One of the most tactically interesting matchups in the Bundesliga this weekend saw Peter Bosz’s Bayer Leverkusen take on Julian Nagelsmann’s RB Leipzig. The managers have had some interesting match-ups in the past, with Peter Bosz’s possession-based style of play often clashing with Nagelsmann’s style, and so the game was set up to be another interesting encounter. As it happened, the game was a fairly even affair, with both teams doing a good job of nullifying each other and being tactically astute. In this tactical analysis, we will look at the tactical approaches of both teams and how these interacted with each other, as well as examining the effect Julian Nageslmann’s tactical change had on the game.

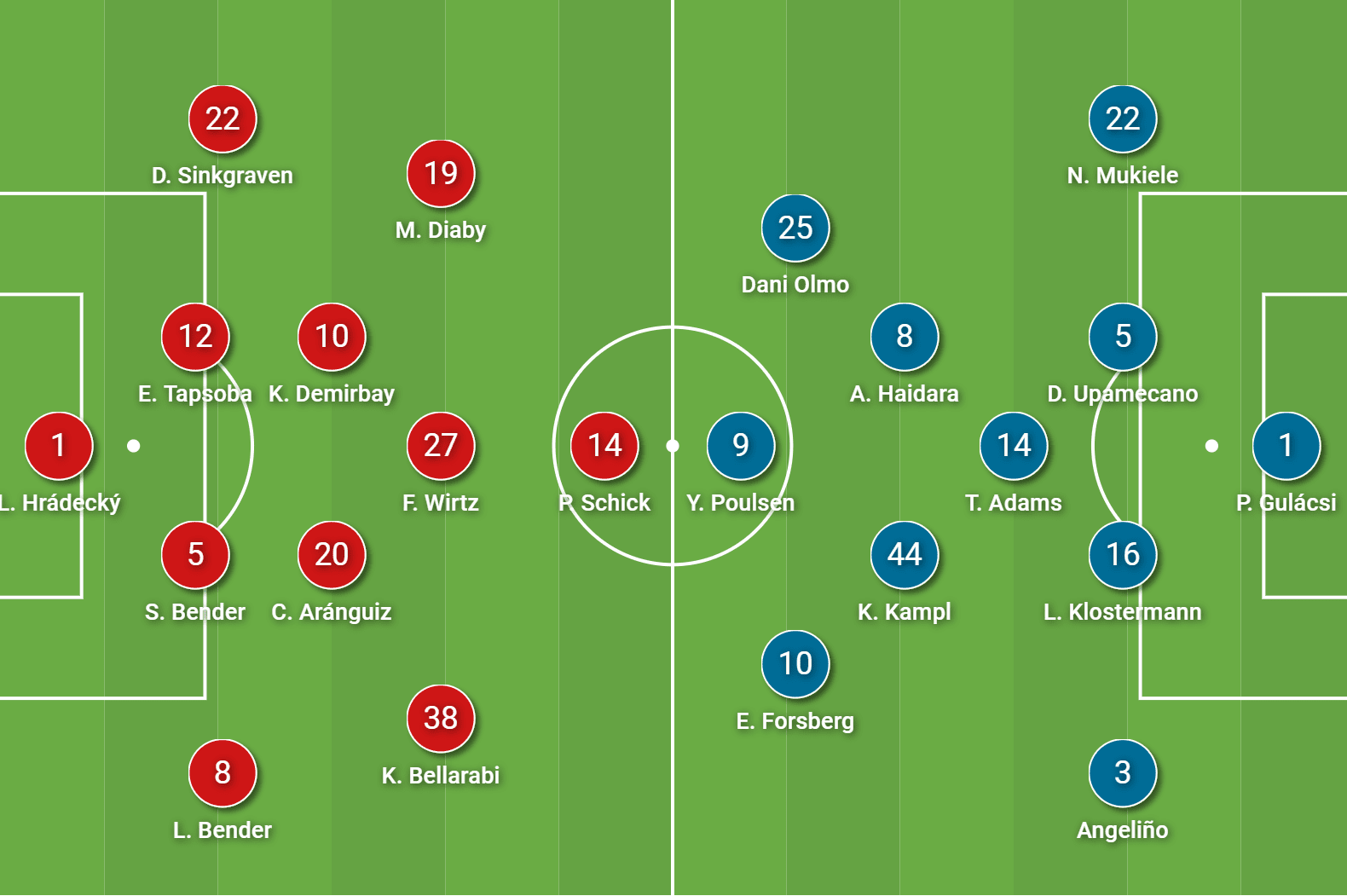

Lineups

In true RB Leipzig fashion, their formation was adjusted throughout the game and doesn’t resemble the graphic provided by Wyscout here. As I will detail within the analysis, their first half formation resembled more of a back-three with Dayot Upamecano, Lukas Klostermann, and Nordi Mukiele making up that back line. Bayer Leverkusen meanwhile used a 4-2-3-1/4-3-3, with a midfield three consisting of Kerem Demirbay, Charles Aránguiz, and Florian Wirtz, with Wirtz filling the role of Chelsea new boy Kai Havertz.

