Since Hansi Flick took over at Bayern Munich, Bayern have been undoubtedly one of the best teams in Europe. The former Germany assistant manager put the Bavarians season back on track within a matter of weeks, and has since led them to the league and cup double, averaging 3.1 goals per game in the process. Now, with the Bundesliga finished, Bayern will prepare to make a run at the Champions League, with the side tipped as one of the favourites for the tournament because of their domestic form.

With only two teams managing to take three points from Flick’s Bayern this season (Gladbach and Leverkusen), it begs the question of how do you actually hurt Bayern? As a result, in this tactical analysis, we will dissect Bayern’s set up and look at areas of the game in which teams have caused Bayern issues, including in and out of possession in detail. Furthermore, as well as identifying these weaknesses using analysis, I will detail three coaching practices that could be used to train players to exploit these weaknesses within a game plan.

Bayern’s build-up

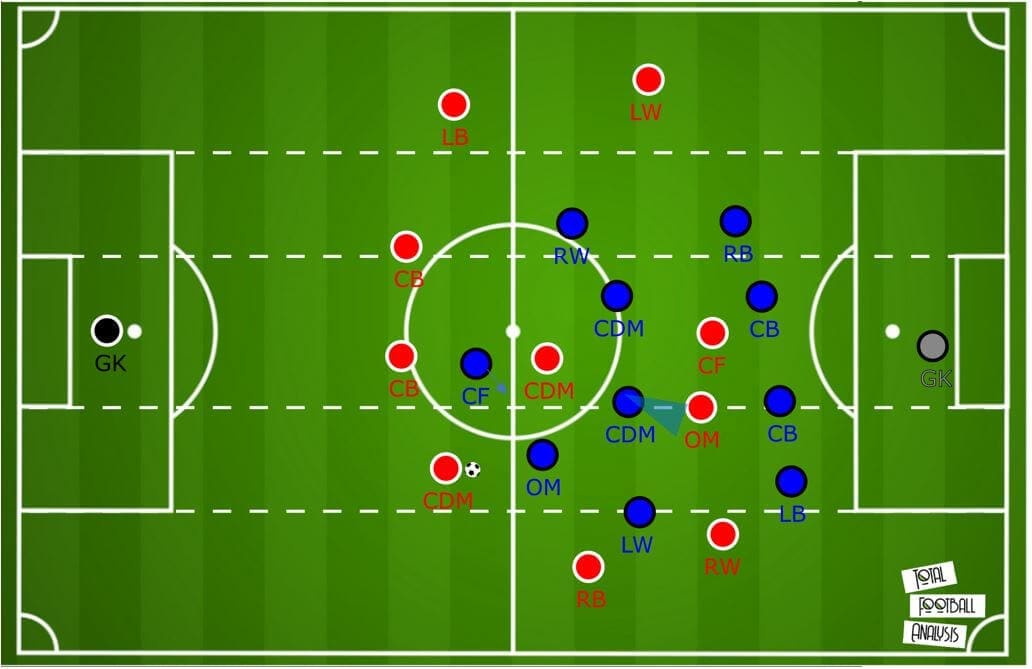

Bayern Munich build-up in a 4-2-3-1 shape, with some flexibility allowed by the double pivot’s movements. The most basic and predictable form of Bayern’s build-up can be seen here, with the shape resembling more of a 4-2-4 in their game against Bayer Leverkusen. The double pivot can sit behind the defensive line and is often marked by the opposition central midfield, while number ten Thomas Müller joins the front line and moves into the half-space often. With a well-coordinated press such as this 5-2-3 press here, this particular build-up shape can be nullified.

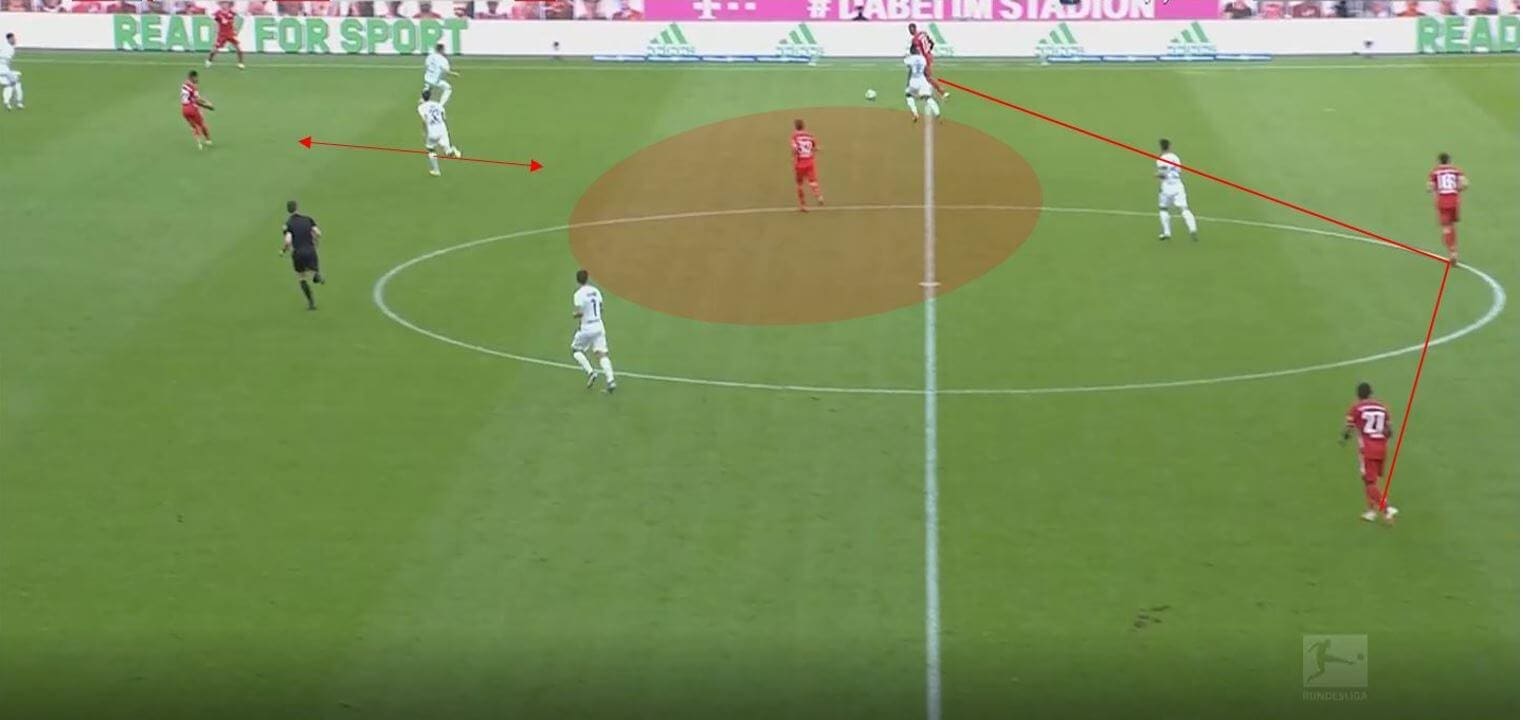

But as I’ve alluded to already, Bayern don’t just stay in this shape always. One variation they will use often involves depth/height, which is a key principle I’ll discuss throughout this article. When teams press Bayern high they will often drop one pivot deeper, usually just behind the first line of pressure as they do here. By dropping deeper, they invite their central midfielder marker (circled in red) to push high to press, however because the centre back is in possession, the Leverkusen central midfielder won’t push too high, or they risk leaving lots of space in behind. As a result, Bayern will often be able to create a free man in these kinds of situations, as teams won’t follow them that high. Bayern’s pace in behind and the presence of four attackers on the backline, therefore, helps to pin the opposition midfield.

