Werder Bremen, attempting to build momentum off of their recent 0-0 draw with Borussia Mönchengladbach, took on Schalke 04 in the Bundesliga on Saturday. Both clubs were desperately in need of a win: Schalke were looking to avoid their fourth straight defeat and Werder are still locked in a relegation battle at the moment. Ultimately, Werder were able to earn all three points after taking advantage of an unorganised Schalke, earning themselves a 1-0 win.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics that both managers used in their matchup. The analysis will explore the advantages both teams tried to build, and how Werder was ultimately more successful at doing so throughout the match.

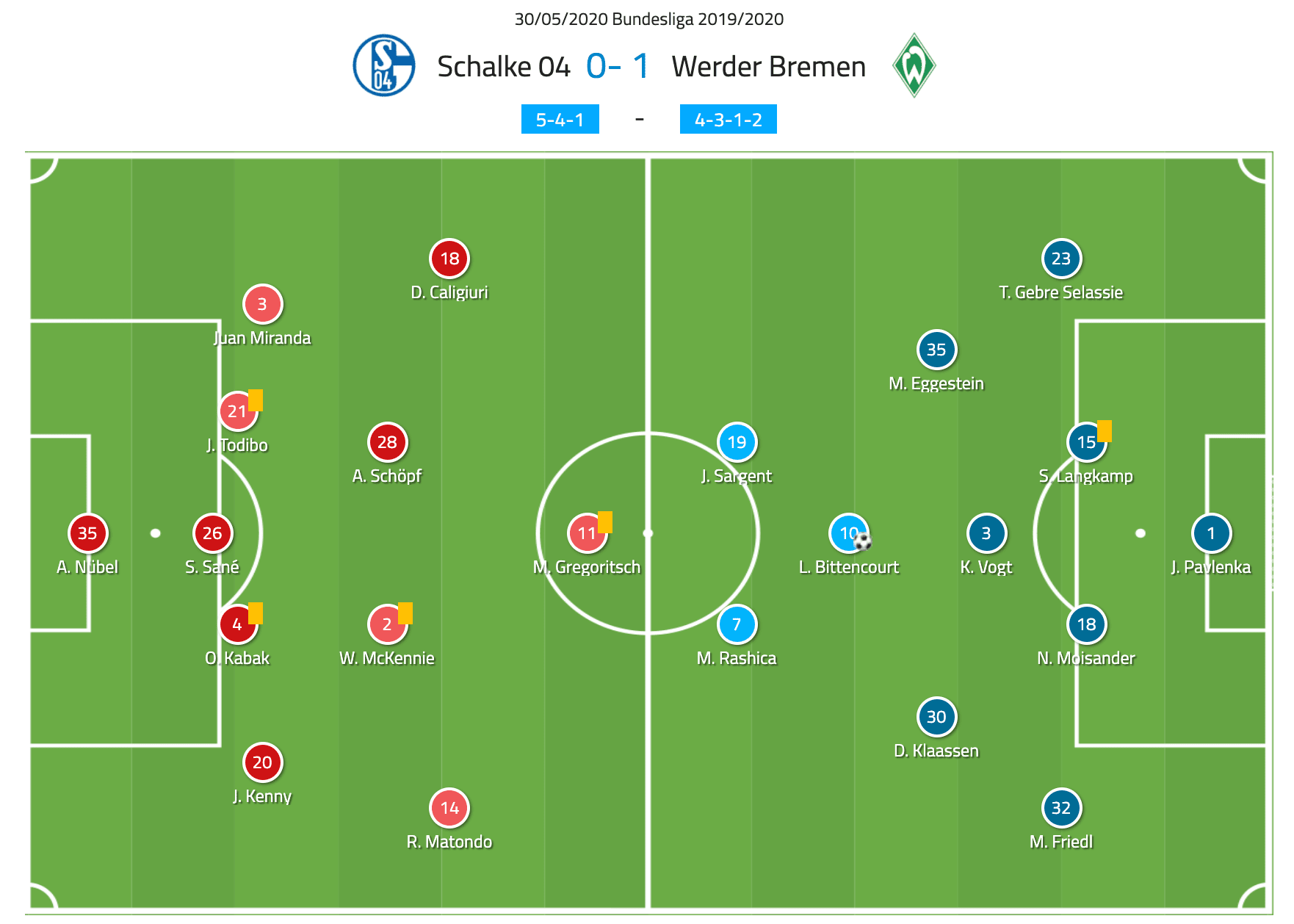

Lineups

David Wagner sent Schalke out in a 5-4-1 formation with Alexander Nübel in goal. Juan Miranda and Jonjoe Kenny were the outside-backs, with Jean-Clair Todibo, Salif Sané, and Ozan Muhammed Kabak playing as the central defenders. The four men in front of them consisted of Daniel Caligiuri, Alessandro Schöpf, Weston McKennie, and Rabbi Matondo, with Caligiuri and Matondo playing on the wings. Michael Gregoritsch functioned as the lone striker on the day.

Florian Kohfeldt sent Werder out in a 4-3-1-2, with Jiří Pavlenka in goal. Niklas Moisander and Sebastian Langkamp were the centre-backs with Theodor Gebre Selassie as the right-back and Marco Friedl as the left-back. The three men in front of them consisted of Maximilian Eggestein, Kevin Vogt and Davy Klaassen, with Vogt in the more central role. Leonardo Bittencourt was behind the two strikers, Milot Rashica and Josh Sargent.

