Brazil won the Copa America in 2019, and they are also one of the biggest favourites to win the Copa America 2021. They had a good start in the group stage by topping Group B without a loss, scoring 10 while conceing only twice. They came up against Chile in the quarter-finals, who finished fourth in Group A.

Gabriel Jesus’ red card was one of the big talking points of the match, but apart from that, tactically, Brazil showed their cautious attitude in this competition. Some may think the game was an extremely boring one as chances were limited in the 90 minutes, but Tite believes that this conservative mindset helps Brazil defend better. This tactical analysis will point out four key themes of the games. Despite winning the game ugly, Tite certainly had some good information to take away when preparing for the next game.

Lineups

Brazil made a lot of rotations in the last group match to rest a few key players, who were all brought back into the XI for this game – Neymar, Jesus, Richarlison, Casemiro, Fred, Danilo and Thiago Silva. This is the core group of players who Tite trusted the most in the tournament.

Chile weren’t at their best when playing in a back four in the group, they lost to Paraguay by 0-2 and Martín Lasarte felt changes were needed. They started in a back three against Brazil with Alexis Sanchez back as a starter, partnering Eduardo Vargas as the two strikers. Meanwhile, Tomás Alarcón was replaced by Erick Pulgar at the midfield, while Sebastián Vegas was the extra centre-back.

Brazil’s cautious positional setup

Brazil’s centre-back, Silva is 36 years old, and so he would struggle if there were too many transitions in midfield while the full-backs were high and wide all the time. Therefore, the core idea of Tite was to establish a setup that could release the potential of Neymar without taking huge risks. This rather cautious positional setup of Brazil helped them to move the ball smoothly and dictate the tempo of play in possession easily.

