When pundits of the Belgian First Division A mention the compound ‘G5’, they are referring to the five ‘biggest’ teams in Belgium football. These are Anderlecht, KRC Genk, Club Brugge, KAA Gent and Standard Liege, according to the experts.

The 2020/21 season in the Belgian First Division A is already 16 games old and the so-called ‘G5’ aren’t occupying the first five positions, as is expected from them. This caused some surprises at the top of the table. One of the teams overachieving at the moment are Beerschot.

They are the league’s most entertaining team due to scoring more goals than any other team in Belgium thus far. On the other hand, their defensive stats are not to be so proud of. Remarkable is that they also conceded the most goals thus far but still occupy a place within the three best teams in the Belgian League. Although it wasn’t Beerschot’s target to become champions at the beginning of the season or anyone’s expectation that they would do so well, their defensive performances have to improve.

This tactical analysis in the form of a scout report will take a look at the key principles and tactics Hernan Losada and Will Still apply to their Beerschot. This analysis will focus predominately on the defensive phase of Beerschot’s game with a back four.

Back to basics

In my latest analysis about Beerschot, I described their defensive issues in a back five. Most recently Losada started sending his team out in a back four formation. This consequently had an impact on their defensive organisation and dynamics. Thus so far this season, Beerschot have utilised different structures depending on the structure of their opponents but with the same intensity and principles in defence/when pressing. The purpose is to be proactive and even though they are not in control of the possession to still be able to decide/control the game by forcing opponents into the spaces they want them to play into.

In defending as a unit, Hernan Losada and William Still apply principles described by AC Milan legend Arrigo Sachi. The former Atletico Madrid manager used four reference points that when coaching his team in the defensive phase, these are also clear to see when analysing Beerschot’s shape:

– Position of the ball

– Teammate

– Opposing player

– Space

As a unit is the sum of the individuals, Beerschot also apply individual principles during the defensive phase of the game. These are:

–The conviction to always win the ball back with the initial press.

– Track the opposing receiving player and making him unable to turn in order to win the ball back through a steal or force a pass back. They also use the principle to Intercept the pass but to a lesser extent. Although intercepting the ball is cleaner and avoids making a foul which allows more fluid transitional moments.

– Covering your teammate in a ball near spaces but this can also apply to ball far spaces.

– Covering opposition player to block any passing options to their teammates.

To a certain degree, one could say that every team uses these principles when defending. But the difference to each team lies in what direction and intensity they use them. For example, current Tottenham manager José Mourinho usually sets his teams up in a low block during the defensive phase. The direction refers to the state of the block being low starting in the middle third but mostly defending in their own third. Thus the intensity in a low block is very high due to the higher aggressiveness and marking becomes tighter.

Keep in mind that the description above is the most minimal explanation about a team. Especially when we consider the 32 possible combinations can be formed from the six dimensions of a teams personality.

Beerschot statistically

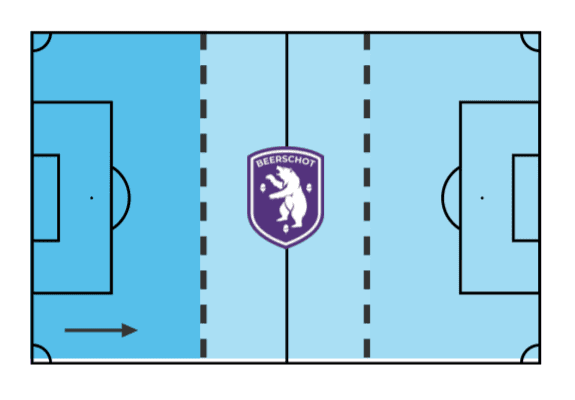

Firstly, we look at the area where Beerschot do their most recoveries. The graph below suggests that the darker an area is, the more recoveries have been made in this area. In Beerschot’s case, this is in their own defensive third. Although their initial attempt starts higher op the pitch. This clarifies that their initial pressing trap/attempt to win the ball back higher up the field isn’t really effective. We will discuss this later on.

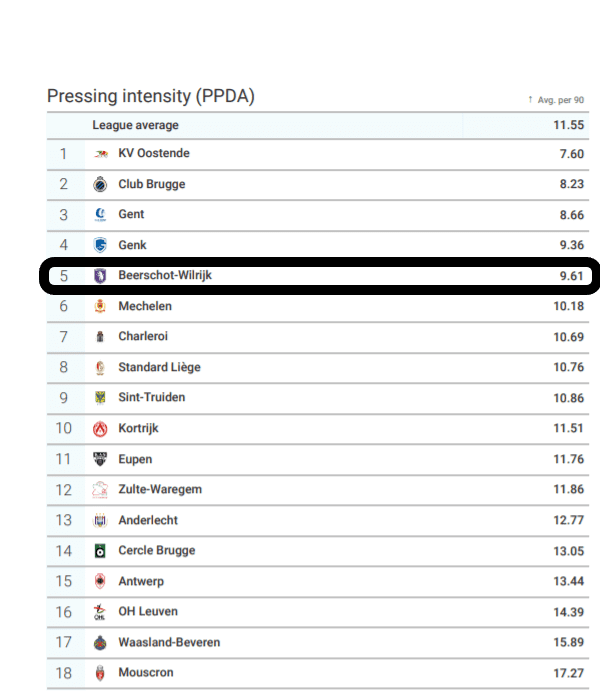

Another graph below shows us the average PPDA from every team in the Belgian League this season. PPDA measures the opponent’s passes per defensive action in the opponent’s final 60% of the pitch. A low number indicates a faster recovery. Again, Beerschot will fall back and defend deeper in a low block against teams with sustained possession. But when they lose the ball high up the pitch, their first thought is to win the ball back as soon as possible also known as counter-pressing. Note without any system in place, but relying on principles such as blocking passing lanes and pressurising the opposition with at least two players.

Beerschot use a counter-pressing system that combines pressurising the opponent whilst blocking passing lanes. The focus is to close down the opponent with the ball in order to force a mistake whilst closing off the passing options if possible. This pressure should force errors, enable the team to cover and support the first pressing player, and simultaneously absorb the nearby passing options in their cover shadow. Mostly the consequence would be a loss of the ball or the opponent kicking the ball long.

