In my opinion tactical flexibility is one of the next upcoming trends within football. The rise of analysis allows now for teams to be better prepared prior to a match on their opponents play, and also now allows for teams to be better equipped to understand what is going on during the game, and therefore gives a better chance for a reaction from the team. There are two ways of looking at tactical flexibility, with the first one being a teams ability to perform within a different number of shapes, formations and roles. For example, a team who has the ability to both press high in a game and then sit in a deep block could be considered tactically flexible.

But one thing which underpins tactical flexibility, and brings me onto the second point, is decision making and a players/teams ability to solve a problem in a variety of ways. Players have to be able to react and make decisions based on hundreds (if not more) variables within one game, and so it is impossible to traditionally coach every decision in an instructional sense, and therefore decision making and experience is at the forefront of this topic. Within this tactical analysis, we will look at the advantages of tactical flexibility, how it is formed, and give some ideas for practices or coaching methods which benefit tactical flexibility.

Principles

The principles of any team are vitally important when considering tactical flexibility. For a player to perform within any complex tactical system they must have an excellent knowledge of what the team’s principles are; just because a team is tactically flexible doesn’t mean these principles need to change, but the way in which they are executed does change.

For example, one of the main teams we will look at throughout this analysis is Borussia Monchengladbach, and this game in particular against another tactically flexible side in RB Leipzig. First I’ll give some background around this Bundesliga game.

