On the 23rd of March, it was announced that after just under a decade of working with the German men’s U15-U17 sides, Christian Wück would be given the German WNT role following the 2024 Olympics.

His German U17 side completed an impressive Euro and World Cup double this summer, defeating France in both finals. They won the World Cup for the first time in their history and their first European championship since 2009, when 16-year-old Mario Götze was playing.

The German WNT has consistently been at the forefront of women’s football for the past decade, reaching the quarter-final at seven of the past eight major international competitions and the final of the 2022 Euros against England. However, after a disappointing 2023 World Cup—where they failed to get out of a group containing Columbia, Morocco, and South Korea—they chose to move in a new direction with Wück.

In this tactical analysis, we will examine how Wück’s U17 side has played throughout its successful international campaigns. We will break down the tactics involved, both in possession and out, as well as the strengths and weaknesses within those. We will then also examine how Wück’s style of play might translate to the German WNT.

In Possession

With the ball, Wück’s side demonstrated the flexibility to play in a number of formations and adapt. One interesting aspect of Wück’s U17 side is that they were generally poor at sustaining possession for long periods, averaging 46.4% at the World Cup in Indonesia and 49.6% at the Euros in Hungary. It’s not necessarily what you would expect from the best side in both competitions. They had a passing rate of 10.5 passes per minute at the World Cup, second-worst only better than New Caledonia and at the Euros, they had the lowest passing rate of 9.8 passes per minute.

However, the team showed some ability and intention to play out from the back. The team often built up in a typical 4-3-3 shape, with Fayssal Harchaoui playing as the deep pivot. In this 4-3-3, the full-backs would create the angle and be the primary target as Germany looked to play around the opposition’s press. One problem that developed with this was the lack of penetration, which was reliant on players winning one-on-one and driving forwards. The central defenders did demonstrate the comfort of doing this. Still, midfielders Darvich and Osawe provided limited options to receive the ball between the lines, often forcing Germany to play long against the better teams.

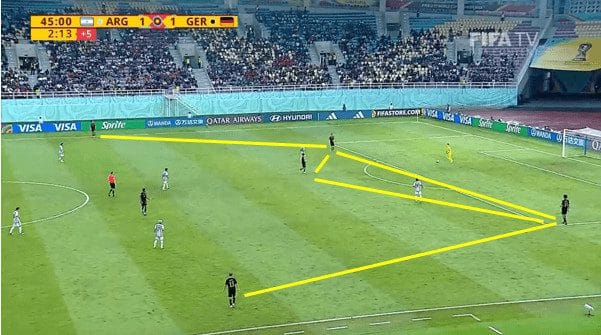

In this example, you have a single pivot of Harchaoui with the full-backs spread wide. The primary outlets for the defenders and goalkeeper are balls towards the full-backs.

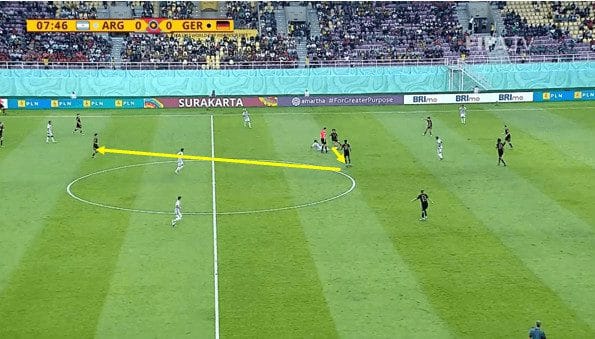

In this example, Germany operates with two pivots, with the two full-backs spread wide. Argentina tried to press in a narrow shape, forcing Germany to play around the press towards the full-backs. Germany had limited success with this.

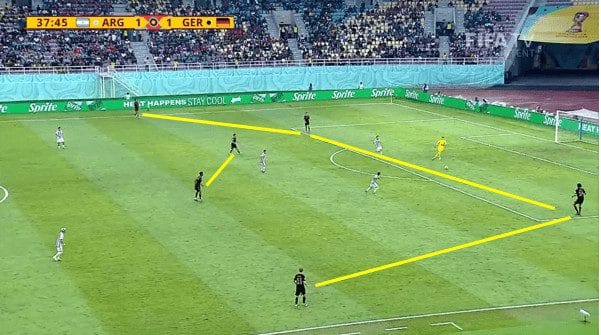

Alternatively, for example, against France in the World Cup final, they started with a back three, with Harchaoui dropping deeper to pick up the ball so he could drive forwards with the ball. A major problem with building up in the back three was the disconnect that was created in the midfield, with Winners Osawe being left isolated in the midfield area. As a team, Germany identified this problem, and initially, Noah Darvich, who was typically playing as the number ten, dropped deeper to act as that bridge; however, after a while, they switched things up entirely, creating a double pivot system with Osawe alongside Harchaoui.

