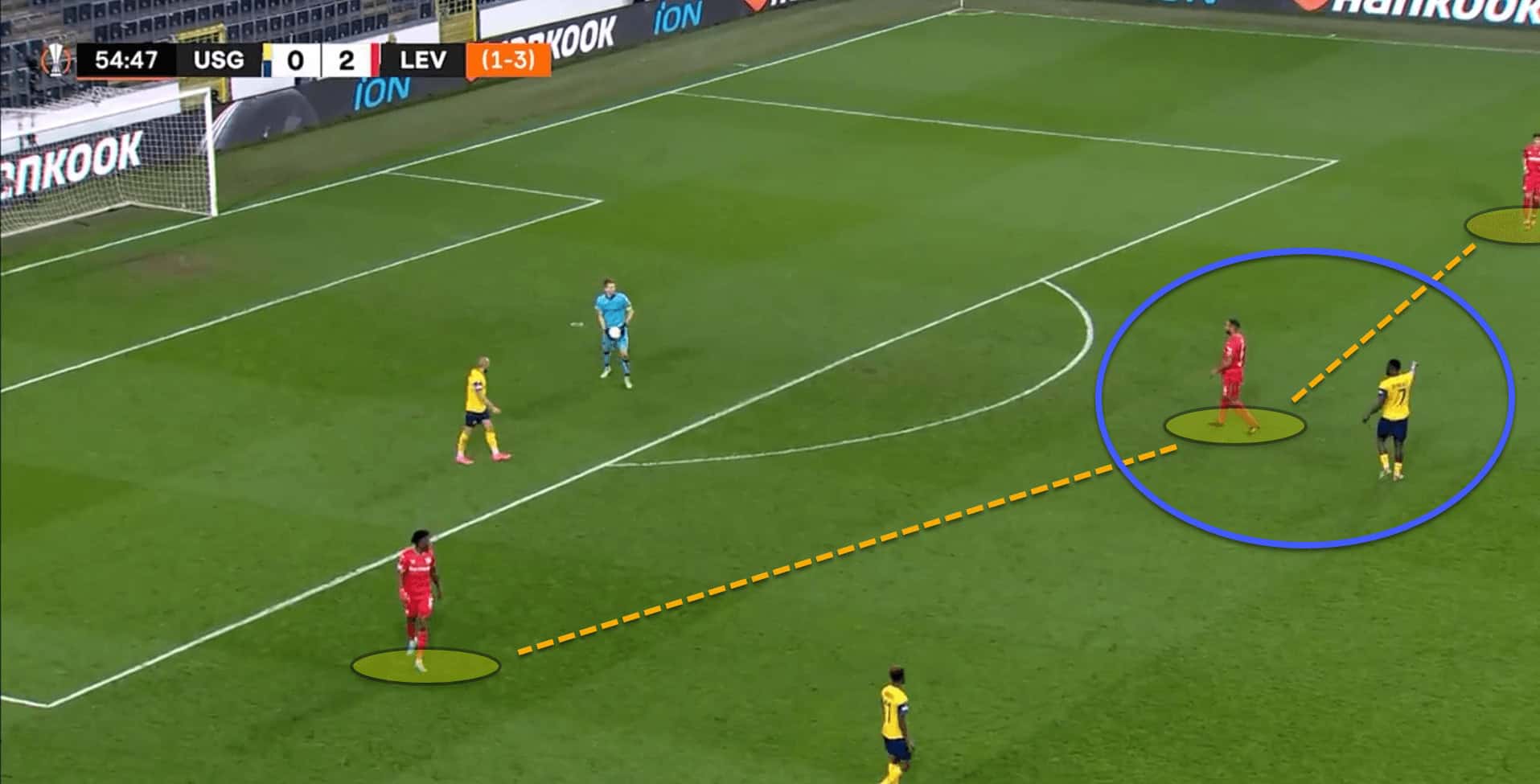

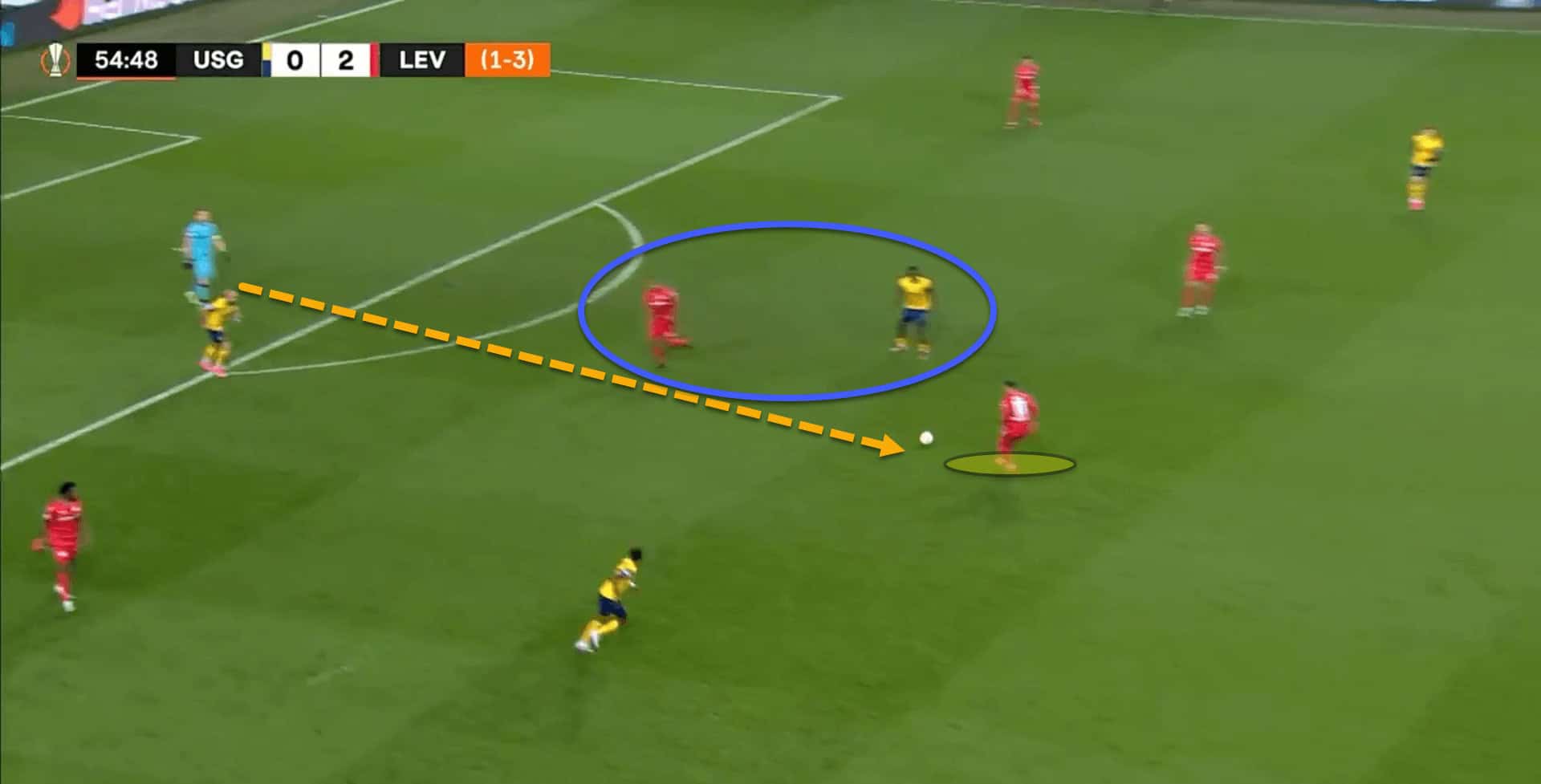

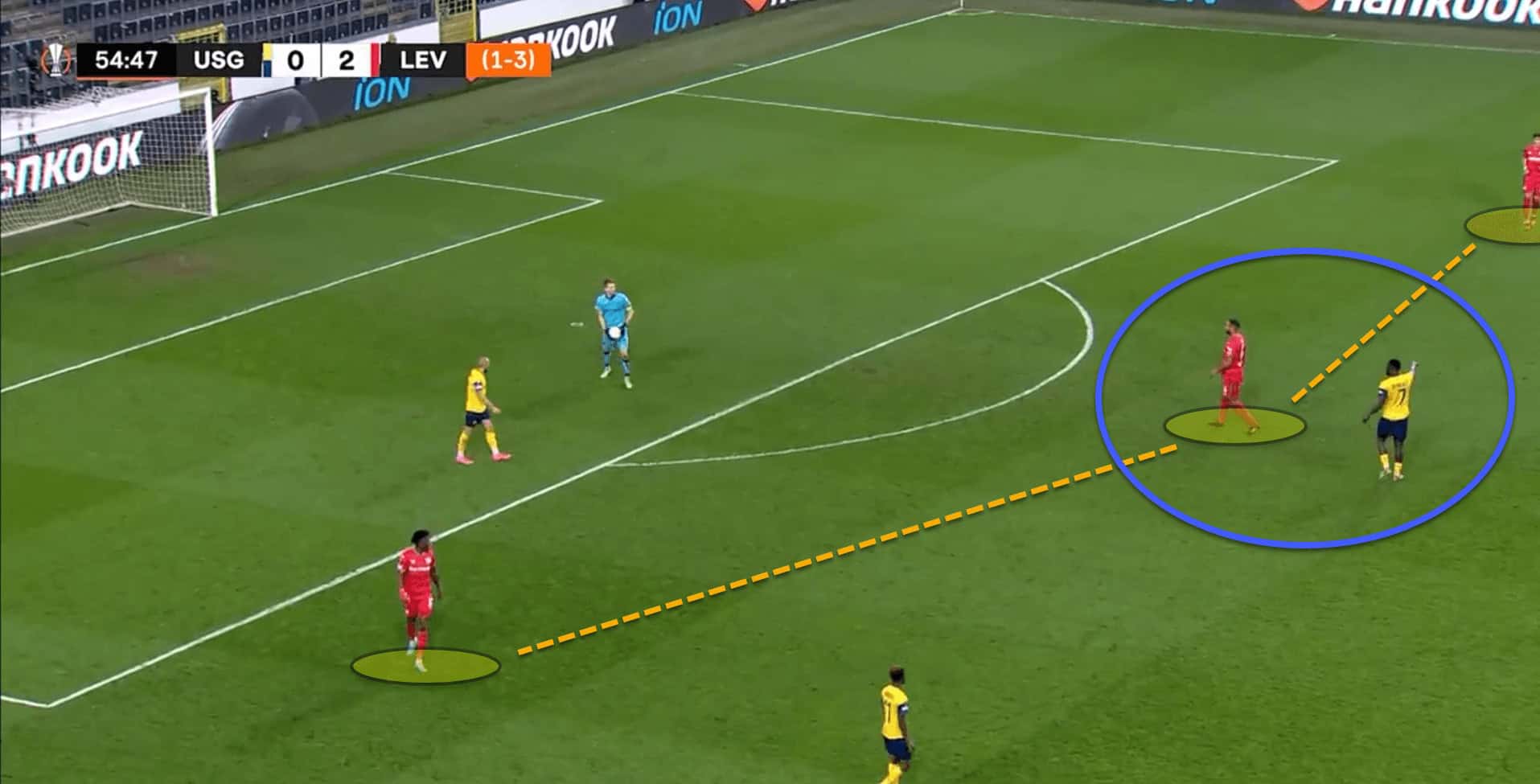

Less than two weeks later, in a European tie versus Belgian club Royale Union Saint-Gilloise, Tah constantly pushed up beyond the opposition’s first line to pin one of the pressing forwards.

