The top two Bundesliga sides met on Saturday as RB Leipzig traveled to Munich to take on Bayern Munich. What promised to be an exciting match delivered exactly that, ending in a 3-3 draw that saw Bayern with 68% of the possession but just managing to find one more shot than Leipzig.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics used by both Bayern Munich and RB Leipzig. It will also provide analysis of Leipzig’s attack on Bayern’s centre-backs, Leipzig’s defensive structure, and Bayern’s attack through the half-space from the wide areas.

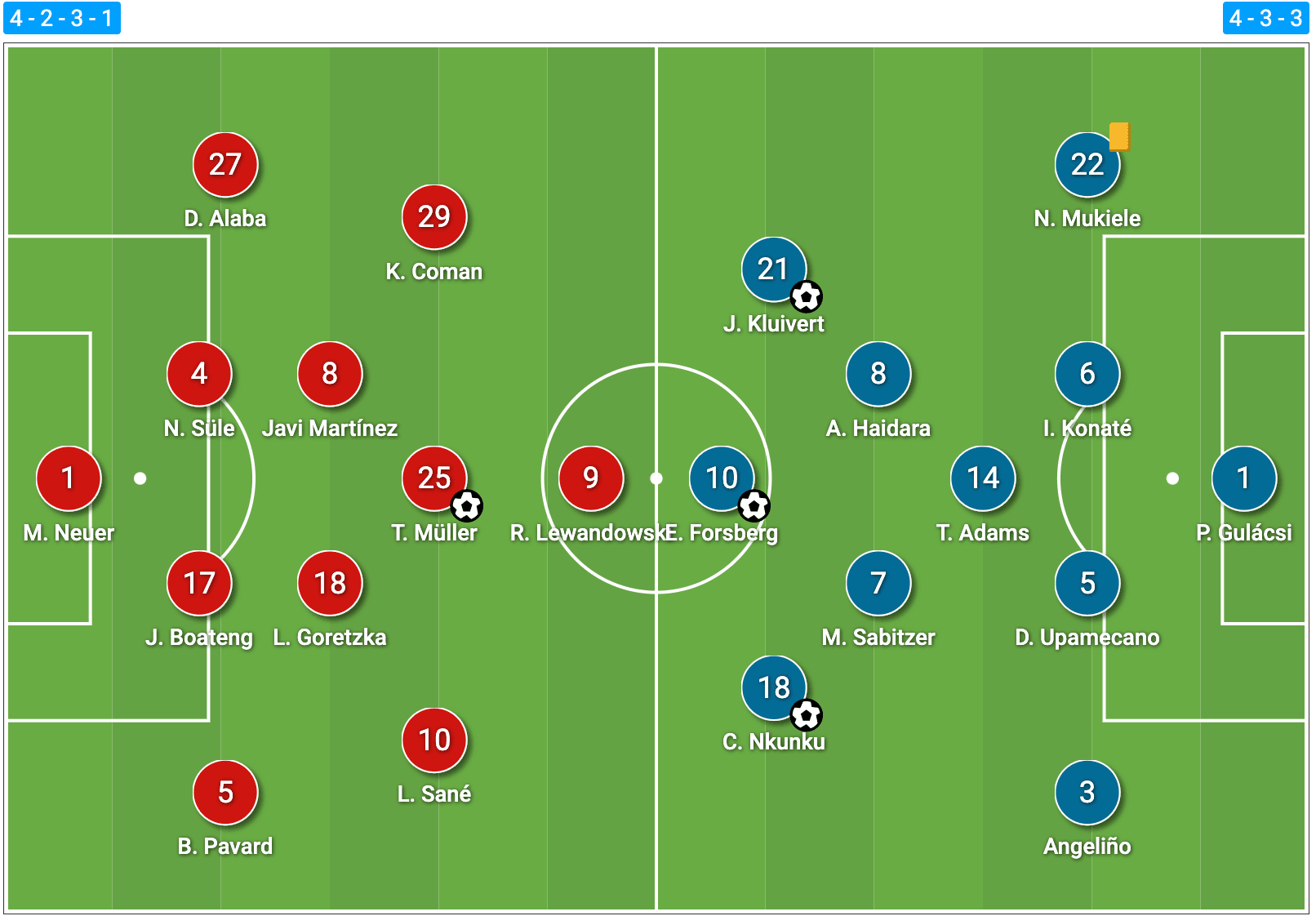

Lineups

Hansi Flick sent Bayern out in their usual 4-2-3-1 with Manuel Neuer in goal. Bayern’s backline consisted of David Alaba, Niklas Süle, Jérôme Boateng, and Benjamin Pavard. Leon Goretzka and Javi Martínez started as the defensive midfielders, although Martínez was subbed off early in the match due to injury, replaced by Jamal Musiala. Thomas Müller started in front of them with Leroy Sané to his right and Kingsley Coman to his left. Robert Lewandowski started as Bayern’s striker.