Werder overload centre of pitch

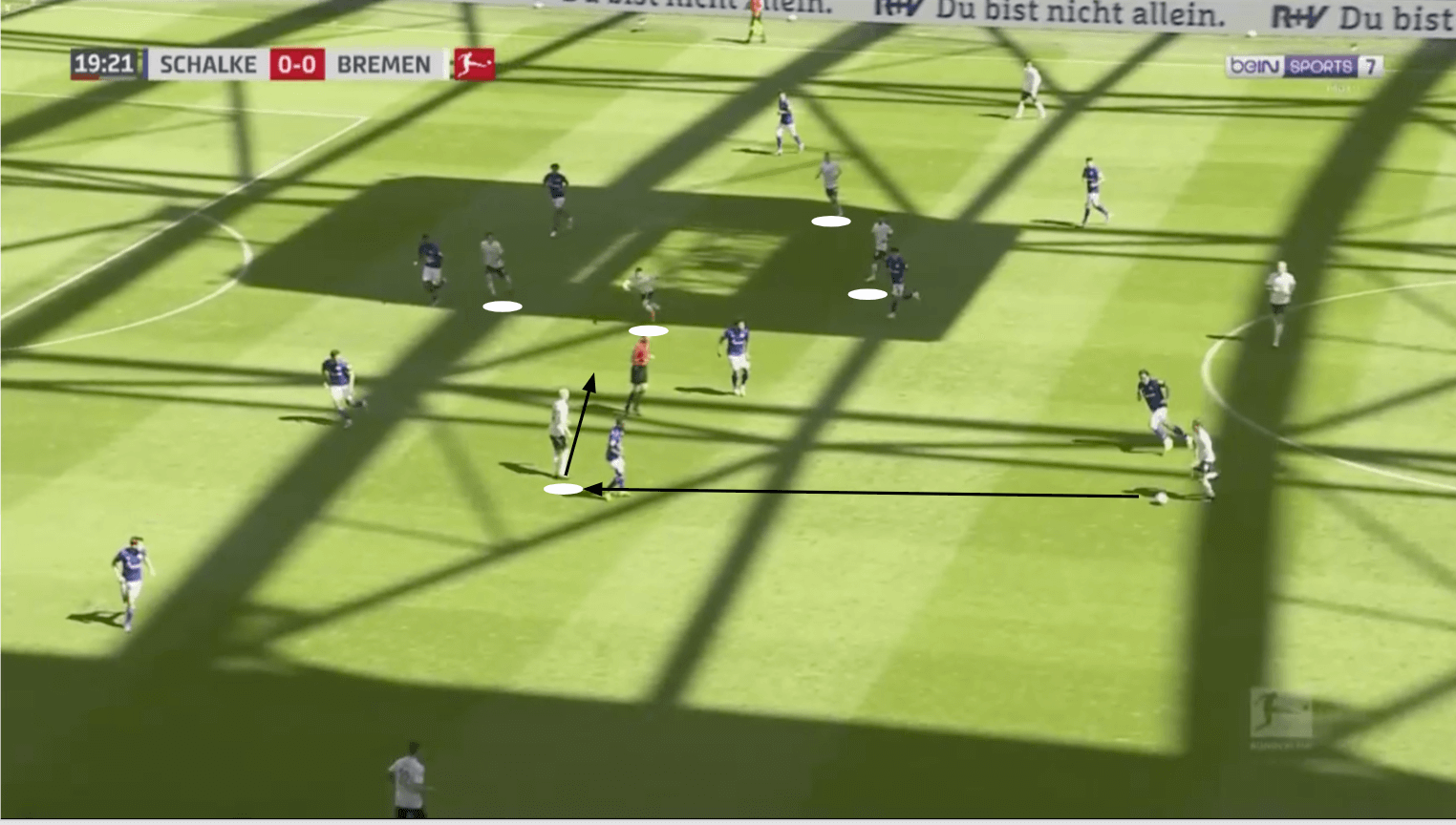

For the majority of the first half, but especially the first 15-20 minutes, Werder absolutely dominated possession, with 82% of it compared to Schalke’s 18%. This led to a more compact Schalke, who were seemingly happy to sit back and defend. One of the ways in which Werder attempted to play through Schalke was by overloading the centre of the pitch.