RB Leipzig’s first half pressing

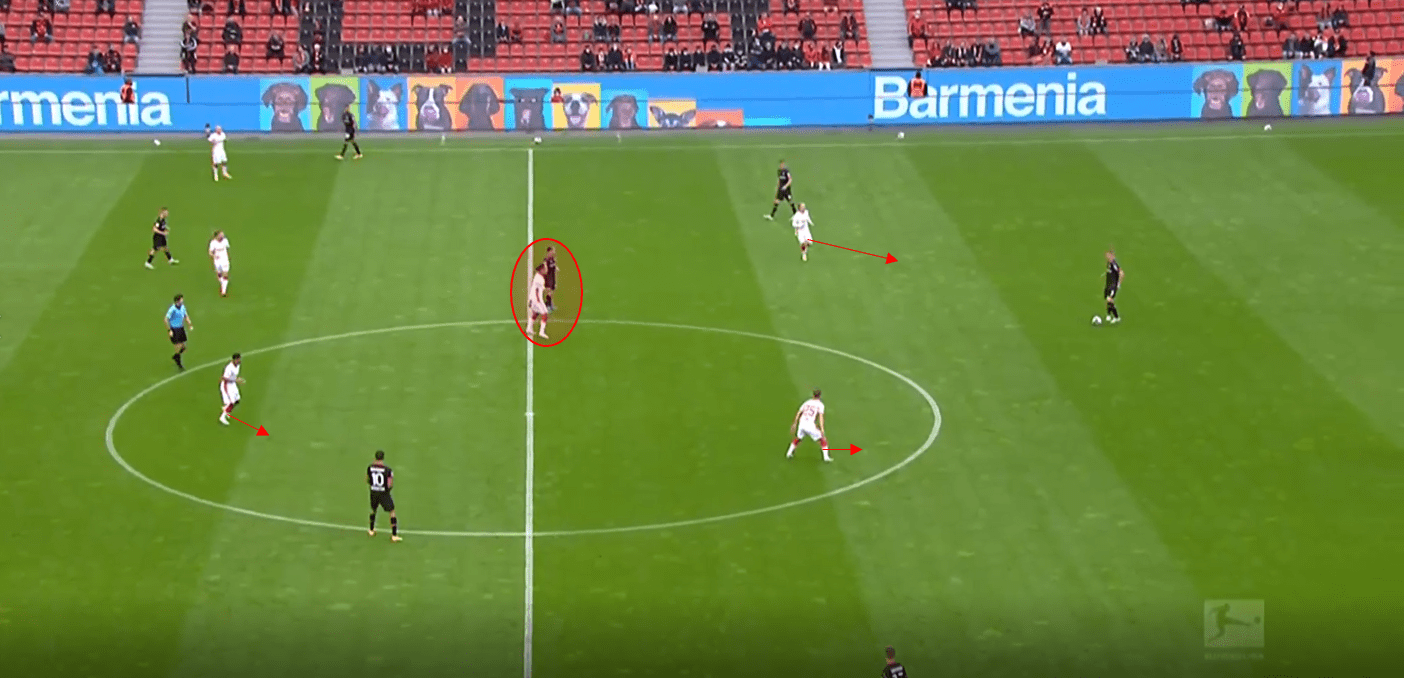

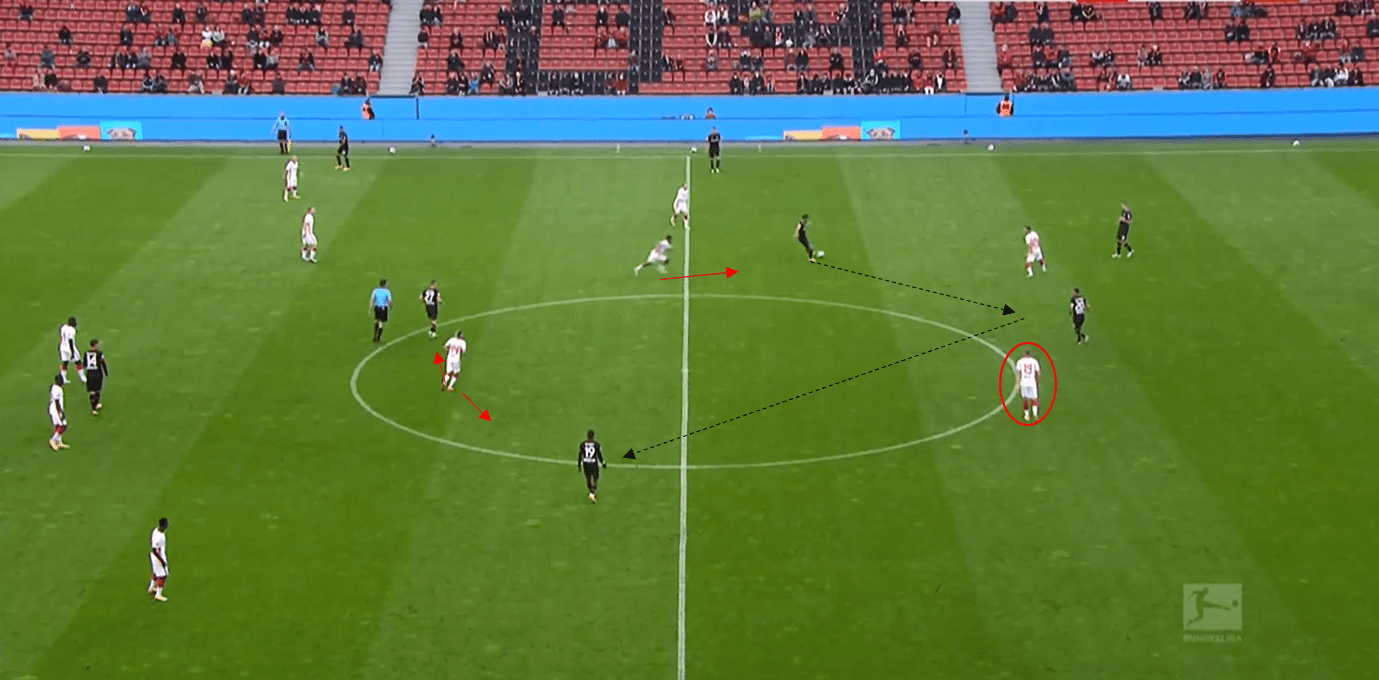

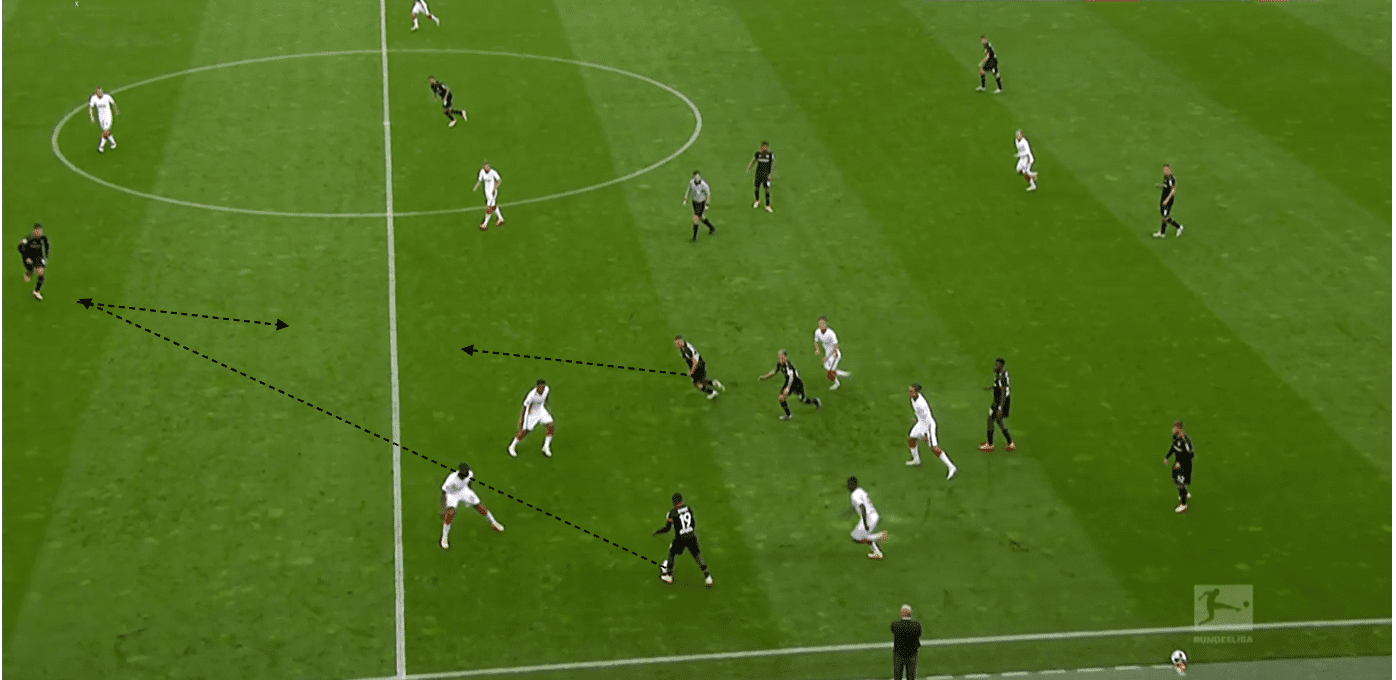

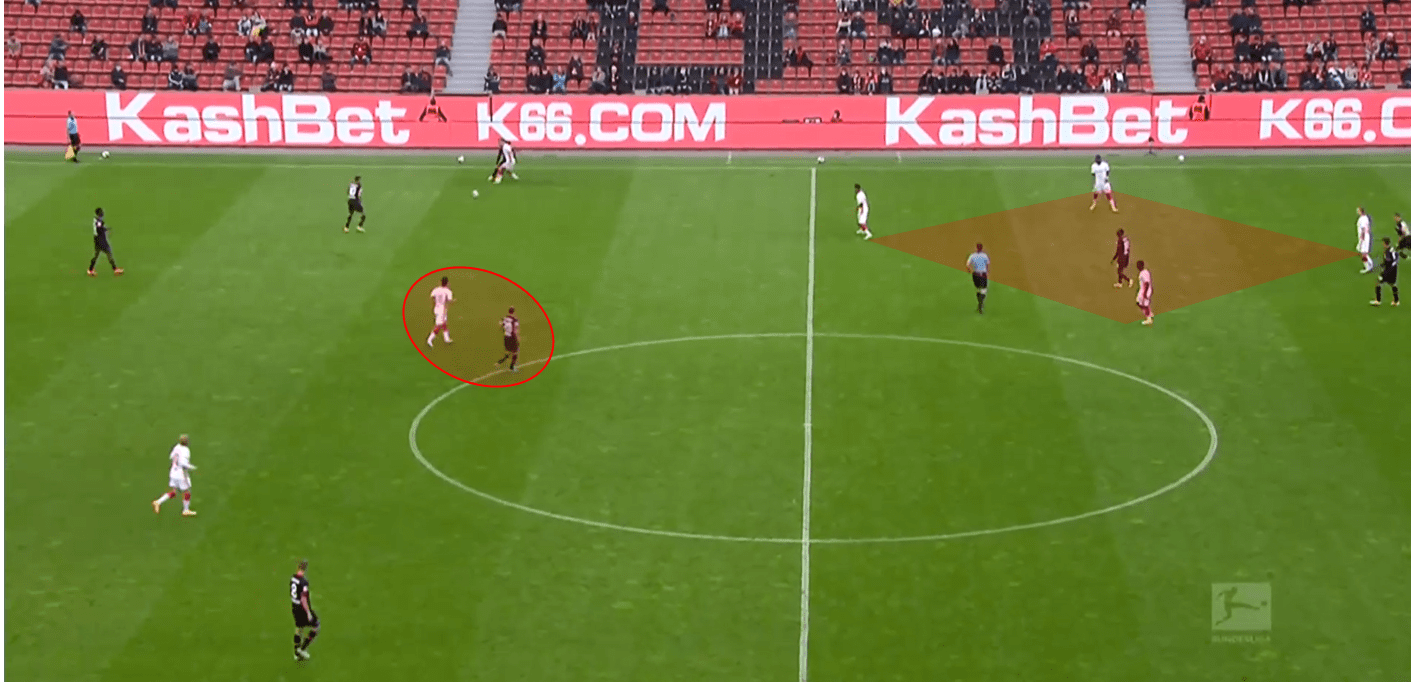

As mentioned, Leipzig started the game in a back three, with their lineup seemingly resembling a 3-4-3 on paper. The interesting part of this 3-4-3 was the role of Yussuf Poulsen, who did not engage in the first line press and would often change Leipzig’s shape to a 3-4-1-2. Poulsen was tasked with the role of covering the ball-near Leverkusen pivot, and so he would drop slightly deeper and look to cut off the pivot as a passing option. The two wingers would then be tasked with pressing the centre-backs, and they would usually cut the inside lane and show the pass to the full-backs, however at times like the one below, they would press in at an angle to cut the lane wide. The Leipzig central midfielders could cover the nearby Leverkusen midfielders, and as a result, Leipzig could maintain a 3 v 3 and prevent their midfield from being manipulated and overloaded.

