At the end of the 2019/20 season, Carlos Corberán was celebrating promotion to the Premier League after winning the Championship title as assistant manager to Marcelo Bielsa at Leeds United. The Spaniard had been at Leeds for three years prior, where before this he had been a head coach in Cyprus, and following a Championship win in Yorkshire, Corberán was offered the opportunity to stay in the division and the county, with Huddersfield Town offering him the role of head coach following their disappointing season.

The 37-year-old has made a quiet and somewhat inconsistent start to life at Huddersfield, with the side in 14th place at the time of writing this piece. This inconsistency though is to be somewhat expected, especially when a new manager looks to implement such a clear playing philosophy and identity like Corberán has, and in this tactical analysis, we will focus on this style of play and how it has been implemented so far at Huddersfield.

Fluid build-up

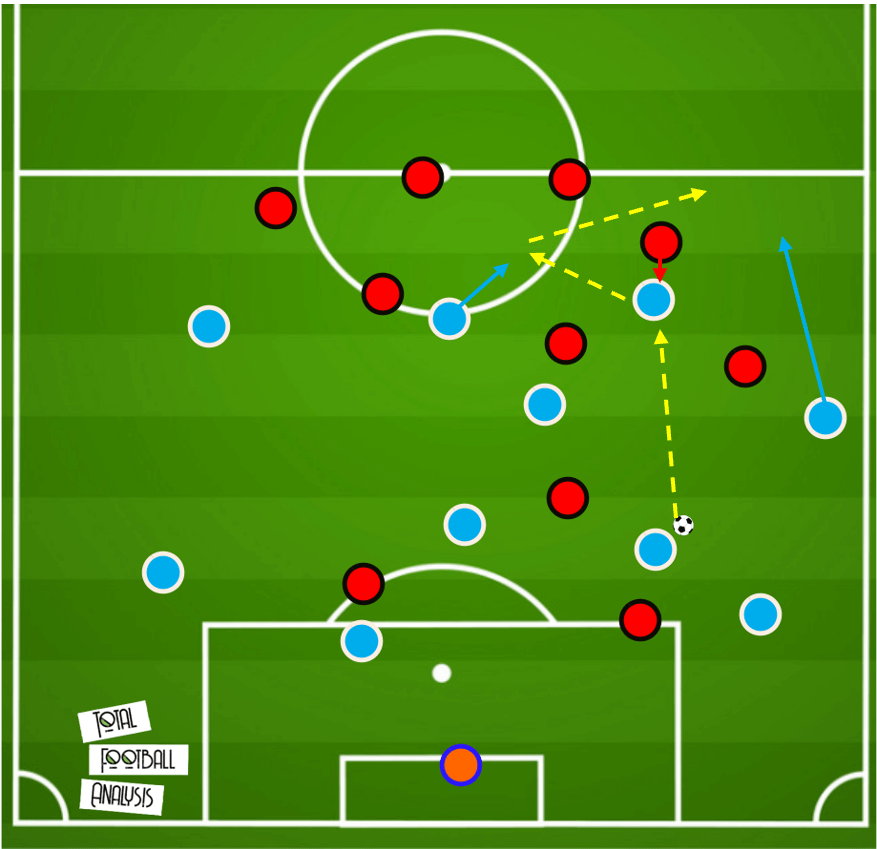

Huddersfield’s in possession philosophy is built upon fluid, dynamic movements by players in order to exploit and use space effectively. Their most common formation this season has been the 4-3-3, but this system often drops into a 3-4-3 with Jonathan Hogg dropping into the back line. Within these two shapes, multiple variations can and do occur, with players occupying different spaces situationally.