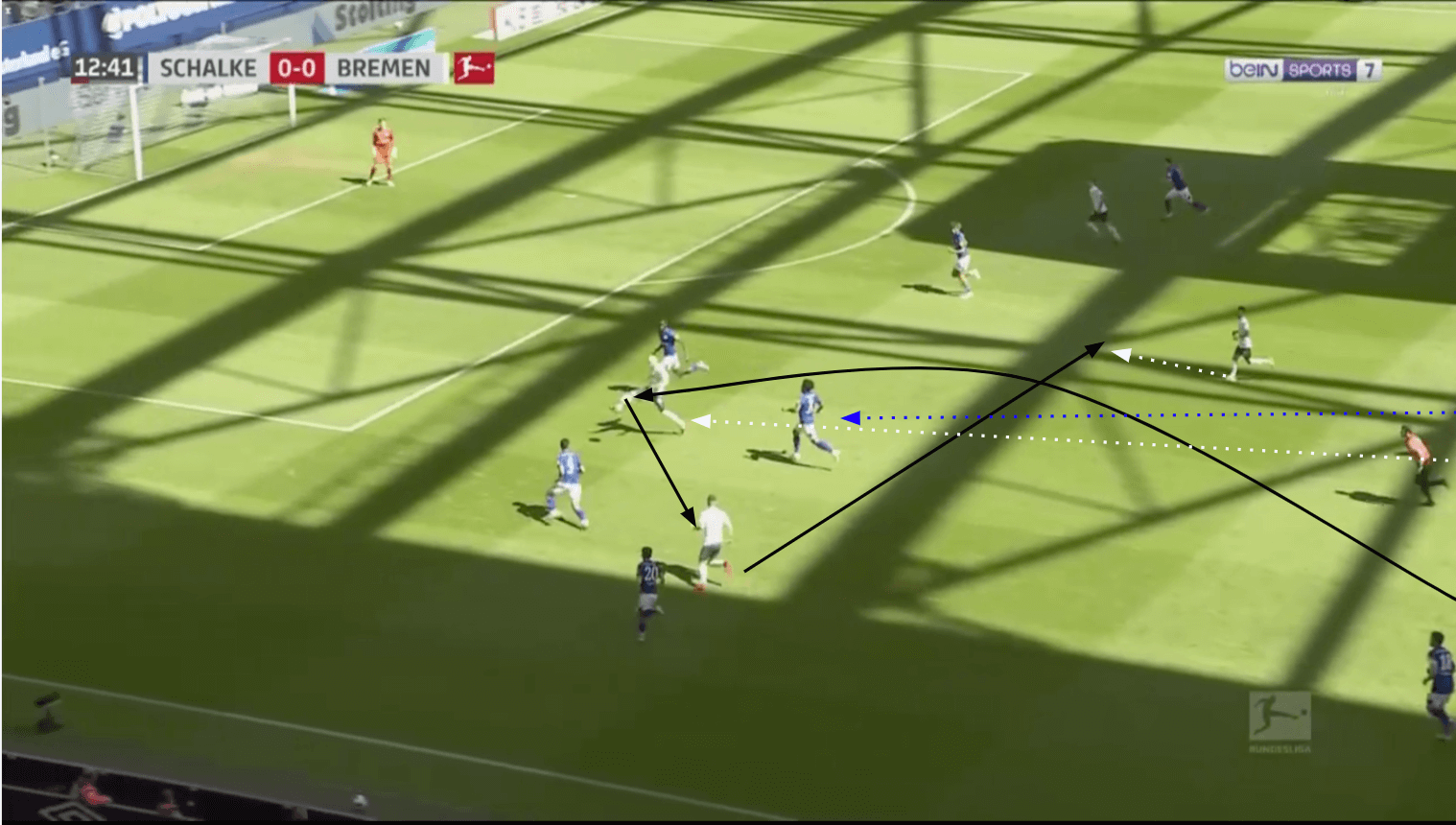

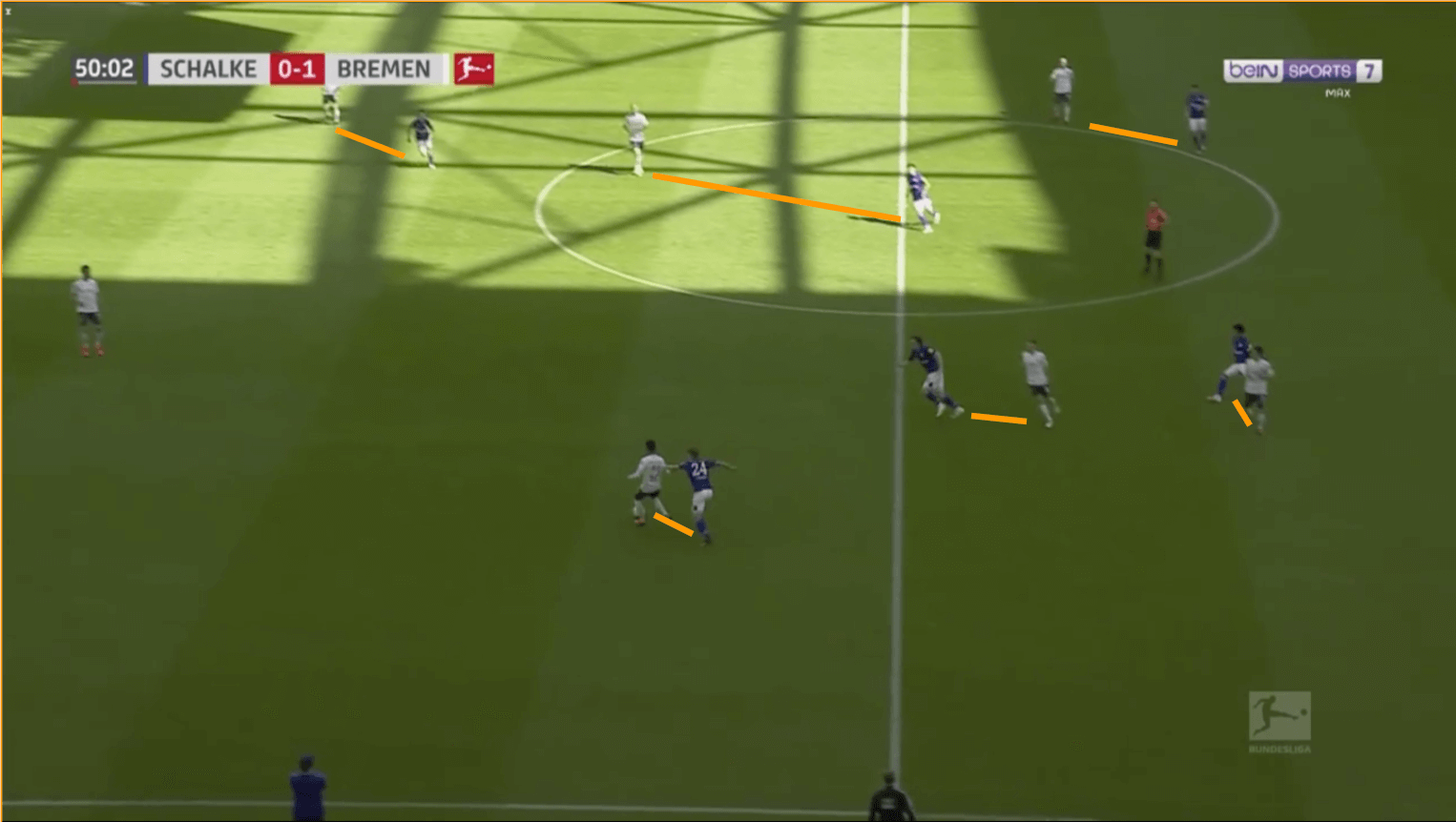

In this instance, Werder Bremen had five attackers in between Schalke’s two defensive lines. From a central defender’s stand point, this must have looked like absolute chaos. There are too many men in front of you to mark, causing some confusion about what the next steps should be. The effectiveness of this numerical overload was increased due to the width that Werder established. In the image above, Werder had wide options on both sides of the pitch. Fridel’s positioning, at the bottom of the image, was incredibly important because he is pinning (similar to catching the attention/focus) Schalke’s Kenny, which means there is more room for Werder to operate in the centre of the pitch.

Weston McKennie dropped to apply pressure on the first pass just as Kabak stepped up to apply pressure from the final defensive line. Neither were able to properly defend Klaassen, whose deft first touch led Bremen to this situation below.

