On Sunday, RB Leipzig hosted Bayer Leverkusen at the Red Bull Arena. Since both teams were fighting for the top four, it was an important match that might affect the final position in May. Although thrashing Club Brugge in the UEFA Champions League in the midweek fixture, Leipzig were unable to produce the same level of performance without the fans, Marsch, and several first-team players. Leverkusen’s quick football was the dominant theme of the clash and managed to seal all three points. This tactical analysis will explain the tactics of both sides, including how might Marsch could improve their goal threat actions in the offensive third, according to top gambling sites on

Wetten.com.

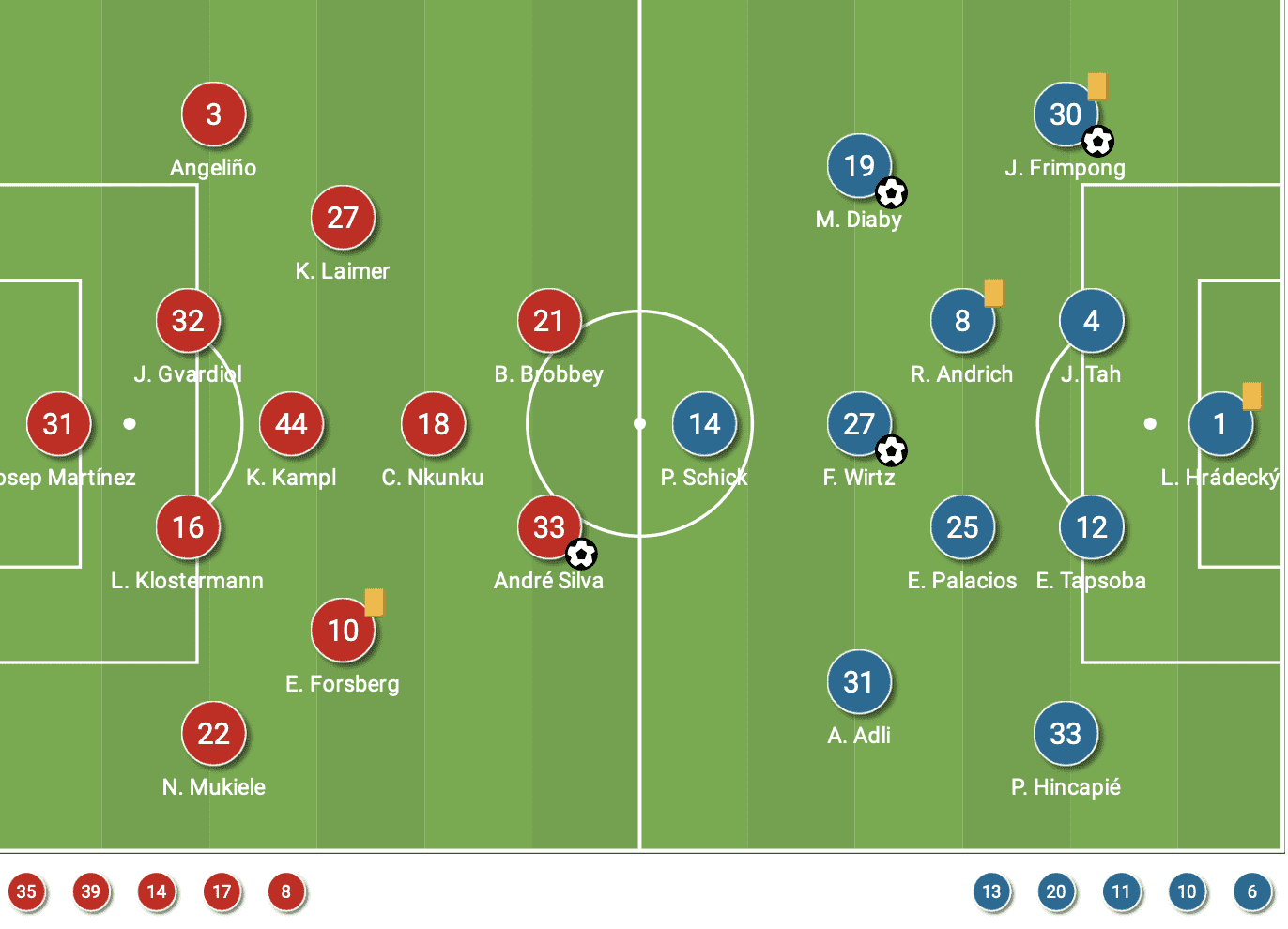

Lineups

Leipzig came with a back four in this game. Since some first-team players were unavailable due to COVID-19, Joško Gvardiol partnered Lukas Klostermann as the central defender. In the midfield, it was a 4-3-1-2 shape initially with Christopher Nkunku supporting the strikers. Brian Brobbey gained his first start in the Bundesliga and he was the partner of André Silva.

Leverkusen lined up in their usual 4-2-3-1 formation with just a few changes from the victory against Celtic. Patrick Schick and Edmond Tapsoba returned to the starting lineup. They have very promising young attackers, such as Moussa Diaby, Amine Adli, and Florian Wirtz operating behind the striker as well.

Solving the 4-3-1-2 & 4-4-2

