The first game of matchday 29 in the Bundesliga this weekend saw Bayer Leverkusen travel to the South-West of Germany to take on Freiburg at the Schwarzwald Stadion. Freiburg came into the game in inconsistent, if not slightly disappointing form, having failed to win since the restart of the league, picking up a healthy draw in Leipzig before falling to a disappointing defeat the week after against Werder Bremen and most recently drawing with Frankfurt. Leverkusen, on the other hand, looked as though they had made a perfect start to the return, picking up convincing victories over Bremen and Gladbach, before falling short to Wolfsburg’s fantastic set-pieces in a 4-1 defeat. As a result, Leverkusen were looking to get back on track, and it was a perfect game for them to do it.

If you have read any of our previous Leverkusen analyses you will know they are a team who favour a possession-based style of play where they look to use their positional play in order to create chances. Freiburg on the other hand, are a defensively solid side who look to frustrate teams by sitting deeper and playing on the break, and so stylistically this was an interesting match for both teams. It was clear then that patience was going to be a key part of Leverkusen’s approach, and their patience only had to last 54 minutes before Kai Havertz scored the only goal of the game, which we will, of course, come to. In this tactical analysis, we will look at how Bayer Leverkusen were able to solve their initial struggles and ultimately break down Freiburg using their positional play.

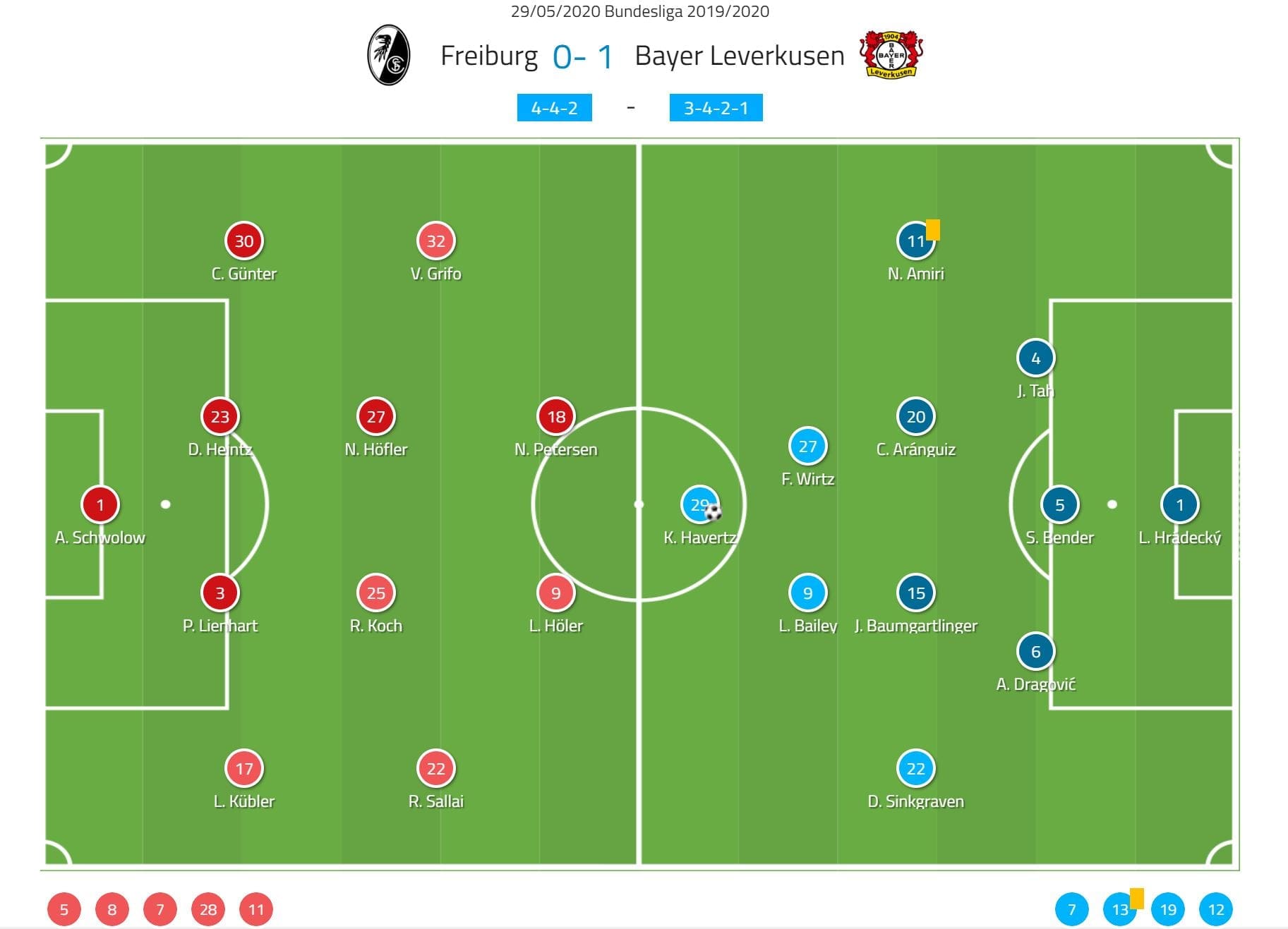

Lineups

Freiburg lined up in a characteristically compact 4-4-2, with Nils Petersen and Lucas Höler leading the line and taking a more passive role out of possession. Leverkusen meanwhile lined up in a 3-4-3, with their front line extremely fluid in order to benefit their positional play and help create overloads throughout the pitch.

