Matches in the Premier League are coming thick and fast for Thomas Tuchel since he arrived as Chelsea boss, and his biggest test so far saw him match up against José Mourinho’s Tottenham. Tottenham came into the game on the back of two disappointing performances and defeats at the hands of Liverpool and Brighton, and the game looked as though it would be a good match up for Mourinho, with his style of play contrasting Tuchel’s mainly possession-based approach. In the end though, it was a similarly disappointing performance from Spurs as we had seen in recent weeks, with Chelsea able to secure a 1-0 away win at the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

The game saw Mourinho set his side up pragmatically to deal with Chelsea’s build-up, but the system itself was largely ineffective in the first half and Chelsea were able to play through and exploit it well. At the other end, this defensive system, as well as personnel, seemed to greatly reduce the counter-attacking threat of Spurs, and so the game from their point of view was a rather stale one with virtually no chances created. In this tactical analysis, we will focus mainly on this unorthodox system that was used in the first half, examining how Chelsea were able to exploit the system using positional play concepts, as well as then looking at how Spurs adjusted.

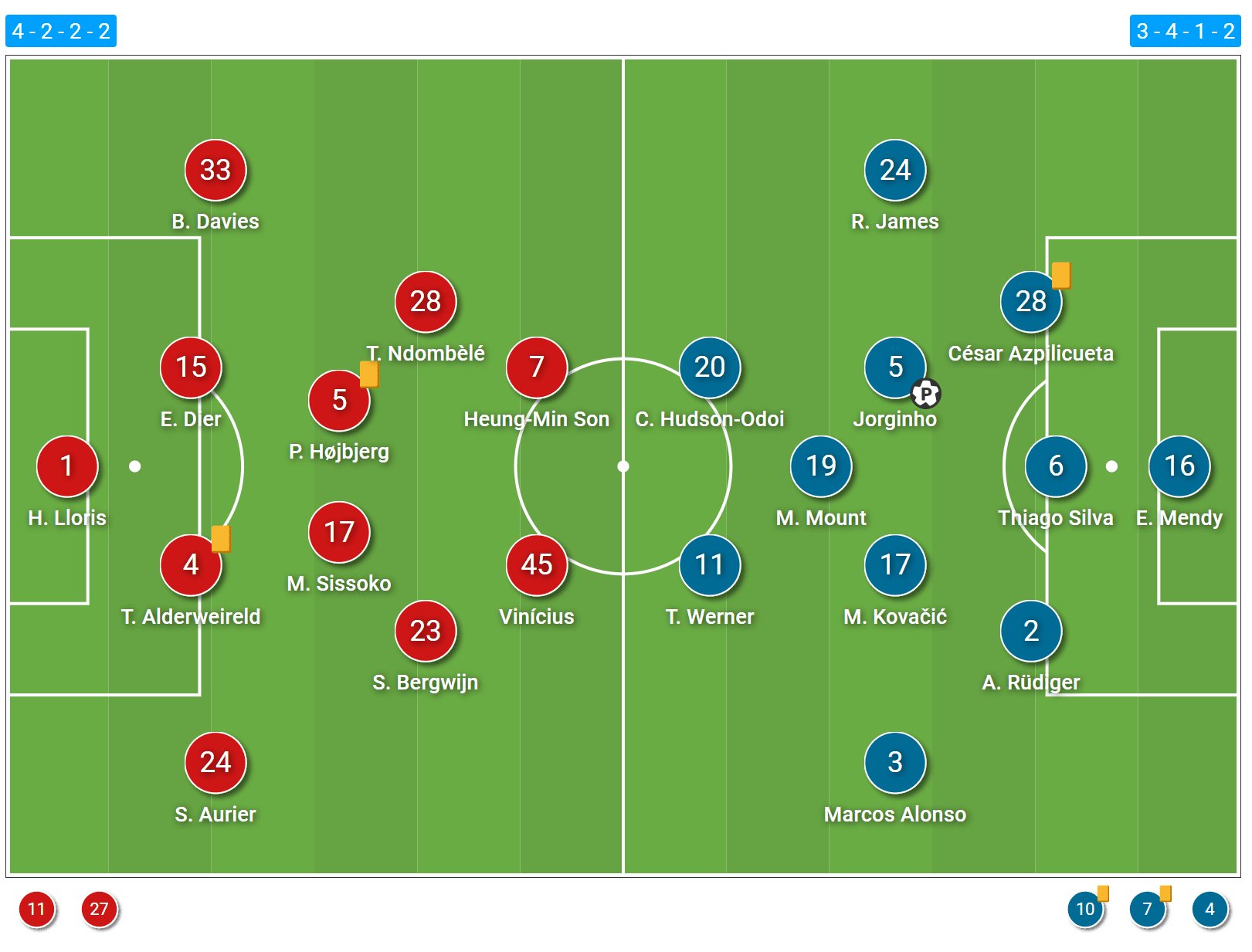

Lineups

We can see the pragmatic system that Spurs used in the first half below, with the 4-2-2-2 used. Pierre-Emile Højbjerg and Moussa Sissoko started as the holding midfielders for Spurs, while Tanguy Ndombele and Steven Bergwijn acted as narrow pressing tens. Chelsea went with a 3-4-1-2, with Mason Mount in a fluid role as a ten and Callum Hudson-Odoi and Timo Werner as the strikers.

