When in possession and looking to play forward, breaking the lines of an opposition’s defensive shape can be the most difficult process. It can often lead to turnovers of possession, and teams will frequently look to attempt to do so when there isn’t the space or opportunity to play these passes.

Forcing these passes often leads to unsuccessful attempts to break lines. However, we don’t just have to wait for the right moment to play forward — we have to use our possession to manipulate the opponents’ shape and create the space for us to play forward.

Second to this, once we have successfully broken a line with a forward pass, we need to ensure there is support around the ball in order to secure possession and not leave the receiver isolated. We also need to ensure there are also forward pass options once more, giving us an outlet and not forcing us to hold onto the ball in a pressured area.

The set of practices suggested in this coaching tactical analysis looks to provide a framework to explore breaking lines with forward passes, providing opportunities for players to recognise passing patterns as well as understand how movement and a change of tempo in their possession play can create chances to break lines. This training analysis suggests these practices would support a team whose tactics look to carve teams open through the central channel, but in general, learning how to break lines is something that all players can benefit from.

Part 1

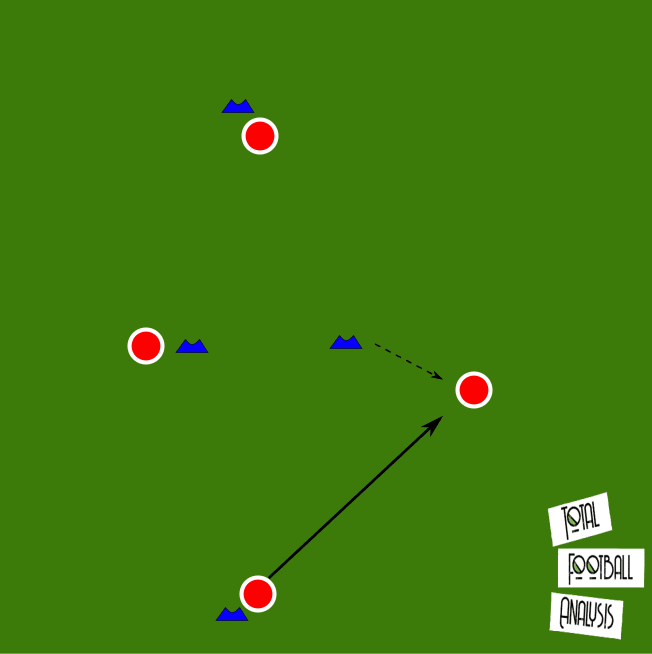

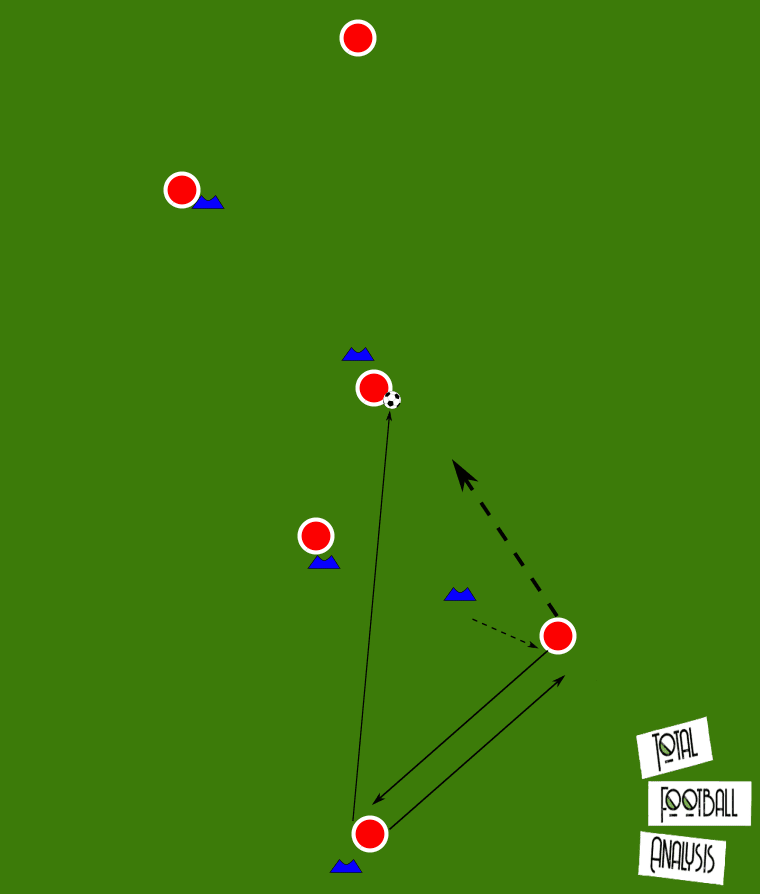

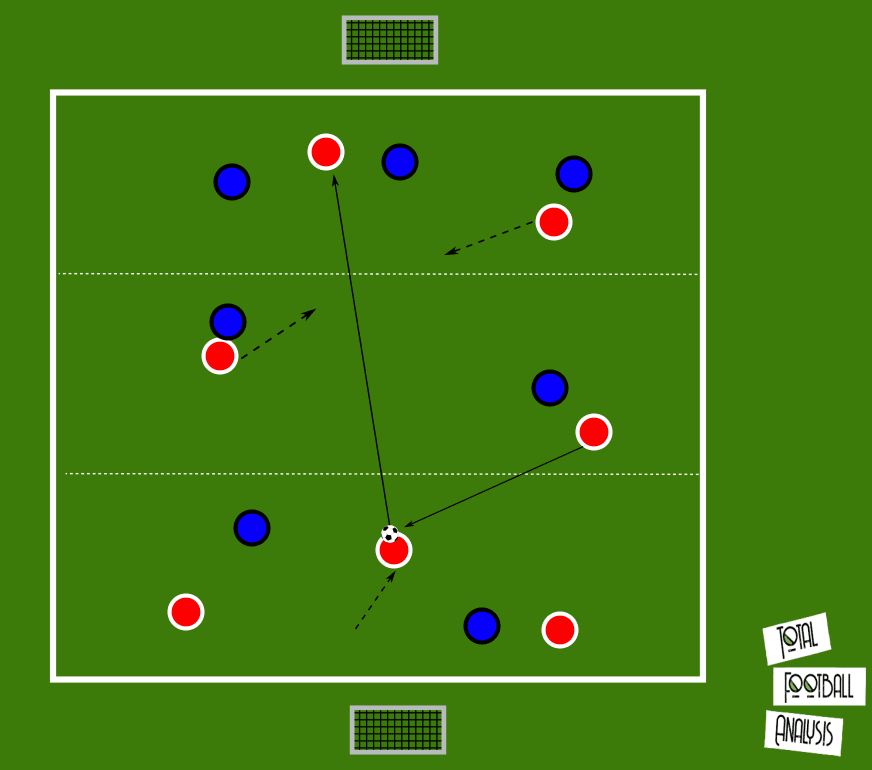

The first practice is a simple pattern of play that should introduce the basic principles of creating space to break lines whilst allowing the players to get into a pattern for automation when it comes to recognising the opportunity to break a line with a pass.

Starting with a diamond pattern, the players are asked to play to the right. The central player receiving needs to recognise that the space is too narrow centrally to play directly end to end right now, so instead they drop wide at an angle to initially receive the ball.

Now they are in a position where, once in possession, they would draw a defender out wide with them and can lay the ball back to the original player. It is important this player doesn’t step too far forward to receive the wall-pass for they reduce their own space by doing so.

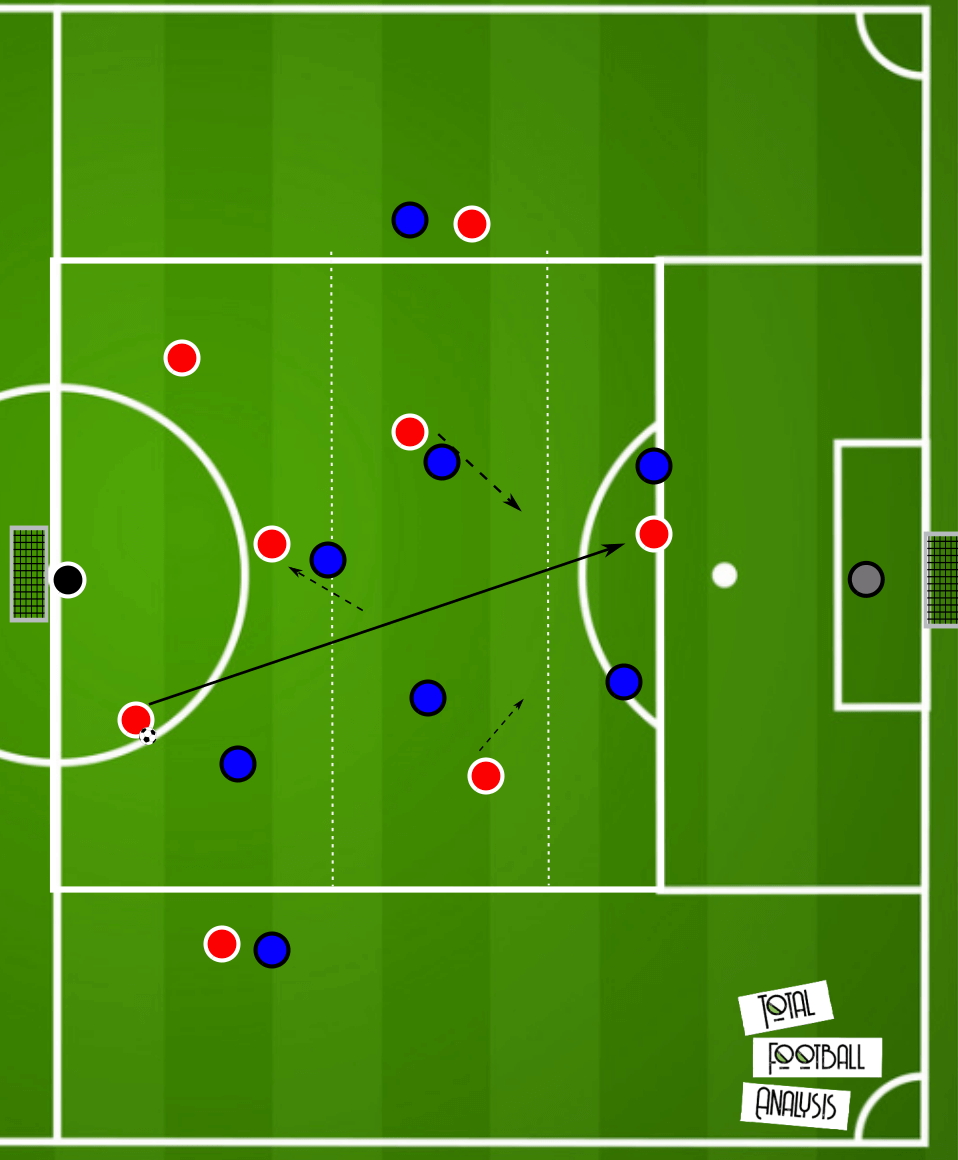

Once the wall pass has been completed, and the central space has now been created, this line breaking pass is able to be played. We can see this occurring in the following image.

