Benoît Badiashile (194cm/6’4”, 75kg/165lbs) has been watched closely by those privy to what Ligue 1, European football’s self-proclaimed “league of talents”, has had on offer ever since making his senior debut for AS Monaco — his only professional club thus far, where he’s been since 2016 — back in the 2018/19 campaign, aged just 17 years old. He went on to make 20 Ligue 1 appearances, in total, for Les Monégasques that season, accumulating 1763 league minutes.

The left-footed centre-back has gone from strength to strength since then and has since established himself as a key, consistently available member of Monaco’s backline. Last season was his most prolific in terms of minutes so far in his young career, with the France U21 international making 35 league appearances under former Bayern Munich player and manager, Niko Kovač, in what was the Croatian coach’s first season in charge at Stade Louis II. The 20-year-old has remained a regular member of Kovač’s starting XI this term despite dealing with some injury issues, featuring in 14 of Monaco’s first 17 competitive games so far, accumulating 1115 minutes so far.

The Frenchman’s talent and potential is no secret. Badiashile’s name has been heavily touted as one to watch essentially since he made his Ligue 1 debut three seasons ago and the 20-year-old is notably said to have attracted heavy interest from some of Europe’s elite, including Real Madrid, Chelsea and Manchester United — the latter of whom were reportedly prepared to spend as much as €25m on Badiashile just over a year ago before allegedly getting knocked back by both the club, who according to reliable French football journalist Mohamed Bouhafsi were told they’d need to “make a Martial-like (€60m)” offer for the defender’s services, as well as the player, who later revealed he had no regrets “at all” over not moving to Manchester.

In this tactical analysis and scout report, I’ll shine a light on what exactly it is about Badiashile that has some of Europe’s top clubs so excited about him by highlighting the key strengths within his game, while I’ll also highlight the key areas in which I feel the 20-year-old must improve to justify Monaco’s “Martial-like” valuation of him. Badiashile is, undoubtedly, one of the top young homegrown talents that Ligue 1 has on offer at present and I fully back all of Europe’s top clubs in keeping a very close eye on him. However, he is still 20 years old and he’s not the finished product that he could one day develop into, which will be explained as this scout report progresses.

Passing

I feel that Badiashile’s abilities on the ball are his greatest assets; that has certainly been the case this season, with the Frenchman producing some excellent, standout performances on the ball.

Les Monégasques are a heavily possession-based team at present and Badiashile plays a key, central role in Kovač’s tactics on the ball. This term, he’s played 73.64 passes per 90 — the second-most passes played per 90 of any Ligue 1 centre-back to have played more than 200 minutes so far this season — while he’s managed to retain a 92.45% pass accuracy rate, which also ranks very well among the aforementioned centre-backs.

As well as being heavily involved in his side’s possession game, the Monaco man is, by nature, a very progressive centre-back. He’s made 1.23 progressive runs per 90 this term, which ranks fairly well amongst Ligue 1 centre-backs in that particular area and gives us an indication of how much Badiashile likes to carry the ball out from the back for his side. However, the 20-year-old primarily likes to drive his team upfield via his passing ability. This term, the Frenchman has completed a very impressive average of 13.58 progressive passes per 90 in the league — the most progressive passes of any Ligue 1 centre-back to have played at least 200 minutes so far in the 2021/22 campaign. Furthermore, Badiashile has got an equally impressive 89.77% progressive pass success rate for this season, which ranks him fourth among the Ligue 1 centre-backs with at least 200 minutes played at this point, with most teams having played 10 league games.

All of this highlights the extent to which Kovač’s side place responsibility on Badiashile in the build-up and ball progression phases, as well as the 20-year-old’s comfortability with shouldering that responsibility and acting as a very reliable ball progressor despite the heavy extent to which his team relies on him to help them break the opposition’s first one or two lines of defence.

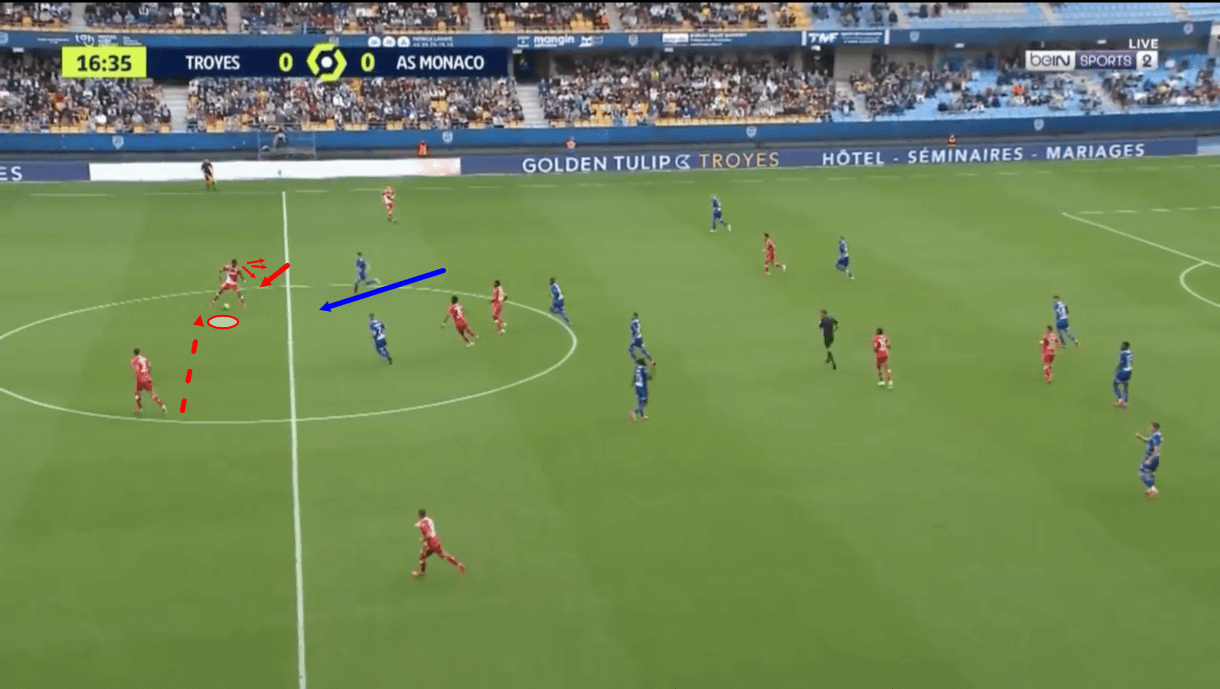

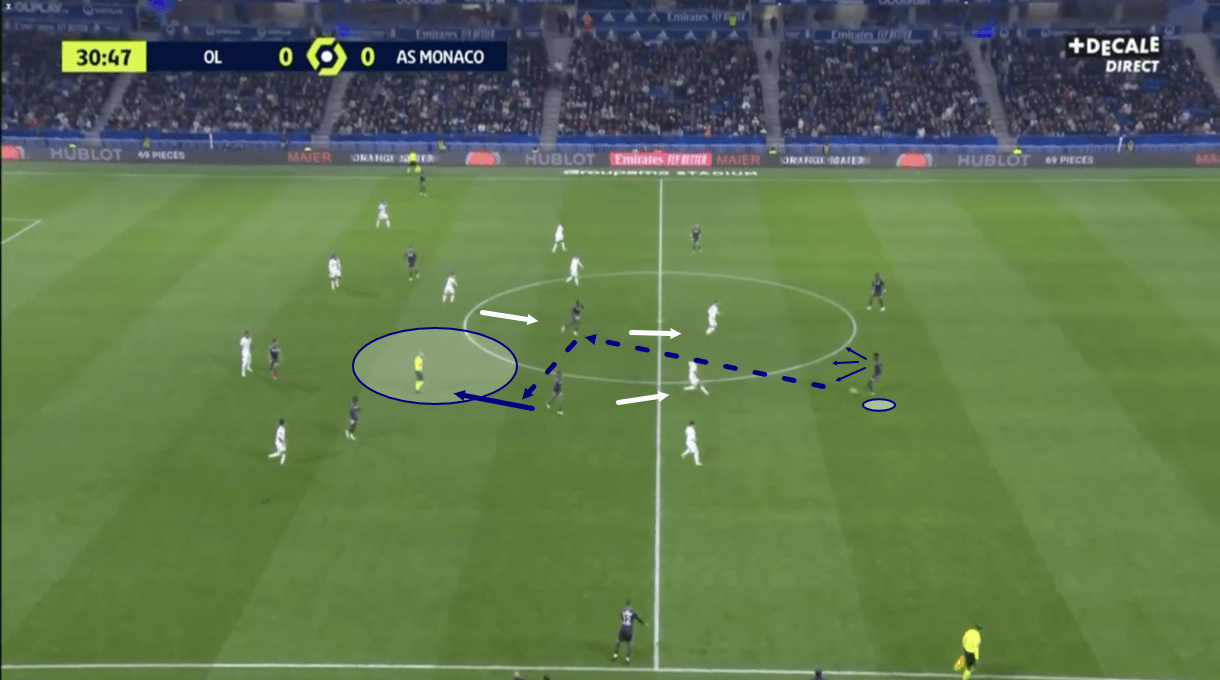

Badiashile typically occupies the left centre-back position at Stade Louis II. He’s comfortable playing on the left of a back two or a back three, with Kovač making adjustments to his tactical setup at Monaco semi-regularly and a switch from a back two to a back three, and vice versa, being part of those tactical changes at times. Figure 1 shows an example of Badiashile occupying the left centre-back position in the 4-2-3-1 shape that his team used while playing against Troyes in Ligue 1 earlier this term.

