Uruguay are a national team who are very much at the end of a golden generation. In the previous decade they returned back to some of their former glory across many competitions, with some of their highlights including a fourth-placed finish in the 2010 World Cup, reaching the Quarter Finals of the 2018 World Cup, and of course their famous Copa América win in 2011. All of these successes were overseen by long-serving manager Óscar Tabárez, and with 74-year-old Tabárez’s contract expiring in 2022, this could well be the last Copa América for ‘El Maestro’.

The golden generation of course doesn’t end with coaching, and the majority of Uruguay’s key performers are now at the end of their careers. The three main stalwarts of the side, Diego Godín, Edinson Cavani and Luis Suárez are all 34 or over, and so for these players it could well be their last Copa América also. Captain Godín is Uruguay’s most capped player ever with 139 appearances, and Cavani and Suárez follow closely in third and fourth, and so the experience running throughout this squad cannot be questioned. Suárez and Cavani are also at the top of Uruguay’s goalscoring records, with Suárez leading the way with 63 goals in 113 appearances. Both of these strikers will be looking to add to this tally in the upcoming tournament.

Uruguay are often labelled as a dark horse in these tournaments because of their awkward playing style and tenacious attitude, but it is worth remembering that Uruguay are the most successful team in Copa América history, with 15 wins under their belt. This success was of course seen in the early 20th century, where Uruguay’s dominance helped them to dominate not only South America, but the World Cup on two occasions famously, including winning the first ever World Cup as host nation.

For this year’s Copa América, Uruguay are in Group A, and so will play games against Bolivia, Argentina, Chile, and Paraguay. Uruguay came out comfortable winners over Chile in a World Cup qualifier in 2020, and have not played Argentina or Paraguay in a competitive game in the past two years. A fixture that will stand out for Uruguay is their match against Peru, who knocked Uruguay out of the 2019 Copa on penalties in the Quarter Finals. ‘La Celeste’ will therefore be looking for revenge over Peru, who managed to make it all the way to the final that year before losing to Brazil. This scout report will use tactical analysis to examine Uruguay’s playing style and overall chances at the tournament.

THE SQUAD

Goalkeepers

Martín Campaña

Rodrigo Muñoz

Martín Silva

Defenders

Ronald Araújo

Martín Cáceres

Sebastián Coates

José Giménez

Diego Godín (c)

Agustín Oliveros

Damián Suárez

Matías Viña

Midfielders

Mauro Arambarri

Rodrigo Bentancur

Giorgian de Arrascaeta

Nicolás de la Cruz

Nahitan Nández

Lucas Torreira

Federico Valverde

Forwards

Edinson Cavani

Maximiliano Gómez

Darwin Núñez

Jonathan Rodríguez

Luis Suárez

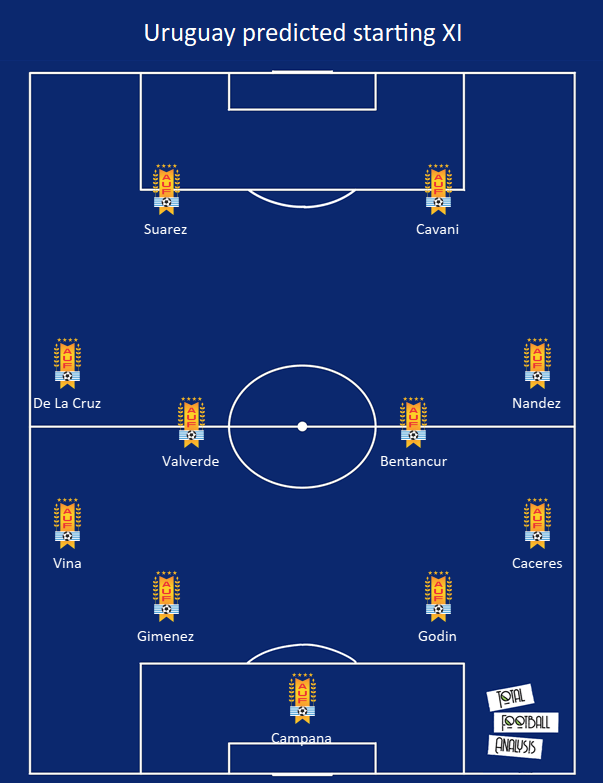

Uruguay’s starting eleven is not completely set in stone, but their consistency in tactics and team selection allows you to make some safe bets around who is likely to start. I would expect them to use their much used 4-4-2 for the majority of the tournament, and this has been used in 44% of matches in the past calendar year, with the 4-1-4-1 used when missing one of those key strikers often. The much tested partnership of José Giménez and Diego Godín will surely be seen again, with this partnership easily one of the best in world football. Uruguay’s 8th most capped player Martin Cáceres, who currently plays for Fiorentina in Serie A, will likely slot in at right full-back. Matias Viña will likely make the eleven at left-back, although there has been more rotation around this area. Palmeiras full back Viña though has started in the majority of recent matches.

The midfield is where the real decisions will be for Tabárez, who is spoilt for choice in central midfield. I have chosen Federico Valverde and Rodrigo Bentancur as the starting two within a 4-4-2, as they have played at a high level for their clubs this season. As I mention though, Uruguay are blessed in this area, and have very good options such as Lucas Torreira and Matias Vecino, who has been side-lined for a large part of the season through injury. Lucas Torreira has been excellent in a Uruguay shirt at big tournaments, with his performance in the 2018 World Cup no doubt playing a part in his move to Arsenal, however he has struggled for minutes in the past year also, and so I have put Real Madrid midfielder Valverde in just ahead of him. Uruguay have used a 4-1-4-1 and a diamond shape at times in the past, and so this could be used to allow more of these central midfielders in the team. The 4-1-4-1 though of course forces either a striker out of the team which is unlikely, or forces Cavani to act as a winger at times.

For their wingers, the biggest area of contention seems to be between Nicolás De La Cruz and Giorgian De Arrascaeta. River Plate midfielder De La Cruz was preferred in more recent competitive games, but De Arrascaeta is a top performer for Flamengo in Brazil, and so it is difficult to guess who will start between those two. Nahitan Nández, a feisty midfielder currently plying his trade for Cagliari, is likely to start on the right, and his attitude and characteristics as a player massively suit Uruguay’s famed style of play. Finally, as you would expect, barring no injuries, Cavani and Suárez will start.

