As the only top-six club to play on Sunday, RB Leipzig visited Mainz at an empty Opel Arena on the 27thmatchday of the Bundesliga season. The previous matchup between these two sides resulted in a dominant 8-0 thrashing in favour of Leipzig, including a Timo Werner hat-trick. Both Mainz and Leipzig had recently drew their matches last week against Köln and Freiburg respectively. This tactical analysis discusses the strategies of both teams and explains how Leipzig were able to yet again control the contest from the outset.

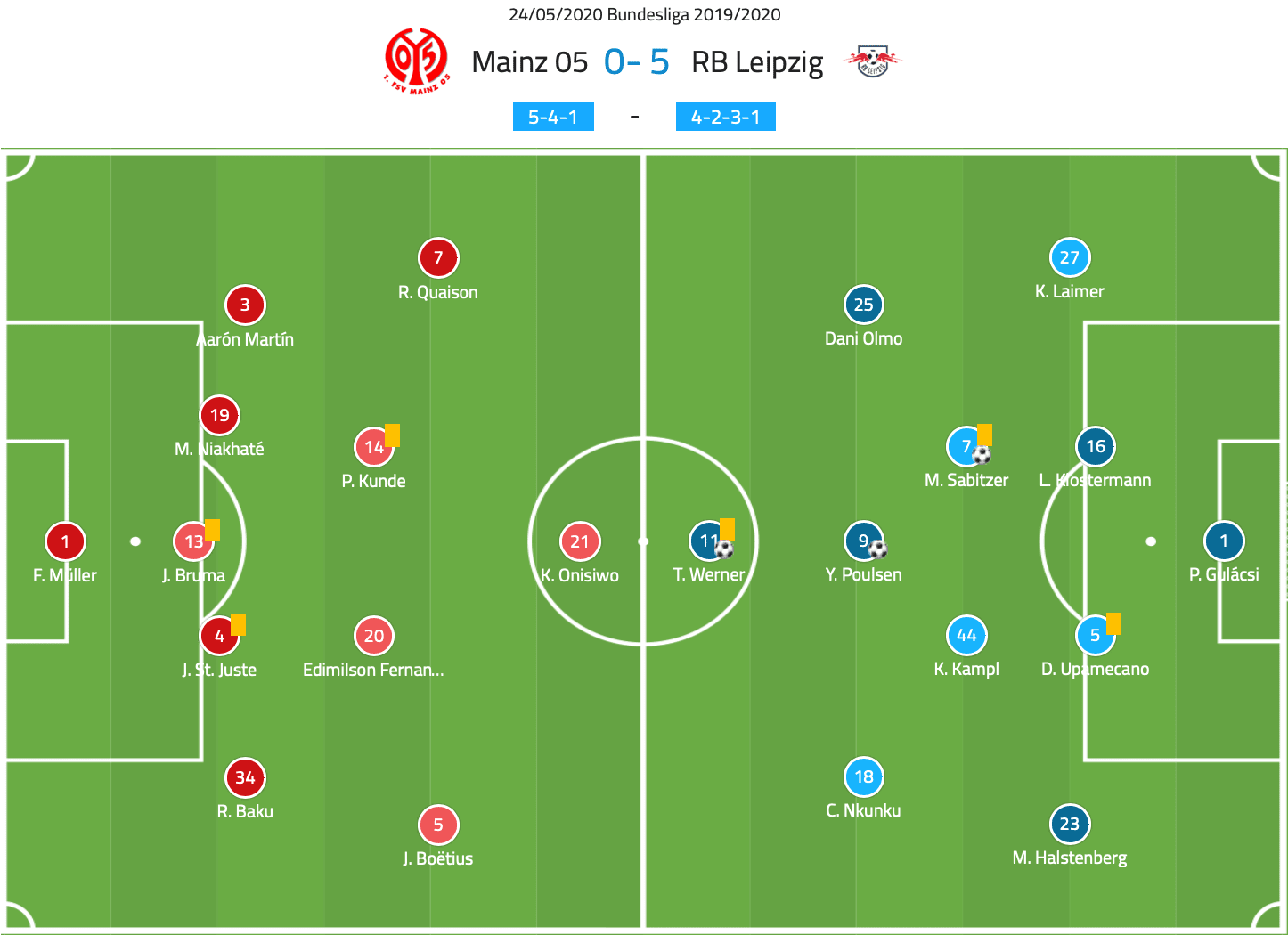

Lineups

Mainz began in a defensive-minded 5-4-1 setup that turned into a 3-4-3 in attack. Manager Achim Beierlorzer started a back five consisting of Ridle Baku, Jeremiah St. Juste, Jeffrey Bruma, Moussa Niakhaté, and Aarón Martín. The midfield line was shaped by Jean-Paul Boëtius, Edimilson Fernandes, Pierre Kunde, and Robin Quaison. Striker Karim Onisiwo started up top. Quaison is having his most prolific Bundesliga season yet, leading Mainz with 12 goals – no other teammate has more than four.

Leipzig manager Julian Nagelsmann organised his starting lineup in a typically flexible 4-4-2/4-2-3-1 formation with high defensive and pressing lines. Because of these positional intentions, he opted to only start one true centre-back, as Konrad Laimer, Lukas Klostermann, and Marcel Halstenberg started beside Dayot Upamecano. Dani Olmo, Marcel Sabitzer, Kevin Kampl, and Christopher Nkunku formed the midfield four. The complementary duo of Timo Werner and Yussuf Poulsen completed the starting eleven as a front two.