Spurs’ 4-2-2-2

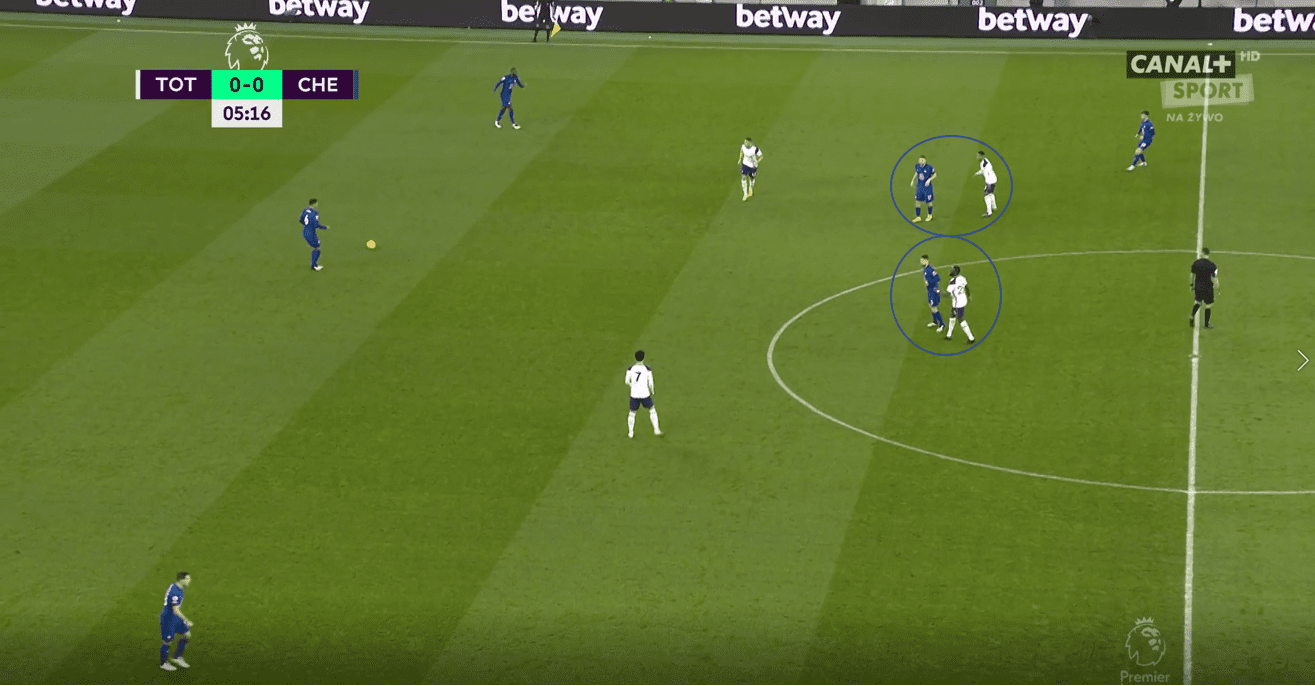

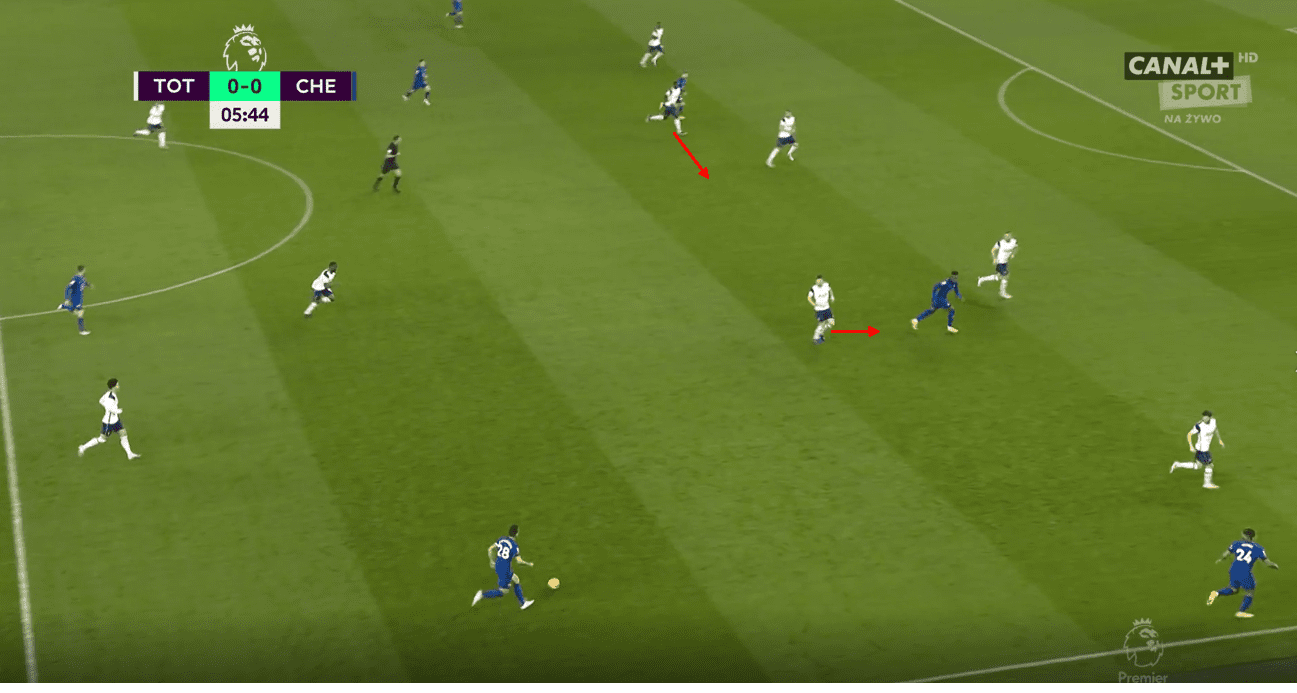

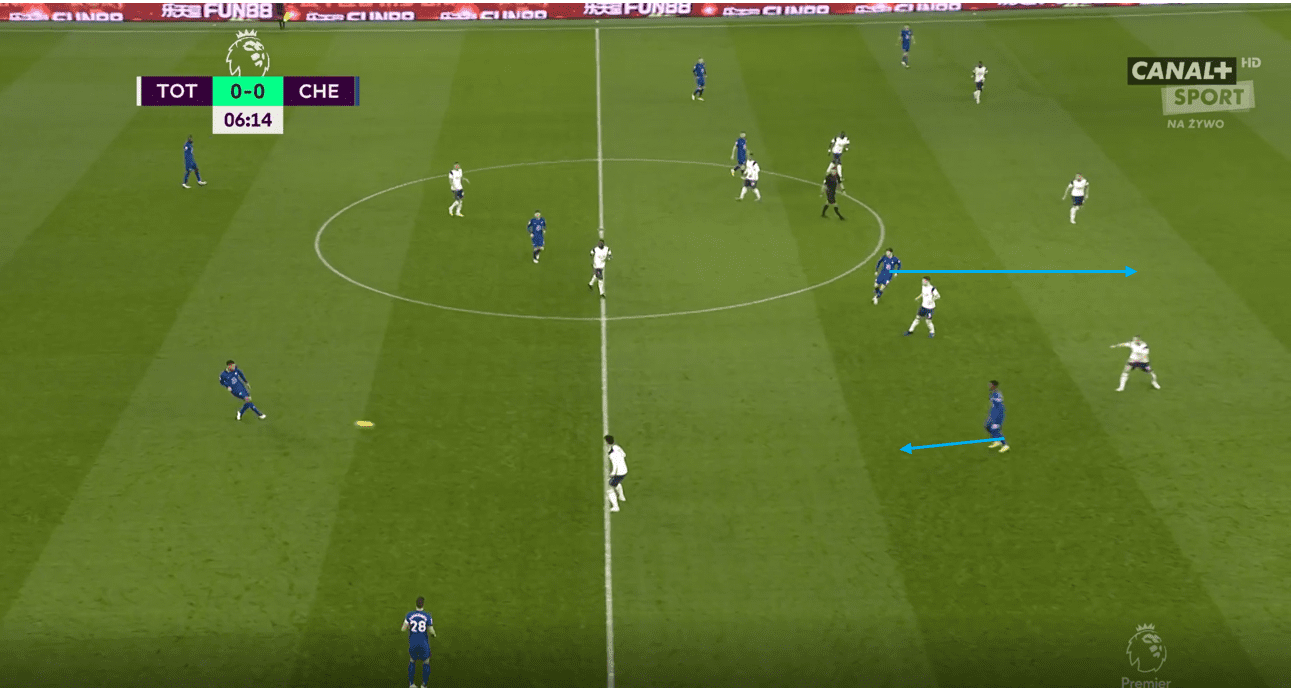

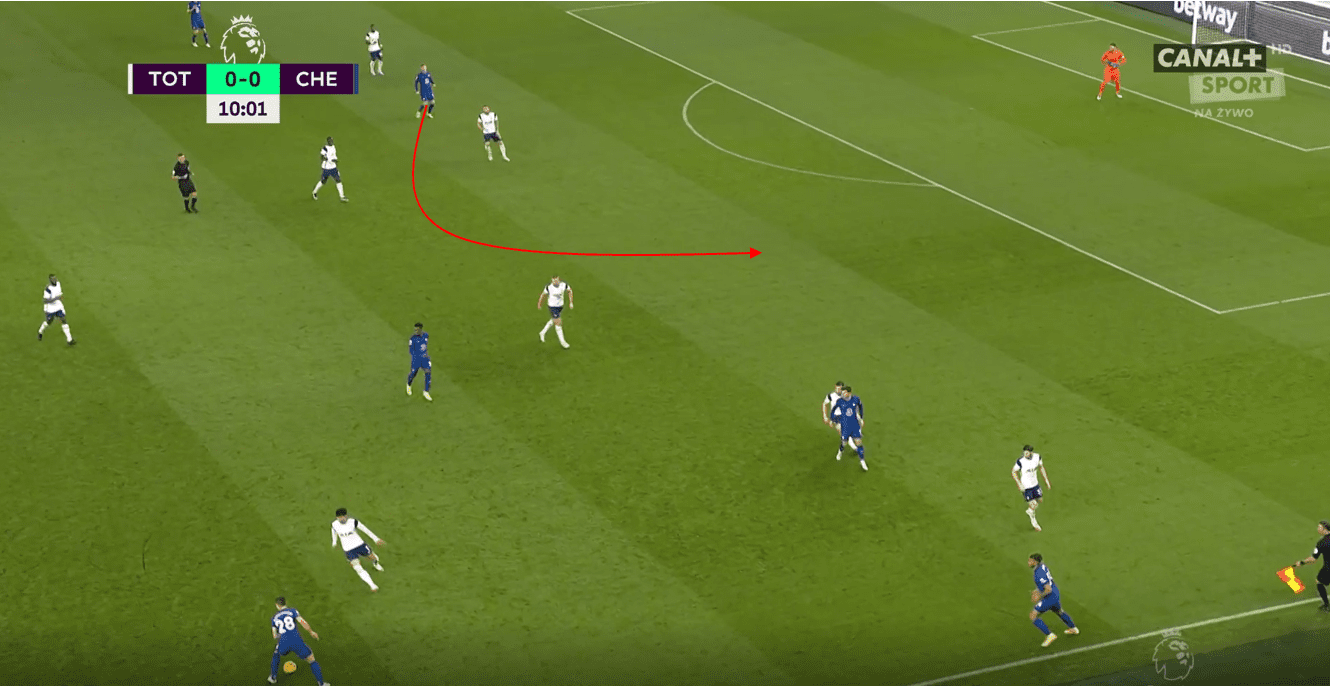

The aim behind Spurs’ 4-2-2-2 seemed to be to restrict central options for Chelsea, with basically a four-man midfield theoretically nullifying overloads in this area. The two number tens were very narrow and quite man-oriented in their pressing, in that they strictly marked the Chelsea central midfielders as we can see below. Spurs’ strikers were fairly passive in their role, and didn’t protect the centre of the pitch.