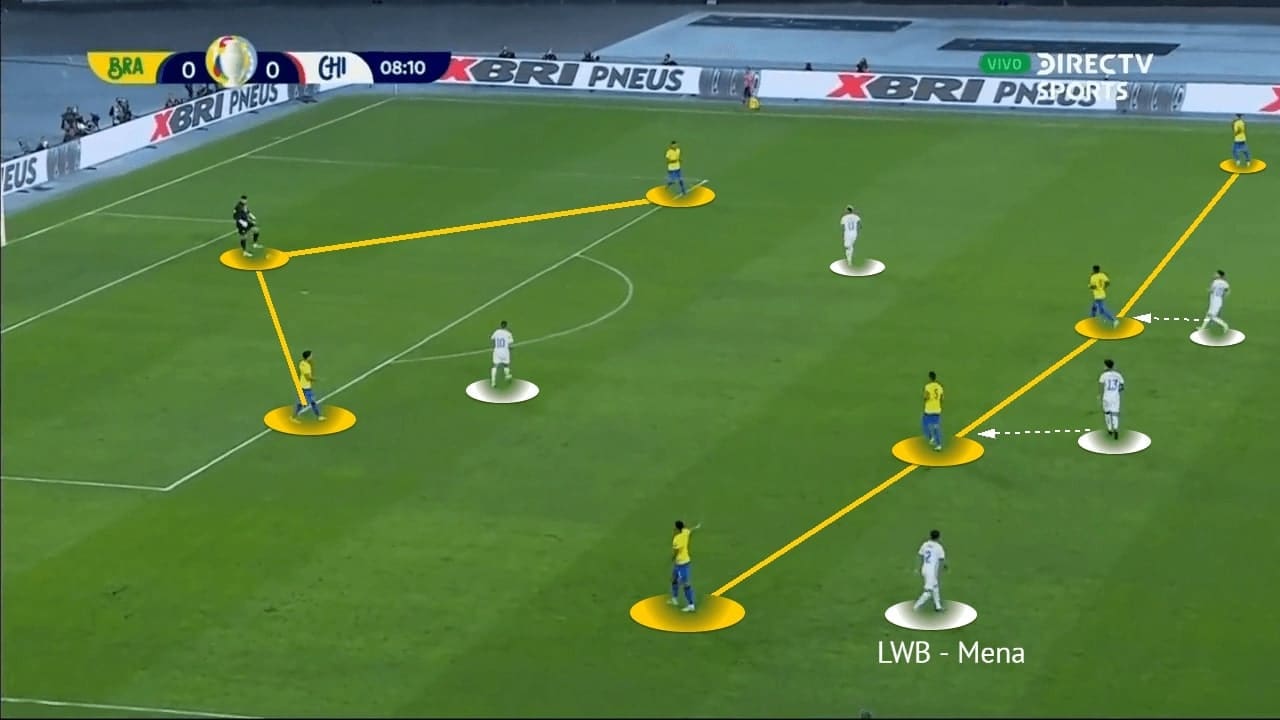

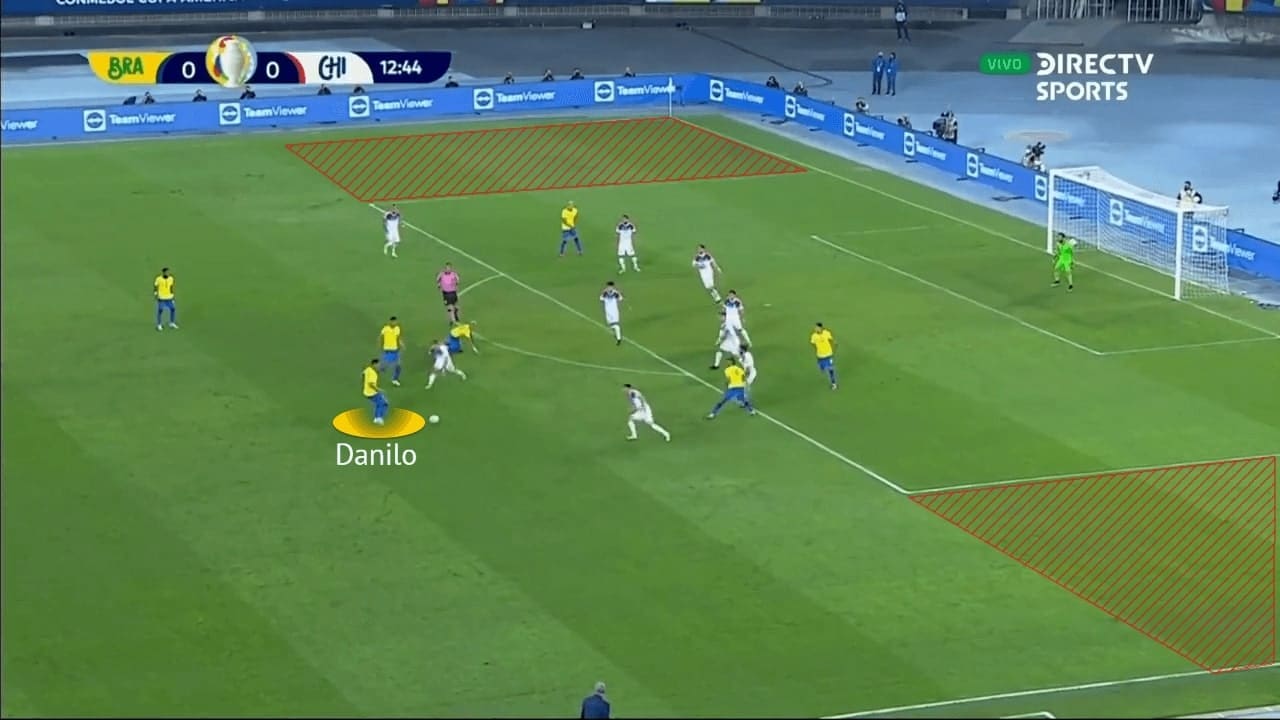

Chile wanted to press energetically by committing the front five of their 5-3-2 shape high up the pitch. They pressed in a man-oriented manner at one side to make spaces small, then attempted to win the ball back with the help of the wing-backs coming high. The above image shows they successfully had a 5v5 numerical equality on Brazil’s right half, but their opponent did not suffer because of the use of the goalkeeper Ederson.

In the build-up, Tite trusted Ederson’s kicking ability and he was a part of the structure. The Manchester City goalkeeper has been trained to play under pressure for years and he often made good passing decisions. He confronted the pressure from the Chile strikers in this situation but calmly played the ball to Silva, helping Brazil to reach the free half, having evaded the pressure.

With Ederson in the team, Brazil could create numerical overloads easily to achieve superiorities in the build-up. Against a 5-3-2 pressing shape, Ederson could form a back three with the centre-backs to create a 3v2 overload. If the strikers matched the centre-backs, the City goalkeeper could exercise his top-class long passing skill to find the attacking players, or being the short player to break the first line.

Therefore, Fred and Casemiro did not have to drop into the defence to create the 3v2 overload. Their task was to drag the Chile midfielders out of position, stretching the block vertically, so the likes of Neymar and Firmino had more spaces to play against the defenders.

