Before the postponement of the Bundesliga due to the pandemic, Hertha BSC were sitting in 13th place, having played 25 games, drawing seven and losing 11.

They entered the 2019/20 campaign under Ante Čović, however, having only won five out of their first 14 games and conceding a staggering 26 goals, he was quickly shown the exit door.

Hertha BSC then brought in respected and well-known boss Jürgen Klinsmann to try and restore some order to their season.

Klinsmann lasted 10 games, having only won three times.

Alexander Nouri was the successor of Klinsmann shortly after, however only lasted two months at Hertha BSC and it could be argued as one of their worst periods of the 2019/20 campaign.

This scout report will provide an analysis of Hertha BSC under their new boss Bruno Labbadia, who was brought in during the pandemic period.

The tactical analysis will introduce the ‘old’ Hertha BSC before the stoppage and discuss why their tactics used were inefficient in making them serious contenders for the UEFA Champions League places.

The analysis will then progress to analyse the ‘new’ Hertha BSC under Labbadia, and why his tactics have revitalized their campaign, having won both their games after the resumption, scoring seven and conceding zero.

Hertha BSC’s lack of movement in their build-up

Hertha BSC under their previous two managers before Labbadia were very poor in their build up play and lacked any penetration in advanced areas.

During Nouri’s four game spell in charge, Hertha BSC created a total of 1696 passes.

Of these, 601 were forward and 71.7% were accurate per 90.

Although Hertha’s forward passing accuracy was relatively high, the amount of forward passes they made was extremely low across the four games.

This season, they have produced 5426 touches in the defensive third, 7007 in the midfield third and 3193 in the attacking third, highlighting their poor penetration when in the final third.

Under Nouri and Klinsmann, Hertha BSC played very narrow in possession and lacked any cutting edge when playing forwards.

Advanced players were reluctant to receive in between the lines and didn’t exploit the half spaces in attacking areas.

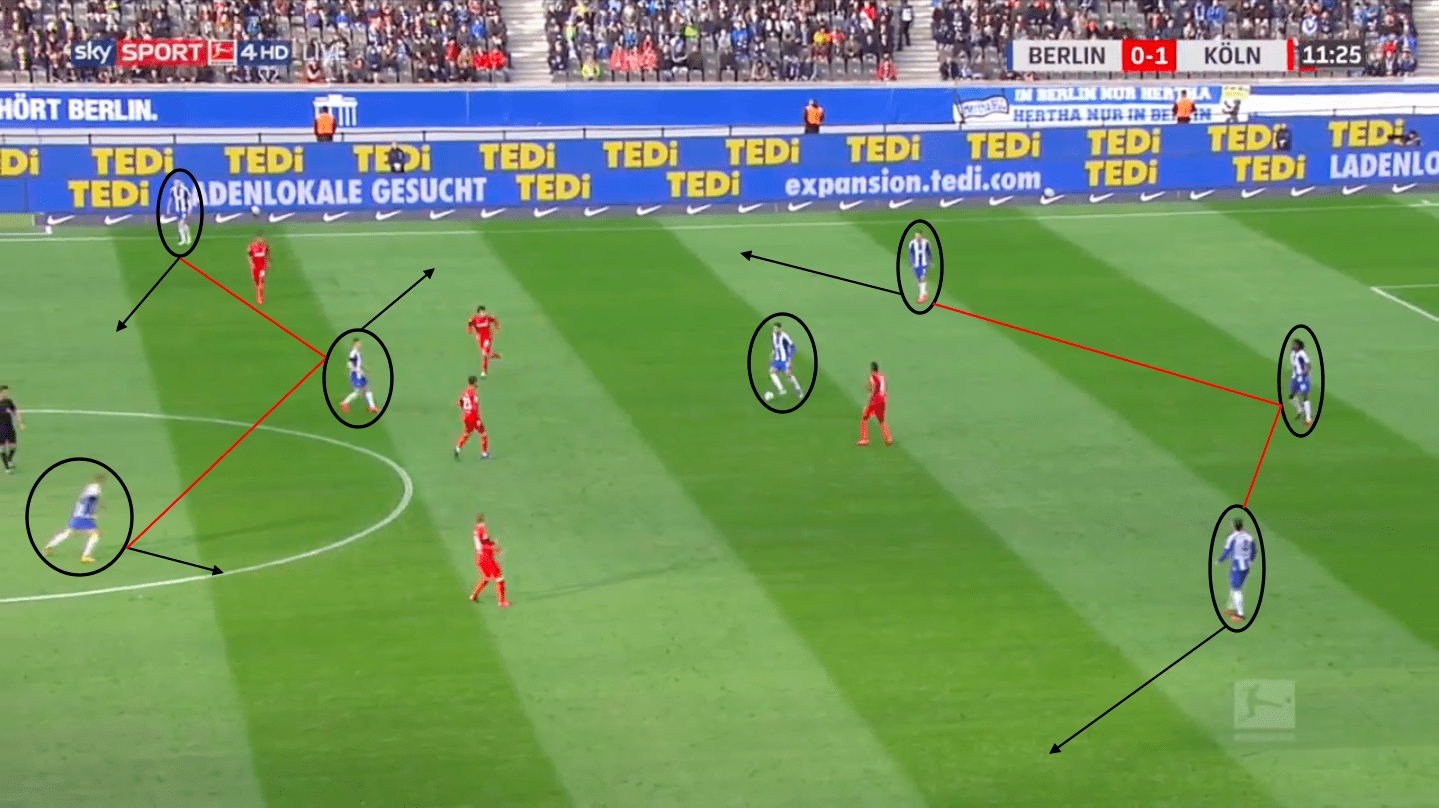

In this example, Nouri set up Hertha BSC in a 3-5-2 against FC Köln and the lack of penetration in their build up was clear to see.

Hertha’s back three stayed very narrow even in possession and failed to capitalise on the spaces in wide areas.

Their single pivot has possession in the central area, however, has no forward passing option due to Hertha’s lack of movement to create space in between the lines.

In order for Hertha to penetrate the opposition in the build-up phase, Rekik (left player of the three) needed to adopt a more wider position to create a passing option to advance forwards.

Berlin’s players in the midfield third needed to rotate to create space to receive to allow them to play forwards and penetrate the spaces in behind.