Principles during their defensive phase

As described above Beerschot use a high press after losing the ball, without a specific structure as in this moment this isn’t a priority due to the disorganization of the opponent and the opponent’s positioning being unpredictable. But during a long time without the ball, a plan based on principles has to be set.

This brings us to one of their key principles. When pressing shift to the side of the ball and stay as compact as possible without losing contact with the far side if the opponents could switch play. Consequently, a numerical superiority in this area tries to win the ball back.

The principle of compactness facilitates another principle when defending. The one of always pressing the ball carrier with at least two players. This principle is more important during the counter-pressing moments but can also be applied when defending in a structured block. In the structured block, man orientations become necessary.

Every time a vertical ball is played into Beerschot’s block, a Beerschot defender is closely following the receiver to prevent a turn. As the aim of vertical passes looks to have players deeper than the receiver, a turn isn’t necessary from the receiver. That’s where Beerschot’s man orientations in midfield come into play. BY marking the opponent’s midfielders layoffs can easily be intercepted due to their starting position, when the centre-back has the ball, being behind the opposing midfielder.

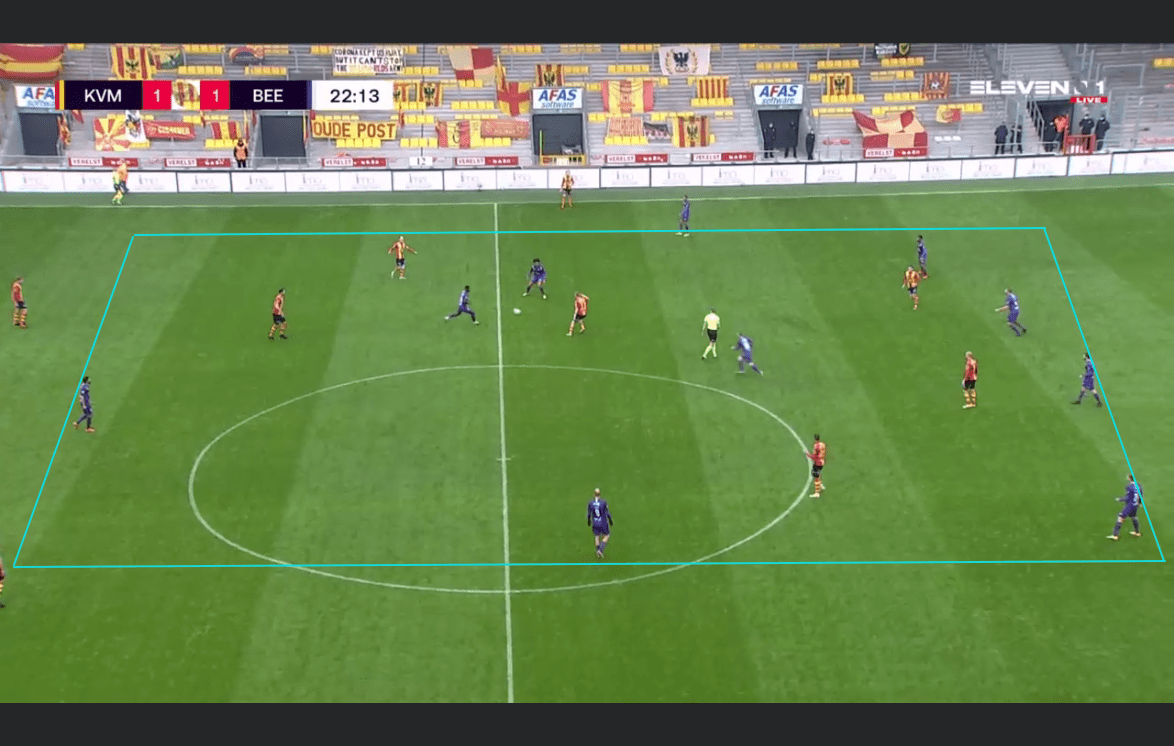

Here we can see Beerschot’s heavy midfield man-marking system. This can easily be manipulated as we will see later on.

The pressing system

Above we discussed some of the key principles Beerschot apply during the defensive phase. But in order to successfully press to win the ball back, a structure has to be set with the desire to win the ball and attack the opposing team. Thus to control where and how the opposition will play their next pass by using an efficient structure off the ball.

Beerschot use triggers to facilitate an idea of recognition of when to press the opponents. The trigger can change with regards to a specific opponent or potential ball-winning situations where players make the decision. Triggers such as a poor touch of the opponent, a bad body position, a pass from one centre-back to the other,… are opted for in regards to starting the press. This brings us to their next principle in intercepting the pass.

While the ball is travelling, the closest player to the potential pass receiver is able to ‘attack’ the opponent and thus decrease his time on the ball and potentially force him into worse situations. Also, while the ball is travelling, the closest teammate of the pressing player can close down the potential pass receiver (in the successive play) and thus decrease his distance towards the opponent but also decrease the time for the opponent to make proper decisions.

With this in mind, let’s look at Beerschot’s most common used pressing trap whilst in a 4-3-3 against a back four. A trigger several teams use but Beerschot, in particular, is after the opponents centre-back switches play to the other centre-back. Consequently, the opponent will also have less time to control the ball, prepare for and play a clean progressive pass forward. Below we can see how they perform their pressing trap. Note that this in a medium block. But we did state earlier that most of their recoveries are in the defensive third.

