The pick of this weekend’s Bundesliga fixtures comes in the form of an interesting stylistic matchup, with Borussia Monchengladbach taking on Bayer Leverkusen at an empty Borussia Park. Both sides picked up where they left off following the break, with both sides registering sizable wins over Frankfurt and Werder Bremen respectively. The fixture is a key one in the Bundesliga’s Champions League race, with the sides separated by just two points in third and fifth place. The match is also an excellent stylistic match up, with Peter Bosz’s possession style system now coming up against Marco Rose’s high-intensity vertical football. In this tactical analysis, I will look to preview the tactics both teams have used throughout the season, what tactics they may use in this game, and how both teams may interact with each other throughout the game.

Leverkusen’s 2-4-4 and other build-up structures

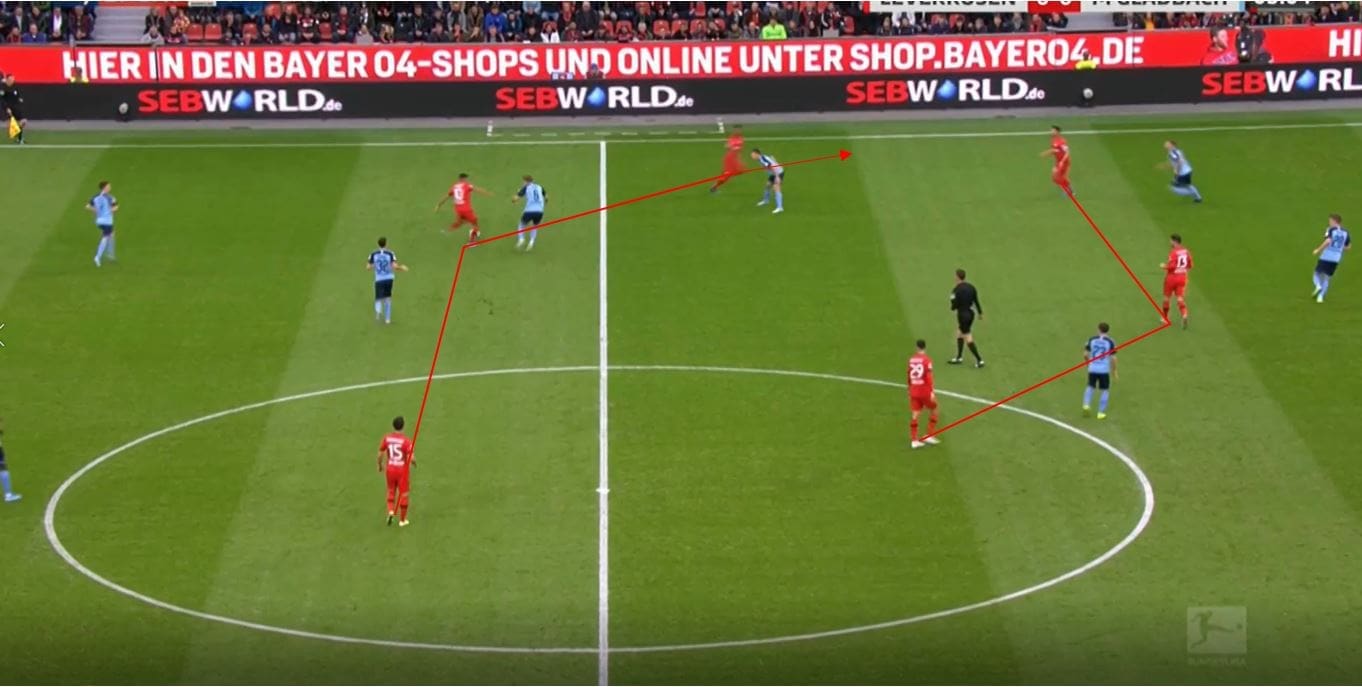

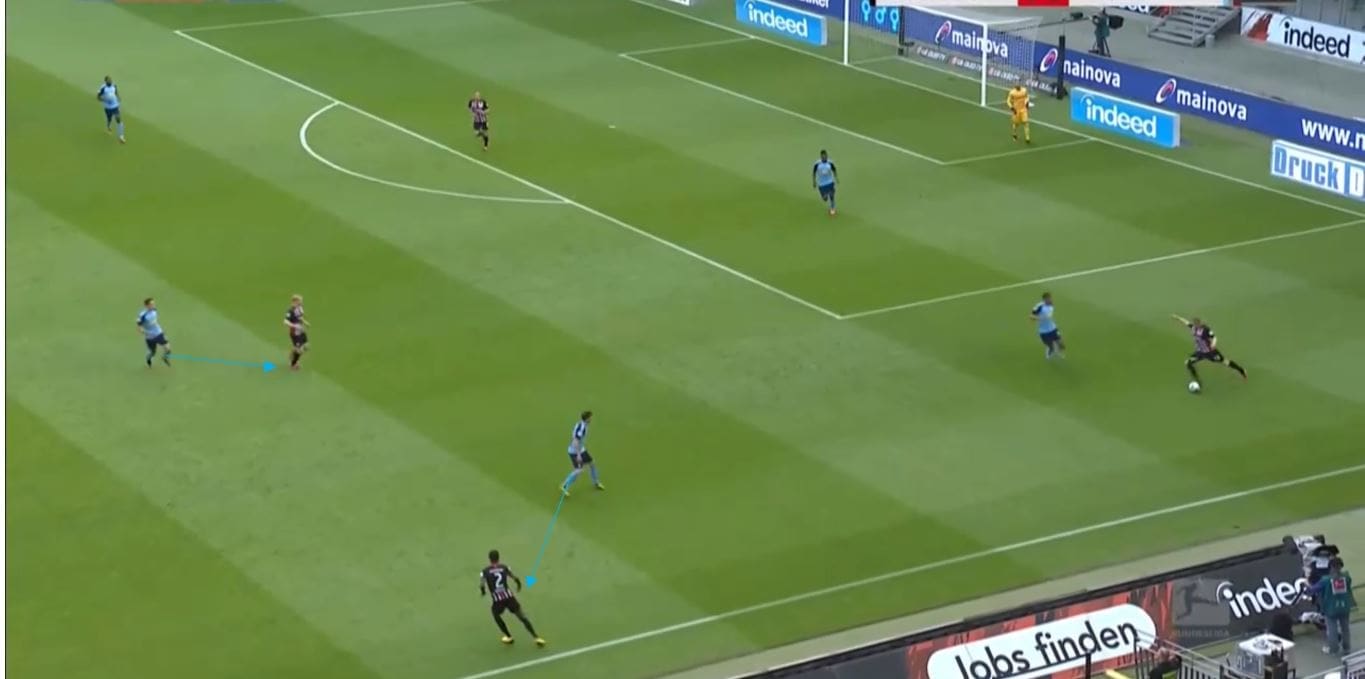

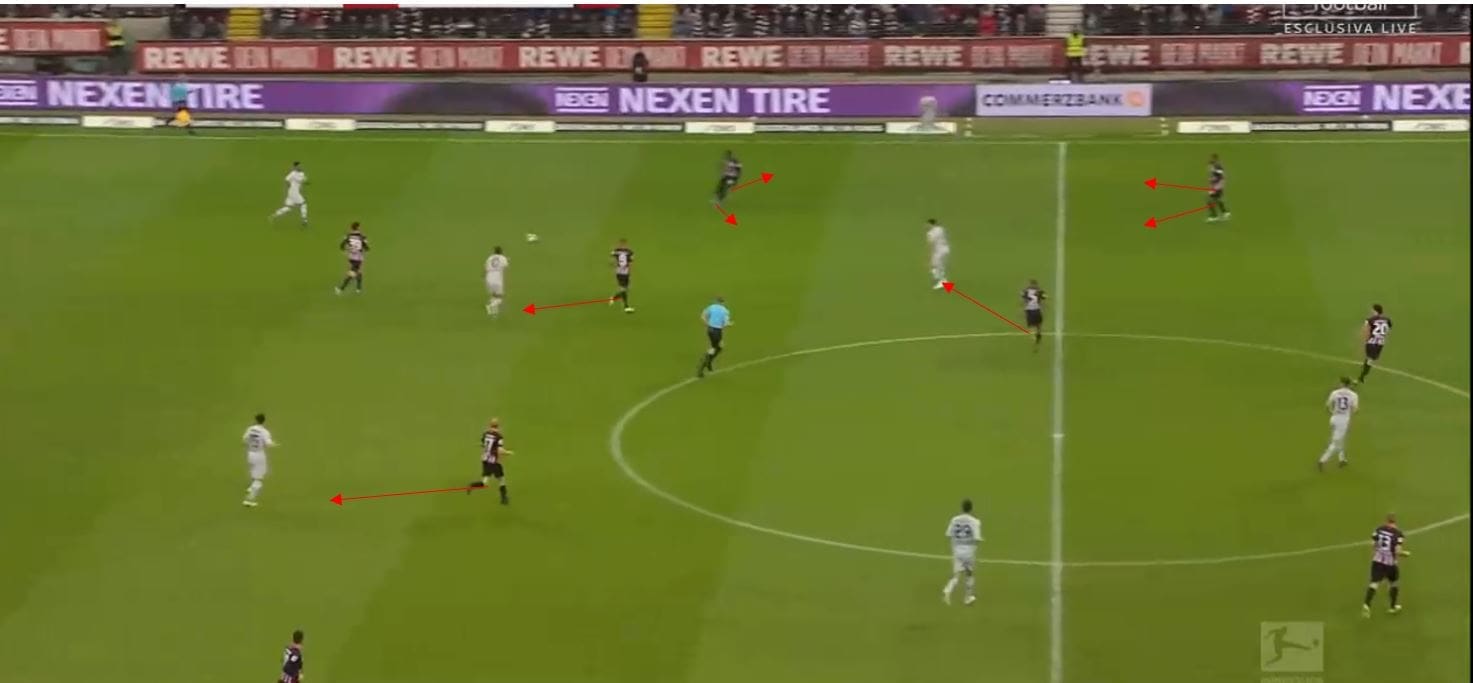

Although on paper Bosz’s side usually lines up in a 4-2-3-1 or 4-4-2, in reality, Leverkusen’s shape usually becomes a 2-4-4, with the full-backs pushing higher while the central midfielders remain slightly deeper. The aim of this structure is to allow fluid movement with many players occupying the opposition back line, with Leverkusen usually prioritising the use of the