Should bad teams playing good teams take risks in pursuit of a win, or play it safe and hope for a good outcome? An enduring question for managers of perennial underdogs, we, i.e. Jordan Urban, a student at Cambridge University, and I, decided to look into it through the lens of a specific strategic decision: whether to play out the back and engage in intricate passing football in your own defensive area against superior

opposition, or to play it in more stereotypically ‘safe’ ways, with either long aerial balls (‘hoofs’) directed towards the striker or quick transitions out of the defensive area via direct forward passes through the midfield.

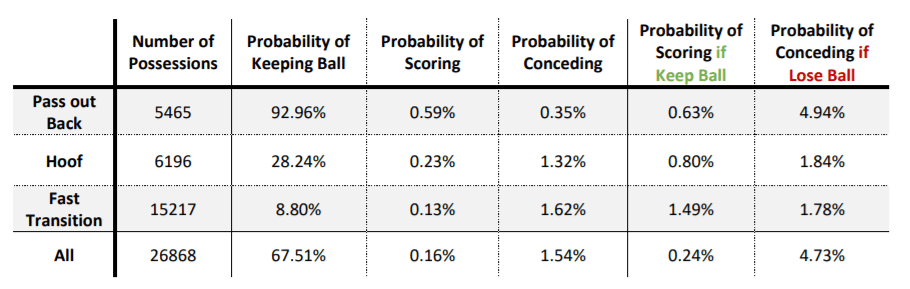

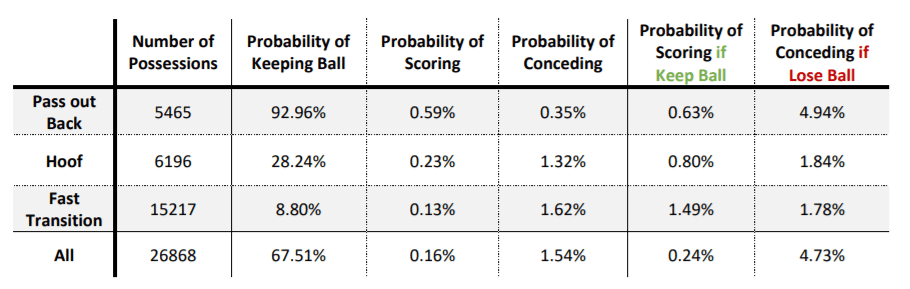

To simplify the mathematical process – and because it was the only suitable data freely available! – we decided to study games where an underdog played FC Barcelona, the quintessential example of a top-class team over the past two decades. Using Statsbomb data on La Liga matches, we filtered each possession starting in the opposing team’s own third into three categories: passing out the back (three successive passes in their own third), hoofing it up (a long aerial pass), and the remainder (typically flat transition passes to advancing fullbacks or midfielders).

We then considered both the success rate of these types of play, and the potential negative consequences of losing the ball, with the crucial question being whether Barcelona went on to score as a direct consequence of the underdog’s choice. Finally, we tackled the overriding

question of whether any of these strategies significantly helps teams get a result off Barcelona; when a team either focused or avoided such a strategy (with a particularly high, resp. low, percentage of considered possessions played in this way), what result did they achieve?

Our results were instructive and largely intuitive. On the top line, passing out the back had a 93% ball retention rate, in comparison to a 28% rate for long balls and a tiny 8.8% for fast transitions. Anyone who has watched their team lump ball after ball towards the strikers only

to see them headed away by the opposing central defenders will see the face validity of this outcome. However, if the ball was lost, the chances of conceding a goal were a huge 4.9% for passing out the back, against 1.8% for both the long ball and fast transitions. Again, this is

intuitive. Losing the ball while passing out the back logically results in an opposition possession that begins in a dangerous area with your defenders unprepared for an attack. In the other two scenarios the danger is mitigated somewhat by the area where the ball is lost

and the time the defence has to regain or retain its defensive shape.

So passing out the back is the riskiest way of using possession in defensive areas. Is it worth the rewards? Well, in absolute terms, 0.6% of passing sequences that begun by passing out the back resulted in goals, compared to 0.2% for long balls and 0.1% for fast transitions. These

probabilities really emphasise the unique risk profile of passing out the back. The chances of keeping the ball are high, but losing the ball exposes you to a ton of avoidable danger. Noticeably – and, given that we are considering underdogs, uniquely – passing out the back

results in a higher chance of you scoring than conceding. But this is mostly driven by the high probability of keeping the ball; once the ball is actually kept, passing out the back isn’t an especially efficient way of scoring a goal.

So, is passing out the back worth it? It depends how you think. Passing out the back fits the profile of the eponymously named Taleb distribution, in which the outcome of events are usually positive, but occasionally go wrong – and when they do, go wrong spectacularly.

While a superficial reading of the raw numbers suggests that in the long-term passing out the back is the best option available – having a higher chance of scoring than conceding should mean winning games – in reality this is not the case. After all, for most of the situations above, we are dealing with very small probabilities with small differences between them, and the natural variance on a game-to-game basis means you are likely to see results inconsistent with their logic. This is especially true because when the probabilities get converted into

discrete goals, losing the ball when passing out the back often leads to a goal, but keeping the ball very rarely does.

So, given the extreme downside risk, in a single game it might make sense to go for the safer option – especially because that each team only plays Barcelona once, and so is forced to worry about game-to-game variance rather than results over a long-term aggregate.

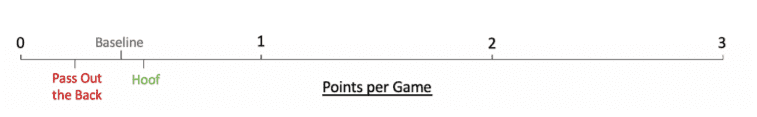

And this is exactly what we see when we consider the actual points that teams earn against Barcelona: it’s better to be safe than sorry. On average, across our dataset, the baseline figure was just 0.41 points per game – but when teams predominately passed out the back, this

dropped to a meagre 0.22 points, and when they instead played it safe and relied on the hoof’, it jumped to 0.50 points. Passing out the back isn’t worth the risks – it might seem like a good idea for the majority of the match, but it only needs to go wrong once and the opposition striker has an easy chance to score a match-defining goal.

Of course, this analysis has flaws: for one, it views tactics in isolation, ignoring that the profile and calibre of players that a team possesses will have a significant impact on their overarching strategy. Clearly, a broader dataset – such as one that allows for more scientific sorting of

quality of opposition – would be nice to have. However, we feel that not only does this study have merit, but it leaves fertile ground for further research: while our findings are only for underdogs playing against Barcelona, it may well be that our conclusion – that passing out the back is an overly risky option – is generalisable. We hope to see – or conduct – further research to test that premise.

This article was written in collaboration with Jordan Urban. Jordan is a politics student at Cambridge with a long-standing interest in football tactics, management strategies, and the psychology of success. His ambition is to become an analyst for a big European club.

Comments