Sunday’s Bundesliga game between Schalke and Bayer Leverkusen promised to be a tight tactical battle and a matchup that both teams prefer. Schalke, a dogged pressing side who rely on transitions to start attacks, came up against a possession-based Leverkusen side who usually thrive against teams who allow them time to break them down, and the matchup lived up to its tactical profile. Schalke were compact, disciplined, and pressed well in the game against a Leverkusen side who lacked their usual offensive structure and movement, and as a result, it was Schalke who will have been happier with a 1-1 draw. These kinds of games are always extremely interesting to analyse and are often easier to break down into the simple aspect of attack against defence. Therefore, this tactical analysis will focus on Leverkusen’s positional play and how Schalke’s structure and pressing was able to frustrate it and crowd it out.

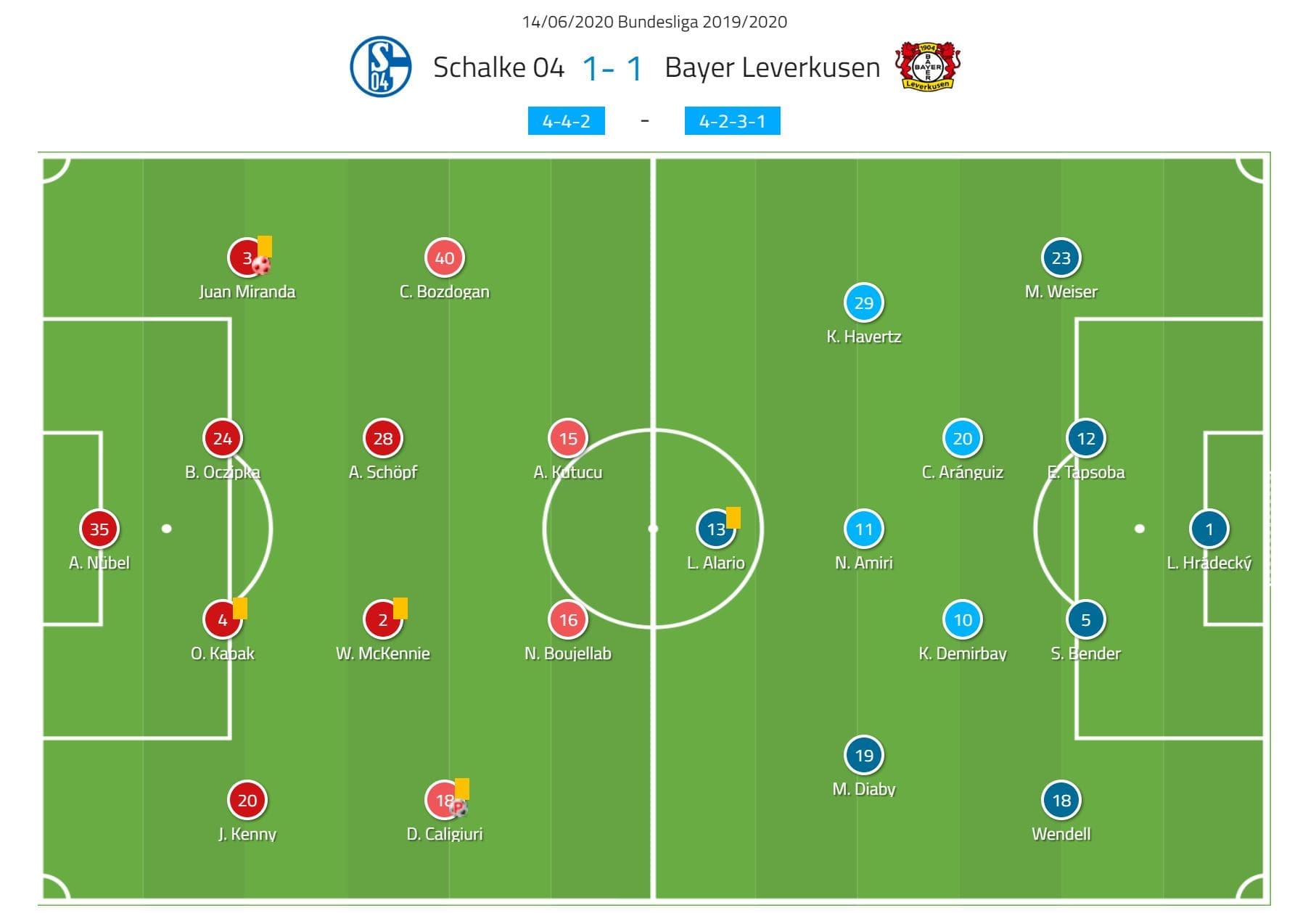

Lineups

Schalke lined up in their usual 4-4-2 structure, with again the intent to frustrate and crowd out any Bayer Leverkusen positional attacks. Schalke were without a number of key players, and so Bastian Oczipka slotted into the centre back role, while youngster Can Bozdogan made his debut. Ahmed Kutucu made his long-awaited start also. Leverkusen on paper adopted a 4-2-3-1 but in reality in the first half used a back three, with Wendell dropping in and Moussa Diaby becoming a wing-back, which is something I will cover in this analysis.

Schalke’s well-coordinated press

The overall dynamic of the game can be summed up well in the stats seen below, with Leverkusen dominating possession and looking to break down a Schalke side who looked to counter with quick attacks. Leverkusen had long possession phases, even eleven lasting over 45 seconds, and despite this, they rarely got the better of Schalke’s press. This then begs the question of how was Schalke’s press so effective?

