Bo Svensson is a 42 year-old Manager currently in charge of Mainz in the Bundesliga. Given his age it is perhaps unsurprising to hear that his managerial career is still in its infancy but he is nevertheless showing considerable talent, putting together teams with an exciting intense pressing and direct attacking style. He initially began his coaching career with Mainz’s youth set-up, before taking the Head Coach position at FC Liefering who play in Austria’s second division. Liefering play the Red Bull brand of football given that they are RB Salzburg’s second team in all but name. After Jan-Moritz Liechte’s time in charge of Mainz came to an abrupt end after three months in charge, Svensson returned to Mainz, this time in charge of the first-team. At the time of writing, Svensson has a 44% win rate and Mainz are in the middle of a terrific season where they sit comfortably in the top half of the table, and are potentially beginning to think about European qualification. This tactical analysis will give an overview of Svensson’s tactics with Mainz, providing an analysis of some of the key concepts in the different moments of the game.

Bo Svensson Formations and personnel

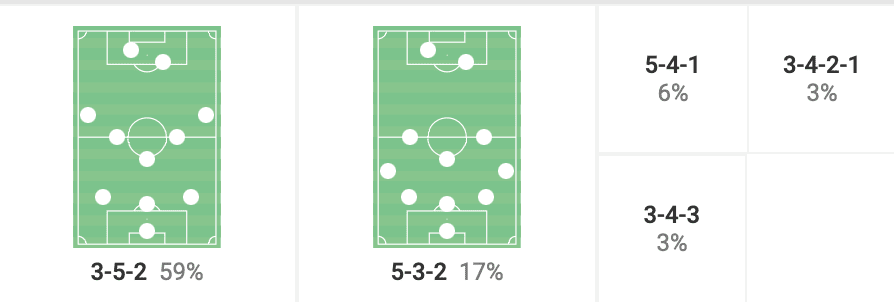

Svensson exclusively plays with a back three as we can see from the formations he has used throughout the season thus far. Whilst he has used a front three or lone forward at times, through a 3-4-3 or 5-4-1, he greatly prefers to play with two forwards.

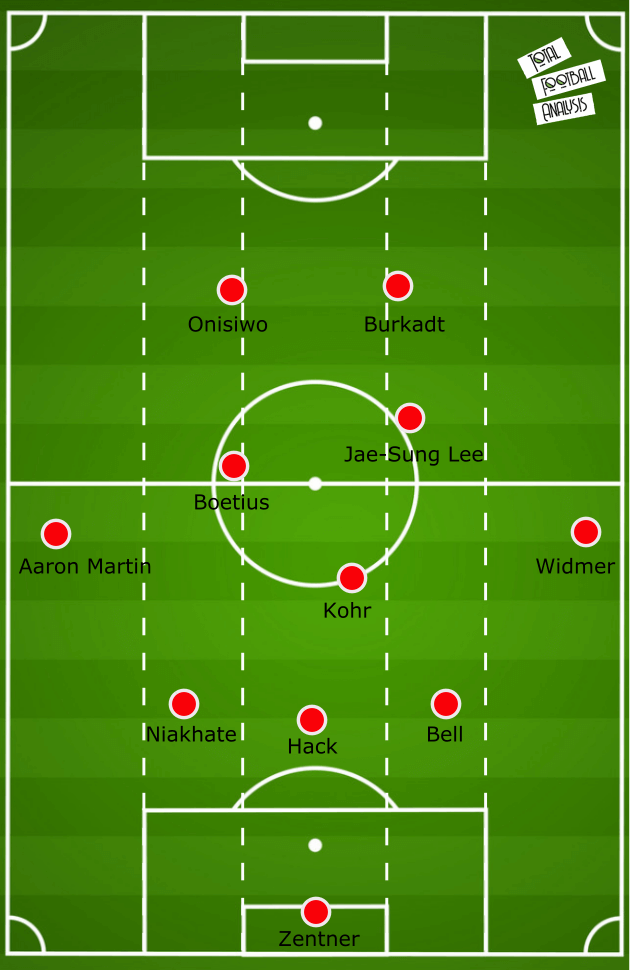

Svensson also has a pretty clear preferred starting XI. Robin Zentner has been a regular in goal whilst Stefan Bell, Alexander Hack, and Moussa Niakhate have been his favoured starting back three, but he has also given minutes to Jerry St Juste and David Nemeth in these positions. Whilst Anderson-Lenda Lucoqui has had gametime at left wing-back, Aaron Martin has played the more minutes, and Silvan Widmer has been a constant at right wing-back. Dominik Kohr or Anton Stach hold the midfield three, while any of Jean Paul Boetius, Jae-Sung Lee, or Leandro Barreiro Martins will play in the ahead of them. Kevin Stoger has also featured with some frequency. Up front Jonathan Burkadt and Karim Onisiwo have been favoured but Marcus Ingvartsen and Adam Szalai have also contributed with significant minutes themselves.

Bo Svensson In possession

Svensson doesn’t purely look to use counter-attacking by any means. Whilst they average less than 50% of possession (44.7%), they are still committed to building from the back, albeit with a commitment to playing forward quickly and ruthlessly.

Svensson builds with a wide back three, and whilst Kohr or Stach, whichever plays, often offers in the single pivot position, offers in that space during build-up, Hack will also drift into that space to provide an easy line-breaking pass option for either of his wide centre-backs. He can be found with the pass option seen in the following image, but if the ball is worked wide down the line to the wing-back, Hack may well continue his run and be a passing option inside for that player too.