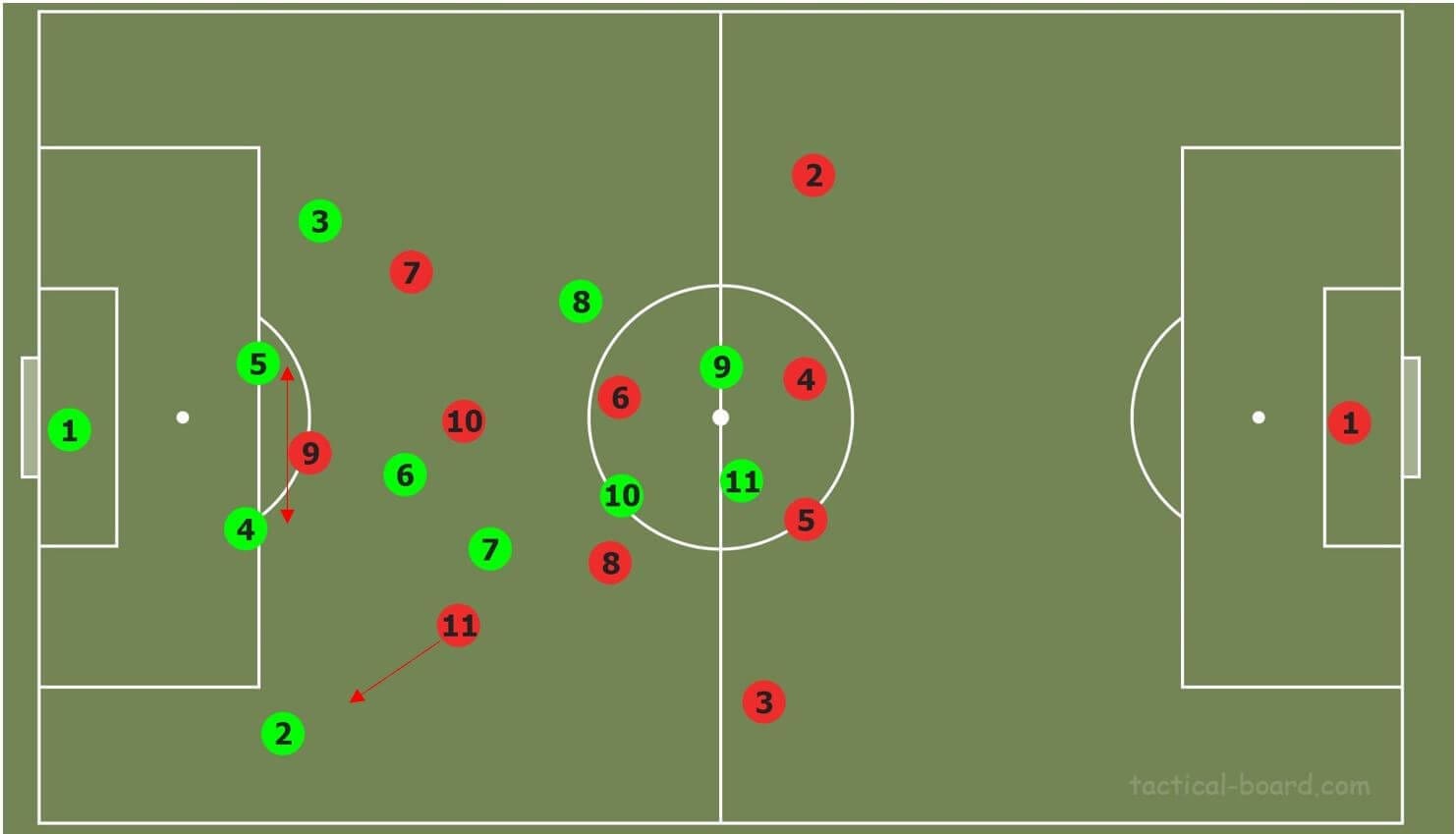

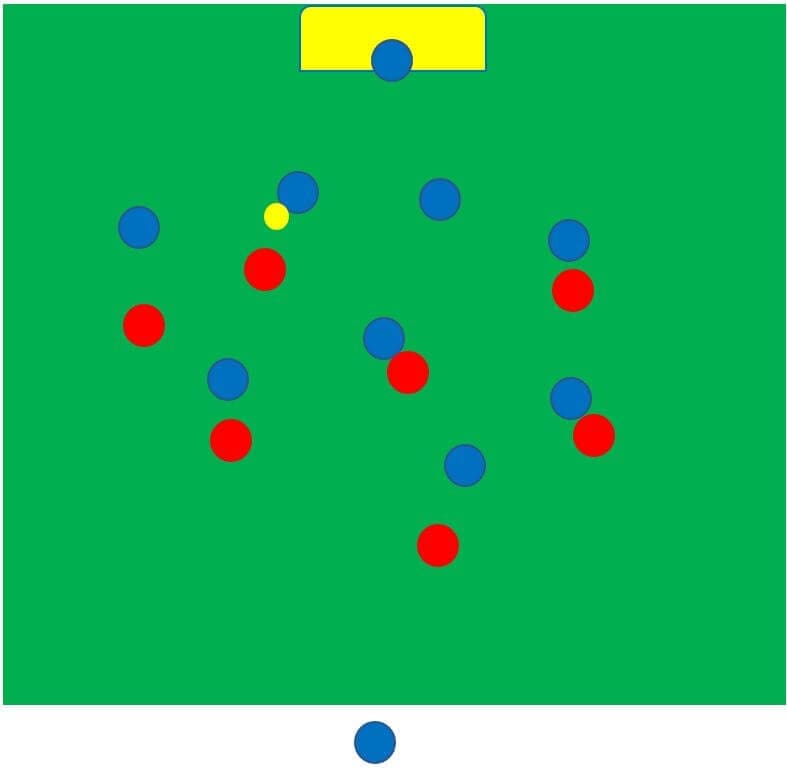

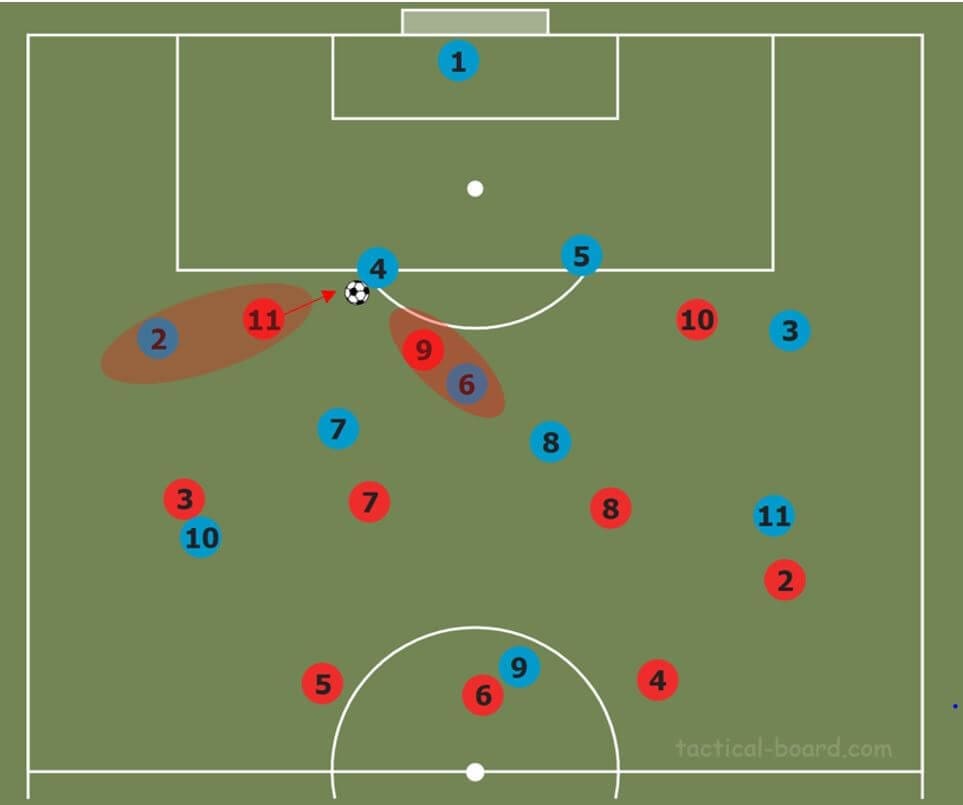

Gladbach usually set up in a 4-2-3-1 or other four at the back formations, while Leipzig at the time were expected to use the same in a 4-2-3-1. Gladbach’s coaching staff clearly recognised this and set about devising a structure that allowed Gladbach to beat that 4-2-3-1. The solution which was devised was a 3-4-1-2 shape, which allowed them to overcome the first line of the Leipzig press