This edition of the Copa America has been dogged with problems and issues for months, with matters coming to a head in the weeks leading up to the tournament when it was confirmed that Colombia would no longer be able to host the tournament. Argentina stepped in instead, but they too had the hosting rights taken away due to the rising number of COVID-19 cases in the country. It was finally announced that Brazil would host the 2021 Copa America, which was greeted with a lot of bemusement and confusion, if we’re being polite, since Brazil is in the midst of a devastating surge of the virus as well. While the merits and demerits of those decisions can be debated for a long time, the tournament did finally manage to kick off to give CONMEBOL some sort of relief as it aims to align the Copa with the European Championship hosting cycle, making this the fourth Copa America tournament in just six years.

Brazil, the hosts, kicked things off with a relatively comfortable 3-0 win over Venezuela – it must be mentioned here that Venezuela were without eight members of their squad due to positive COVID-19 tests and had to call up 15 players on the eve of the tournament. Nevertheless, there were some interesting structures and principles used by Brazil in this match, which we will attempt to understand and explain in this tactical analysis piece.

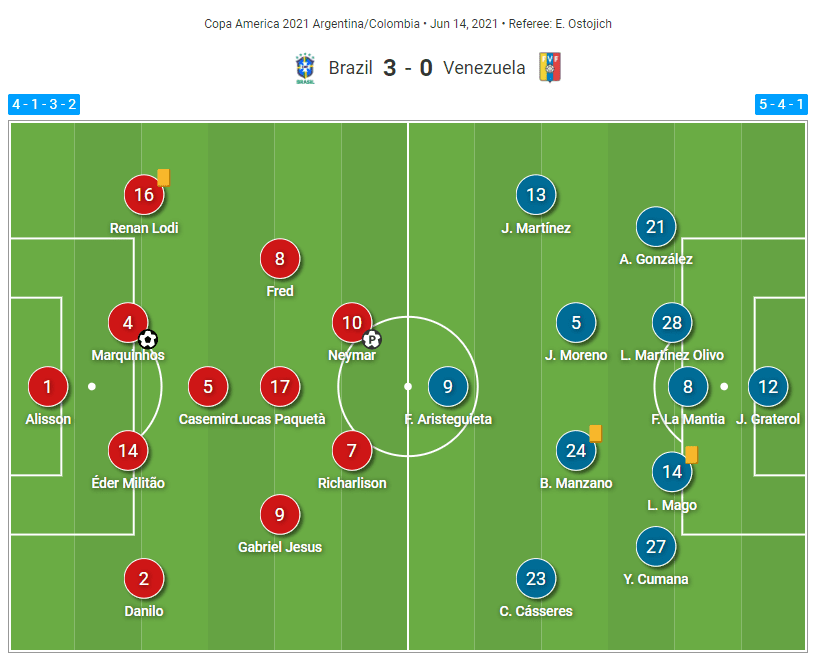

Lineups

Tite sent the side out in a lopsided 4-4-2 diamond of sorts – Danilo and Renan Lodi were the starting full-backs, with Casemiro as the holding midfielder and Fred alongside him. Lucas Paquetá played as a floating playmaker off the right flank, where Gabriel Jesus was used as an old-fashioned right winger, and Neymar and Richarlison formed a front two. Lodi and Paquetá were replaced by Alex Sandro and Everton Ribeiro respectively at half-time, while Gabriel Barbosa came on for Richarlison after 65 minutes and scored the third goal two minutes from full-time.

Venezuela were in a pretty deep and conservative 5-4-1 shape, which is understandable given their issues with COVID-19. The likes of captain Tomás Rincón were ruled out due to this, while Darwin Machis and Salomon Rondon, among others, were unavailable due to injury.