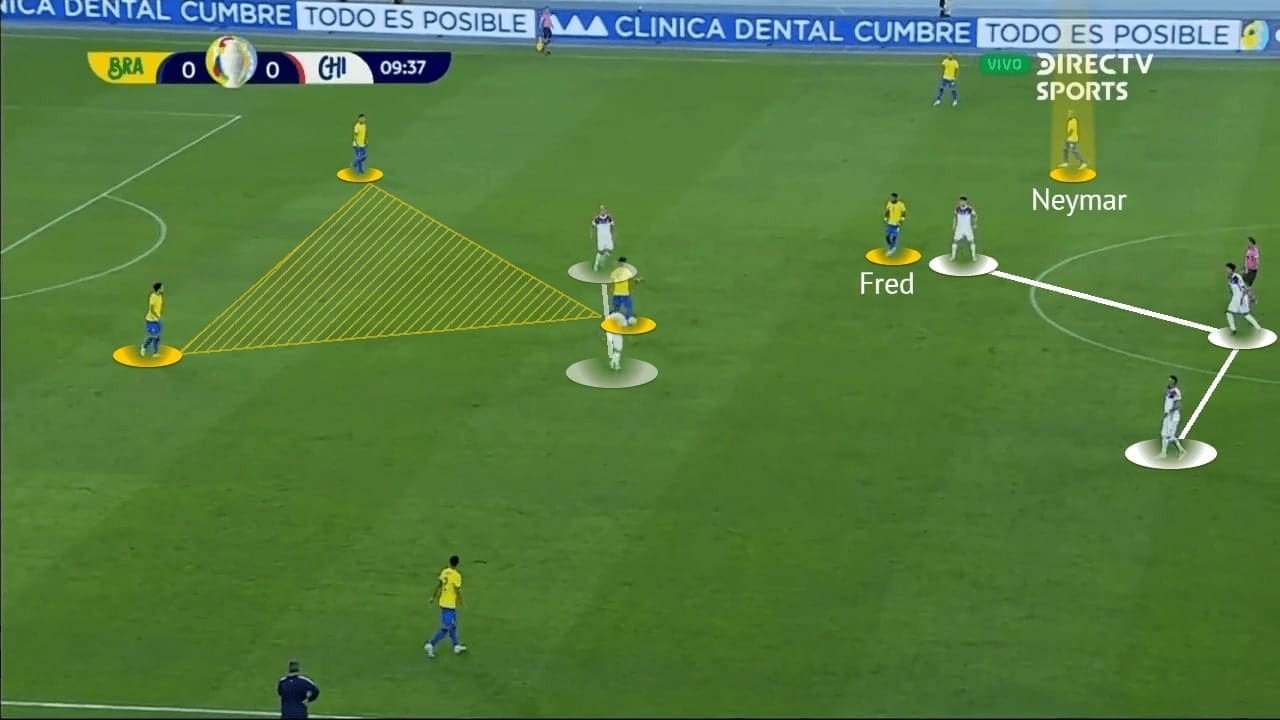

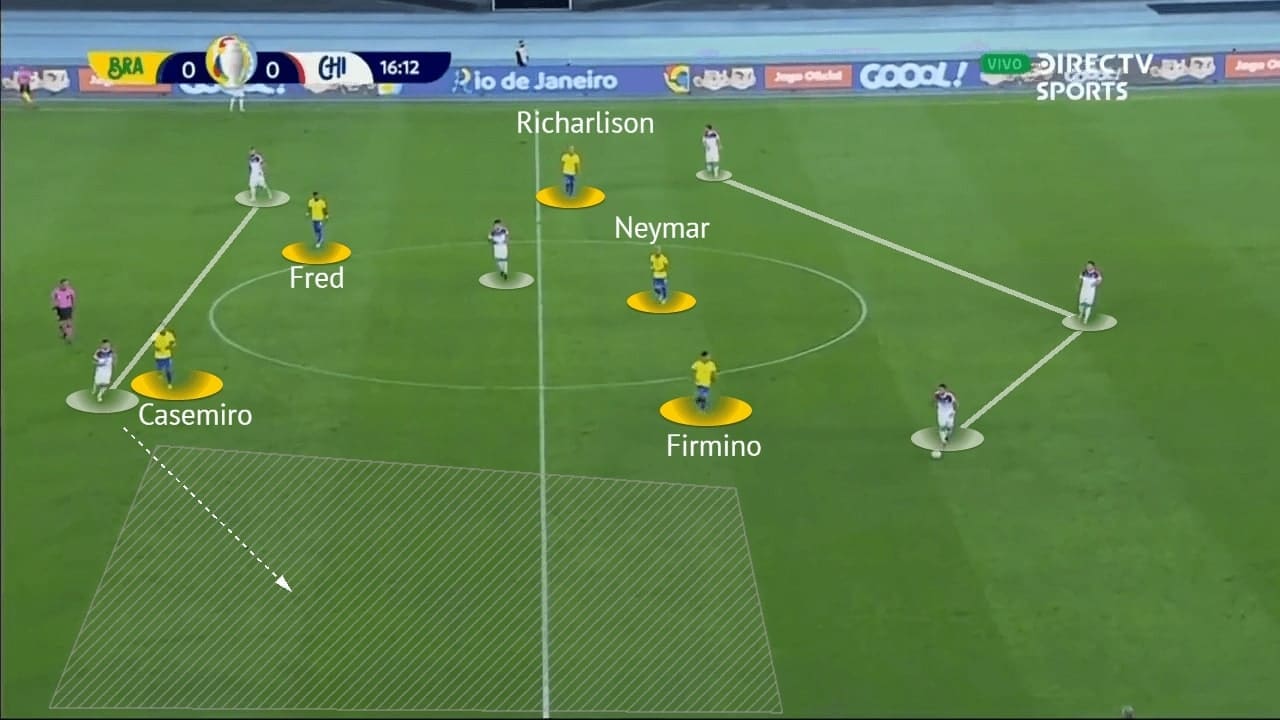

The above image shows Brazil’s positional structure with the above tactics, the shape was a 3-4 and it was impossible for Chile to press them with the defensive line in their own half.

As the game went on, we also see several variants of Brazil’s shape to allow them to play out from the back step by step. The core ideas were the same but the way to represent the ideas were a bit different.

In the above screenshot, the shape of Brazil became a 2-1-4 as Neymar also dropped deeper. Firstly, the 2-1 shape was also creating a 3v2 numerical overload over the strikers, but Casemiro’s positioning can fix the height of the first line, so the centre-backs had more spaces to pass.