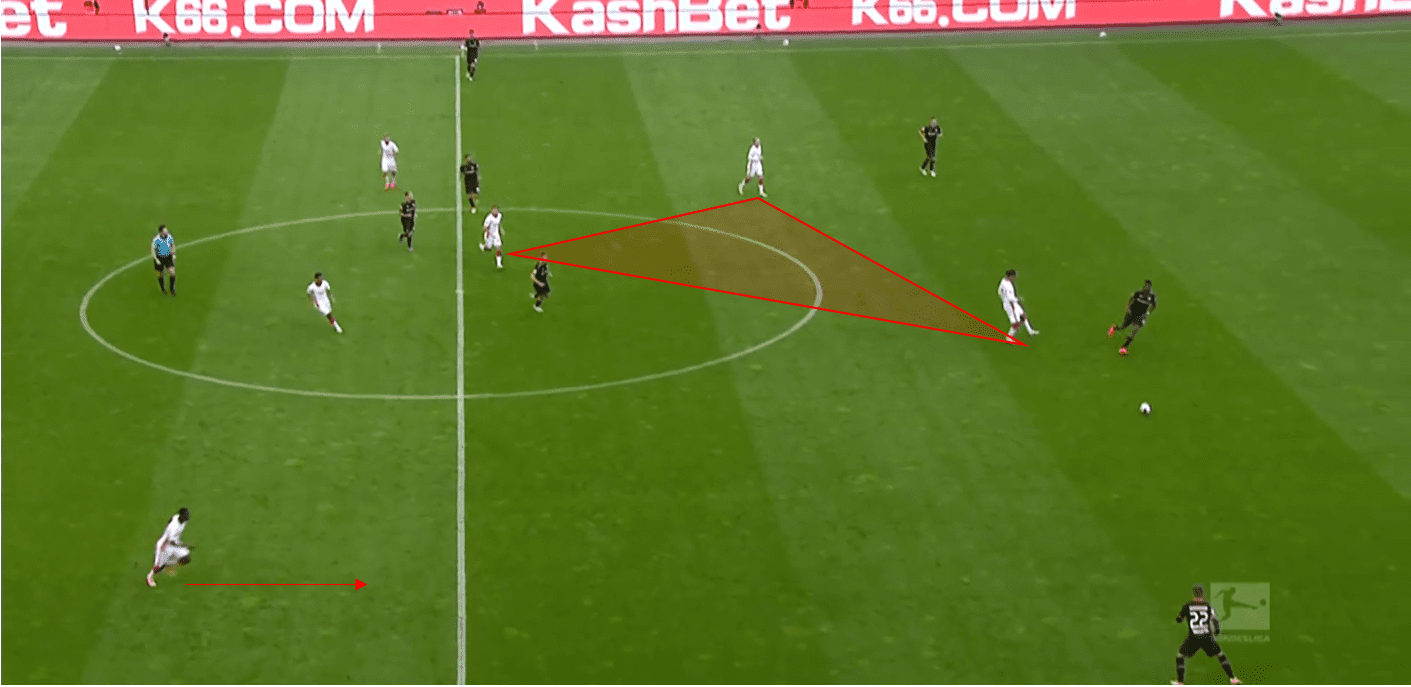

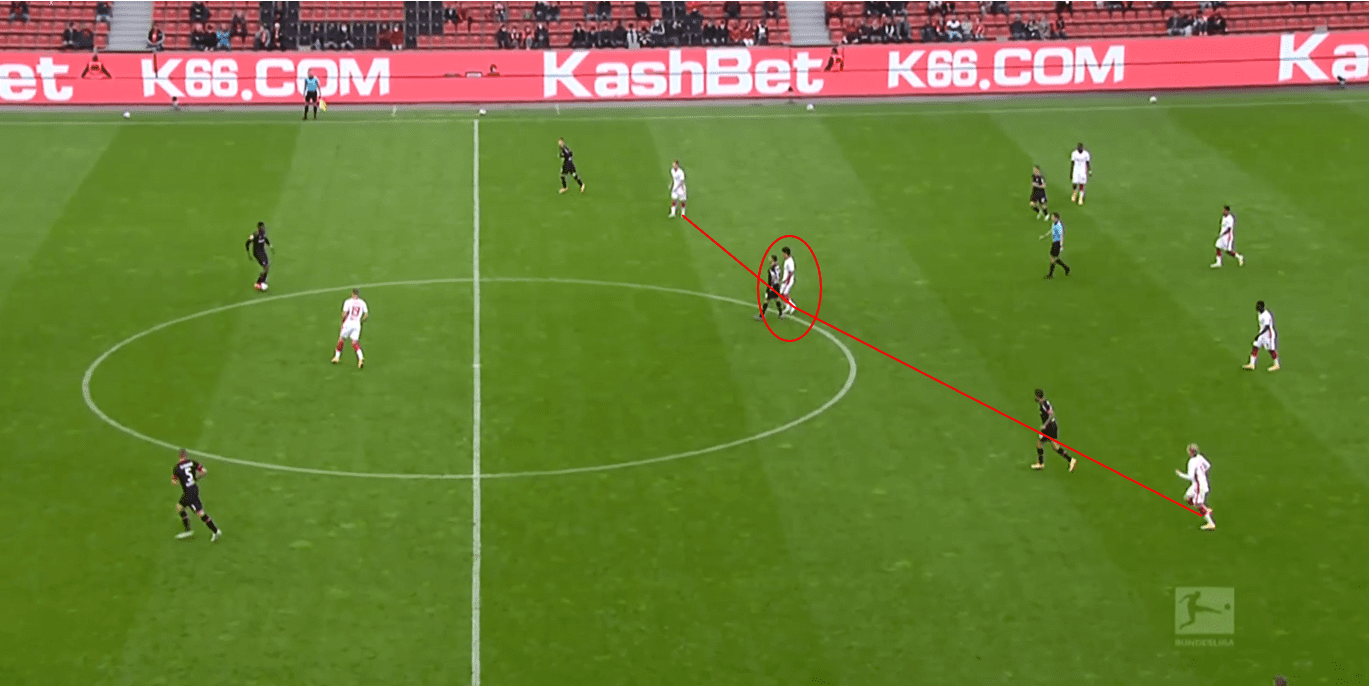

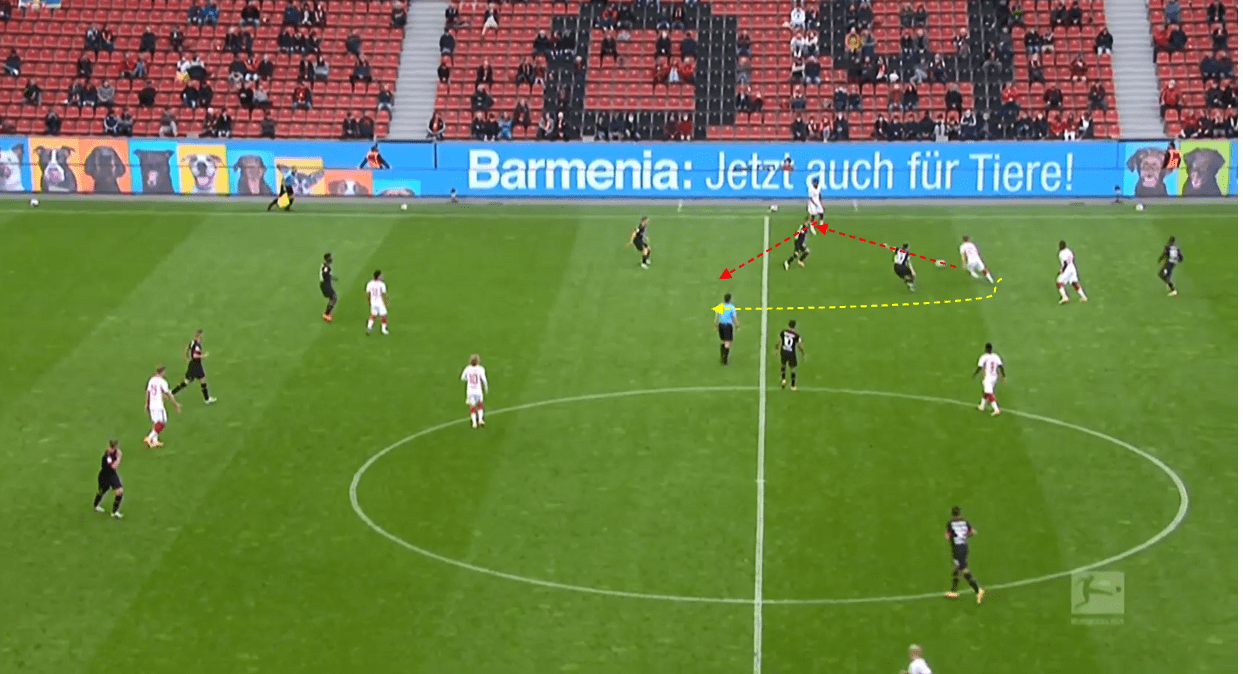

We can see an example here where Leipzig show Leverkusen into the full-back, where the wing-back can push forward to press. The Leipzig midfielders can stay deep and don’t have to push higher in order to press a deeper pivot, as Poulsen stays behind him here and applies pressure.

Leipzig pressed intelligently and as I’ve mentioned, would situationally cut the lane to the full-back and try to force the ball centrally. This was most often done in situations like the one below, where the wing-back is too deep to move forward and press the Leverkusen full-back. Leverkusen manage to find access to the full-back here though, and so they are able to progress high up the pitch with little pressure on the full-back.

The pressing roles within this front three were interchangeable, but it was often Poulsen who was given the role of covering the pivot. We can see an example here where Dani Olmo drops to cover the pivot while Poulsen presses the back line. We see Poulsen presses and shows the pass to the full-back, as the RB Leipzig right wing-back Amadou Haidara is within pressing distance of the player.

Poulsen would also situationally press the centre-backs from backwards passes, as at times he was able to press the ball backwards and keep the pivot in his cover shadow. We can see an example here where he marks the pivot while the full-back has the ball, but also prepares himself to press.

Once he has pressed the ball all the way back to the goalkeeper, he then moves backwards and again looks to cover the pivot.

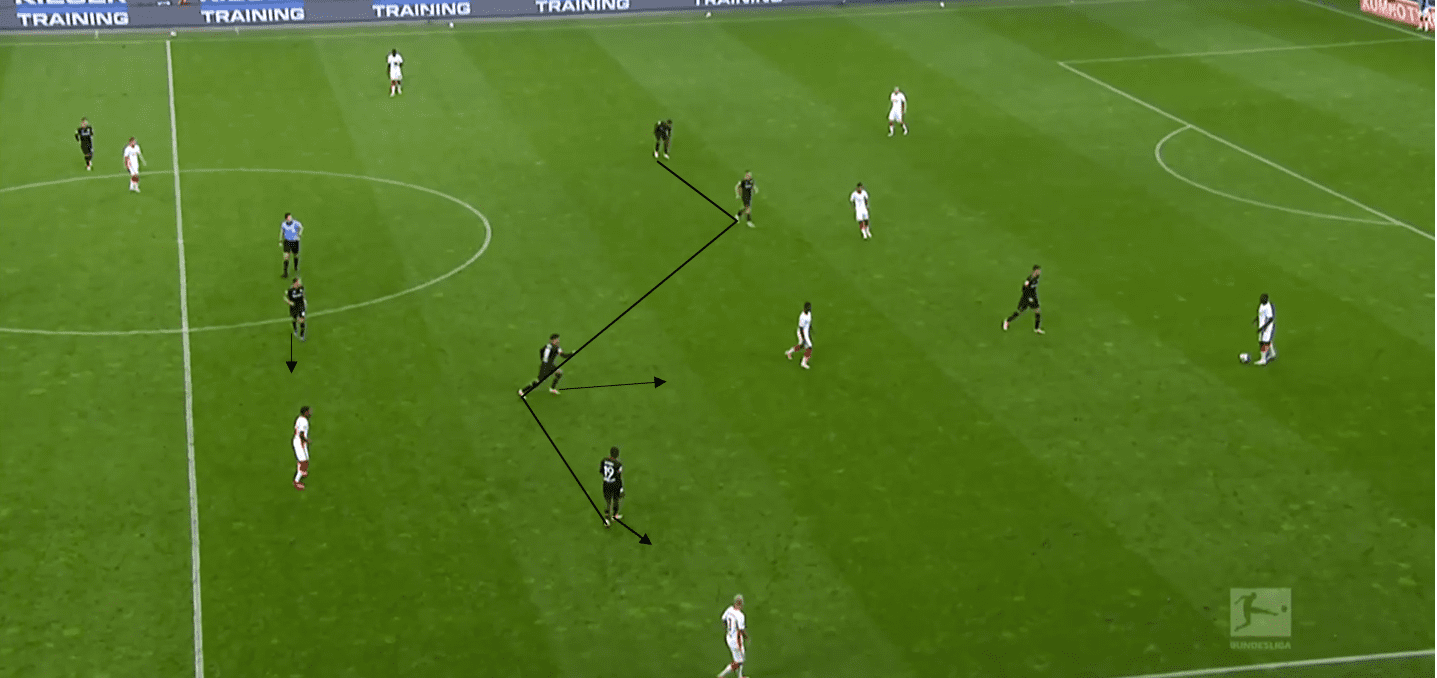

Poulsen’s injury disrupts Leipzig’s press

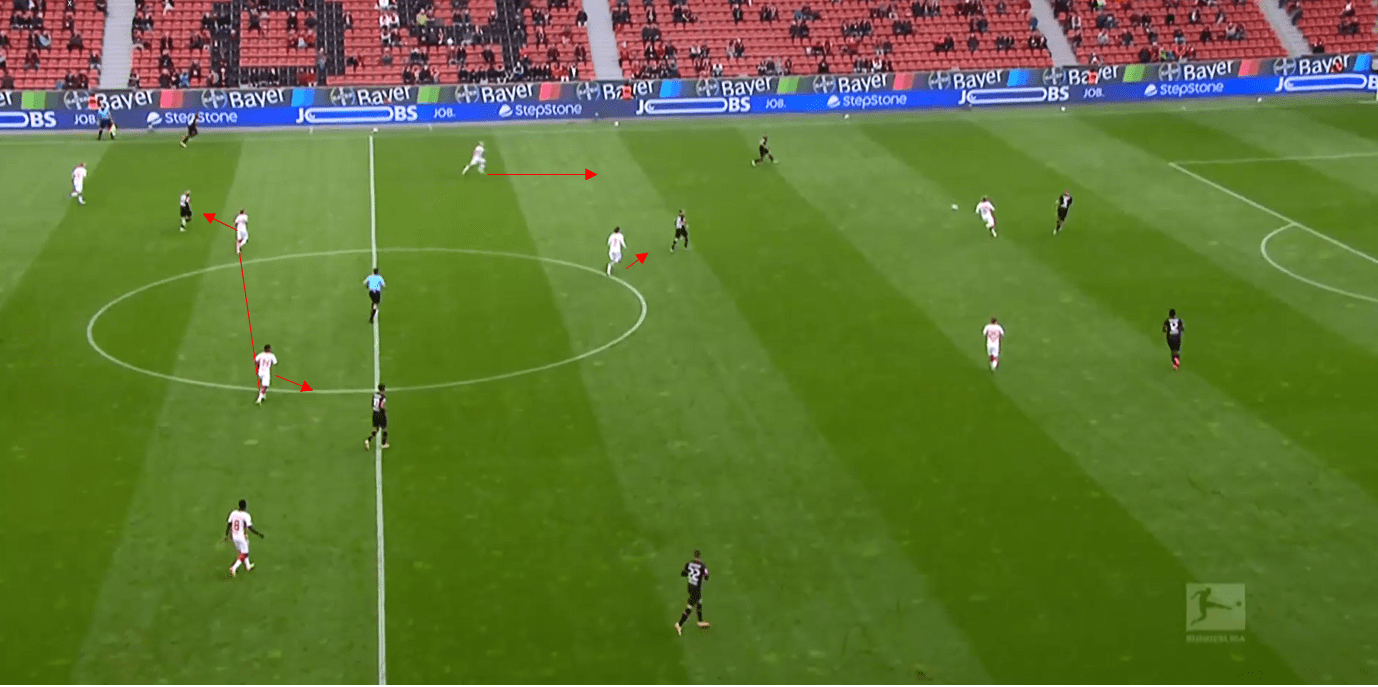

Around midway into the first half, Yussuf Poulsen was forced off the pitch through injury, and so new signing Alexander Sørloth was brought on. This change seemed to disrupt the way in which Leipzig pressed, with Leipzig struggling to continue with that pressing scheme due to their spacing and players performing different roles. We can see an example of this below here where striker Sørloth now presses the backline while the left-winger Emil Forsberg keeps tabs on the full-back. As a result of Sørloth pressing the centre backs, the pivot is able to get free, and so Leipzig react by having right-winger Dani Olmo now covering the pivot. This keeps them stable while the ball is on Leverkusen’s right side, but when the ball is switched Leverkusen can stretch play more.

