It has been a mixed recent history for the Peru national football team. Surrounding the build-up to the 2018 World Cup was a narrative around a potential dark horse Peru side. Wins against Croatia, Uruguay, Ecuador, amongst others, built up hype for a team led by Ricardo Gareca since 2015, who had finally moulded a squad ready to face the biggest teams. The tournament itself was a disappointing blowout in the group stage, but it preceded Gareca’s greatest feat as Peru coach, reaching the final of the 2019 Copa America.

In 2021, it is a squad struggling for confidence and form – a squad spearheaded by a 37-year-old striker with no truly redeemable long-term replacement. La Selección are in dire need of rejuvenation. The Peruvian league is not exactly famed for its promotion of young talents coming out of the academy in recent years. Kluiverth Aguilar is one of the exceptions at just 18-years-old for Alianza Lima – perennial underperformers in their recent history. Arón Sánchez is another 18-year-old defender breaking through at senior level for Cantolao; a Peruvian club mostly known for its prestigious youth academy.

These, however, are exceptions to the rule for recent Peru squads. Gareca has primarily composed his recent squads with players at least 21-years-old. It seems he values experience and squad chemistry over giving unknown youth talents a chance to embed in the squad at an early age. This has aligned with a bad moment for Peruvian football, struggling desperately against some of South American best teams. A 4-2-3-1 or 4-1-4-1 has been used in their latest fixtures, which has resulted in one draw and three losses

As a squad, they lack star quality across the XI. Just four members of their recent squads ply their trade in Europe’s top five leagues and while they do have players who have played in these leagues previously, they are now well into their thirties. Jefferson Farfán as just one example is now 36-years-old, not able to perform at the stunning heights he used to. History shows us that old squads do not typically succeed at international tournaments, which could especially be the case with this season’s unyielding fixture schedule.

In a group against Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, Peru’s success relies heavily on the fixtures against the latter. Games against Brazil and Colombia are expected to go one way and one way only, but if they can upset the applecart, more power to Peru. The games against the other two sides are must-wins, nonetheless. They have shown they are a side who can compete in these bigger spectacles, but unfortunately, results at this stage are often predicated by which side has the star talents in an attacking sense. In this tactical analysis, we are going to an in-depth analysis and see what they can do to strike the right balance between nullifying the opposition’s attacking threat and producing high-quality attacks of their own.

THE SQUAD

Goalkeepers:

Carlos Cáceda

José Carvallo

Pedro Gallese

Defenders:

Luis Abram

Luis Advíncula

Miguel Araujo

Alexander Callens

Aldo Corzo

Marcos López

Chrisitan Ramos

Anderson Santamaría

Miguel Trauco

Midfielders:

Pedro Aquino

Christian Cueva

Sergio Peña

Edison Flores

Christofer Gonzáles

Yoshimar Yotún

Forwards:

Luis Iberico

André Carrillo

Paolo Guerrero

Gianluca Lapadula

Raúl Ruidíaz

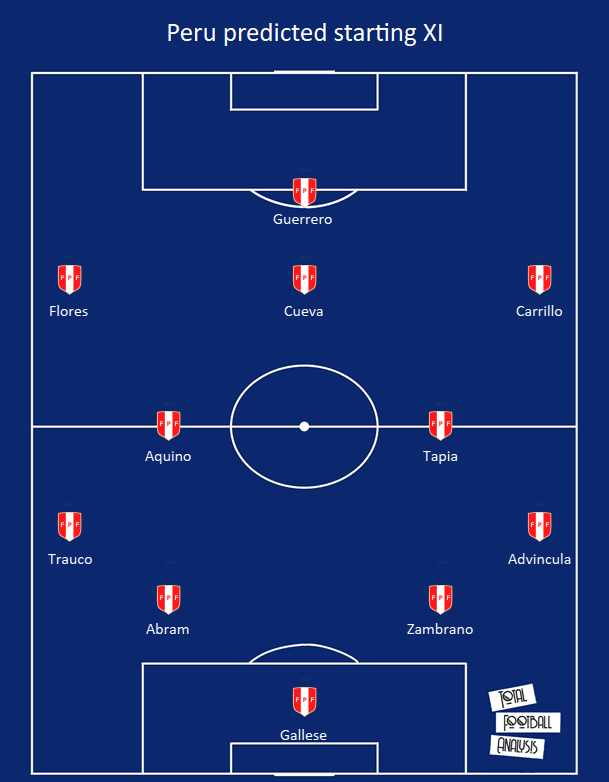

Recently, to limited success, Peru have been lining up in either a 4-2-3-1 or a 4-1-4-1. Although they have been struggling of late, the 4-2-3-1 does enable some of Peru’s better players to feature in their favourite positions. A couple of matches against Colombia and Ecuador act as their only bits of real-time preparation just a week before the actual tournament. In theory, they should get a feel for how their opponents will play before the tournament, but such is true with their opposition as well. It may all come down to which team is fitter than another, rather than a true test of who is better.

Beginning at the back, goalkeeper Pedro Gallese of Orlando City will retain his place as #1 – at the moment the 31-year-old is boasting an extraordinary 92.9% save success rate in the 2021 MLS season so far (a season only five games deep). It is predicted that Gareca will stick with the centre-back partnership of Carlos Zambrano and Luis Abram, both of whom play week in week out in the Argentinian Primera Division. The full-backs represent a duo of real quality, two players that operate in Spain and France, Luis Advíncula at right-back is one of the squad’s most experienced pros with 93 caps to his name, while Miguel Trauco is a regular starter for Saint-Étienne, mixing good defensive output with decent chance creation in a top-five European league.

In midfield, Peru boast their greatest current player in Renato Tapia, who is a key player for La Liga outfit Celta Vigo. He is a solid 1v1 defender, a great reader of the game, and has decent passing range, but it is the defensive aspects of his game he excels at. His injury sustained in early May presents a selection issue for Gareca if he were unable to make it in time for the tournament. Lining up beside him could be one of two players, both of whom play regularly in the Liga MX, Pedro Aquino or Yoshimar Yotún. Yotún is the more experienced of the two, but Aquino is expected to solidify his starting position in this tournament.

In the attacking unit, Peru boast far less quality of depth. Jefferson Farfán picked up an injury when playing for boyhood club Alianza Lima, and at 36-years-old, it could mean the abrupt end of his playing days. André Carillo has been Peru’s diamond in the rough in recent fixtures, scoring three goals in four games for the World Cup Qualifiers where Peru lost three and drew one. On the right-wing, Peru’s success in this tournament will rely heavily on his attacking impetus. Dubai native Christian Cueva will feature behind the striker in a 4-2-3-1 with Edison Flores, the DC United winger, providing support from the left-wing. The country’s beacon of shining light, Paolo Guerrero formerly of Bayern Munich, got back into action for Brazilian outfit Internacional in the last month after recovering from a serious injury, and being called up for the 50-man preliminary squad by Gareca demonstrates his sustained faith in the 37-year-old leader. Raúl Ruidíaz has also been prolific at club level for Seattle Sounders, but a pitiful 4 goals in 46 Peru appearances has limited the trust that Gareca has laid upon him.