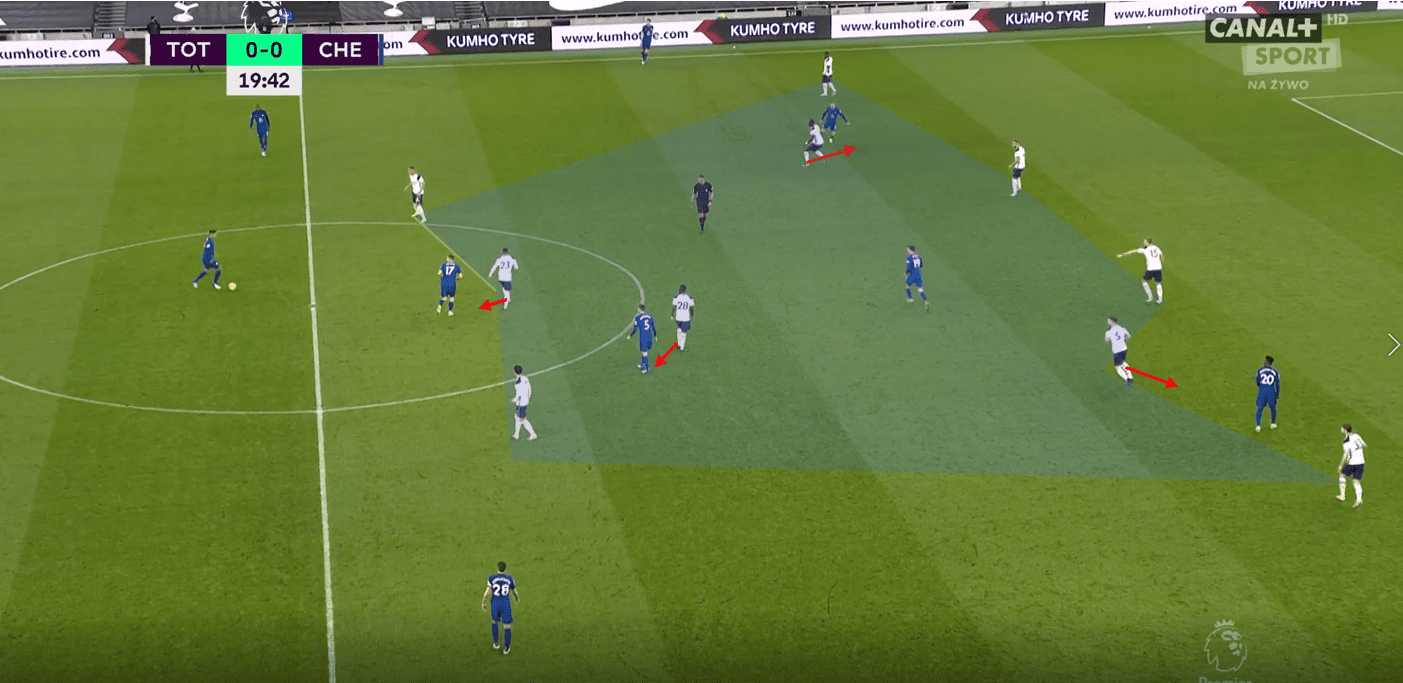

We can see a good image of Tottenham’s general structure here, with roles clearly allocated. The middle centre back in the three for Chelsea was often allowed time on the ball, as the central options should theoretically be cut off and so any passes into here should be covered well. The two deeper midfielders were more zonal in their marking than their higher midfield teammates, in that they generally looked to cover the half-spaces, and so would pull wider usually rather than occupy the centre, which is why we can see that large central space in the image below.

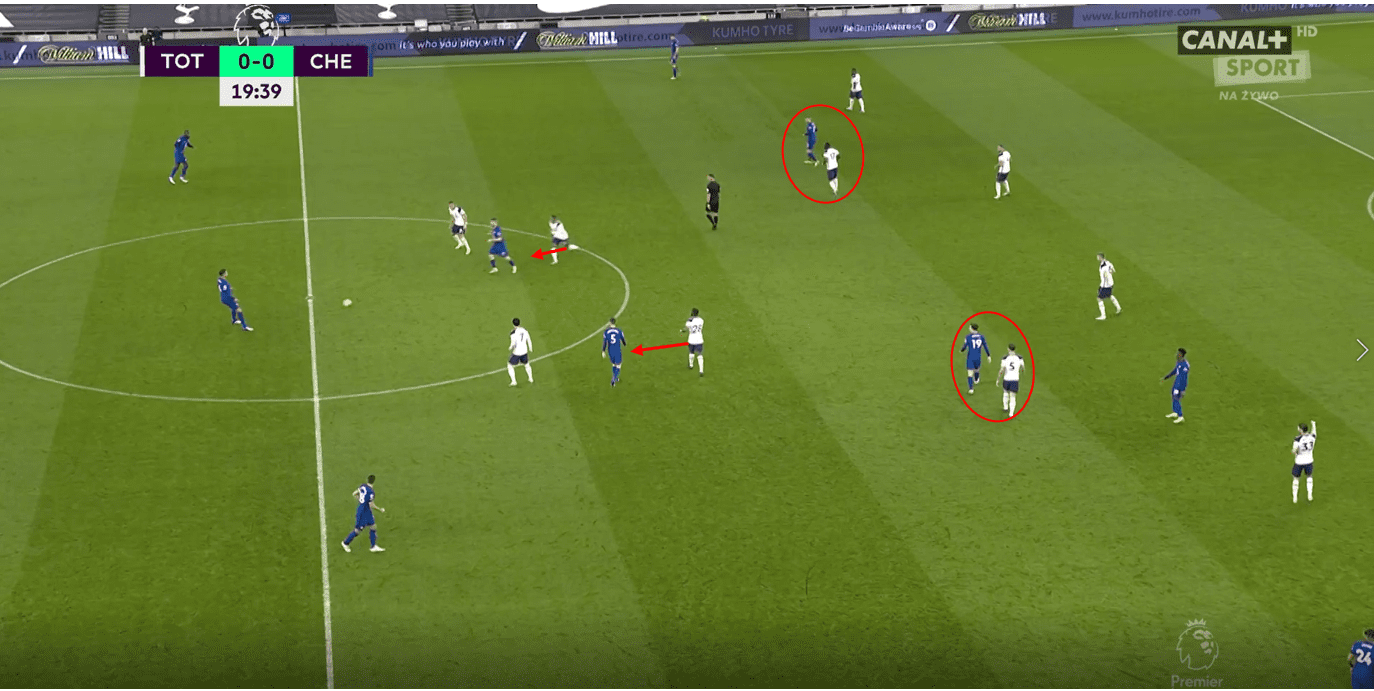

The role of the strikers was a slightly unorthodox one in that they actively left the half-space open and were passive, and so Heung Min Son’s role was often bordering on pointless. We can see in the example below the general idea behind the structure in that the half-space is left open, but Højbjerg can cover across with Mount if he drops into this space, and so the threat in this area can be managed. The man orientations of the Spurs tens means that if the ball is switched between centre backs, or if Chelsea deliberately stay away from wider areas with their central midfielders, the space remains uncovered. Son looks to show the ball into this area and press the wide pass.

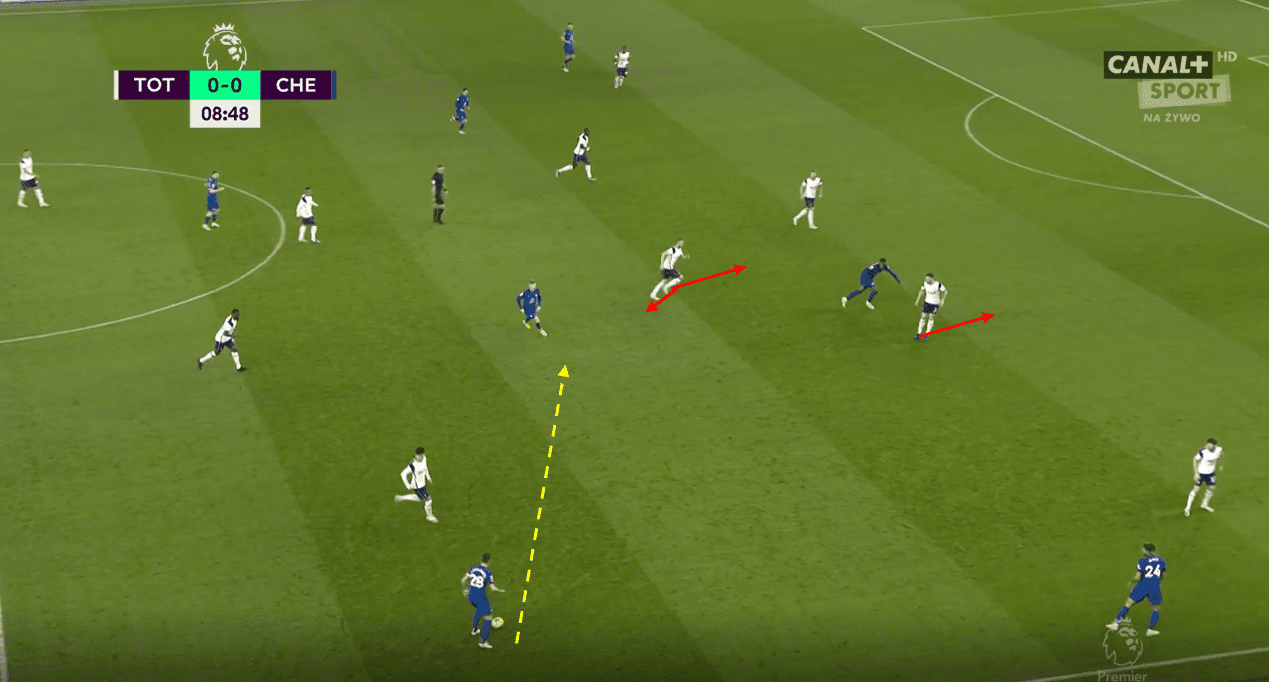

We can see a similar example here, where Højbjerg moves wide initially to cover Mason Mount’s movement. The central lane opens due to Sissoko not covering across, something he didn’t do well early on due to his own orientation around the far half-space.

