One of the most tactically-interesting matches of the Bundesliga was Bayer Leverkusen coming to Borussia Park to take on Borussia Mönchengladbach. Two points separated the two teams prior to the match, with Gladbach holding onto third place. After Leverkusen’s 3-1 victory, they now sit in third place, leapfrogging Gladbach, who now sit a point behind Leverkusen.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics used by both Peter Bosz and Marco Rose in their Bundesliga match. The analysis will provide an explanation of what both clubs attempted to do in order to earn the three points in a race for a UEFA Champions League place.

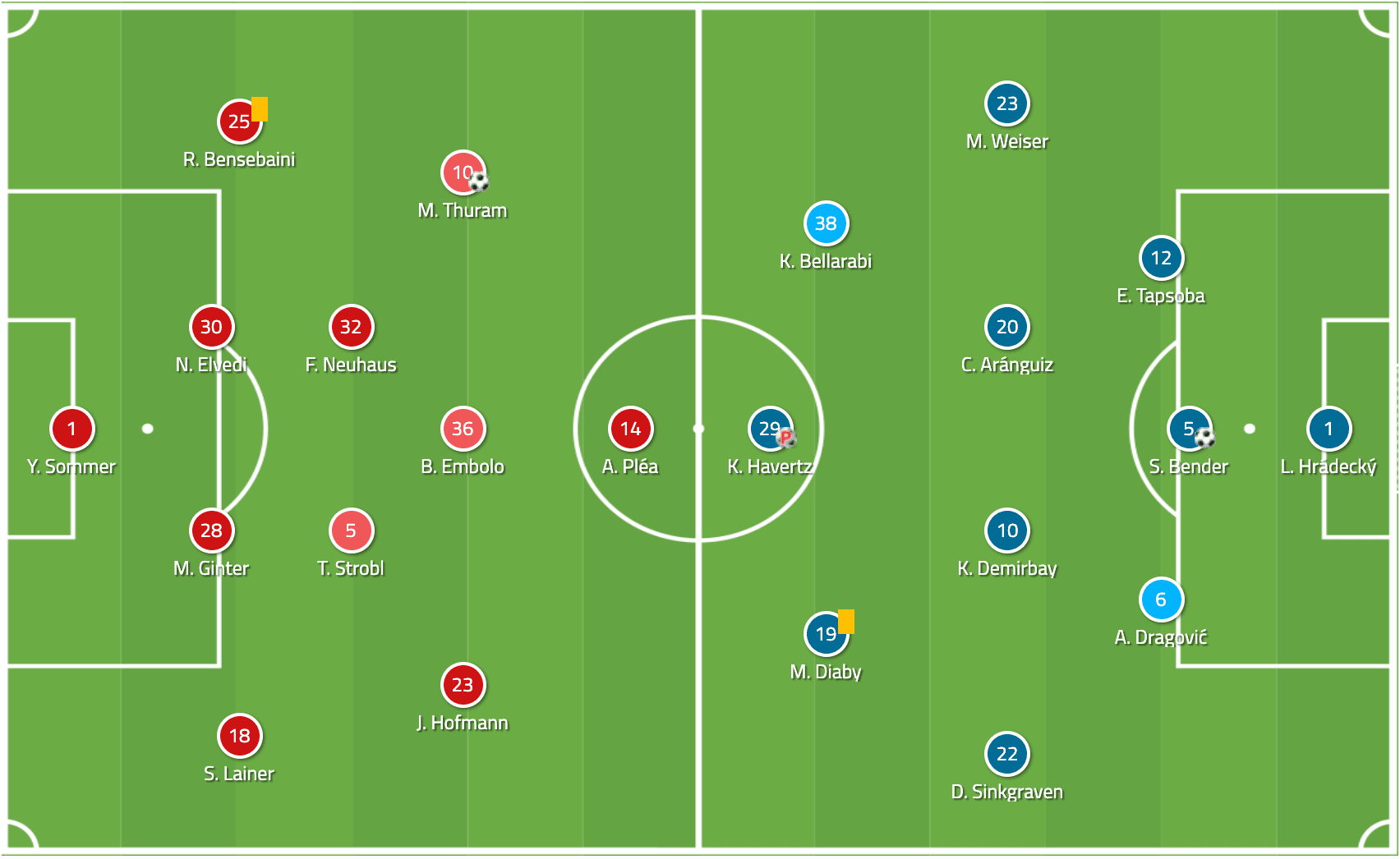

Lineups

Marco Rose sent his men out in a 4-2-3-1 formation with Yann Sommer in goal and Ramy Bensebaini, Nico Elvedi, Matthias Ginter, and Stefan Lainer forming the back line, with Elvedi and Ginter as the two centre-backs. Florian Neuhaus and Tobias Strobl were the two holding midfielders with Breel Embolo playing as the attacking midfielder, although he was subbed off early with an injury and was replaced by Lars Stindl. Marcus Thuram worked on the left-wing, Jonas Hofmann worked on the right-wing, and Alassane Pléa was the lone striker.

Peter Bosz’s squad started the match in a 3-4-3 with Lukáš Hrádecký in goal. In front of him were the back three of Aleksandar Dragović, Lars Bender, and Edmond Tapsoba. Daley Sinkgraven worked on the left side of the pitch while Mitchell Weiser began on the right with Kerem Demirbay and Charles Aránguiz patrolled the centre of the park. The front three consisted of Moussa Diaby, Kai Havertz, and Karim Bellarabi.