Above, you can see Germany building out the back using a back three shape, with Harchaoui becoming a third centre back. You will notice how isolated Osawe is in the midfield, playing against four French players. This limited Germany’s ability to play penetrating passes through the opposition’s shape.

In the final third, Germany looked to play around the opposition shape and get balls into the box so Max Moerstadt could head in the box. He used his size and strength to win the ball, averaging 4.09 successful aerial duels per 90. However, one limitation to the side was the lack of midfield, which meant that if they wanted to switch the point of attack, they would have to play all the way back to the defence. They created a wide box shape in the final third with a big gap in the middle.

Here, you can see the box shape with a front four created and then a full-back-winger partnership on both wings. You can see the big gap in the middle, though, which forces switches of play to go all the way to the backline.

Out of possession

Last summer, in relentlessly humid conditions in Thailand, Germany established itself as a pressing side. Operating a player-to-player system in the midfield, which afforded opponents no team and space, they were able to make regular high regains, which enabled them to launch dangerous counterattacks.

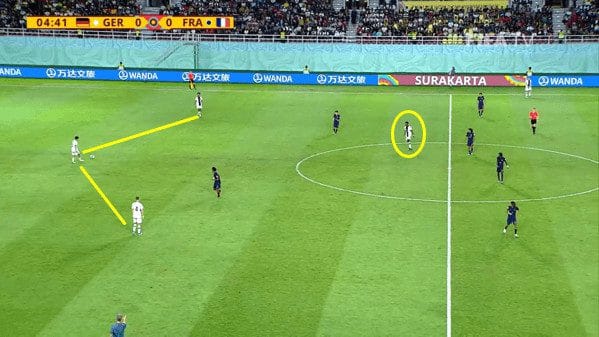

Here, you can see the player-marking pressing system utilised by Wück’s side. The midfielders all tightly mark their opponents, while the wingers are engaged by their opponents but remain narrow to prevent the opposition from playing through the middle and force them wide.

As a team, they averaged a PPDA of 9.73 at the World Cup and 6.93 at the Euros, which puts them thirteenth in the competition, so they are around the middle of the pack. However, the humid conditions likely played a factor in this, and the adjustment to playing a less intense brand of football enabled them to have success.

There are flaws in a player-to-player system, and this often came down to the wide channels. When full-backs stepped up to be aggressive, they left space behind them to attack. Opposition attackers were able to find these spaces regularly, and players like Echeverri, who recently signed for Manchester City, were able to make them pay.

Here, you can see one of the problems with this idea: Echeverri getting in behind right-back Eric da Silva Moreira. Then, what you also see is the disconnect this can cause in the defensive shape. The space opening up in the midfield enables Valentino Acuña to find space, isolate the German defender two against one, and create the goal, which puts Argentina 2-1 up in the game.

In deep shape, they operated a similar player-to-player idea, with the mobile midfielder Osawe vital to the side’s ability to regain the ball with regularity. At 11.46, Osawe completed the third most defensive duels per 90 of anybody in the World Cup. The issue again lay with the side being pulled out of position, with midfielders being pulled narrow. This could leave gaps that could potentially be exploited.

Here, you can see the midfield playing in a straight line, which leaves space in the midfield, which, for example, a Spain side with lots of intelligent technical midfielders such as Aitani Bonmati and Jenni Hermoso could exploit.

Transitions

Transitions were vital to the German U17’s success over the past year. With the side operating a high and aggressive pressing shape, they were able to win the ball back regularly. After winning the ball back, they looked to drive forward at pace with four attackers, often the two wingers, Paris Brunner on the left and either Charles Hermann or Bilal Yalcinkaya on the right flank. Max Moerstedt then supported the two wingers through the middle and Darvich.

