Positional play, also known as Juego de Posición, can bring about some of the most extravagant and impressive attacking football. When people think about positional play, the first name that comes to mind quite frequently is Pep Guardiola, who learned it from Johan Cryuff during his time at Barcelona. The truth is, many coaches use aspects of positional play in their game models, some more than others. One of those coaches who have incorporated positional play into their game model is Hansi Flick during his relatively short time at Bayern Munich. The results have been outstanding: at the time of writing, Bayern have won 21 out of a possible 24 matches, with two losses and one draw, his team scoring a total of 75 goals, averaging 3.12 per match.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics that Flick has implemented at Bayern, which have resulted in their rise to the top of the Bundesliga table. The analysis in this scout report will highlight some of the key principles of positional play and how they’ve been applied at the Bavarian club. While this article certainly could not encompass all of the elements of positional play at Bayern, the focus will be on the overarching principles that have allowed Bayern to see the immediate success that they’ve enjoyed this season under Flick.

Positional play principles

At the core of positional play is the search for superiority. There are three different types of superiority most frequently seen in positional play: positional superiority, numerical superiority, and qualitative superiority.

When talking about positional superiority, one of the key ways to establish this is to have players behind (or often between) defensive lines of pressure. This works in conjunction with a team’s positioning on the pitch. The more space (height and width of the area of play) a team creates, the more stretched defences usually get, which results in more space for players to occupy between the defensive lines. Maintaining the balance of height and width is incredibly important, which is why positional rotations are so common in positional play.

Numerical superiority means having a free man in a situation. I would put the ‘third man concept’ as a key part of numerical superiority (although it is inherently interwoven with positional superiority); in its simplest terms, the third man concept is finding a free, unmarked player who can receive a pass. The third man can become the ‘free man’ if he has space and time to break defensive lines of pressure.

Qualitative superiority is the act of using a player or players’ strengths against an opponents’ weaknesses in order to create an advantage for a team. This can come down to attributes like speed, skill, ability, and individual positioning, amongst other things. A simple example: if your left winger has more pace and is one of the top dribblers on the wing, you’ll likely achieve an instance of qualitative superiority if you can isolate him 1v1 against the opponent’s right-back.

Positional play has two other large key ideas that will be addressed: manipulating the opponent and creating a successful build-up. Manipulating the opponent consists of identifying weaknesses in the opponent’s defensive structures. The most common way to exploit those weaknesses is to overload an area on the pitch in order to isolate the previously-identified weakness. This certainly isn’t the only way, but it’s an example. An effective build-up is important to be able to manipulate an opponent. Additionally, an effective build-up is also likely to force an opponent into their defensive shape, where their weaknesses that are available to exploit have likely already been identified. In short, an effective build-up allows teams to dictate the rest of the game.