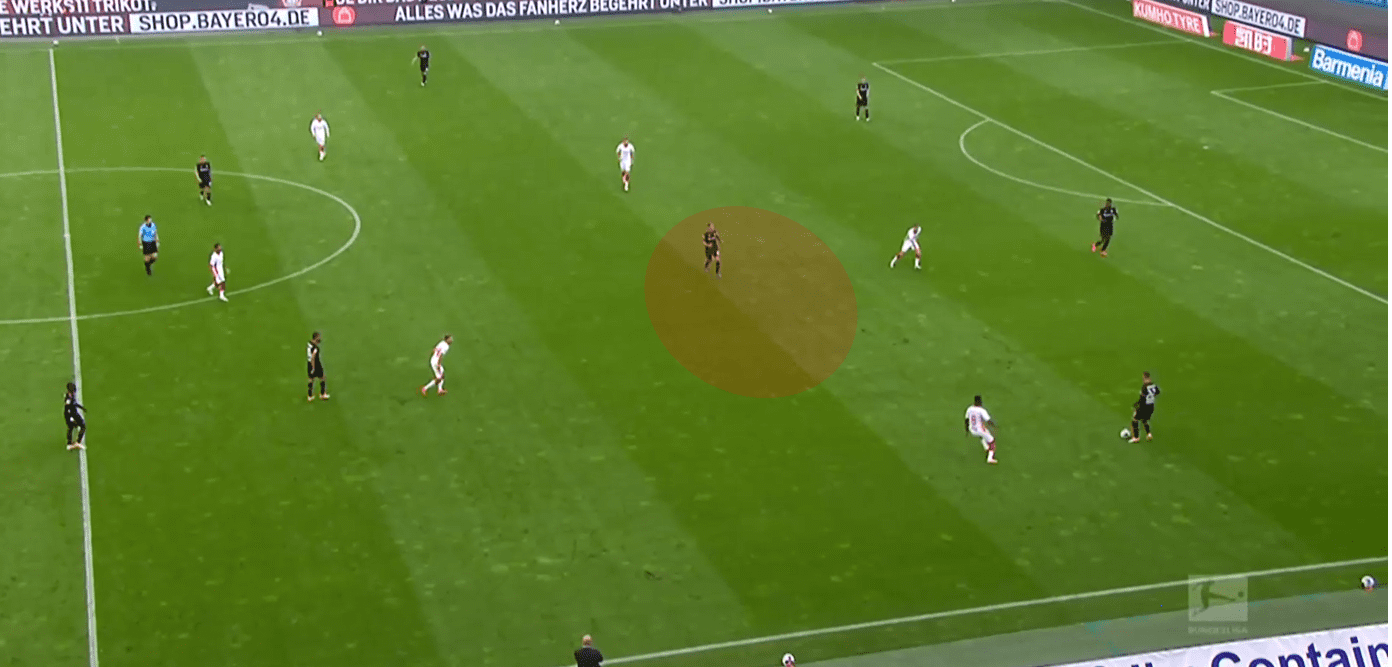

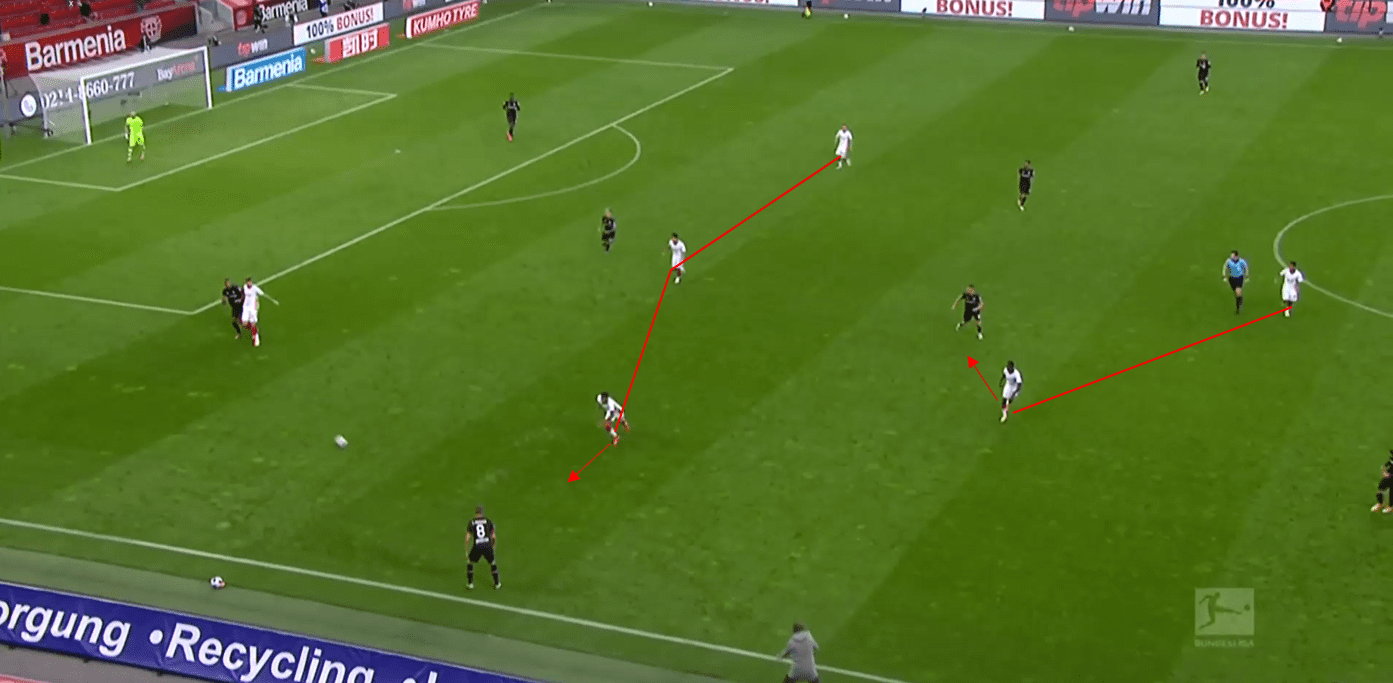

We can see here, a Leverkusen central midfielder receives the ball and is pressed from behind. Sørloth, having just pressed a centre-back, does not react and cover the pivot to prevent him from receiving. As a result, Leverkusen are able to access the overload they have created around Leipzig’s right central midfielder, with Diaby tucking in cleverly to create this advantage.

We can see another example here where Sørloth goes to press the centre backs, leaving the pivot open again here. A central midfielder can jump forward to press if needed, but this opens the chance for Leverkusen to utilise their overloads. As a result of some of their confusion while pressing, Leipzig seemed to opt to play it safe at times and fell into a more passive 5-4-1.

Leverkusen build-up

Leipzig’s pressing largely limited Leverkusen throughout the game, however, there were a few common trends which saw Leverkusen have some success. One of these, particularly in the first half, occurred in less organised phases of play, where Leverkusen’s structure sought to take advantage of that Leipzig pressing scheme. Leverkusen lined up in a 4-1-4-1 mainly in the game while in possession, and this use of quite wide wingers enabled them to hurt Leipzig in transition at times.

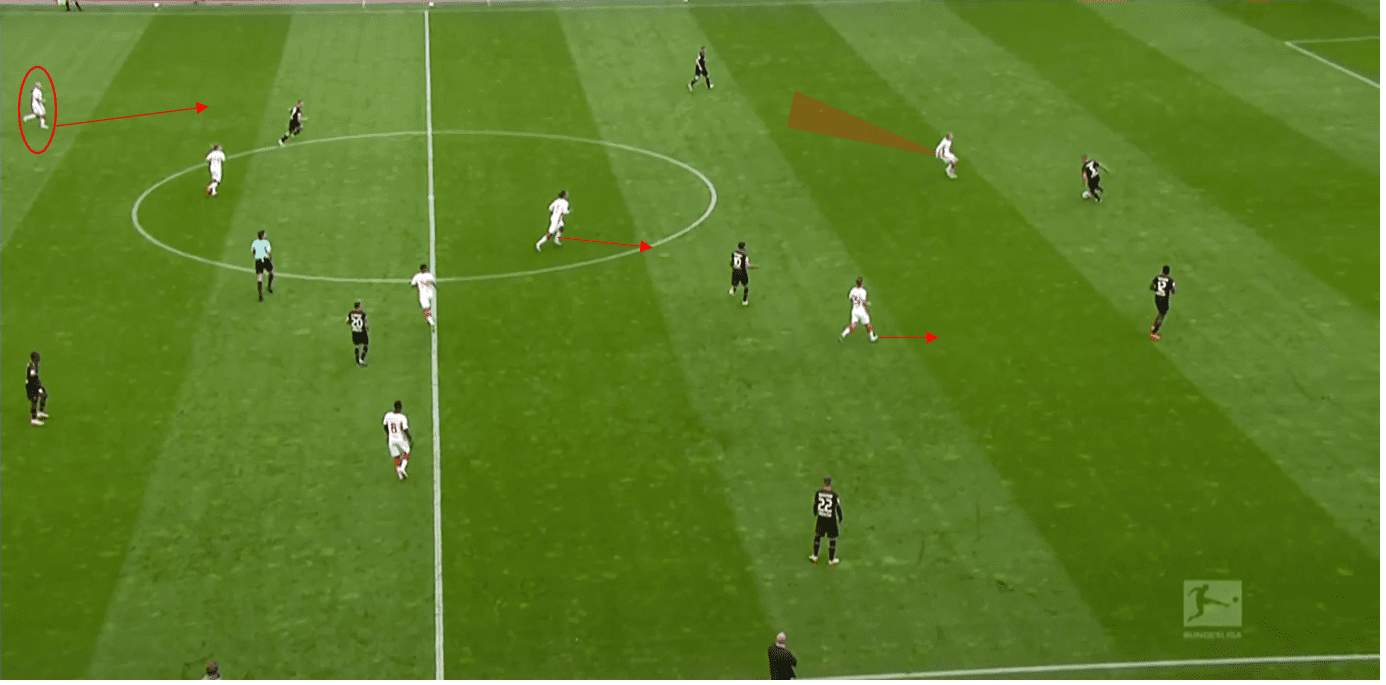

On a number of occasions, Leverkusen were able to find their wingers in the spaces behind the pressing Leipzig wing-backs, which enabled them to run at the back line and occupy centre-backs. We can see an example here where Kerem Demirbay is able to play a pass behind the Leipzig wing-back, who tries to jump early to press the Leverkusen full-back.