Julian Nagelsmann’s structure looked like a 4-3-3 that had Péter Gulácsi in goal. Ibrahima Konaté and Dayot Upamecano started as centre-backs, with Angeliño as left-back and Nordi Mukiele as the right-back. Tyler Adams started as the defensive midfielder with Marcel Sabitzer and Amadou Haidara in front of him. The front three consisted of Christopher Nkunku, Emil Forsberg, and Justin Kluivert.

Leipzig looked to attack Bayern’s centre-backs

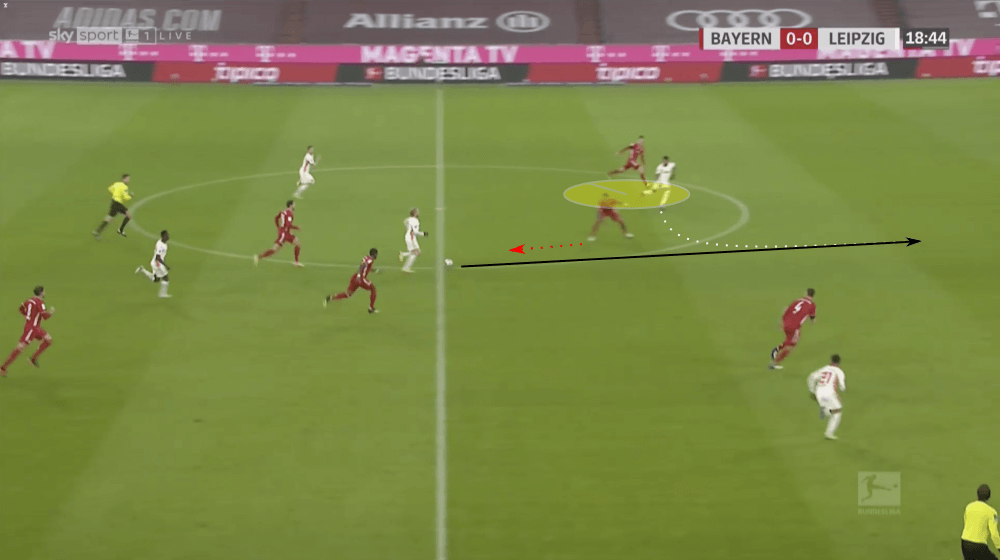

Bayern’s consistent high line and high press makes them vulnerable at the back because they commit so many men forward to win the ball higher up the pitch. Leipzig looked to target this by using their wingers (Nkunku and Kluivert) to occupy the space between the Bayern centre-backs and their corresponding outside-backs. This positioning, combined with Forsberg dropping down off of Süle and Boateng allowed Leipzig to get in behind.

