The fluidity in movement of your midfield can be directly related to the ability of your team to successfully advance possession through the central channel and half-spaces. When setting out a team pre-game on a tactics board, we can so often define our central midfielders’ positioning by where we place them on said board. For example, with a midfield three, we often place a pivot, or a 6, in the deepest position of the three. Following this, we may then see two number 8’s, two number 10’s, or an 8 and a 10.

Frankly, we can get too bogged down with the specificities of a number or a position. Ideally, whether working with a midfield three or a central-midfield pairing — whatever it is, we want a presence ball-side, and we want a presence behind the opposition midfield.

This article and tactical analysis will look to demonstrate a session that could be run to build your team’s understanding of midfield rotations. On a basic level, it is important to have rotation and movement in the midfield to prevent your midfielders from being too easily marked, and there being too little space to play through the centre of the pitch, whether that’s with the midfielders touching the ball or not.

Teams who don’t play with a defined pivot can frequently create space to play past a compact pressing unit and get their midfielders on the ball or create forward passing lines.

We can see such fluidity in the midfield positions from some of the world’s leading coaches, so idolised for their fluid, high-tempo, beautiful football. Marcelo Bielsa, currently working in the Premier League with Leeds United, and Gian Piero Gasperini, currently working in Serie A with Atalanta, are two prime examples of coaches that employ midfield rotations to great effect in their teams.

Why are rotations needed?