Bayern can then execute several nice movements and combinations from these areas, and their offensive spacing is almost always excellent, meaning decisional problems can be created all over the pitch. We see here the pivot drops deeper to escape the pressing of the man marker, while the high positioning of the Bayern winger pins the full-back in place. Once the pivot receives, the full-back can make a forward movement to receive, which triggers the opposition wing-back to press. Bayern’s winger can then make a move towards the centre to receive, taking advantage of the space left by the pressing Leverkusen midfielder.

In another variation from the same game, we see they form a back three with Goretzka, and Joshua Kimmich then drops into the pivot space. Gnabry occupies the half-space and Boateng has access to him, therefore Gladbach central midfielder Neuhaus has to cover the space behind himself. Therefore, Kimmich is left open to receive.

In a similar scene to this one above, we get a good idea of their offensive structure as a whole, but again it is all underpinned by the positioning of the double pivots. Goretzka drops in as a wide centre back while Kimmich stays deep and moves into that pivot space behind the first line. His depth allows him to receive, and Müller drops to pin a central midfielder in place. Similarly to above, Gladbach’s full-back can’t move to cover the wing-back or they risk the space in behind, and Gladbach’s central midfielder also doesn’t want to press Kimmich initially for the same reason. Bayern’s space occupation causes decision-making problems for the opposition defenders, and so players have to be trained to deal with these decisions.

Below, we see some of the rotations involved in Bayern’s positional play, with Goretzka again dropping very deep, where this time he is followed by a Leverkusen central midfielder. Bayern’s full-backs usually stay high and wide, but here Benjamin Pavard inverts, which leaves space for Gnabry to receive deeper on the wing. Goretzka plays the ball wide, which triggers Pavard to move forward. This is extremely effective because Pavard is now moving into the space left behind by the pressing Leverkusen central midfielder, and so that depth by Goretzka allows for Pavard to receive high in the half-space. I would give you 20 examples of great scenes like this but I’ll get onto how they press as that’s just as interesting.

Bayern’s flexible pressing

Again, Bayern’s initial set up out of possession is a 4-2-3-1, but within a game it can fluctuate between a 4-2-3-1, 4-4-2, 4-1-4-1 and 4-3-3, dependent on the opposition shape and dynamics of the game.

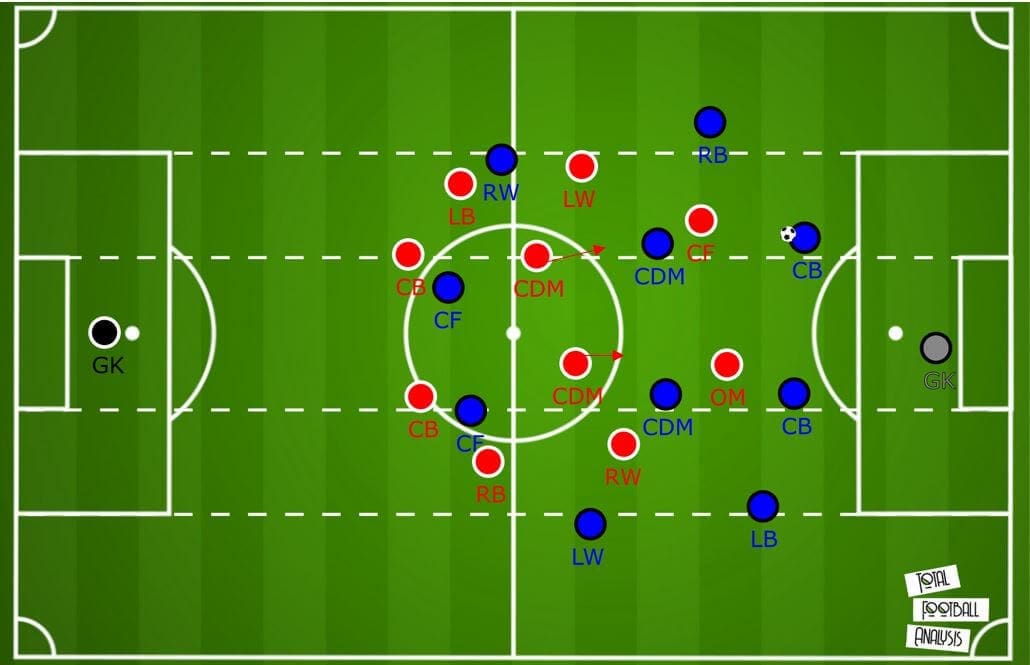

This image below gives us a basic overview of Bayern’s press, with it’s most common variation seeing Thomas Müller push up as a striker and pressing the centre backs. The wingers press the full-backs, while the double pivot of Bayern will press the opposition central midfielders. This 4-4-2 formation set up by the fictional opposition, therefore, plays right into Bayern’s hands.

Due to the dropping movement of opposition midfielders, Bayern will form a 4-1-4-1 of sorts, with one pivot sitting deeper often with an attacking midfielder. In these situations, the ten will sometimes be able to cover the far side pivot for the opposition, and the far side winger for Bayern may also be able to help. A 4-3-3 will arise momentarily if a winger pushes particularly high to press.

We can see a similar example as this here, but this time against a back three. The winger this time adjusts, so he presses the wide centre back while the Bayern full-back will push high to press the opposition wing-back. Müller here does a good job of nullifying the opposition, as he moves to protect the near side pivot, while another central midfielder pushes forwards to mark the other far side pivot. This leaves them in that 4-1-4-1 formation again, with the other Bayern pivot able to sit deeper and protect the high pressing wing-back.

Against a back three Bayern will usually do their best to press with their front two, although they can also use this structure here involving the wingers.

Using central overloads to build

Bayern’s press is flexible and their high players have good individual pressing skills, but there is a key weakness many teams have tried to exploit against Bayern, and that is the use of overloads around their central midfielders. This would be the main focus of training throughout the week.

Bayern of course only have two central midfielders in their formation, and so in possession using specific movements they can be overloaded and exploited well, as I’ll show in multiple examples here. The team who best utilised these overloads recently against Bayern Munich was Borussia Mönchengladbach, who used a variety of build-up variations in order to hurt Bayern.