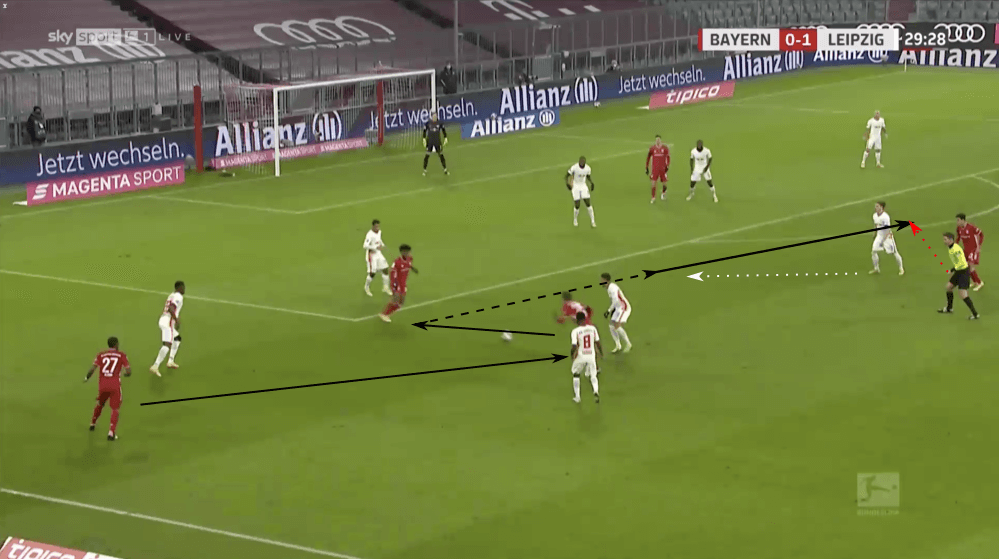

Here’s the image just before the first goal of the match, scored by Nkunku. Leipzig had been building up, lost possession, and then regained it, quickly looking to attack and get up the pitch. Forsberg, the man on the ball, had received a pass between the defensive lines of pressure. He’s unmarked by the centre-backs because Boateng knows not to commit and Süle was pinned by Kluivert wider than he should have been. This pinning allowed the space to open up for Nkunku. As Boateng stepped forward, Nkunku began his run behind him, staying onside before curling towards goal. Despite Neuer’s best efforts, Nkunku coolly dribbled by him and passed the ball into the net for the 1-0 lead.

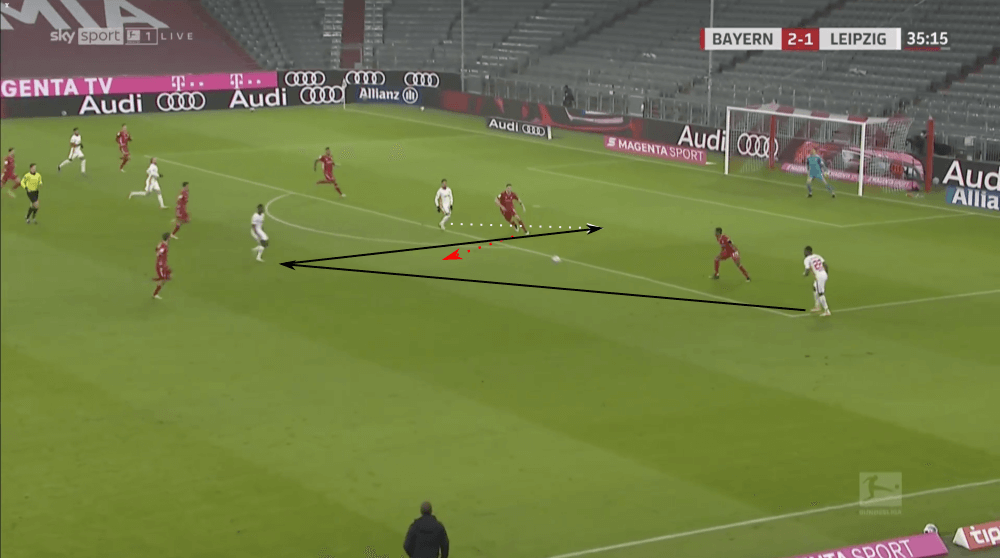

Leipzig’s second goal also came as a result of them attacking Bayern’s centre-backs, particularly with their speedier players. The controlled chaos that Leipzig builds can be overwhelming for defenders, causing them to make split-second decisions.

