Counterattacking is the quick transition from defence to attack with the aim of exploiting the opposition when they are at their most vulnerable. The tactic has been treated with increasing importance in modern football. Once perceived as an underdog’s best chance of success, it is now a fundamental tactic that all top-level teams incorporate into their game model.

Using the Premier League as an example, both shots and goals created from counterattacks rose significantly in season 2022/23. For several years, coaches have recognised the importance of counterattacks throughout top-level football. Defensively, teams now set up their defensive organisation when they are in possession to minimise the chances of being countered. From an attacking standpoint, they now work thoroughly on trapping or dispossessing teams and launching counterattacks with predetermined movements.

This tactic is now no longer confined to lower-positioned teams, sitting in a low block and launching rare attacks. The top three teams for scoring from counterattacks in the Premier League in the 2022/23 season all finished in the top five. Manchester United scored 10 of their 58 goals (17%) from counterattacks, while Liverpool and Manchester City scored seven each.

This tactical analysis will focus on counterattacks starting in the attacking teams’ own half. It will analyse the key components that make for a successful counterattack. This analysis will also offer suggestions on how coaches can implement this tactical theory.

Pinning the defender

The key to defending counterattacks is to delay the play and allow recovering players to regain their position. For the attacking team, the opposite is true. They need to attack at a speed that makes it impossible for the defending team to recover their shape. Along with speed, certain traits increase a team’s chances of completing a successful counterattack.

When the attacking team is running at the opposition’s backline, one such trait is to pin one defender in place. This is done by dribbling directly at the defender, committing him to engage with the ball. Often in these scenarios, it is the players’ instinct to attack the space down the side of the defence. This takes the ball further from the goal and, more importantly, allows the defence to shift across towards the ball.

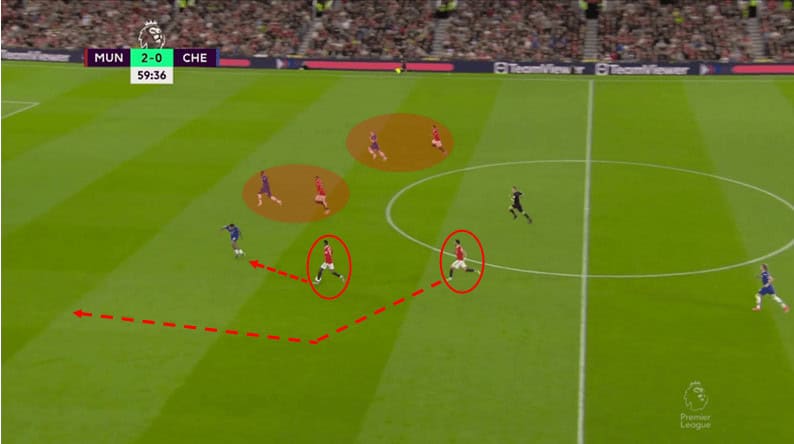

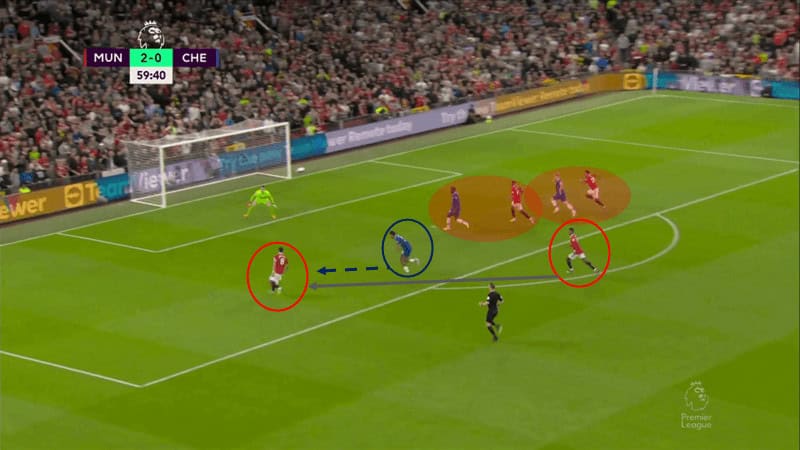

Running into space may be an option for a player with extreme speed. A fast player may be able to outpace his direct opponent. The majority of the time, though, the best option is to keep the widest defender pinned so a teammate can run into the space. The above image shows Marcus Rashford, having picked the ball up in his own half, running directly at Chelsea’s side centre-back. He is supported by Bruno Fernandes, who is about to make an overlapping run.