Finding space in the midfield

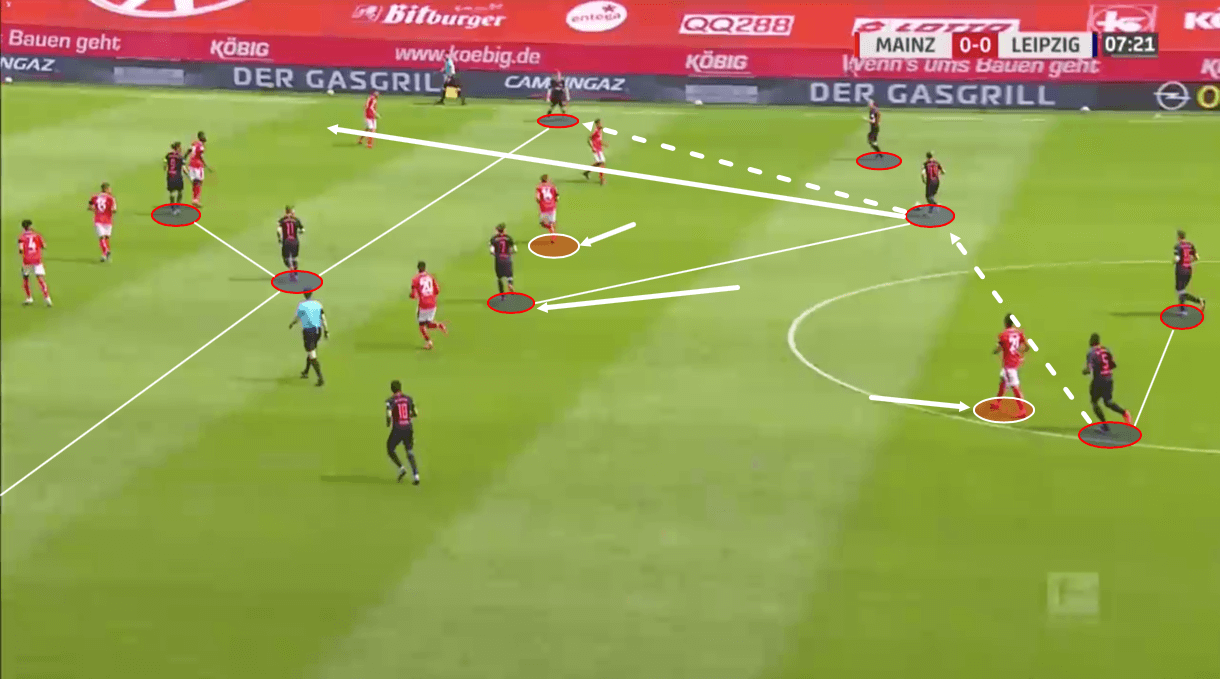

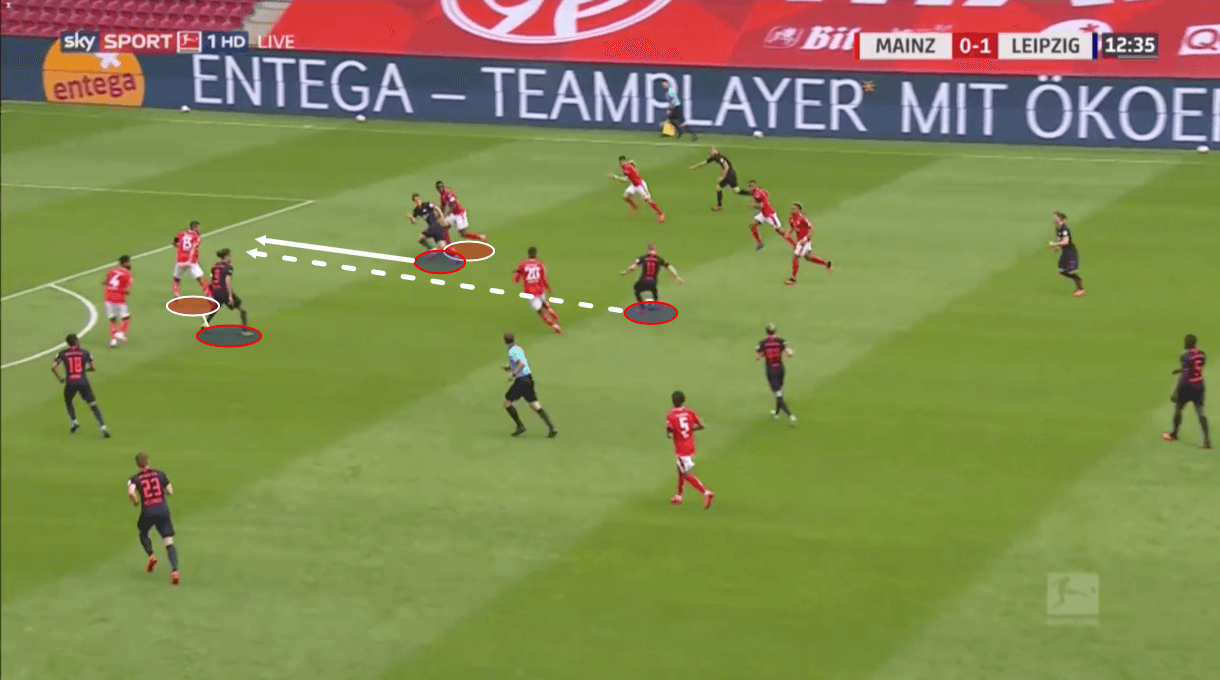

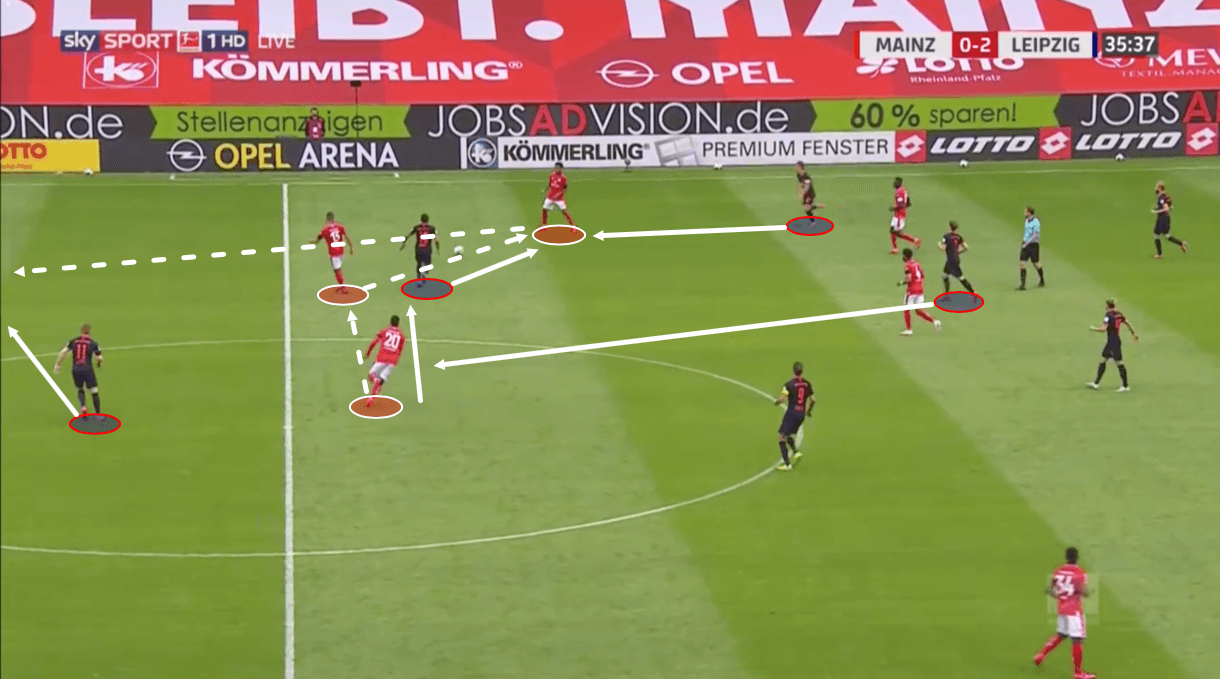

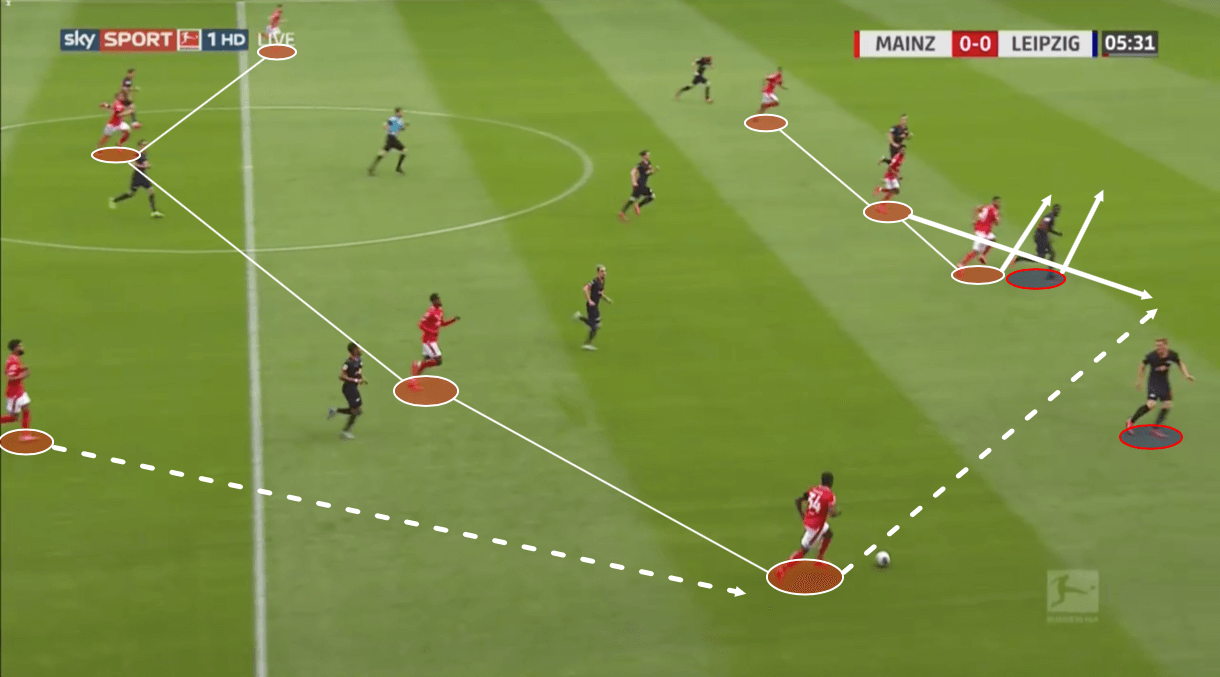

Nagelsmann is known for frequently pushing the envelope, often preaching the actual abstractness of formations and positions. This fluidity played a role in Leipzig’s buildup of possession from the back. In the buildup play below, the first action that occurs is Sabitzer’s movement forward in the central midfield area. This pulled the nearby midfielder Kunde back with him, freeing up Kampl for a pass from the centre-back Upamecano. Sabitzer and Kampl were pivotal in connecting the wide players and the backline with the attackers through their space-creating midfield movements.

Kampl then completed a diagonal pass wide to the right-winger Olmo and immediately moved to cover that position. Then, visible in the image below, Olmo completed a pass inside to Sabitzer, who was open in space due to Kampl’s run. Olmo then began an inside run, pulling the midfield defenders away from Sabitzer and into the space between the passing lanes. Now, Sabitzer has multiple options: he could either complete a pass to the wide area where there are no defenders thanks to Olmo’s movement, complete a pass vertically to Poulsen whose complementary movement with Werner has created a passing lane, or he could complete a switch of play to the far side wide area, which he does so in this scenario.

From there in many of these situations, Leipzig opted to move the ball into the wide areas of the final third before completing aerial and ground crosses into the box. Leipzig’s – and more specifically Werner’s – emphasis on volume was evident this match with a total of 20 shots, including eight for the German striker.