Freiburg’s defensive structure

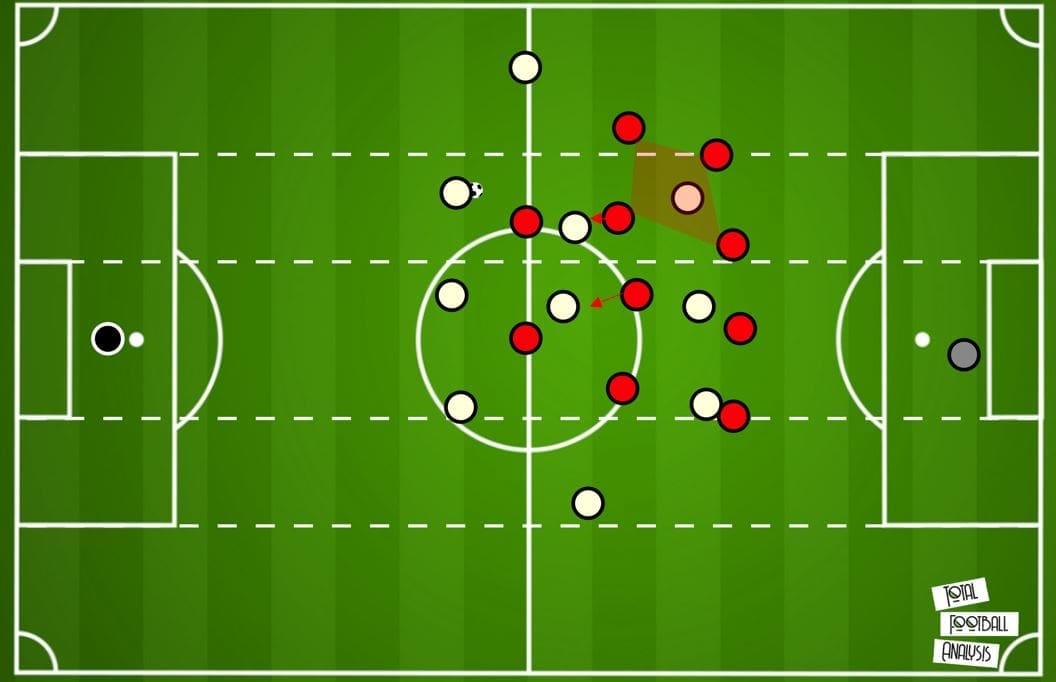

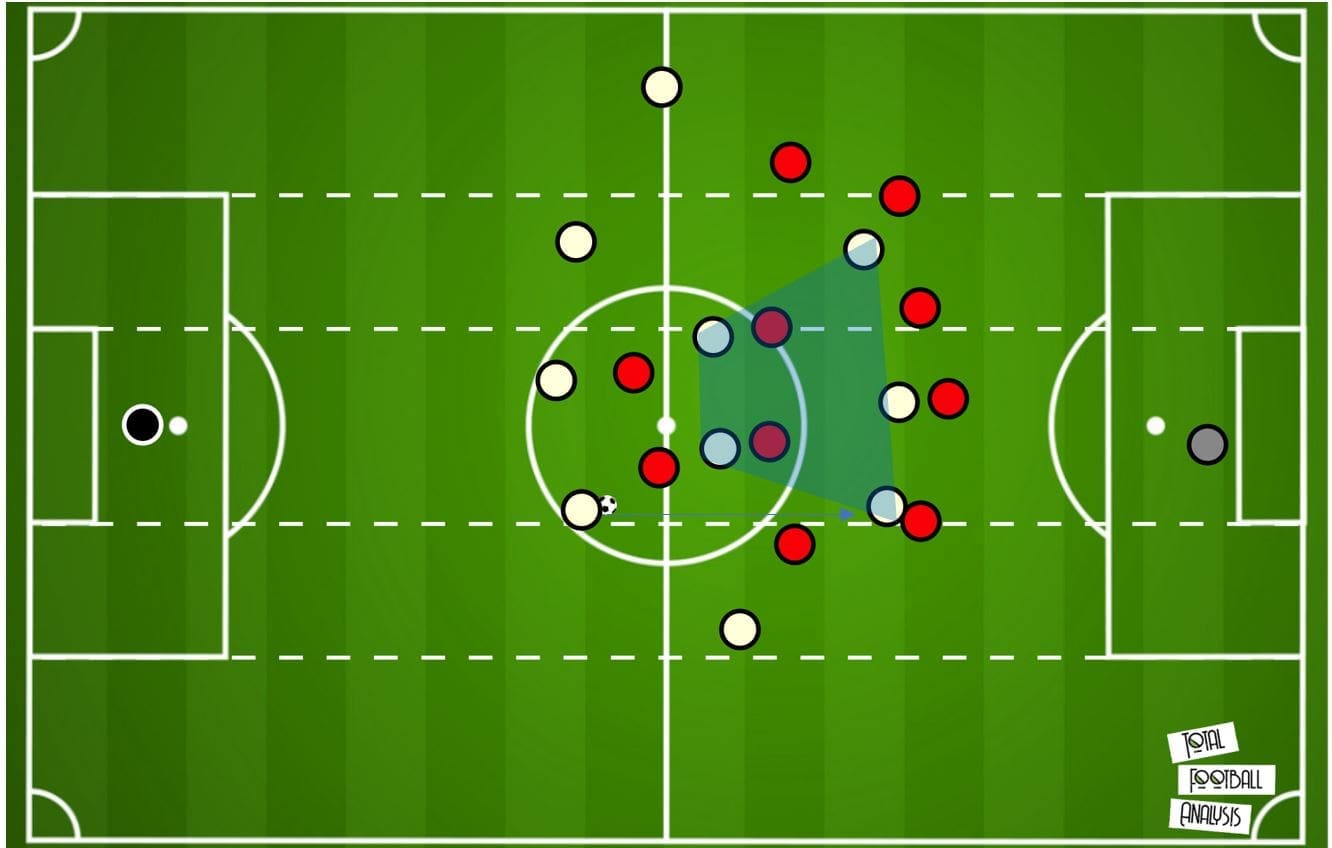

The general structure of the match itself can be summed up simplistically in this diagram below. We can see the setup Freiburg looked to utilise, with a very passive 4-4-2 press in the first half frustrating Leverkusen well. The strikers would often put little to no pressure on the centre backs, instead occasionally looking to block central passing lanes and help occupy the central midfielders, who were also marked by the Freiburg midfield. Freiburg were prepared to attempt to limit the amount of progression Leverkusen could do through the half-space, and their structure helped this a lot as I’ll mention.