half-space, with Kai Havertz often occupying Leverkusen’s right half-space. We can see in this image below, the full-backs provide width to stretch the second line, allowing access to the final line. In the first meeting, Gladbach played a back five, and similarly to Schalke last weekend, relied on one of their centre backs to step out to retrieve the ball and mark the player in the half-space. Solving this half-space problem is something I will discuss later in the article. Jonas Hoffman also seemed to man-mark Kai Havertz for the majority of the game.

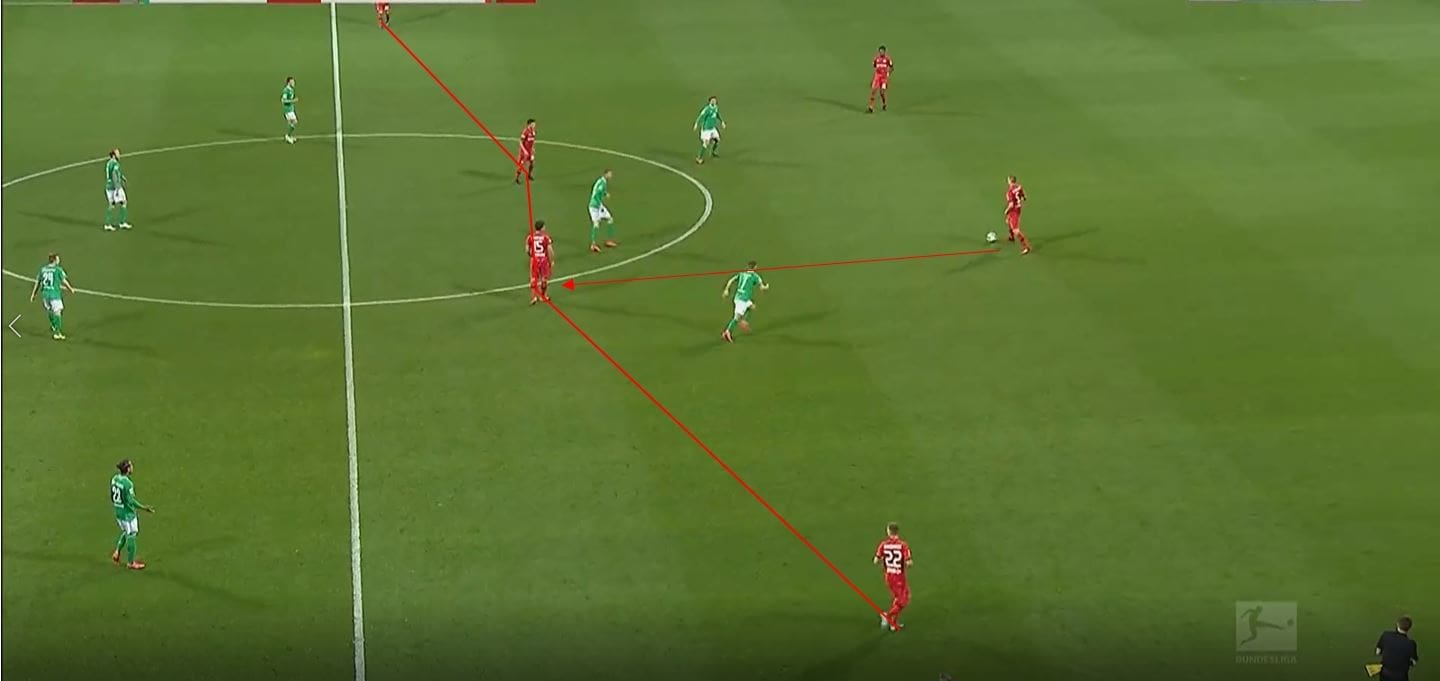

We can see an example of this structure being used again below, in their most recent game against Bremen. The central midfielders remain deep and central, causing a dilemma for the man markers behind them, as if they push higher they risk space both behind them and to the sides in the half-space. As a result, when they don’t press, the midfielders have time and space between the lines. Where they are then able to progress play.

Leverkusen can then access the third line, which is spaced accordingly again. Notice the extreme width on the right side, which would typically increase the size of the half-space should the attack be in a wide area. Here they don’t need to use it with the attack in a central area, and instead play wide and eventually inwards through a dribble by the high right winger.