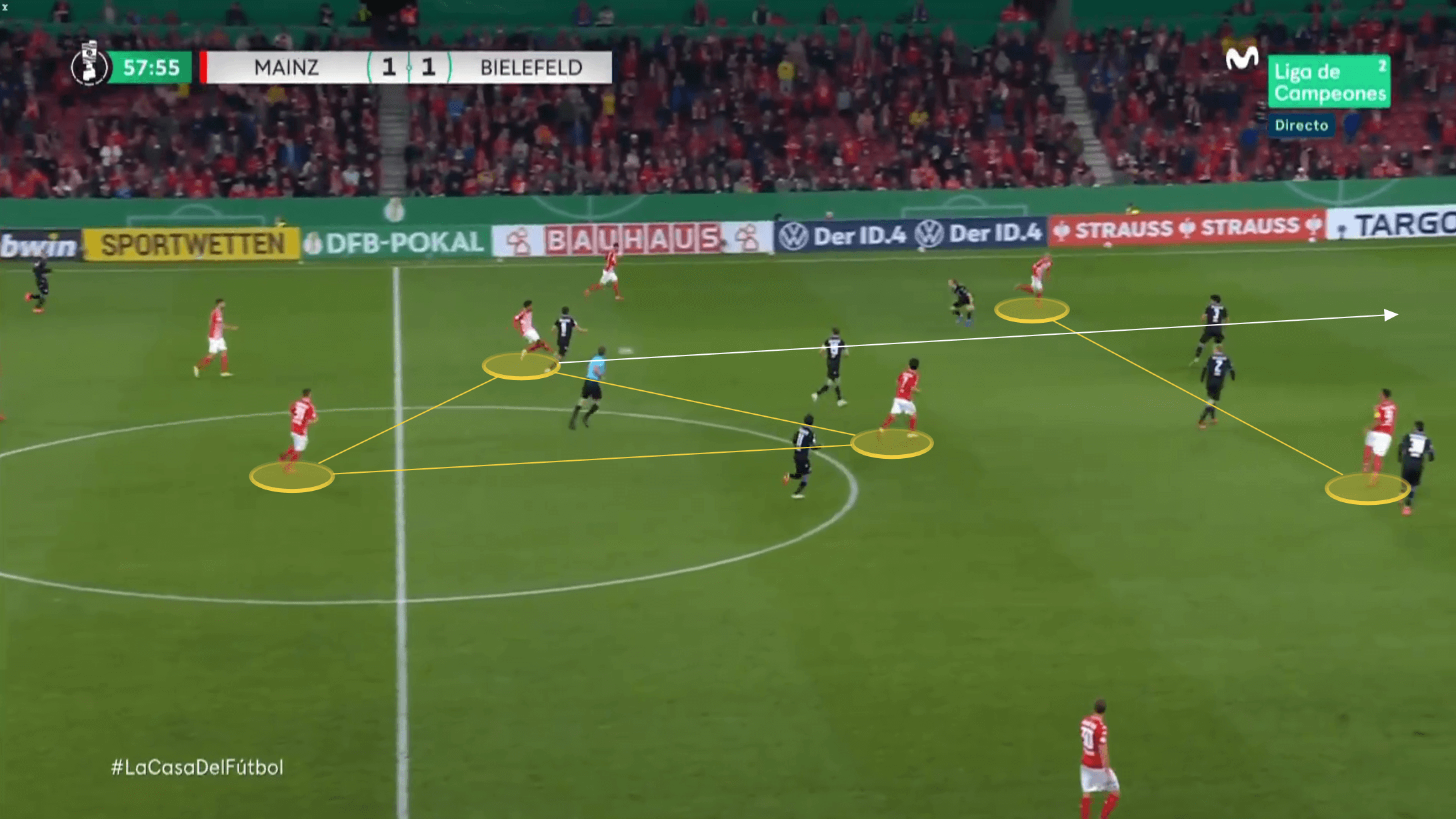

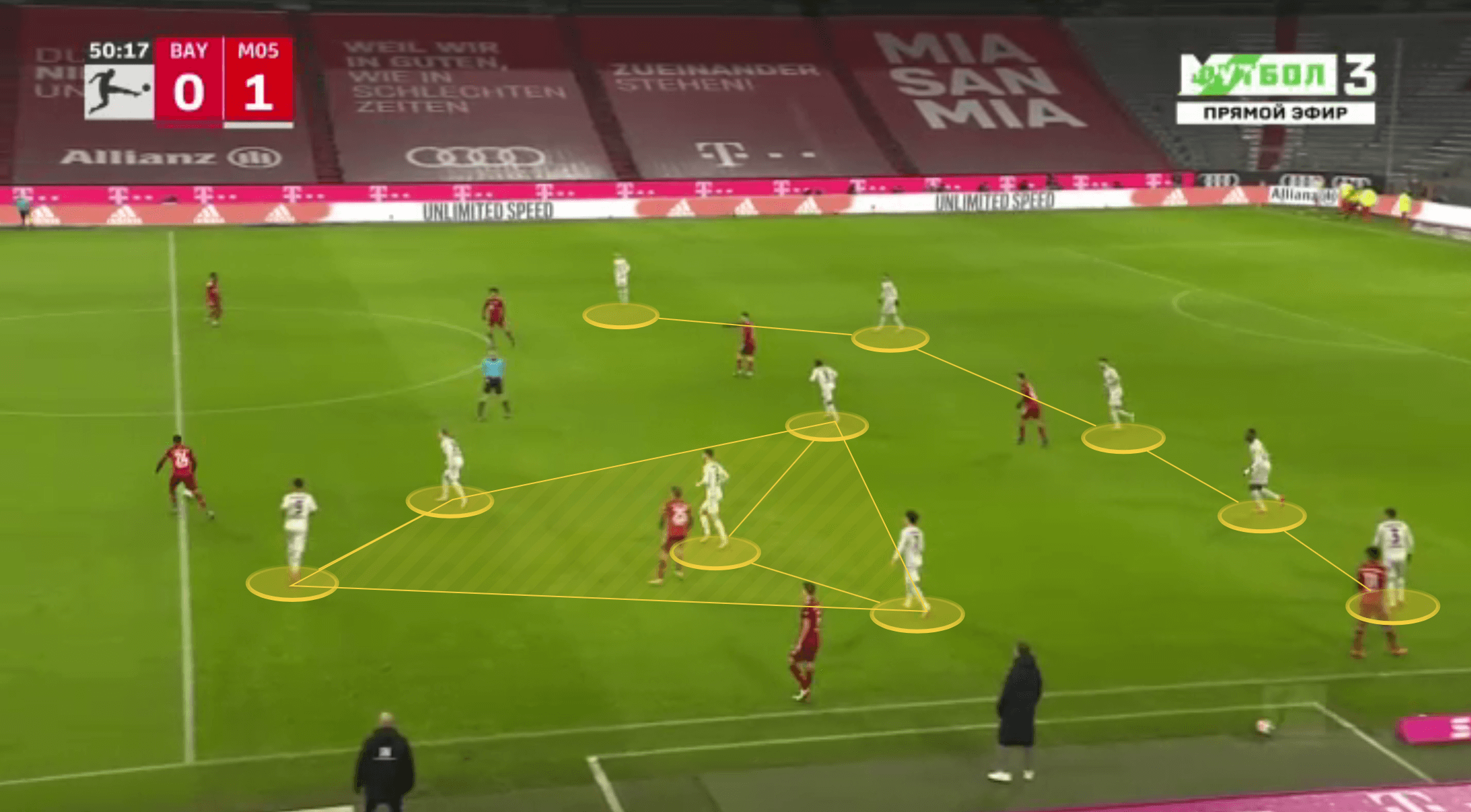

Svensson likes to get his midfield three on the ball relatively early though, and uses them in a compact triangle to ensure possession is retained, whilst also providing a counter-pressing threat if one loses the ball. As a result they can afford to be bold in possession.