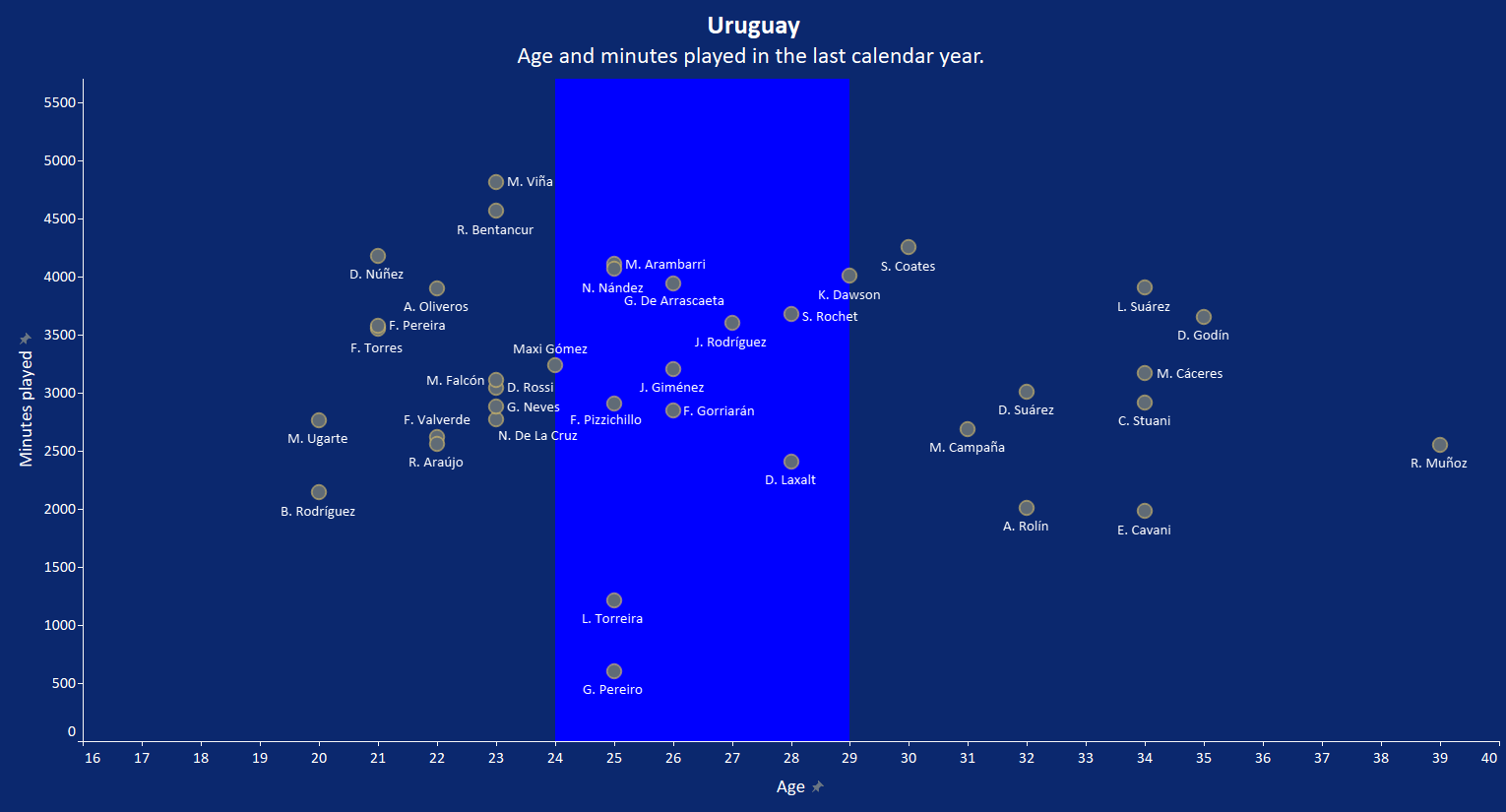

Here we can see a graph showing the age of the squad and the number of minutes played in the last calendar year. Again we can see the relative age of their squad and that many of their players are not seen as being in their prime statistically. Of those players in the prime ages, only Nández, De Arrascaeta, Giménez and Laxalt have ever really been regular starters for the National side. Despite their age, Godín and Suárez have played a large number of minutes in the past year, and although they are slowing down, they are both still capable of playing at the highest level. Cavani has had his minutes managed quite well By Manchester United, and so we see him lower down on the graph. Lucas Torreira is also very low down on this graph with the midfielder missing out due to injuries and just not being selected, and we can see a contrast between this and the likes of Rodrigo Bentancur, who managed almost 3500 more minutes.

They do have some youngsters coming through, with the likes of Darwin Núñez being a real case for excitement. Bentancur and Valverde are both in their early twenties also, but replacing the goals provided by that deadly strike partnership is likely to be the main issue for Uruguay in the next decade.

ATTACKING PHASE

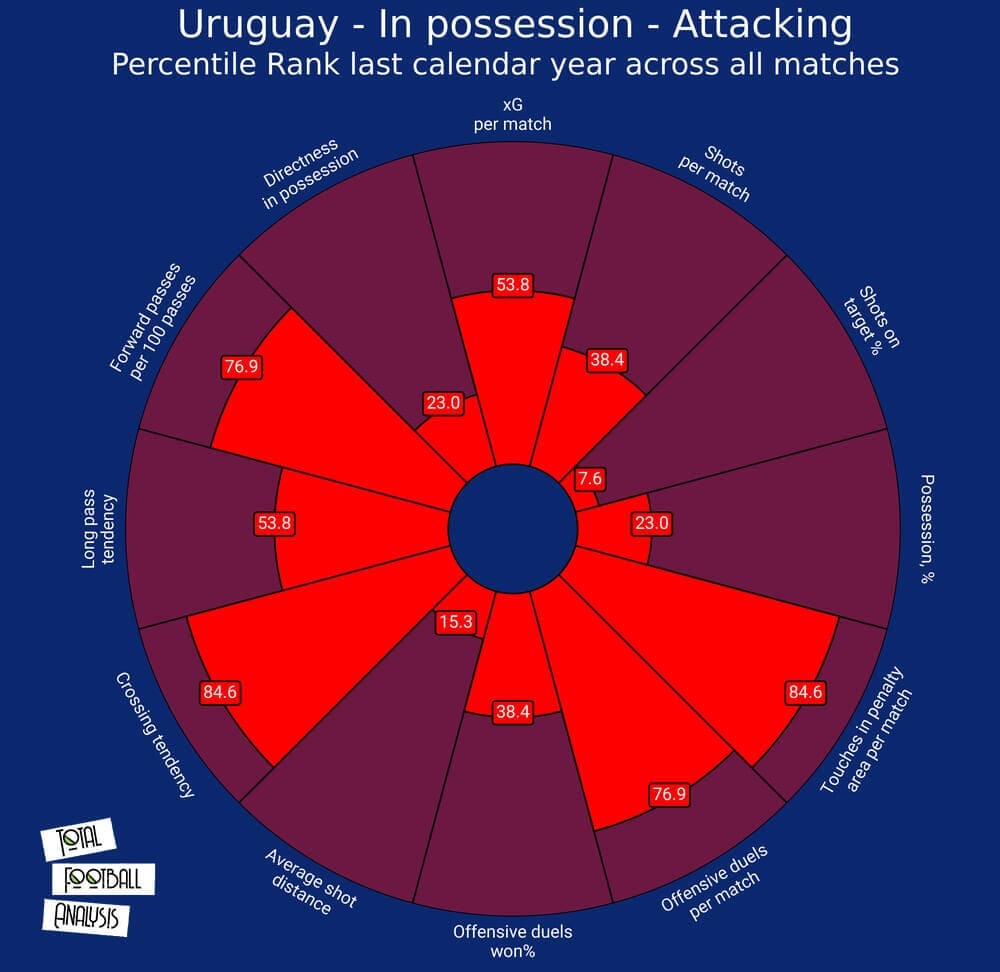

Uruguay are a team who generally struggle offensively, and although their xG per match metric seems fairly average, in the past calendar year it has been very reliant on penalties. Uruguay do their best offensive work in transition, which naturally complements their deeper defensive set-up. Uruguay don’t look to dominate possession of the ball, and when in possession look to play quick, dynamic football. As we can see in the chart, they play a high number of forward passes and compete in many offensive duels. A key aspect of their offensive play is their use of crosses, which are used to take advantage of the two strikers’ excellent movement in the box.