Principles present during build-up

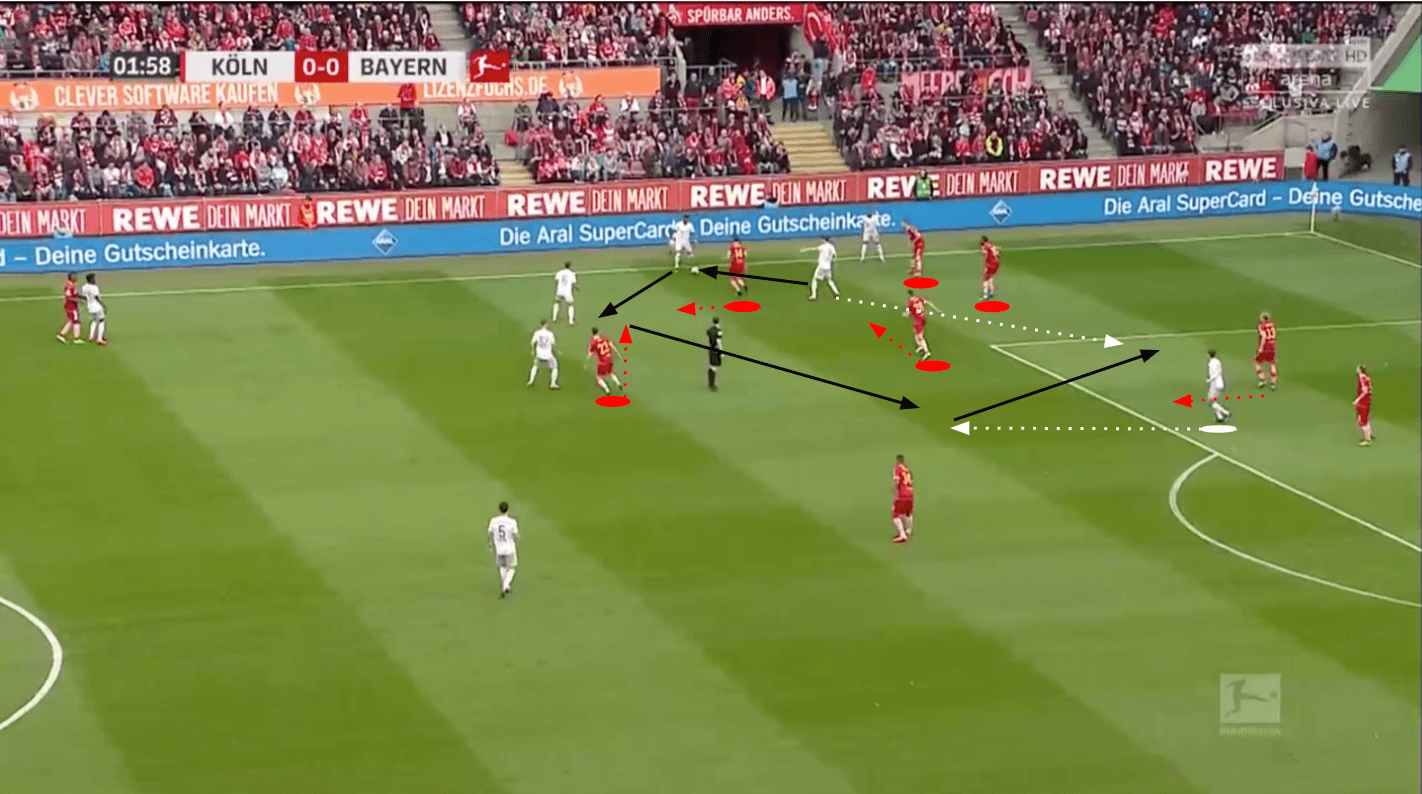

Most times, when teams play against Bayern, they tend to not press the team from Munich too much unless they are forced to based off of the context of the match. This is likely because teams know they can’t do it effectively as Bayern implement their positional play in order to progress up the pitch. Against 1. FC Köln, Bayern displayed exactly why teams are hesitant to press.

