This year, Leverkusen’s strong performance under former Real Madrid and Liverpool player Xabi Alonso has been gaining a lot of attention across the globe, with Leverkusen being the hottest contender for the Bundesliga title.

However, we could not forget a traditionally strong force from Germany

—Borussia Dortmund, which ranks fifth at the time of writing this article but isonly four points away from third-placed Stuttgart.

Although there were many questions regarding the head coach – Edin Terzić, the club has now reinforced the coaching staff by recruiting ex-players Nuri Şahin and Sven Bender.

They have also qualified from a tough UEFA Champions League group (with PSG, AC Milan, and Newcastle United) in the top spot.

This Borussia Dortmund tactical analysis is a scout report that tries to explain how they attack the opponent without the heavy reliance on structure and passing circuits.

Borussia Dortmund Central Defender Dynamics

Since positional football has been a dominant playing methodology in the last decade, many coaches have been training circuits and fixed passing patterns to obtain automatisms. However, not everyone subscribes to this methodology, and it is not the only way of playing.

Dortmund‘s tactics seem to have allowed some players freedom to express themselves; their attacks have been driven by players’ decisions rather than fixed patterns.

True, we have not been inside the players’ brains, but this analysis tries to explain how the German club has generated dynamics from this style of play.

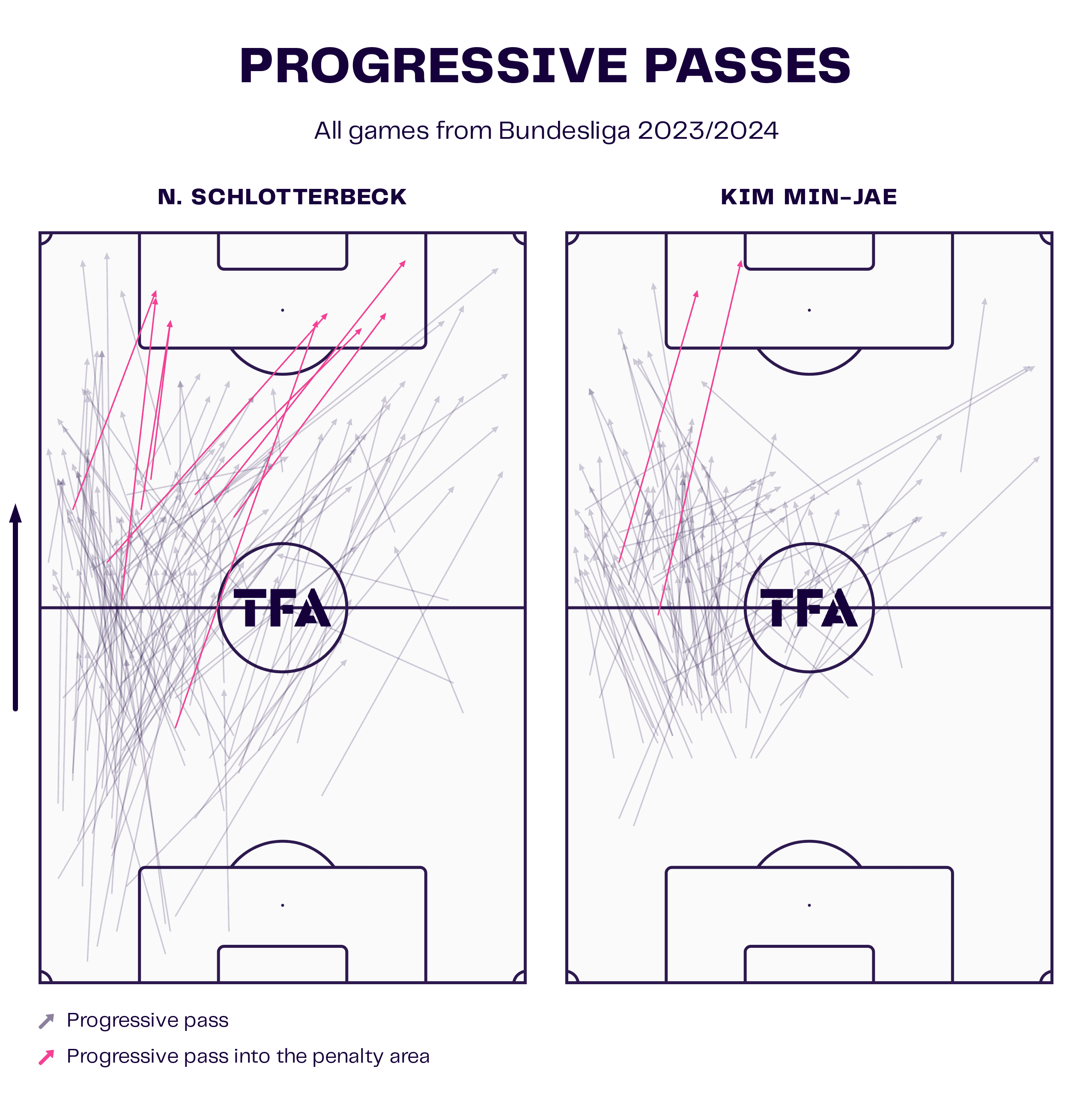

Firstly, we could compare the viz of Dortmund centre-backs and their rivals. The first graph shows the progressive pass map of Nico Schlotterbeck and Kim Jae.

Clear trends are shown in the graph.

Like Schlotterbeck, Kim played a large number of progressive passes, but the deliveries into the penalty box were not as plentiful as those to the Dortmund player.

Furthermore, it seems Schlotterbeck has been more diverse in playing in different directions and has made longer passes, while Kim has been more focused on playing down to the left side despite some switches.

