If there was ever any club that has stayed in the top echelons of football, it has to be Bayern Munich. The German giants have dominated the Bundesliga and always do it with a stamp of authority. Their runs in the Champions League have been slightly less glorious. After their 2013 win, the highest the Germans have gotten is the semi-finals. Worse so, last year the Bavarians went out in the Round of 16. It is safe to say while Bayern Munich were a force to be reckoned with, they had some ways to be a mainstay force in the Champions League.

In July 2017, veteran Matthias Sammer left the club as the sporting director and former player Hasan Salihamidžic was appointed as the sporting director. While the road under Salihamidžic has not been as transformative as Sammer, there seems to be a more long and structural process at play with Bayern.

The Bavarians’ turnaround from their poor performance at the beginning of the 2019/20 season, under Niko Kovač, to a confident winning machine under interim, and then made permanent, coach Hans-Dieter Flick drew the world’s attention.

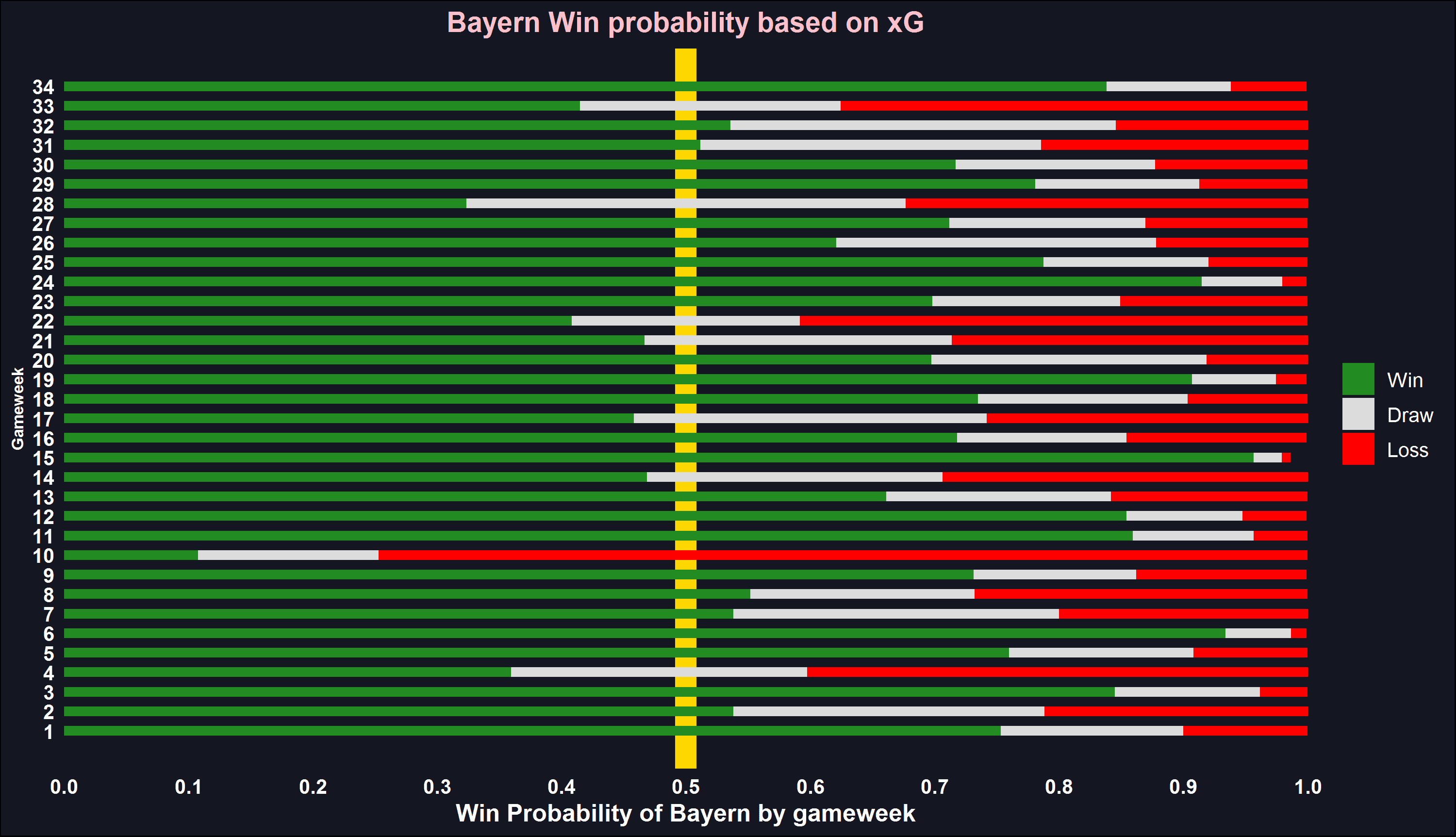

Based on their xG, this graphic shows the win, draw, and loss probability for Bayern Munich per game week. Kovač’s resigning loss is in Gameweek 10 where we see Munich had a win probability of 10%. Flick’s reign starts after Gameweek 10 and we see that Munich only had a win probability less than 50% 6 times. Flick’s arrival has made them a ruthless winning machine.

The secret to Bayern’s success stems to Flick’s coaching and German efficiency off the pitch. In the last three years, Salihamidžic and Bayern have gone about structuring Bayern. In this data analysis, we’ll analyse Bayern’s transfer revolution through the use of data and statistics and find out how the Moneyball approach has landed in Munich.

Transfers and Money

Death, taxes, and Bayern Munich stealing the best talents from their rivals in the Bundesliga are football’s given constants. Transfers like Robert Lewandowski, Mats Hummels, and Mario Götze are just some of the most famous examples where the Bavarians have gotten top talents directly. This method, while unconventional, ensured that Bayern’s squad always had players who were in their peak or who had already developed.

However, as football smartened, so did Bayern Munich’s transfer strategy.

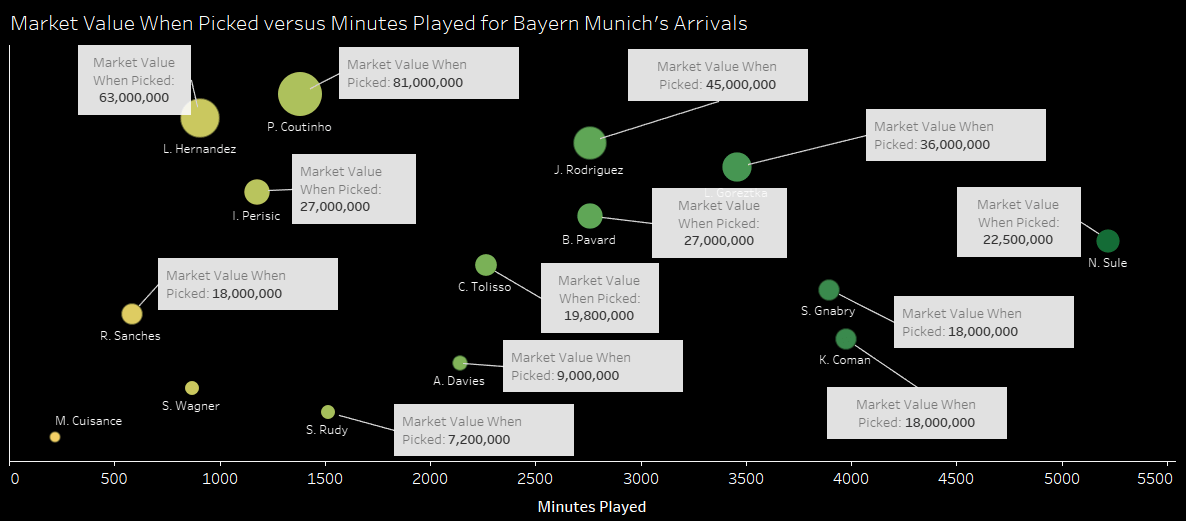

Analysing all of their arrivals since 2017 and looking at how many minutes they played and the market value when they were picked – shown in the size of the dot – we see that many of the transfers have played a significant amount of minutes. The likes of Serge Gnabry, Kingsley Coman, and Leon Goreztka spent a majority of minutes – indicated that they were perfect fits – and we see that these players had small or relatively average market value when picked.