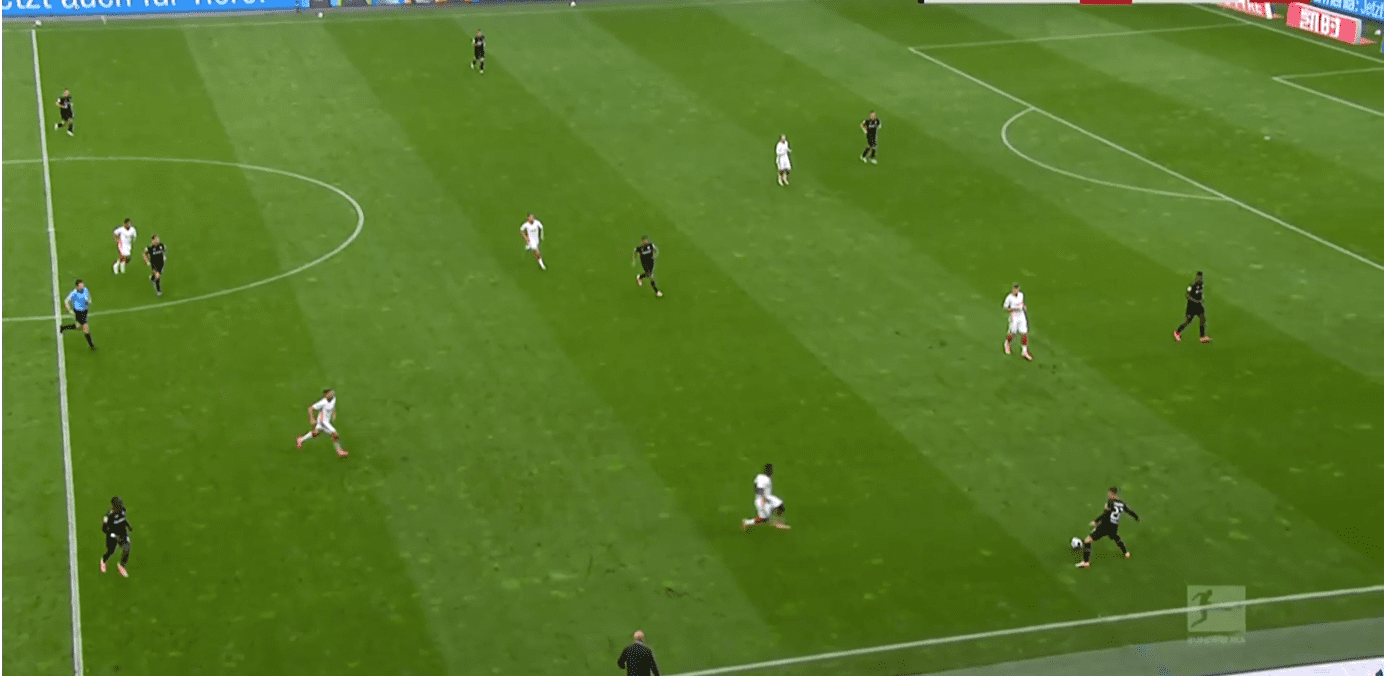

We can see another example here where during transition Angeliño is caught high up, and Karim Bellarabi is positioned high and wide in an attempt to exploit this space in behind.

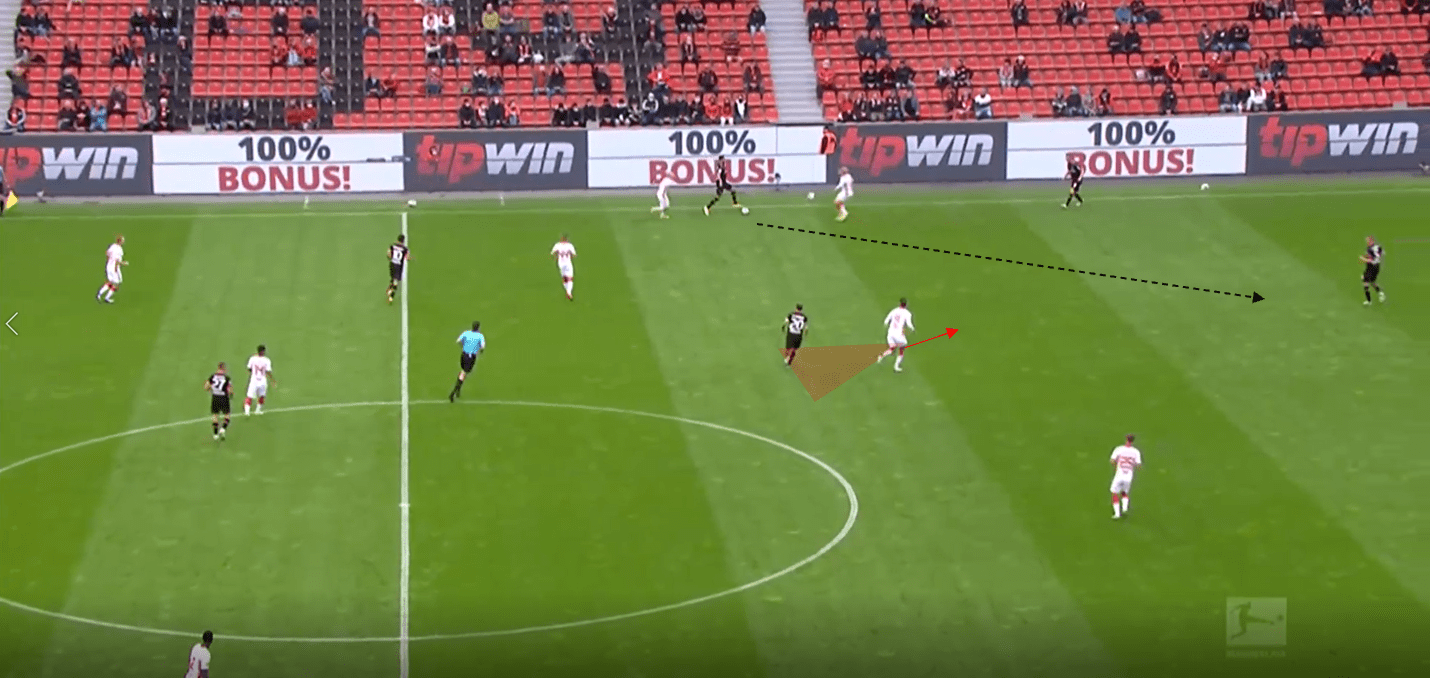

We can see another example here where Diaby is able to receive in a wide position behind the wing-back. As a result, he engages the centre back, and a lane opens up to find central striker Patrick Schick. The most attacking-minded midfielder in Leverkusen’s lineup, youngster Florian Wirtz, is then able to run beyond his midfield marker and receive behind Leipzig’s second line, where far winger Bellarabi is able to then make a run in behind.

As we’ve seen in the Leipzig pressing section, Leverkusen’s general structure was that 4-1-4-1, with that pivot often being marked as he is here. Their wingers stayed wide as Diaby does here, and so it was often the responsibility of the central midfielders to fill the half-space where possible. When the full-backs pushed higher, the wingers could tuck into the half-spaces, but Leipzig’s back five offered good protection of these areas.

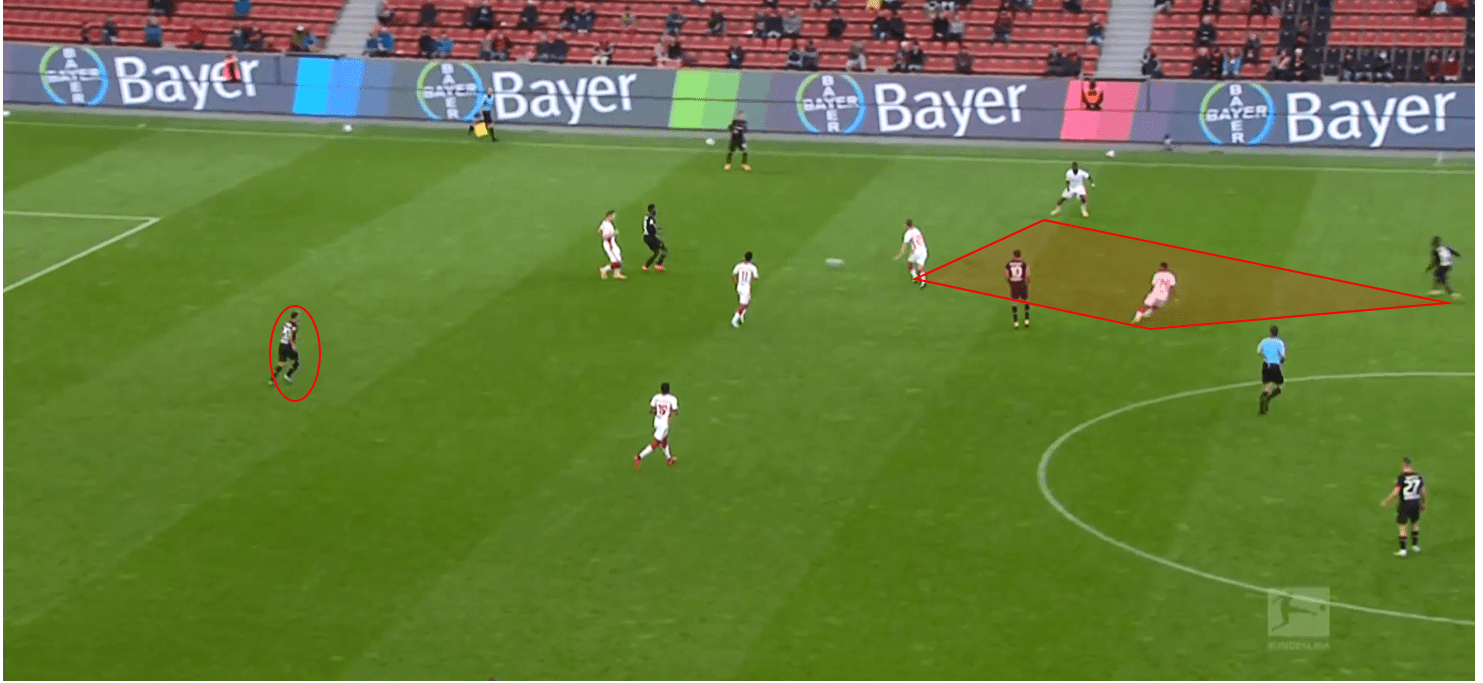

In this example below, we can see Bellarabi supplies width while far winger Moussa Diaby operates in the half-space. Florian Wirtz moves to the far side, and so Leverkusen are in more of a 4-2-4 formation, which is a common tactic used by clubs.