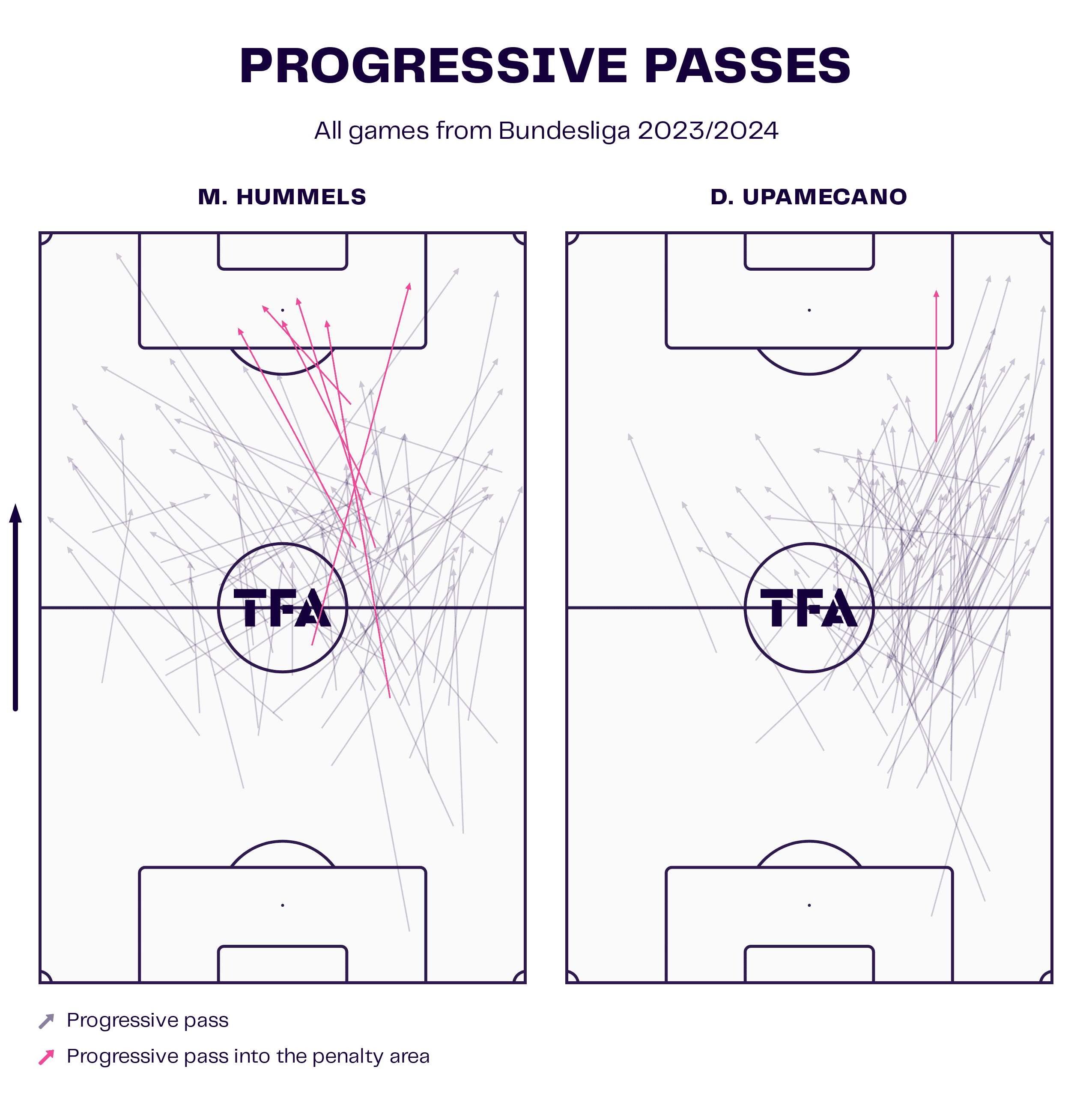

Then, we could compare the progressive pass map of Mats Hummels and Dayot Upamecano.

Again, the Dortmund centre-back displays a lot more passes into the penalty box, while Upamecano has only had one.

The trend was quite similar to the above one, as Hummels has shown he has a great passing range and diversity of passes, while Upamecano is slightly more predictable and plays down the flank quite often.

It could hint that the two Bundesliga teams are playing different kinds of football.

Additionally, the Dortmund centre-backs had 10.52 and 10.43 progressive passes/90, ranking sixth and seventh in the Bundesliga.

But notice that no other teams with a pair of players who had this high frequency of progressive passes when playing together except Waldemar Anton and Dan-Axel Zagadou; this shows that the duo is good at playing the ball forward—and they do so a lot.

Although Dortmund’s attacks seemed to be player-driven, they were not complete chaos.

There were principles to abide by and general trends to observe.