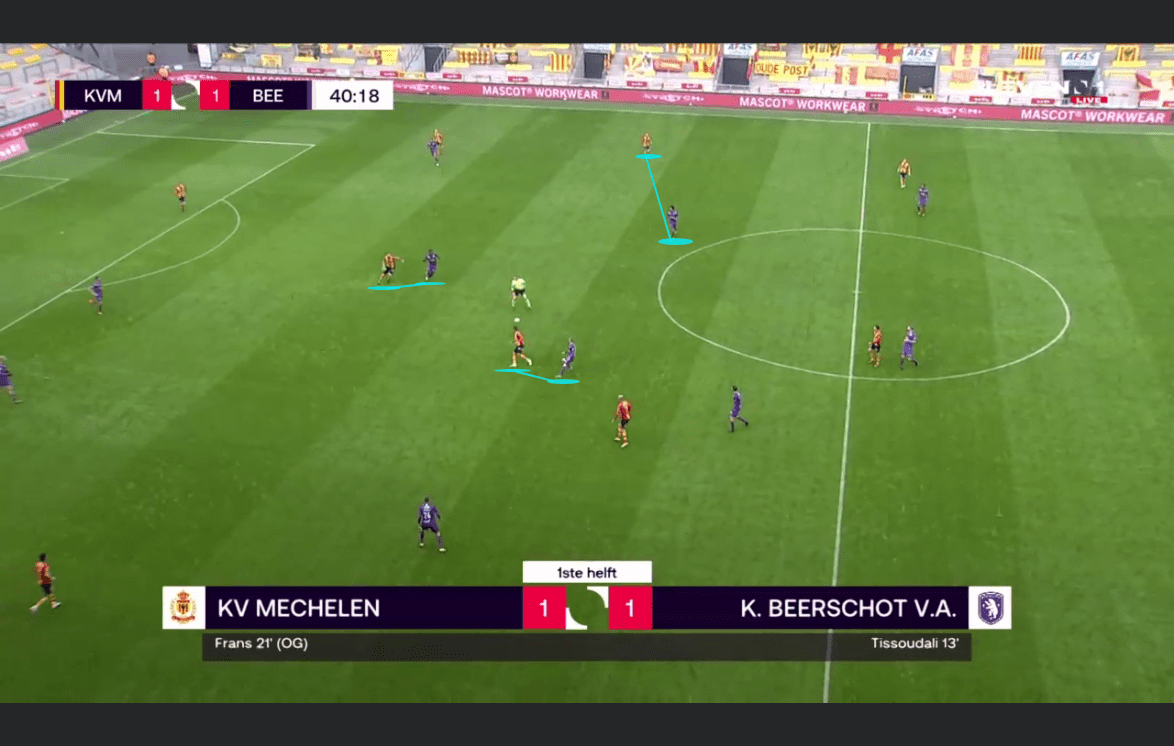

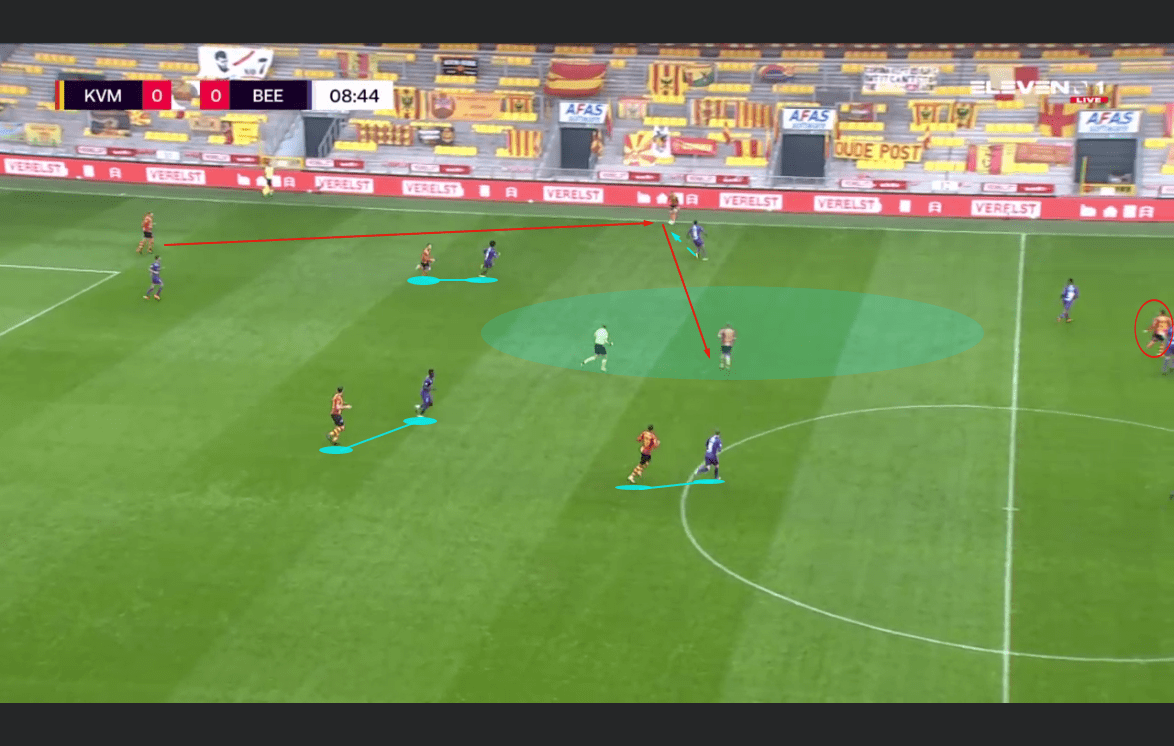

As KV Mechelen, below, have a 2vs1 situation against Beerschot’s first pressing line. Tarik Tissoudali’s role was to split the centre-back from each other using his cover-shadow, preventing horizontal switches in the back-line. This scheme occurred when Beerschot had generated enough access to do so or whenever the centre-backs moved forwards with the ball, closer to Tissoudali, who would guide Mechelen into the half-spaces and using the access to further guide Mechelen towards the touchline.

The ball far winger, Mushasi Suzuki, moves from inside, marking the ball far centre-back as well as having access to one of the opponent’s midfielders. The ball near winger, Raphael Holzhauser, shuts down any passes into the half-spaces. This forces the ball carrying centre-back to play into the full-back. But in the image below, we can see that Beerschot’s left-back is already anticipating to intercept this pass.

This idea of forcing one to the sideline was once described by Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola. He sees the touchline as the best defender. Therefore the ball is forced to the sideline. Beerschot will force the ball into the specific side zone to trap the opponent. This limits space for the opponent to cleanly play forward and only gives access to the half-space and diagonally to the outside lane. Through sharp marking and looking for the interception, Beerschot will try to win the ball in this area.