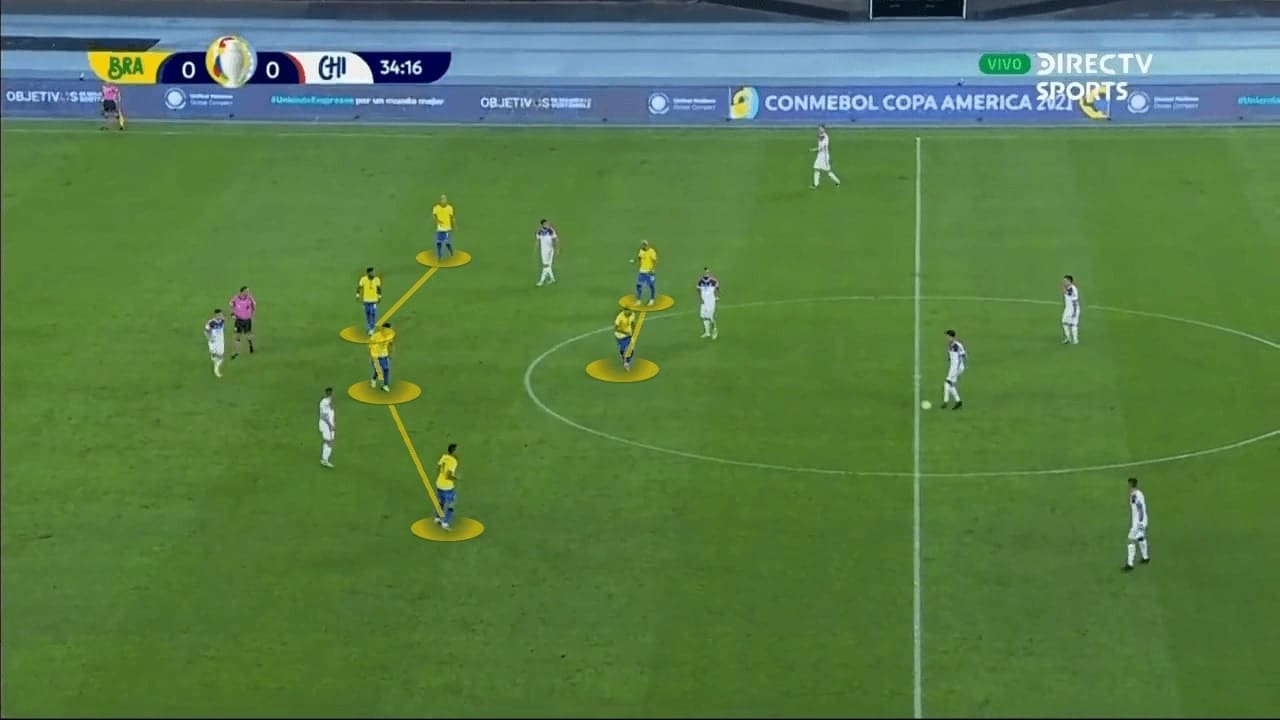

Although Fred and Casemiro might not be touching the ball in the process of construction, their presence were vital as the positionings of Chile midfielders were fixed because of them. For example, Fred pulled Charles Aránguiz into the centre so Chile were only defending the central zone. Neymar, at the left half-spaces, became the free player to receive as Francisco Sierralta was reluctant to leave his partners.

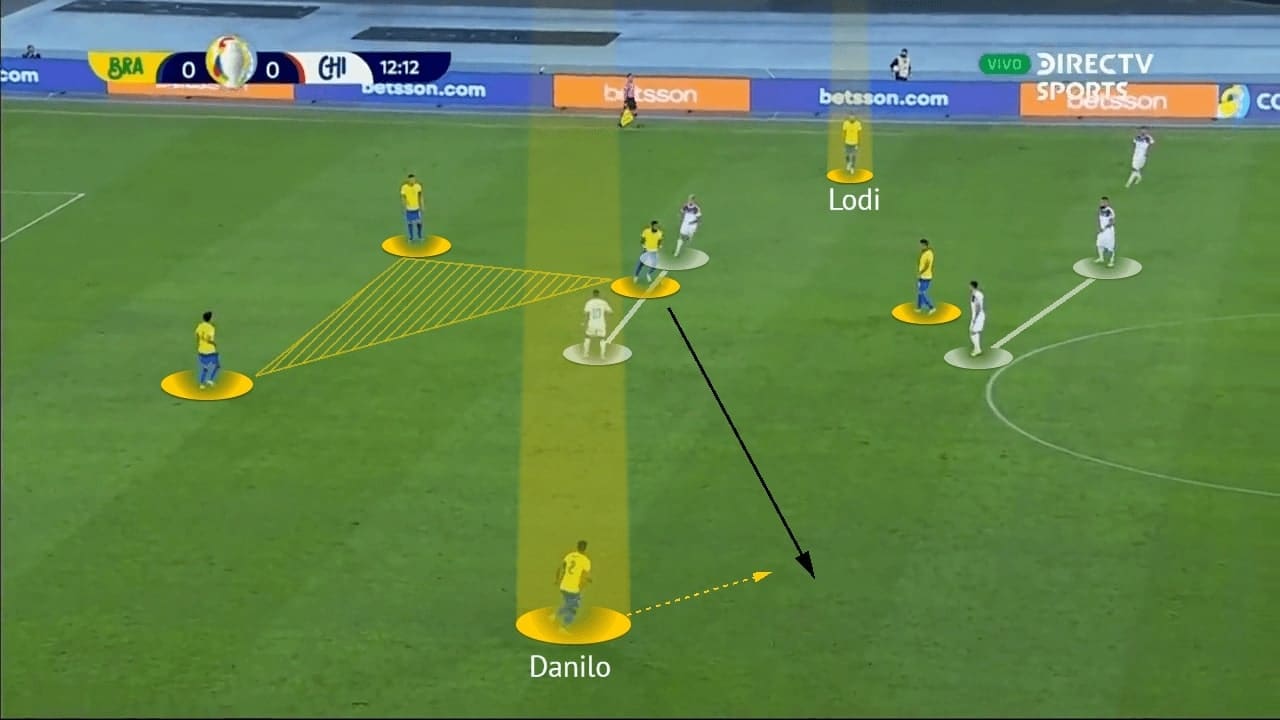

Brazil’s full-backs were also a key part of the setup. Instead of pushing very high to attack flanks, both Renan Lodi and Danilo stayed very deep in the build-up. By using the wingers to pin the Chile wing-backs, Brazil’s full-backs were usually free from pressure.