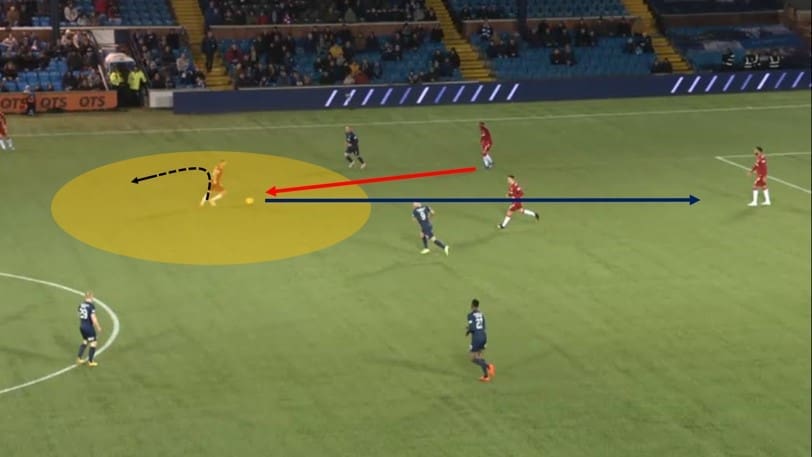

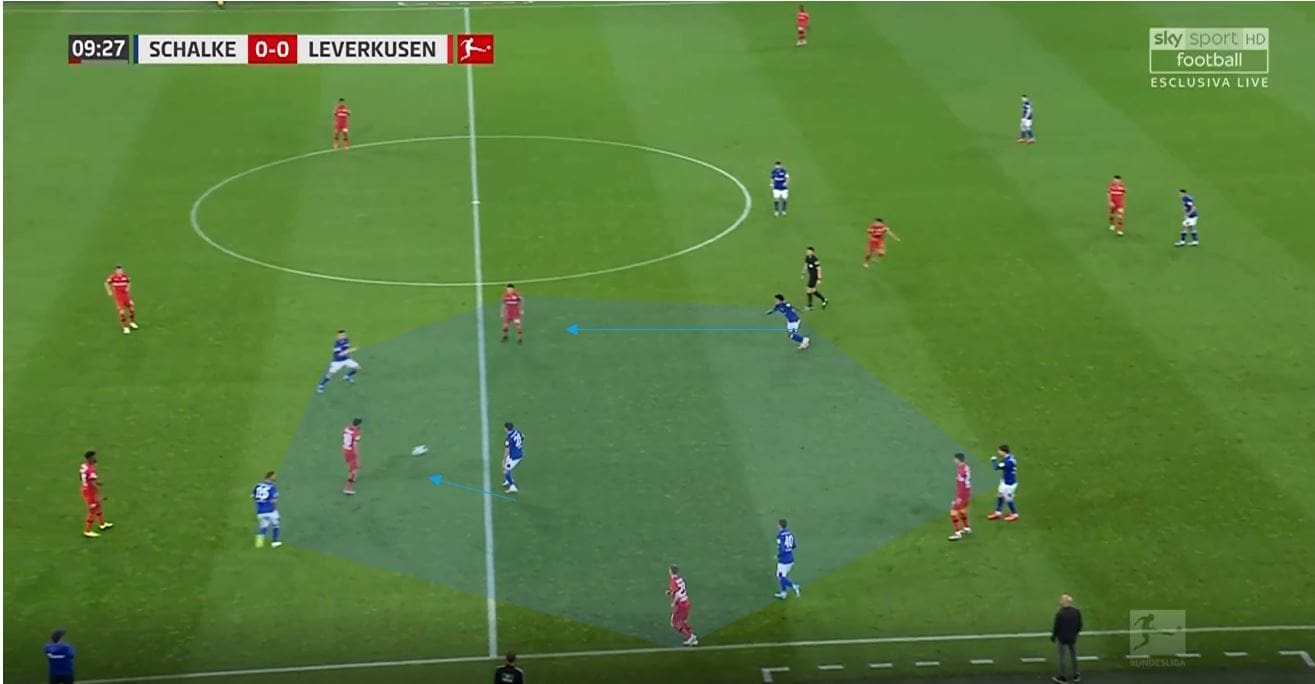

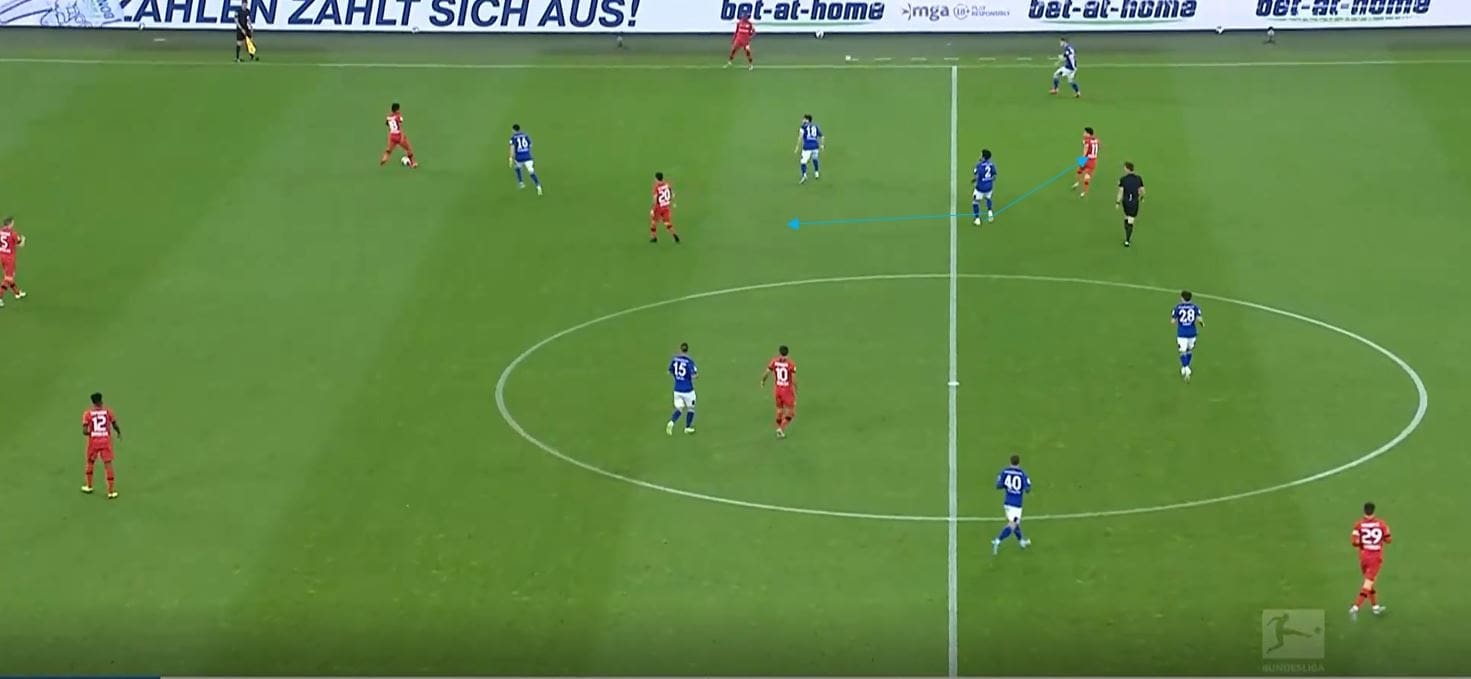

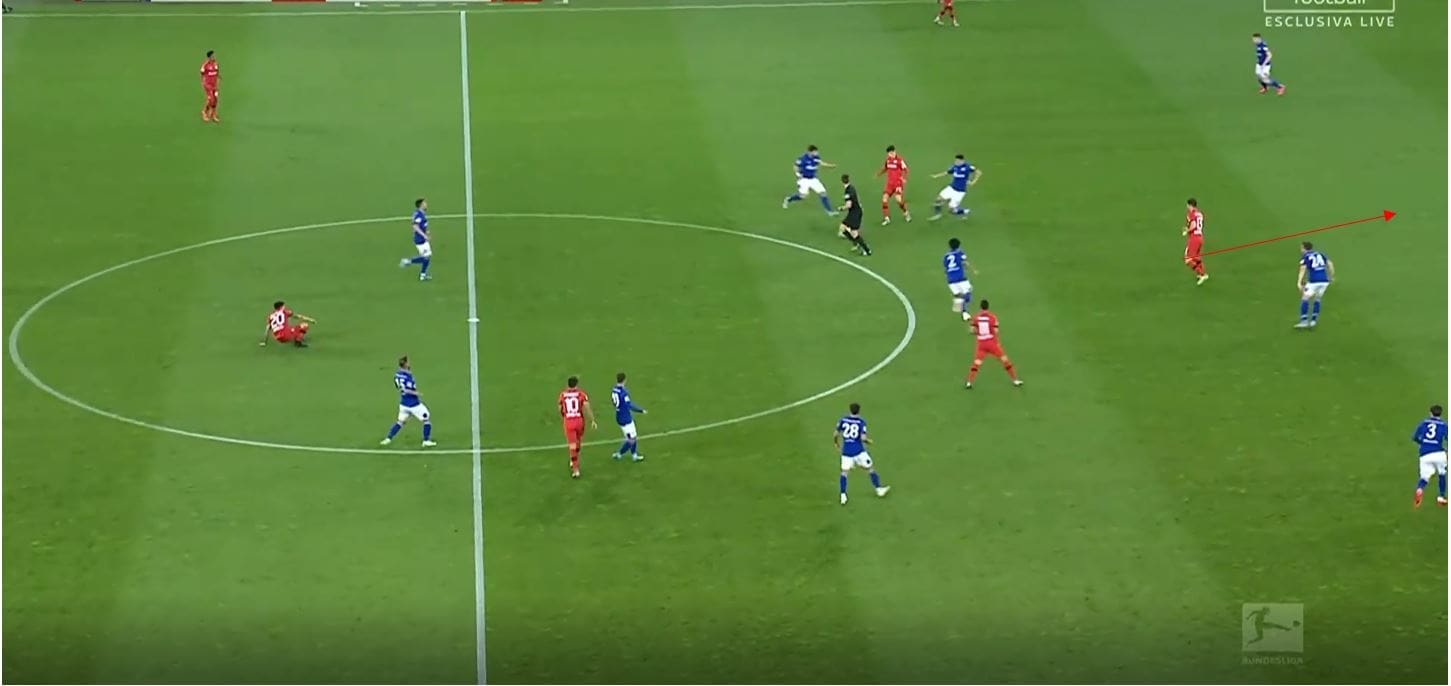

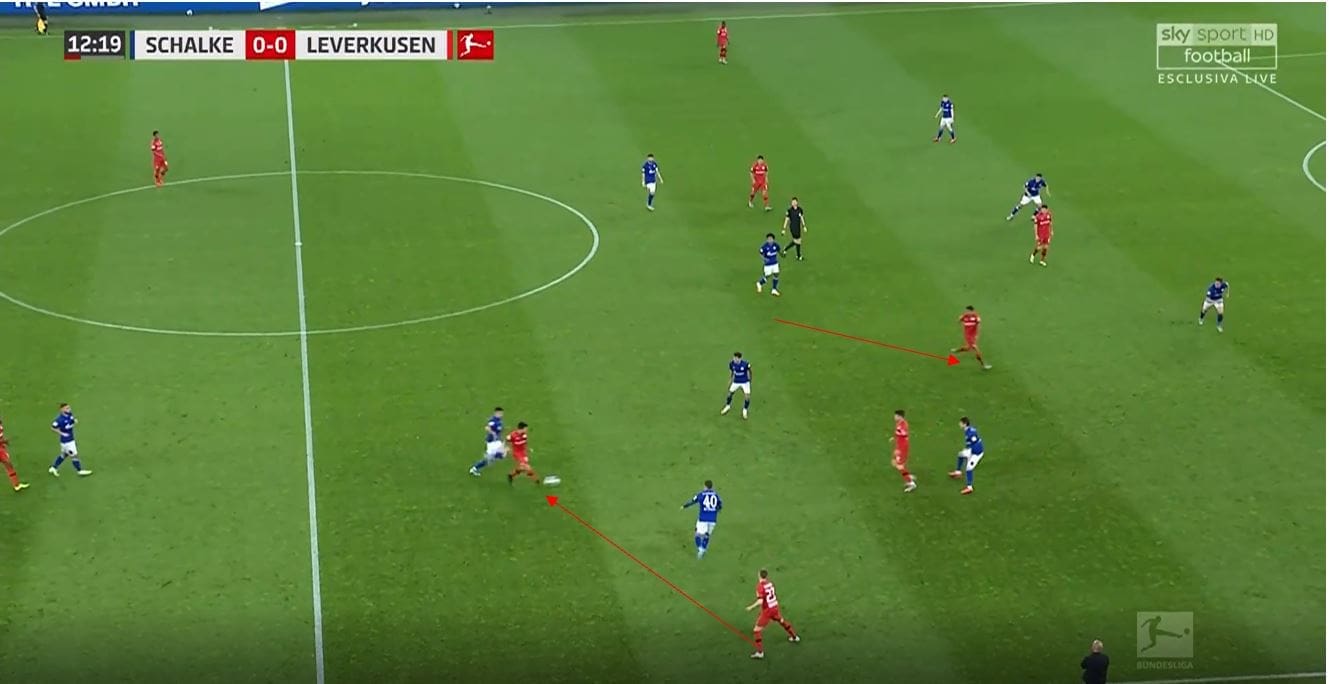

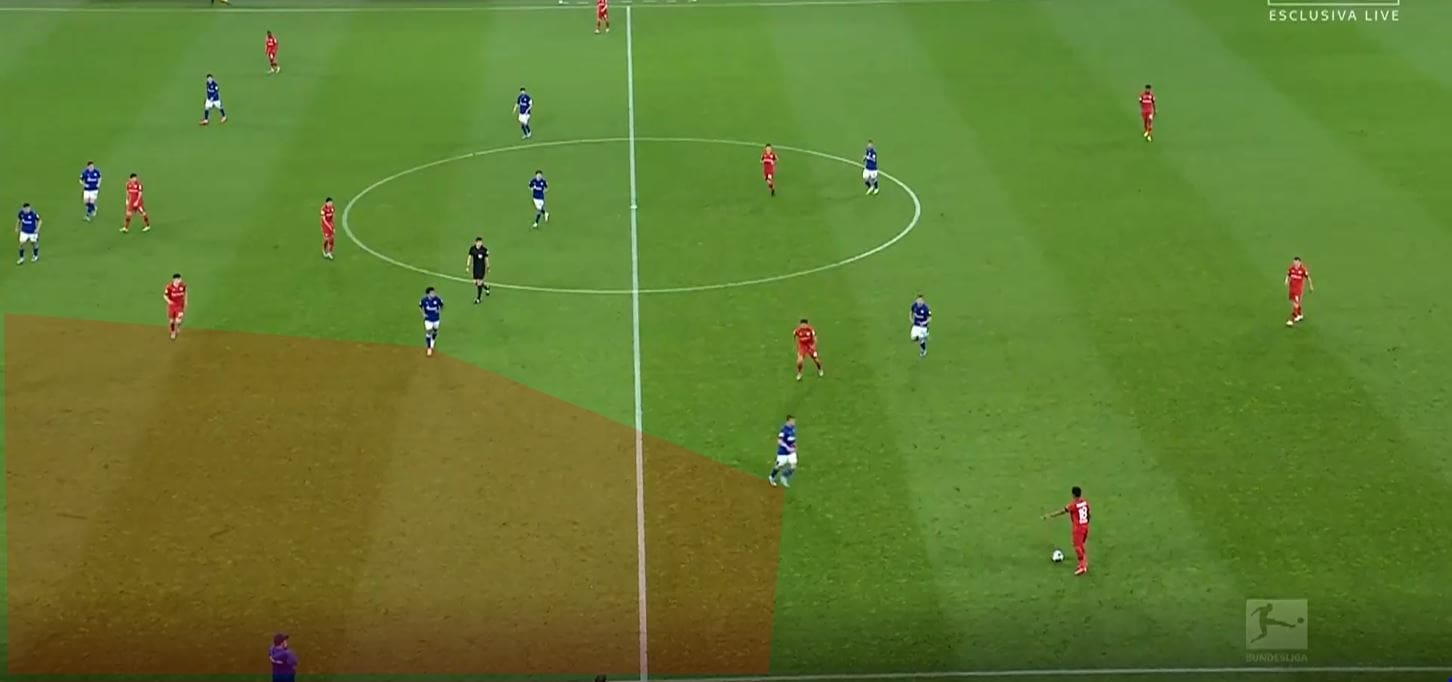

This sequence of play showcases Schalke’s press well and highlights the roles players had within the press. As stated, Schalke pressed in a 4-4-2, but when Leverkusen held a back three, this would situationally jump to a 4-3-3, with the winger jumping to press the wide centre back if they could not be covered by the strikers.

When the ball is forced back to the other side, the striker applies pressure to the wide centre back, while Leverkusen’s wing-back is left in more space. Schalke’s wingers looked as though they were instructed to close the half-space and prioritise this area over the wings. We can see here the midfielder stays much more centrally and allows the wide pass, where Schalke are then able to press well.

When the wing-back receives, the Leverkusen midfielders drop from their markers to receive, but Schalke were quick to follow and did so in an efficient manner. We can see the two Schalke central midfielders press Leverkusen’s, with Weston McKennie here staying slightly deeper, which allows him to protect a pass in behind. Schalke are able to form a compact shape around this area and as a result, are able to win the ball here through McKennie. We can also observe Leverkusen looking to make an overload, something we will talk about shortly.

In this example, we see again the Leverkusen midfielder able to receive the ball, before pressure is applied and nearby markers are cut off. We can see the far striker is also able to join in and aid the press, which is something else I’ll discuss.

This final example in this section highlights the role the Schalke wingers played, with Daniel Caligiuri here remaining very narrow and falls for the feint of Tapsoba, who fakes to play the ball leading to Caligiuri opting to protect the half-space. Schalke did an excellent job of shifting across to deal with the wide player when they received, but Mitchell Weiser was poor both in terms of his ability to receive and carry the ball in these areas, but also in his passing ability. The german completed only 53% of his forward passes in the game.

