The Bundesliga returned after the international break and league leaders Bayern Munich took on Werder Bremen on Saturday in a battle between two teams that have had very different seasons last year. Bayern went on to win the treble while Werder staved off relegation; however, Werder have found more success at the start of this year. That success continued on Saturday as they held the reigning UEFA Champions League winners to a 1-1 draw.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics used by both Hansi Flick and Florian Kohfeldt. The analysis will look at how Bayern overloaded the half-space, how Werder looked to pull Bayern up the pitch to exploit space in behind, and how Bayern tried to take advantage of Werder’s compact defensive structure by playing forward crosses.

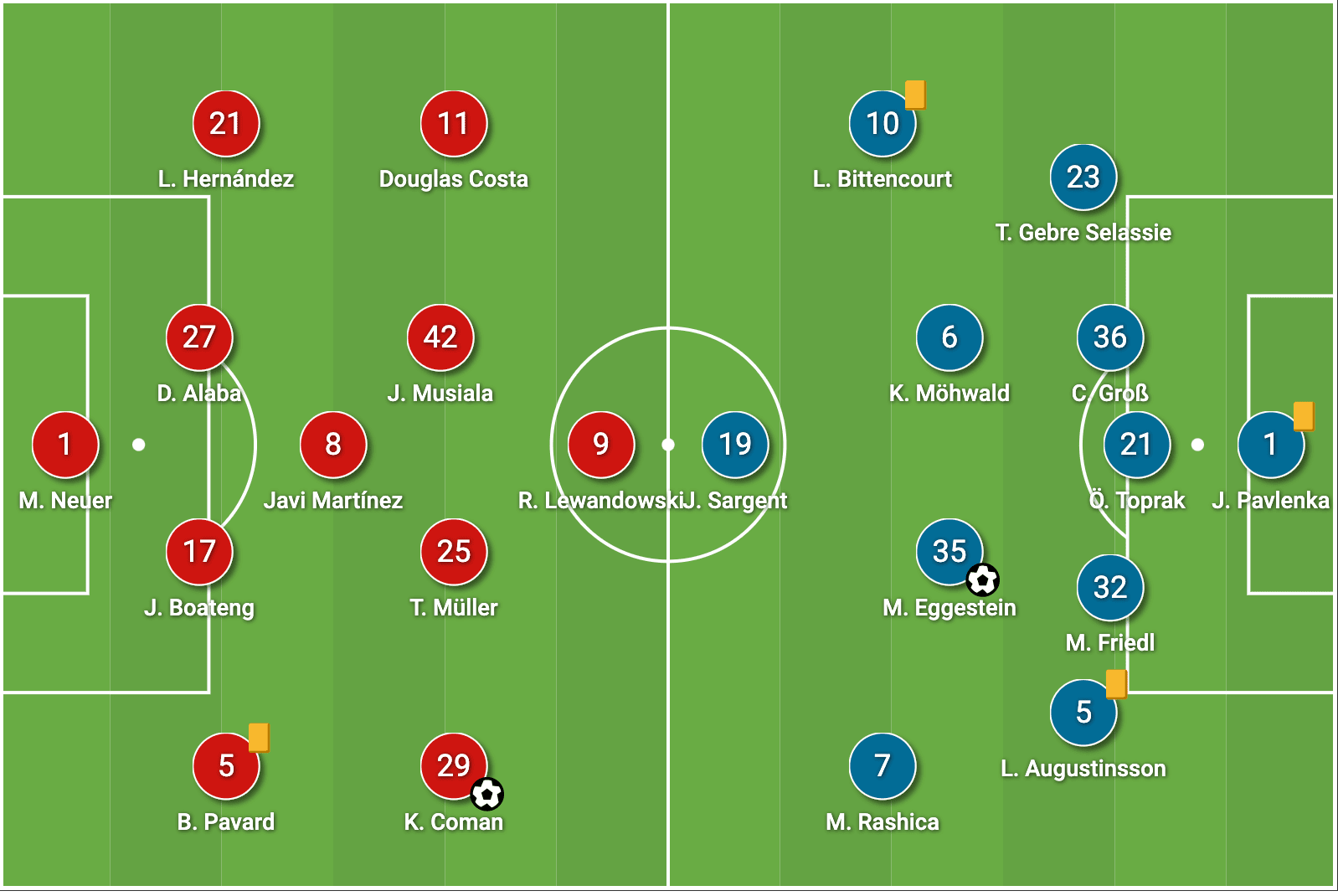

Lineups

Hansi Flick sent Bayern out in a 4-1-4-1, although it primarily functioned as a 4-3-3. Manuel Neuer started in goal with David Alaba and Jérôme Boateng as his centre-backs. Lucas Hernandez started as the left-back while Benjamin Pavard started on the right side. Javi Martinez started as the holding midfielder with Jamal Musiala and Thomas Müller in front of him. Douglas Costa and Kingsley Coman started on the left and right flank respectively, with Robert Lewandowski starting as the striker.

Kohfeldt started Werder in defensive 5-4-1 formation with Jiří Pavlenka in goal. Marco Friedl, Ömer Toprak, and Christian Groß started as centre-backs with Ludwig Augustinsson as the left wing-back and Theodor Gebre Selassie as the right wing-back. Werder’s two central midfielders were Maximilian Eggestein and Kevin Möhwald. Milot Rashica started on the left flank as Leonardo Bittencourt started on the right, and both players looked to support their striker, Josh Sargent.

Bayern overload half-space to encourage man-marking

There are many different ways that Bayern can hurt you. They have incredible qualitative advantages, as well as a quick counter-attacking ability after winning the ball in their attack half. One of the best aspects of their attack is their ability to attack half-spaces. Against Werder, Bayern looked to overload the half-space positionally. This would result in Werder committing more men into the area, forcing them to behave more as man-markers than their man-oriented zonal defending. As a result, Bayen created more space for them to attack.