This characteristic is also seen in Liverpool seeing how they got players like Sadio Mane, Roberto Firmino, Mohammed Salah, Andy Robertson, and Trent-Alexander Arnold who have played a lot of minutes and had relatively average or small market values when picked up.

This strategy is something of out of the Moneyball handbook – an approach that urged clubs to look where most clubs didn’t, find players who fit their style either through individual or aggregated measures and buy them at relatively average or small prices. Of course, Liverpool improved the model by mixing Moneyball signings with few, world-class players that allowed them to elevate their game and reach the upper echelon.

Bayern Munich seemed to have adopted this approach as signings like Gnabry and Coman are also complemented by big signings like Lucas Hernandez or loaning big players in the case of Phillipe Coutinho. This is all done with the customary German touch.

Now that we know of Bayern Munich’s strategy – let’s actually dive into the data and see how their transfer revolution has helped them leapfrog other clubs.

Bayern’s Squad Age Profiles

Bayern Munich’s Moneyball strategy starts from 2017-18 – the first transfer window under Salihamidžic.

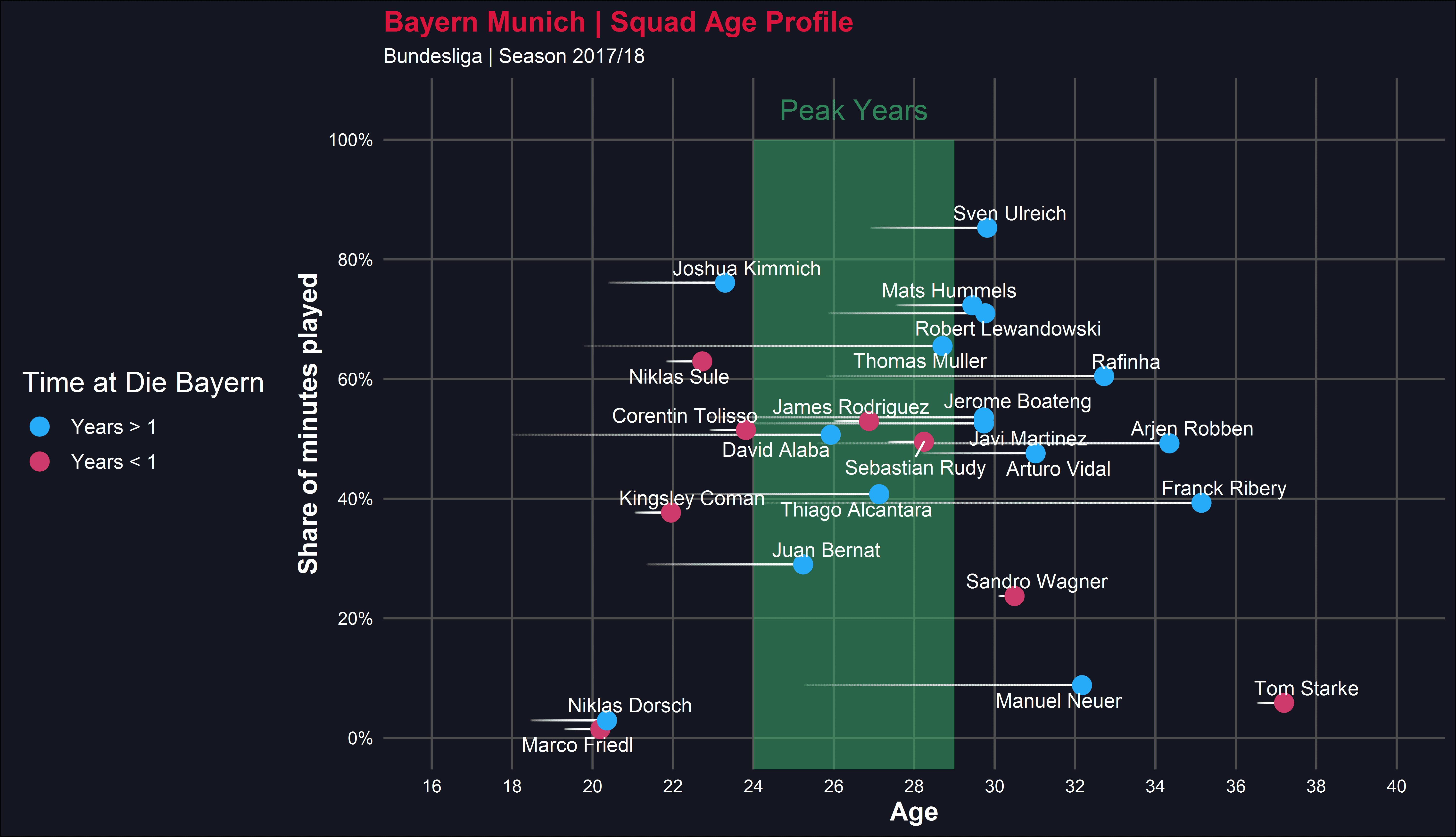

Here is Bayern’s 2017/18 squad age profile. We see Munich’s ageing squad as various players are years past their peak such as Arjen Robben and Rafinha. Salihamidžic’s transfers are shown in red and we see that most of them are either before their peak – Coman and Corentin Tolisso – while others are in the middle of their peak such as James Rodríguez.

To fully understand why this is important, let’s have a look at Bayern Munich in the 2018/19 campaign year.