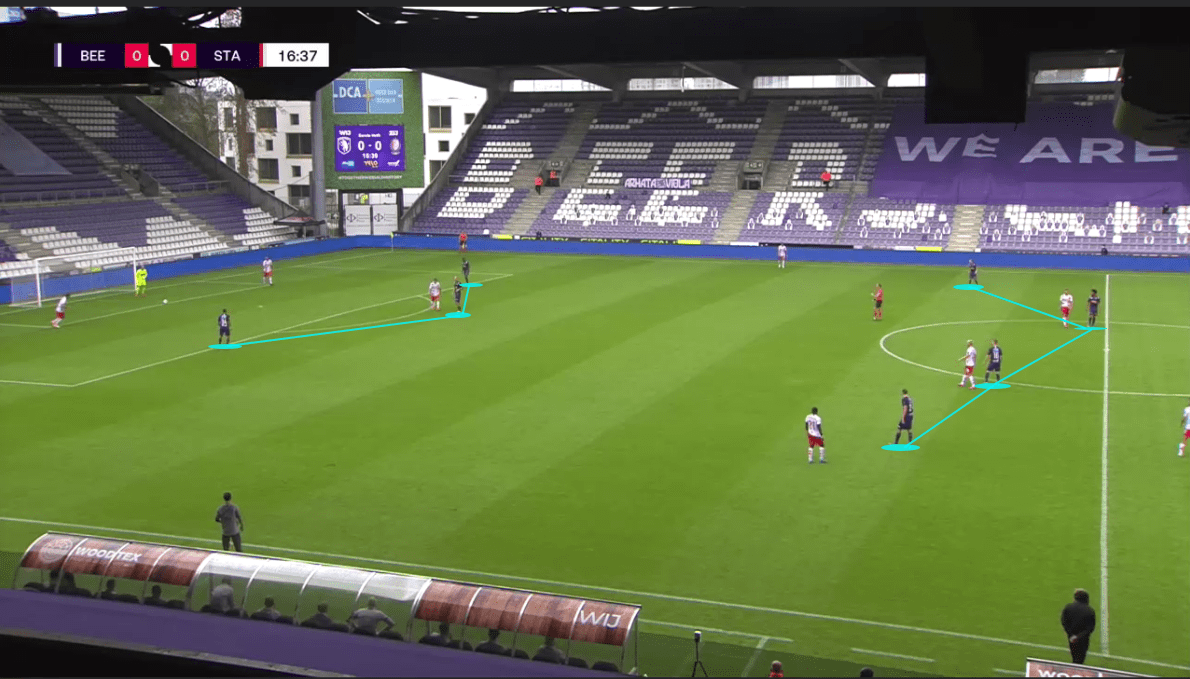

Another advantage of this press is the lower placed last line. Losada doesn’t prefer his defenders to play with a lot of space in behind. A good example where Losada was caught in two minds was against Standard Liege. Beerschot tried to press high with the front players and stay low with the defenders which created huge space in midfield. The aim is to begin pressing from deeper zones in order to defend on the front-foot/vertically and activate the ball-winning pressing approach. By lowering the defensive line they nullify any danger from runners in behind the defensive line.