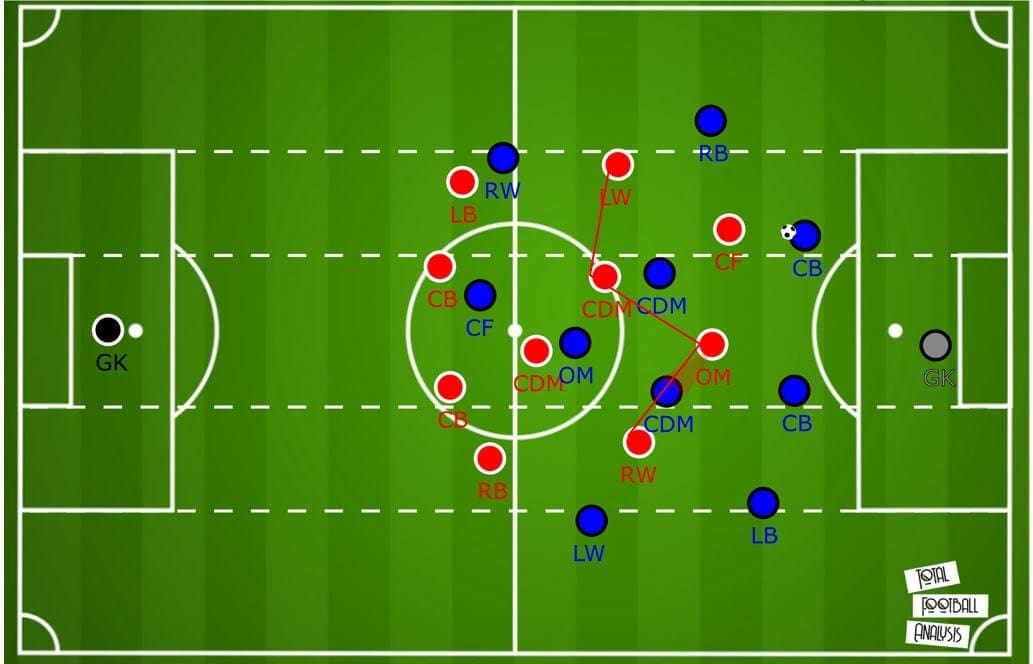

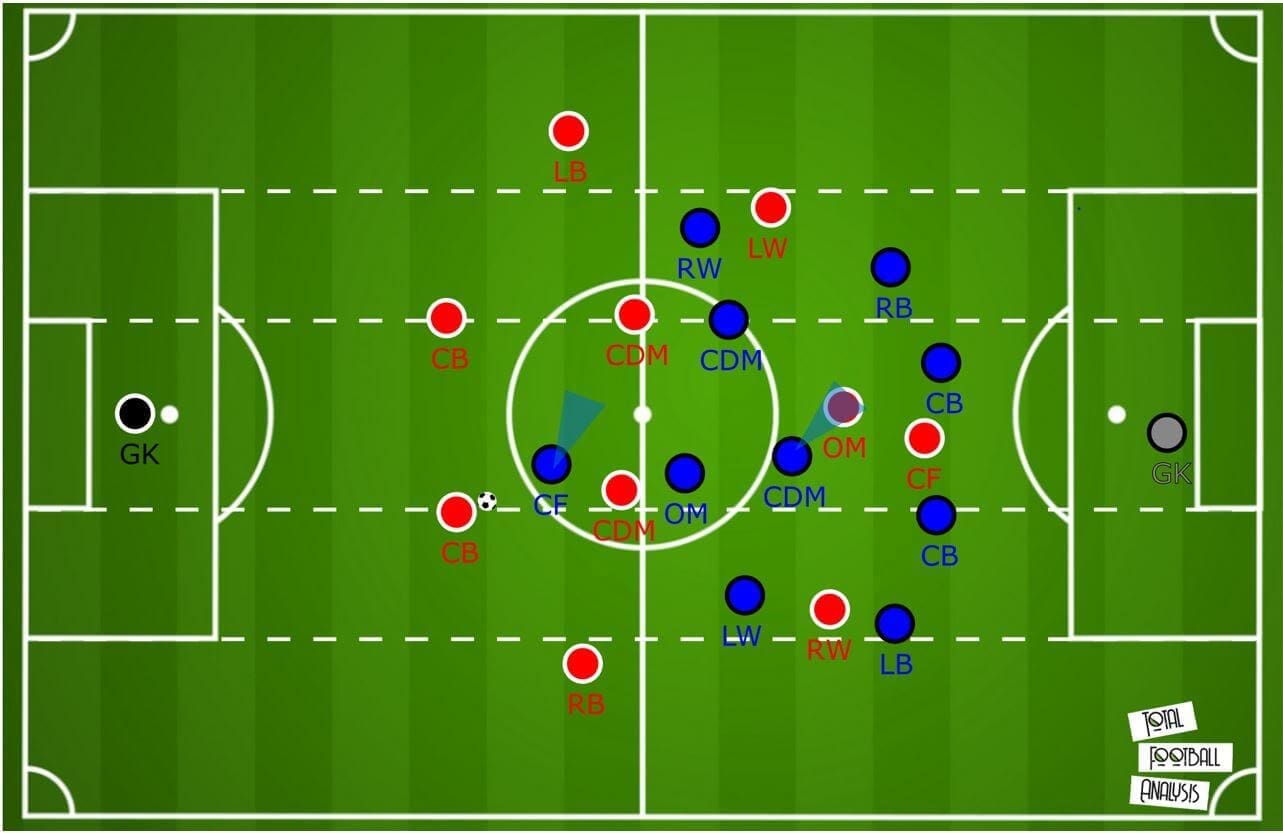

Gladbach played a 4-2-3-1, with number ten Lars Stindl often dropping in behind or beside a Bayern central midfielder, helping to create a 3v2 overload in central midfield, or 2v1 on an individual Bayern central midfielder. Here Gladbach use a vertical overload on Bayern’s right-sided central midfielder, with a player behind and in front of him. This creates a decisional crisis for this midfielder, as if he commits deeper he concedes space higher and vice versa, and therefore this is difficult to defend against. Gladbach work the ball wide and then can play into the space behind the Bayern midfielder, and they have players occupying Bayern’s backline which prevent them from pushing out to close this space. A Gladbach player occupies the full-back while another occupies the centre back and threatens to get in behind, which pins Bayern in place.

We can see an example of this here with the Gladbach centre back on the ball. Joshua Kimmich has a Gladbach player either side of him, while Leon Goretzka occupies his role and would usually be covering the other Gladbach midfielder, who is slightly too deep here.