Their shots per match are low, however this is to be expected from a team who look to sit in a deeper block, with this obviously impacting on their ability to create shooting opportunities. When they do create shooting opportunities, they have the offensive quality to take them, and so although their shots on target percentage is low, they are still able to score what few chances they take.

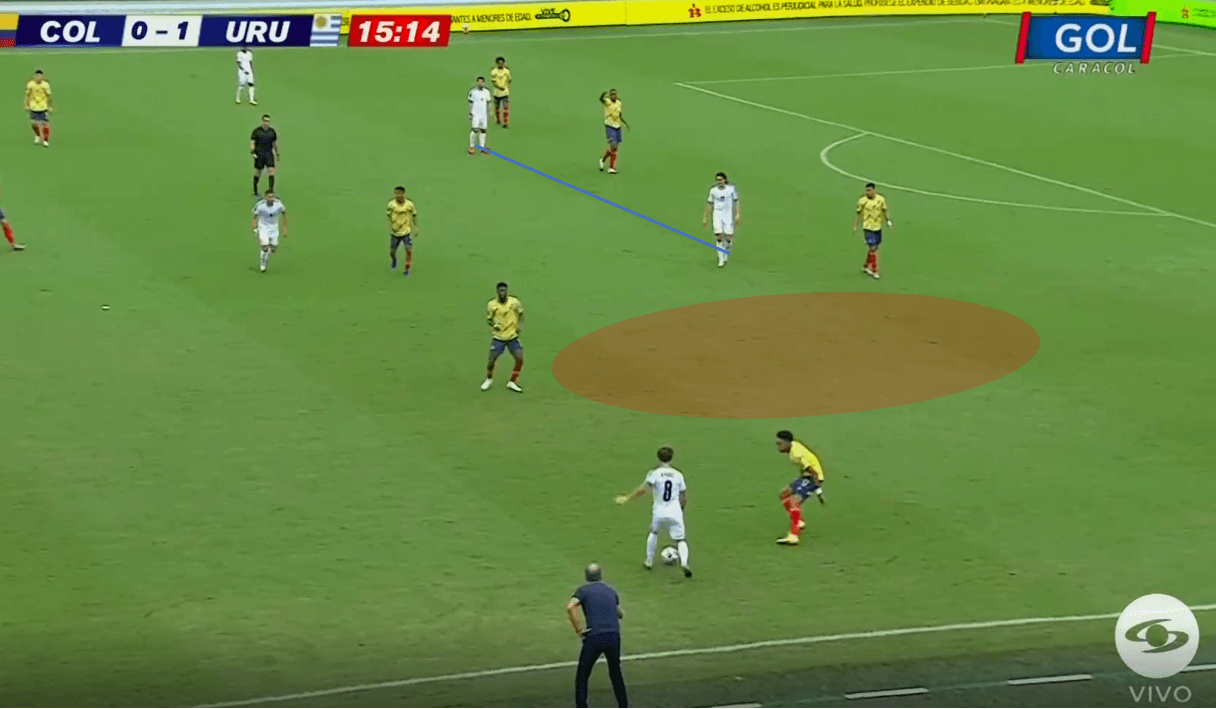

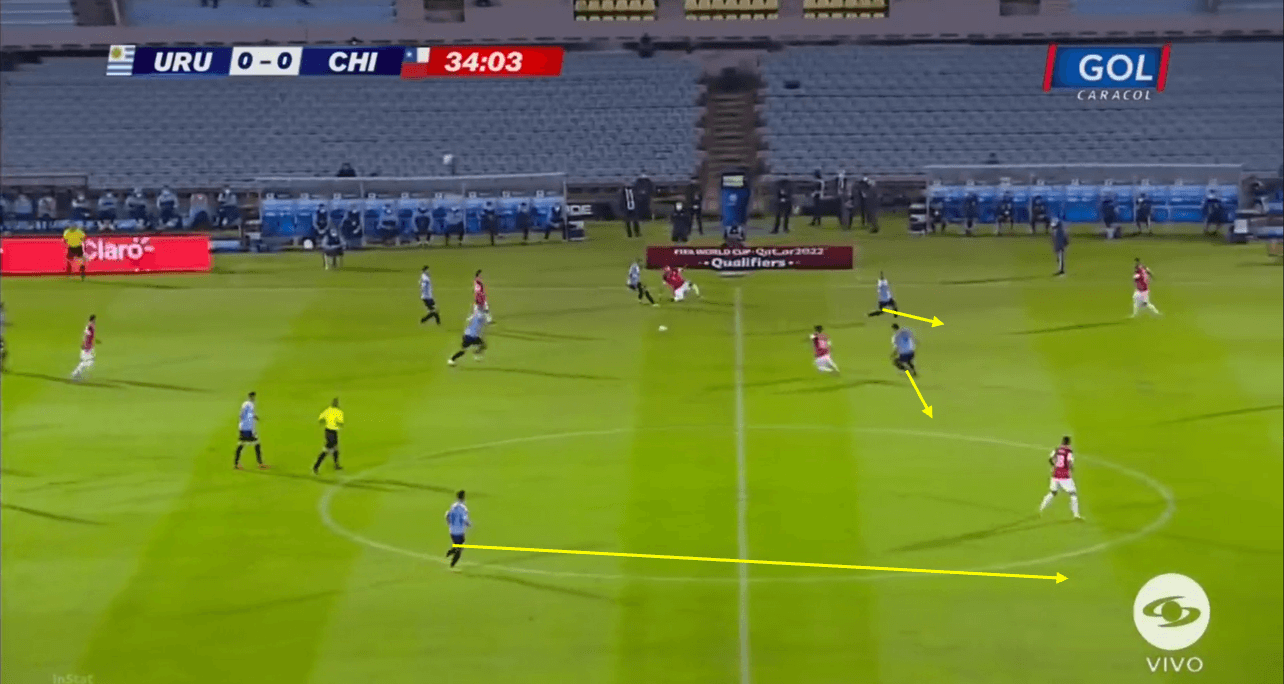

Uruguay’s attacks are quick and look to access the strikers where possible, but with the opposition often guarding the centre well, they can be forced onto the wings. Full-backs will push on during longer possession phases, but Uruguay will often be forced to keep their wingers wider to receive the ball. Strikers drop between lines at times, but because of Uruguay’s focus on crossing, they often want to stay centrally to have a chance of attacking the ball, and so if central midfielders support the ball poorly (which they often do), Uruguay can be contained in the wider areas. We see here how no occupation of the half-space, as well as no central midfielder arriving from depth, means that Nandez has no options and has to play backwards.