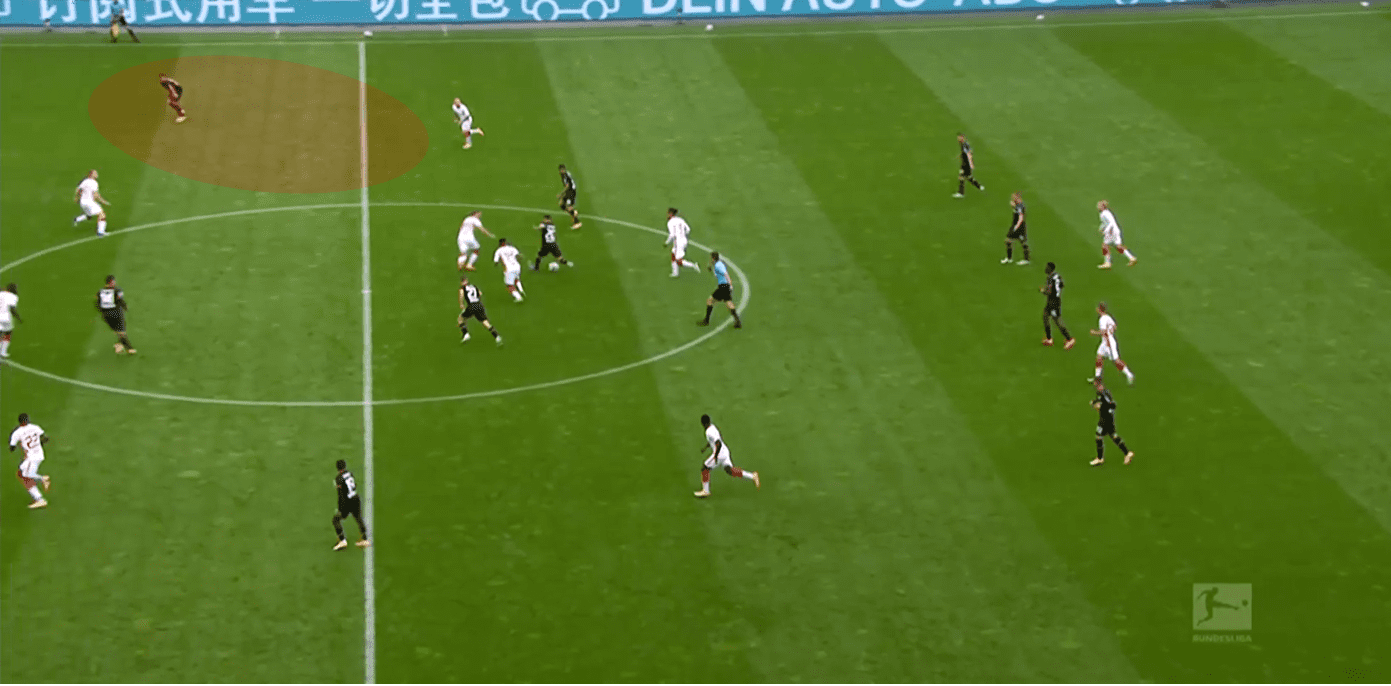

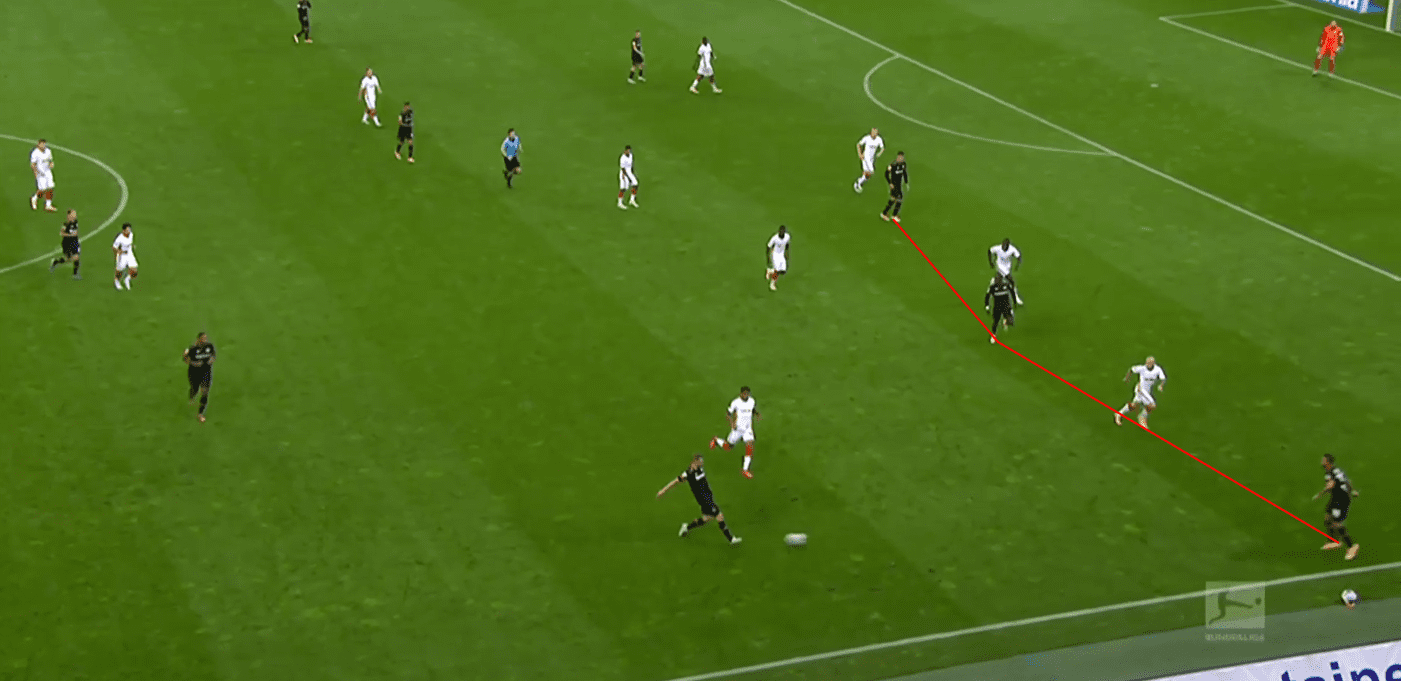

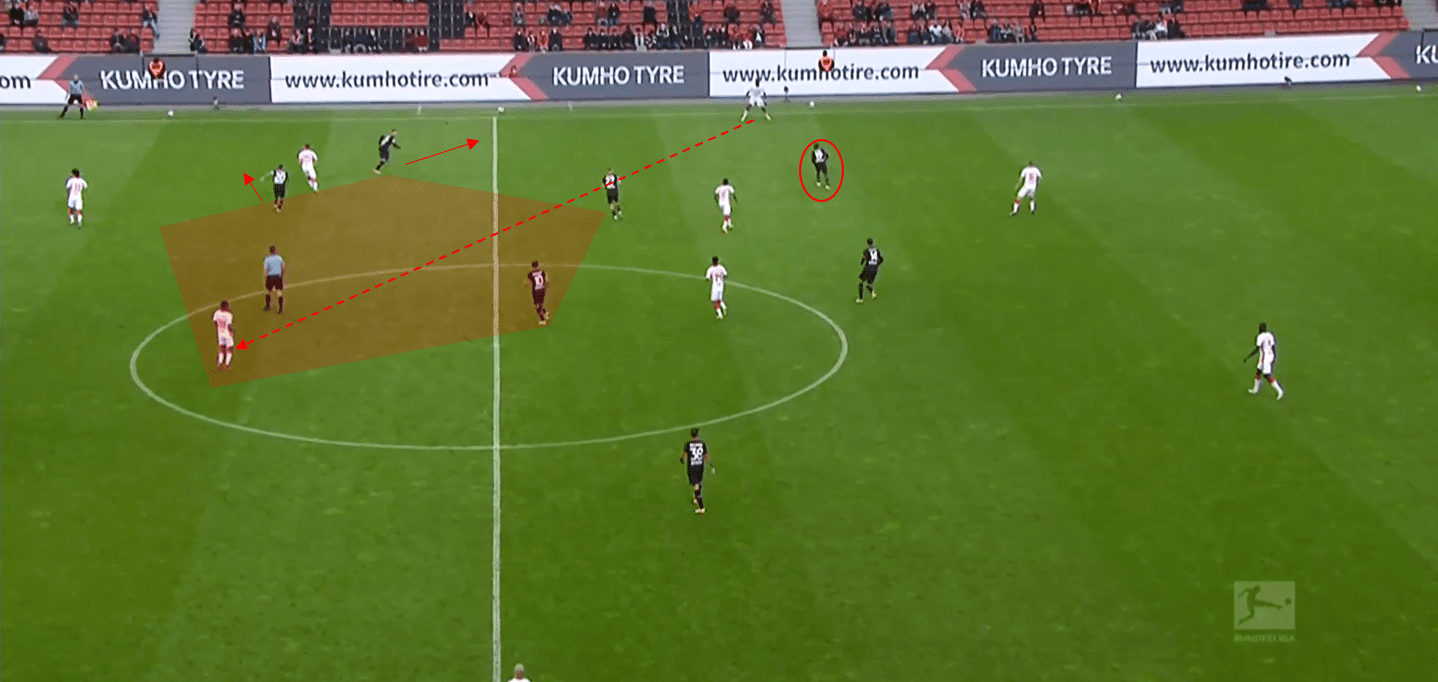

Diaby here uses a really nice piece of movement in order to allow Leverkusen to progress through the half-space, and overcome that issue of Leipzig’s back-five having such good coverage of this area. Diaby makes a deeper movement to receive the ball deeper, which causes his marker to also follow him outwards slightly to stop him receiving. Patrick Schick makes a complementary movement in behind this centre back, and Diaby’s movement opens up the lane for Schick to receive. Schick receives and curls the ball into the far corner for a goal, but he was found to be marginally offside.

Nagelsmann’s second-half adjustment

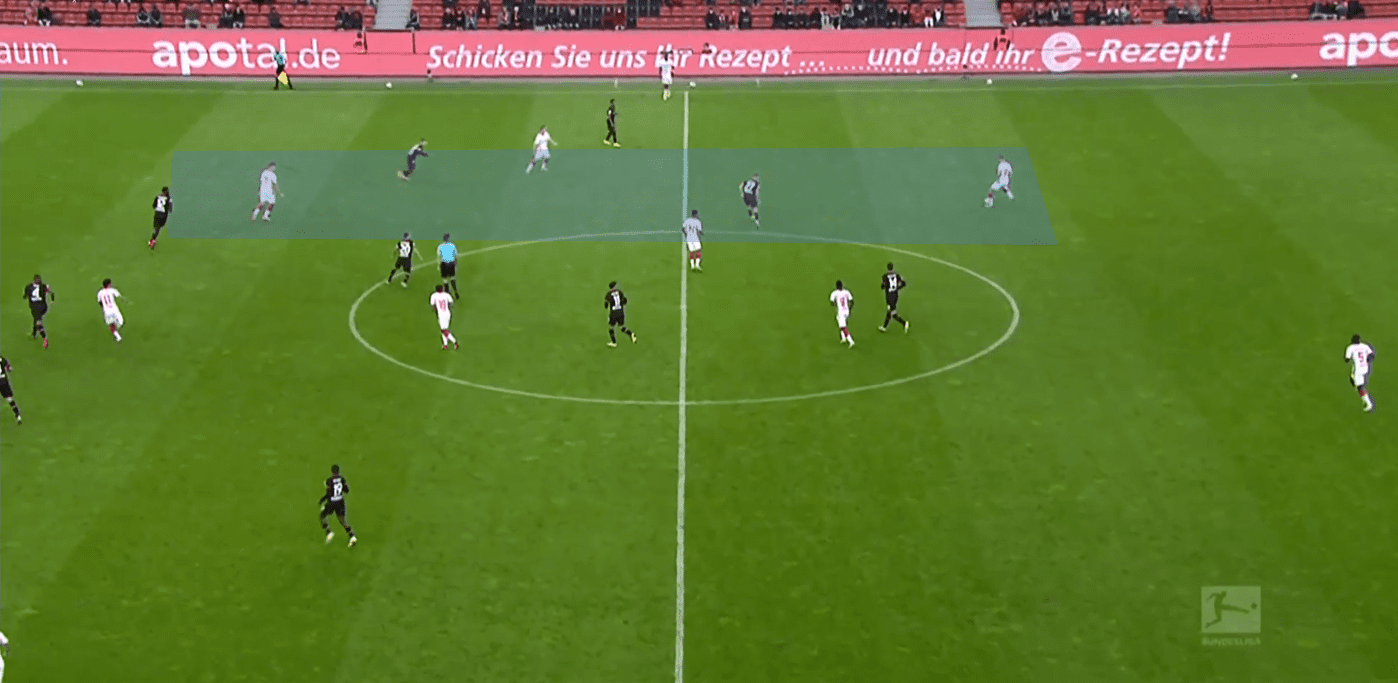

Following some of the confusion regarding their pressing at the end of the first half and Sørloth’s role, Leipzig decided to switch systems at half time and changed into a 4-2-3-1 formation. Previous right wing-back Amadou Haidara moved to central midfield while Mukiele filled in at right-back.