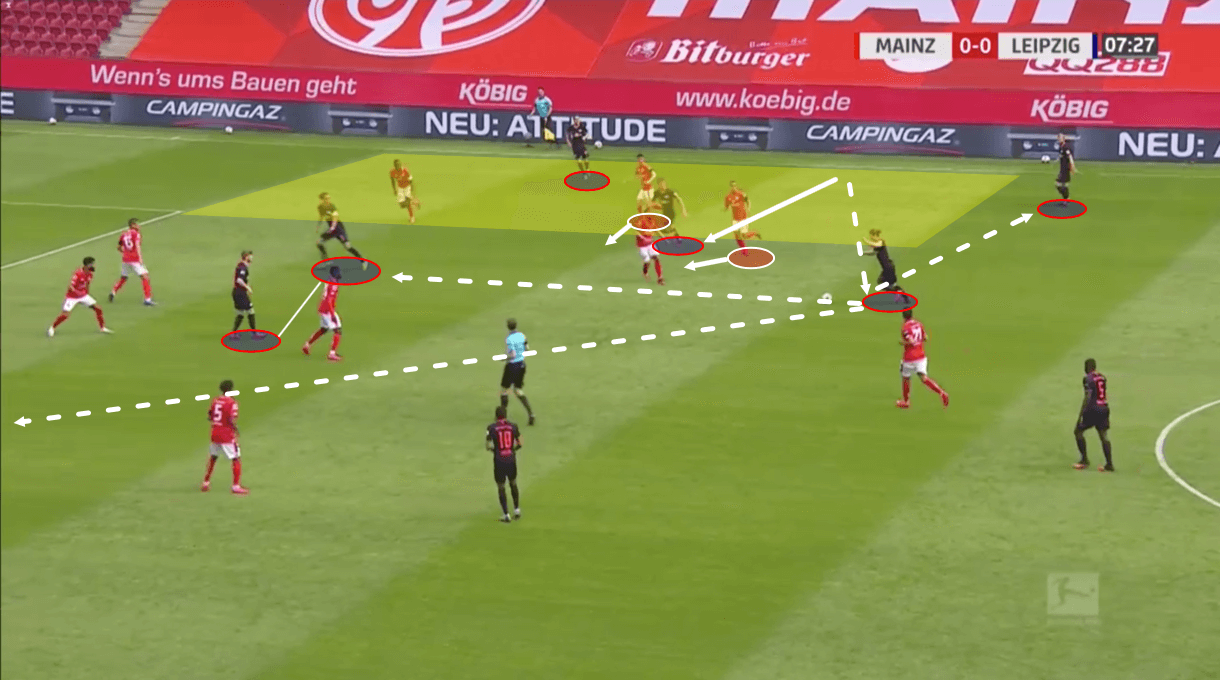

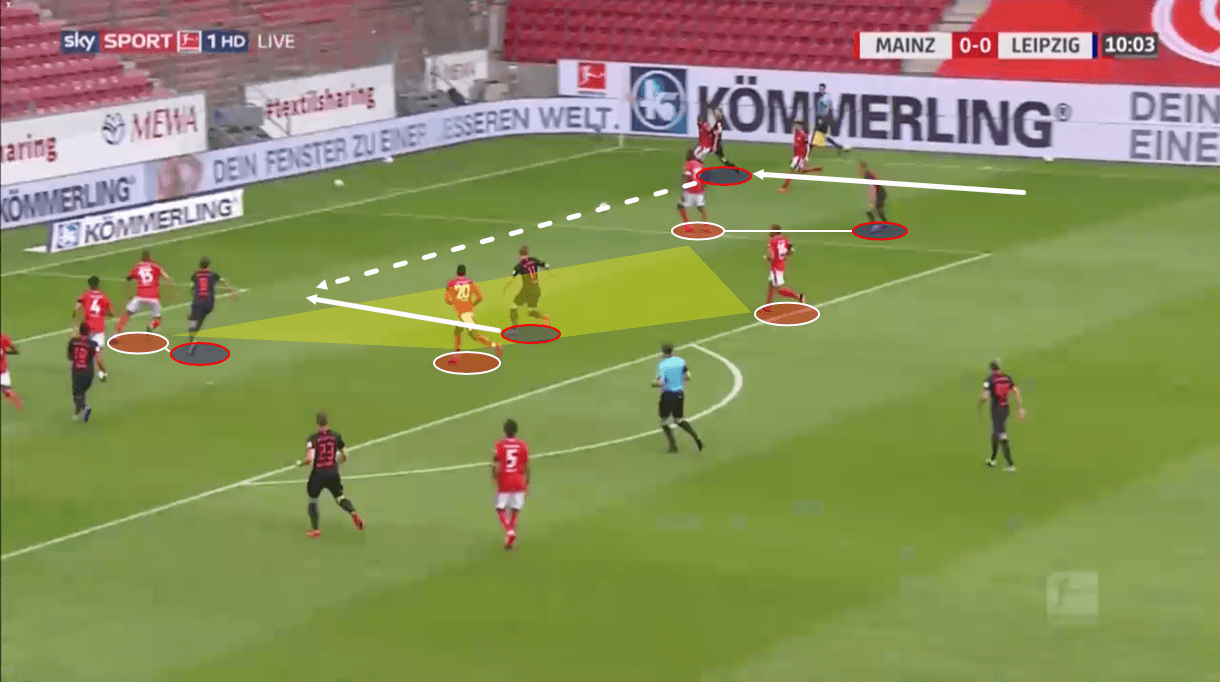

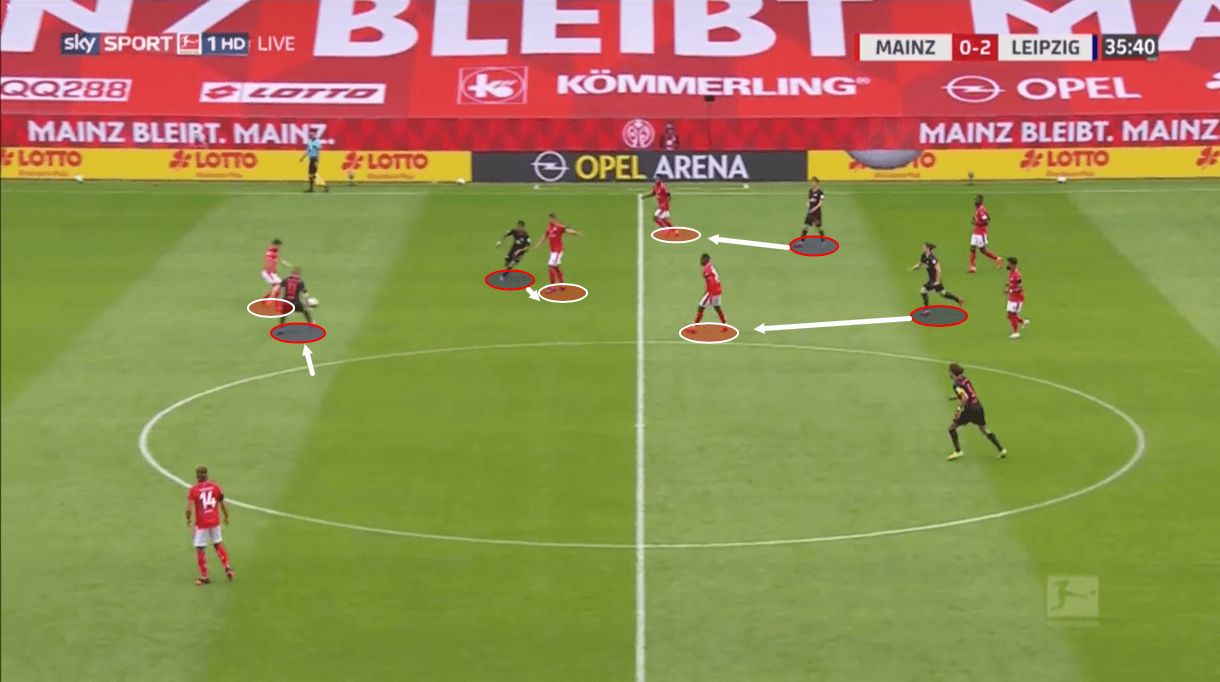

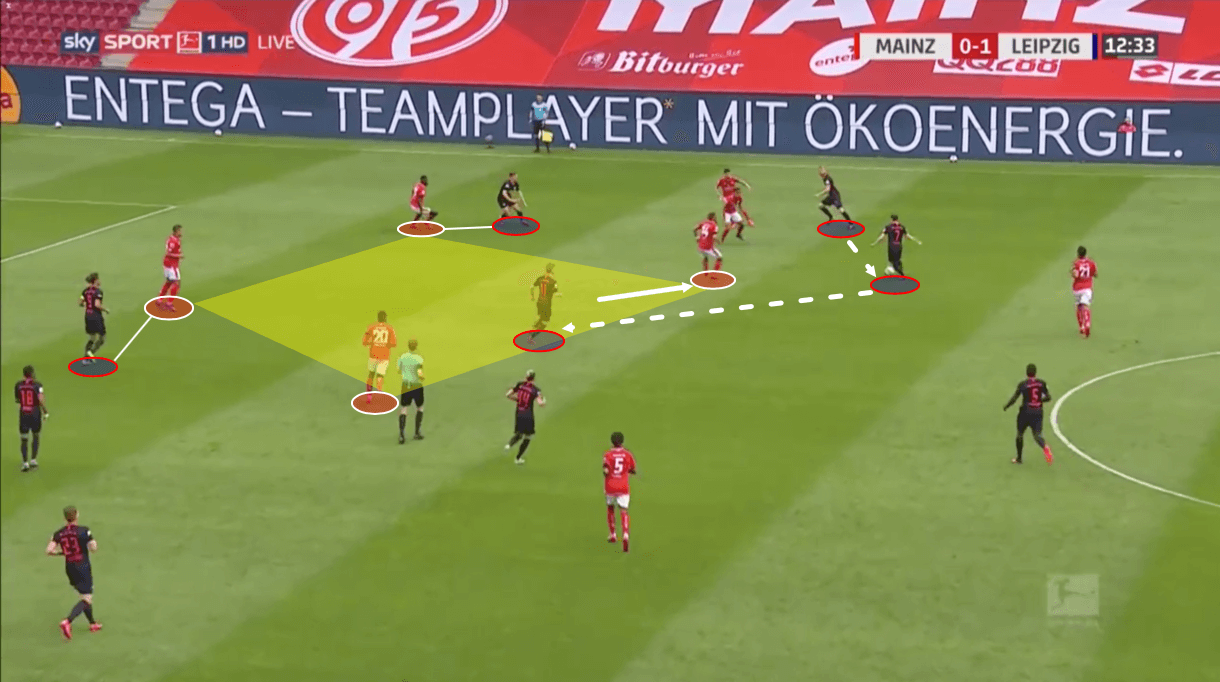

A common tactic Leipzig utilised during buildup play was a drop back positionally by the striker Werner. The German would drop centrally into the midfield line to aid in linkup play connecting one of the central midfielders and the wide players, and at the same time would be creating space in the opposing backline for his attacking teammates such as Olmo, Poulsen, or Nkunku to exploit. In the example below, we can see Werner already positioned comfortably in the centre of Leipzig’s attacking shape. As the pass from the right-back is completed inside towards the ball-side deep midfielder, the opposing ball-side central midfielder shifts towards the ball, opening up space for Werner.

