The constraints led approach to training design has steadily gained traction within the coaching realm in recent years. This approach is a core pillar of a larger teaching methodology known as “Nonlinear Pedagogy” which is an immensely deep and quickly developing approach. With that in mind, in this article, we will not dive into an analysis of nonlinear pedagogy as a whole but offer a brief introduction to constraints: what they are, why we care, and how to use them.

In ‘The Constraints-Led Approach: Principles for Sports Coaching and Practice Design’ we find a great description of constraints and what they do to a player. “Constraints according to Newell (1986) can be conceived as boundaries that shape self-organisation and can be separated into categories, namely, individual, environmental and task constraints. Through the interaction of different constraints – task, environment, and performer – a learner will self-organise in attempts to generate effective movement solutions” (Renshaw et al. 2011).

To translate this idea to the realm of football coaching: players within a training activity will explore the given environment and find answers based on the problems set forth by the coach. The problems designed into an activity can be implemented and adjusted by creating and manipulating constraints in the said activity. Within an activity, the constraints used will can guide a player to perceive, decide and execute desired actions.

This allows the coaches to create activities through the use of constraints to guide players to desired tactical or technical goals. Do you want your team to switch the point of attack more effectively? Do you want players to press more aggressively in the attacking third? The manipulation of the three core types of constraints will allow you to create an environment that guides players to discover the core coaching point you are aiming to teach within your session.

As previously stated, the subject of constraints led approach’s neighbouring teaching methodologies are beyond the scope of a single article. Below we will touch on individual, environmental and task constraints and how a coach may use them to effectively convey coaching points within training sessions.

Individual

First and foremost, the individual that is being coached brings in a plethora of built-in constraints. When designing curriculum to be taught, coaches must firstly consider the athlete’s current available experience, abilities and capabilities. Additionally, each athlete brings physical personal constraints, such as height and weight, body fat percentage and genetic make-up. On the mental side, coaches must also consider the emotional state of the athlete. What are their motivations? What are their primary emotions and desires? What are their patterns of thinking? How do they perceive problems?

By identifying and targeting these types of individual differences a coach can successfully design a training environment based on the needs of the athlete. As we will discuss further, coaches are able to manipulate task and environmental constraints to engage and create specific emotions, cognitions and actions in players. Neuroscientist J. A. Scott Kelso has noted that the intentions of an athlete are an important constraint, meaning that a coach may manipulate an athlete’s needs, wishes and desires within a training or game environment to create the desired result within a training activity.

By taking the idea that a player can be measured in the previously named individual constraints, a coach can begin to create individual constraints that create an optimal training environment. Firstly, the skill and experience of the player are important considerations. To build upon the player’s current talents, the coach must teach new ideas and aspects of the game within the knowledge the player already has. By observing and defining the base level individual constraints of players to be trained, a coach can then build upon that level to create maximum player development.

By focusing on these individual constraints, a coach or club can also develop and shape the psychology of players as well. An excellent example of a club that places a heavy focus on improvement through the use of individual constraints is Athletic Bilbao. Since 1912 Bilbao has utilized an unwritten rule of only signing players who were born in the Basque Country. Although this leaves their youth system (cantera) to pull from a total population of just over 3.1 million (2017 est.), Bilbao use this rule to their advantage when developing competitiveness and drive within their players.

At an early age, youth products are taught the history of the region and instilled with a strong sense of local pride. This allows the players to realize that when they adorn their club kit for a match, they are an extension of that local identity. Bilbao cantera players of all ages step onto the pitch with well-developed confidence and a distinct playing advantage before the first whistle is even blown.