As well as just his positioning, this passage of play from figures 1 and 2 highlights a key component of Badiashile’s ball-playing quality: his composure on the ball, especially under pressure. The 20-year-old is very comfortable with attracting pressure when in possession with the hope that this leads to space opening up ahead of him for him and Monaco to exploit.

Just before figure 1, we saw Badiashile receive the ball from his central defensive teammate. The pass was played to his weaker right foot, which led to the Monaco man taking a big step back to shift the ball onto his left foot, as we can see in the image. He’s relatively comfortable with playing off his right foot when necessary, especially for short passes, but if possible to play off his left foot, Badiashile will generally try to do so to maximise the likelihood of a well-executed pass.

While taking this step back, we notice Badiashile getting his head up and scanning the options ahead of him. Badiashile is very diligent with his scanning on the ball to assess the passing options ahead of him based on players’ positioning and movement. This also helps him to assess the opposition’s positioning and give himself an idea of how much time he has before coming under serious pressure from an opposition player. The Monaco man’s tendency to scan with regularity aids his decision-making process and plays a key role in his reliability in possession.

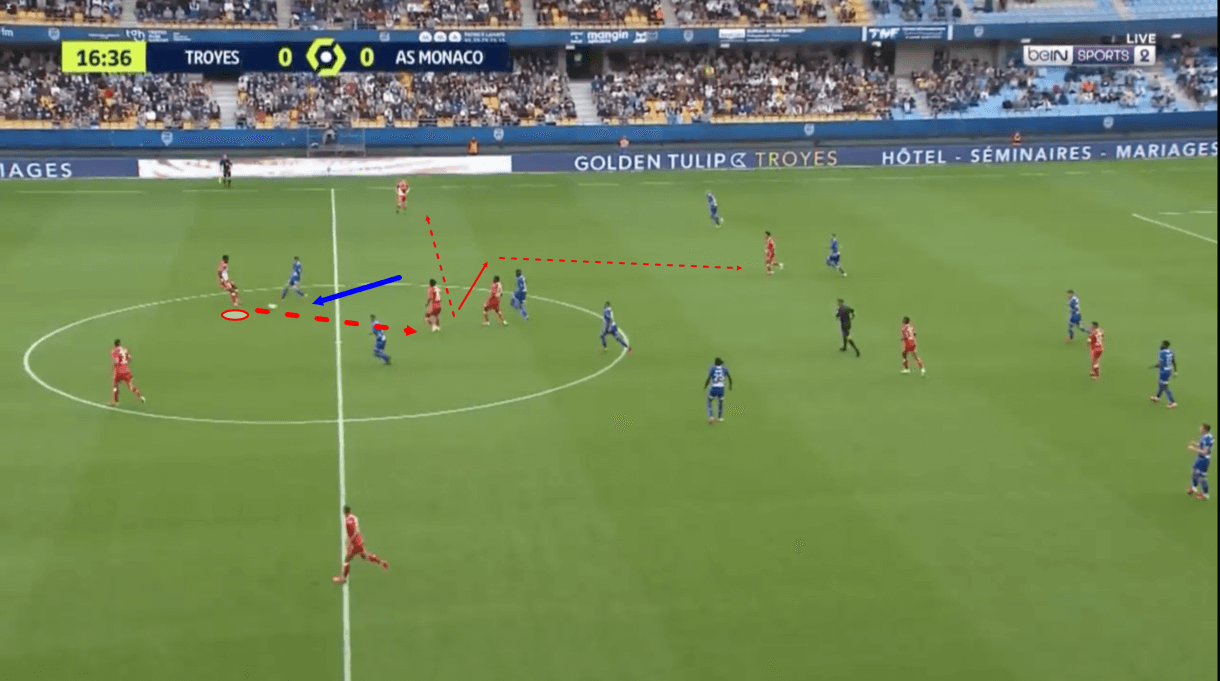

As figure 2 shows, Badiashile came under aggressive pressure just a second later but this was enough time for the centre-back to calmly assess the situation, make a decision about his next action — a short pass with his stronger left foot to a midfielder running into space behind the opposition player pressing him aggressively — and execute the resulting action from that decision very well. While some players may get put off opting for a forward passing option in a situation like this when pressure is mounting, Badiashile generally tends to think positively, which is a big part of why he’s made the most forward passes (29.64 per 90) of any centre-back to have accumulated at least 200 minutes in Ligue 1 this term.

From figure 1, when we saw the Frenchman receiving the ball, to figure 2 when we see him executing a pass of his own, he retained a positive body shape by opening himself up to the pitch ahead of him, got his head up to aide his decision-making process, remained calm and stuck to his positive plan despite incoming pressure from an opposition forward, and followed through to calmly execute an accurate pass into midfield, which ends up being placed perfectly just into the midfielder’s running path. This leaves the receiver with two options — either passing the ball out wide or taking a big first touch before knocking the ball on to the attacker in the left half-space. Regardless of that, though, Badiashile fulfilled his role in progressing the attack from Monaco’s half into midfield to provide the midfielder with those options perfectly. This is normal behaviour for him which shows his value in the early possession phases.