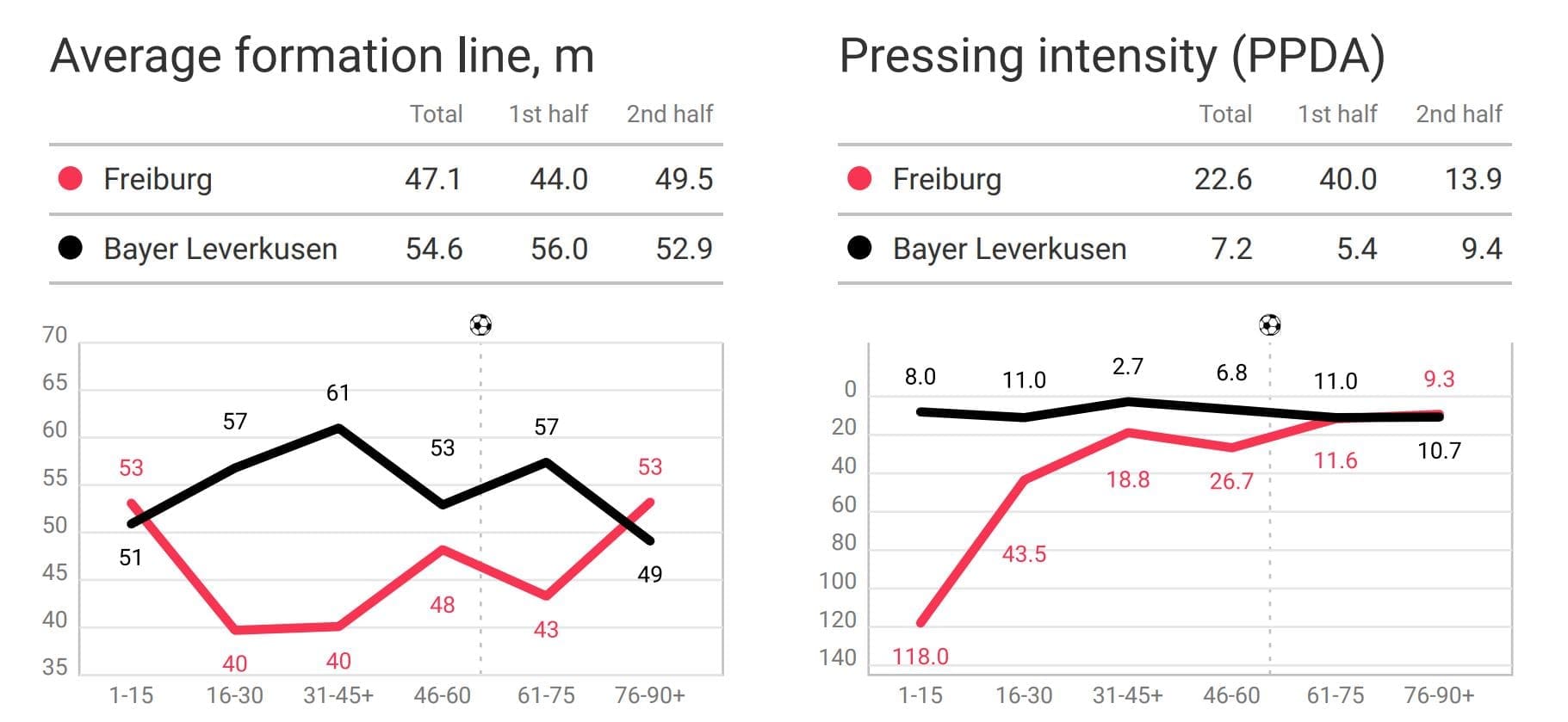

We can see evidence of that passive approach here, with these graphs highlighting the average formation line of both sides and their PPDA. Freiburg had a remarkable average value of 40 for their PPDA in the first half, which obviously suggests a very passive approach which allowed Leverkusen to control possession and look to try and dictate play. They were also relatively deep throughout the game, looking to remain compact to limit space.