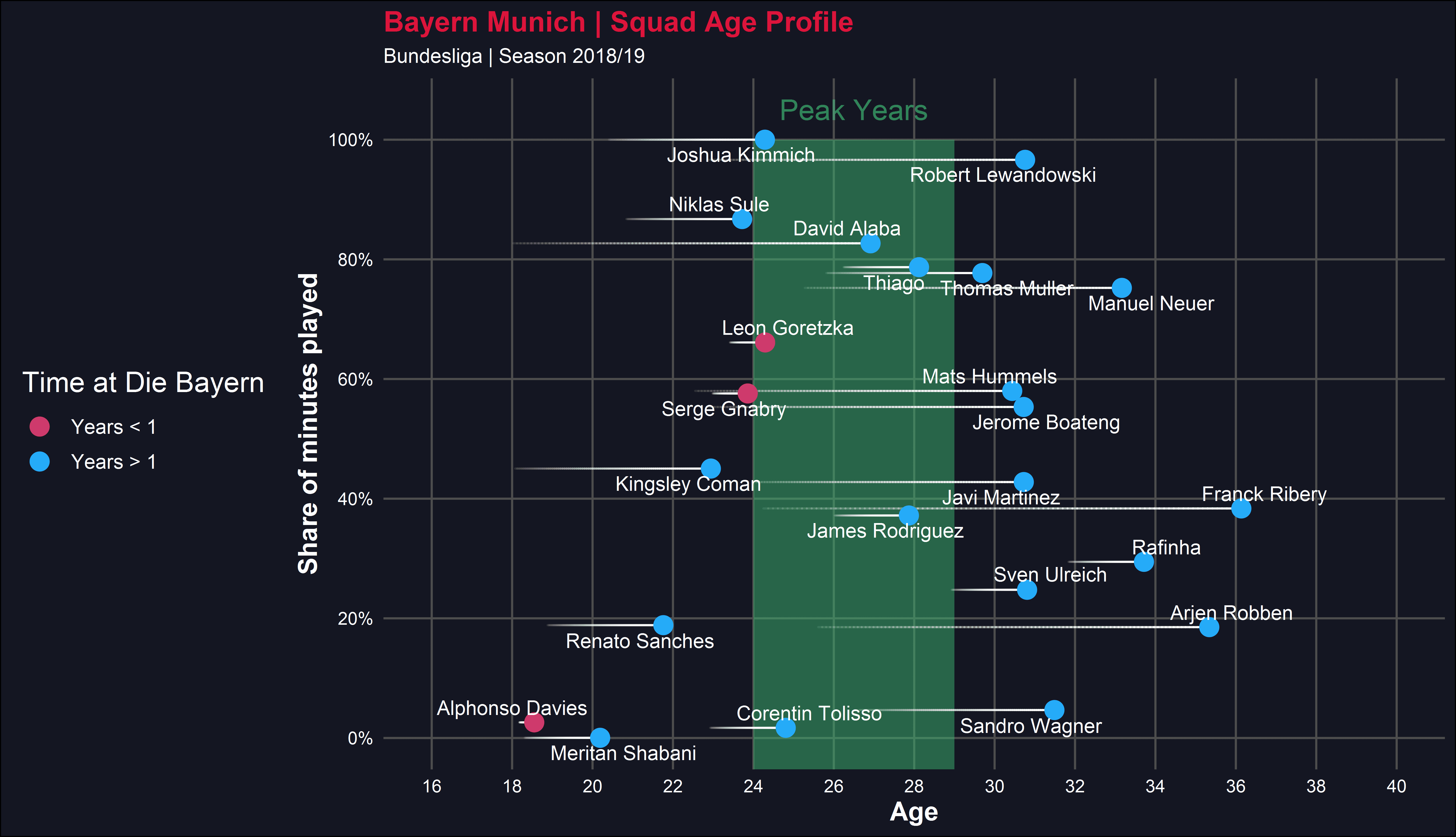

This squad age profile of Bayern’s 2018/19 season is very much staggered. There are still old players but we see that Bayern’s youth profile is slowly being built. The youth transfers of last year coupled with the transfers of the 2018/19 year, Alphonso Davies, Leon Goreztka, and Serge Gnabry (who had been signed in 2017 but was coming from a loan), lessened years off their squad age profile.

While Bayern quietly built their squad from the young ages to build them to use when they were in their peaks, the Bavarians were also dealing with the other side of the spectrum.

Many older players are often thought to be past it and are often sold. However, as Billy Beane from Moneyball teaches us, elder players often have one or two more squeezes. Not only this does maintain quality due to their experience but it allows the younger players to develop a bit more. This example is shrined in Gnabry and Davies who spent their first years at loans or in developmental squads allowing them to mature and become comfortable. The key with the old players is to use them in your transition – as Bayern have done – and to not give them big contract extensions.

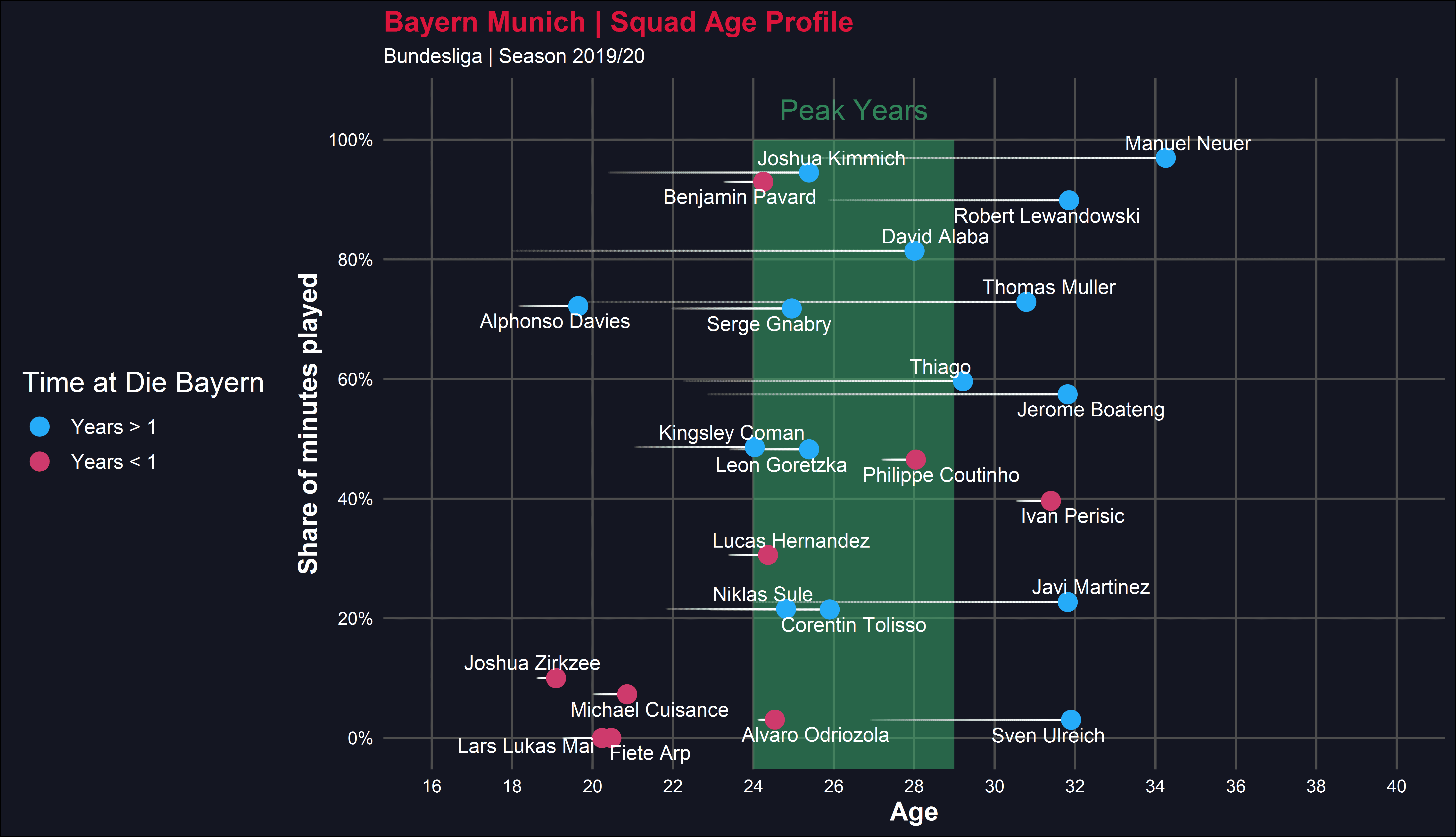

The big picture of this approach reveals itself in the 2019/20 season.