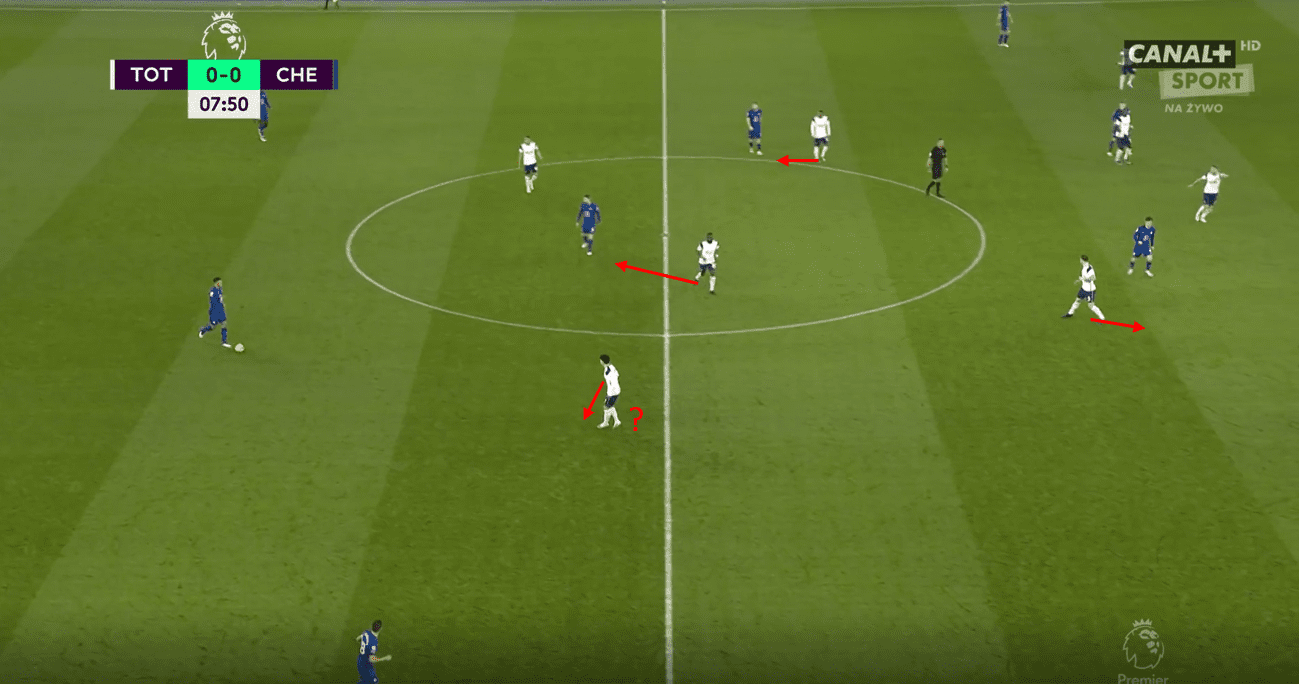

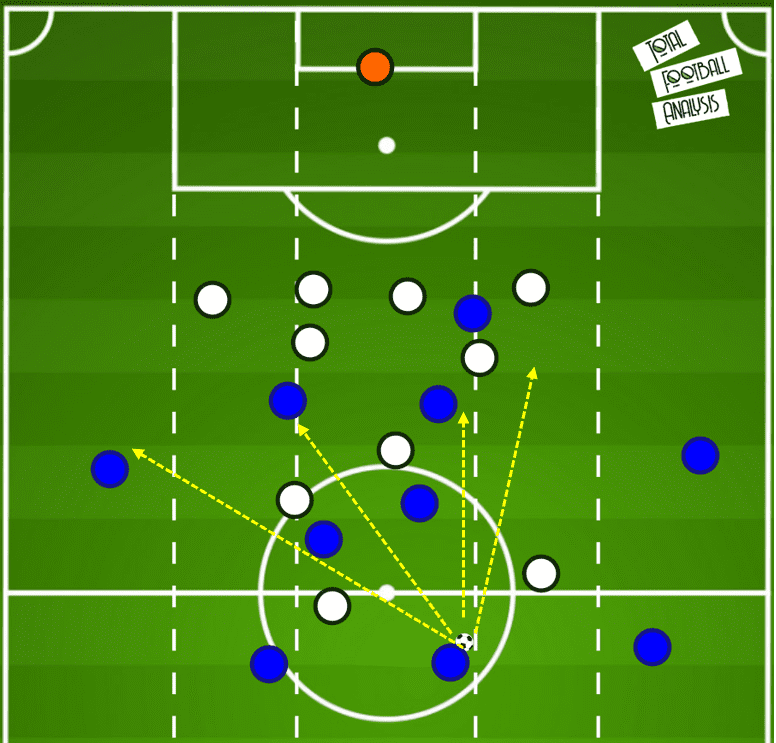

We can see here that both central players fill in the space between their centre back and full-back, and so the central space remains open for a diagonal ball, something which Chelsea then use.

Part of the reason for this poor shuffling in the first 25 minutes for Spurs was because they were allowing the ball to be possessed in the centre of the pitch, and so you can’t get too compact around space when the ball is in the centre as the player in possession has lots of passing angles. Even more passing angles can then be created if you mix in some more man oriented players. The image below highlights this concept, with the middle centre back unchallenged. If you restrict the centre and show the opposition wide, central midfielders shielding the back line can get more compact and shuffle earlier, because they don’t really have to worry about marking a player or accessible space due to players in front doing that for them. If you are showing a team into the centre, you have to cut more options, and therefore players find it more difficult to adjust to the position of the ball (e.g. shuffle across).

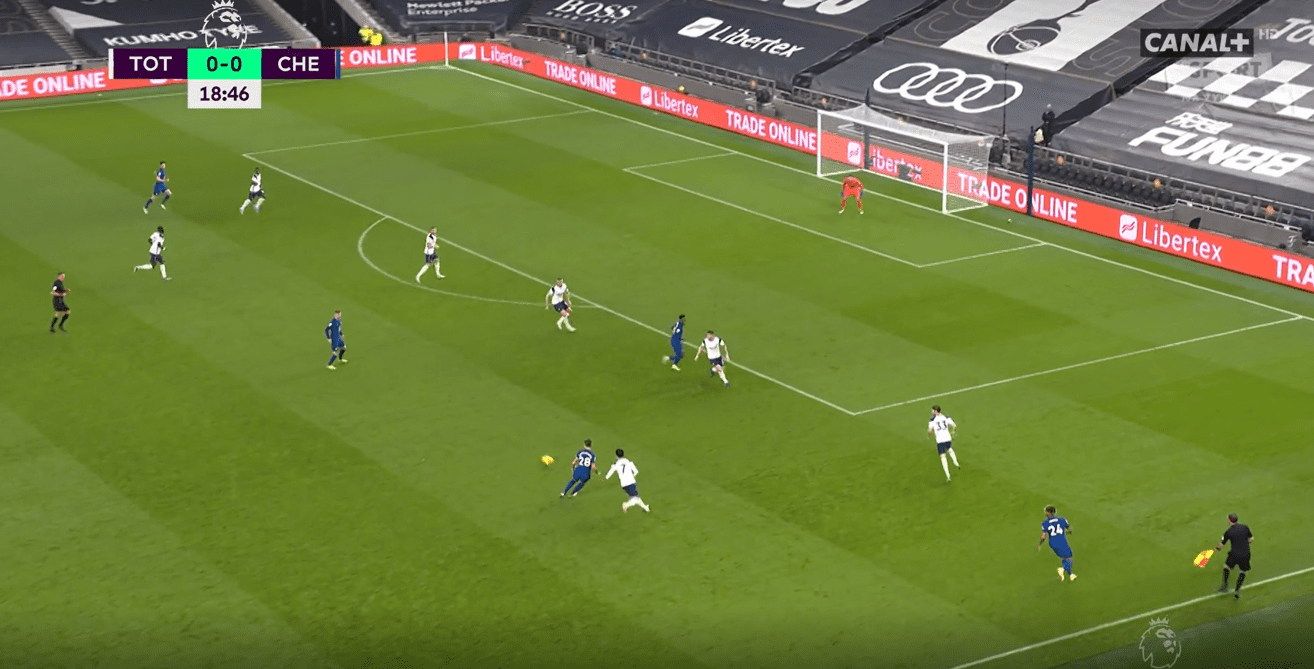

We can see an example here where Chelsea circulate the ball through the middle centre back, with Son not really cutting the wide lane here. Højbjerg has moved into the back line between full-back and centre-back, and because the ball has just been switched through the centre, Sissoko isn’t exactly compact with his midfield partner. The tens stay tight to the deeper Chelsea midfielders and so can be manipulated at different angles and heights, and so Chelsea have the option of a simple pass to get in behind and break the press, where they then have the opportunity to create momentary overloads on the back line.