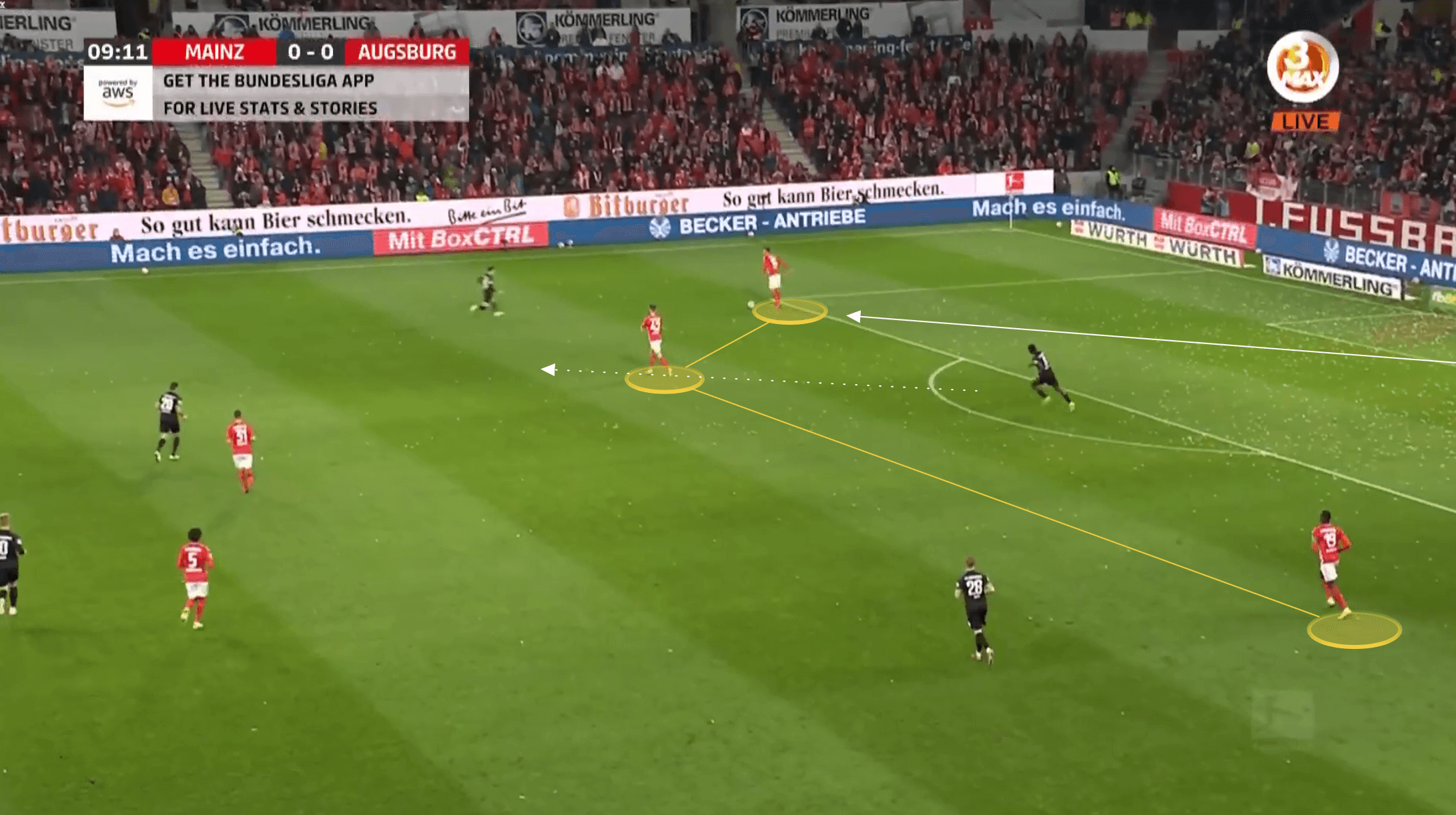

We can see their general shape with one wing-back already high whilst the other begins to move forward as the ball is progressed. There is that tight midfield three and the two centre-forwards ahead of them, ready to make runs in behind.

Svensson doesn’t want his team to engage in needless possession if there is a clear forward pass option on. We can see how quickly Boetius recognises the chance to release Burkadt in the following image, sliding the ball in behind, with Onisiwo already moving into a central attacking position to offer Burkadt the easy pass across goal.

We can see from the previous example but also in the next set of images how close Svensson looks to have his midfield operate to the front line, or perhaps vice versa. He allows the wide centre-backs to carry the ball forward and in doing so Mainz can create a highly congested central area like in the next image.

As they play forward into the front line, the two number eights spring into action and look for flicks off of their front two or simply just engage in quick link-up play to advance attacks. If one of the midfielder’s can’t directly impact play then they are likely to make a run in behind.

Svensson also likes creating high percentage shooting opportunities. And it works. The only league games they have failed to score in have been against Freiburg, and there’s no shame there with them having the tightest defence in the league, and Bayer Leverkusen.

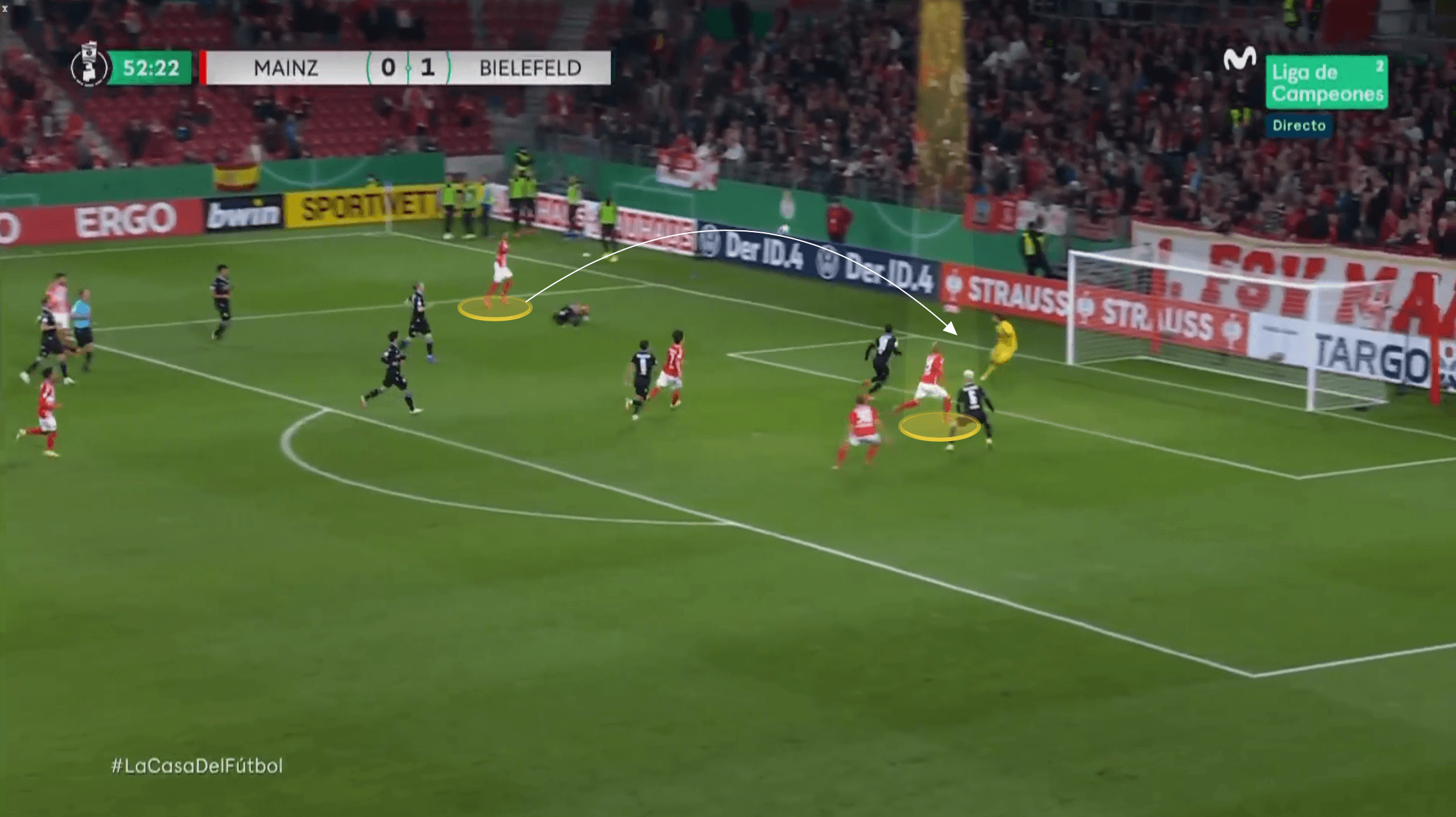

Whilst there have been some quality goals from distance, or smart finishes on the break, there have also been a remarkable number of goals coming from inside the six-yard box. Nine of their 25 league goals at the time of writing have come from this position, and four of their last eight, showing a growing influence on Svensson’s attacking game.