That forced quick decision-making is exactly what happened to Süle. A quick switch of the field found Leipzig in a 3v2 advantage. Mukiele played the long switch with his first touch, laying the ball off for Haidara. The pass was less than perfect, and it seemed like it could be intercepted. Accordingly, Süle stepped forward to do so. However, Haidara had the dynamic advantage, and he was able to play his first touch to Kluivert, who settled the ball and curled it into the back of the net. Süle’s step forward opened up the space for Kluivert to run in behind, making almost the same directional run that Nkunku had done for his goal. Again, Bayern’s centre-backs had stepped up and gotten burned.

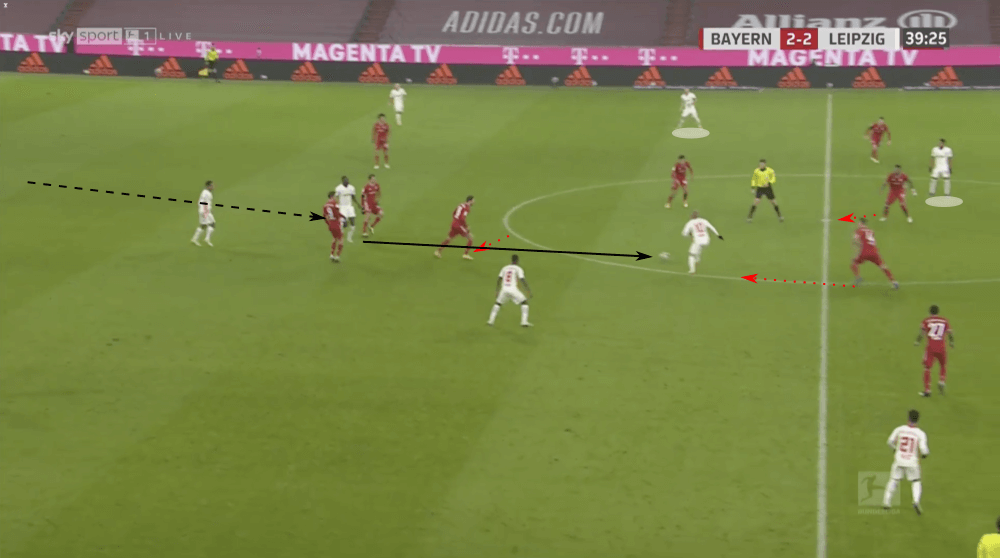

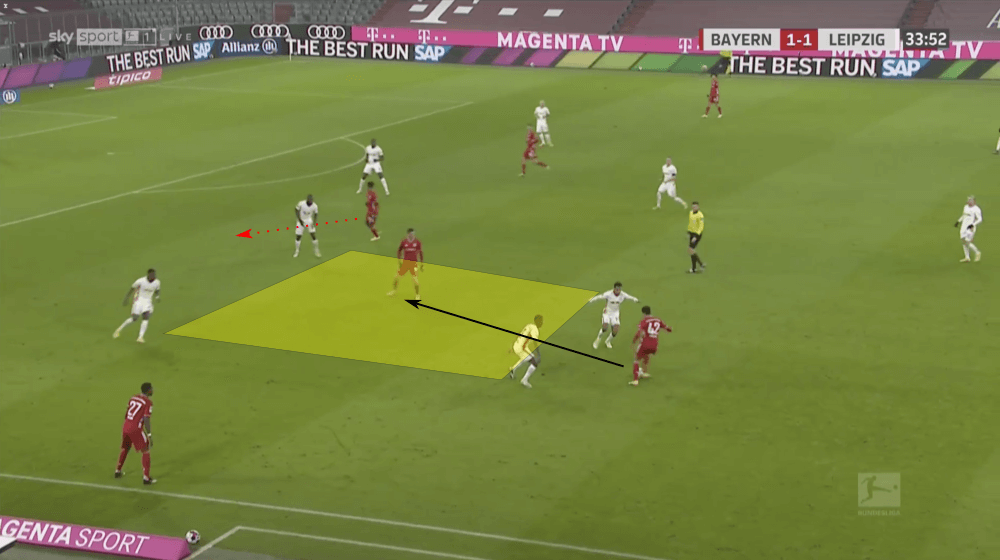

Even in their build-up, Leipzig clearly targeted Süle and Boateng. While Forsberg didn’t play as a total false 9, his ability to drop off of them created problems between the two.

In the instance above, Upamecano dribbled forward into Bayern’s midblock. He dribbled to attract pressure, and when he finally was able to get Goretzka to step out of position, he was able to find Forsberg’s