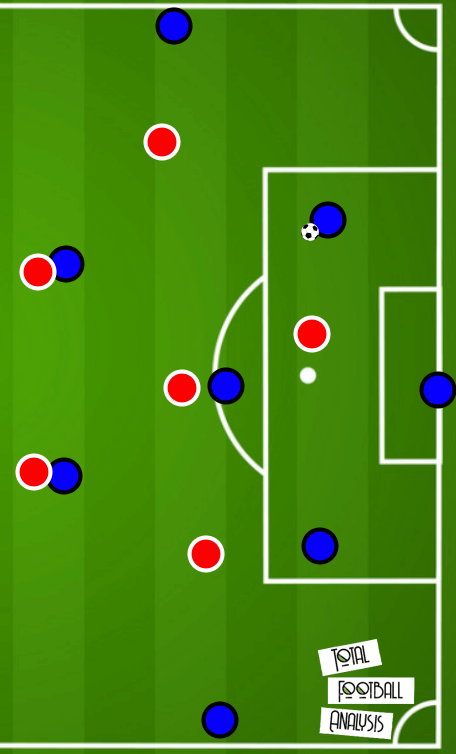

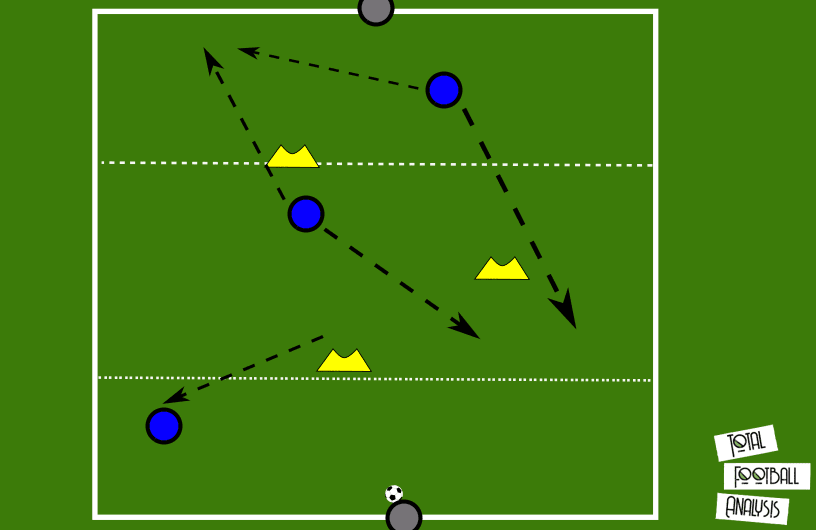

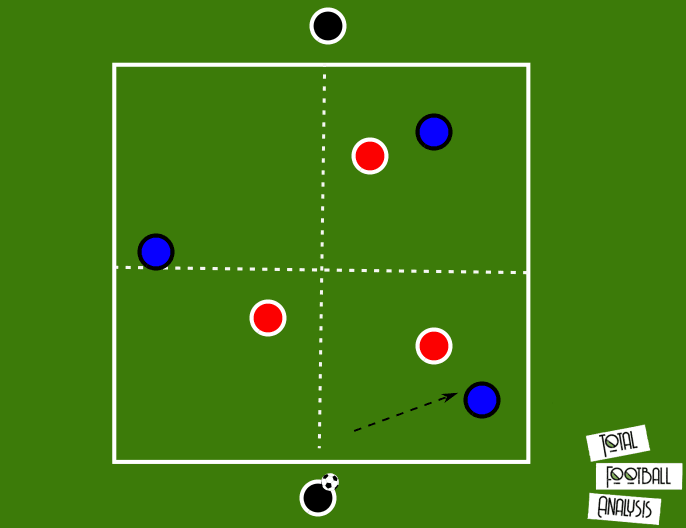

This problem is demonstrated in the following image where the blue team have their pivot and two number 8s, in this example, closely man-marked by the red midfield. The red team’s press is led by a front three who are compact and preventing central passage, whilst the wide forwards on either side of the centre-forward are in a half-and-half position, blocking the inside pass, but in a place where any pass to either blue full-back can be cut out or easily pressed.

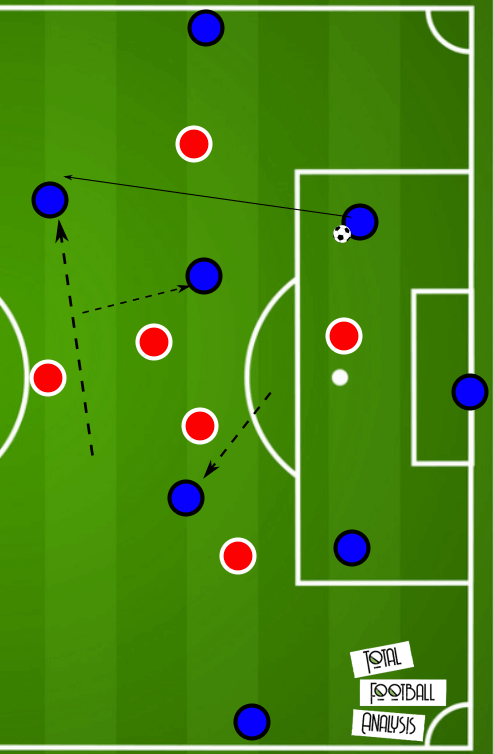

If the blue midfield can successfully rotate, and in a way that is clearly in synchronisation with one another (through lots of practice!), then opportunities to play forward can present themselves. We can see an example of that in the following image.

Before this article continues, it feels important to mention that Rotations & Interchanges by John Wall & Hans Backe is a truly outstanding and easily digestible piece of work on Marcelo Bielsa’s philosophy with plenty of examples and in-game footage that should be consulted for more information. The idea for this piece and the subsequent sessions have been inspired by their work — as well as by the work of Bielsa and Gasperini themselves.

Furthermore, there are two principles we want to achieve through this session.

Firstly, as already mentioned, there needs to be (at least) one player beyond the opposition midfield. If playing with a midfield pair this could mean one midfielder drops deep to offer a pass option to their backline whilst the other pushes higher and looks to access the space between the opposition midfield and their defence. With a midfield three, this can be achieved with one or two players doing it (there is often debate over whether it should be one or two, but in this writer’s opinion it is not so important as long as there is at least one).

In doing this, it forces the opposition midfield to constantly have to be aware of a player making a run in the space behind. Their gaze shifts from solely being focused on what is in front of them to now what is behind and even to the side.

This can, firstly, allow that midfield to provide a line-breaking pass option, but equally, it can drag the opposition midfield out of shape and lead to even more advantageous passes, as demonstrated in the next picture.