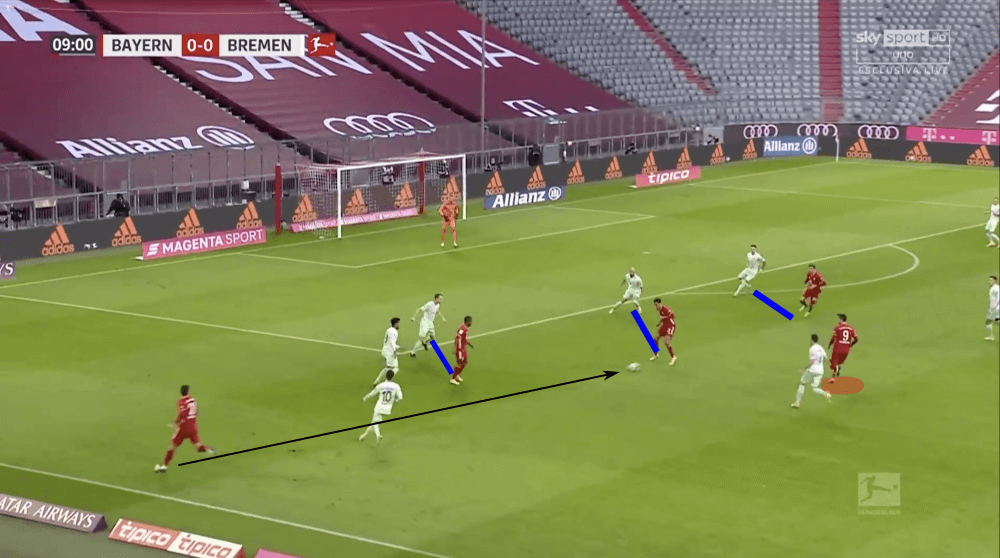

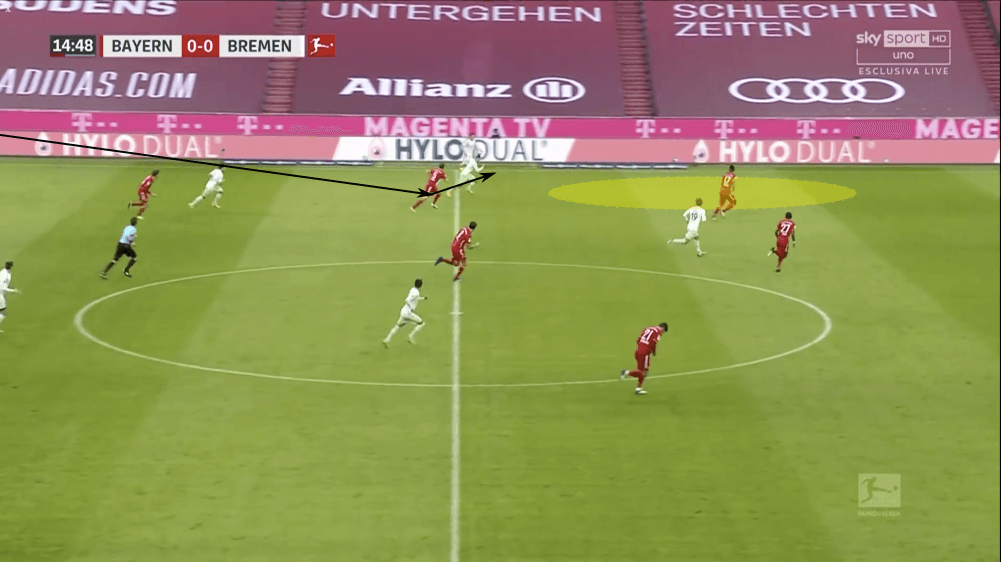

The example above shows their decision to overload that half-space. As a result of this, the Bayern players have drawn the attention of these individual players, causing them to be more focused on defending the player and not the space. In the instance above, Musiala actually dummied the ball, meaning that Toprak didn’t need to step up and pressure. If Musiala would have received the ball properly, he would have forced a decision out of Toprak with an extra man (Lewandowski) available to make a run in behind.