Chelsea’s ball progression around the half-space

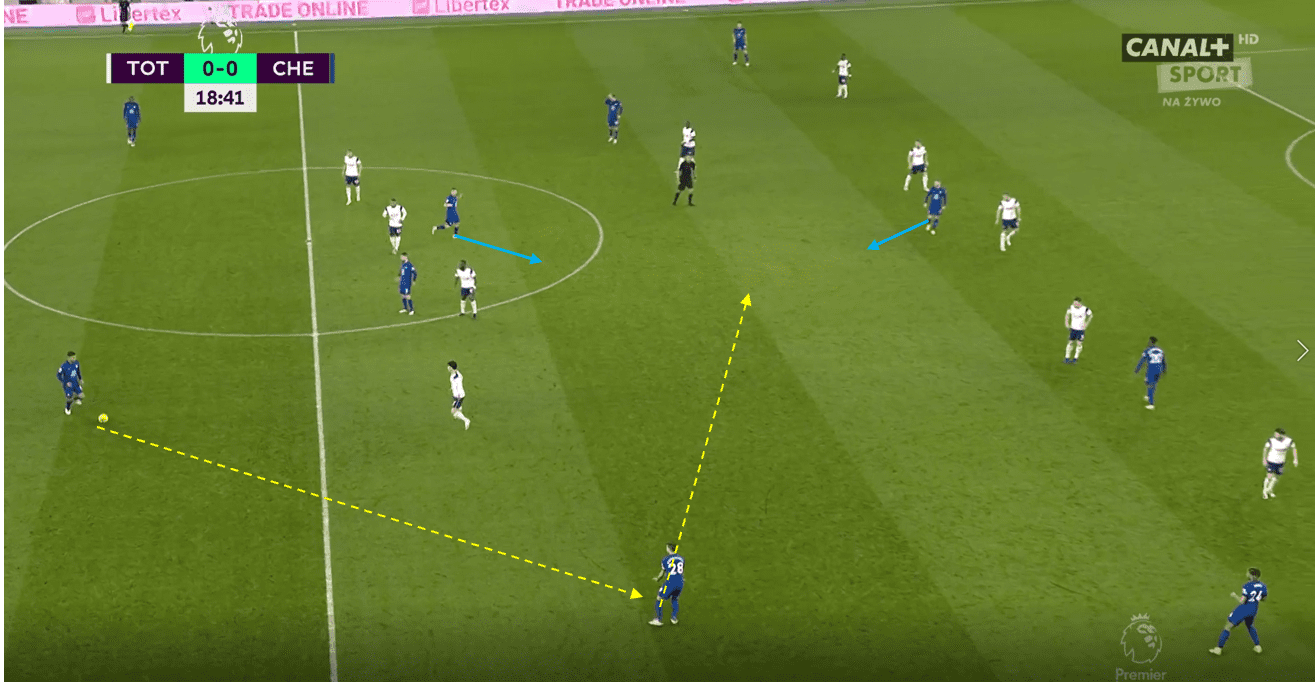

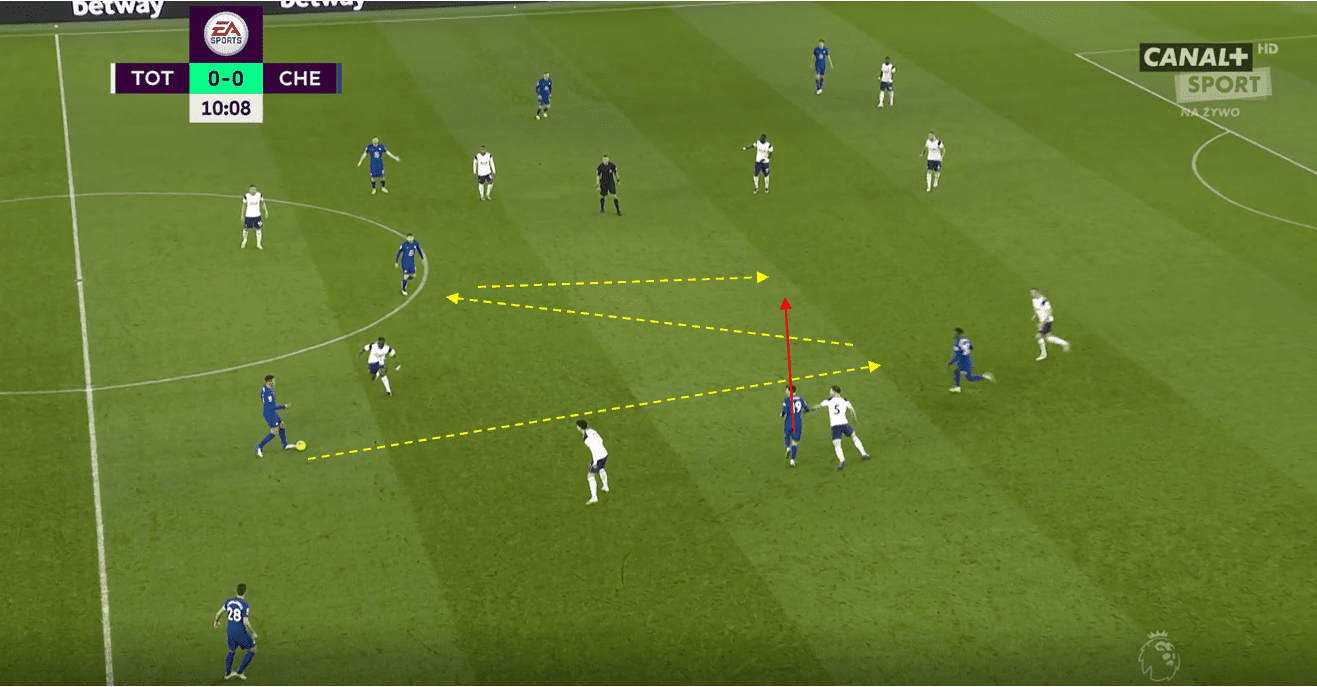

Chelsea’s combinations in and around the half-space allowed them to create space and progress the ball from these areas, but it was rarely due to a conventional overloading of the centre back in the half-space. Instead, Chelsea’s success came through exploiting the roles and orientations of the deeper Tottenham midfielders and centre backs. We can see this occurring below, where we see Tottenham in their usual structure allowing the ball to be played through the centre. Mason Mount initially occupies the centre back, and so Højbjerg moves to cover Hudson Odoi in the half-space. Mount then drops deeper to receive, and so Højbjerg temporarily becomes overloaded. He even gives the hand signal that every possession-based team wants to see.

Tottenham’s centre backs did not want to follow Chelsea’s dropping players, and so the defensive midfielder for Spurs was often caught moving back with a player and then having to push forward to press the receiving player. This kind of transfer marking between the midfielder and centre back can cause problems, mainly because that adjustment between marking a player going forward to then another player going in behind is difficult, therefore it opens up opportunities for the opposition to use these movements to go in behind.

Oppositely, it can lead to players having space in front of the defenders to play into. Here, Højbjerg stays in the half-space with Hudson-Odoi, leaving the centre to deal with the player dropping deeper. The centre back doesn’t want to do that, and so he drops off as well, giving Werner time on the ball to receive.