Leverkusen’s build-up and response to the press

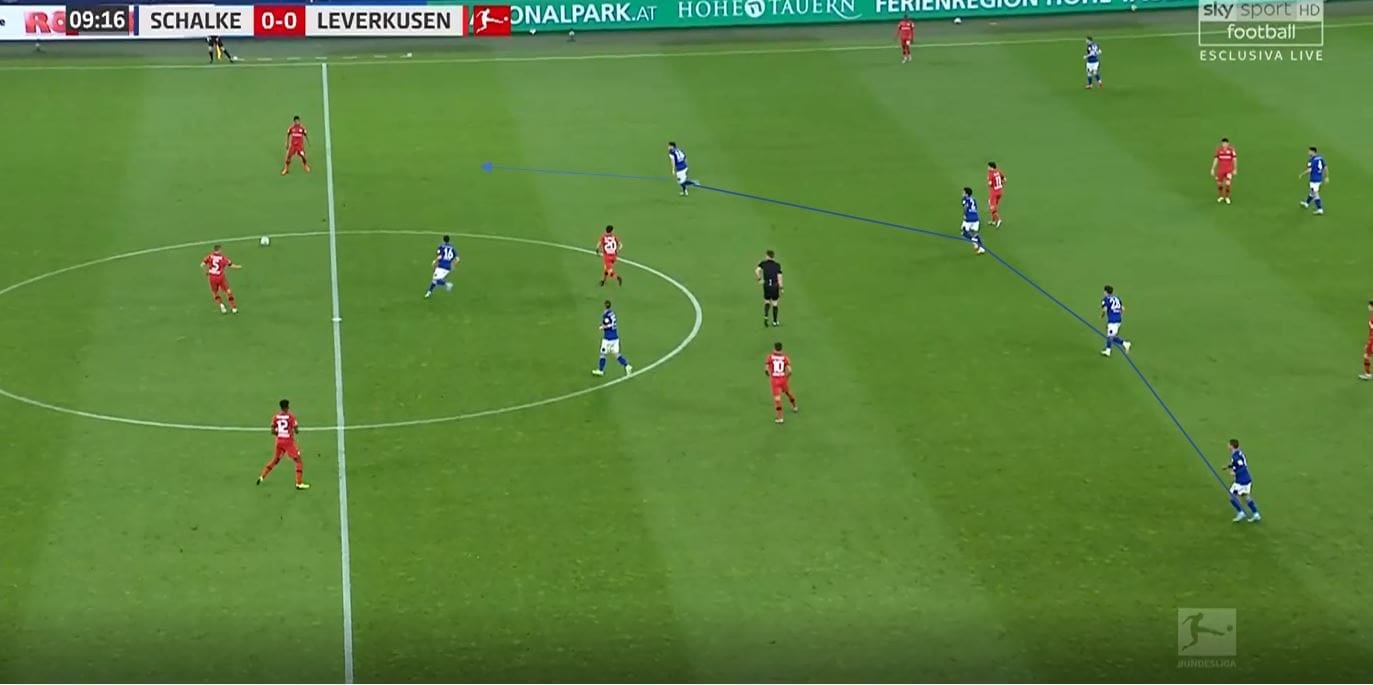

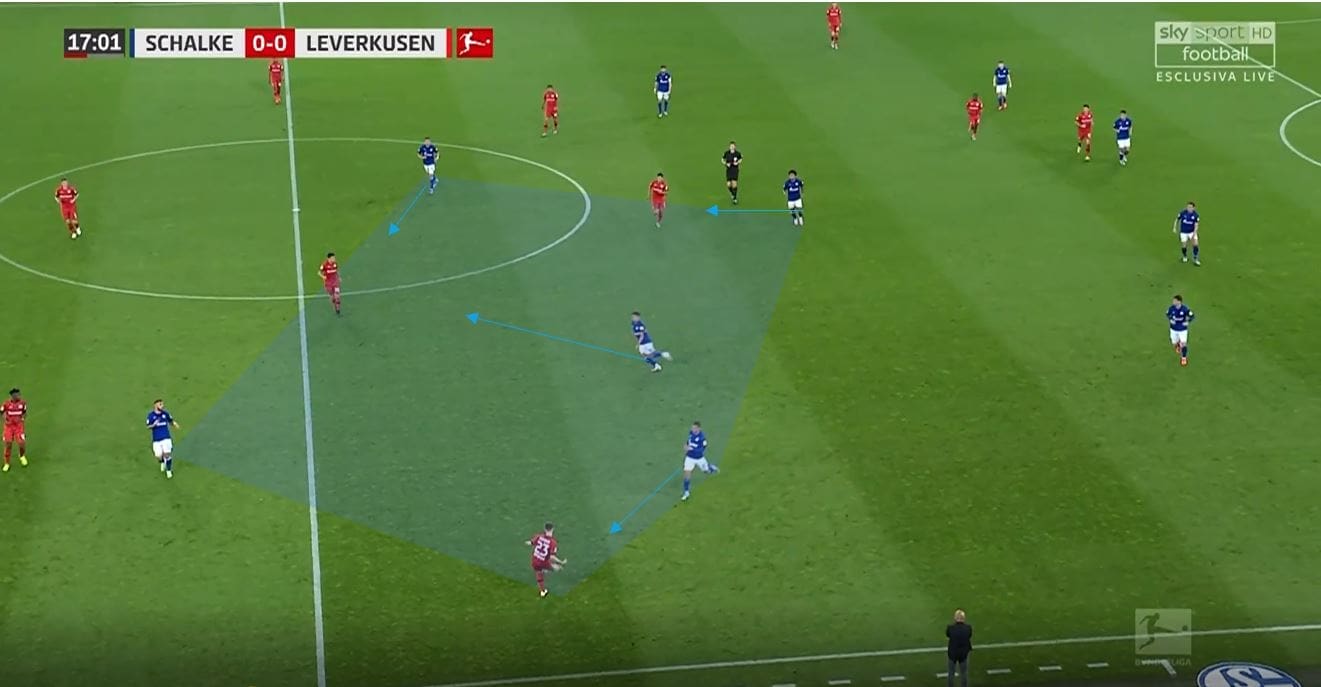

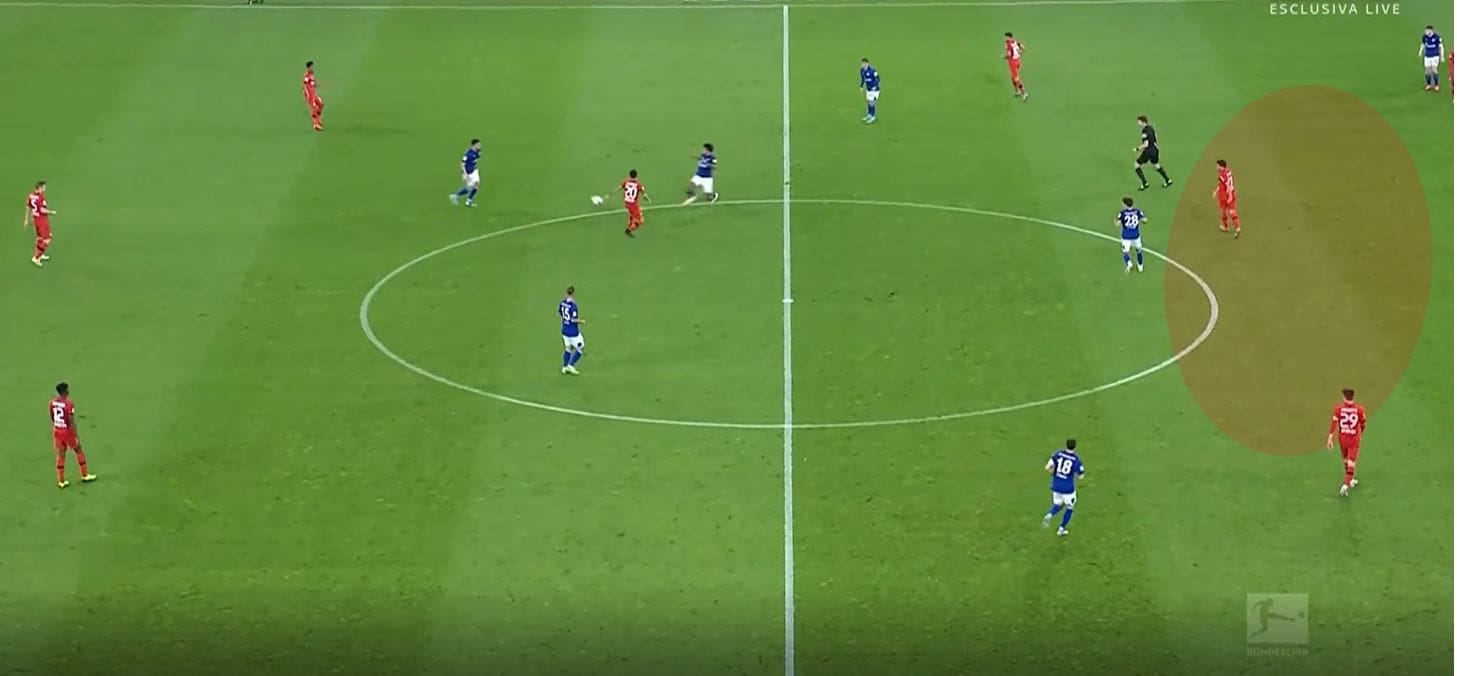

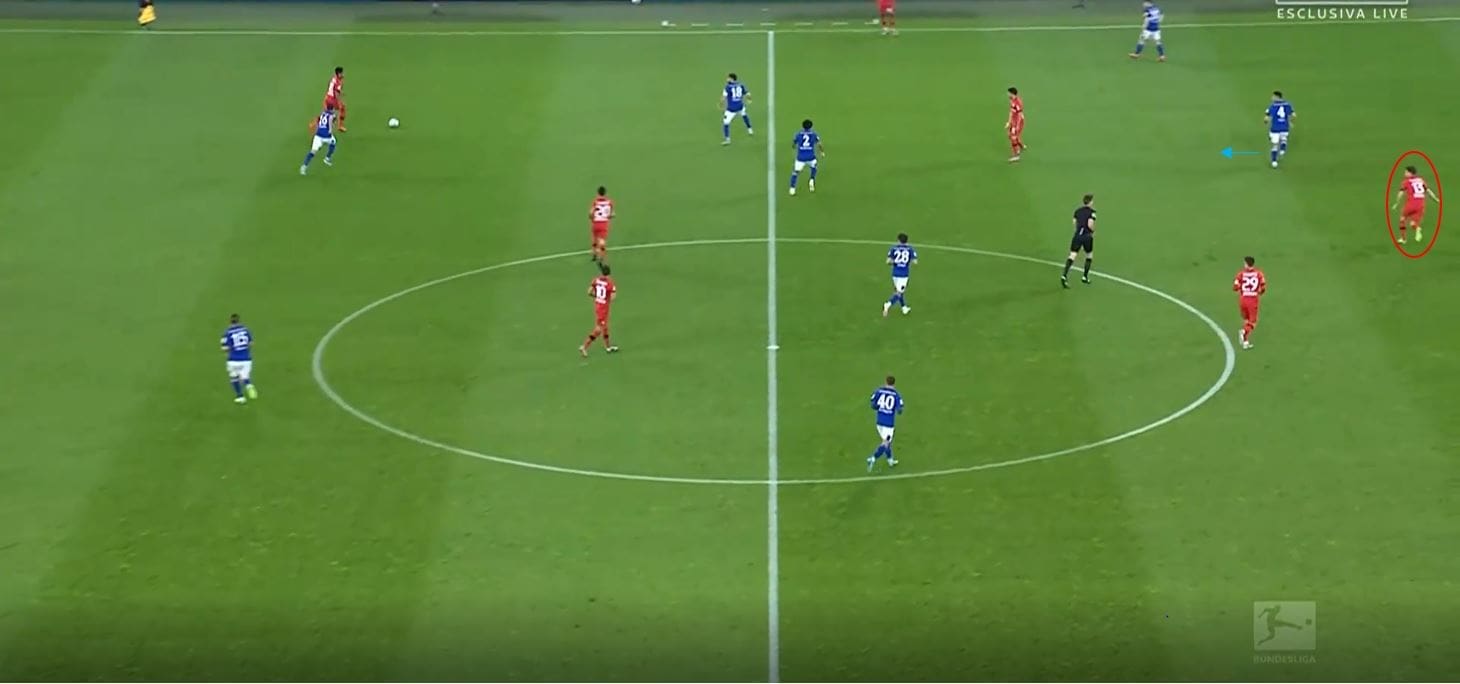

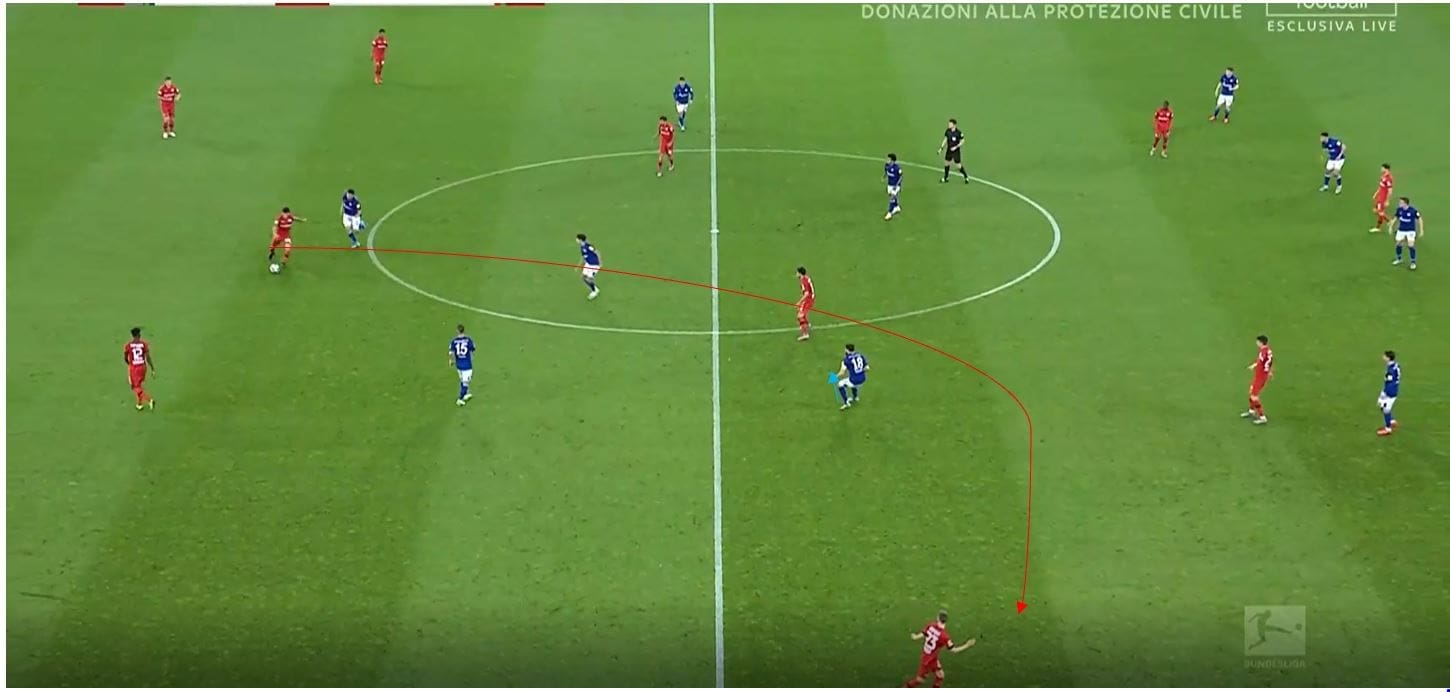

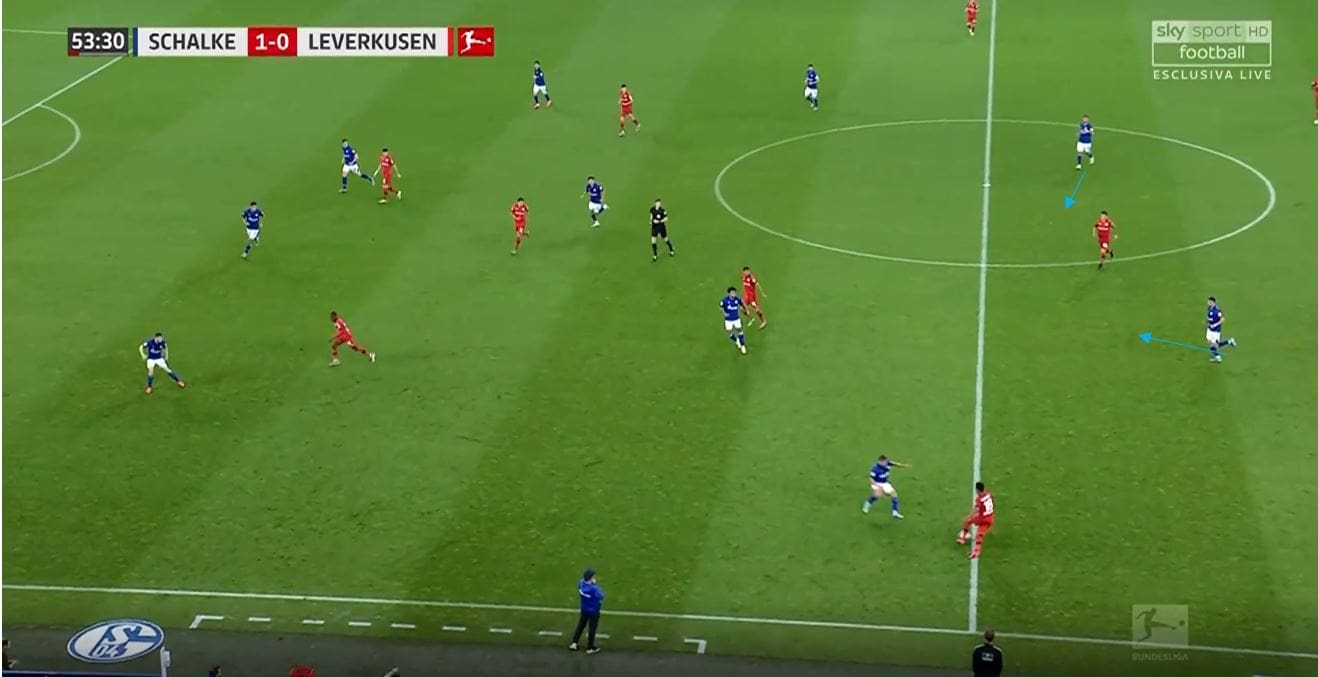

As I’ve mentioned and as you can see in the previous examples, Leverkusen built up in a 3-4-3 for the first half. Therefore the method that could be used to penetrate Schalke initially seemed to be through the creation of overloads in the half-space, something Borussia Dortmund and many other teams use often. This is something Leverkusen have done in games recently too against teams such as Freiburg, but they were generally poor in this regard against Schalke. We can see below how one overload could be created in the half-space against Schalke’s 4-4-2. The nearest central midfielder moves off his marker and looks to find the inside forward occupying the half-space. The opposite inside forward then comes across to overload the half-space, and the striker stays high looking to run in behind.