Environmental

A powerful instrument in a coach’s arsenal of tools to shape athlete solution exploration and perception-action coupling is the use of environmental constraints. Because this is an introduction to the overall concept of environmental constraints, we will focus on three primary forms: pitch shape, game intensity index and pitch parameters

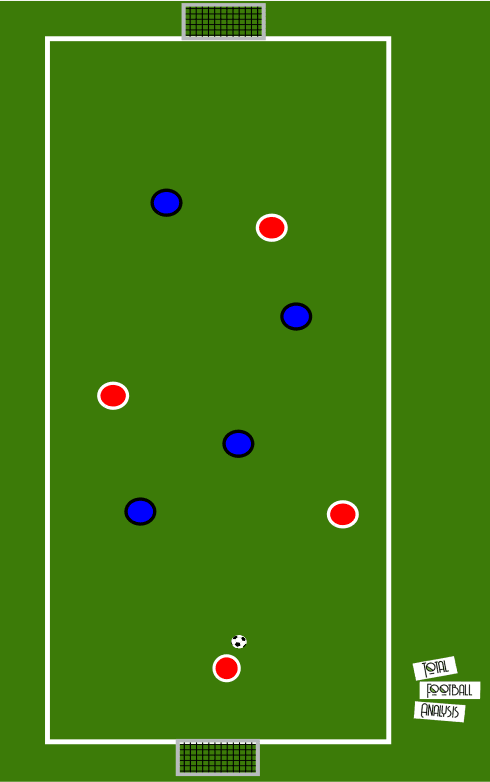

By focusing on and manipulating the shape of the pitch in training activities, a coach is able to help create environments that guide players to play in the desired way. One example is using a big pitch vs a small pitch. Activities with big pitches are useful for producing a frame of reference to the full game. Big pitches can also help to test the player’s ability to defend large spaces, whether that be as a unit or in an individual context. We can also use big pitches to help guide players in the attacking phase to create space between lines and play through opposition. If you give players space you have the stage to teach them how to exploit or restrict it.

Conversely, a small pitch allows a coach to restrict each athlete’s space and time in the game environment. The coach is then able to challenge player’s speed in decision making, first touch, release of the ball and other individual skills.

In addition to the size of the pitch, the dimensions can be manipulated to create the desired learning environment for athletes. An example being the use of narrow pitches vs wide pitches. Narrow pitches challenge players to play with verticality as there is no option to play around the opponent. This can help to teach players to focus on such things as body orientation, positioning relative to teammates and timing of off the ball runs.

Wide pitches, on the other hand, can create an environment that encourages athletes to execute switches in play, which can lead to crossing opportunities or 1v1 situations on the wing. This type of pitch shape also creates a platform for coaches to focus on attacking and defending in wide areas. Additionally, the opportunity to develop blindside attacking runs is naturally increased with this type of pitch dimension.

Thomas Tuchel has been known to constrain the environment of his athlete’s play by removing the corners of the pitch to create a diamond-shaped pitch. This diamond shape forces players to create more diagonal passing lanes, which lets the players have a better body shape and scanning ability when receiving and releasing the ball.

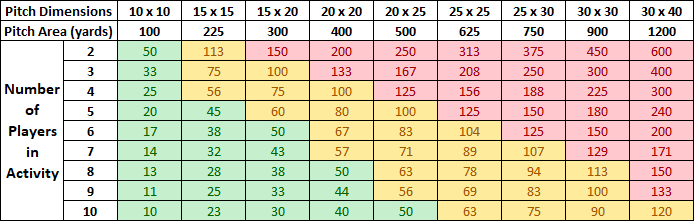

When designing a training activity environment, a coach may also allocate a formula known as the Game Intensity Index. This is done by calculating the area of an activity and dividing that area by the number of players that are involved in the activity so that a quantifiable metric is created. The lower the intensity index number, the more intense the activity is.

“Intensity” can be described as the likelihood of a player to have an opportunity for direct participation in play. The more “intense” an activity is, the more a player will be engaged. By using this metric in all activities, a coach is then able to manipulate pitch dimensions and player numbers to create the optimal intensity for the player group.