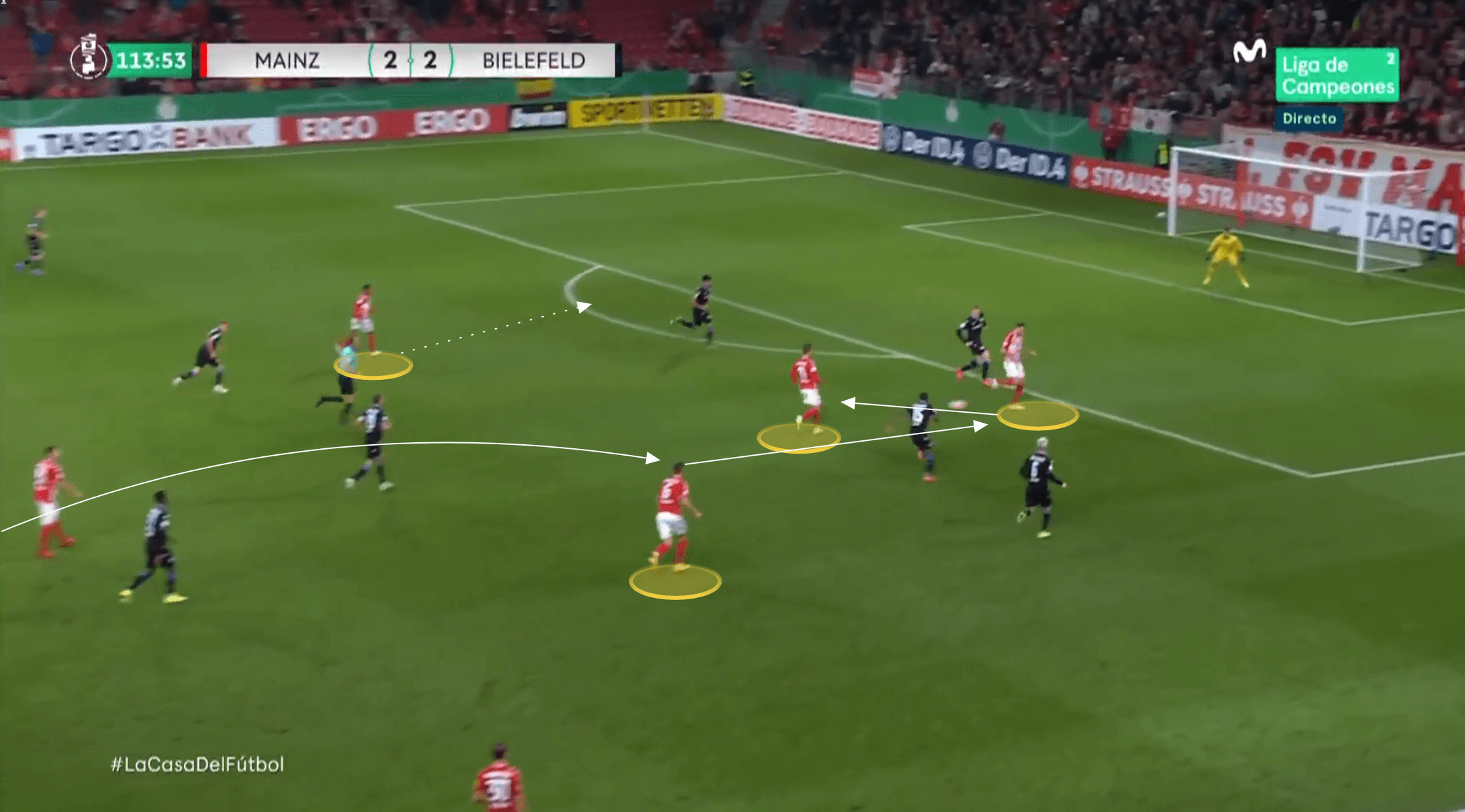

The previous image and the following one are two examples of the kinds of positions that lead to these goals from such close proximity. They are near-identical. Svensson wants the cross to be hit away from the goalkeeper protecting their front post, ensuring they have to shift across their goal rather than come out to claim the ball, whilst the attacker looking to get on the end of it needs to time their run from a deeper starting position, and finish first-time. It is basic, but has proven to be a successful route to goal for Svensson’s Mainz.

Transitions

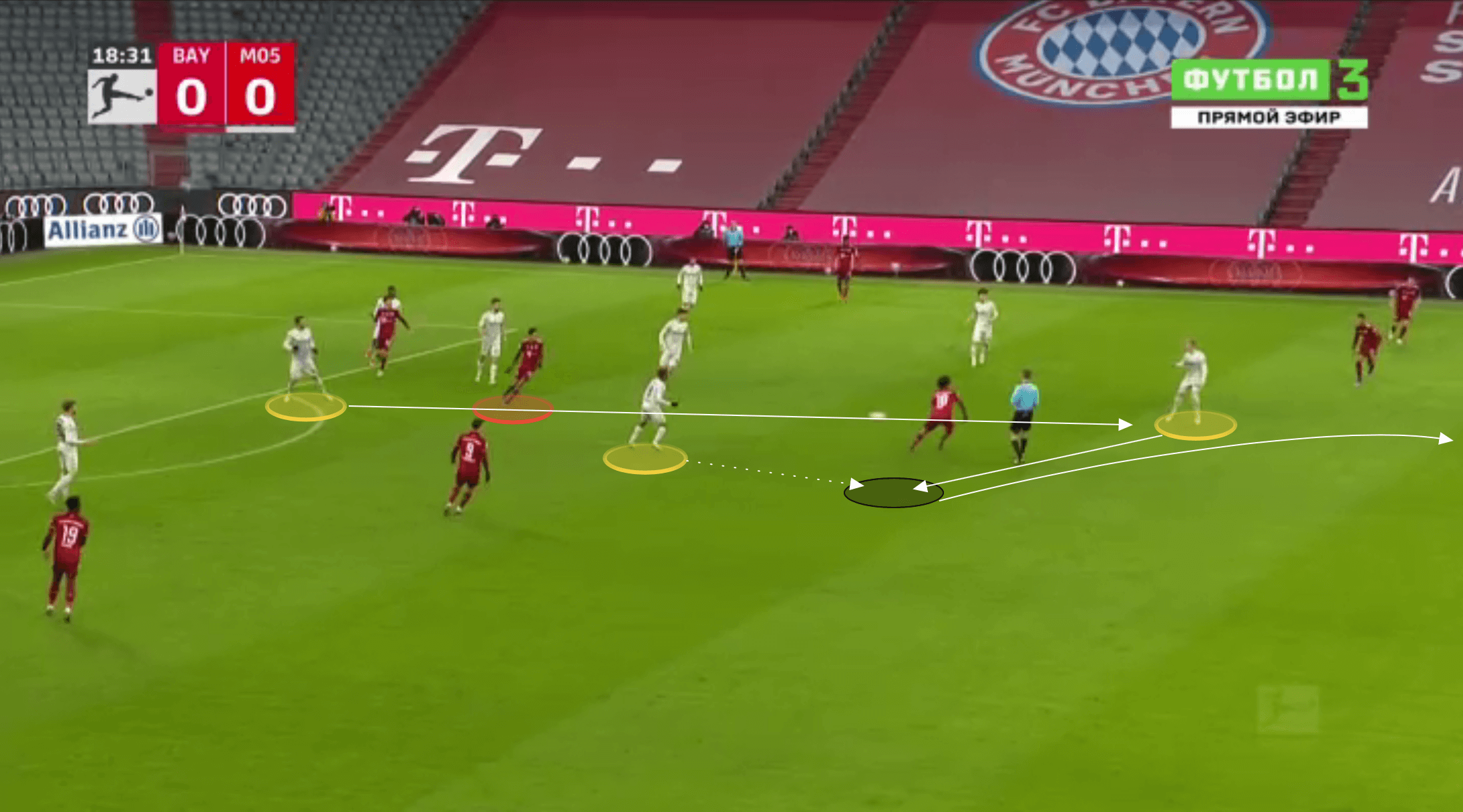

Svensson’s side are a ruthless counter-attacking team. He has a starting line-up filled with pacy players and individuals who can quickly break lines, particularly on transition. Mainz have surely been one of the league’s most effective teams in attacking transition this season, potentially in Europe. An astonishing statistic is that 15 of the 21 league goals that they have scored from open play this season have come within 15 seconds of regaining possession. They frequently work the ball into goalscoring positions even after turning over the ball well inside their own half. Svensson constructs these counter-attacks through sequences of one-touch passing, often using up, back and through pass combinations, however, not exclusively. In the next image we can see a turnover of possession worked into a goalscoring position in three passes. The turnover initially comes in the central channel, where Mainz so frequently regain possession due to their crowding of this area. As we’ve seen already in this analysis, mainz’s forwards are consistently ready to make runs in behind, and Onisiwo is found immediately with the pass in behind whilst Ingvartsen in this case arrives into the centre of the box, ready for the passa cross goal and the easy finish from close range.