We can see the basic premise of this overload below, with an inside forward and central midfielder occupying the Schalke central midfielder from two directions. Schalke are able to adjust well here though, with the nearest striker able to press the centre back, preventing the midfielder from having to jump to press. This allows for them to stay to protect the half-space, and here Jonjoe Kenny steps up to press. Weston McKennie is then able to focus more on the player behind him, with the Schalke winger able to cut off the pass centrally.

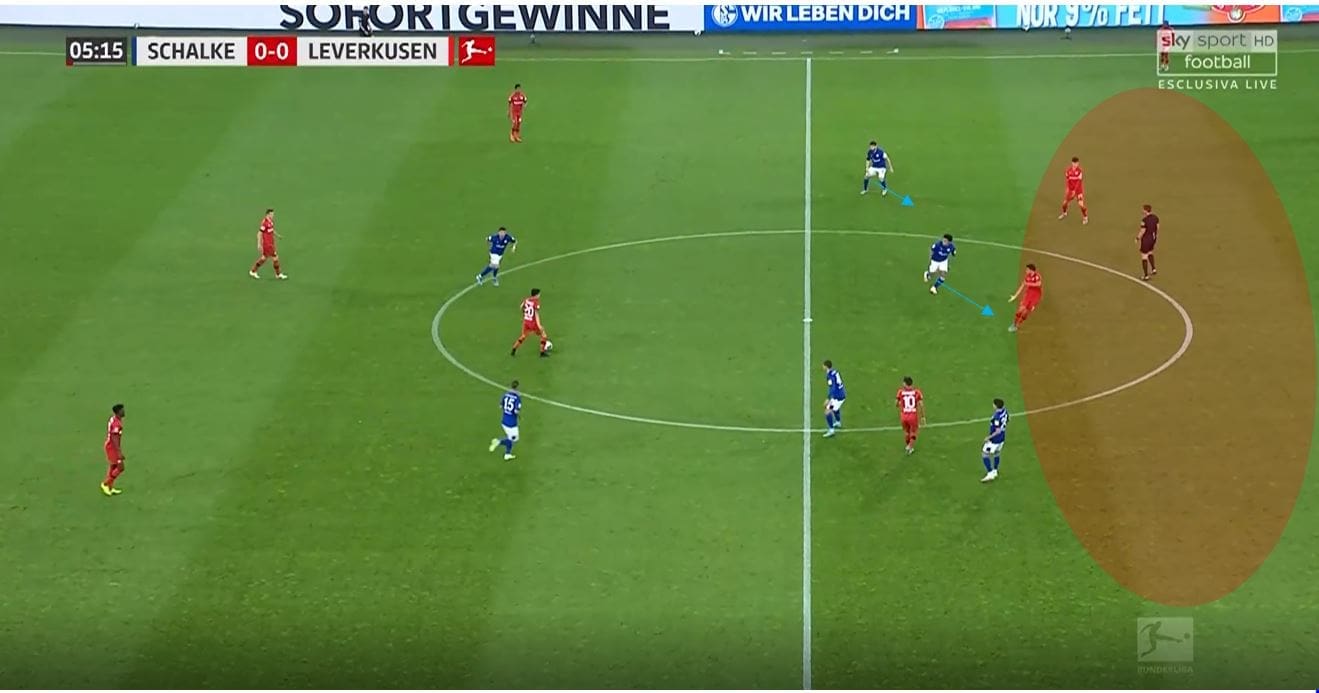

We can see the effect of Leverkusen’s positioning on McKennie here, with the midfielder stepping out to press the Leverkusen midfielder and just missing the ball. This forces the other central midfielder of Schalke to press, leaving players free behind the lines. This deeper positioning of Charles Aránguiz draws the press from McKennie, and this was something Leverkusen tried to use often with little success.