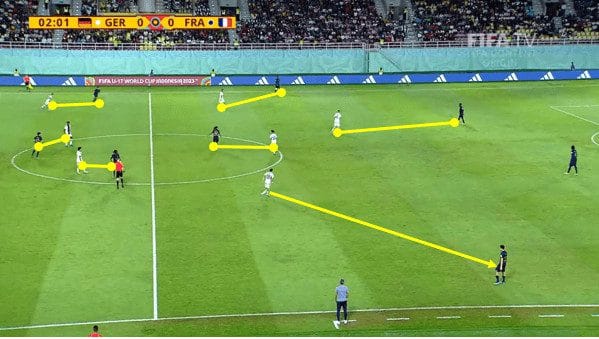

This created a front four that would create numerical superiority on the counter as the opposition was caught out of shape. In addition to this, all four players are goal-scoring threats and demonstrate the intelligence to move and rotate to best exploit the space. Another key player in transition was Osawe, whose ability to regain the ball and drive forwards enabled the team to consistently develop counterattacks.

Here, you can see Harchaoui winning the ball back in the midfield. The ball falls to Osawe, who plays a positive ball towards Darvich, who is able to drive forward on the ball. What you can see is the four against three they are able to create. The wingers play outside the opposition’s shape to keep them spread out. Darvich executes a pass to Brunner, who is able to win his one-on-one and score the opening goal of the game.