easily. Within a usual 4-2-3-1 press against a back four, you would expect this structure below, with the wingers pressing the full-backs and one striker covering both the centre backs.

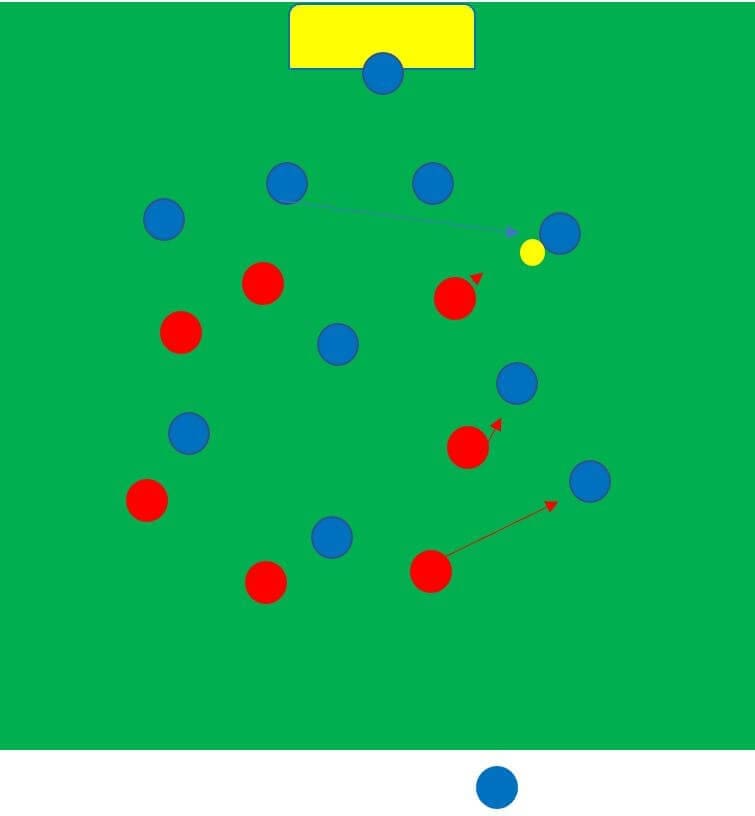

But with Gladbach’s switch to a back three, it now meant that the wingers were pressing a wide centre back, which created lots of space in the wings for the wing-backs, as we can see below. This meant that Leipzig had to commit their full-back forward in order to press this wing-back.