This is a really basic pattern and players should be able to pick this up quickly, to instantly begin moving the ball at free will. Of course, once the ball has been played to the far end, the pattern continues, still with the player passing to their right — now the pattern comes back on itself.

These patterns need a minimum of five players to run, with the passer also rotating to their right once they have played the pass. Of course, it can be reversed with passes to the left as well.

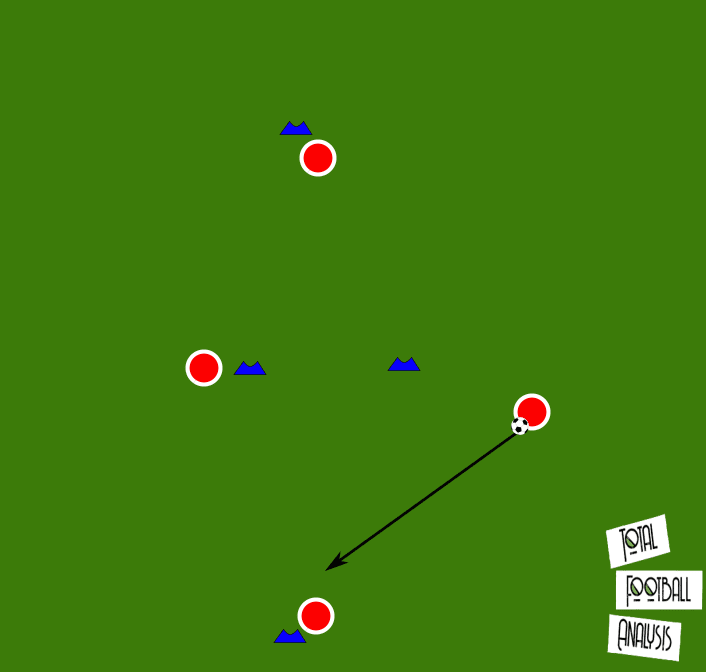

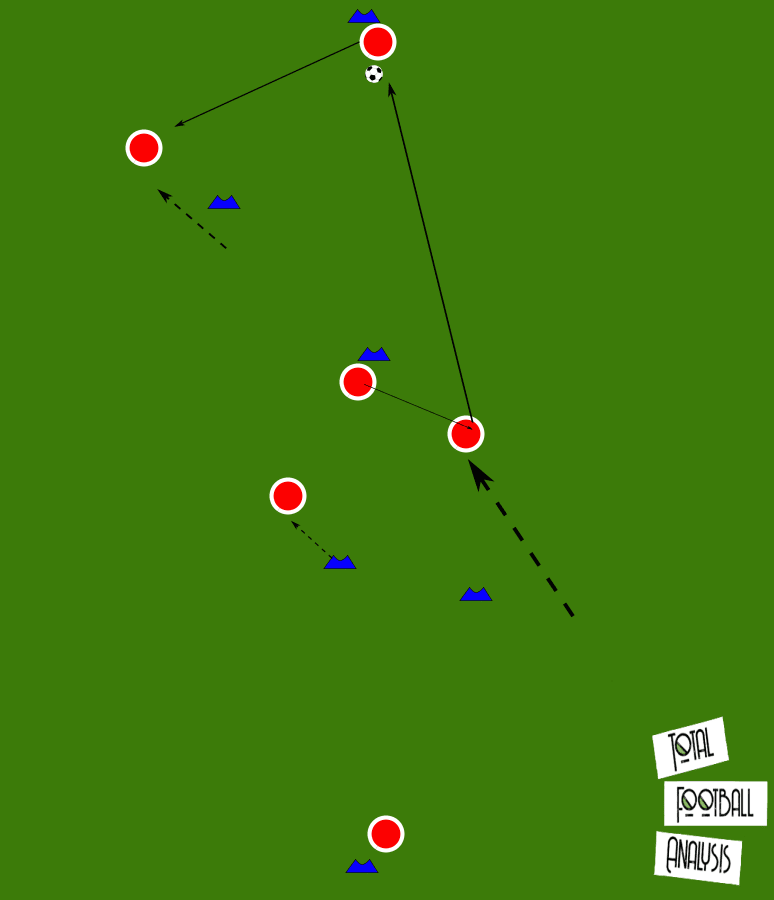

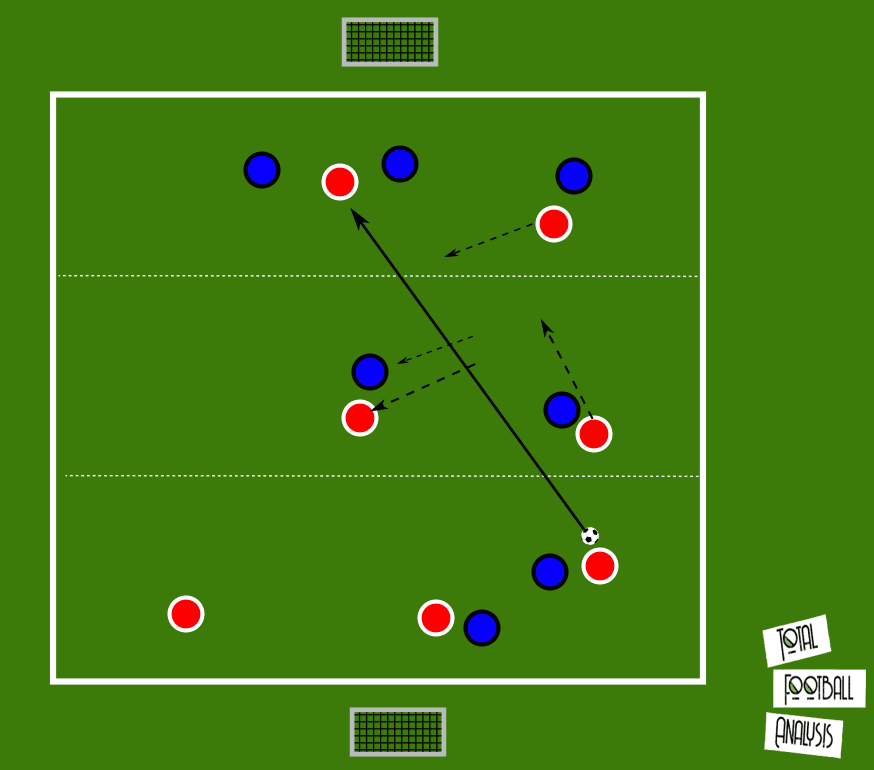

Building on this pattern we can now further introduce the idea of continuing to support the line-breaking pass and look for a forward pass option once more. For more developed teams, this topic can link with varying the tempo of play based on the ball’s location, e.g speeding up play once the ball gets into the midfield.

The pattern begins the same with the same initial movement from the wide player, then the line-breaking pass. We can see this in the following image. However, the wide player then moves forward to support the line breaking pass.

They now get on the ball and look to immediately play forward into the far player, before the pattern repeats itself coming the other way. These passes should all be played first-time, but if not possible, at the very least, the two players combining to play the last forward pass should seek to play first time, for they represent midfielders in this situation who will most definitely be under pressure.

Players should be encouraged to play game-realistic, firm passes, and use the cones as prompts rather than strict places for them to stand in. All players should really be on the move before receiving the pass, as they would in a game situation.