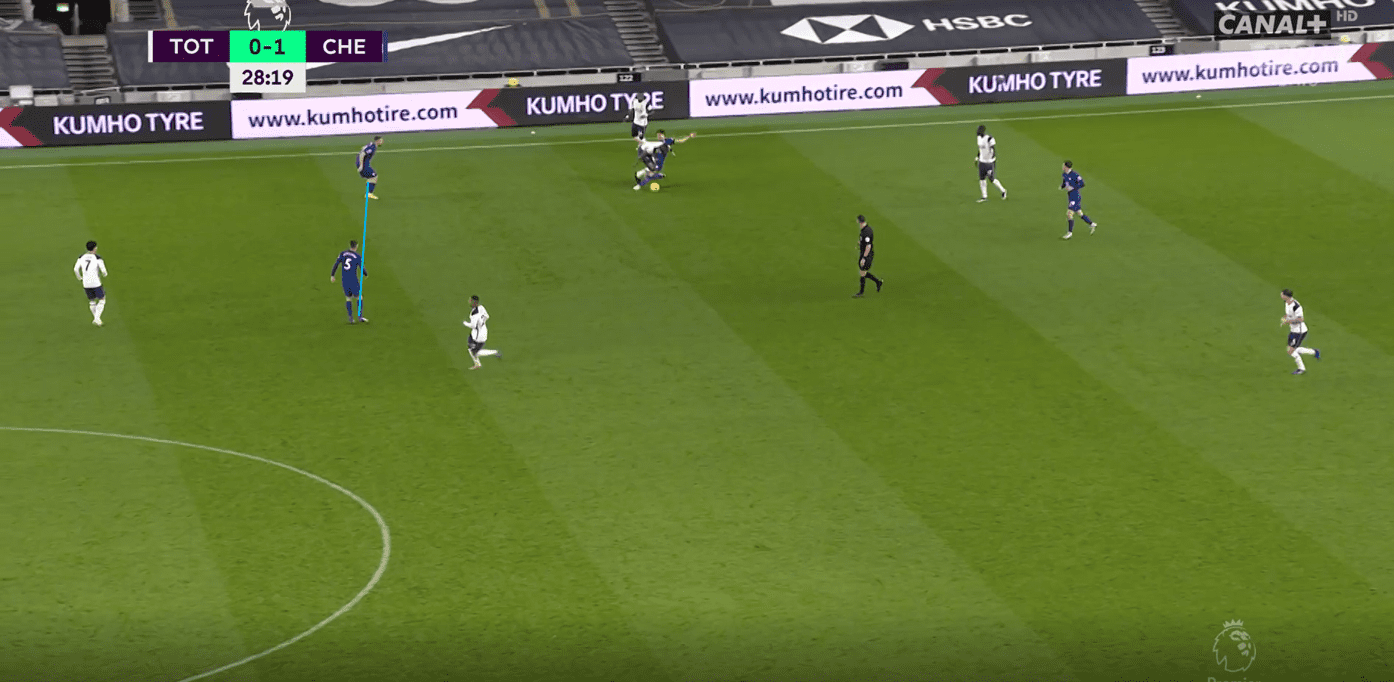

Chelsea use a very similar concept here in what was probably their best ‘play’ in the game from this point of view. We see Hudson Odoi and Mount occupy the centre back and midfielder again and are marked. The driving run by Silva opens up Jorginho, and so with the lane open, Silva can play the ball into Hudson Odoi who can play a simple pass back to Jorginho, who is now facing forward (third man combination). Mount makes a run forward to exploit the space left by the pressing centre back, and Højbjerg cannot adjust to match Mount’s run, so Chelsea progress well and create a 2v2 on the far side.

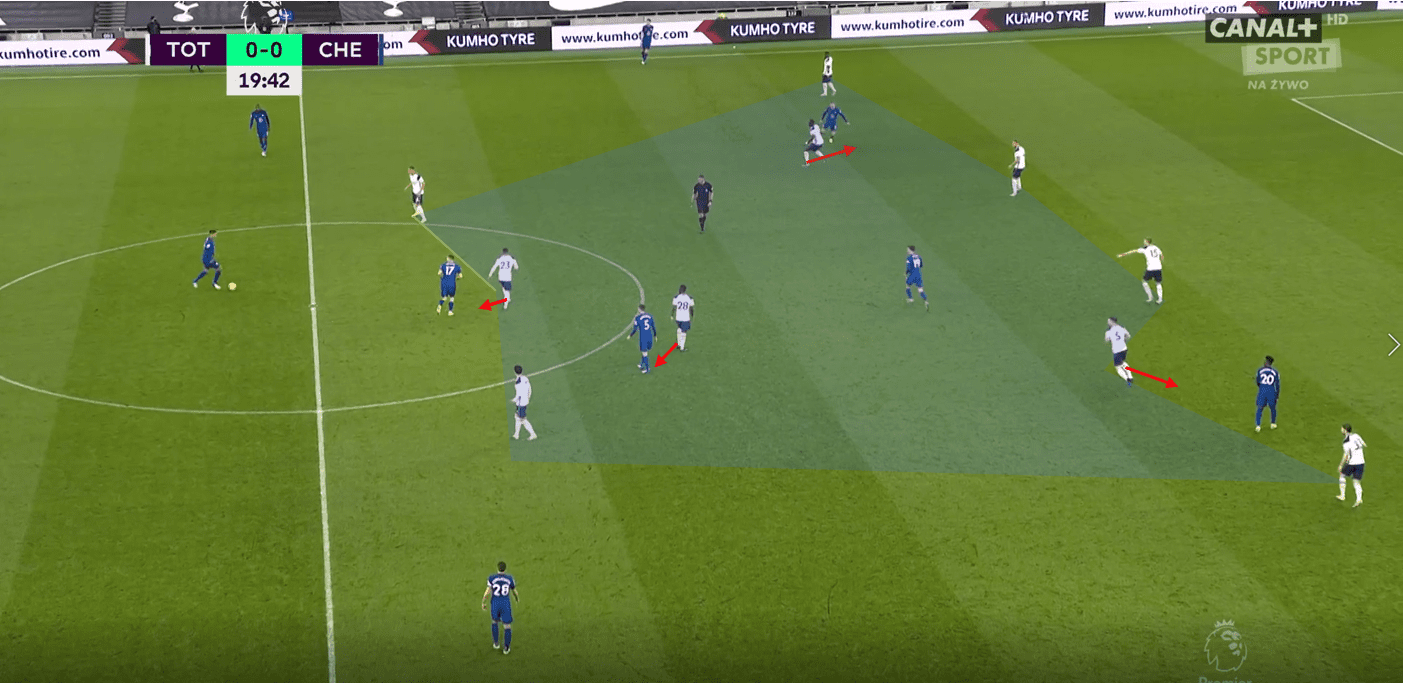

Here Chelsea manipulate Tottenham’s structure well by dropping both strikers into the half-space with the ball in the centre of the pitch and under no pressure. As mentioned earlier, because of this, both defensive midfielders drop back to cut off this pass, and so the central space becomes even more open, meaning Mount can now drop off and receive the ball. The man orientations higher up mean the passing lane into him is accessible also.

If players in the back line are occupied from in front, movements in behind can often be effective in progressing the ball, and we can see a potential opportunity here for Werner, although the pressure on the ball makes this difficult. Werner was able to get in behind to win the penalty to win Chelsea a penalty, however Chelsea didn’t even need to occupy the Tottenham defenders in front, which is one of the reasons Mourinho will have been so disappointed in conceding the goal.