Leverkusen’s shape allows an effective press

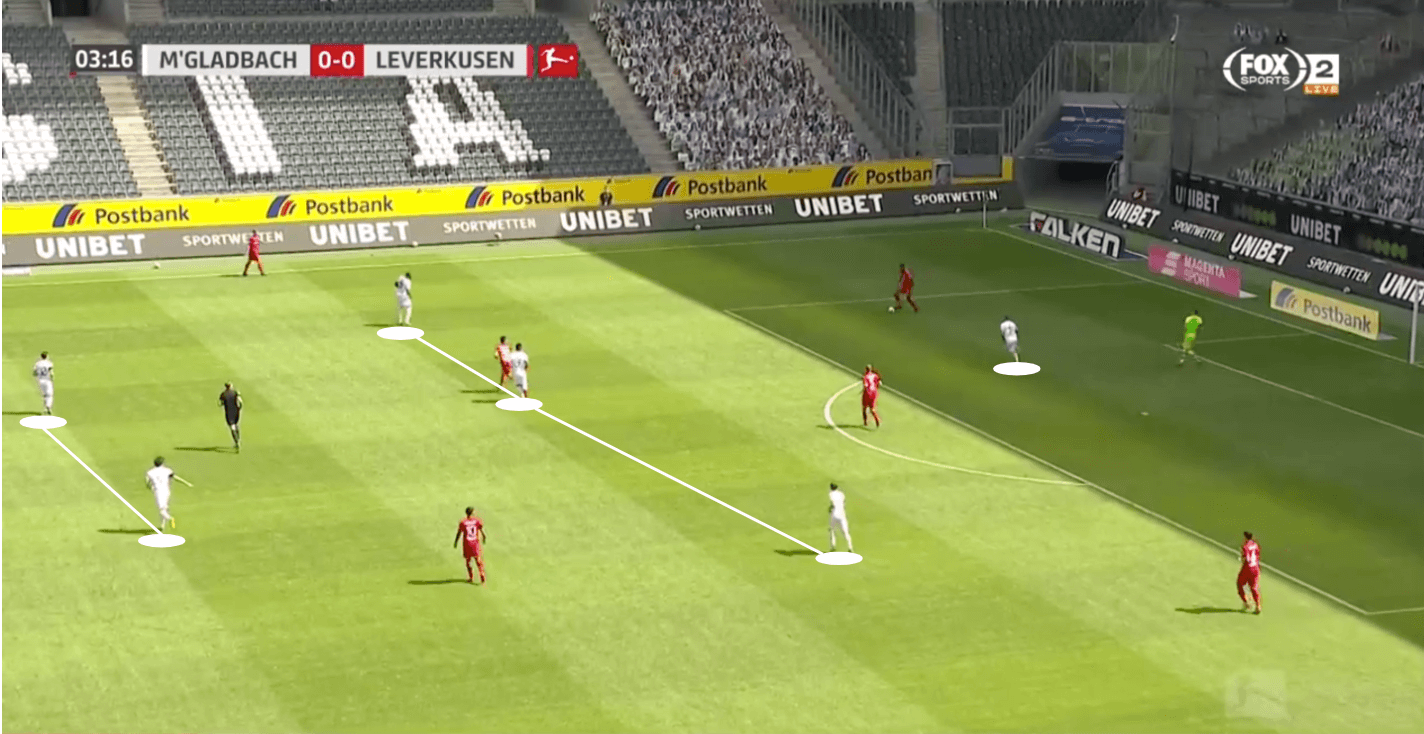

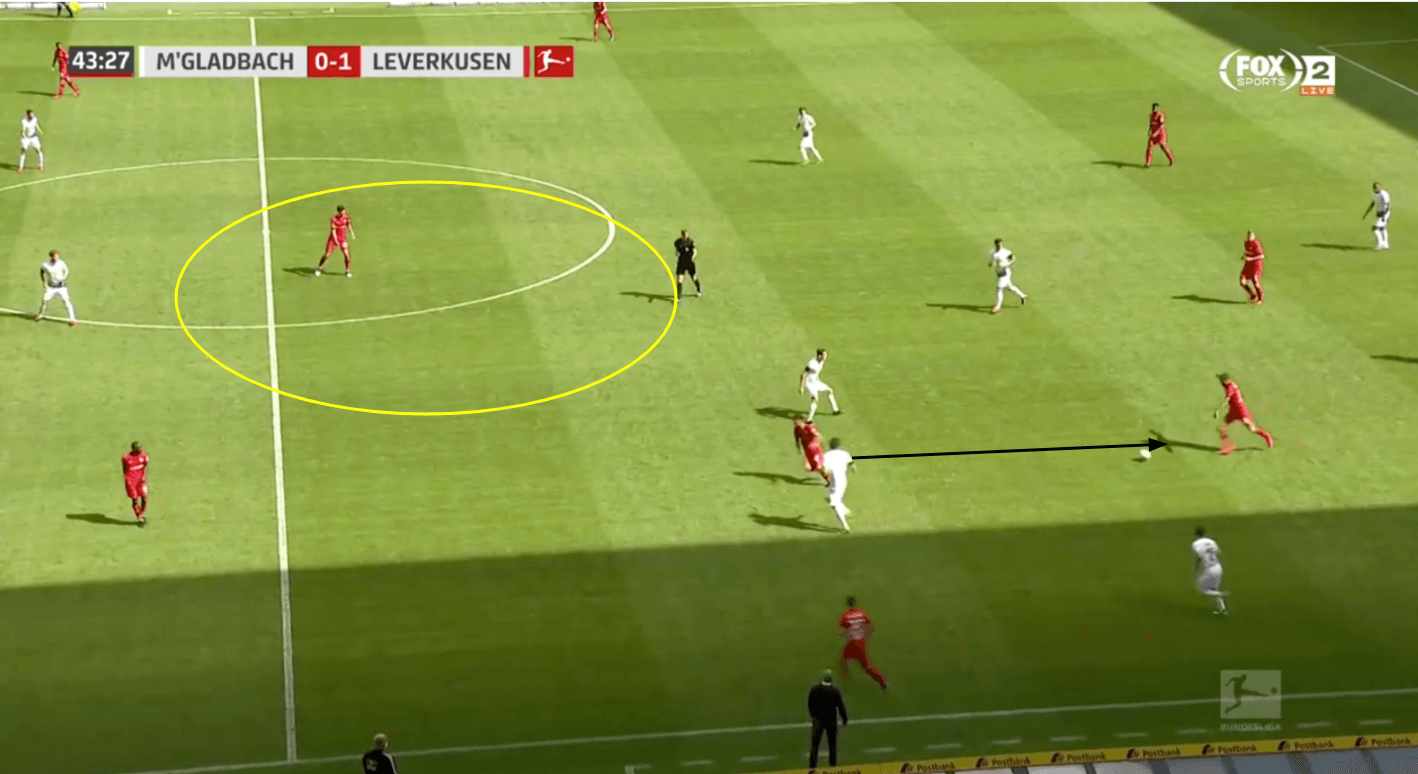

For the first half, Leverkusen seemed to control most of the match, and a lot of that had to do with their 3-4-3 lineup. While Leverkusen were certainly wary of committing too many men forward, their front seven really frustrated any attempts that Gladbach made to either play out of the back or move the ball vertically to a teammate. Initially, the front three of Diaby, Havertz, and Bellarabi frustrated the four men tasked with the build-up for Gladbach: Sommer, Ginter, Elvedi, and Neuhaus. Diaby and Bellarabi would mark the two centre-backs while Havertz marked Neuhaus, leaving Sommer with the ball at his feet with very few options. Consequently, Strobl would drop down to attempt to break the defensive advantage.

As Strobl looked to create a numerical advantage, he was followed by the Bayer midfielder, Demirbay. While both centre-backs, Ginter and Elvedi, appeared to be open, Leverkusen’s wingers would certainly close down those larger gaps quickly, winning the ball back in an advantageous position. As a result, Sommer had no options to play the ball, so he was forced to send it long, which allowed Bayer to regain possession quickly and build another attack.

Gladbach continued to look to add numbers in order to break Bayer’s press, with the three central midfielders, Neuhaus, Strobl, and Stindl, executing positional rotations in an attempt to create space for a teammate.