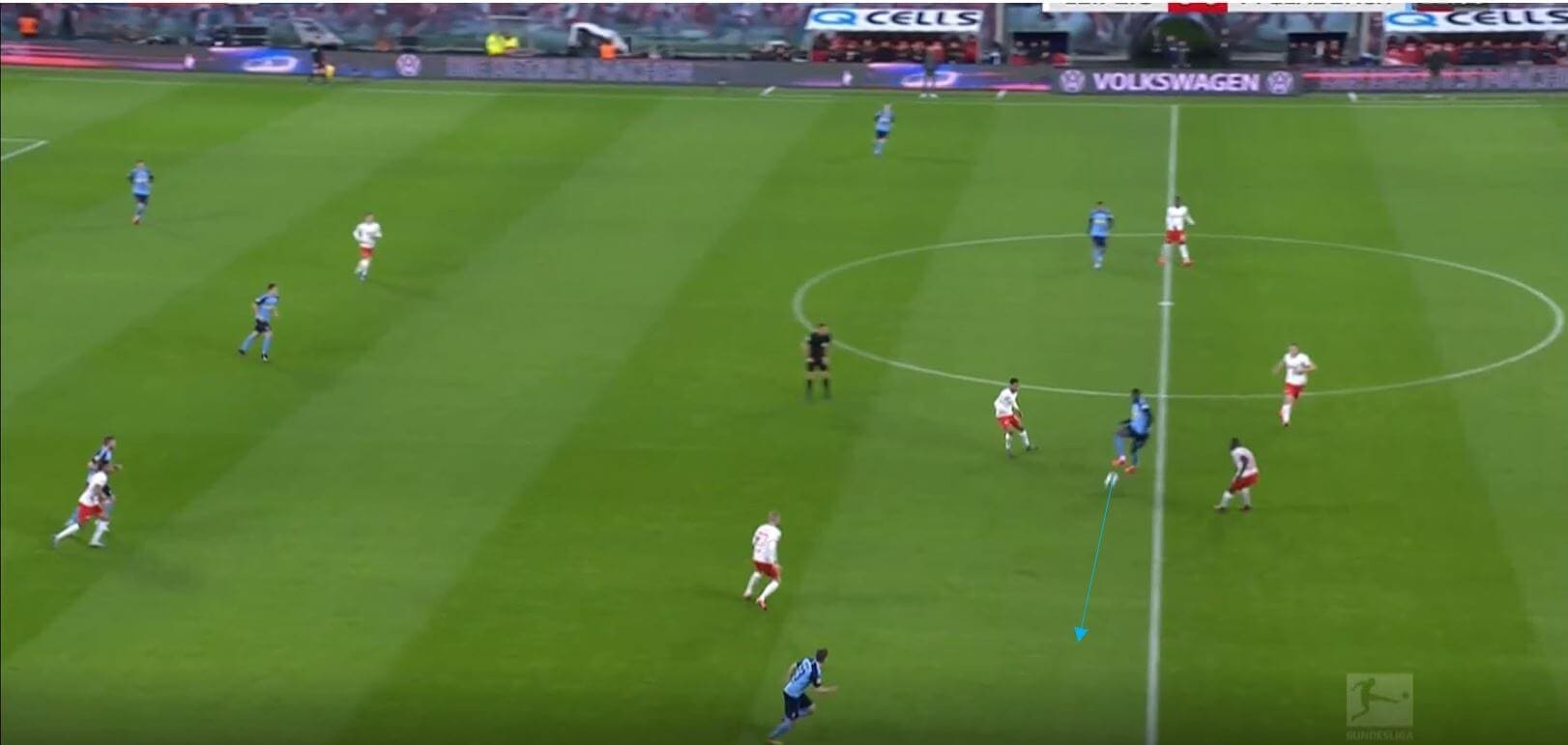

This allowed Gladbach to build successfully from the back, which was already one of their principles, but the shape they did it in was catered to their opponent. The same principles that they have in their ‘usual’ four at the back formations were not hindered by this adjustment, and so Gladbach just played to their principles in the best shape to beat that opponent. We can see here Gladbach continued to play their vertical style of play, with a focus on getting the ball to the furthest player in order to gain better body orientation higher up the pitch for the second receiver.

Now although the tactical flexibility in this sense was very much coach-led formation wise, the success of this flexibility it is still down to the decision making of the players, which within different formations is drastically different. We can see this below if we compare the role of the full-back/wing-back in two scenarios. Here we can see the back three scenario, where the wing-back is pressed usually from behind, with the player’s body orientation facing his own goal. The player cannot play the ball inside due to occupation by the opposition, cannot realistically dribble past their opponent, has to use their weaker foot to thread a pass through and cannot see where they are passing the ball to or where the opponents have moved.

If we now compare this to the Gladbach full-back’s usual role in the team we can see the differences in game dynamics. Now, the body orientation is facing forwards and pressure is coming in front of the ball. Inside lanes are open but the out of possession’s pressing distances must be considered, the player is now using a different foot to play the ball, is playing a straighter pass down the line to a player they can see and can play backwards if needed.

The differences between the two roles in just this phase of play are drastic, and so players need to gain as much experience as possible in different solutions.

Giving varied experiences to aid understanding

Football is a complex environment with so many decisions taking place the whole time, and so for players to become tactically flexible and solve these problems, they have to experience as many different problems as possible. One of the aims of any practice around improving this topic is this: How many different solutions can we create to solve the same problem?

The simplest way which comes to mind to improve tactical flexibility is to train different formations. In attack vs defence practices change the formations of each team often, and allow players to experience the different dynamics of each role within different formations. To make this a much more fluid process, the use of rotations can be helpful in allowing your players to get a feel of several different roles and therefore experiences, while still playing within the team’s principles.