Part 2

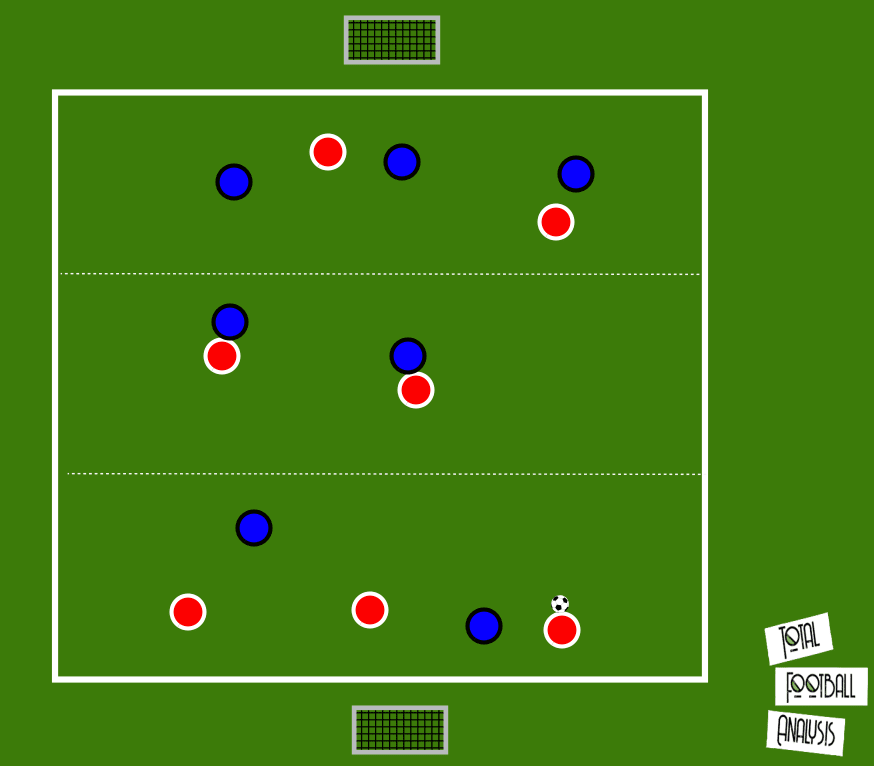

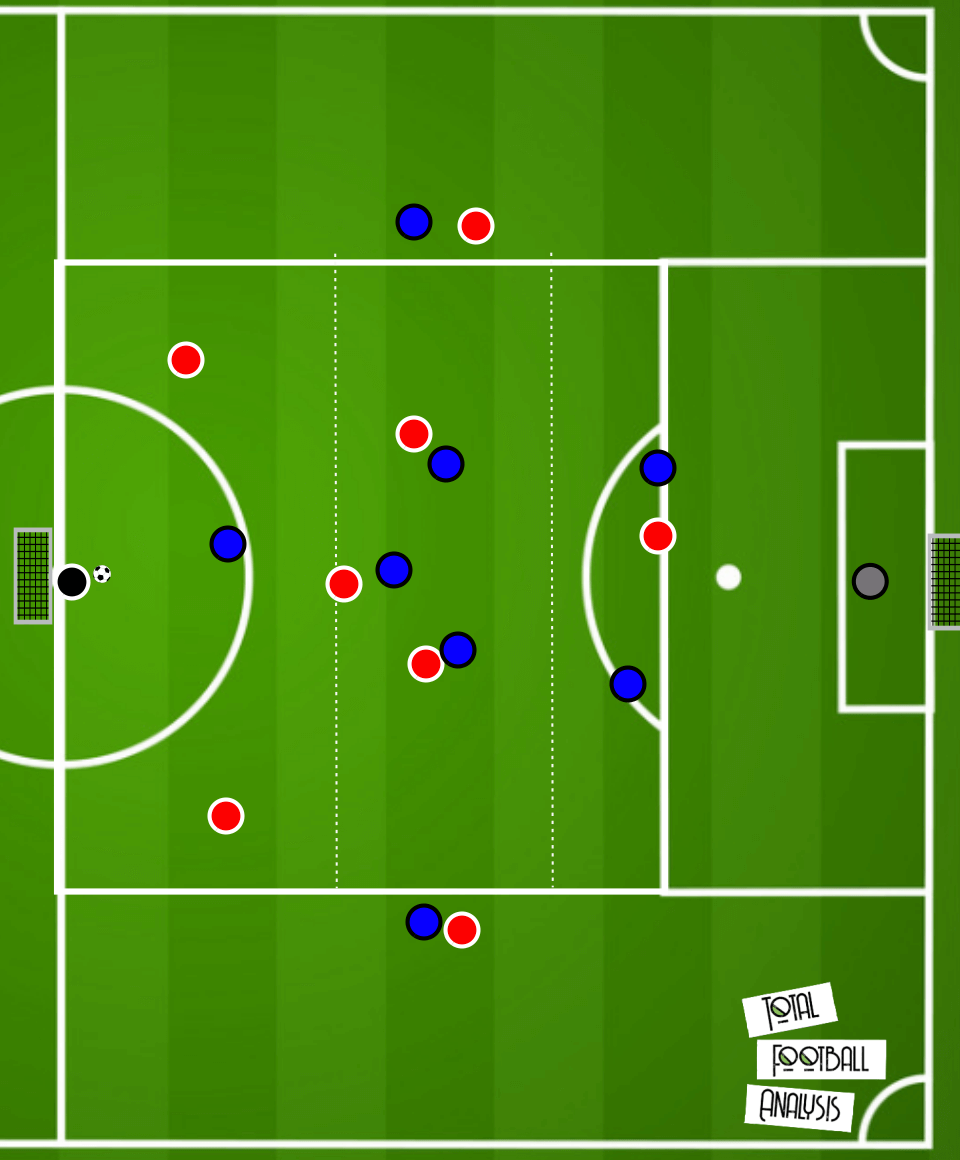

Following on from this pass pattern, we will look to get the players into a contested situation where they can have the freedom to explore line-breaking passes. In this example, a goal is at either end, but a coach could place more goals at either end if they want to increase success. These goals should be placed five yards away from the end lines to ensure defenders can’t simply stand in front of the goals and block them.

This practice has an overload in the defensive third for the in-possession team, an even pairing in the central third, and an underload in the attacking