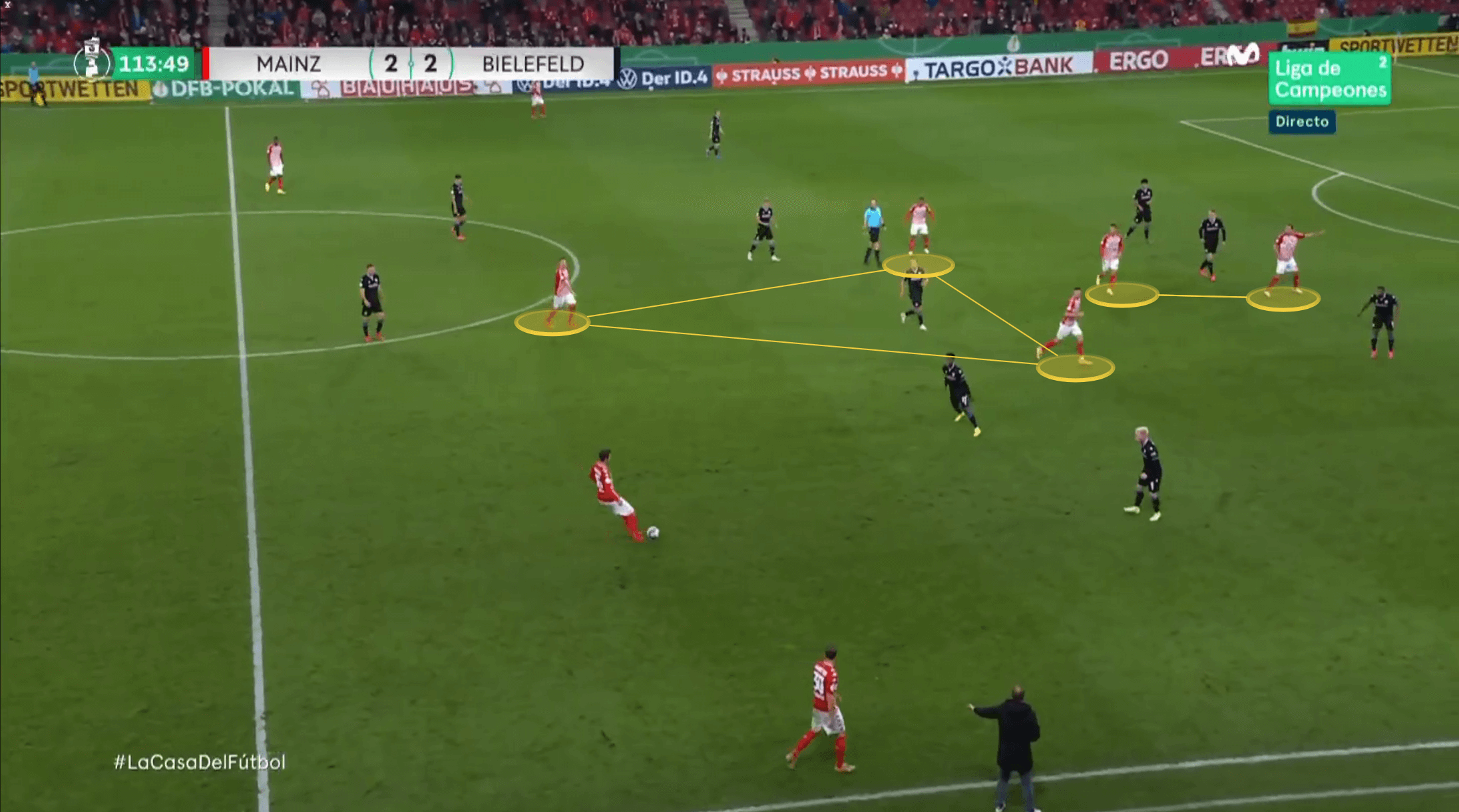

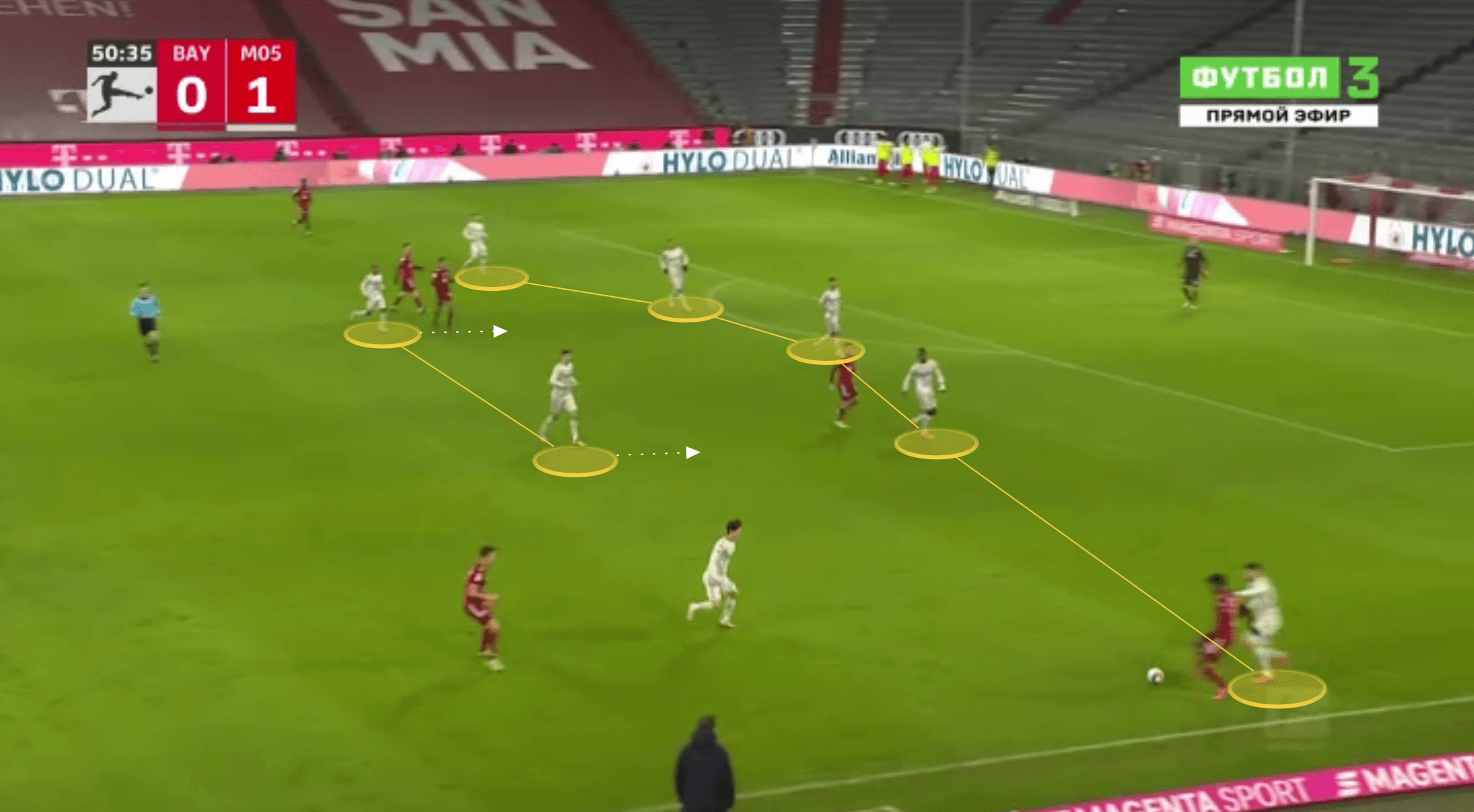

As soon as possession is won, firstly the ball-winners instinct is nearly always to get their head up and look for the most advantageous forward pass available to them. The midfielders look to find space to receive the ball beyond the lines, whilst those around them are already working into a position where they can be a pass option for this player. In the following example the ball is played forward, with the midfield quickly exchanging the ball with one touch passes, before the direct ball in behind is played. Svensson isn’t reconstructing the wheel with this kind of football, but he has his Mainz side so well drilled in this aspect of the game that they are utterly ruthless with it, even against the highest level opposition.