Throughout the game, Leverkusen demonstrated different ways to create opportunities. In the offensive phases, they operated in a 4-2-3-1 shape with a clear principle of plays and alternative positionings of the midfielders. This is a team that was blessed with so much pace, individual quality, and potential that made Leipzig difficult to press them.

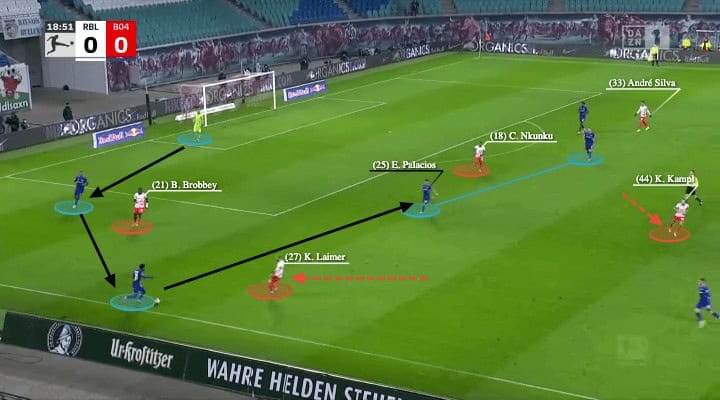

Initially, Leipzig defended with a 4-3-1-2 shape with Nkunku covering a midfielder behind the strikers. The first line would be marking the centre-backs or pressing the goalkeeper. Then, they had the defensive midfielder to cover spaces, while the midfielders swing from the far side to maintain the compactness, or jump out on the ball half-space to press the full-backs. The full-backs rarely came out to press early as the last line was fixed by the high and wide players of the oppositions.

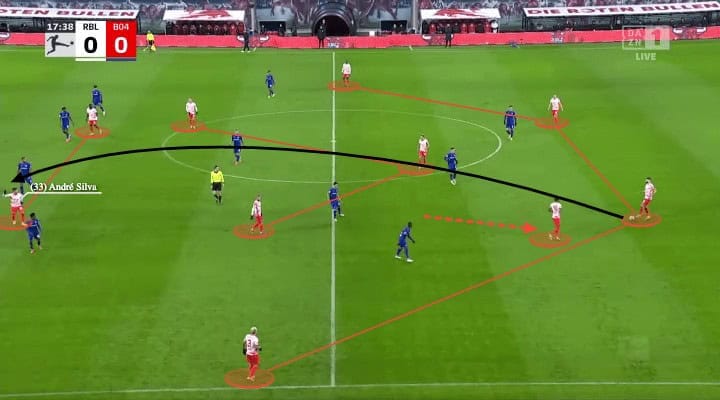

The first example shows Leipzig’s pressing in a man-oriented basis. The 4-3-1-2 shape should be covering the centre initially, when they closed the central options, they invited the opponents to go sideways, such as Lukáš Hrádecký lofting the ball to the full-backs. Then, you could see how they man-marked the oppositions to close all options. Brobbey, the striker, closed the backward passing lane with Nkunku around the holding midfielder. Emil Forsberg jumped out to press the left-back, Kevin Kampl was covering in the centre, and Konrad Laimer would then go inside to balance the structure. While the other two Leverkusen players dropped to offer a passing option to the left-back, both Nordi Mukiele and Klostermann tightly followed their target, this was the man-marking on the ball side of Marsch’s side.