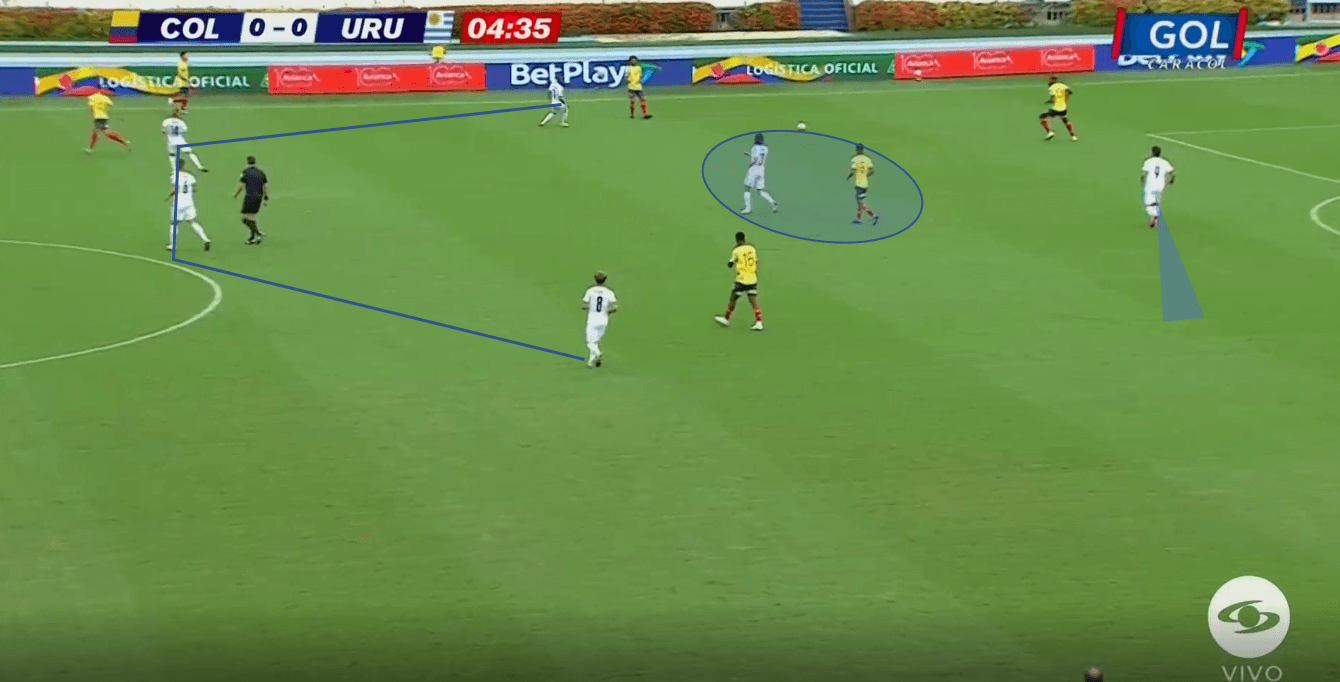

We can see a better example of their offensive play here within the 4-4-2, where their full-back is able to push on into a wider area, which allows the winger to move into the half-space. The winger receives dynamically and is supported by Suárez, who also starts deeper so he can arrive onto a through pass behind the defence. Cavani will then maintain height to the attack, and takes up his usual position between full-back and centre back, while the far winger can also support.

Because numerical superiority is rarely created by them, they have to rely on other methods such as dynamic superiority through wingers to progress the ball. Wingers dribbling to cross is a key method of progression which can be used, and even if they do not reach a striker, their two combative midfielders are usually on hand to counter-press within reason. These crosses are reliant on the movement of the two strikers, who use tactics such as stop-start movements and positioning on the blindside of defenders to create separation to win a header. Cavani and Suárez are both extremely street wise and clever in the use of their bodies, and so win fouls further up the pitch which allows Uruguay set-piece opportunities.

DEFENSIVE PHASE

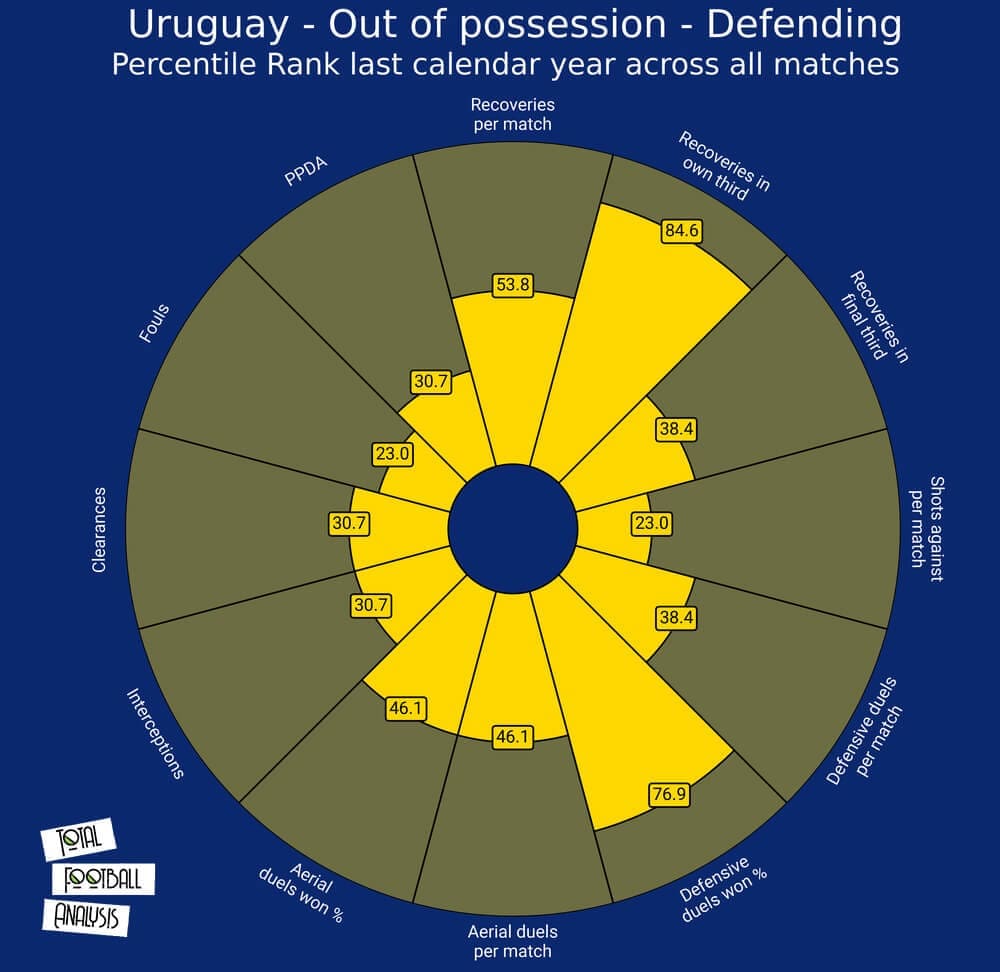

Uruguay’s approach defensively is consistent and usually effective, although its impact on their offensive game has been shown. They are a team that operate in mid or deep blocks, and focus on organisation and compactness to prevent the opposition from progressing the ball. The number of recoveries in their own third tells the story of their deeper defensive approach, as does their shots against per match metric. Uruguay do not look to press high, and would struggle to do so as a result of their forwards’ mobility, particularly Suárez who no longer has the stamina or acceleration often to press intensely.