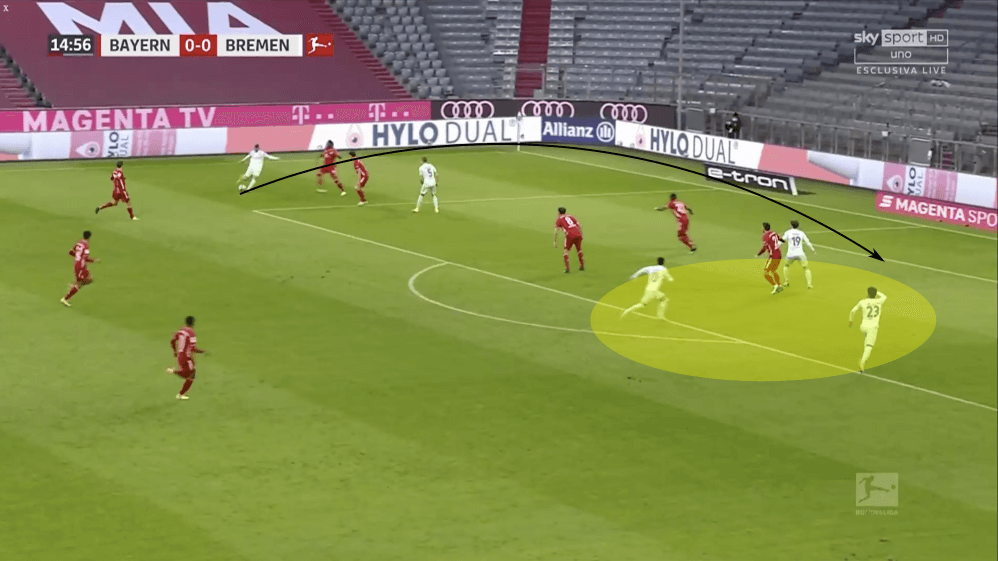

Here’s another image where it’s clear Bayern are looking to pin defenders in order to open up space. As they looked to build up on the right side of the pitch, they used their right winger (Coman) to provide width. Two centre midfielders, Jamal Musiala and Thomas Müller, occupied Werder’s centre-backs. Behind them (and not in the image), Robert Lewandowski was reading the play to see what runs he could make. In this instance, Musiala had drawn the attention of Toprak. This meant that Werder’s line was higher up the pitch. Lewandowski would have been able to exploit this with a run in behind, but Coman was unable to receive the ball while facing forward, and he was forced to play backwards as a result.

Werder’s commitment to send men into the half-space worked for them, as they held Bayern to one goal. However, this resulted in them allowing space to open up consistently and just trusting that teammates would arrive in time to halt the Bayern attack.

Towards the end of the first half, another example of how Bayern looked to do so appeared. This time, Alaba (who had rotated with Costa) and Müller made runs through the half-space. Alaba’s diagonal run and Müller’s vertical run created space behind them. This allowed a large amount of space to open up for Musiala, who was unable to position himself properly to receive the ball. Musiala actually struggled to identify the open space at all, and he instead opted to check back and receive a horizontal pass from Costa, which ultimately ended up with him playing the ball back to Boateng.

