There isn’t a great deal left to be said about the genius of Christian Streich within the German media. The Freiburg Head Coach has been in charge of the club since 2011; even before then, he was the assistant from 2007 and worked with the U19’s for 16 years previous. There are few people, if any, who know Freiburg like Streich.

Besides one relegation that was immediately rectified by winning the 2. Bundesliga the following season, Streich has continuously managed to navigate a shoestring budget and have Freiburg finish in respectable positions from year to year in the Bundesliga, with three top-half finishes since 2011. Whilst they have qualified for a European competition before with Streich, thanks to their fifth-place finish in the 2012/13 season, they are pushing to gatecrash the top four this season. At the time of writing, after eight games, they sit in fourth place in the Bundesliga on 16 points, just three away from leaders Bayern Munich.

Looking around them, they will feel confident that they can best other teams on nearby points as the season progresses. Bayer Leverkusen, for example, sit in third place on the same points but with greater goal difference, yet they have vastly exceeded their xG thus far this season, and it’s unlikely they will be able to continue such form. Wolfsburg, who qualified for Champions League football last season, started this campaign well, only to fall to three defeats in a row in their last three games.

Whilst Freiburg regularly have far less to spend than their league rivals, they continue to recruit well, and whereas there are some English managers heralded for their ability to forge results from a small budget, they don’t play the football that Streich has his Freiburg team playing. In a starting XI with few household names outside of Germany, Streich’s side play a patient but vertical style of football with constructed counter-pressing and counter-attacking moments, as well as intelligent and aggressive pressing where they defend from the front. This tactical analysis will give an analysis of the tactics that Streich is using this season with Freiburg as he looks to achieve the unlikely and qualify for Champions League football.

Freiburg shape and line-up

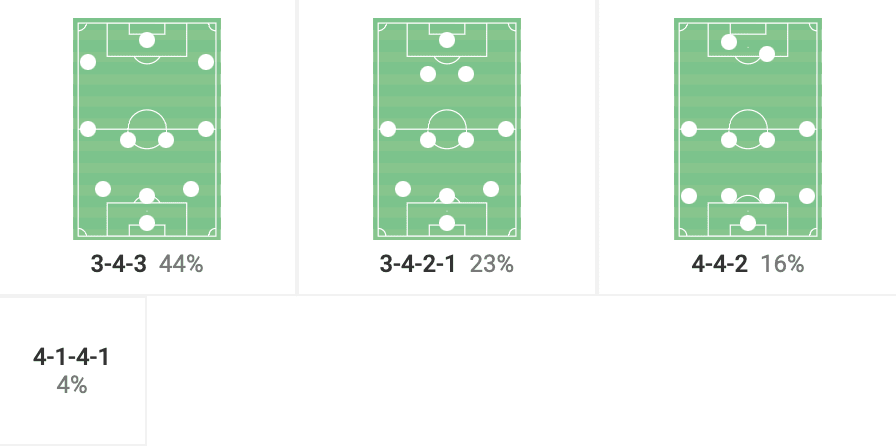

Streich has regularly used a back three with Freiburg and he has continued to do so this season, with a 3-4-3, or variation with the 3-4-2-1, his heavily preferred formation. The image below shows us his preferred formations from this season.

Seymour1

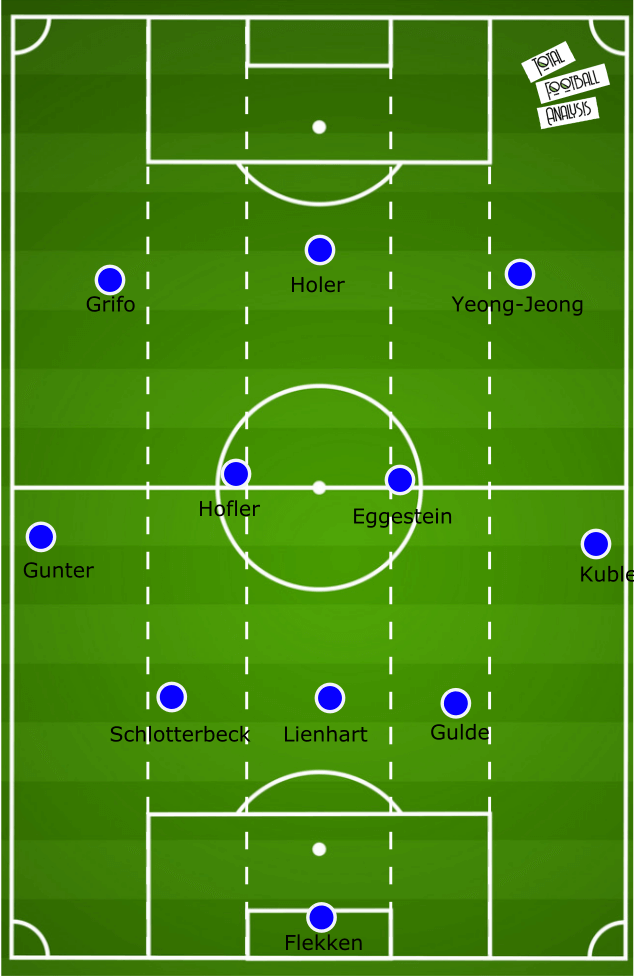

As for Streich’s favoured personnel within this formation, this can and has varied. Mark Flekken has made the number one spot his own, after Florian Müller’s loan move wasn’t made permanent after last season. As for the back three, it has been pretty settled with Manuel Gulde, Philipp Lienhart, and Nico Schlotterbeck. Jonathan Schmid has been displaced by Lukas Kübler at right wing-back and captain Christian Günter has naturally been an ever-present at left wing-back.

The midfield pairing has varied, with Janik Haberer and Yannik Keitel getting regular minutes. However, Nico Höfler and Maximilian Eggestein have been minimally preferred in this position.

Whilst Roland Sallai, Kevin Schade and Ermedin Demirović have contributed in the front three, Streich has preferred to use Vincenzo Grifo, Woo-Yeong Jeong, and Lucas Höler. Höler hasn’t been prolific in front of goal, but has led the line well despite this, and has restricted Demirović to substitute appearances, whilst club legend Nils Petersen has made just a handful of cameo appearances.