But their interpretations were vital to the moment and the ways they progress the game from their half to the other half.

Here, we include some examples to illustrate different scenarios.

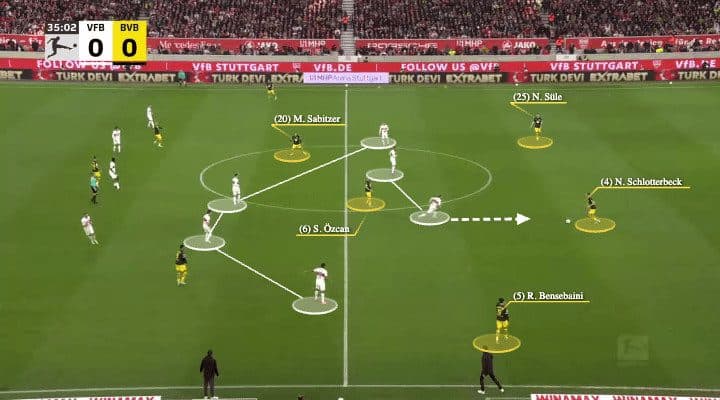

Dortmund usually deploys Marius Wolf at right back and Ramy Bensabaini at left back, but they prefer to have Wolf higher and wider. Sometimes, the left back could stay deeper and closer to Schlotterbeck as a passing outlet.

Then, in the 4-1-2-3, the midfielders could freely pick up the ball instead of waiting for the ball to arrive at their designated space.

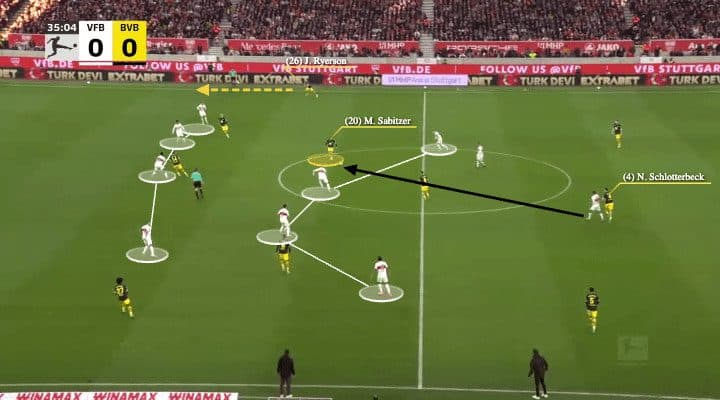

The first image shows Stuttgart defending in a 4-4-2, with the striker putting pressure on Schlotterbeck.

Individually, Schlotterbeck has the ability to hold his pass and dictate the timing of his play to his teammate; as the Stuttgart striker jumped, Dortmund found the gap between the opposition’s second line and reached Marcel Sabitzer in space.

Then, they could spread it out quickly for Julian Ryerson to cross and have an early winger finish inside the penalty area.

