After securing their spot in the knockout round of the UEFA Champions League on Tuesday, RB Leipzig took on Werder Bremen in the Bundesliga on Saturday. While Werder has put in a much better performance this season compared to last year’s, they still were no match for Leipzig, who saw most of the possession and were able to grind out a 2-0 victory.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics used by both Florian Kohfeldt and Julian Nagelsmann for their respective sides. The analysis will look at Leipzig’s use of the back three in Werder’s half, Werder’s struggle to progress up the pitch, and a quick analysis of what makes Leipzig so good in transition.

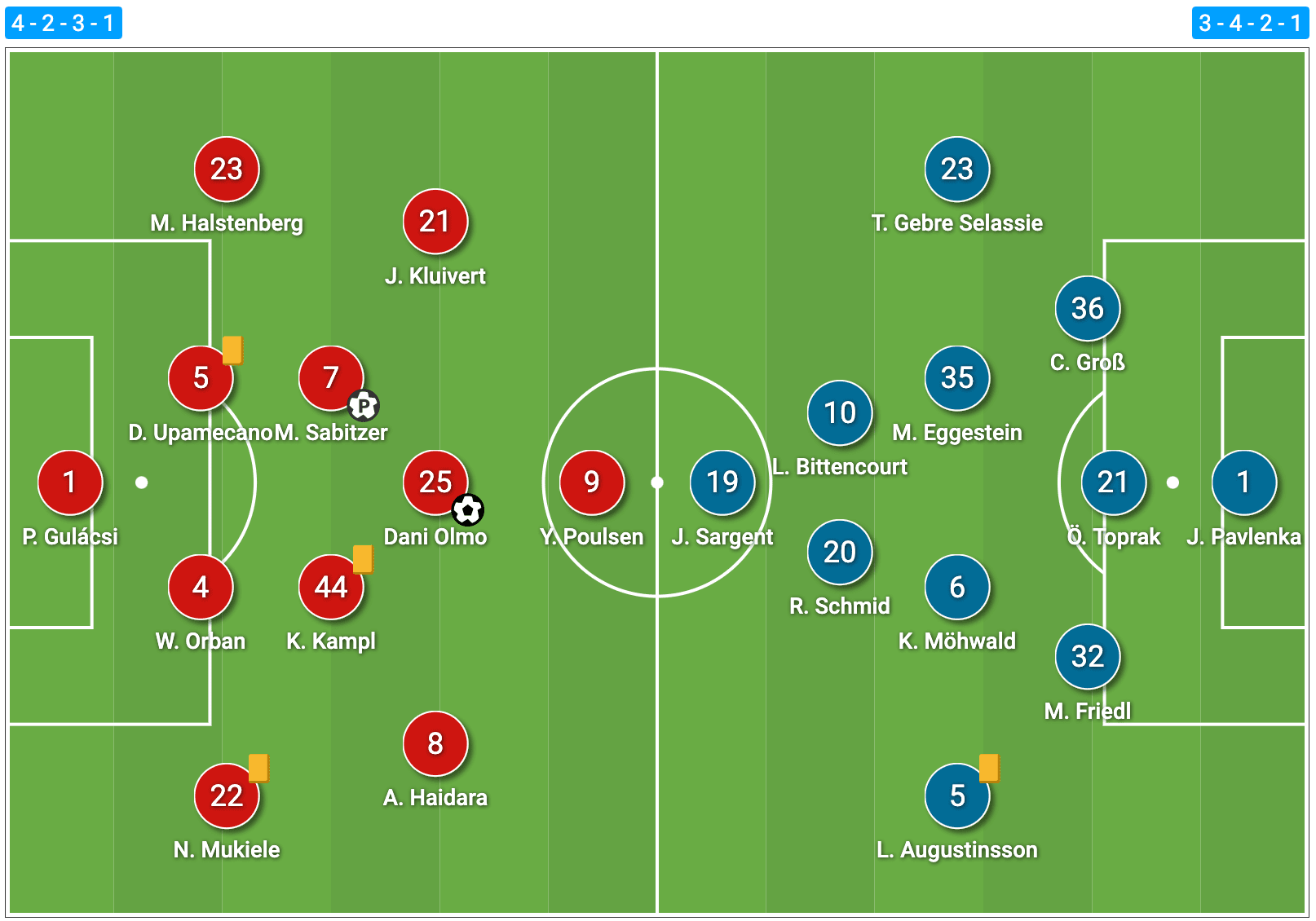

Lineups

Nagelsmann sent Leipzig out in a 4-2-3-1 with Péter Gulácsi in goal. Dayot Upamecano and Willi Orbán started as centre-backs with Nordi Mukiele and Marcel Halstenberg on the right and left flank defensively. Kevin Kampl and Marcel Sabitzer started as defensive midfielders, with Dani Olmo in front of them in the centre of the park. Amadou Haidara started on the right flank as Justin Kluivert started on the left; both players looked to support Yussuf Poulsen, who started the match as Leipzig’s striker.

Kohfeldt started Werder in a 3-4-2-1 with Jiří Pavlenka in goal. Marco Friedl, Ömer Toprak, and Christian Groß started as centre-backs. Kevin Möhwald and Maximilian Eggestein played primarily as defensive midfielders, supporting Romano Schmid and Leonardo Bittencourt, who started as attacking central midfielders. Ludwig Augustinsson started on the left flank as Theodor Gebre Selassie started on the right. Werder’s lone striker was the young American Josh Sargent.