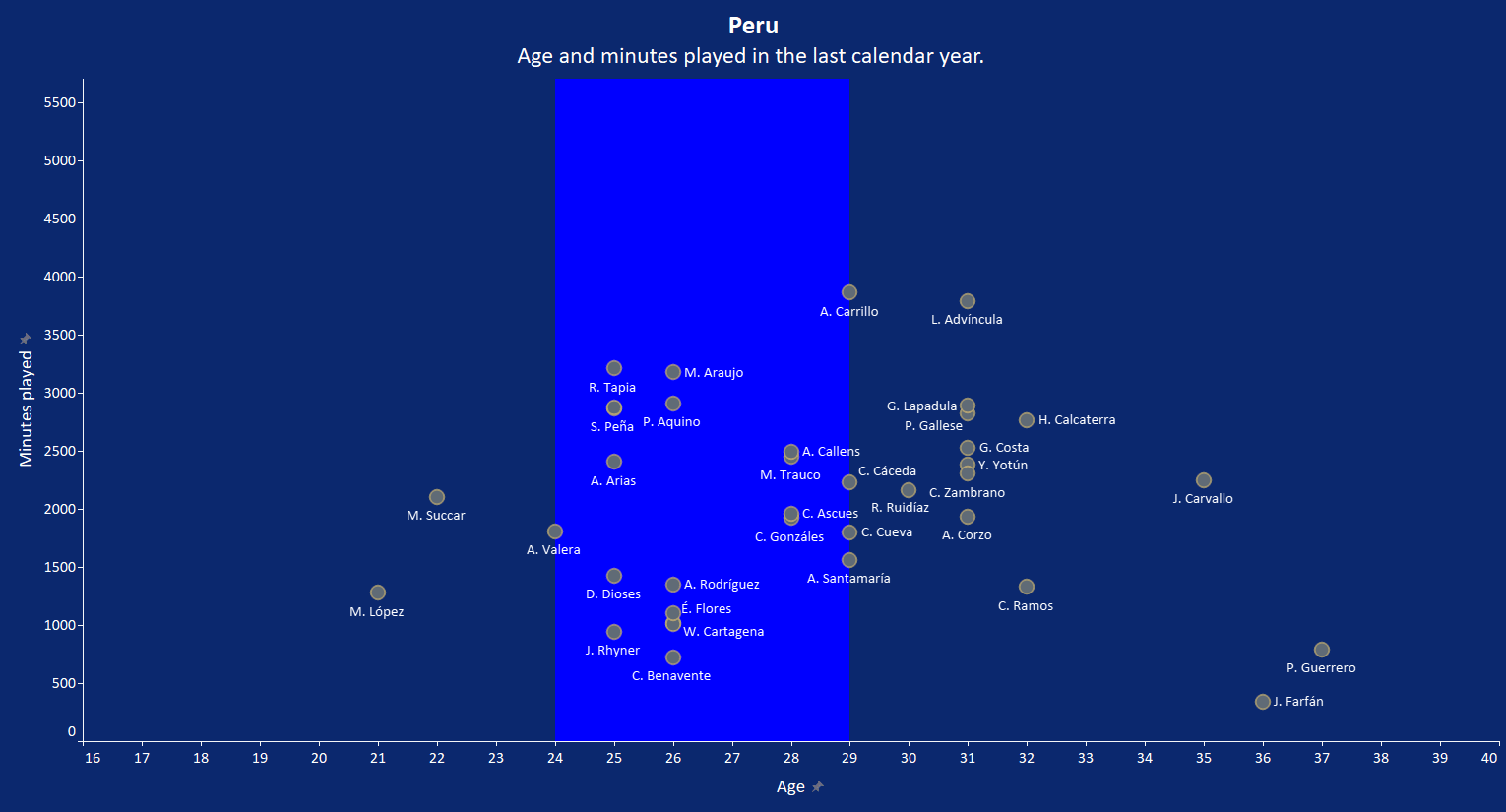

The above scatter graph of age and minutes played in the last calendar year backs up the statements made previously. Peru lack quality youth talent who could cause a stir at a national tournament as they have had in the past. Marcos López is the youngest at 21-years-old, currently breaking through at San Jose Earthquakes in the MLS, but as a defender, he cannot be expected to make a groundbreaking impact. Many of the players in the graph are labelled as playing in their ‘peak’ between the ages of 24 and 29. Although, many players in this zone of the graph will really just be squad members other than a few notable names such as Tapia or Carrillo. Players in their thirties here are still accumulating a decent number of minutes at club level, suggesting that people such as Gallese and Zambrano have a few years left in the tank yet.

ATTACKING PHASE

Let’s begin with the obvious: across the last calendar year, Peru have not played as much football than the typical year. The pandemic struck, games were postponed, and this team nearly went a year without playing football together. Let’s continue with a less obvious remark: during the period in which Peru have started to play matches again, they’ve been crippled with injuries. Key players have always been missing in some shape or form. At this moment, it appears that some of these key players will miss the tournament due to sustained long-term injuries.

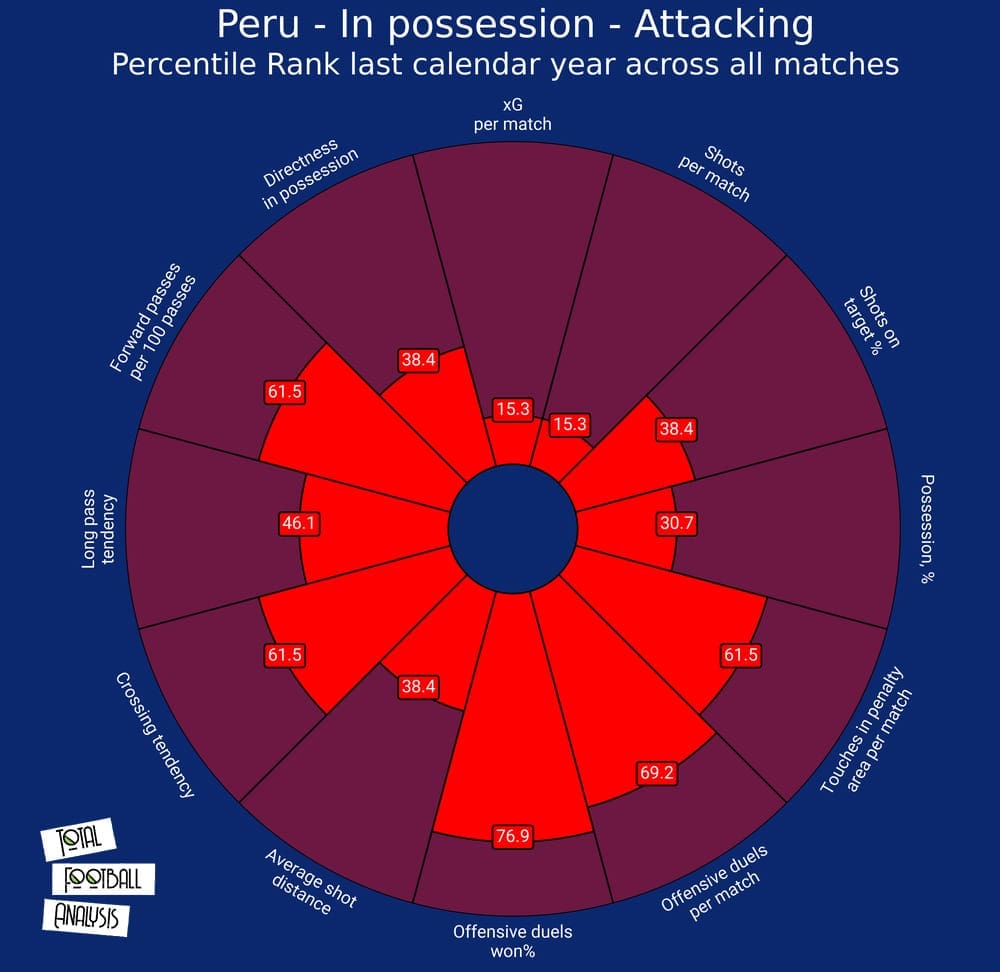

The attacking radar does not shine a bright light on Peru’s forward endeavours either. They rank in the 15th percentile for both xG and shots per match, yet they do have a decent number of touches in the opposition’s penalty area per match. This would indicate that when they get into shooting opportunities, they are indeed too slow to capitalise on them. Their shot distance is low, which bodes well for the opportunities they do get, at least they are of good value. We also understand that this team has a high tendency to cross the ball, and they do have some players with a decent whipping delivery in their toolbelt.