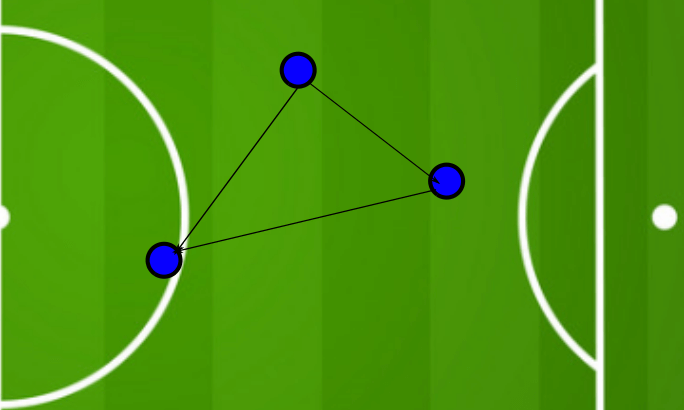

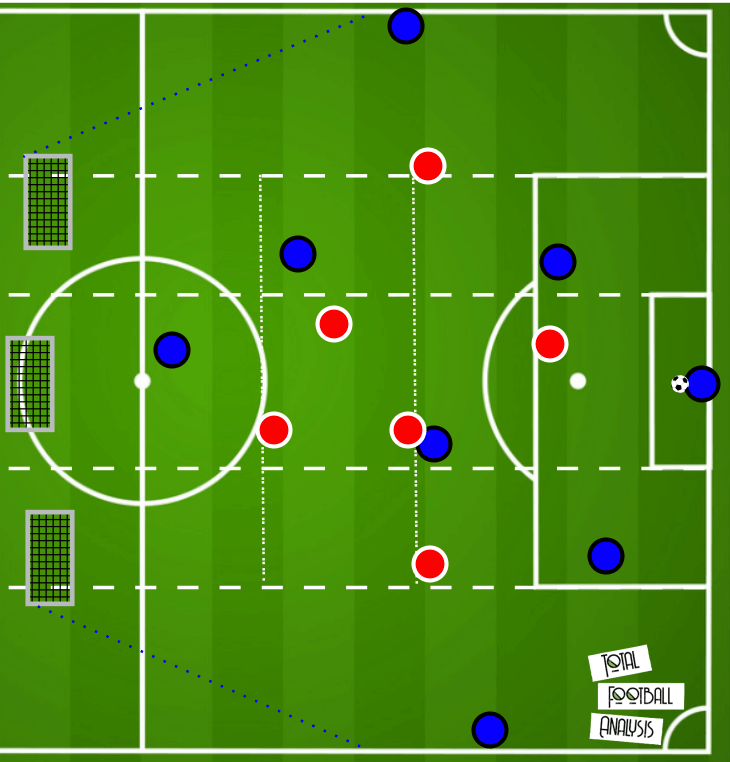

Secondly, we want a stagger in our midfield. In the case of a midfield three, we want to ensure they are not on the same vertical lines, but also not on the same horizontal lines. By having this, there should always be different pass options available. It is no use to us if our number 10 is standing directly behind our number 8. A “play sign”, seen similarly as a “>”, is often used as a visual reference for the midfield to understand. However, that visual puts the pivot and the 10 on the same vertical line. There should still be a vertical stagger. We can see in the following image that all three midfielders are staggered horizontally and vertically.

Part 1

Before looking at moving any kind of rotation into a match pace tempo it would be pertinent to allow the players the freedom to explore different rotational patterns without the pressure of being tackled, initially.