Tite did not want his full-backs to stay at the touchline as there won’t be enough angle to pass out wide. Placing them closer to the centre could connect the build-up players, so Danilo could receive from midfielders or centre-backs without dropping and closing his body.

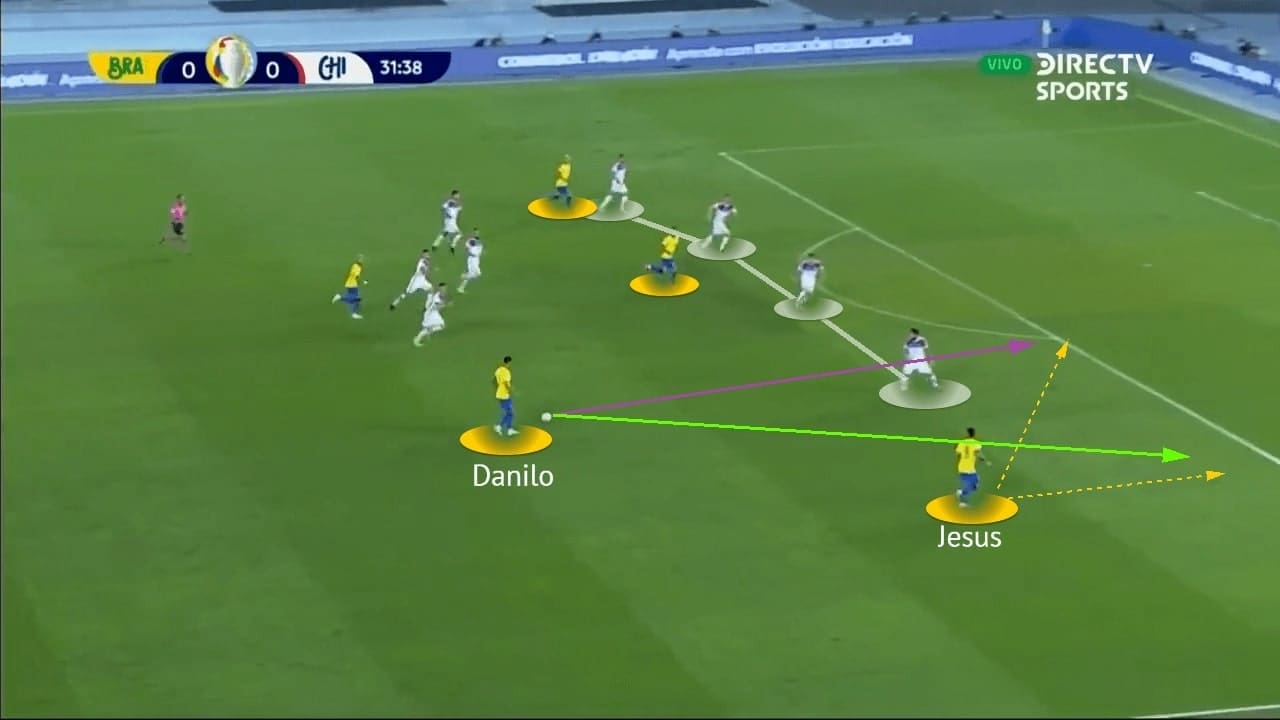

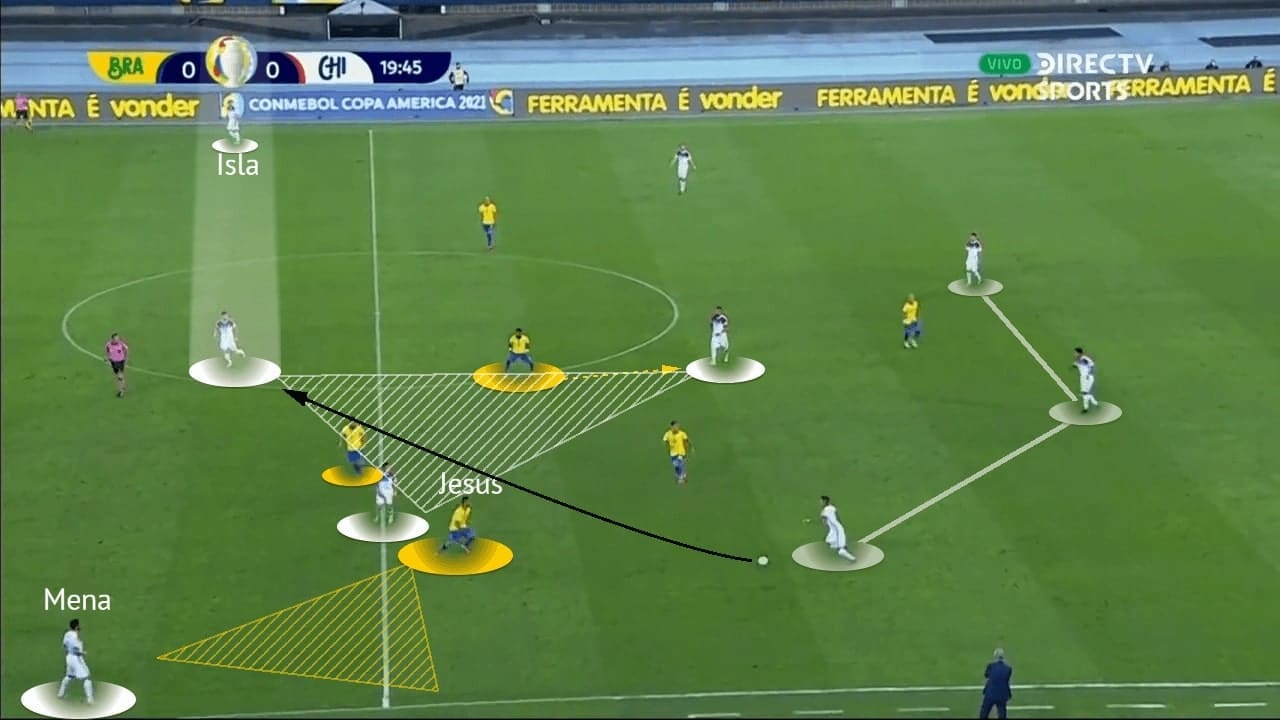

Here, Brazil still had the 2-1 structure to overload the strikers. When Mauricio Isla marked Lodi high on the left, Eugenio Mena must stay deeper to prevent the centre-backs from exposing against Brazil’s front three. Consequently, Danilo was unmarked, he did not wait for the ball