Brazil use width and depth to penetrate

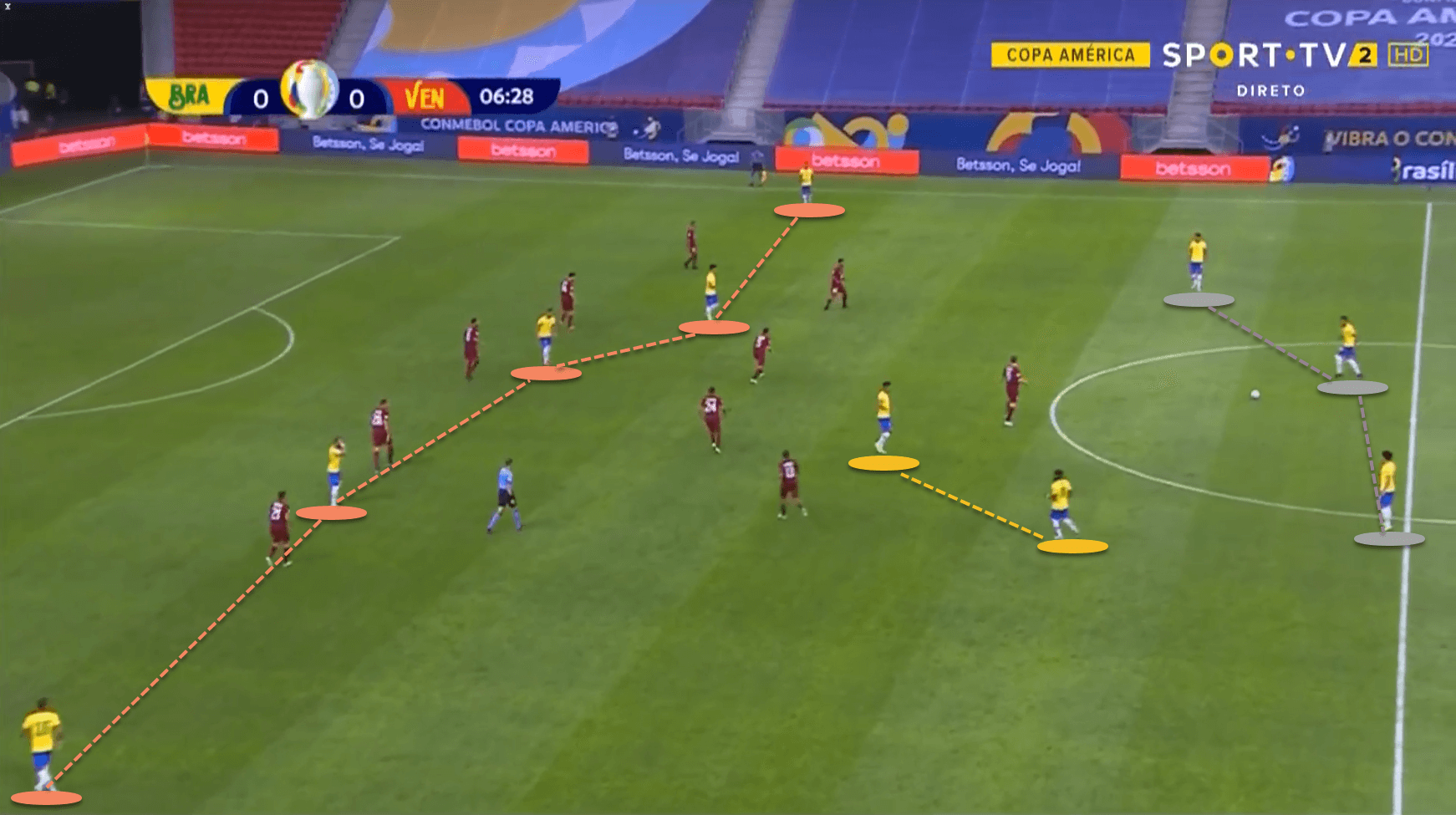

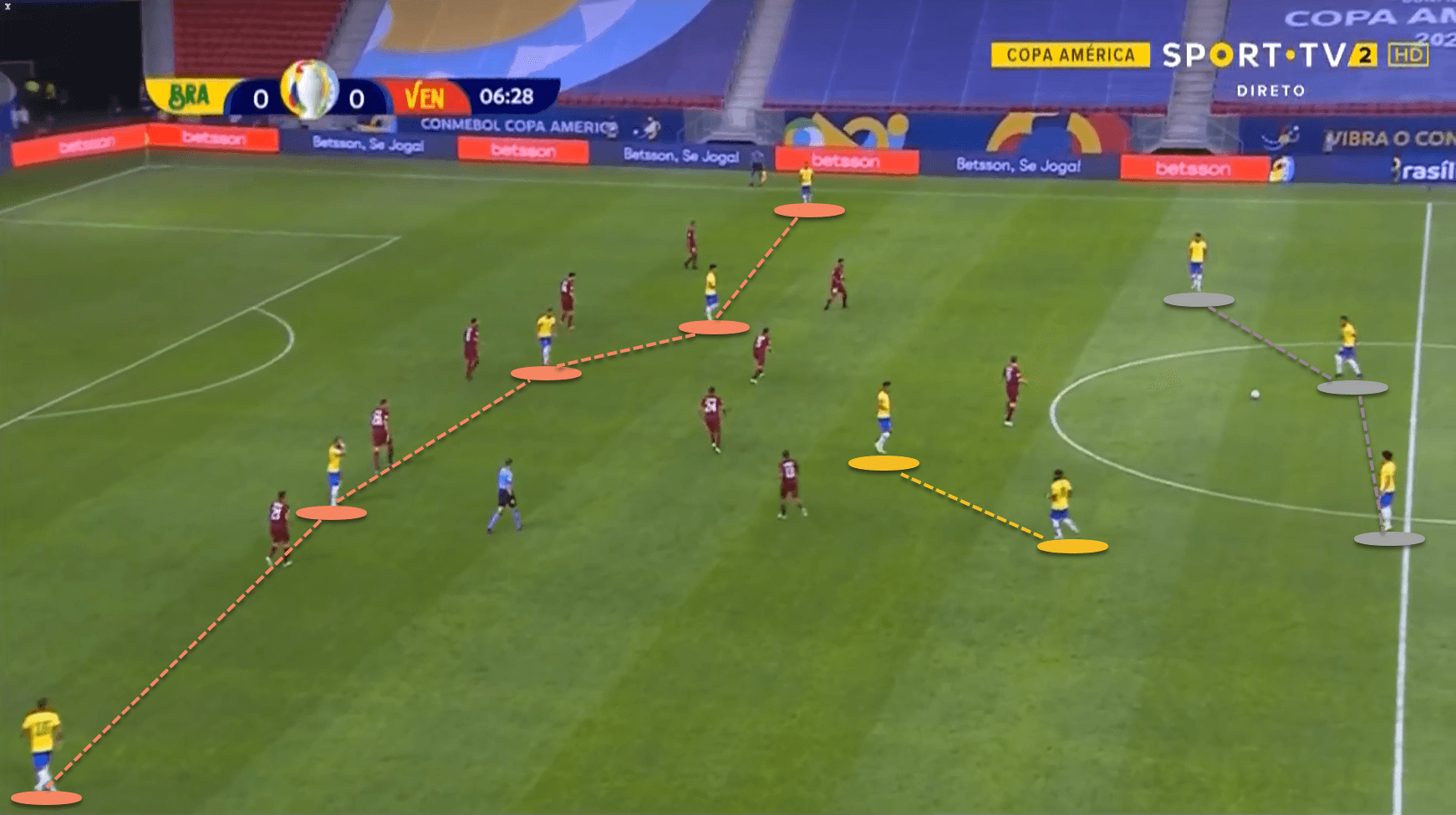

As we have already mentioned, Brazil’s shape for this match was a curious one. On paper it may have seemed to be a 4-3-3 or even a 4-2-3-1, but it was nothing of the sort on the pitch, with Tite having sent his side out to try and maximize width and offensive depth to try and get past Venezuela’s deep block.