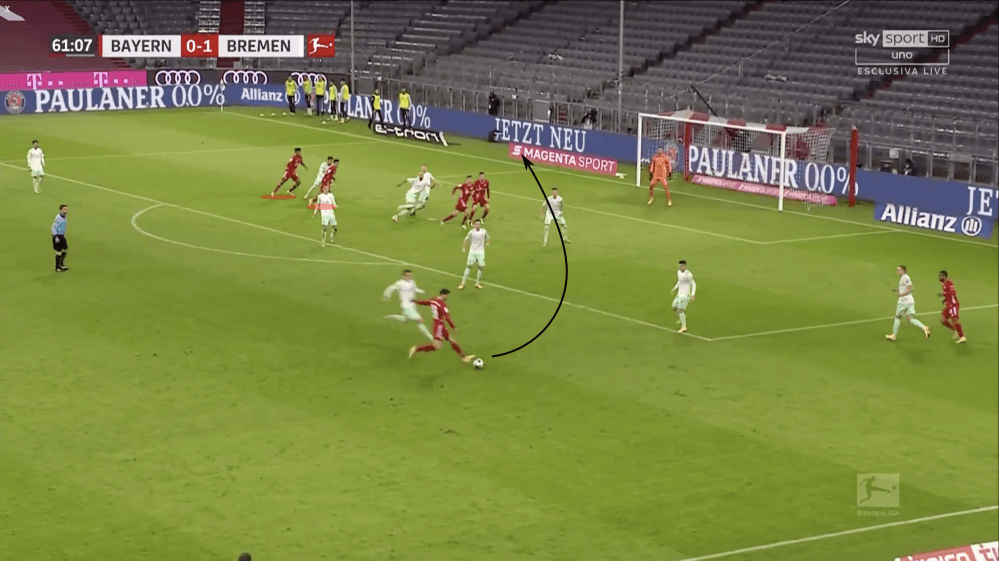

Werder looked to pull Bayern high up the pitch

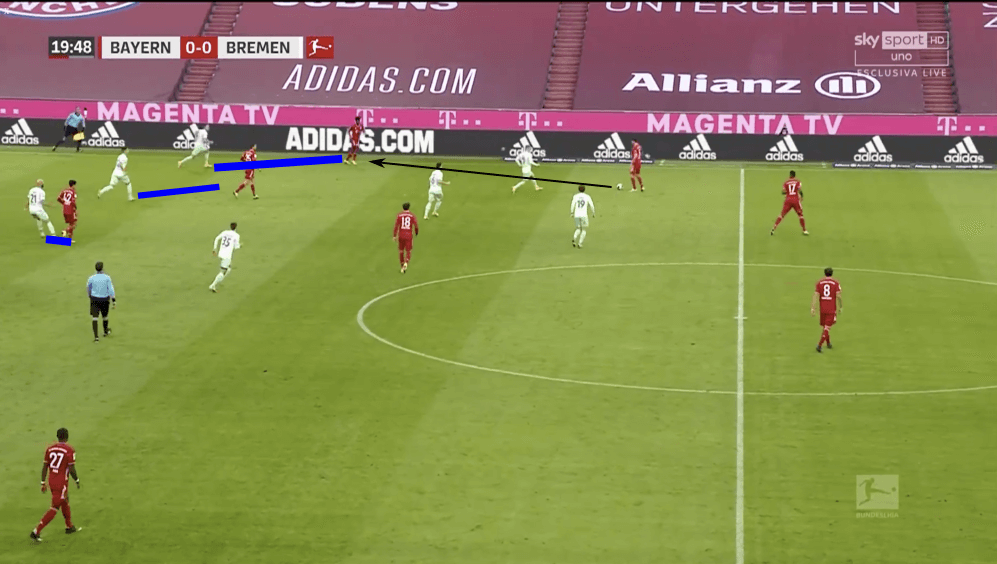

Knowing that Bayern would attack in waves and that they would need to be defensively compact, Werder knew that they weren’t going to have a lot of physical or mental energy to sustain long attacks. Instead of trying to pin Bayern back, Werder decided to invite Bayern’s press high up the pitch, in order to exploit their high (and somewhat slow) back line. This didn’t always stem from their build-up, although that was often the case. Sometimes Werder