In addition to Rashford pinning the ball-near centre back, Manchester United have managed to occupy all the other defenders. This is not always possible, but when teams counter with enough players, it prevents the opposition defenders from shifting to cover each other. This also, vitally, gives United an overload when Fernandes becomes involved in the attack.

The centre-back (circled in blue) tries to delay Rashford as long as possible, giving his teammates a chance to regroup. However, when Rashford is within shooting distance, the defender is forced to close him down. At this moment, Rashford can pick his pass to the supporting Fernandes. Although Fernandes elected to cut the ball back, he received it with a clear sight of goal and with the ball-near defender scrambling to get there.

Positioning and movement of the striker

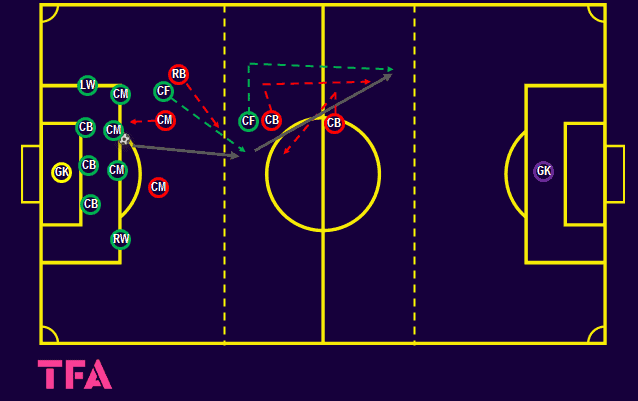

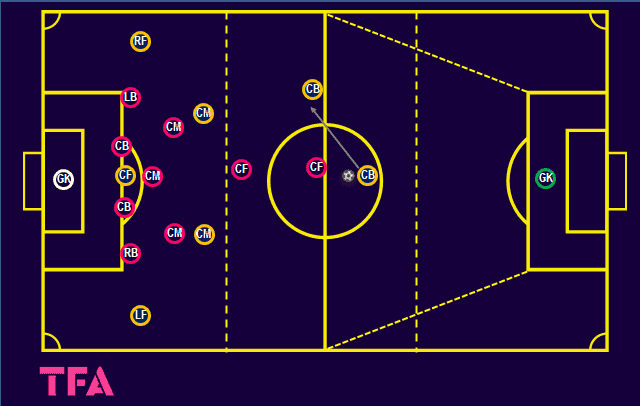

Another critical component of a counterattack is to have at least one player ahead of the ball who can disrupt the opposition’s rest defence. The above tactical diagram is an example of Hibernian’s game against St Mirren in the Scottish Premiership. This counterattack resulted in Hibs’ first goal of the match.

At that moment, Hibs were in a low block defending a throw-in. The diagram shows the positioning of St Mirren’s lowest five players; the rest were in or near the box. When ball possession changed hands, the ball-near midfielder’s reaction was to counterpress to prevent Hibs from escaping their box. With good individual awareness and the planned positioning of their forwards, Hibs excellently escaped their own third.

The ball-far centre-forward (closest to the halfway line) positioned himself 10-15 yards directly in-front of the ball-near centre-back. This meant the ball-far centre-back, who wanted to closely mark the striker, was also positioned directly in front of his teammate. The two centre-backs being in a straight line left lots of space on either side of them that Hibs devastatingly exploited.

As Hibs regained possession, the highest forward, Christian Doidge, peeled off to the wide-area showing for the ball. He was tracked by his marker whilst the other centre-back initially moved across to cover his defensive partner. This created a gap between the edge of the box and the halfway line. Hibs used this large area to play in the deeper forward.

Hibs’ deeper central forward, Adam Le Fondra, then played in his strike partner deep into the opposition’s half, splitting the centre-backs with his pass. With both centre-backs on their right side of the pitch and focusing on the ball, they were unable to cover Le Fondra’s run towards the edge of the box. Doidge was able to find Le Fondra with an early cross that took all the recovering defenders out of the game.

Every Hibs touch in the build-up of this goal was forward, with two passes and the finish being one touch. The speed and the cleanness of the move gave the opposition no chance to recover.

Relative width

The above image is from the moment after Manchester United performed a similar striker movement as Hibs in the previous section. It shows United’s most advanced forward providing width but remaining inside the width of the box. This is a common theme for Erik ten Hag’s team’s counterattacks, often with three players, across three different vertical zones by the width of the box.