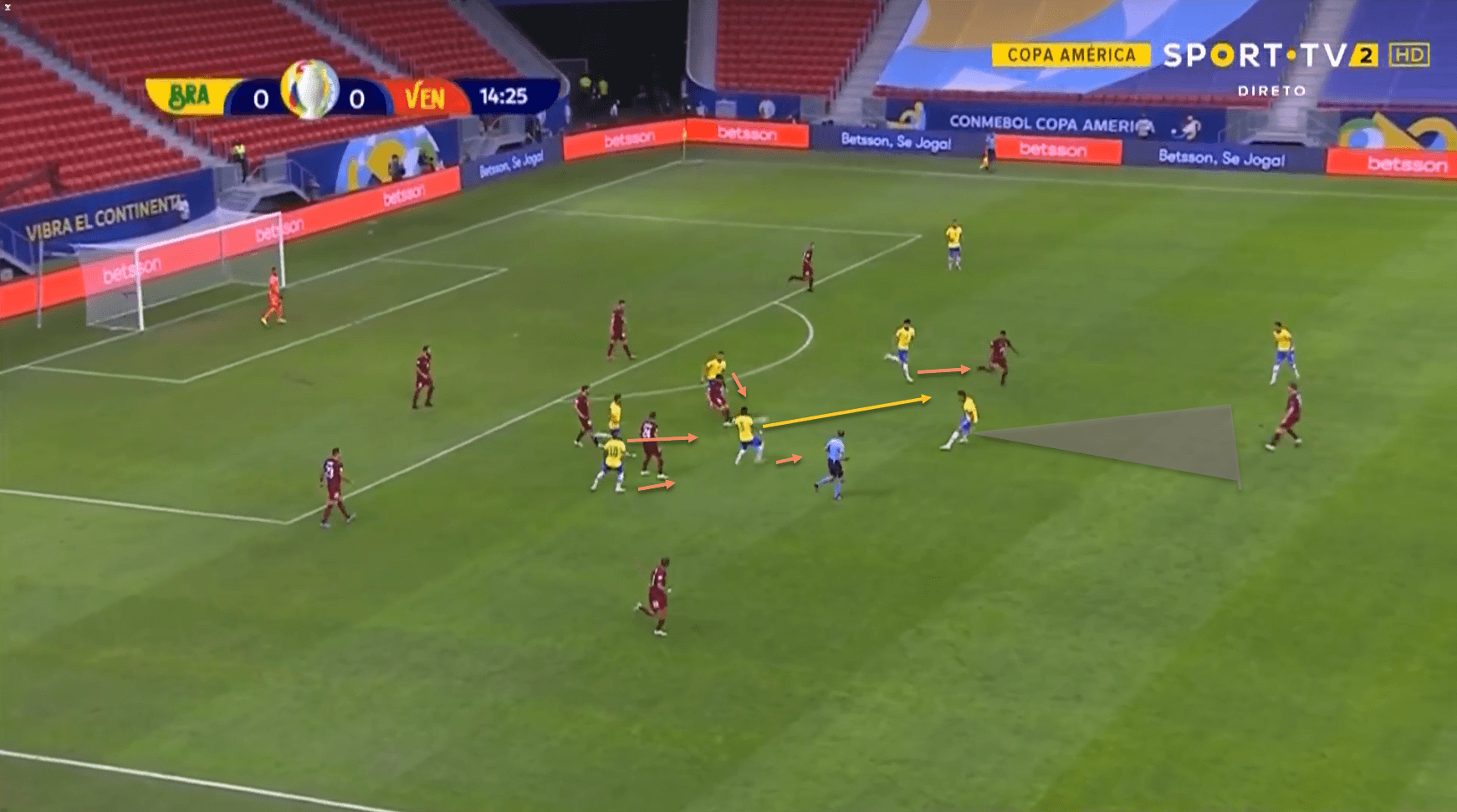

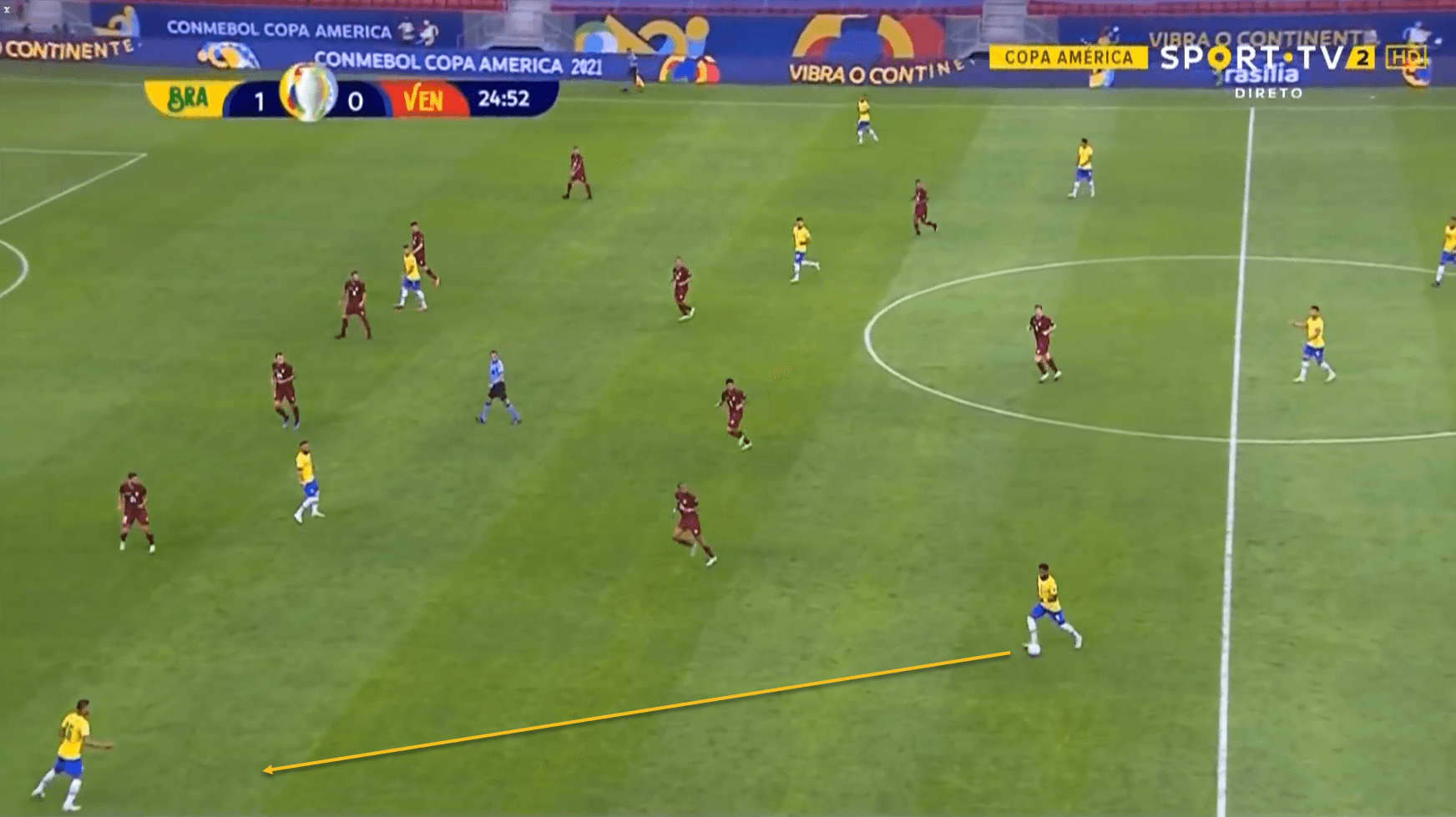

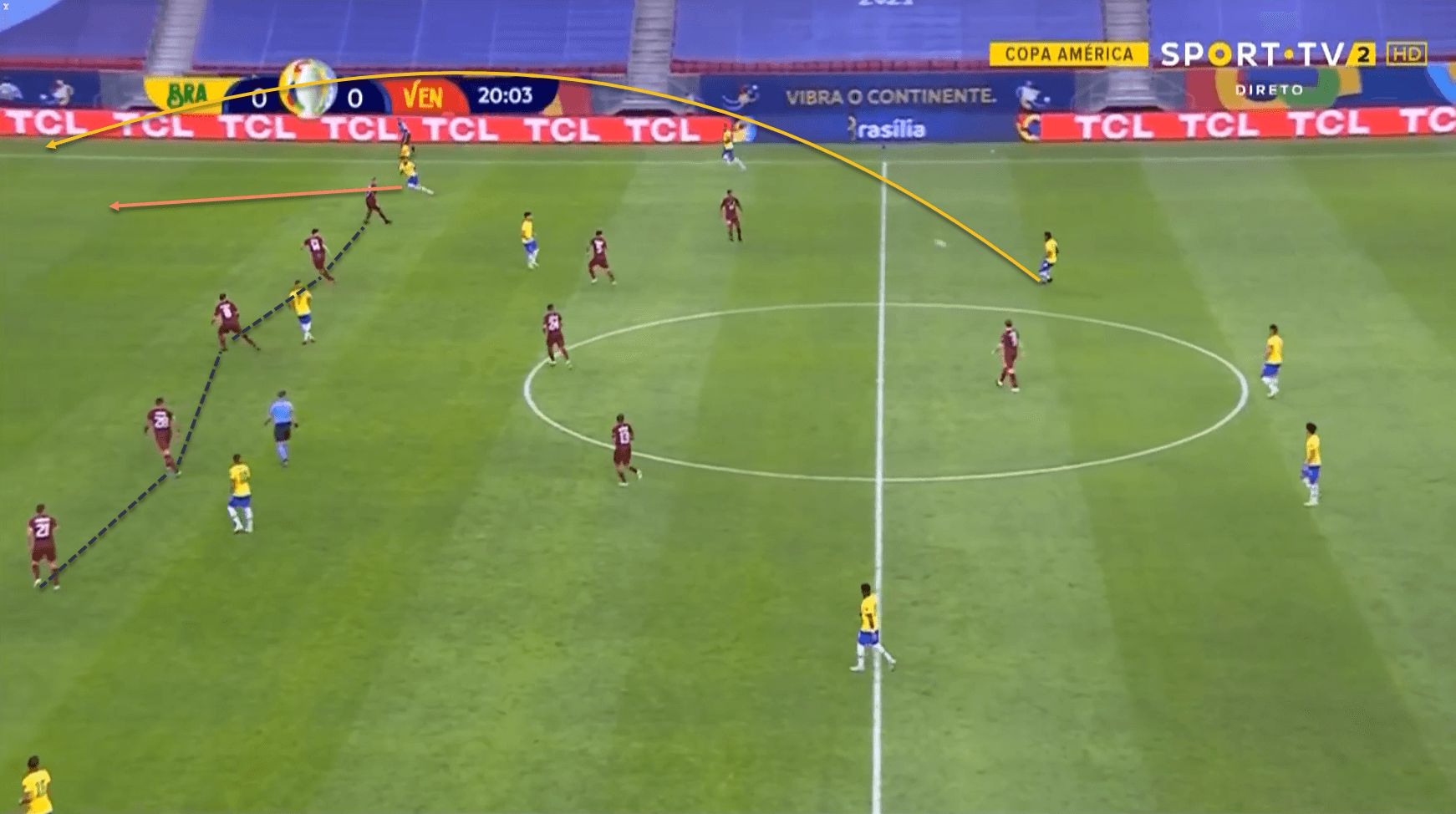

This image shows Brazil’s shape in possession – Danilo would usually tuck infield from right-back to form a central back three with Marquinhos and Éder Militão, the centre-backs, with Fred and Casemiro as a midfield pivot ahead of them. On the left, Renan Lodi would push extremely high to provide width, while it was Jesus fulfilling this role on the opposite flank. Neymar and Paquetá attempted to play in the half-spaces on either side of Richarlison, who largely stayed central and tried to make runs in behind the Venezuelan defence whenever possible.

Fred’s role was quite interesting – the Manchester United man would go wide when Brazil had the ball, almost operating as a defensive left-back, with Lodi staying higher