third. Thus this allows the possession team time to combine and build play in their defensive third, waiting for the right opportunity to play forward. Without overloads in the central third and final third, they, of course, need to recognise they must play quicker. Incentives for line breaking passes can be put in. For example, should a player in the defensive third play straight into the final third with a pass and the team score, this can be worth double.

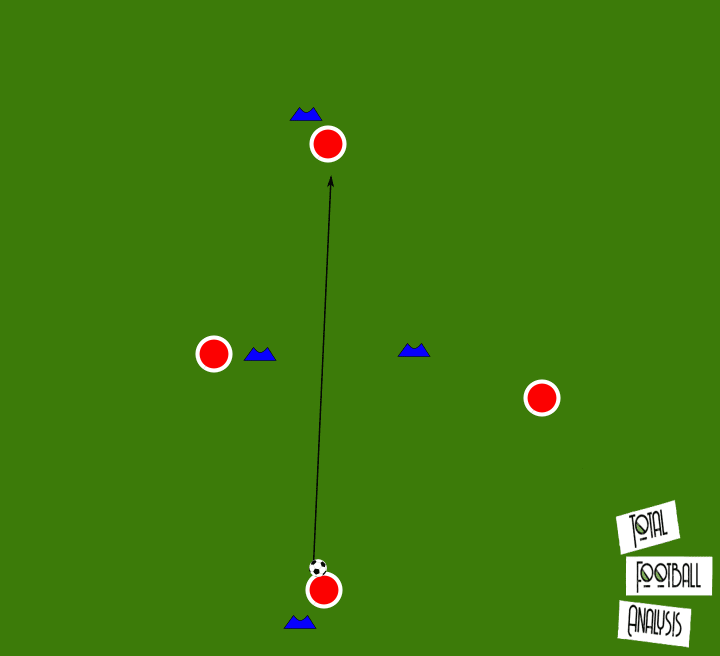

We are initially looking for the midfielders to recognise the opportunity to use the previous pass pattern. Can they give an angle, drawing their marker out wide?