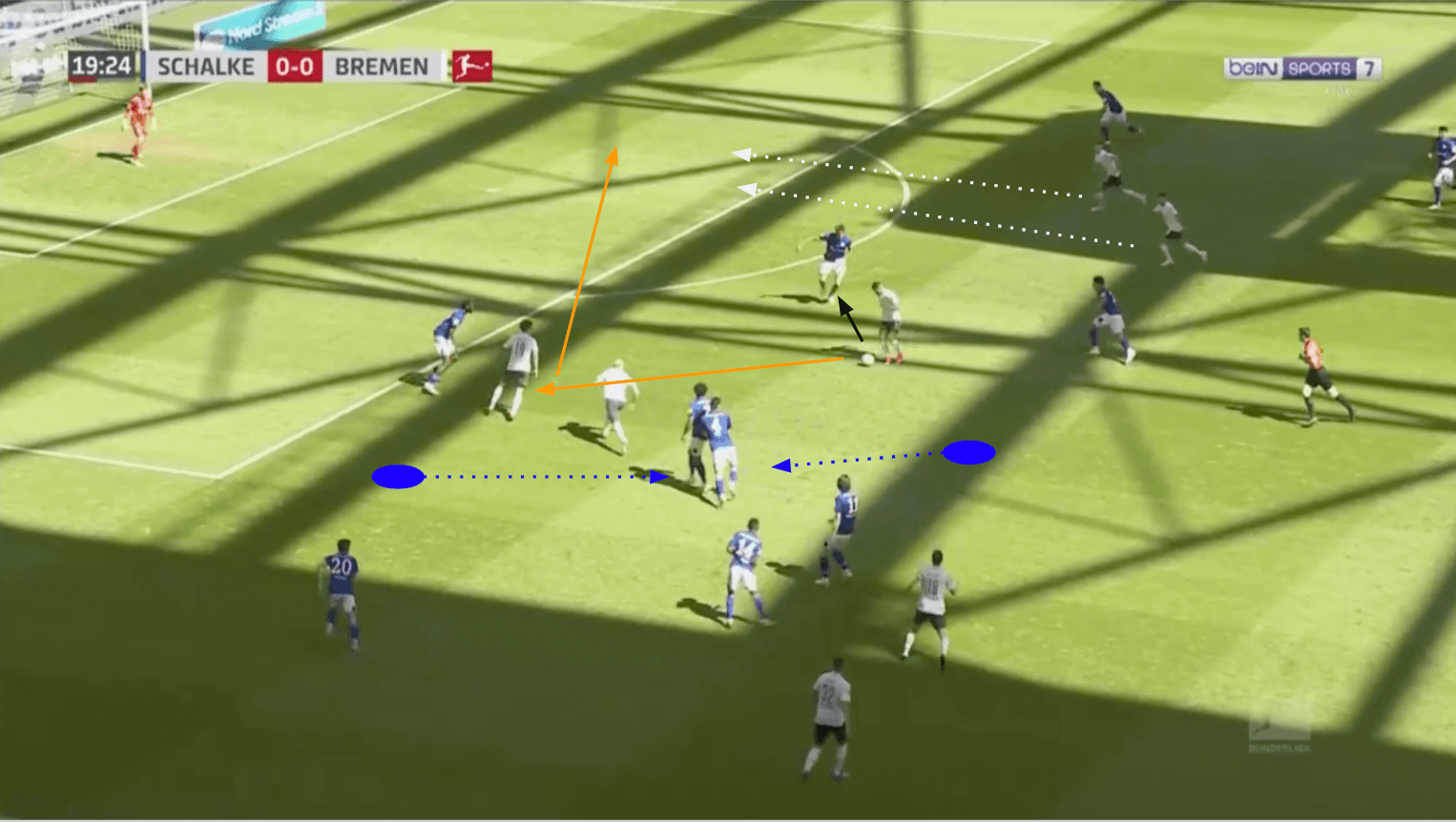

This image perfectly encapsulates what Werder was attempting to achieve. By overloading the centre of the pitch, Schalke were forced to make too many defensive decisions too quickly, resulting in massive passing lanes opening up for Werder. Ideally, Rashica and Werder would have completed the passes marked in orange above, Finding Sargent and allowing his teammates on the opposite side to make third man runs; instead, he tried to force the ball to those teammates, which resulted in Todibo, who is on loan from Barcelona, defending well enough to cause a deflection and prevent the chance from being taken.