All they need was to win the individual battles, do the forechecking well, be aggressive, be brave, make contacts, and recover possession. But Leipzig’s pressing was also lacking a bit of intensity, they might need push further in this regard.

But this section would put more emphasis on how the positional structure of Leverkusen solved the defensive shape of the oppositions. Firstly, you could see the dynamic positioning of Schick. Instead of staying between the centre-backs, the Czech Republic international would like to orient himself to one winger, serving as the target of the long balls. Then, the others would further congest that space and thus result in a 4v3 in the shaded region above. But that was only part of the play only, as their great weapon, Diaby, was isolated against Angeliño on the far side. If they could win the first/second ball, there was a switch option to allow Leverkusen to hit the weaker side quickly.

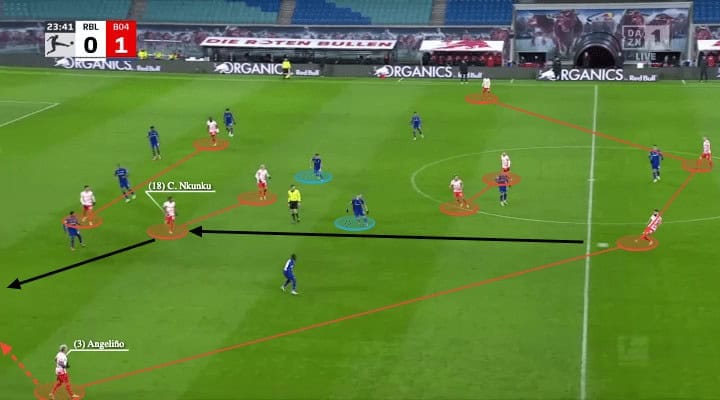

There were clearly some problems in the 4-1-3-2 pressing of Leipzig on Sunday, the team was lacking the intensity in the first line, Brobbey was never going tight enough to block the angle, make contact, or carry out double-pressing in higher areas. This created tremendous pressure for the midfielders as the ball easily went sideways, the wide midfielders were late to access the target as they travelled all the way. Here, Laimer was late to close Jeremie Frimpong, so Leverkusen escaped very easily. There were a few structural issues as well, the 4-3-1-2 only had one player behind the strikers, this inevitably resulted in a 1v2 numerical deficit against the two defensive midfielders of Gerardo Seoane. In this example, as Nkunku was marking Robert Andrich initially, he could not close Exequiel Palacios when the Argentinian supported Frimpong.

Also, Leipzig would be a bit outnumbered in higher areas without the involvement of the last line. As the high and wide front three of Leverkusen fixed the four defenders, and the defensive midfielder was subjected to cover spaces in front of the centre-backs, the whole team was stretched vertically by the opposition. In this scenario, initially Kampl was marking Palacios, but he abandoned the target when he went dee, and this was another reason to explain the difficulties in the previous paragraph.

However, the recurring issue of Leipzig regardless of the shape was the concept of balancing the structure. Sometimes we feel the far side players were dragged away too far, or marking a strategically less important target, so they were not closing spaces or passing options in the centre enough.

There were a few things Leverkusen did very well at the Red Bull Arena. Their involvement of the goalkeeper in the build-up, use of two midfielders, occupation of spaces to create width and depth in the shape, were all important to break the opposition press.