The thinking behind this switch to a 4-2-3-1 was simple- occupy the pivot. Following that late first-half confusion, it looked as though Nagelsmann wanted to reduce the load expected of Sørloth, as the Norweigan now had to simply press the centre-backs. Instead, fellow new signing Hwang Hee Chan was tasked with marking the pivot. The wingers would sit slightly deeper and press the full-backs when they received the ball. These changes allowed Leipzig to track the pivot in a simpler fashion, and they found success in doing so.

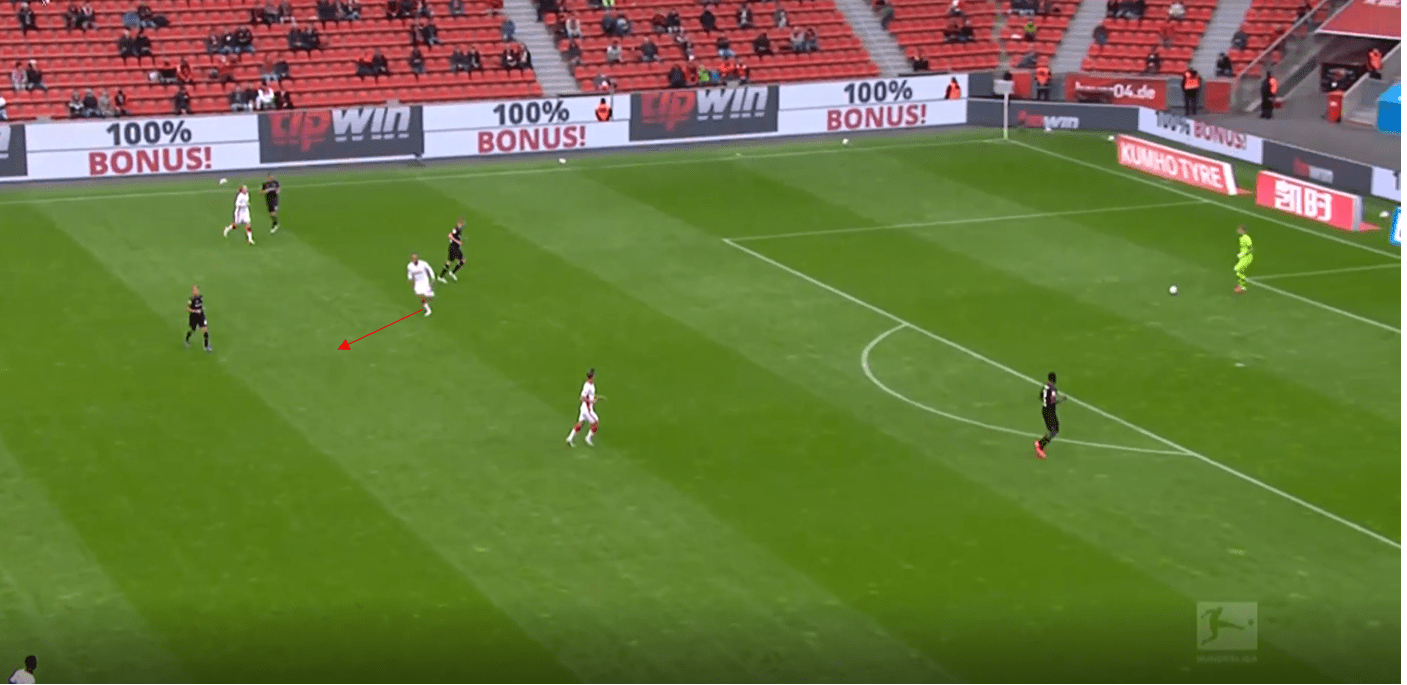

The formation naturally matches up well against a 4-1-4-1/4-3-3 with a single pivot, and so Leverkusen struggled to build again once their pivot had been cut off. We can see an example here where the striker forces the centre-back to play wide, where the Leverkusen full-back can be pressed by the Leipzig winger. The central midfielders can match up in a 2 v 2, while the back line can apply pressure to the forward line.

We can see an example here where Leverkusen’s central positioning of a central midfielder allows them access to the half-space, where Diaby is pressured from behind by a Leipzig centre-back. Despite allowing the ball through, Leipzig have enough local compactness around the ball, and so the central midfielder, winger, and pressing number ten can all close around the ball to win it back.

Leipzig didn’t seem to cover the ball near pivot so much in the second half though, as Hee-Chan seemed to be more man-oriented towards Charles Aránguiz. On a few occasions, this meant that Leverkusen were able to overload Leipzig in this area when Demirbay dropped to form a double pivot. We can see an example below where Aránguiz is covered but the ball near pivot (Demirbay) is not. Moussa Diaby does a good job of occupying Tyler Adams, and so Demirbay is free to receive and play.

This overload wasn’t too dangerous for Leipzig as such, but it allowed Leverkusen a way to bypass some of the pressure. We can see another example below where Demirbay drops as the ball near pivot to receive freely, with his marker Tyler Adams staying deeper and allowing him to receive. We can see the space behind Adams is crowded well, and the far pivot is marked, and so despite not having pressure on the ball, Leipzig are in a safe enough position.

Both teams match up, stalemate ensues

With Leverkusen setting up in a 4-1-4-1 in possession, in the second half they also went with this formation. Against Leipzig’s 4-2-3-1 build-up this allowed for Leverkusen to match up positionally, as we can see below.

We can see here Leverkusen are in that 4-1-4-1, with the central midfielders able to match up easily against the two deeper Leipzig midfielders. Leverkusen’s defensive midfielder is able to cover the half-space or attacking midfielder, while the wingers can press the full-backs.

Leverkusen’s central midfielders were fairly man-oriented, and so the half-space could open up for Leipzig at times, but much like their counterparts, they struggled to overload this area or progress through.