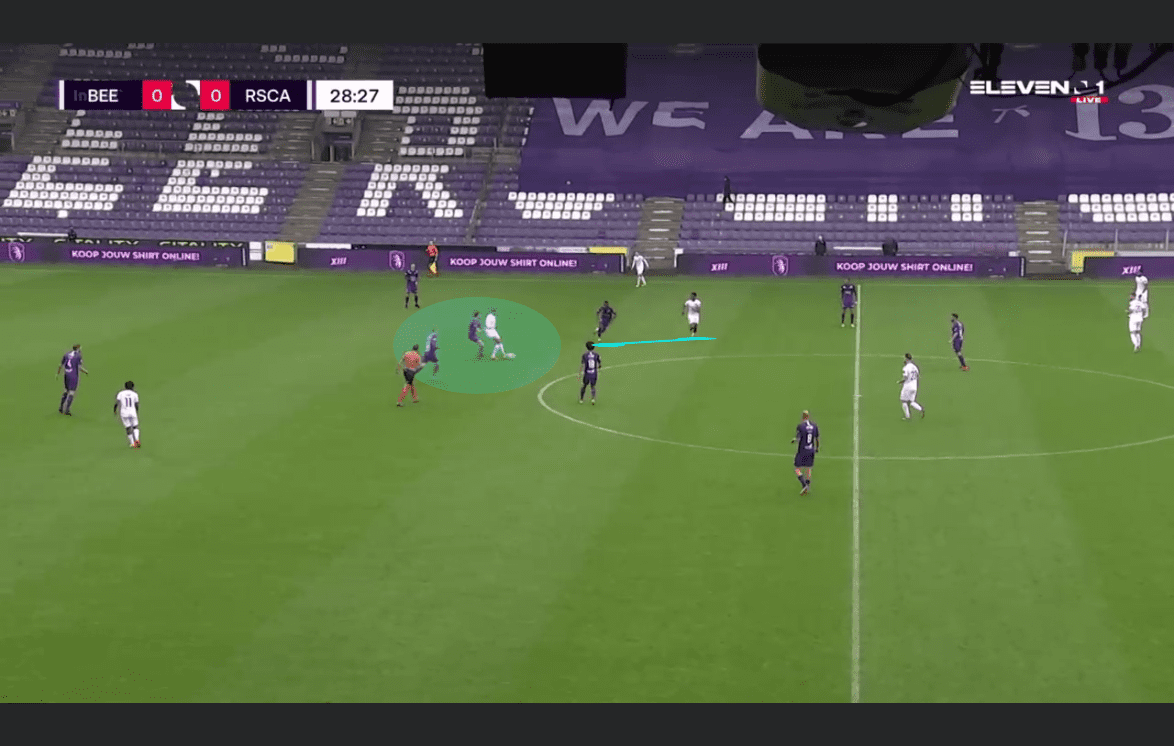

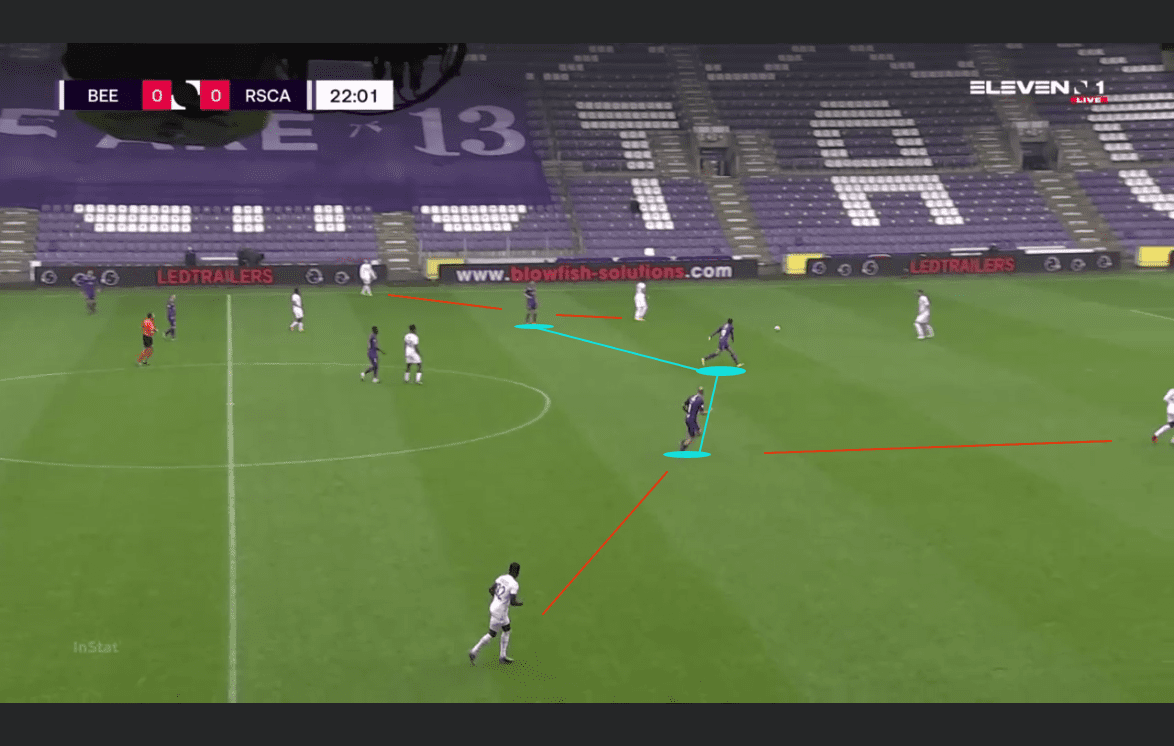

There was an exception where Beerschot tried to press in a semi-high block rather than a medium block. This was against Anderlecht due to Vincent Kompany’s side building with a back three. The positioning of the strikers are totally different. They act higher up the pitch using the principle of curved runs and blocking passing lanes from the outside centre-back to the full-back. The trigger was also different, pressing the centre-backs when they had a poor tooch, bad body position,… rather than solely forcing them to the side.