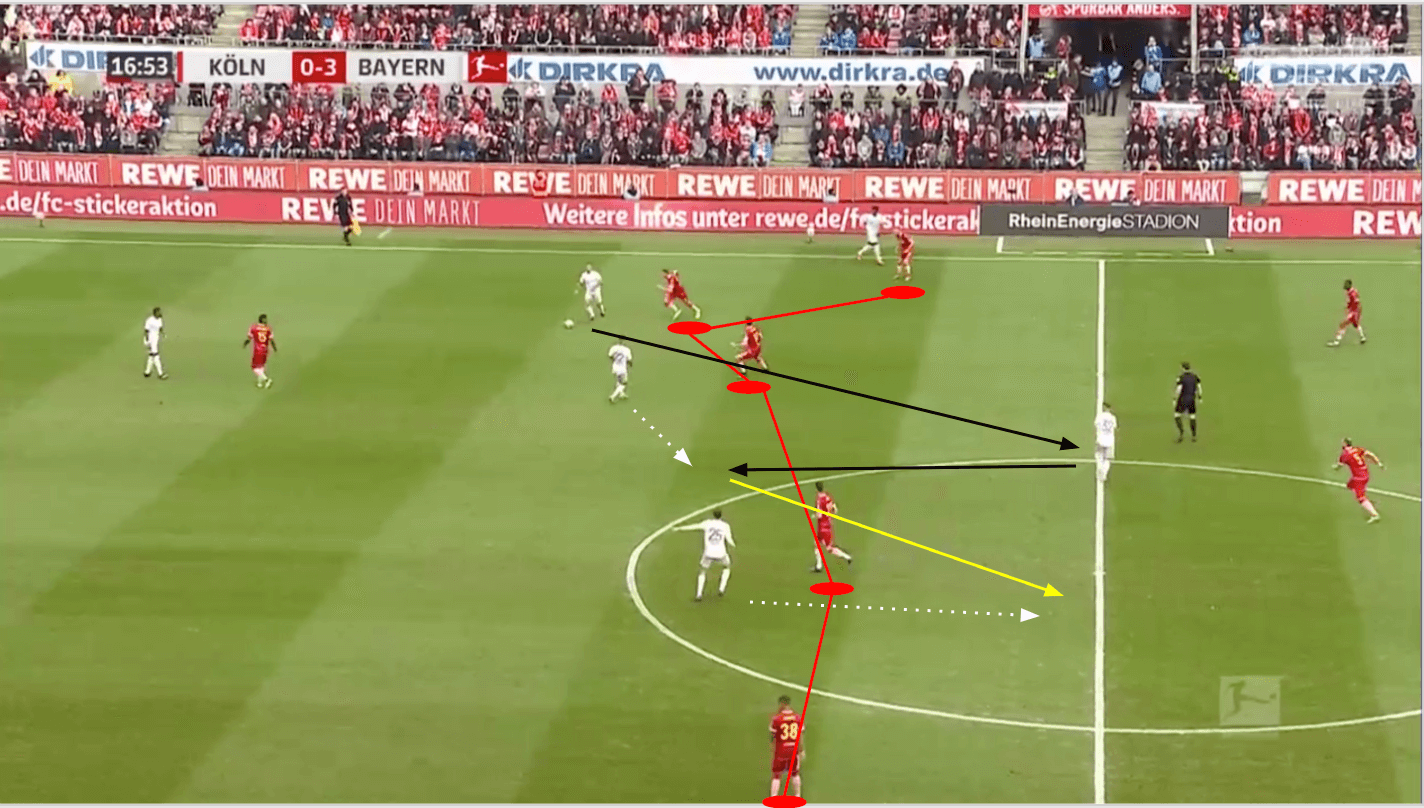

After already passing a line of pressure, Thiago, who was on the ball, was faced with a Köln midfield of five. Luckily, Joshua Kimmich and Serge Gnabry had rotated positions, so Kimmich was positioned in a passing lane behind the line of pressure. When he received the pass, he attracted a lot of pressure from Köln, and was able to play to Gnabry, who had positioned himself appropriately. The next step of this includes Thomas Müller, who executed the third man concept perfectly. Kimmich was unable to directly play him the ball, but Müller positioned himself perfectly to be able to receive it from Gnabry. Unfortunately, Kimmich’s pass went to Gnabry’s front foot, and he was unable to play to Müller, who was open in space. The combination of player rotations to achieve positional superiority combined with numerical superiority still allowed Bayern to progress up the pitch, as Gnabry played the ball back to Kimmich who was then in a better position to find Müller in space.

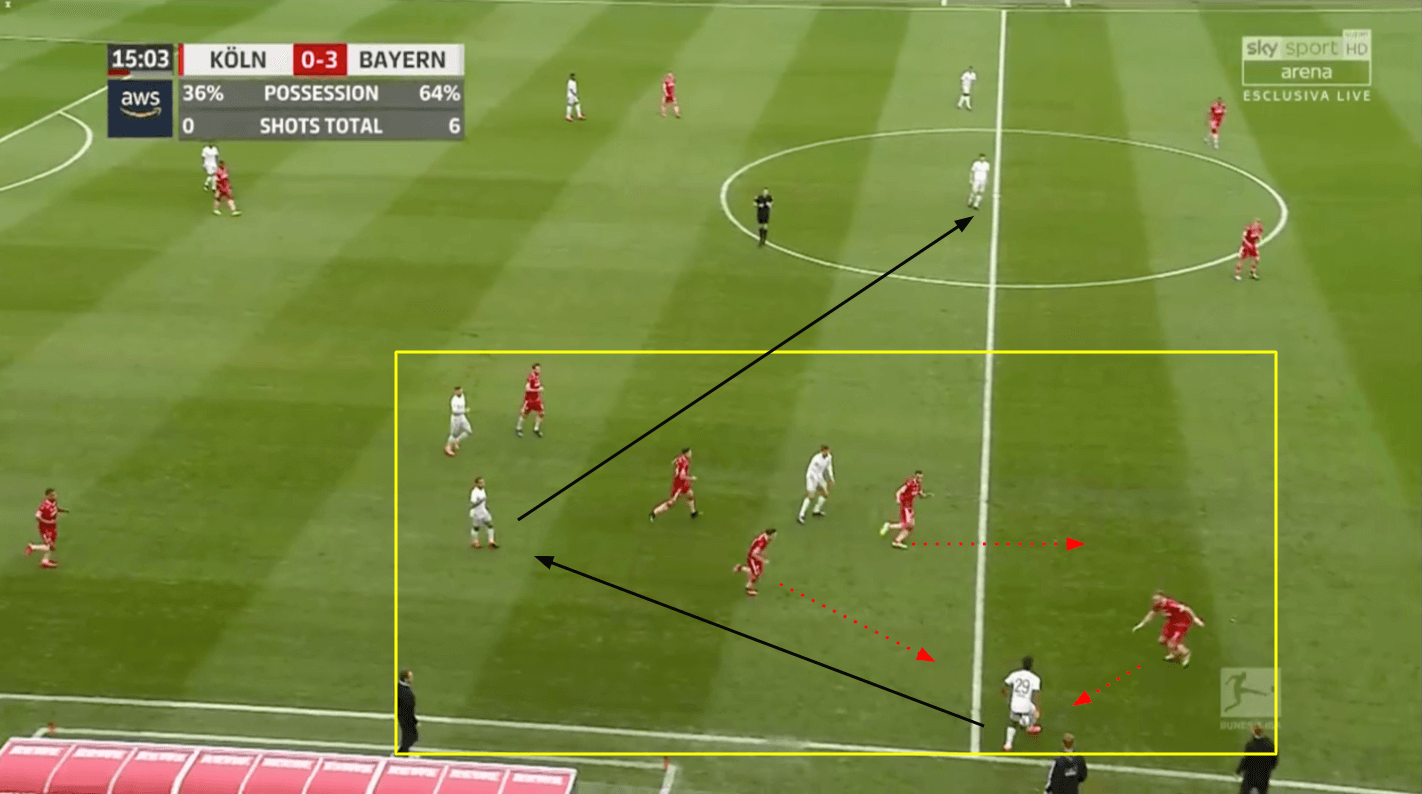

Bayern can also manipulate the opponent by attracting large numbers of them into one area, before taking advantage of a qualitative superiority on the other side of the pitch. Looking at the scoreline and the time of the match, it’s clear Köln had to press in order to try and create something for themselves.