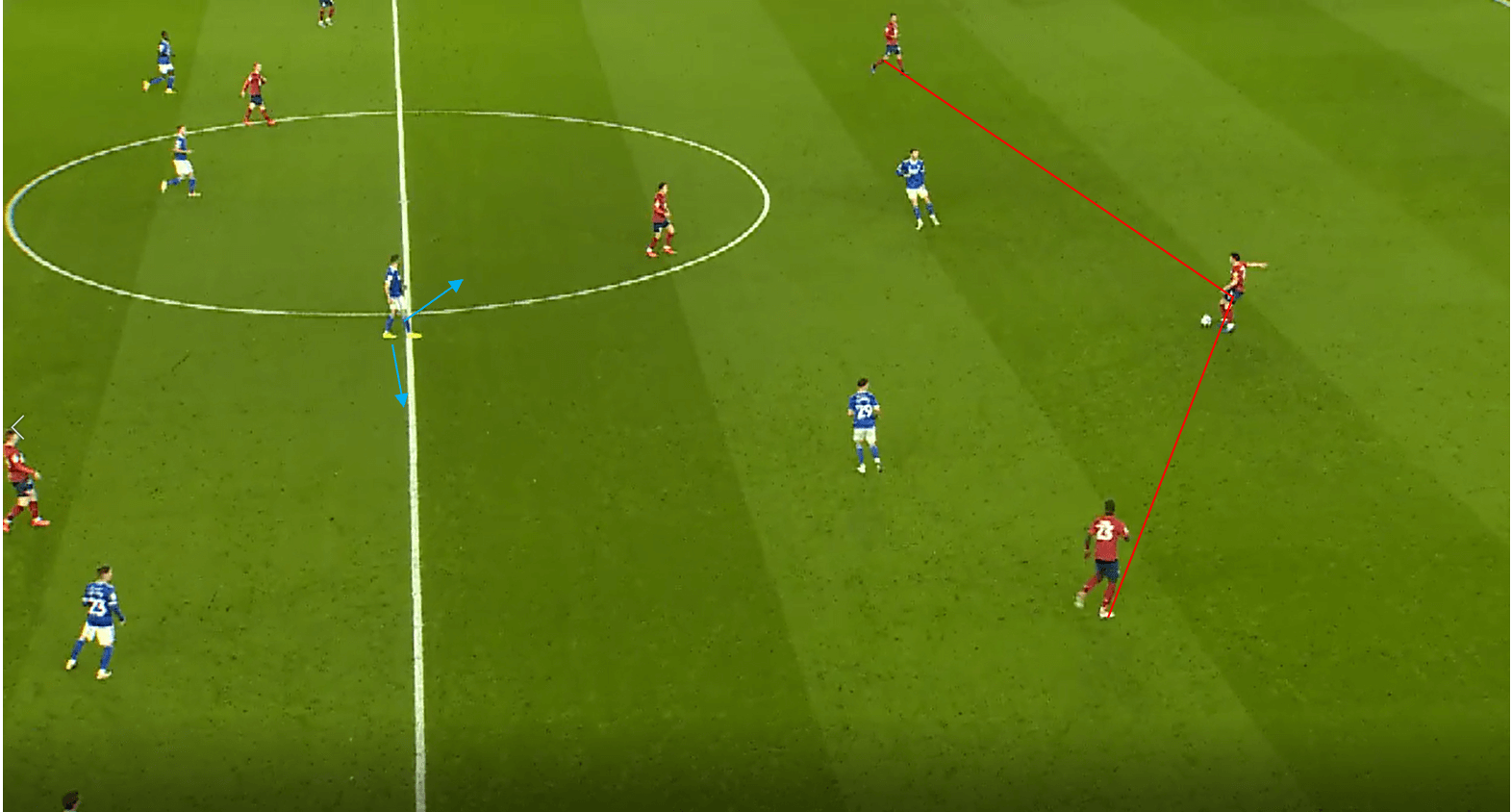

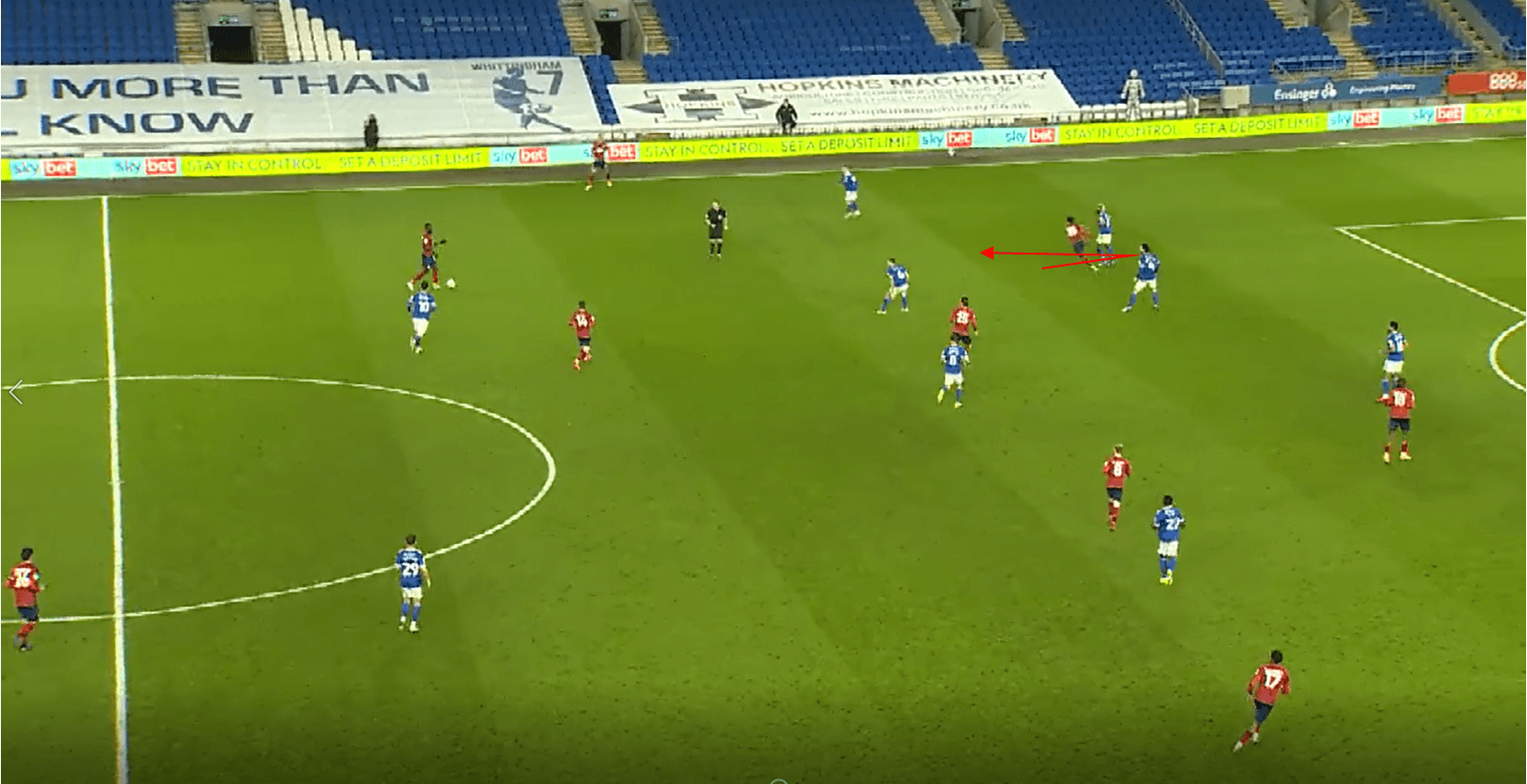

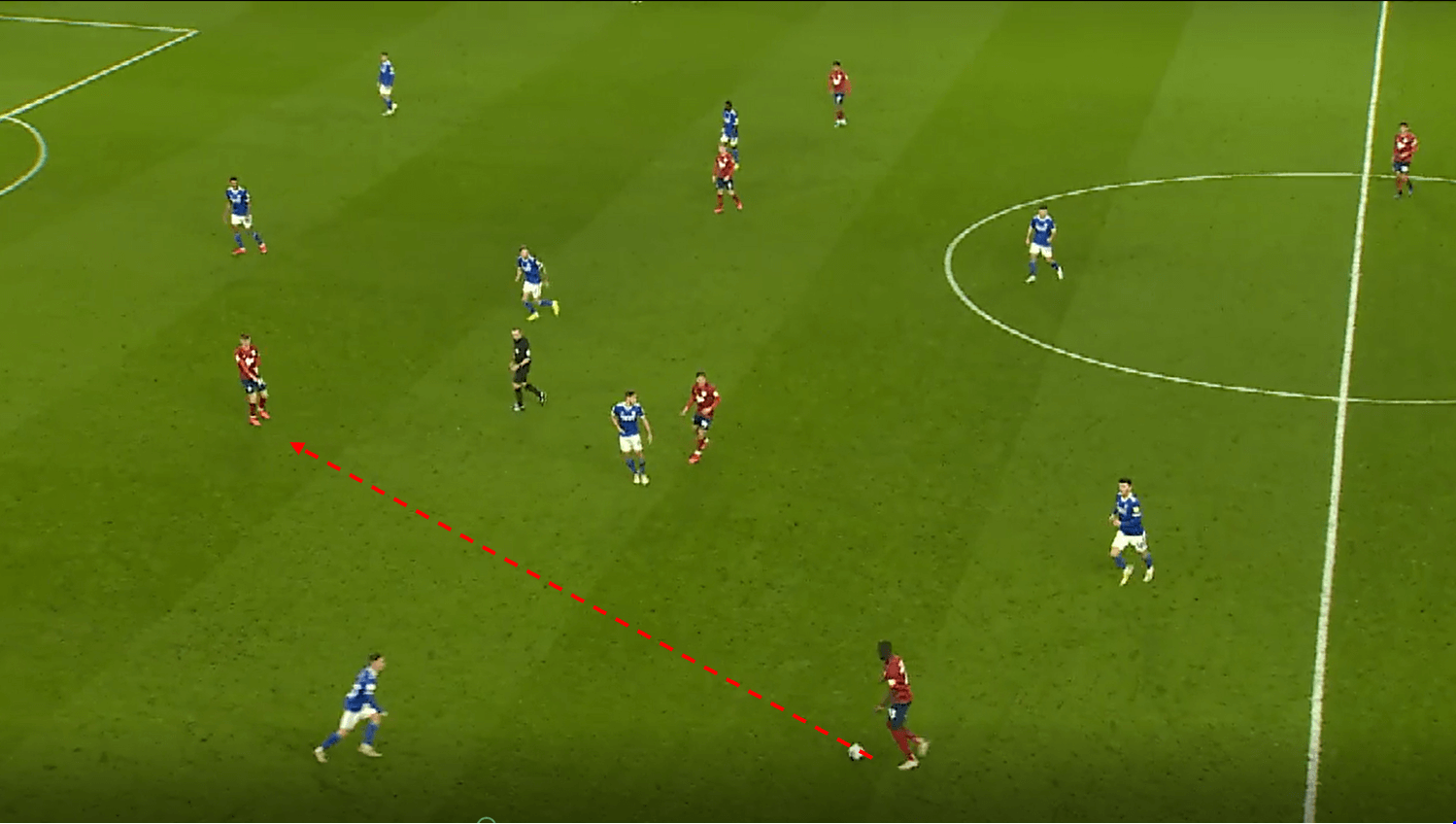

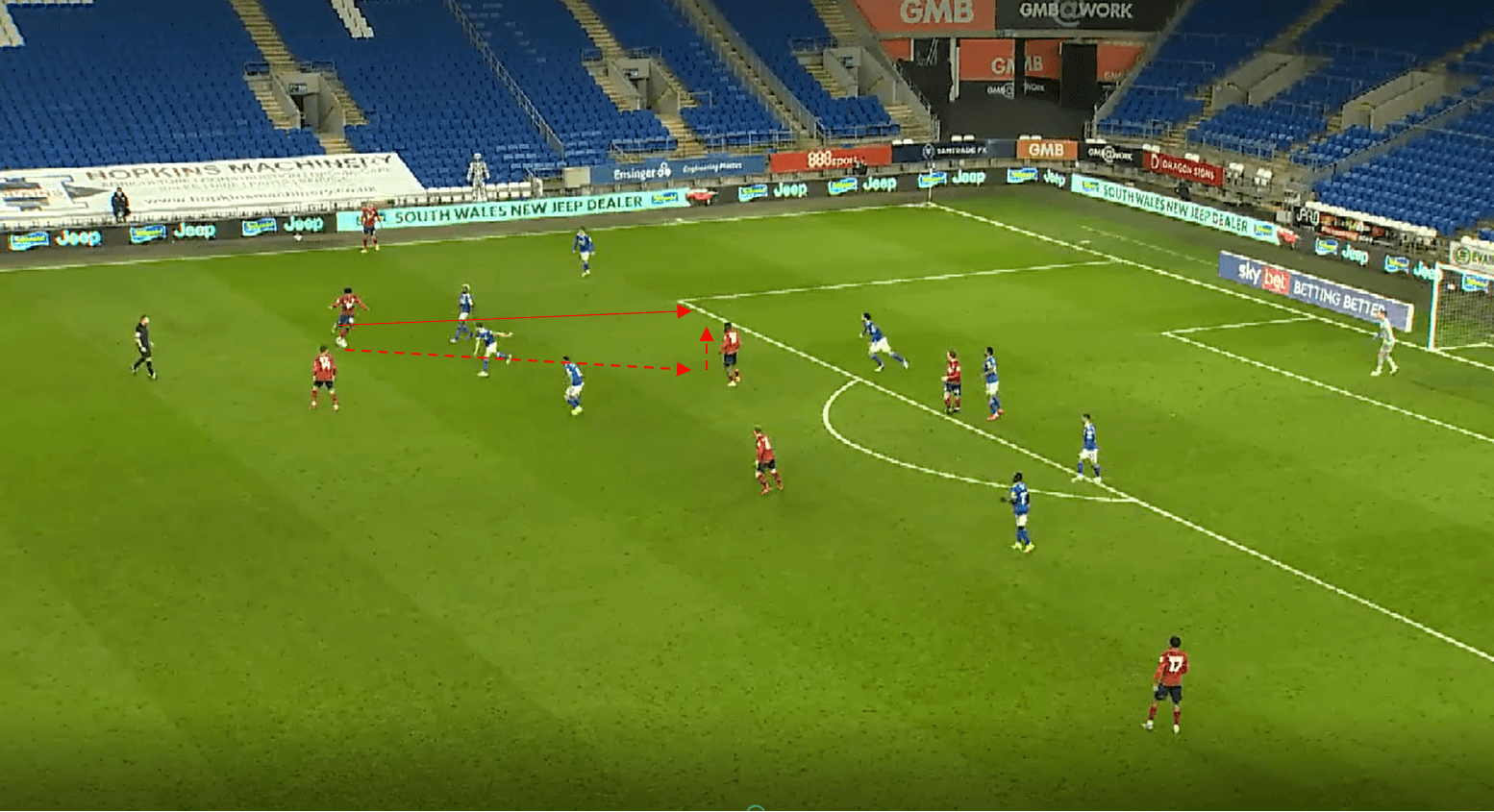

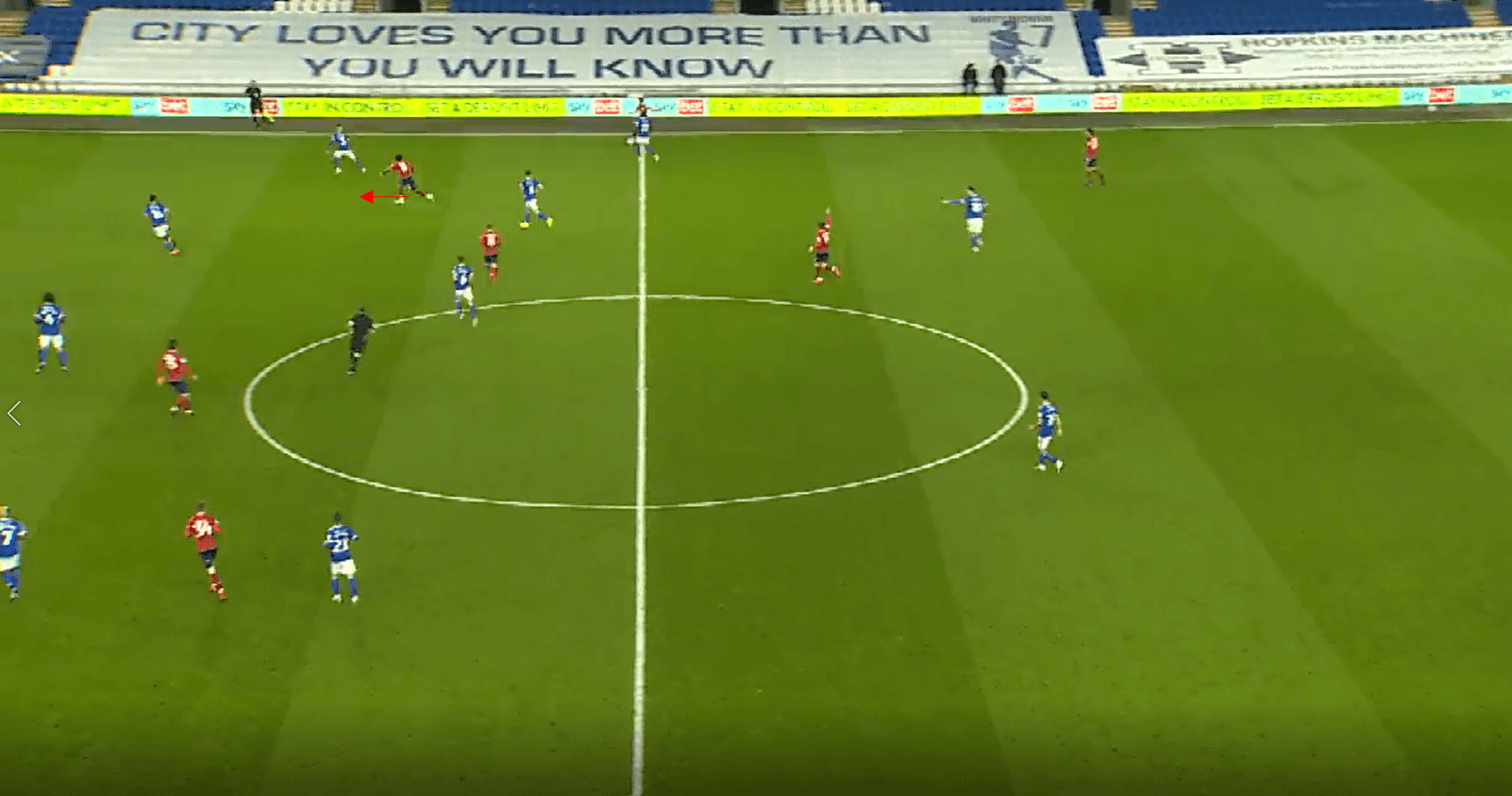

When dropping into a back three, they will often look to maintain a single pivot in an attempt to create overloads in midfield. We can see an example below in their match against Cardiff, where Ajax loanee Carel Eiting acts as the single pivot in front of the defence. The back three stretches the first line of Cardiff’s press, which increases access to the central pivot. With Cardiff in a 4-4-2 then, if the pivot can be accessed and can occupy a nearby central midfielder, there is an opportunity to overload this central midfielder. We can see the potential decisional crises for the Cardiff midfielder here, with a forward moving deeper to create the overload. This is a common structure seen within positional play known as Salida Lavolpiana, and used by many teams such as Liverpool, Manchester City and Bayern Munich.

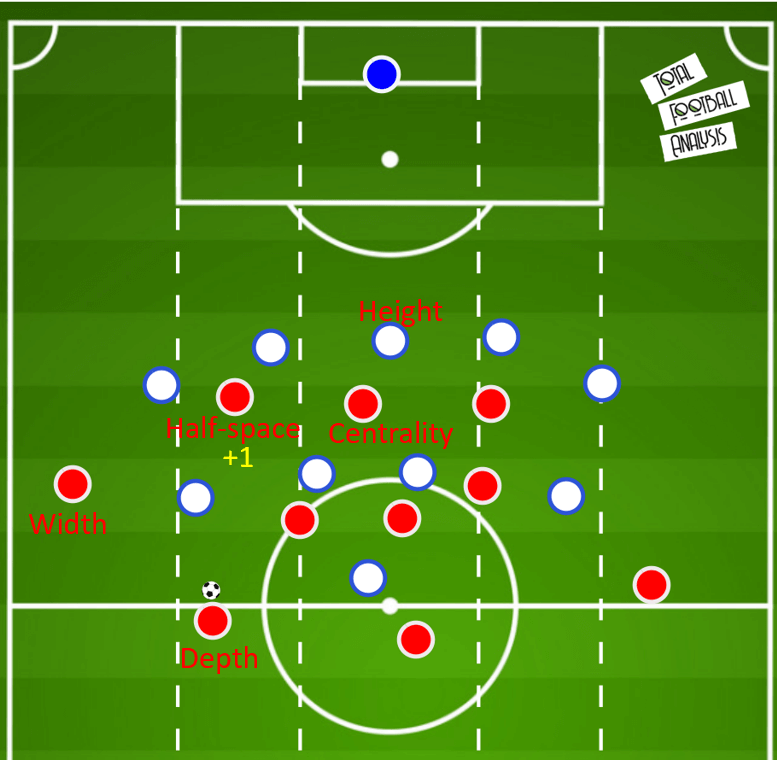

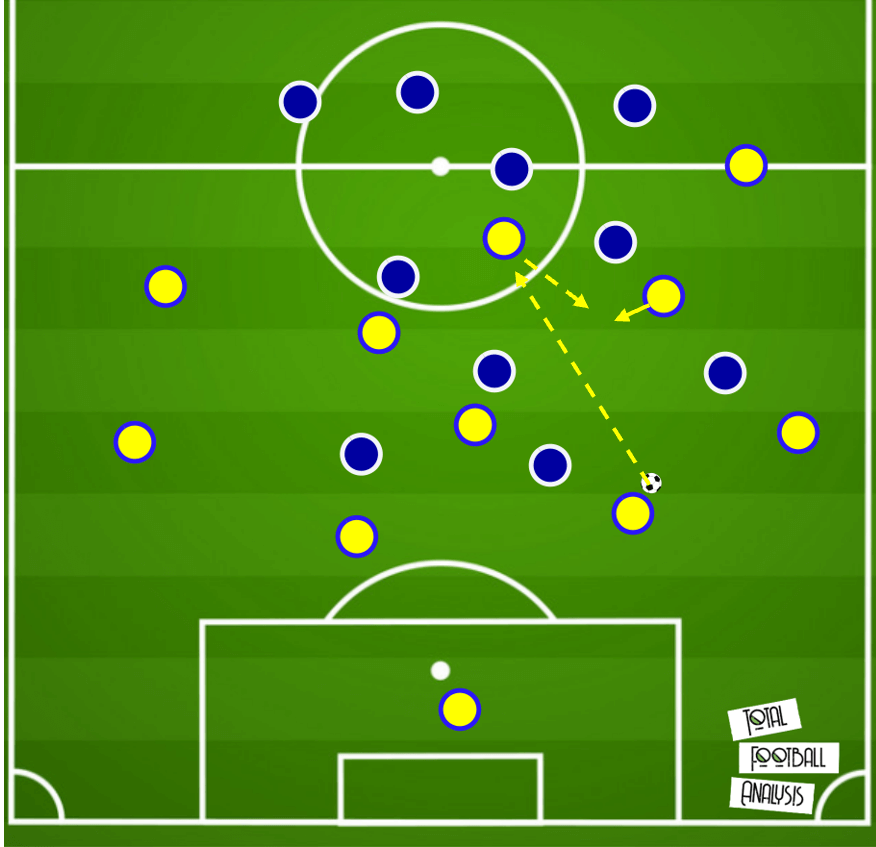

We can see a generic image of their 343 in possession below, with the shape resembling an almost 3-2-5. The wide centre backs occupy the half-space, meaning the wing-backs can push on provide width, with this width helping to open access to the half-space. The inside forwards of Huddersfield occupy the half-space, while the central forward remains central or will drop deeper to create central overloads.

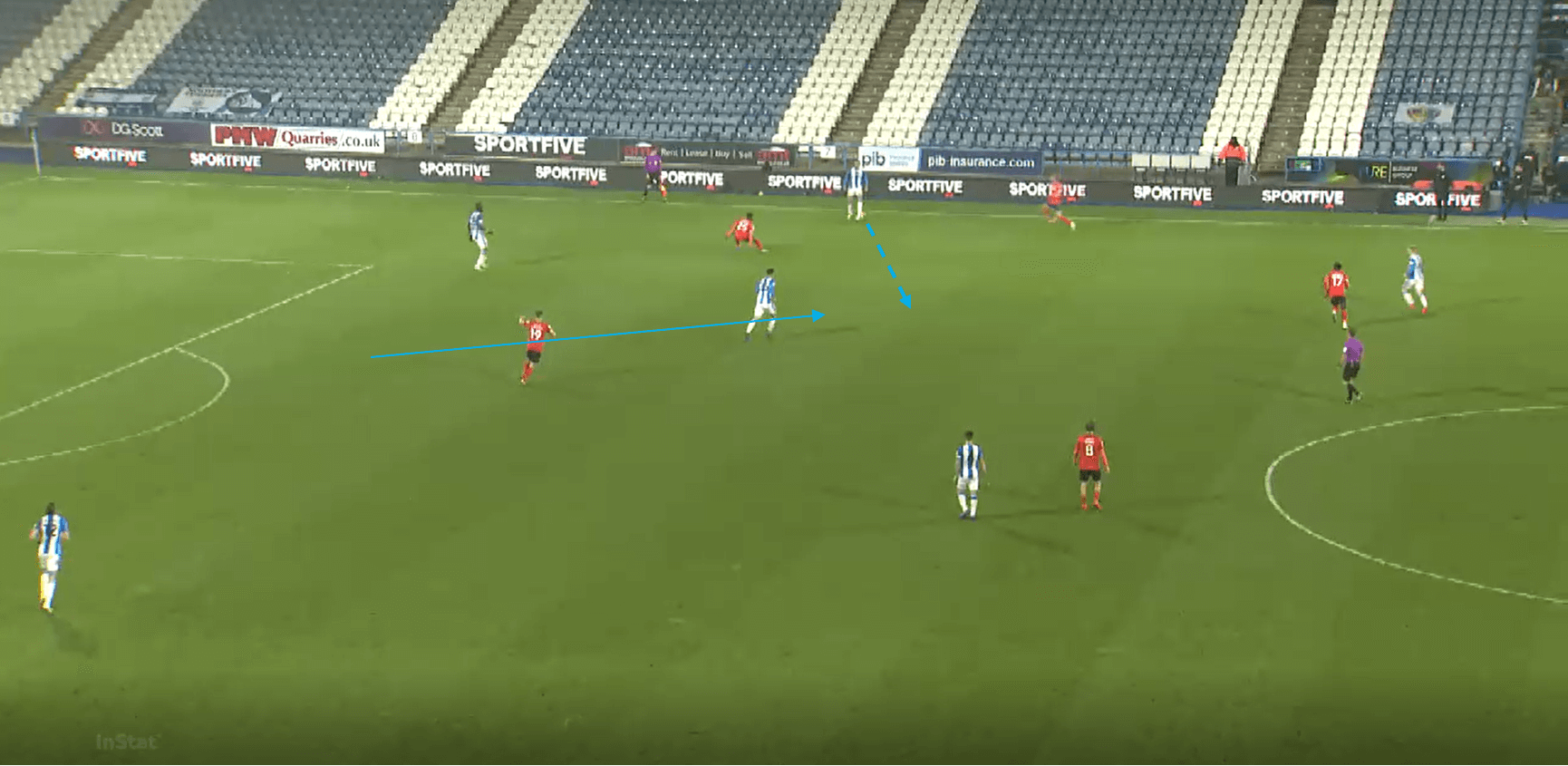

A back four is also used with a single pivot commonly, and we can see an example of this here, with this also giving a glimpse into a key part of Corberán’s philosophy. We see the goalkeeper has possession and so Huddersfield form a back three again technically, with the two centre backs splitting while Hogg stays higher as a pivot. Hogg starts centrally, but makes a movement to the left side of the pitch, which his marker follows.

Hogg’s movement is actually a decoy movement, with Hogg vacating this central space to allow for another midfielder to drop into the space. The use of the goalkeeper within the back three here allows that central passing lane to open for this rotation to be found, and these kinds of midfield rotations to receive the ball are common.