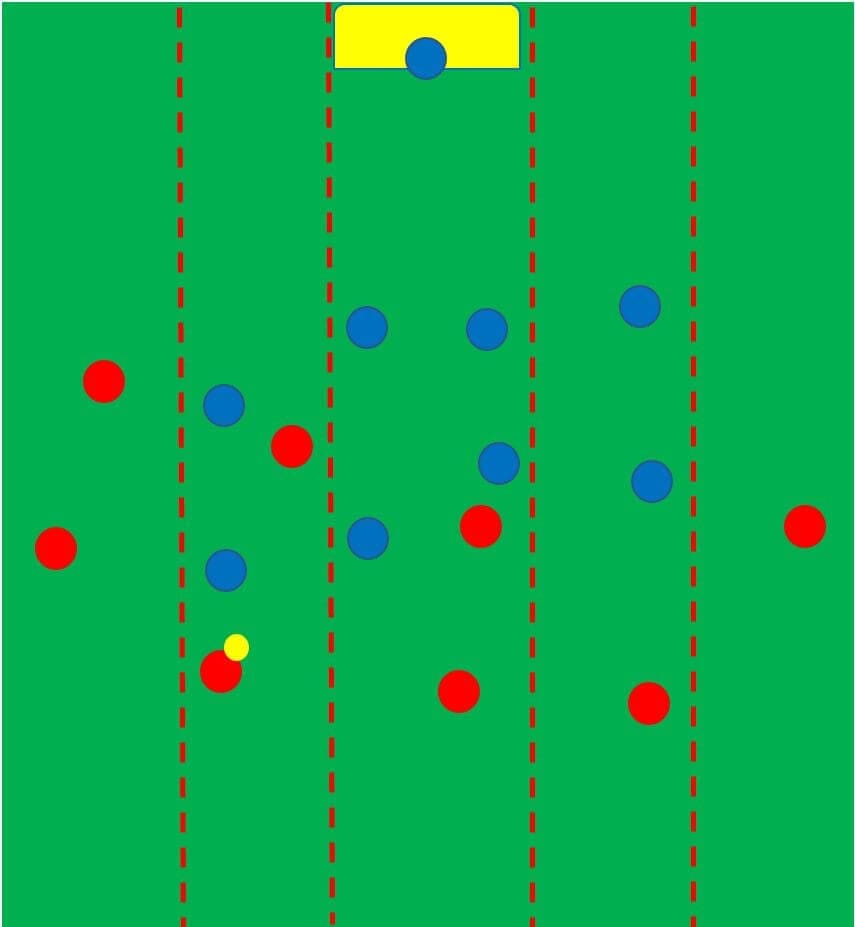

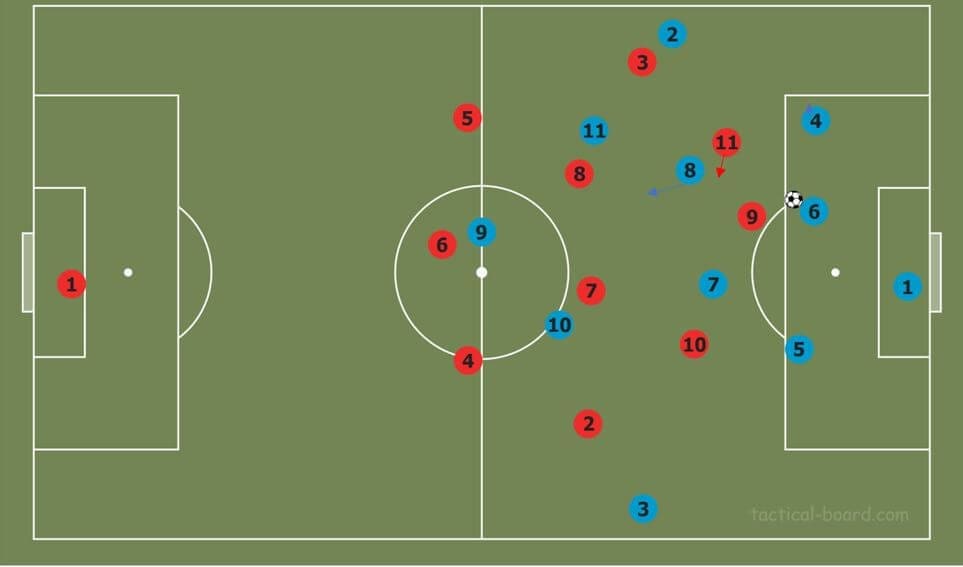

For example, if one of your team’s principles is constant occupation of the half-space with the view to penetrating, with constraints you can put a focus on this while still allowing your players to gain varied experiences within the session. Below we can see an attack against defence practice which I suppose could also be opened up to a normal match. The half-space, wing and centre are marked on the pitch and the red team simply try to score, with a constraint being that per time you enter a vertical channel you are only allowed three touches. Therefore, players must constantly rotate in order to be able to receive the ball, and so one player who may start in a central midfielder position could end up having played in the wings and half-spaces before a goal is scored, and therefore they gain experience many more situations and stimuli, which aids their decision making. You can edit the constraints to time limits within these zones also. We can present a huge amount of problems for the players to solve in one session, and through constraints can guide their solutions to fit our principles. How they penetrate the half-space and score a goal is entirely dependent on their movements, but they still have a focus or direction to work towards.