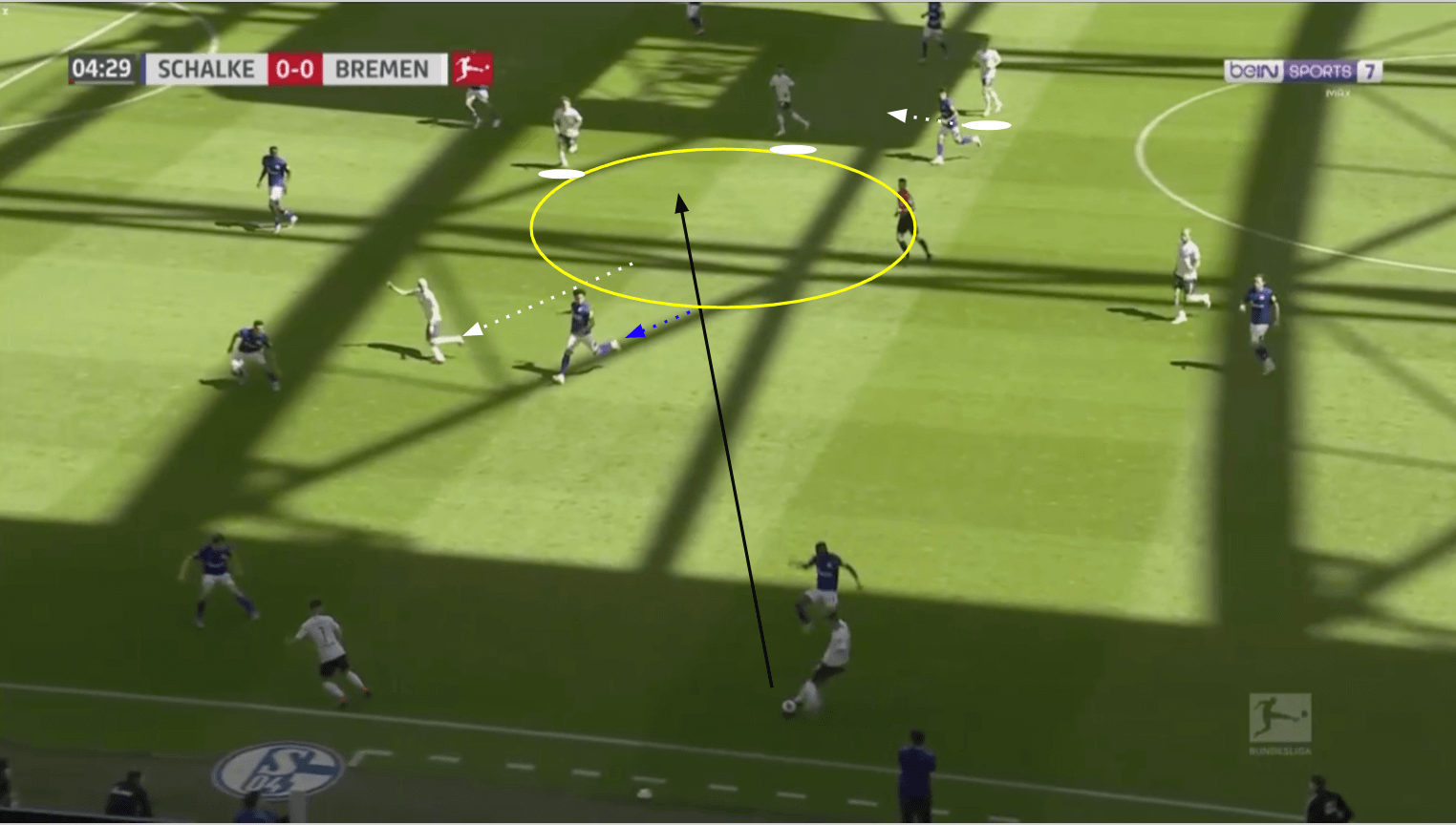

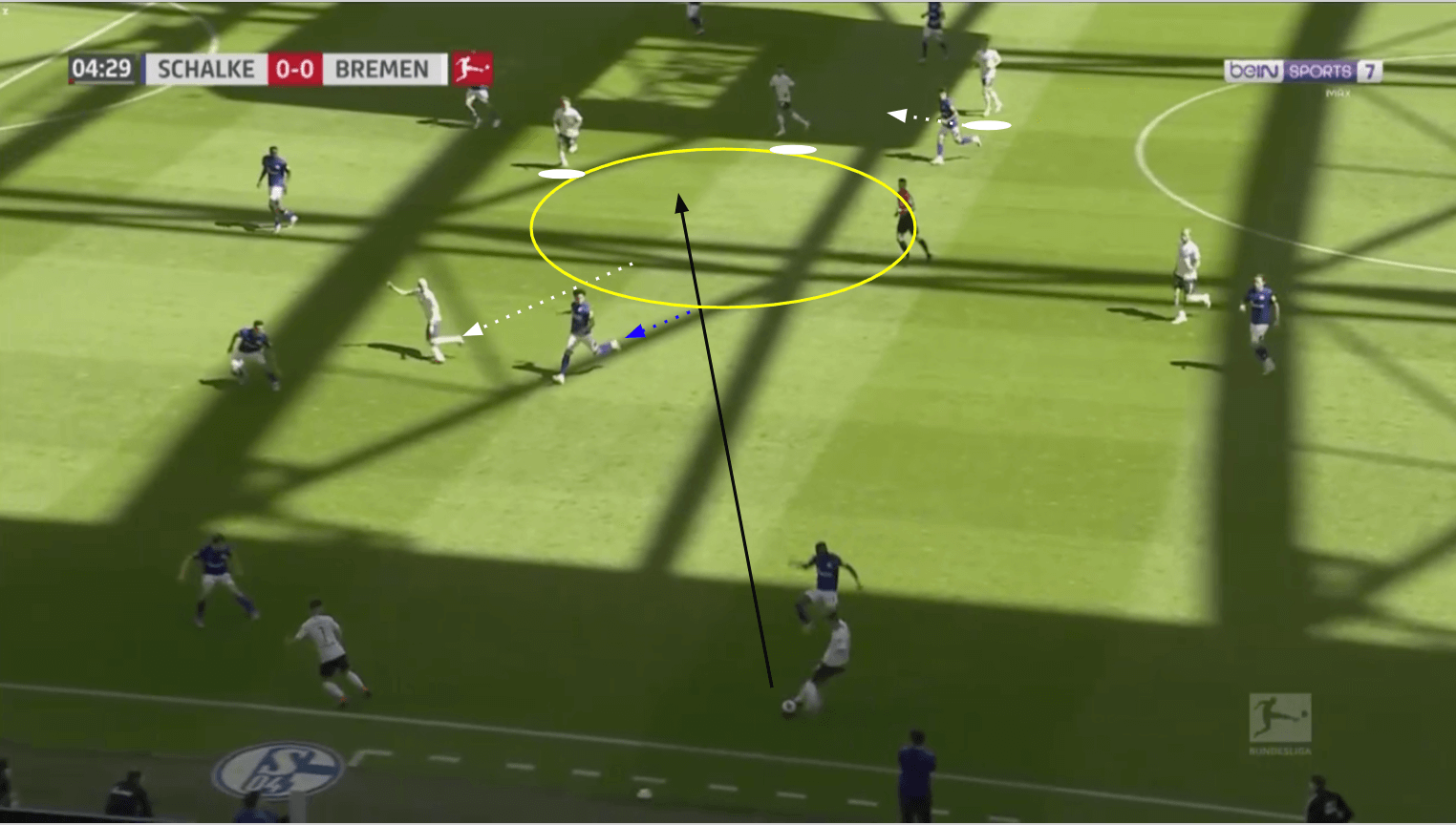

Another way that Werder tried to gain access to the central space in possession was by manipulating runs into half-spaces in order to attract opponents. These runs were particularly effective because they already had so many men between the lines of pressure.

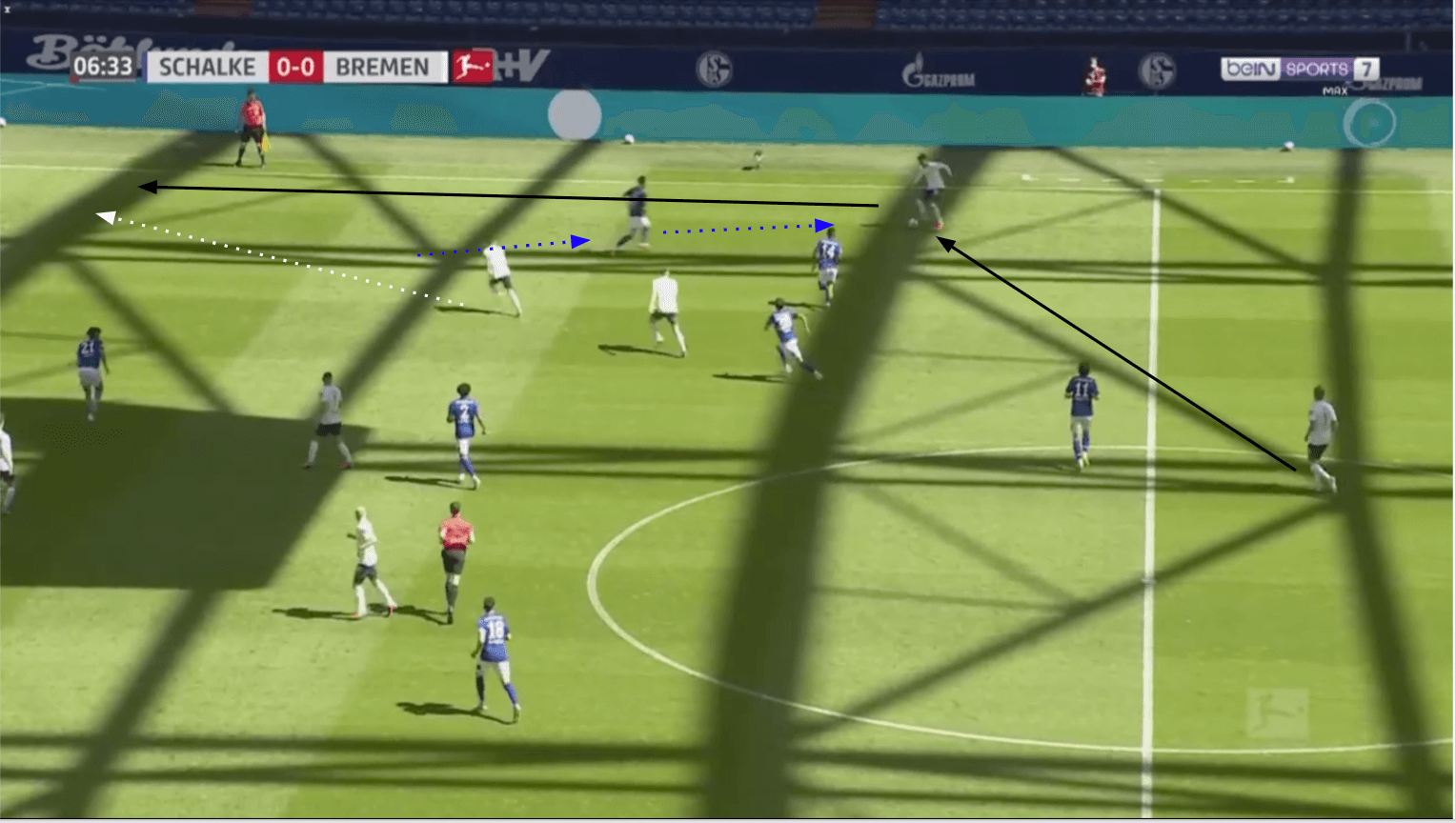

Here, Klaassen made a diagonal run from the centre of the pitch into the half-space. Behind Klaassen, two Werder players were already between the defensive lines while another one was in the midst of joining. McKennie followed Klaassen, allowing Friedl to play the diagonal ball into the open space. Even though Friedl’s ball was behind Sargent, there was some much space available that Sargent still had time to get possession, turn, and dribble towards Schalke’s goal.

The overload also allowed them to make runs from midfield while still maintaining their numerical advantage.

Klaassen made the run from midfield. As he did before, McKennie followed Klaassen’s run. This again opened up space, although this time there was even more of it because Werder’s move started in the middle third as opposed to the final third. Klaassen used his first touch to lay the ball back to Rashica, who promptly played Bittencourt, who was in one of the most dangerous positions on the pitch. Werder was unable to generate a chance from this instance, but their counter-pressing immediately after this led to Klaassen getting a shot off seconds after Bittencourt received the ball.