up the pitch in front of him. It was notable how Fred rarely attempted to venture forward – there was one moment in the first half of this match where he went outside Lodi on the overlap, but immediately checked his run and moved infield rather than beyond the Atletico Madrid man. This was largely to protect Brazil during transition, while it also gave the Selecao an easy way to progress up the pitch by creating a numerical and positional overload in midfield.

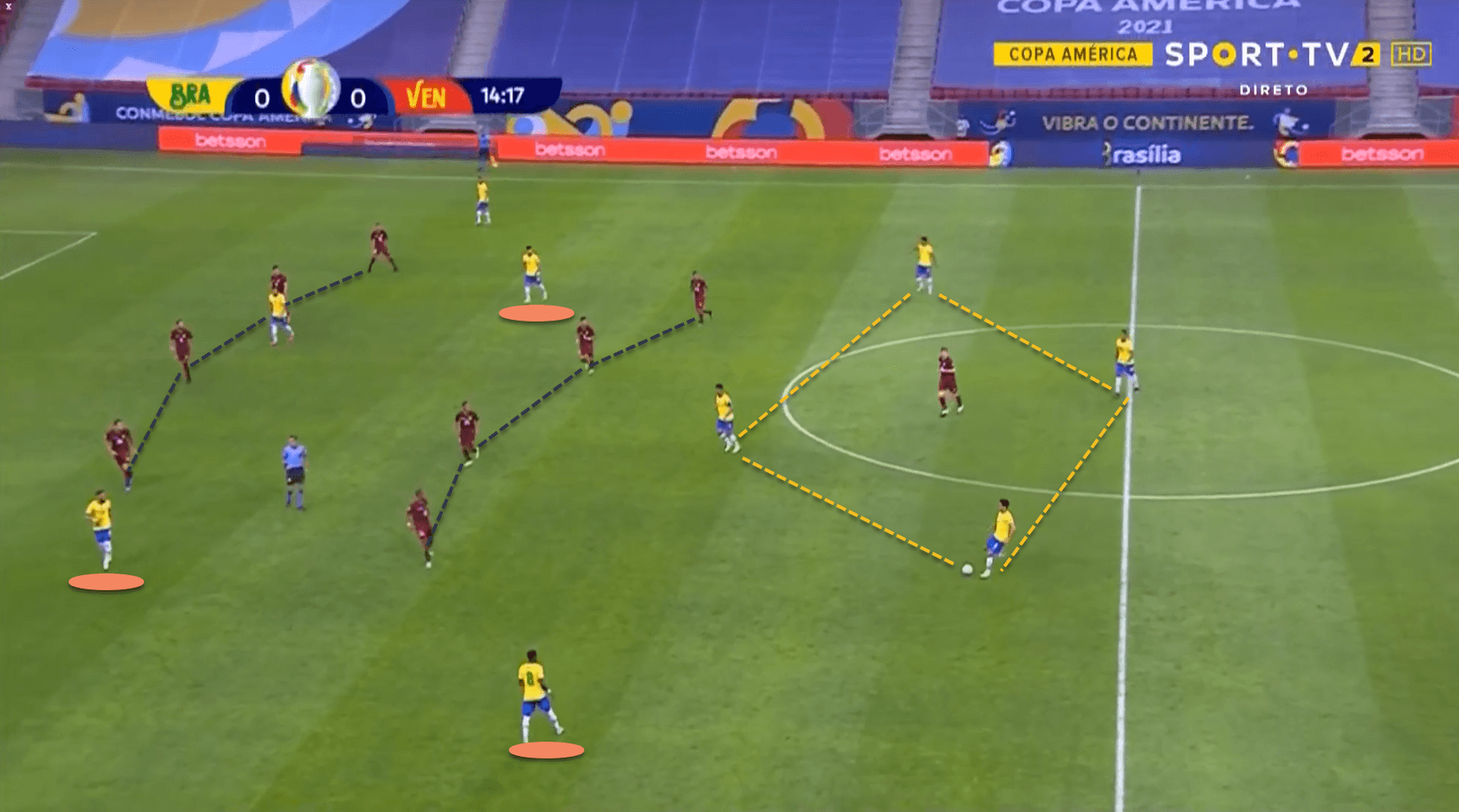

We can see the diamond that is formed here between Casemiro, Danilo, Militão and Marquinhos, with Fred moving wide to receive possession, outside of the Venezuelan block. Also note how Paquetá is in the right half-space, with Neymar in the half-space on the left, while Lodi (out of shot) is staying wide on the touchline on the left flank.