As Gladbach layered in more options for their back line, the front three of Bayer continued with their same press, which was now supported by more midfielders. Neuhaus dragged Havertz with him as he moved away from the ball, allowing Stindl to check down to receive the pass. However, Stindl was followed closely by Demirbay, whose pressure forced Stindl to return the ball back to Sommer, who then had to search for new passing options. While this pressing shape served to frustrate Gladbach, Bayer’s 3-4-3 shape also caused problems for Gladbach defensively.

Havertz as a false 9 option

Kai Havertz is primarily an attacking midfielder, but technically lined up as a centre-forward against Gladbach. However, the frequency with which he dropped into the midfield in order to provide support saw him highlight his abilities to dip into a false 9 role.

Gladbach’s 4-2-3-1 press meant that anytime they pushed too highly or weren’t connected properly, Havertz could drop into the space between the lines and receive the ball. If Neuhaus or Strobl shifted over to mark him, it would create a free man in the centre of the pitch, allowing Leverkusen to build-up successfully throughout the first half. If Neuhaus and Strobl tried to drop lower on the pitch to eliminate Havertz receiving the ball from a vertical pass, this would create more room for the other Leverkusen midfielders to receive the ball. This shape allowed Leverkusen to maintain possession more consistently and attack Gladbach more consistently in the first half.