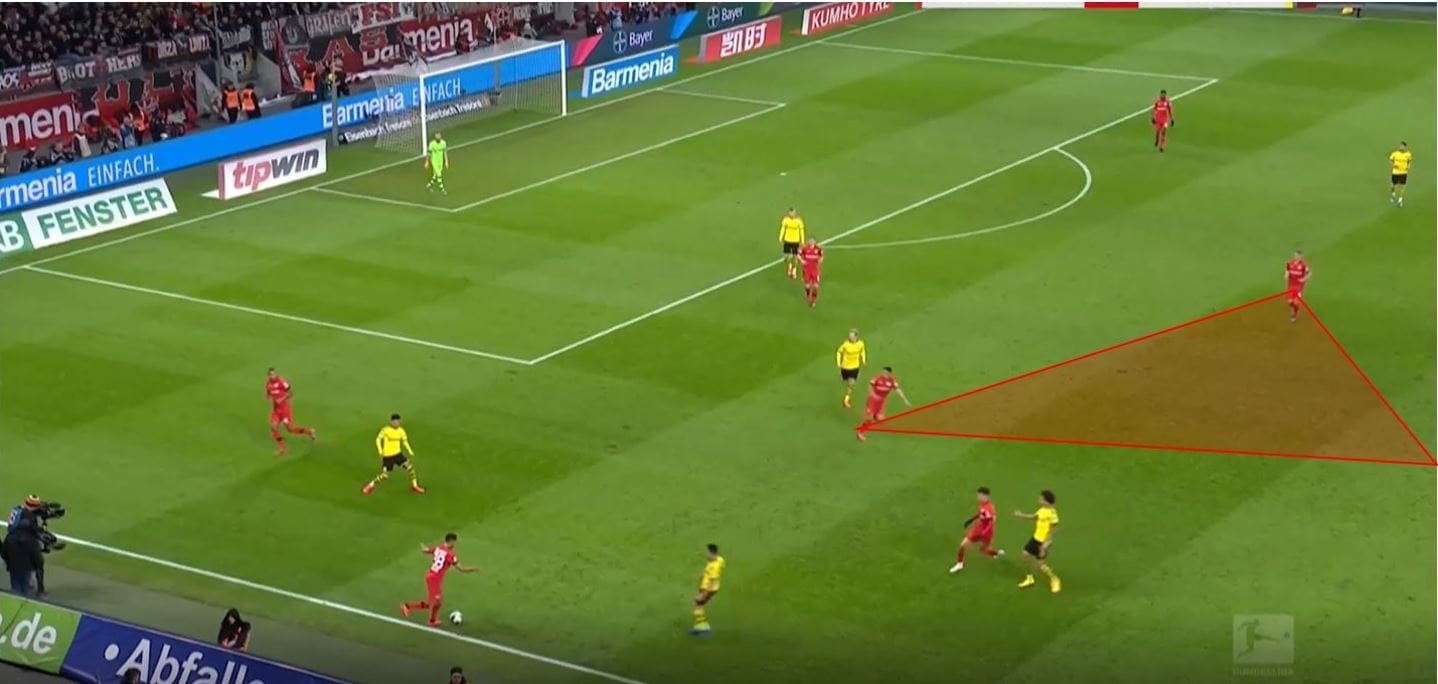

Leverkusen have also used a back three often this season, and have interestingly done it against high pressing sides away from home such as Dortmund and Leipzig, who also used back threes. The advantage to a back three is obvious and well discussed on the site, and we can see it again here. The back three aims to stretch the first line of the press and force the second line to engage, with width also provided in order to increase the size of the half-space. Here we see Sancho is forced to press Leverkusen’s wide centre back, and as a result Havertz is able to receive.

In deep build-up play, Leverkusen were able to overload Dortmund’s central midfielders while using a back three, with Havertz dropping deeper in order to aid build-up and occupy a central midfielder, leaving two other central midfielders to face one of Dortmund’s central midfielders. This habit by Havertz on occasion may have an effect on how Gladbach look to press Leverkusen.

How can Gladbach press

Gladbach have averaged 9.52 PPDA this season and are generally a team who look to press high in order to create opportunities. In their most recent game against Frankfurt, their press was less intense but was still relatively high when needed, particularly early on. We can see in a deeper area the shape Gladbach looked to press in, with a 4-2-3-1 used which often became a 4-3-3, with the attacking midfielder and winger moving up to press the far centre back and full-back.

The two central midfielders were fairly man orientated and followed their counterparts into deeper areas, while the wingers were able to cover the full-backs usually. This is a scheme Gladbach have used fairly often in their 4-2-3-1, but Gladbach are extremely tactically flexible and are therefore difficult to prepare for.