Their defensive duels won percentage showcases both the defending skills of the Uruguay players, but also the overall compactness of the team, as we see that not many defensive duels actually occur. This speaks to the fact that opposition players simply don’t have the space to initiate a ‘duel’, as the compactness of the Uruguay side means there isn’t space to dribble into. To progress through Uruguay, you have to have a good positional play structure that seeks to manipulate their shape, and also have to have technically proficient players who can receive the ball in tighter areas. Their aerial duels faced are quite low, which again is to be expected considering they are not pressing teams into playing longer passes, and so it would be illogical for teams to play longer, more vertical passes against a deeper block.

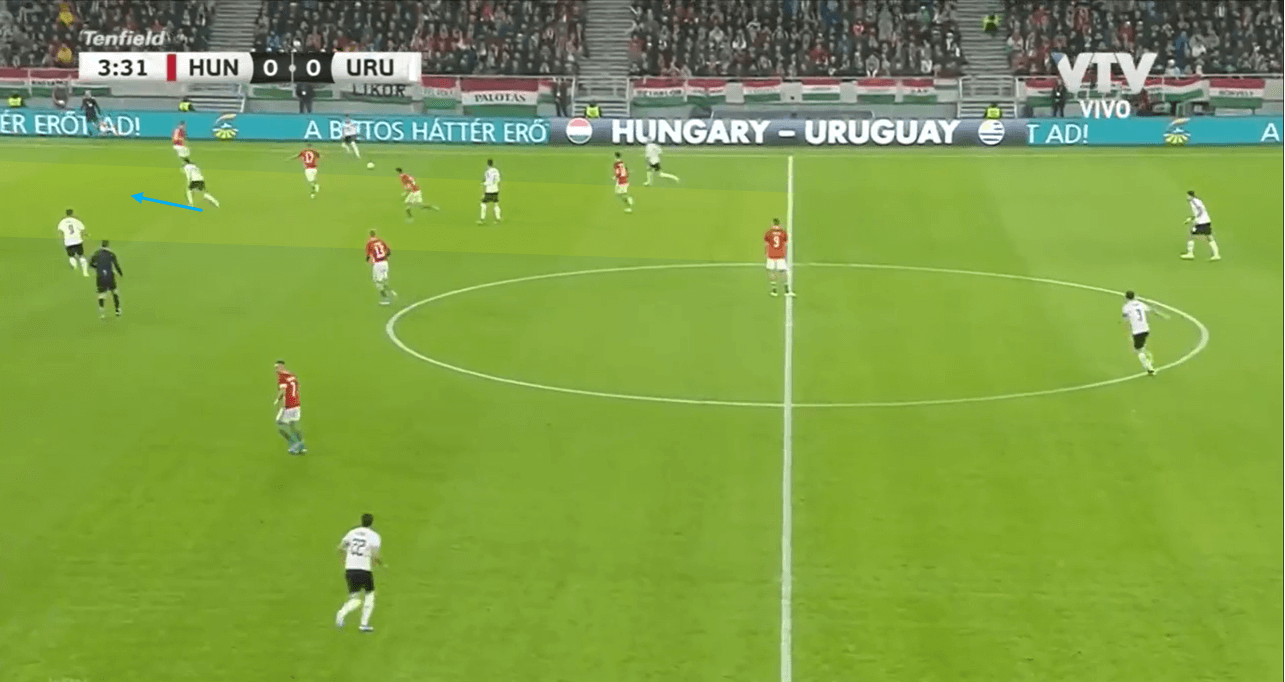

As mentioned earlier, Uruguay’s most favoured formation is the 4-4-2, although they have used such variations as the 4-diamond-2 as well as a 4-1-4-1. The aim of any of these structures is to remain in a compact shape centrally and limit ball progression by forcing the opposition wider. A key aspect of any modern side while defending is their coverage of the half-space, and Uruguay’s central midfielders often look to stay as zonally oriented in this space as possible, as we can see in this example.

Uruguay’s 4-4-2 often becomes a 4-4-1-1 in shape, as Edinson Cavani will often be given the role of covering the nearest opposition pivot. This not only seeks to prevent a midfield overload, but also the effect that a midfield overload could have. If the ball near central midfielder is forced to press outwards in a more central position to nullify an overload, this naturally decreases their coverage of the half-space. By allowing Cavani, and sometimes Suárez to cover one or both opposition pivots, it allows the nearest central midfielder to act more zonally, and basically gives them less responsibility, allowing them to focus on covering the half-space.

Some teams use a 4-4-2 in this way, but use central midfielders in a more man-oriented way. This allows more pressure on the ball and prevents free passes into players, but it allows you to be manipulated more easily, and can open the half-space. Torreira here stays in the half-space despite a player moving wider, and instead allows the full-back to press forward to cover this option. As a result, it is more difficult to open the half-space for the opposition. If Suárez presses centre backs from the front, he is able to cut this option off further, but this option is rarely available due to Suárez’s lack of pressing generally. The winger stays narrow for as long as possible to further cover the half-space, and will jump out to press wide if the ball is played.