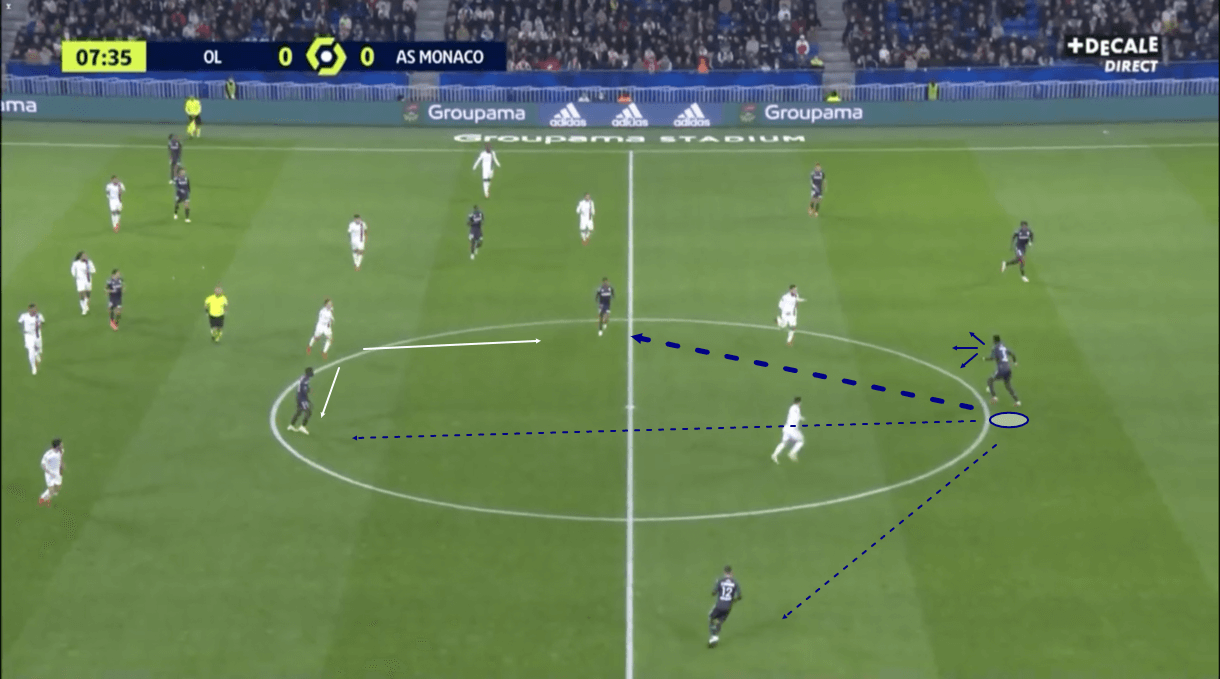

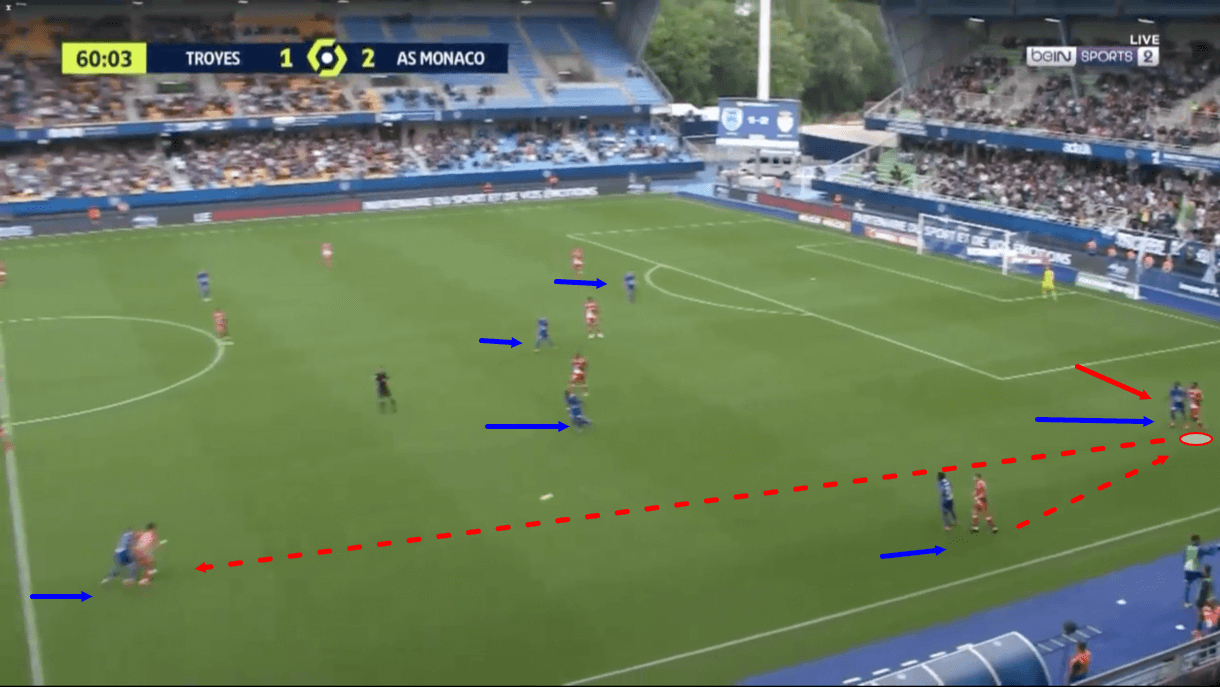

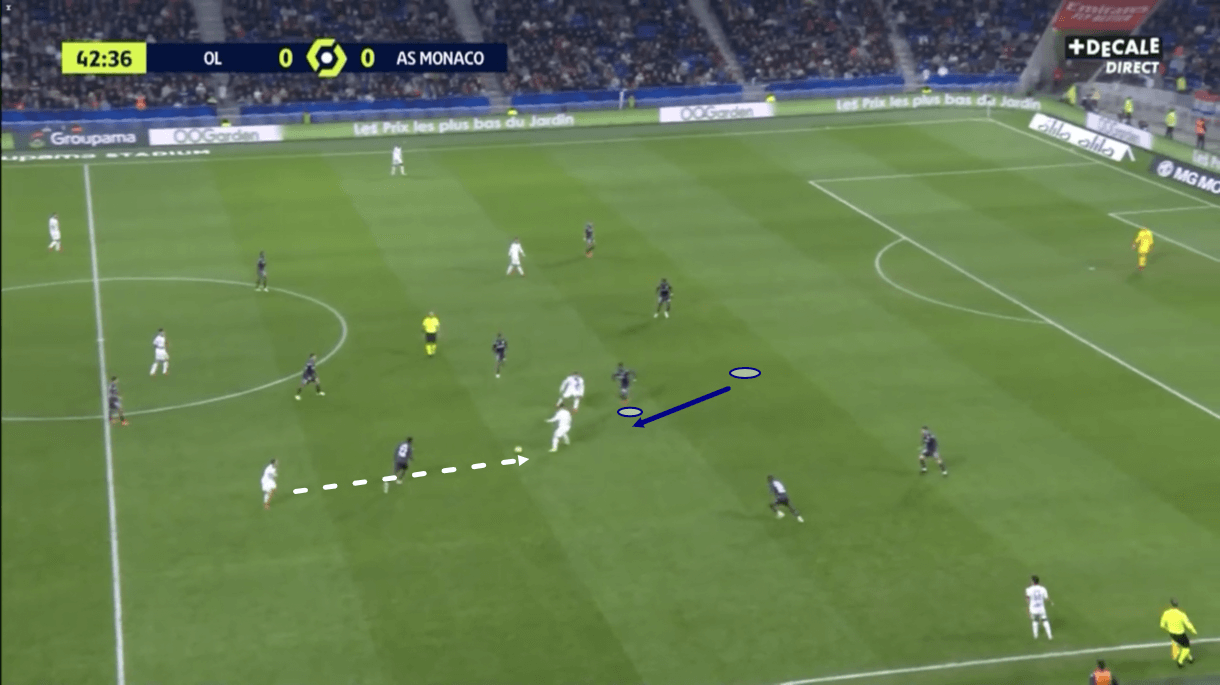

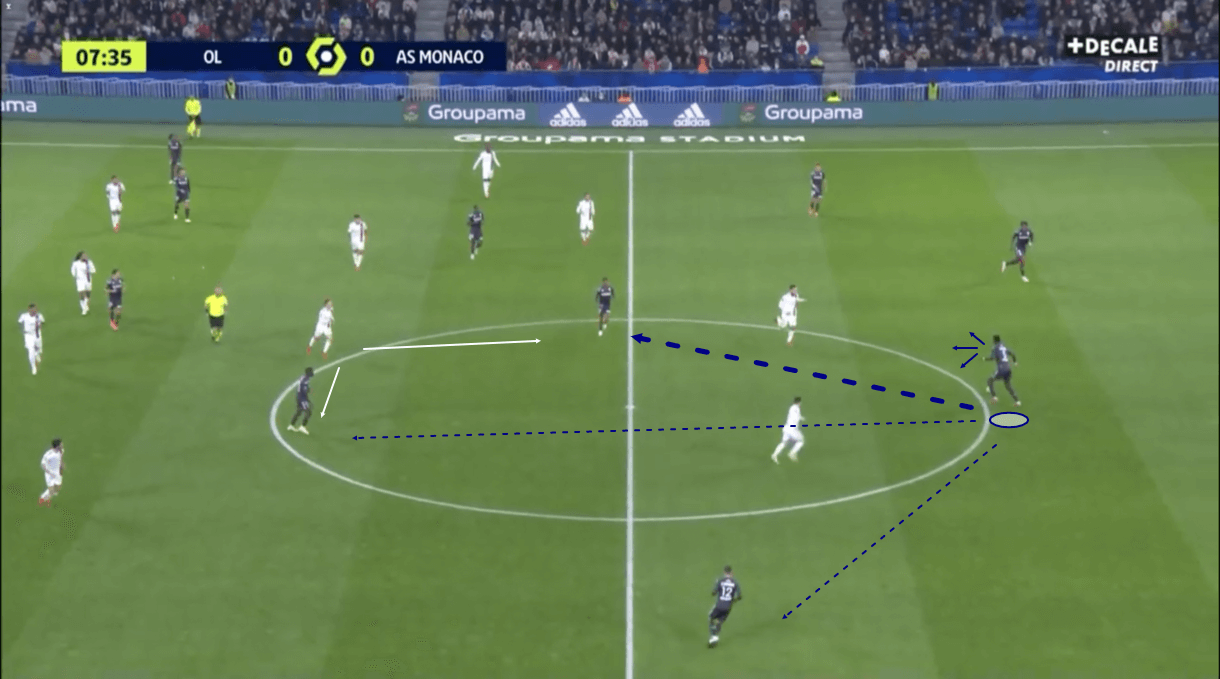

As figure 3 shows, Badiashile often has lots of passing options available to him within Kovač’s system. The centre-backs play a central role in ball progression for Monaco and this plays nicely into one of the big strengths of Badiashile’s game. With these options available in figure 3, it’s now up to Badiashile to make the right decisions and execute them well to perform his role in successfully driving the team upfield. To achieve this, similar to the previous passage of play, Badiashile quickly scans to assess his options, as well as the opposition’s press. With the left-back and two central midfielders seemingly available, the centre-back opts to play the ball into the right central midfielder.