They can play a simple one-two pass and lay the ball back, or even better they may look for the third-man pass, providing the space for their team to play through the space in the midfield that they have created.

As soon as this pass occurs, we want to ensure there is attacking support around the ball. The other attacker in the final third might look to drop short, but also might run in behind, depending on the location of their partner, whilst the other midfielder should absolutely look to support this pass by offering a short pass option just south of the receiving forward.

However, the midfielders may look to explore their movement and may recognise that there are times when they don’t even need to touch the ball, but their movement into a different space can be enough to create the room for a line-breaking pass.

We can see this pattern occurring in the following image, again with players immediately supporting the pass. As a coach, we should be looking for this to occur naturally where possible, before then highlighting this to the group, showing them their success through this approach as well.

Of course, the game runs both ways, with the blues attacking the other end once in possession themselves. Again, the thirds can be used more as guidelines for team shape, but without offsides, teams should naturally keep this 3-2-2 shape.

Part 3

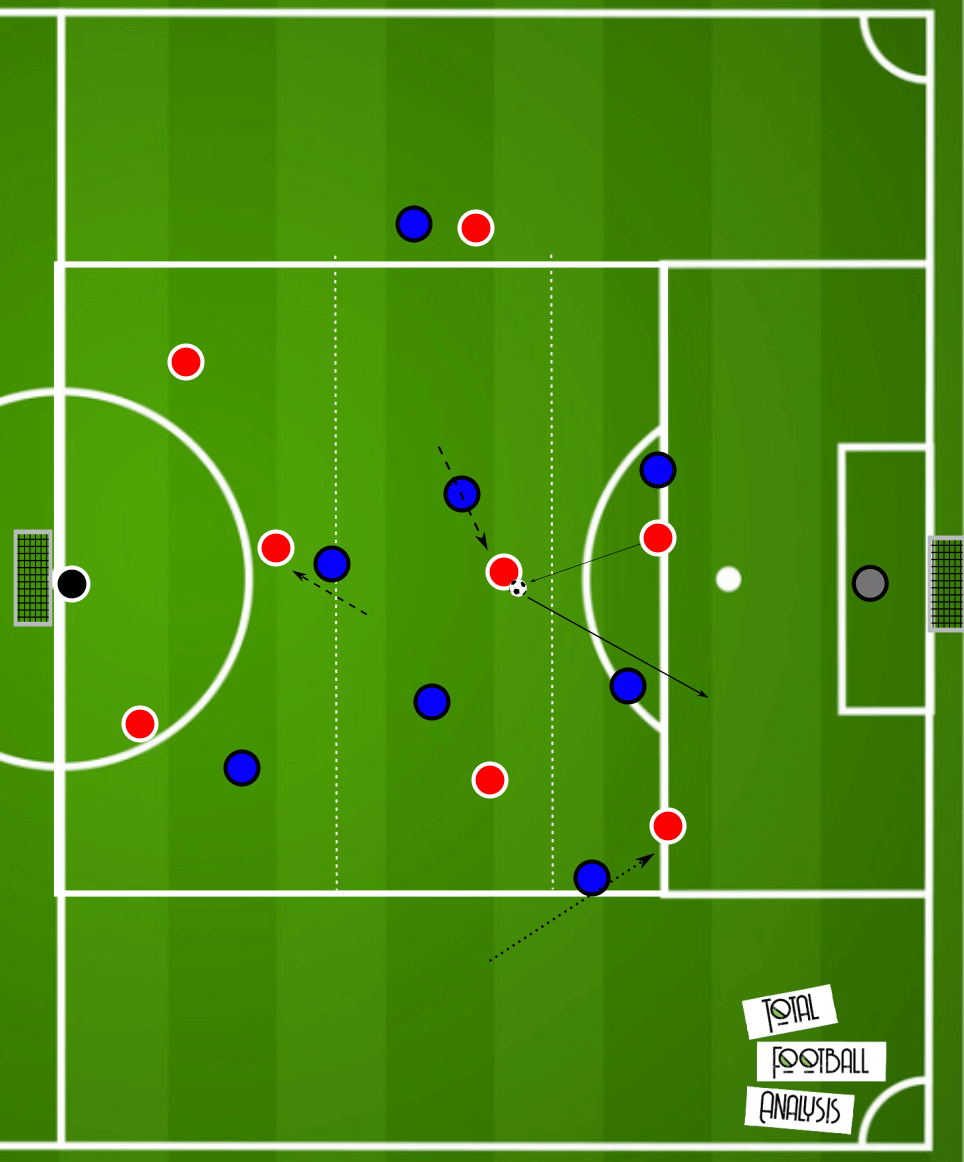

Finally, we can look to move this set of practices into a situation that is the most game-realistic of the three. This practice can still be done with the 8v8 but now with a GK on either side. However, it can easily be adjusted should the number of players at the session be different.

This practice is played on a half-pitch and with either wing cut off, to promote the players looking to play inside and through the centre of the pitch where possible.

Similar to the previous practice there is an overload in a team’s defensive third, then there is an even match in the central third, and an underload in the final third.

This practice can be end to end, or there could be a focus team, in which case (if it were the red), the blue team could have a time limit in which to score once in possession e.g 10 seconds.

