Counter-attacks in football are thrilling moments of high-speed action that can turn the tide of a game in an instant.

They are tactical sequences that require a delicate balance of speed, precision, and teamwork.

In this tactical analysis, we will delve into the art of the counter-attack, exploring the key elements that make it successful, the strategies used by teams to execute them, and the role of players in turning defensive situations into potent offensive opportunities.

Counter-attacks are not just about pace; they are a fascinating aspect of the beautiful game where strategy, timing, and individual brilliance come together to create some of the most exhilarating moments in football.

Counter-attacks as Threat

To begin, let’s clarify the concept of a counter-attack.

A counter-attack occurs when the defending team rapidly transitions from defence to offence after winning back the ball in their own half.

In broader terms, it’s any offensive move that commences the moment a team regains possession.

Counter-attacks are highly effective for several reasons.

Firstly, they are abundant.

In any match, a team will regain possession numerous times, presenting frequent opportunities to advance the ball swiftly when the opposition is most vulnerable.

Secondly, counter-attacks are relatively uncomplicated to coach.

The fundamental idea is to move the ball forward as quickly as possible, relying more on individual skills and speed than intricate tactical instructions.

The primary coaching decision revolves around the preferred style of ball recovery.

Some managers, like Diego Simeone and José Mourinho, choose to sit deep, draw the opposition in, and exploit space behind the defensive line.

Others, such as Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola, opt for an aggressive high-press approach, closing down the opponents as soon as they gain possession.

Lastly, the nature of counter-attacks often allows for numerical superiority over the defence, leading to high-quality shooting opportunities.

Consequently, a well-executed counter-attack frequently results in a goal-scoring chance.

However, it’s essential to note that counter-attacking football isn’t suitable for every team, and the key to success largely hinges on the individual capabilities of the players involved.

Top Clubs Using Counter-attacks

Counter-attacks have been and always will be a significant aspect of football, regardless of prevailing tactical trends.

Recent shifts in tactics have led to a surge in counter-attacking strategies.