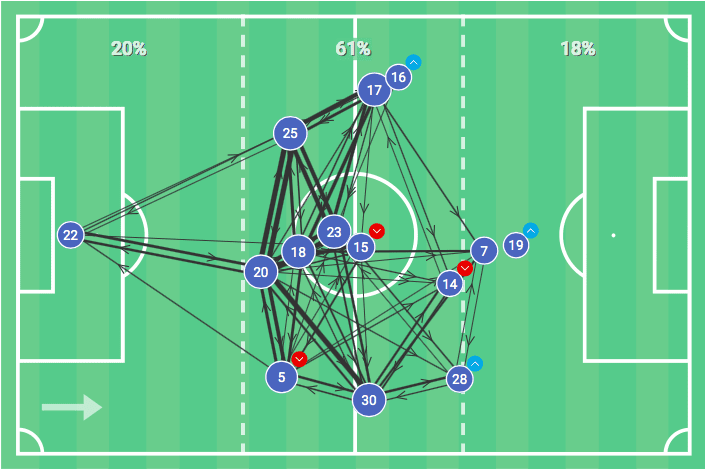

From the graphic below, we can see Hertha’s main pass combinations during the game against Mainz 05.

The darker the black line, the more passes they made.

This highlights Hertha’s lack of progressive passes, with 61% of their main passes being lateral across the back three in the midfield third with a heavily congested middle area.

This could have been a direct result of their lack of movement in advanced areas to create chances to receive.

During the Mainz 05 game, Hertha made 292 lateral passes and only produced 59 passes into the final third and 23 passes into the penalty area.

Although Hertha BSC looked a little more organised under Klinsmann than Nouri, their forward penetration woes were still apparent.

Their lack of movement to create space to receive as well as failing to produce forward passes to penetrate the opposition’s defensive line found themselves only scoring 10 goals in 10 games under Klinsmann.

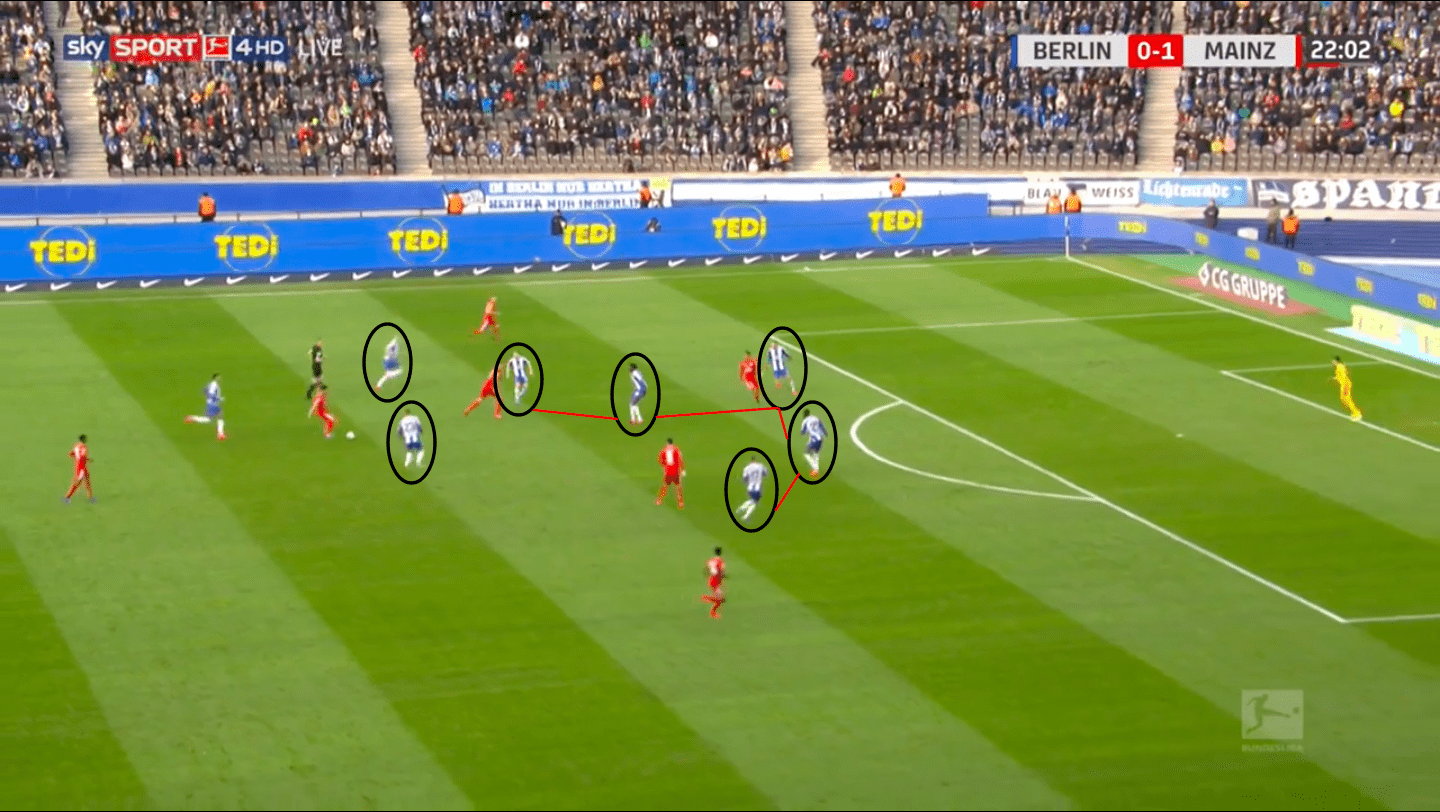

During the game against Mainz 05, Hertha’s failure in their build up play was one of the main reasons why they failed to take three points from the game.

As we see above, their central defenders Boyata and Torunarigha are too close together, failing to create a passing option to retain the ball.

Their two forward players in Köpke and Piątek fail to create distance between them, meaning they are easy to mark and defend against for the opposition.

For their build-up to have been effective, they needed to move the ball quicker in the retention stage.

This would have drawn the opposition out of position and created spaces to play the ball into to exploit in forward areas.

If Piątek had made a backwards movement to receive in between the lines, and Köpke made a double movement to exploit the central space in behind then Mittelstädt would have had two forward passing options to penetrate.

Boyata and Torunarigha needed to split to create distance between them to create passing options to then switch and isolate Stark who is the right full back in space to play forwards.

However, the two defenders are too narrow which fails to create any opportunities to build to penetrate and makes Mainz out of possession defending very easy.

During Nouri’s four-game spell at the club, Hertha BSC averaged 52% possession.

During Klinsmann’s ten-game spell, their average possession percentage was 42%.

For a side that consists of young talented prospects and creative attacking players, they should be dominating possession and penetrating teams with their build up play.