This is the 2019/20 squad age profile. Bayern’s oldest players occupy positions like central defensive midfielders and centre-backs with Lewandowksi and Thomas Müller being the only exception. Where in the previous years, old players held key positions, now players like Davies, Gnabry, Coman, Goreztka all clinch important positions in the team. By clearing older players from attacking positions, they have been able to make way for younger players and still retain experience in positions where the team can afford to have older members.

Bayern complement this development with transfers that are smart. For example, Hernandez, a talented full-back, was brought in for the full-back position. Coutinho, on a loan, bolstered their attack while Ivan Perišić – a talented winger nearing his end – added experience and has been important to Bayern for depth and experience.

This is all supplemented by the arrival of players that are far away from their peak like Joshua Zirkzee that allow Bayern to prepare themselves for the future just like they did before. In fact, the approach outlined in the years 2017-19 is being done now as we speak.

Right now, older players like Jérôme Boateng occupy the centre-back positions. As of writing this now, Bayern have brought Alexander Nübel (aged 23) for the replacement of Manuel Neuer in the goalkeeper position. Munich have recently gotten another steal as they bought PSG’s Tanguy Kouassi (aged 18) who will probably be replacing Boateng or Javi Martínez when they go out. Before Chelsea snatched up Timo Werner, Munich were heavily interested in Werner. As you can guess, he’d be the perfect replacement when Lewandowski would leave.

Clearly, Munich’s approach of buying youth players – more on how – and squeezing the last of older players has gotten them in shape to playing dangerous, attacking football. Where many clubs would hesitate in keeping older players aged 31 and more, the Bavarians have focused on that age pool to squeeze as much ability while in their transition.

This allows the development of the young players, allows Bayern to glean one or two more years from old players at a cheap price, and develops the team holistically.

While we now know the details of their development, how do they find the young players and old players at the prices they have bought them? This requires looking into player recruitment.

Player Recruitment from Bayern Munich

To look at player recruitment from Bayern, the best example would be to look at the window of the 2019/20 and 2018/19 season.

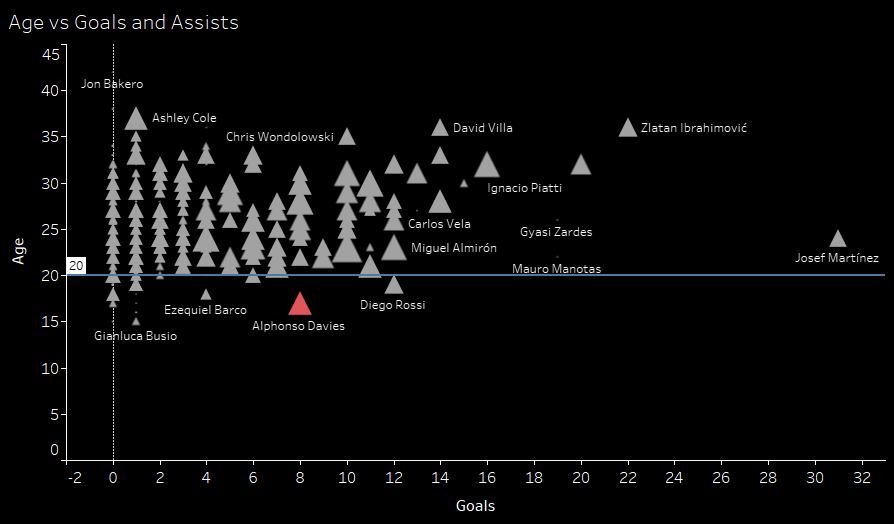

We’ll start off with the 2018/19 season with the most notable transfer – Alphonso Davies. While big clubs did express interest when he was in the MLS, none did so intensely as Bayern. Why? Well, when we have a look at the data from Davies’ season at the Vancouver Whitecaps in the MLS, it becomes easy to see why.

Here was how the 2018/19 season looked for the MLS. I have shown Age vs Goals and at first, Davies doesn’t pop out as much. His performance of 8 goals as an under-20-year-old was good but not as worthy. It is his assists, 9, paired with his energetic displays that caught Bayern’s attention. Doing so in a side that only recorded 53 goals becomes all the more noteworthy.

This attention to detail applies to Gnabry who signed in 2017 and was shown to loan to TSG Hoffenheim. There he quietly recorded 15 goals and assists with an xG of 0.42 per 90. If clubs had been intelligent, they would have spotted the talented winger but Bayern recognized their youth identification paying off and moved him to the official squad in the 2018/19 season. There he recorded 15 goals and assists again with an xG of 0.38 per 90 – a testament to Bayern’s scouting and recruitment.

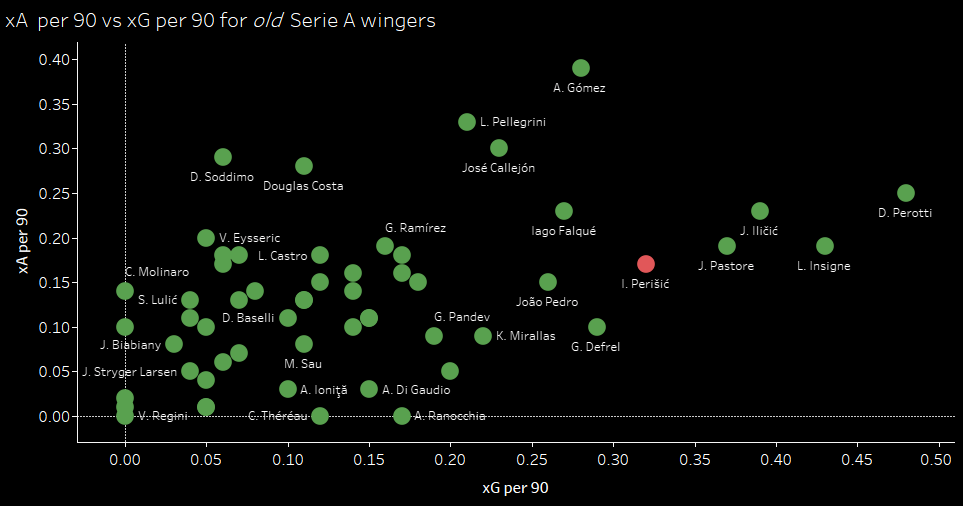

Let’s look at, closely, the 2019/20 window to see how Bayern got their players. We’ll start with the oldest player – Ivan Perišić – and his time in Serie A in 2018/19 season.

For old players, Perišić was putting up great numbers. Recording the fourth-highest xG aged 30 isn’t easy. This is especially the case seeing that he put these numbers up at a struggling Inter Milan who only recorded 57 goals.

However, there was something that Perišić offered that prompted Bayern to take him on loan.