Leipzig’s use of a back three in possession

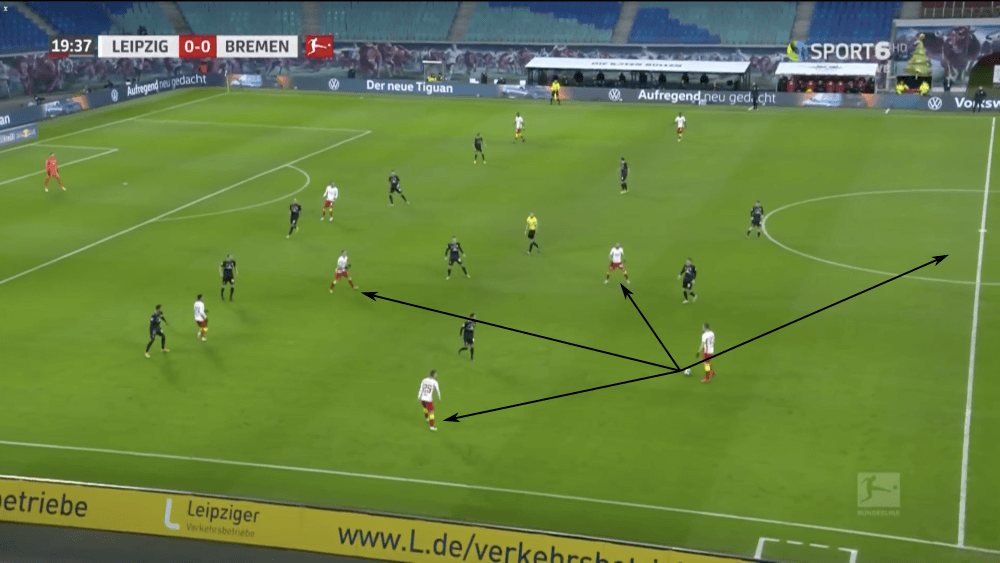

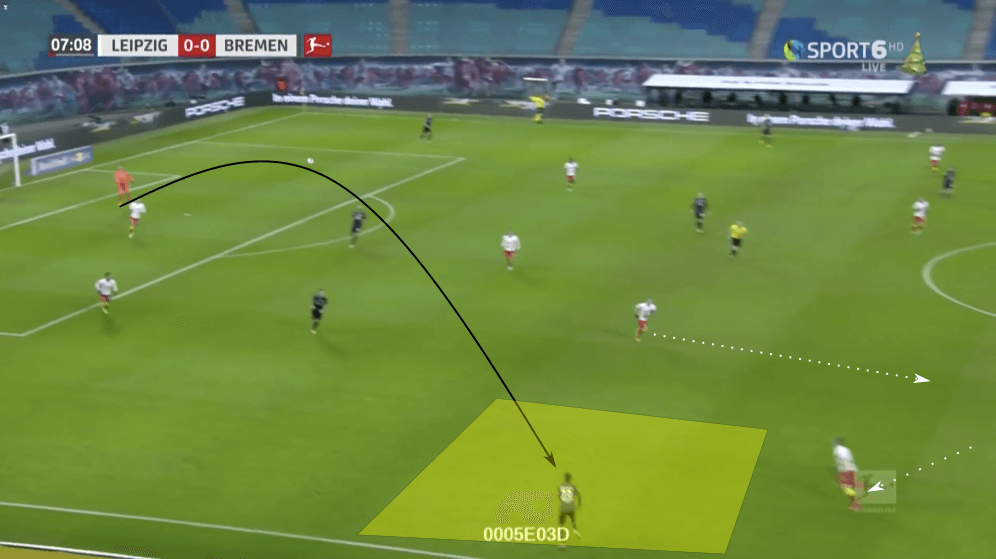

While lining up in what appeared to be a 4-2-3-1, Leipzig, who saw most of the possession, spent a lot of time with a back three. This allowed them to access passes from the half-space, which meant that they had more passing options and angles going forward due to their location on the pitch. It also meant that they were able to get forward more consistently because they didn’t spend as much time being close to the touchline. As a result, they had less pressure on them and could get forward more frequently. Below is an image highlighting why having the ball in the half-space can be so rewarding when playing from the back.

Marcel Halstenberg is in possession in the half-space, having dribbled forward in an attempt to attract defensive pressure. Werder were attempting not to pressure so that they could protect the space. Halstenberg has three immediate options that allow him to play a pass forward. As Leipzig seems to train, if he plays the most vertical pass, that will almost