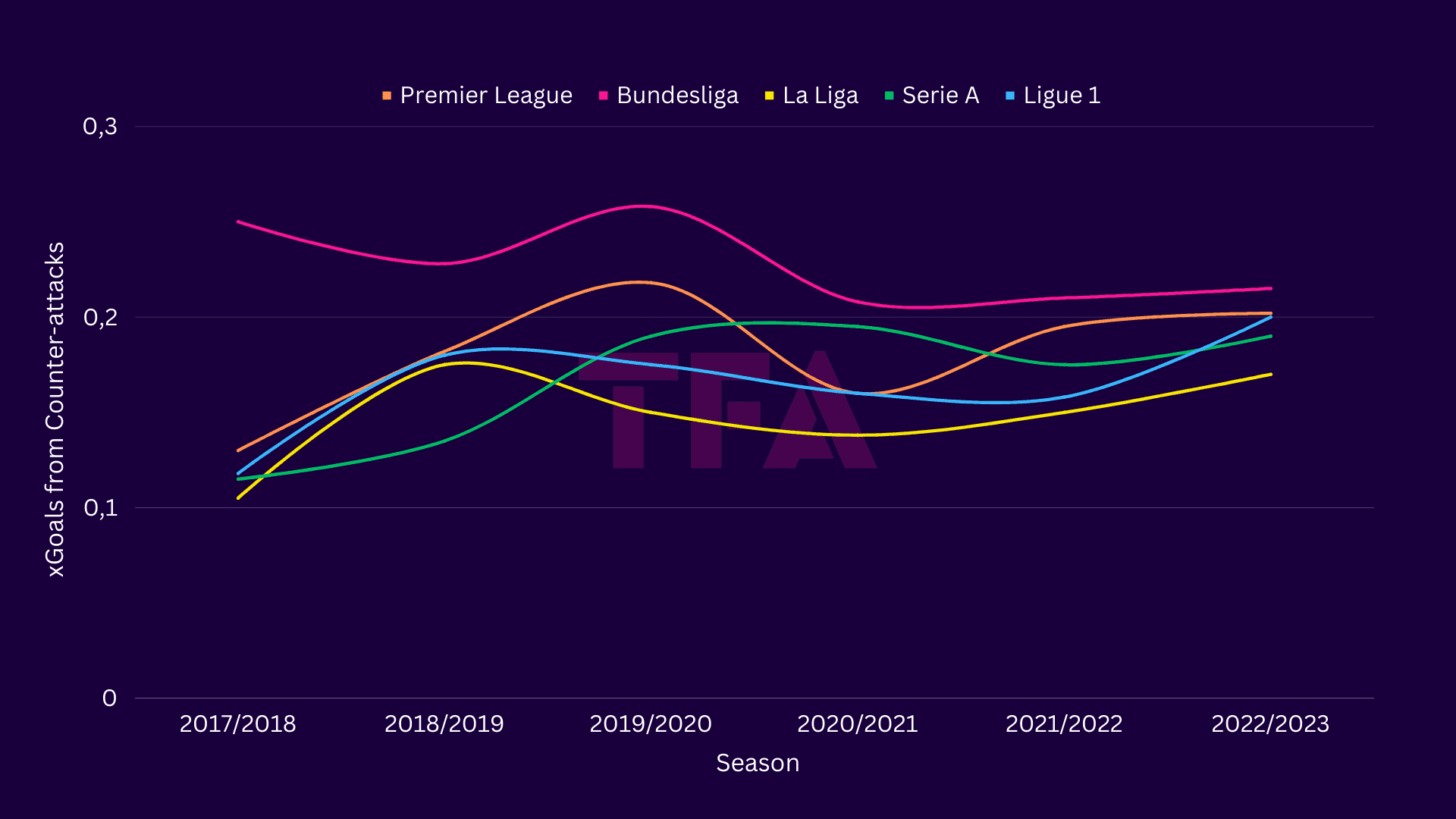

Over the past five seasons in Europe’s top five leagues, there’s a noticeable increase in both expected goals (xG) and the percentage of goals originating from counter-attacks.

Notably, the Premier League has witnessed an ascent from 0.13 xG per 90 to 0.21 xG in just five seasons.

Meanwhile, the Bundesliga stands out as a dominant force in this style of play, with clubs like Bayern Munich, Borussia Mönchengladbach, and FC Köln ranking high in Europe for xG from counter-attacks.

This upswing can be attributed to the influence of the German coaching school, which has produced numerous world-class managers emphasising transitional play.

Mainly, the concept of Gegenpressing, aimed at swiftly regaining possession and capitalising on vulnerable opponents, has gained popularity.

The surge in Gegenpressing and high-pressing football appears to be a primary driver behind the increase in counter-attacks.

Quick ball recovery often places attacking players in advantageous positions.