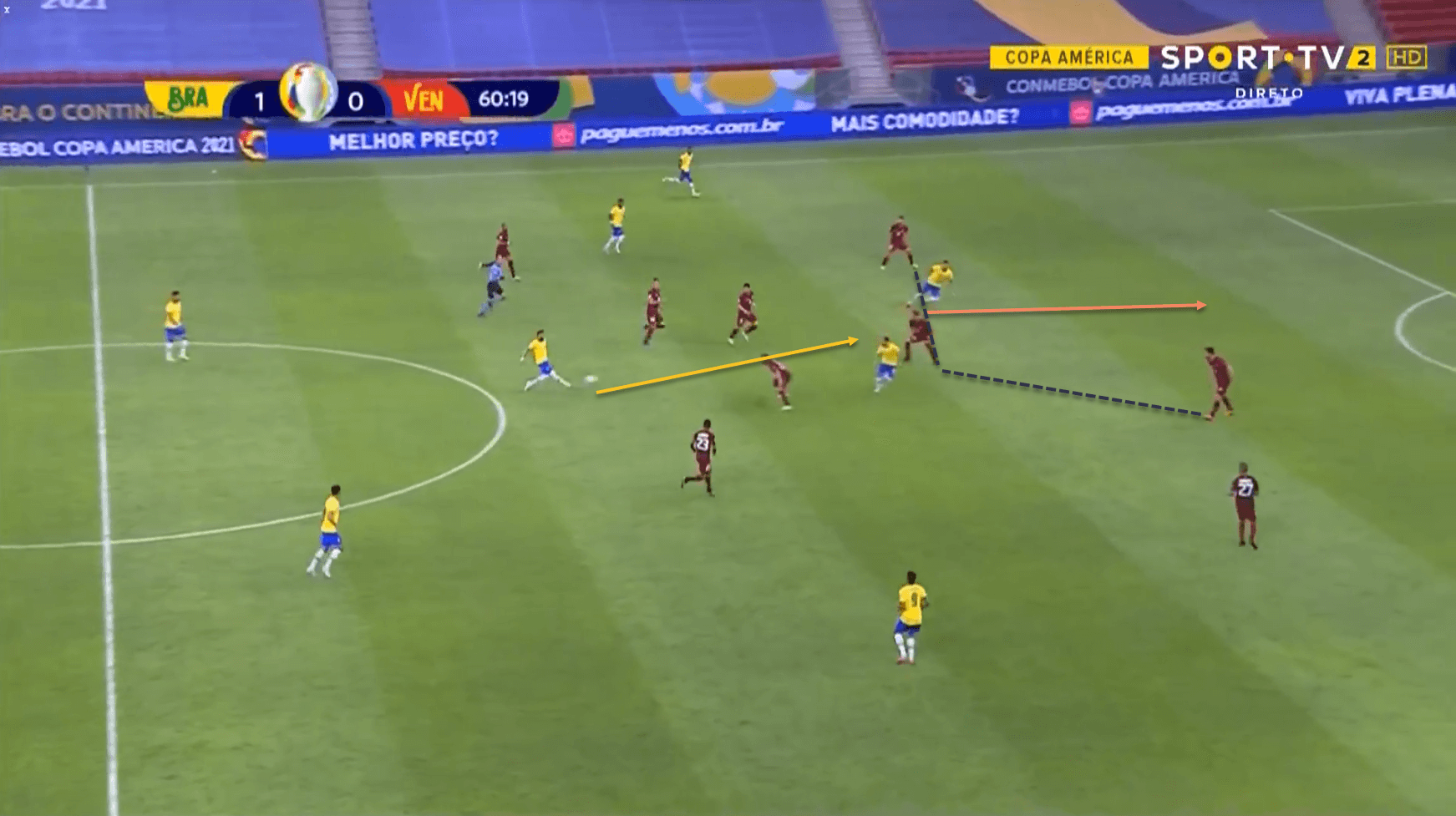

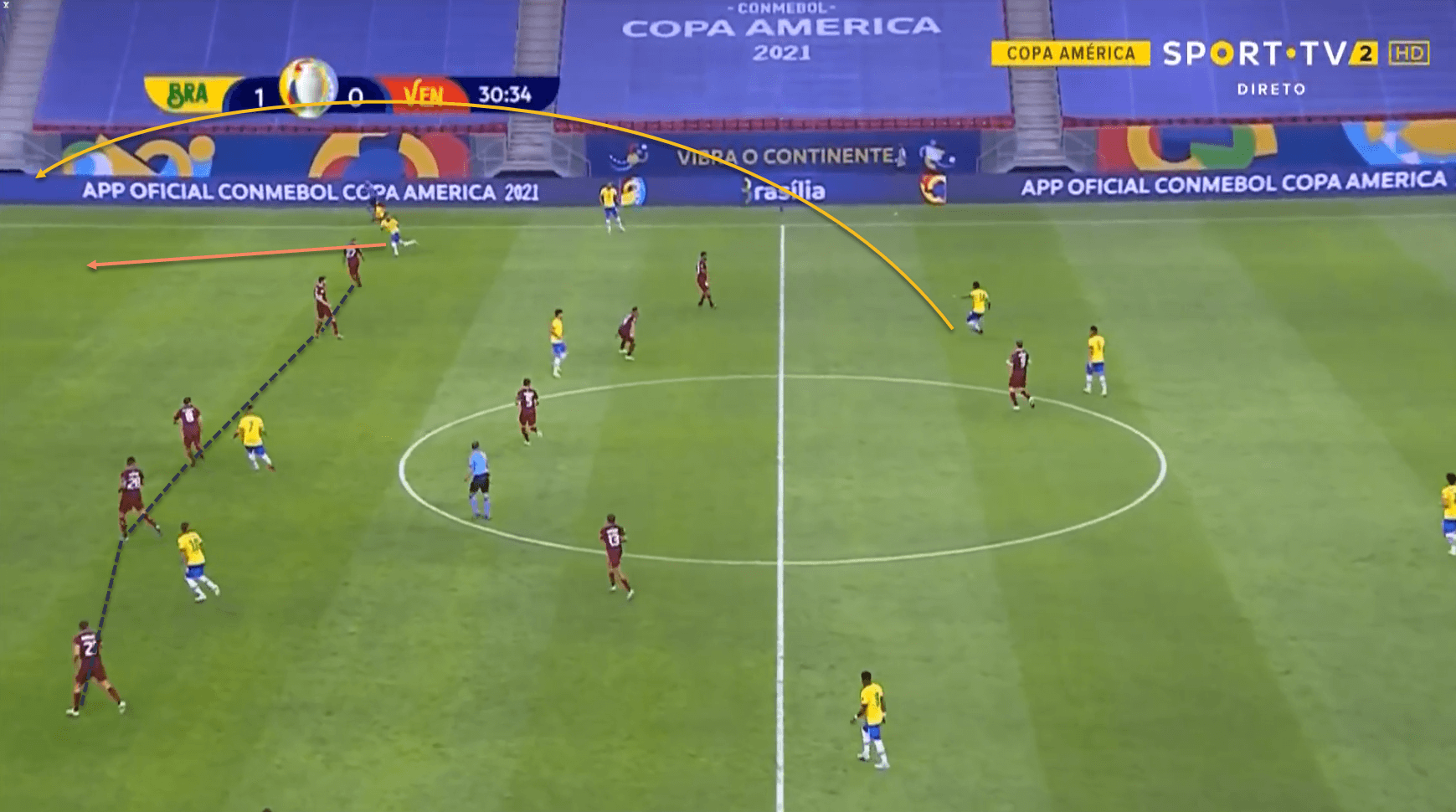

This image shows the sort of positions that Neymar and Paquetá constantly took up – between the Venezuelan lines and in the half-spaces, with Jesus and Richarlison making runs in behind and forcing the defensive line to drop, which, in turn created more space for the two Brazilian ‘playmakers’ to receive possession.