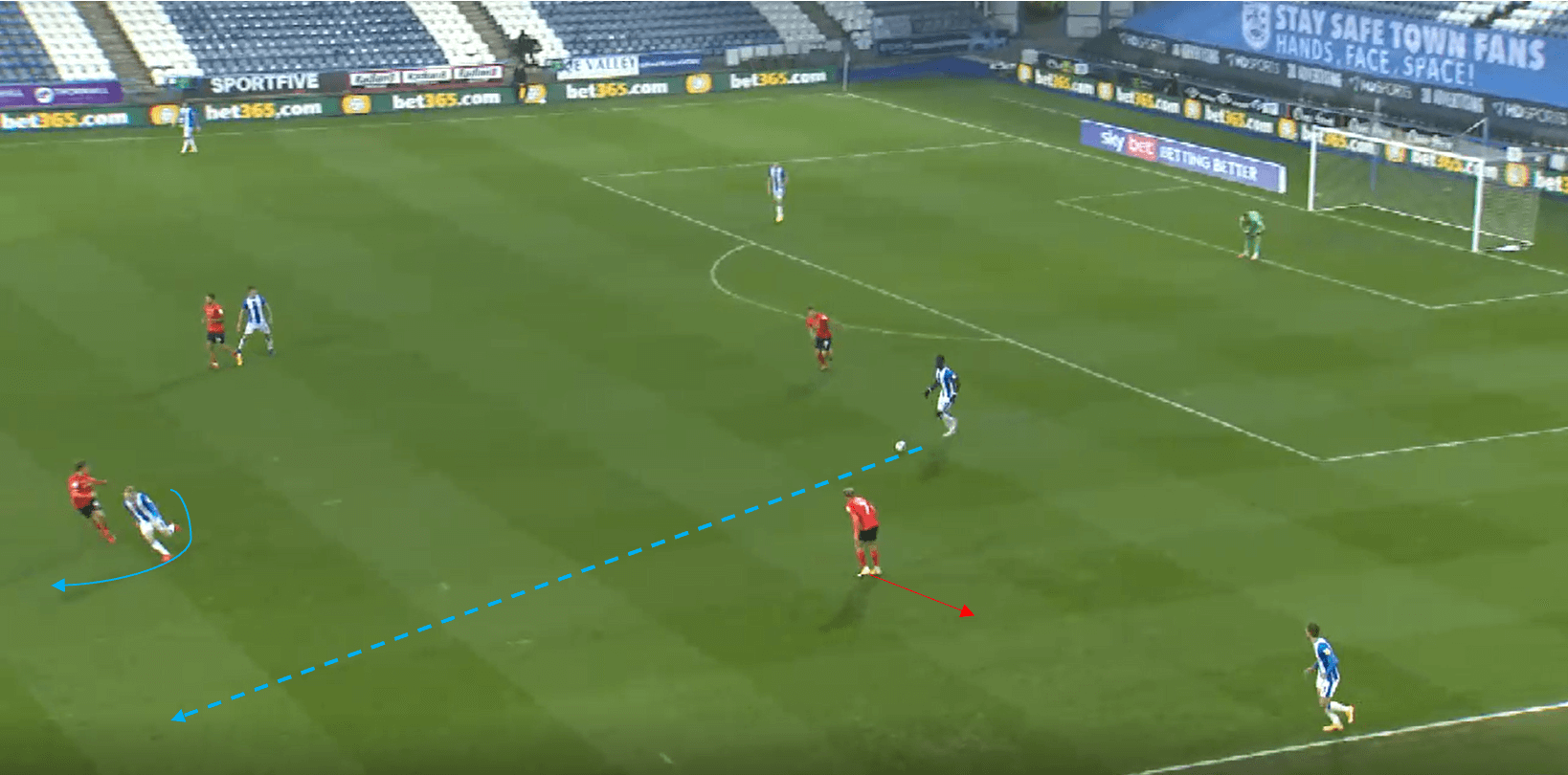

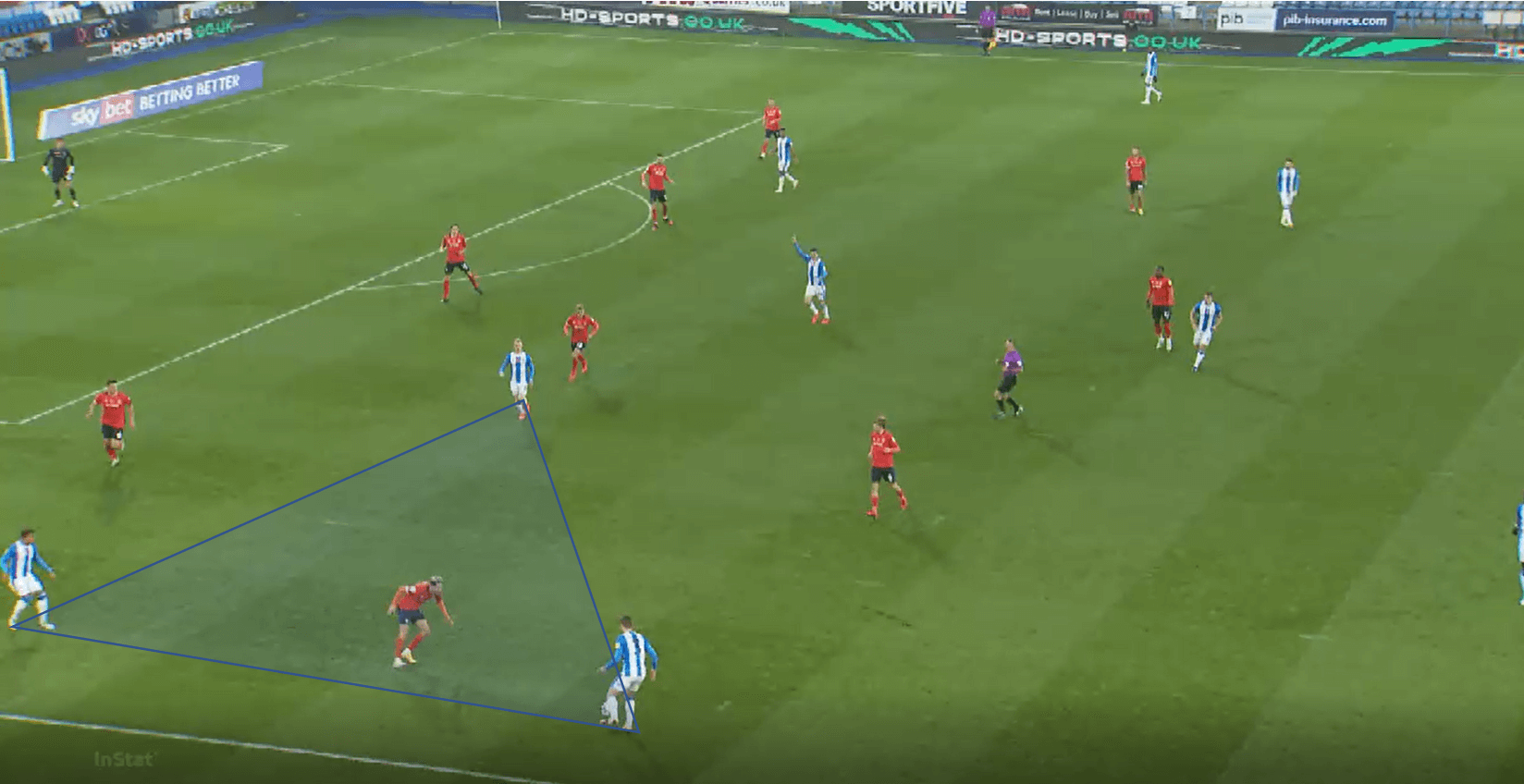

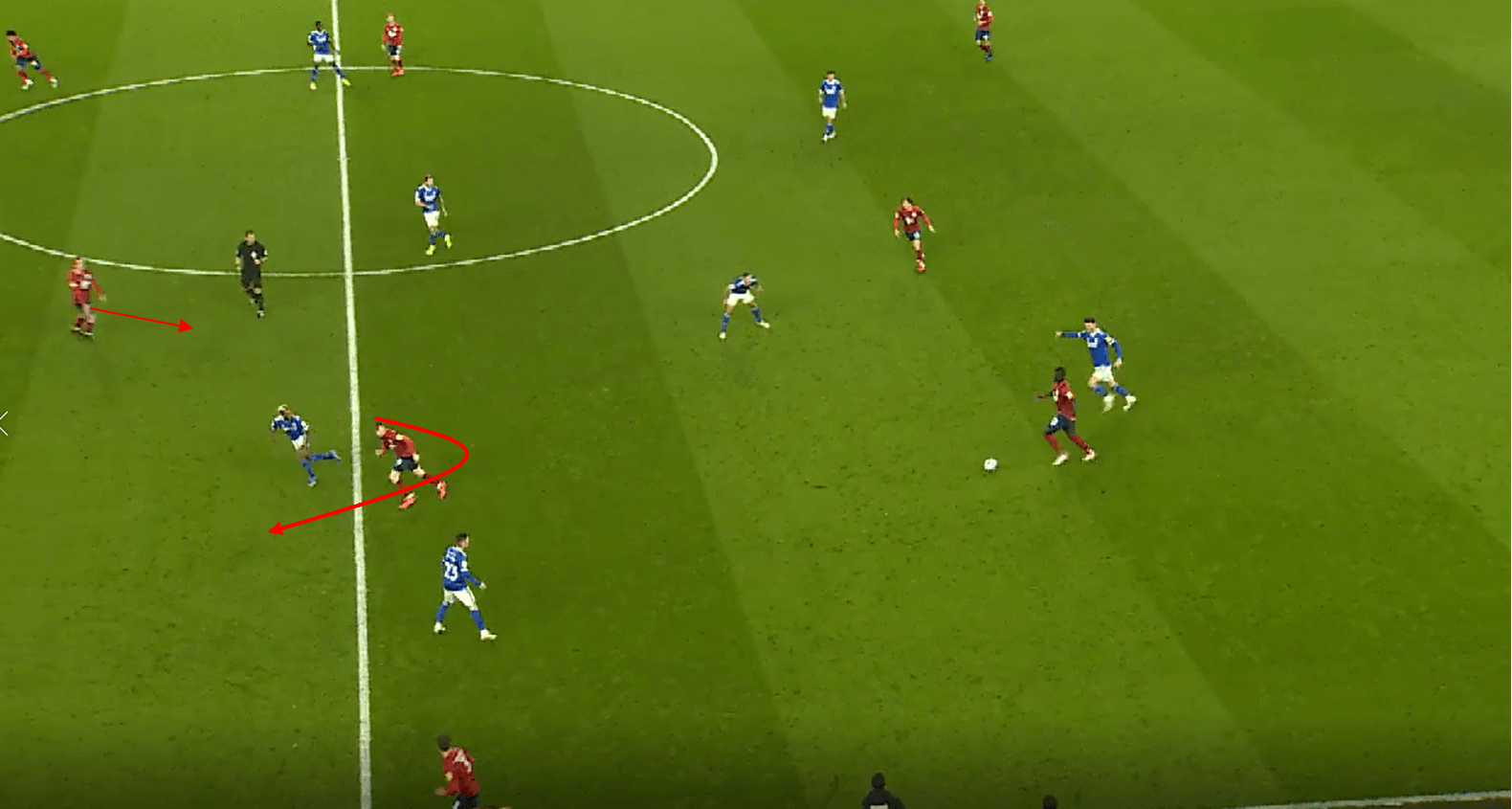

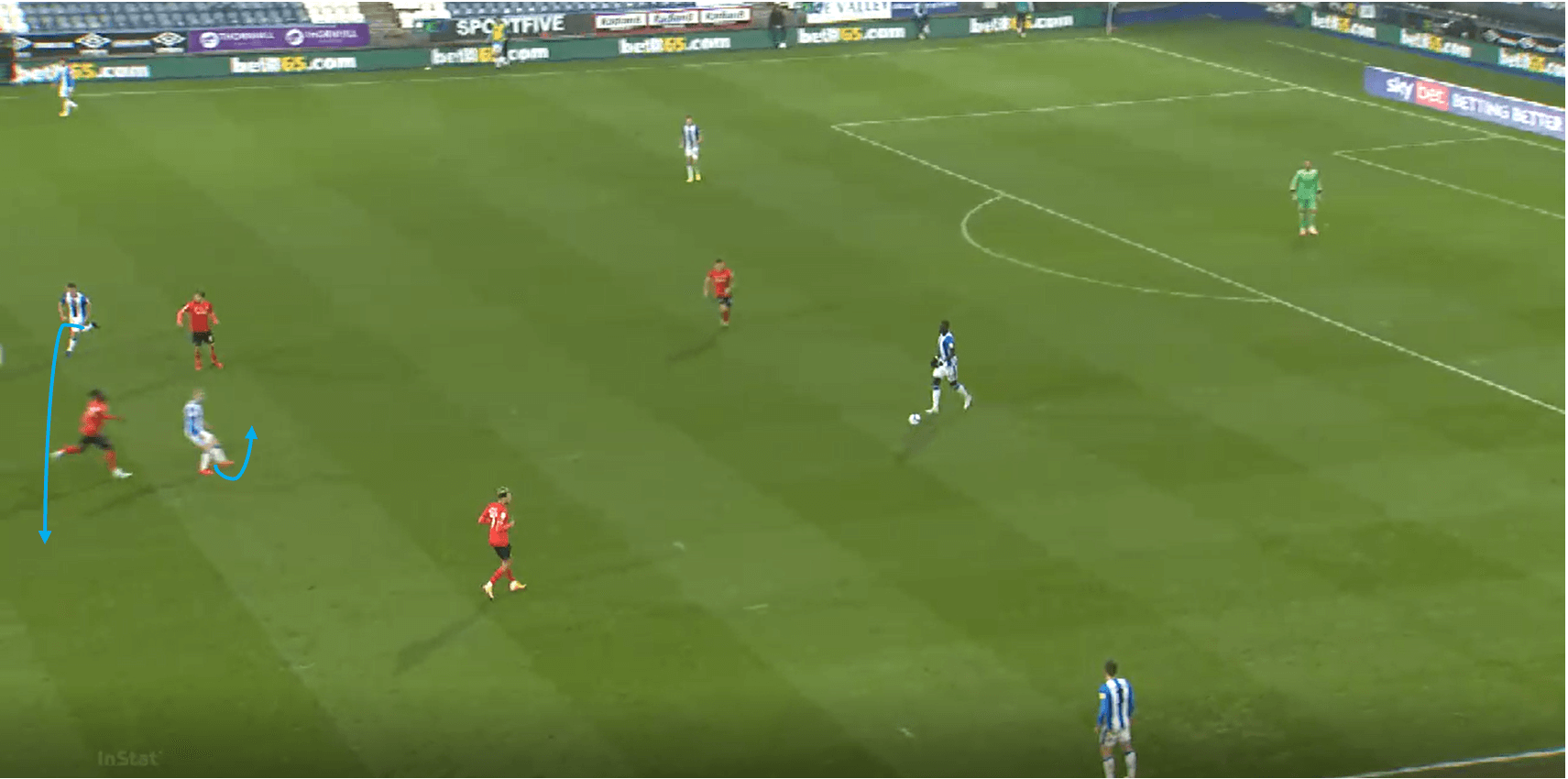

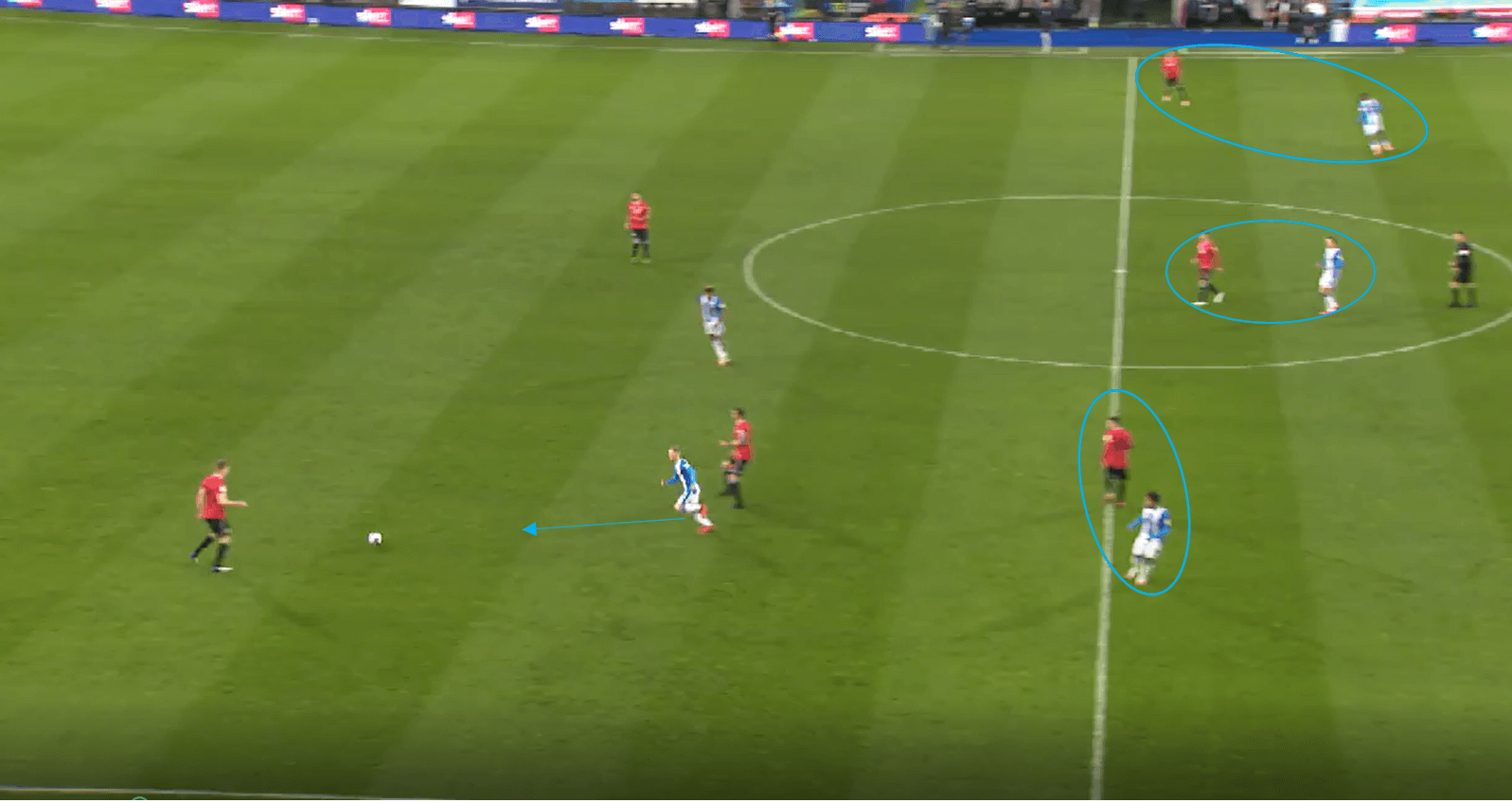

When in a back four against higher pressing systems, these rotations or dismarking movements by the midfielders become an integral part of the build-up, and we can see an example from their game against Luton here. We can see Huddersfield are in their back four here, and one of the wider central midfielders is marked tightly. The Huddersfield full-back remains wide, and so the lane to the winger is left open by Luton. The Huddersfield midfielder looks to dismark his opponent by running in behind and acting as the third man in a third man play.

The ball gets played wide, and the midfielder dismarks his player and looks to exploit behind, but the winger doesn’t play the ball. Nevertheless we see the concept behind the play, with dismarking movements and third man runs helping to create numerical superiority despite players previously being marked.

When nearby passing options are marked, defenders will also push forward from the back line and play a 1-2 with a nearby player, in order to receive the ball in open space ahead of them. In last year’s Christmas TFA magazine, I discussed Tim Walter’s teams and their use of this dynamic space occupation. Later in this analysis I will discuss the advantage gained from this type of play.

Half-space movements

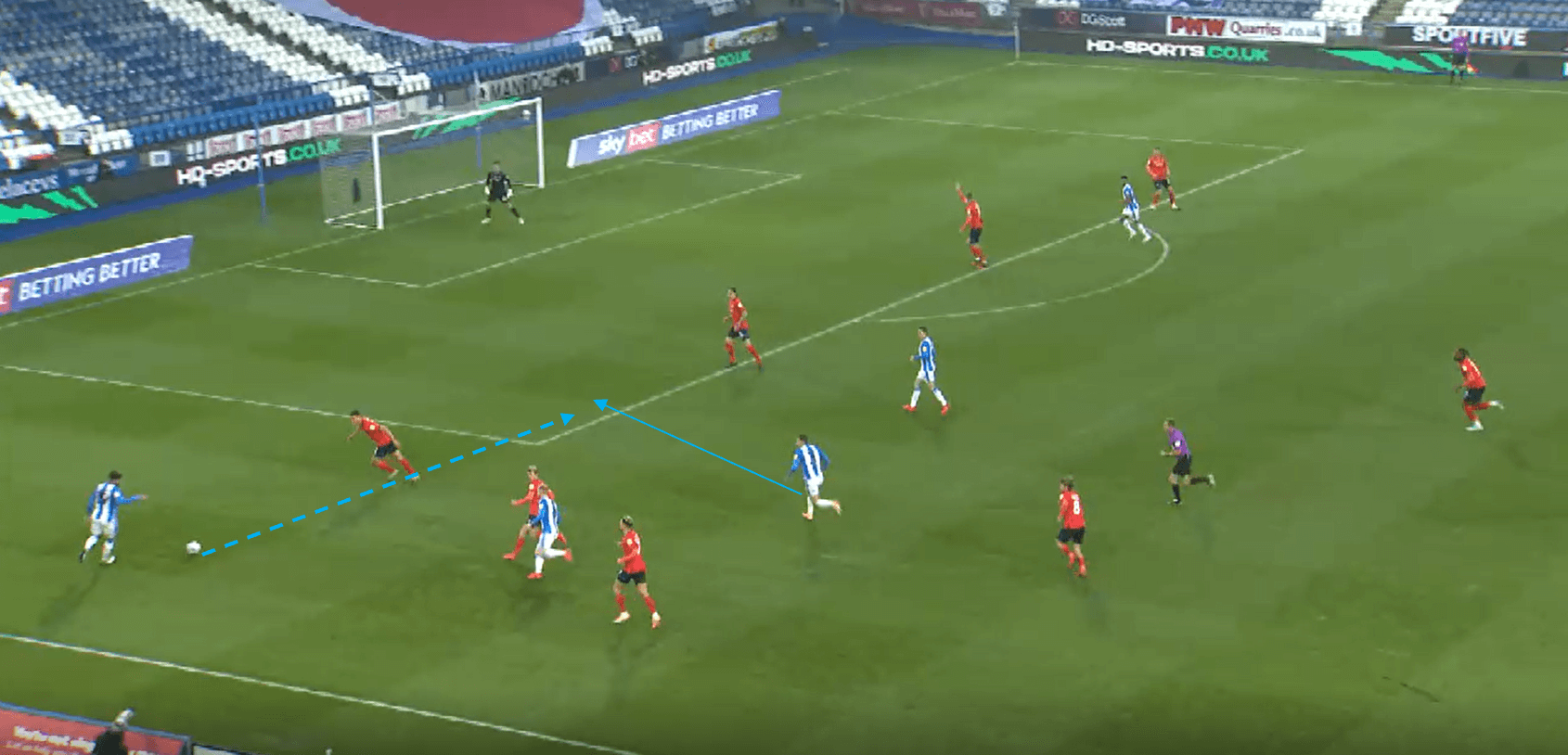