One of Lyon’s midfielders had access to both of the midfield passing options Badiashile had to choose from in figure 3 and as the ball was played to the right central midfielder, this Lyon player sprung into action, targeting the receiver with aggressive pressure. However, as we see in figure 4, the receiver reacted well under pressure, successfully attracting the Lyon man towards him and dragging the midfielder out of position by carrying the ball back into Monaco’s half. This created more space for the left central midfielder, as now this opposition player who had access to both midfielders is just marking one.

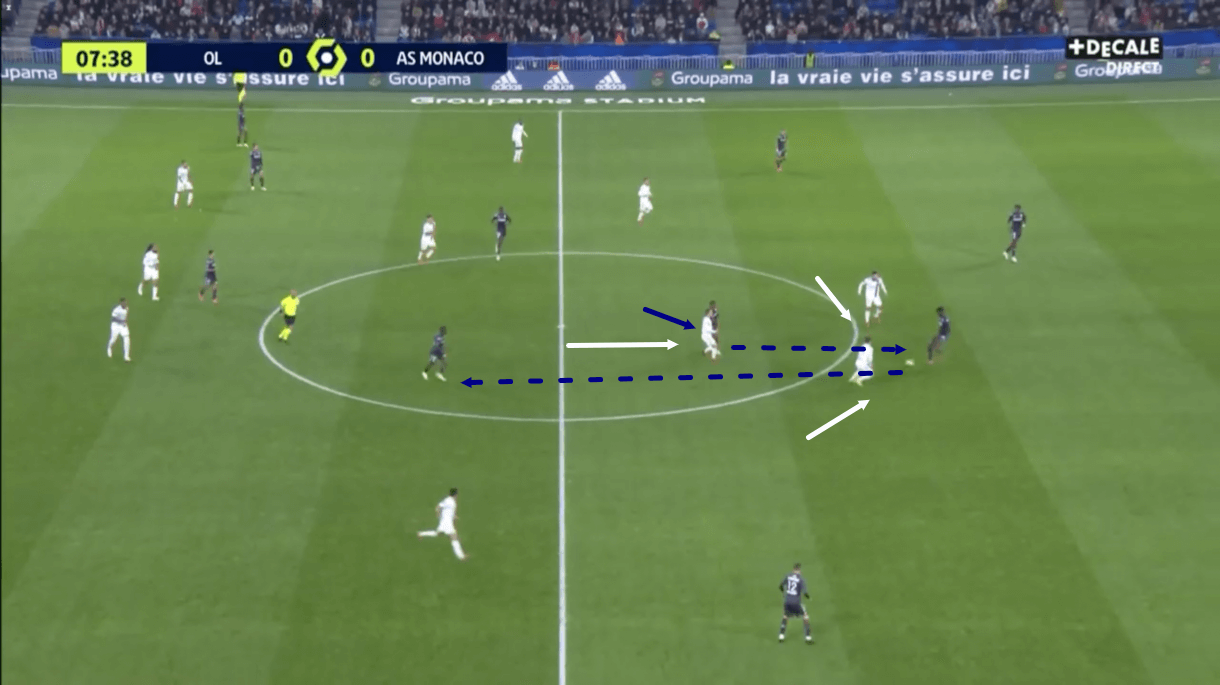

After carrying the ball back into Monaco’s half, the midfielder sent it back to Badiashile. This backwards pass leads to Lyon’s forwards increasing the intensity of their press on the Monaco centre-back too but Badiashile was prepared to react quickly when the ball was played back to him, as he sent the ball forward into the feet of his left central midfield option, who now enjoyed an increased amount of space in midfield thanks to Badiashile’s original decision and the receiver’s good carrying work.

Figure 4 provides another example of the centre-back’s composure under pressure, with Badiashile staying calm to thread the ball through the tight gap that existed between the aggressive opposition pressure right in front of him with just one touch. He’s got excellent decision-making, vision, and technical passing quality to ensure that he deals with this type of situation effectively, however. This results in Monaco being able to trust Badiashile in these difficult high-pressure scenarios and enjoy the benefits that come with having a player of such quality in their squad, as they can exploit a weakened opposition defensive structure in just a few passes, largely thanks to Badiashile’s quality on the ball.

Figure 5 shows another example of Badiashile helping his team to progress through a mid-block from this same game versus Lyon. Here, we see the opposition set up in a very similar defensive shape as before. The pass to the left central midfielder is blocked by the pressing forward’s cover shadow, while Lyon’s holding midfielder is protecting the space behind Monaco’s right central midfielder. After quickly scanning again, Badiashile had the options of either sending the ball out to the left-back, which could lead to Monaco getting pinned out wide, sending the ball into the right central midfielder again, which could lead to Lyon trapping Monaco centrally, or going long, which is a riskier passing option.

As play moves on, we see Badiashile send the ball into the right central midfielder again, using his stronger left foot to naturally direct the ball inside from the standing position we see him in above. He executes the pass very well, sending the ball to the midfielder’s right foot with good pace. While the receiver can’t turn due to the holding midfielder behind him, he can quickly link up with the left central midfielder who has far more space ahead of him. That’s exactly what happens as this play moves on, which sets up an overload for Monaco on Lyon’s backline. So, while the pass into the left central midfielder was blocked initially, Badiashile helped his team to open the opposition up and get this player on the ball very quickly and easily via a well-executed diagonal pass into midfield.

Badiashile’s positive decision-making is on display again here, through his decision to opt for the pass into central midfield, rather than the pass out wide to the left-back who, although enjoying lots of space here, is in a less threatening area than the central midfielders. Again, this highlights the Monaco man’s positive approach to the game, which is a big part of what makes him so valuable to his side on the ball.

Badiashile often finds himself occupying very wide areas in the build-up, as figure 6 demonstrates. This is a result of the left-back getting pressed aggressively out wide during this phase of play and needing support to get out of the tricky situation. In figure 6, we can see that Badiashile pushed out from his regular left centre-back position to more of a typical left-back position to receive a backwards pass from the left-back and ease pressure on this player. We know that Badiashile is comfortable under pressure, so would be happy to receive the ball in this scenario, and as well as that, the centre-back is comfortable with playing in this deeper, wider position when necessary. However, it’s worth noting that Badiashile prefers to link up with teammates via the shorter passes that we observed in the previous examples.

Here, the 20-year-old’s vision, technical passing quality, and composure under pressure are all on display again as he picks out a teammate in a slightly more central left-sided position with an accurate, well-weighted progressive pass that breaks the opposition’s first two lines of pressure despite Monaco having been in a disadvantageous position in figure 6. This shows the benefits of Badiashile’s quality for Monaco and how his ability on the ball can turn things around for Les Monégasques quickly in the early possession phases. So, Badiashile is a clear asset for his side in these phases.

Long balls

On paper, Badiashile’s long ball performance doesn’t hold up with his performance in terms of general passing or progressive passing. The Frenchman has performed 6.02 long passes this season — a fairly high number among Ligue 1 centre-backs with 200 minutes or more to their name so far — but he’s got a long pass accuracy of just 53.85%, which isn’t great.

However, one key reason for this is the role that Badiashile plays for Monaco directly from kick-off.