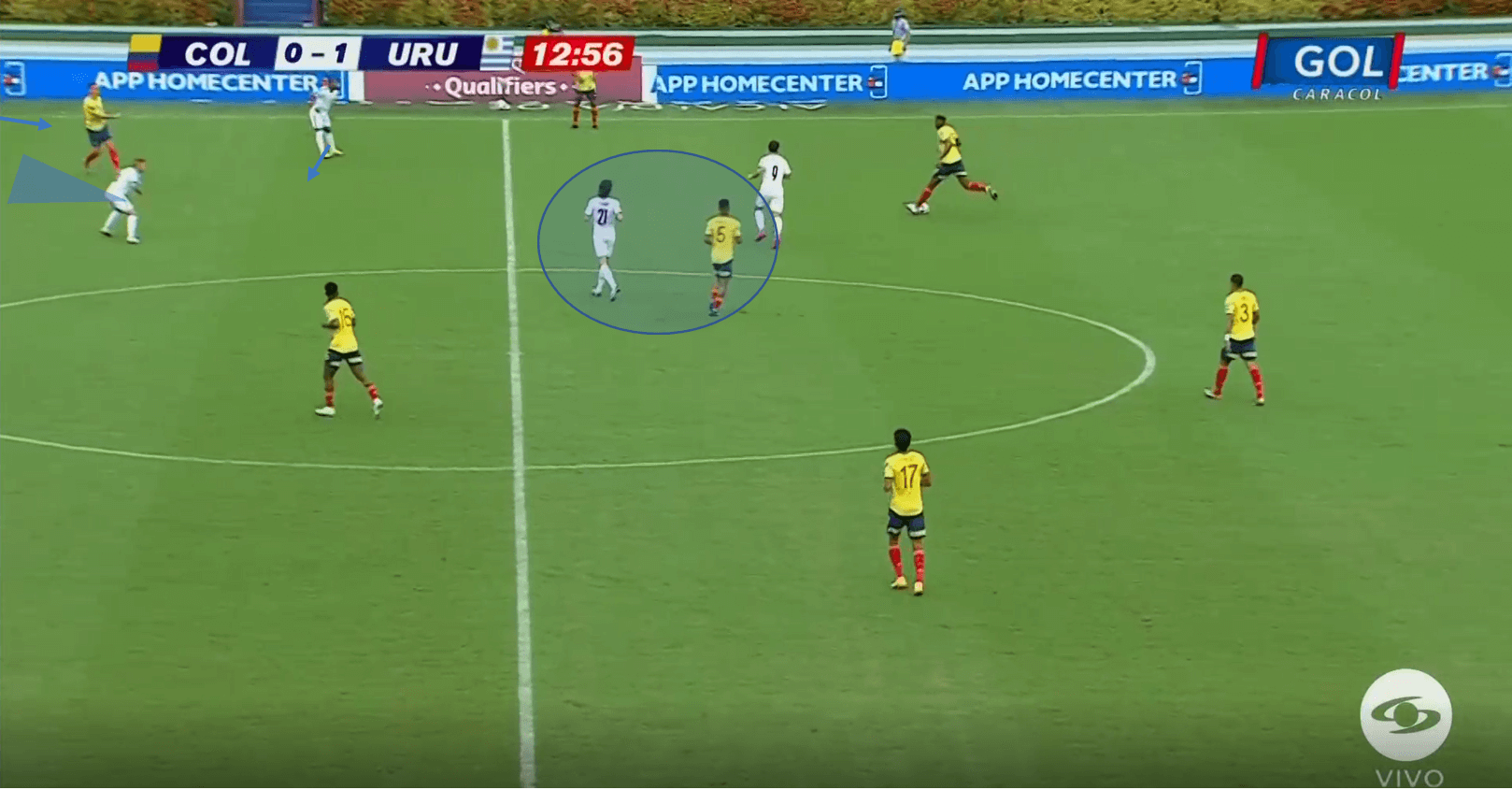

We can see a similar example here, where the 4-4-1-1 structure adjusts slightly, with the centre back not under direct pressure, but with passing lanes cut off. The winger has pressed the ball wide and forced the pass backwards, and we see Suárez again doesn’t apply pressure on the ball, and instead now cuts the lane to the opposite centre back. This prevents a switch in play, which would harm Uruguay’s compactness, and so Colombia are forced to play into Uruguay’s compact midfield structure. Colombia actually play a diagonal into their far pivot, who is covered by Uruguay’s right winger, clearly showing their narrowness out of possession. They are able to be this narrow again because of Suárez’s positioning, as any switch in play would have to be a longer pass which takes longer to get there, and would allow Uruguay time to shuffle. Colombia play a poor pass into the player, Uruguay can steal the ball and within one pass Cavani has scored in the box.

TRANSITIONS

In transition, Uruguay rely on the hold up and combination play of the two strikers, who combine well and are supported by the two wingers, whose narrow positioning in possession can help them to get into good positions in transition. One of the two strikers will usually drop into a position to receive and progress play, while the other will provide height to the attack, and it is the quality of the two strikers’ that often allows them to be effective in transition.

Transitioning out of their 4-4-2 shape means that the centre forwards and wingers are usually only the real players who can join the attack. Uruguay will steal the ball in their compact block and immediately look to find one of the strikers usually, with this pass allowing the wingers to move forward in support. Again Suárez nowadays is a much slower player, and so accessing him early, or leaving him much higher to attack in the box is usually the best option. Suárez can turn and receive the ball and play excellent passes into onrushing teammates, and when on the last line, can make clever movements that make space for him or his teammates. Here he is kind of caught between those two roles, and so struggles to contribute to the transition, which then moves wider. If anyone remembers Uruguay’s first goal against Portugal in the 2018 World Cup, you will remember Cavani and Suárez linking up with simple longer passes, where Suárez stretched wide on the last line and found Cavani with an excellent cross. Positionally, their transitions are not unmanageable and good counter-pressing or rest defence structure or a higher line could help to nullify it, but sometimes technical excellence gets you through in transition, and that is something Uruguay have in abundance.

FORWARDS

Uruguay have a number of forwards who have performed fairly impressively this season, with Núñez boasting the most number of touches in the box per 90. Suárez performs slightly lower on this metric, but this is often determined by team playing style, and so Atlético Madrid’s often more defensive style naturally reduces this number. Cavani also has a similar number to his strike partner, and Cavani’s touches in the box for Manchester United tend to be getting on the end of crosses or the final pass being played into him, and so he doesn’t make too many touches in the opposition’s area.

In terms of goal contributions, we see statistically no players really stand out massively, but this isn’t to say they aren’t somewhat impressive numbers. Diego Rossi and Darwin Núñez are slightly ahead of the others, however they play in the MLS and Liga Nos respectively, and so this is to be expected. At the time of writing, Suárez has managed 23 goals this season from 15.36 xG, while in over 1000 fewer minutes, Cavani has registered 16 goals from 12.74 xG. Cavani is able to create such a high number from those minutes due to his excellent movement in and around the box, and so the positions he takes up lead to higher quality chances.