Using the FA’s guideline for U7/U8 game format and pitch dimensions as an example we can see how to use game intensity index when designing activities for young players. Currently, the FA implements a 5v5 match format on a 40 x 30 (yards) pitch. By taking the pitch area (1,200 yards) and dividing that by the number of the players on the field in a match (10) we find a baseline intensity index of a match to be 120.

Hypothetically, let’s say our primary goal for this age group is for our players to be able to win 1v1 situations in a 10 x 10 area. The intensity index of 2 players in a 10 x 10 are is 50. This gives us a range to work with.

Green in the graph tells us that the intensity of that activity is as or more intense than our goal of successful 1v1 in a 10 x 10 area. The green numbers are optimal for players who have already met the goal of 1v1 proficiency in a 10 x 10 area and need to be pushed more. Yellow represents a point in between our goal of 1v1 proficiency in a 10 x 10 area and the intensity of the full match format on the weekend. Red numbers show us that an activity will be too easy and will not properly maintain the base level of intensity in a weekend match.

So, if we have a group of players that are not quite up to our goal of 1v1 proficiency that are going to play a 2v2 activity in a session, we can look to the graph for guidance. With 4 players on the pitch, a 20 x 20 (index of 100) would be a good size for players that are in the beginning stages of development. Conversely, if a group of 4 players are at a higher developmental level, a coach could put them in a 15 x 15 or smaller area to optimally encourage their development.

Once a coach has figured out his player group’s optimal game intensity index, he or she may be able to use it as a benchmark to create an ideal intensity in activities for players to develop.

Another constraint that a coach may manipulate to encourage development is pitch parameters in training activities. By creating markings on the pitch, coaches are able to assist in giving players a frame of reference for what the game demands of them in that moment.

In every moment of the game, a player is able to observe four major reference points on the pitch. The ball, teammates, opponents and space. By creating parameters/markings on the pitch a coach is able to help the player observe these references points, make a decision and execute that decision in quicker speeds. A coach, based on his or her game model, is then able to say “When the ball is here, we….”, “When the opponent is here, you….” or “When we see space here, we…”. This is all up to the coach and what he or she is aiming to convey to the players.

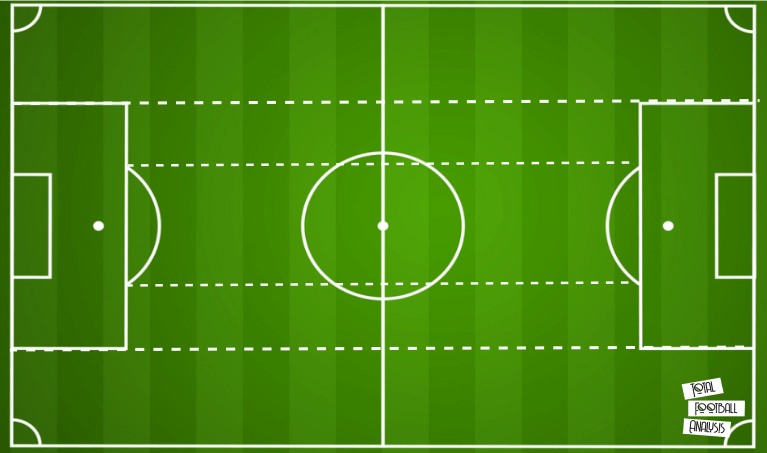

An example of training activity parameters is the use of splitting the playing area into vertical thirds or horizontal thirds. Vertical thirds support a coach in teaching attacking tactics such as switching play, crosses, overlaps and any wide play in general. These parameters can also assist in teaching defensive tactics such as defending in wide areas as well as balance and compactness from ball-far defenders.

A training area split into horizontal thirds can assists coaches in helping players to play through lines and to execute off the ball movements to facilitate penetration. For coaching out of possession, this parameter can help to create a reference point for the positioning of the defensive line and for teaching midfield and forward players when to press as a unit.