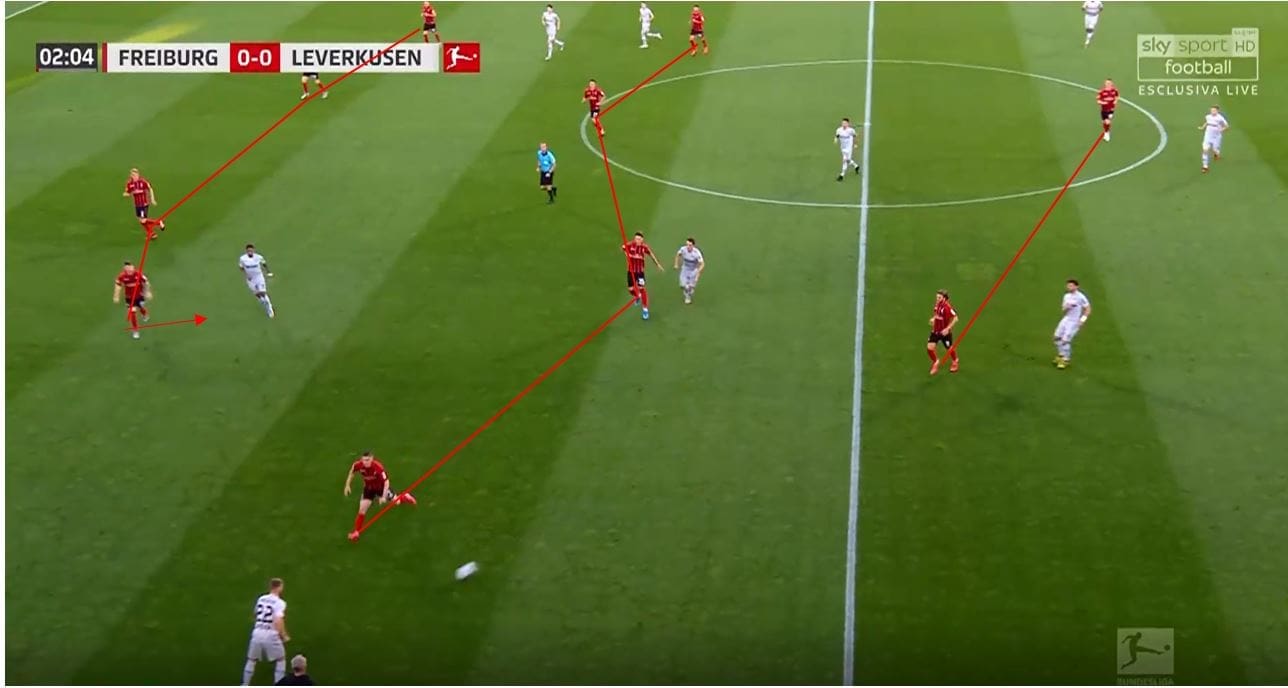

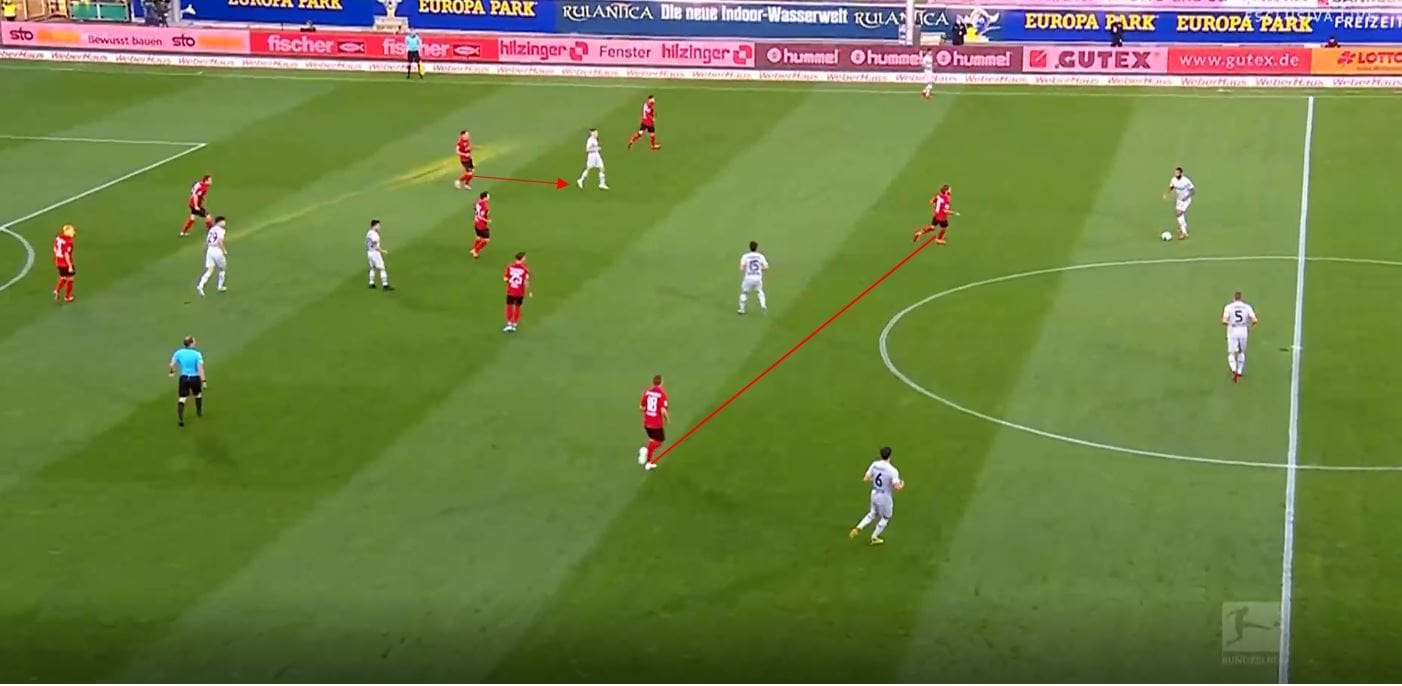

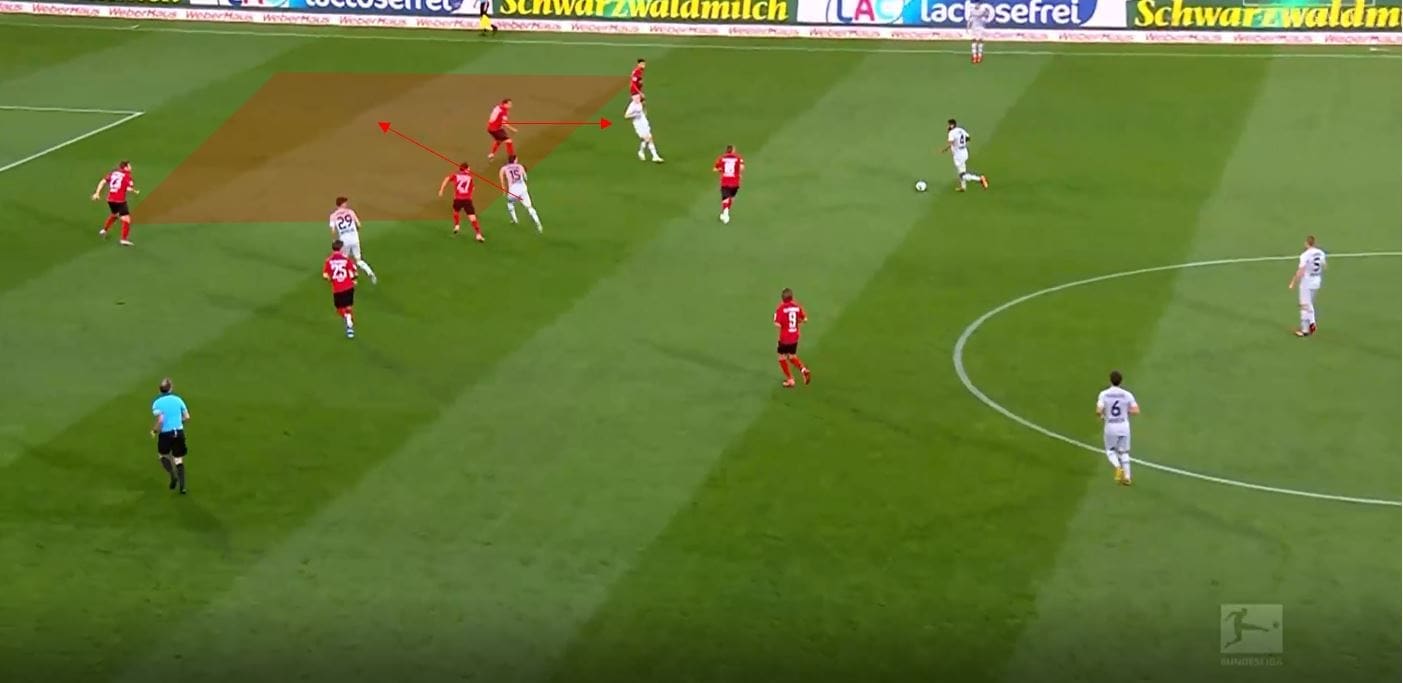

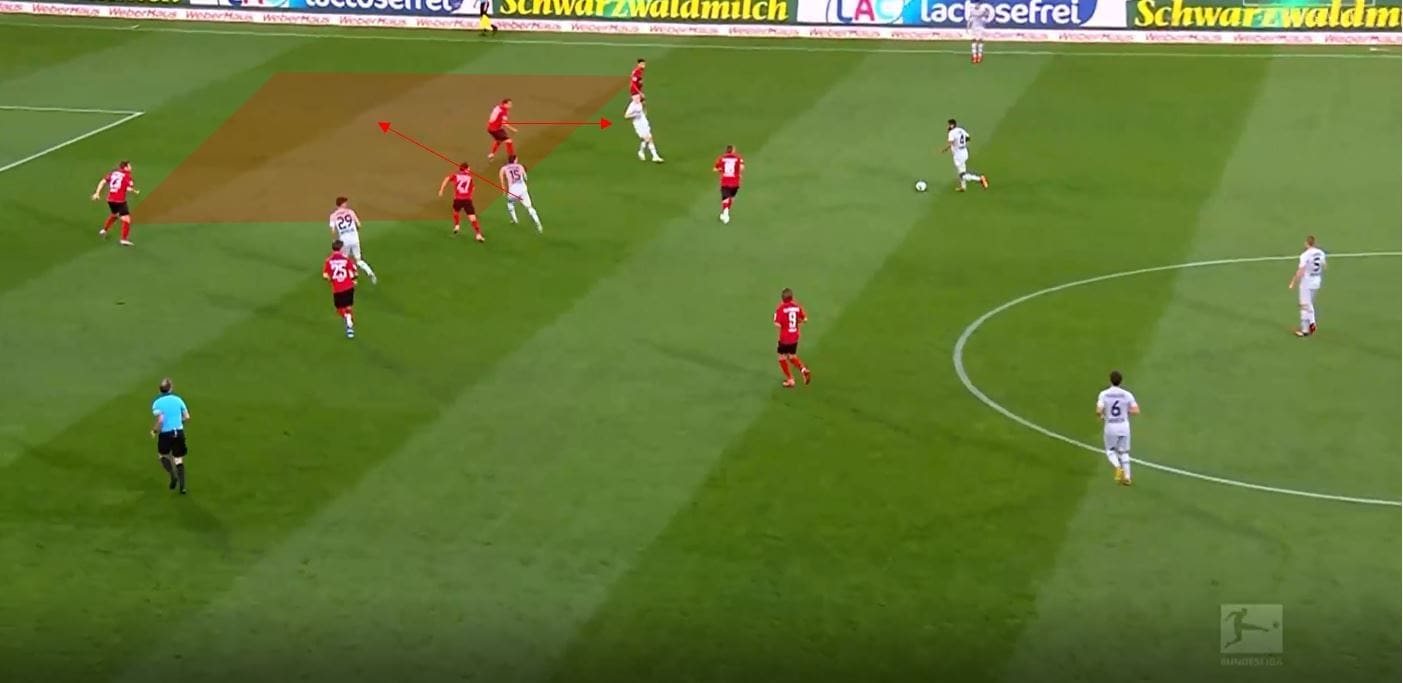

We can see a good example of Freiburg’s 4-4-2 here, with the winger pressing the Leverkusen wing-back. The central midfielders remain tight to their opposite central midfielders, while the strikers do relatively little in the play, staying central and applying some limited pressure at times. We can see how wary Freiburg are of the half-space already in this