MIDFIELDERS

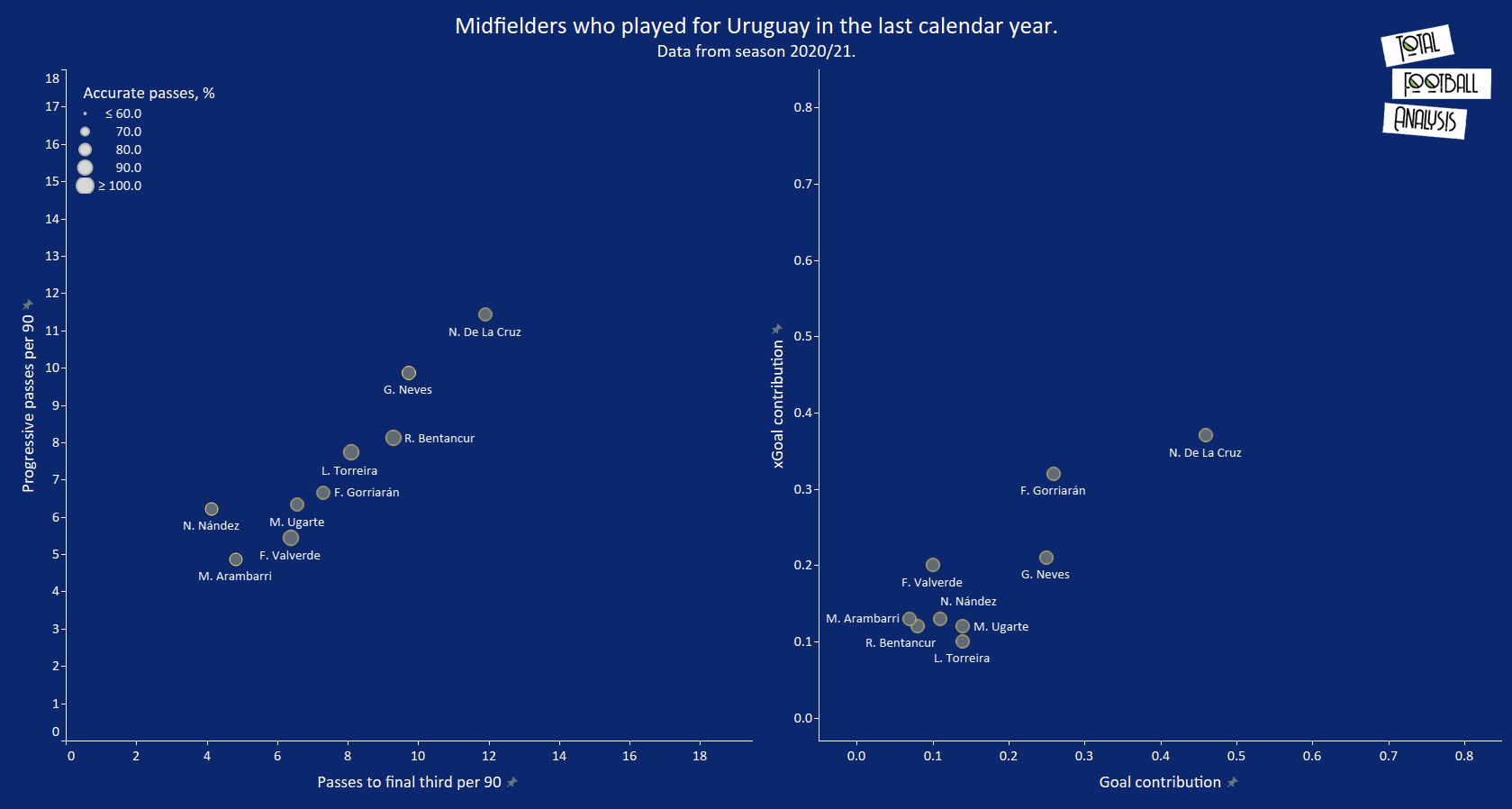

When looking at some statistics from midfield, you get a good idea of the profile of Uruguay’s central midfielders. When looking at progressive passing and passes to the final third, we see the likes of Fede Valverde and Nahitan Nandez are poor progressors of the ball. These players are better in the defensive side of the game, and for their clubs do not play roles that rely on them to progress the ball often. Lucas Torreira and Rodrigo Bentancur have slightly better numbers, but again do not show amazing numbers. De La Cruz stands out as the biggest offensive threat in terms of progressions and goal contributions, and so this could help him to get a place in the starting eleven.

DEFENDERS

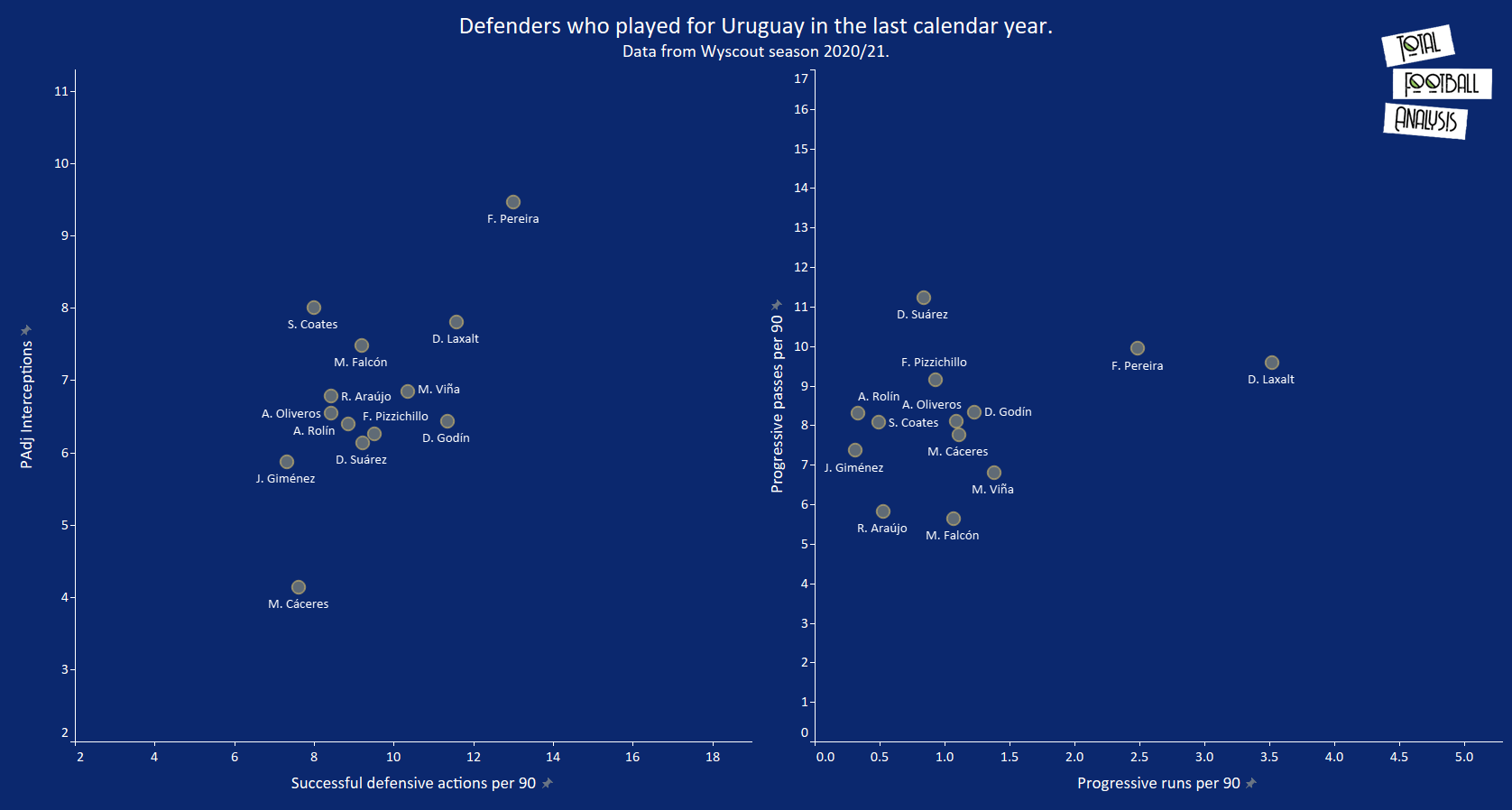

Defensively as stated earlier their back four is fairly pre-determined, with Giménez and Godín certain to start if fit. Godín performs a large number of defensive actions per 90, highlighting his role in the Cagliari defence while Cáceres and Giménez seem to perform less successful defensive actions. This stat is of course somewhat reliant on the number of defensive actions they actually perform. In terms of progressions, we see Diego Laxalt likes to run with the ball to progress it and has also been effective in passing. Laxalt has played for Celtic this season though, and so he is allowed a freer role than some other full-backs, due to Celtic usually dominating possession. Matias Viña performs a decent number of defensive actions, but his ball progression metrics are very low for a full-back, who has even played as a wing-back at times this season. 21-year-old Federico Pereira, who plays for Liverpool Montevideo in Uruguay has put up some impressive numbers both defensively and offensively, and this could put him in with a shout of making the squad. The level of competition he is playing at though does impact the impressiveness of his data though.