Poor defensive organisation out of possession

Although this analysis has addressed their lack of movement in the build-up as one of the main reasons why Hertha BSC were failing under Nouri and Klinsmann, their poor defensive organisation as a team when out of possession was causing them to concede far too many goals.

This was something Labbadia would need to work on during his reign.

Pre Labbadia, Hertha BSC conceded 48 goals and their expected goals against per 90 minutes stood at 1.78.

Under Nouri, they conceded 11 goals in just four games.

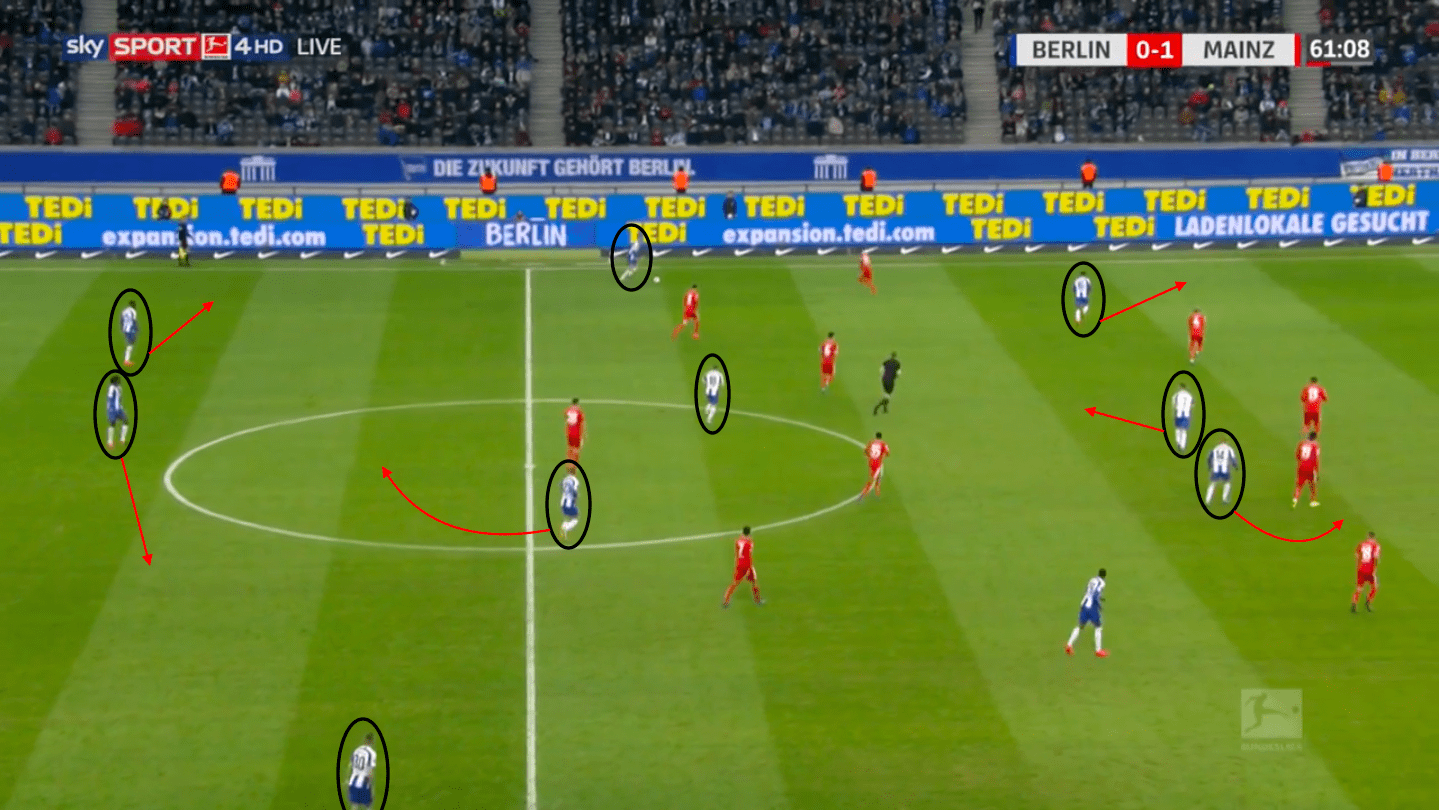

In this example, Klinsmann opted to play with a 3-5-2 and their defensive unit woes out of possession was clear to see.

There was no structure to their shape when Mainz were entering the final third.

Boyata was playing in the centre of the three, with Torunarigha and Stark playing alongside him to complete their defensive line.

However, in the example above, Boyata has pushed forwards to try and prevent Mainz from playing a forward pass to break the line.

Due to Boyata’s movement forward, Torunarigha and Stark then naturally covered this central space left by Boyata.

Due to Hertha’s lack of organisation defensively, they failed to prevent Mainz from occupying the half and wide spaces.

Each Hertha player was attracted to the player with the ball, which created vast amounts of space for Mainz to enter in key attacking areas.

If Klinsmann wanted them to be narrow out of possession, then their wingers making the midfield five in Mittelstädt and Wolf needed to deploy a deeper position, meaning they were goal side of the attacking player and blocking off the half-spaces.