image, with Freiburg’s full-back often tucking inside and remaining tight to the inside forward as they do here.

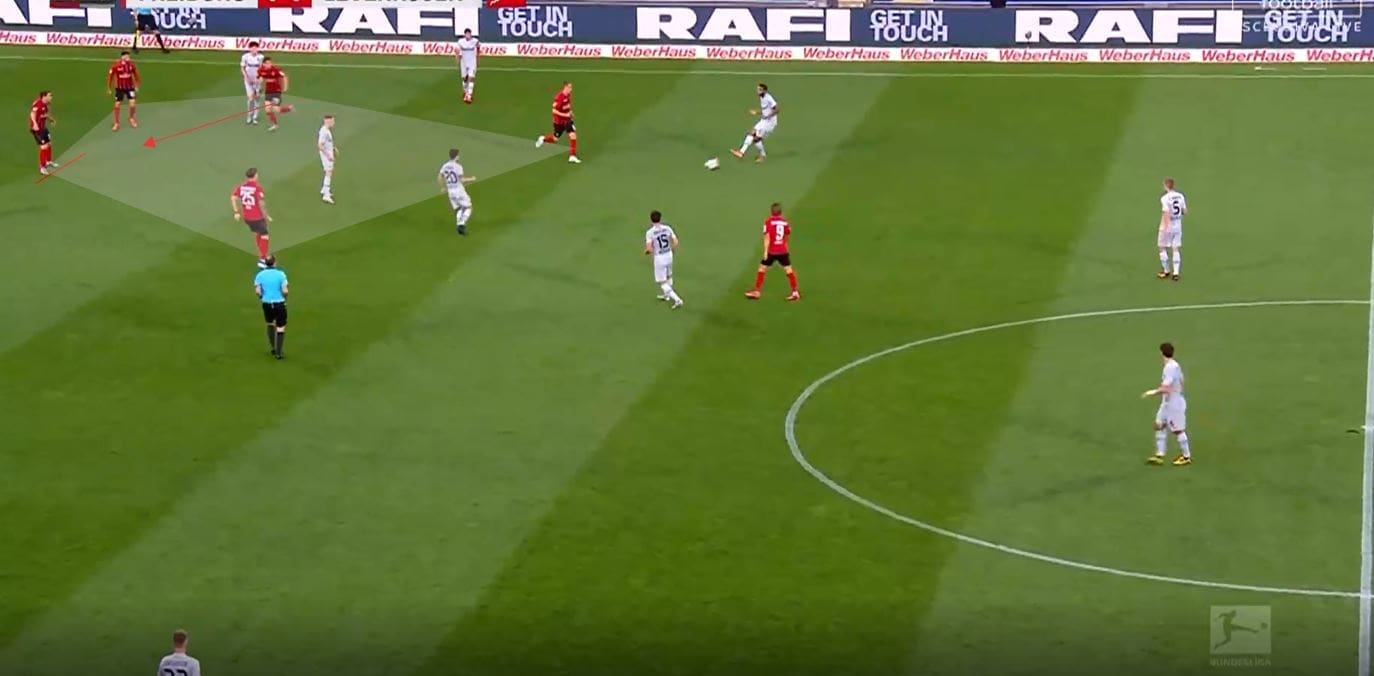

Again here we see a block being employed, with the full-back here not being afraid to step out and follow Florian Wirtz in this case, who was used as an inside forward to occupy the half-space and often dropped deeper to receive. Again the strikers apply some pressure with Leverkusen’s whole side now in their half, while the central midfielders look to occupy the middle.