Köln did well to force Bayern to build up through their wings, but once there, they struggled to effectively win the ball back. Here, Bayern has done well to attract defensive pressure, being outnumbered 5 to 4. However, because of Thiago’s excellent individual positioning, he was able to provide an angle of support while also picking out the qualitative superiority of Robert Lewandowski and Gnabry both being marked individually. Kingsley Coman was unable to progress forward, so he played the ball back to Thiago who got Bayern out of pressure. Bayern was unable to take advantage of the qualitative superiority because Lewandowski turned towards his own goal when receiving the ball and then proceeded to play a pass behind Gnabry.

While certainly not all-inclusive, Bayern’s consistent implementation of these principles in their build-up allow them to force teams back into their own halves, where they spend much of the time defending wave after wave of Bayern’s attacks.

Establishing positional superiority in opponent’s half

Some of the challenges that come with opponents trying to park the bus are that it can become incredibly frustrating to break teams down who are well-organized defensively. Breaking them down becomes more achievable when Bayern properly apply the aforementioned positional play principles.

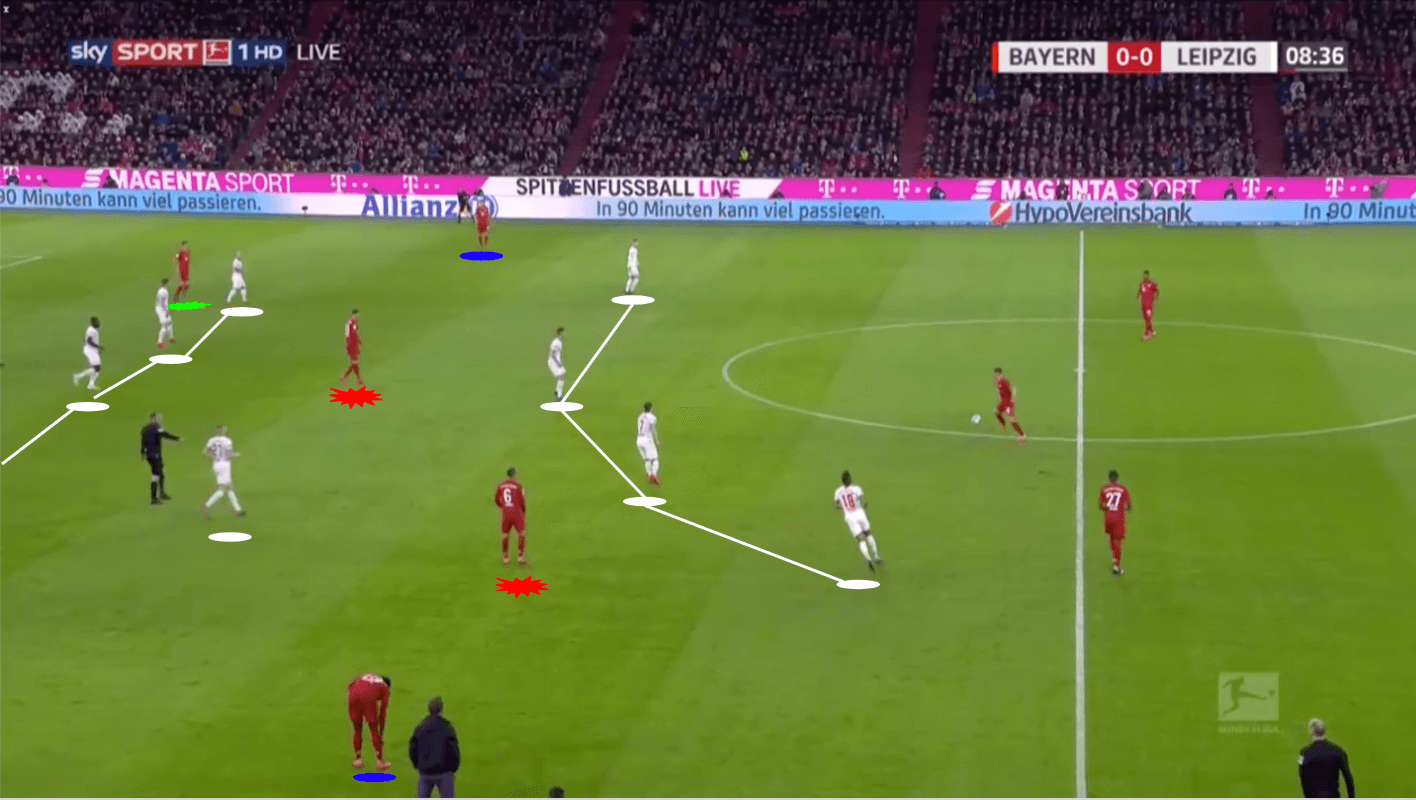

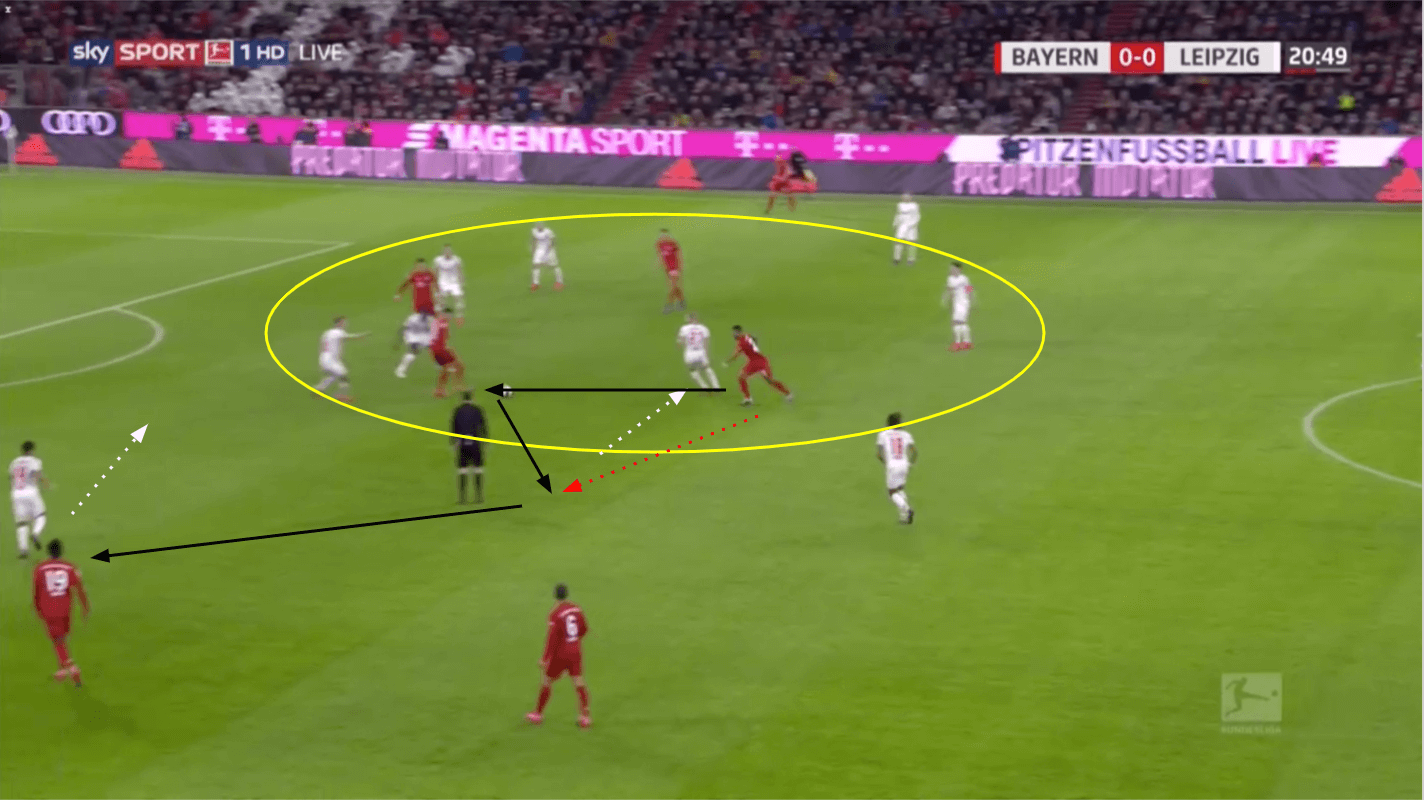

Against RB Leipzig, a team that actually pressed Bayern quite well, Bayern still saw most of the possession and looked to spread Leipzig out defensively by applying multiple principles of positional play. The defensive lines of pressure are marked accordingly, with Konrad Laimer between the lines, trying to negate Bayern’s tactics. The man marked with green, Müller, was behind the defensive line, attempting to draw Leipzig players back by causing some confusion about his location; Gnabry was doing the same in the half-space on the other side but is out of shot. These players don’t permanently position themselves there, but rather use it as an opportunity to draw the attention of defenders. Their positioning in between defenders in the half-space attempts to create confusion amongst defenders about who is responsible for marking their movement. The outside-backs, Benjamin Pavard and Alphonso Davies, are marked with blue. Because the wingers are tucked into the half-space, the width must be provided by the two outside-backs who were looking to widen Leipzig’s defensive lines in order to create more passing lanes centrally. Finally, Thiago and Leon Goretzka, both marked with red, were the men between the lines of pressure, looking to receive a pass with proper body positioning to allow them to progress forward. The positioning demonstrated by Bayern Munich is essentially their starting position from which they look to build their attacks.