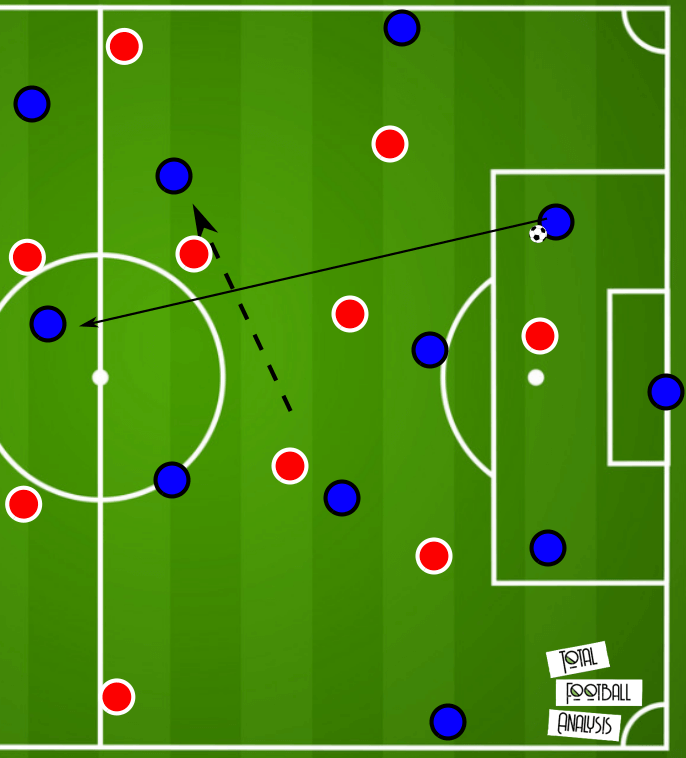

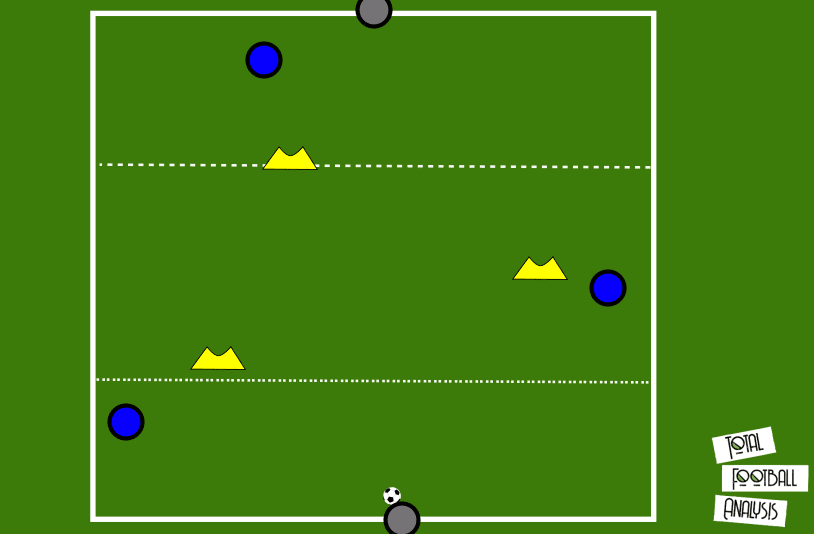

You can look at specific patterns, there are plenty of examples of Marcelo Bielsa’s preferred patterns available online. However, this practice divides the area into three vertical zones, and you can ask the players to ensure that all three zones are filled. We ideally want to see our midfield three occupy different spaces. The reason this writer personally has no preference over two players going beyond the midfield line is that this can encourage the opposition midfield to drop. By having a player in all three zones, there is a much greater chance of engaging the opposition midfield press, whilst also stretching them, and accessing space across the midfield. Ideally, the pivot sits just behind the furthest forward opposition midfielder, represented by a mannequin or a big cone, as shown in the image below. In doing so they can make a late move on either side without being closely marked, at least at first.

We want this player to move at a diagonal angle to the side and open their body up. In doing so, they can see the full pitch, they don’t close the ball-carrier down, and they leave plenty of space open ahead of them for the other two midfielders to access.