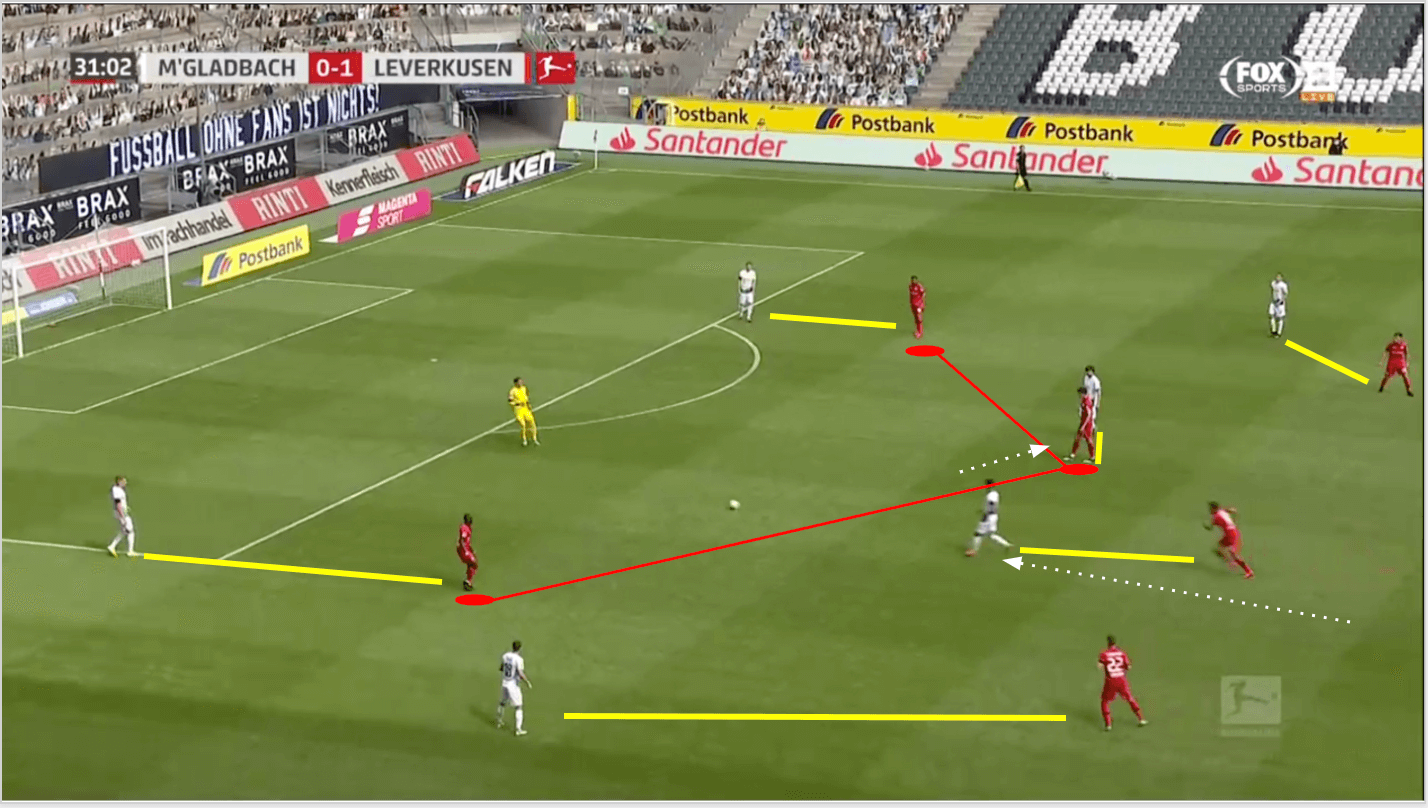

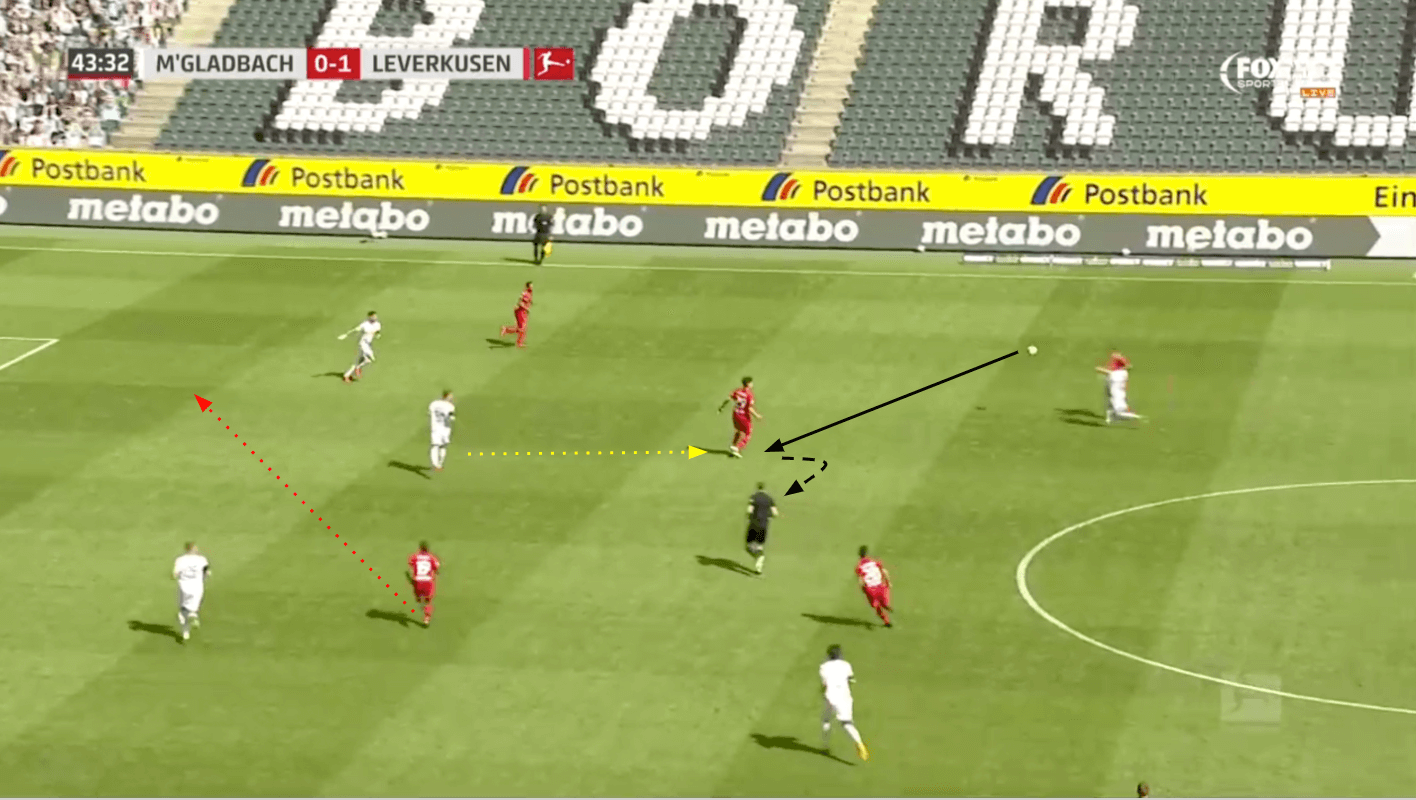

Leverkusen’s first goal stemmed from a misplayed pass, but it also had to do with Gladbach’s centre-backs not being in the correct position. The reason for their poor positioning was simple: Havertz had dropped down into the midfield.

In the image above, Elvedi, a centre-back stepped forward to follow Havertz as he dropped into the midfield to support his teammates. As Elvedi did, a large amount of space between him and his partner, Ginter, opened up. As soon as the ball found its way to Demirbay in the centre, Havertz began his third man run. Ginter was not in a position to press Demirbay because he was protecting the central space. If he had Elvedi with him, they could have managed the situation better, but Elvedi had followed Havertz too far up the pitch. Demirbay played his pass to Bellarabi, who took a touch and played Havertz in on goal, where he finished coolly.