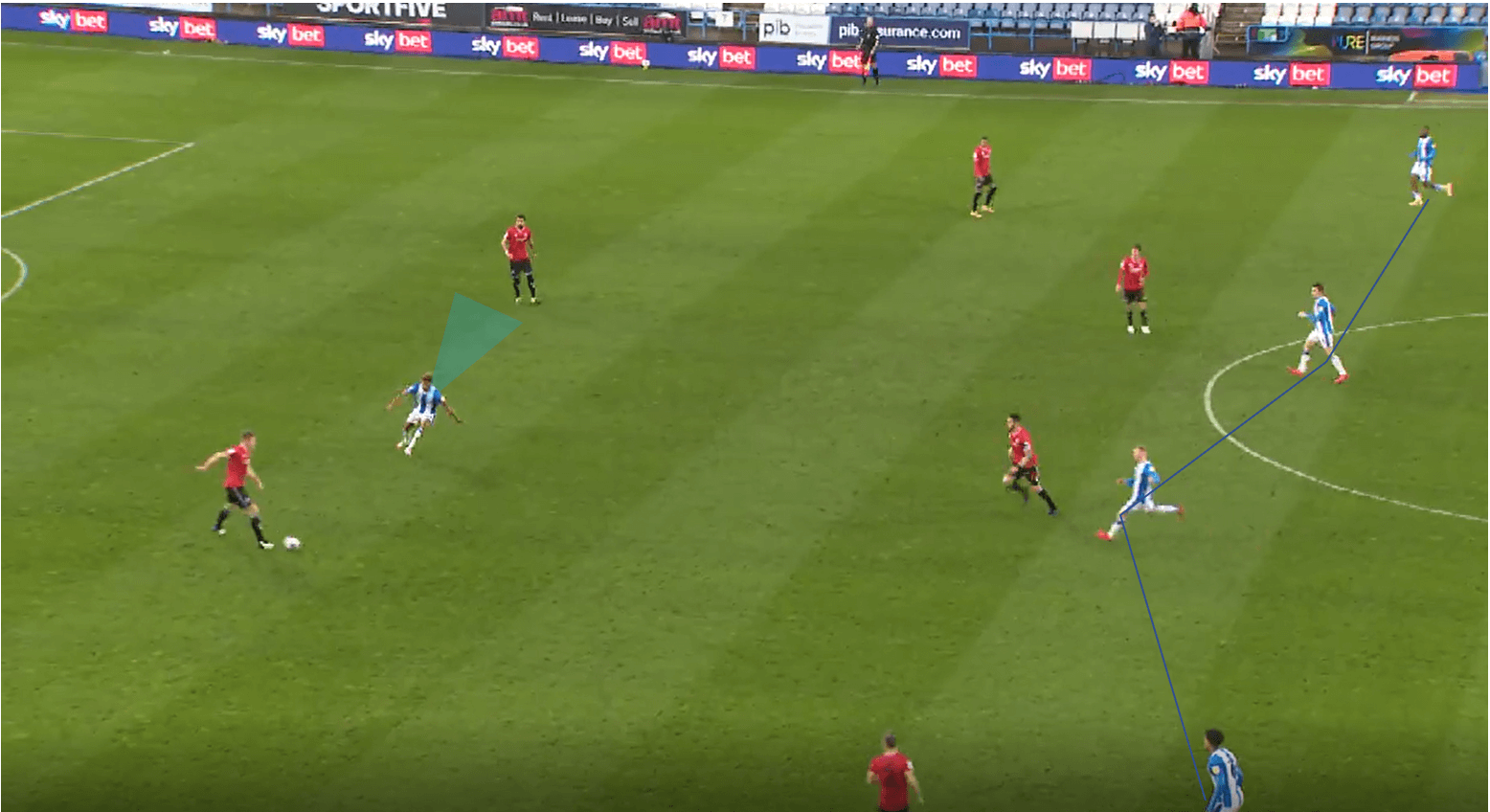

The aim of this fluid build-up is to of course progress the ball, and the most common area of ball progression comes through the half-space, with the opposition naturally protecting the centre. We can see Huddersfield’s structure in a basic example below, with a triangle structure helping to access the half-space. The full-back has possession and provides width to the attack, while the inside forward operates within the half-space. The key aspect of this play is the occupation of the opposition central midfielder, which is done by the nearby central midfielder. This player stays deeper in the half-space and occupies the opposition midfielder and forces him to move forward, and so the passing lane into the half-space opens.

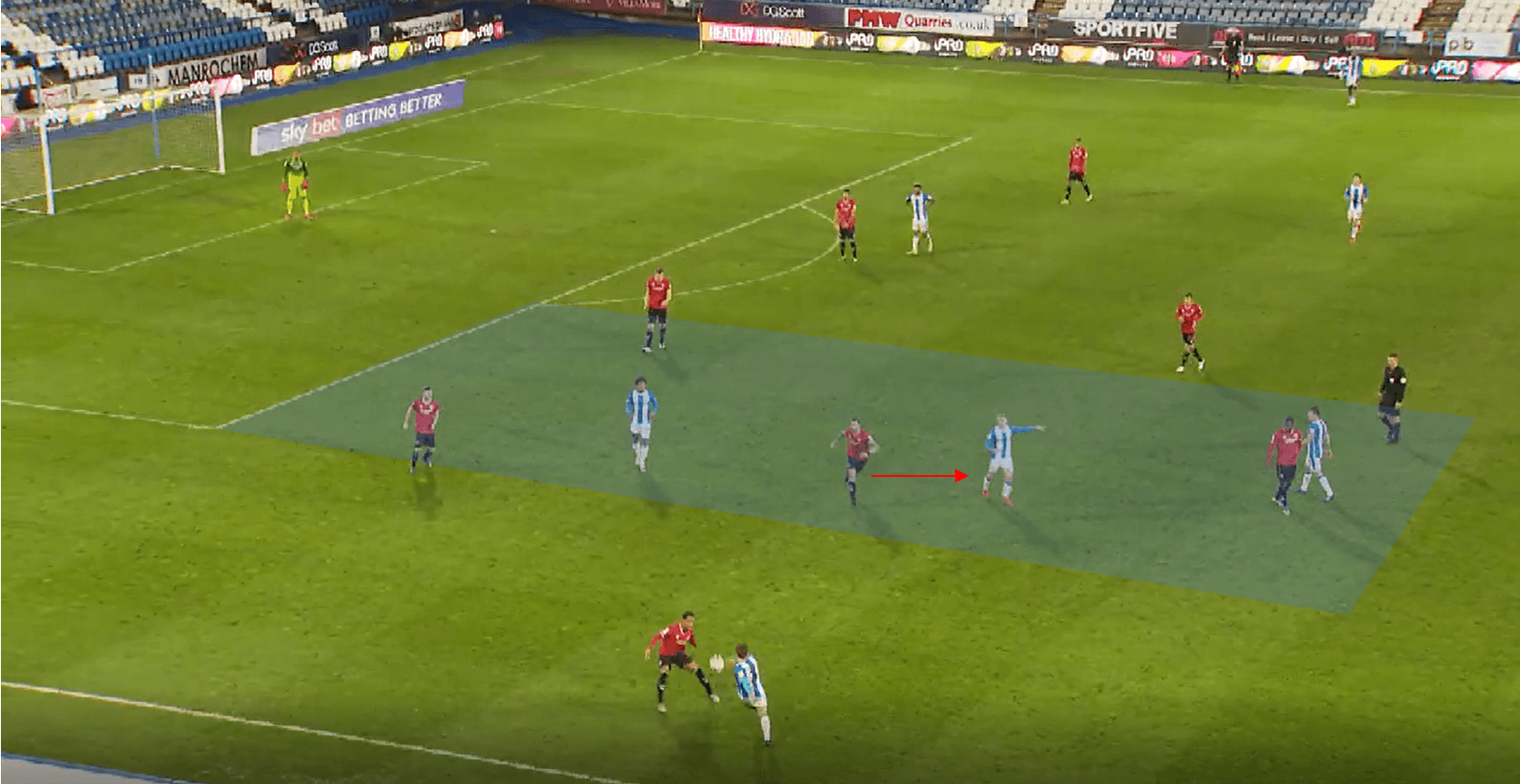

Roles within these triangles and the positional play structure as a whole are interchangeable, and so at times different players will occupy different roles, and some roles don’t need to be occupied. Here for example, we see Huddersfield in a structure they use often, with a central midfielder now occupying the half-space, while the inside forward moves wider to drag the full-back wider, which decreased defensive coverage of the half-space. They don’t need anyone dragging the central midfielder higher as the lane is already open, and so the half-space can be accessed thanks to this double width. There’s also an opportunity to play centrally to the striker.