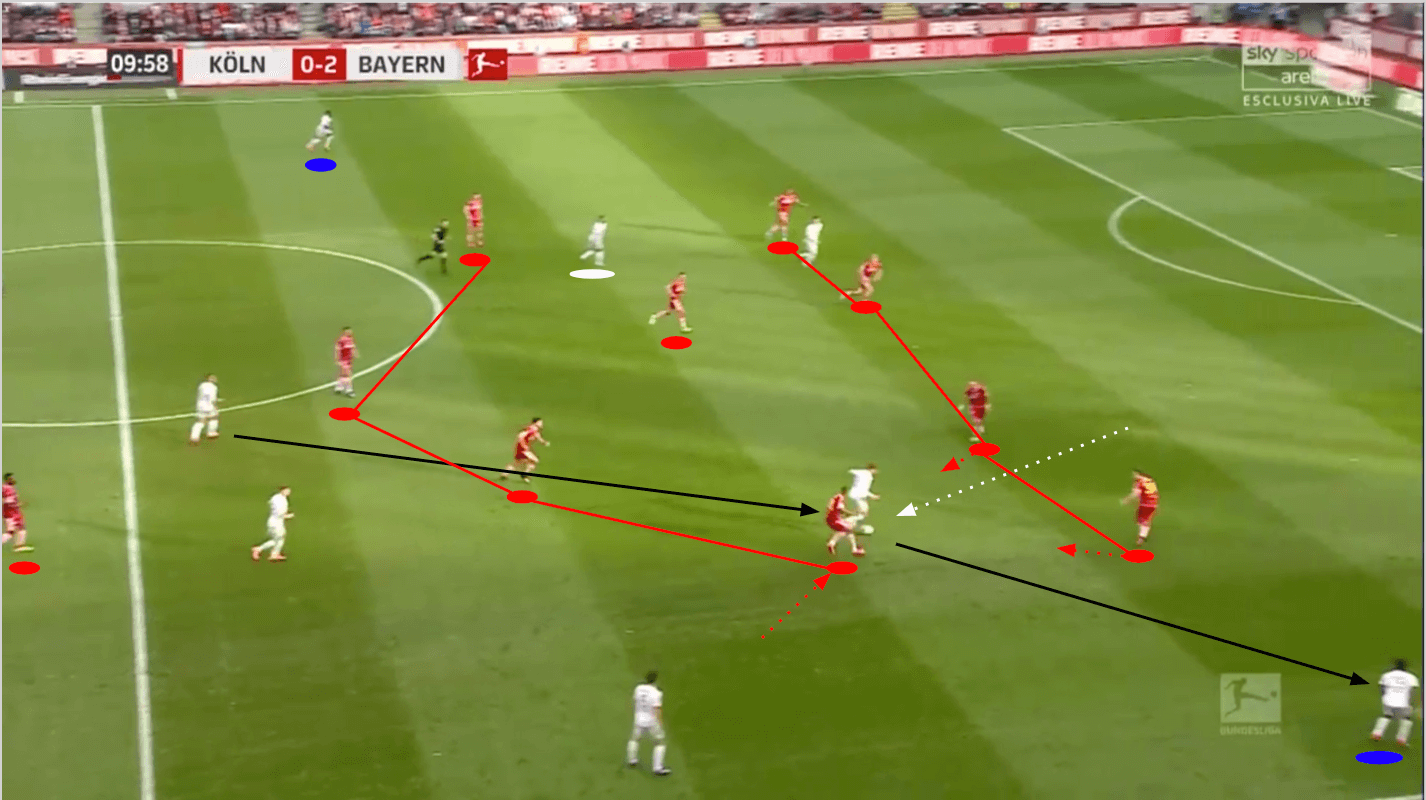

At times, Kimmich and Thiago drop down together as a double pivot in order to progress the ball forward. Bayern still apply the positional play principles successfully; it just looks slightly different.

In the previous image, Davies and Coman, marked in blue, were the ones tasked with providing width, with Pavard moving towards the centre of the pitch to provide an angle of support for both Kimmich and Coman. While they only have one man positioned between the line to start (Gnabry in white), Müller, who started his run from an offside position to again cause confusion, was able to check into the half-space. He received the ball on the half-turn, allowing him to have his first touch take him towards goal. This attracted pressure from the Köln defenders, allowing Müller to play Coman through into a situation of qualitative superiority as Coman’s defender had to rush to get into proper defensive positioning. When teams like Köln have moments of defensive disorganization and are not as organized as Leipzig, who earned a 0-0 draw at the Allianz Arena, Bayern uses their positional play to decimate teams. At the time of writing, under Hansi Flick, Bayern has scored three or more goals on 12 occasions, which is exactly half of their matches with Flick at the helm.

Manipulation of the opponent’s defensive shape

When teams are able to organize themselves defensively, Bayern look to overwhelm them by drawing them into a smaller area of space in order to exploit larger areas of space somewhere else on the pitch. One of their textbook movements led to their first goal against Köln earlier in the season.

Off of a short throw-in, Bayern attracts a total of four defenders with just three of their players. As Lewandowski played the ball back to Alaba who had rotated positionally from centre-back into a position to have to take the throw-in, another Köln defender joined to put Bayern under pressure. This now meant five Köln players were committed to this tight space, which became a problem when they didn’t win the ball. Müller, marked with the white circle, began to drift away from his defender into space as Alaba played the ball to Thiago, completing his third man run. As Thiago opened his hips towards the centre of the pitch, Lewandowski began his third man run into the large gap in Köln’s backline. Müller was able to slot the ball through to him with Lewandowski slamming it into the top netting.

Bayern is also capable of doing this in the centre of the pitch. This causes the opponent to collapse to protect the centre, leaving them vulnerable to attacks from the flanks from players like Alphonso Davies.