Werner then receives the ball and has time and space to turn. Meanwhile, the two opposing ball-side centre-backs are stretched for two reasons. The lack of central striker means there is no immediate opponent between them, and the two nearest attackers are located on the outside of the centre-backs’ positioning.

This space however is recognised by the two attackers Olmo and Poulsen before the play is even completed. Olmo accelerates and makes a sharp run between the centre-backs down the right half-space, and the vertical pass from Werner nearly connects were it not for keeper Florian Müller’s awareness.

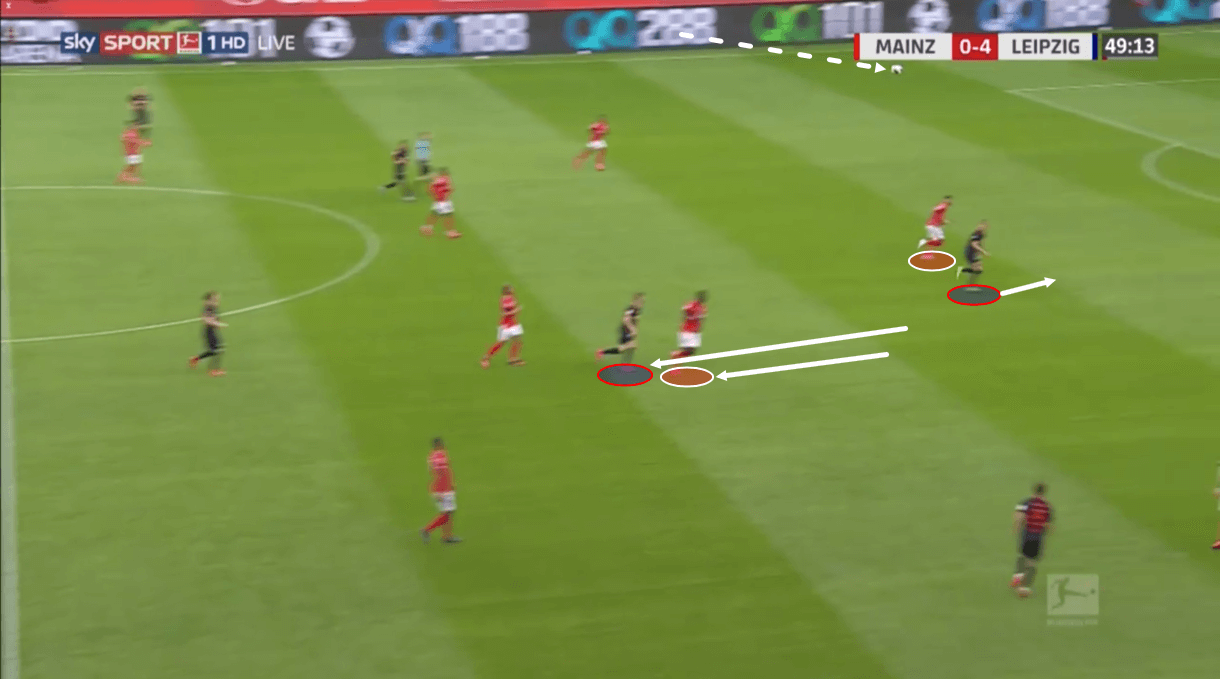

Below is another, more simplistic example of Werner’s drop in positioning creating space. As he drops back centrally, the nearest centre-back follows him, creating space behind the high defensive line of Mainz (positioned high due to the large deficit) for Poulsen to run towards. A long aerial pass over Mainz’s defence is attempted into this space.