certainly be supported by runs from lower on the pitch, meaning that if Sabitzer received the ball, he has options to play the way he is facing. Halstenberg also had the option of passing the ball back to Upamecano or Orbán who can change the point of attack. These passing options from the central part of the pitch (relative to the wing) allow Leipzig to possess the ball with more legitimate threats toward goal.

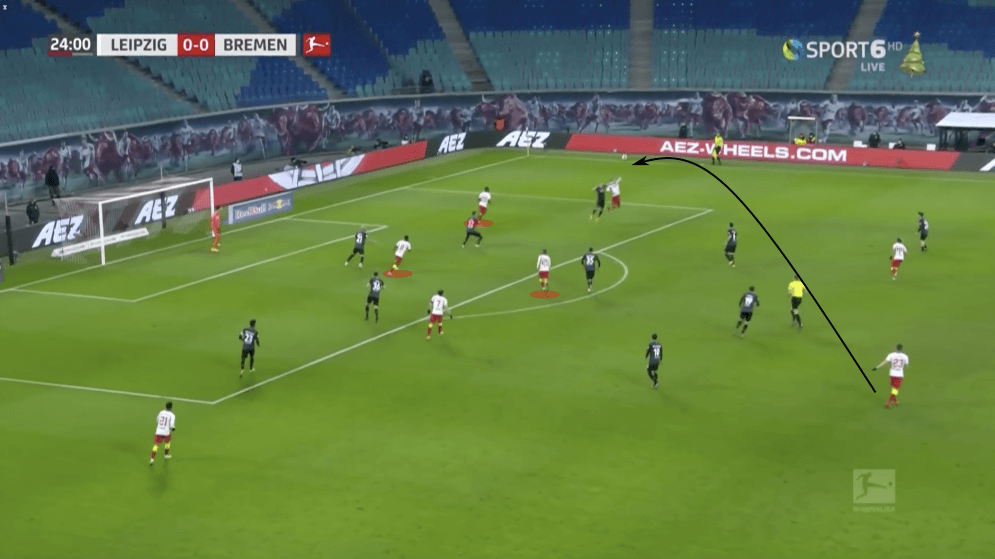

Nagelsmann appeared to trust his centre-backs to get high up the pitch as well, allowing them to develop numerical advantages by overloading spaces as they supported the attack. In the image above, Orbán progressed up the pitch on the right side. Both Haidara and Mukiele had moved in more centrally, allowing for the space to open up. Their central movement forced the Werder defensive structure to shift. This meant space opened up for Olmo, who was able to slip in behind the defender who was tracking Haidara. While his volley was blocked, Olmo’s chance in a high-scoring area came about because of Orban’s movement and ability to attract defensive pressure.