feet. Once again, Forsberg had dropped off of Süle and Boateng. Despite Nkunku being offside, Leipzig’s intentions are clear. They’ve overwhelmed (via numerical advantage) the right-back Pavard, which would allow Nkunku to make his run in behind. Both Boateng and Süle are focused on Forsberg, meaning Nkunku is in alone if he can stay onside. What’s nice for Forsberg is that his pass doesn’t even need to be perfect because there is so much room in behind.

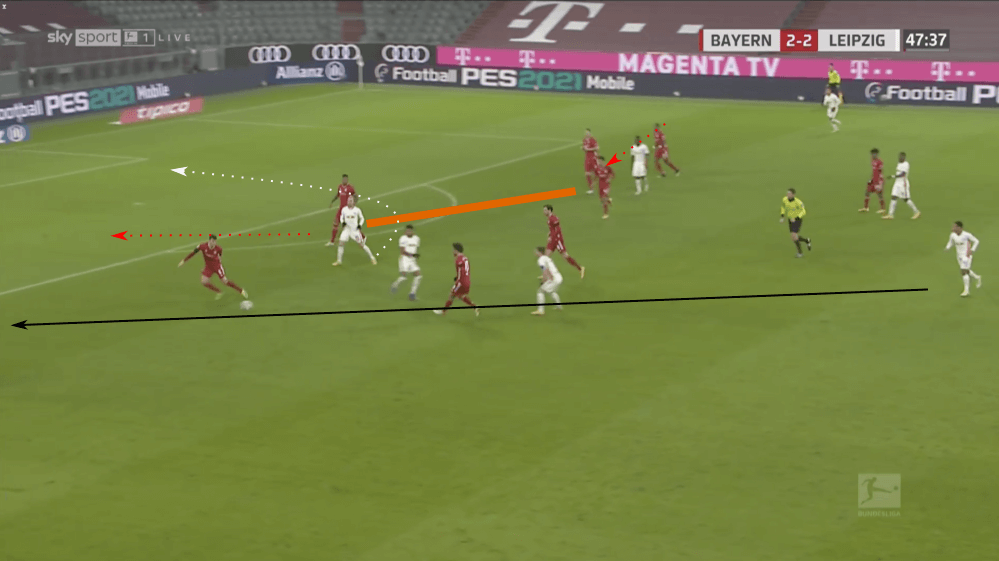

Leipzig’s final goal was also the result of them manipulating Bayern’s centre-backs. This time, they were able to get Süle out of position again, causing a wide gap to open up between the two centre-backs.

Süle was dragged out on the left side by Haidara as Alaba defended Mukiele. A quick switch via Adams saw Süle and Alaba trot back towards their own goal. The gap between centre-backs is marked in orange. Süle was mostly at fault here, but so was Boateng, who was unaware how much room was behind him. He went to defend the near post, and Forsberg curled his run into the space behind him, finishing off the cross and restoring Leipzig’s lead in the process.