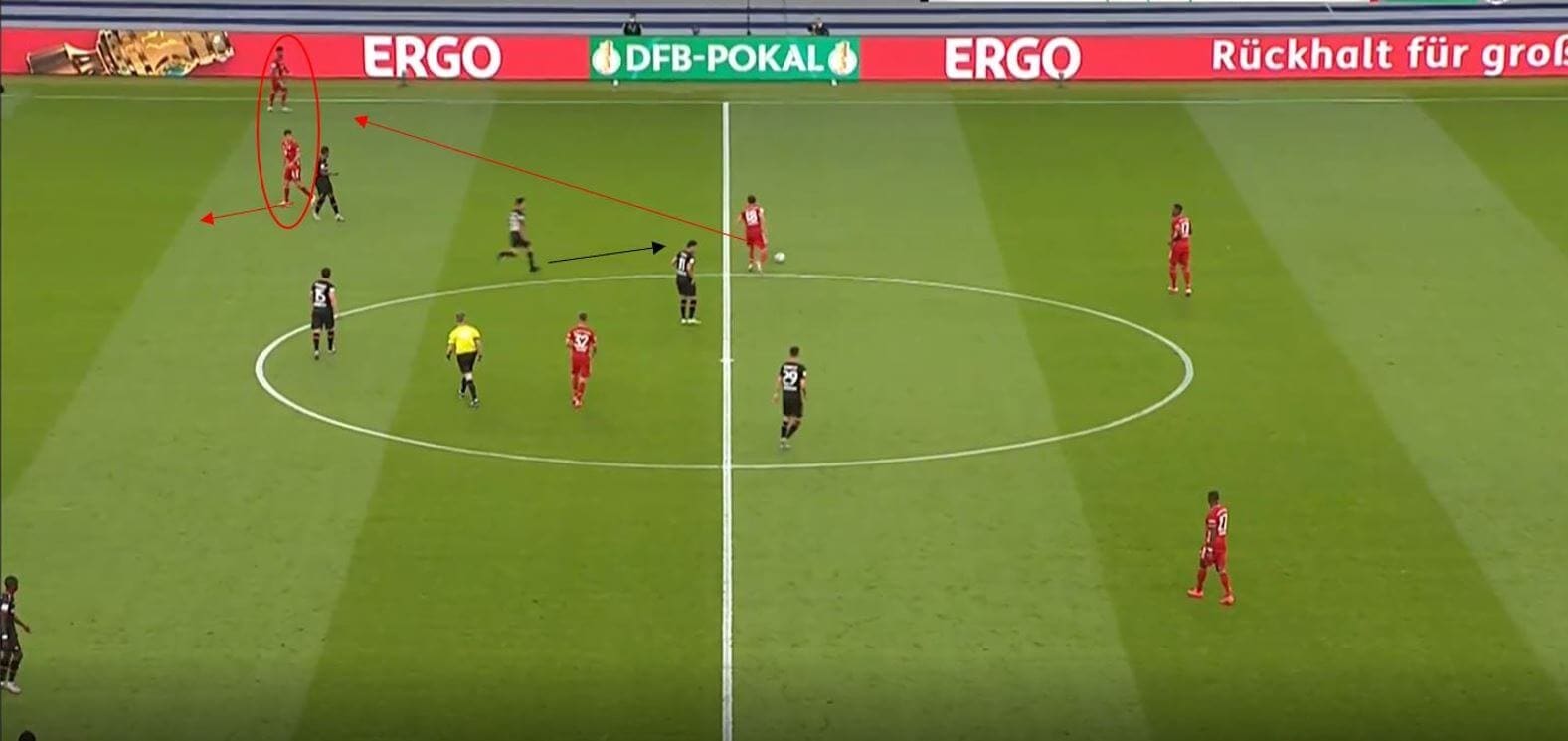

Here Gladbach form a back three and drop a singular pivot into the centre. Winger Jonas Hofmann now drops inwards to occupy the nearest central midfielder, while Lars Stindl ghosts in behind Joshua Kimmich. Kimmich then has the same dilemma of pressing Florian Neuhaus or dropping deep. Neuhaus’ deep positioning, as well as his central positioning, makes him difficult to press, as he is equidistant between the two Bayern midfielders, and so it makes it awkward to decide who presses. Stindl is as a result allowed to receive behind the Bayern line.

Dortmund and Leverkusen also used this tactic well since the restart, and we can see Dortmund utilise it well here from a wide area. Kimmich is presented with a decisional crisis again due to the dropping Julian Brandt while the far central midfielder (Goretzka) is pinned by the Dortmund central midfielder. Here Kimmich could perhaps press Dahoud and cut the lane to Brandt with his cover shadow, but in a split second he decides to cover Brandt. Again Dortmund do well to pin the Bayern full-back to prevent him from coming to press.

Dortmund even used some excellent rotations and dismarking strategies as we can see here. Here in a creative method of progressing the ball, Brandt rotates positions with Thomas Delaney quickly, with Brandt moving high to deep, while Delaney goes deep to high. This rotation allows some separation from the central midfield marker, and also allows the overload to be created and exploited well in this case.

As a result, our in possession set up will utilise three central midfielders, with rotations around whether they drop deep as a pivot in front of Bayern’s midfield, or sit behind the Bayern line. In line with our out of possession set up which will be discussed later, the formation will mirror a 4-1-4-1/4-3-3.