would play the ball backwards to invite the press in order to open up space in behind.

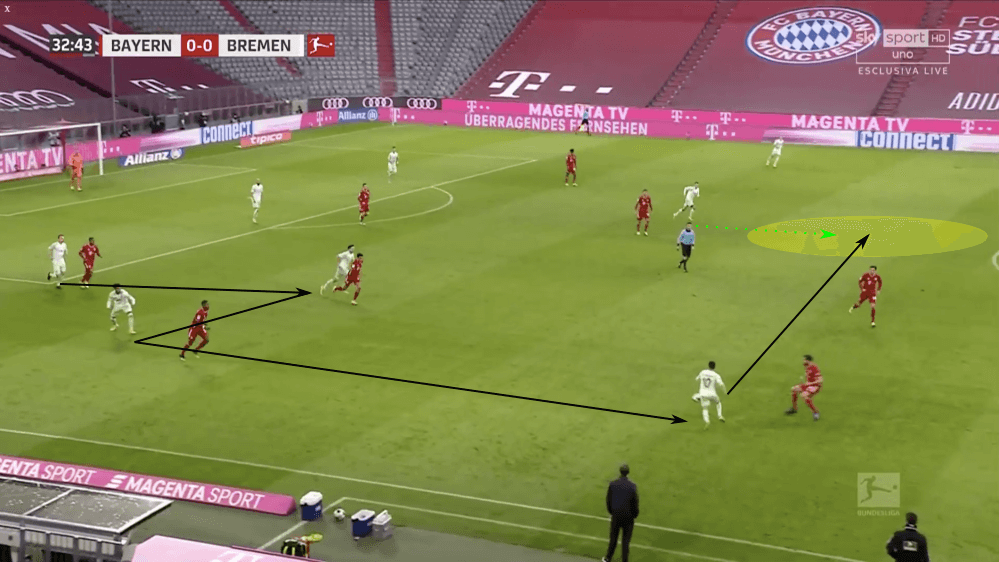

In the instance above, Werder actually began the move in Bayern’s half. However, a smart back pass allowed them to draw Bayern out. When the ball found its way to their goalkeeper, Pavlenka played a long pass to Rashica, who used his first touch to lay the ball off to Augustinsson. This small third-man pass eliminated five Bayern defenders from play and allowed Werder to attack one of Bayern’s weaker points: the space between Boateng and Pavard.