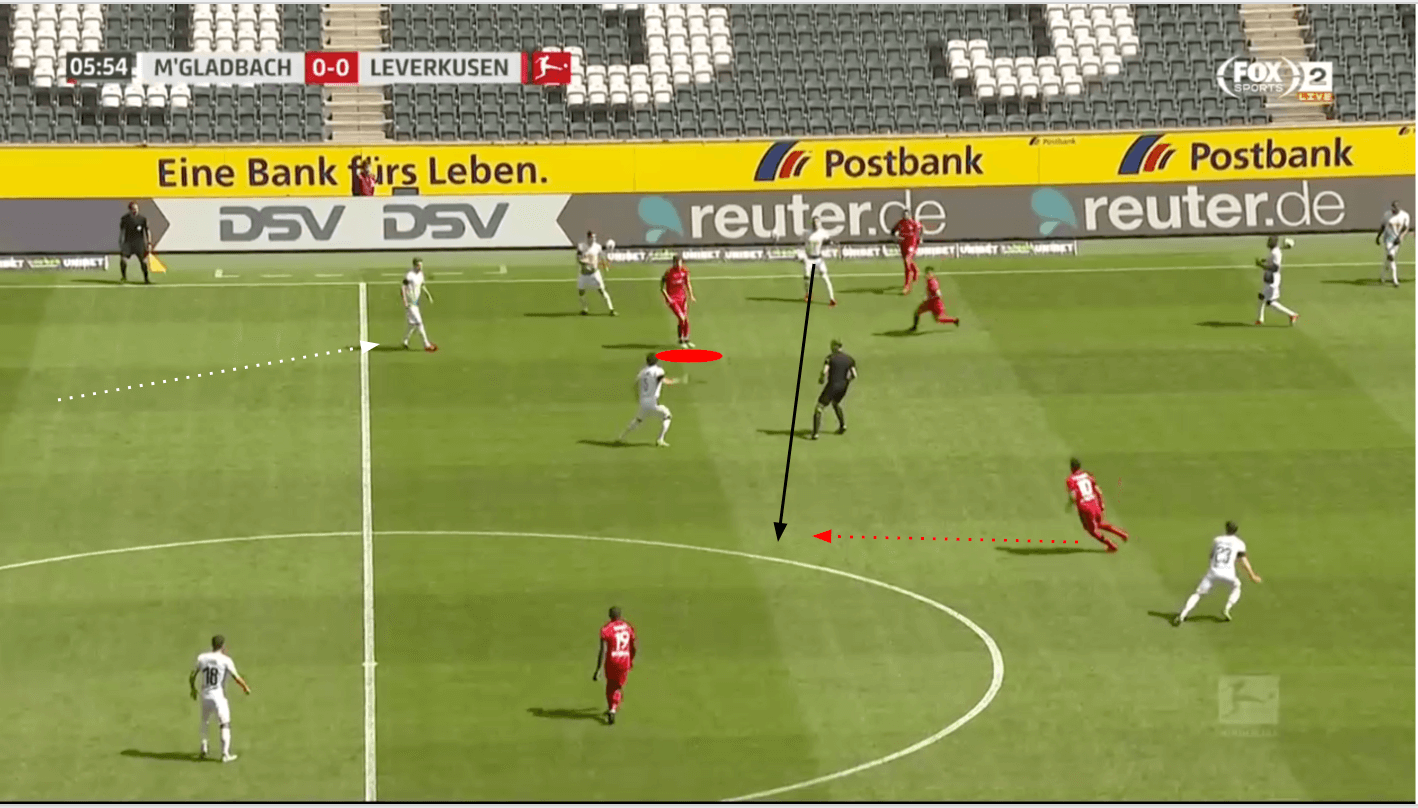

Havertz continued to cause problems for Gladbach’s 4-2-3-1, especially when Gladbach overcommitted or lost their organisation. The confusion caused by Havertz’s willingness to drop into the midfield could have been exploited more, but ultimately it wasn’t. Towards the end of the half, Gladbach had committed six men forward in their press.

This was the perfect time for Havertz to drop into the midfield and receive the ball. As he went, Ginter’s first reaction was to follow, but he ultimately didn’t, because this would have created huge holes in Gladbach’s defence that Diaby or Bellarabi could exploit. Ginter made the right decision in staying with his line, but this allowed Havertz to be able to receive the ball in a lot of space with time to turn and dribble at the defence. In this instance, the ball was actually sent to the opposite side of the pitch, but the problem for Gladbach still persisted.

Havertz had switched over to the right side, so he was now Elvedi’s responsibility. Elvedi cannot make the move highlighted by the yellow arrow because if he does, he would create all sorts of space behind him for Diaby to run in behind. Instead, Elvedi had to hold his line, which allowed Havertz to turn, face the goal, and ultimately play a diagonal ball that led to a chance for Leverkusen.