Because of Tah’s nonchalant positioning taking one of USG’s pressors out of the game, the goalkeeper was able to roll the ball to the feet of the Leverkusen pivot who was under no pressure. The Bundesliga giants progressed from the back through a high press with ease.

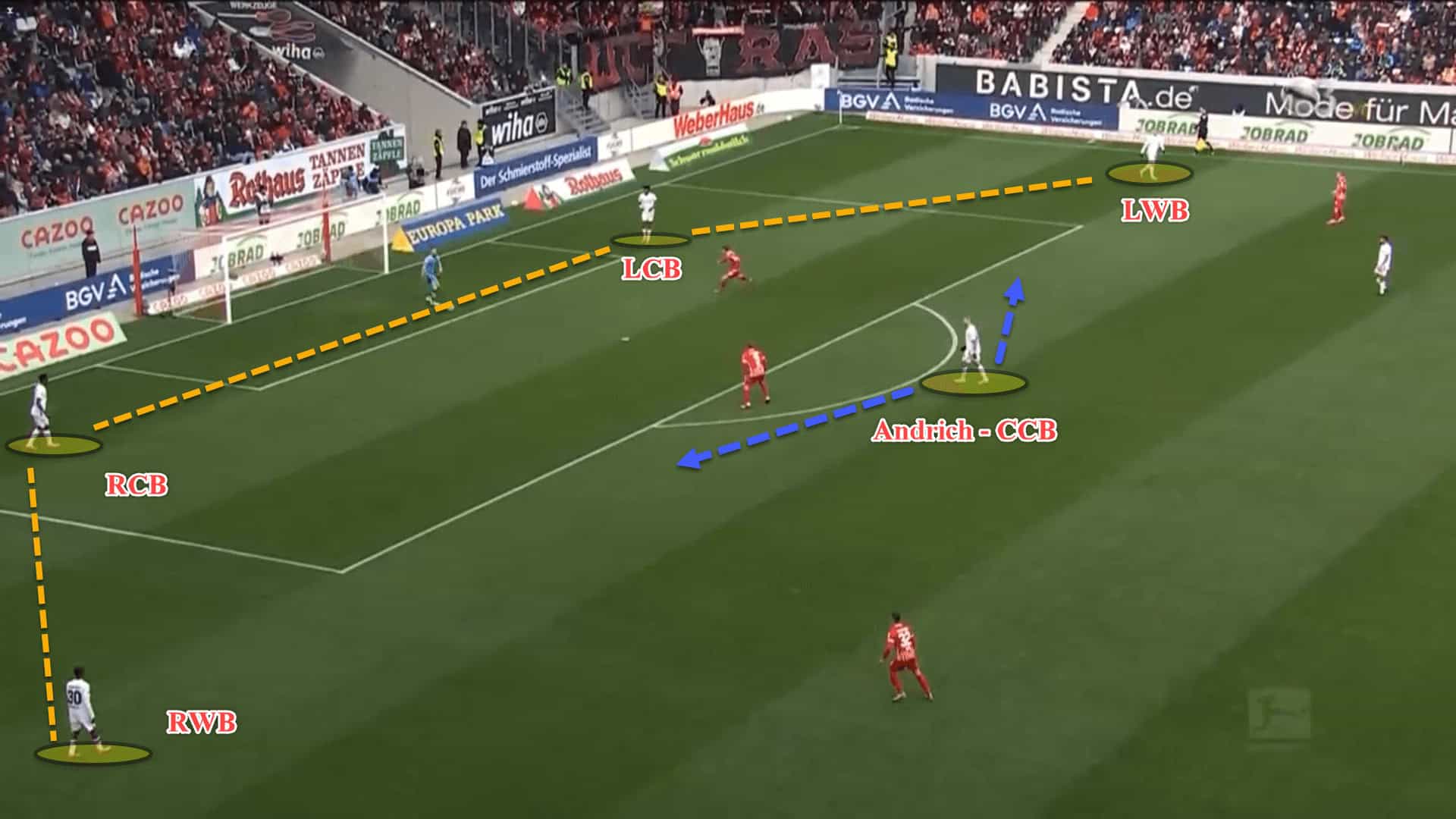

It is also worth adding that, in a game back in February versus Freiburg, Alonso opted to use Robert Andrich as a free man behind the opposition’s first pressing line, instead of instructing him to pin an opponent.