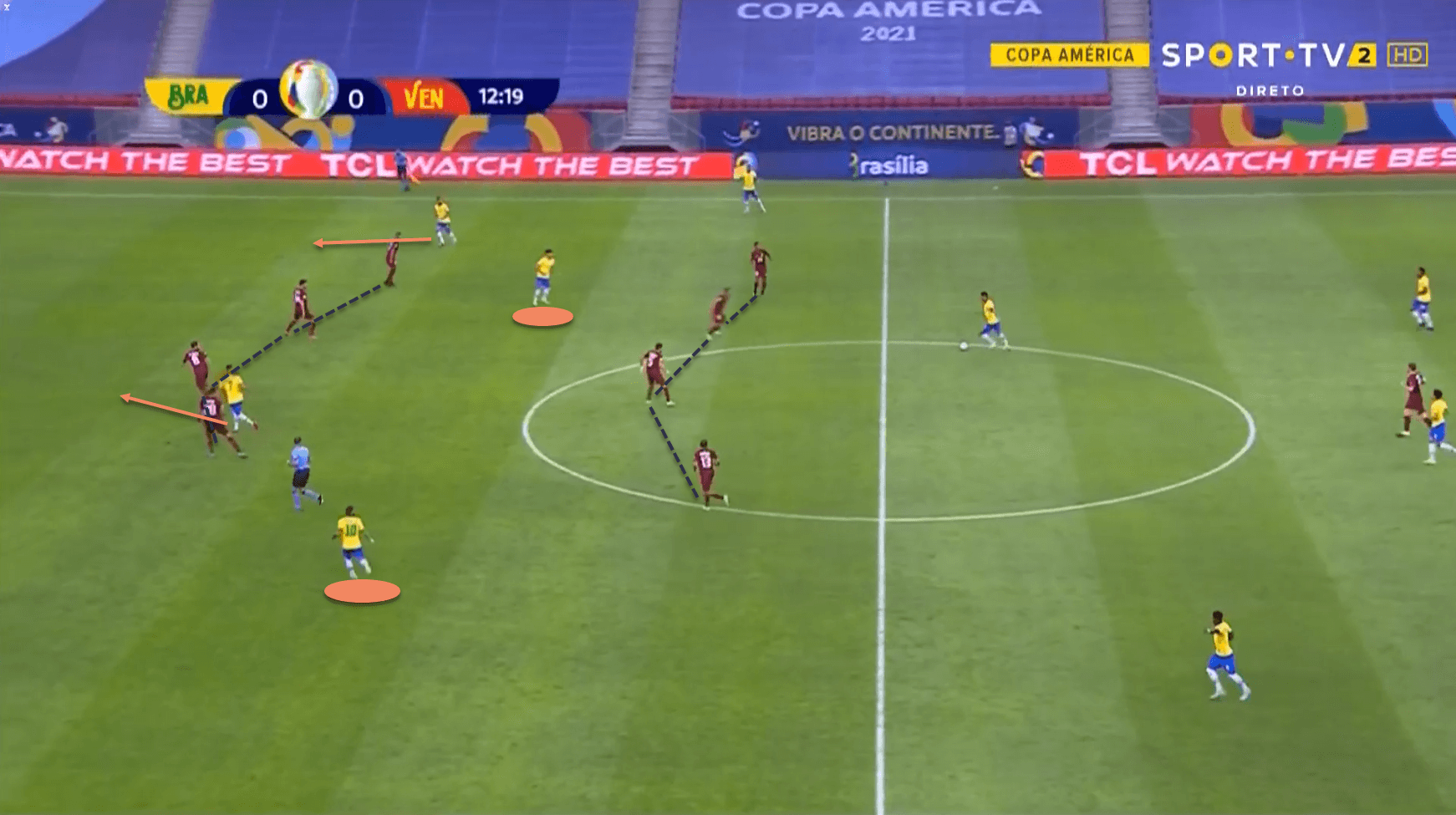

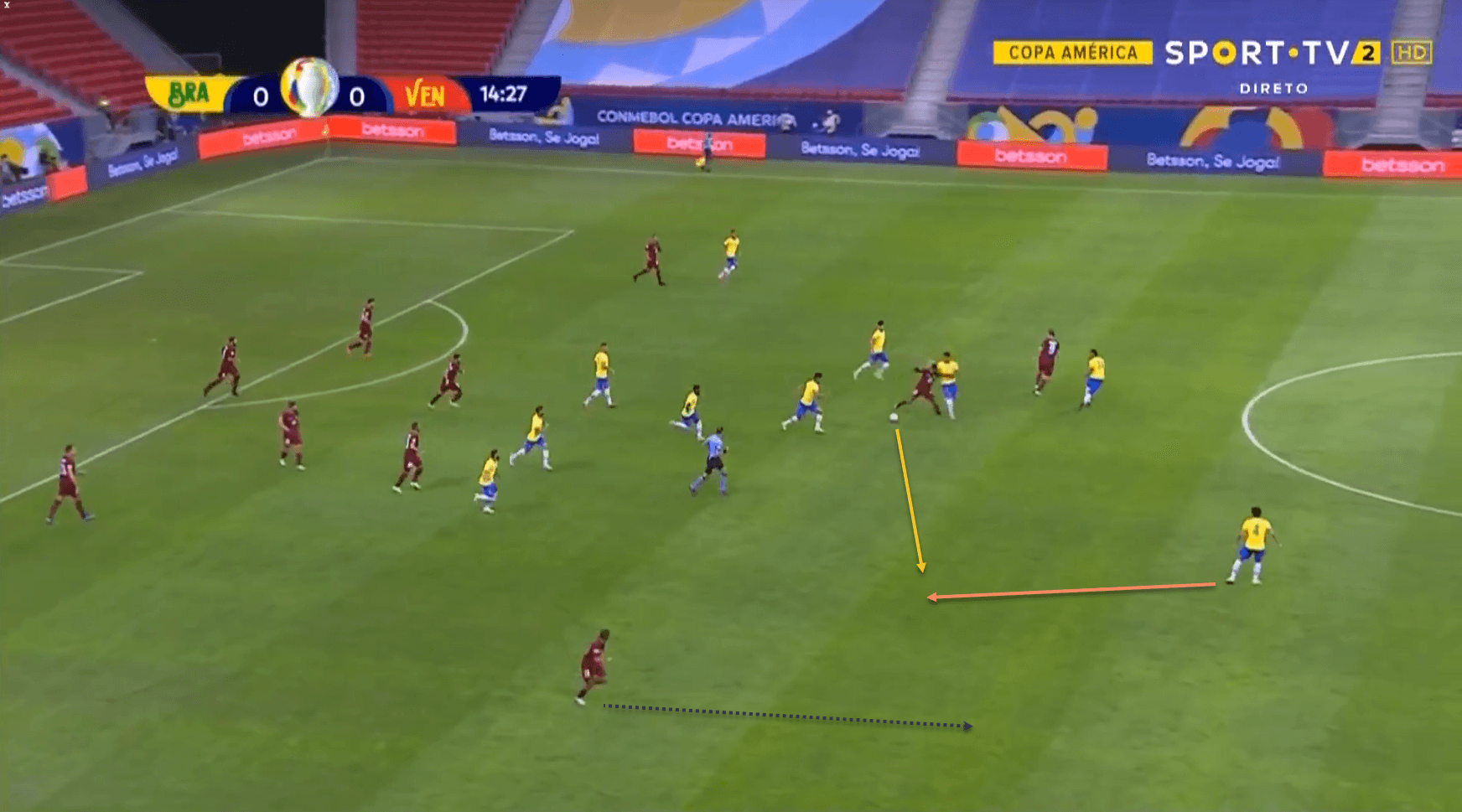

This approach also helped Brazil to counter-press quite effectively in this match, as they had a number of players close to each other who could immediately put pressure on the Venezuelan players.

The moment Brazil lose the ball here, they swarm over the Venezuelan players, with Casemiro cutting off the pass to the striker.

While Brazil fail to cut out the initial pass, they are applying enough pressure for the Venezuelan player to mishit his pass out wide, and Marquinhos is able to intercept and move forward to try and create an opportunity.

If this counter-press failed, Brazil immediately fell back into a compact 4-4-2 shape, with Neymar and Richarlison left upfield to provide a counter-attacking threat.