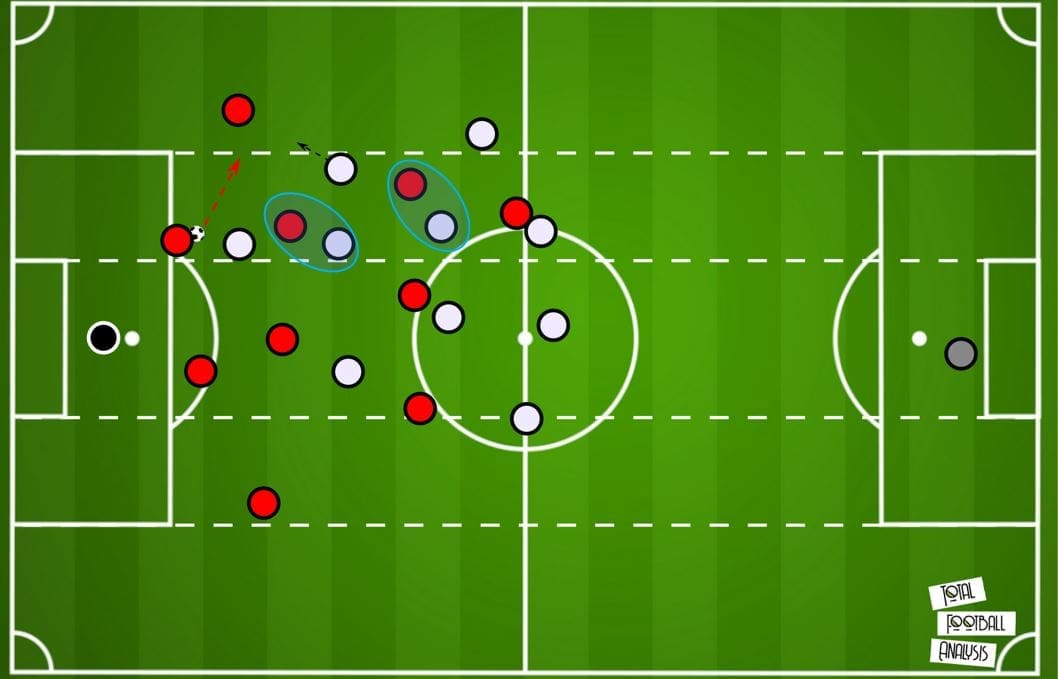

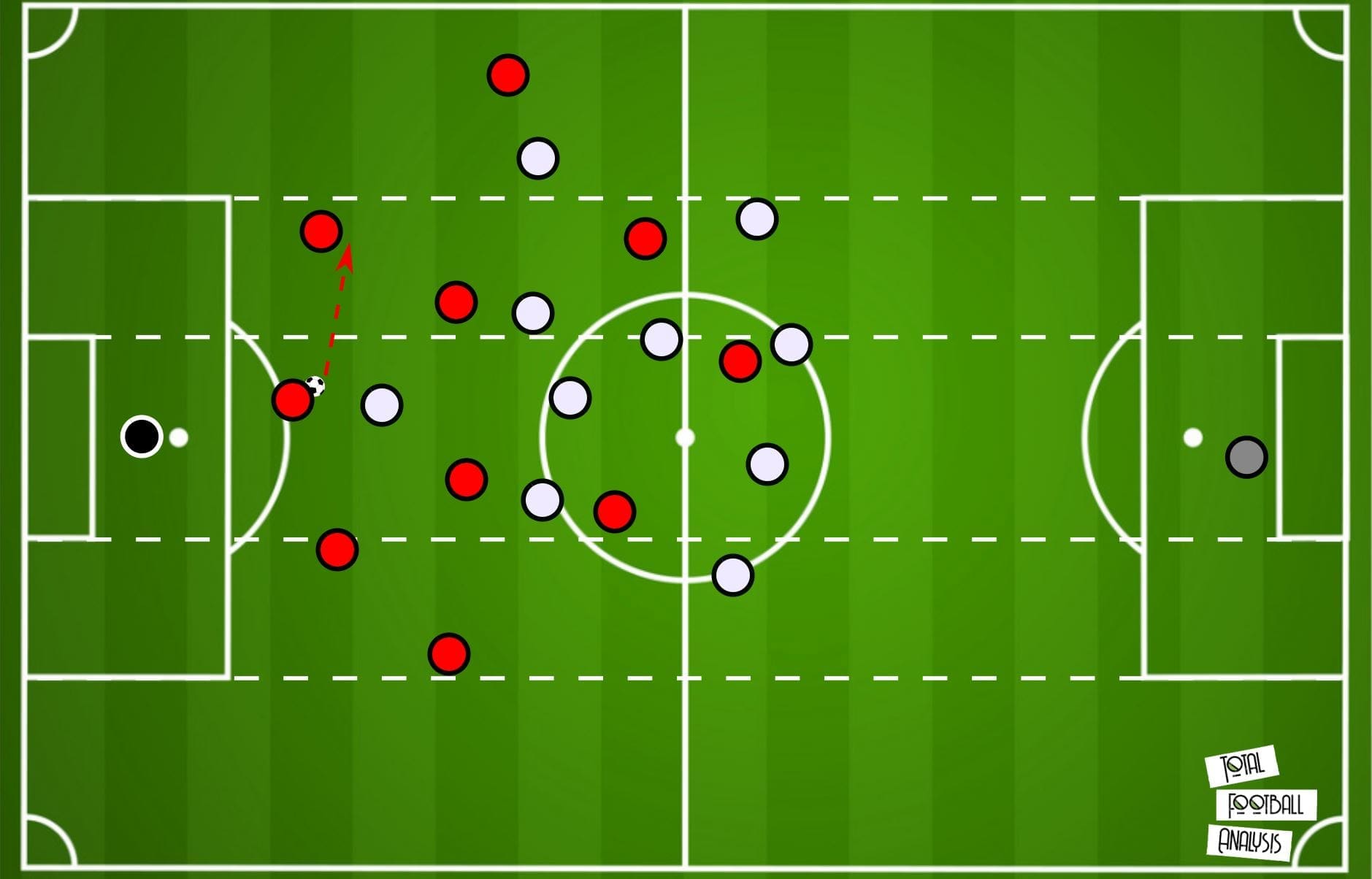

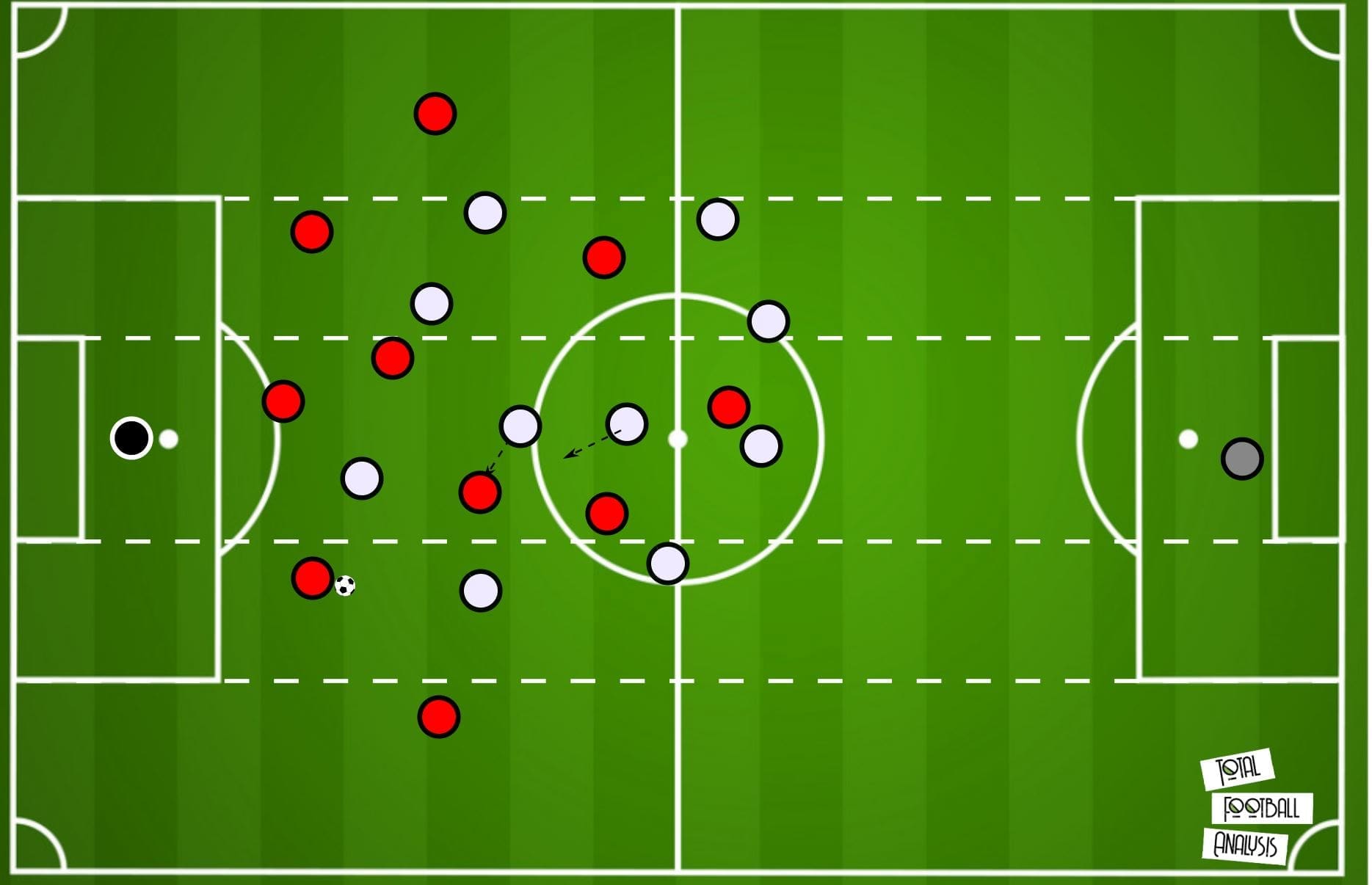

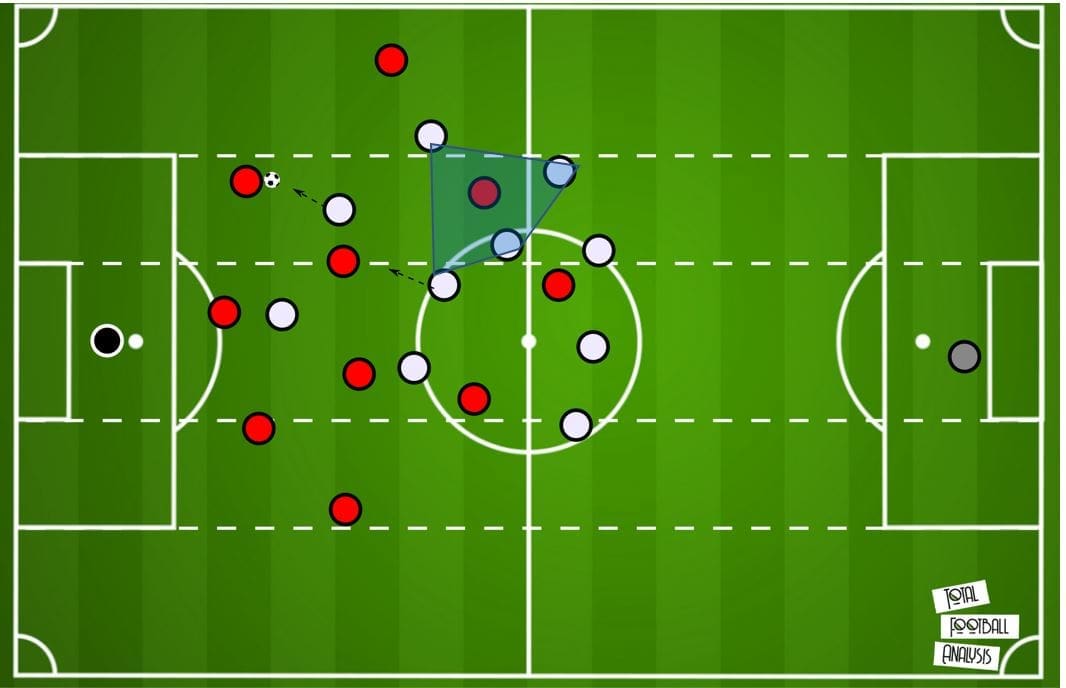

So how would this 4-2-3-1 press interact with Leverkusen’s build-up play? We can see a potential scene below, in which Leverkusen build up in their deep back four and two deep central midfielders, while Gladbach press in that 4-2-3-1. The winger is able to press the full-back, while the nearest central midfielder is able to be pressed by the ten (attacking midfielder). The player occupying the half-space area can be covered by one of the deeper central midfielders, while if they move into a wider area, they can be passed onto the full-back and this midfielder can continue to protect the centre.