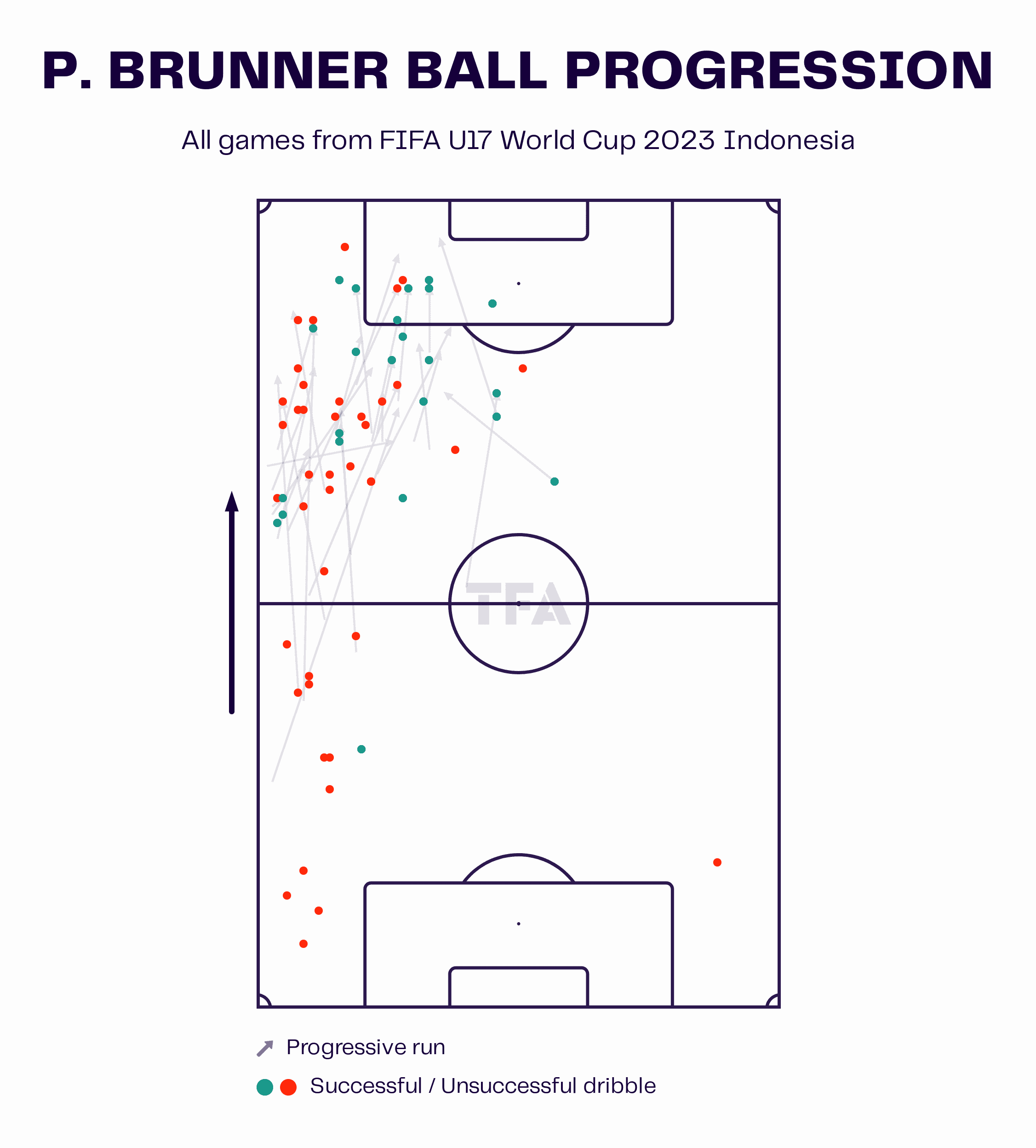

The German side then had several excellent ball carriers to support its ability to regain the ball high up the field. The German side completed the second most progressive runs per 90 in both competitions (World Cup and Euros), with 21.13 and 21.49, only behind England and the Netherlands, respectively.

A large part of this success was down to the quality of Paris Brunner, who not only finished as the World Cup’s second-top scorer but also completed the second-highest progressive runs, with 32, only behind England’s Joel Ndala. This enabled Germany to swiftly progress the ball in transition, particularly as Brunner was supported by Darvich and Hennig, who were also leaders in progressive runs.

How the German WNT could look?

The current German WNT, currently under interim head coach Horst Hrubesch, qualified for the Nations League semi-finals, eventually falling to Spain and finishing in third. Under Hrubesch, they have looked to play with a 4-2-3-1 shape, with the side looking to continue in a similar format to under previous manager Martina Voss-Tecklenburg.