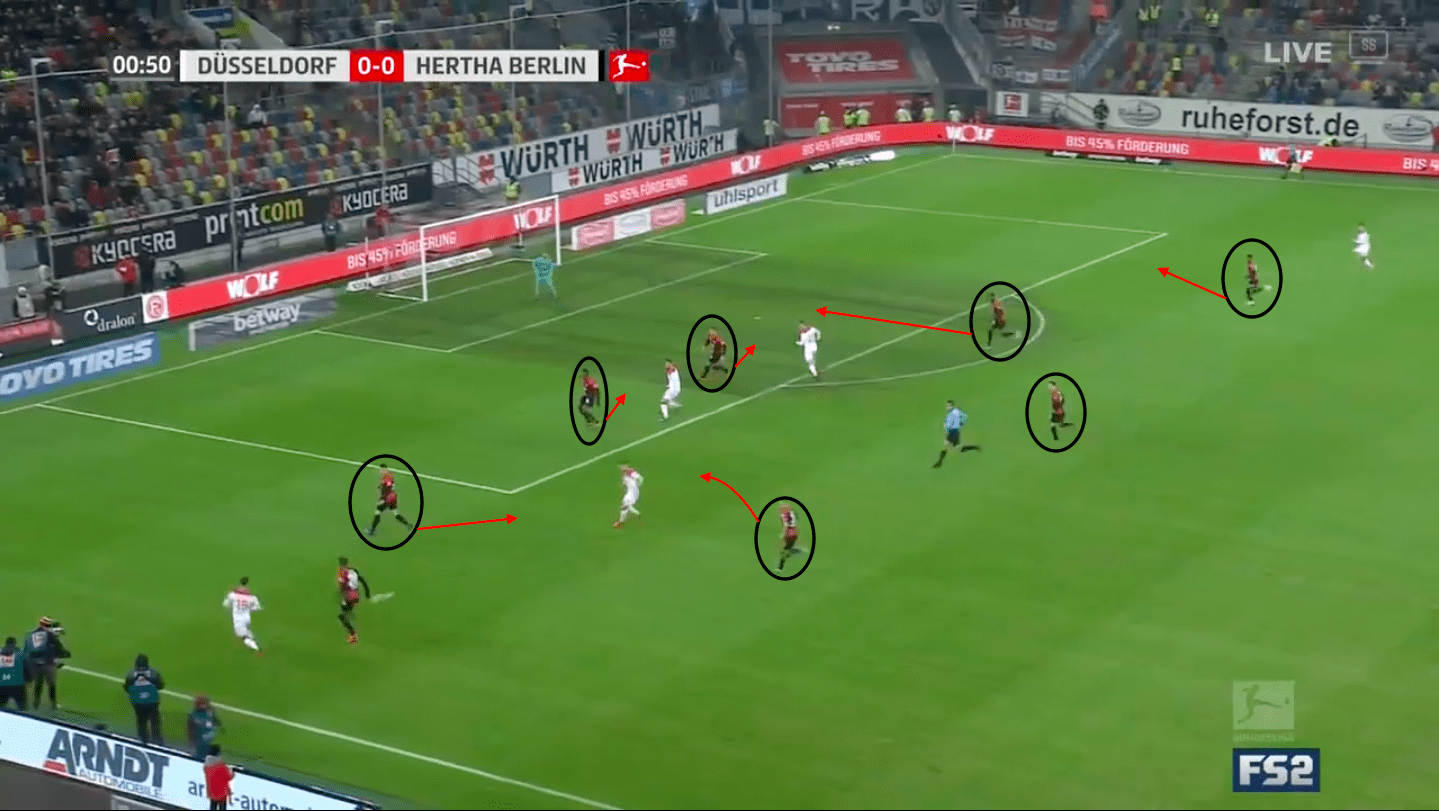

Against Düsseldorf under Nouri, their lack of organisation off the ball as a defensive unit was clearly evident even within the first minute of the game.

They failed to block Düsseldorf playing a pass to exploit the half-space, however, could have if their organisation was more efficient off the ball.

Their back four line in the above image wasn’t narrow.

Players out of position caused Düsseldorf to deploy runners into the central and wide spaces created by Hertha’s lack of organisation as a unit.

If the Hertha’s back line had been goal side and been more side on with their body shape, they would have been in a better position to defend the Düsseldorf attack.

During this current campaign, Hertha have made 246 tackles in the defensive third, as opposed to only 180 in the midfield third and 58 in the attacking third.

It could be argued that opposition players are able to receive the ball in the Hertha defensive third due to their lack of organisation, meaning they have to perform more tackles in these areas to regain possession.

Hertha BSC’s build up tactics under Labbadia

Bruno Labbadia is a 54-year-old German football manager who has recently moved to Hertha BSC from VfL Wolfsburg.

He has also had managerial spells at Hamburger SV and VfB Stuttgart.

As a player, he has played for teams such as Werder Bremen and Bayern Munich.

He has a wealth of experience in the German top flight as a player and manager and is someone who Hertha BSC desperately needed to recover their poor start to this campaign.

Labbadia has revamped Hertha’s season since being in charge and made Hertha a tough team to play against.

Although he has only been in charge for two games including the Berlin derby at the time of writing, his tactics imposed on the team has been clear to see.

Although they have had an average of 52% possession over the two games.

How they have used this possession to their advantage is a tactic Labbadia has introduced.