The problem comes in a switch of play, and the opposite winger’s ability to press the centre back. If the ball switches from the situation above to the one below with the left centre back switching to the right, the winger has to move across to attempt to cut the lane to the full-back, which could be difficult. Furthermore, the ten has to move from one central midfielder to the other, and there is certainly an opportunity to find the full-back with two passes, and therefore in order to press this player the full-back would have to be committed over a long distance, which in turn reduces coverage in the backline.

When pressing we must also consider the offensive ability the pressing structure has, and in this structure, the offensive opportunities fit naturally into the principles of the side. The striker is not a particularly active presser, only able to press one centre back at a time, and as result can stay forward and provide height in the team’s structure, helping to give passing options around vertical passes.

The structure allows for players to stay ahead of the ball and prepare to receive passes immediately, with diagonal options available in central areas, which gives multiple passing options. This is, of course, theoretical, but nevertheless this pressing structure would allow and has allowed for quick counter-attacks for Gladbach.

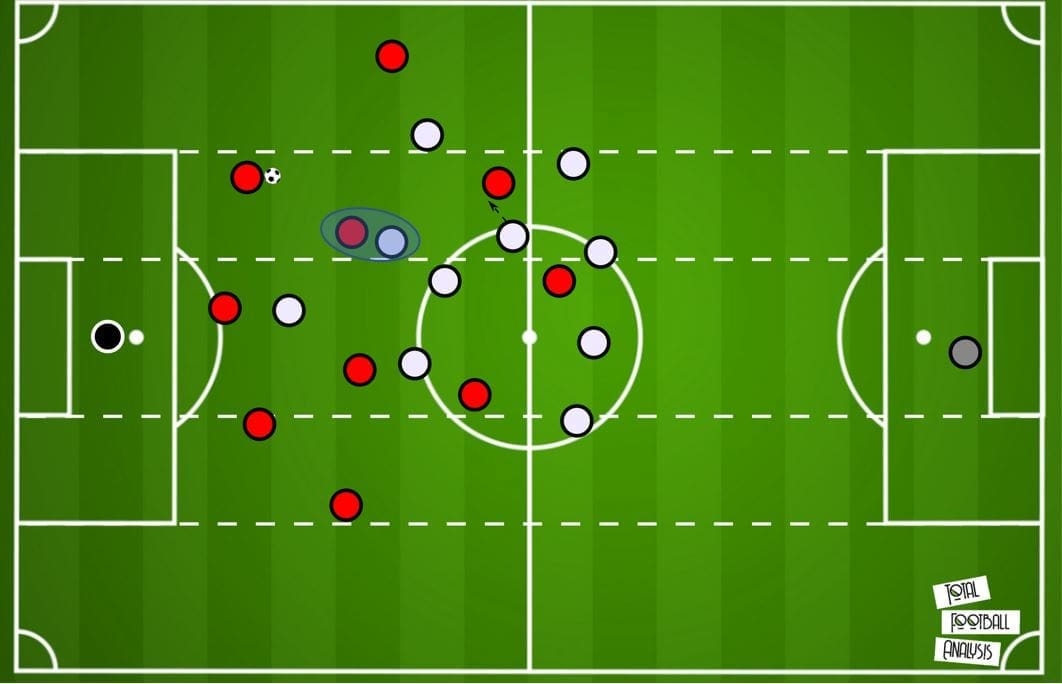

If Leverkusen were to line up in a back three, the 4-2-3-1 would become much more stretched with the coverage issues seen in the previous example. As a result, we can take some examples from other Bundesliga sides, namely Frankfurt, in order to find a solution to Leverkusen’s build-up should they enter into a back three. Frankfurt in their 3-0 win over Leverkusen pressed in a 3-1-4-2 structure which varied significantly, but had a good impact on Leverkusen’s build-up. We can see the responsibilities of players below, with two central midfielders marking their opposite central midfielders, while a defensive midfielder sat behind the second line and looked to occupy any higher Leverkusen players. This allowed Frankfurt to cut the access to the wide areas well, and force this kind of pass in which Frankfurt have enough local compactness to deal with the threat.