How to beat Beerschot’s structure

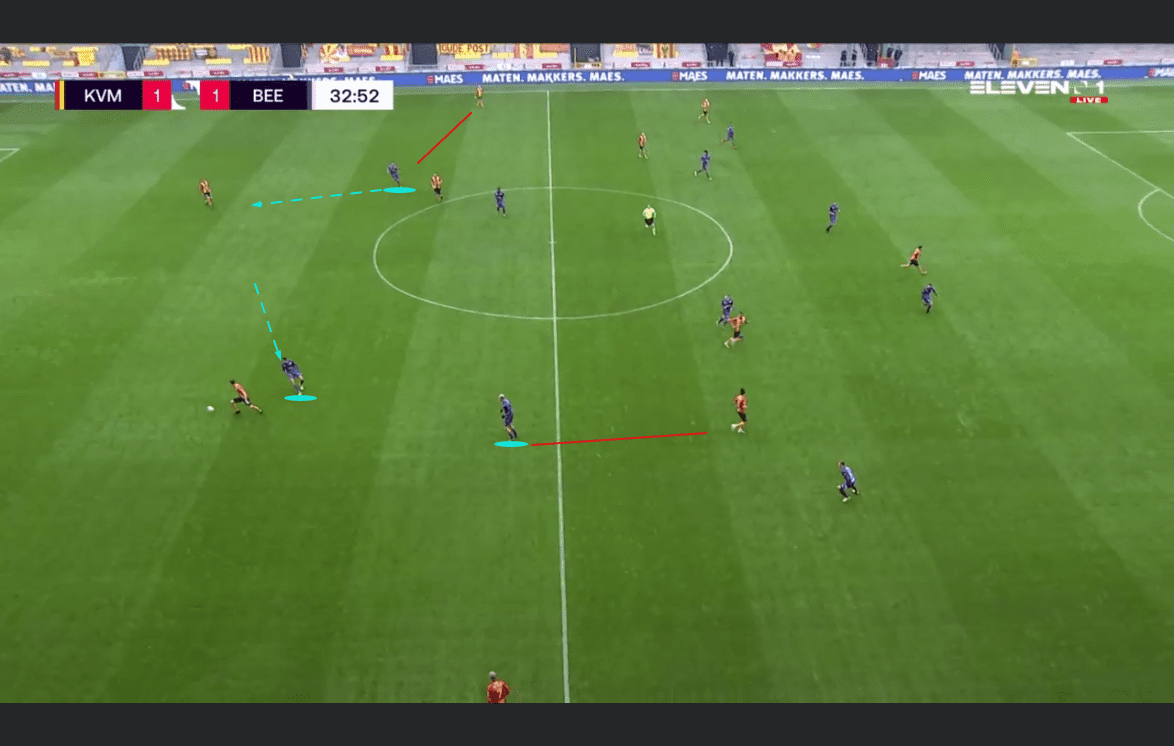

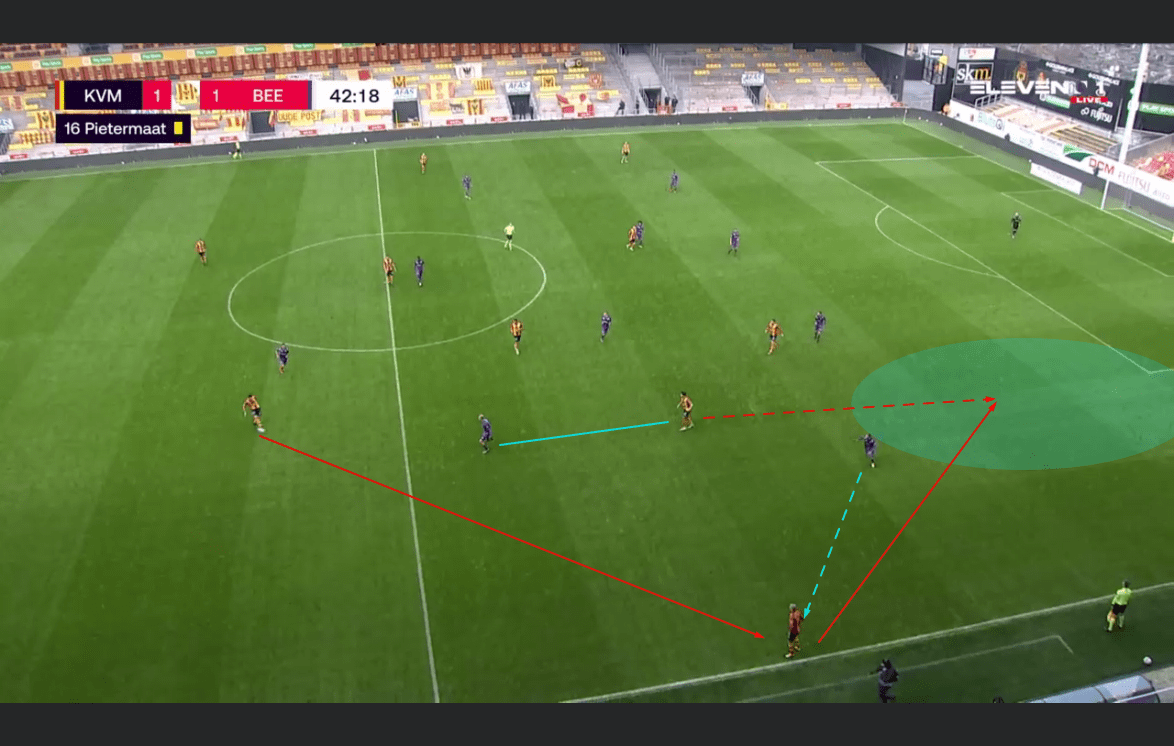

Still looking at the game Beerschot won against Mechelen. Mechelen found a way through Beerschot’s structure. Holzhauser, normally a rather passive player in the defensive phase is an easy target. As the winger only looks to close of the pass in the half-space when the ball is in front of him, Mechelen are happy to play the ball to the outside if Beerschot’s full-back isn’t quick enough to step out and press the receiving right-back. Consequently, the initially blocked attacker in the half-spaces could run onto a bounce pass in behind as Mechelen’s striker is pinning the ball near centre-back.

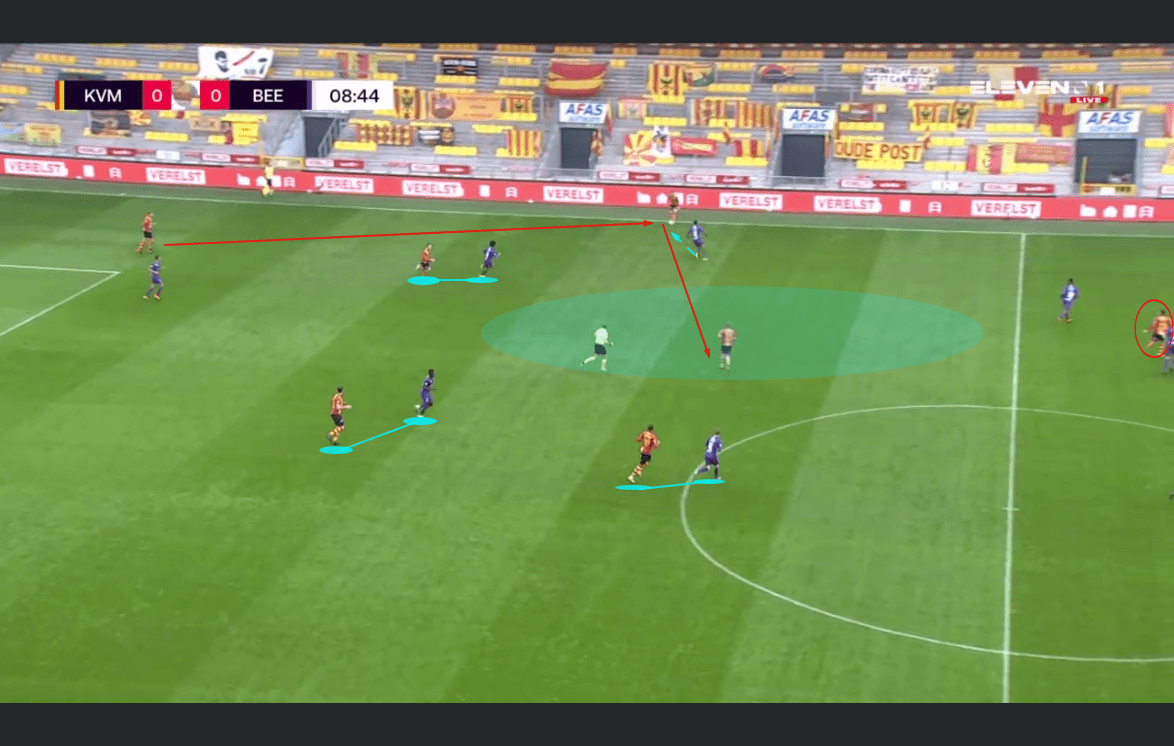

Another strategy is to overload the midfield. Due to the three midfielders marking a man, creating a box midfield could benefit in order to find the free man. Whilst KV Mechelen also use deep full-backs, the access of the Beerschot full-back to the Mechelen full-back becomes less likely. And also being pinned by the Mechelen attacker positioned between the full-back and centreback. Which means the winger Suzuki can’t prevent a pass into the free midfielder due to the 2v1 situation in the image below.