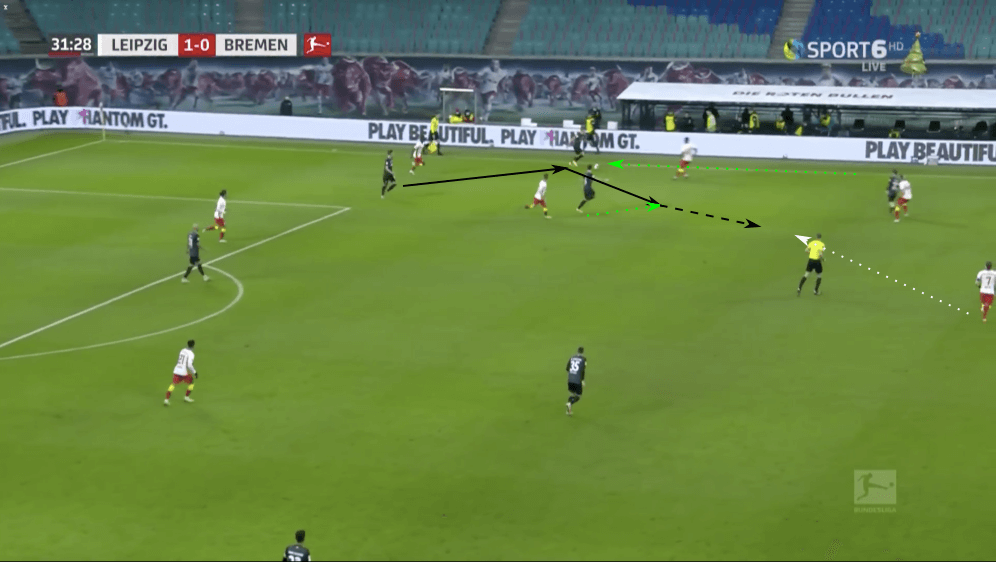

Below is the image before Leipzig drew a penalty, which Marcel Sabitzer ultimately finished off to take the lead.

The first thing to notice is where the pass comes from: the left half-space. Werder allowed this pass to be made because they were attempting to prevent those diagonal balls previously mentioned. This pass came after a longer spell of Leipzig possession, and so the Werder defence was struggling to stay organised as the ball moved quickly. While not an entirely threatening pass by itself, the area around the recipient (Poulsen) is important. Leipzig had three men near the space who could challenge for second balls. The other important piece, which I’m not exactly sure how to measure, is how much space is available around Poulsen. This much space allows for more access to second balls, allowing Leipzig to use their constant movement to get a shot on target. While Poulsen drew a foul here, it’s not insignificant that he was in this position in the first place.

Leipzig’s final goal also came as a result of their backline’s positioning in their opponents’ half. Halstenberg had made a run forward up the pitch on the left side, and through a series of rotations with teammates, Kluivert ended up as a temporary part of the back three. As he looked to get forward, he laid the ball off to Upamecano, who had shifted over.

Upamecano and Orbán’s shift to a temporary back two kept Werder’s first line of pressure quite narrow. This allowed space to open up for a pass, which Orbán played. Now, Haidara was free in the half-space with a good amount of time to pick out a pass. This led to the vertical pass to a layoff which allowed Olmo to showcase his skills and finish off a great chance. All of this came about due to the initial movement by Halstenberg, which stemmed from Nagelsmann’s tactical choice of a back three.