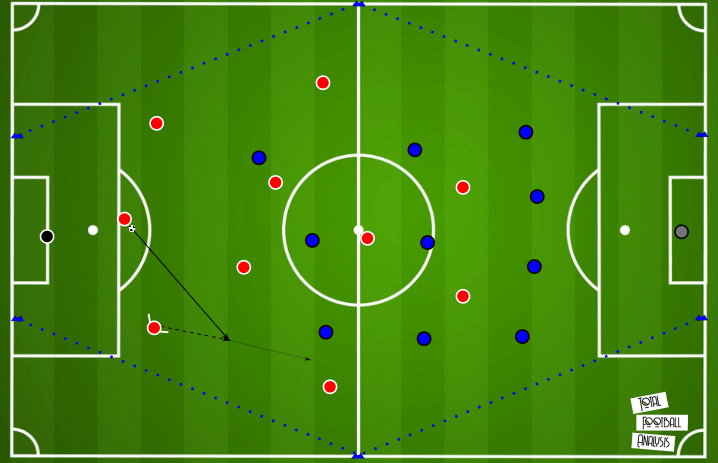

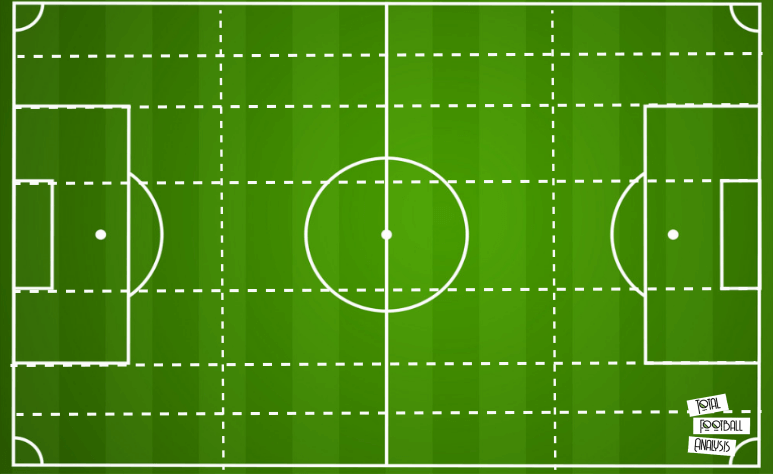

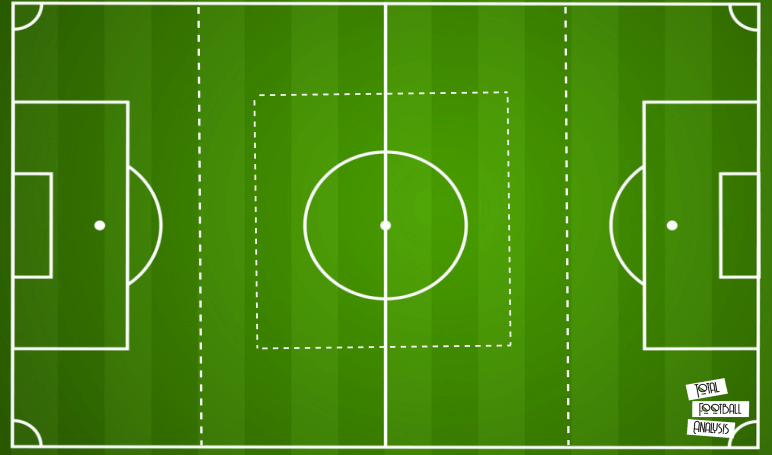

In the realm of elite teams, we can see that managers create pitch parameters based on the primary aims of their game model. Below we can see Pep Guardiola, Julian Nagelsmann, and Antonio Conte’s current training pitch parameters (as observed on Google Maps). We can see that each manager has taken a different approach to create frames of reference for their players.

Guardiola of Manchester City focuses on the use of five vertical channels.