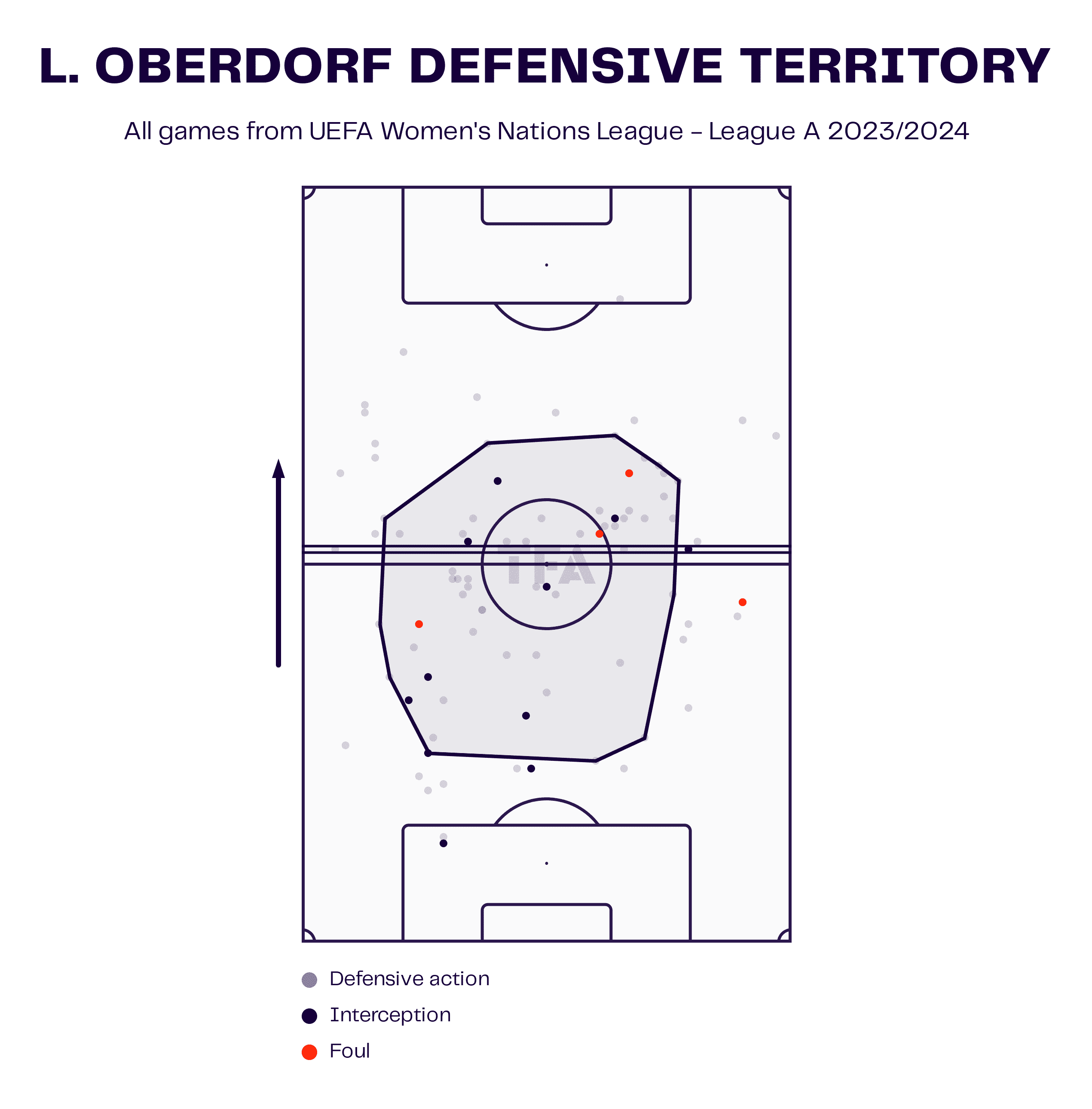

At the most recent Nations League, Germany had the second-best PPDA and the second-highest challenge intensity (Duels, tackles and interceptions per minute of opponent possession) in the competition, only behind eventual winners Spain. This shows how the team can be a high-intensity pressing side which would support Wück’s principles demonstrated in his U17 side. With Wück, they could look to play more player-to-player in midfield with a player like Oberdorf, whose ability to read the game and prevent danger from developing is vital to their success in a more player-oriented system.

Although her defensive statistics averaged 8.64 possession-adjusted interceptions per 90 in the Nations League this term, which puts her in the top twenty, it’s her ability to prevent danger from occurring and divert opposition attacks with good pressing angles that makes her such an important player.

Perhaps the bigger question is who Wück would pair alongside Oberdorf. With the German U17 side, they partnered the mobile, rangy ball recovery specialist in Osawe with the more technical Harchaoui. However, although they would need to be technical, they would need to be adept at ball recoveries, particularly if Wück decides to stick with his player-marking system in midfield.

Potentially somebody like Dzsenifer Marozsán, who is a more experienced option but remains a top ten midfielder in the French Feminine Division 1 in terms of possession adjusted(PAdj) interceptions at 7.57. Alternatively, a player who could be additionally well suited to this high-intensity role is Sjoeke Nüsken, currently playing for Chelsea, who has averaged 7.1 PAdj interceptions per 90 and 5.9 defensive duels per 90, which puts her amongst the top midfielder performers in the WSL this season. In addition, Nüsken finished second in the Frauen Bundesliga last season for progressive passes per 90 with 11.85, which could complement Oberdorf nicely.