The problem here though, is that Luton maintain a good shape in their 4-1-4-1, and so a holding midfielder can come across to mark the half-space option. As a result, you need to find a way to create overloads in this area. Even if Luton were in a 4-4-2 here, a central defender could push outwards to press the half-space, and so the creation of an overload in the half-space is vital.

Huddersfield do this excellently and efficiently here, with the full-back making a run into the half-space after playing the pass. We can see the winger drags the full-back wider, and so the half-space opens for Toffolo to run into here, and Huddersfield still have two players available to receive the ball in the box. This is another excellent use of dynamic space occupation.

In this passage of play then, Toffolo performs two roles, as the width and the overloader. Once his width isn’t needed anymore, he can run to perform a role where he is needed. Huddersfield don’t have to commit more players forward to perform these separate roles, and so they are stable enough to deal with a counter-attack if it occurs.

We can see a diagram I have produced below which sums up the basic ideas and roles within most positional play systems, with Huddersfield’s roles also falling within this. We can see width and centrality open the half-space, as does depth, which can be provided by a centre back or central midfielder higher. If the wing-back/full-back can occupy the opposition full-back then this allows for the half-space and opposition centre back to be exploited more effectively. We see the half-space and plus one (or overloader) are also labelled, and they help to create a 2v1 on the centre back. Finally, height and/or centrality are often needed to finish the attack, with assists usually coming from the half-space towards the centre or by penetrating in behind.

We can see another way of overloading the half-space below, with a centre back deep in the half-space being allowed to access the half-space directly. The key to this kind of overload is getting the full-back high enough to either occupy the opposition full-back or to pin a winger deeper. This allows for the half-space lane to open, and it also allows for the full-back to be easily overloaded, which can help give direct access to a centre back if they shift across.

We can see Huddersfield create the overload here by having their inside forward drop deeper in the half-space while a midfielder moves higher. This creates a simple 2v1 on the opposition full-back, and so one player will always be free to receive. These opposite movements are extremely helpful in penetrating through the half-space, and we can see in this example that there is also an opportunity for the full-back to move in behind, which is facilitated by the dropping movement of the inside forward.

When overloads can’t be created, Huddersfield show good individual movement in the half-space at times, with players making movement such as the ones seen here in order to create separation to receive. Here, the inside forward feints to go higher and in behind the Cardiff full-back, before then coming back on himself and dropping deeper to receive. This creates enough separation to allow him to receive.

Rotations

With Corberán having spent time within Marcelo Bielsa’s coaching staff, it is obvious and expected that the two share a similar playing philosophy, and the topic of rotations is one in which we can see a clear shared idea.

When I classify rotations in this section, I am going with the definition of one player vacating space to allow another player to occupy the same space (roughly), or at least play through that space. We can see a simple example below where a Huddersfield players starts more centrally before making a movement around the back of his marker. This movement from in to out opens the passing lane and space for a player to drop deep and receive the ball.

We can see a common rotation below here, where the full-back moves from width into the half-space, while the inside forward moves from the half-space to the wing. The movement of the wing-back almost acts as a shield for the pass out wide, and so the winger can receive the ball with the aim of then playing quickly into a dynamic full-back. Defenders may also not cope well with the rotations and so space can be created in this way too. Their rotations are still a work in progress however and they haven’t mastered this concept yet, which is to be expected after such a short period of time. Here for example, the positional structure is not quite set for the rotation to have it’s full effect, as when the ball goes wide, the central midfielder is not in a position to occupy the opposition central midfielder, meaning the half-space lane does not open much.

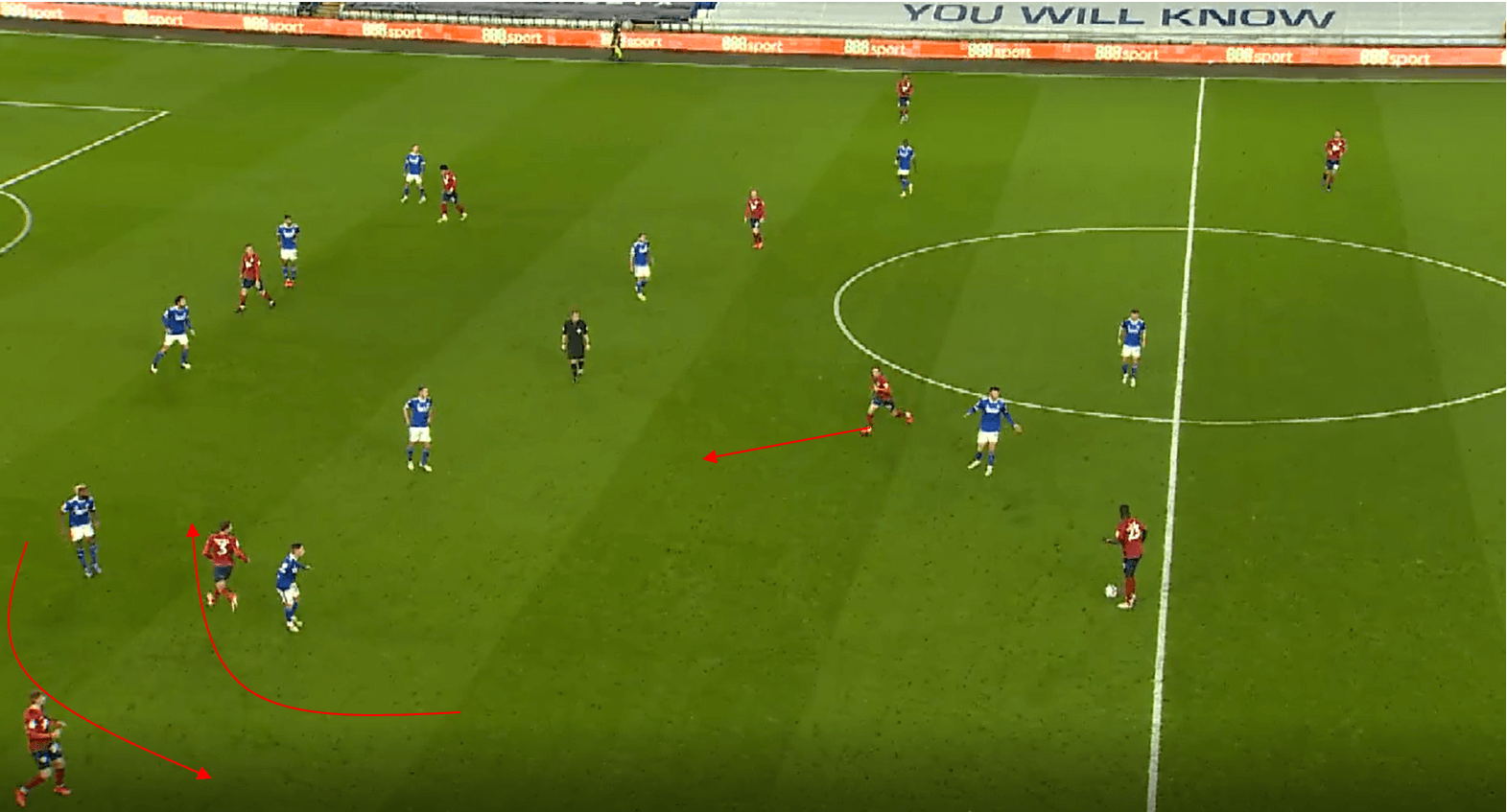

We can see an example of another rotation below, where the striker and inside forward swap roles in order to create space. The inside forward initially occupies the half-space and the opposition full-back, but the striker rotates and moves behind the full-back to occupy him. The inside forward therefore moves centrally and into the space vacated by the striker.

The striker’s movement drags the central defender and full-back away slightly, and so space opens up for the inside forward to receive in this space. The movement here is good, but the execution is slightly off, with the timing of the striker’s run not allowing him to receive the ball, and the general support around the receiver poor. The rotation offers a clear advantage though as it drags defender’s out of the target space and allows more players to be positioned higher.

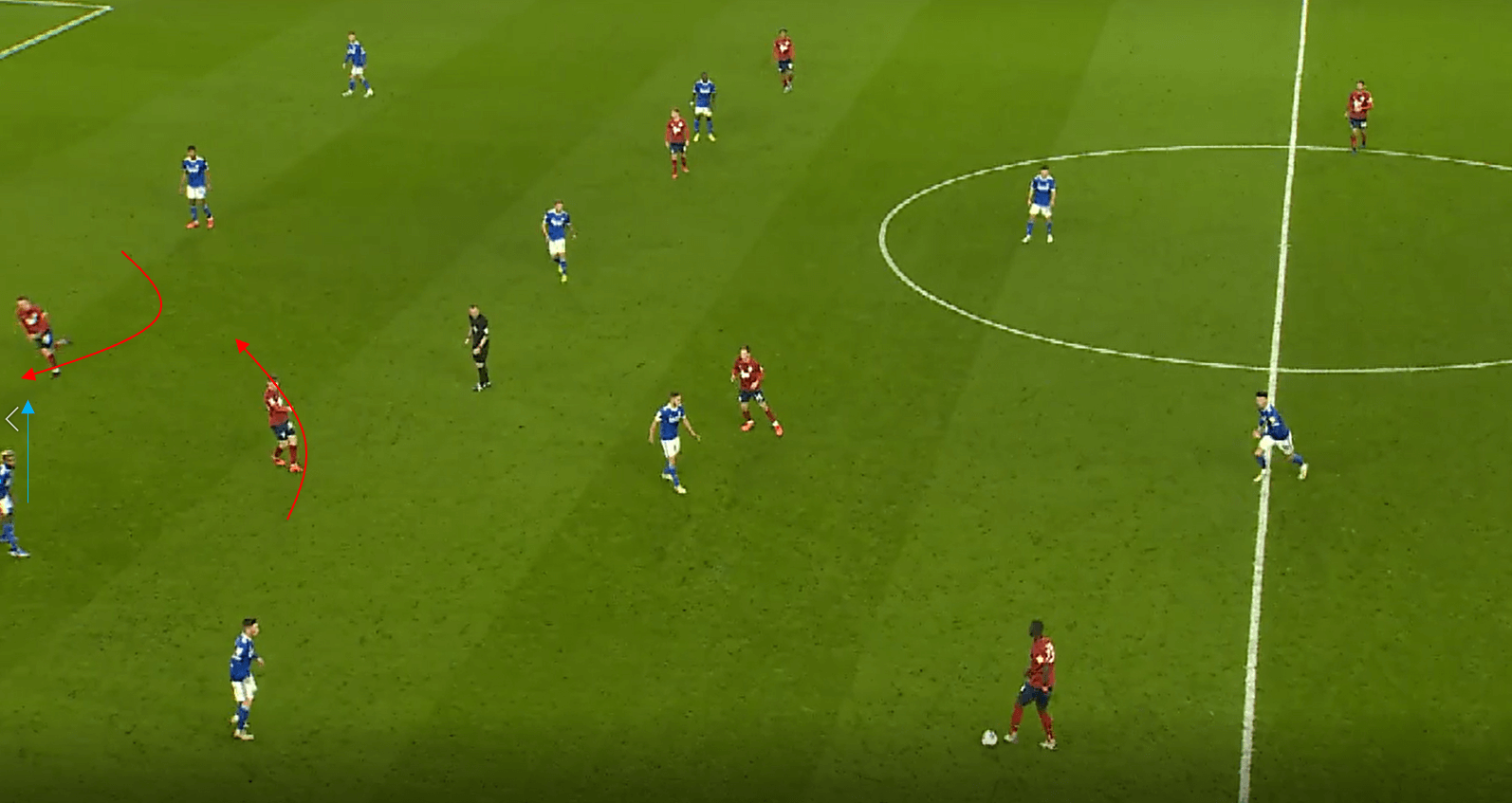

Previously in the analysis I showed the use of rotations within central midfield to dismark opponents and create a free player, and we can see an example of this again against Luton. Here, Huddersfield initially sit with a single pivot, but a higher central midfielder drops deeper. This dropping movement is complemented by the pivot (Hogg) making a higher movement in behind, and so he can dismark his opponent and look to receive the ball. Huddersfield still have work to do regarding players reading rotations and third man runs, but there are promising signs for sure.

They will also use these kinds of opposite movements in the half-space at times, with the inside forward potentially dropping deeper and dragging a full-back higher in order to allow the full-back to make a run in behind.

Dynamic space occupation and third man runs

One area they have been excellent in so far this season has been their use of dynamic space occupation, with a clear principle within Huddersfield’s build-up being to pass and move. We can see an example of this here, with an overload created on the opposition full-back using dynamic space occupation. The full-back plays the ball into the inside forward, who holds the ball up. The full-back follows his pass and looks to run forward to penetrate in behind, and so the inside forward simply holds the ball and then lays it into the full-backs path.

This play demonstrates a few of the advantages of dynamic space occupation, which are listed below:

- Allow for ball progression using less players

- Players arrive into space facing towards the goal

- Improved body orientation allows for improved passing options

- Players arrive into vacant space, so harder for the opposition to press

- Opportunity to counter-press immediately if first pass is poor

- Allows previously inaccessible players to receive the ball.

The full-back can immediately play forward when they move to receive the ball, and is automatically facing towards goal, meaning they can drive into space at speed. We can see the clear advantage if we compare this to the body orientation of the inside forward, who cannot play forward and who’s passing options are limited.

We can see another example of an overload being created in the half-space using dynamic space occupation here, with initially the defending team in a not too awful defensive situation. The full-back has been dragged wider by the Huddersfield full back, and so the centre back steps to defend the half-space, with it currently a 1v1. The central midfielder plays the ball into the half-space and continues his run, and so a 2v1 overload is created in the half space.

Here, the inside forward deliberately comes deeper and delays his run forward, as it gives him more space to arrive into. This means that when he does receive the ball, he can do so facing forward, and so his range of passing is increased compared to moving higher and receiving with his back to goal.

We saw some examples previously of this dynamic space occupation being used in a deeper area, and we can see a nice example again below, where the opposition initially mark the central options, forcing Huddersfield wide. The Huddersfield midfielders don’t come too deep, and so leave room in the pivot space for a centre back to move from out of the back three and to act as a six. This allows them to receive the ball in this area, create a central overload, and relieve pressure.