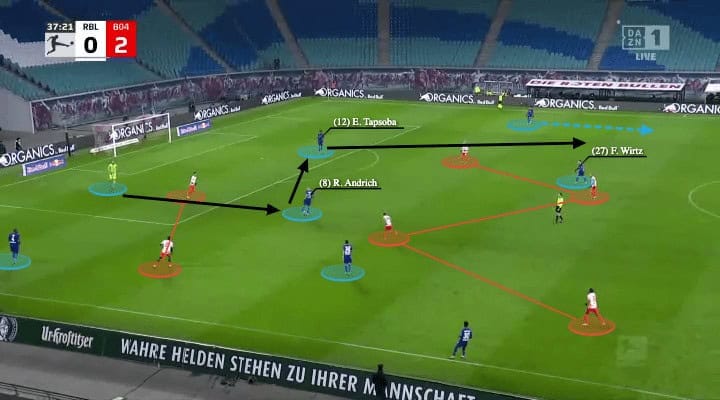

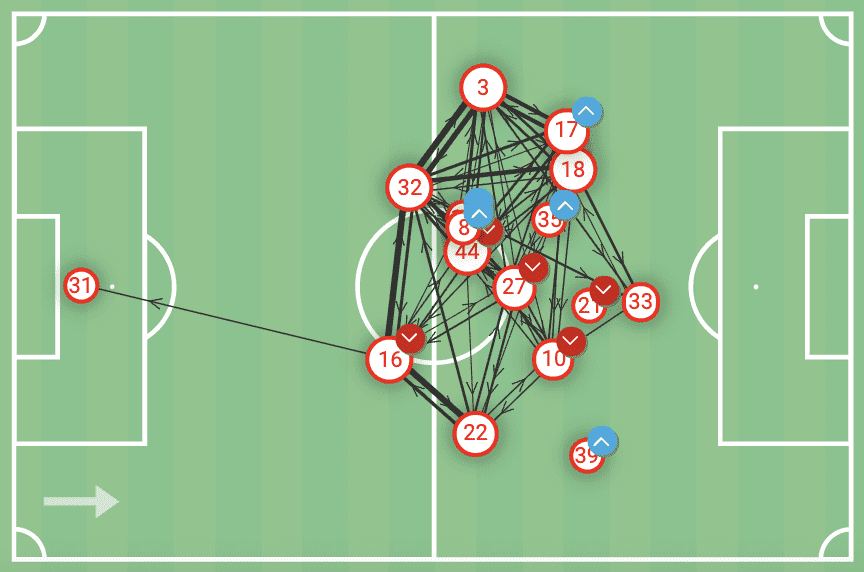

In this above scenario, although Leipzig switched to a 4-4-2 or 4-2-2-2, with one more man as the central midfielder, they still struggle to press as the control of spacing was poor. Now, we interpreted the structural advantage of Leverkusen as the 3v2 midfield overload from a 4-2-3-1 or 4-1-2-3. With Wirtz appearing in the second third, they kept one Leipzig midfielder deep, so the other midfielder was isolated against Andrich and Palacios. Then, Leverkusen easily circulated the ball as they reached the free player (Tapsoba), this was an advantage generated from Hrádecký’s involvement in the first line (3v2), he and Jonathan Tah fixed Brobbey and Silva on the right side, so Seoane’s men went out on the left side.

Another scenario above shows the dynamic positionings of the Leverkusen midfielders, but Leipzig were also showing very similar problems regardless of the press. Here, some elements were explained, such as the 3v2 in the first line with Hrádecký and use of wide full-backs. But this time, Palacios dropped deeper between the centre-backs, this freed himself to receive as the strikers were marking the centre-backs initially. Leipzig could not stop them as the shape was stretched vertically and horizontally. Since Wirtz came a bit deeper, he instantly dragged Laimer away from the press, so the Leipzig strikers were left without any support.

Leipzig faced problems in their press as the wingers were dragged too wide in a 4-4-2, they could not balance the numbers in the midfield, but they have no strategy to close the oppositions with a side trap.

For Leipzig, they switched from a 4-1-3-2 to a 4-4-2 as this should give an additional midfielder in front of the centre-backs. When they only had Kampl and the five-man press, as we have analyzed, Leverkusen broke them easily by using two deep midfielders. Also, Seoane’s men could go further direct by lofting the ball to full-backs or finding Schick in the middle third. In those areas, the Eternal Bridesmaids were dominant as they had more players to exploit the high line and the spaces behind.