Rotations ahead of the ball

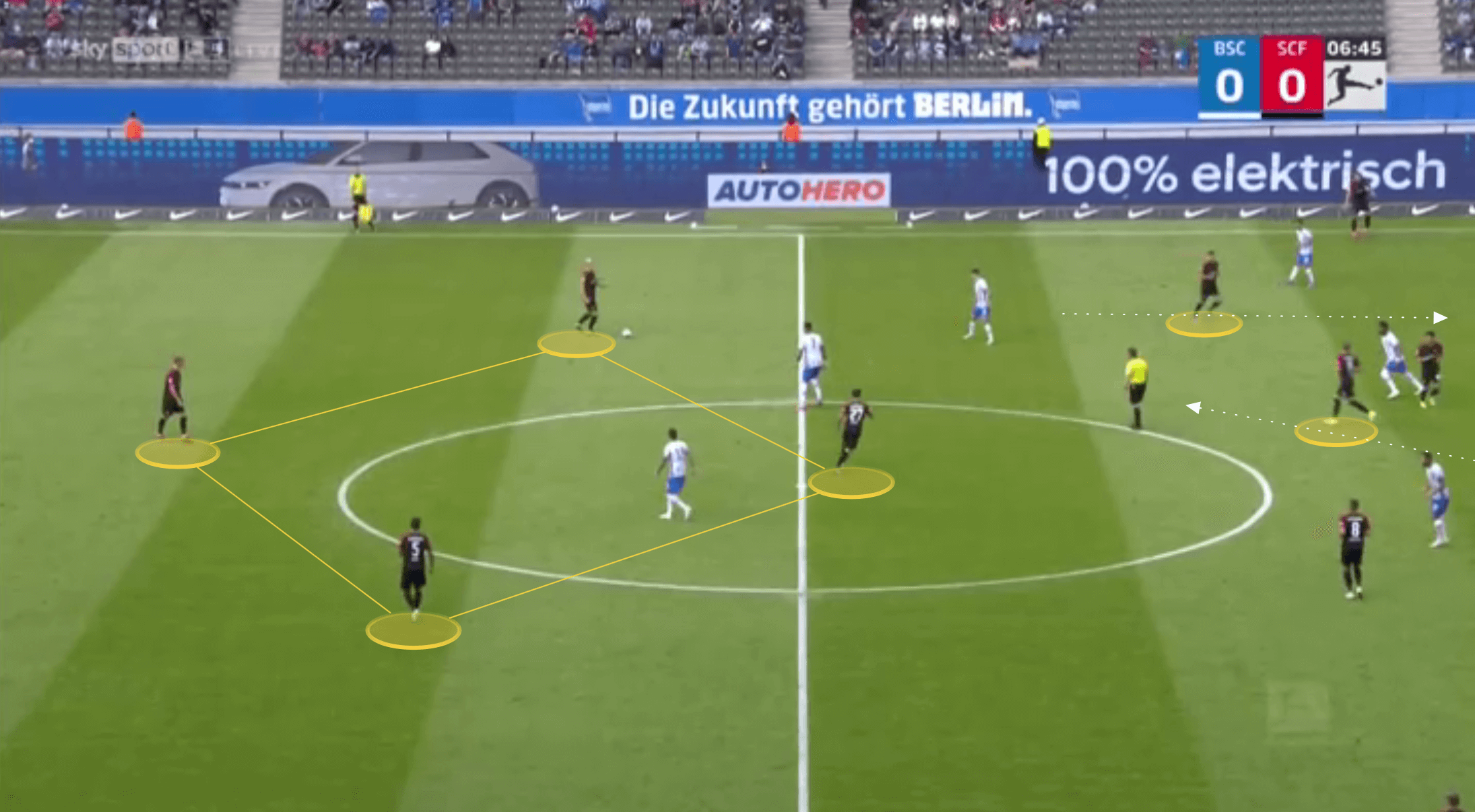

Freiburg build up with a compact back and one of the midfield two sat just in front of them, giving them a diamond formation. This strong base allows both wing-backs to push forward to give the width and height to their attack, whilst Freiburg’s remaining attackers tend to cluster together in a relatively narrow group.