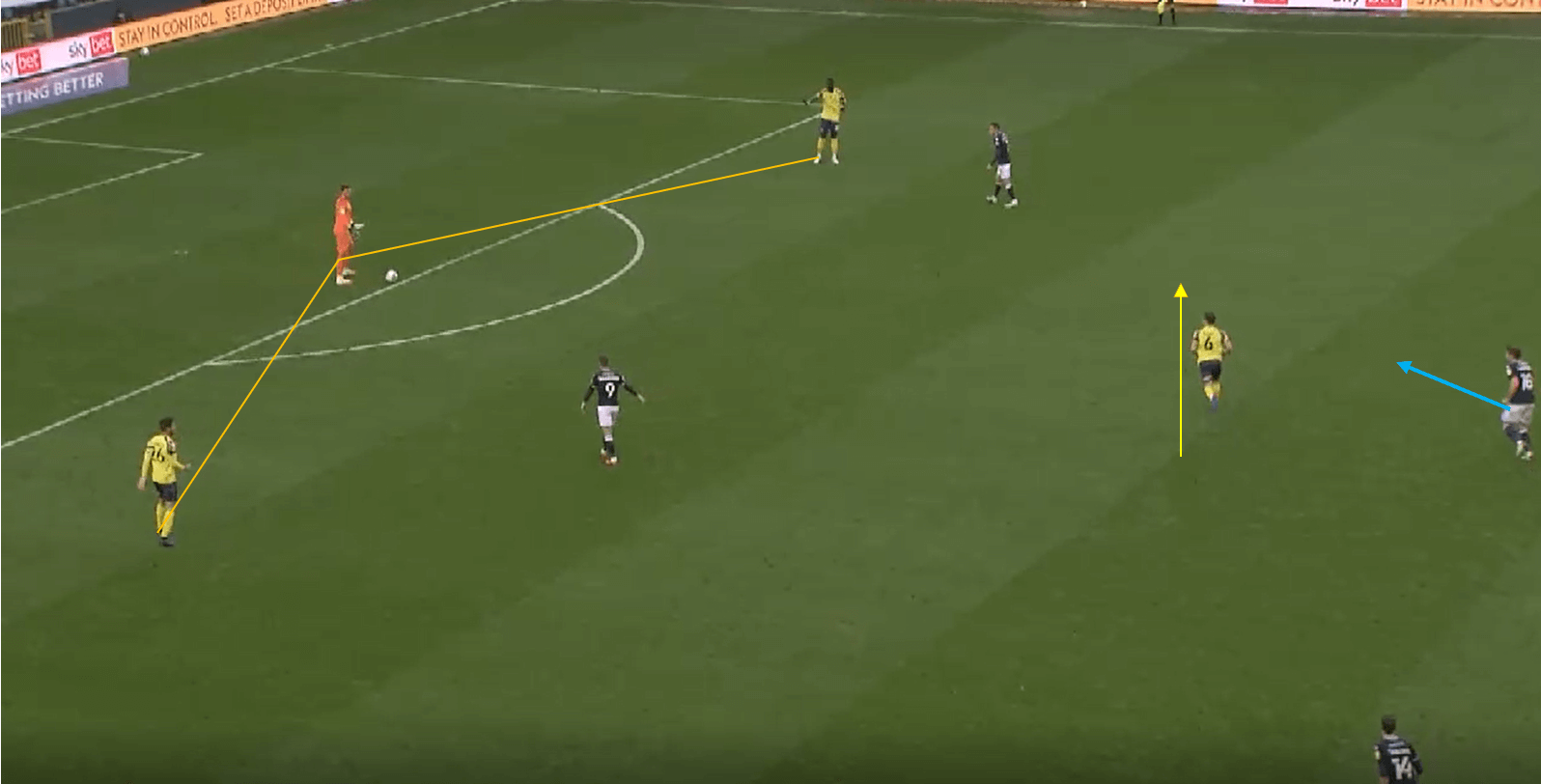

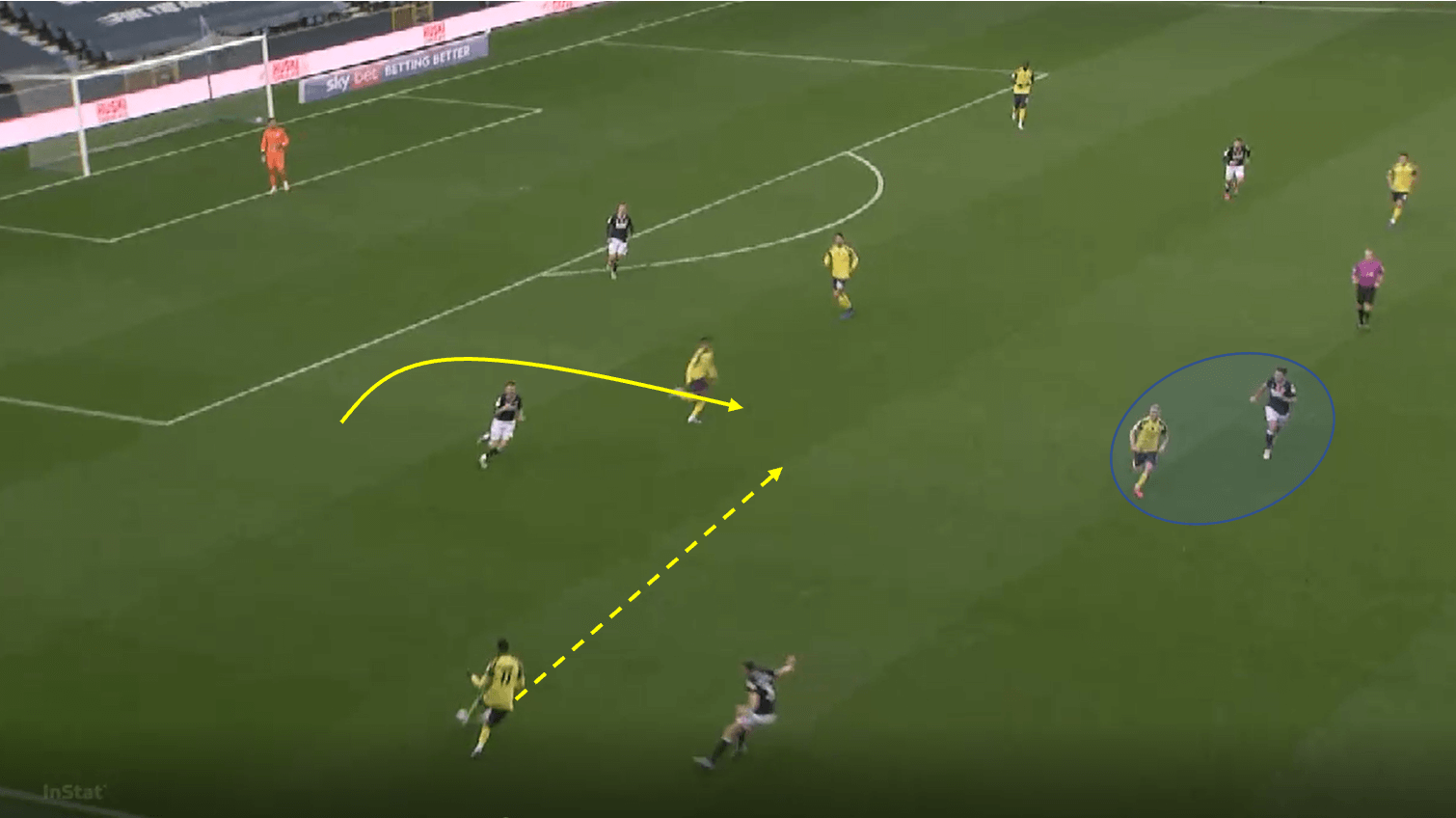

The concept of third man runs come within dynamic space occupation also, as the idea is to move from an area where you couldn’t be accessed, to an area where you can. We can see a really simple example here from their game against Millwall, with a direct ball played to the furthest player, which allows for a new player to receive with good body orientation. The ball is played direct into the striker, who has a central midfielder close by. Before the first pass is played, the central midfielder could receive the ball, but he is facing his own goal and has no real progressive passing options. As a result, they play to the central striker in order to allow the central midfielder to receive a lay off and arrive onto the ball. As a result, Huddersfield can outplay the pressure and switch the ball to the left.

The best example which ties all of this together was seen in a match against QPR, where Huddersfield created a great goalscoring opportunity from a goal kick in a series of intricate passes and runs.

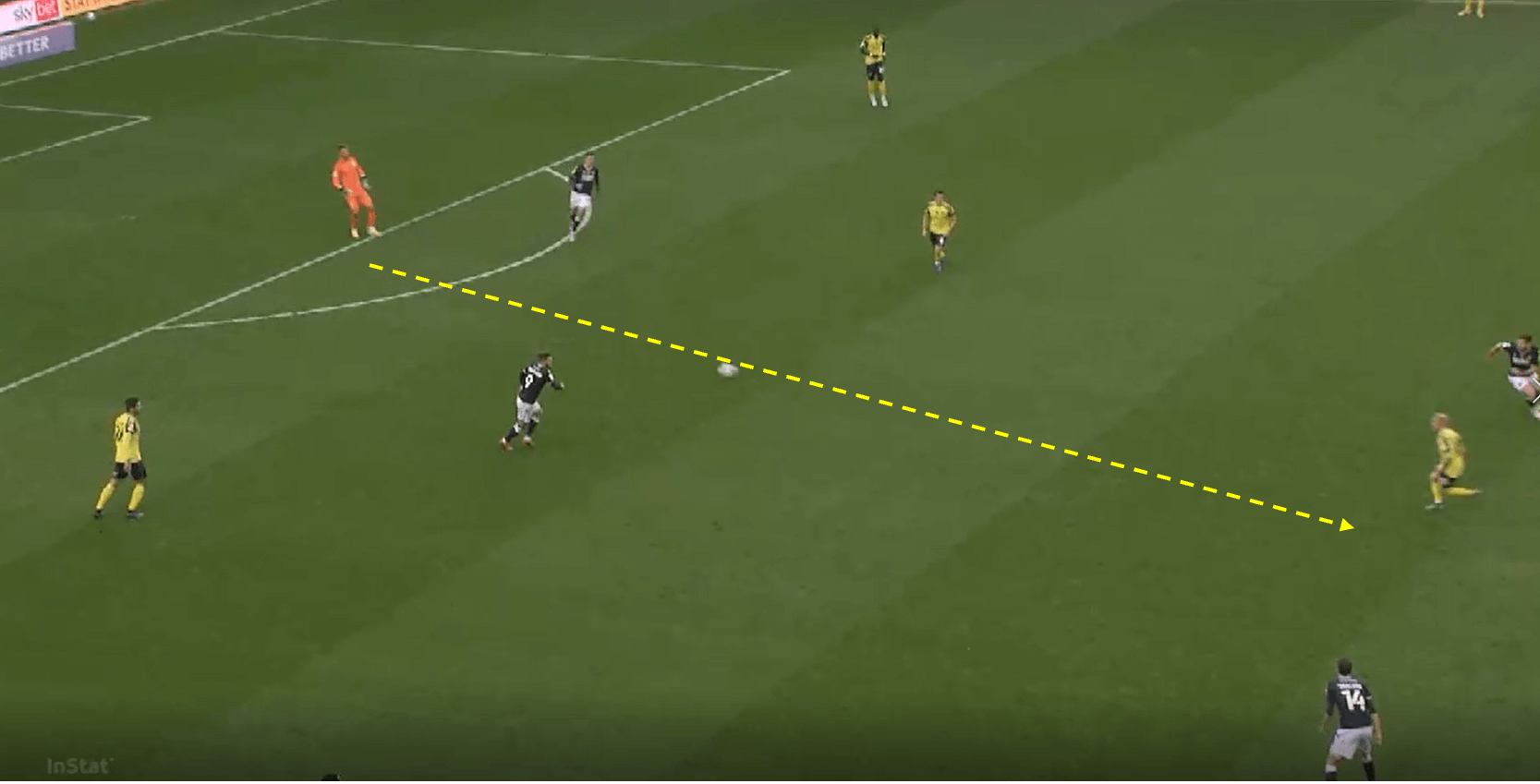

Play starts with the goalkeeper passing the ball to the right centre back in the box. The right centre back plays the ball into the full-back, and continues his run to move past his marker and receive the ball again. While the centre back makes this run, a central midfielder previously occupying the half-space moves towards the centre to open the half-space lane.

The centre back receives the ball, and the half-space lane is opened thanks to the movement noted earlier by the central midfielder. The striker receives the ball, and the far central midfielder makes a run into the space slightly behind and to the striker’s right (our left). This movement is timed well, and so he arrives onto the ball facing forward/diagonal. The right winger has continued a run, and so he can complete the third man concept. The far midfielder continues his run and gets the ball back again, before crossing the ball to the onrushing midfielders at the far post.

It is an amazing piece of football that had it resulted in a goal, you probably would have seen by now. This passage of play also shows most of the in possession principles Carlos Corberán seems to be trying to incorporate at the club, with rotations, third man runs, dynamic space occupation and somewhat of an overload in the half-space all used.

They seem to have some patterns within these, such as triangles around the full-back, central midfielder and winger used often in third man runs, which they used well in their goal against Derby which you can look up.

Out of possession and defensive transitions

This analysis has mainly focused on the in possession principles implemented so far by Carlos Corberán, and that is simply down to the number of trends and interesting ideas seen within their build-up. Within any expansive system, the need for balance is key, and so rest defence around defensive transitions is vital.