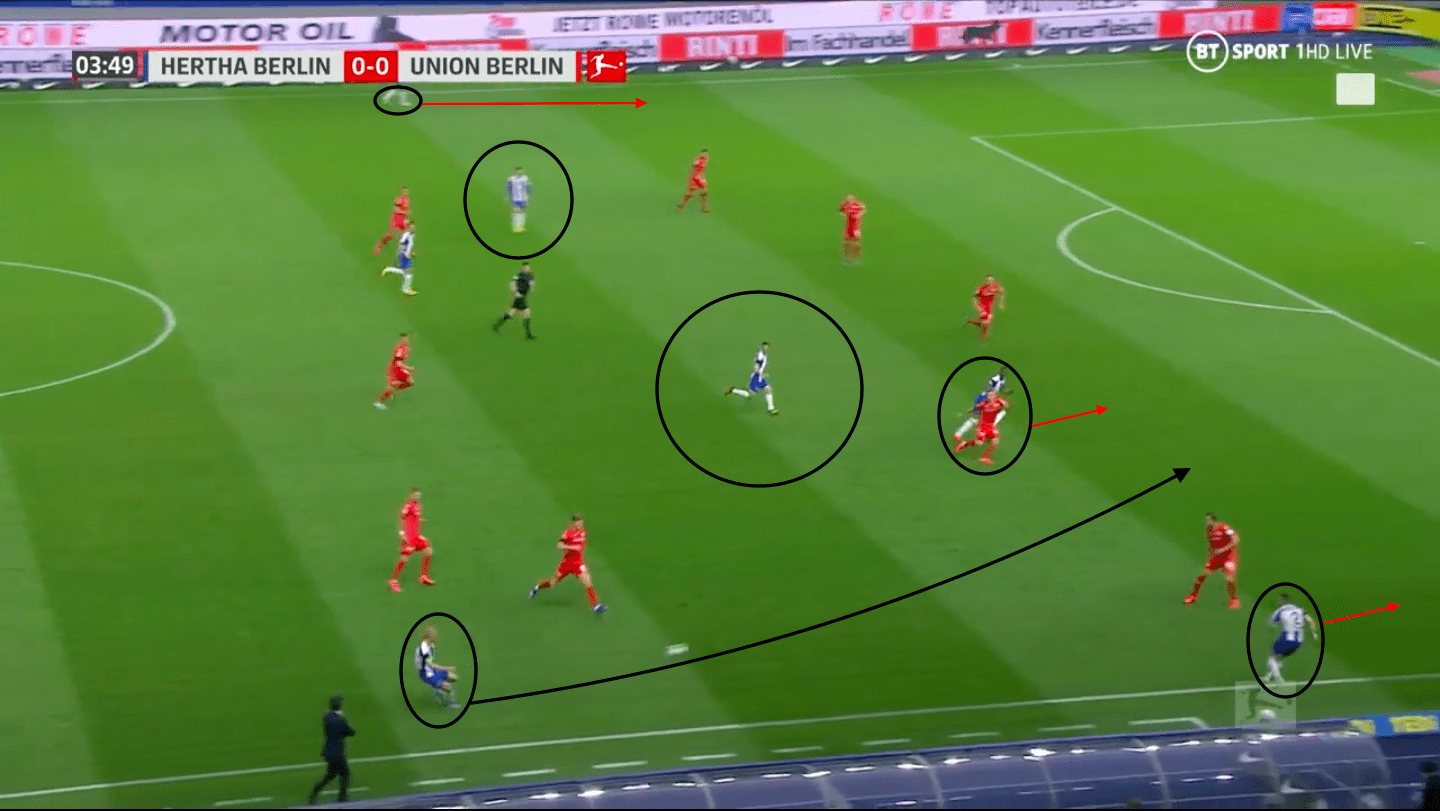

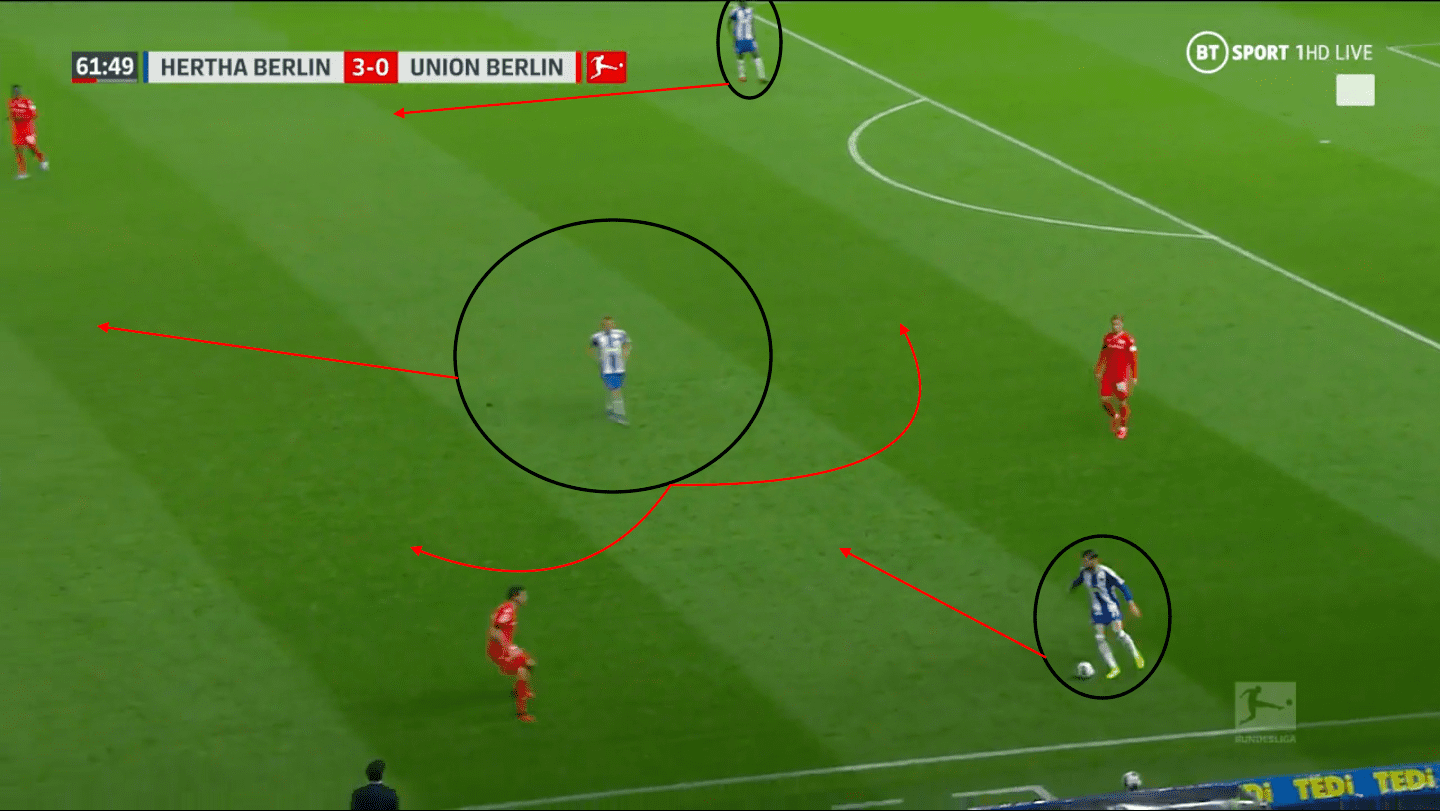

Early in the derby game against Union, we saw Labbadia’s tactics in Hertha’s build-up phase.

He likes his full-backs to be high and wide, which then gives freedom for Cunha and Lukébakio to make use of the half-spaces.

In this build-up example, Hertha’s Skjelbred has the ball in the wide right area and is looking for a chance to progress the ball into the final third.

Labbadia’s use of wide full-backs draws the opposition full-backs out of position, creating a chance for Lukébakio to receive the pass in the half-space.

Plattenhardt, Hertha’s left full-back, is just at the top of the image above, adopting a very wide position, allowing Cunha to drop into the left side half-space.

Grujic can be seen in the central area providing an option to receive in between the lines.

The build-up tactics used by Labbadia provide more freedom for their advanced players to roam to receive.

During Labbadia’s first game against Hoffenheim, Hertha made 50 forward passes with 76% being successful.

They also made 65 progressive passes with 83% accurate.

It could be argued that with Labbadia adopting or his full-backs to be wide and high, creates space for attacking players to receive, therefore producing more progressive passes.

The difference between Hertha’s build-up before Labbadia was their lack of movement in forward areas.

Under Labbadia, we see their rotational movements in the half-spaces to create space in behind or to isolate wide players.

In this example, Lukébakio makes a move into the half space, creating an opportunity for the right full-back Pekarík to receive in the space in behind.

Boyata with the ball can either play into the feet of Lukébakio who can then turn and create an overload in the half-space.

Boyata could also play a ball into the space behind the left opposition full-back for Pekarík to receive.

Hertha have scored a goal in both games from crosses from wide areas under Labbadia.