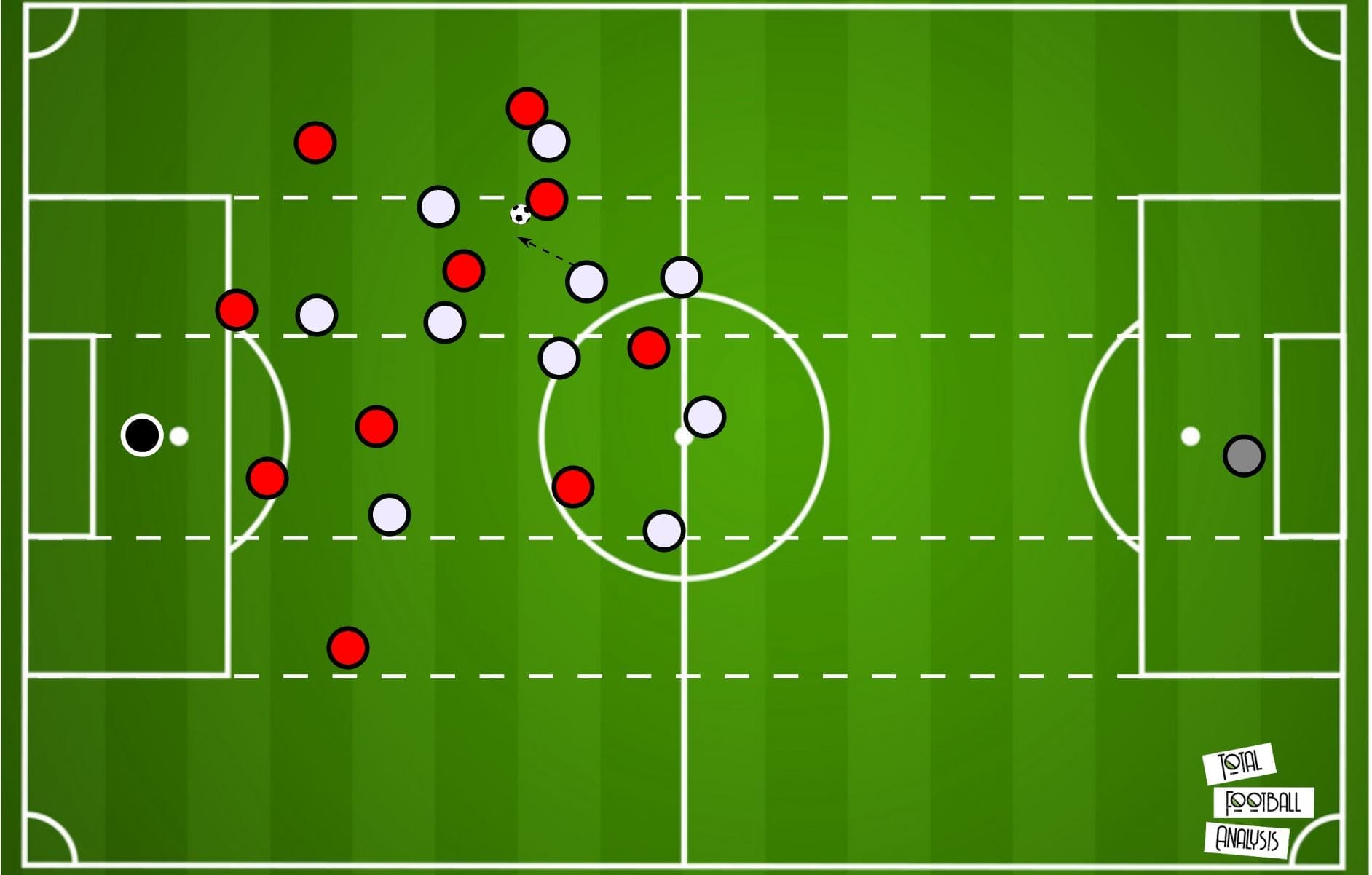

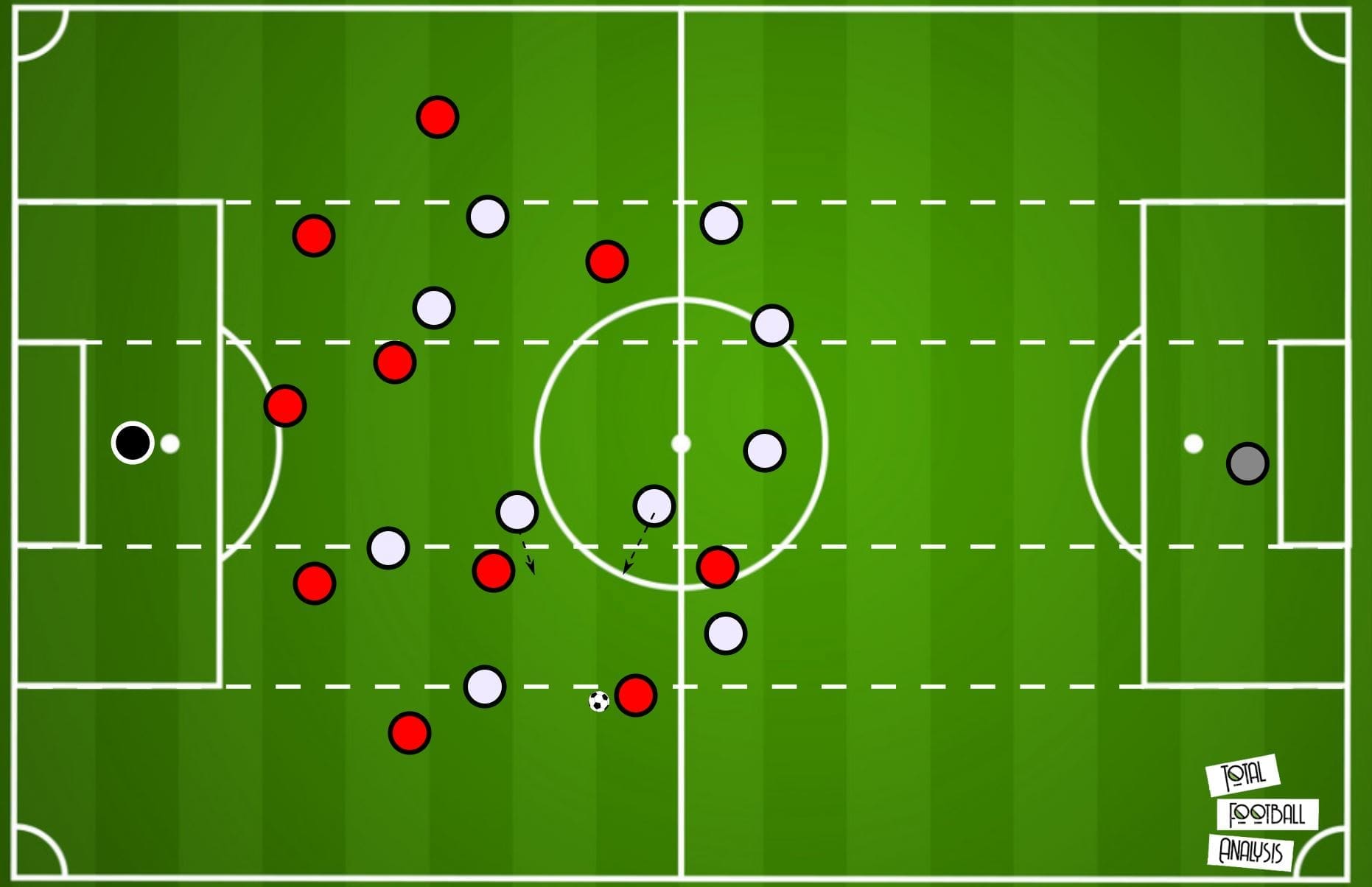

The dynamics are similar to this 4-1-4-1 which we can see below, which again is flexible but provides coverage and depth which allows for fluidity and better coverage during pressing, and also fits in with potential build-up strategies. We can see the initial scheme below, with one striker pressing the central defender and forcing the ball wide.

When the ball is laid to a wider centre back, options around them can be cut off easily, with the half-space covered by the defensive midfielder, the central midfielders man-marked, and the wide areas covered well. Alternatively, the defensive midfielder could be part of a back five, and could, therefore, step up similar to how we have seen in this analysis, but for me personally this reduces the height of the pressing available, as players then have to make further jumps in order to cover each other.

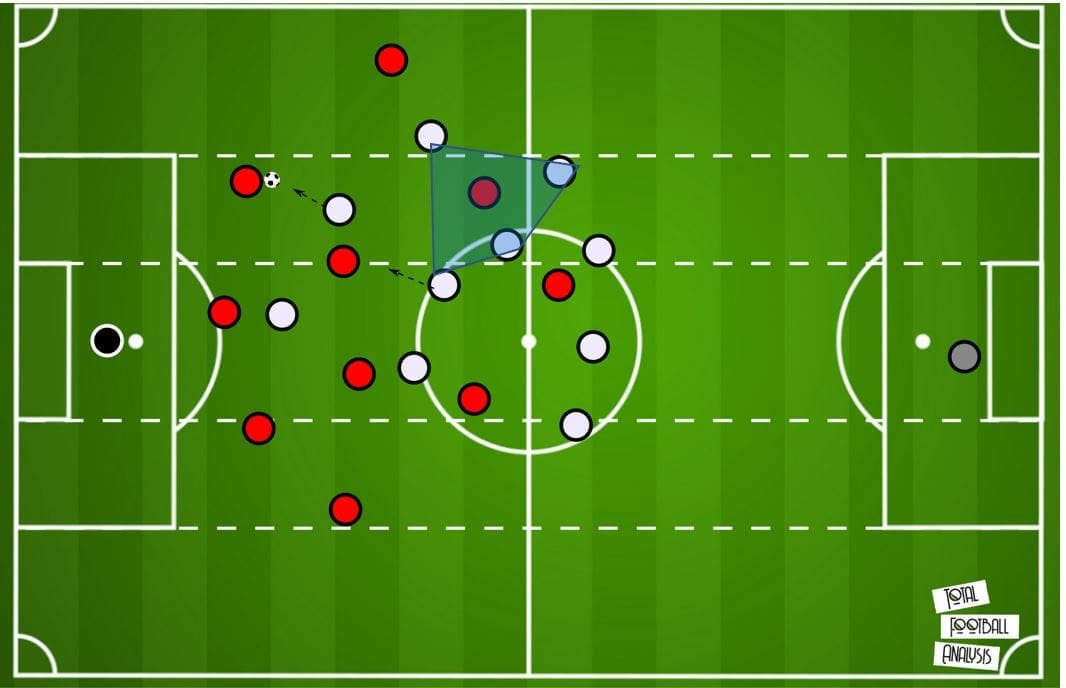

A simple jump which could be used would be for one of the midfielders to jump to press the wide centre back, with the far sided midfielder then covering the player he was marking. We can see then that ball near options are covered, and the half-space is able to be crowded well due to the use of that defensive midfielder. As a result, the formation could at times become a 4-4-1-1, or even a 4-2-3-1, which allows Gladbach to fit there attacking talent into the team still.