To conclude in order to break down Beerschot’s medium press, the opponent has to overload the midfield area and use wide dynamics.

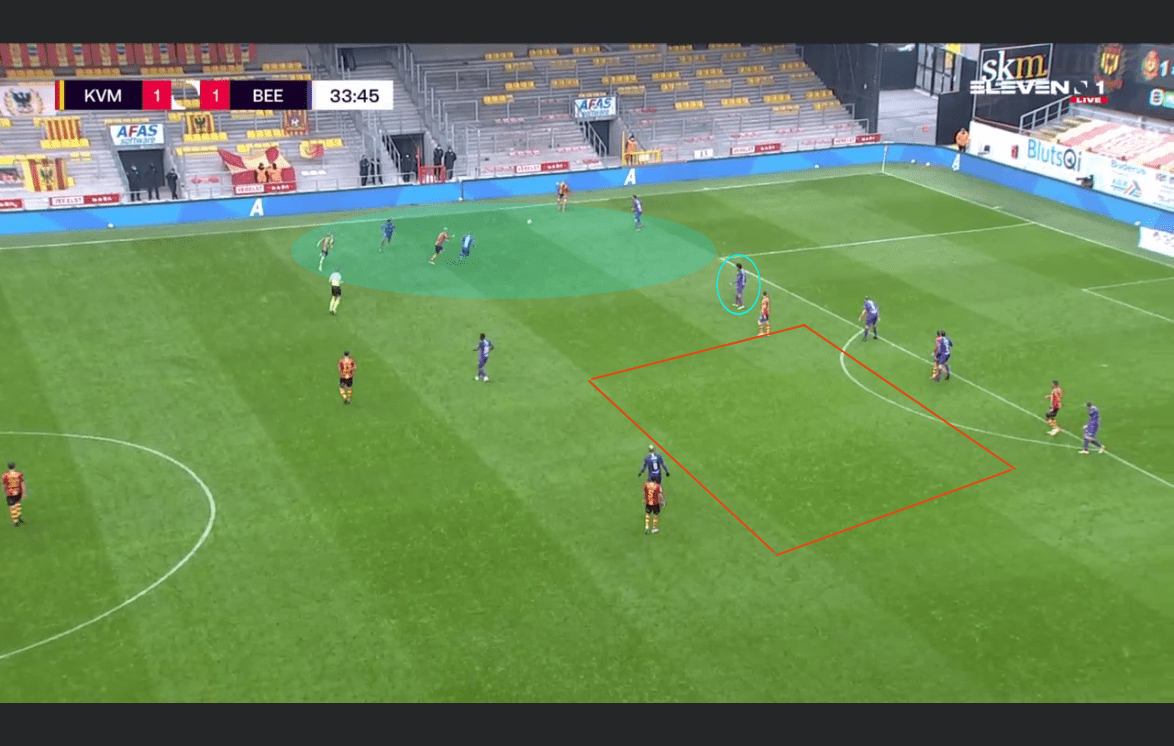

But when this happens often, this would attract Beerschot to the side and nullifying the advantage the opponent has set. As a result the opponent has not to forget the concept of in-out-in passing. The ball is played from the inside to the outside which shows in the image below. This opens the centre up. Yan Vorogovsky steps out to press the ball carrier, whilst Sanussi closes the space left, acting as a fifth defender. On the side, an equality is created to nullify a numerical superiority. But what happens is that zone 14 opens up. A simple run in behind Holzhauser could seek danger by playing the ball back inside.

The pressing game is not only used for the purpose of defending and recovering the ball. It also creates a certain control without the ball that sets up an attacking situation

Beerschot’s real problem is themselves

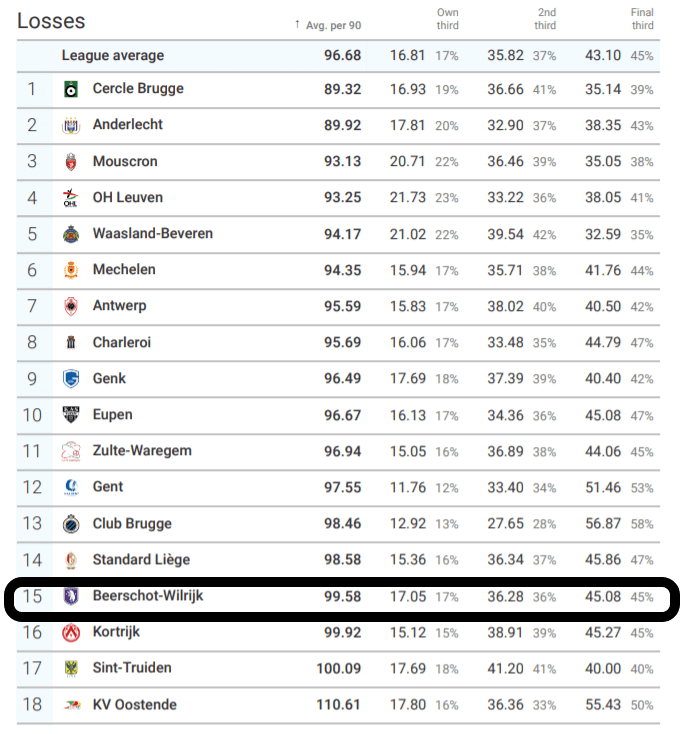

After reading the previous sections it doesn’t become clear how a well drilled team with an obvious plan concedes so much goals. The graph below looks at the total losses per 90 minutes every team makes in the Belgian League. This clarifies a lot. Beerschot are above average in every stat when it comes to losing the ball. In possession they are too sloppy which opens opportunities for the opposing team to counter.