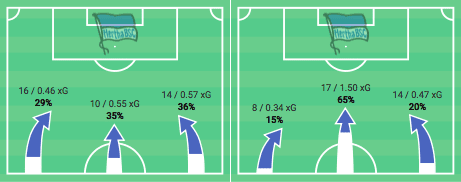

The below on the left portrays Labbadia’s use of the wide areas and Hertha’s build-up in wide positions, compared to Hertha under Nouri in the image on the right against Düsseldorf where their main focus of build-up was through the centre and less of the wide areas.

Labbadia likes to create chances from wide areas and this is a tactic he adopts in the build-up.

As seen above, during the Hoffenheim game, Hertha made 11 crosses, with one cross leading to a Hertha goal.

Their xG per 90 for this game under Labbadia stood at 1.5, compared to their xG of just 1.0 in Nouri’s last game against Werder Bremen.

Hertha’s xG per 90 increased again for the derby against Union under Labbadia, standing at 1.7, compared to Klinsmann’s last game against Mainz 05 where it stood at 0.9.

It could be argued that Labbadia’s tactic of using the wide areas to build has increased their xG ratings per game, compared to that of Nouri and Klinsmann.

To progress from the ball through the thirds, Labbadia likes to use a single pivot to receive the ball to build, as we see in the below example.

Skjelbred is the single pivot creating a clear passing line in the central space.

Hertha are inviting the press, with a single pass into the pivot player allowing Hertha to break through the initial press to progress the ball to the opposite wing to overload.

Defensive organisation under Labbadia

Not only has Labbadia improved Hertha’s build-up play to progress the ball forward, he has also tightened their defensive organisation as a unit.

They have conceded zero goals in their first two games under Labbadia.

Although Hoffenheim made 16 shots, Hertha limited them to only 13% of these being on target.

In the Berlin derby, Hertha limited Union to seven shots, with 0% of these being on target.

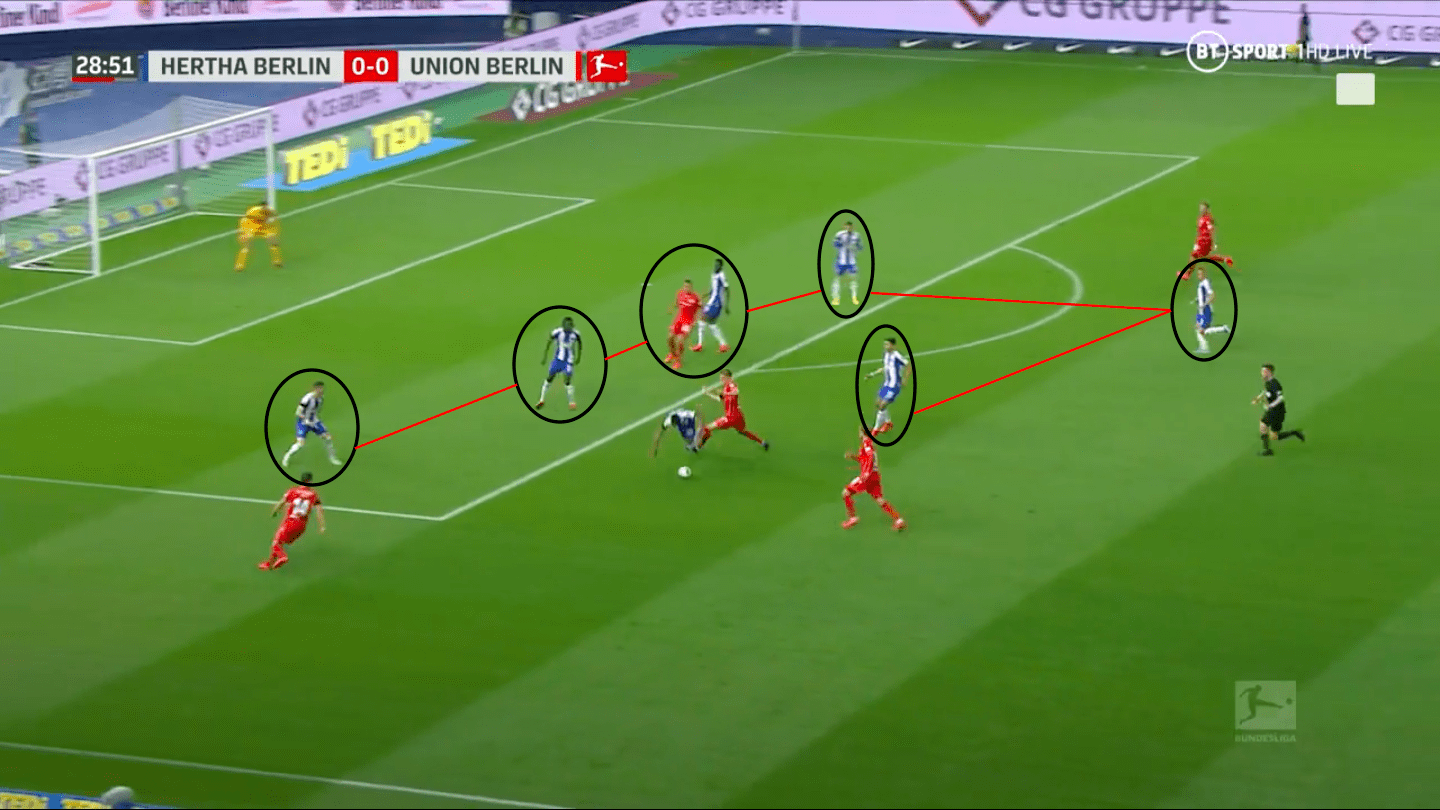

In the image above, the defensive structure of Hertha under Labbadia is clear to see.

As Union try to advance through the left half-space, Hertha’s organisation as a defensive unit makes it difficult for Union to break down.

Labbadia likes to set up his teams in an attacking 4-3-3, and in the game against Union he fielded a 4-2-3-1.

We see above that the back four out of possession are very organised, all a good distance away from one another and adopting a correct body shape to allow them to see the ball and the opposition players.

They are seen to compact the central spaces, forcing Union to play wide.

Union like to get the ball into their lone striker Andersson, so with Hertha’s compactness and organisation as a defensive unit under Labbadia will see them concede less goals than previous managers.