Leipzig look to prevent vertical entry to half-space

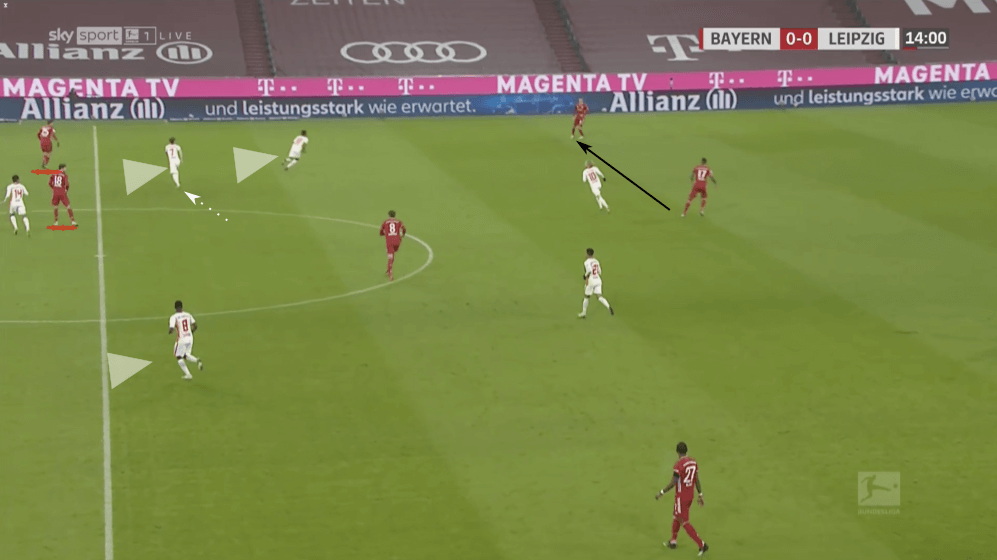

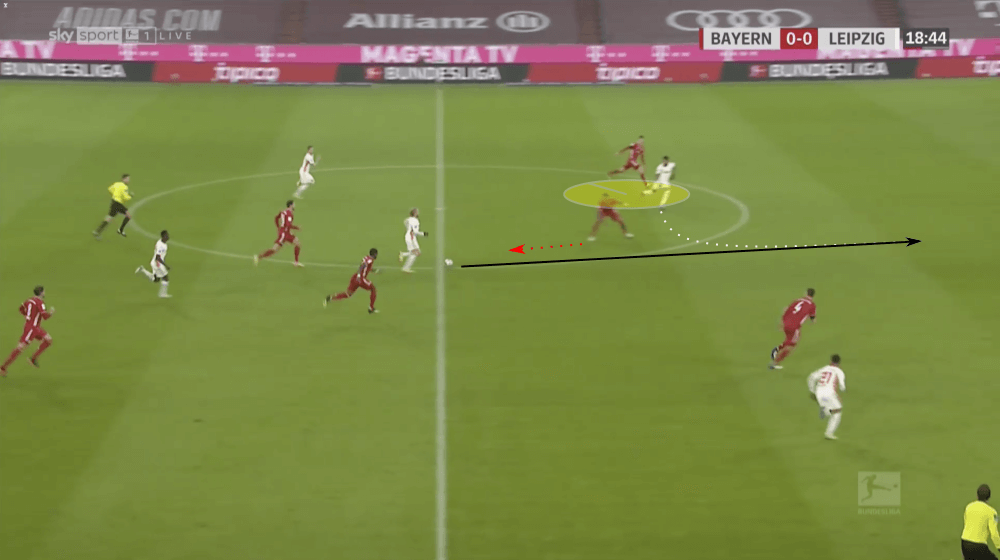

Leipzig also had a strong defensive plan for attempting to slow down Bayern’s high-flying attack, and that was to set up to prevent passes from their centre-backs or defensive midfielders into the half-space. Bayern almost always look to build through them from the centre of the pitch, and so Leipzig looked to push them wide and prevent this.