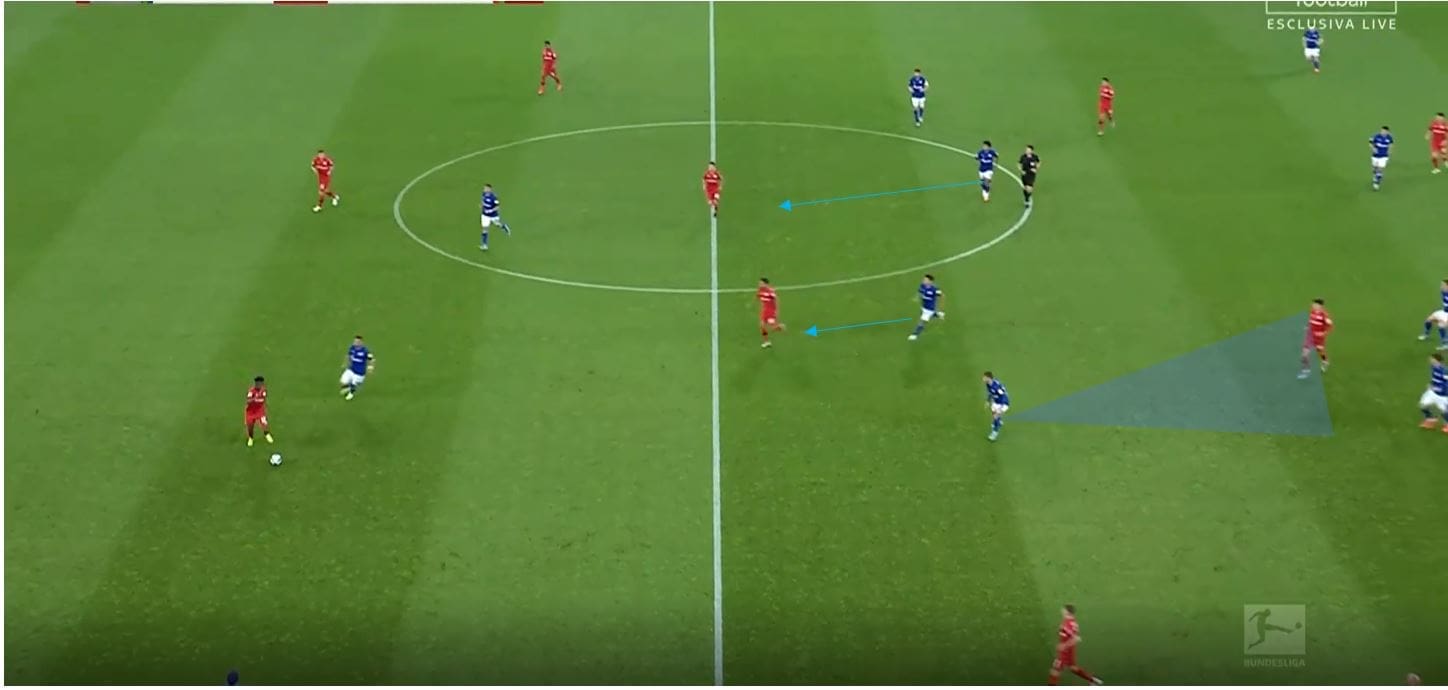

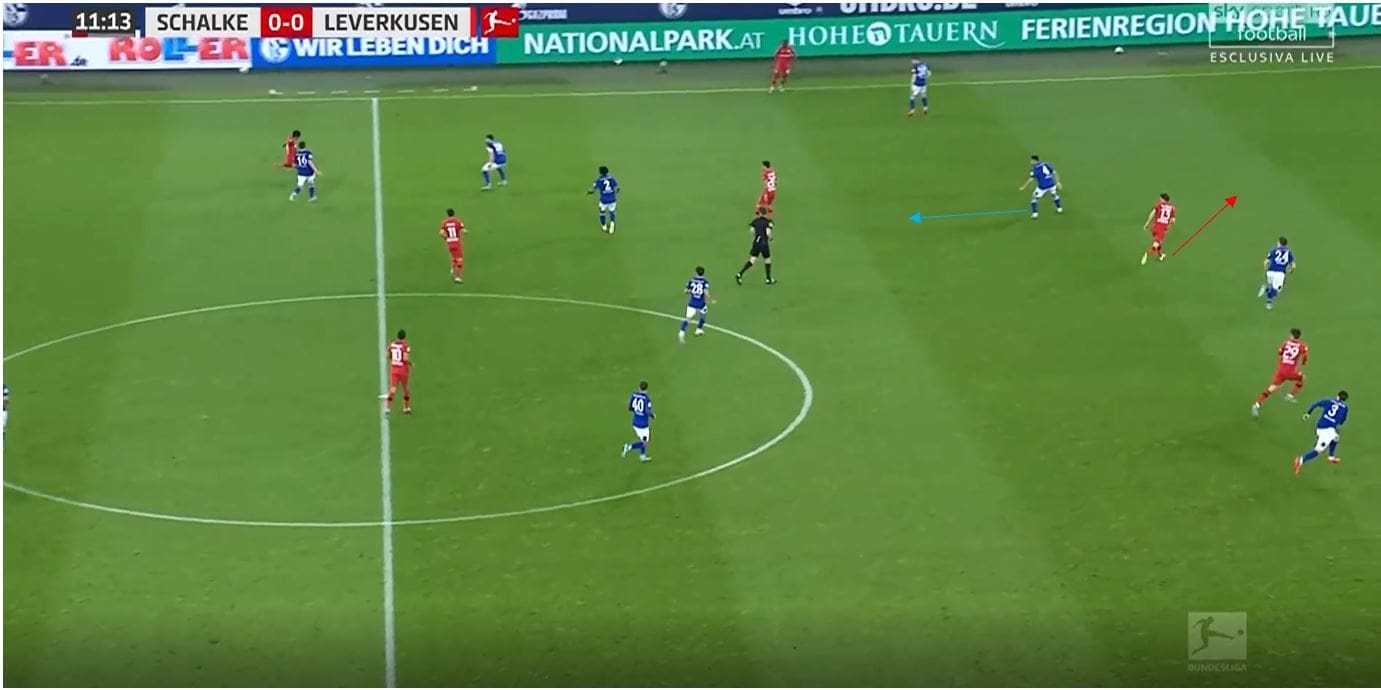

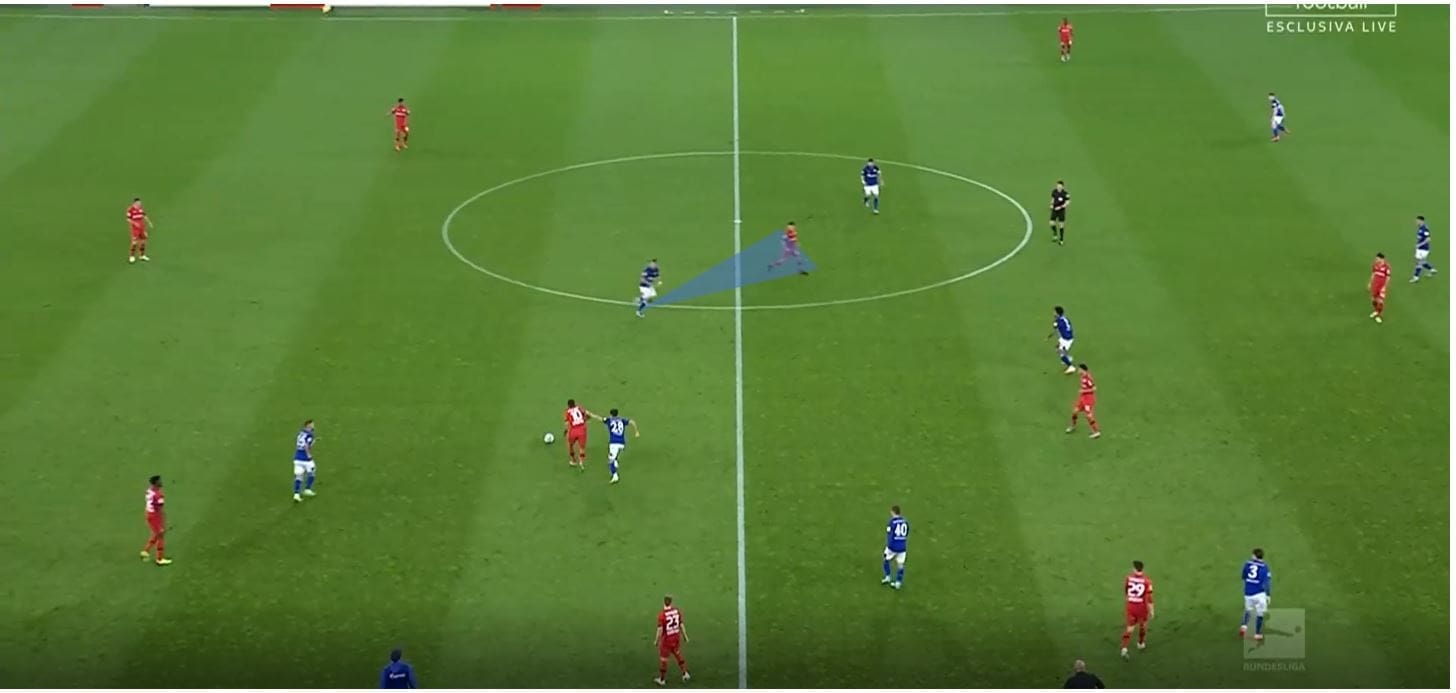

We can see Aránguiz helping to overcome the first line again here, with the Chilean dropping deeper to escape a press by a Schalke central midfielder. Leverkusen then drop players deeper and in the pockets between the second line, and as a result, they create space for each other. Amiri and Haveertz create an overload either side of McKennie, and Amiri’s run opens space for Havertz to receive. Again though, in the few opportunities Leverkusen created such as this, they were generally poor and seemed to struggle technically on the day.

Leverkusen struggle to penetrate

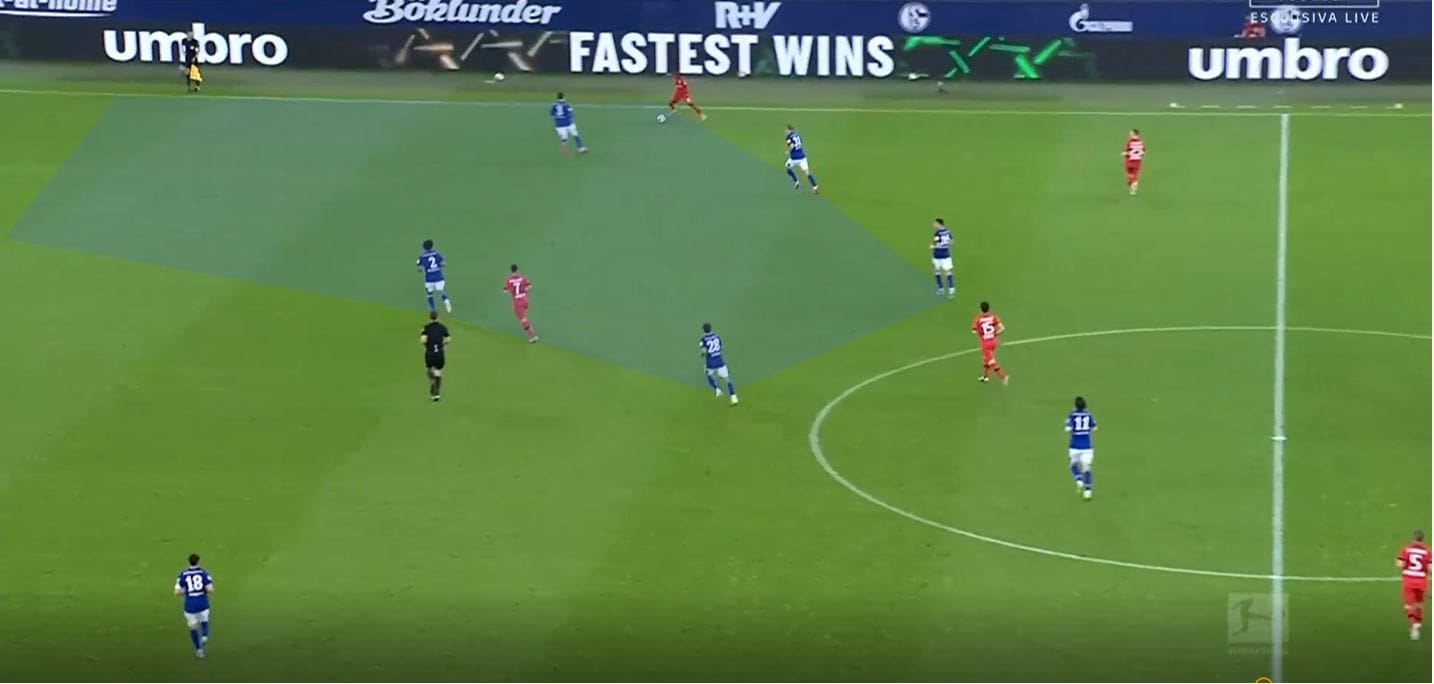

Aránguiz again drops deeper here, but Leverkusen’s offensive structure hinders itself. Demirbay here basically gets in the way of Havertz, not just physically but also through his positioning. Demirbay here could be used to pin the central midfielder in a more central area, which would help to open the space for Havertz. Both players instead occupy the same passing lane and make it easier for Schalke to stay compact, which Schalke should also be given credit for.

If Leverkusen were going to squeeze the ball through to one of the inside forwards, they would then likely be pressed by a central defender of Schalke, which is something most sides would be uncomfortable with. However, the offensive side only possesses the ability to take advantage of this if they have height in their team’s shape, which is something Leverkusen missed throughout the game. Here Havertz receives but is pressured from behind and is in a compact space. Havertz has the ability to receive and flick the ball round in behind, but Lucas Alario doesn’t help and doesn’t provide height nor does he provide support laterally. As a result, Schalke can deal with the attack. If Alario does receive here I’m not sure what his next move is.

Because of this potential threat, positioning a player deep in the half-space offers the opportunity to draw a press from the central defender, or at the very least occupy them to cause them to forget about the space in behind. Here Leverkusen do just that, and Alario looks to get in behind. However, the timing of his run isn’t good and he is caught offside. Alario is not the quickest and so at times, it is like he compensates for this by running earlier. Perhaps a pacier player would have been more effective earlier on. We can also see in this image that structure from Schalke again, with the winger protecting the half-space and the full-back wider.