Andrich is a midfielder by nature but started the game in the centre of the back three. During the build-up phase, the former Union Berlin man would constantly look for passes to his feet so that he could turn out and play forward.

Alonso is unable to use Tah in this role as the mighty German wouldn’t be as comfortable taking the ball on the half-turn as Andrich and so Tah is primarily tasked with pinning opposition players. However, it shows that Alonso is well aware of the capabilities of his players and tweaks his tactics on a game-to-game basis depending on who he has at his disposal.

Return of the ‘Libero’?

The word ‘libero’ simply means ‘free’ and references having an extra man at the back against the opposition’s forward line. A historical example of using a ‘libero’ came when teams used a back three against a front two. Numerically, the back three had an advantage. Two would go man for man while the remaining centre-back would mop up behind. In English football, this role became known as the ‘sweeper’.

And speaking of German football, Franz Beckenbauer was arguably the greatest libero of all time, playing at a time when back-three systems ruled Deutschland.

The adjustment to the offside rule in 1990 brought about the end to the ‘libero’ but remnants still remain in the modern game. Furthermore, teams began defending zonally as a collective block and man-marking became a thing of the past, leaving the ‘libero’ role with little use.

However, after a recent 1-1 draw against Freiburg in the Bundesliga, Xabi Alonso made some interesting comments about Andrich:

“He played very, very well in that position. He was like a ‘libero’. He defended in the middle.” But what exactly is Alonso’s version of a ‘libero’?