Neither of the two centre backs are particularly good ball progressors in their sides, but this is unlikely to be expected at either their clubs or in the National Team. They both will be relied upon for their defensive positioning more than anything, as well as their aerial ability from crosses, and with both players around the 60% success mark in aerial duels, they should be as reliable as ever.

BEST PERFORMER

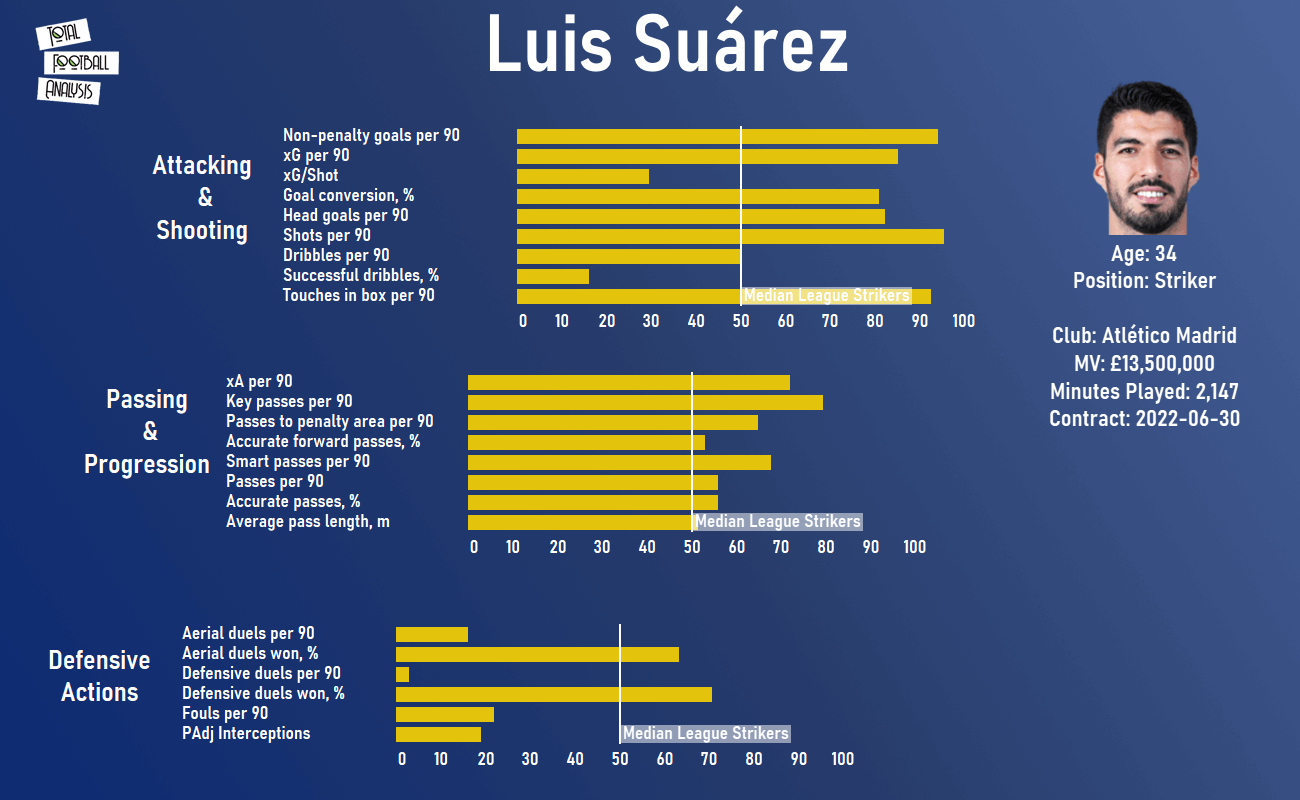

I’ve picked out Luis Suárez as Uruguay’s likely best performer, as even at the age of 34 he is one of the worlds best strikers. He made the move this summer from Barcelona to Atlético Madrid, and it will be one that Barcelona are now regretting, with Suárez impressing at Atlético this season and playing a massive part in their title win. Suárez has been an ever present in the Uruguay national team since his debut in 2007, and averages 0.54 goals per game for the National side, allowing him to overtake the likes of Diego Forlan in the scoring charts.

Suárez has of course slowed down from his prime physically, with his once world-beating dribbling skills allowing him to burst past players now limited by his pace. We can see in the chart here that his dribbling success rate has struggled and he is no longer attempting many at all. His positioning and incredibly intelligent movement has not faltered though, and so we see his non-penalty goals and expected goals per 90 are far above the league average. His expected goals per shot is noticeably low, which may be in part again down to the kind of team he plays in, but we see his conversion rate allows him to still score a very healthy number of goals.

In terms of his passing he is still performing relatively well, with his key passes and smart passes standing out. Suárez is unlikely to play too many passes into the penalty area, as he is often one of the last attackers for Atletico.

Defensively Suárez has slowed down a lot with his age, and he is now allowed to save his energy to be used on the offensive side. His defensive duels per 90 are incredibly low suggesting not too many pressing actions, which is to be expected when playing for the team with the fourth-highest PPDA in La Liga, which suggests a not very intense press. His aerial duels per 90 are low, however the aerial duels he does have he seems to perform well in, and Suárez has always been a player who can be combative in the air.

Suárez will look to link up with Cavani and rely on his intelligent movement to receive the ball, and his finishing ability allows him to score from low-quality chances, something Uruguay may have to rely on particularly when playing a more defensive system. Cavani often performs most of the work defensively, and so it will be interesting to see if or how this changes with Cavani having aged since the last major tournament.

PREDICTIONS FOR THE TOURNAMENT

As always Uruguay will be an outsider favourite for the trophy, with the likes of Argentina and Brazil more fancied for the tournament. Uruguay have a good squad who are familiar with a consistent way of playing, and have vast experience which is always useful in major tournaments. Their compact defensive tactics, combined with their attitude, tenacity and aggression as a side, make them one of my favourite international teams to watch, and usually make them one of the least favourite international sides for teams to play. Their weaknesses obviously lie in possession, and their lack of ball progressors means they rely on their defensive work heavily, and with the strike partnership ageing, I suspect they will rely heavily on pace and support being supplied by the wingers if Uruguay are to have success. They manage games expertly, are tactically robust, and will be as motivated as ever, with this maybe the last Copa America for the recent golden generation of Uruguay’s National Team, and so a spot in the semi-final or beyond should probably be the target for Uruguay. In a one-off game, they can beat anybody and so it will no doubt be interesting to see how teams cope with them if they reach the latter stages.

Comments