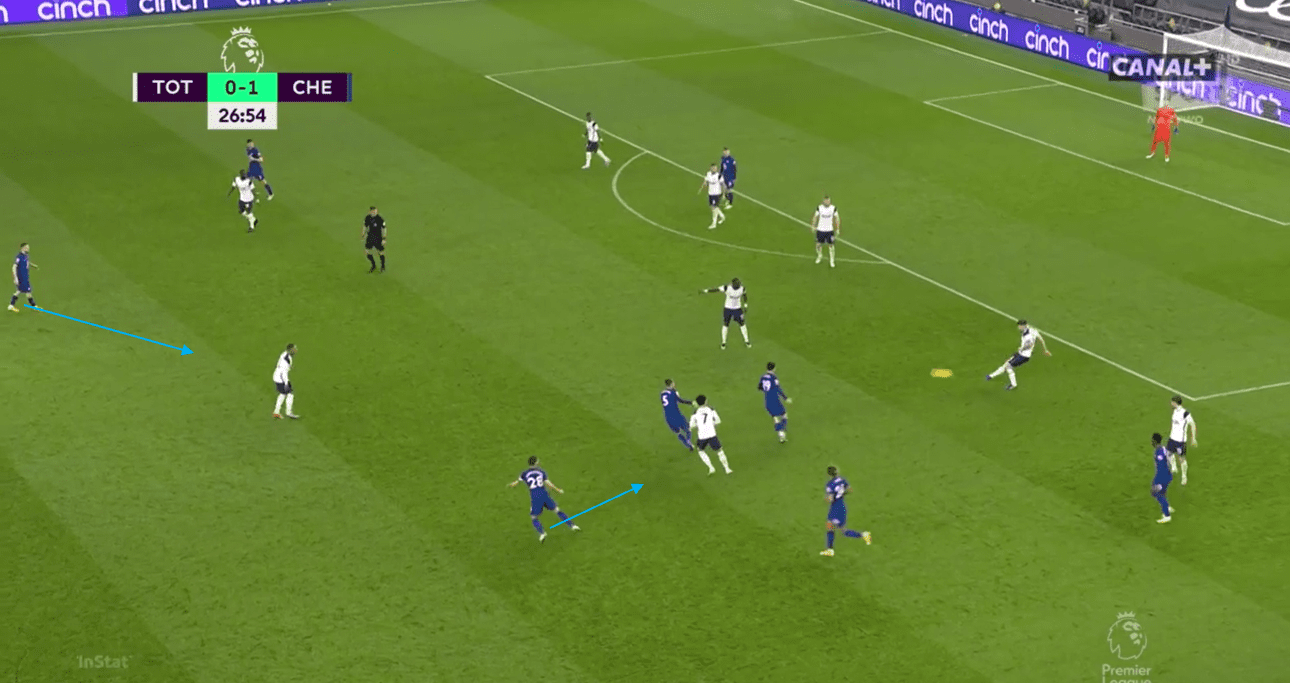

With players dropping off to then play in behind, the timing of runs in behind was also important to Chelsea, and this looked like an area they could improve on. We see an example here where Azpilicueta drives forward with the ball and Werner drops off to receive. Hudson Odoi makes an early movement in behind, and so by the time the ball is released by Azplicueta, he is already offside. It is the right idea by Hudson Odoi but not the best execution, which is to be expected given this is a new role.

We can see in the example above also that Son is dragged right the way back to maintain pressure on the ball, and so Tottenham’s counter-attacking opportunity greatly suffers as a result. Chelsea counter-pressed fairly well, particularly with their back line to limit Spurs’ counter-attacks, and their rest defence can be seen below. Chelsea’s deeper midfielders weren’t really involved in pushing forward to attack the play, and so they stayed close to the ball and in positions to cut off options or press forward if needed, as we can see below.

For Tottenham, their rest offense struggled but they also greatly missed Harry Kane, who can often make up for not having a great counter-attacking structure through his hold-up play and passing abilities. Due to their defensive structure, if Chelsea progressed midway into Spurs’ half and lost the ball, they would often have ten players behind the ball, as we can see below. Here Tottenham get a decent structure, with a 4-2-3-1 formed situationally. Chelsea lose the ball, and the nearest players counter-press.

Tottenham find Son who then lays the ball off, and Kovačić does not react to the nearby player who is free to receive. Azpilicueta has counter-pressed forward, something Chelsea’s centre backs seemed to have been instructed to do, but here he has no real impact due to Son laying the ball off, other than covering the immediate space Son could run into. Tottenham still only have one player up the pitch in Vinicius, and so despite this Chelsea can still recover and deal with the counter with a 2v1 in defence.

Chelsea didn’t allow many counter-attacks and their rest defence combined with Tottenham’s rest offense allowed them to limit Tottenham to just 0.47xG, with most of their shots later in the game and of low quality. I’d also add that Chelsea didn’t really lose the ball too often high up the pitch, and so this naturally helped to reduce the number of counters for Spurs. For example, in this game recorded 22 fewer losses in high areas compared to the Wolves match. Tottenham’s support play around direct passes was poor, and they clearly missed Kane’s aerial ability to play off, and so this was another problem for Spurs.

Tottenham adjustment

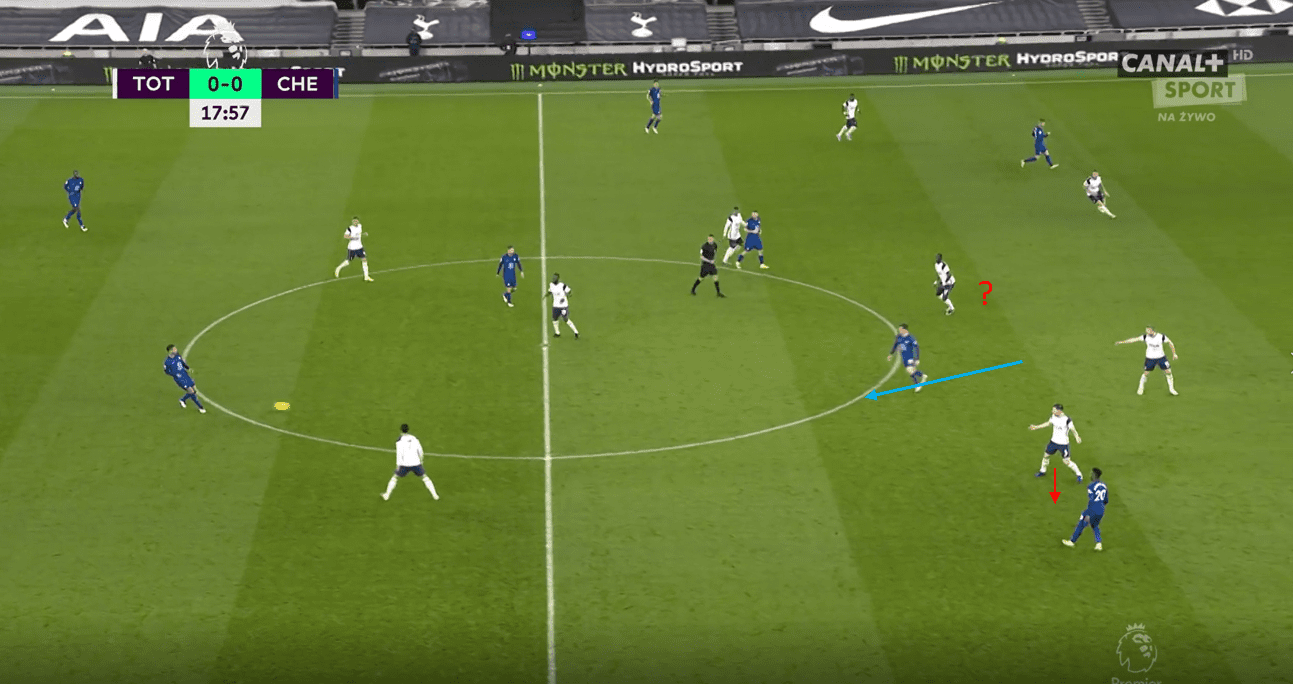

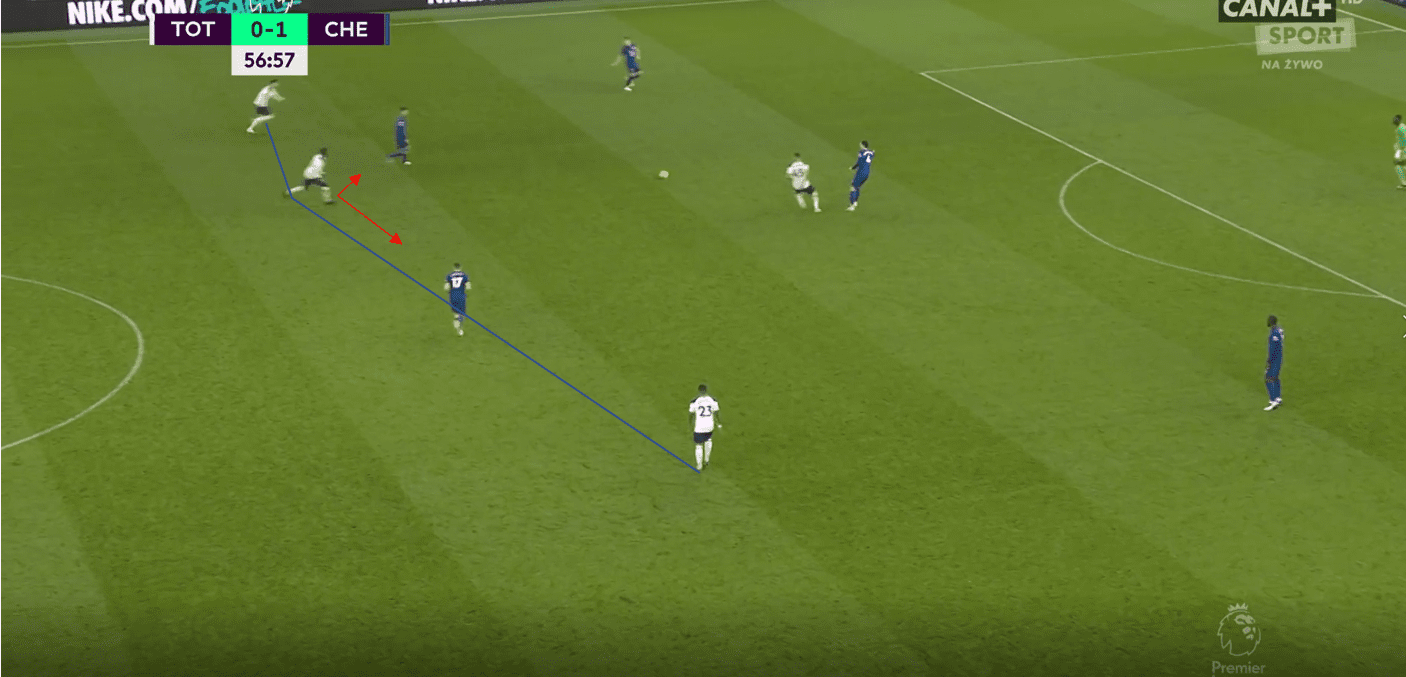

Being 1-0 down at half time, Tottenham adjusted their shape to resemble more of a 4-2-3-1, with the aim of this being to increase the pressure on the ball as they obviously needed it to score. The main problem this faced was the press resistance and in fact just presence of the double pivot, as they would often overload the pressing ten which meant Spurs’ press was broken. We can see an example below where the double pivot creates an overload, and Jorginho just receives the ball and dummies his way out of pressure brilliantly. Tottenham seemed to signal from the bench for the far side winger (number 23 Bergwijn in this case) to push across to cover the far pivot, but they couldn’t execute this.