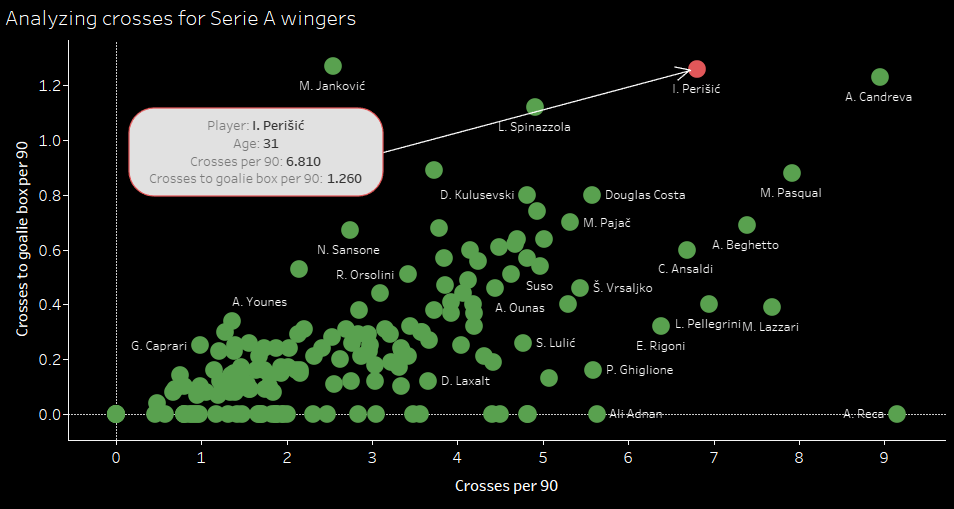

In 2018/19, Bayern lost Arjen Robben and Franck Ribéry. While Coman and Gnabry are talented wingers, Robben and Ribéry added a much needed direct goal threat that had made Bayern an attacking threat. One of Moneyball’s approaches is to recreate a great player either through individual or aggregated measures. With that in mind, let’s look at Perišić’s direct play.

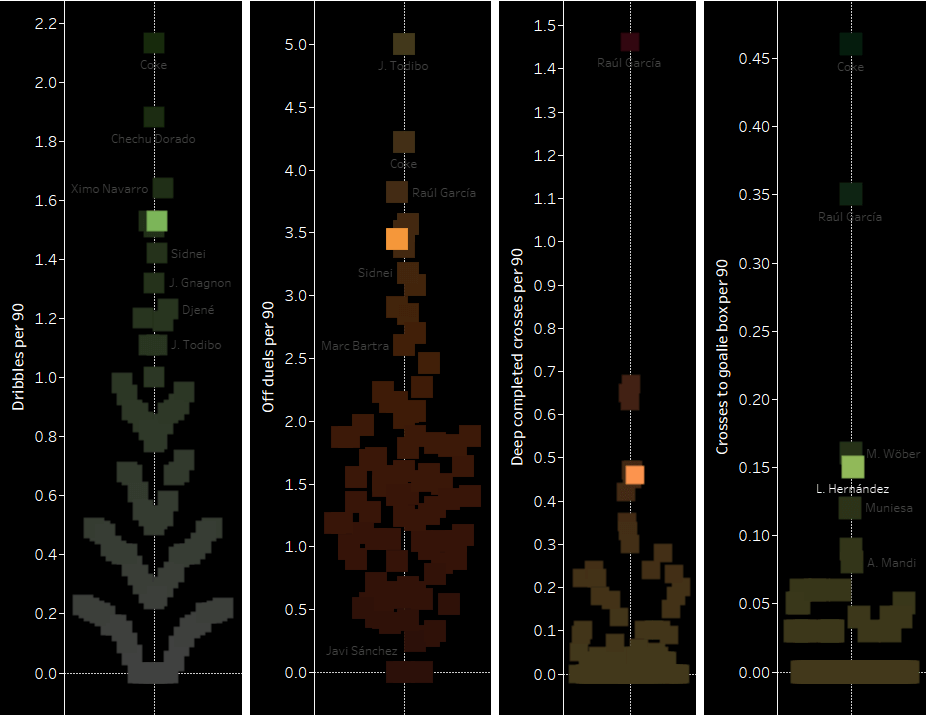

Perišić records a high number of crosses in the league and is tied second for crosses going to the goalie box per 90. In fact with these statistics, Perišić was one of Serie A’s most dangerous and direct wingers.

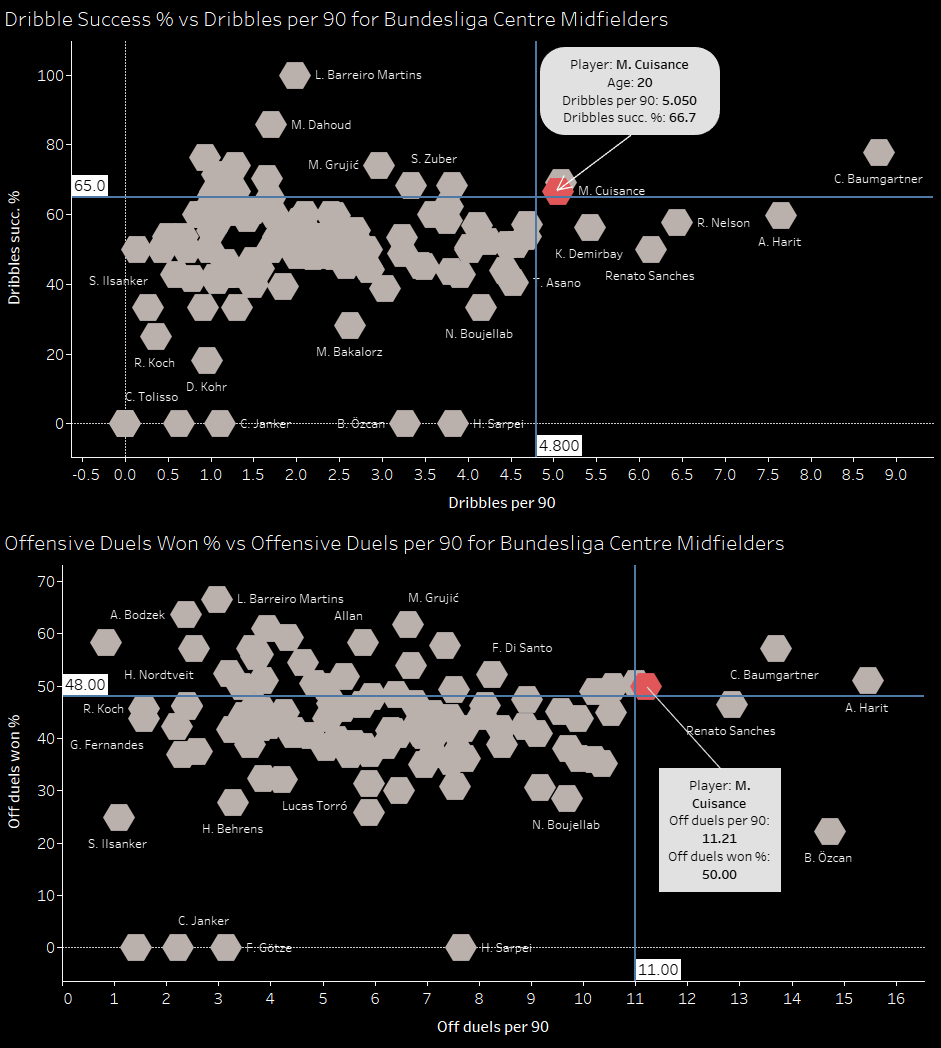

This theme of aggregation is also seen in the transfer of Mickaël Cuisance from Borussia Mönchengladbach.