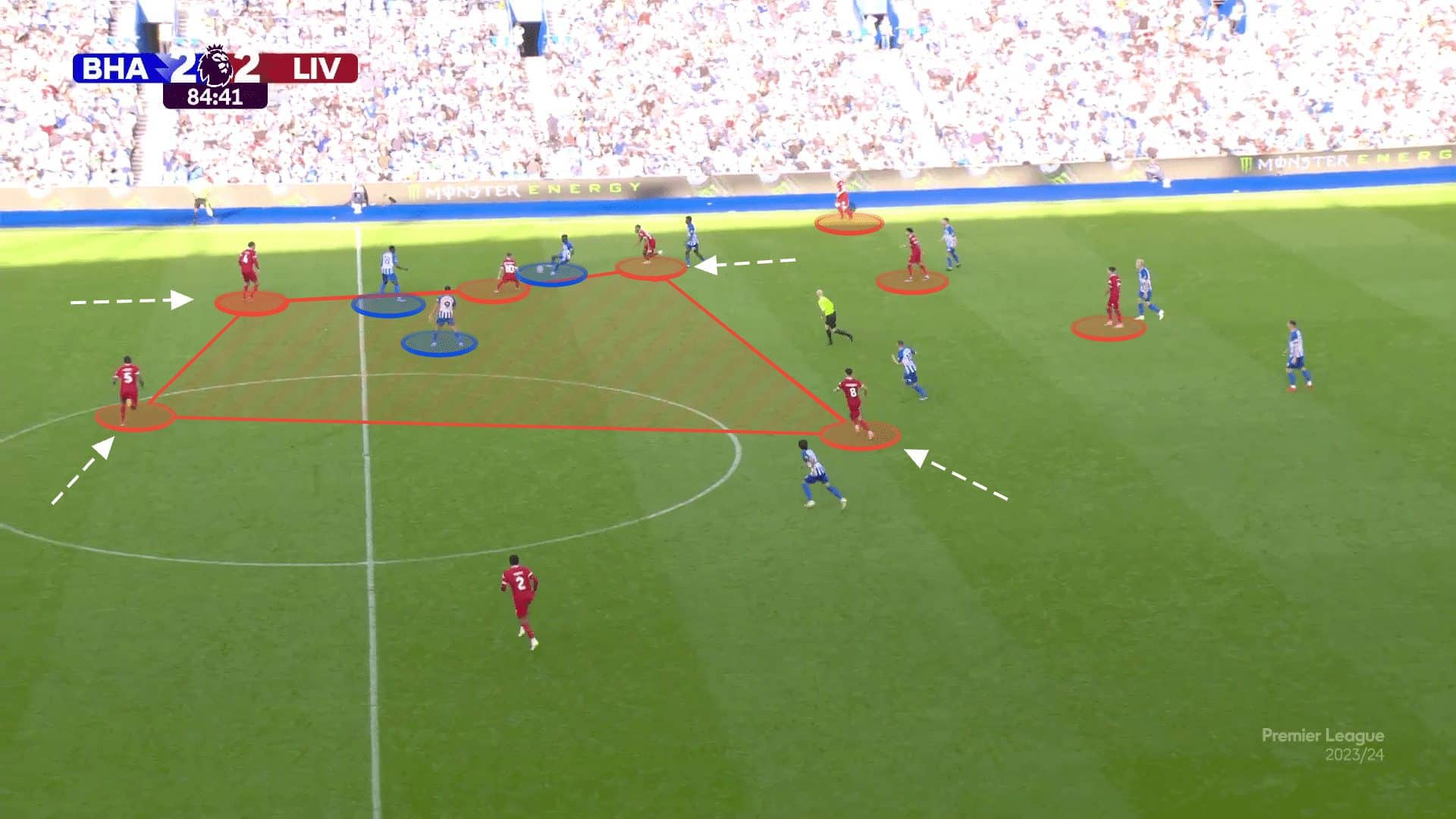

However, it’s worth noting that poorly executed Gegenpressing can leave space behind the ball for opponents to exploit, making Gegenpressing itself susceptible to counter-attacks.

This might explain why Liverpool’s performance has dipped compared to previous seasons.

Statistically, their xG from conceded counter-attacks last season was the worst in recent times.

Their ageing midfield is often caught out of position, exposing the defence, and they’ve struggled to prevent counter-attacks.

For some teams, counter-attacks are a fundamental component of their game plan.

AC Milan stands out as the most prominent example in Europe.

When examining xG per 90 generated from counter-attacks, AC Milan leads the continent, with Bayern Munich, Leipzig, and Villarreal also ranking among the most dangerous teams in Europe.

Reaching UCL semifinals with Counters

To understand why teams like AC Milan excel in counter-attacks, let’s delve into how they create these opportunities.

Last season, AC Milan operated with a 4-2-3-1 formation, and it’s essential to grasp why their counters work effectively by examining the key players at Pioli’s disposal, including wingers Brahim Diaz and Rafael Leao, as well as the target man, Olivier Giroud.

However, it’s crucial to recognise that the entire team plays a vital role in crafting these chances.