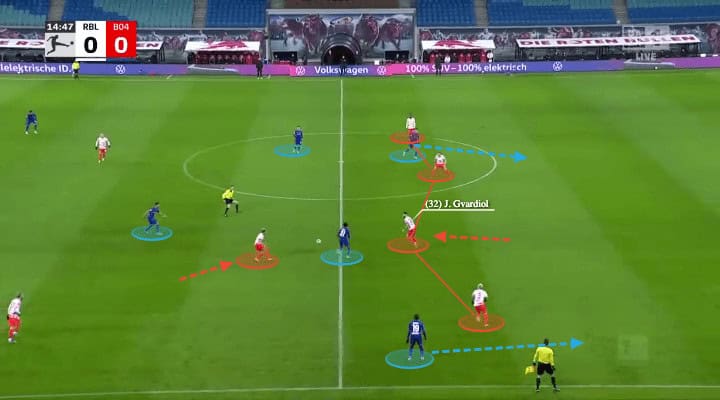

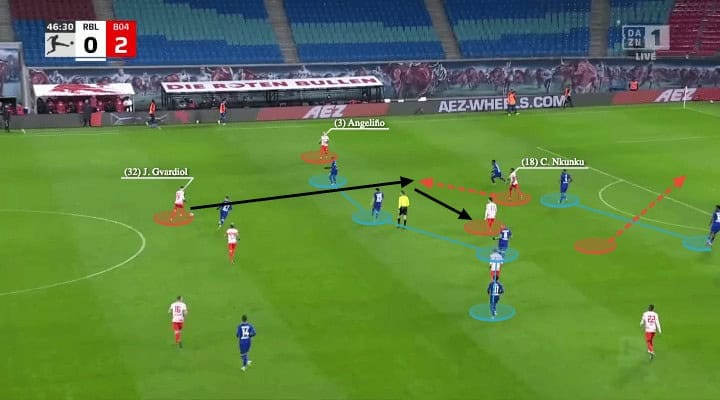

In the above image, which was a second ball battle, you could see the exposed Leipzig shape. They only have the backline plus one midfielder (Kampl) to handle five blue shirts. Another problem was the subject of closing spaces, Gvardiol was not good at defending spaces in front. His judgements on challenging angle and the timing to step up were suboptimal. Even it might was a potential double-pressing scenario, Leipzig could not slow the opposition down, and just let Leverkusen went to the other side.

Even in the second half, which Leverkusen spent more time defending in a block, and hit Leipzig in the transitions, they still retained the ability to beat the press. The key was the midfield domination, as shown in the above image, they had the 3v2 and two players in front of the deep Leipzig midfielder. And since the first line (Leipzig 2v3) did not give enough press Hrádecký to play, the goalkeeper simply threw the ball out to Wirtz in the right half-spaces, Leipzig could not stop them. Again, the last line of Leipzig could not jump out to press as Schick, Adli, and Diaby were high to fix the defenders.

Lightning transitions

Another impressive part of Leverkusen’s game was their offensive transitions, they were extremely dangerous in this phase, Leipzig were unable to cope with the quick runners throughout the game.

Seoane and his coaching staff must have done a great job at pointing out the keys to exploit the Leipzig defence in transitions. Whenever there were turnovers in the centre of the pitch, the entire team would sprint and keep making runs to push the last line away, and this always resulted in a Leverkusen overload on the rest defence.

For example, you could see one of the emphases was to deploy high and quick wingers to run the outside of the formation. Both Adli and Diaby were doing this job, which gave the last line a question: should the centre-back come out to close Schick or leave him alone?