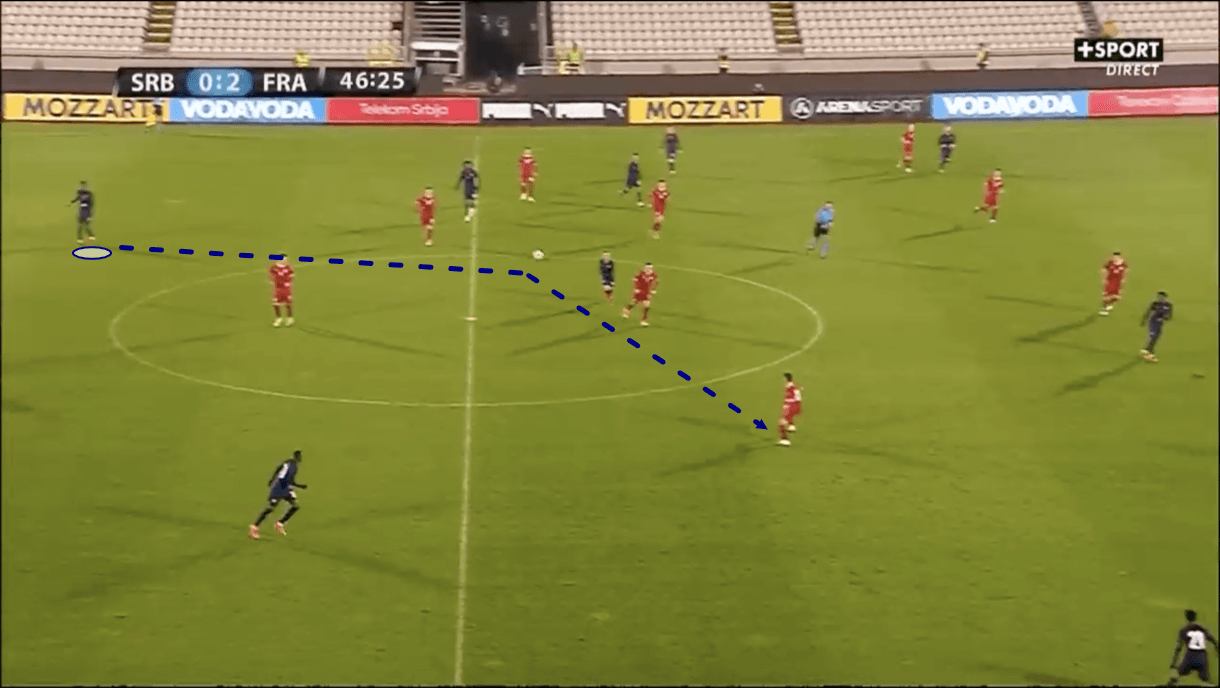

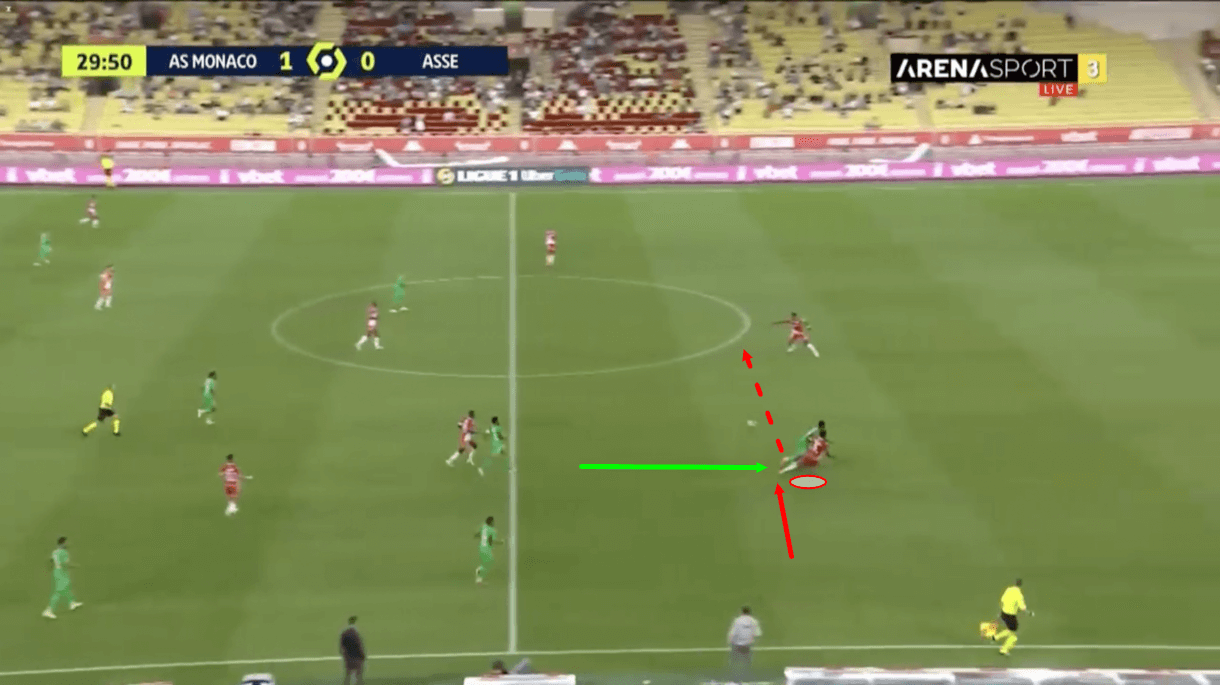

Some coaches like their teams to hit a long ball from the back to one of the wings directly from kick-off and Niko Kovač is one of those coaches. However, he doesn’t intend for his side to retain possession from this long pass, rather, he intends to set up an opportunity for his side to win the second ball. Figure 7 shows an example of this long ball from kick-off that Monaco play in many games, typically via Badiashile. The left centre-back sends the ball towards the right-wing/opposition left-back not because Monaco have a wide target man to win the aerial duel, but because they set up to have men in front of the ball to pounce on the second ball resulting from the ball being knocked down into midfield.

The long ball needs to be well-weighted and accurate so the right-winger could get onto the end of it if the ball were just left alone. It needs to target the space just behind the opposition’s full-back from kick-off, which was the case in figure 7. The right-winger will look to contest the aerial duel but he’s aware he’s unlikely to win it. However, the rest of midfield are positioned well to pounce on the second ball via their press, which is the purpose of this setup. So, while this can make Badiashile’s long pass accuracy look less impressive, it highlights the 20-year-old’s quality on the ball even more in that he’s trusted with performing this role and does so well.

Badiashile is capable of playing accurate long passes to drop right in front of/onto teammates as well and figure 8 shows an example of one such occasion. Here, we see the 20-year-old in the deep, wide left-back-like position he often occupies in build-up again. Again, on this occasion, he came under plenty of pressure in this position but dealt with it well by showcasing his composure, vision and technical quality to pick out a teammate in the middle third of the pitch on the left-wing who dropped off to make himself a long passing option for the France U21 international.

The centre-back is good at playing long balls with accuracy and floating them towards intended targets with the right amount of power. As was the case in figure 8, this helps Monaco to get out from the back and into a more favourable attacking position.

As figure 9 shows, Badiashile’s long passing isn’t always perfect. Here, while attempting a big switch of play from the left centre-back position aiming for the right-wing while playing for France’s U21s, he under-hit the pass significantly and allowed the opposition to counter-attack from a dangerous position. On other occasions, Badiashile will overhit long passes and either put them out of a teammate’s reach or out of play altogether. So, there’s some fine-tuning to be done, at times, in terms of the 20-year-old’s long passing power. In general, though, he’s quite reliable with long balls.

Overall, Badiashile much prefers to link up with teammates via short passes. He works best in a system that focuses on progressing via short passes and, ideally, creates lots of natural passing options for the centre-back, which Badiashile gets at Monaco. His average pass length in Ligue 1 this season is 19.37m at present, which is quite short. While he’s capable of playing accurate long balls to feet and for his specific role at kick-off, he’s not immune to mispowering long passes and can improve that area of his game to an extent. All in all though, Badiashile is a very strong ball progressor from the back.

Defensive positive qualities

Badiashile’s defensive abilities are a bit of a mixed bag, which is why I’ve split them into two sections. Firstly, I’m going to focus on the Frenchman’s positive defensive qualities. He’s an aggressive defender who likes to step out and actively engage attackers in defensive duels. Where Badiashile truly shines without the ball is when defending against counter-attacks. His pace, strength, anticipation and fast reactions stand out in these situations to make him stand out as a defender in transition. He typically performs well when defending while moving into space and thrives in fast-paced situations.