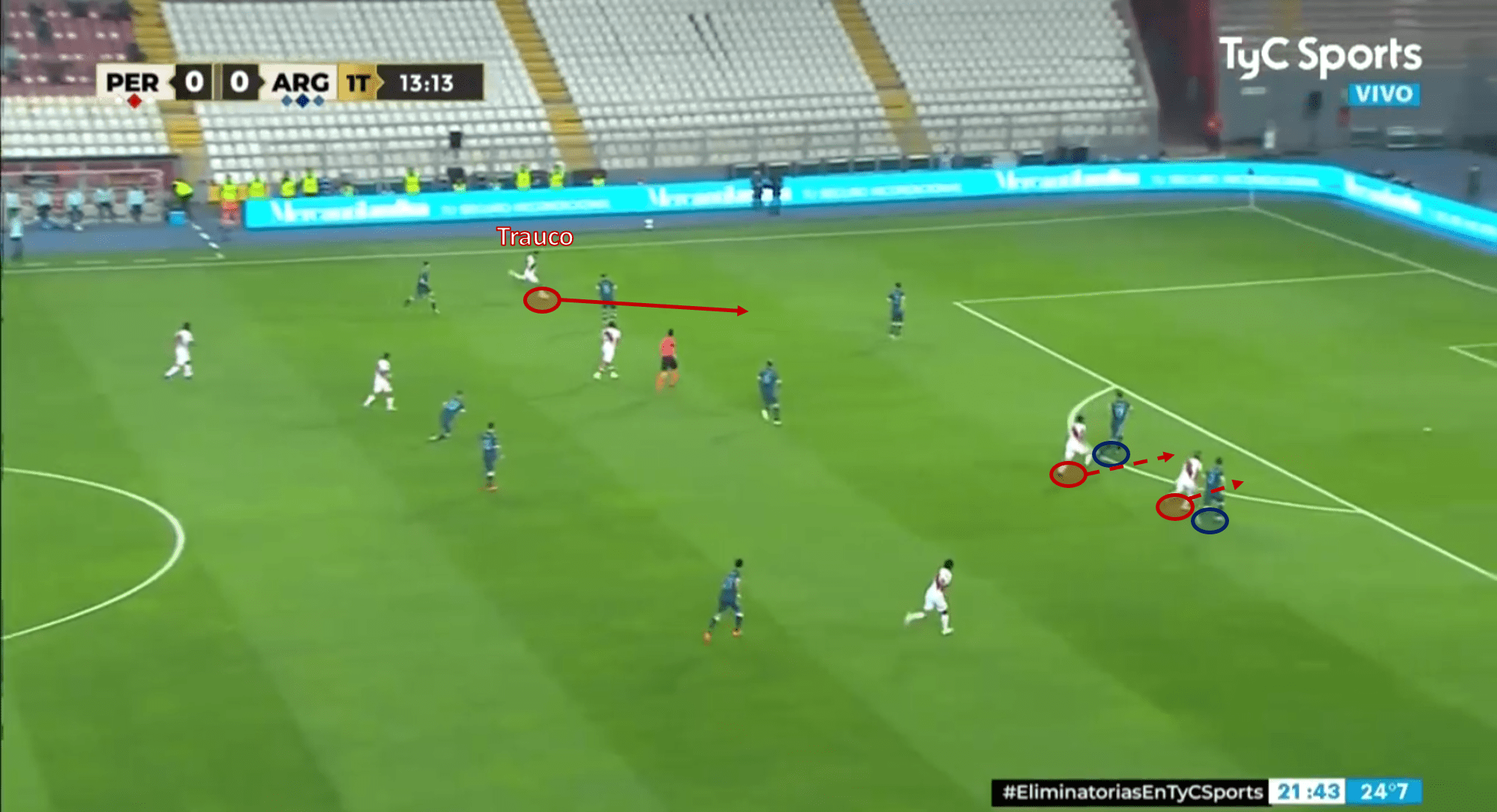

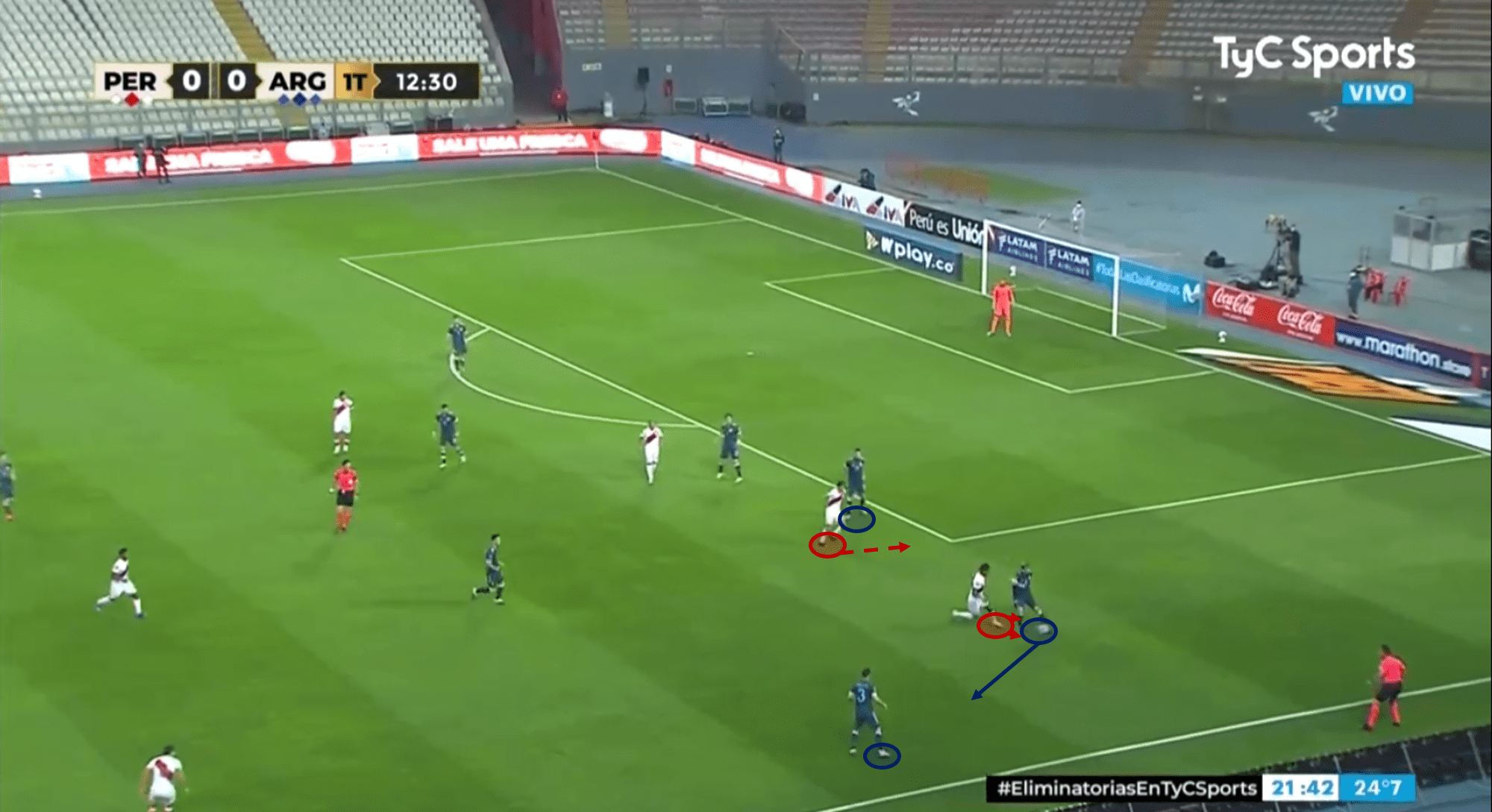

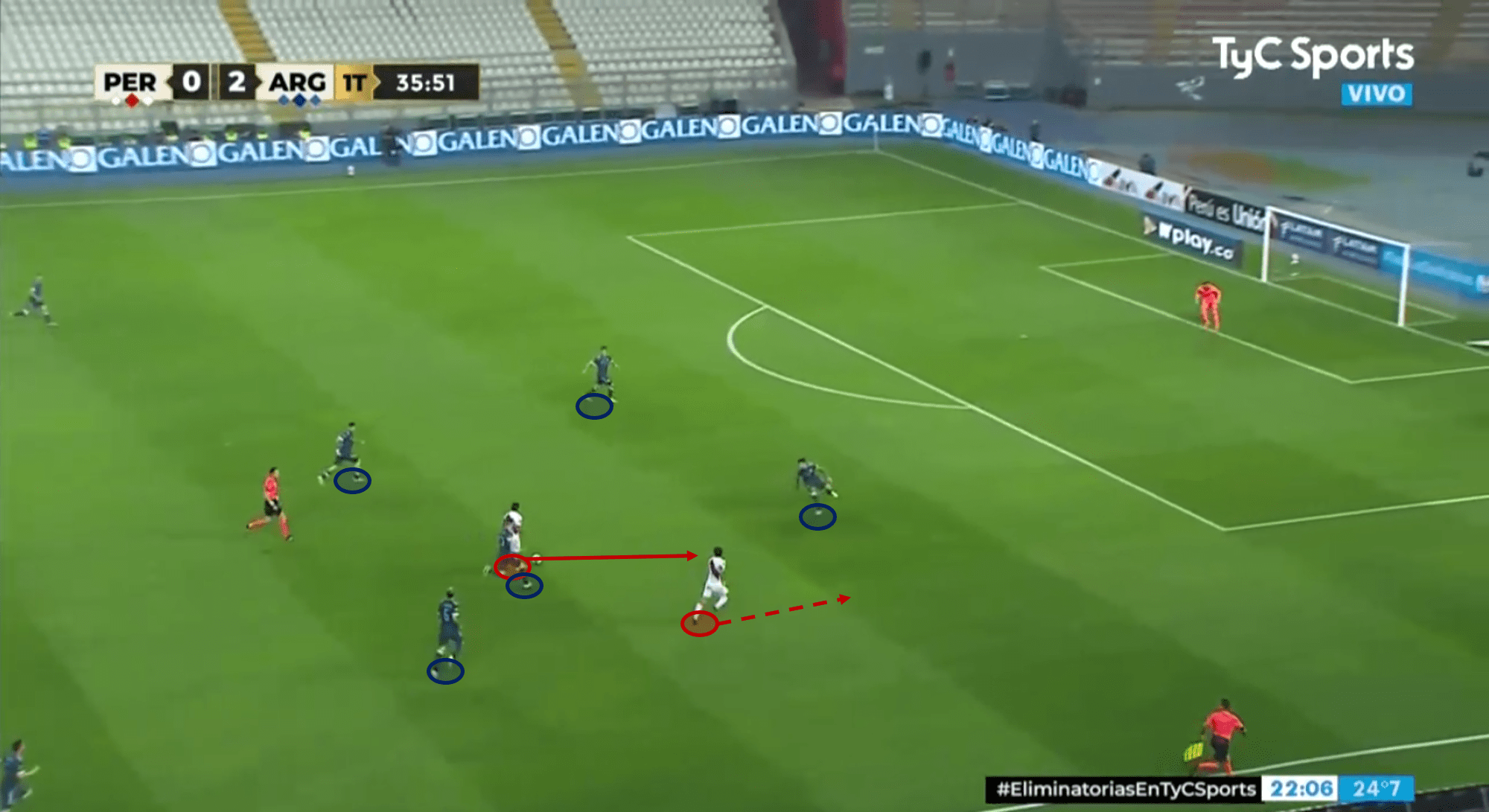

Against Argentina, we saw full-back Trauco venture higher up the pitch to cross from deep into the penalty area.

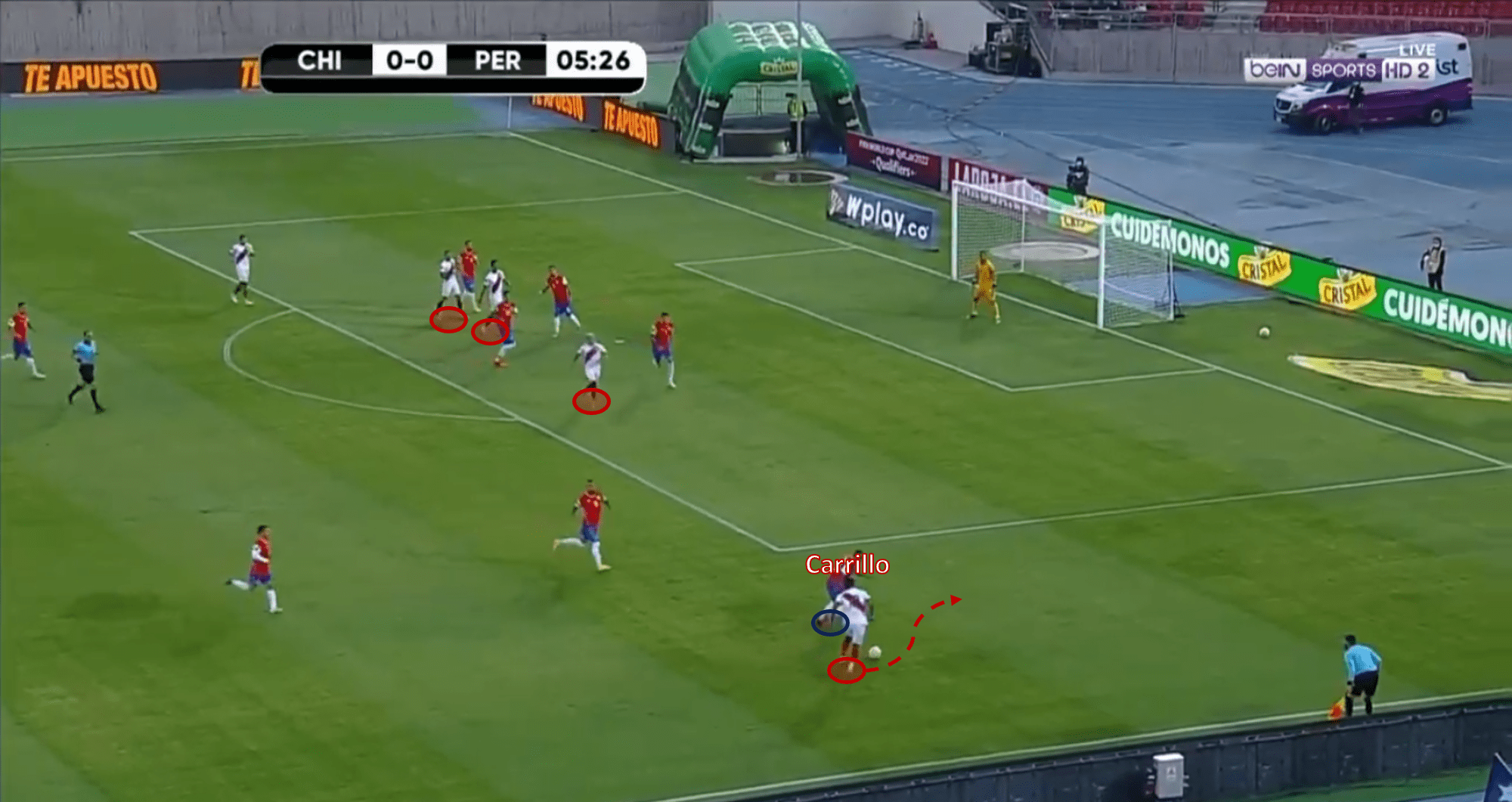

Most of the time, the idea in the final third is to get the ball into the feet of Carrillo, who has a good 1v1 dribbling ability to take it past players and get into areas of real threat. This will often occur down the flanks, Advíncula moves cautiously up the field to work closely with the right-sided central-midfielder, often Aquino, who will form a passing triangle with Carrillo and they interchange to get the ball past the midfield line of pressure. Once this happens, then Carrillo has a job to do. On his own for the most part, he will carry the ball into the final third where he can cut inside or sprint towards the byline and look to find the target-man inside the penalty area.

Carrillo here is up 1v1 against the defender, jinking his body left to right leaving the defender backpedalling, whilst having three targets to aim for inside the box.

Utilising a 4-2-3-1 or a 4-1-4-1, the idea is to protect the defence first before attacking, and as such enjoy hitting sides with high lines on the break. They have some players with a good amount of pace too, Carrillo, Cueva, etc. In these situations, they will throw men forward if they feel there is a high-value opportunity on goal to be had. Typically it will be just the forwards and maybe one midfielder, to protect the backline as much as possible too.