Here Cuisance, in the 2018/19 Bundesliga season, ranked highly in the dribbling and offensive duels department at Mönchengladbach – rivalling the likes of Renato Sanches, Amine Harit, and Reiss Nelson, and Christoph Baumgartner. One can see why Bayern picked up Cuisance – his ability to dribble with the ball with the frequency and success rate allowed them to introduce a new aspect to their attack at a very low price.

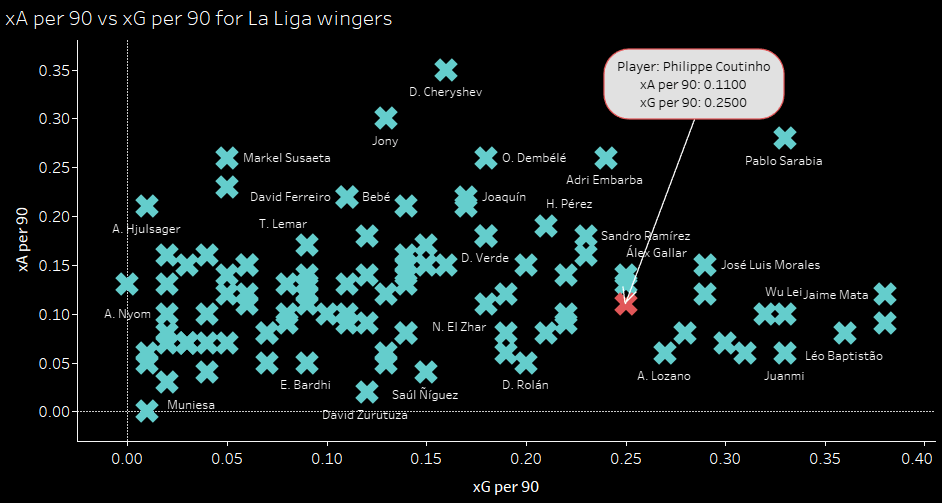

Phillipe Coutinho follows in the footsteps of Cuisance and Perišić where various clubs didn’t glance at them however they had value for those with a keen eye. Various clubs deemed that Coutinho did not live up to the price tag that Barcelona paid and the consensus was that Coutinho had been a “flop”. Looking where other clubs hadn’t, Bayern took him on loan. Taking a “flop” on a loan allowed them to get quality on a low price. If it didn’t work out, then Bayern would end up paying a small amount but if it did work out, Bayern would clinch quality at a bargain.

Looking at Coutinho’s metrics for La Liga wingers in the 2018/19 season, we see that Coutinho is recording a strong performance in xA and xG. Of course, these metrics don’t justify the hefty price tag paid by Barcelona but as Bayern rightly saw – there is a player there.

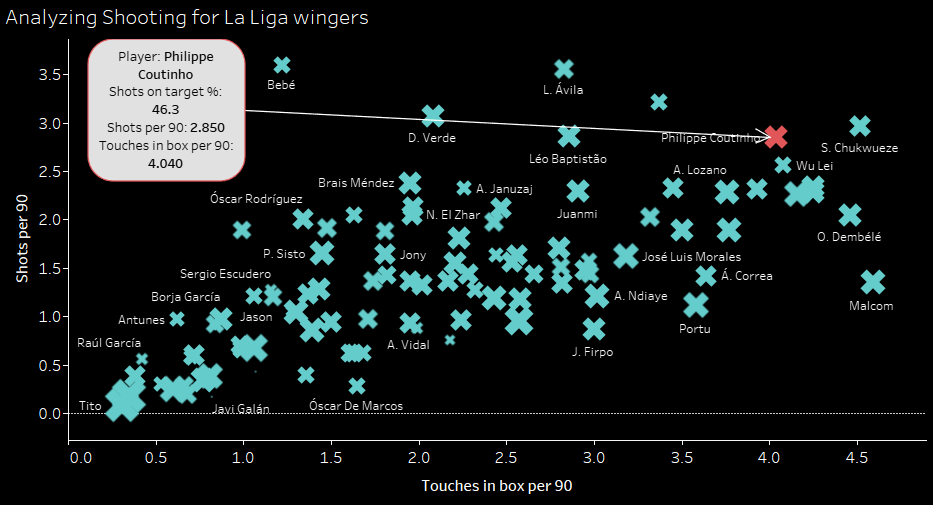

Looking at shooting within La Liga wingers, we see Coutinho’s best ability come about – goal-mouth action. Not only does he record a high number of touches, but he also shoots a lot. Clearly, Coutinho represented the mould of the attacker they were going for – young or about to go into their peak who added a different level of directness. Where Perišić looked to use his crossing and Cuisance looked to use his dribbling, Coutinho would use shooting.

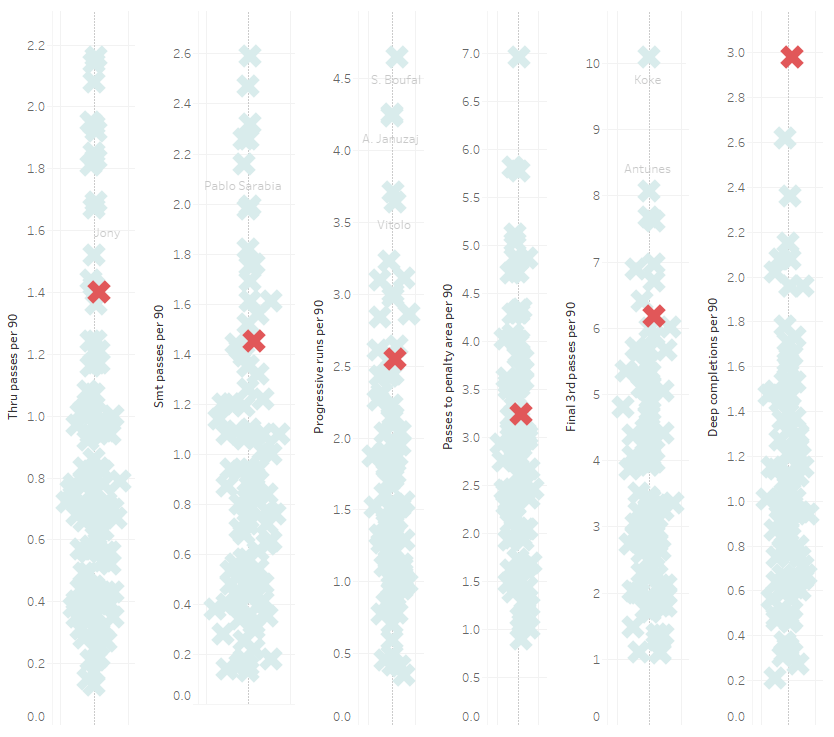

However, Coutinho’s shooting abilities were well known by most Liverpool fans and Barcelona fans. Was there something beneath the surface that the Bavarians could utilize? Analysing attacking metrics showcases a different viewing of Coutinho.