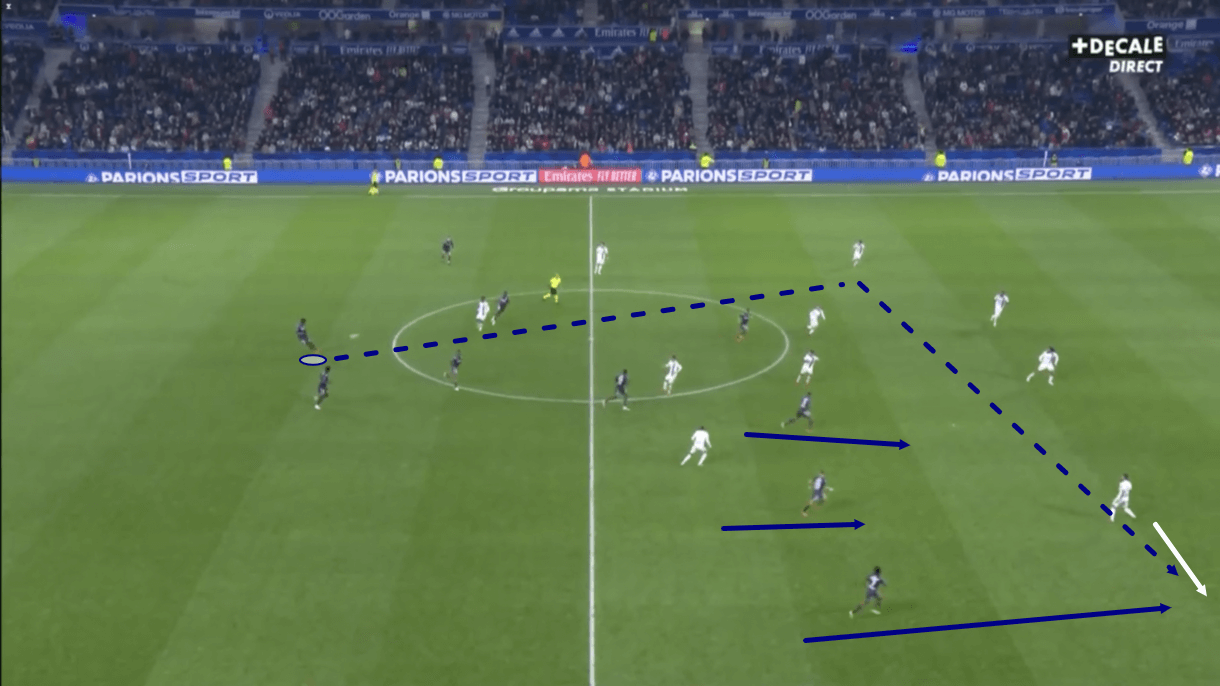

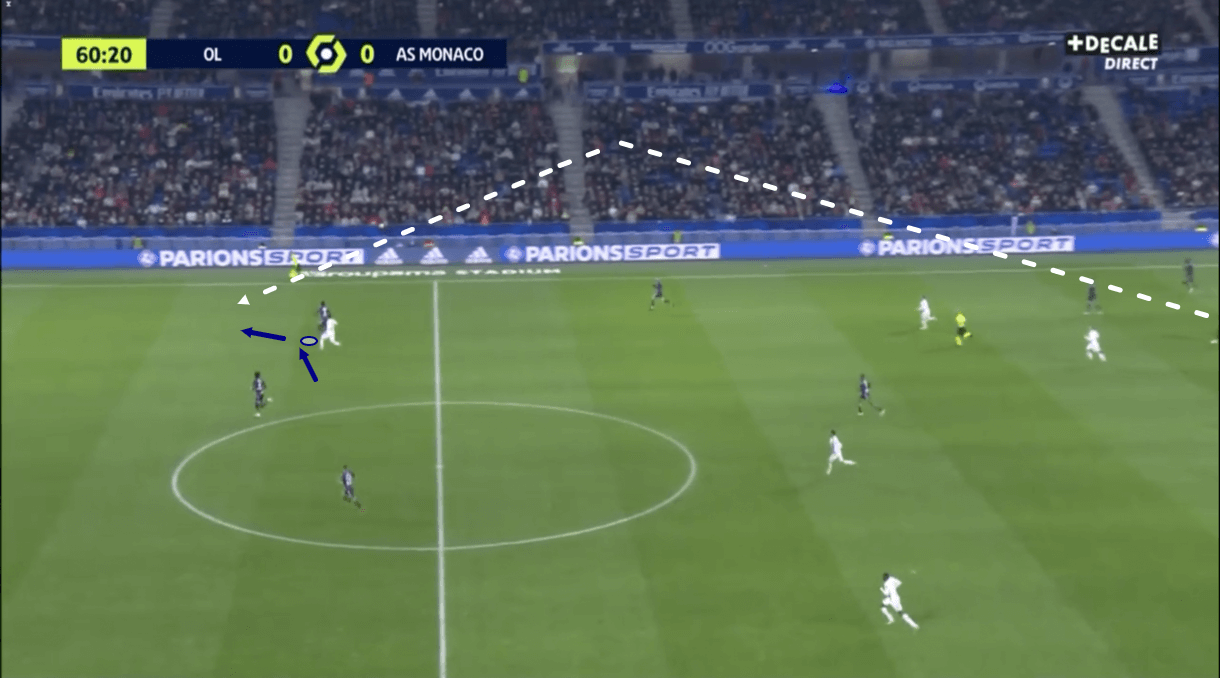

Figure 10 shows an example of Badiashile defending against a long ball from the opposition, with Lyon attempting to initiate a counter-attack here. However, while the long ball over the top was accurate for the runner, it was ineffective due to Badiashile. The Monaco man stepped in front of the runner as soon as the trajectory of this long ball became clear to stifle their attempt to get onto the end of the pass through his positioning and large, wide frame.

It’s common to see Badiashile step out into wider areas quickly like this when defending against a counter-attack. He’s very comfortable with defending in wider areas 1v1 on the counter and is good at positioning himself well to get onto the end of the ball, while also getting between the attacker and the ball to protect it from the attacker.

Badiashile’s pace also helps him to clean up in these situations. The opposition are playing the ball into space to try and target the space behind Monaco’s backline. Badiashile does well when defending with lots of space to run into thanks to his speed. When combined with his positioning and anticipation, this helps the 20-yea-old to successfully end this Lyon counter-attack and regain possession for Monaco.

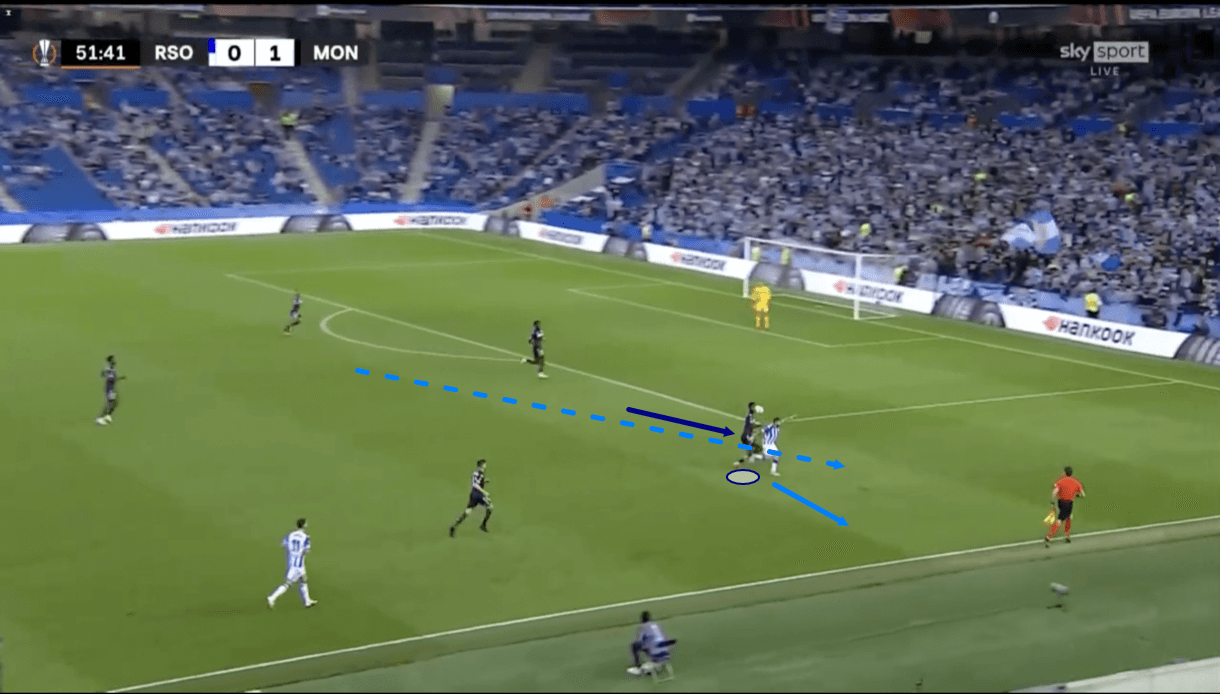

We see another example of Badiashile defending against a counter-attack out wide in figure 11. In this example, we see the ball being sent forward for this runner on the right-wing via a long ball that’s curling inward towards Monaco’s goal. Just like in the previous example, Badiashile thwarts this attack very intelligently. Firstly, we see similar intelligent anticipation and positioning as we did in the previous image. Here, Badiashile’s between the man and the goal, at about arm’s length and at a sideways angle to the attacker, so he is positioned well to react to any movement the attacker makes, should he receive this pass.