The picture of this practice shows that the thirds aren’t evenly divided with the final third much bigger than the other two — and with the central third, the smallest.

Having the final third bigger gives more space to pick out through passes in behind, and the edge of the 18 yard-box can be an offside line, forcing the blue defenders to keep height.

The central third being the smallest of them all ensures play must be played quickly once in the central third. Whilst this forces our midfielders to play off of limited touches, it may also encourage our defenders to be braver in playing through immediately into the final third.

There are wide players too and they are operating in a 1v1 on either flank. Having this as a contested duel forces these players to either play bounce passes and help their team create different passing angles as well as provide a relief option should there be no passing opportunities. However, it also prevents them from getting on the ball, dribbling down the line, and crossing. This isn’t to say they can’t do this, but it’s difficult for them, and, hopefully, given the focus of the session, they will be more committed to playing one-touch passes, on top of making runs in behind (which will be addressed in more detail later on).

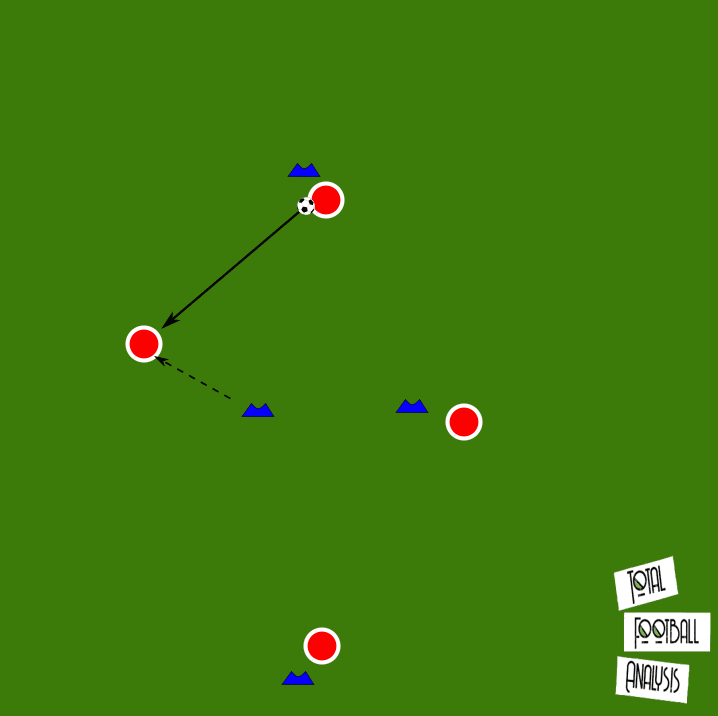

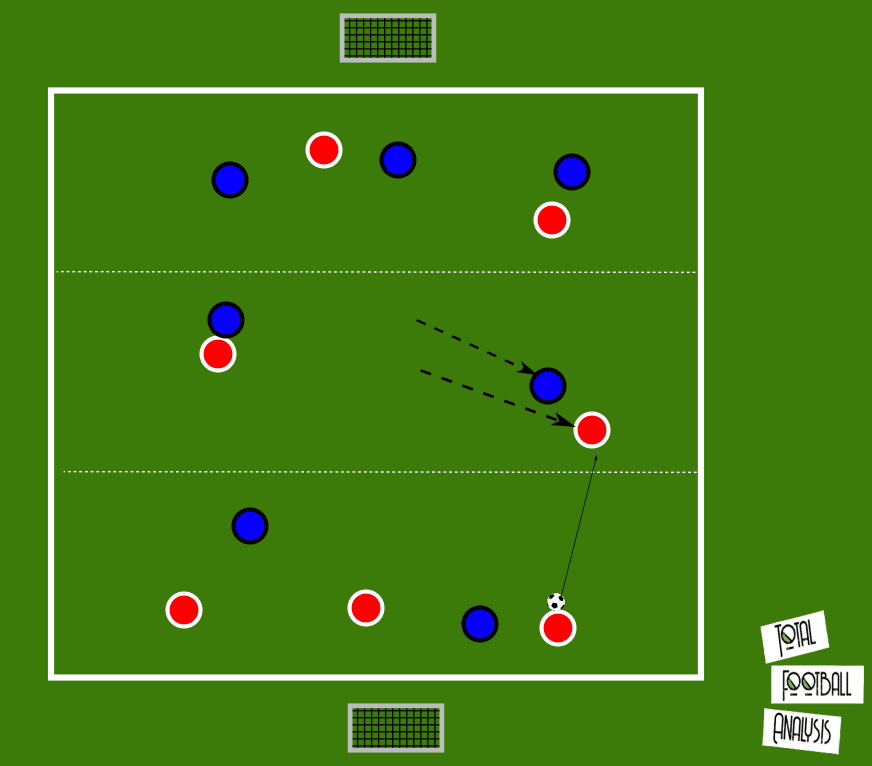

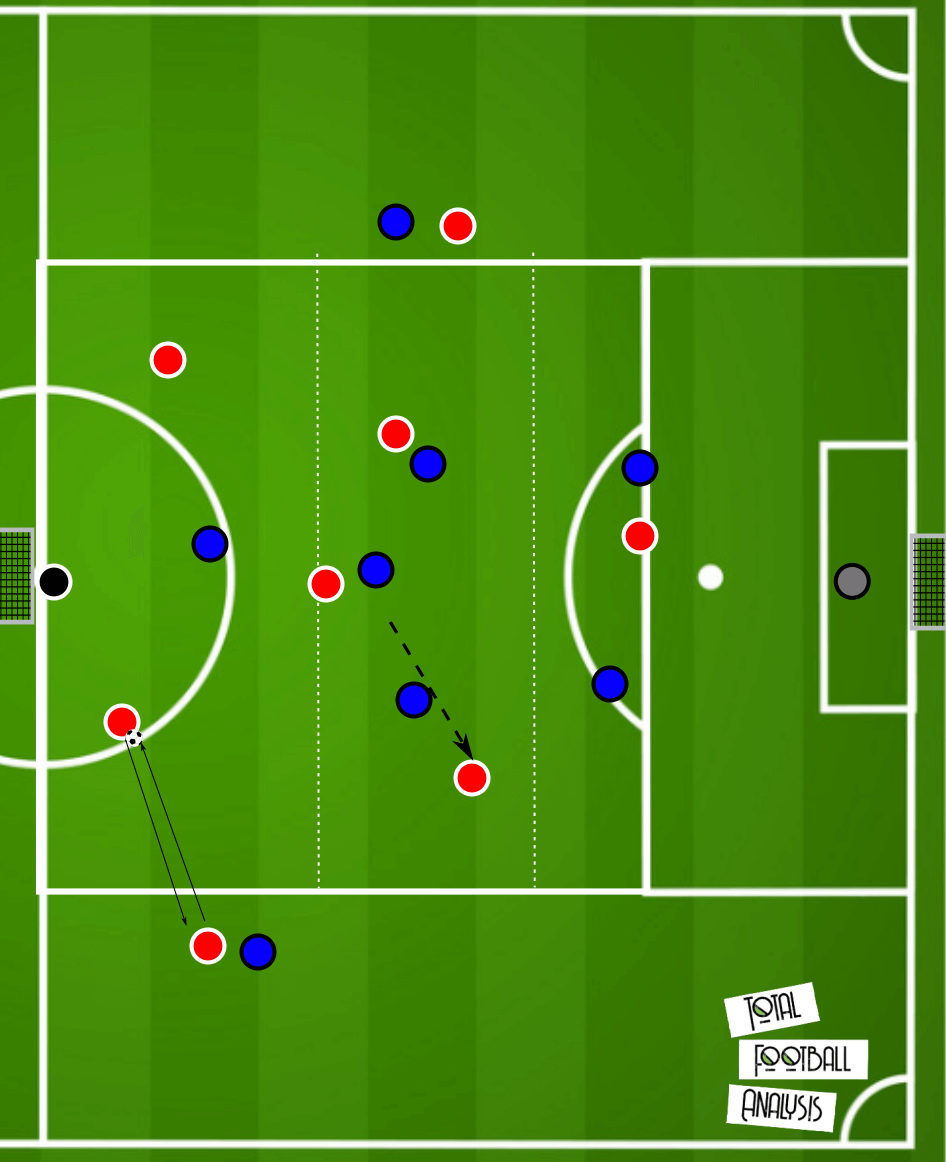

The following image shows an example of the team in possession using a quick one-two, providing time for their midfield to make a run, but also having a midfielder drop into a space closer to the wing; in a game, space would now have been vacated.

The third aren’t strict, and one player from either side can rotate into another third as they see fit. This promotes rotation but also allows players to explore the space they can either create for themselves or for others by changing horizontal lines.

This could be the centre-forward dropping into the middle third to receive a line-breaking pass, or, as the next image shows, a midfielder dropping into the defensive third, providing them with the back three we had in the previous practice, creating greater ball security in build-up play, but also creating space for the through pass in behind.

We can see the other two midfielders reacting to this pass by quickly supporting the pass, with runs close to the centre-forward.