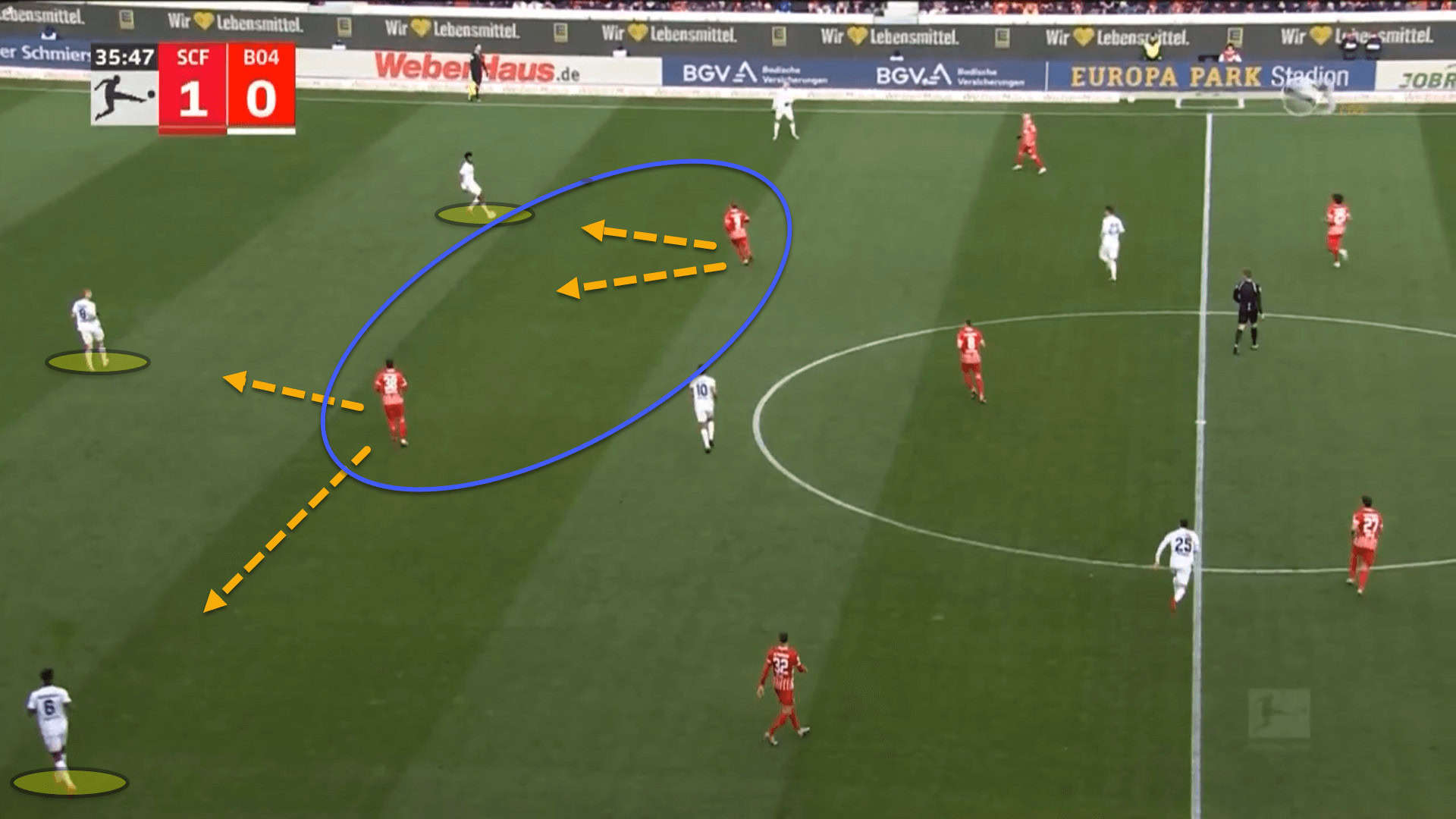

Alonso’s ‘libero’ could easily be interpreted as just being the free man in possession. Freiburg defended in a 4-4-2 mid-block, as they so often do, and Andrich played as the centre of the three. With enough ball circulation, Andrich was able to get on the ball and provide some progressive line-breaking passes and switches of play to help Leverkusen to reach more advanced areas of the pitch.

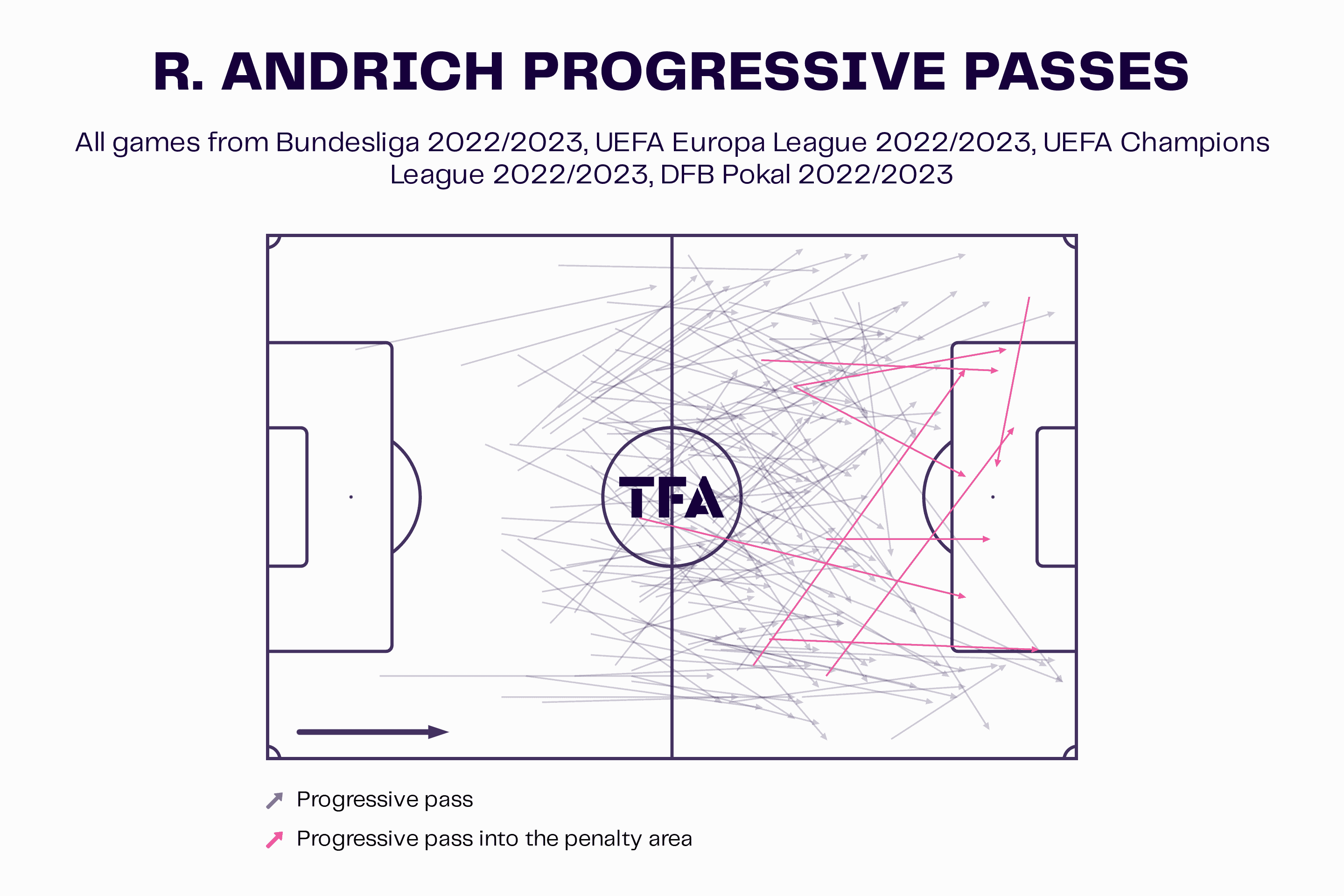

Andrich is naturally an excellent ball progressor anyway, as his heatmap below highlights, and so having this quality in the centre of the backline helped aid progression for Alonso’s team.

‘Liberos’ were normally superb on the ball and were vital to how sides played out from the back and progressed up the pitch. Quite often, players such as Beckenbauer would bring the ball out from defence and stay in the midfield area to offer a passing option for an amount of time before dropping off once more.