Gladbach’s adjustment to Bayer’s shape

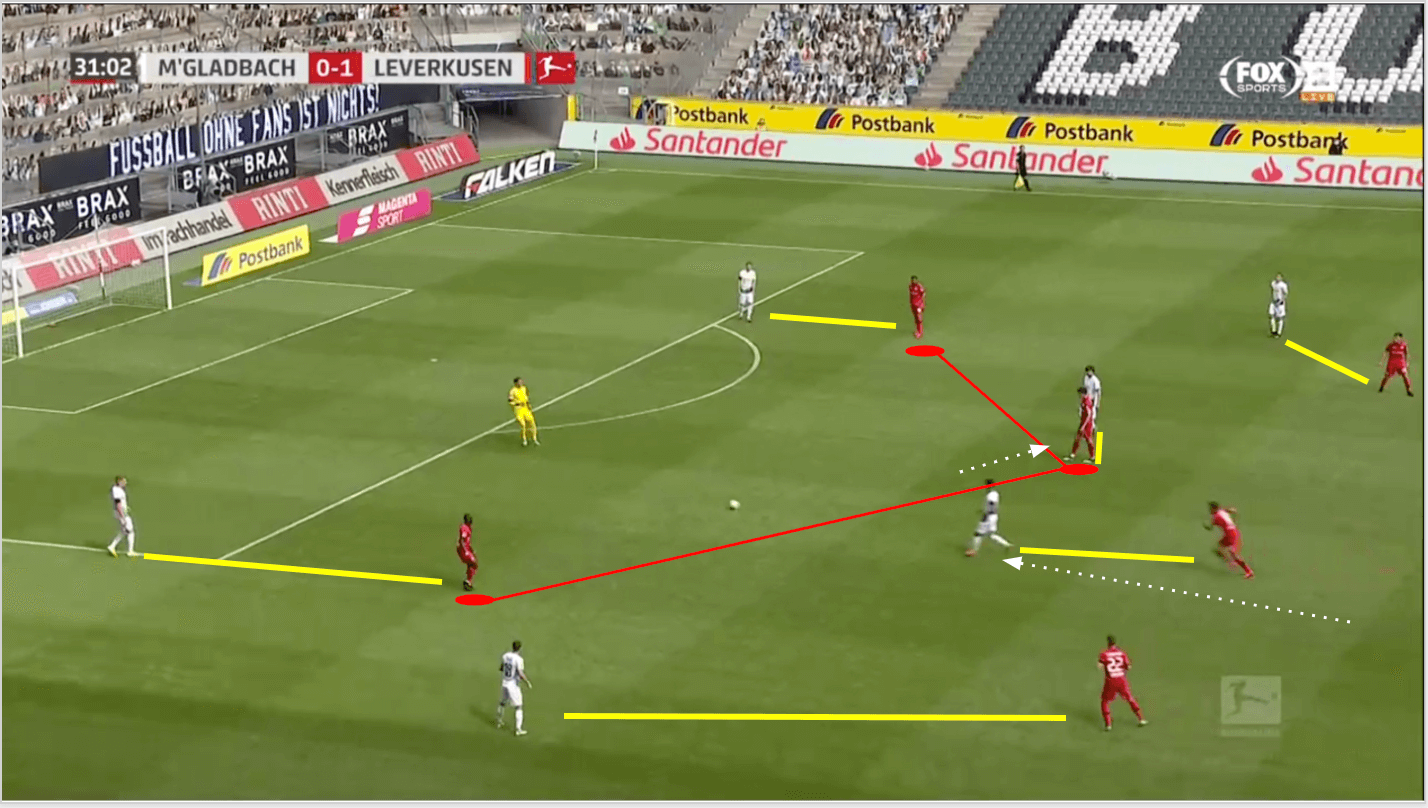

The first half for Gladbach saw them pressing in a 4-2-3-1 and then dropping down and defending in a 4-4-2, where they did well to repel most of Leverkusen’s attacks. However, they did not see much of the ball and could not afford to let Havertz run as free as he did in the first half, so they switched to a 3-4-3, which allowed them to press more effectively, which in turn allowed them to see more of the possession.

The front three for Gladbach stood on the line of the penalty area on goal kicks, signalling their intentions to press intensely. Gladbach’s wingers allowed Bayer’s outside-backs to have space, essentially luring the centre-backs into playing them the ball. When the pass to the outside back was clearly going to happen, Gladbach’s wingers would press intensely, often causing them to send the ball long over the top, where Gladbach would win possession and build from there. This shift in pressure from the first half caused Bayer to struggle to maintain possession consistently, as they struggled to play out of their own half. In fact, Leverkusen’s other two goals stemmed from a penalty won off of a long through ball and a set-piece.