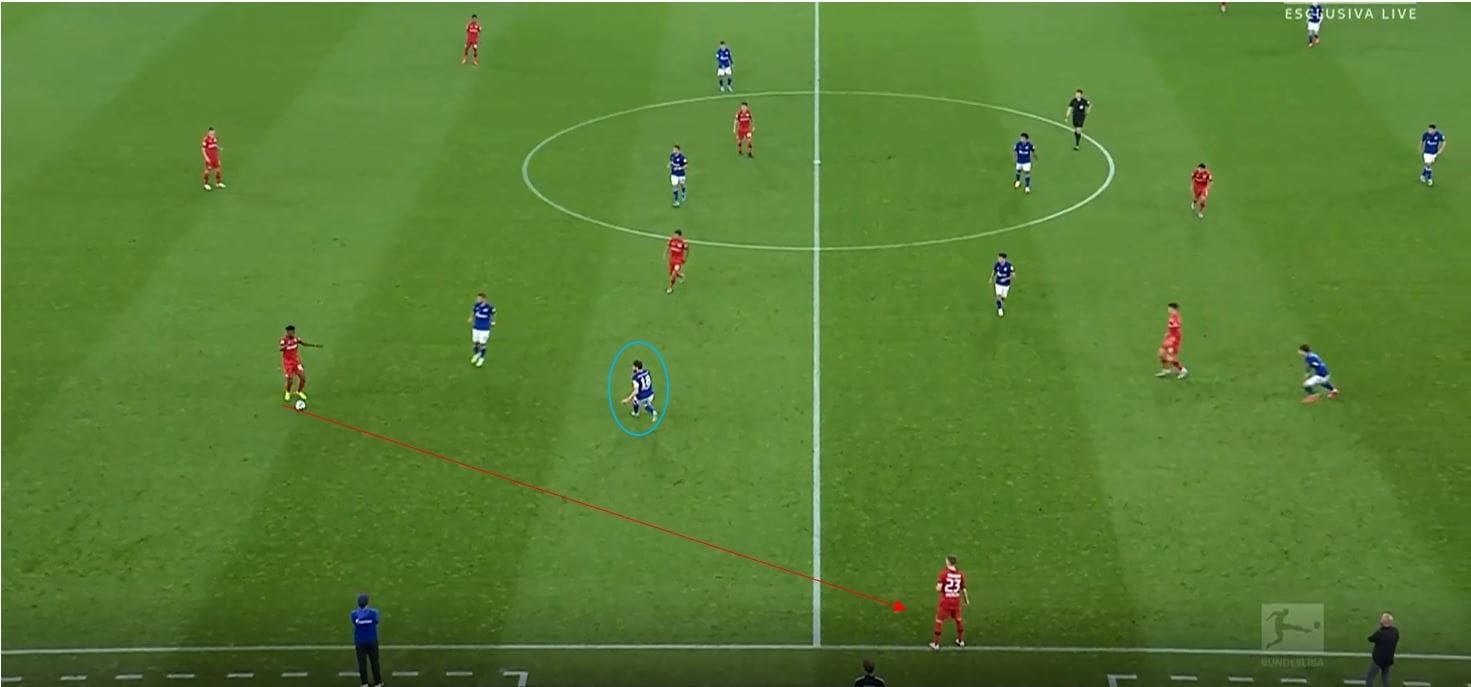

Here we see the same idea again, with Alario looking to get in behind again. However again I don’t think this is his biggest strength and the longer pass is ultimately a more risky one. The main issue I have with this, however, is the positioning of Moussa Diaby at left wing-back, and why he has positioned himself so close to Kenny. Here, if he is able to drop to receive, he can play into the half-space and Leverkusen can access Alario in behind in a much more precise manner. Leverkusen instead go long and the pass isn’t accurate.

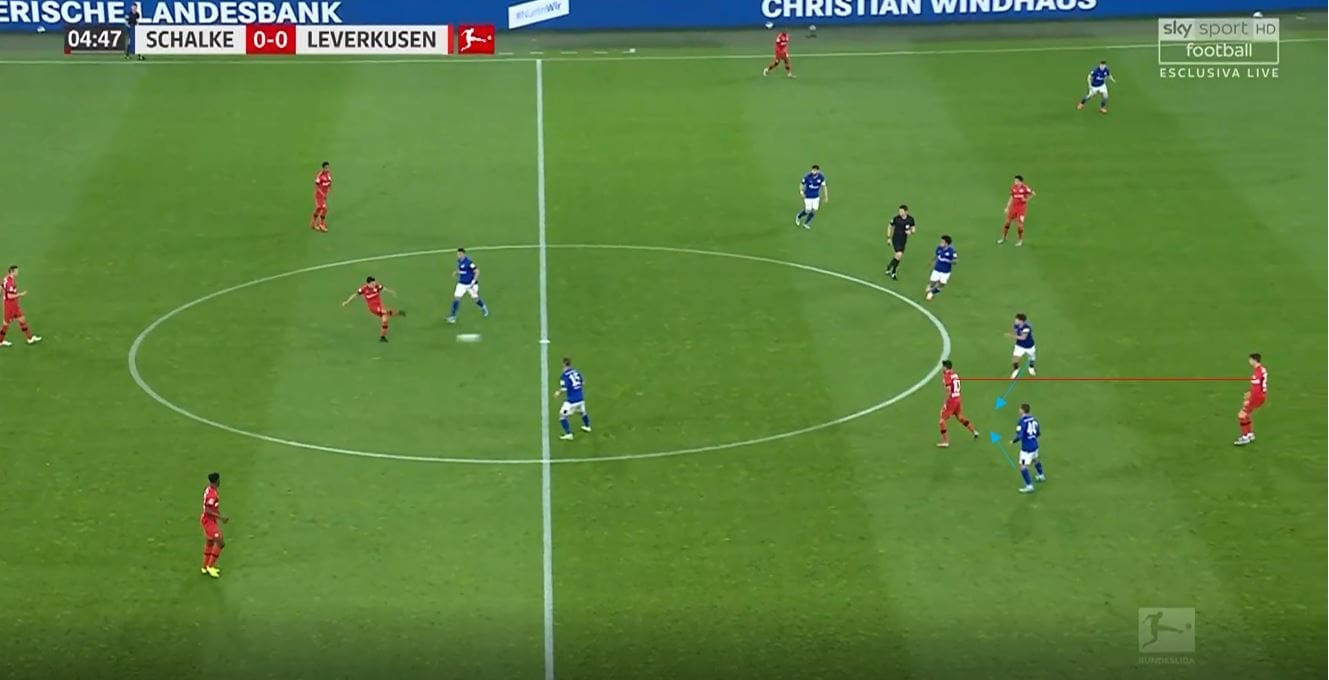

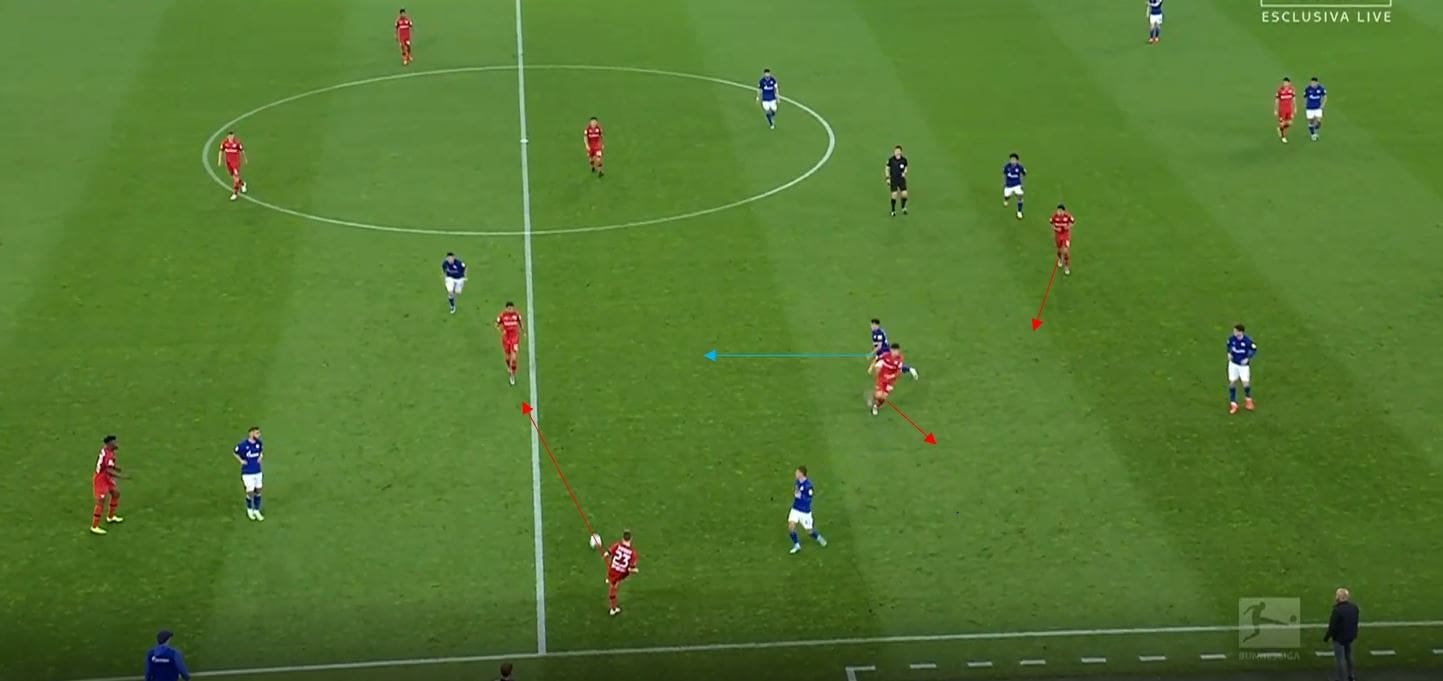

At times though, Leverkusen did show some signs of improvement, but again these moments were too few. Here we see a nicer combination, with the inside forward (Havertz) initally occupying a central midfielder and pinning them in place, allowing the Leverkusen central midfielder to receive. Once the pass is played to the central midfielder, Havertz moves off this player and onto the full-back. This creates an angle for him to receive a pass from the midfielder, and support is then provided by the other inside forward. A very similar idea to the overload I mentioned earlier in the article. Alario again though doesn’t offer much in terms of support and Leverkusen are forced to go back across to the other side.

We can see a nice overload created again here, with the wing-back receiving and playing the ball to the deeper central midfielder Aránguiz. The other central midfielder Demirbay moves from deep and creates a passing lane to receive, with Havertz’s positioning helping him also.

Due to the narrowness of Schalke’s wingers, there were also opportunities for longer passes into wide areas, which is something Leverkusen could have used more I felt. We can see an example here where Caligiuri is drawn into a central position, and the ball is played longer to Mitchell Weiser out wide. Leverkusen then immediately have players in high areas, but again sloppy technique lets them down.

Schalke’s press adjust slightly

If we look at the examples above when the ball is possessed by the wing-back, you can see one trend which started to become more prevalent as the game went on, due to Schalke becoming naturally deeper.