In the image above, Leipzig are defending in their mid-block in a 4-3-3, with Adams sitting underneath Sabitzer and Haidara. Sabitzer and Haidara’s main role is to deny those vertical passes, using their covershadows to prevent the passes from being an option. As the ball moved from left to right, Adams would switch over to either mark a Bayern midfielder (Goretzka in this instance) or to close down the space to prevent those interior passes. This blocked any central entry and forced Bayern to try and go wide. As they covered those passing options, Nkunku, Forsberg, and Kluivert worked together to pressure Bayern’s back four. In this instance, Nkunku waited for the pass to be played before pressuring Pavard, who was forced to send the ball back to Boateng.

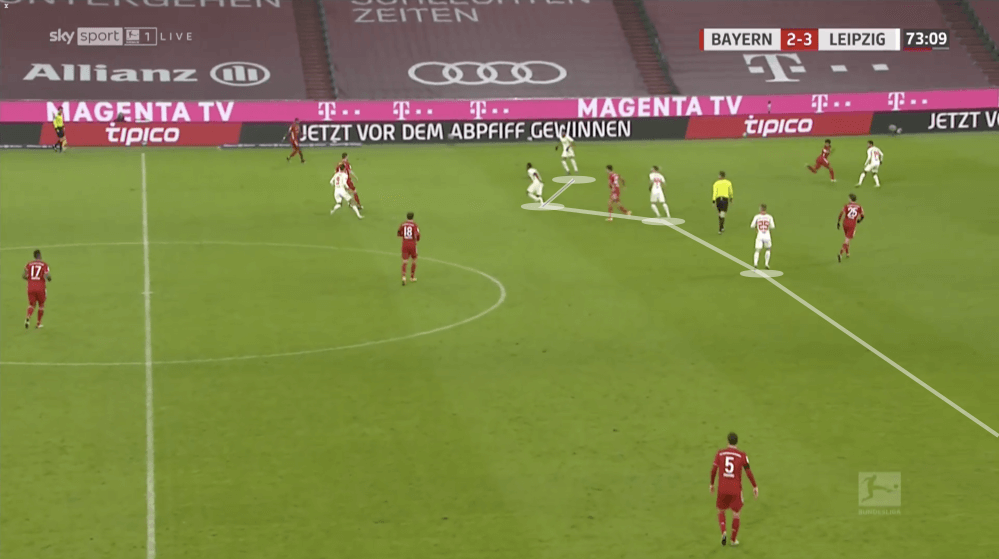

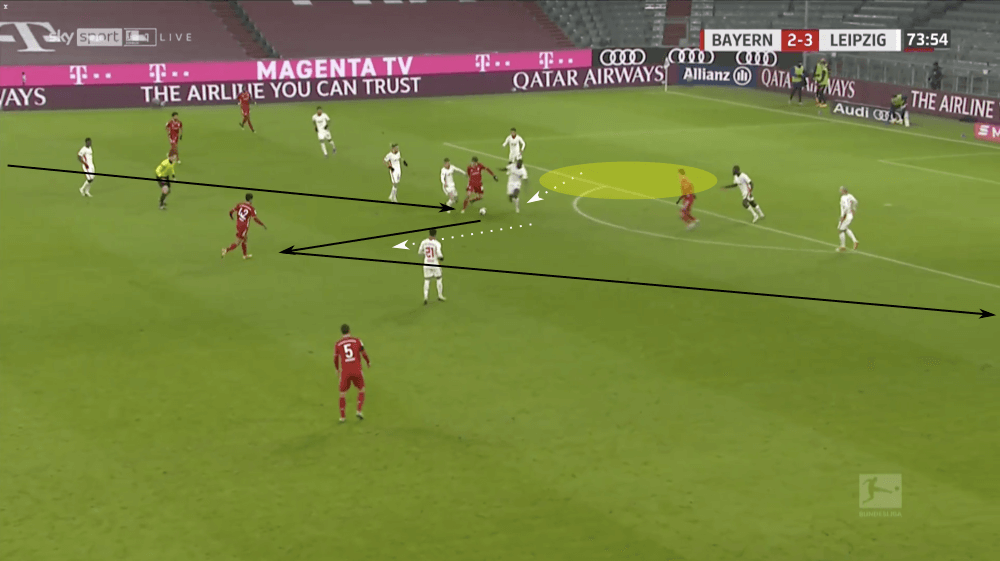

After taking the lead in the second half, RB Leipzig opted for more of a 4-5-1 formation, with the main goal of denying entry into the half-space.

In this defensive structure, Kluivert and Nkunku dropped down and provided more defensive support as Leipzig attempted to deny Bayern entry into the half-space. Above, the number of Leipzig players protecting the half-space is highlighted. Four of the five defenders in the midfield chain shifted over in order to prevent any vertical pass. Musiala, Müller, and Coman recognised this and had to make runs away, forcing Bayern to recycle possession.

At one point in the match, Leipzig failed to prevent one of these vertical passes into the half-space. Both Haidara and Adams hesitated to pressure Musiala as he dribbled towards them.

The result of their hesitation allowed the passing lane to remain open. Musiala was able to find Lewandowski with his pass, who had time to turn and face Upamecano, who was closing him down. Lewandowski megged Upamecano and found Coman’s run in behind him. This was followed by another run (this time by Müller) behind a defender, although this time it was Ibrahima Konaté who was pressuring Coman. Coman found Müller who buried the chance and briefly gave Bayern the lead. The previous example shows why Leipzig was so focused on forcing Bayern wide. Within seconds of finding Lewandowski in the half-space, Bayern had the ball in the back of the net.

Bayern play through half-space from wide area