Practices to train overloading the central midfielders

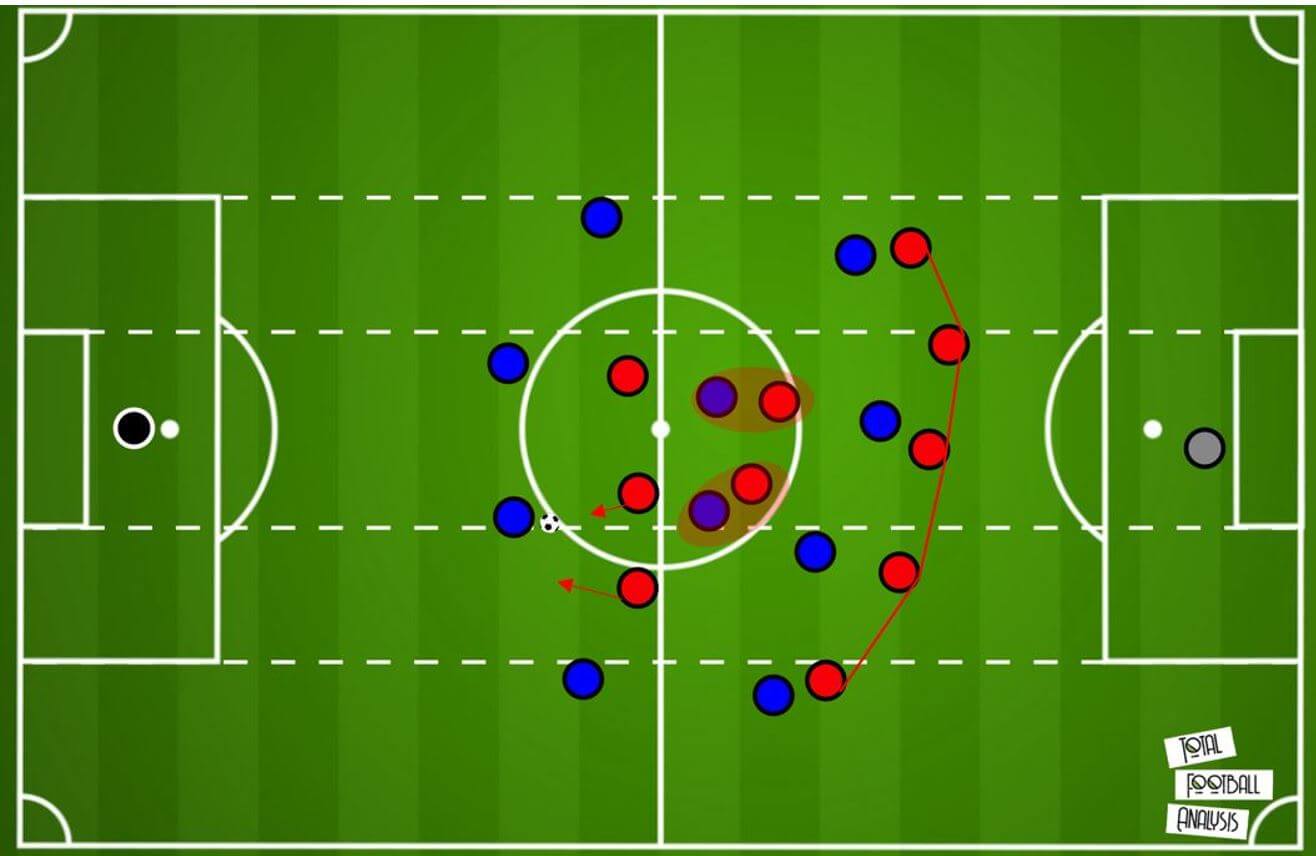

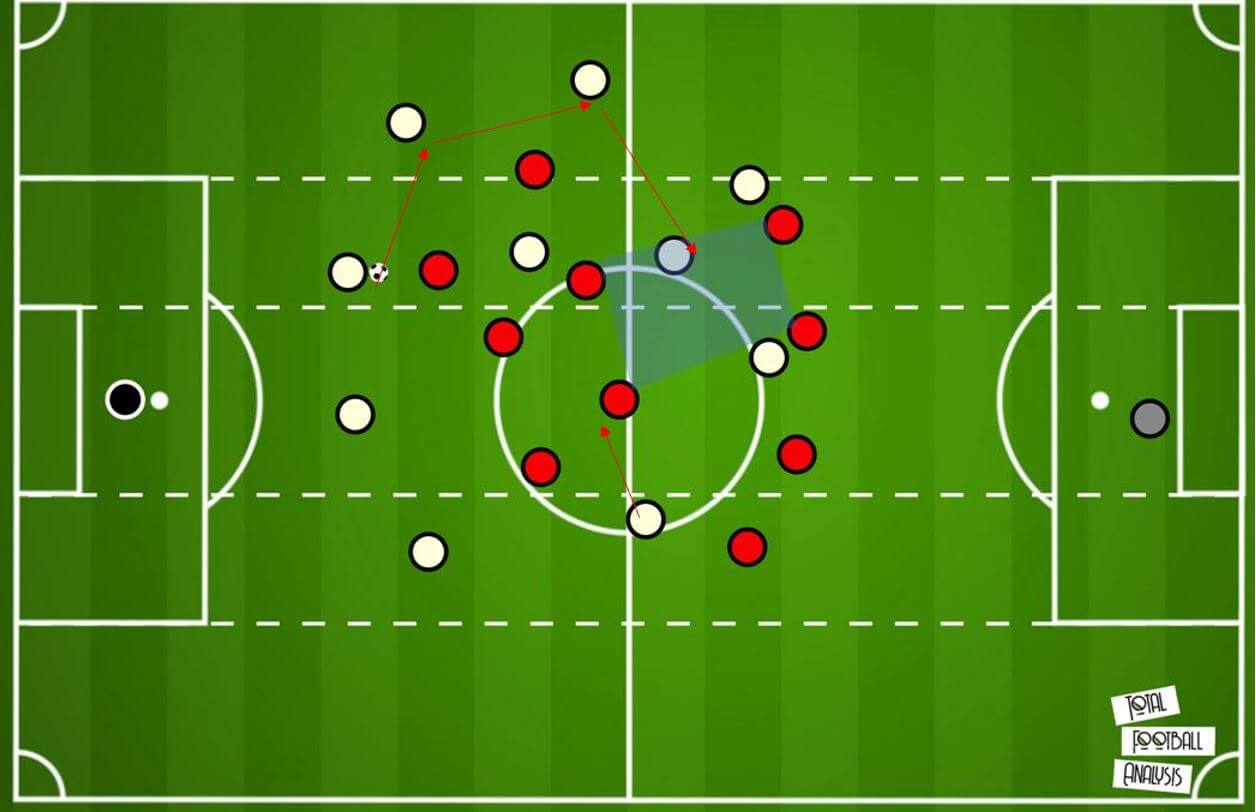

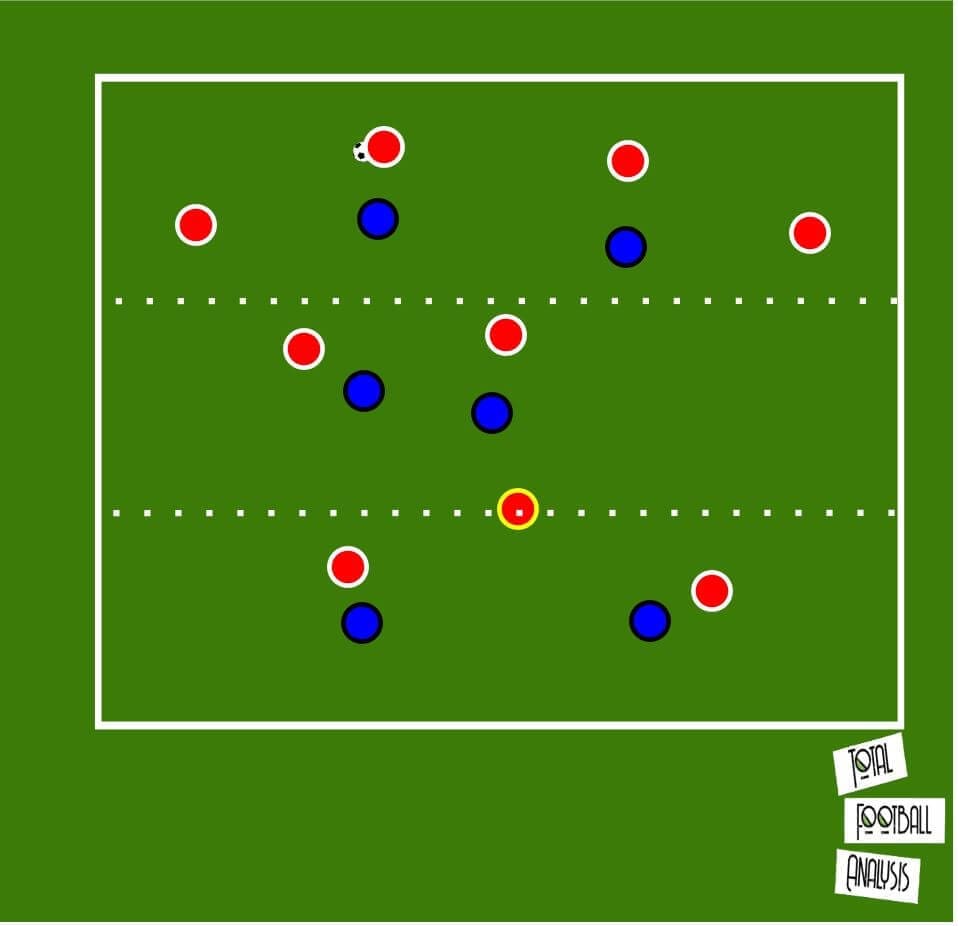

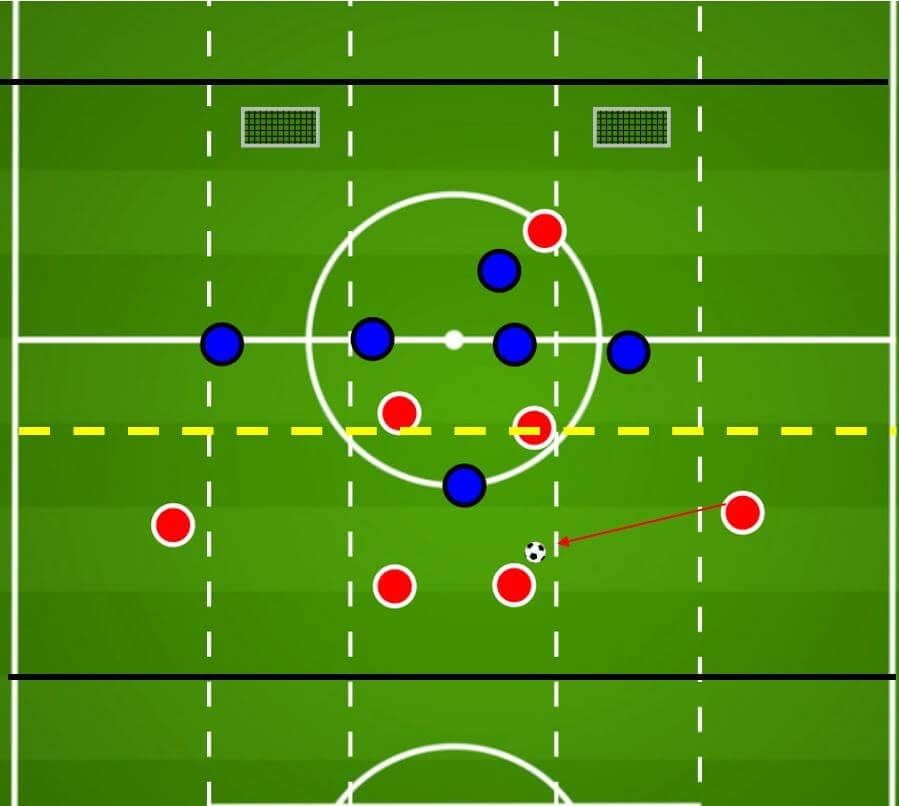

To train this movement and the various patterns around overloading the central midfielders, we will try to replicate the scenario and use constraints to place emphasis and value on particular solutions. In this practice, the ball will always start with the red team building from the back in a 4v2, with all offensive and defensive players locked into zones initially apart from the yellow outlined player. The chosen player or number ten (outlined yellow) gets one point for receiving in the middle zone, and also receives double points if they receive from a full-back. Once the ten drops into the middle zone, midfielders can move freely between zones, and so for example can drop deep to act as a single pivot or form a back three. If the ten leaves that zone everyone must return to their original position. Points are scored by touching the ball in the end zone just off the pitch.

This trains the need for the ten to drop to receive, and the extra bonus for the full-back encourages wide build-up play, as it is much easier to create these overloads on the central midfielder from wide areas. The full-backs could risk playing vertically, but they would then miss out on the points possible for the ten in the middle zone receiving. Wingers or forwards will likely stay wide, and therefore help to pin full-backs in position as we saw in