If the ball is switched, the midfield shape allows for more coverage and therefore for the team to shuffle across more effectively without creating gaps. The far winger can move to press, while the central can move across to the winger’s marker, and so on.

Furthermore, if the ball is progressed into a wide area, the shape of the team with the defensive midfielder allows for better coverage of the inside and benefits the teams ability to collapse around the ball and surround it in a trap, something Which Gladbach’s assistant manager has himself written about. With increased depth provided by this player, more passing lanes can be covered inside and so wide areas can be used to constrict the opponents space and win the ball.

Gladbach’s vertical football

If Gladbach are able to win the ball back, they will usually look to play quick, vertical football and get the ball forward. This often involves the use of up, back, through combinations and the principle of playing to the furthest player.

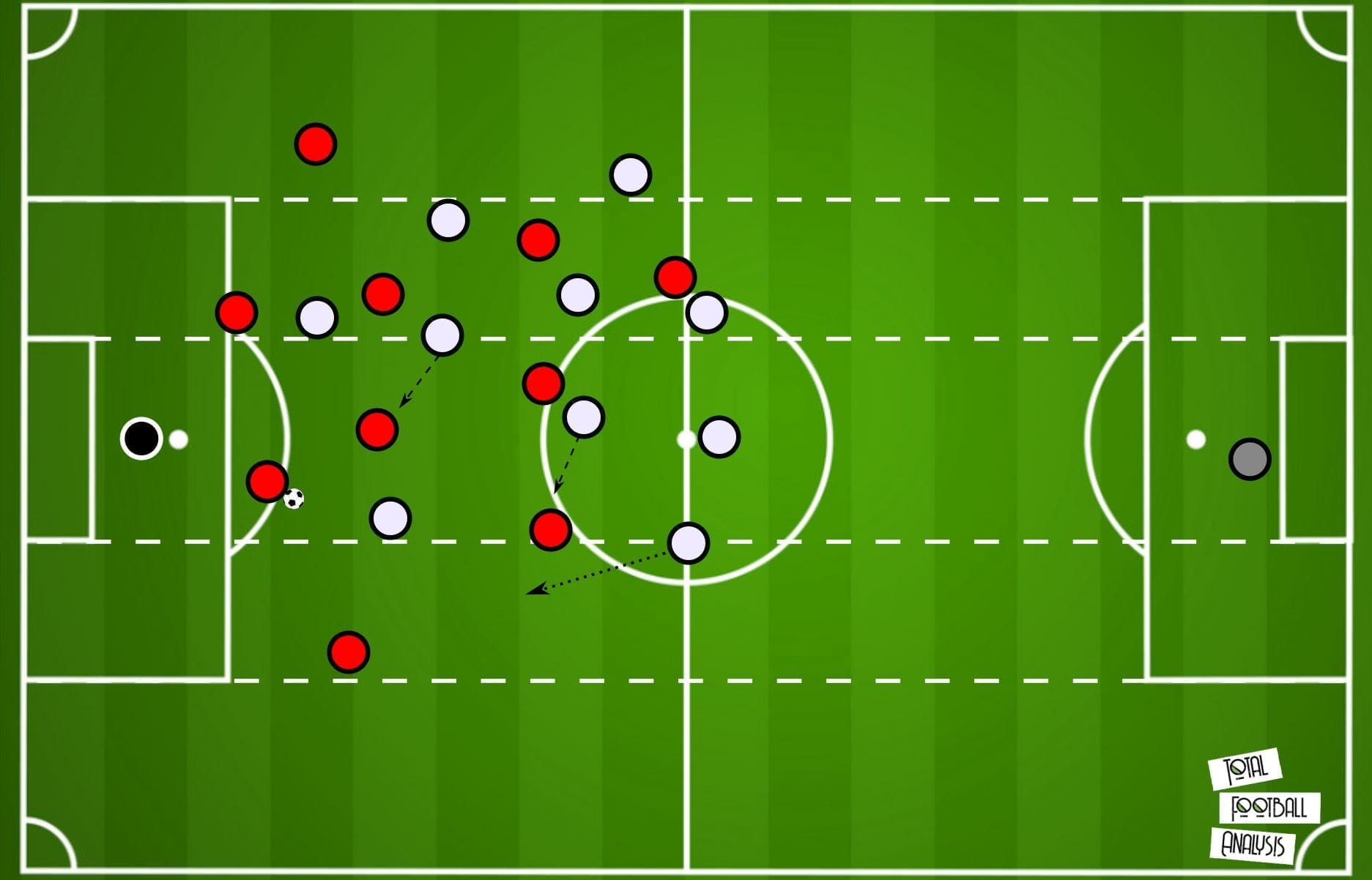

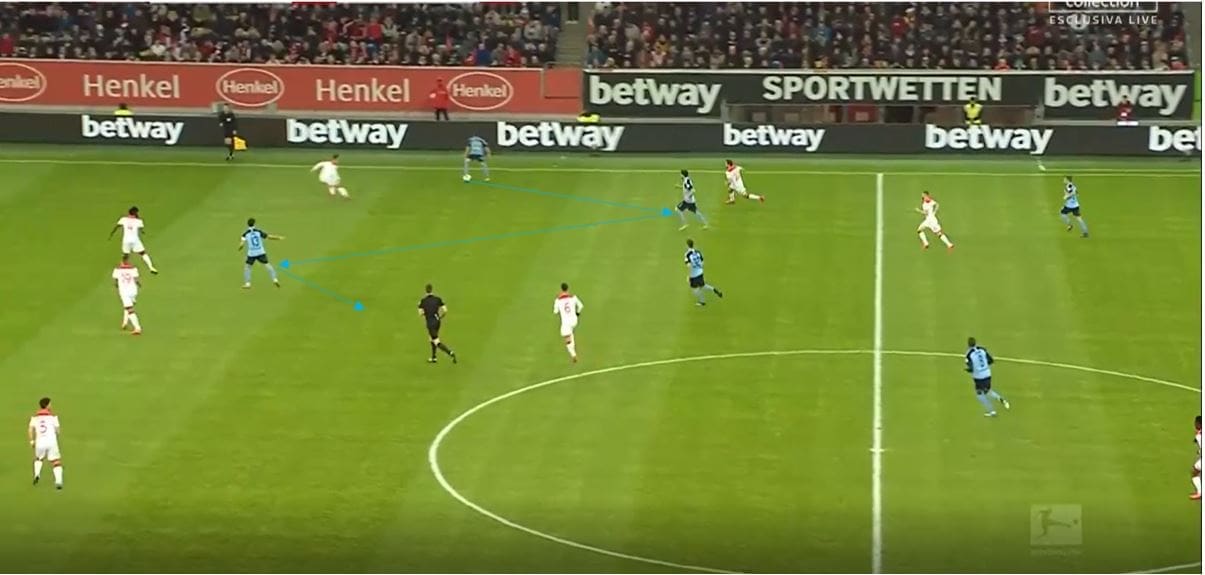

To supplement this, Gladbach constantly provide support around the ball, both horizontally and vertically in order to play short, quick passes to progress play and utilise space quickly. We can see an example of this here in their game against Fortuna Düsseldorf, where they provide vertical and horizontal support. The ball is played wide and support from behind is offered, while Lars Stindl gives height to the attack. Stindl is supported from behind by Florian Neuhaus, who is available for the ball to be laid off to.

From there Neuhaus can play the ball through to Marcus Thuram, who is also providing height for the attack. This is an excellent example of an up, back, through type combination which is extremely common in vertical football. It also shows the advantage of vertical football, which we can see in the next example too.