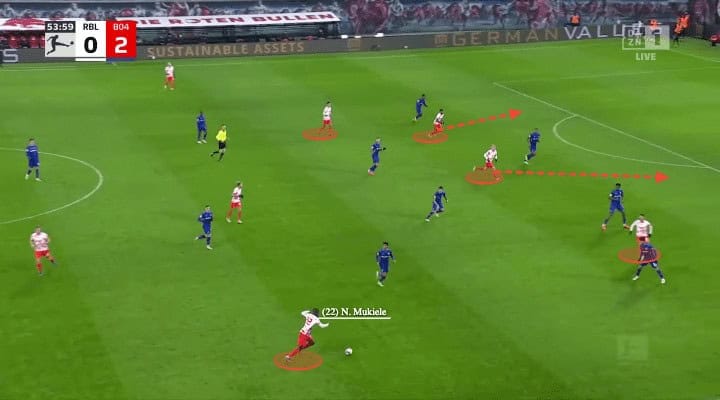

They also targeted spaces behind the full-backs to attack. There were several reasons behind, firstly, of course it was because Angeliño would take up high position in the attack. Secondly, it was about individual behaviours, Mukiele was prone to rush and make a challenge by leaving his position even the timing was not right, so Leverkusen could simply sneak behind with Adli’s runs.

The winning goal was a very good example to show the transition threat of Leverkusen and how Leipzig failed to cope with them. Initially, after a turnover in the midfield, the guests had as much as five players running towards three oppositions, and two of the runners were attacking from the outside of the defensive line.

That minimum width provided during the transition proved to be pivotal in the goal. As Leverkusen had more players, they stretched the oppositions and found spaces outside of the three-man line. Even Kampl went back to make it a 3v2 in the centre, another two Leverkusen players: Frimpong and Diaby were completely free on the far side and the edge of the box. Since Klostermann could not close the angle of Wirtz, Leipzig just let the oppositions found the free player in the box.

Offensive principles of Leipzig

Although Marsch was not on the bench and the formation was not a back three, we could still observe the principles of Leipzig’s attack from this game. Just like many other “Red Bull teams”, they were direct, vertical, and aggressive to break lines in this phase.

In the early stage of the game, Leipzig wanted to play with a higher tempo, forcing more transitions in the offensive third. Therefore, they did not go into spaces between the lines or playing short passes to the midfield, and tended to go behind with direct and vertical long passes into spaces behind the opposition full-backs.

Particularly, they attacked from the left side more often as Gvardiol was a talented passer and progressive carrier. In the above image, you could see the 4-3-1-2 shape (though Nkunku was deep), they just directly found Silva, who requested for the ball behind. However, they were lacking the individual quality to exploit the opponents in 1v1 when the receiver reached zone 16 or zone 18, not many dangerous attacks were generated from these plays.

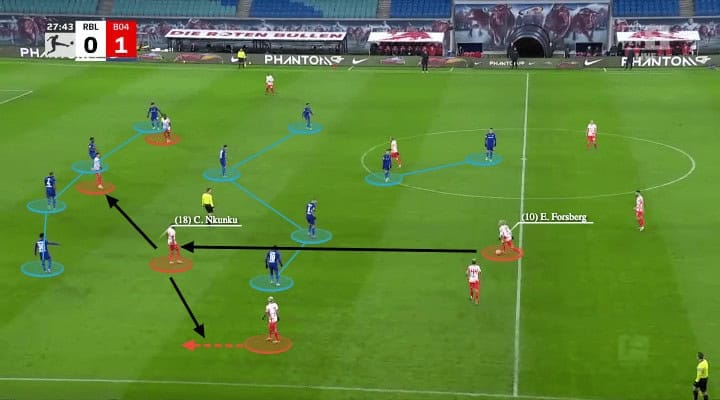

When Leipzig went from a 4-3-1-2 to a 4-4-2/4-2-2-2, they had Laimer helping Kampl in the midfield, while the wingers were operating narrowly in the half-spaces. That means the team had more numbers in the centre, which allowed the players to combine with one-touch passes, one-two because of close proximity.

This also showed the verticality of Leipzig’s attack. The centre-back did not prefer going to the midfielders diagonally, instead, they always looked for a vertical pass to break lines in the left half-space. The two deep midfielders were more like a decoy to drag the Leverkusen midfielders out, as Nkunku presented himself in spaces behind the right midfielder here. In addition, the two strikers were tasked to fix the last line and keep the four defenders engaged.