However, the 20-year-old went one further and prevented the attacker from even receiving this pass by using his strength. With both men running at pace, Badiashile intelligently unbalanced the attacker by giving him a quick fair nudge with his shoulder. This led to the attacker stumbling away from Monaco’s goal and the path that the long ball was taking. As this passage of play then moves on, we see the Monaco man find it relatively simple to clean up in behind the backline with far less pressure, being able to collect the ball and end this counter-attack.

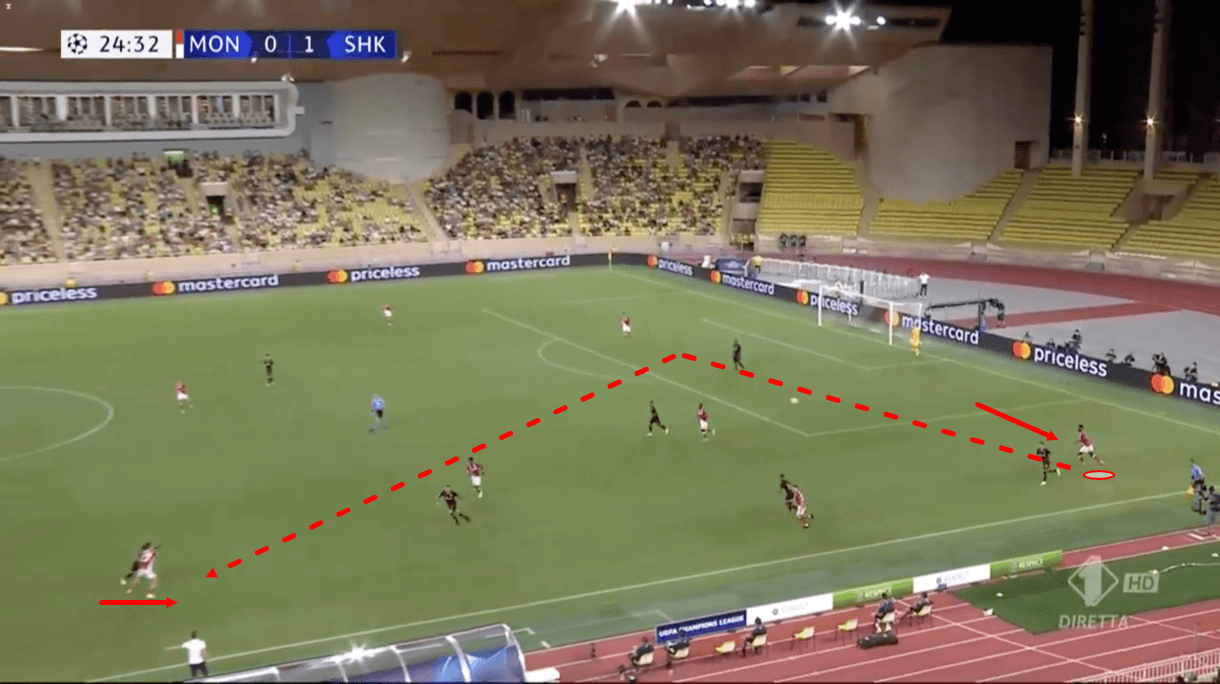

Badiashile’s pace and aggressiveness are also on display in the passage of play beginning with figure 12. Here, the France U21 international is positioned wide on the left-wing while the opposition attempt to target the space between him and Monaco’s other centre-back with a through ball. Here, the centre-back has a choice between either dropping off, positioning himself between the man and the goal, and trying to guide him away from goal or aggressively engaging the attacker to put a quick end to this counter-attack attempt. As we can see by his body positioning in figure 12, Badiashile opted for the latter.

This highlights the defender’s positive, aggressive mindset again. He wants to win possession for his side as quickly as possible, leading to his decision to engage this attacker in a defensive duel despite being in a bad starting position to win this duel and further from the ball than the attacker is at this moment.

However, as play moves on into figure 13, we see that Badiashile succeeded with his attempt to regain possession, successfully making it to the ball first by stretching out his body and sliding in to knock the ball away from the attacker and onto his central defensive partner who could then start to build an attack for Monaco.

As well as his aggressiveness and positive mindset, this shows another example of how beneficial Badiashile’s pace can be for his side. While he was in a bad starting position here, as a result of the previous passage of play, he recovered well to end the attack and regain possession for his side. Badiashile’s pace can help him to make up for his mistakes in positioning when they occur or getting beat in a 1v1 duel, so it’s a valuable asset.

Defensive issues

While Badiashile has lots of positive defensive qualities, as the last section showed, he’s not perfect without the ball either. He needs to improve in certain areas without the ball to truly live up to his exciting potential and, perhaps, command the ‘Martial-like’ fee that Monaco allegedly want to consider selling the centre-back.

Badiashile has currently got a 66.67% defensive duel success rate which is decent but still falls short when compared to some of Ligue 1’s other top centre-backs. Additionally, Badiashile has made 1.39 fouls per 90 this season, which is quite a lot. The centre-back needs to make fewer fouls and would do well to make a small improvement on his defensive duel success. One of the key reasons I’ve identified for Badiashile’s struggles in these areas is that he’s sometimes too keen to step out of the backline into midfield to engage an attacker.

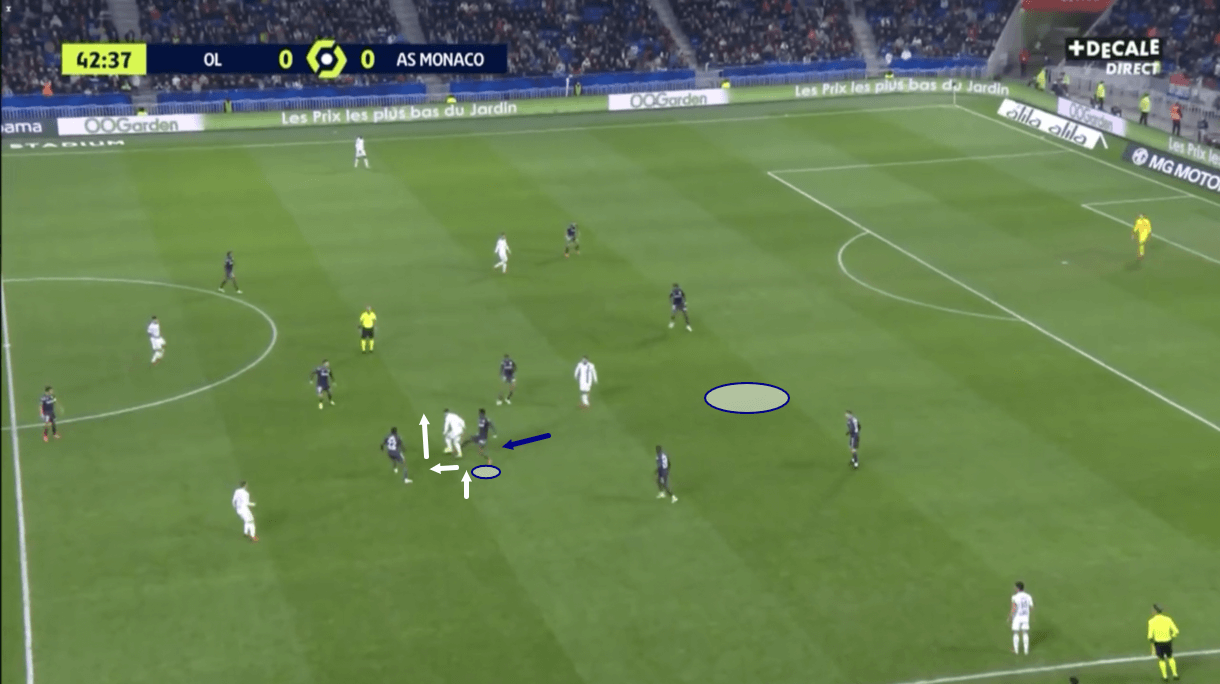

We established the benefits of Badiashile’s aggressiveness in the previous section, but those benefits can still exist while the centre-back reins in some of his more questionable moments of aggression. For example, in figure 14, Lyon can be seen attempting to play through Monaco’s defensive structure. As the ball is played into midfield, Badiashile can be seen stepping out of the backline to engage the attacker receiving the ball fairly deep in the right half-space channel.