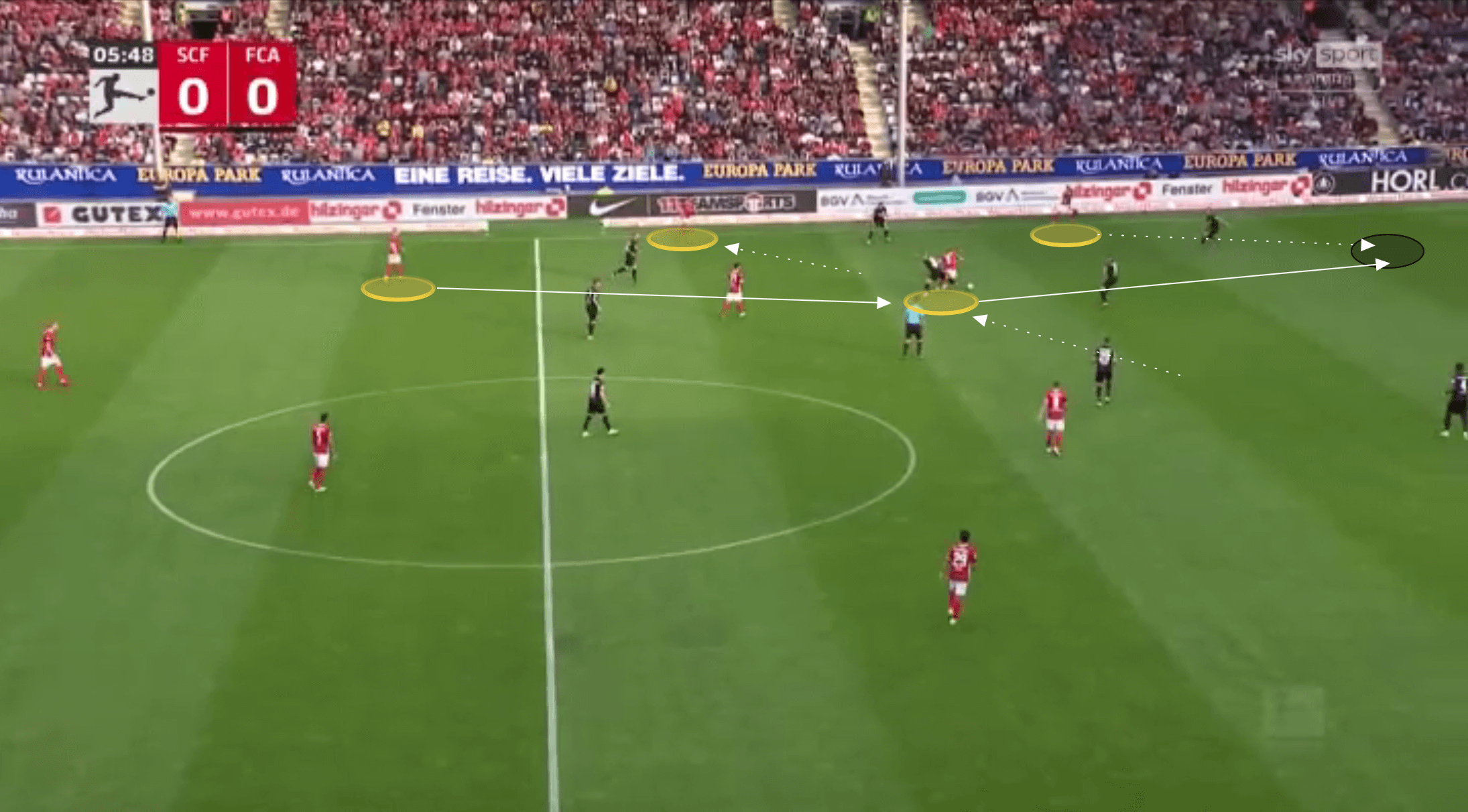

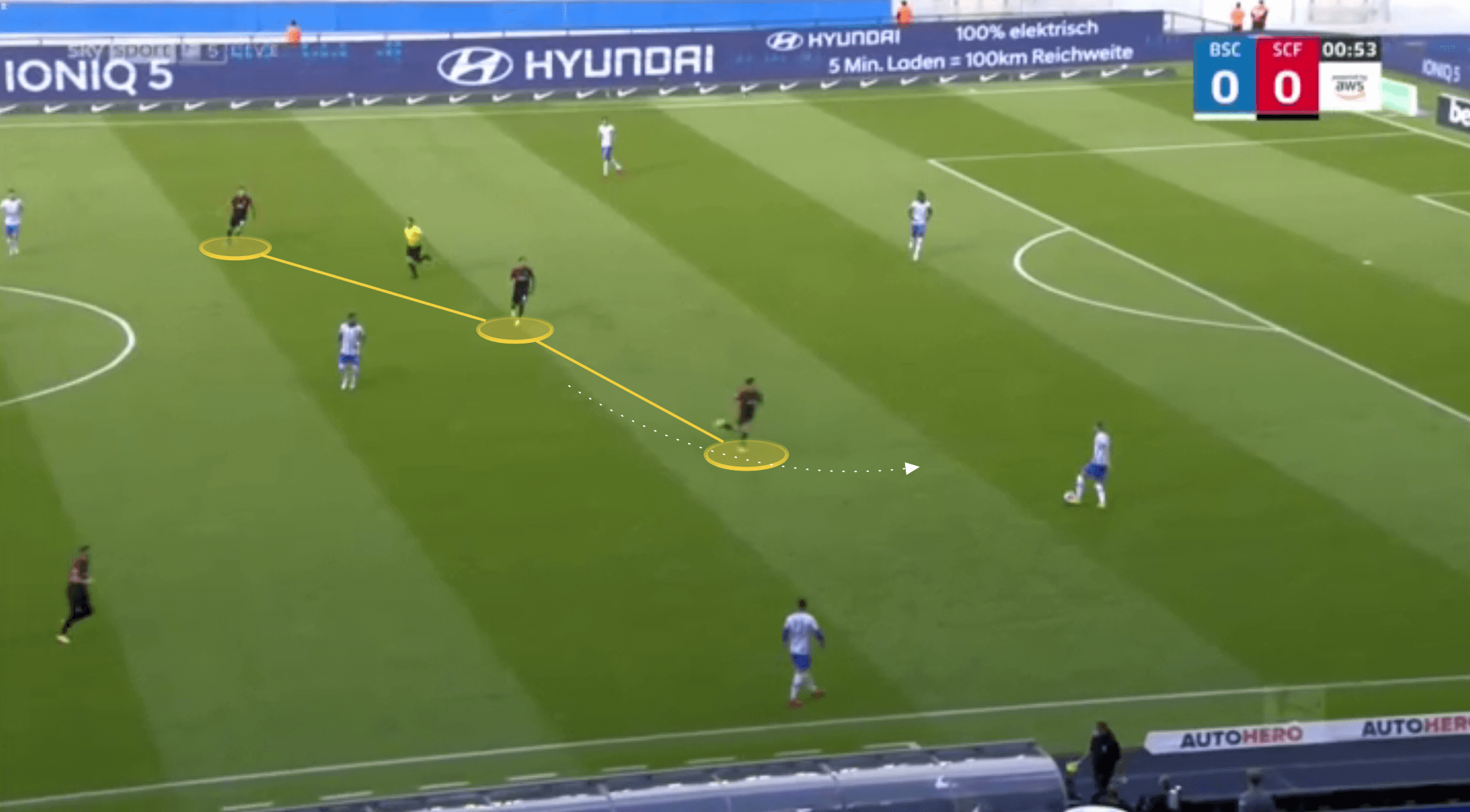

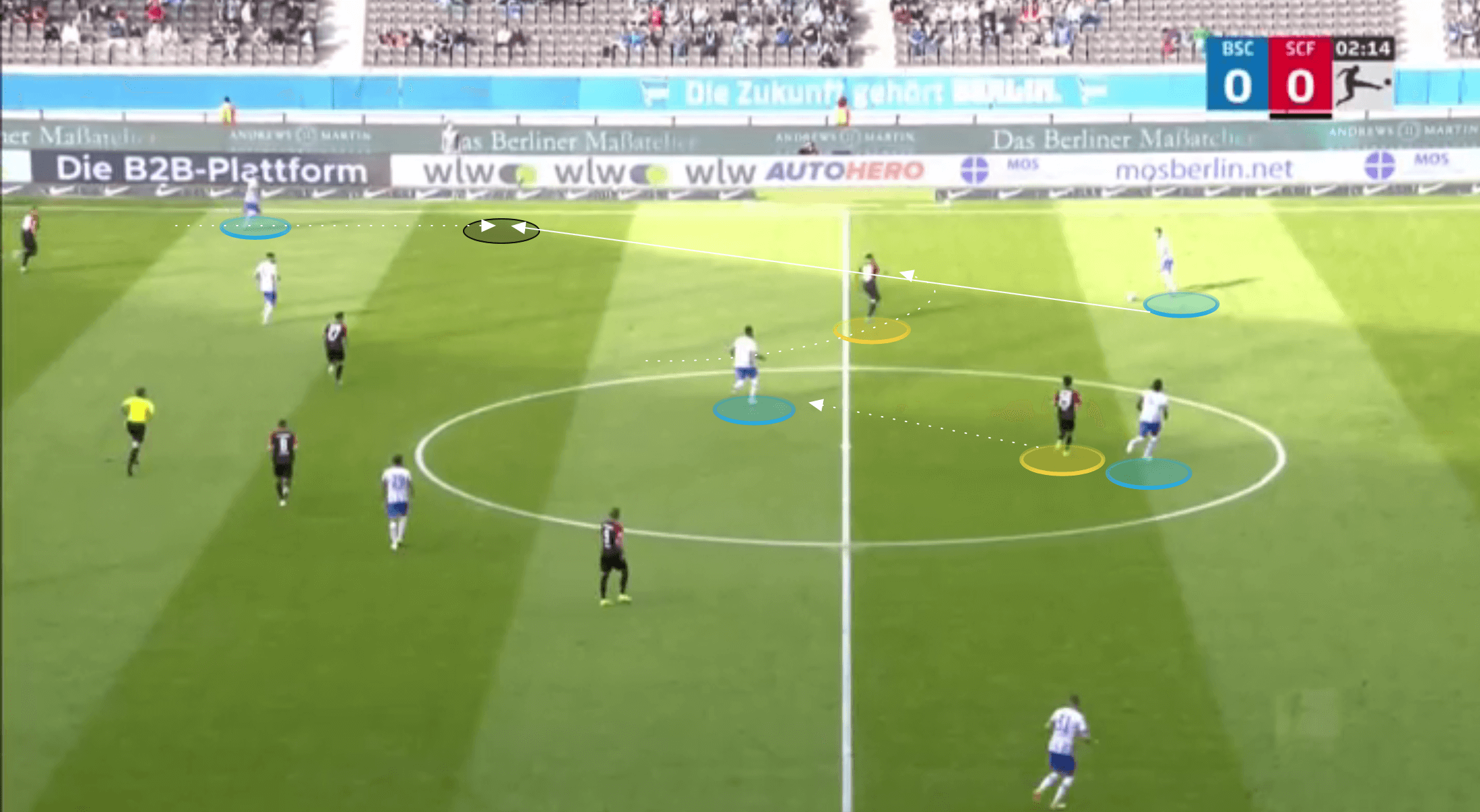

Firstly, Streich uses this narrow three to open up interesting passing lines from these positions. We can see in the following image how the wide centre-backs are in a vantage point where they can break the lines and play inside into a central position, play directly over the top in the half-space, or out wide to their near-side wing-back. We can also see the positioning of this central group of attackers.

Streich has his players continuously dropping in and out of the last line of the opposition defence, with them aiming to draw defenders out with them wherever possible. In the image, we can see Höler dropping into midfield where he can provide a short passing option, whilst the midfielder, Grifo, pushes forward into the space Höler has just vacated.