Because their vertical entry to these spaces was denied, Bayern was forced to try and find access to the half-space from the wing. Leipzig’s defensive structure worked for the most part, but the problem is that it’s difficult to prevent Bayern from accessing that space at all. And so Bayern’ first goal is a result of them accessing the half-space from their horizontal movement.

David Alaba was in possession on the left flank and actually had to play a diagonal ball back to Müller, who was in the half-space with Coman. Müller played the ball into Coman’s feet, and made an overlapping run. While Adams didn’t follow Müller, he also wasn’t able to pressure Coman properly. This led to Sabitzer sliding down to do so, which became a problem because space had opened up in the centre of the pitch on the edge of the penalty area. Coman slotted a pass back to Musiala, who was able to bury the chance with a well-struck shot.

On Bayern’s final goal, the initial pass into Müller came from Süle, who was positioned much wider than normal. This was a direct result of Leipzig’s defensive setup. Süle’s pass came from the edge of the wing and was played before Leipzig had an opportunity to completely slide over and prevent access to the centre of the pitch.

The significance of where Müller received the ball should not be understated. By being able to receive in the dynamic half-space, Müller was able to draw out Konaté, who pressured Müller and then Musiala. Musiala moved the ball quickly to Coman, who curled in a cross to the back post, where Müller was able to out jump Adams on the back post. Had Müller not received the ball where he did, Leipzig would have had the 6’4” Konaté on the back post rather than the 5’9” Adams. Bayern’s passing and movement in and through the half-space is meant to engage defenders and force them to make decisions. Just as Bayern’s centre-backs committed, so did Leipzig’s, and both teams were clinical enough to finish off those chances.

Conclusion

All in all, the six goals led to one of the most entertaining matches of the weekend. The draw allowed RB Leipzig to remain in second place, two points behind Bayern and two points above Borussia Dortmund. Leipzig have a huge match on Tuesday as they take on Man United in the UEFA Champions League. If they want to control their own fate in that competition, Leipzig need a win. Bayern, having already won their group, will finish up group play against Lokomotiv Moscow.

Comments