With the closest defending player no longer moving wider at the same rate as the attacker, there is no need for the forward to move any wider. He has already created enough relative width from the defender that he can comfortably receive the ball. If he were to move any wider, he would be less of a threat, and receiving the ball would not have to affect the centre-backs positioning.

Counterattack practice

Counterattacks from deep positions require high-speed and long-distance sprints. To avoid injury, the players’ warm-up should replicate these long sprints as closely as possible. An unopposed attacking pattern could bridge the gap between the warm-up and the competitive conditioned games that follow.

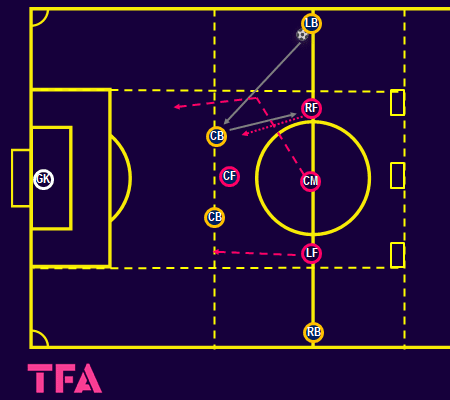

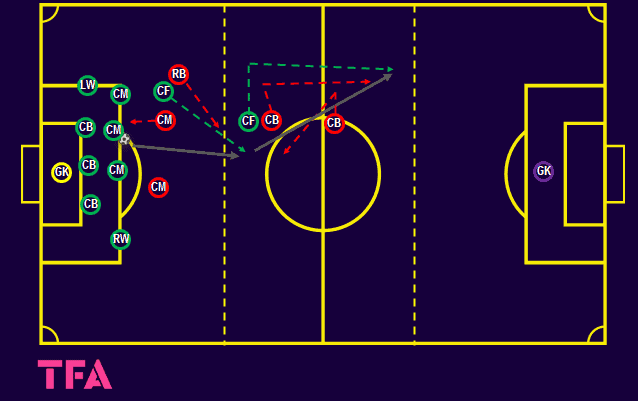

The above counterattacking exercise has the yellow team start with the ball. They should move the ball along their backline, with the pink team moving in relation to the ball (within the middle zone) without intercepting it. After several passes, the yellow team should deliberately concede possession to the pinks, who then launch a counterattack.

The receiving pink player’s first action should be forward and without delay. As soon as this first touch is taken, the drill becomes live with four attacking pink players attacking the two centre-backs defending the big goal. To create a sense of urgency and speed up the attacking play, one or both of the full-backs can be allowed to join the defence from the wide area.

If the defending team (yellow) regain possession, they attack towards the small-sided goals. These goals area positioned across the central area to reinforce the importance of protecting the middle of the pitch during counterattacks.

The counterattacking players should be encouraged to drive with the ball at defenders to pin them in place. They should also be coached to recognise triggers for their supporting movements. For example, and as shown above, an inside-the-pitch first touch from one of the wide players should invite the central midfielder to overlap.

A progression could be for the counterattacking team to play into the striker before making supporting movements. The first pass into the striker can be live, making the forward think about his positioning and how to get on and protect the ball.

Low-block conditioned game

This conditioned game begins with one team (pink) defending their own box in a low block. The opposition begins the play at the halfway line and attacks freely towards the goal. If the pink team regains possession, they must counterattack towards the opposite goal. When entering the opposing half, they must remain within the angled sidelines. The sidelines in the attacking half are angled to encourage players to keep relative width and attack directly towards the goal.

This game can be played as an 11 Vs 11 or with the numbers reduced to increase the chances of a counterattack occurring. In the diagram above, numbers are reduced on the initial attacking team to increase the chances of a turnover of possession. This creates more opportunities to practice the counterattacking portion. The pitch length can also be adjusted to suit the number of players involved and for the physical demands the coach requires. Conditions on the game, such as a “shot clock” or only allowing a certain number of backwards touches, can be introduced to encourage faster play.

The counterattacking team’s positioning, especially that of the forwards, should be coached during the defending phase. This makes sure they are in the optimal position to help their side launch the counter.

Conclusion

Speed of play is the most vital component of a counterattack. The quality of the individual’s actions, clean touches, touches in the correct direction, and accurate passes create this speed. Any slow or poor play allows opposition teams more time to regroup.

Players also need the desire and athleticism to get involved with the attack and create overloads. When an overload is created, players must then pin defenders. This makes it harder for them to cover the overload and prevents them from slowing the game down and allowing teammates to recover.

Counterattacking is now a fundamental part of the game for all successful teams and should form a vital part of any team’s coaching curriculum.

Comments