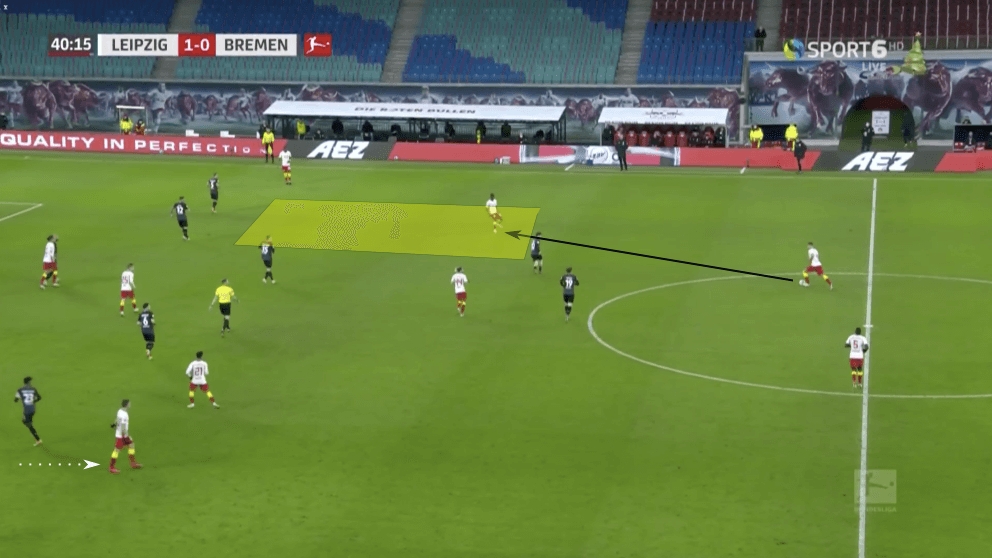

Werder’s struggle in build-up prevent progression

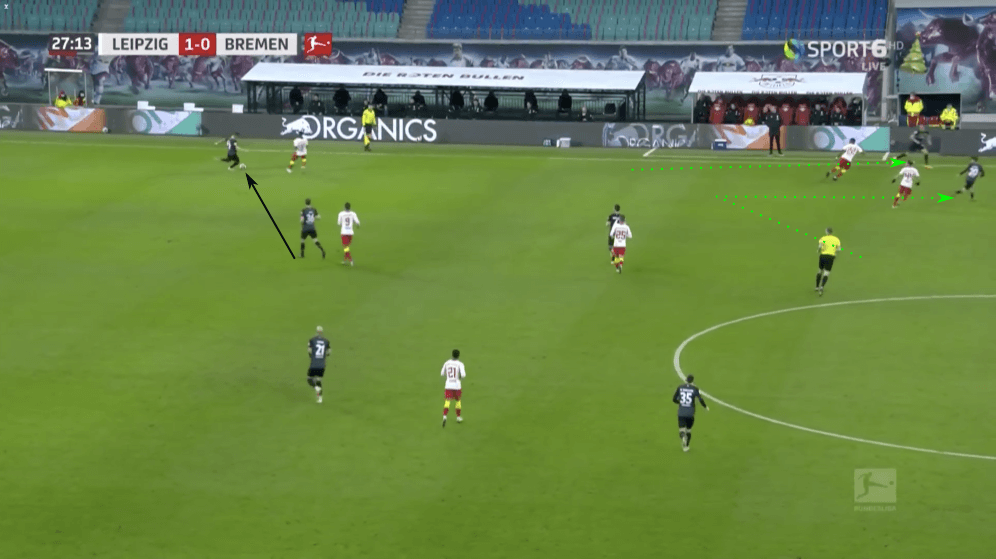

While Werder did look to get forward, they did so by engaging Leipzig’s 4-2-3-1 pressing structure, which at times looked more like a 4-2-2-2 or asymmetrical 3-3-2-2. This was always going to be difficult for Werder because Leipzig are quick and well-organised. This became apparent for Werder throughout the first half as they really struggled to get into the middle third of the pitch from their own build-up zone. One of their most common attempts at getting into the middle third was through their outside players. Toprak would step forward almost as a defensive midfielder, allowing Marco Friedl and Christian Groß to play as a pairing.

The problem was Leipzig left these players open in order to bait passes into them. When these aerial passes came in, Leipzig would send their outside backs to press as the ball was in the air. This meant that most of these passes became aerial duels. If Leipzig didn’t win the initial pass, they certainly held an advantage for winning the second ball. In the image above, Pavlenka played a ball to Gebre Selassie, who appeared to be open in space. However, Halstenberg stepped forward and won the challenge. He was able to do this so boldly because Sabitzer was dropping to prevent any forward passes. Halstenberg won the header and played Kluivert ahead of him, and Leipzig was suddenly attacking.