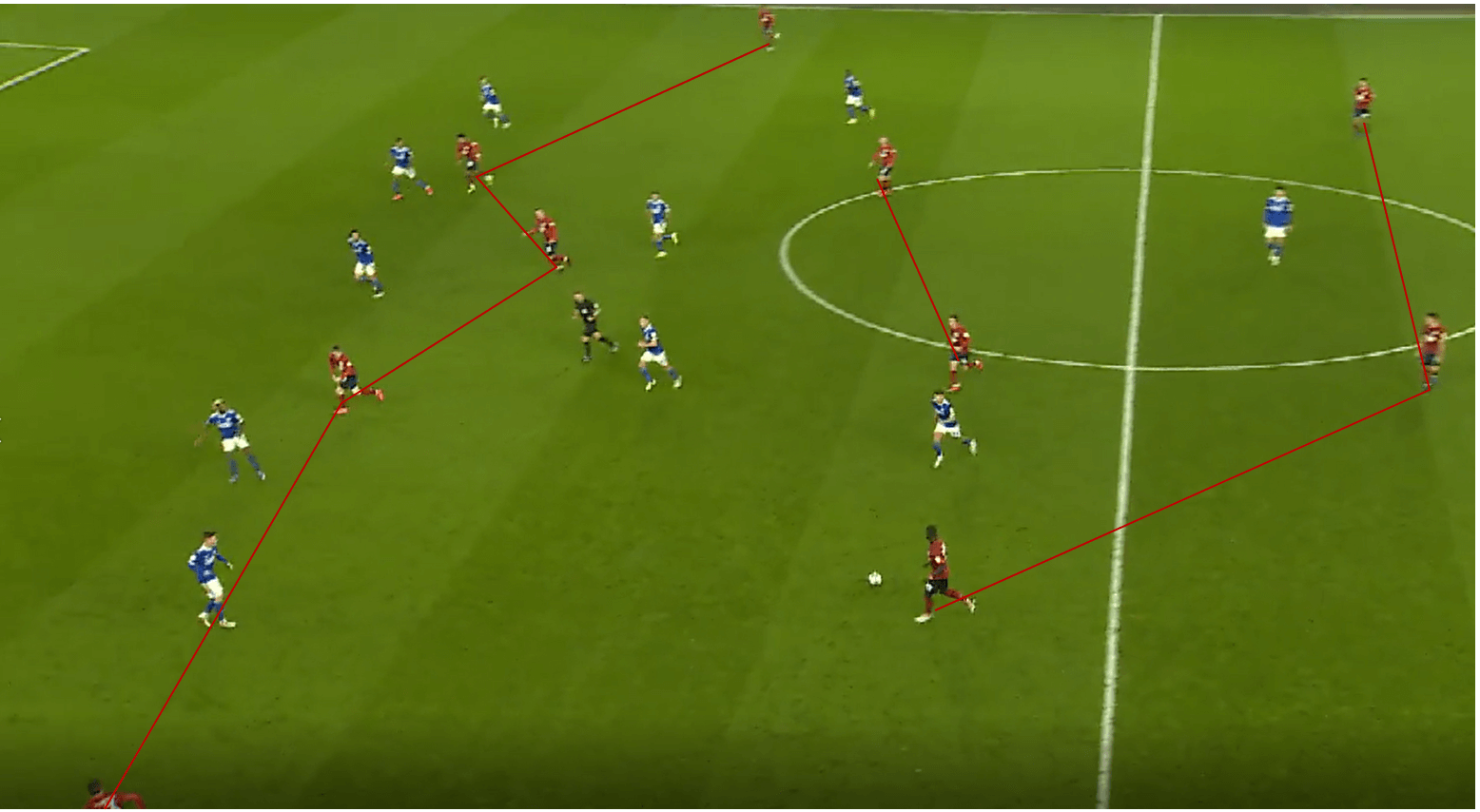

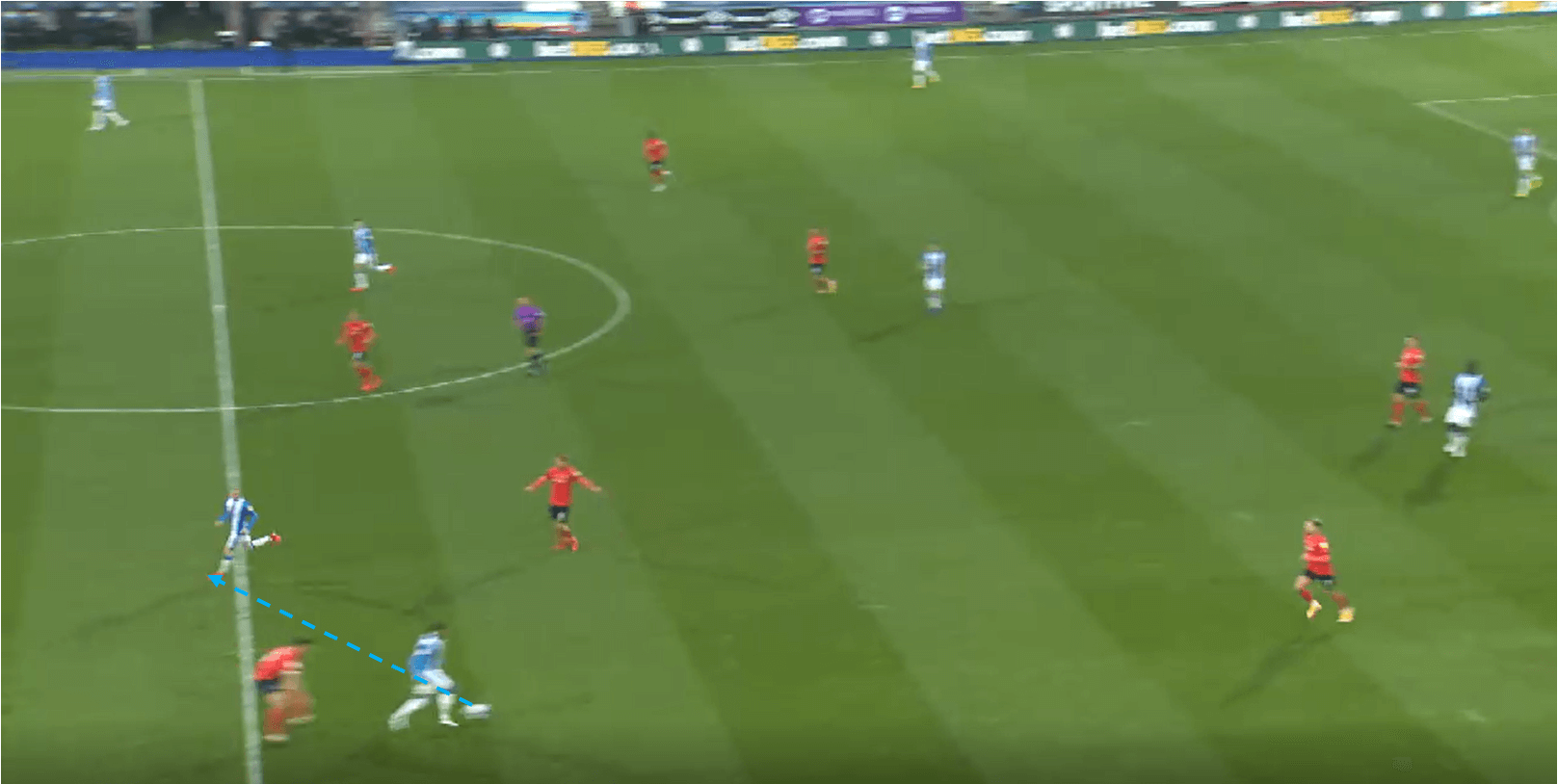

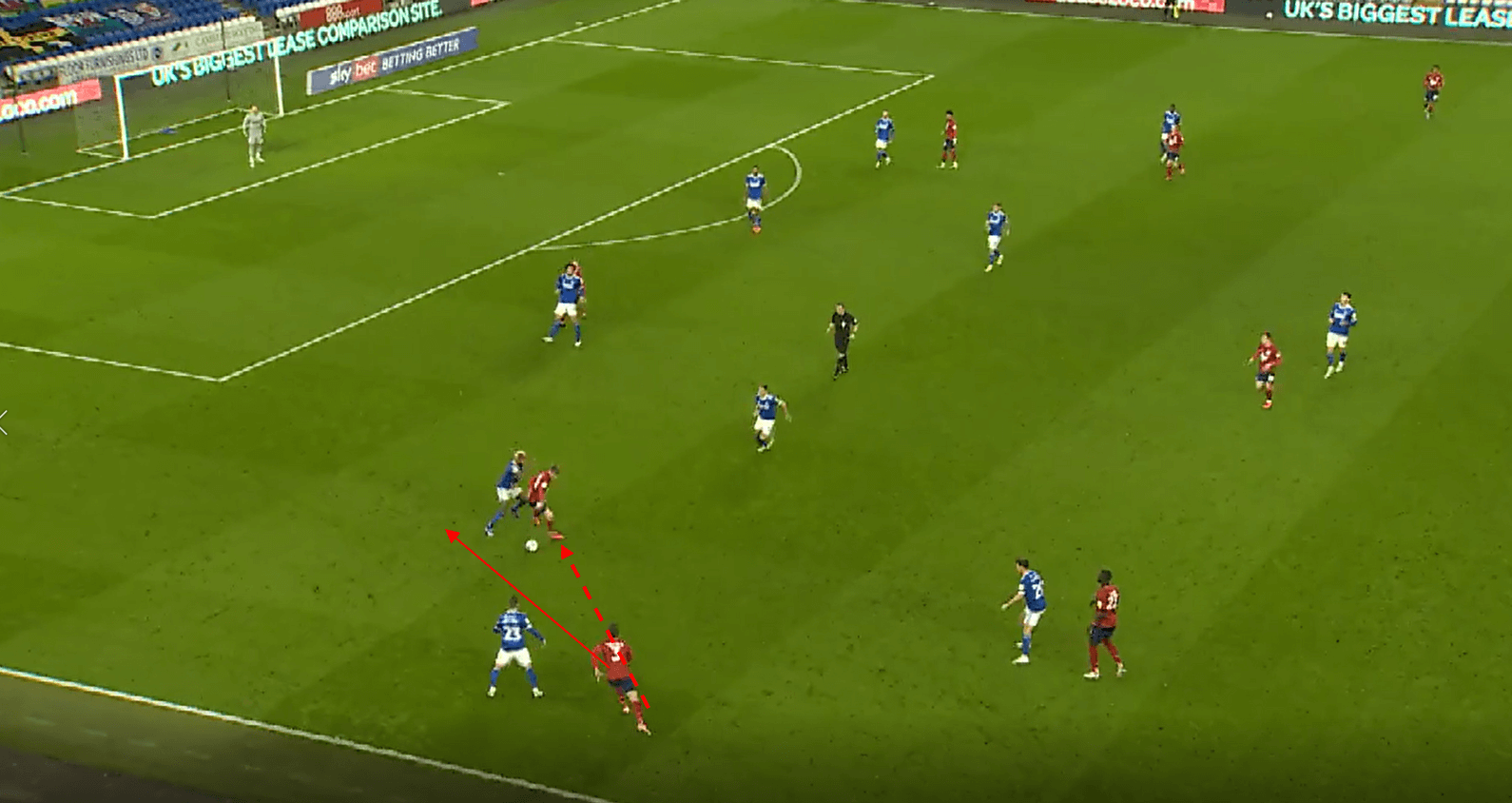

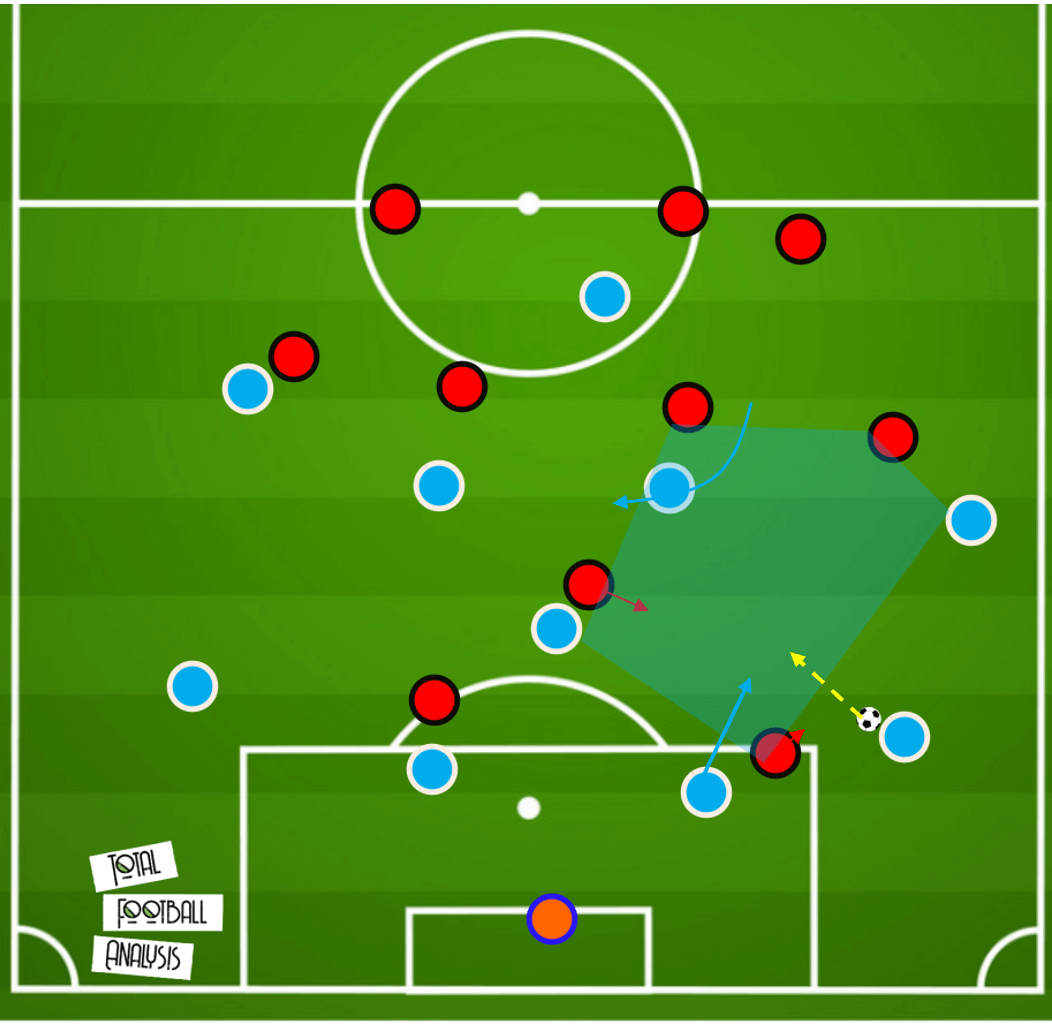

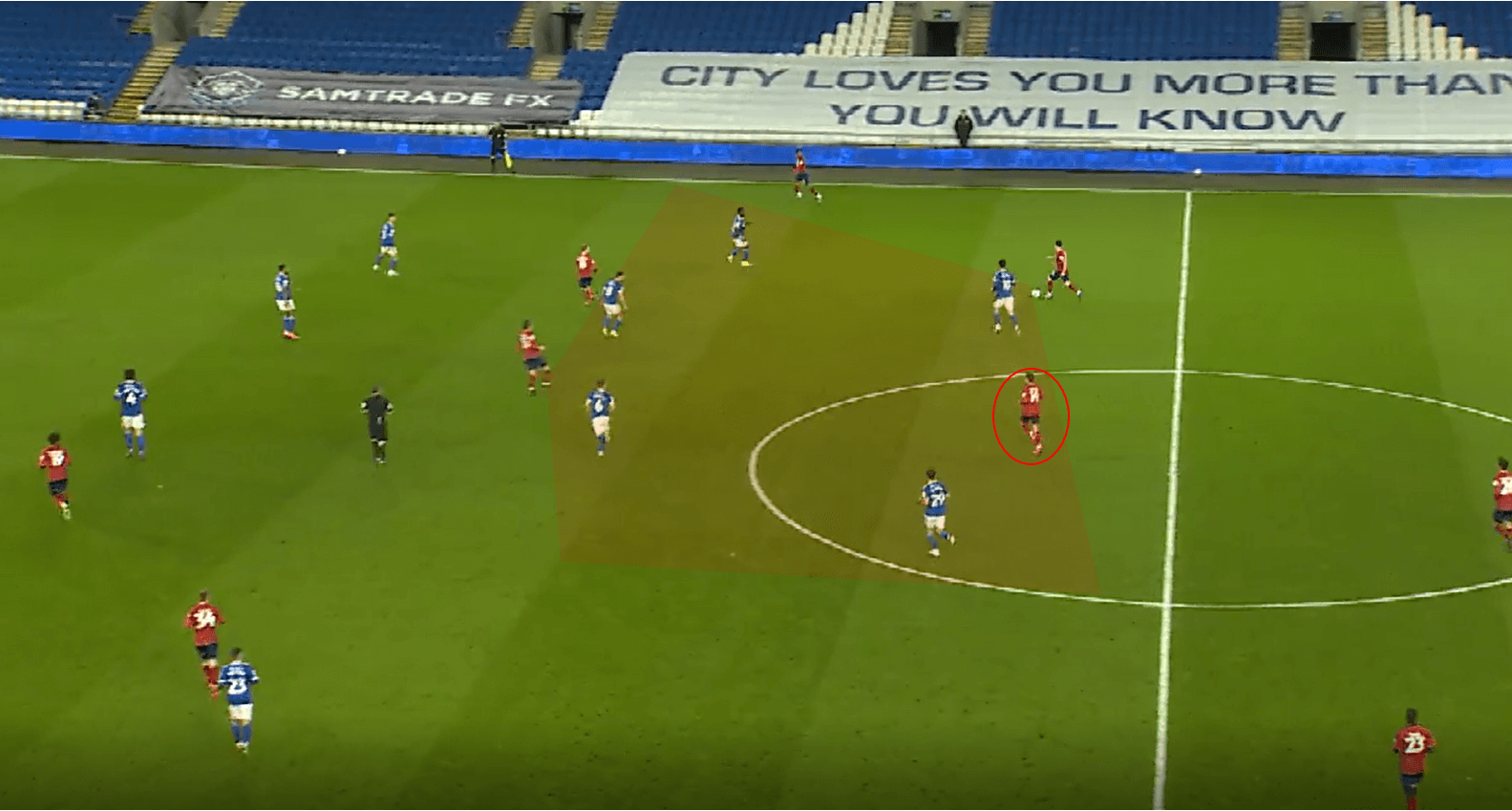

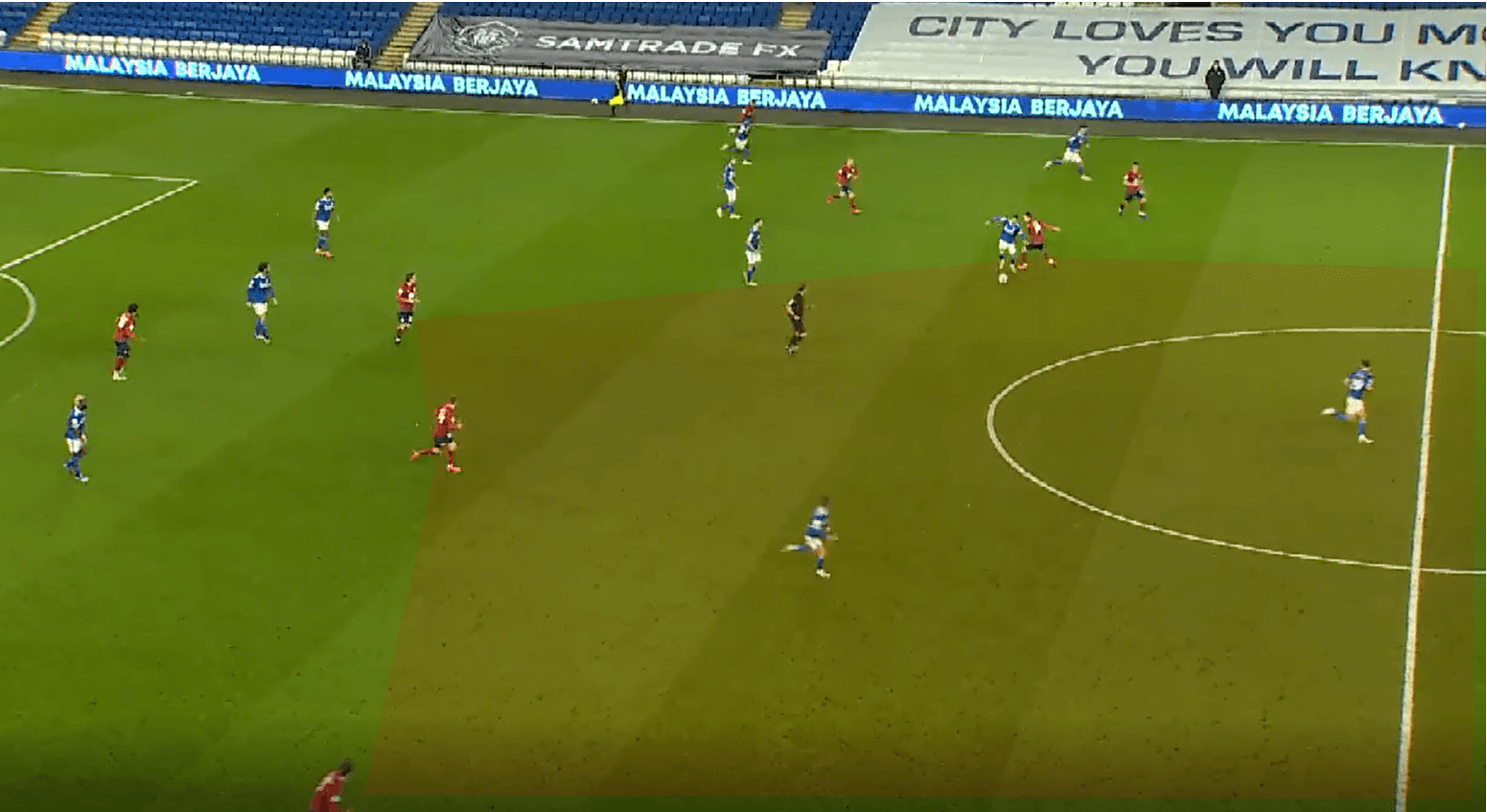

Balancing this risk and reward is a vital dilemma in football, and at times this season Huddersfield have just been caught playing slightly too riskily. We can see an example against Cardiff here where the central midfielder moves higher and into the half-space to receive, which following a switch leaves only the holding midfielder close to the ball ( as well as the back three).