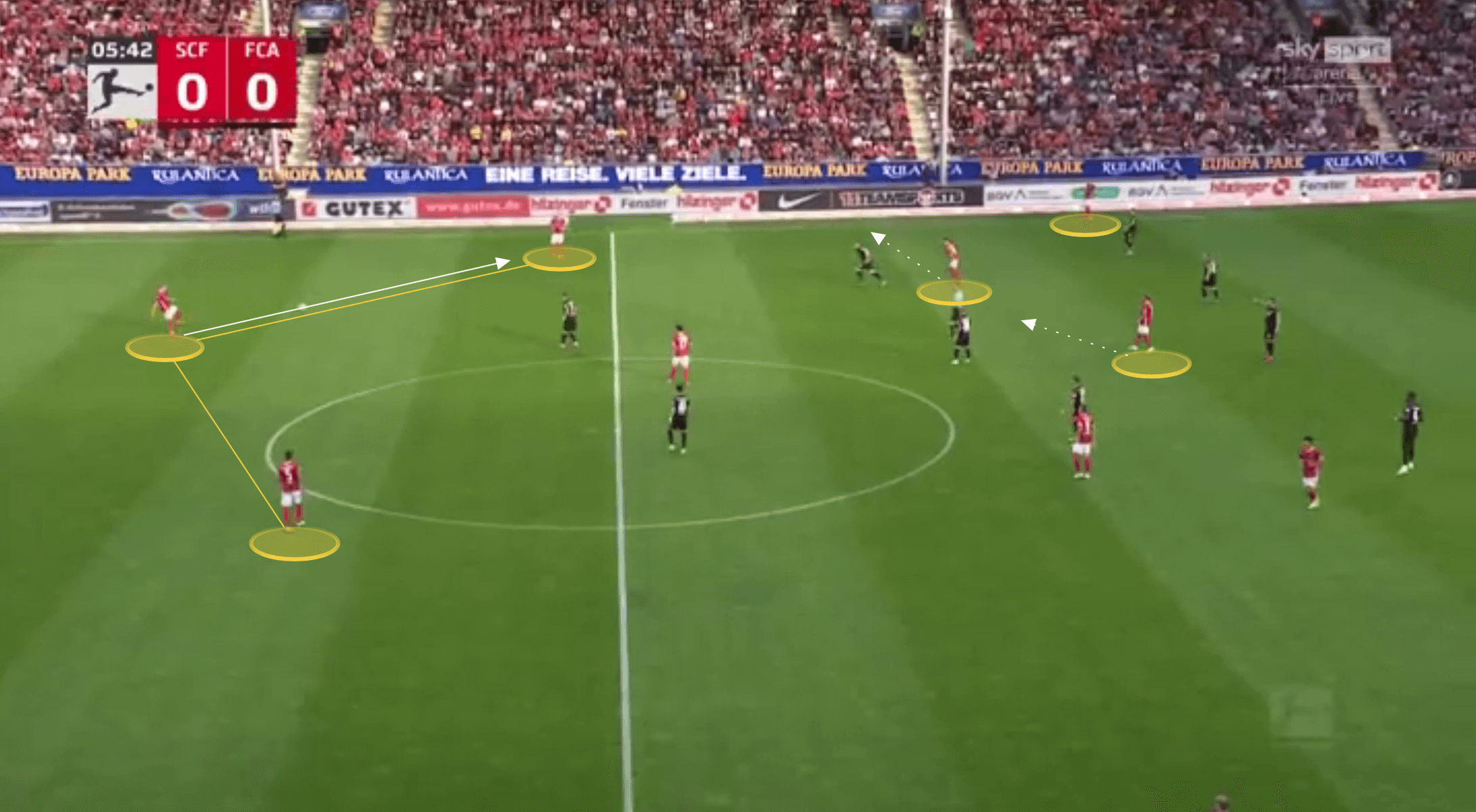

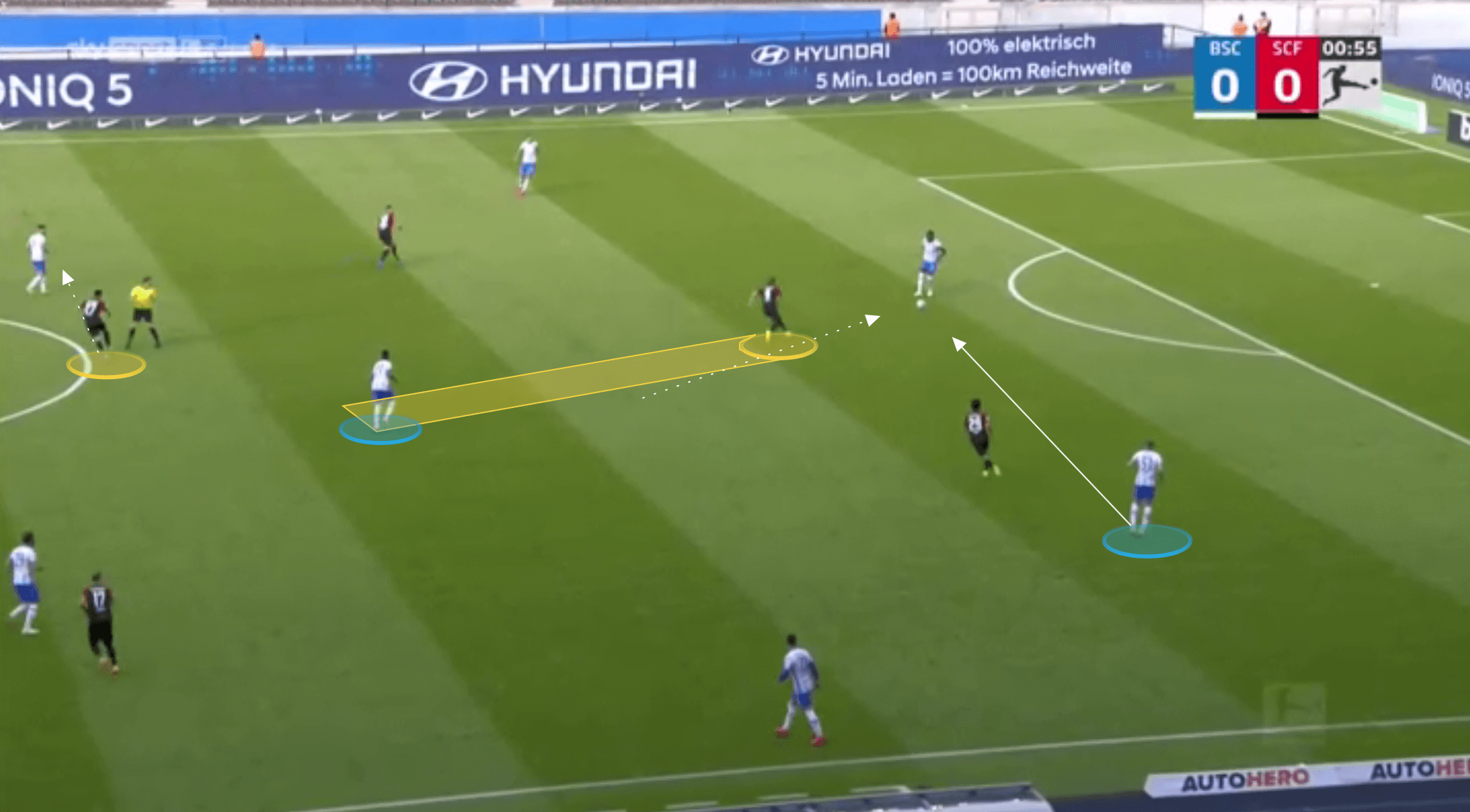

Grifo, or whichever player is operating in that left wide-forward position, will mostly operate inside, with Günter pushing all the way up. If Freiburg circle possession down the left-side, with Schlotterbeck pushing wide from his left centre-back position, Streich’s side look to use smart rotations to advance possession down the left flank. Grifo will actually push out wide but beneath his wing-back where he can receive in space. As this occurs, his centre-forward, Höler, will then shift into the space vacated by Grifo. We can see this pattern occurring in the next image.

In this instance, Schlotterbeck bypassed Grifo’s run, using his run to instead access the space inside. As Höler received he could then play in behind for Günter.

A variation of this occurred in the same game against Augsburg, this time with Grifo receiving the pass out wide. He was then able to use this angle to thread a through pass into the gap between Augsburg’s right-back and right-sided centre-back for Günter to angle his run inside.