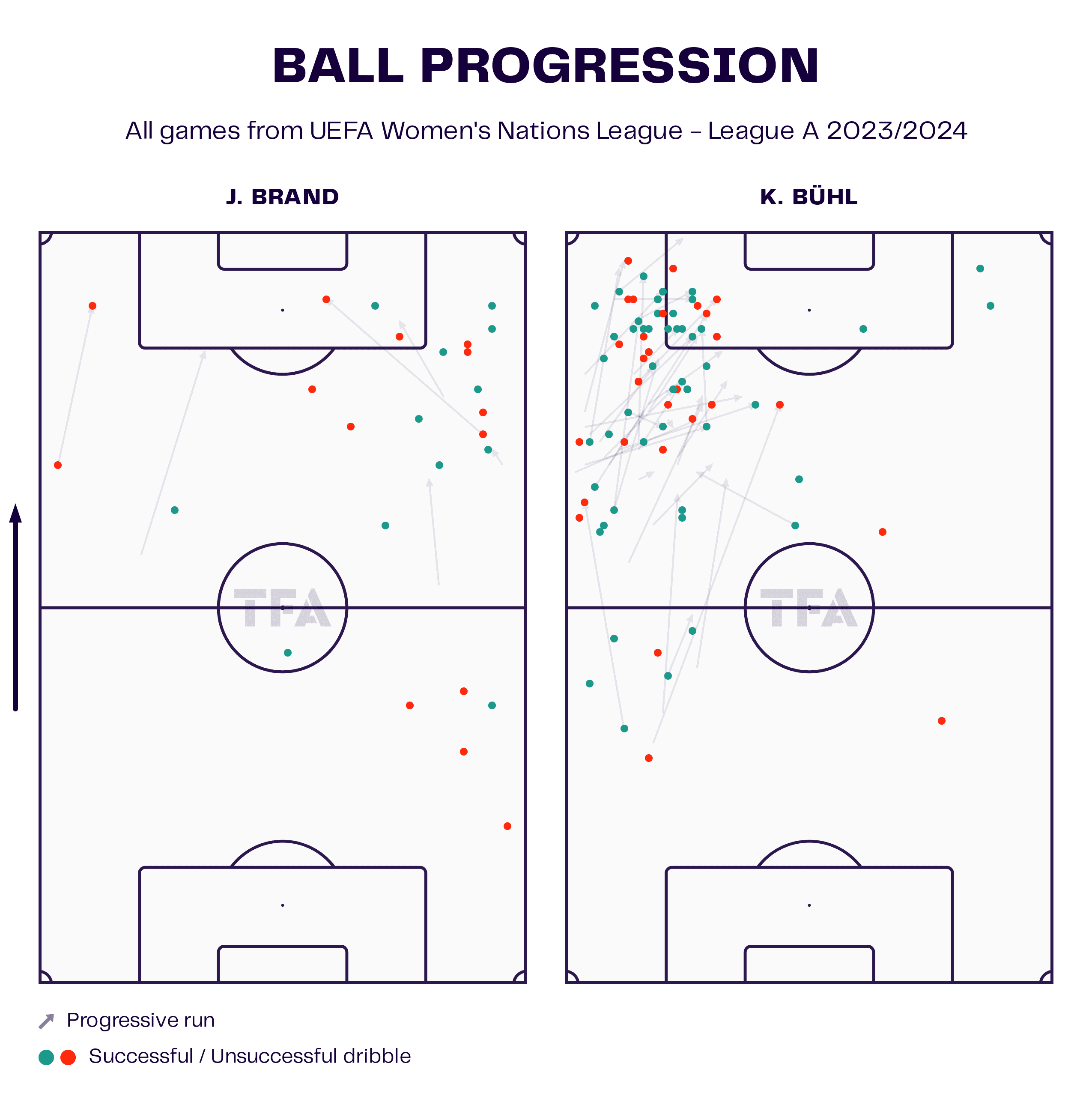

Then another critical area to look at would be who that front four for Germany could become, with the German U17 side deploying an excellent ball carrier in Brunner. German WNT could use high-end ball carriers Jule Brand and Klara Bühl, who have already played several minutes for the German national team. Brand averaged 5.03 progressive runs per 90 and 12.14 completed dribbles per 90 this season, while Bühl averaged 5.68 progressive runs and 12.13 dribbles per 90 in the past Nations League campaign. These two players could be integral assets moving forward for the German WNT.

The other key aspect to their success was the role of the number ten Darvich and his ability to link the midfield to the attack as well as create chances for her side. A player who could do this effectively is Svenja Huth who, although is ageing at 33 and is likely on her last cycle, she can play this role effectively having made a recent transition to a more central role for her club side Wolfsburg from the right wing, which she has played for the majority of her career. Huth has always been a high-end dribbler, and she still averages 3.15 progressive runs per 90 despite this recent position switch. Combining this with her ability to create chances, averaging 0.56 xA per 90, from central positions, she could play an essential role in the number ten role.

Some potential future options in the number ten role are Frankfurt’s Laura Freigang and Sydney Lohmann. Lohmann averaged 3.04 progressive runs and 5.14 dribbles per 90 throughout Bayern’s 2023/24 UWCL campaign, while Freigang only managed 0.56 progressive runs and 1.88 dribbles per 90. In part, this was down to different roles within their sides. However, it may also suggest that Lohmann would be a better fit for Wück stylistically. However, despite being a better runner, Lohmann only created 0.19 combined xG and xA per 90, while Freigang created 0.42 xG and xA per 90, so potentially, Freigang could be a more dangerous threat in terms of chance creations for her side.

Conclusion

This is an exciting time for the German WNT, with Wück taking over from Hrubesch after the Olympic games. Having led the German U17 to success at both the Euros and World Cup, he has demonstrated the ability to create a team that can succeed internationally.

With such an exciting young German side, several players just entering their peak, Wück could be precisely what they need to take them to the next level and achieve international success.

Comments