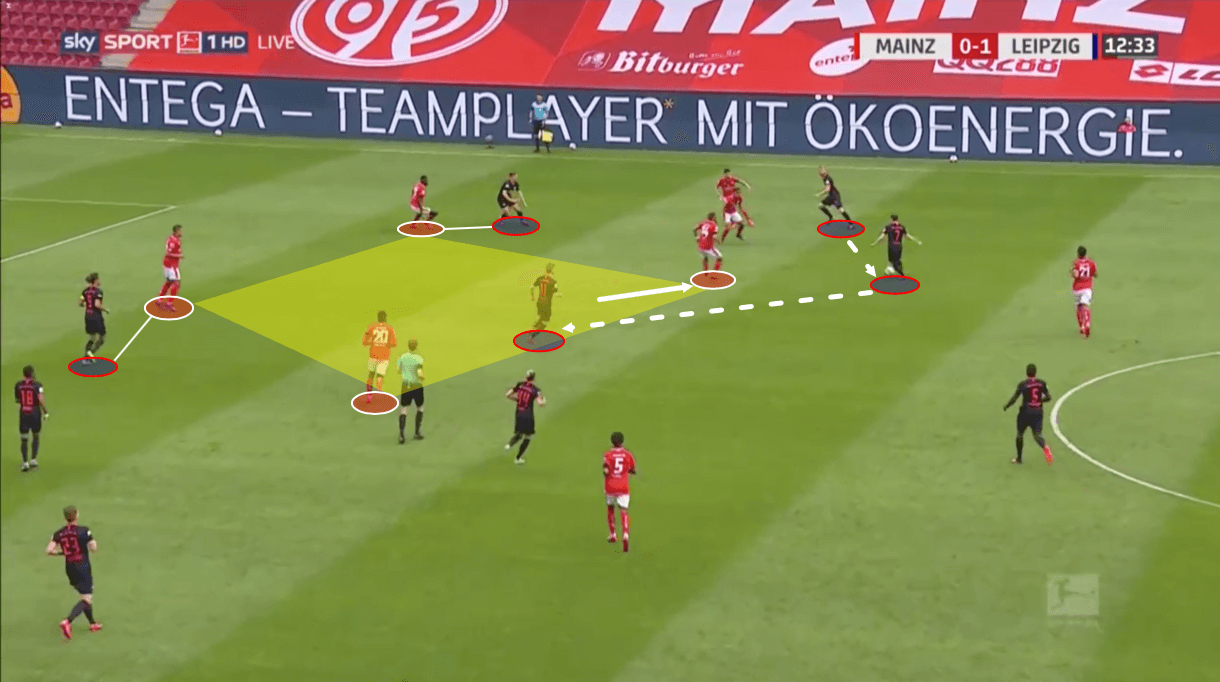

The other option for Werner in this situation is to move into the forward space himself. Werner is widely known for being one of the fastest players in Europe, and this tactic demonstrates an excellent method of using that strength against defensive-minded opposition. Below is a rather similar example to the first image of this section. Olmo and Poulsen’s positioning has spread the opposing centre-backs wide, creating space. The right-back Laimer aggressively and successfully dribbles past two defenders down the right wide area.

Werner, who was situated in the central midfield, bursts into the space between the centre-backs on a near-post run and receives the ground cross. The Mannschaft striker finishes a difficult 0.04 xG-rated shot to score the opening goal of the match.

This frankly simple yet brilliant tactic is another example of Nagelsmann’s ingenuity. The spatial freedom he allowed Werner made tremendous use of the skilled striker’s knowledge of space, despite the central areas of the pitch often (incorrectly) characterised as devoid of space.

Leipzig’s defensive intent

Leipzig also utilised the pace of the starting squad in defence. The club’s tactical nous of the press was well represented this match, and the high positioning of the back four relied on speed to recover opposition long balls in behind.

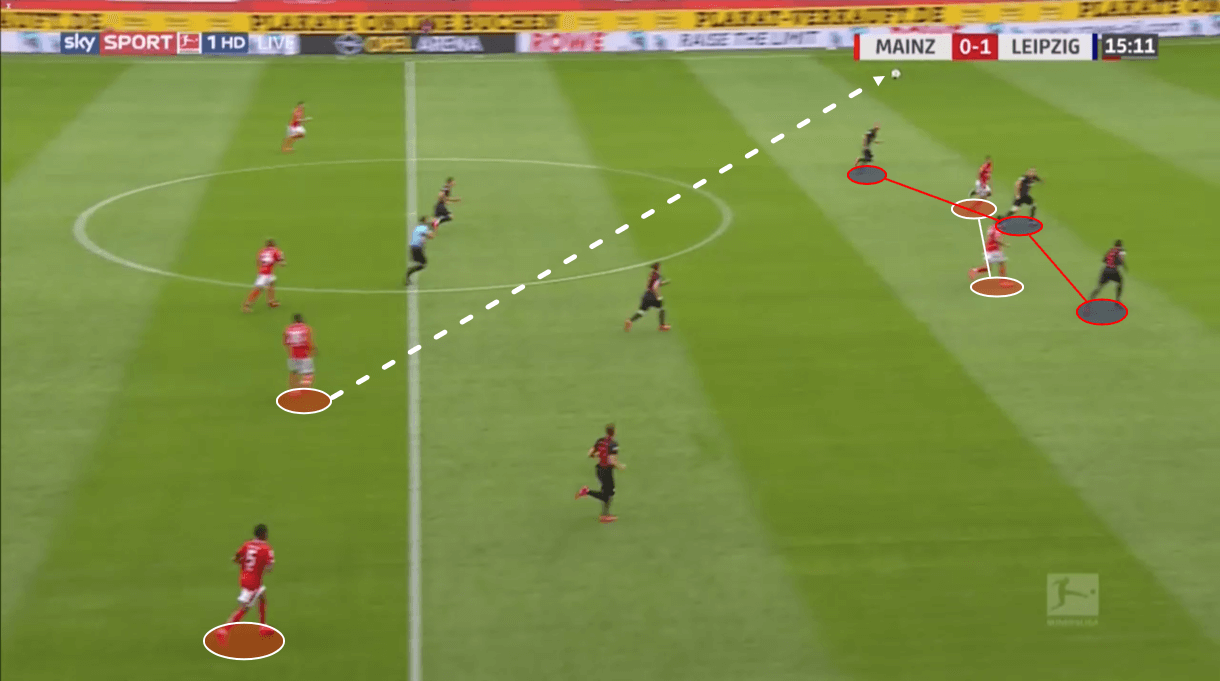

Right from the start of the match, Leipzig’s front press was evident. Their intent was to press the ball into the wide areas of the Mainz backline, thereby trapping the ball by blocking off any passing lanes and forcing a long ball for the defensive players to intercept. Above, the striker presses the central centre-back, who passes to the right centre-back. The left-winger then presses the right centre-back, and with the central attacking midfielder (in this case Poulsen) pressing the nearest midfielder and the far-side winger pressing the far-side midfielder, St. Juste had zero nearby passing options and was forced to attempt a long aerial pass.