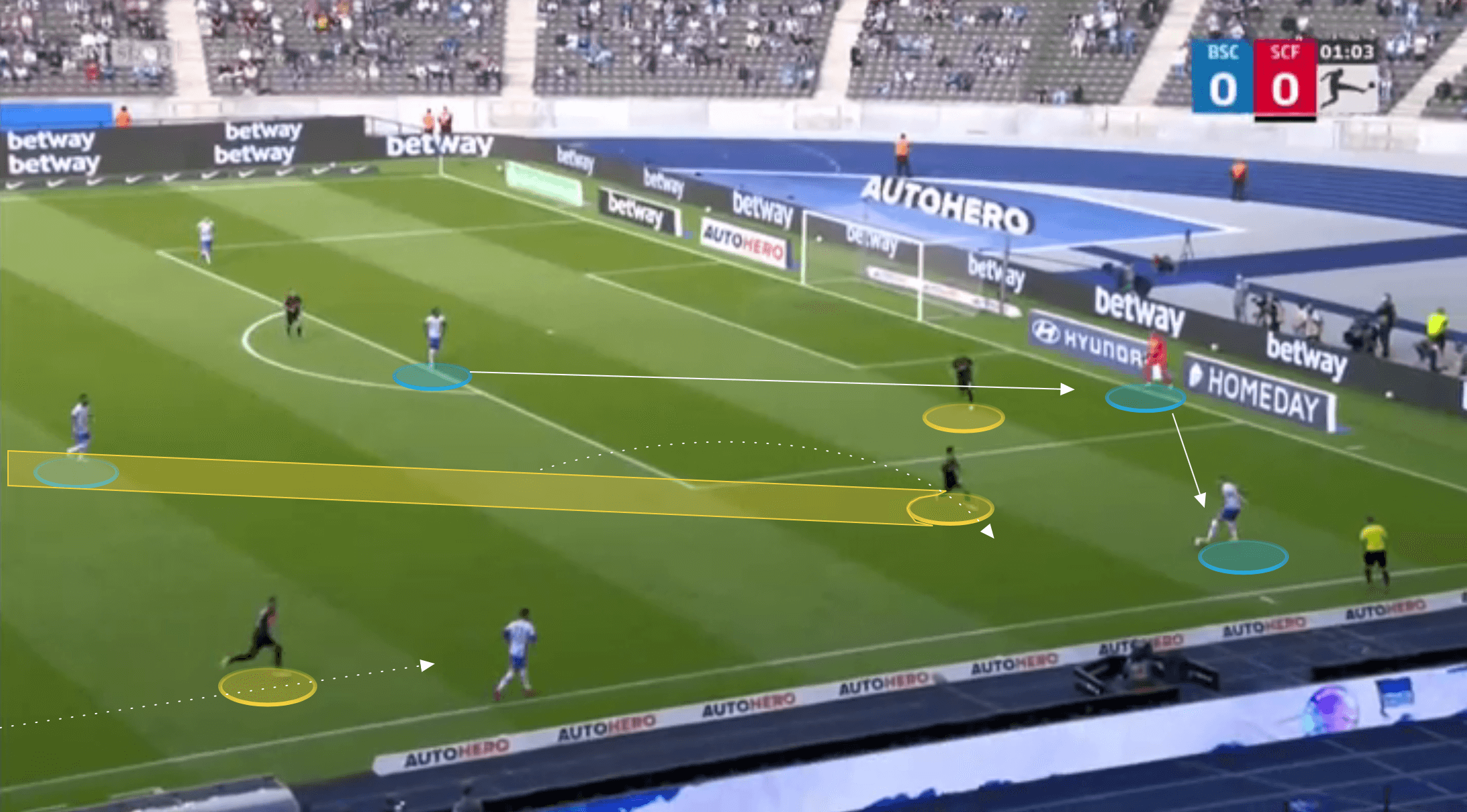

Whereas the previous examples have often shown just one or two players rotating into different spaces at one time, the reality is very different. Streich’s attack operates with a highly fluid shape where one movement sets off a chain of many, with players instinctively filling the spaces left by their teammates. It isn’t necessarily as simple as moving into a space one player has left either. Streich wants his players operating on different horizontal lines firstly.

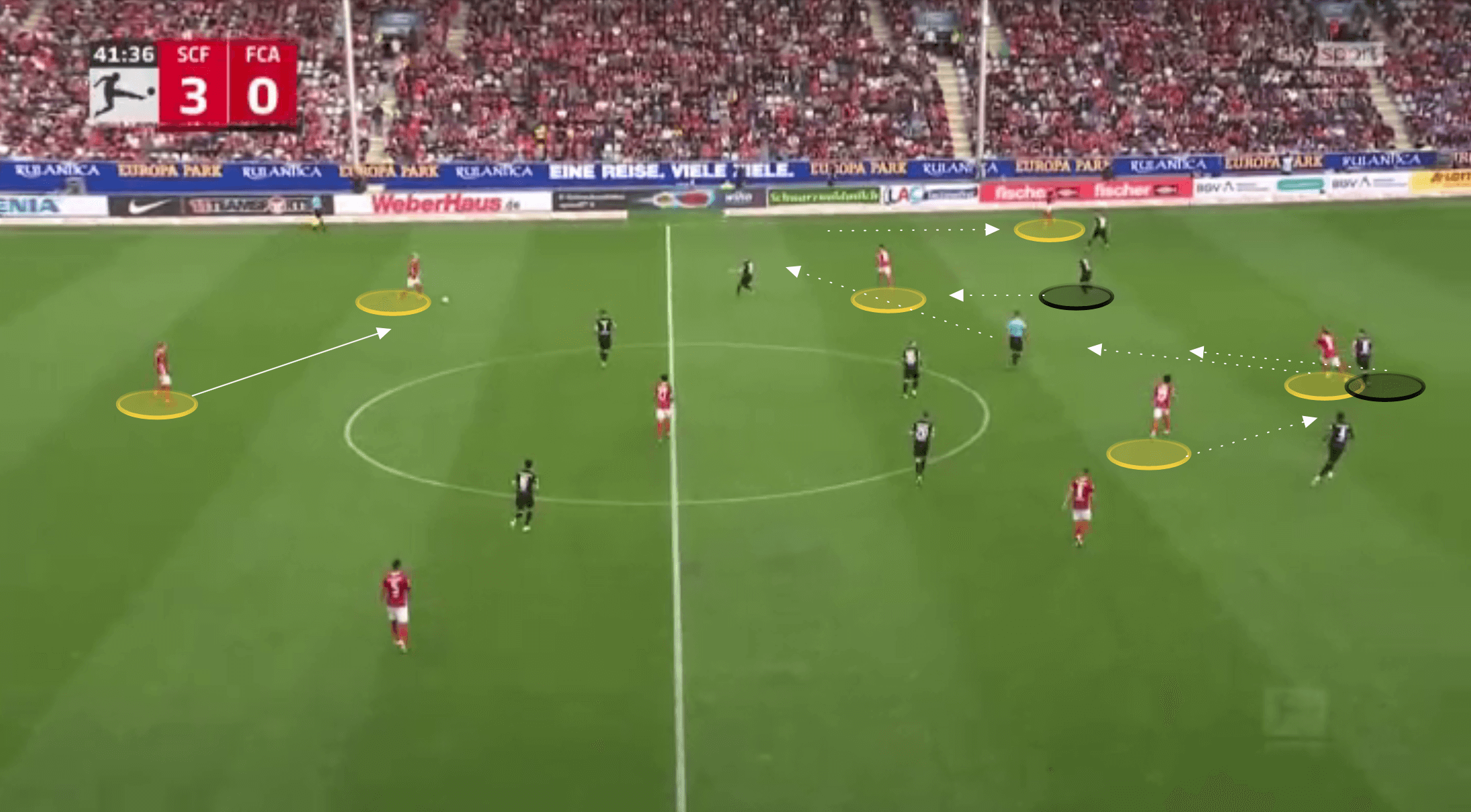

The following image will show how every player ahead of the ball is stretching the opposition defensive shape by taking a different horizontal line to each other where, theoretically, every player is a pass option. However, vertically, players will react to a player dropping deep from a high starting position by pushing high themselves. We can see this in the next image, where the two central attackers are focused on dropping deep and drawing their markers with them. Günter, on the far side, responds by pushing high down the left flank.

With both centre-backs moving forward slightly and Augsburg’s right-back dropping deep, we can see how splintered the opposition backline is in this example. On the near-side, Woo-Yeong Jeong responds to the movement of his inside attacking teammates by pushing directly into the space behind, looking for the long ball over the top.