Again, old-school man-marking facilitated this because the ‘libero’ was the free man and was able to do so unscathed. This time is no longer afforded to players when they make line-breaking runs past the opposition’s first line of pressure but with the right technical ability, it can still be effective.

Here, Andrich carried the ball through Freiburg’s first defensive line, causing one of the opposition players to step out to him. There was an obvious pass on directly in front of Andrich, but the midfield-cum-central defender opted to turn back and play to his defensive partner. Nonetheless, the option was there which was created by Andrich’s penetrating run.

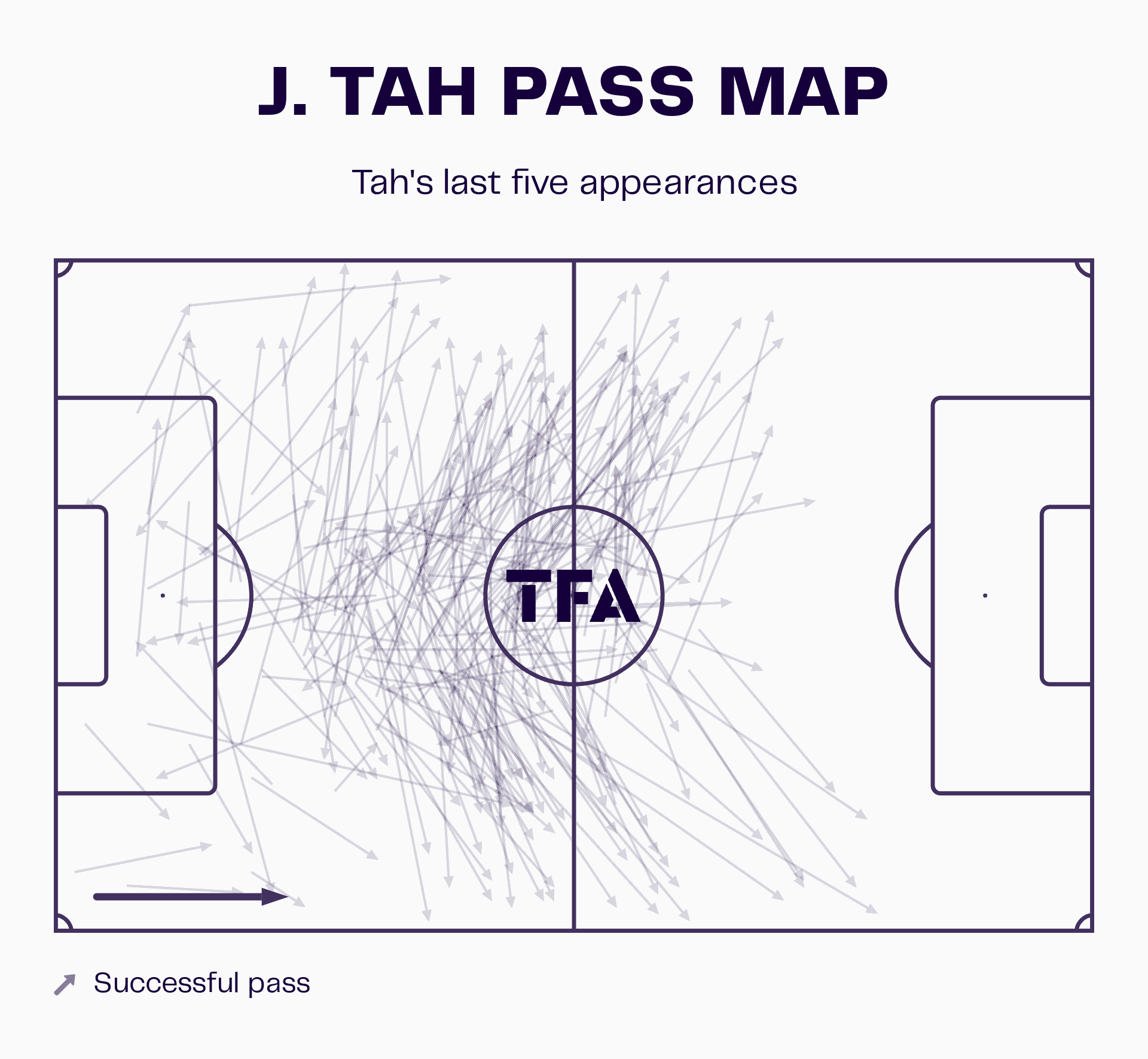

There is also an emphasis from Alonso for his central centre-back to hit switches of play out to the flanks, taking up responsibilities that a pivot player would normally be tasked with. Jonathan Tah is excellent at this and Alonso has a lot of faith in his star defender to perform this role.

From Tah’s pass map over the last five games in all competitions, we can see how many have been switches of play out to the flanks.