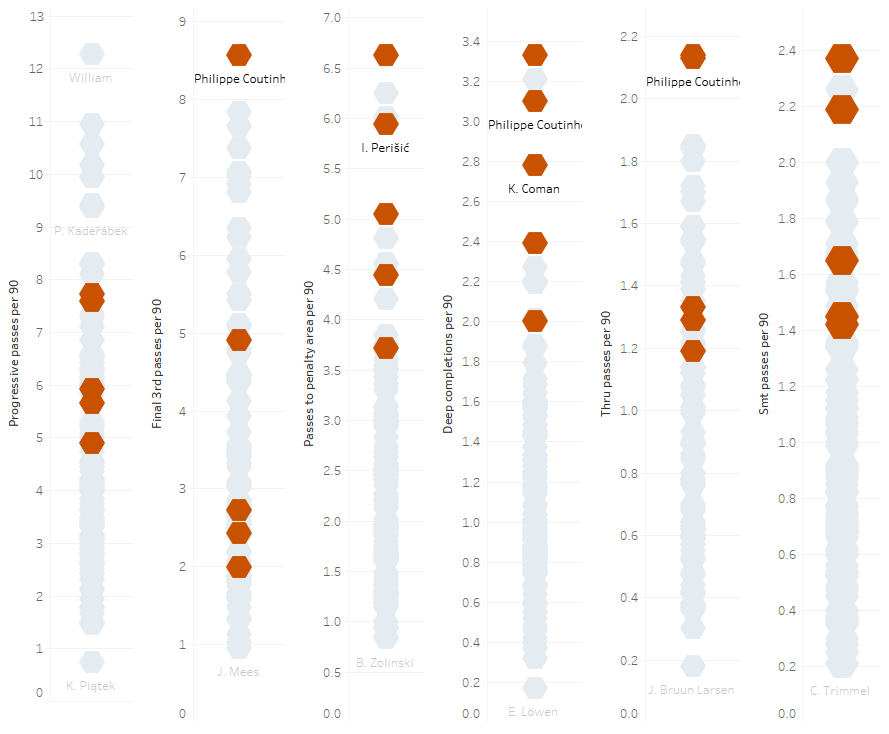

Here in various creative measures, Coutinho consistently ranks above average however the metric that he performs the best is in deep completions – putting his teammates 20 meters within the goal. In fact, he ranks first in this metric.

This showcases that while other parts of his game could be developed – seeing his performance in key metrics like final third passes and passes to penalty area – if Bayern played their cards right, they would be getting a player who ranked first in putting his teammates 20 meters within the goal – a valuable skill. This performance coupled with his performances at Liverpool prompted the Bavarians to get him on loan and, as we’ll see later, is paying off dividends for them.

After getting two wingers, the Bavarians went on and bought two full-backs: Benjamin Pavard from VfB Stuttgart and Lucas Hernandez from Atlético Madrid. Out of the two, Hernandez was supposed to be the marquee signing for Bayern. However, Davies’ exceptional performances and quality have ensured that Hernandez has not been able to get as many minutes as both play left-back. However, it still pays off to take a small glance at Hernandez and see why he was picked.

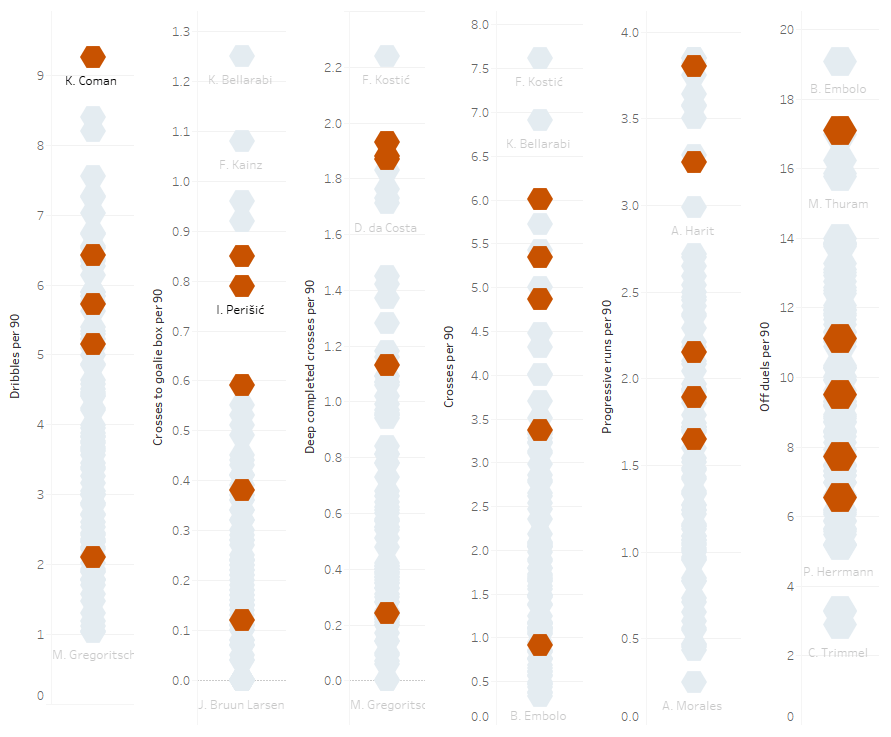

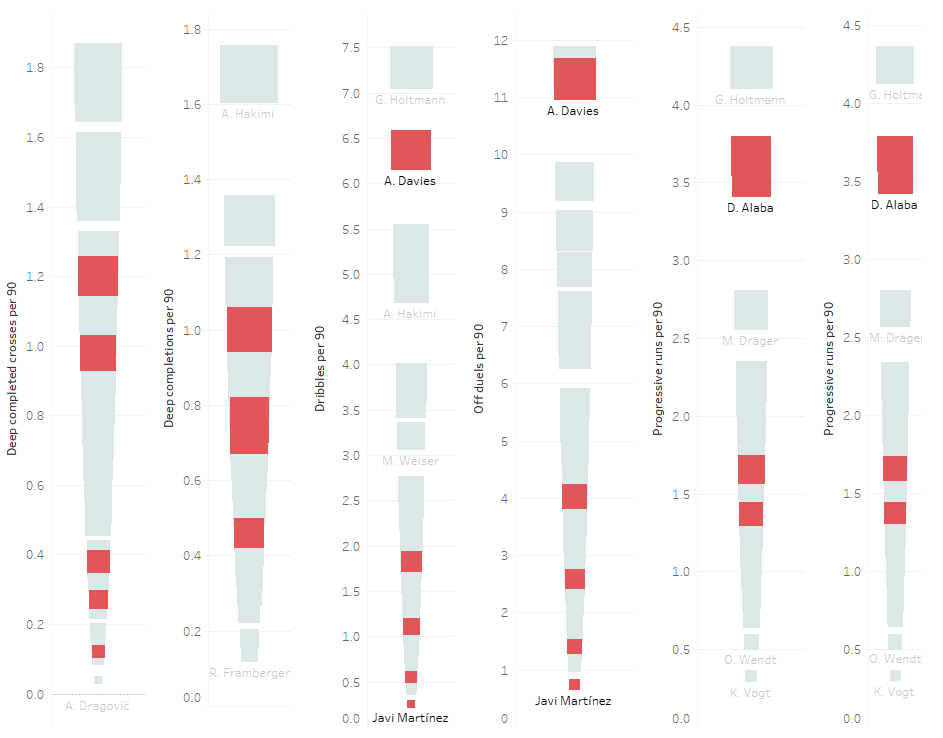

Here are Hernandez’s best performances in the various metrics that we have used to analyse other players. In the metrics of dribbling and offensive duels, Hernandez ranks very highly and shows his quality of getting forward without external help. This ability in full-backs is crucial as it frees up the wingers to get further forward as they know that they don’t have to drop deep.