Pressing detail

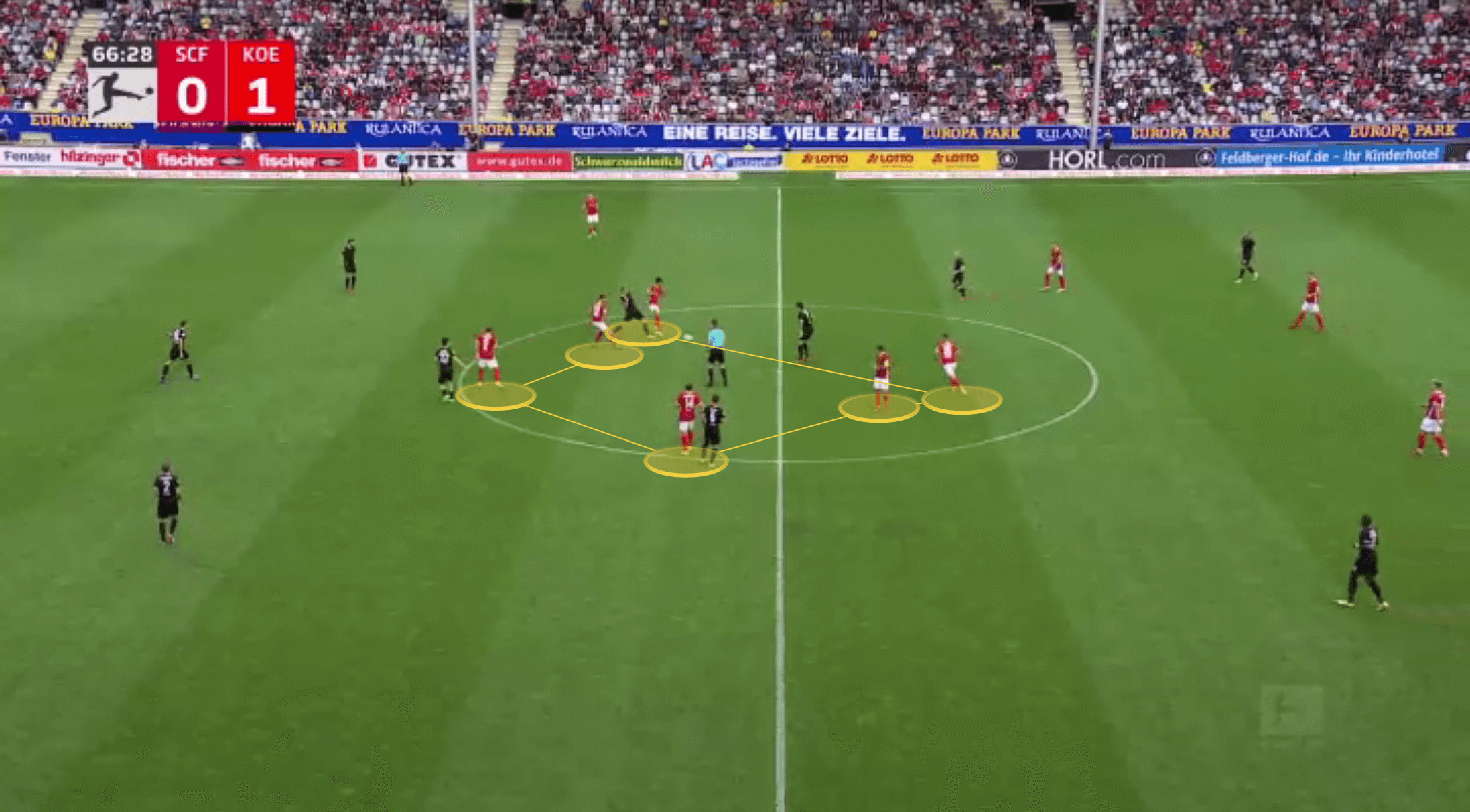

Jumping from in possession to out of possession, we should look at the intelligence with which Freiburg press. Freiburg’s 10.45 PPDA is moderate, minimally below the league average. Yet they structure themselves in a way where they keep their front three and still operate with a midfield two, allowing them to stretch their back five across the width of the pitch. The front three stay incredibly narrow.

This shape can change as the ball is advanced with either wide forward dropping to support the midfield two if they are bypassed, and the wing-backs stepping forward to press the wide areas. If a diagonal long ball is played, like in the next image, the rest of the backline swing across, as you’d expect from this formation.

Freiburg’s front three do a phenomenal job of not only pressing the opposition backline, and covering a significant amount of space in the defensive phase, but also in covering the opposition pivot. With Streich operating with just two midfielders, the obvious issue here is the midfield overload that occurs with teams playing a midfield three. The front three initially cover this pivot with their deeper starting position. They wait for a pressing trigger, such as a bad touch or a backwards pass, and they will step forward accordingly. As this occurs the pressing wide forward will curve their run, showing the ball-player inside and keeping the pivot in their cover shadow.

If the ball is played centrally, then Höler steps out and presses, again keeping the pivot in his cover shadow, with the previously pressing wide forward now dropping back inside to provide balance and pick up the pivot. The midfield duo behind this front three are concerned about man-marking the further forward midfielders, rather than picking up the pivot, knowing their front three can cover this player effectively.

If the ball is continually worked backwards, Freiburg’s front three will react by still pushing forward, being aggressive and looking to win the ball high. Again, wide forwards will curve their press accordingly, even if they can’t show inside, to stop the pivot from being able to receive, whilst the wing-back on that side pushes forward to prevent the opposition from being able to play out.

In deeper areas, the Freiburg front three will get much closer to their midfield duo, keeping a compact central shape and preventing the opposition from being able to play out. Nevertheless, they can still be aggressive at pushing out at this moment. In this example, they recognise a slightly undercooked backwards pass from the Hertha defence as a chance to step out, gain ground, and put the opponent under pressure.

They are still able to effectively cover the opposition pivot. Even as Woo-Yeong leads the press, stepping out centrally with Grifo supporting him to his left, Hertha are unable to break them centrally. As the ball is played out wide, Grifo pushes wide to provide pressure and Woo-Yeong simply rotates inside to pick up the pivot.