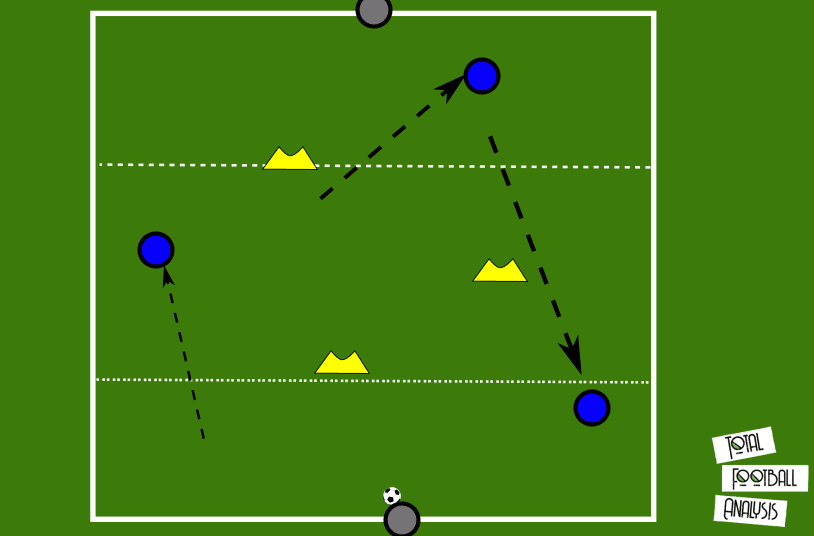

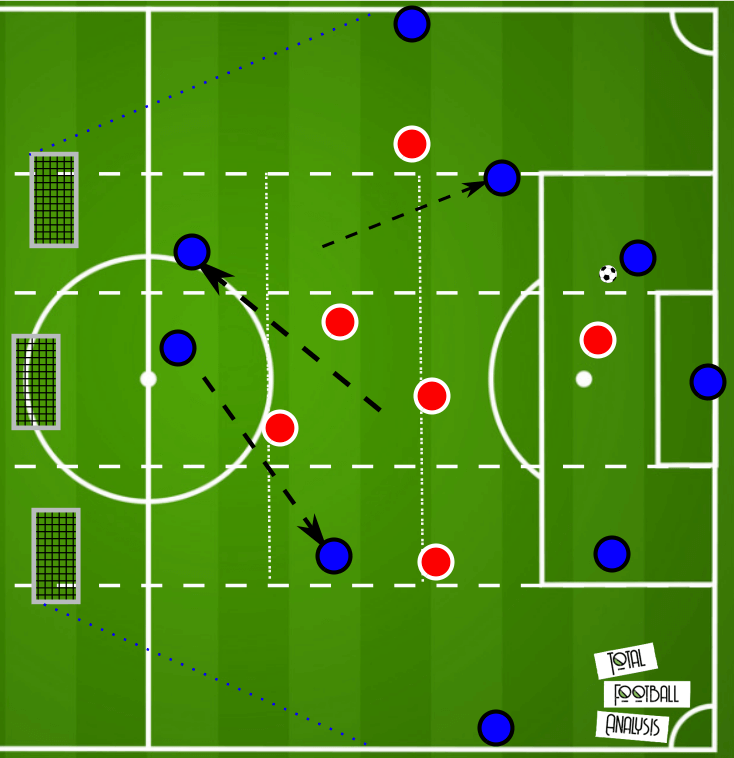

In the following image, we can also see the midfielder in the central zone, which we can call the 8, and the midfielder in the farthest forward area, which we can call the 10. The aim of their movement is to ensure they move into different areas, so a straight swap in vertical zones makes sense here. One area that needs to ideally be filled is towards the ball and in the opposite direction of the pivot. Either of these players can make this run, whilst the other should ideally push high and move into the indicated area or even take a central position.

These movements could, as the next picture demonstrates, easily drag the opposition midfield apart, leaving plenty of space to play through.

As a coach, you should feel free to play around with this structure, either giving the freedom to your players to rotate based on achieving some basic principles (stretching the opposition midfield, being on different vertical and horizontal lines, and constantly moving between the three zones — although you may wish to ask your pivot to avoid accessing the farthest forward zone if you prefer to have them on the ball consistently in a deeper position, and you like them in that position for the defensive stability they provide on transition).

However, another example can be seen below. After the pivot’s initial movement, could the 10 then instruct them to push forward and drop into this position themselves to receive? The 8 can then respond to this by pushing forward into the farthest forward zone.

This activity shouldn’t be run for too long, given that it is unopposed. Some basic coaching points should always be addressed when doing such a practice. The tempo of pass needs to be high, the ball needs to be played to the correct foot, e.g. if the pivot drops out wide and they have an open body position, the ball needs to be played across them, not to their ball-side foot. The speed of the rotation shouldn’t be laboured, but it also can’t be at a million miles per hour. The players need to be sharp when they make a move and call for the ball but beforehand slow enough where the change of pace will surprise their marker. It is not a “one-pace” practice. Finally, communication between the players is vital for success. They should be talking to each other all the time as to where to move. The players further up the pitch, specifically in the 10 space, can see the whole pitch, so their communication needs to be good — but players can help themselves through consistent scanning too.

On top of this, the coach needs to be thinking about those key principles. Are the players on different horizontal and vertical lines? Is there always more than one passing option? Do we always have a player in the far zone, beyond the opposition midfield, stretching the pitch?