Finally, as alluded to earlier, the wingers can support attacks in other ways than just being a simple option to bounce the ball to when necessary.

If they see the opportunity, they can angle a run in behind. Of course, when breaking lines into a centre-forward, then with a central-midfielder supporting this pass and getting on the ball within 25 yards of goal, if they want to shoot they can do so. However, should they be more patient, they may have the opportunity to slide in one of their wingers making this angled run into the space behind the opposition defence. Again, the winger will need to stay onside, and they can be tracked. However, this pass option forces the central midfielders to once more play quickly in what would be a heavily congested area of the pitch.

Conclusion

These following practices look to suggest a framework that could allow a team to start from a simple, unopposed passing pattern before advancing all the way into a game-realistic situation played on half of the pitch.

Players should be encouraged and rewarded to be brave in playing forward, preferably breaking lines by playing through their midfield. However, we want them to pick the right opportunity to do this and not force it. Patient ball-circulation and bounce passes with forward or wide players can stretch the opposition midfield’s shape and present forward passing lines.

Passes need to be punched at a strong weight, and the passer needs to look at whether their intended recipient is isolated or has options around him that can support the pass.

Players close to the receiver need to be switched on and ready to support the forward pass. They need to understand that if the ball is offloaded to them, likely in the centre of the pitch, then this is a busy area and they will need to play quickly themselves once in possession. They should look for the shot or a through pass in behind for a player to run onto.

To create these forward pass options, midfielders can use their movement to draw their markers wide or into positions that open up passing lines, whilst midfielders and attackers can explore rotation, dropping into different areas of the pitch that could once more draw the defence out of shape, but also potentially find them space to receive too.

Comments