DEFENSIVE PHASE

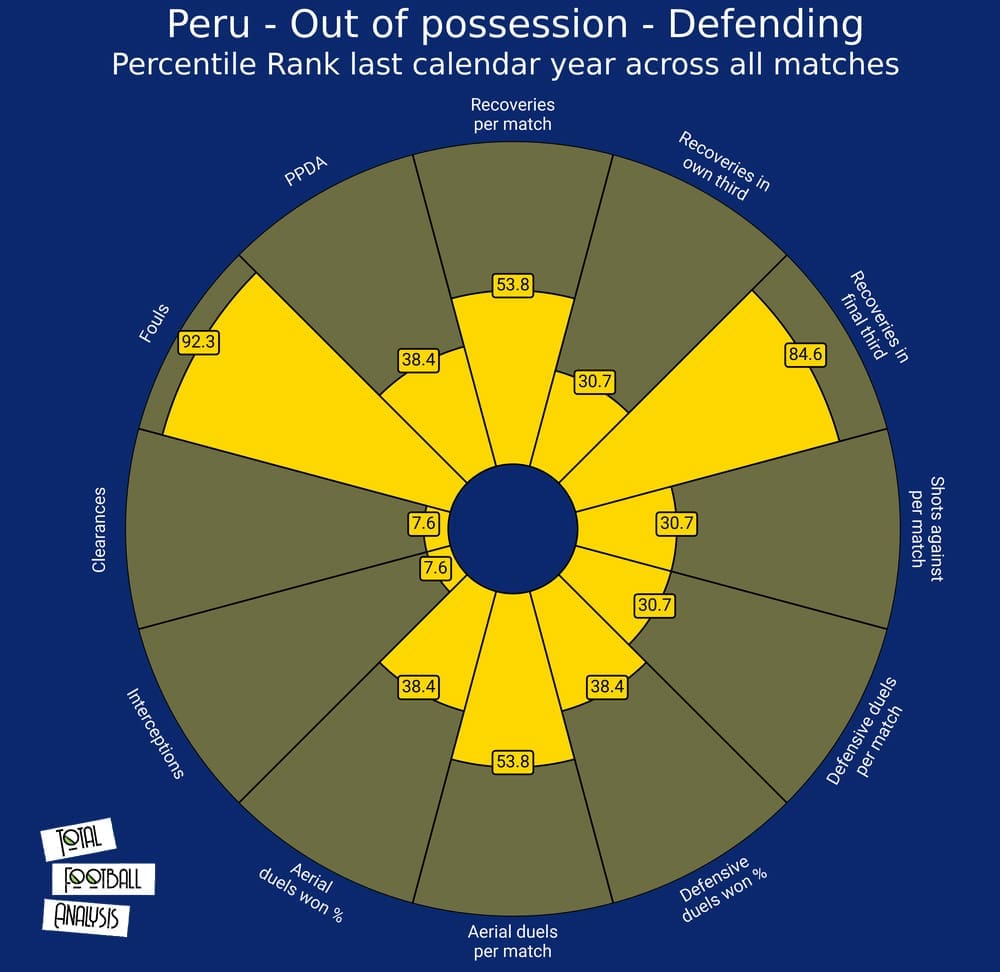

From a defensive perspective, it is clear to see that some of Gareca’s tactics are paying off to an extent. His low PPDA and high recoveries in the final third demonstrates the high-pressing style of play that he wants to employ, and this has resulted in a low number of shots conceded per match too. It is in fact defensive errors that let this Peru side down, and against Brazil, this culminated in a 4-2 defeat starring a hattrick from Neymar. They do press a fair bit, but in the process it can be quite sloppy, leading to a high number of fouls as we can see on the radar. In the actual tournament, they cannot afford to concede fouls at the rate they are currently at.

It starts from the front with the striker who looks out for pressing triggers and pressing traps. If a defender plays the ball out wide to a full-back, the striker will look to cut off the passing lane while the winger presses the ball carrier, and the attacking midfielder will press the spare man. In addition, if a defender passes back to the goalkeeper, this causes at least one attacker to press the goalkeeper, sometimes two if the attacking midfielder is close enough. At times, this causes Gareca’s attacking unit to temporarily switch to a two-up-top pressing unit.