Central overload created opportunities on wings

Werder did well in the first half to try and overload the centre of the pitch. While their lone goal ultimately came from some excellent pressing, they also used the overload to create chances down the wide areas of the pitch.

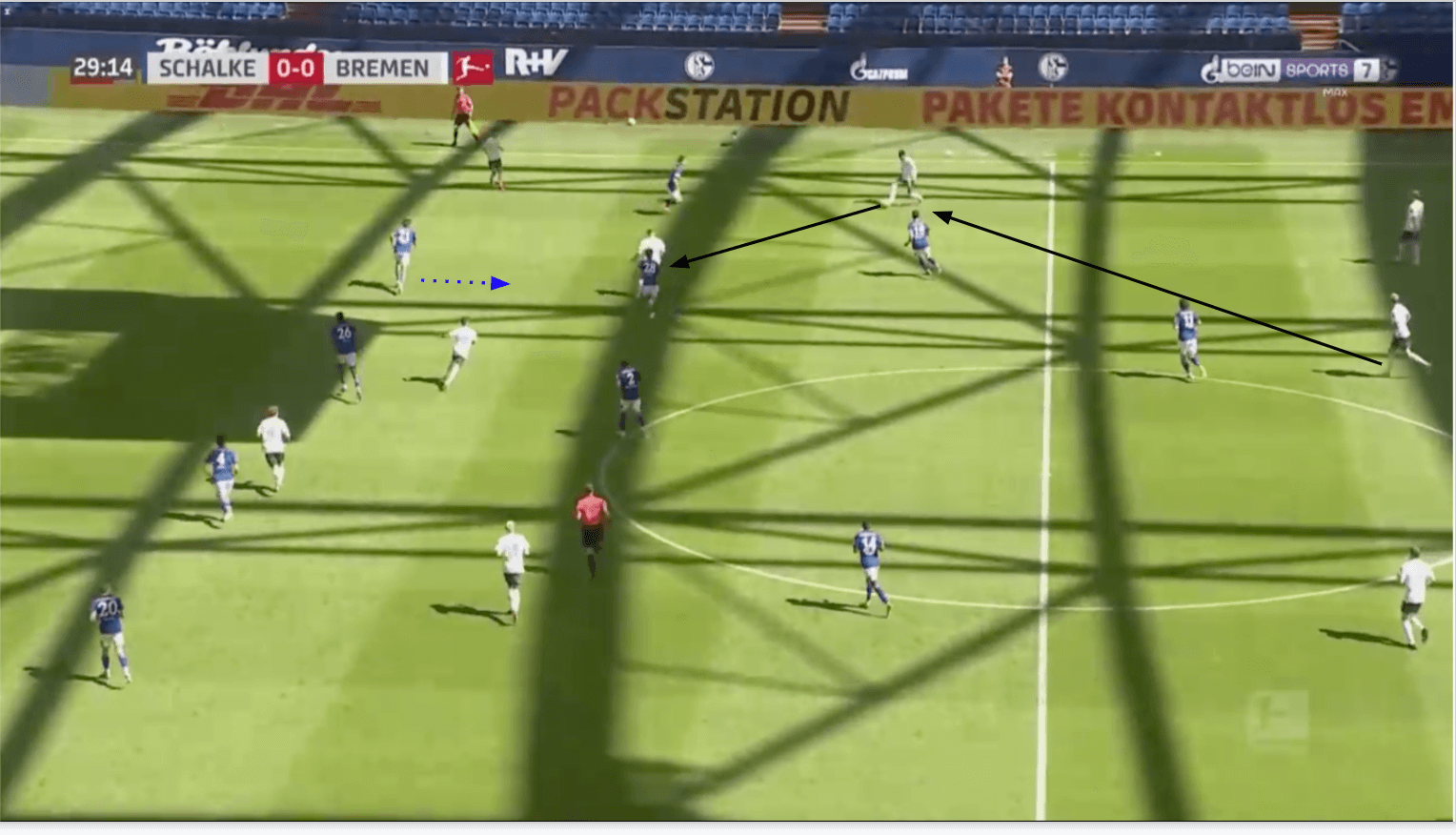

As previously mentioned, the central overload caused a lot of stress on Schalke’s backline, as decisions became more reactive than proactive. If Schalke’s midfield defensive line was too high, Werder’s outside-backs could attract the attention of Schalke’s wing-backs. The consequences of the movement left a large amount of space for Werder to exploit on the flanks. In the image above, Gebre Selassie was pressed by Miranda. Miranda leaving his position meant that there was lots of room to be exploited, which Bittencourt did. His run down the line allowed him to be put in a 1v1 situation against Todibo with lots of space for him to run into.

This movement can become even more dangerous for Werder when they have a man who can occupy the half-space while also having a man positioned out wide. This triangular shape allows for positional superiority, which Schalke was not prepared to handle.

In this instance, the ball was again played from Vogt, who would drop in between the two centre-backs, effectively forming a back three. This back three allowed for superiority, especially in terms of ball distribution. Vogt could now pass the ball from the central channel to the wide channel, causing the Schalke defence to shift over a large area of space. When Gebre Selassie was pressed by the Schalke player, the pass to the interior became ideal. In this instance, possession was lost by a misplaced pass. However, what Werder was attempting to achieve is still present. If Gebre Selassie can find Eggestein with this pass, Eggestein can effectively turn and dribble at Todibo, the left centre-back. By attracting Todibo, Eggestein would have been able to lay the ball off to Rashica, who is the wide man in the image. This would allow him to dribble at speed toward Schalke’s goal with the nearest defender out of position.

What made this so effective for Werder was that they were able to recognise when to look to exploit the wide area versus the interior of Schalke’s defence.

In the image above, Gebre Selassie had the ball at his feet after receiving it from Langkamp, the centre-back. The diagonal run is again made in behind Caligiuri, who had stepped to press Gebre Selassie. However, in this instance, Gebre Selassie was able to recognise that Werder were outnumbered in this area of the pitch. The attackers in between the lines hadn’t shifted over with the ball, and so instead of forcing it, Werder maintained possession and looked elsewhere to exploit Schalke’s defence.

Schalke’s halftime adjustments

After the first half it was abundantly clear to both the viewer and David Wagner that changes needed to be made at halftime if Schalke were going to have a chance to get back into the match. Schalke had 30% of possession in the first half with only two shots taken the entire half, neither of them on target. The first thing Schalke did that was incredibly effective was they began to press Werder much higher up the pitch, becoming the team who dictated what would happen in the match.

Here, Schalke’s man-oriented pressing forced the ball backwards to Werder’s keeper. Schalke continued to press Pavlenka, the goalkeeper, which caused him to clear the ball. Schalke won the aerial battle and were quickly back in possession. This was Schalke’s second instance of pressing in the second half, and there weren’t too many more. As soon as Werder realised that Schalke were intent upon pressing them higher up the pitch, they began sending aerial balls into the middle of the pitch. Werder was desperate to hold on to their lead, and they mitigated their risk by not playing the ball out of the back.