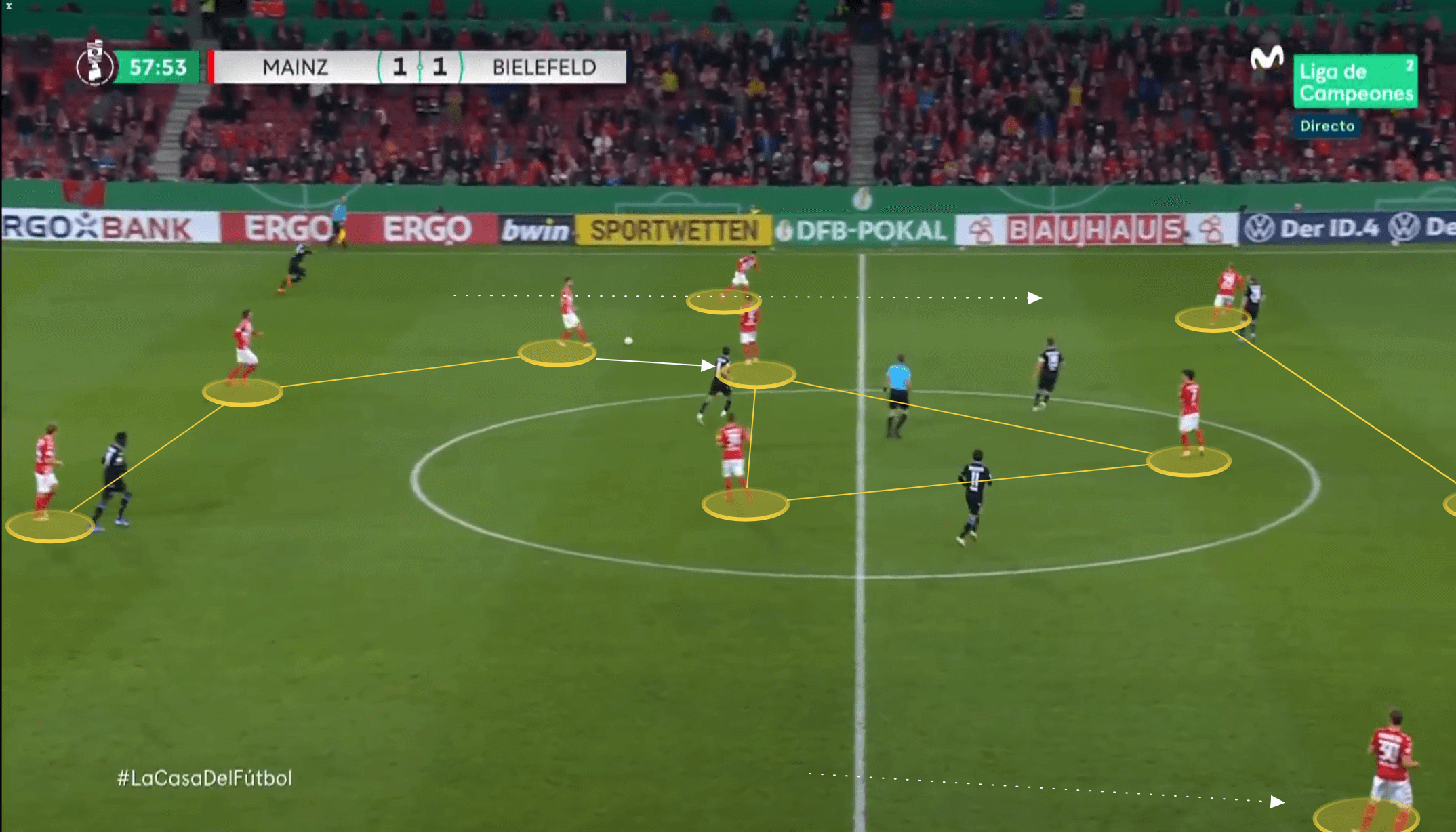

On defensive transition they are equally impressive and well drilled. They refuse to let an opponent have easy possession after a turnover of the ball, and the closest player to the turnover is expected to counter-press. Whilst they do so the rest of the team track back, keeping a compactness as they do. This includes the forwards.