Nagelsmann of RB Leipzig uses a similar parameter format, but also adds additional vertical channels in the flanks and divides the pitch into horizontal thirds.

Meanwhile, Conte of Inter Milan divides his pitch into horizontal thirds and clearly trains with focus on the central area of the pitch.

Task

The most common constraint that coaches use to encourage players to find the desired solution in training is the use of task constraints. Coaches may manipulate rules and equipment of training activities to help convey a training goal. This may seem obvious, but multiple studies have found that a minor task constraint manipulation within an activity can lead to significant changes in how athletes operate within the said activity.

Additionally, an important technique that can be used across the different types of task constraints is the use of exaggeration. By manipulating task constraints to emphasize a particular training problem/goal a concept can become more obvious to the athletes. This helps to encourage the athlete to gravitate the desired learning objective of the activity.

The use of and manipulation of training equipment is an important variable for coaches. By altering things such as the ball (size 1 vs size 5 or size 5 vs futsal), the coach can guide the players towards certain developmental objectives. A small ball is harder to manipulate and forces players to particularly focus on technique and touch when manipulating the ball. Futsal balls, due to being heavier than a regular ball, force players to use more touches to move the ball.

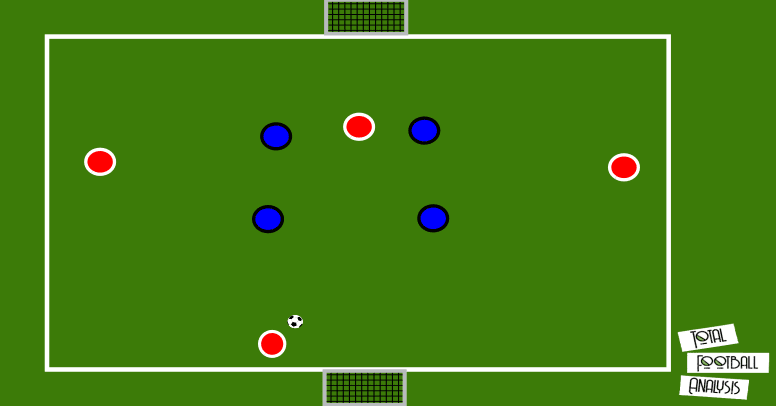

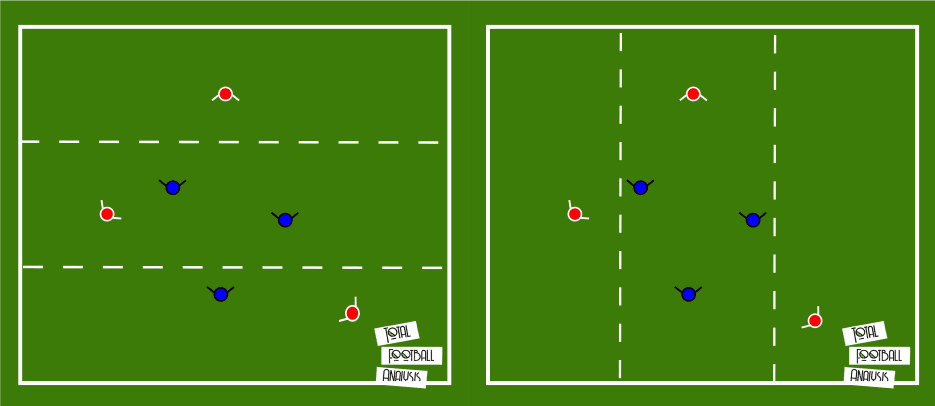

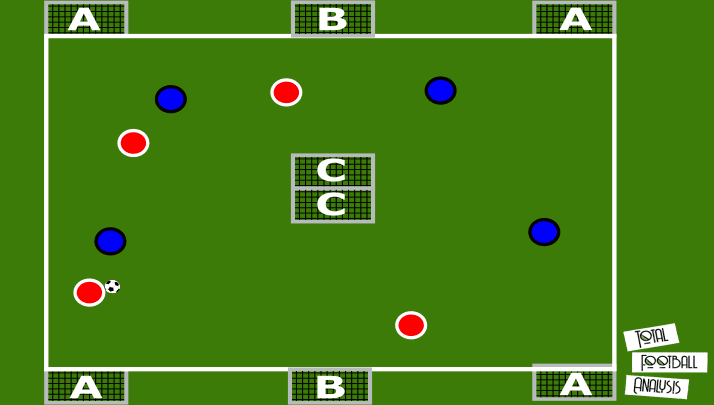

In football, the positioning and sizes of goals within an activity can create major reactions within participating athletes. In the image below, we can see an example of three different types of goal positionings. The “A” goals encourage players to use width in attack and bring many of the same benefits of using a wide pitch. The “B” goals encourage directness of play. The “C” goals can be used to disrupt players and encourage more attention to exploitable space on each side of the goals.

The size of a goal is also a powerful tool in creating desired reactions out of players. If a goal is small the players are forced to penetrate closer to the goal to create a scoring chance. Depending on the activity format, this can be used to guide players into more 1v1 situations or combination plays with nearby teammates.

On the other hand, a large goal invites players to shoot from farther away. This, in turn, forces defending players to pressure the ball more quickly to not allow attackers a shooting opportunity. This shows us that the size of goals used in activities directly affects how both attackers and defenders will play within that activity.