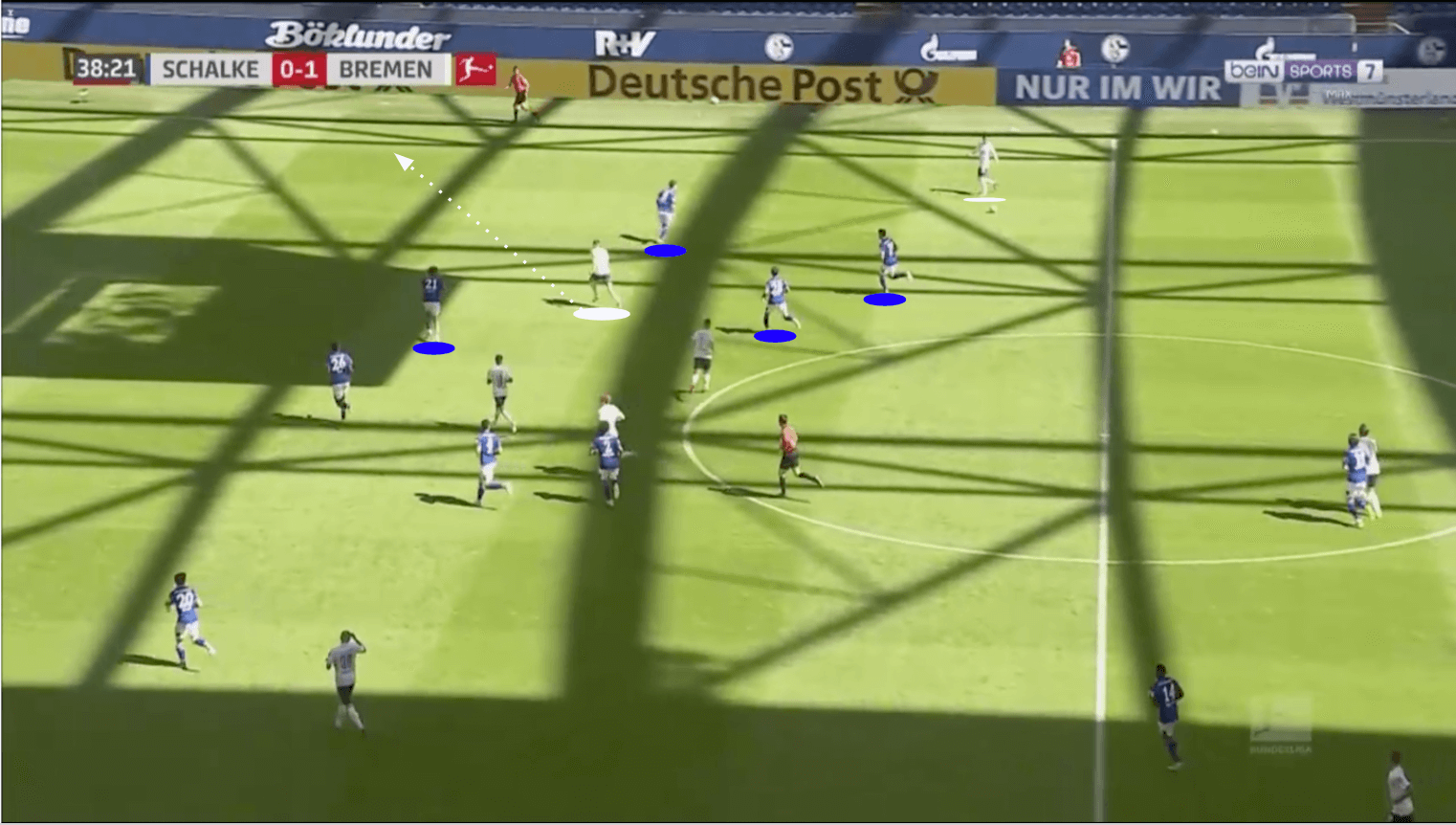

With Werder not afraid to sit deep defensively, Schalke were forced to try and break them down, which proved to be a struggle for them. The timing and movement of the squad was not synchronised, so even in possession, Schalke struggled to be effective.