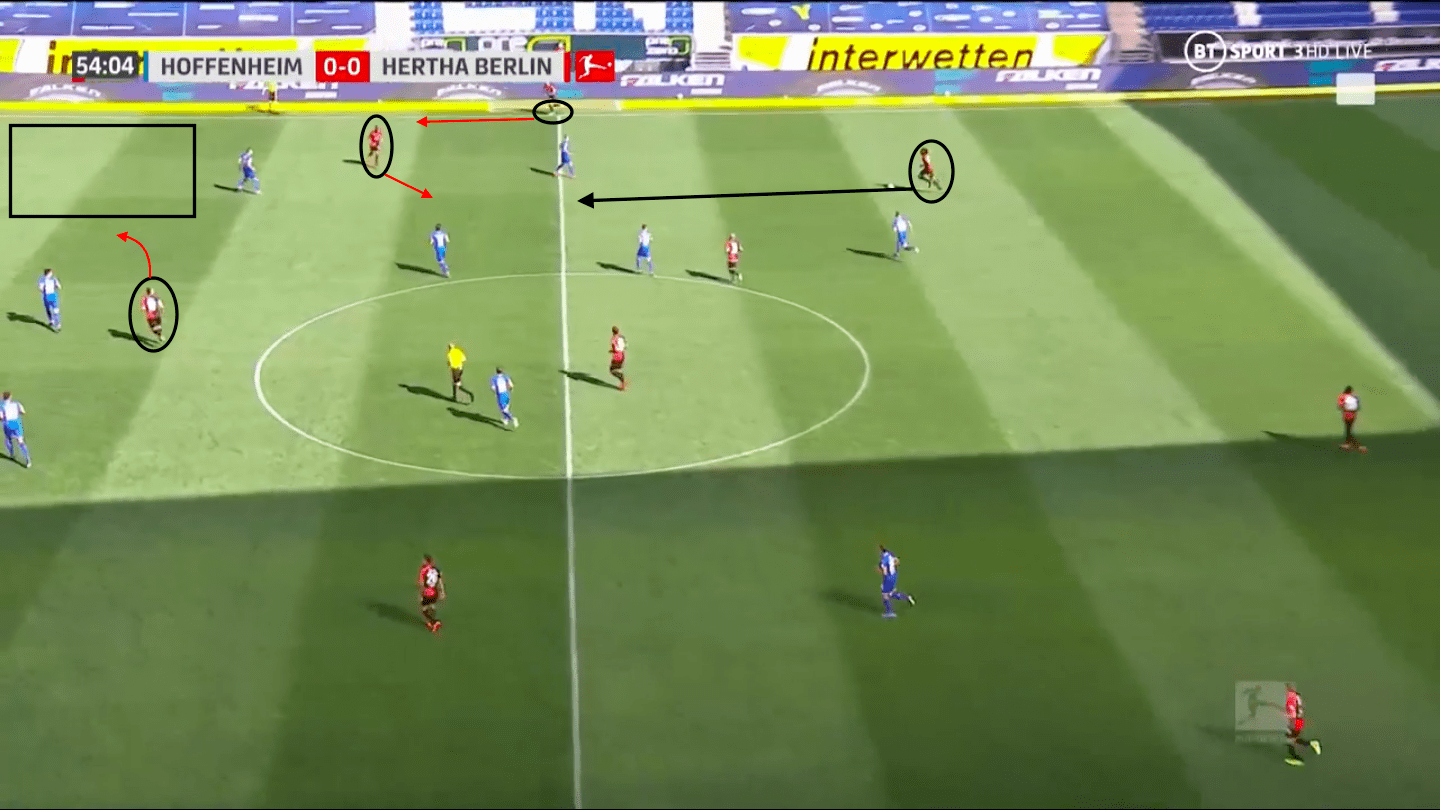

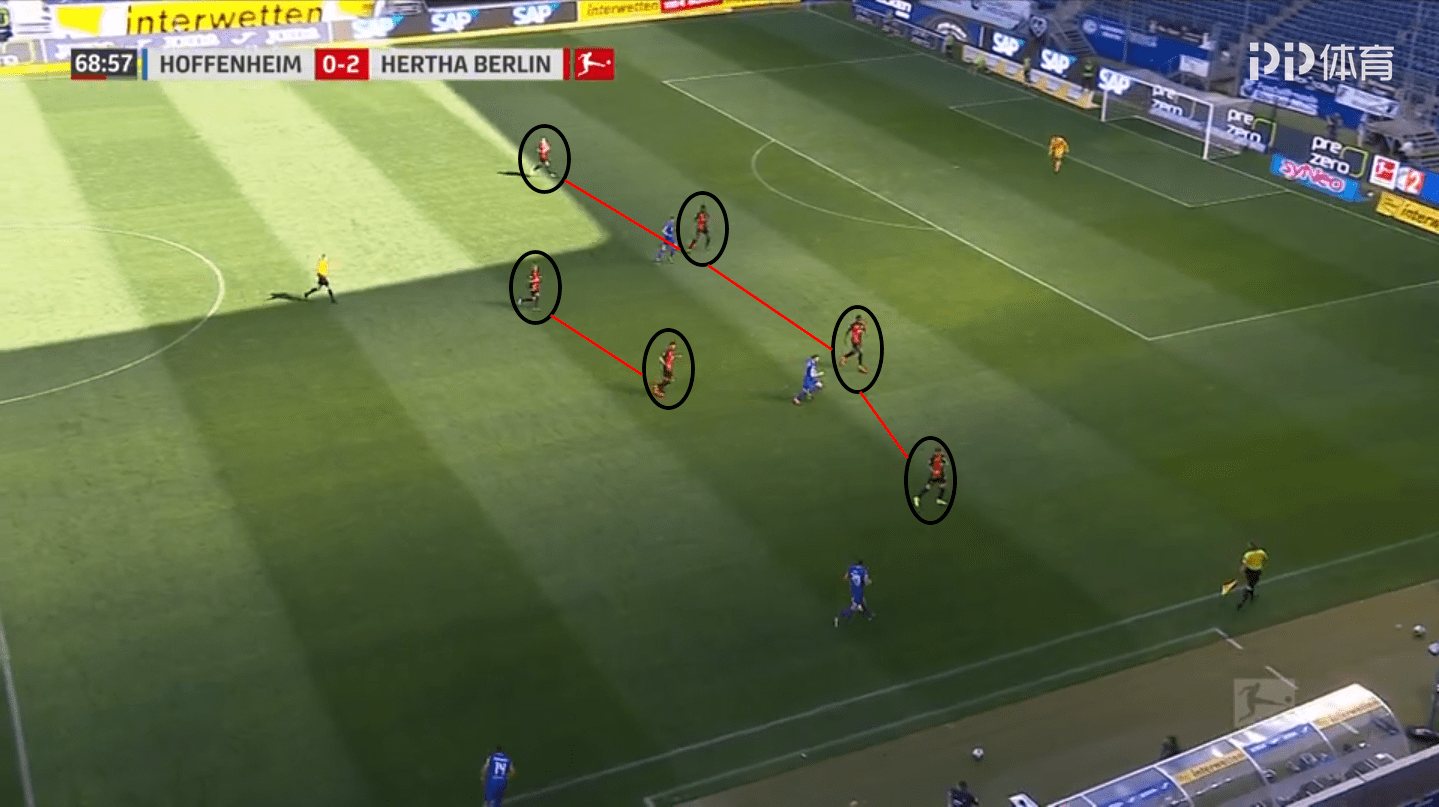

In the second half against Hoffenheim, Labbadia’s defensive unit tactic has been severely imposed onto the Hertha players as we see below.