We can see here Gladbach playing the ball to the furthest man. Playing the ball to the furthest man allows for the ball to be progressed high up the pitch quickly, and if support is provided, allows for the next receiver to have excellent body orientation, in that they are facing the opposition goal and already running at speed. These kinds of passes can also allow for players to be brought into play on the second pass, as they may have been covered by an opponent in the first pass, similarly to the third man run concept. Also, while the ball is travelling to the furthest player, players can move up into supporting positions.

In this example below, we see the furthest man being passed to and then support through the middle being provided. The ball is played into the middle, and Neuhaus has excellent body orientation to progress the ball, and Embolo passes and then continues moving forwards, while Thuram also provides support up the pitch with a forward run. Players have to move quickly, intelligently and at the right times in order to create and utilise space and progress up the pitch. Focusing on the centre of the pitch also allows for more passing options to play to as opposed to wide areas, and there is less distance in order to get close to goal to get a shot off.

It is worth noting also that Gladbach do employ several build-up structures in order to create lanes and opportunities for such passes, and they demonstrated these well in their game against Frankfurt last week. You can find such structures in the analysis linked here by Niklas Hemmer, which explains well Gladbach’s flexible structure involving Tobias Strobl, who could also have the same impact as a defensive midfielder in this game, helping to overcome Leverkusen’s equally intense press.

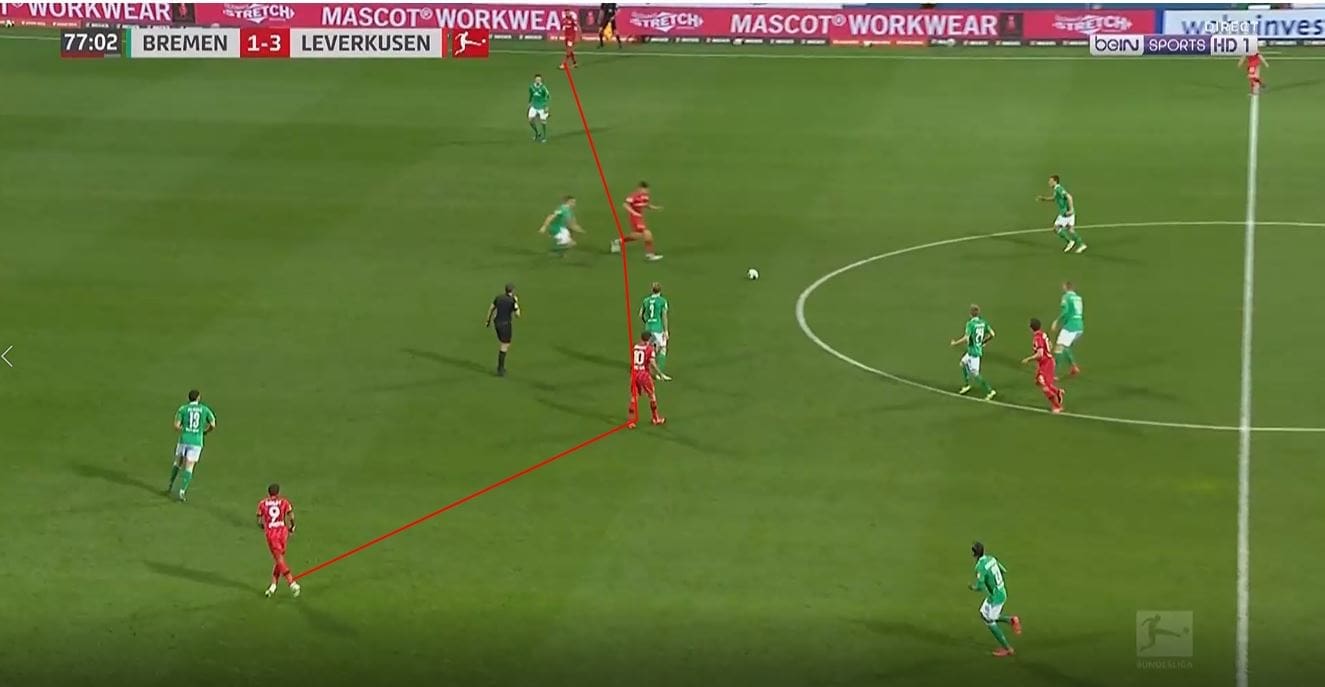

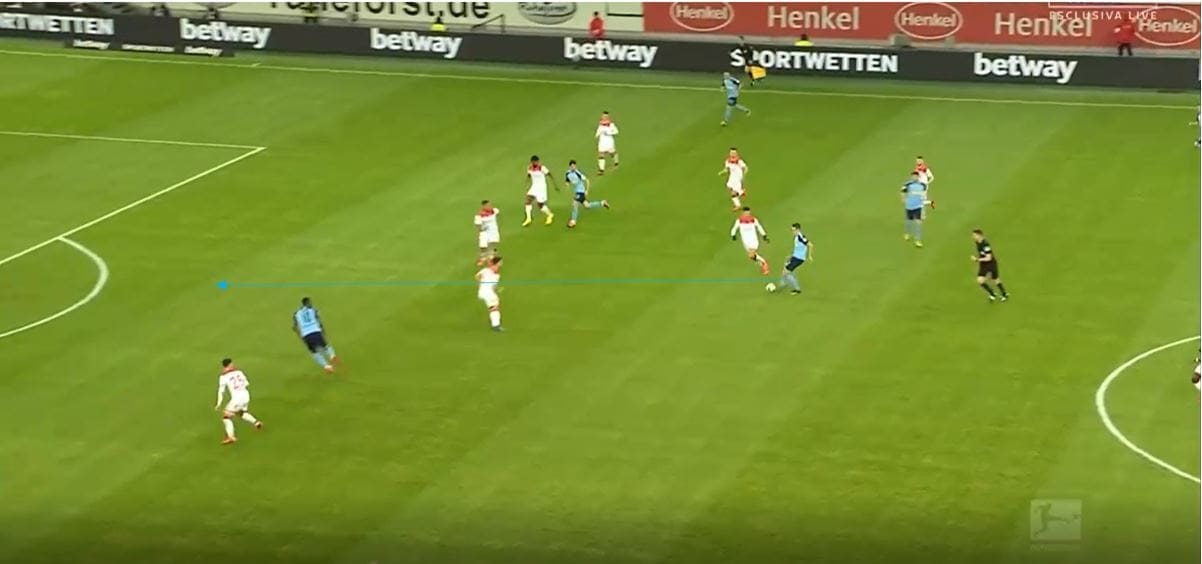

To be any kind of successful pressing team, you have to employ some kind of counter-press in order to sustain attacks and prevent the opposition from counter-attacking. This will be of utmost importance to Bayer Leverkusen. Against Werder Bremen Leverkusen’s counter-pressing structure was mainly ball orientated, with players rushing towards the ball carrier to quickly prevent counters. We can see an example of this below where Leverkusen immediately press as soon as the ball is lost. Leverkusen’s rest defence is likely to be much more conservative than against Werder, with the counter-attacking threat larger and the differences in player ability. It would make most sense for a rest defence structure that relies on vertical counter-pressing from the two central midfielders and nearby attackers, but for this, vertical and horizontal compactness is needed. This is something which Bosz’s side initially struggled with but seem to have drastically improved this season, which certainly has had an impact on their points tally.

Conclusion

This game is certainly the pick of the weekend, but as last week’s games showed, the games are somewhat unpredictable. In my last preview, the formations of Dortmund and Schalke were much easier to figure out and process than Gladbach and Leverkusen’s have been, simply due to the tactical flexibility Gladbach show. Gladbach have the ability to edit their press to the opposition, with the principles more important than the shape as a whole, and so this preview again is simply an insight into what might occur from both sides in the game, and how they can interact with one another. It is one of the games I’ve had marked in my calendar, along with Gladbach vs Flick’s Bayern Munich, and so I hope it lives up to its high expectations.

Comments