Compactness on transition

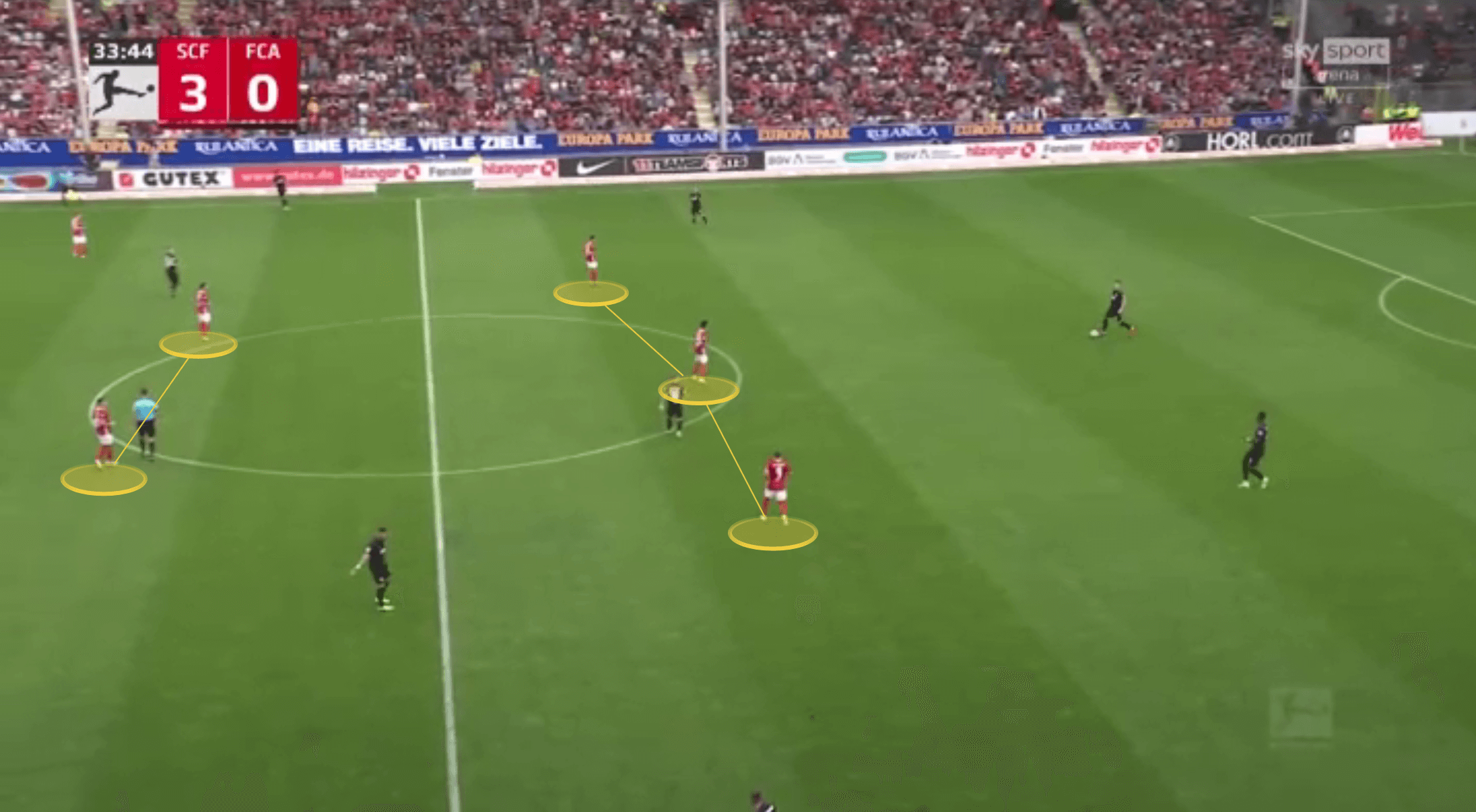

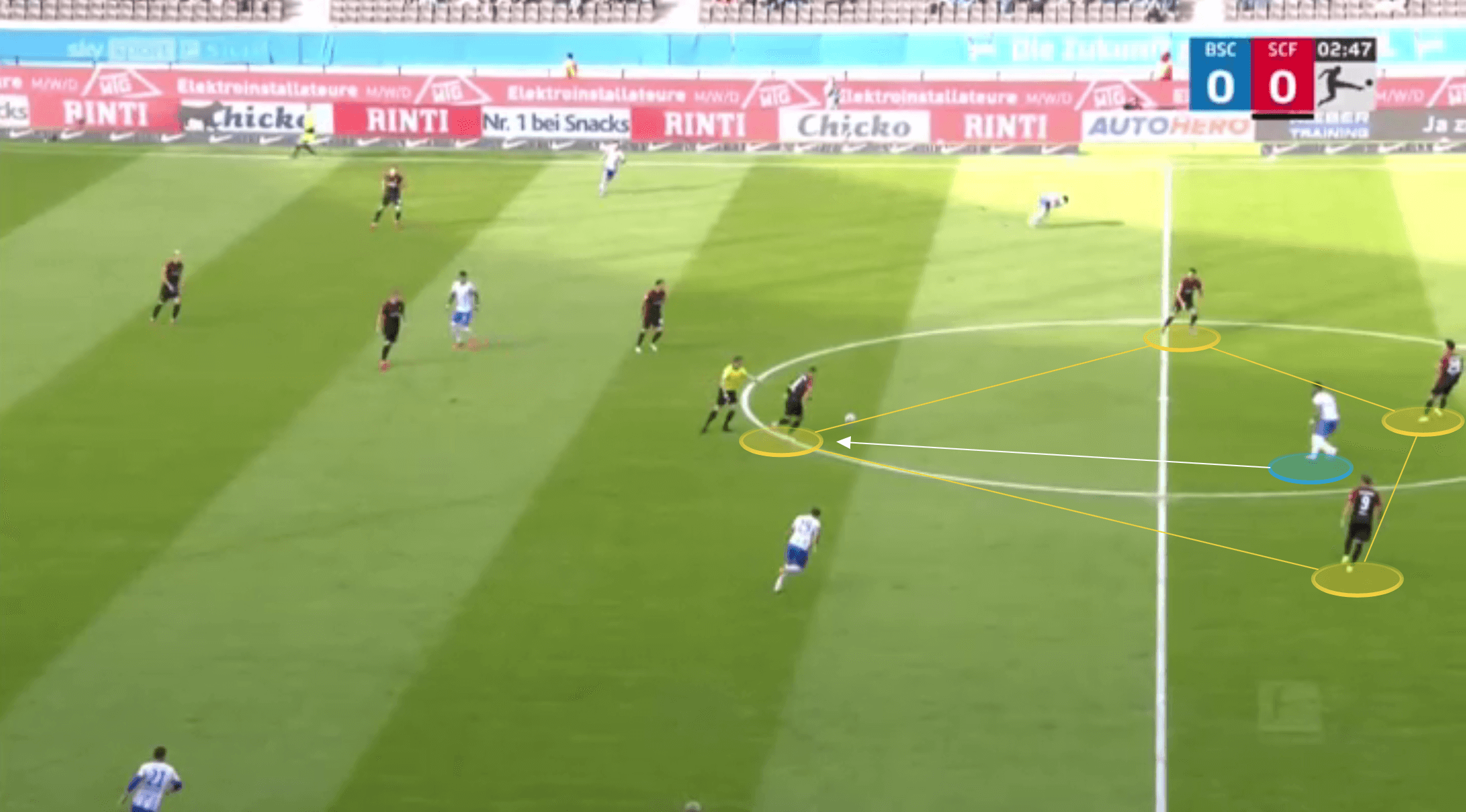

One of the key facets of Freiburg’s possession play is that there is regularly compactness around the ball. Firstly, as we’ve seen, the back three have a central-midfielder placed in front of them giving them a compact diamond. Further ahead, ignoring the width provided by the wing-backs, there is an attacking group of four players operating in close proximity to one another.

Whilst these compact groups allow Freiburg to use combination play that suits their vertical, aggressive passing football, it also structures their counter-pressing. It allows them to be highly successful in defensive transition, with the players in these tight groups nearly always immediately outnumbering the player on the ball for the opposition. This gives Freiburg the freedom to be slightly more aggressive with some of their forward passes, knowing they can quickly regain possession if a forward pass is slightly wayward and intercepted as a result.

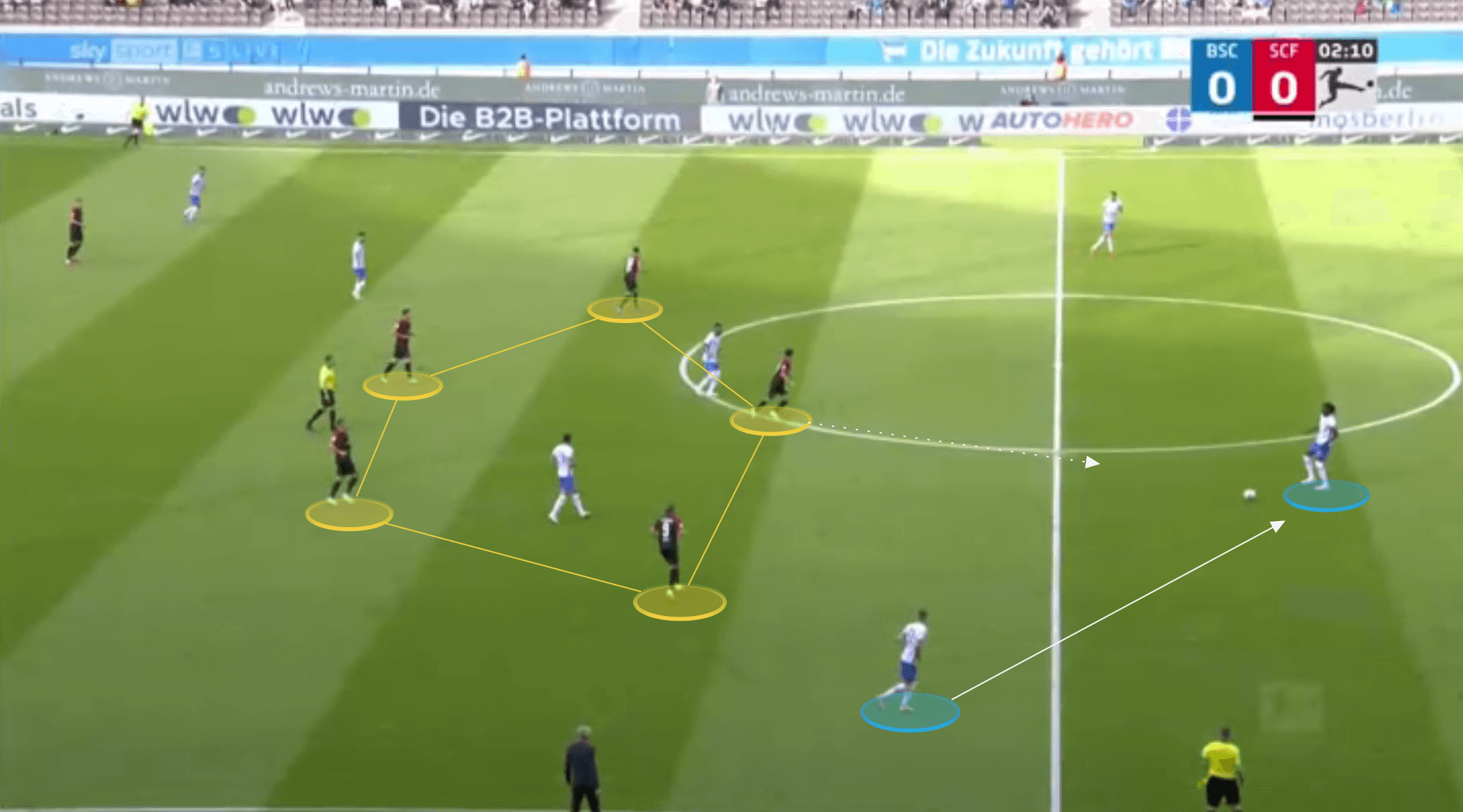

An example of this can be seen in the following image, as Freiburg initially turn over possession in the centre of midfield and in an instant have six players surrounding the ball. The opposition are clearly ready for this, with four players of their own in this space, but nevertheless, they still face a numerical overload.

Even in the defensive phase, Freiburg’s compact defensive shape, which was shown earlier on in this analysis, structures quick transition play, albeit on attacking transition this time. Freiburg are able to quickly release the ball when an interception is made and use the players surrounding the ball to structure a swift counter-attack, breaking through the centre of the pitch where possible.