Rule manipulation is debatably the most commonly used type of task constraint. The types of rule changes a coach may use in a training environment are limitless. Point incentives for specific actions are a particularly powerful constraint because they do nothing to take away the game-like realism of the activity and uses positive reinforcement to guide the players to the desired playing style.

We can see the use of rule manipulation at the elite level in a few formats. Pepijn Lijnders (Liverpool’s assistant manager) was once asked about how Liverpool create and maintain their culture of intensity in their training sessions. He replied with a story about their 5v2 rondos. “It’s actually called Milly’s rondo now after I got inspired by James Milner because he always intercepted the ball within the first few passes. He was really quick and brought the focus of the rondo to another level. I was like: ‘How can I come up with a rule that everyone will execute with his kind of intensity?’ So I gave an extra incentive for the two players in the middle if they would intervene within the first six passes.”

We can see that seemingly minuscule rule changes like this in a training rondo can help to create massive changes in team culture and intensity on the pitch.

Maurizio Sarri has also been known to extensively use task constraints within his training activities. In Sarri’s UEFA Pro thesis in 2007, he listed the following task incentives in his training scrimmages. “three touches with a goal at the first touch”. “goal double if the ball is from a lay-off”. “goal triple if the ball comes from the lay-off sought directly from those who have regained the ball”. “All players must be in attacking half when goal is scored”. “Goal twice as a member of the defending team is still in the attacking midfield”.

By looking at these five task constraints, we can see directly into Sarri’s game model. Three touches per player with one-touch goals, which helps to maintain a quick attacking tempo. Goals worth double from lay-offs encourage quick combination play in the attacking third. Goals worth triple from layoffs from those who won the ball show us that Sarri clearly emphasized quick and direct attacking transitions with combination play from nearby players. The last two task constraints show us that Sarri desires his team to move forward in attack as a compact unit and punishes his defending units if they do not create compactness and put players in between the ball and goal.

Conclusion

The use of constraints is a powerful tool for a coach no matter what age or sport they are coaching. If a coach is able to identify all the possible constraints that can influence his squad’s performance, a type of playbook can be created. The number of constraints to be used are hypothetically infinite. It is up to each coach to take the time to use tactical analysis to observe, define and execute what they think is appropriate for their players.

This is a very topical overview of the constraints-led methodology. If you would like more resources or information, I encourage you to reach out to me on Twitter (@TheJoeyJenkins).

Comments