Complementing this great dribbling ability, Hernandez shows expertise in crossing with ranking high in deep completed crosses and crosses to the goalie box per 90 – two areas that are important to Bayern as they allow them to attack the wings in an effective manner.

This performance coupled with Hernandez’s performances at Atletico Madrid prompted Bayern to make the big money signing that would elevate their full-back play to another level.

Bayern’s Payoff

We’ve seen the strategy and the angle at which Bayern worked on their transfers. Obviously, the Bavarians have come away with the win but the key question is: how integral were these transfers to their victory?

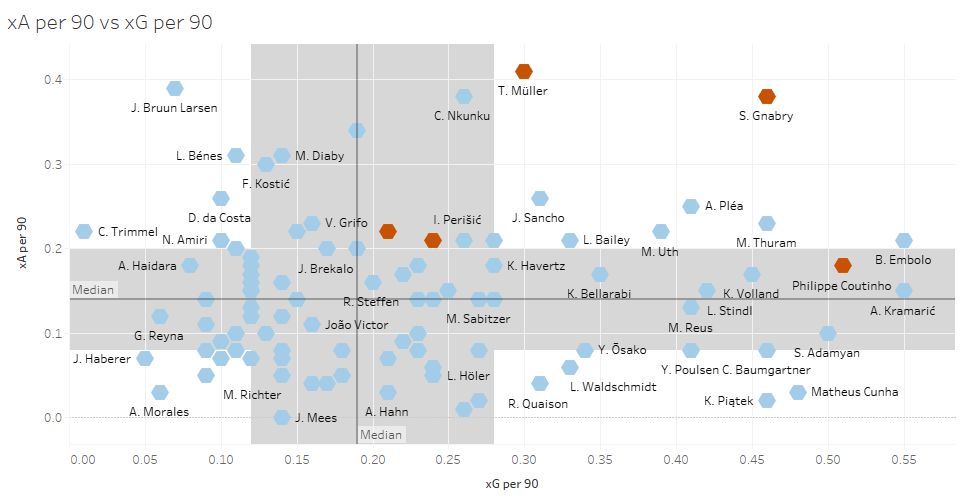

Let’s start with an exploratory analysis of xA and xG. Coutinho shows himself a man of change who went from a player recording a mixture of xG and xA to a player who ranks third in xG per 90 among wingers and attacking midfielders.

Up ahead of Coutinho lies Gnabry who shows himself to be one of the most dangerous wingers in the league with an xG of near 0.45 per 90 and an xA per 90 of near 0.40. Perišić shows his quality from Serie A in recording above-average xG while Coman functions as a creative winger – recording above-average xA per 90. As it currently stands, Gnabry is the second-best winger in terms of goal and assist productivity

All in all, looking at xG and xA per 90, Gnabry records a metric of 0.93, Coutinho a metric of 0.74, Coman a metric of 0.48 and Perišić a metric of 0.47. All four transfers are each contributing one goal or assist every two games at the very least. Those numbers are frightening for any defence and in fact for any team facing the Bavarians.

As seen with this display of attacking metrics, Bayern’s hard work seems to have paid off. Highlighted in brown are Munich’s attacking players: Coman, Coutinho, Perišić, Gnabry, and Müller. Coutinho – who showed little outlook in LaLiga – shows himself topping the charts of almost every metric save for some. Near Coutinho are normally Müller and Coman providing Bayern with more creativity and a different kind of attacking force – Müller functioning as an attacking midfielder and Coman functioning as a creative winger.

What is amazing to see here is that all of Munich’s attacking midfielders – apart from

Müller – are transfers and they are leading the metrics in just about every way. This is a testament to Munich’s smart recruitment.

In measures of directness, Coman and Perišić lead the line with Gnabry and Coutinho following suit. As expected, Perišić is leading the crossing metrics whereas Coman and Gnabry dominate metrics like dribbling and offensive duels – aggregating the dribbling they lost in Ribéry and Robben.

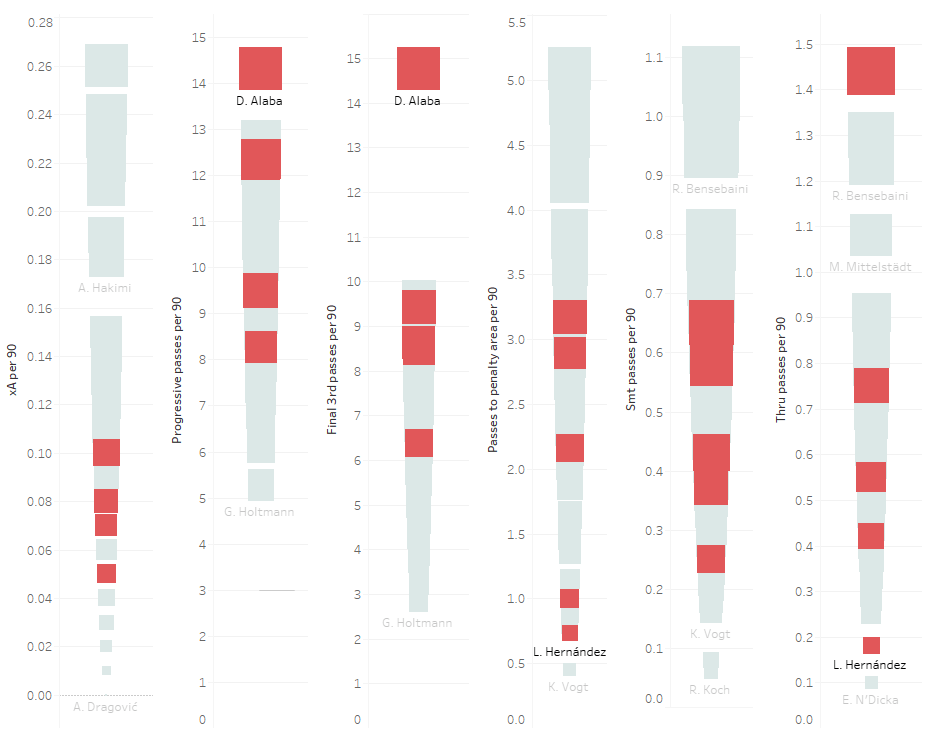

The same positive performance that we saw in the attack is occurring in the defensive area for Bayern with David Alaba and Davies leading the way in major attacking areas. Hernandez, in these metrics, ranks near the bottom due to the minutes he’s gotten this season but were Davies to get injured, Bayern Munich would have a full-back in Hernandez ready for taking up his role adequately.

Right-back Pavard comes in these metrics but comes after Alaba and Davies and isn’t that spectacular in the attack. However seeing that Pavard’s use at the team differs, leaning towards the defence, it makes sense for him to perform less spectacularly.

As we saw in our attacking performances, Bayern’s transfer dealings lead the way in the measures of directness as we see with Davies. Bayern dominate through Davies, primarily, and Alaba in metrics like crossing and dribbling which tactically gives Flick various options as he knows that he has a defence that can attack their own and can put in dangerous balls into an already dangerous arsenal of attack.

Conclusion

As we have seen in this exhaustive analysis, Bayern Munich’s transfer revolution is well underway. Bayern have already gone off and signed two more players – Nübel and Kouassi – who both adhere to the guidelines shown in this data analysis.

In a span of years, the Bavarians have built a squad that is really coming to its own and with one or two fine tweaks, Munich will have created a squad that will go toe to toe in the biggest stages of them all to bring home the trophy they ever so long for.

Comments