Left-sided bias

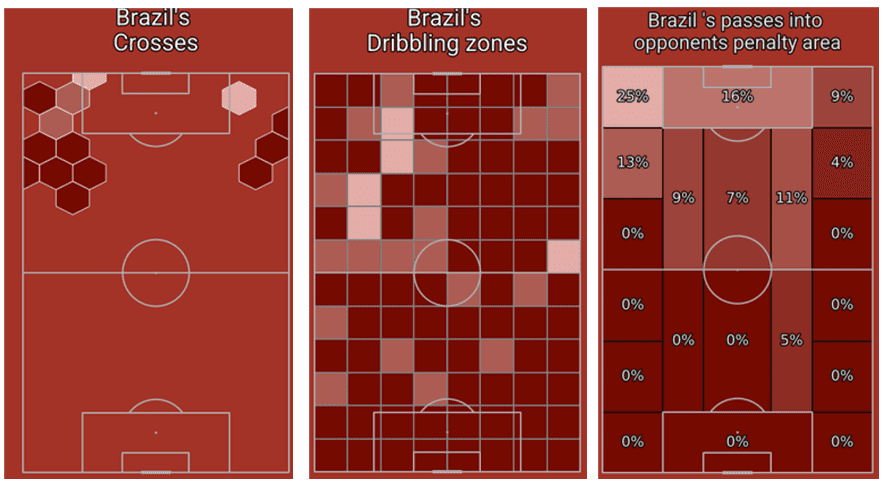

The majority of Brazil’s attacking play in this match came down the left flank, with Lodi, Neymar and Fred often combining before attempting to find Richarlison in the penalty area.

These action maps, taken from the excellent post-match analytics report produced by Sathish Prasad (which you can download for free here) shows Brazil’s tendency to attack down the left flank, with the majority of crosses, dribbles and passes into the penalty area coming from that side of the pitch.

Richarlison’s willingness to run behind the defensive line played a big part in this tactic, as it allowed Neymar to come deeper and get on the ball, while also providing a target for Lodi and occasionally Fred to try and find with crosses from deeper areas.