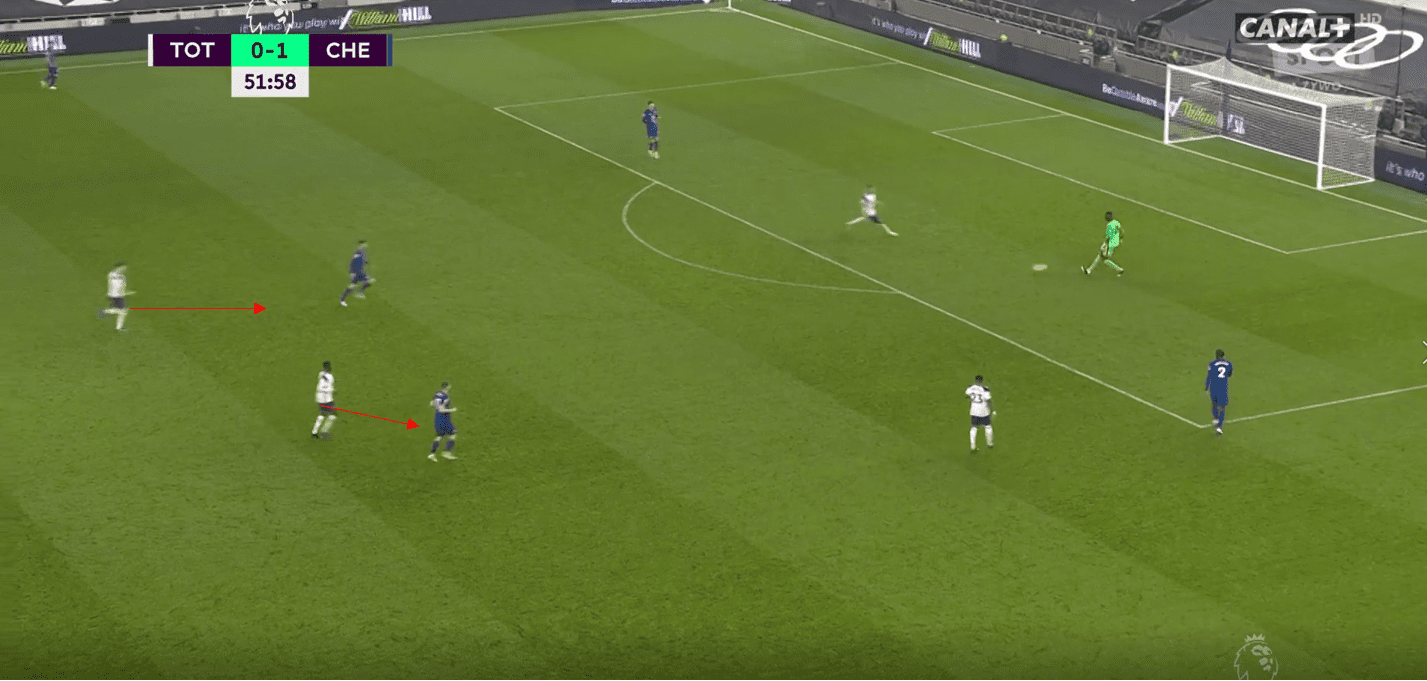

Situationally Tottenham would push a deeper central midfielder on to press higher, but this then obviously reduced their coverage in front of the defence. We can see an example here where a midfielder pushes on to press the double pivot, but Son is not in a position to press the wide centre back should he receive the ball.

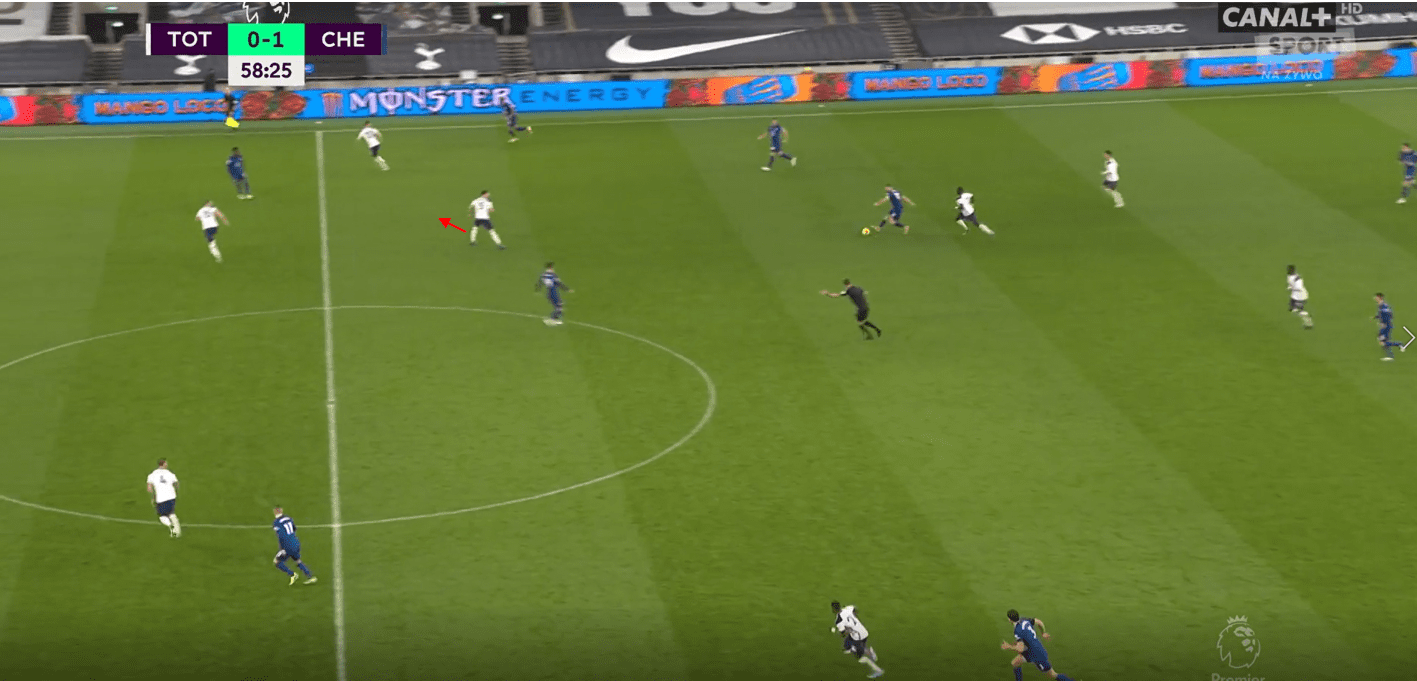

Here, Chelsea’s press resistance simply gets them through the press, as Kovačić receives and turns his marker to play forward. This leaves Tottenham with only one player covering the defence, and Højbjerg makes the strange decision to look to cover the half-space instead of the central Mount, and so Chelsea break and Werner gets a decent opportunity.

Conclusion

This analysis hasn’t touched on Tottenham’s offensive structure or tactics, but that could really be a larger piece in itself looking over the course of a few matches. They struggled in direct play and Chelsea’s 3-4-1-2 made it difficult for any central overloads to be created. If Kane had been available, I would guess they would look to get Kane up against Azpilicueta to launch counter-attacks behind that midfield through the second balls, but in this game they struggled to build past the Chelsea press.

In the end, it was a deserved win for Tuchel’s side, who again did not concede a goal and were able to create chances at the other end of the pitch. Tuchel’s system is stretching opposition presses as expected and creating overloads around the half-space, and if they continue to develop this system as is expected (based on Tuchel’s time at Dortmund and PSG), they will surely be a team to keep an eye on in the race for the top four this season. Pressure is starting to mount on Mourinho slightly after three defeats on the bounce, and the system just wasn’t effective in this game. He did adjust out of possession, but more work has to be done around offensive structure and breaking teams down when you can’t counter-attack them.

Comments