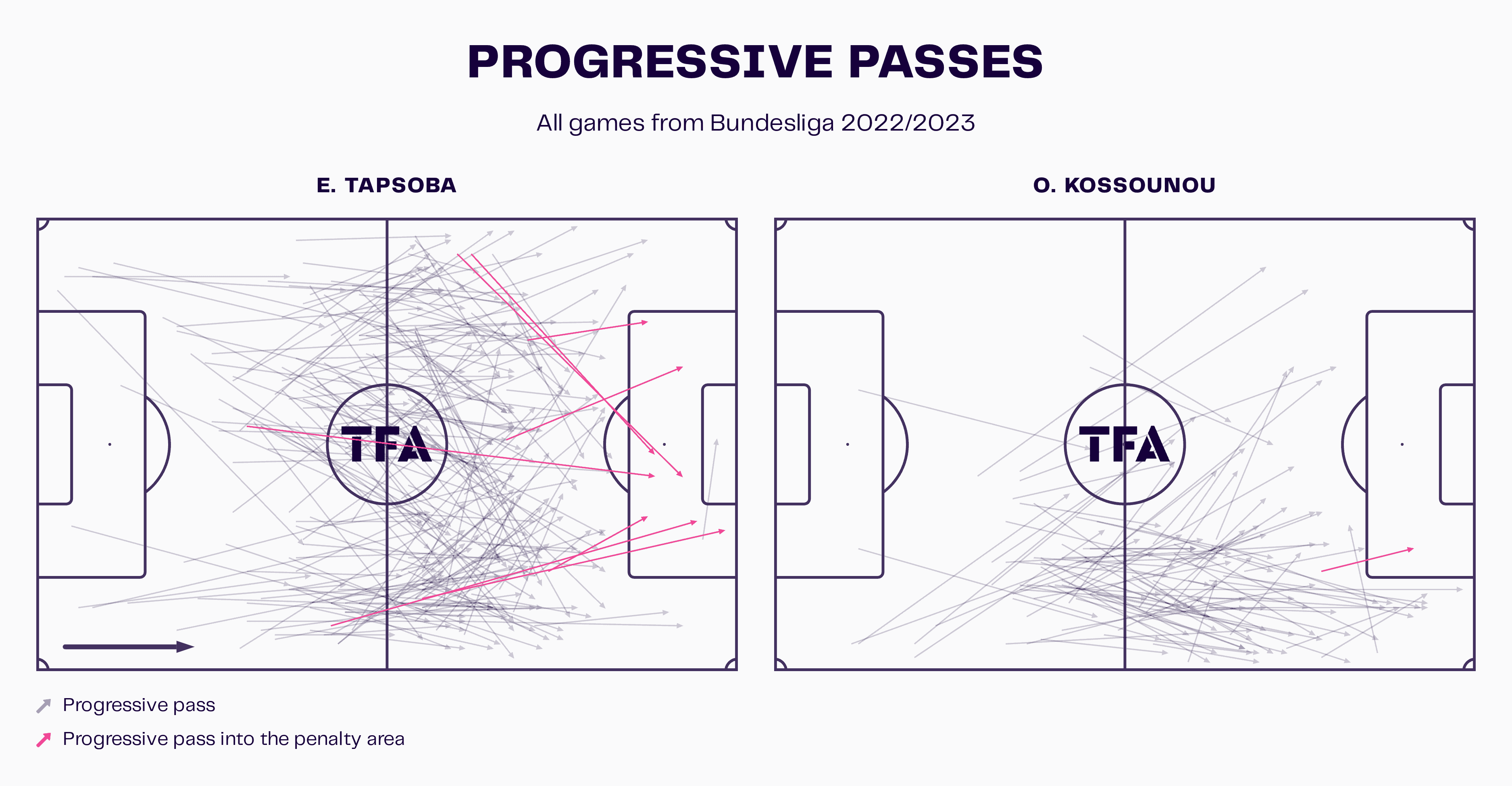

But while the central centre-back is responsible for making the side tick, switching the play constantly and often breaking the opposition’s first line by carrying the ball into space, it is the wide centre-backs who make the most line-breaking passes, being patient on the ball and waiting for the right time to strike.

Here, Tapsoba stalled and stalled until a passing lane opened up higher up the pitch. His pass was timed to perfection and Leverkusen got themselves into a dangerous position to attack Eintracht Frankfurt’s exposed backline.

Kossounou and particularly Tapsoba have contributed to many progressive passes this season under Alonso and the back three are certainly more important for ball progression and dictating the game’s tempo than any other players on the pitch.

It is impossible for a centre-back to have the same responsibilities as an old-school ‘libero’ given that the game has moved on from a tactical perspective as well as the added difficulties inflicted by the offside rule. However, Alonso has managed to bring back the esteemed role in some capacity which has made for incredibly fun viewing.

Rest defence

One area where the ‘libero’ is consistent with its origins is during defensive transitions. If the opposition keeps one centre-forward back defensively, such as in a 5-4-1 or 4-1-4-1 formation, Alonso will push one of the wide centre-backs into the final third to add an extra body to the attack.

He is fine with doing so because Leverkusen will still have two back to defend against the opponent’s one forward, keeping a 2v1 situation during rest defence.

However, if the opposition has two forwards playing in the first line, all three centre-backs will stay back, holding a 3v2 numerical advantage.

Rest defence is where the ‘libero’ role really plays its part and resembles its ancestor. The two wide defenders can go man-for-man against the opposition’s front two while there is one free to sweep up.