We can see one such situation below –

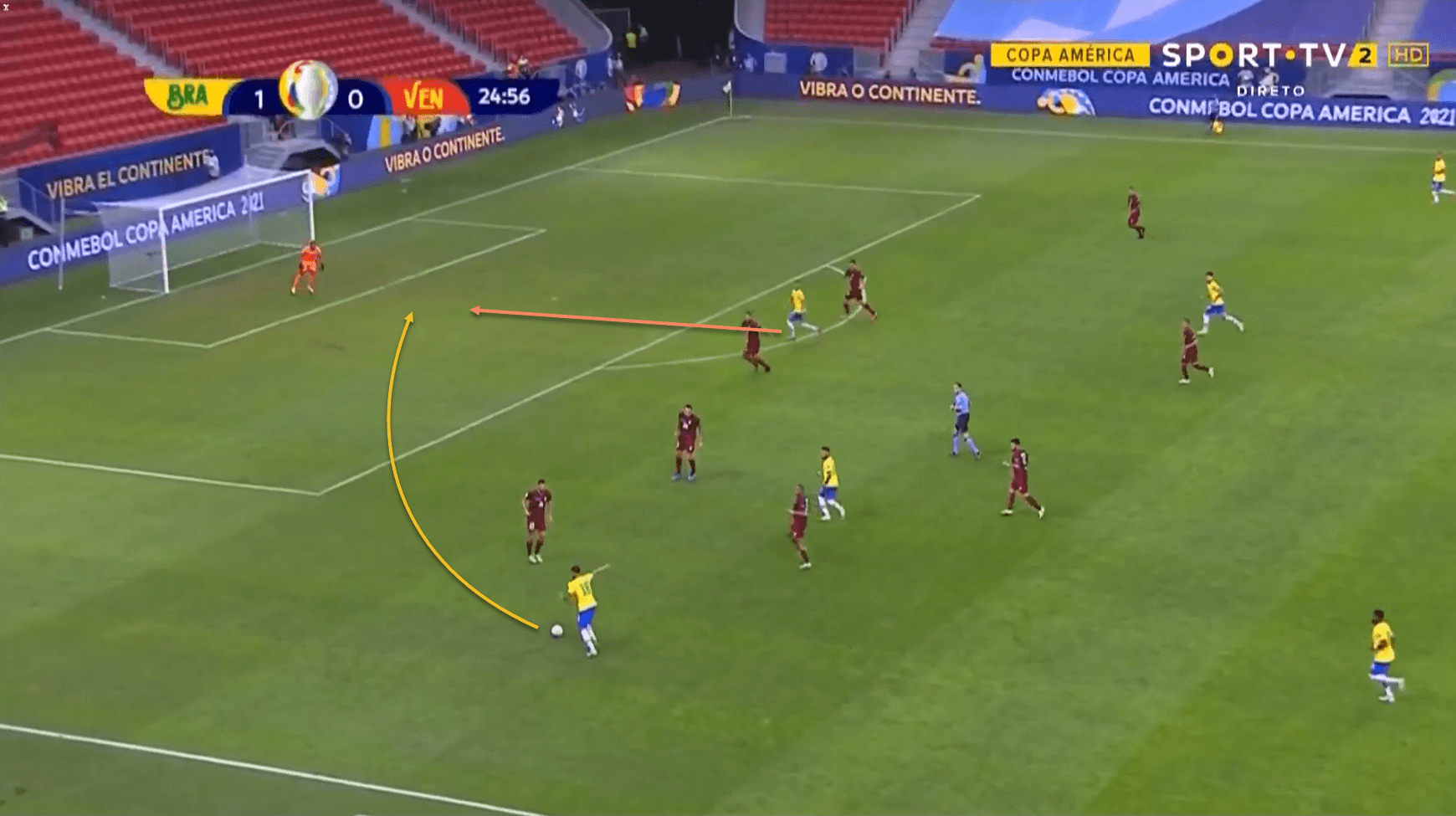

Neymar also attempted to find Richarlison on occasion from a similar position –

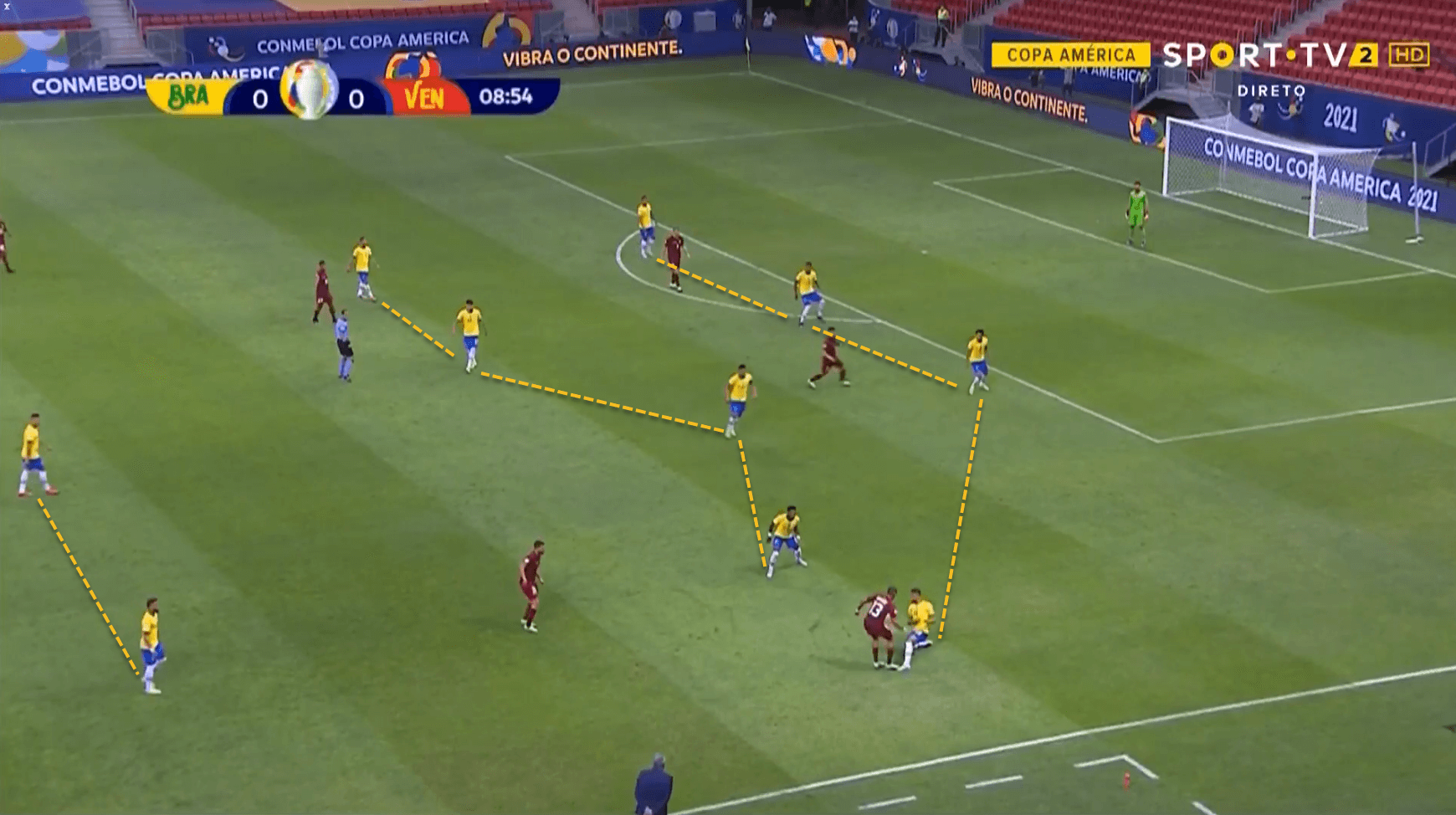

Neymar would also link up with Richarlison on occasion, with their movement working well together – the Paris Saint-Germain man would drop deep to receive the ball to feet, with Richarlison sprinting in behind.

Here, Neymar comes short to receive Casemiro’s pass, dragging one of the Venezuelan defenders out with him, and immediately Richarlison makes a run into the vacated space.

Neymar is able to receive, turn and then fire a pass through to the Everton man, who is able to run in behind, with the Venezuelan defence having conceded space due to Neymar’s movement into deeper areas.

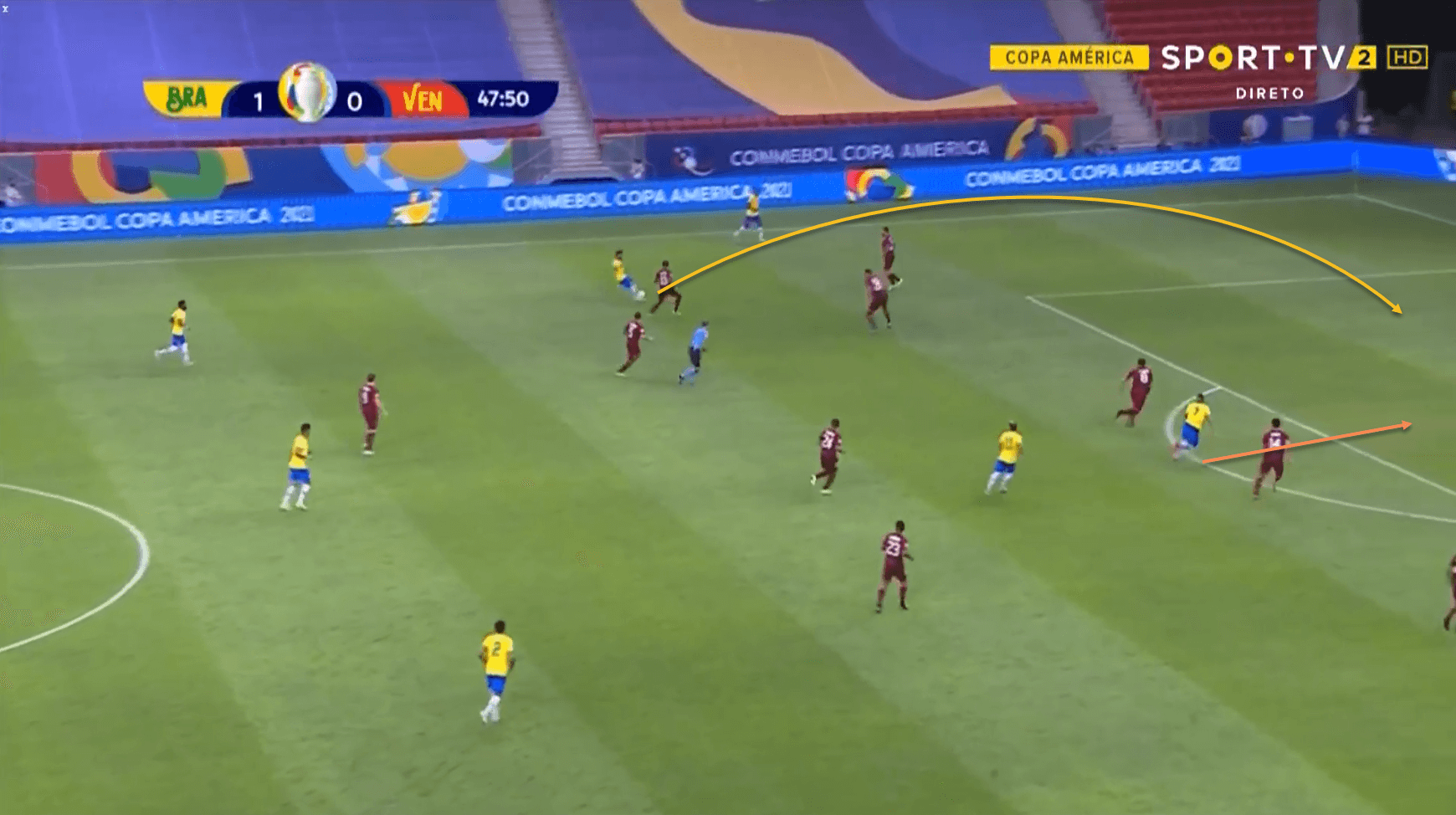

It was a different story on the opposite flank, where Jesus stayed high and wide, in contrast to Neymar – another frequently-attempted move was to try and find the Manchester City forward in space running onto a lofted pass from the defence, usually made by Militão.

This was essentially the story of Brazil’s attacking play in this match – they attempted most of their attacks down the left, with Neymar, Lodi and Fred combining to try and release Richarlison, while they went a little more direct down the right, utilising Jesus’ pace by asking him to stay high and wide.

Conclusion

Brazil’s task was undoubtedly made easier by the Venezuelan absentees, but this was still quite an impressive victory with quite a few interesting tactical facets. Given the format of this tournament, it is guaranteed that Brazil will make it to the quarter-finals, and thus the group stages could provide a decent platform for Tite to fine-tune his strategy before the business end of the tournament comes around.

Comments