Part 2

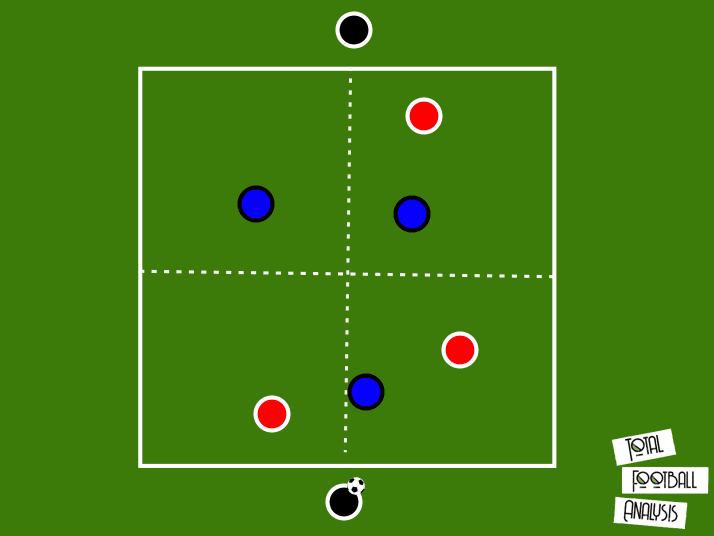

An excellent activity to build on this but now against an opponent in a more match-realistic situation can be done in a 3v3 with a bounce player on either end. This can be a high tempo session, done in short bursts to ensure a match-pace tempo. A point is scored when the ball is worked from one end player to the other. However, the three midfield players should constantly be looking to rotate, with a reference point being that they never want to be in a horizontal or vertical line with one of their teammates. This is a coaching point that can be developed as the session moves forward, but obviously, if they are always on different lines both vertically and horizontally, then there should always be three passing options available. A progression for this exercise is that if the end players can play directly to one another without any midfielders touching it, then the team in possession gain two points.

The second coaching point that needs to be addressed in this practice is the movement of the player closest to the ball. Particularly with youth coaching, it is highly likely you will see a player move directly towards the ball-carrier, and even give an option a matter of yards away. Not only is this not game realistic but it is important not to close the ball-carriers space down. By moving directly towards the ball-carrier, like in the previous image, it makes it more difficult for the players further forward to offer a realistic passing option anywhere but wide.

If the player closest to the ball can peel away with an open body position, not only are they a passing option and already facing the goal, but there is space for the players further forward to receive anywhere across the area.

Part 3

Finally, we look to put all of this into a game situation. Depending on the level of your players you can divide the pitch into five vertical zones (wing, half-space, central channel, half-space, wing), and then proceed to have those same three vertical zones in there too. This provides the three midfielders with a constant reference point for their rotations. Whilst this area shown is just large than a half-pitch, it makes sense to angle the pitch so there is less space out wide and the ball is forced inside. Of course, this example is shown with a 7 +gk v 6 and based on your numbers you may need to put in more players out wide etc, so it may not make sense to cut this space off. However, if you can force the play to go through the midfield three as often as possible, it will obviously be most beneficial for your midfielders and for the success of the session.

As the ball is played from the goalkeeper to the closest centre-back, can the midfielders look to instil their midfield rotations? Their aim is to work the ball forward into one of the three goals. To incentivise your midfielders, you can give two goals if the ball is successfully put in one of the goals after a rotation, or even if the centre-backs or pivot can directly play through the midfield with a floor pass into one of the three goals, that’s worth two as well. But these are examples, and it’s important to think about your game model and your intended outcomes when choosing such incentives. If the red team wins possession, can they get a shot away within 8 seconds? In doing so, it is still match realistic, it keeps the red team interested in winning the ball, and the time limit means the ball will quickly reset with the blue team.

Conclusion

This analysis aims to provide an insight into a type of session that could be run to help your midfield three improve their fluidity as a three, but it can be adapted for if you play with a midfield pair or even with a diamond. The practices shown aren’t groundbreaking individually by any means, and they may well be familiar to coaches reading this piece, but the aim is to put these practices together in a way where the session flows from one to the other, and in gradually building up the complexity of the session, it gives the players involved a greater chance of achieving the coach’s goals for the session.

Comments