Dortmund have scored a large number of goals from this general landscape.

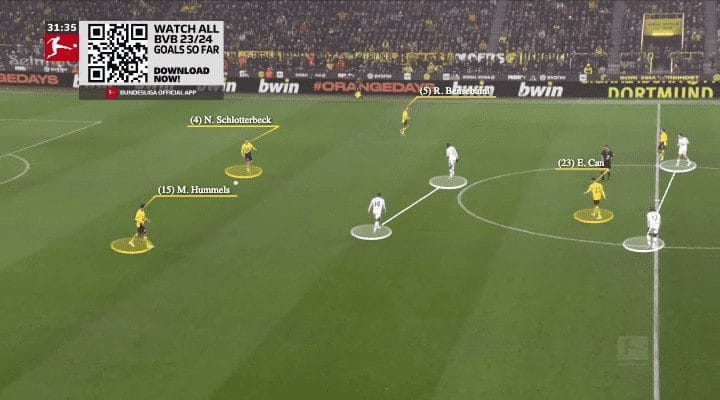

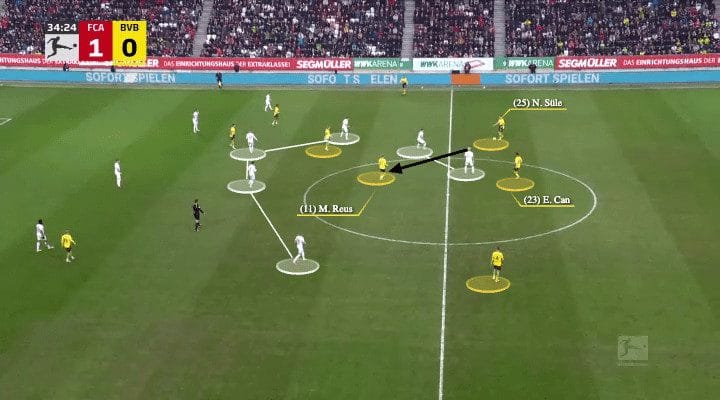

Here, Emre Can, the number 6, has dropped between the centre-back as Niklas Süle and Schlotterbeck stay wider.

Marco Reus went forward initially, but as soon as he saw Can passing the ball to Süle, he decided to stay.

Therefore, the distance between Süle and Reus was not significant, and they could reach each other with a short pass on the ground.

Now Dortmund were inside the Augsburg shape to create further danger.

Although the setup was similar, the condition emerged from the players’ decisions instead of the requirement that one stay there and maintain a rigid structure.

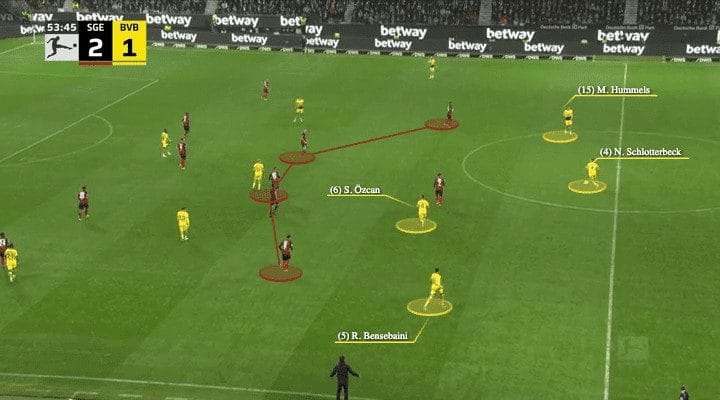

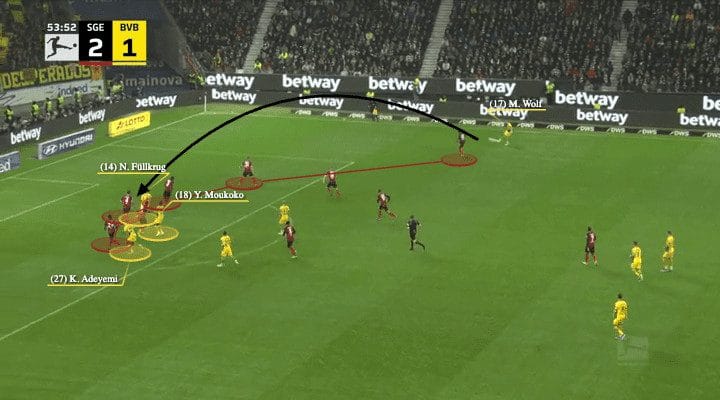

We could observe the example when Dortmund played against Eintracht Frankfurt (who defended in a 5-4-1) away from home.