The attacker is receiving the ball to feet but does well to take it on the half-turn. While the attacker turns, Badiashile is still a couple of strides away, which highlights what I mean by ‘too keen to step out of the backline’.

If the centre-back were able to cover the necessary ground quickly and either prevent the attacker from turning or catch them while turning to regain possession, then far less of a problem with him stepping out. However, here that’s not the case and despite Badiashile’s high level of pace, he’s unable to make up the ground in time, creating a dangerous situation for Monaco.

As play moves on into figure 15, we see that Badiashile continued to engage the attacker despite him turning. The attacker had enough time to watch Badiashile approach and plan his next move well in advance of the defender engaging with him. This led to the scene we see in figure 15, with the attacker beating the Monaco centre-back 1v1, effectively leaving him in no man’s land and with another attacker ahead of him primed to run into the space Badiashile has left empty in Monaco’s backline that’s yet to be covered by a teammate.

The 20-year-old’s willingness to step out of the backline and engage attackers is positive, he just needs to fine-tune his decision-making a bit and prepare himself better to decide when he should step out and when he should hang back for a bit longer, as being too keen to step out can set you up to fail in the defensive duel and leave a gaping hole for the opposition to target.

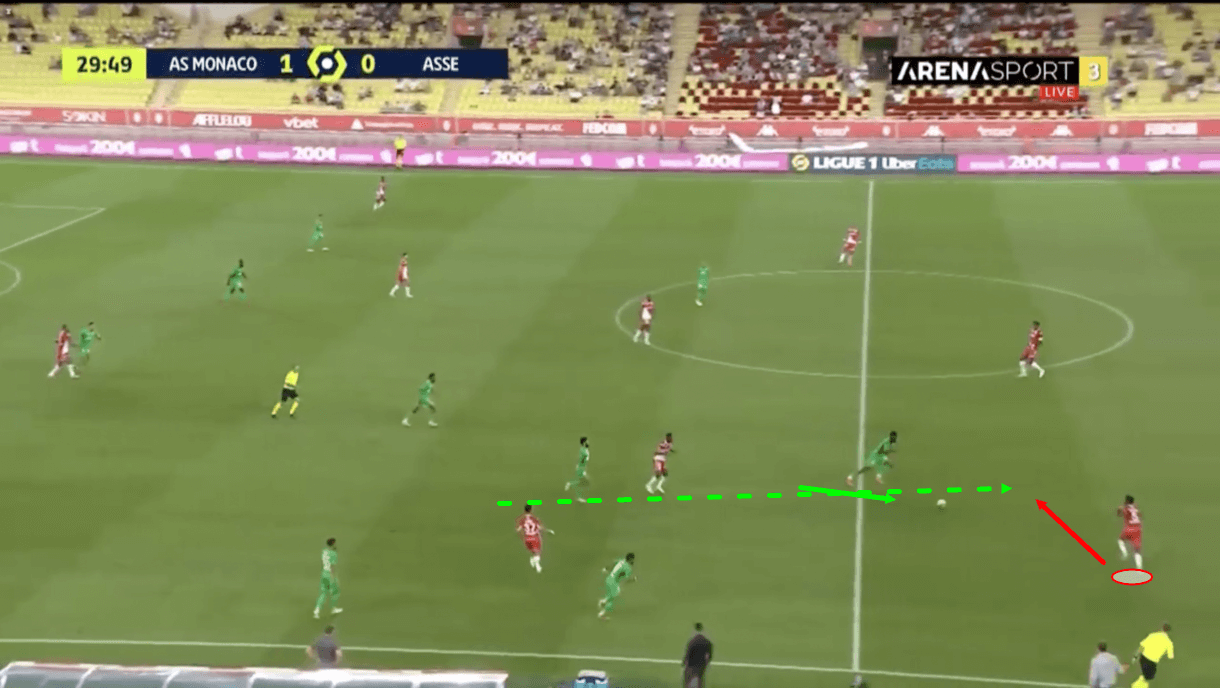

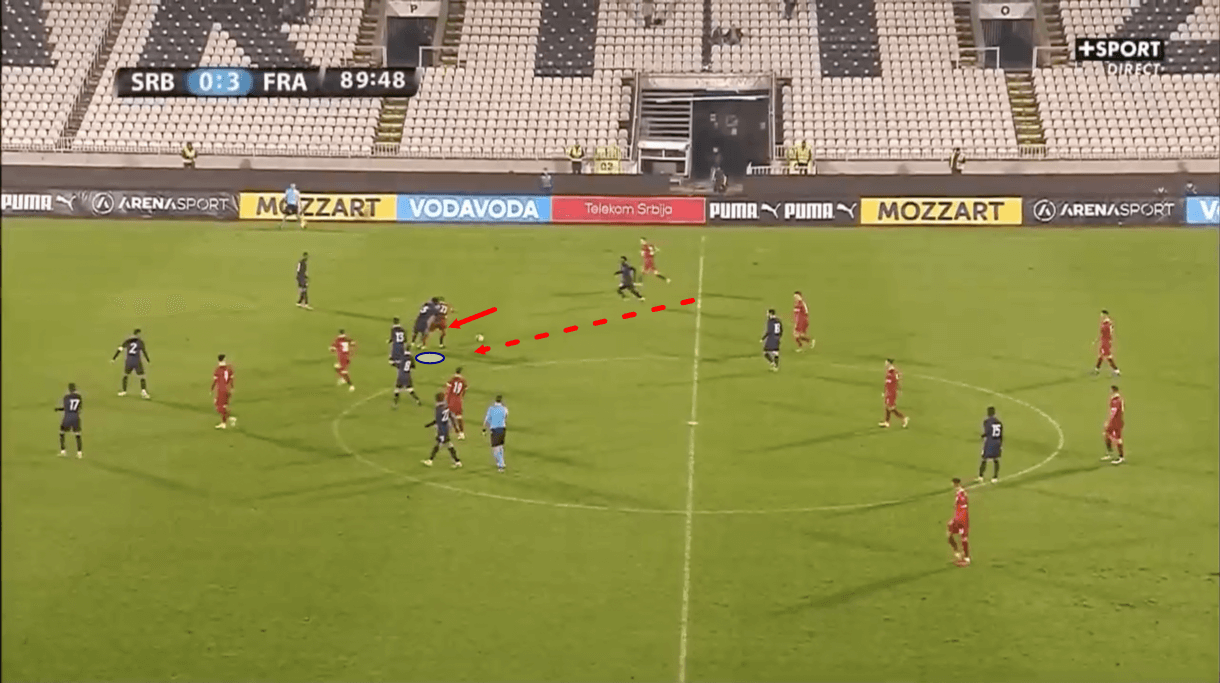

The other key reason I’ve identified for Badiashile’s defensive issues is that he often struggles to defend against an attacker who’s got his back to him. Despite being 194cm and 75kg, he sometimes makes it far too easy for attackers to back into him and gain ground or unbalance him. We see an example of this in figure 16, where the opposition have played the ball into an attacker with his back to goal, who draws Badiashile out of France U21s’ defence towards him. This attacker can comfortably back into the Monaco man while receiving the ball, unbalancing Badiashile and giving himself a better chance to progress past him.

This is an example of poor body positioning when defending against an attacker with his back to you. Badiashile should enter these duels side-on but as figure 16 shows, he often enters them straight-on. Being straight-on makes it much easier for the attacker to back into you because your base is less stable than if you were side-on. The attacker can use Badiashile’s size, which should be an advantage, against him by getting his hips low and backing into him, ultimately unbalancing him and driving him backwards. If he were side-on, the attacker wouldn’t be able to set his hips into the defender so easily, while the centre-back would find it much easier to drive the attacker in the other direction, so this is another area for Badiashile to think about doing some work on the training ground to improve. At present, he’s far more comfortable when defending with space to run into but there’s no reason he can’t develop these negatives to become better at defending against an attacker with his back to goal.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis and scout report, we feel Badiashile is well-suited to an aggressive, possession-based, pass-heavy team, both for his on-the-ball qualities, which include: composure, great technical quality, vision, diligent scanning and intelligent decision-making, as well as his off-the-ball qualities, which include: anticipation, strength, and pace; he’s an excellent asset when building out from the back and when defending against counter-attacks.

To reach his full potential, Badiashile should work on fine-tuning some areas, including the weight of his long passes, his defensive decision-making, levels of defensive aggression, and body positioning when defending against an attacker with their back to goal. If Badiashile can mature in those areas, then there’s no reason why Monaco shouldn’t get their ‘Martial-like’ fee for him, if they want to cash in and if Badiashile fancies a new challenge.

Comments