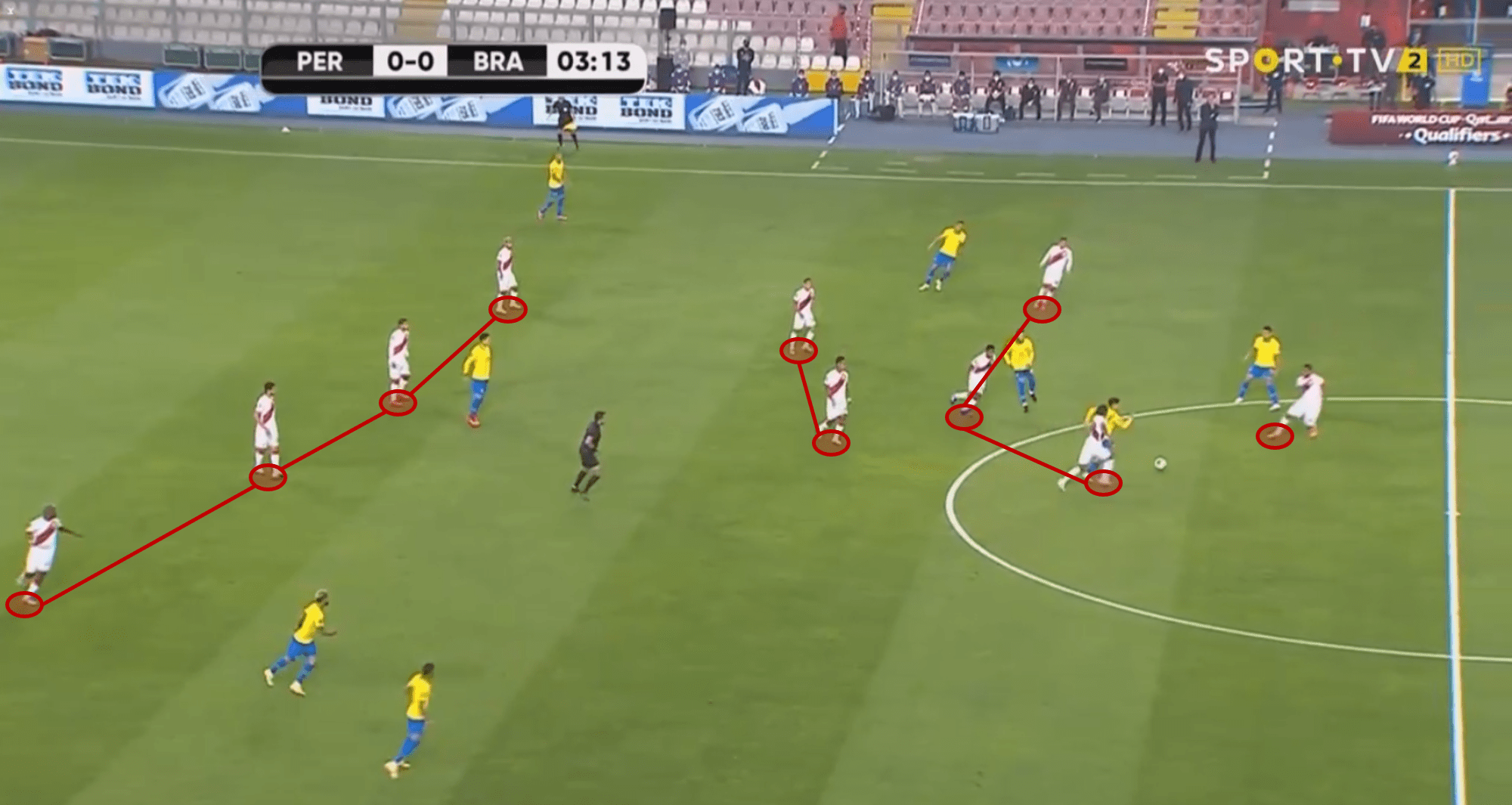

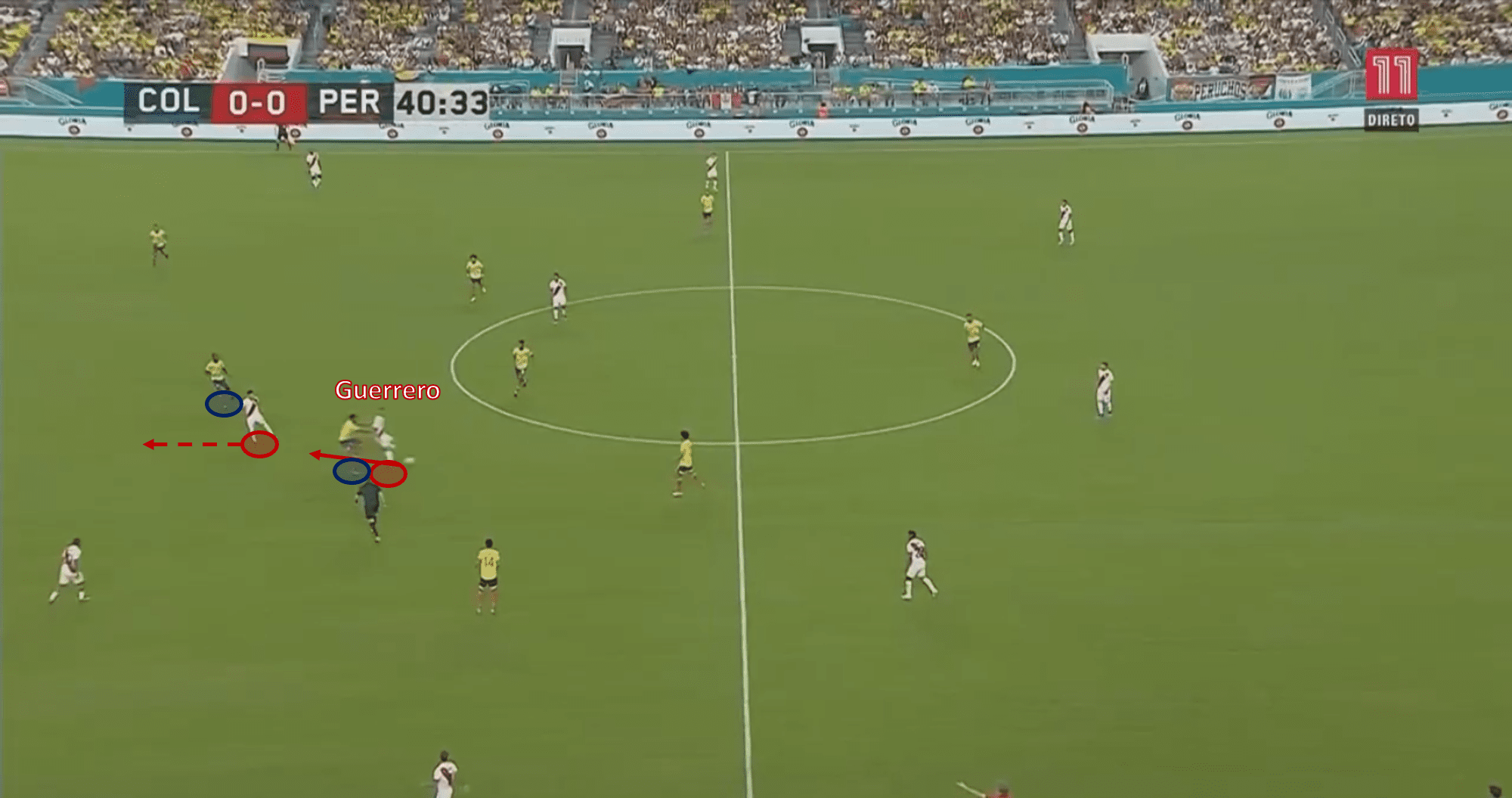

We see here Peru pressing from the front – one man pressing the ball and another cutting off a potential passing lane.

When the ball breaches the first line of the press, the wingers will drop back and create a midfield bank of four, which usually becomes quite narrow. This is somewhat an area of weakness, as the Peru midfielders have been dragged around quite easily, making the out ball to the wide players fairly easy, exploiting the space beyond the midfield. Tapia then typically drops into the backline to create a back five, and sometimes more players will drop to protect the goal too. The problem is that this invites pressure and creates scenarios where they drop further and further back and do not apply pressure to players of real quality on the edge of the area, where they can shoot on goal.

Here we can see Peru pressing in a 4-2-3-1 formation in action.

To improve before the tournament arrives, Peru must become more active in their defensive duties inside and around their own area. They cannot allow players in the ilk of a Neymar, James Rodriguez, or Coutinho to shoot from these areas because they will punish you. Pushing Tapia slightly higher in these scenarios could be the solution. His solid 1v1 defending could at least force opposing attackers to pass sideways to forge an opportunity rather than just shoot immediately.

TRANSITIONS

In the transition on the attack, Peru are quite direct in their approach. They aim to advance up the pitch as quickly as possible through the use of long balls if the possession is recovered in the midfield, and when they win the ball upfront, the idea is to hold up the ball and pause for the supporting run to follow shortly after. Both of these attacking methods require bundles of energy and quick decision-making, which can be a struggle for some of Peru’s older forwards.

Hitting Argentina on the break; Peru, unfortunately, were outnumbered here five to two.

Most frequently, Peru will look to regain possession as far up the pitch as possible, utilising multiple players to press the ball at once. Paolo Guerrero is crucial here once the ball is won back. He is generally excellent at holding up the ball, allowing time for Peru’s attackers to get into space, and he possesses good short-passing and link-up play to find them at the right moment. This has earned the likes of Carrillo and Farfan bagfuls of goals over the years.

Guerrero here gets the ball played into feet, which he smartly flicks past the defender behind him for a smart through ball to his fellow teammate.

From a defensive perspective, they do not engage too heavily in counter-pressing, rather opting to drop deeper and close passing channels where possible, attempting to regain their compactness. This has its strengths and weaknesses as with all tactics in football, but for this Peru squad, it does suit them, as they do not have the quickest defenders on the international stage, meaning counter-pressing could see them punished regularly if not careful.

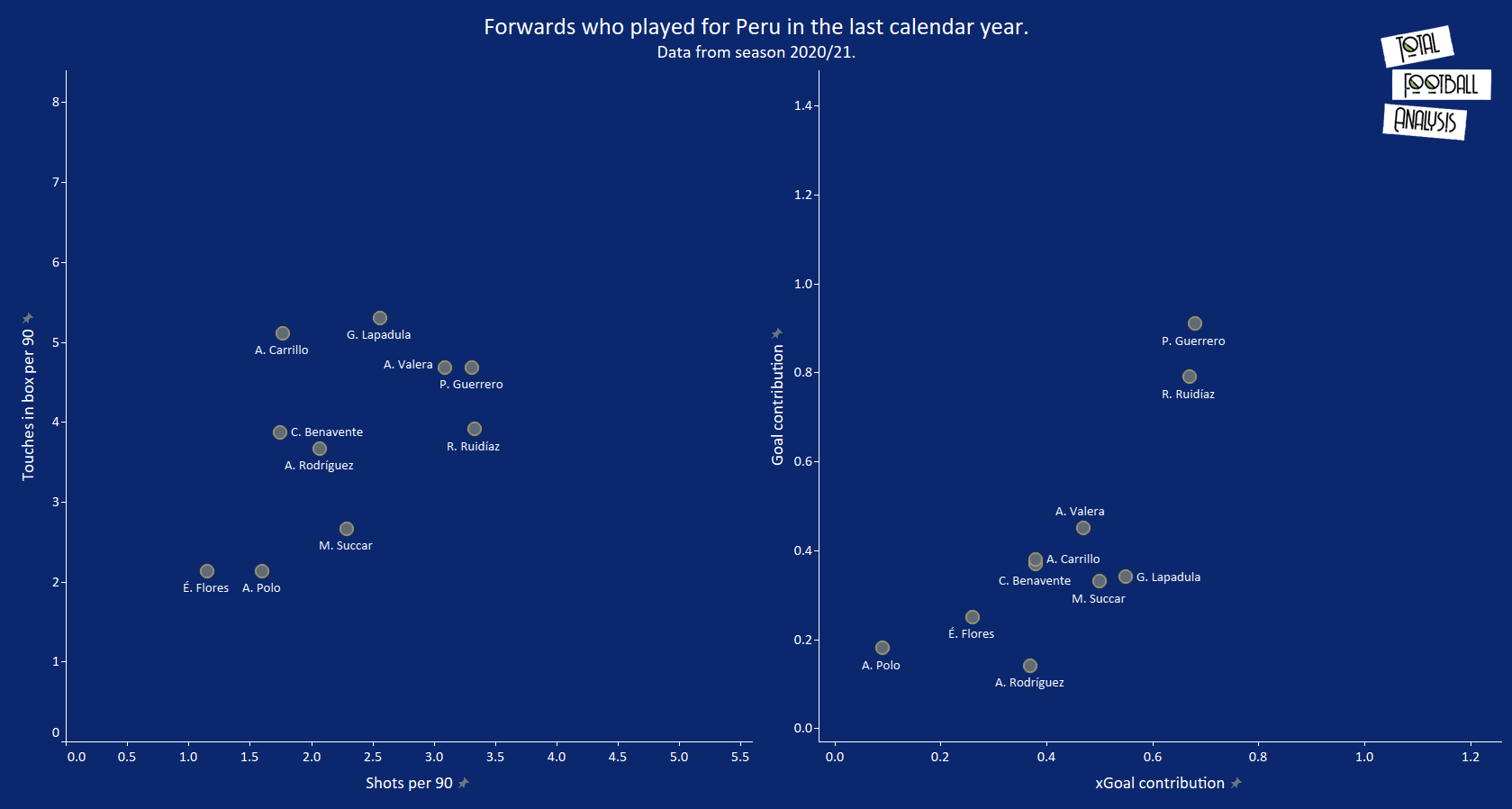

FORWARDS

In both of these scatter plots, we can see two leading figures at club level at least. Paolo Guerrero in limited minutes is proving that he can still produce at the ripe age of 37-years-old, scoring five times and assisting twice in only five matches in the 2020 season in Brazil. This, after scoring 10 goals in the season prior shows that the physically adept striker is not yet finished at the top level. Raúl Ruidíaz is another player who has excelled at club level in more game time at Seattle Sounders. In the 2021 MLS season so far, he is scoring at a rate of 0.83 per 90, and in fact, he averages 0.74 goals per 90 since his arrival in the American state in 2018. Nevertheless, he does not entirely suit Gareca’s system, with the coach opting for a more physically well-built operator who can hold up the ball and possess good link-up play. Add to this Ruidíaz’s poor goalscoring record on the international stage and it is hard to see him start at the tournament.