at the touchline, but going inside to open a diagonal passing lane for Fred. Since the Brazilian midfielders kept the Chile second line the centre again, the Juventus right-back was free to bring the ball forward at the right half-spaces (strategically better than staying out wide as Danilo had more options to pass at the inside).

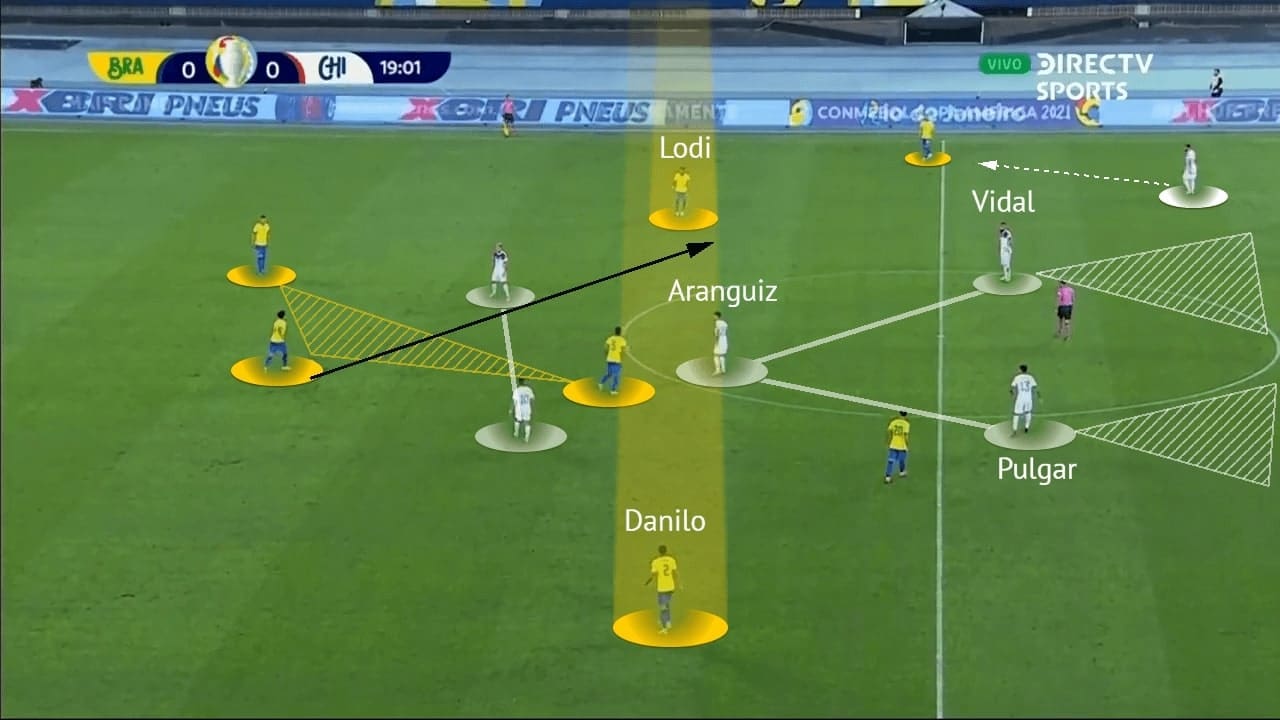

The same situation could also happen on the left flank. The above screenshot gives a clearer image on Tite’s positional strategy to create the free players in the build-up. We have the same elements: 2-1 shape, narrow wing-backs, Chile’s 5-3-2 midblock again.