Looking at the image, it’s clear that Bayern has manipulated their opponent. The number of men in that space provides a numerical superiority to RB Leipzig (6v4), but because of Bayern’s positional superiority (and to some degree, qualitative superiority), they were able to continue to possess the ball. Gnabry received the ball as the man between the lines of defensive pressure. He took one touch forward, attracting the attention of Konrad Laimer. Gnabry then played a simple 1-2 pass with Goretzka in order to attack the space Laimer had just vacated. Tyler Adams, the Leipzig right wing-back, was forced to follow the compact movement and ‘tuck-in’ centrally, leaving Davies wide open in an incredibly dangerous position. Luckily for Leipzig, Gnabry’s pass was overhit and forced Davies to go away from goal, although he was still able to cross the ball. The result of the manipulation of their opponents often allows Bayern to take advantage of qualitative superiority.

Manipulation of the opponent creates qualitative superiority

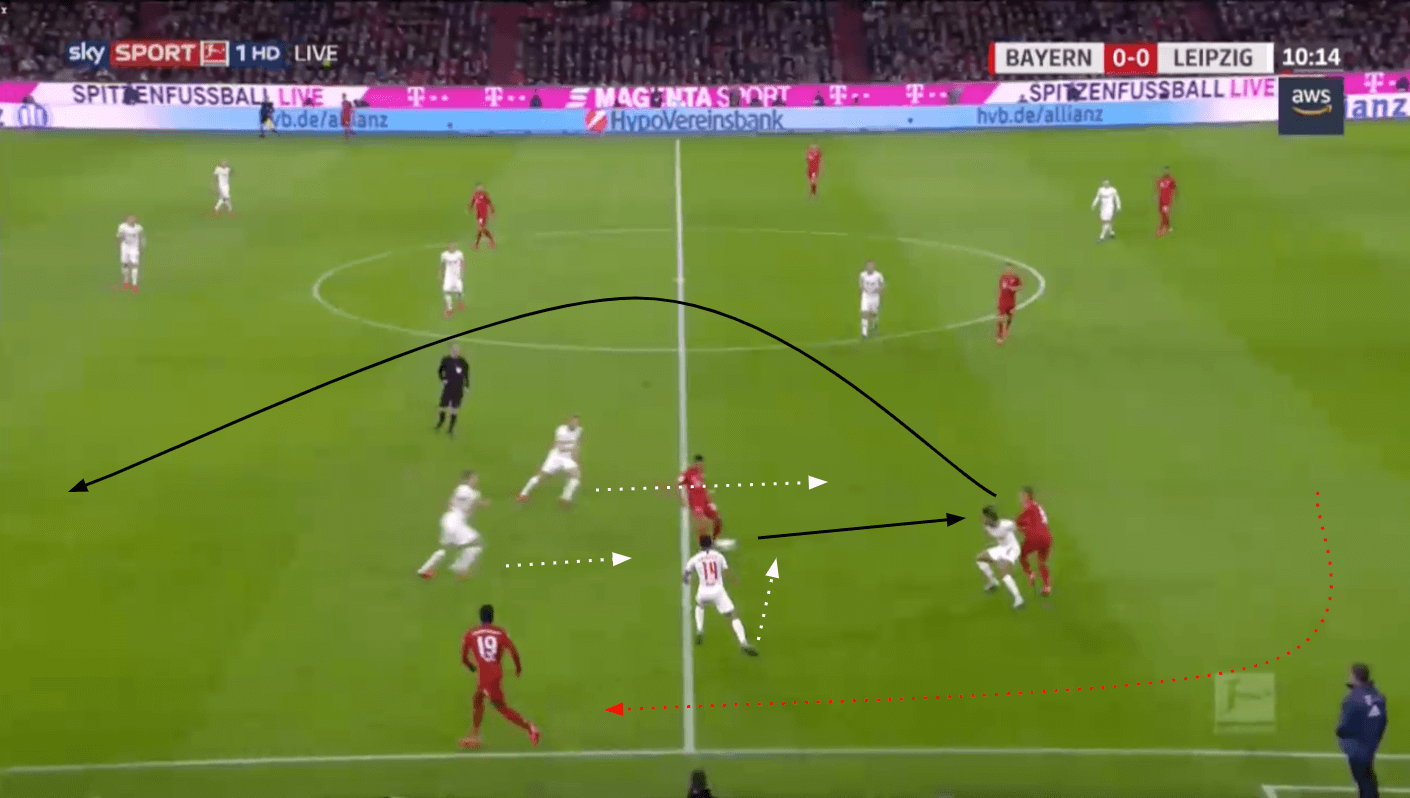

Many times, Bayern look to take advantage of qualitative superiorities on their wings. On the left side especially, Alphonso Davies has flourished as an attacking full-back under Flick. While starting his journey as a left-back under former Bayern boss Niko Kovač, Davies has demonstrated his attacking prowess most consistently in Flick’s set-up.

Against Leipzig, Bayern looked to take advantage of Davies’ superiority on multiple occasions. One example occurred early in the first half, which saw Leipzig get lucky to not concede.

Bayern’s positional balance was on display as Davies rotated positions first with Thiago, who dropped down to receive the pass from Alaba. Gnabry then dropped down more centrally, allowing Davies to progress forward and rotate positionally as well. Thiago played a quick 1-2 with Gnabry, drawing the attention of four Leipzig defenders, including Tyler Adams, who should have been marking Davies. Thiago quickly played Davies into space, leaving Davies 1v1 with Dayot Upamecano in a large amount of space. Upamecano is a highly-rated defender, but Davies turned this into a foot race and absolutely blew past Upamecano, fizzing the ball across the six-yard box, with two Bayern attackers missing the driven cross.