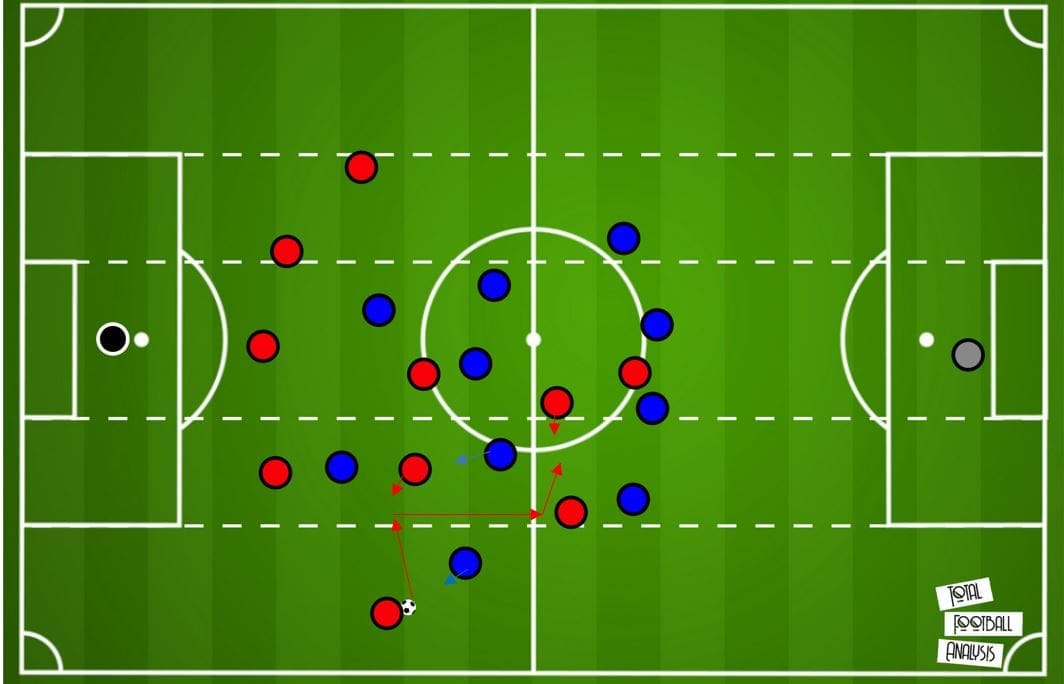

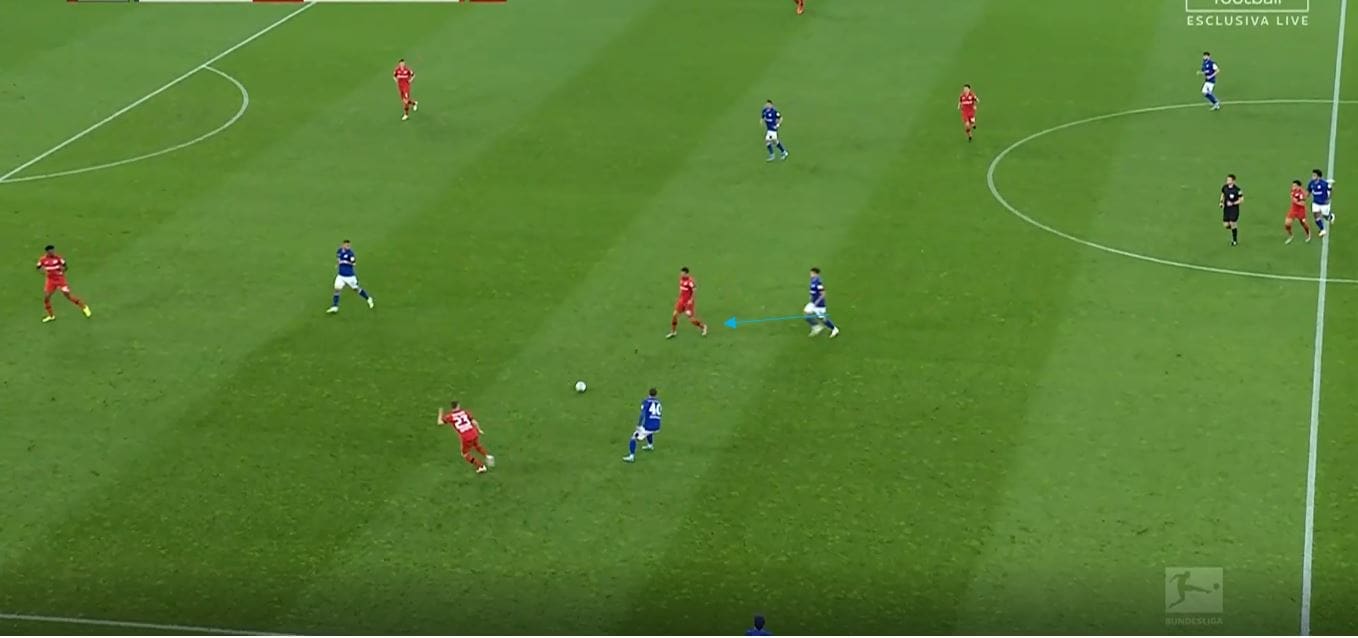

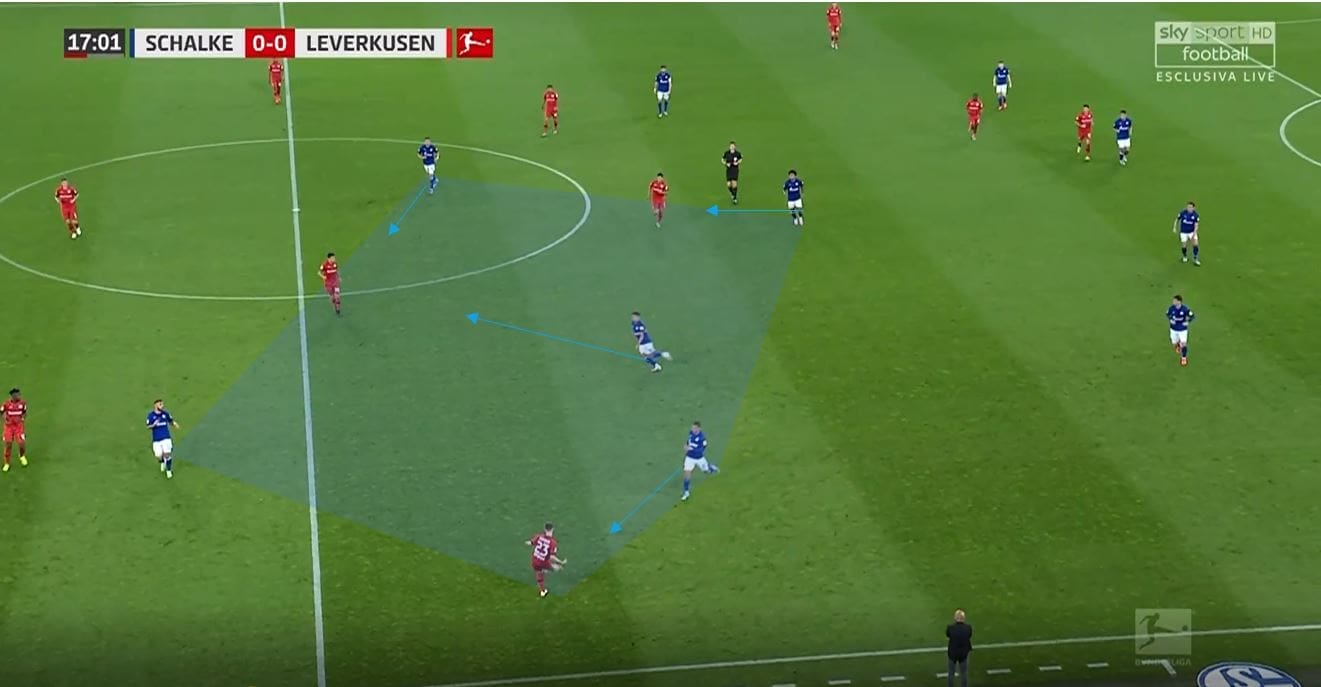

Instead of always relying on the central midfielders to press Leverkusen’s central midfielders, Schalke adjusted their press slightly and used the far striker to press a deeper central midfielder. We can see this occurring below with the far striker following the deeper pivot. This allows the central midfielders to focus on one player and therefore cancels any overload.

Here, the central midfielder moves out to press the deeper central midfielder, but the far striker is still able to help cancel the overload, this time keeping the far central midfielder in his cover shadow while pressing. This allows McKennie to only have to focus on one player. For more examples of this, look back through my analysis as there are some examples of this in other points.

Leverkusen’s switch to a back four

In the second half, Leverkusen seemed to adopt a back four more often, with Wendell acting as full-back. This helped them to get players forward but didn’t improve their ability to progress the ball cleanly, and there offensive structure and spacing was still pretty poor. This example of them in a 2-4-4 from the first half illustrates how it became much easier for Schalke to deal with Leverkusen in this formation.

With no method of progressing the ball cleanly, they were easier to press and mark most of the time, and their offensive players became isolated often. We can see an example here with Wendell on the ball and no width provided by any players. The player in the half-space becomes isolated and Leverkusen can’t progress the ball. This would be a perfect opportunity to drop into a back three and allow the wing-back to push forward and provide width.

In this example minutes later that is exactly what they do, and they find themselves able to progress the ball. Wendell moves higher while a central midfielder takes up the role of a wide centre back. Again though, in the second half Leverkusen seemed happier to rely on isolated players dribbling at their markers.

Here is a good overview of Leverkusen’s second half structure, which again shows how isolated players became in positions, with Leverkusen struggling to create overloads in any areas as a result of their lack of movement and poor structure.

Here is a good example of what Leverkusen instead relied on, with Moussa Diaby completely isolated and forced to dribble and cross. Leverkusen did eventually score on the second phase of one of these crosses, and it was a more direct style of play, but Leverkusen just weren’t their usual self and can so often be patient enough to find a way through with their positional play. Ultimately had it not been for a very unlucky handball, Leverkusen could have won the game.

Conclusion

Schalke, probably for the first time in a few weeks, deserved points from the fixture, as they pressed intelligently and managed to limit Leverkusen fairly well to 1.52 xG despite having only 28% possession, while also managing 1.09 xG, albeit with 0.76 of that coming from the penalty. As is the case in these kinds of games, for the offensive side, the failure to win is solely placed on them, as no matter the defensive set up and tactics, in sustained periods of possession there are always methods of penetrating. It is ultimately a case of choosing which methods apply to which situations and applying them with good technical ability, which is easier said than done against compact defensive sides.

Comments