previous examples. Players have the option to use several strategies to overload the central midfielders, but they are all underpinned by the number ten or by having three midfielders engaging two opposition midfielders. The coach can show video of the scenes I have highlighted in this analysis, and can also allow the players to be creative to find other ways and rotations to create the overload.

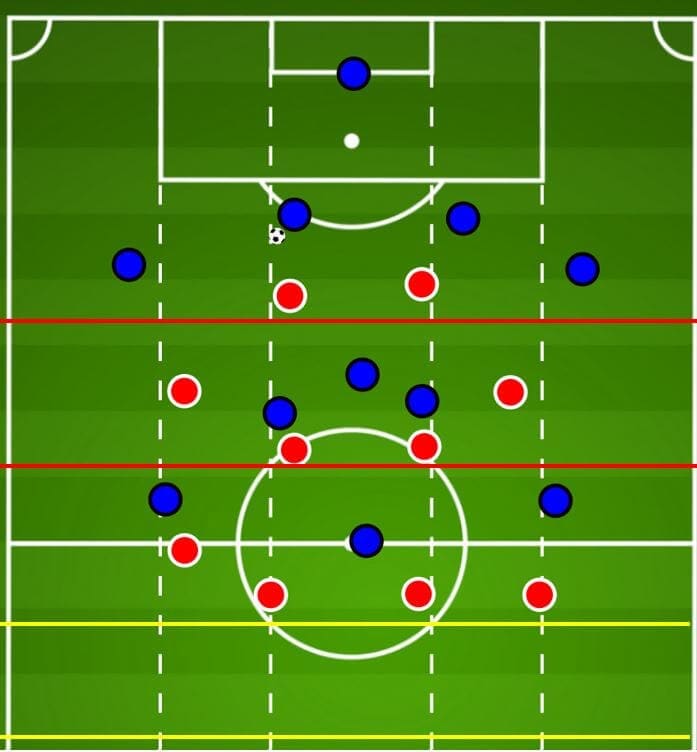

To develop this into 11v10, we can mirror the exact press of Bayern and act under similar constraints, with the only constraint being that a minimum of three players must always occupy the midfield zone. Again it is an end ball type game, and so points are scored by getting into the yellow end zone. Other rules could be bonus points for receiving in the half-space or a bonus for arriving into the zone. Either pitch could also be made into a diamond to increase diagonality, but verticality could be beneficial here if done correctly, and it also allows for the central midfielders to be dragged wide. Wide forwards may look to (or have to) push forward to have three players in the zone, which mirrors that idea of those players being involved in the overloads, as Gladbach did in some of the scenes noted. There are a whole host of different adaptations or ideas, such as individual constraints to players, but this gives a shell to the practice. The out of possession team will be shown a video on how Bayern press, and will be given bonus points for how high they win the ball back, as this will mirror Bayern’s intensity.