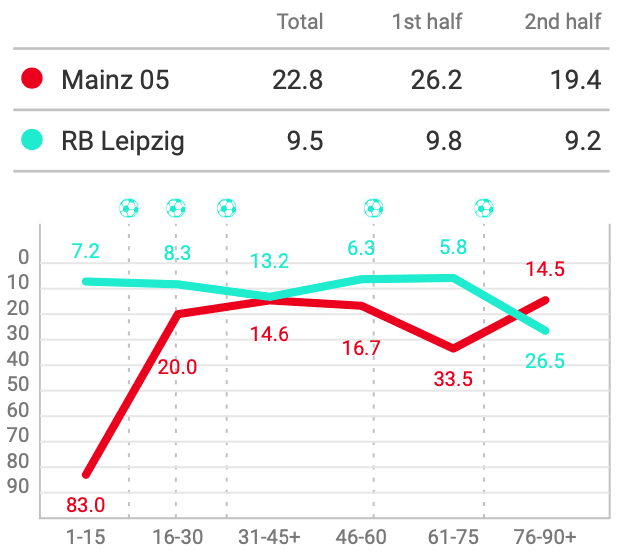

Leipzig’s consistent pressure on Mainz combined with the host’s porous defensive block meant Mainz had about half as many passes per possession as Leipzig (3.28 to 6.45) but twice the long pass percentage (13.4 to 6.38). Additionally, the PPDA values below indicate the consistency of Leipzig’s press.

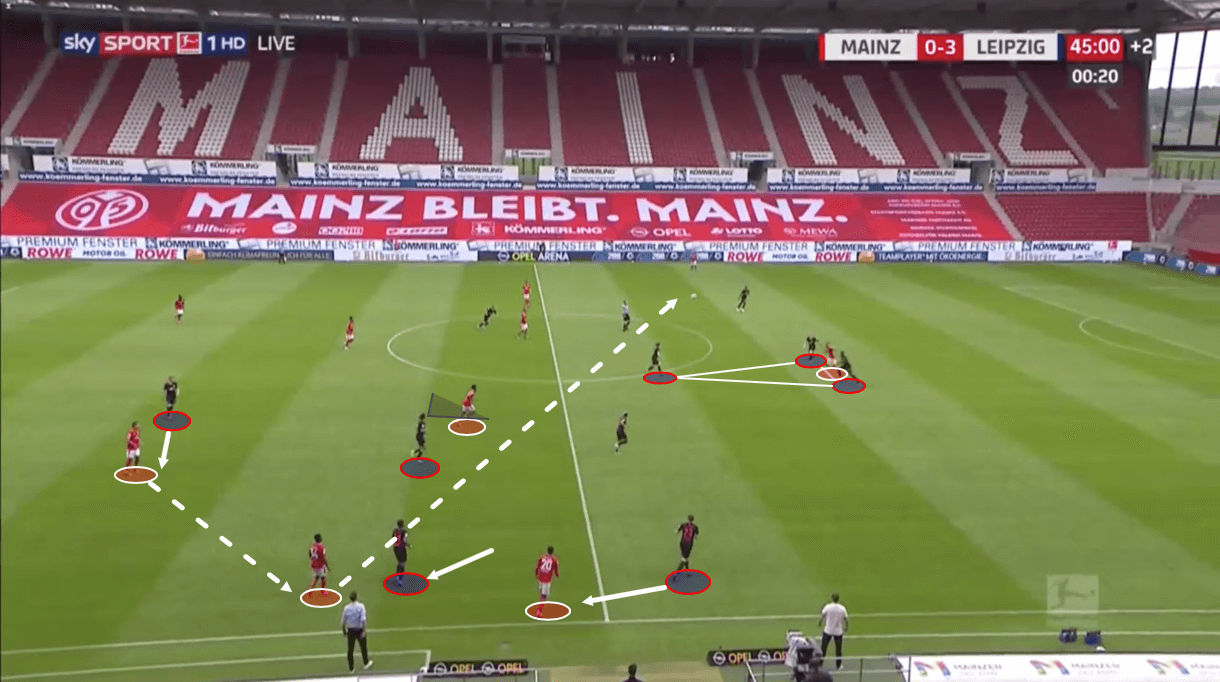

On an aggressive counterpress by Leipzig below, Nkunku continuously presses the ball from one side of the pitch to the other as Mainz rotates the ball through the deep midfield. His persistence along with the right-back’s press forces a backpass, which Werner presses. During this time, Sabitzer vertically presses through the levels of Mainz’s formation and joins the forward press.

Now, Leipzig have created a 4 v 4 press near the wide area with no immediate passing outlets for the opposition. In this instance, Sabitzer’s press was successful as he tackled the ball off his mark before scoring about ten seconds later. The Austrian has had a stellar season for Leipzig in the midfield, and this match was no different.

With this level of invasion on the forward press, one common tactic often attempted against it is the long ball. Mainz, however, seemed to lack the urgency needed to succeed in this style of attack, and Leipzig’s backline were often resilient and disciplined in their tracking back. In the example below, Mainz attempt a long ball over the opposing backline, but the right-winger doesn’t push forward to join the attack in space. The left-winger and striker therefore are outnumbered in a 3 v 2, and Leipzig’s talented backline easily regain possession.

Leipzig were considerably successful on both sides of the ball, and their signature assertiveness on the press and adaptability in the backline were both present in this performance.