There are other players who put up decent statistics as well. Serie A journeyman Gianluca Lapadula has scored eight and assisted twice for relegation-threatened Benevento, which is a capable return for a side that struggles to create chances. He has played in all but one Serie A fixture this term (36 appearances) which also demonstrates his importance to Benevento coach Filippo Inzaghi, who happens to know a thing or two about good strikers. Again, weighing in at under 70kg, Lapadula does not provide Gareca with the physical presence upfront that he demands from his centre-forward. Could be a useful bench option.

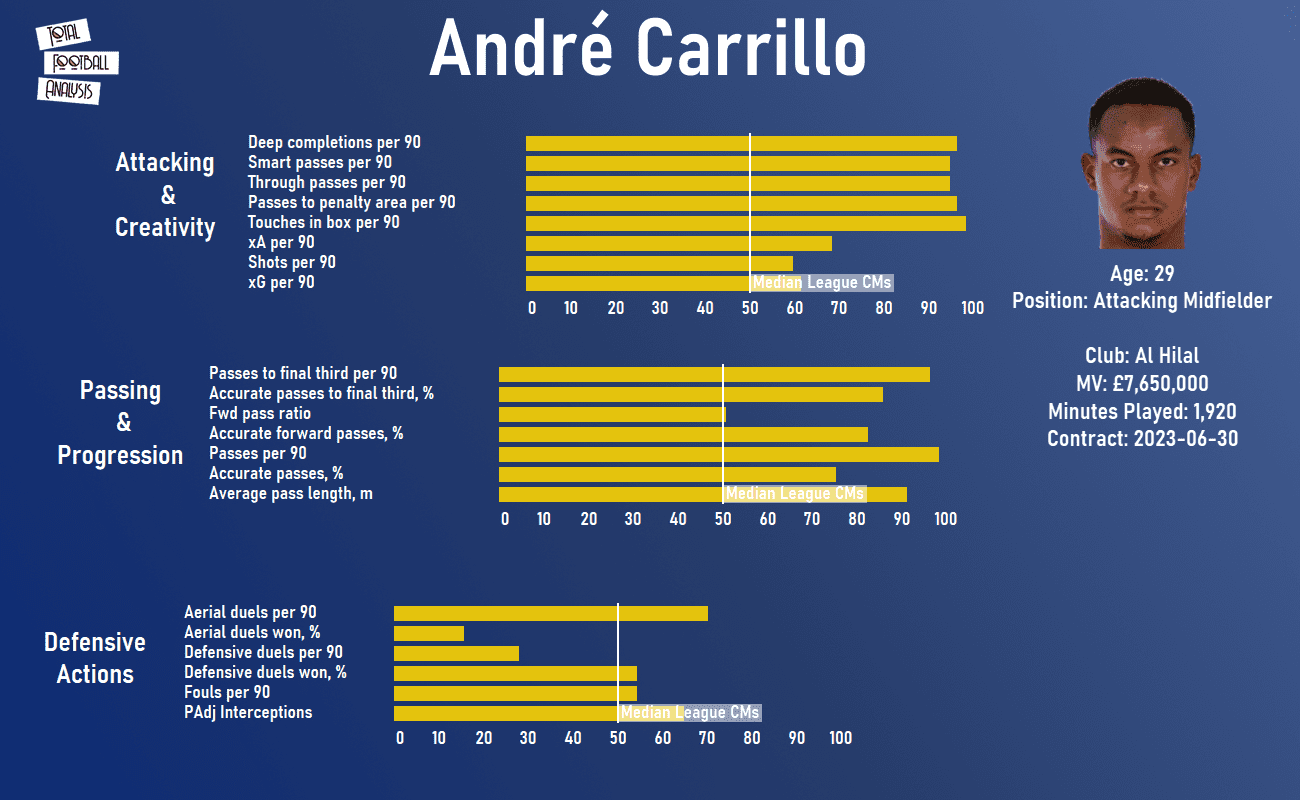

A player that shined at the 2018 World Cup, André Carillo, has been putting up some good statistics for perennial Saudi Professional League winners Al-Hilal. It seems as if Carillo saves his best performances for the international stage, after struggling to make any significant impact with Watford, before going on to shine at the World Cup. Seven goals and six assists in 24 matches is a good return, but vying for the best team in a historically weak division, you expect more given the talent he clearly has. Still, he features in the Saudi team of the season for a reason.

MIDFIELDERS

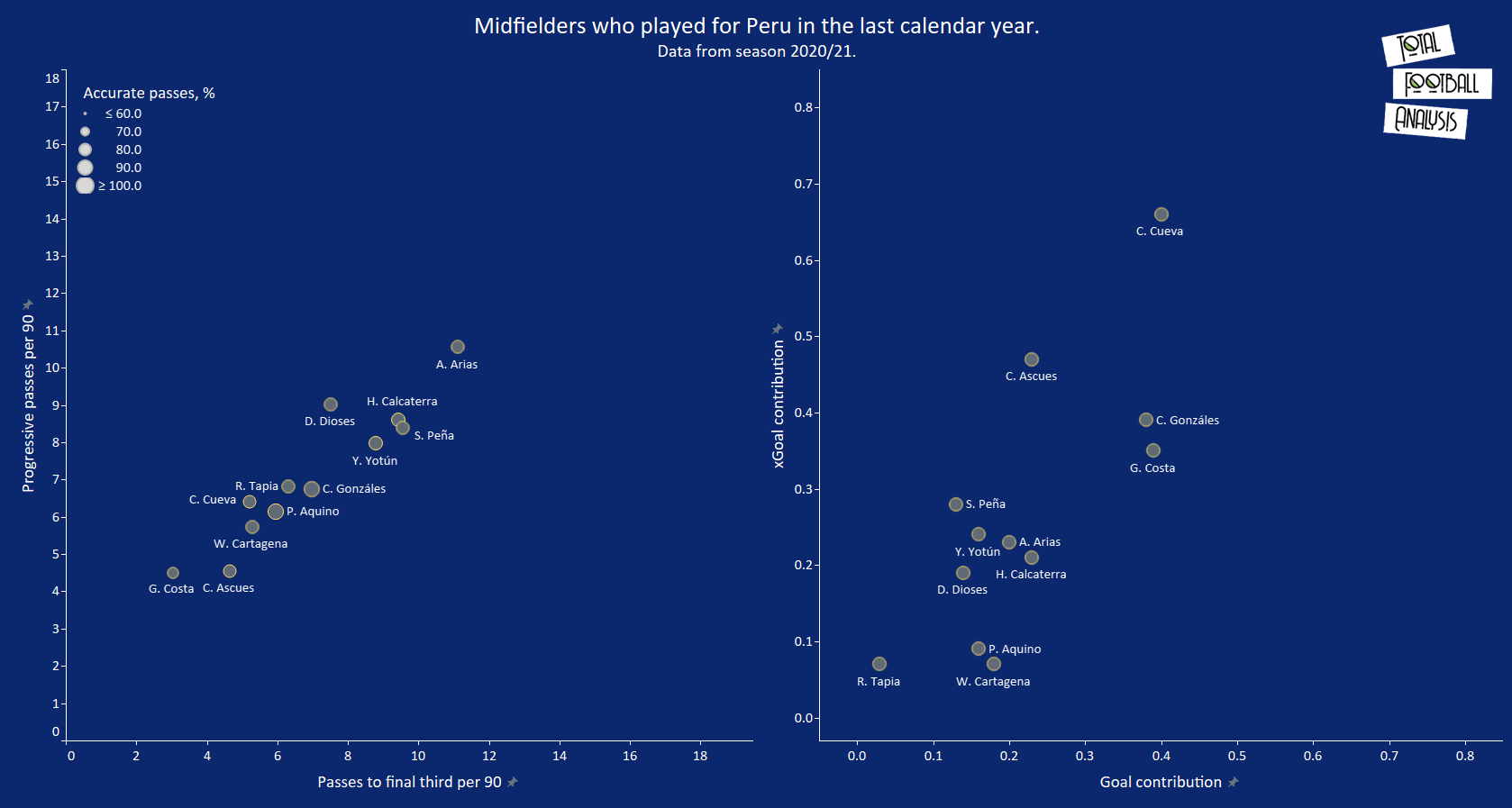

When we start to view the midfield, we understand there is a dearth of talent in this area of the pitch. Peru do have Renato Tapia, a strong, tactically flexible, intelligent defensive midfielder, but ball progression is not his strong suit. 2.97 progressive passes per 90 is only good enough to rank in the 23rd percentile of all midfielders across Europe’s top five leagues (according to FBref.com, with data provided by StatsBomb). Peru do have Alexis Arias who ranks highly for both metrics displayed here, but the 24-year-old is not expected to start. Yoshimar Yotún is slightly more capable than Tapia in this regard, but his starting position in this team is not guaranteed. However, in terms of squad composition, perhaps it should be.