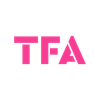

Here, Union Berlin attempted to hit Leverkusen on the break, but the visitors had adequate cover to deal with the threat. The wide centre-backs followed the two centre-forwards while Tah dropped off in case his defensive partners lost their defensive duels and he was forced to cover.

The biggest issue for Alonso comes when the opposition manager leaves three forwards high on the pitch for transitional situations. In these scenarios, it comes down to merely a case of quality versus quality in 1v1 duels.

Against lesser opponents, this isn’t really too much of an issue but when faced with stronger opposition, the counterattacking side can cause problems.

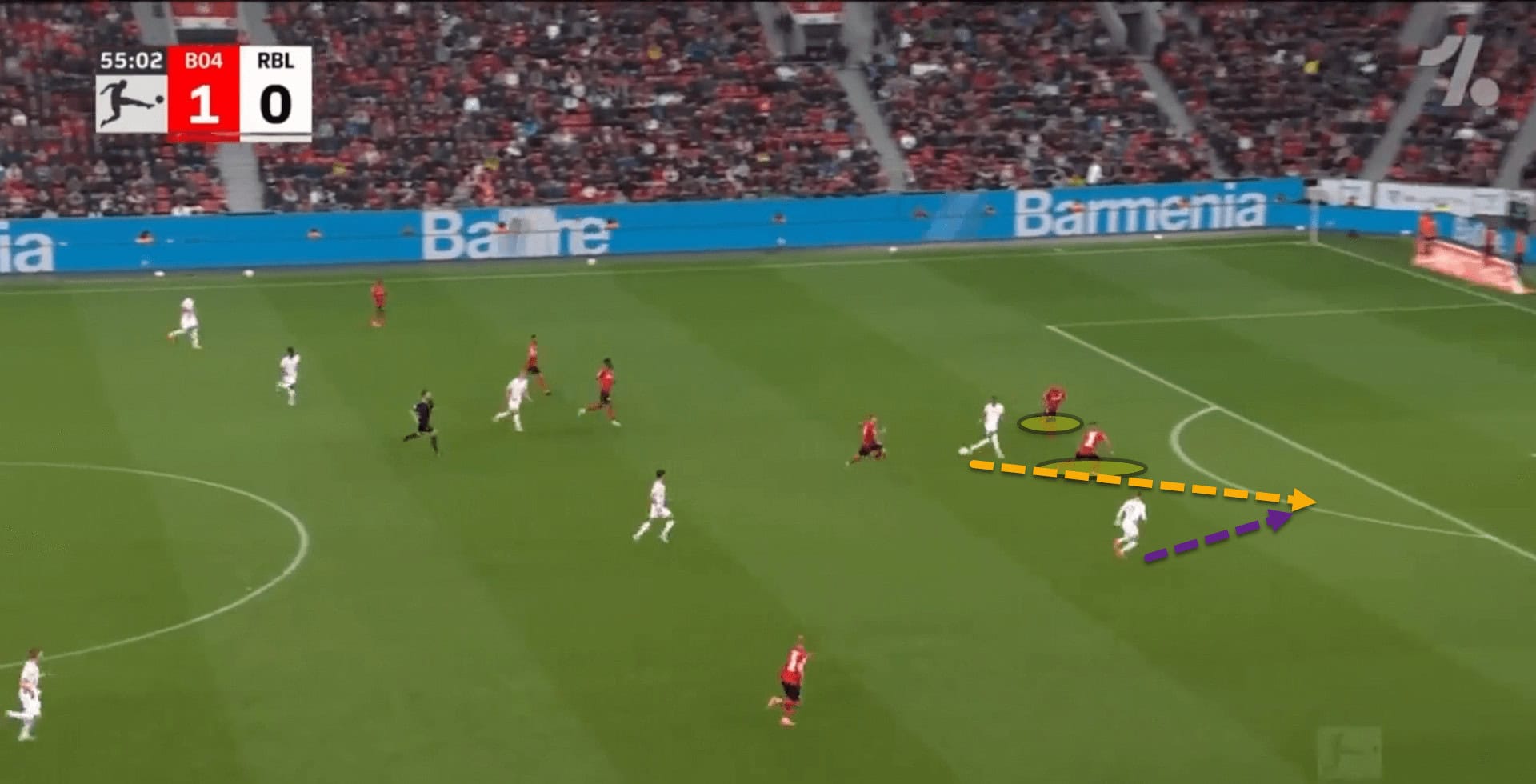

RB Leipzig didn’t score from this transition, but it was a close call for Alonso’s side as the three centre-backs were pulled all over the place and the visitors eventually got a shot away.

Nevertheless, there will always be risks associated with playing attacking football, particularly when positioning your defensive line so high up the pitch.

Conclusion

Alonso hasn’t reinvented the wheel with his use of the back three or a modern ‘libero’. He’s just merely taken some old cogs, ridded them from rust and found a way to use them to his advantage in the present game.

Leverkusen are unbeaten since mid-February and have picked up some incredible victories, such as the 2-1 defeat of Bayern Munich in Julian Nagelsmann’s final game in charge. With just four favourable fixtures left in the Bundesliga, it is very plausible that Leverkusen end the season with a hefty unbeaten run and potentially a European trophy.

Comments