At the meantime, Angeliño also joined the attack in higher spaces, the timing of his forward movement was earlier, so he could outrun the right-winger and arrived at spaces when Nkunku released him.

The above image is an alternative scenario, some different elements were shown although the verticality to break lines in the left half-spaces was the same concept. This time, the deep midfielders made an impact, especially when Forsberg operated in the outside of the block, the Leverkusen midfield was reluctant to leave their positions. Hence, the Swedish international had rooms to play the forward passes without any pressure.

The rest of the move was to create the third man for Nkunku, both Silva and Angeliño could serve this role from two angles, then Leipzig was expected to attack quickly as they only had the last line to beat after finding Nkunku.

The concept of verticality was important to the contribution of the goal. In the second half, Marsch and Achim Beierlorzer wanted the team go get behind of Frimpong more often. Since Angeliño’s high position would draw Frimpong out as Leverkusen would like to reserve Diaby in the rest attack, spaces was expected to appear behind of the Manchester City academy product, all they need was to exploit that area.

In the Silva goal, Nkunku demonstrated a great example by moving into spaces behind Frimpong diagonally from the half-spaces. He was released by Gvardiol’s long pass then.

What is missing in the final third?

But there were also some problems in the Leipzig attack. In terms of stats, their non-penalty xG of this game was merely 0.9 from 11 shots, which was not good given they had 14.11 shots per 90 this season. Their xG of this game (1.66) was also lower than the season average (2.1). So, why couldn’t they create higher quality chances despite of their clear principles of plays? This part of the section will give some suggestions on how Leipzig might generate more threat in the final third.

Leipzig played with two formations in the offensive phases, 4-3-1-2 and 4-4-2, the common feature was the two strikers they had, but the strikers did not coordinate and interact with each other enough in the attack. In fact, since they had two strikers against a back four, it was a 2v2 against the centre-backs, separations and isolations should be easily created when the Leverkusen centre-backs stepped up.

Specifically, Leipzig did search for attacking depth behind in the centre well enough, or the way of doing so was suboptimal. In the example above, it was the half-spaces progression we’ve explained in the previous section, but notice how Nkunku’s drop has pulled Tah away from his partner. When given such a space between the centre-backs, if they had a runner from deep, or a lateral angle, or a diagonal angle, would at least force the defender to react. If the centre-back reacted to the deep run, spaces behind the midfield enlarged, or if he didn’t, then Leipzig should try to release that runner, it was a 1v1 against the keeper!

The same situation appeared more than once in the second half, when Leipzig needed a goal, they did not grab those moments to create goal threats. Here, Dominik Szoboszlai had the ball, and you could see the distancing between Tapsoba and Tah again, it was large and very difficult to cover, but Silva did not go make the diagonal move into blue space. Instead, he tended to continue the move to the right side, then Szoboszlai did not have the angle to poke the ball to him, the opportunity was gone.

Another issue of Leipzig’s structure was lack of width. Since the team wanted to counter-press together when during turnovers, the players were staying in the centre, such as the inverted wingers in the half-spaces. As a result, sometimes the player on the ball found himself without an option to pass as the lines of Leverkusen were compact horizontally.

In this situation, Mukiele could not pass forward as Silva did not present himself as an option behind the left-back, while Forsberg and Nkunku were running forward, the duo lacked the change of pace to arrive behind at the right moment. Given the French right-back was not a talented passer likes Kevin De Bruyne, it was too difficult for him to play in these situations.

Conclusion

As we have shown in this analysis, Marsch’s Leipzig still had a long way to go. The pressing was not good enough in terms of the intensity, coverage, compactness. Some of the issues might be eased by the change of formation, such as a 3-1-4-2 shape they used against PSG, but each individual must continue to develop, being more consistent to help the team.

Leverkusen played a very good game, the tempo of the attack was very quick. Seoane also maximized the strengths of his side, using the pace of the attackers to hit the weak spots of the oppositions (the last line). They fully deserved the victory and could have scored more on the transitions in the second half, it was also interesting to see the development of youngsters such as Wirtz and Diaby, and how they further contribute in the remaining part of the season.

Comments