Looking at the goal contributions metric, Christian Cueva leads the way generally, and he has had a solid season this year with Al-Fateh in the games he has managed to play. He has traversed the globe in recent seasons, moving to a new club every season since 2018, travelling from Russia to Saudi Arabia with Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey sandwiched in between. Nevertheless, 1.21 goal contributions per 90 for Al-Fateh is a stark improvement upon his brief spell in Turkey, and he finds form just at the right time to become a nailed-on starter for his national side.

Pedro Aquino is another player of genuine ability, but his profile is awfully similar to Tapia. Perhaps Gareca will start them both in hope that will provide enough protection for the back four, and aim to build up through the full-backs instead. It is one-dimensional, but it could be their best bet at securing progression through the pitch. Christofer Gonzáles is another player who could have an impact and is one of Cueva’s only backups in terms of attacking midfielders.

DEFENDERS

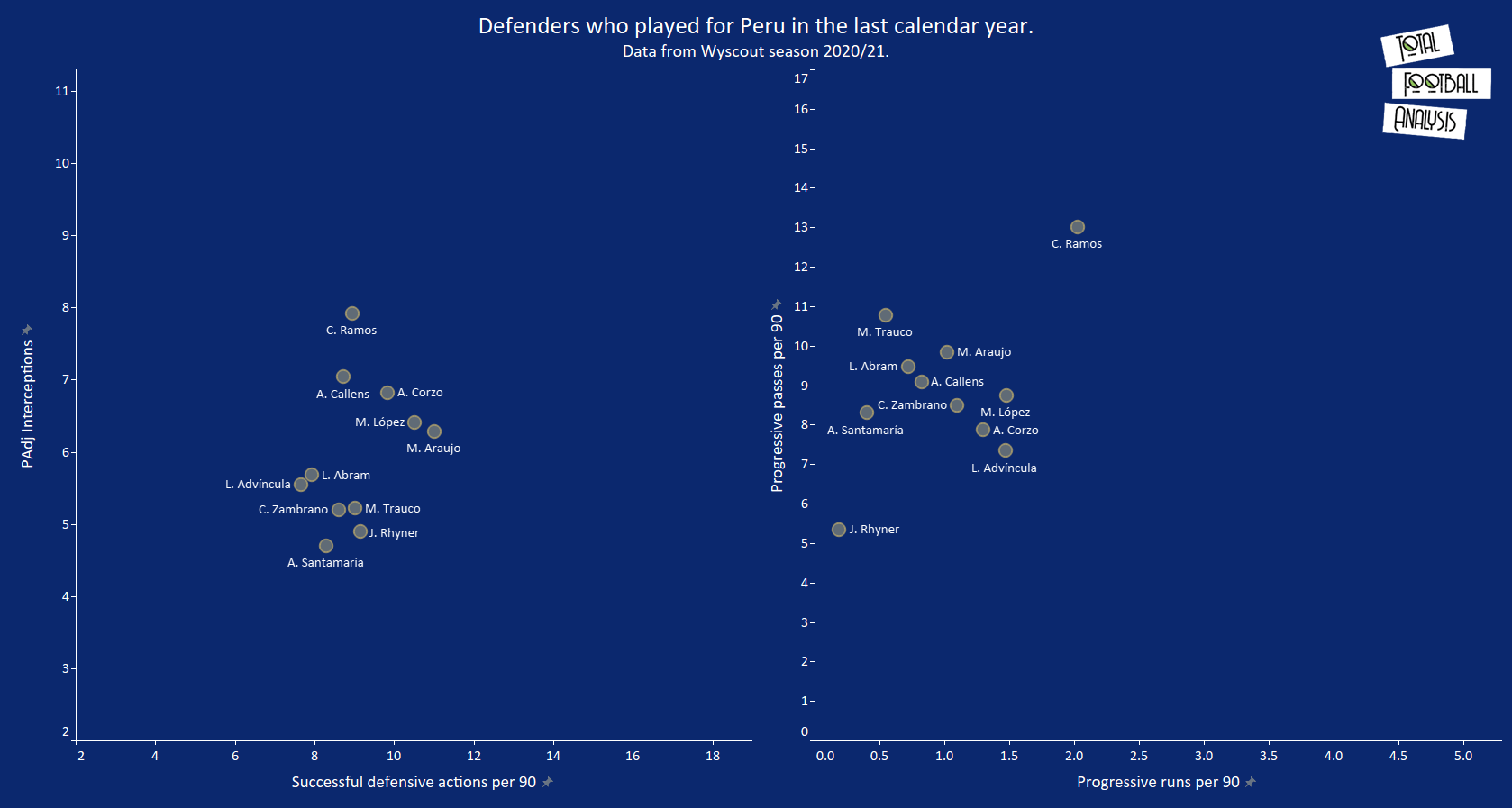

One player who stands out immediately is Christian Ramos of Universidad César Vallejo in the Peruvian League. He ranks highly for PAdj Interceptions and progressive passes, but also leads the Peru defenders for progressive runs per 90 too. He is a centre-back with 75 caps for the national side, but a couple of muscle injuries this season have coincided with him missing recent international fixtures. If fully fit, expect Ramos to start alongside Zambrano or Abram, but his starting position certainly isn’t fixed, despite strong club performances.

Beyond that, we can see Miguel Trauco’s benefits at left-back, with good ball progression numbers and decent defensive output. 0.12 xA per 90, 4.69 progressive passes per 90, and 1.77 interceptions per 90 is indicative of the full package at left-back, and Gareca would be wise to focus Peru’s build-up play through the Ligue 1 defender. Over on the other side of the pitch, Luis Advíncula remains a solid option at right-back. After being relegated with Rayo Vallecano in 2019, he remained in the neighbourhood of Vallecas. He is an active defender, really confident in the tackle, and a sliding one does not go amiss when the opportunity arises for Luis.

The rest of the defensive options are all decent defenders, but none of them shining in any particular regard. Gareca can expect to have a solid starting back four, especially with the full-backs, but strength in depth here is not something they maintain.

BEST PERFORMER

Under the hood, Carrillo has some fantastic attacking & creativity statistics. Featuring on the right-hand side of a 4-2-3-1 or 4-4-2 in a title-winning squad, aiming for target-man Bafétimbi Gomis in the box. He provides energy and dynamism down the right flank to the highest degree – despite being right-footed, he does not always opt for the overlap, often cutting inside and carving open the defence in the process. He is pretty integral to Al-Hilal’s ball progression, using his nimble ball-carrying abilities to good use in forcing the attacks into their favour. Beyond his ball-carrying, he also possesses excellent vision for a winger, consistently passing balls around the corner for later runners or Gomis. His xG and xA per 90 are sitting somewhere above average, but thankfully Gomis produces sensational output to cover this mini deficit.

From a passing & progression perspective, Carrillo demonstrates his excellence. He ranks highly for passes into the final third per 90, his accuracy in such passes, accurate forward passes, passes per 90, and average pass length. Interestingly, Carrillo is involved heavily in Al-Hilal’s build-up play, which is unique for a winger to be so involved, but his passing range and vision are being put to good use here clearly. Not only is he passing forwards with frequency, but he is finding his targets at a high-performance level too, indicative of his passing quality.

From a defensive perspective, Carrillo is not exactly active in this regard. He does win a decent proportion of his defensive duels, but the quantity of these efforts is low. However, he has an understanding of how to operate out of possession in a 4-2-3-1, which is extremely useful for him nailing a starting position for Peru since they operate with the same formation. Under Gareca, he will have to put a shift in defensively, especially when they face South America’s greater sides, where they will remain under the cosh for the full ninety minutes.

PREDICTIONS FOR THE TOURNAMENT

It will be tough for Peru at the 2021 Copa America. Getting out of the group stage would make for a successful tournament based on current form. However, something else suggests that Peru do perform on the grandest stage, more so than they do in qualifying, so another run towards the final should not be ruled out either. They will need to find a way to perform better against the tougher opposition first, however, and they have little time for preparation.

Comments