There are some vital coaching rules regarding this practice. When the ball goes dead or an attack ends, play shouldn’t start from the same point every time, or players the same fixed experience in this situation. Likewise, the defending team shouldn’t always stay in the same shape or behave in the same way, so occasionally manage them so that sometimes they are aggressive and press higher, and sometimes they are passive. As mentioned, if you change their formation drastically to let’s say a back five, the dynamics of the game become different for each player. It is also worth noting that because these constraints are in play, less instruction should be needed from the coach, and studies have shown that the more instruction increases, the poorer learners become, with regards to problem-solving (Turner and Martinek, 1999). Furthermore, learners who are taught more using verbal instruction perform worse in anxiety-inducing environments.

That doesn’t mean the coach doesn’t coach, instead you jump in with questions around where you think teams may struggle, or help the players technically if that is your thing. If you understand the practice well enough, you should be able to plan questions based on where players may struggle to a degree, and academics Pearson and Webb (2008) stated that for questions to be effective they should be pre-planned and specific to the topic.

If players do these kinds of non-formation/position-specific practices from an early age, they should become more well-rounded players who have the ability to solve problems in a number of ways, and should be able to adjust when teams set up not as expected.

Underloads, overloads and adjustments

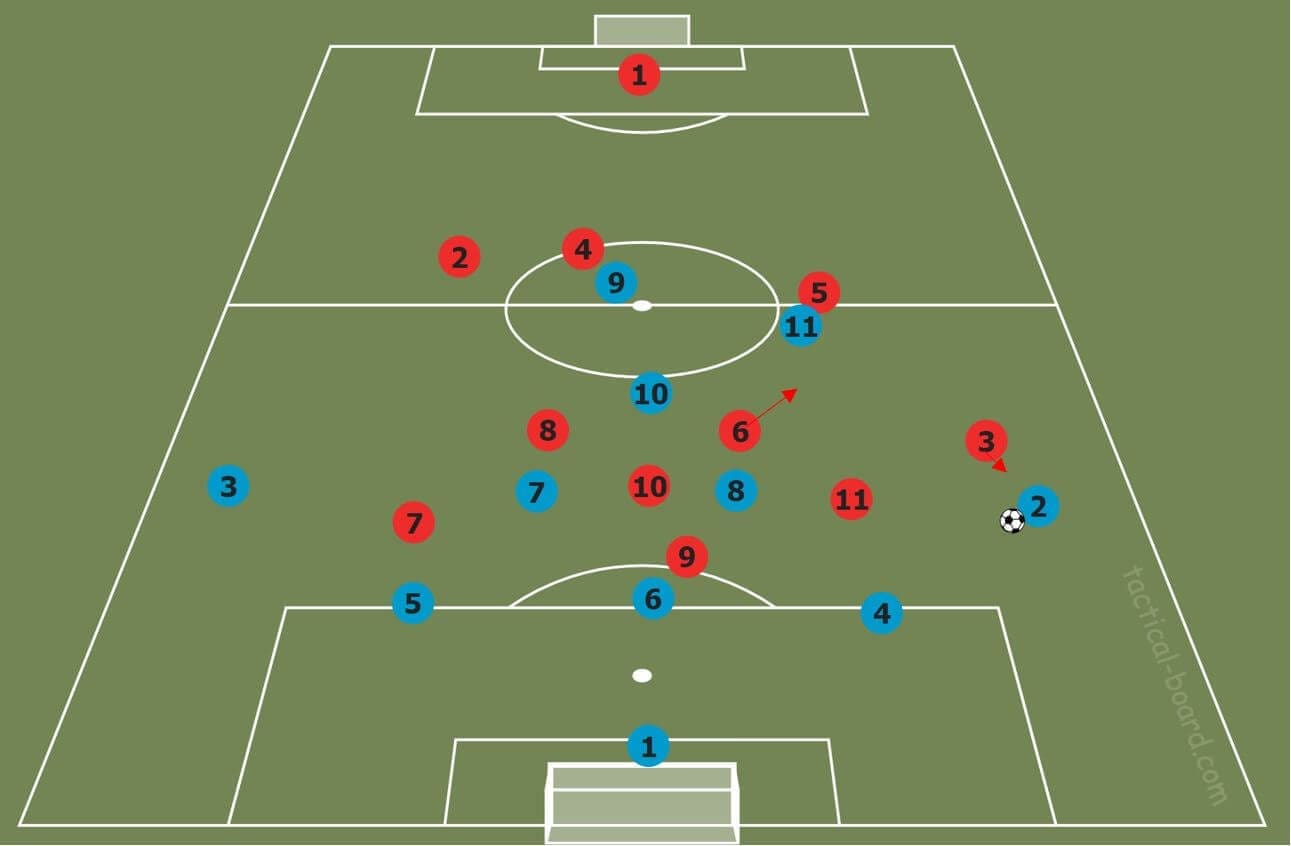

Within a session, you as a coach can force teams to react by making changes to the practice set up, with underloads and overloads being an easy way of doing this. We can see an example here of a basic pressing session, in which one of the team’s principles of pressing from the front to prevent build-up is being executed. The blue teams try to build-up and get the ball into a target player. The pressing team in this example likes to press in a very strict man orientated way, which relies on numerical equality, or as close to numerical equality as possible in order to mark every player.

However as we have seen in the Gladbach Leipzig example, some build-up shapes can be used which deliberately exploit certain pressing schemes, which I have written about in the two previous TFA magazines. Therefore, if we as the coach underload or overload certain areas, or allow players to consider this themselves, then the pressing team has to adjust their structure accordingly. We can see here where the practice was originally an 8v7 outfield, it has now become a 9v6. This now poses the problem of the man-marking pressing side no longer able to do this in such a structured way, and so they have to adjust, which is what tactical flexibility is all about. This can happen if a team builds in an unexpected shape, or even just in a normal game where the opposition builds up exactly as you expect them to, no game of football happens exactly as expected, adjustment is always needed.

Again if the principles of how the team presses are understood well enough, they should be able to press in any shape given the right numbers and situation. And again, if they cannot press in this way, they either have to adjust in a game by bringing more numbers forward, or have to drop their press and sit deeper, all of which happens within a game. Dropping back to sit deeper can almost give time for everyone involved to develop a solution.

The use of different formations

Training these adjustments in this way makes it a little less structured and more random, but it could also be done in terms of completing a session on pressing against a 3-5-2 within a 4-4-2 for example. Again if your principles remain fairly similar throughout regardless of formation, flexibility becomes much easier, and principles aren’t something which adjust within a game.