As a result of this move, Bayern’s defence was unorganised. With Martinez recovering slowly and Alaba and Hernandez having to shift over, Werder were able to overload the latter. Sargent was able to get his foot on the cross, but Neuer did well to save his shot as well as the follow-up by Augustinsson.

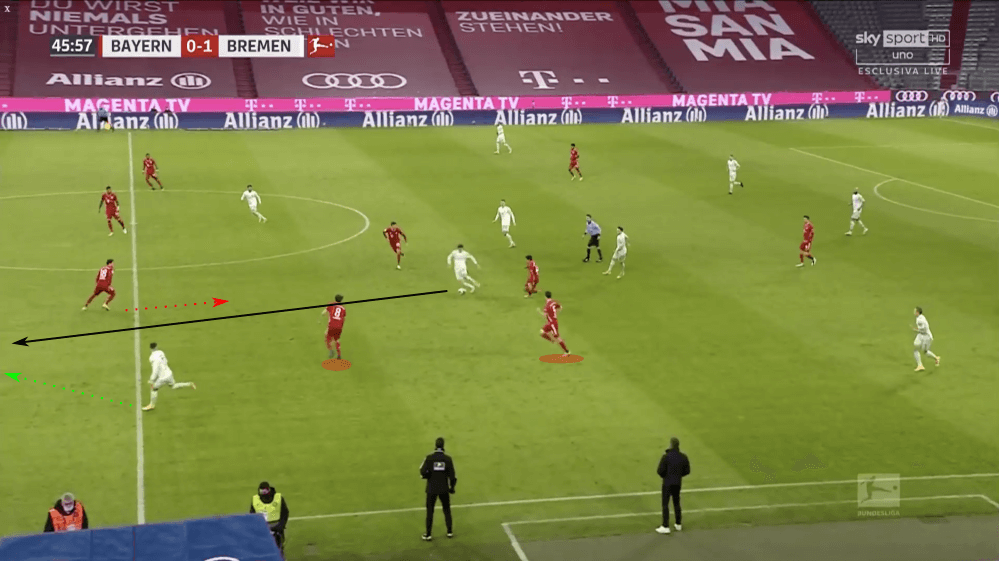

Werder were able to do the same later in the match from their own goal kick. This time, they invited Bayern’s high press all the way up the pitch in order to create space in behind. Werder’s passing pattern is highlighted above. What needs to be mentioned is the large amount of risk that took place for this to be successful. Each receiver of a pass was put under immediate pressure, and each pass was within milliseconds of being intercepted or denied. That being said, no pass was. Bittencourt received the ball and played a horizontal pass to an open central midfielder who could pick out a teammate with time on the ball.

The other piece that really stands out is the number of Bayern players who were behind the ball once Eggestein received it: three. Sargent and Rashica ended up with a 2 v 1, but Sargent’s ball couldn’t beat the first man, and Bayern were able to escape.

At the beginning of the second half, Bayern were almost punished again by Werder’s willingness to invite pressure.

Both Javi Martinez (who was now playing centre-back) and Benjamin Pavard found themselves high up the pitch pressing. A poor header from Martinez allowed Werder to find themselves in the position shown above. Gortezka had dropped to provide coverage for Martinez as Rashica made his run. This was a clear dynamic advantage as they were moving in completely opposite directions. Sargent played Rashica in behind. Rashica had so much time that it’s possible he panicked, but he ultimately allowed Boateng to catch up to him and deflect his shot out of touch. While Werder’s goal came from a throw-in and a high Bayern back line, some of their best chances on goal came from them inviting pressure higher up the pitch.