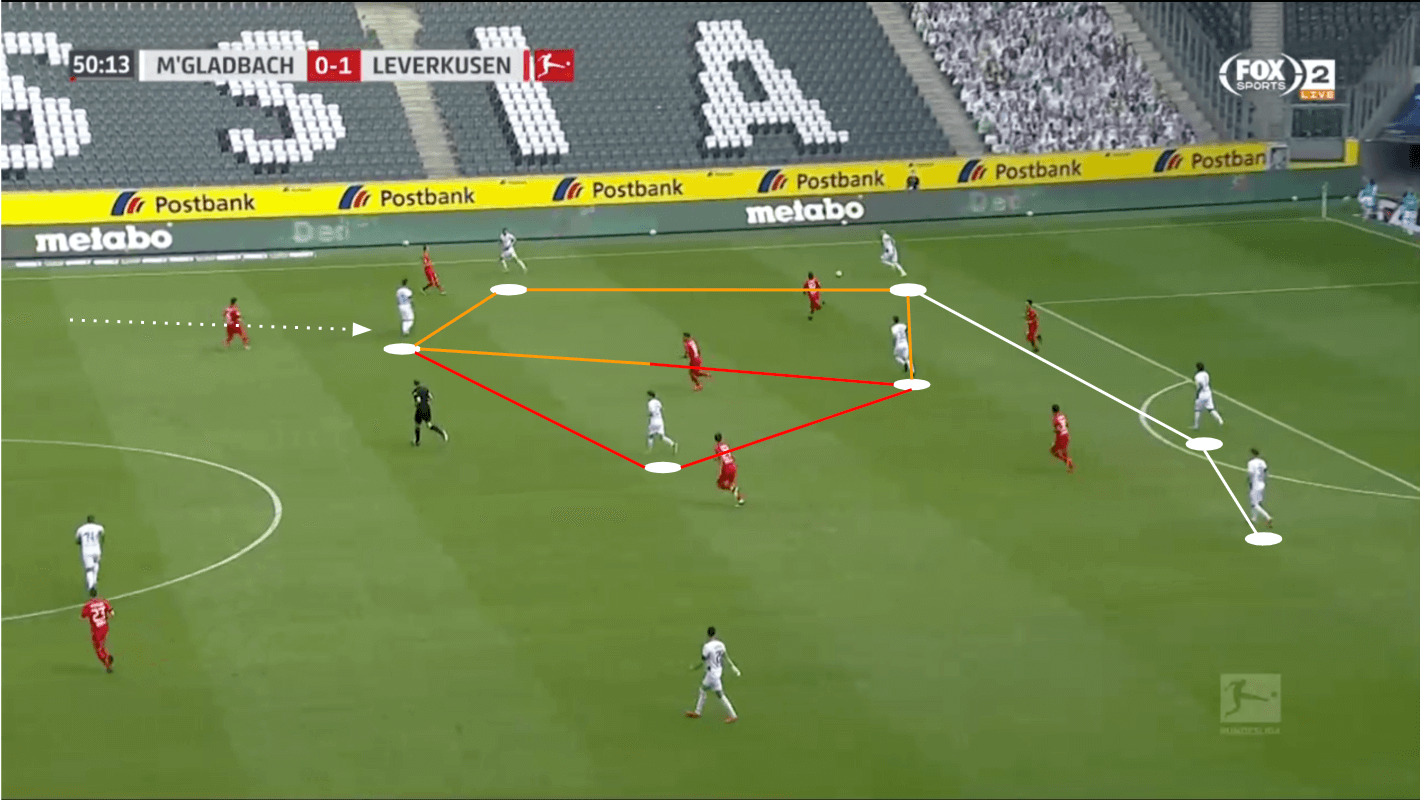

The change in their shape and the inclusion of the back three also allowed them to create a more successful buildup, resulting in better attacking chances. Of course, the back three does stretch a pressing team’s front three and allows for more passing lanes to open up, amongst many other things. This stretching of Bayer’s front three combined with their own attacking wingers dropping down to create overloads allowed Gladbach to progress the ball smoothly.

In the image above, Hoffman dropped into the midfield space, creating a numerical overload in two places. The first is the orange diamond on the right side, where it is now 4v3. The second overload is in the centre of the pitch, where Hoffman can combine with the midfielders to create a 3v2 overload. Finally, Hoffman’s move towards his own goal opened up space behind him, where Thuram could run into if Gladbach wanted to play a long ball. If Gladbach switched the field of play, Alassane Pléa could drop down and provide the same support that Hoffman offered.