One of the key aspects in Freiburg’s solidity was just how deep they were, and the effect this had on their player’s roles within the formation. Usually, an advantage to a back three being used by an in possession side is their ability to stretch the lines of the opposition and force a press from the second line. We can see an example of this here when Gladbach switched to a back three against Schalke a while back, with Schalke in a 4-diamond-2. Schalke’s two-man press became stretched and was then broken, with the wide centre back therefore under no pressure and the second line having no shielding. As a result with the first line stretched, the second line has to jump to help if the team wants to actively win the ball back.

We saw this same principle in Hertha’s smashing of Union, where Hertha used a back three to force one of Union’s central midfielders to engage and hopefully give up space in the half-space, although Union’s 5-4-1 changes the dynamics slightly due to higher coverage along the defensive line.

Freiburg however, were not so interested in winning the ball back, and so as mentioned really did sit deep in a deep block at times. This depth allowed the strikers to remain shielding the second line somewhat, and because they were so deep and compact, they didn’t need to commit players from their second line to jump to press. Instead, they could rely on the strikers to shuffle across with switches in play, and purposely made a point of not committing players from that second line. This allowed them to maintain numerical equality in the half-space for the majority of the first half, with Leverkusen relying on cute, clever combinations in very tight areas and good dismarking movements. We can see all this here, with the centre back given time on the ball, but limited options thanks to that organised, rigid 4-4-2.

Leverkusen’s initial positional play struggles

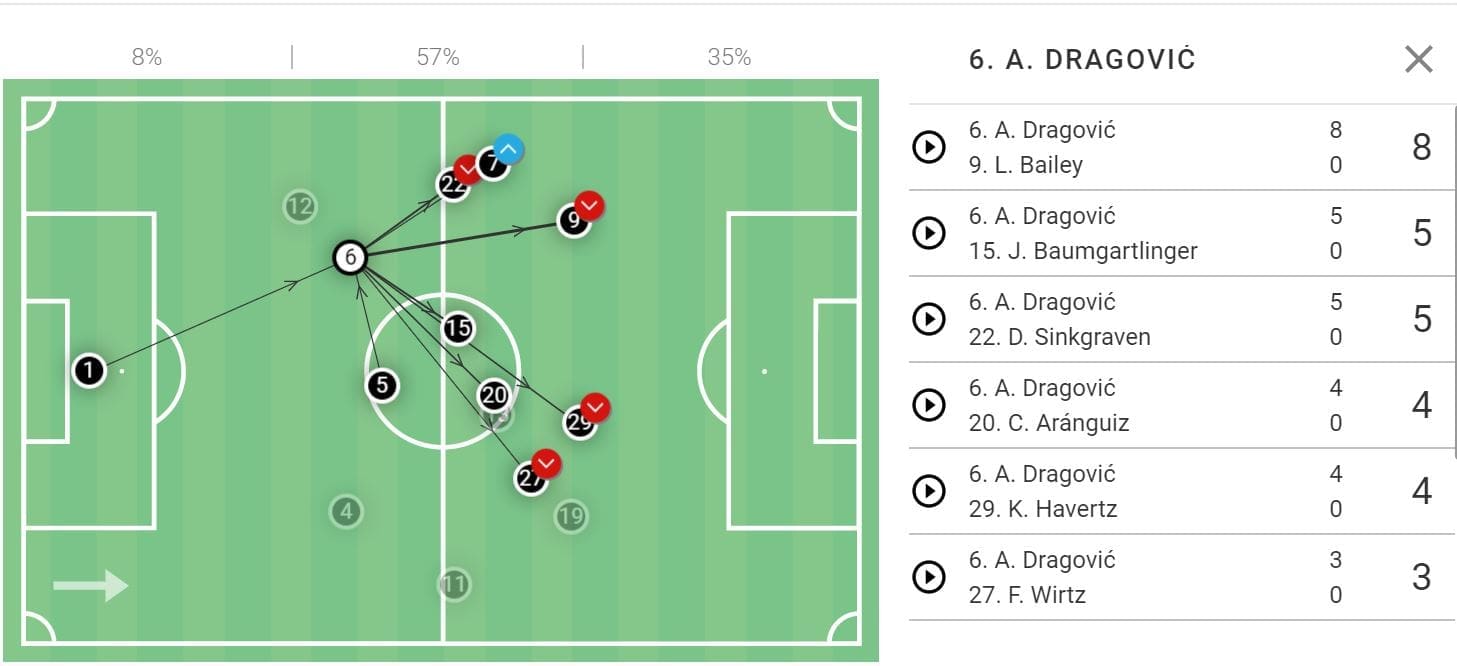

As a result of this compact system Freiburg used, it was always going to be a difficult, perhaps time-consuming task to break them down. Leverkusen, as I’ve mentioned, rely on the half-space greatly to create their attacks, and use their wide centre backs to look to access this area. The problem for Leverkusen wasn’t, however, their lack of access to the half-space, it was what they did once they got in. Both of Leverkusen’s wide centre backs show a trend in their forward pass maps, with the inside forwards on their side receiving the ball often. We can see here wide left centre back Aleksandar Dragović’s passing map, with left inside forward Leon Bailey receiving the ball eight times in the game from the centre back. On the opposite side, Jonathan Tah and Florian Wirtz linked five times.

This amount of access was possible because of the 3-4-3 formation used by Leverkusen in possession, with its use against a 4-4-2 naturally lending itself to a midfield box. This relies on the central midfielders being used very centrally at times and being given the task of pinning the Freiburg central midfield in a central area, while the wide players help to open up the lane to the half-space or ever so slightly outside here. However, in the game, these passes into this area were largely ineffective, to begin with.

These passes had two problems surrounding them. The first is the sheer lack of space available, which again was thanks to Freiburg’s solid structure. In situations like this, it is difficult for Bailey to work much, however, this is something which is difficult to control sometimes against teams like Freiburg. Players have to be capable of playing in tight areas with their back to goal if they are to be successful in the half-space, Mohamed Salah and Sadio Mané are good examples. But for Bailey to progress play here, he also needs support from his teammates, who with effective movement can overload the half-space and cause problems.

We can see again here a pass into the half-space for Bailey, where the Jamaican can’t progress play without an overload, and is pressured from behind by the full-back. This leaves space behind the full-back, but Bosz’s side seem to not like using this particular method of progression in this area.

This situation was actually a common occurrence in the game, due to the aggression of Freiburg’s full-backs and their willingness to follow out to close space. Again we see the space in behind opened up, and this was as far as I noticed the only time in the first half in which Leverkusen threatened a ball in behind aerially in this way.