This time, Salih Özcan was the number 6, and Dortmund more or less had the same setup, but the way to attack was not the centre-back passing diagonally again.

This time, Schlotterbeck took the ball and carried it forward, trying to attack the second line and dribbling past the lone striker.

Obviously, that action alerted the Frankfurt players, so they tightened up in the centre and tried to cover the narrow wingers running behind.

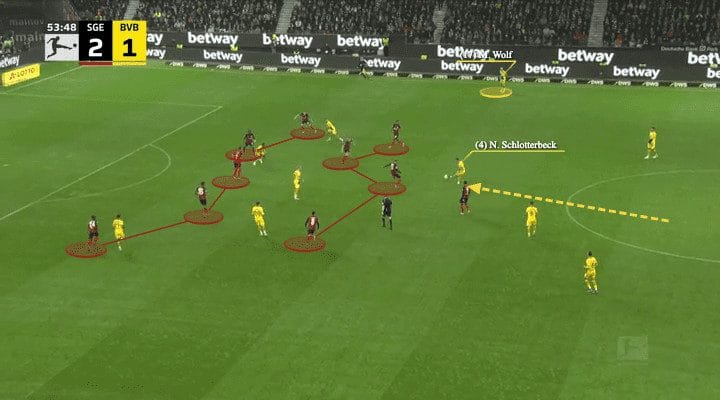

Then, Frankfurt got exploited as now Schlotterbeck could play the ball wide to Wolf, who became free as a result of the central defender’s ball-carrying action.

Compared to the previous image, you could see the opponent had narrowed their shape because of that.

Then, Wolf had all the wide space to cross and attack — now they just crowded the box to finish.

To shed light on a difference, we believe Dortmund instructed the players using some basic principles; from there, different possibilities could emerge based on each individual’s decision, and the outcomes in the attacks from this section were very different.

Füllkrug’s offensive involvement

In plays closer to the opposition’s third, Dortmund heavily relied on Niclas Füllkrug’s characteristics to build plays.

Although he is a pretty tall (1.89m) centre-forward, he’s not a static target man who only waits for the ball in the box and lets the others bring the ball to him.

On the contrary, Füllkrug really enjoys roaming to support his teammate on the ball.

His movements often create openings for his team.