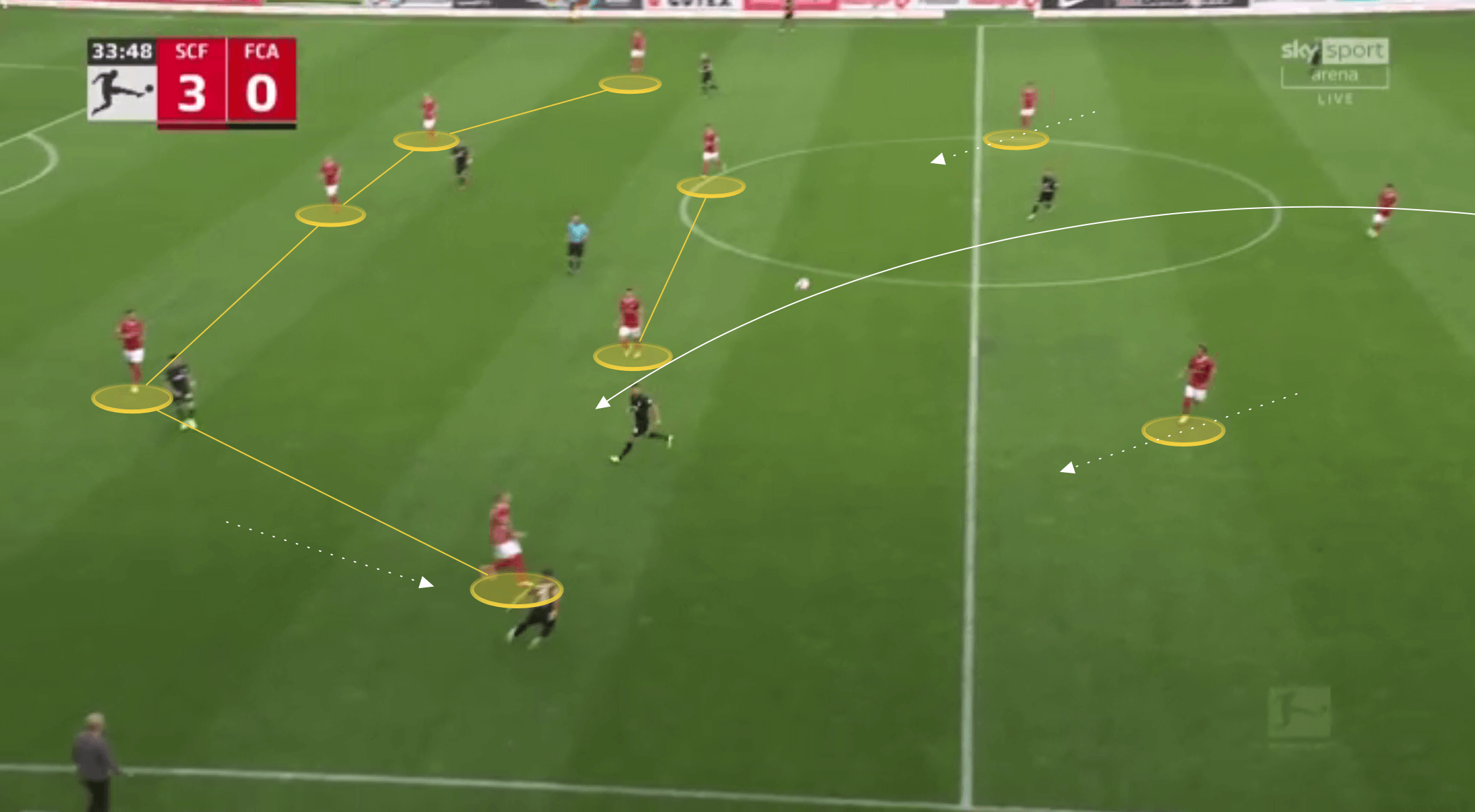

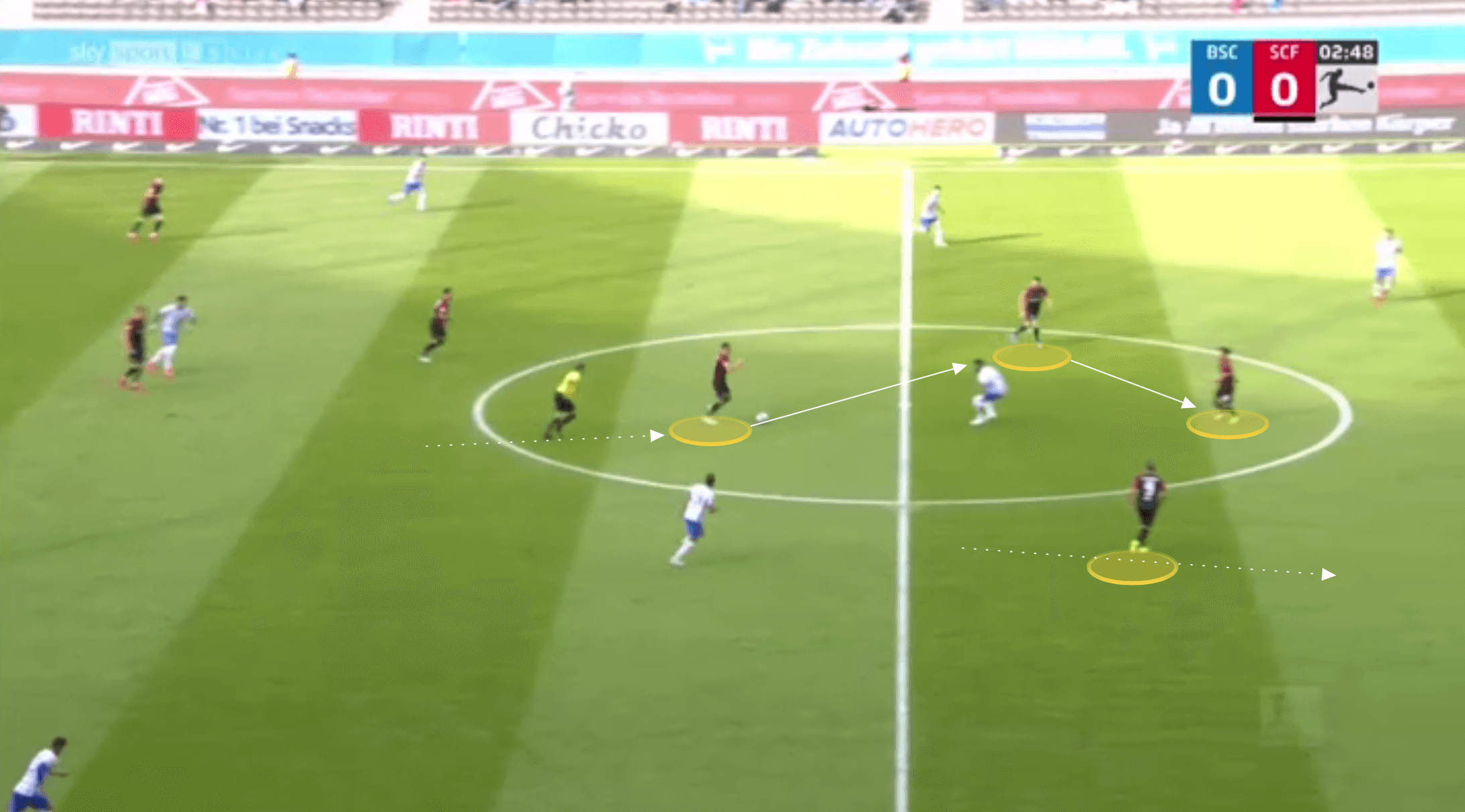

The next two images show this in action, where a Freiburg midfielder makes an interception and immediately there are four Freiburg players around the Hertha player who just gave up possession.

A quick interchange between three of the players a second later, and Freiburg are already driving through the centre of the pitch with runners supporting this move as well.

Conclusion

Christian Streich continues to have his Freiburg side play outstanding football, showing some excellent tactical innovation and clever attacking play, with highly disciplined pressing in the defensive phase. It has been highly effective, with them not only being the only team in the Bundesliga to be undefeated, but they are also part of an elite group of just four teams in Europe’s top five leagues to still be undefeated in the league at this stage this season. The other teams are Napoli, AC Milan, and Liverpool. Not bad company. It remains to be seen whether Freiburg can keep up the pace they have set. However, they have a settled squad, many of whom have worked with Streich for a number of years, and a manager who continues to get better every season.

Comments