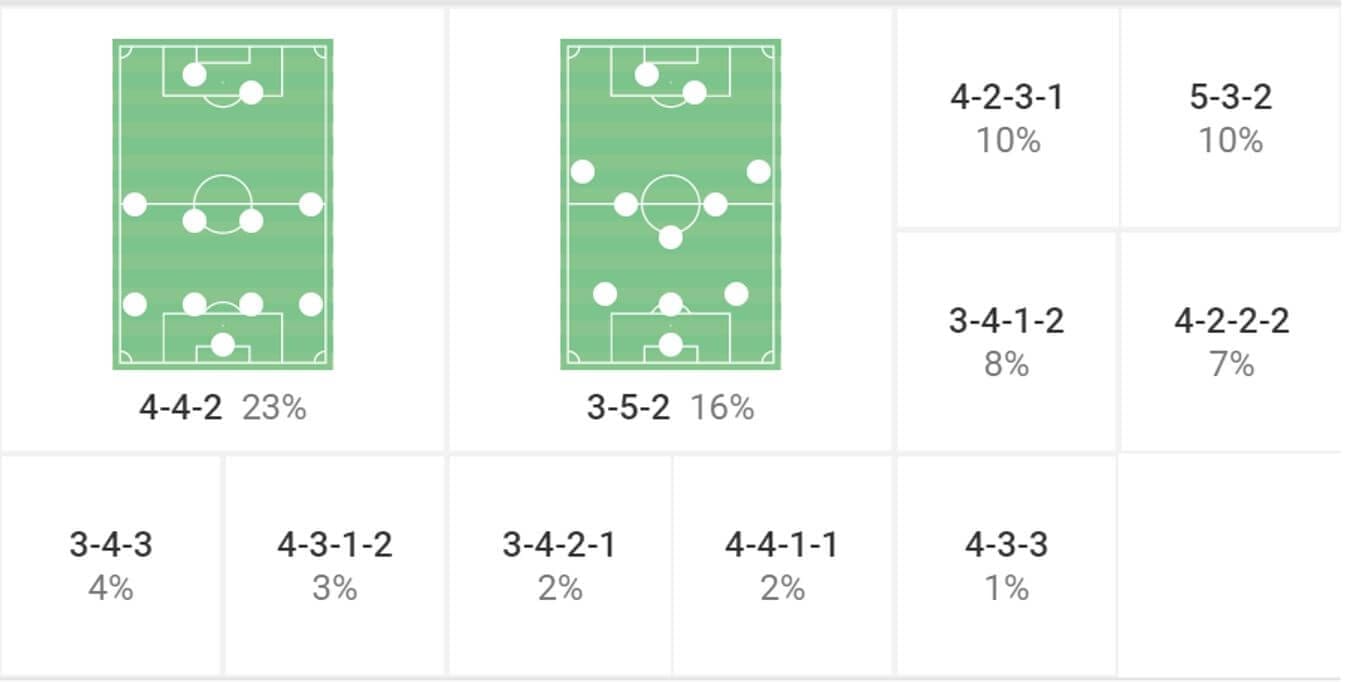

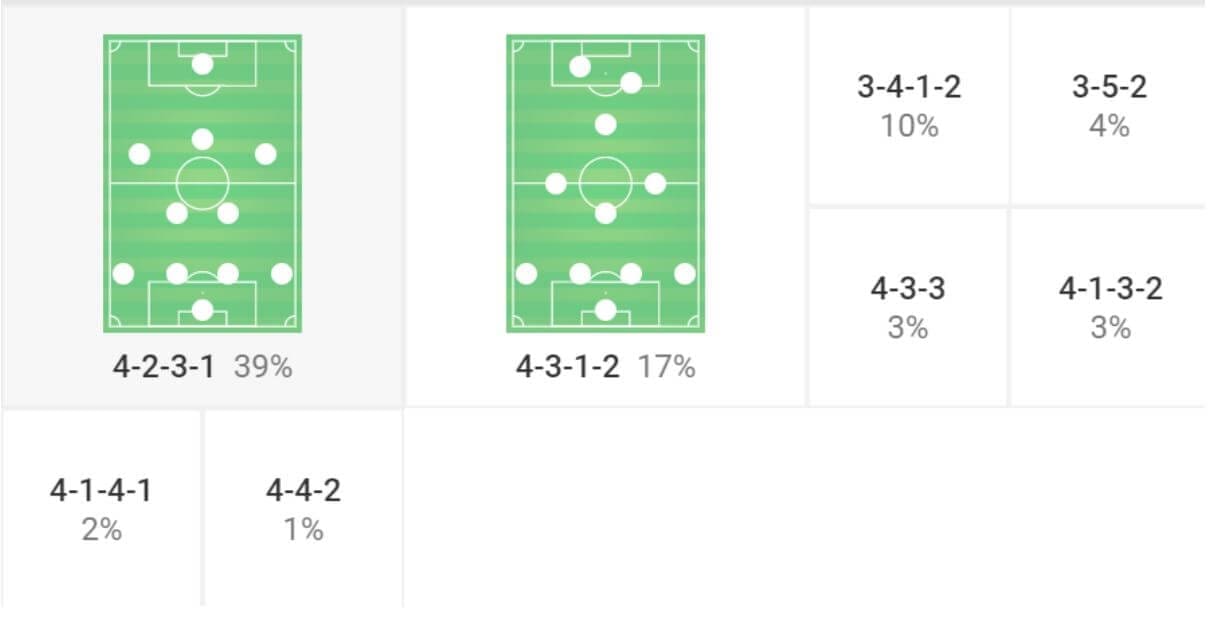

If a coach has the knowledge to use a specific formation in order to gain an advantage in one part of play, and their players can play within this formation, they have an obvious advantage. We can see below RB Leipzig (top) and Gladbach’s uses of formations this season. Leipzig recently showcased their flexibility in a 3-4-3 against Tottenham in the UEFA Champions League.

To give an example of how useful this ability is, If I as a coach know my opposition is going to press in a 3-4-3 in this way highlighted below, and I usually build in a 4-3-3, if my side can’t adjust there is a chance they cannot build up.

If I can then set up my team to play in a 4-2-3-1, and the players have the capability to understand the dynamics of each position due to the training methods discussed, then we can potentially overcome the build-up. Here an overload is created on the central striker’s cover shadow, which affects the roles of the wingers within the press.

Conclusion

Tactical flexibility comes down to both the players and the coaches ability to problem solve and adapt. Much of this training methodology discussed focuses on improving players understanding or football intelligence, and if coaches can cater setups depending on the opposition then they can find success, as Leipzig and Gladbach are testament to this season. With pitch-side monitors now available to coaches and analysts, these problems can be spotted more easily and then have to be communicated to the rest of the team, where the team then has to respond. This can then be followed by the opposition responding and could see football become even more tactical, and start to become almost how José Mourinho described Italian football here:

“I remember Inter versus Genoa, it was my first experience in Italian football. My opponent was Gian Piero Gasperini. Inter started off adopting one tactic and they went 5-3-2. I wanted to win but it was a draw.

Twenty minutes after the beginning of the match I changed my concept and then again in the second half and Gasperini kept adapting to me. We followed each other five times, I wanted to win, he didn’t want to lose. It was like chess.”

In reality, and certainly at lower levels, it is difficult to perform so many adjustments as a coach, and your players have to respond, so train them to do so.

Comments