As a result, when the ball is lost, only one player is available to immediately counter-press to cut out the danger, and so when this player is bypassed as he is here, we can see the space the opposition are afforded in the counter-attack.

To limit these counter attacking opportunities for the opposition while playing expansively, you either have to maintain a safe structure to deal with counter attacks, or you have to not give the ball away as much. Huddersfield do still struggle at times with technical execution and give the ball away cheaply at times and so this certainly needs improved, but in the long term maintaining a safer structure is a better option.

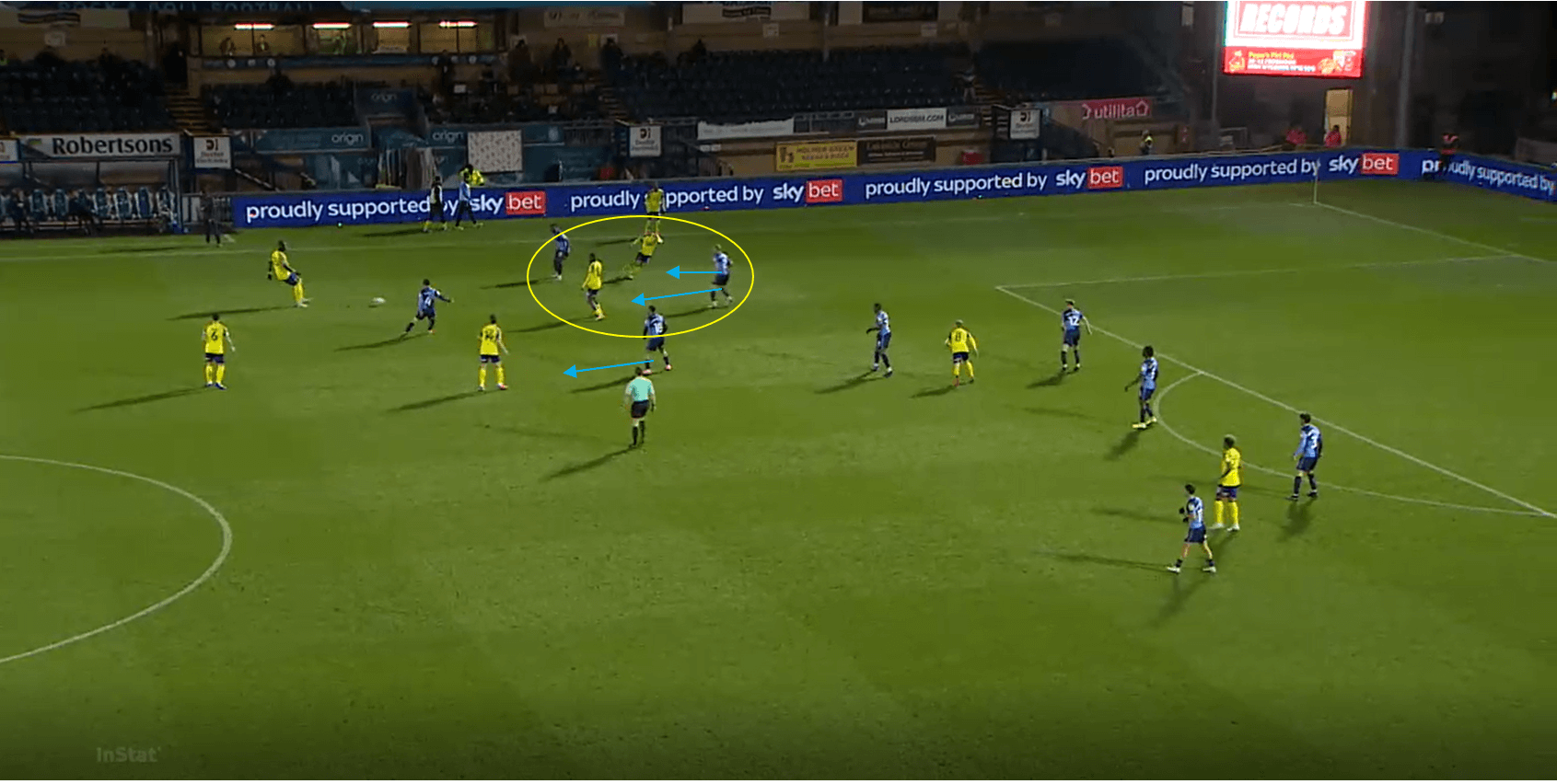

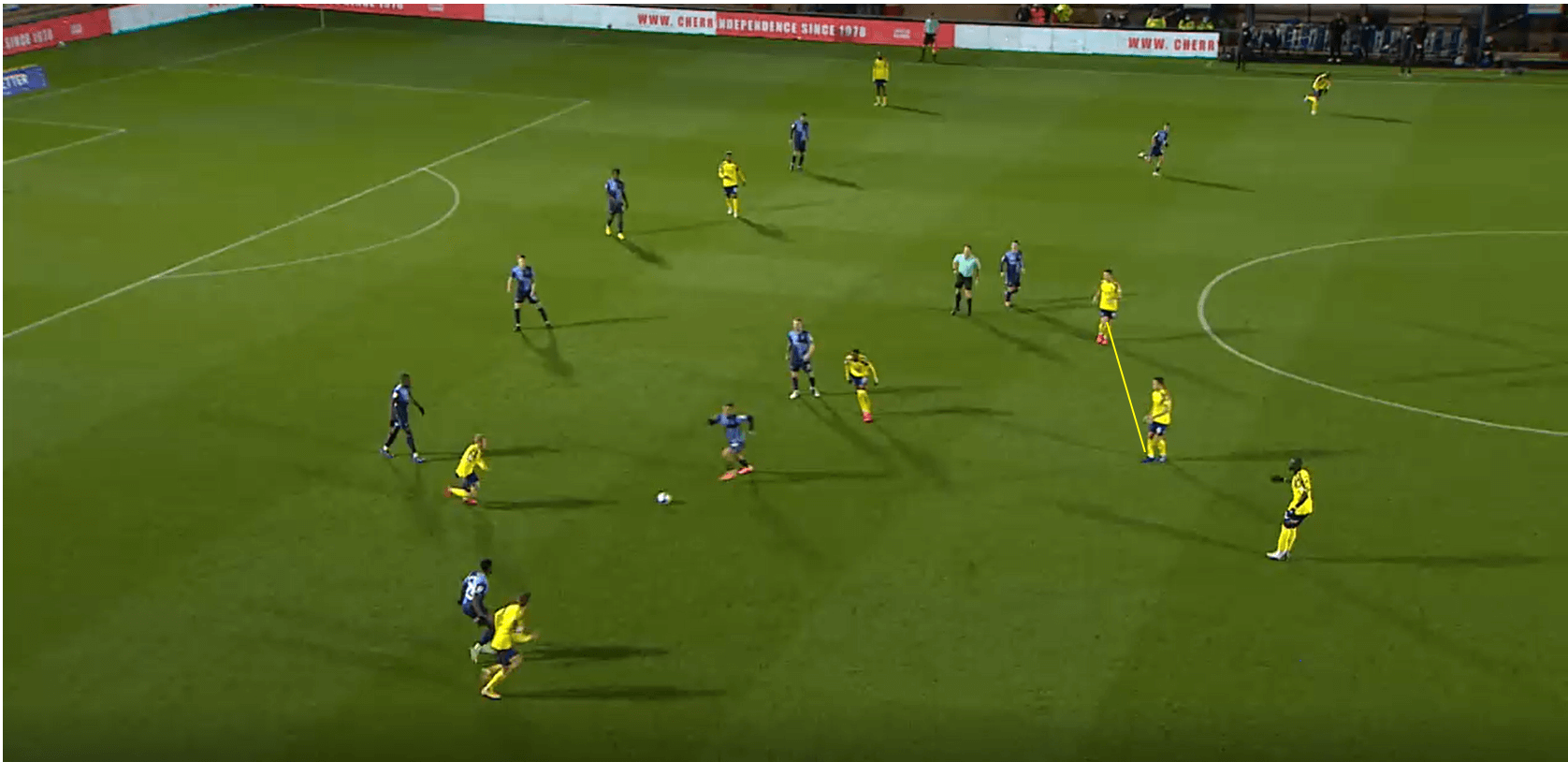

Against Wycombe, they were able to maintain two central midfielders closer to ball when it was lost, and so Wycombe posed less of a threat in transition. Most teams like to maintain a similar kind of structure, with at least one of the two central midfielders directly in line with the ball to counter press vertically if needed.

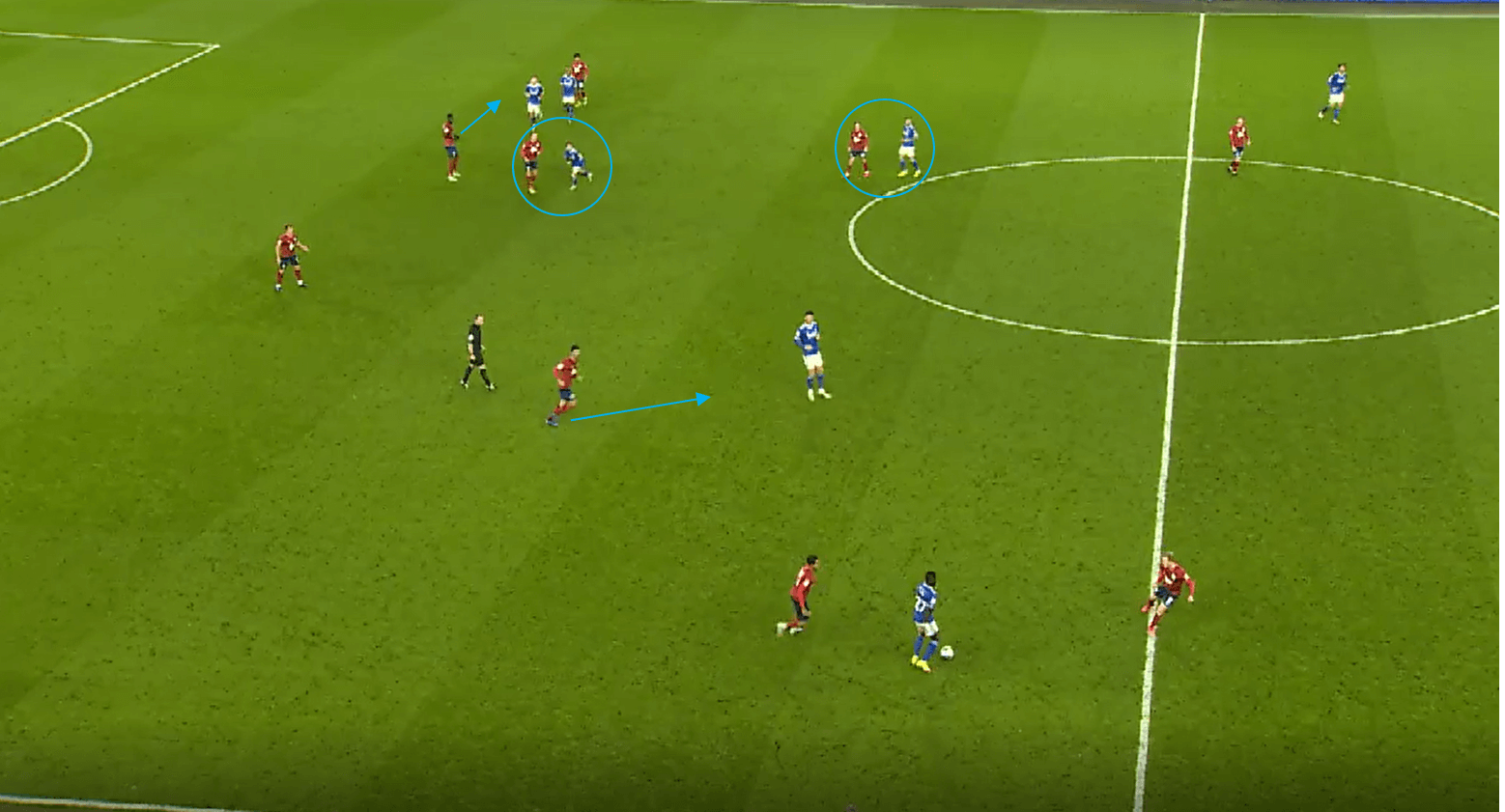

From direct pressing, Huddersfield use a similar system to that of Leeds, with players mainly man oriented and looking to maintain pressure on the ball carrier when possible. They will press out of a base of a 4-1-4-1, but players will often jump to maintain pressure on the ball and so it is often a little chaotic. The striker will often look to press from the side as we can see here, as this helps to cut access to one side of the pitch, and therefore makes it easier for the one striker to press two centre backs. We can see the midfield four stays tight to their markers here, and will follow them unless pressure on the ball is lost.

We can see here the central midfielder takes the opportunity to jump higher here after following his marker deep, while the rest of the midfield behind him still remains tight.

Centre backs will follow players high if needed, and midfielders will drop deep with players, and so the structure of the 4-1-4-1 is often lost. We can see an example of the man orientations below where players stay tight to their players, and prioritise getting close and cutting access to players, regardless of the space they leave elsewhere. We can see the large space opening behind the full-back, who pushes high regardless in order to press this nearby player.

Conclusion

This analysis has mainly looked at the in possession tactics and concepts used by Carlos Corberán so far this season. The influence from Bielsa and others is clear to see, but to focus solely on this influence I would say could be somewhat disrespectful to the work Corberán is doing himself in coaching Huddersfield to adopt this philosophy. Huddersfield sit seven points from a playoff spot at the time of writing this, but some disappointing results were to be expected during the teething process when coaching this idea of football.

Huddersfield are certainly not where Corberán wants them to be just yet in probably all phases of the game, and they still struggle occasionally with the timing of rotations and dynamic runs, as well as reading and reacting to third man opportunities to name a few areas. The philosophy though, is clear and has shown it can be successful. There will be more bumps along the road while the system fully embeds itself, but with the job Corberán has done in six months with the current Huddersfield squad , if he is backed, I would expect them to be a promotion contender next season, which is why I chose to write this piece.

Comments