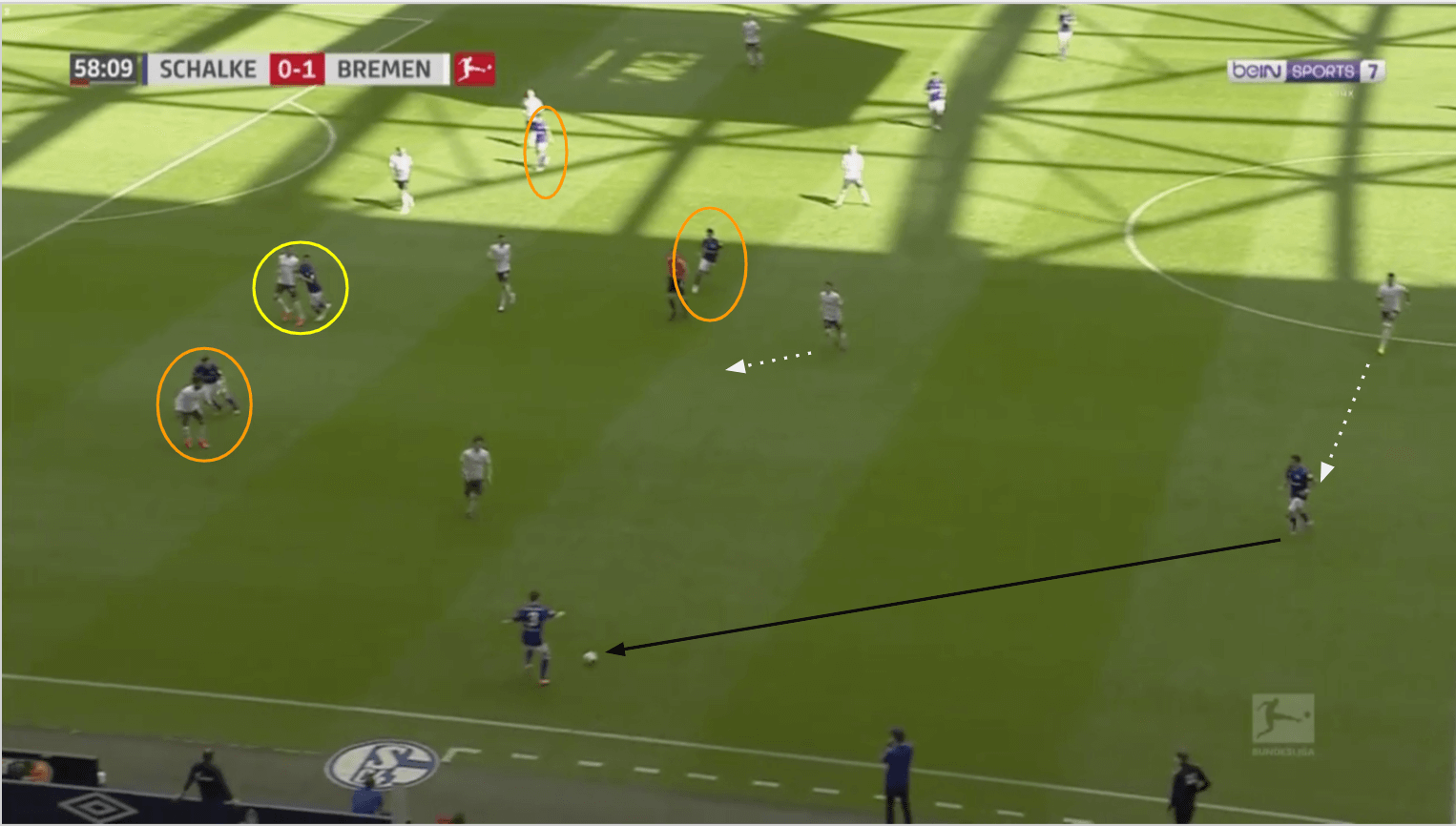

In this instance, Schalke had a restart after a foul in the centre of the pitch, essentially at midfield. The ball was played to Nassim Boujellab, who was now operating as the left centre-back, as Schalke had switched to a 4-1-3-2. Boujellab was very clearly going to play the ball to Miranda, the left-back. As the ball arrived at Miranda’s feet, Miranda had no options to progress it forward. The Schalke players highlighted in the orange circles were effectively irrelevant because they were in the cover shadow of their respective Werder player. The man in yellow has no way to properly receive a pass from Miranda because he’s marked too tightly by his man. The only man who appears to be open in the image is Boujellab, but even he was closed down by Davie Selke. Miranda had zero passing options in any direction, and he consequently lost possession.

When Schalke wasn’t trying to break down a compact Werder defence, they looked to take advantage or Werder getting forward, trying to hit their teammates with long passes that would allow them to take advantage of Werder sending men forward. These passes were often played over the top of Werder’s backline and weren’t very effective. The passes were also made into the feet of Schalke’s forwards, as seen below.

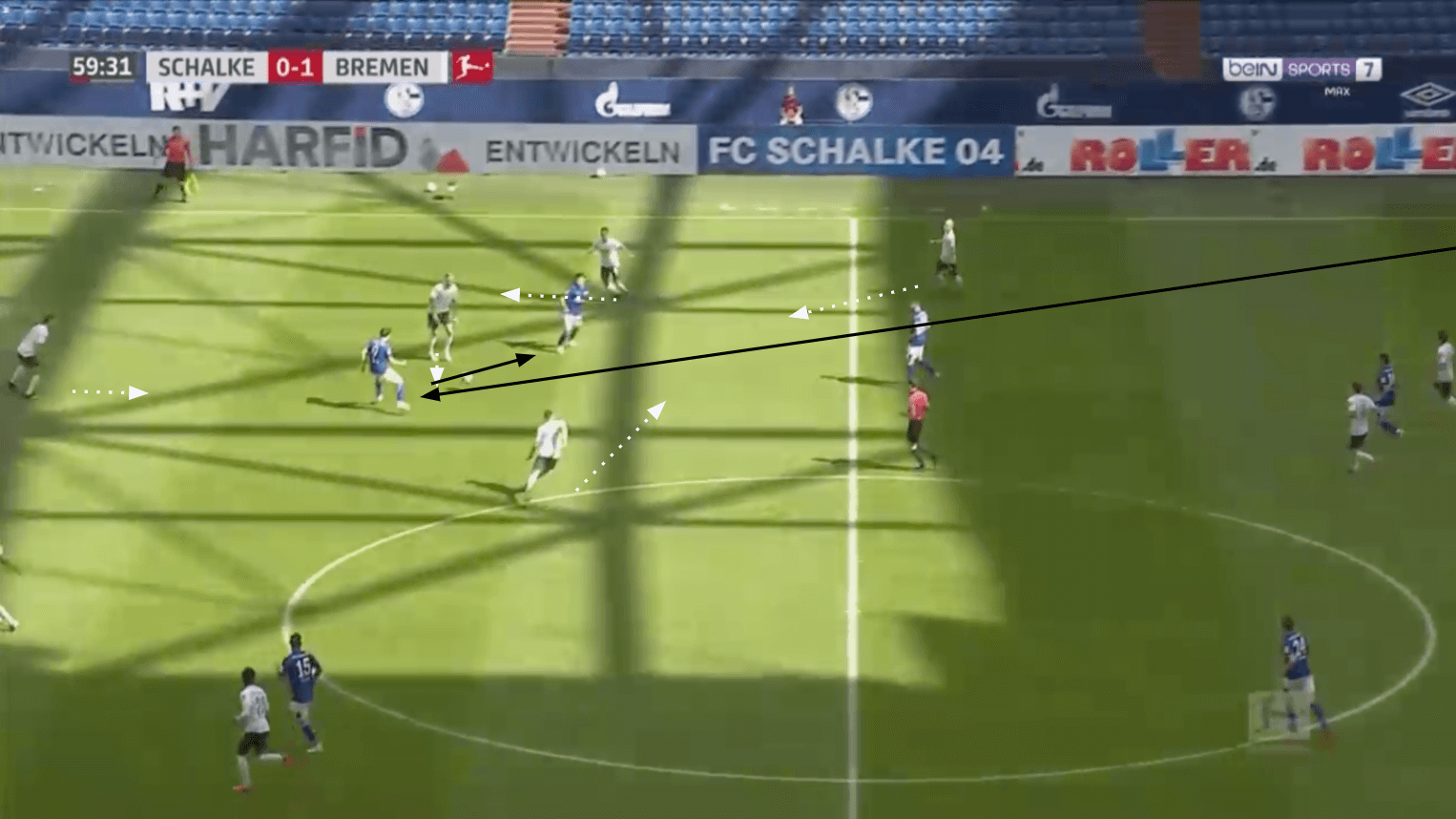

This ball was played by Jonjoe Kenny into the feet of Benito Raman. Even before Raman received the ball, the Werder defenders collapsed on the space around him. Raman used his first touch to lay the ball off to his teammate before curling out of the space. When Alessandro Schöpf received the ball, he was under immense pressure from the Werder players, who soon outnumbered Schöpf and teammate, five to two. Unsurprisingly, Werder won possession back because of their ability to outnumber and out-position the Schalke attack. While Schalke’s initial idea to press allowed them to see more of the ball, they truly struggled to use that possession to create any meaningful chances.

Conclusion

While Schalke will certainly not be happy with the result, there is some comfort for the club as they are unlikely to be relegated this season. That being said, the majority of their remaining matches are against clubs who are higher in the table than they are, which is cause for concern. They’ll look to get back in the win column next weekend when they play against Union Berlin. Werder should feel more confident moving forward, as they’ve kept two clean sheets in a row and demonstrated their defensive ability last weekend against Gladbach. They’ll need that confidence flowing, as matches versus Paderborn and Bayern Munich loom on the horizon. On Wednesday, they’ll face Eintracht Frankfurt before taking on Wolfsburg at the weekend.

Comments