Out of possession plan and practices

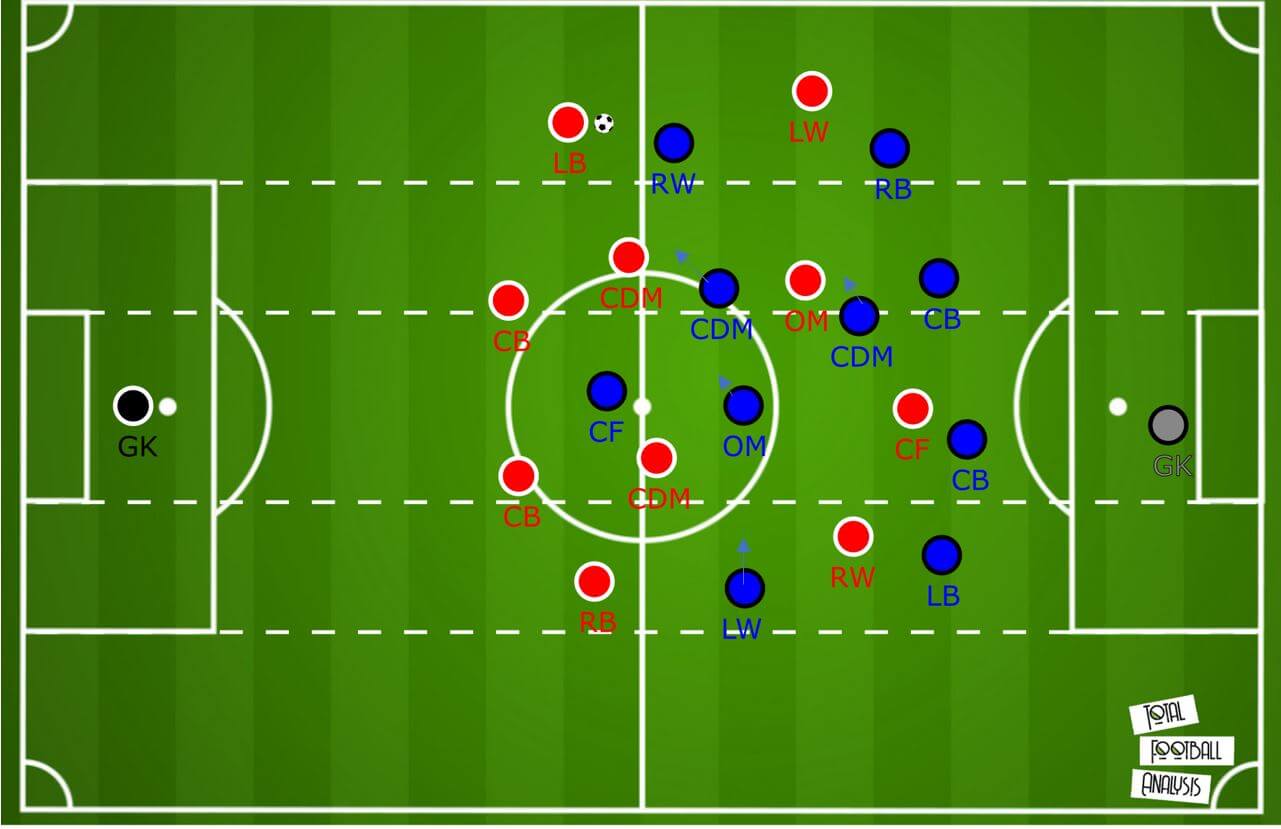

To aid the transition between in and out of possession, the formations and paths to press should be fairly clear and similar. As a result, while our in possession shape would be a flexible 4-3-3, our out of possession shape would be more of a 4-1-4-1. Pressing Bayern Munich high is extremely difficult due to their shape, technical ability, and threat in behind, and so as a result a mid-block would be used within this 4-1-4-1.

The striker looks to press the centre backs as intensely as they can, and will keep the far sided pivot in their cover shadow as much as possible, which allows for the far sided central midfielder to push across with less risk. The deeper midfielder allows for more flexibility in the pressing structure, and also allows for more depth, which is beneficial in dealing with Bayern number ten Thomas Müller. This defensive midfielder will sit deeper and be fairly zonal man orientated to Müller, and so will keep him in his cover shadow and remain within pressing distance, but not get so tight that it is strictly man-marking. This should allow for some stability and cover in the side and prevent any of Bayern’s rotations causing problems. If the ball is in the half-space with a centre back, you would expect the defensive midfielder to be around this area too. The two other central midfielders can press in the same way and prevent ball progression through the centre, while the press is fully triggered by a pass out to the full-back, where the wingers will then press intensely.

When the ball goes to a wider area, the winger can press from the front and look to cut off a pass into the half-space. It is therefore vital that the midfield shifts from side to side optimally, as the number six or defensive midfielder has a vital job of filling the half-space.

If Bayern fall back into a back three, the formation would then resemble more of a 4-4-2/4-4-1-1, with the nearest central midfielder following his central midfield marker towards the back line to press. This could potentially allow Bayern to create an overload in central midfield like we have tried to do to them, but the striker is encouraged to attempt to cut the passing lane to the pivot if possible, meaning the formation will constantly switch from a 4-4-1-1. This is in many ways a similar pressing scheme to Bayern then, except the depth of the formation means that a permanent defensive midfielder is more likely.

Leverkusen’s 5-2-3 press also had some early success that could be worth exploring further, and this would mean that that defensive midfielder would not join the backline out of possession and step out to cover the half-space, rather than keeping the player behind them in their shadow. A flexible compromise between these two systems could also be effective potentially.

A practice training defending in a 4-1-4-1 mid-block

For our pressing section, we will mainly constrain the offensive team, in order to manipulate the pattern of the game and allow it to mirror Bayern Munich’s as much as possible. Again, the offensive team would be briefed on Bayern’s style of play and tactics.