Teams obviously cannot create overloads every time in the half-space and will try to progress play without an overload at times for counter-pressing reasons and also to commit players higher in other areas. Leverkusen initially did struggle, however, but time and patience are always big factors in these kinds of games. Some of these passes into the half-space can also be used as circulation tools to move the opposition around and create small gaps too.

Leverkusen overload and combine in the half-space

Of course, Leverkusen did start to break Freiburg down more and more often and did it through that overloading I’ve mentioned so far. Kai Havertz’s goal is a good example of them improving their movement from the images above.

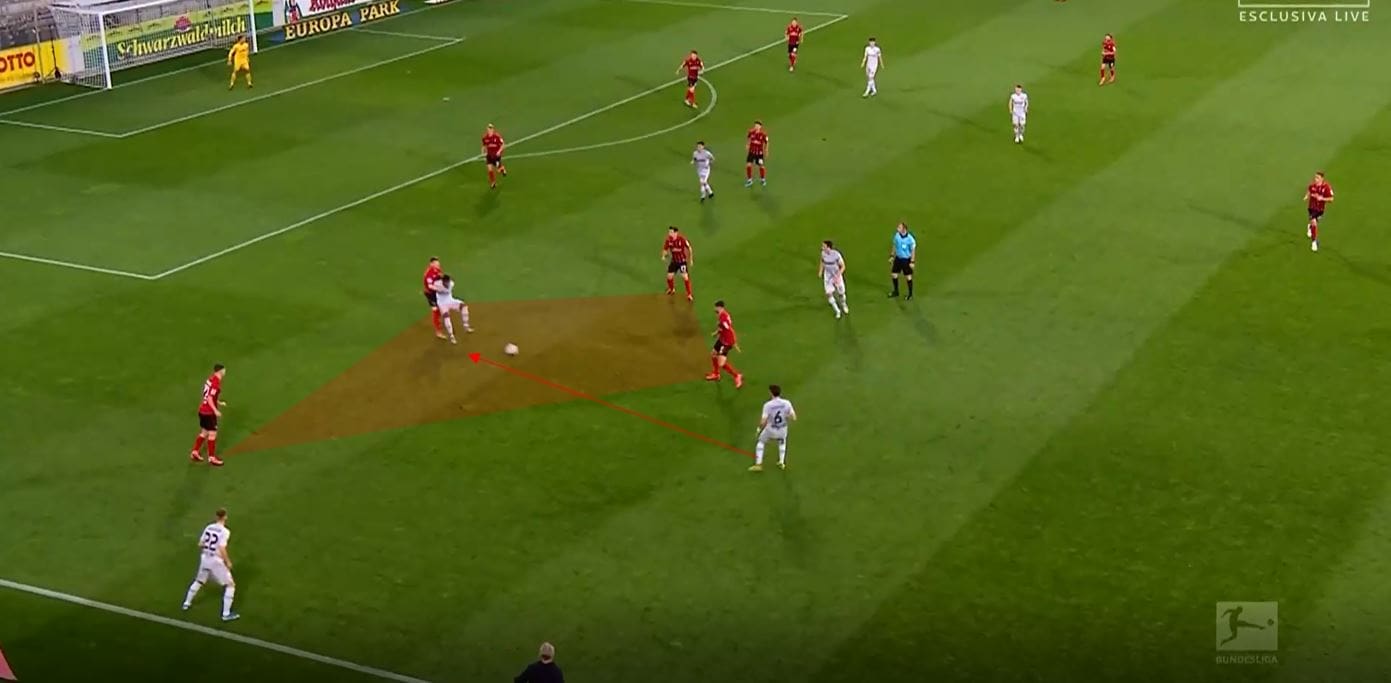

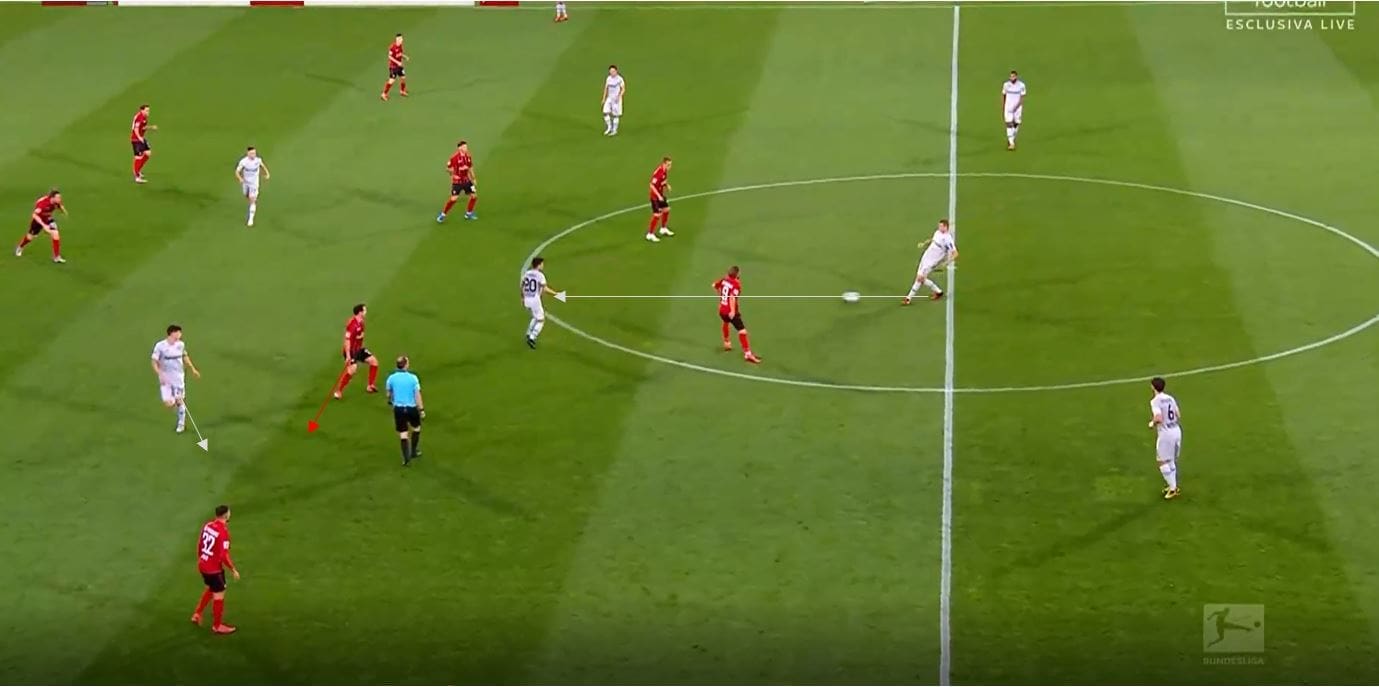

Here we see one method of overloading the half-space, with false nine Havertz moving across to support Bailey. Havertz makes a blindside run to receive the ball and at the same time occupies the Freiburg centre back, with Bailey sat deeper initially and in the Freiburg full back’s eyes, in a safe position. Leverkusen progress the ball easily with Charles Aránguiz not pressed by a passive Freiburg, and Bailey is then able to exploit the space in behind the centre back, effectively creating a 2v1 around this centre back. Havertz follows up his pass and a few seconds later receives a through ball from Bailey inside the box and Havertz finishes from a tight angle.