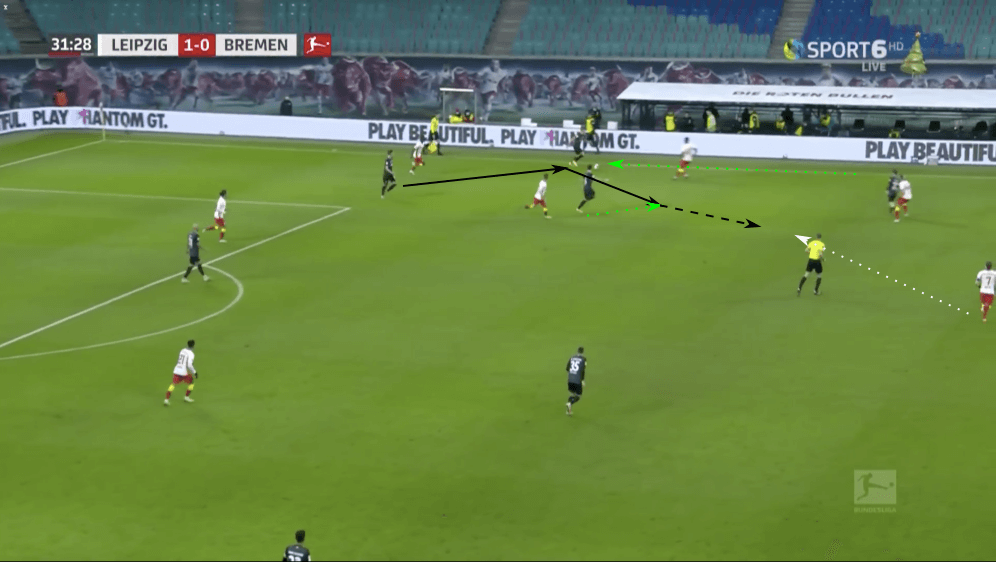

Later in the match, Werder attempted to improvise in order to avoid playing into Leipzig’s trap. What resulted is the image above, which wasn’t ideal for them. As Freidl looked to control an errant pass, both Schmid and Augustinsson vacated the area. This is likely an error because Schmid attempted to check into the space before making his run. However, the problem still remained: Werder had no plan to deal with Leipzig’s pressure before the match, which meant that they had to improvise mid-match. Without set principles in play, this can become disastrous. Luckily for Werder, they were able to deny a lot of the chances that Leipzig created through their pressing.

Werder was able to find a solution to progressing out of their own build-up zone, and that was done by dropping the outside-backs deeper. This made the amount of ground that Leipzig’s outside-backs had to cover much bigger. This allowed Werder to get more time on the ball. However, Leipzig’s layered press still posed problems.

Above is an example of Augustinsson dropping lower to receive the ball. This allowed him to turn up pitch, but he still had to quickly pass the ball to Kevin Möhwald, who was running up the pitch. As the space closed around them, Möhwald was able to get on the ball and take a touch inside. As he did, Sabitzer quickly closed him down, as Kampl closed down a passing opportunity. Sabitzer knew Möhwald could only pass to his right, so he slid that direction and broke up the pass, allowing Leipzig to regain possession in a very dangerous area.