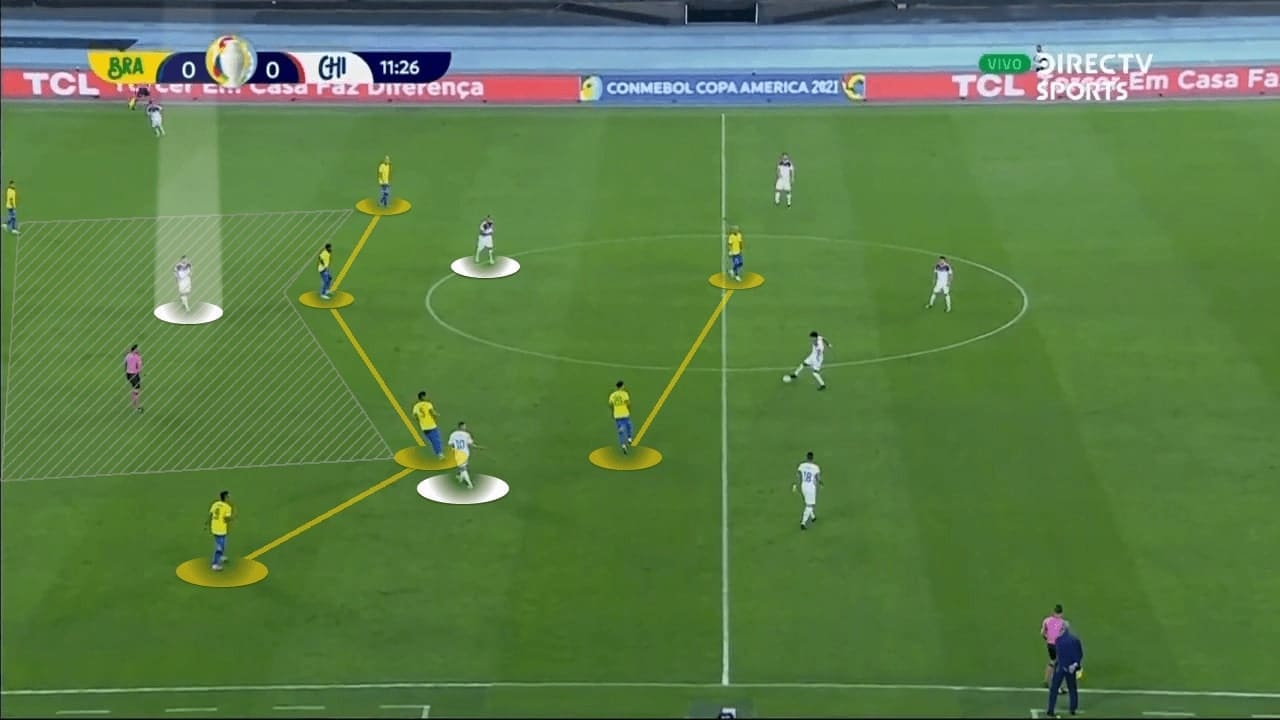

Brazil’s full-backs did very well to stretch the minimum width at the build-up, they just only had to occupy both half-spaces as the wingers were providing the width in the second phase. In the example, Marquinhos had spaces to pass as Casemiro’s positioning kept the defence deeper a little bit. This time, Lodi was the free player to receive as Inter midfielder Arturo Vidal could not mark him in advance. It was always a decisional dilemma for the Chile midfielders as they needed to cover spaces in front of centre-backs, or else Neymar would tear them into pieces. But the central positionings of midfielders also left the inverted full-backs uncontrolled.

And, look at the top of the image. Isla would not be pressuring Lodi as he was occupied by Richarlison at the touchline already. Brazil roughly had a 6v5 overload in the central zones to in the second phase.

And that’s why they struggled in the final third

Although the narrow full-backs helped Brazil to reduce the transitions as much as possible, but there was an issue: lacking the provision of width. This was the biggest problem that prohibited Tite’s men from creating high-quality opportunities. They struggle to stretch the backline horizontally to open gaps or create isolations.

After playing under Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City and Andrea Pirlo’s Juventus, Danilo developed into an all-rounded full-back who could also play at the centre. In this game, he often played centrally and arrived at half-spaces in the final third. Brazil had an extra midfielder at the rest defence to kill the transition threats.

However, lacking the provision of width also made Chile easy to defend. In this image, Chile had nine outfield layers at the central zone while Brazil had seven. Intriguingly, both zone 16 and zone 18 were totally opened without any player. Lasarte’s men could remain in a compact block to make the channels between defenders as narrow as possible – no through pass was allowed, no spaces between the lines were available.

Here comes another example of Brazil lacking the width in the final third. Apart from allowing the oppositions to defend in a compact shape, spaces for the narrow wingers to dribble were limited as well.