Before Labbadia’s reign at Hertha BSC, their xGA average per 90 stood at 1.78.

For the season, their xGA was 40.5.

These staggering statistics are something that needed to change if Hertha were going to make their second half of the season anything to remember.

As we see in the image above, they are 2-0 up against Hoffenheim and their defensive organisation is seen once more.

It should be noted that each player has a role in the Pressure, Cover and Balance principle of defending, which is clearly seen above, with Plattenhardt providing the pressure, Torunarigha providing the cover and Boyata balancing the defensive line.

Hertha’s xGA per 90 for the Hoffenheim game stood at 2.6, however dropped increasingly for the game against Union, standing at 0.3.

It could well be argued that the defensive organisation under Labbadia has significantly decreased their xGA per 90, compared to Nouri and Klinsmann.

This, as well as their compactness of not splitting apart or being stretched, made it difficult for Hoffenheim to find any way back into the game.

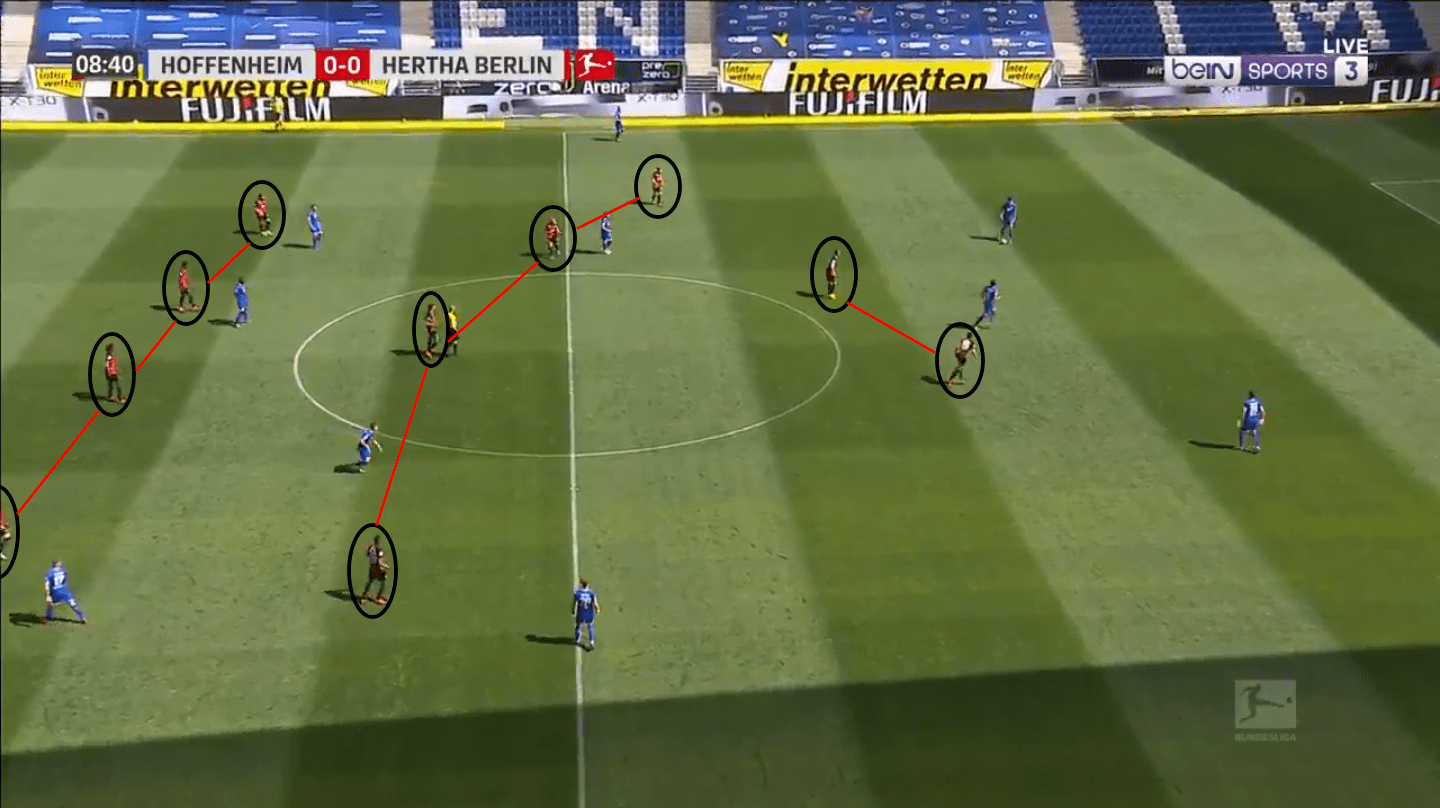

Even with the score being 0-0, Labbadia’s defensive out-of-possession work is something that has definitely improved Hertha’s performance.

As Hoffenheim look to progress the ball forwards, Hertha make it very difficult for them with their compactness and 4-4-2 shape out of possession.

This forced Hoffenheim to play to the wide areas, rather than playing direct centrally which they are keen on doing.

Labbadia has well and truly improved Hertha’s defensive shape and makes them such a solid unit to break down.

This was something they needed going into the resumption of the league games and should see them keeping more clean sheets this season.

Conclusion

Before Labbadia took over, Hertha BSC were in real trouble.

Having changed their manager five times within the space of a year, Hertha were conceding mass amounts of goals and failing to produce any sort of form home and away.

Their defensive organisation as well as their lack of movement in their build-up play found themselves with a huge mountain to climb once the season resumed after the pandemic.

Since Labbadia has taken over, although they have only played two games at the time of writing, he has seen them score seven goals and conceded zero.

He has revitalised their campaign, making them more structured and hard to break down as a defensive unit, as well as using key players to their advantage in the build-up phase.

Comments