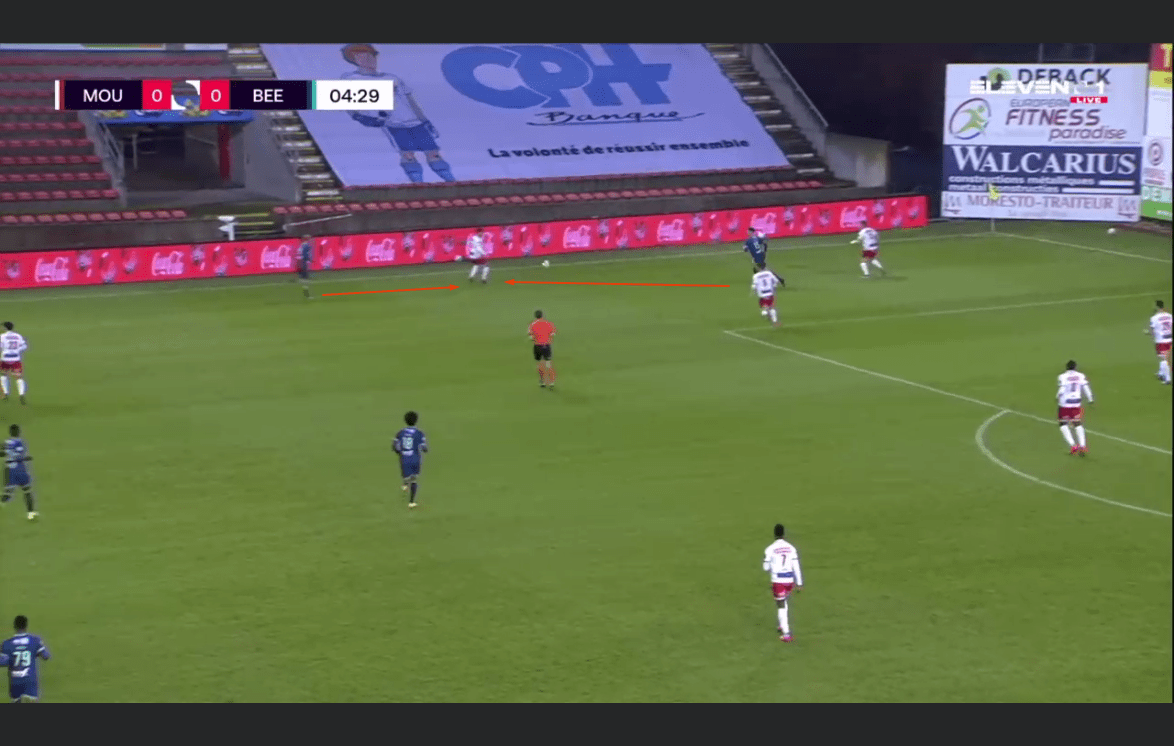

We don’t even have to do much effort to confirm the above stats. When we look at the last game against Moeskroen, we know enough. All three goals conceded were from transitional moments where Beerschot lost the ball whilst attacking and immediately got countered on.

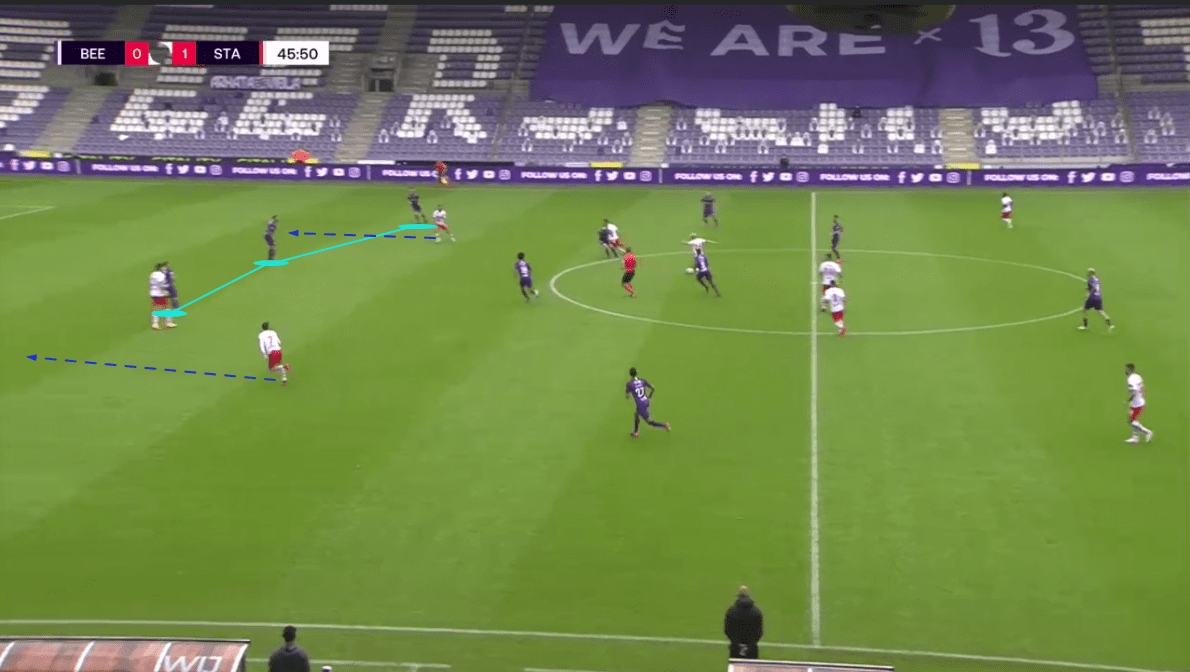

Below the situation against Standard, Once again a pass is played into an uncrowded Beerschot area which means they lose the ball far too easily. Beerschot lose the ball and are open at the back. There is no to reorganize. The distances between every centre-back is large enough to penetrate and get in behind.

Here, again, Beerschot lose the ball and therefore come into a transitional moment, running back to their own goal. This fall-back moment badly managed as no players step out during the fallback. Everybody back off until the Anderlecht striker run onto a ball in behind and scores.

The easy solution would be to stop playing so risky but who would like to see Beerschot change their entertaining style of play? Their biggest strength is at the same time their biggest weakness: playing attractive football.

But the more obvious is to solidify their current principles. Still playing risky passes but into crowded areas. By playing into crowded areas a successful counter-press is more likely as more Beerschot players are there to recover. Or even manage fallback moments with stricter marking and aggressive defending.

Conclusion

Hernan Losada and William Still are Belgium’s golden duo in terms of football managers. After promoting to the first division and performing well with attractive football, both have taken the Belgian scene by storm. Scoring the most goals in the league is impressive. If they can fix their defensive issues, who knows how far they can go this season.

Comments