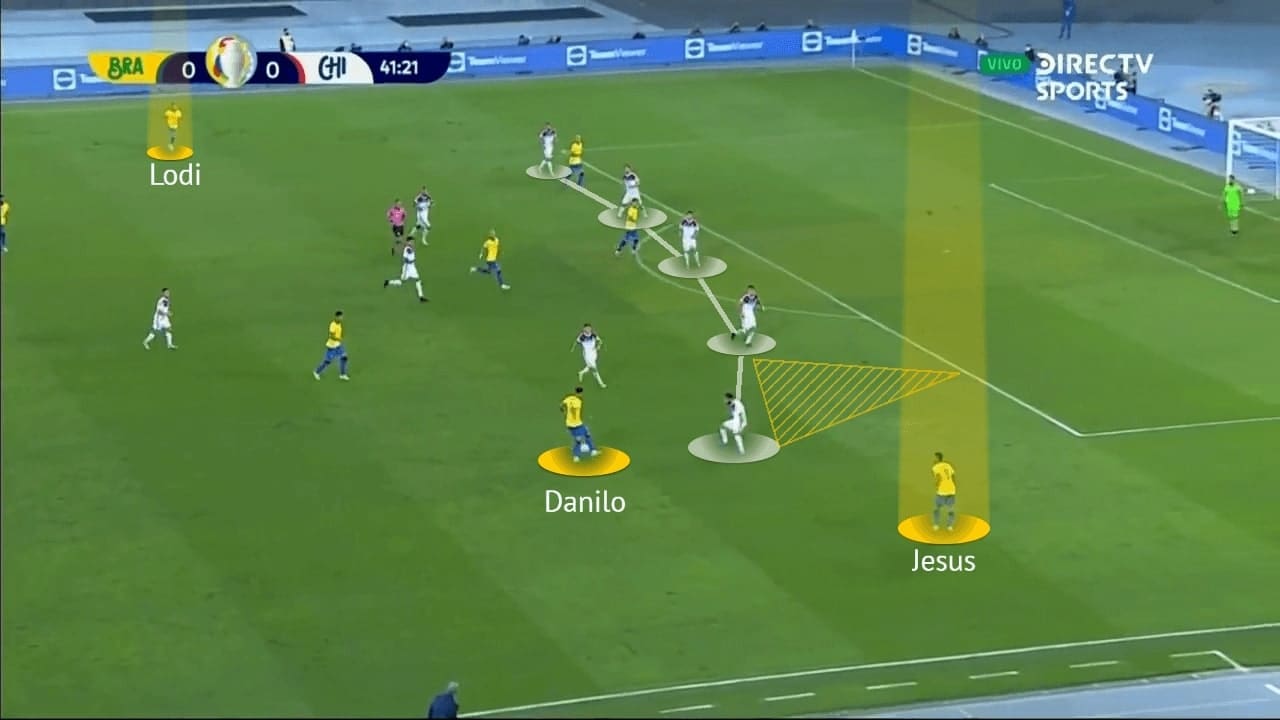

Again, Danilo drove into the offensive third through the half-spaces channel, but the through pass was very difficult to play. In this case, Jesus did not have the room to run. If he dashed forward and Danilo used the green route, he would be offside. If Jesus tried to get behind the defenders diagonally, he would be receiving on his left foot while the gap to pass was too narrow. Without stretching the backline, Brazil struggled to play into the passing channels of Chile.

Therefore, we saw Tite made a tactical tweak to ease the problem. After half an hour, Brazil got more width providers on both sides as Lodi was given greater freedom to come up high. Also, Jesus played a bit wider to give Brazil an option outside, and so Danilo could keep his original role to help Brazil controlling the game.

The above image shows a slightly different situation in Brazil’s final third attacks. The width was now provided by Lodi and Jesus simultaneously, while Danilo remained at the half-spaces. As a result, the Chile backline was a bit stretched, passing channels and gaps were more obvious – such as the spaces behind Mena and Vegas would be opened when the left wing-back pressed Danilo.

Adaptation to Chile’s attack

Defensively, it was rare to see Brazil staying in a block and compact shape in South American competitions. Tite’s initial defensive plan faced some issues when Chile were organizing the attacks, but Brazil were very adaptive to solve the problem after several changes were made.

Chile used a 3-1 shape in general, against a Brazil team that used a 4-4-2 block to defend, they also dropped Sanchez with the midfielders to create a 7v6 numerical superiority as shown in the above image.

Since Brazil did not apply tremendous pressure on the ball, the build-up players were comfortable to move the ball around in general. With a back three, a 3v2 numerical overload at the first line was created easily. The strategy of Lasarte was to exploit spaces behind the Brazil midfield line. Since they had Aranguiz and Vidal at the centre, these two players could draw Casemiro and Fred out of position, then no Brazil were stretched vertically as Vargas occupied both centre-backs.

There are some variants from Chile’s shape. One of them is pushing the left wing-back very high to create wide spaces at the midfield. Brazil’s right-winger: Jesus was defending in a man-oriented manner initially, when Mena went high, he would be following him tightly, so you could see only five yellow shirts remained at the image above.

The numerical advantage was the same: Chile overloaded Brazil in a 6v5 but spaces they used were a bit different. Usually, Vidal would drop into spaces vacated by Mena, creating a decisional dilemma for Brazil’s midfielders – stepping out or not to cover him? If Casemiro went wide to mark Vidal, spaces in front of Brazil centre-backs were opened. If not, Chile could develop the attack without any pressure from flanks.

The above situation has most strategies of Chile’s offensive plays. They still played out from the back with a back three, and Jesus could not press Vegas because Mena was fixing his focus at the wide zone. Meanwhile, Firmino was destined to be late on the wide centre-backs as the players would never match the speed of the ball when the attack shifted.

Again, both Fred and Casemiro were drawn out of positions by the Chile midfielders. Now they just need to exploit the 3v2 overload at the midfield and find spaces behind the second line.

As the game went on, Tite’s men were able to nullify the tactical advantages of Chile. Jesus switched from a man-oriented defending to a more zonal one. Now, he covered the central spaces, stuck compact as a unit with teammates to block the centre. It made all passing channels between players small, and the oppositions could not play the pass through the gaps.

In the above image, Brazil defended in a more solid 4-4-2 structure with the strikers dropping deeper. Now, they had better control over Aranguiz and Vidal as the vertical distances of lines reduced. Brazil’s defence improved so on but the red card of Jesus forced them to defend even deeper in the remaining minutes.

Final remarks

In national games, teams rarely learnt all tactical concepts of head coaches as the time to train was very limited. Usually, teams played with cautious tactics as the costs of mistakes were too high in the knockout stages. Didier Deschamps’ France won the 2018 FIFA World Cup with a conservative setup, and even Brazil possessed so many talented players, they were also prioritizing clean sheets instead of scoring many goals.

This analysis pointed out the positives and the negatives of the positional structure of Brazil. With the ball, Tite’s troops largely controlled the game and kept minimal turnovers at the midfield. Nevertheless, there were also problems that needed to be solved in the coming games, including their attacks in the final third and to replace Jesus. We should expect Tite to reveal his solutions in the semi-final days later.

Comments