Vertical passing creates chances

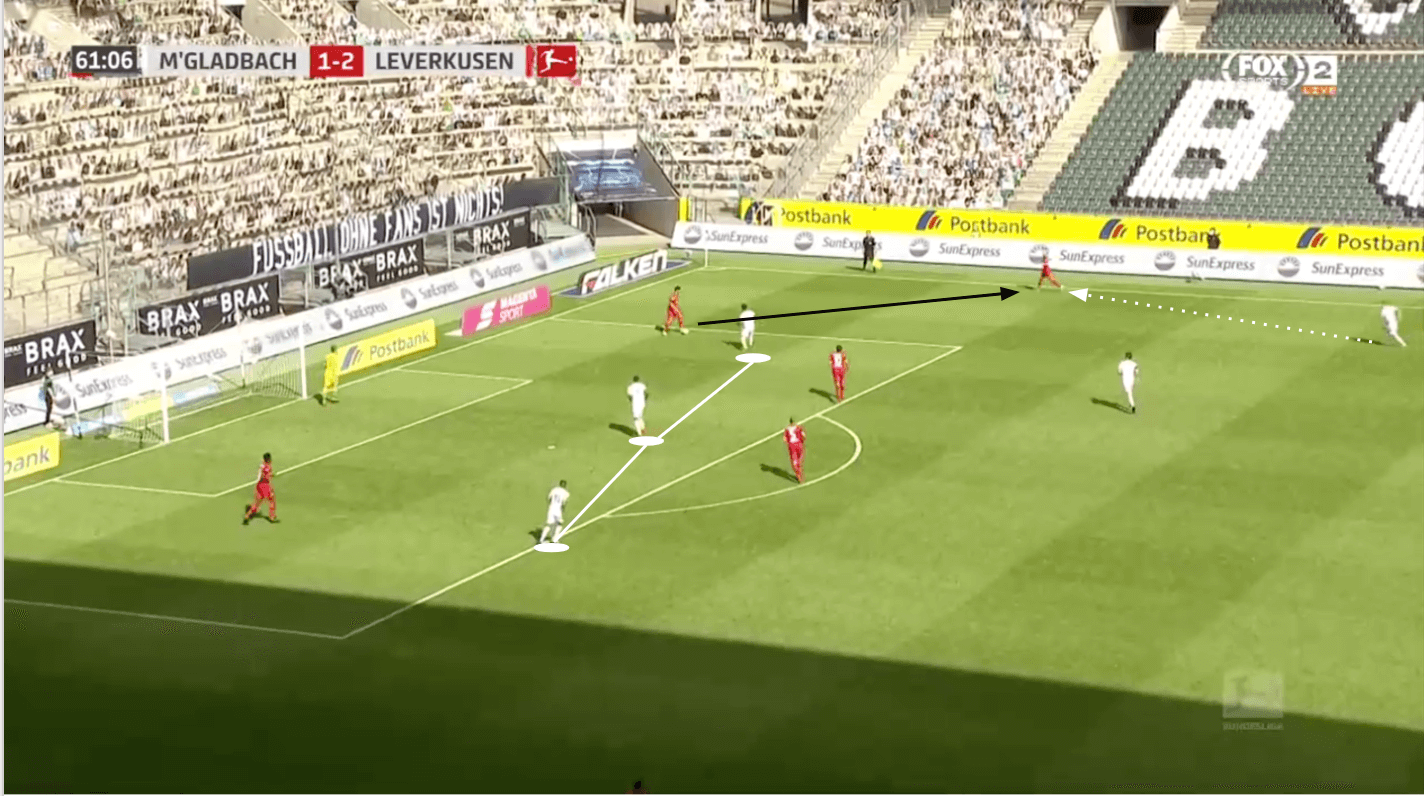

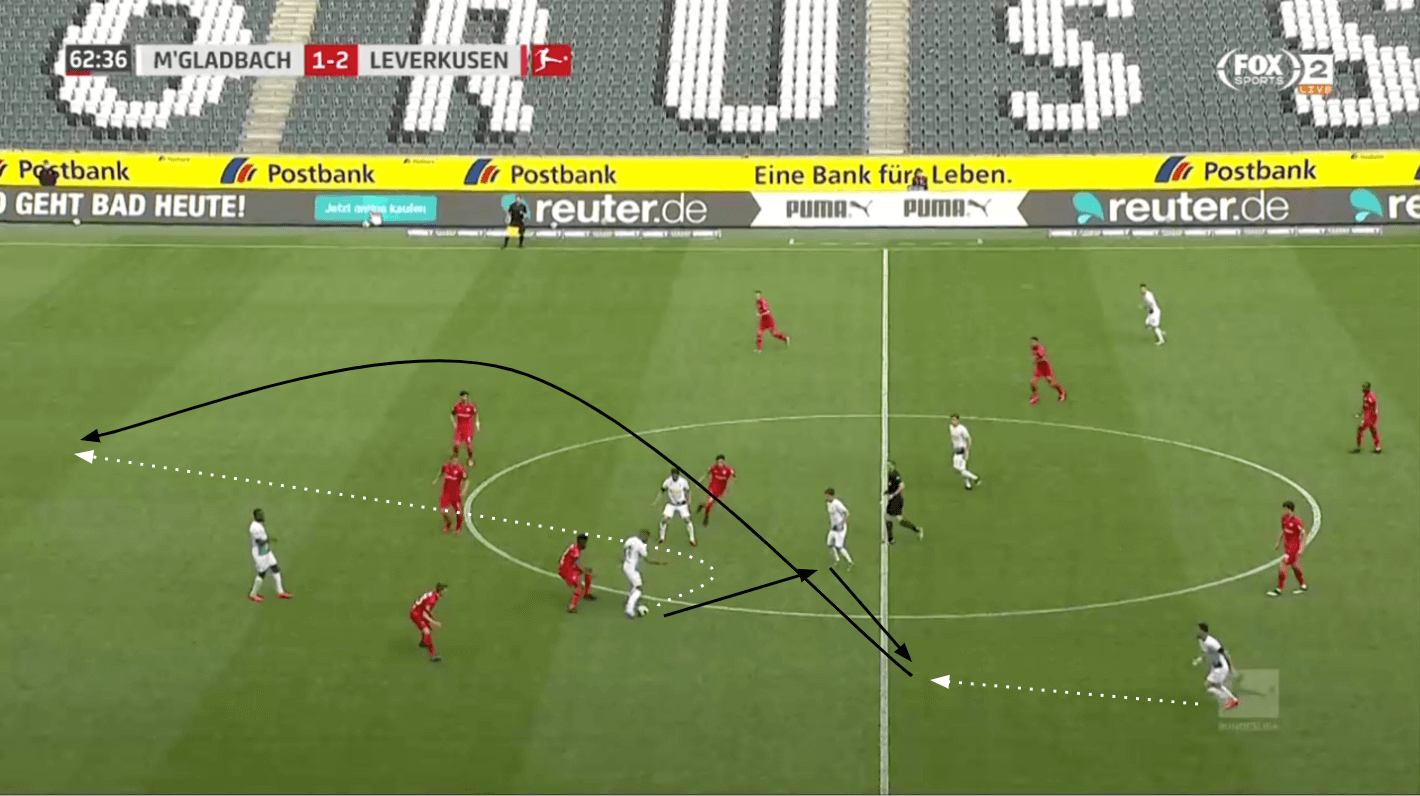

With their build-up more consistent, Gladbach were able to play their more direct, vertical passing now that they had men in the right spot, able to lay off long passes in order to play another vertical one. Their goal came from the space generated from their build-up attracting Leverkusen’s press.

Yann Sommer sent a long ball to Thuram, who chested the ball backwards to a forward-facing teammate, in this case Hoffman, who could ideally play another vertical pass. However, Hoffman was under pressure from Leverkusen, so he played his first touch to Pléa, who was open in space. Thuram’s run saw him find space to the right of Aleksandar Dragović, who was out of position because he had followed Hoffman’s original run back into the midfield as previously discussed.

Bayer’s high defensive line certainly made Gladbach’s verticality more dangerous. Gladbach again was able win a ball quickly, and find an open man away from pressure to play someone through into space.

Pléa gained possession and quickly laid the ball off to a teammate. This passing pattern was incredibly similar to the one just explained, where the ball went backwards and then out of pressure to a man who was open in space. As Ramy Bensebaini arrived to receive the ball, Pléa was already between the two centre-backs, running into the space behind them. The pass to Pléa was perfect, but his run was made a bit too early, and he was caught offside.

Gladbach continued to vertical passes to break down Leverkusen’s defence. This verticality was made possible because of the changes that they had made at half-time that allowed them to see more possession and continue to create chances.

Conclusion

In the end, Gladbach were unable to convert their chances, despite having multiple opportunities to equalise. Leverkusen’s ability to finish their chances ultimately saw them earn all three points. The win put them one point ahead of their opponents, with plenty of matches still to be played in the Bundesliga season. Leverkusen still find themselves four points behind Borussia Dortmund, who are still four points off of Bayern Munich.

It’s what they refer to as an “English week” in German football, with both teams having a quick turnaround before matches on Tuesday. Leverkusen will welcome Wolfsburg to the BayArena while Gladbach will travel to take on Werder Bremen. With seven matches still to go, both teams will need strong results on short notice if they want to keep up in the race for the top four Bundesliga spots.

Comments