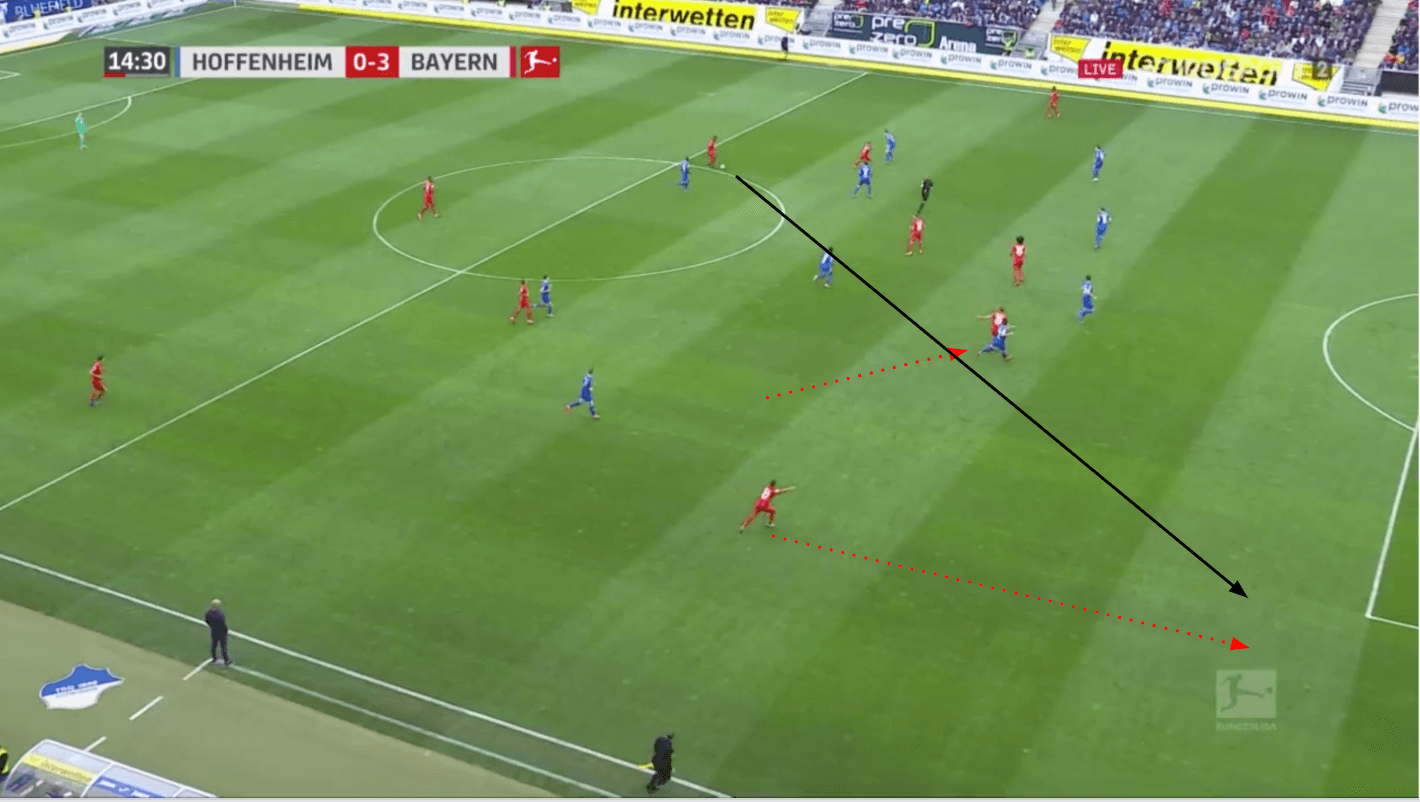

Bayern also look to take advantage of qualitative superiorities on the right wing, regardless of the personnel. By properly manipulating the opponent, they can create qualitative superiority due to an opponent’s rushed arrival into a 1v1 situation.

Bayern started this move off by switching the ball from right to left with their centre-backs. Alaba then dribbled for four seconds, allowing Hoffenheim adequate time to shift over. Müller began his run halfway through Alaba’s patient dribbling, dragging his defender with him. Gnabry, on the right side this time, was providing the width. The qualitative superiority comes into play when considering how much area Hoffenheim’s left-back had to cover in order to properly defend Gnabry. The defender was unable to get close enough to Gnabry without leaving lots of space behind him. Gnabry crossed the ball into the box where two Bayern attackers had a numerical advantage over the one centre-back marking them. Translation: goal.

Conclusion

While this article certainly doesn’t address all of Bayern Munich’s changes under Hansi Flick, it certainly becomes clear that the elements of positional play that he has incorporated into his team have made them a much stronger version of themselves. In just about half of a season, Bayern went from a team in crisis under Niko Kovač to a favourite to win the UEFA Champions League. What Flick has done in his first seven months in charge has been most impressive. If he continues to add to his game model and develop his squad even more, Bayern Munich will be a terror to both the Bundesliga and the Champions League for years to come.

Comments