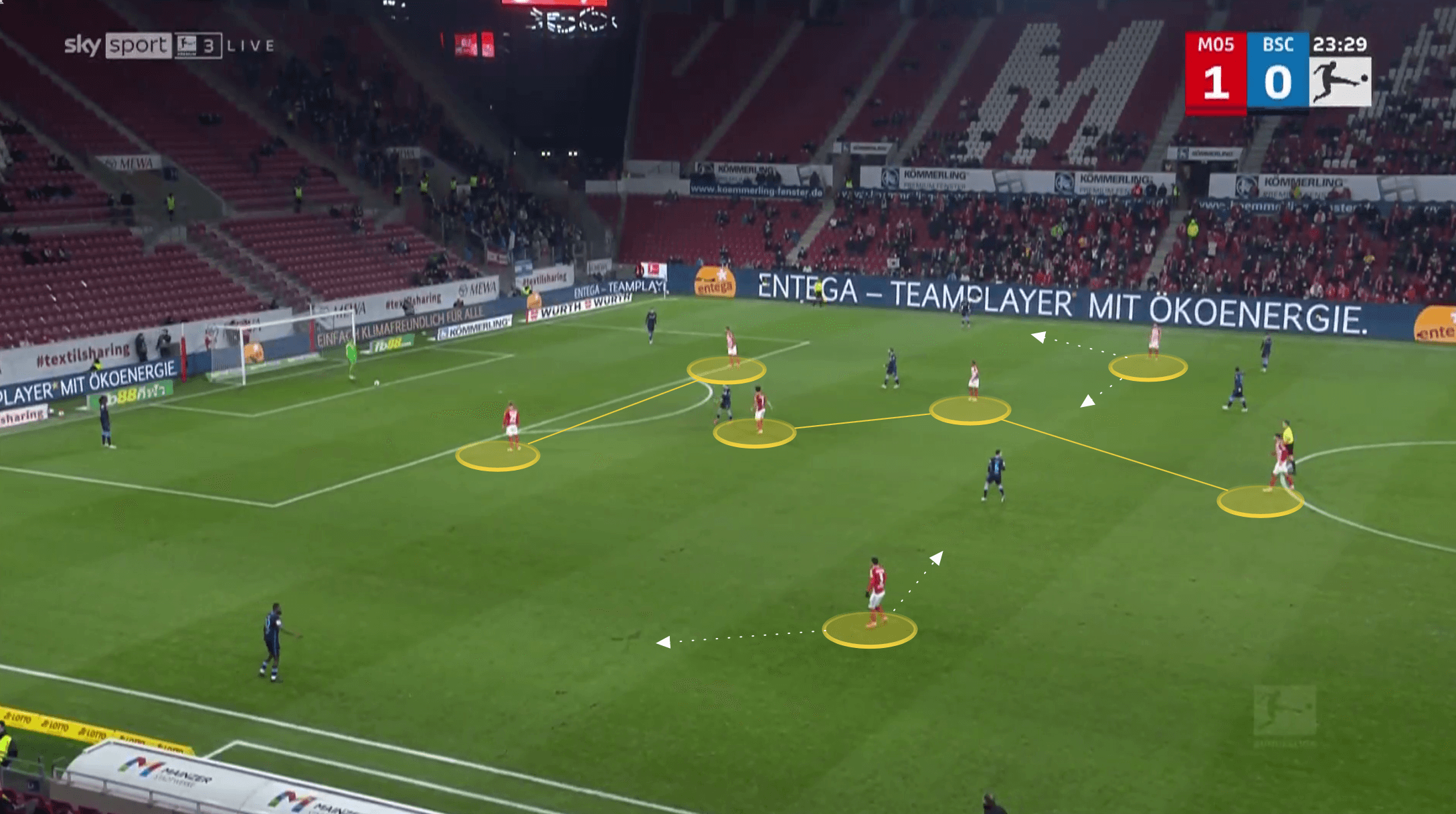

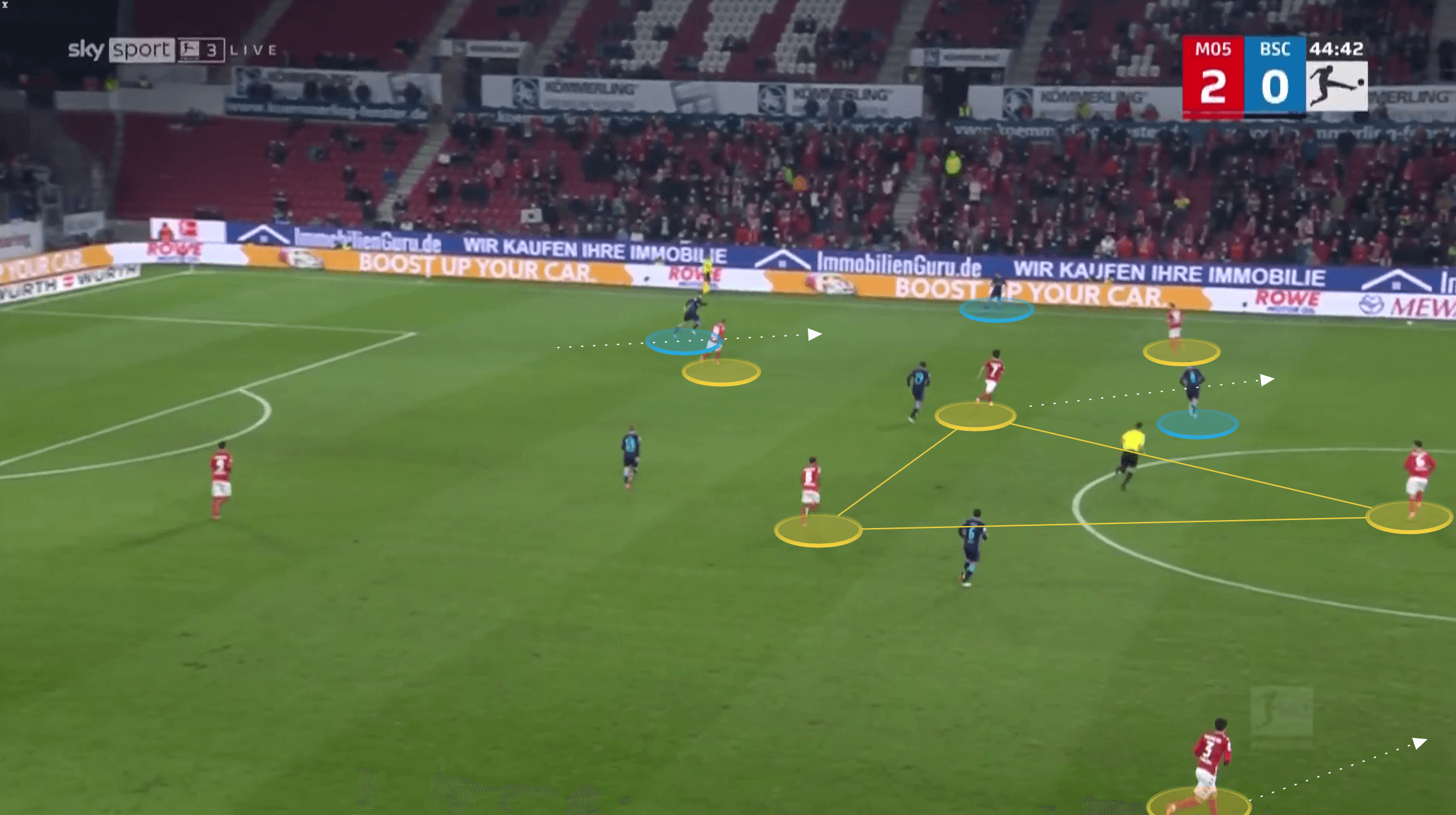

Everyone tracks back, you can even see the midfielders tracking the run of the BSC player running through the middle even in the following example. This is whilst the wing-back steps forward to counter-press, and the players immediately around him either cover him, provide pressure as well, or pick up a potential pass option.

Mainz are incredibly disciplined in doing this whenever they lose possession and they make it highly difficult for the opposition to secure possession on transition.

Svensson allows his centre-backs to be aggressive in this moment too. Frankly, it is a highly risky move, and whilst this isn’t a constant thing, they step forward enough, leaving a 2v2 and toying with an offside trap, that it could be exposed. However, the centre-backs will only do this if the midfield is played through. The following example highlights this, firstly showing their overall compactness after a loss of possession. The two midfielders closest to the ball immediately get compact, but of course this isn’t always enough to stop a counter, and in this example they are played through. We can see the left-sided centre-back stepping forward to press the ball, and whilst he does have his wing-backs tracking back either side of him it does nevertheless leave a 2v2. However, in this case he is successful in winning the ball, and Mainz actually score immediately after the turnover.

Out of possession

Mainz are incredibly impressive defensively. Other than Freiburg’s 15 goals conceded in the league, Mainz have the next tightest defence, along with Bayern Munich, having conceded just 16 goals at the time of writing.

And yet they don’t sit back and put men behind the ball. Svensson is committed to pressing high and winning the ball in areas where they can then capitalise on transition and score goals from. As we’ve seen, this is an approach that is working for them.

Their 9.29 PPDA from this season backs this up, showing they are an intense pressing team, and yet they don’t just provide pressure and intensity, but are also highly effective at regaining possession through winning challenges. Their 63.1% defensive duel win rate is the second-highest in the league.