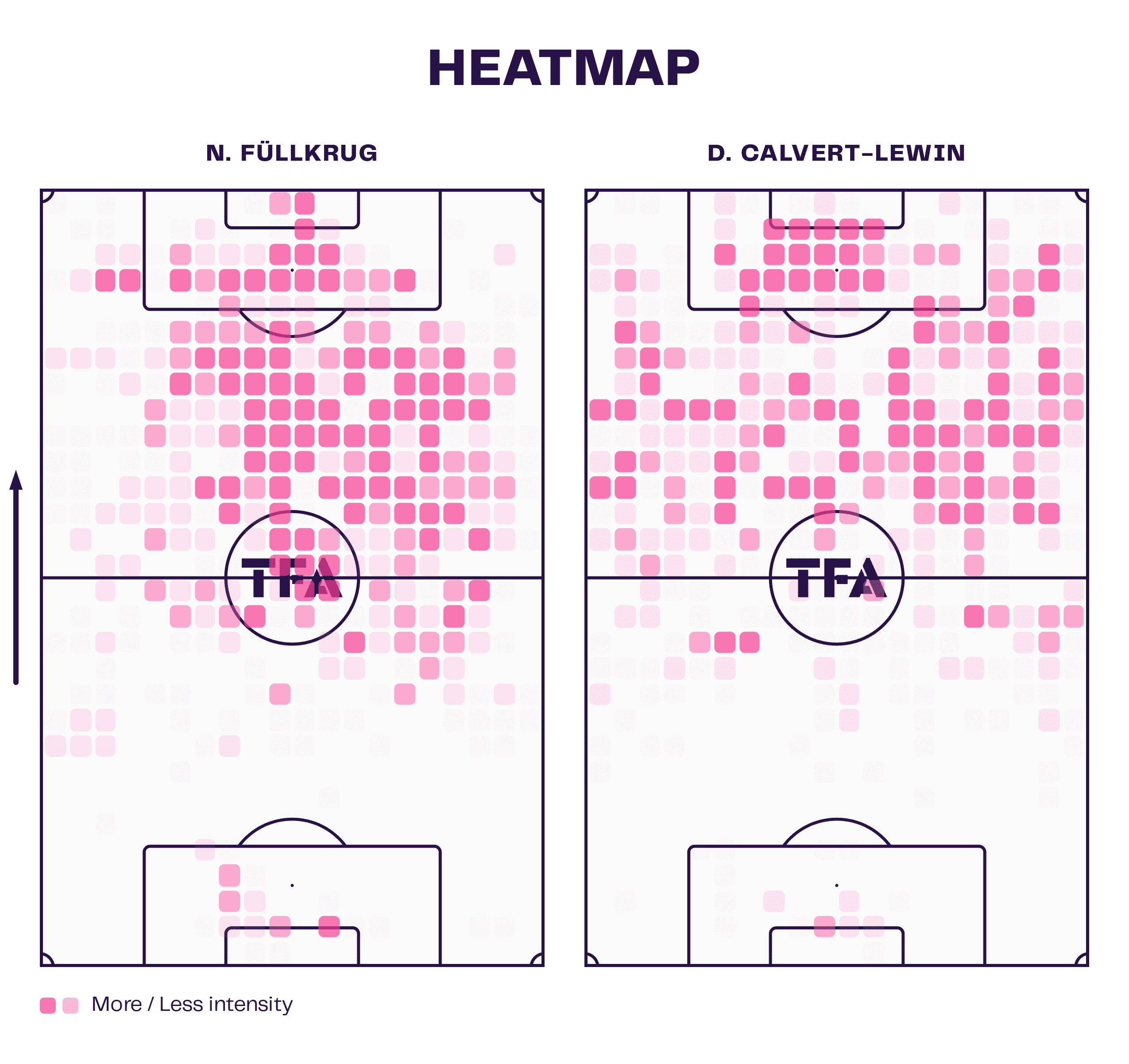

Here, we compared Füllkrug’s heat map with Dominic Calvert-Lewin’s to show the contrast.

Under Sean Dyche, the Englishman has always been a target man in the penalty box for rather long attacks.

He has a very high concentration of touches around the penalty spot, condensing to the six-yard box.

However, Füllkrug is different, as we also see him taking the ball in front of his own penalty box.

This hints that the German international links up with teammates more, rather than just waiting for the ball all the time.

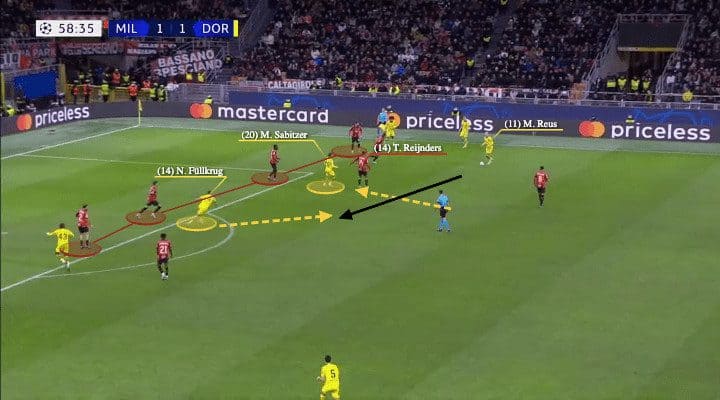

We could see his impact in the decisive goal vs AC Milan.

As Dortmund attacked and inclined on the right flank with Reyerson, Reus, Karim Adeyemi, and Sabitzer on the same side, these players must be able to see each other to make the decision.

For example, if Reus saw Adeyemi and Sabitzer running forward, they would be predictable if Reus was also going in the same direction.

So, he decided to stay in space and give Ryerson a short option to go inside.

As Reus received, Füllkrug moved out when someone else was occupying the penalty box (Sabitzer running forward, plus Jamie Bynoe-Gittens going into the box early as the far-side winger, another general feature of Dortmund).

Then, Dortmund plays quick combinations and gives and goes to try to break the last line and create a goalscoring chance.

They have been more relational than positional in terms of the ways they attack the opponent.

Conclusion

Of course, the results and league table reflect that Dortmund’s tactics have some problems, such as their disorganised last line and unstable performances.

But speaking about how they are playing offensively in this Borussia Dortmund analysis, we feel the players are given a good range of freedom when they have the ball, but perhaps too much when they are without possession.

Now, with new coaches joining the setup, let’s see if they can pick up their form and have a better 2024!

Comments