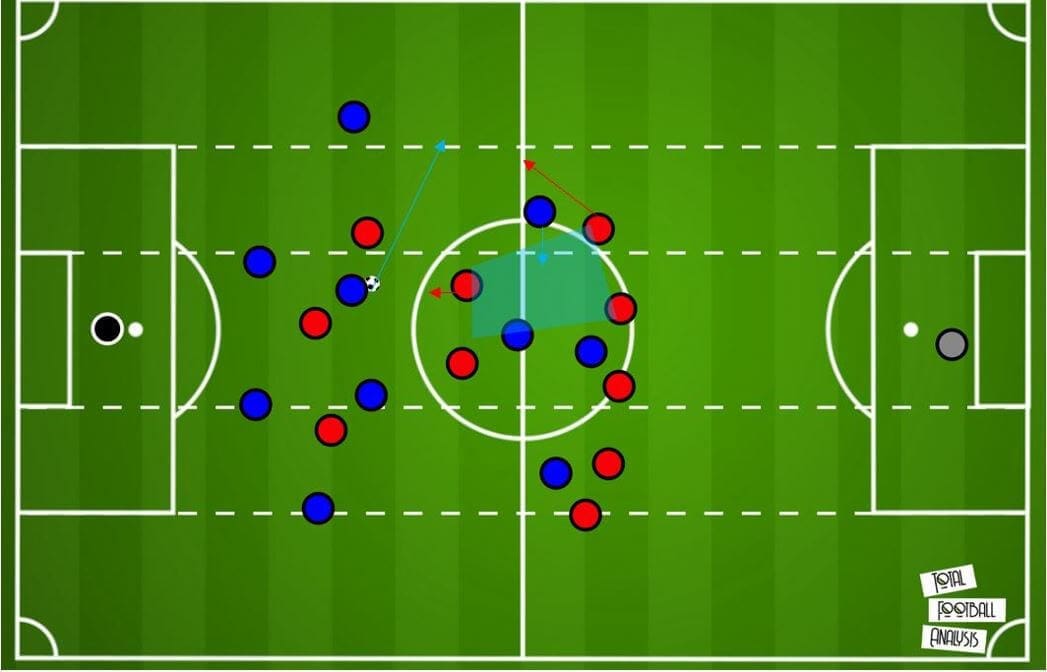

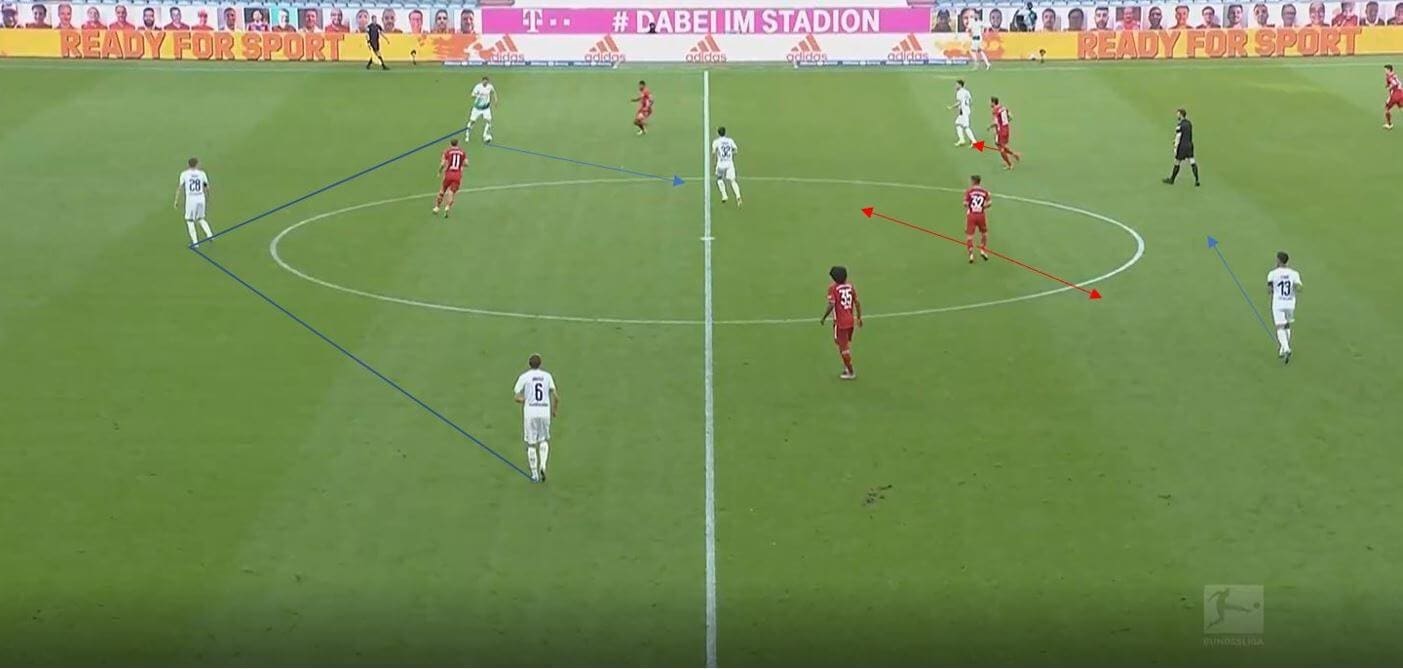

The practice is in a 7v6 format, mirroring the first two lines of the press. Play will always start with the coach playing into the in possession team (red) full-back. The red team simply looks to score in one of the two goals, located in the half-space. However, a rule is added that if you score through the goal on the opposite side to the full-back who first received, the goal is worth three points. If it is scored on the same side, it is worth one. So here, the right full-back has received, and then looks to switch it across the backline to reach the left half-space goal. Therefore, we manipulate the behaviour of the in possession team, which affects the experience of the out of possession team. The blues are therefore trained often on that switching of play and remaining compact throughout. The pitch should be made quite wide to increase difficulty, and the length of the pitch around 60 yards to mirror the correct pitch geography. The yellow dotted line can be added also, which represents the line of engagement. If a player moves past this line to press, and the ball goes forward past him beyond the line of engagement, they are locked out and can’t advance past. This trains the idea of only pressing if certain the ball won’t go past, and helps players to balance that risk vs reward and forces some of that discipline needed in a mid-block. It also gives an affordance (clue) to the offensive team, as they can then drop behind this line of engagement to try and avoid pressure, which is exactly what Bayern Munich’s pivots do.

The defensive team aren’t awarded points, but instead look to keep the score as low as possible for the opposition. This could be changed easily. In summary then, this practice looks to mirror the dynamic involved in the midfield press against Bayern Munich.

Conclusion

This article does, of course, miss some context such as players and the existing principles of the team, but the aim of this analysis is more to provide an idea into some of the ‘weaknesses’ Bayern have, and how you might prepare a team to deal with those problems.

Bayern are without doubt one of the best teams in Europe both in and out of possession, and their ability to deal with their systematic weaknesses in an almost reactionary way is part of what makes them excellent. I’ve no doubt Hansi Flick knows about this potential overload in midfield, but he trusts his central midfielders to nullify such overloads and obviously prefers a more intense aggressive approach with a number ten. As a result, even if you do create the situations that Leverkusen, Gladbach and Dortmund have created since the restart against them, you may not be able to get through. It is simply about creating as many of those situations as possible and finding constant solutions to the problems they face. I look forward to seeing if anyone left in the UEFA Champions League can do that.

Comments