We can see again here, Leverkusen create an overload in the half-space, with a 3v2 eventually created when the central midfielder comes across too. These small split second overloads allow for space to be created and passing lanes to form, which ultimately lead to through balls after quick, tight combination play. The benefits geographically and spatially of the half-space also help to progress play effectively, with the angle and vision of the players in the area optimal.

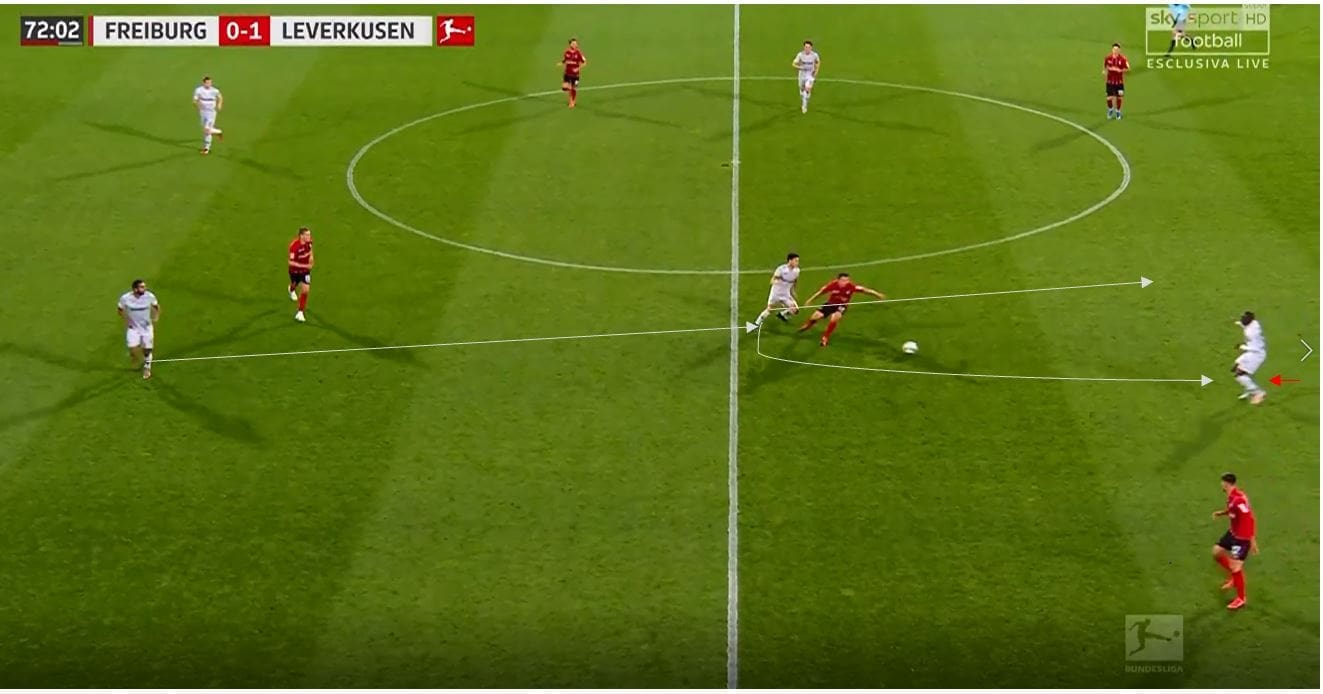

This example here comes from Dragovic accessing Havertz in the half-space, who flicks the ball around the corner to wing-back Daley Sinkgraven. With Havertz dropped into Bailey’s half-space, Leverkusen can create a 2v1 potentially, and use a nice coordinated movement to receive the ball and help utilise the extra player in the half-space. It’s a simple movement but one which creates a temporary overload on the nearest centre back, with Bailey dropping to receive while Havertz continues forward. This threatens the centre back both in a deeper and higher area, and so creates a decisional problem, which is what positional play is all about.

Here we see Havertz’s intelligence again, with a decoy movement from a central area slightly dragging a central midfielder across in a position where it probably shouldn’t. As a result, the central midfielder is able to receive in slightly more space, as a result of Havertz temporarily giving the midfielder two things to think about.

Here we see Leverkusen look to run from deep and arrive into space to occupy, which benefits the body orientation of the deeper player and therefore aids ball progression. Here the central midfielder curls a pass round his marker and sprints into the space left by his marker. Diaby here is pressed from behind aggressively by the full-back as expected, and so the central midfielder can then run into the space left by the full-back. As a result, this is a temporary 2v1.

This final example here shows well the effect those previously mentioned simple straight passes can have, with the full-back initially forced to push out to press a player occupying the half-space, who receives and pulls the player out of position. The centre back then tucks across horizontally to cover the space left, but when another player then occupies the half-space, the centre back won’t commit to press. As a result, space is conceded and Wirtz can turn. This isn’t something they utilised often and is certainly something they could consider for future games.

Conclusion

This analysis has solely focused on the attack against defence nature of the game, with Leverkusen’s positional play and Freiburg’s defensive system detailed. Leverkusen dealt with the limited offensive threat Freiburg could muster from such a deep shape, and Freiburg posed little threat from set-pieces which was unexpected. Despite the positional play concepts highlighted, many of these were performed in isolation and so Leverkusen did struggle in parts, and it certainly wasn’t the best performance they have put in, but at the same time, it was still a good performance worthy of winning the game. Freiburg were limited to one real chance in the game but both sides produced less than 1.0 xG, and as a result, Freiburg will be largely happy with how their defensive system coped with Leverkusen. Despite that, it was an entertaining game which lived up to its stylistic billing, and one which kept Leverkusen on the path to the UEFA Champions League.

Comments