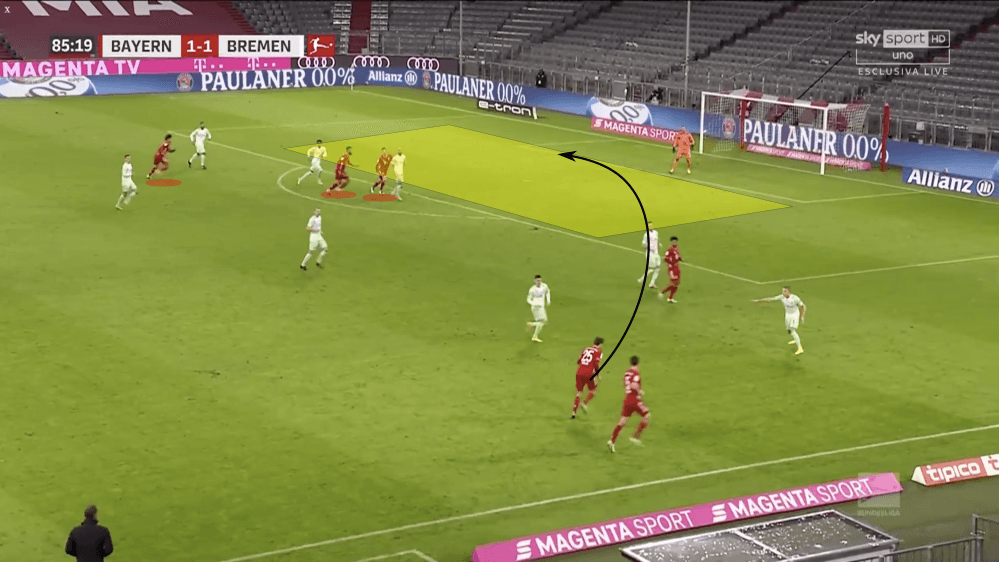

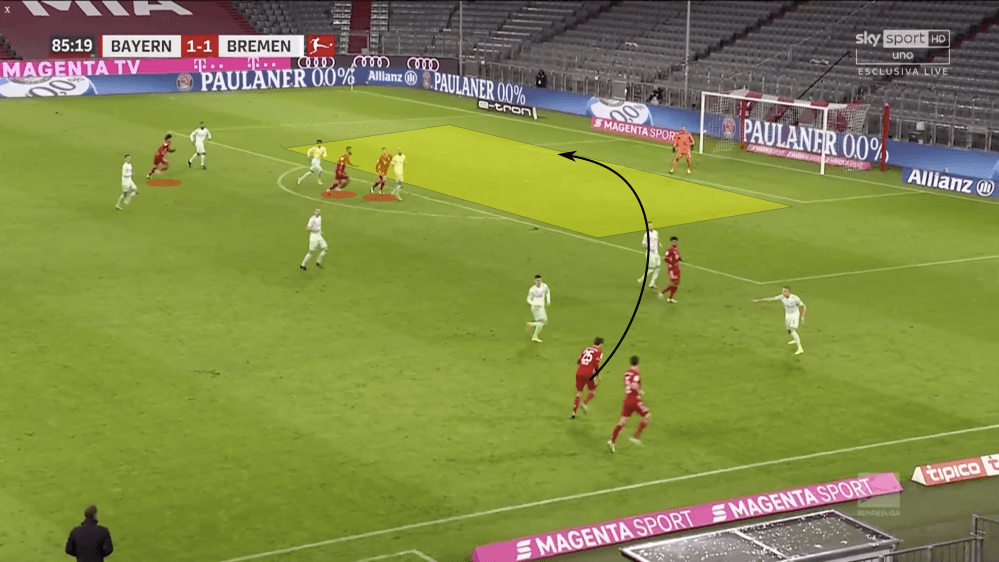

Bayern’s curled forward crosses threaten

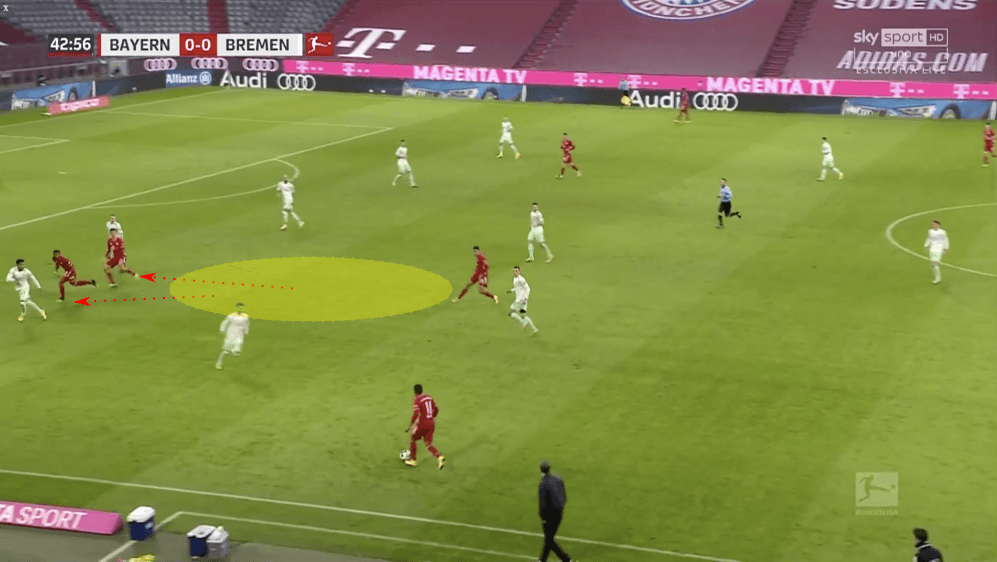

Bayern were able to claw their way back into the game through another consistent strategy they use when facing teams who like to sit in a low block. The use of a forward cross looks to exploit a defensive line that sits on the edge of the penalty area. The cross looks to exploit the space between a team’s goalkeeper and their back line. The space is big enough that a goalkeeper may hesitate to attack the ball, allowing time for attackers to run and head the ball.

Here’s the basic concept highlighted. It doesn’t always necessarily need to be a back line on the edge of the box as teams, especially against Bayern, will sit in deeper. A large space opens up in between the goalkeeper and the back line. A player lower on the pitch (in this case Thomas Müller) whips a cross into that space for his teammates to attack. It’s incredibly difficult for defenders because they cannot watch the ball and the man they’re marking. The runners, highlighted in red, will look to dismark successfully as the enter the yellow area and attempt to finish off the cross. The smaller the yellow area is, the faster the cross must be.

These crosses are dangerous because they’re diagonal balls but also because, as previously mentioned, they’re incredibly difficult for defenders to deal with. An unorganised defence will be punished, which is exactly what Bayern took advantage of.

Above is the image right before Bayern scored their equaliser. As Goretzka was about to strike the ball, Bayern’s attackers in the box did well to cause chaos. While there is a numerical equality (4 v 4), two of Werder’s defenders are entangled with one another. This created a 2 v 1 on the back post, where the ball was always going to go. Coman was essentially unmarked for all of his run, and Gebre Selassie, who was unable to win the header, could do nothing to stop Coman from scoring.

Conclusion

Of the two clubs, Werder will be much happier with the result as they find themselves in ninth place. Their next match will take place on Friday against Wolfsburg. Bayern will likely be dissatisfied with the result, but they will need to get past that quickly as they take on RB Salzburg on Wednesday in the Champions League. Despite being top of the table, Bayern’s drop in points allowed Borussia Dortmund and Bayer Leverkusen to come within a point of the Bavarians.

Comments