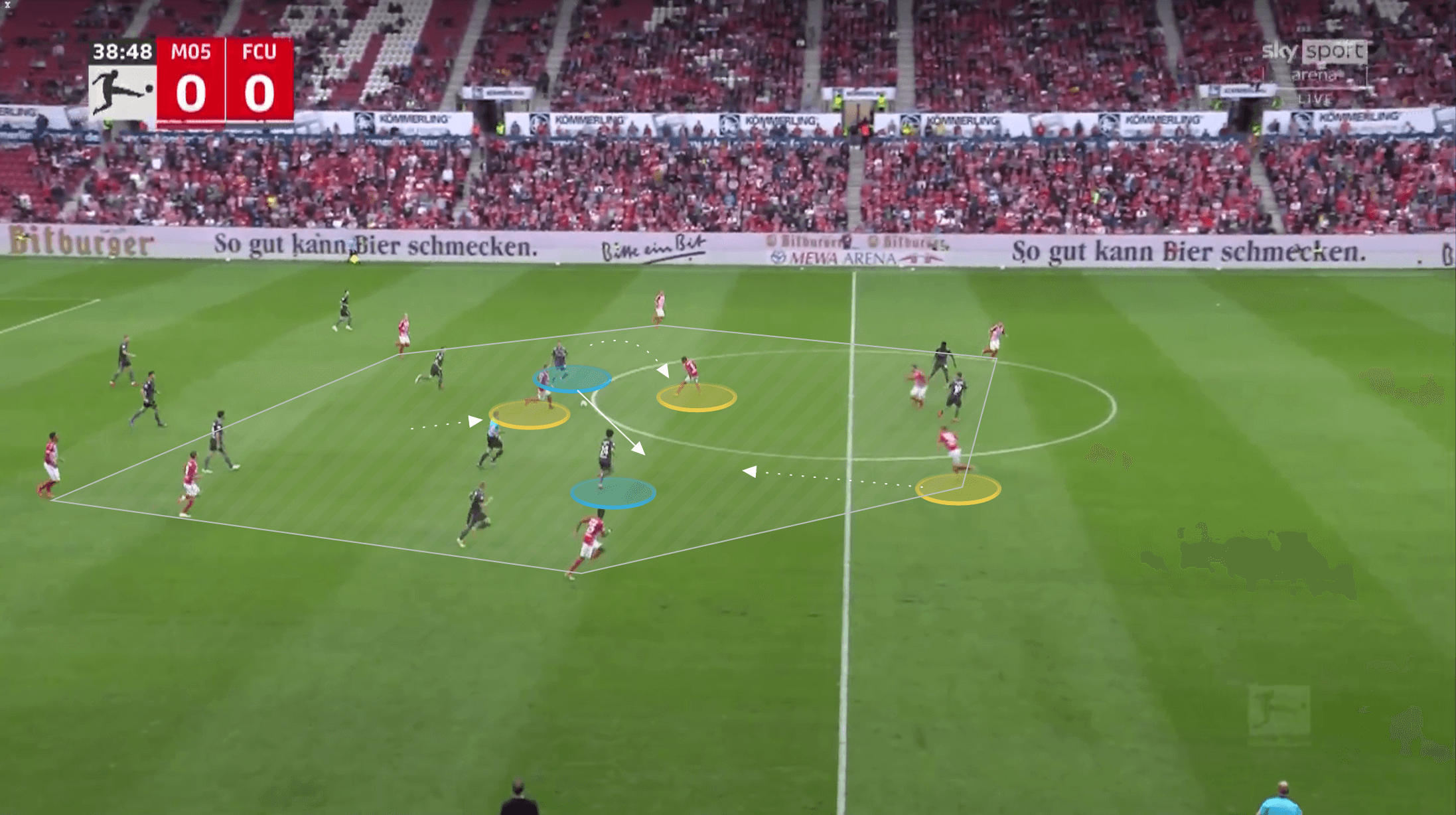

Svensson has his team set up to press in a narrow structure, with the two forwards leading the press, closely supported by a staggered midfield three. The wing-backs start very high, tucked inside to prevent passes in between themselves and their midfield three, but in a position where they can press out wide if necessary, in a half-and-half starting berth.

When the opposition work the ball the front two will work together to prevent easy inside passage, whilst the wing-back will push forward also, closing down the opponent’s space in this area and also preventing an easy pass. The two number 8’s work across the pitch, picking up any potential inside passes themselves, whilst the far-side wing-back drops back and tucks inside to provide balance.

The midfield three look to keep this central compactness at all times, working together to prevent any kind of central passage for the opposition. However, they have to be flexible too. Svensson doesn’t want his wing-backs getting drawn forward unnecessarily and conceding space down the wing either. We can see how the wing-back Widmer holds his position in the next image due to the wide presence of the opposition full-back but also because of the central-midfielder inside him ready to creep into the space behind. This leaves the Mainz forward in this example to have to work on the BSC centre-back in possession and the wing-back can’t step until his inside central-midfielder drops behind him to pick up this opposition midfielder.

So whilst they are intense, they are also positionally disciplined.

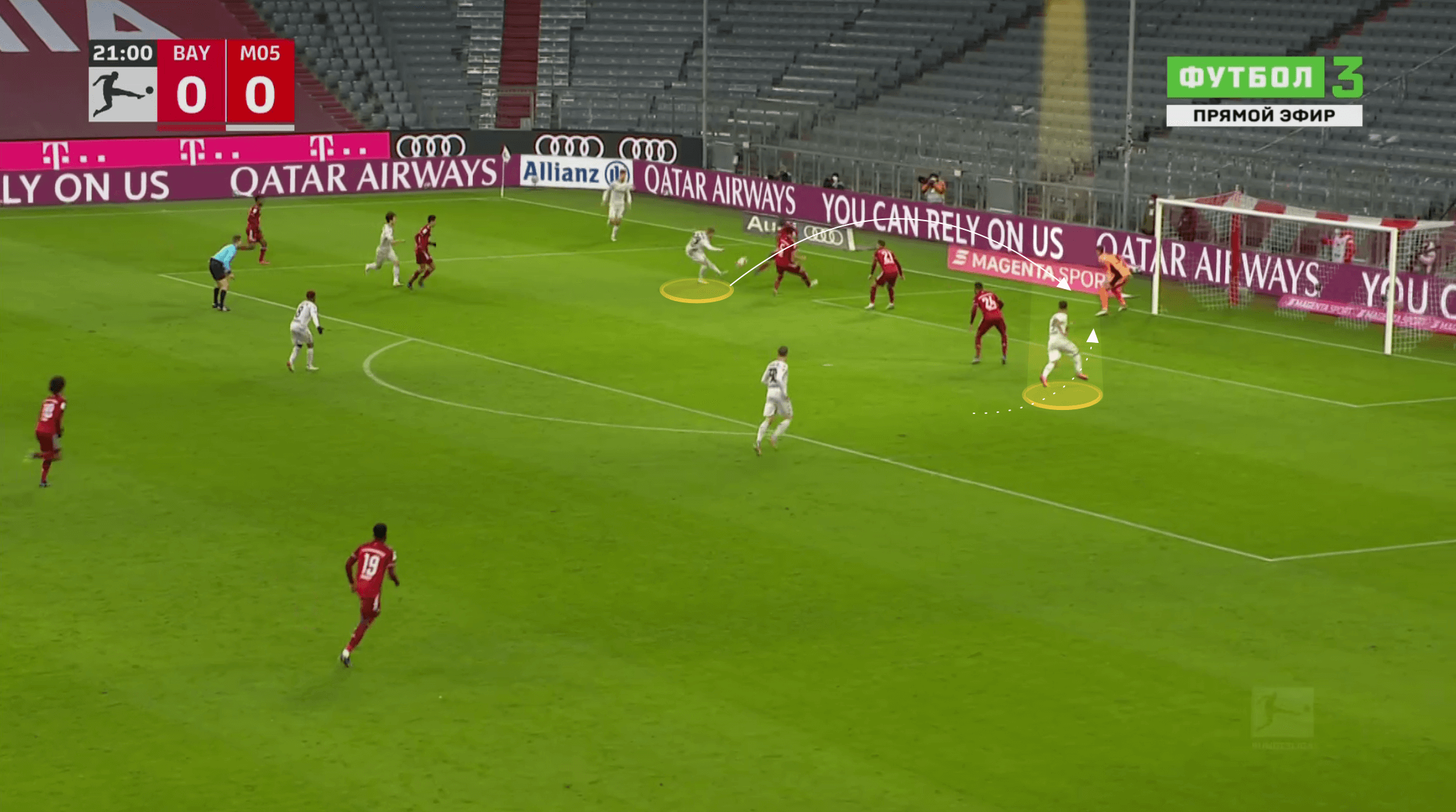

Mainz will press high straight away from opposition goal-kicks and are aggressive in their attempts to regain possession in high areas, regardless of who they are playing against. The centre-forwards are clever with their positioning and if they can cut off the opposition centre-backs through their pressing angle, as they do in the next image, whilst the midfield are able to mark central space and prevent the keeper from playing out through this way, unless the keeper plays long, they can force errors. They did exactly this against Borussia Dortmund earlier this season, scoring late on and forcing the keeper to try and play pass the press, with the Mainz right wing-back intercepting the ball in this example.

The obvious advantage of regaining possession in such an area is immediately having four attacking players in the central channel ready to receive the ball, whereas the opponent are spread relatively wide having just lost possession.

In deeper areas Svensson has his midfield three and front two continue to work in tandem as a tight block of five, working across the pitch together to protect the central channel.

The wing-backs support them and are given the freedom to push high or wide to provide a defensive presence and in doing so they prevent this five from having to shift across the entirety of the width of the pitch, providing them respite in wide areas.

When a wing-back is drawn wide or forward, Svensson is comfortable operating with the back four separate from this wing-back, however any central-midfielders near to the back four are expected to provide vertical compactness and prevent any space in between the lines.

Conclusion

Svensson is still early in his career as a Manager at Mainz let alone in general and so whilst what we are currently seeing isn’t far from that Red Bull philosophy he worked on for two years at Liefering, he is still adding his own touches and brand to this style of play. However, what can’t be ignored is that whilst he has a talented side he is undoubtedly pulling the best out of them and truthfully has them performing well above what many anticipated. Clearly his style of football suits his current group of players, and it is a system they have bought into. It would be of no surprise to see Mainz push for European football as the season progresses, as Svensson continues to grow his reputation as an exciting, young manager.

Comments