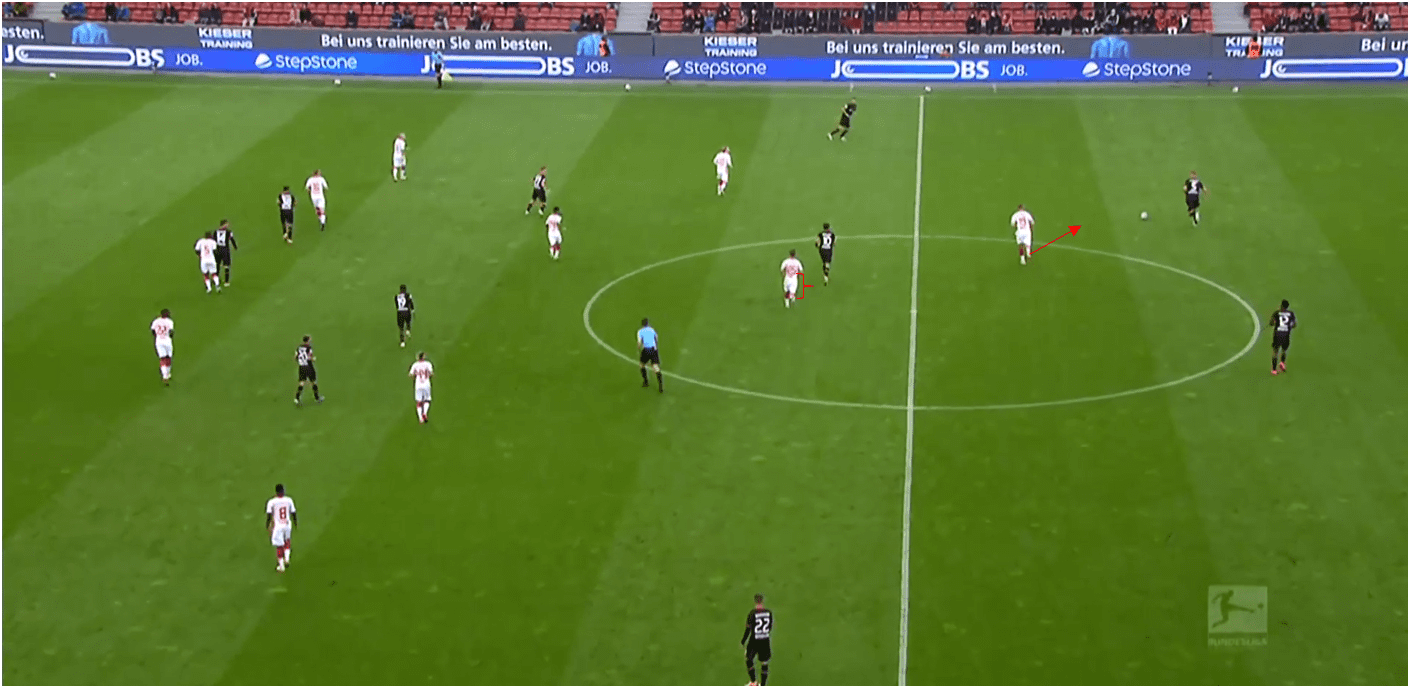

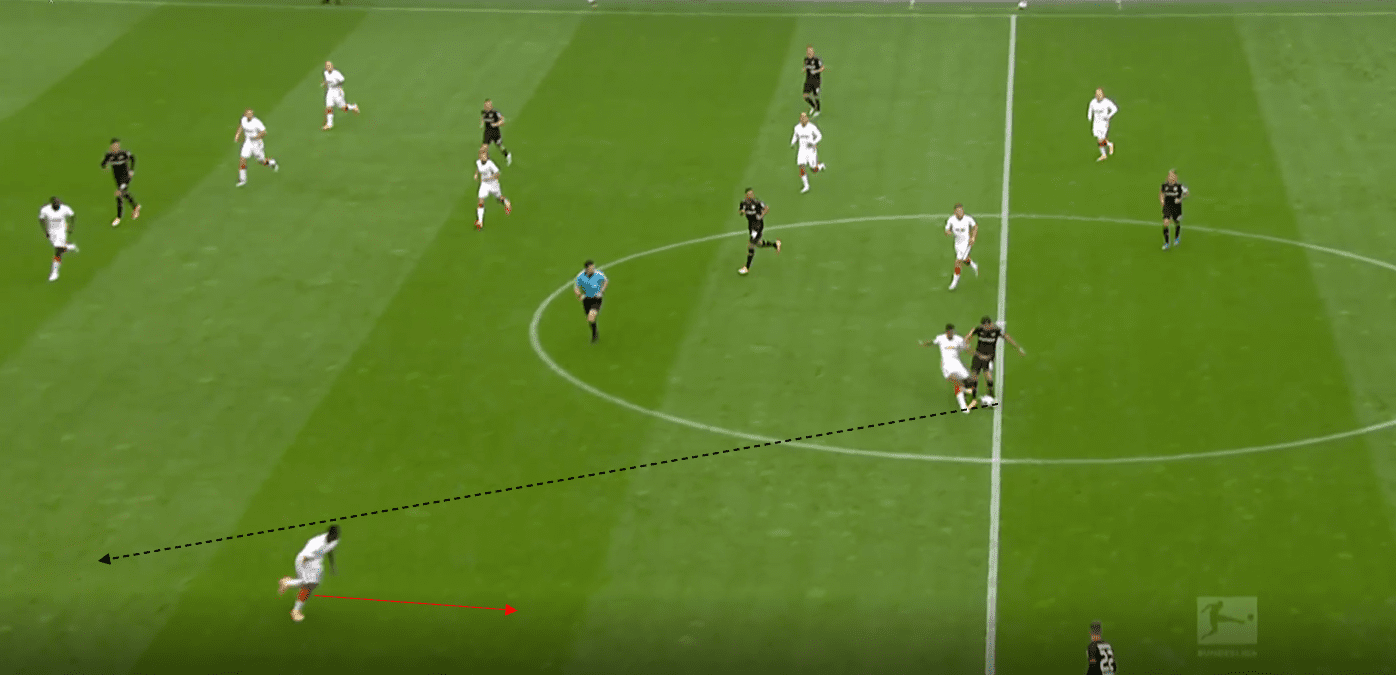

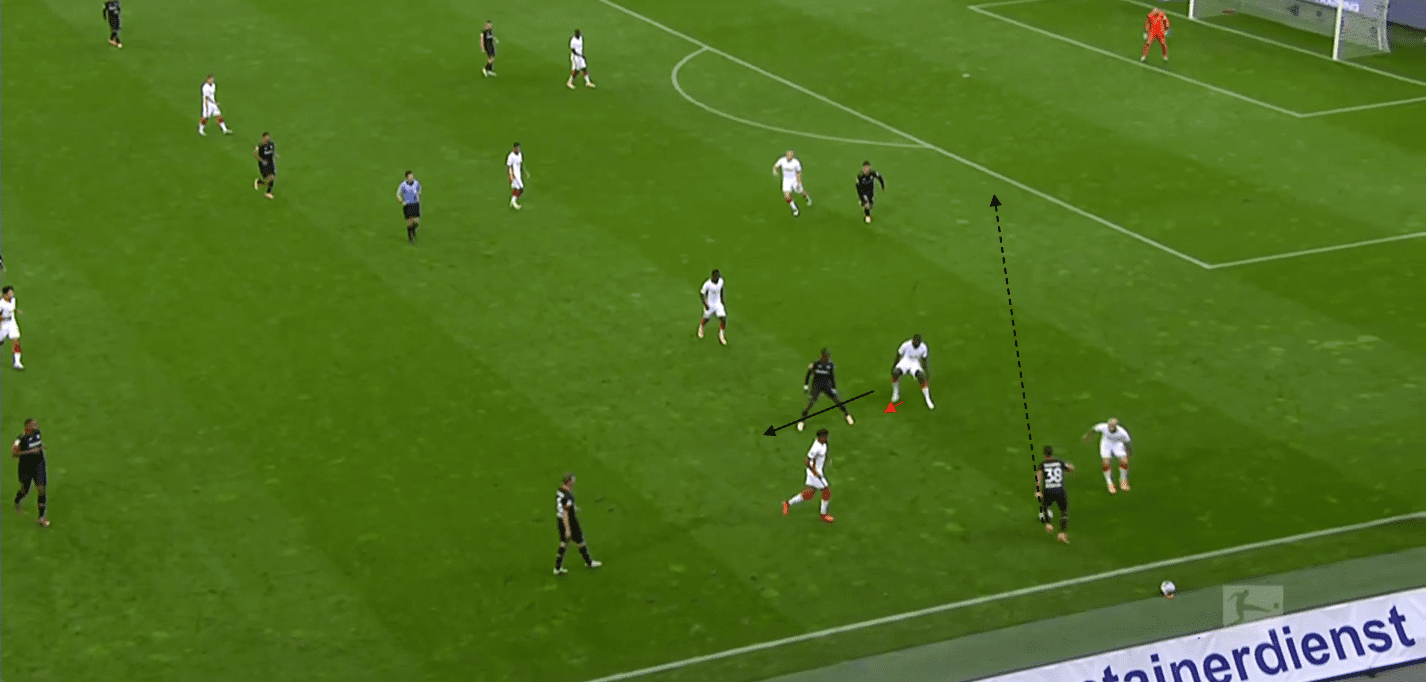

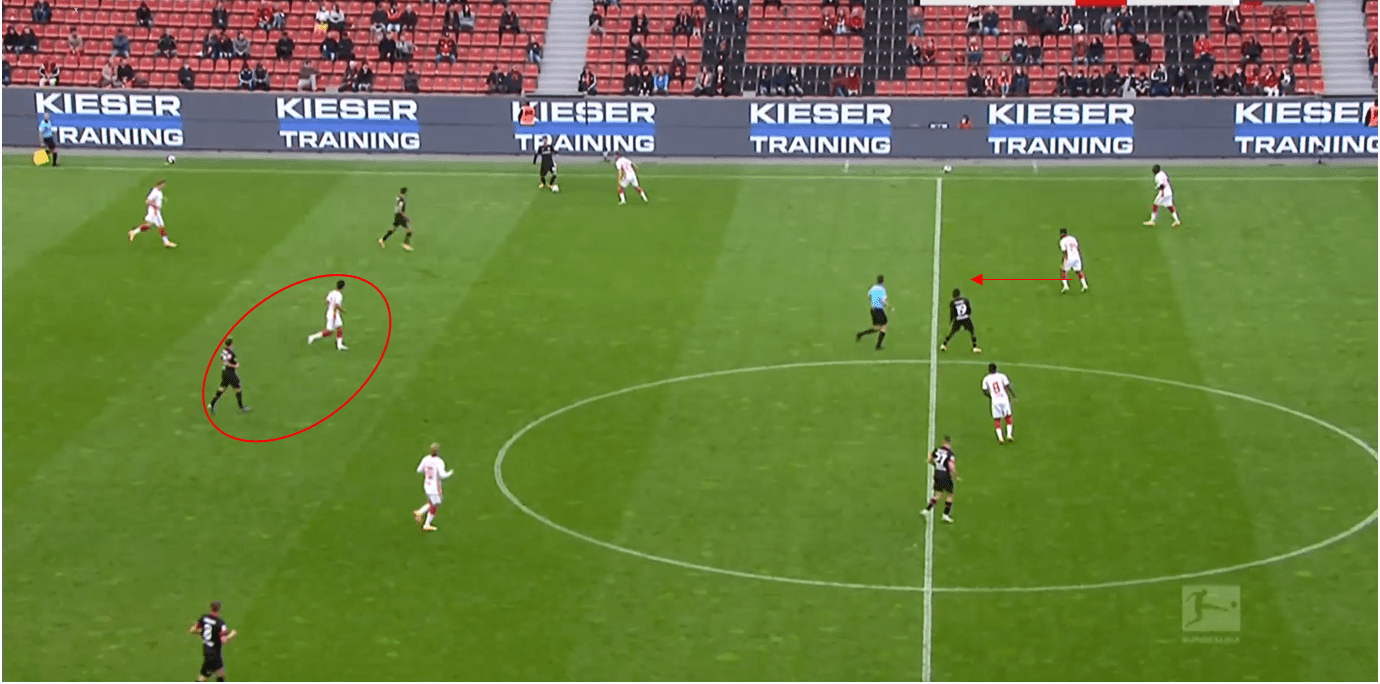

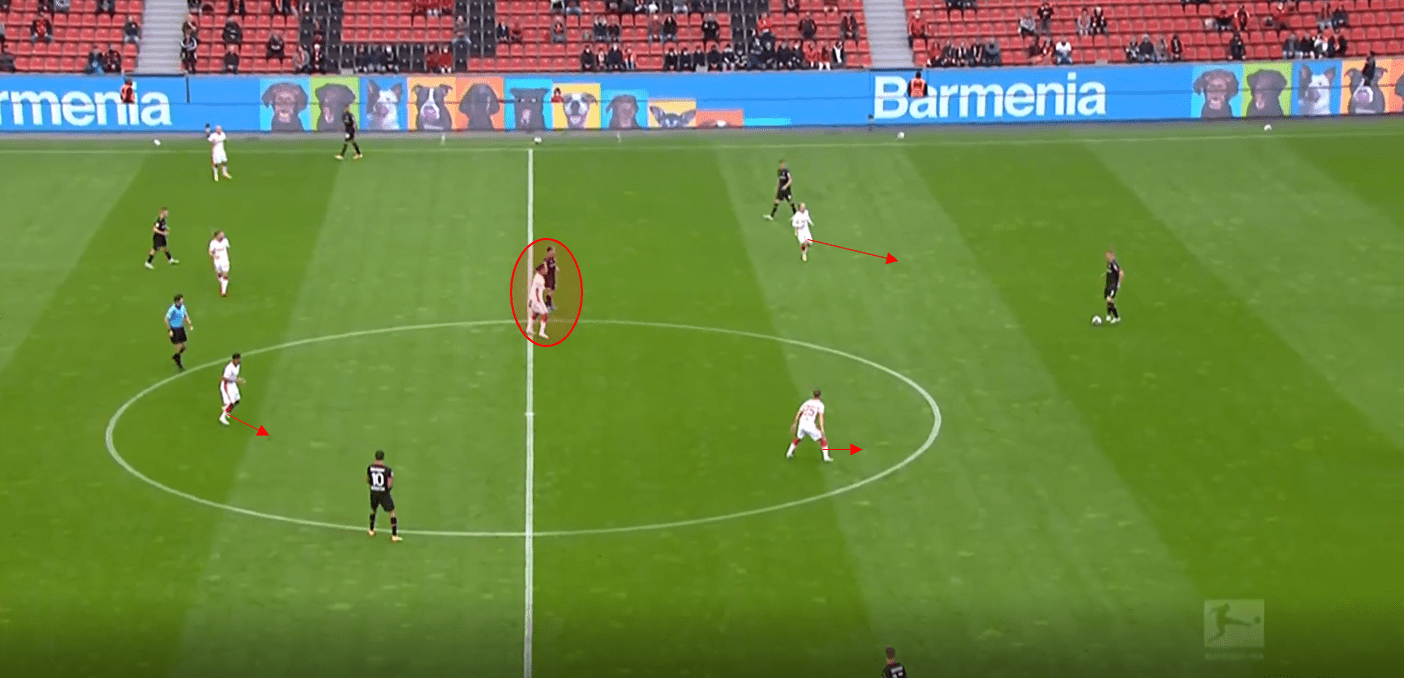

It seemed as though neither side really used enough variation in their structures in order to progress the ball consistently, and overloads were rare to come by in the game. Neither side really dropped into a back-three (from a four) in the game or used rotations often, which is rare for both these teams. Here Leipzig are able to progress the ball following a pressing error by Leverkusen. Moussa Diaby decides to move towards the centre-back, leaving the Leipzig full-back open. As a result, the Leverkusen full-back has to press forward, which in turn forces the defensive midfielder to cover him. Therefore, the central zone is left unoccupied while Leverkusen’s central midfielders are occupied, and so Nkunku is free to receive between the lines.

Because of this match-up both in and out of possession, the game became a lot about how you can create space to receive away from your marker, and so dynamic space occupation was often seen as the most successful ball progressor, as we’ve already seen in some examples already. We see here Olmo plays the ball to the full-back before moving forward and receiving in the unoccupied half-space, where he now has good body orientation to play forwards.

Conclusion

With the game fairly even and both sides nullifying each other’s tactics well, a 0-0 scoreline probably would have been appropriate, but it was individual quality in both sides’ goals that allowed them to score, with Poulsen and Forsberg combining for the UEFA Champions League semi-finalists’ goal while Demirbay smashed a shot past Gulacsi from distance. Neither side will be displeased with the result, although they may be ever so slightly upset with their team’s performances in possession. It is always fun and tactically interesting to watch Nagelsmann manage a game in which his side has less of the ball, and this game was no different.

Comments