Leipzig’s defensive pressure leads to quick transitions

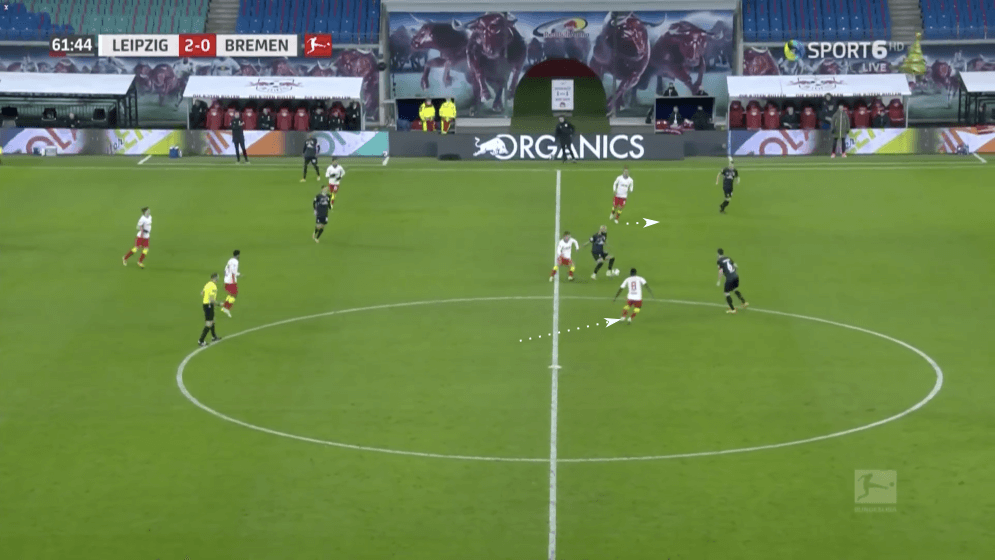

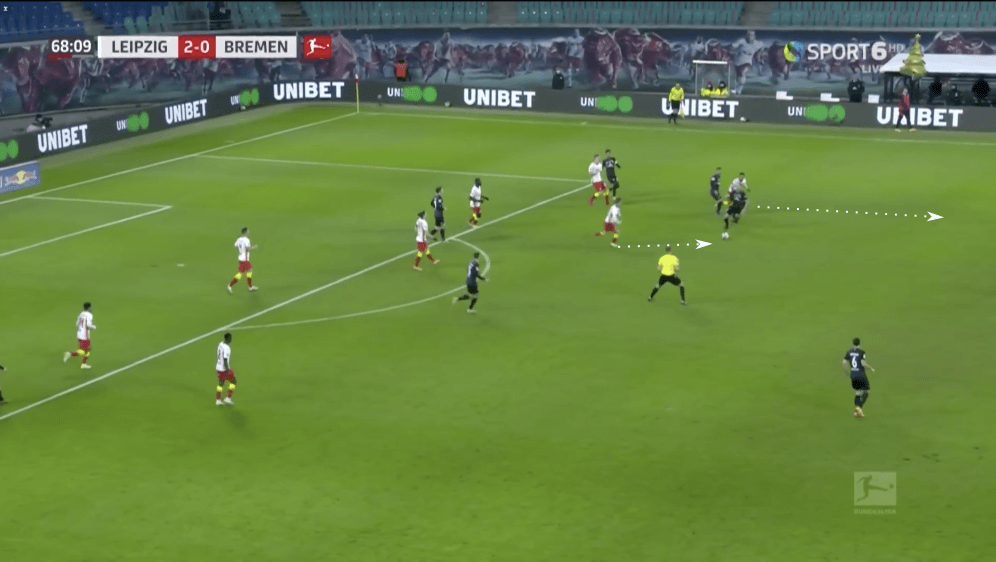

Leipzig’s swirling defence made it incredibly difficult for Werder to get forward, even when they were able to get into the middle third of the field. Not only do Leipzig hunt in packs, but they also look to anticipate their opponent’s actions when they’re being challenged. They look to block off near-ball passing lanes in order to suffocate the man on the ball, leaving him no chance but to get dispossessed. From there, they quickly move to attack. The first example comes from the second half of Saturday’s match.

It seems the pressing trigger in the instance above came from the horizontal dribble. Once Haidara recognised where the man was going, he stepped to eliminate the pass to Möhwald. The man on the ball had no options that way, so he looked to turn back from where he came. As he did, Olmo continued to apply pressure. When Toprak looked back, Poulsen took two steps forward, eliminating Toprak’s other passing option. With nowhere to go, Olmo looked to win the ball as his teammates stood on the same line as their opponents. Haidara recognised the favourable position, and as Olmo won the ball in the direction of Poulsen, he ran into the space behind, allowing Poulsen to slip a pass in. While it wasn’t called, Haidara was likely fouled in the penalty area.

Below is another instance of Leipzig’s anticipation, again when a horizontal dribble takes place. This time, they earned a counter that saw Poulsen’s chip over the goalkeeper dink off of the post.

It began on the edge of their own penalty area. Christian Groß was attempted to corral a loose ball. Despite being closer to the ball (it was practically on his foot), Groß didn’t have the dynamic advantage. Once again, Olmo saw the horizontal movement and sprung into action. Groß tried to shield him off of the ball, showing Olmo his back without having full control. Olmo easily dispossessed him, and Leipzig was off to the races. Within 10 seconds, Poulsen’s shot was bouncing in on goal.

Conclusion

Leipzig’s victory finished off a long week for them on a high note, having drawn Bayern Munich on Saturday in Munich before finishing off Man United on Tuesday. Nagelsmann’s side continued to keep pace with the rest of the Bundesliga teams at the top of the table. Their next match will be against Hoffenheim on Wednesday. While Werder appear to be performing better than last year, they still find themselves in 13th place at the moment. Their next match is on Tuesday against Borussia Dortmund, who recently fired Lucien Favre after Dortmund’s 5-1 drubbing at home against Stuttgart.

Comments