Mainz’s attacking struggles

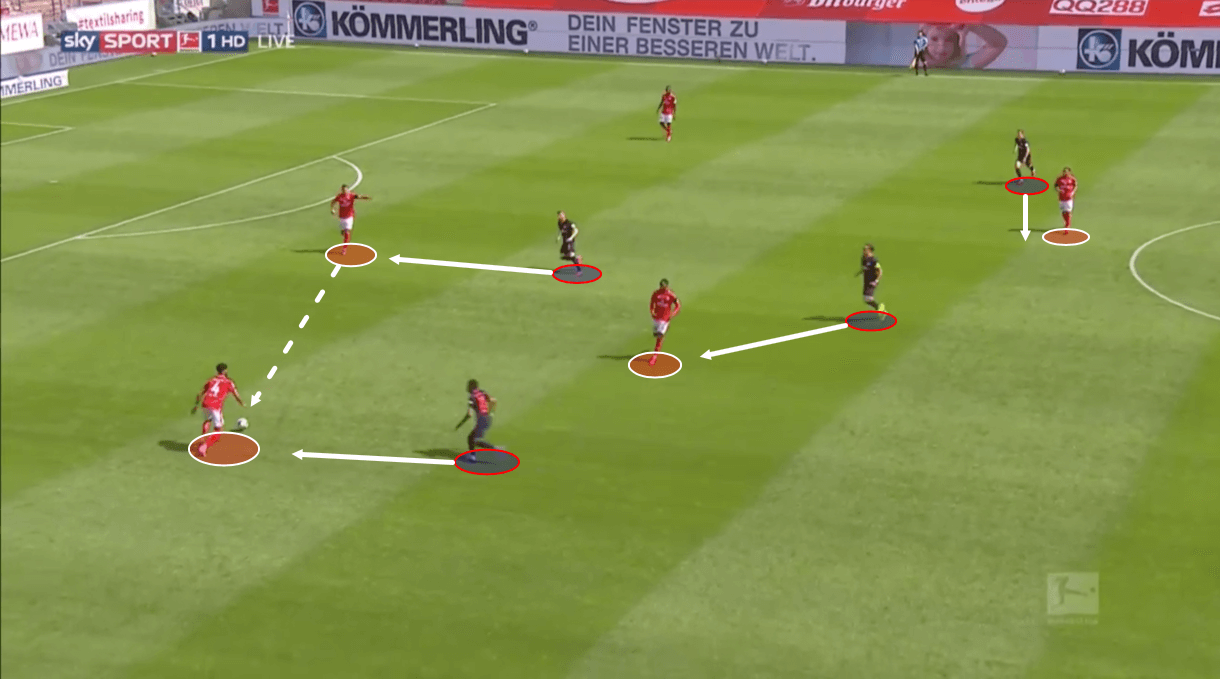

Mainz struggled in numerous areas of play during this match, including creating opportunities in attack. In possession, the 5-4-1 shifted into a 3-4-3, with the two wide midfielders moving forward to join the striker, and the two wing-backs doing the same to join the two central midfielders. Below is one of the few moments when Mainz were able to progress down the pitch. The centre-back completes a pass to the right wing-back, and a switch in position by the right wide midfielder and striker open a gap between Leipzig’s left-back and left centre-back for the striker to receive the ball in.

However, as was the case with this scenario, Mainz’s front line struggled to receive the ball in effective areas and stances. While the Mainz striker did find the space behind the opposing right-back in specific play above, he had turned his body to face the ball rather than opening up his hips to face the right touchline. As a result, he couldn’t turn smoothly to catch up with the through ball, and Leipzig keeper Péter Gulácsi calmly recovered the ball.

Another common issue for Mainz in their attacking linkup play was a lack of numerical superiority. Leipzig’s pace and discipline among their full-back-heavy back four prevented Mainz from gaining any quality chances in the final third. In the figure below, Leipzig’s press forces the ball to the Mainz wing-back Baku. The continued press successfully pushed the ball into a trap, which forced a long ball.

With the ball-side midfielder Fernandes moving closer to the ball in an attempt at providing a passing outlet against the press, the right-winger Boëtius shifted down into the space Fernandes vacated. This left the striker isolated against two centre-backs and the deeper opposing midfielder. The long ball pass, which was directed towards the striker, was easily intercepted.

Defensively, the hosts lacked organisation against Leipzig’s movements in the final third. As seen in the first section of this analysis, the amount of space allowed by the Mainz backline provided Leipzig with high-quality goalscoring opportunities. With the five goals allowed here they have now conceded the most goals in the Bundesliga with 60.

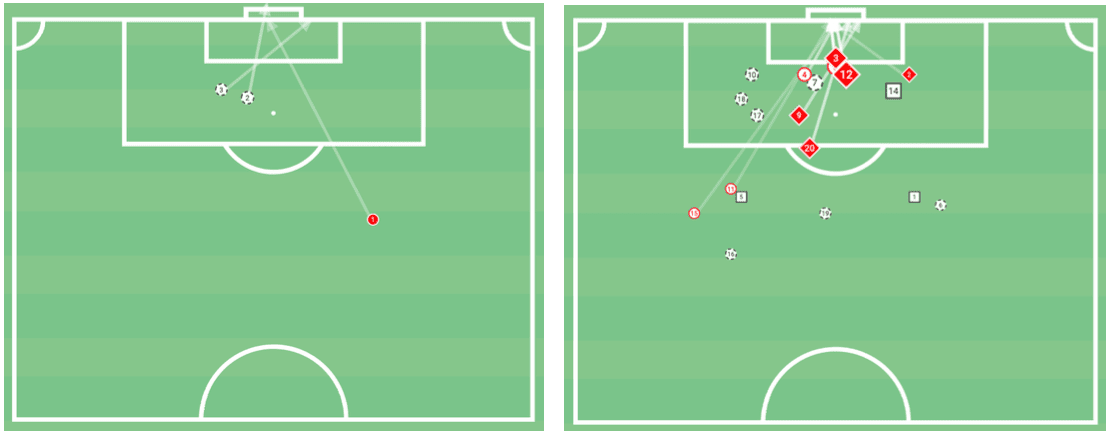

Lastly, the locations and frequencies displayed in the shot maps below (Mainz on the left, RB Leipzig on the right) along with an xG score of 0.23 to 3.30 accurately sum up the contest, with Leipzig scoring the highest expected goal value in the league this matchday.

Conclusion

Leipzig would ultimately score five goals in what was one of the more one-sided matchups of the Bundesliga season. Werner tallied his second hat trick against Mainz this season, moving up to only three goals behind Bayern Munich striker Robert Lewandowski in the race for the Bundesliga golden boot.

Nagelsmann’s side executed their game model to a tee, with both the primary pressing and attacking tactics functioning beautifully. They will look to continue this level of success through the seven matches remaining on the season, as they face only one of the top eight clubs (Borussia Dortmund). Mainz, on the other hand, stand only three points away from the relegation playoff spot but face a Union Berlin side next who have lost both of their matches since the league’s return and failed to score in both.

Comments