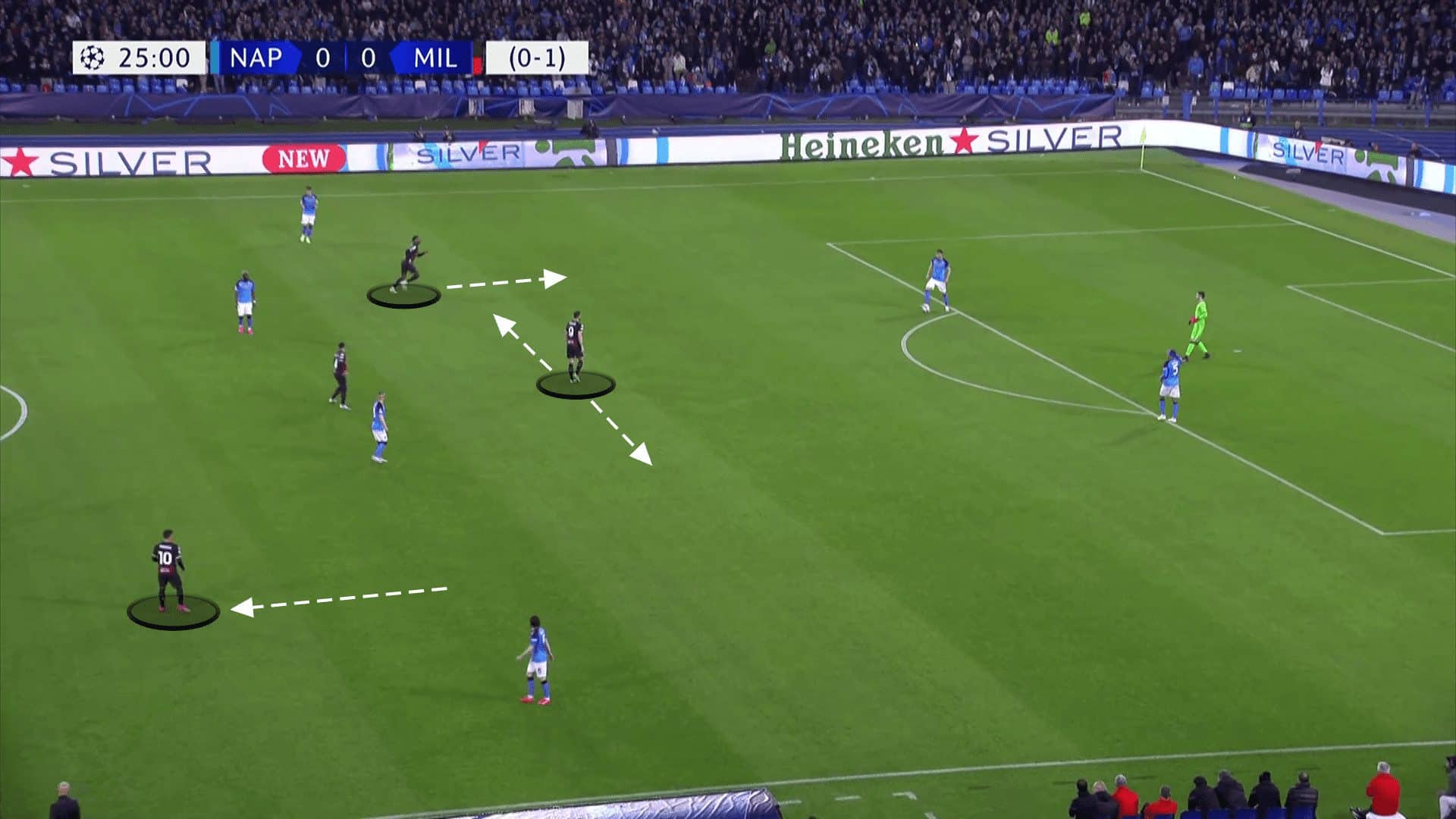

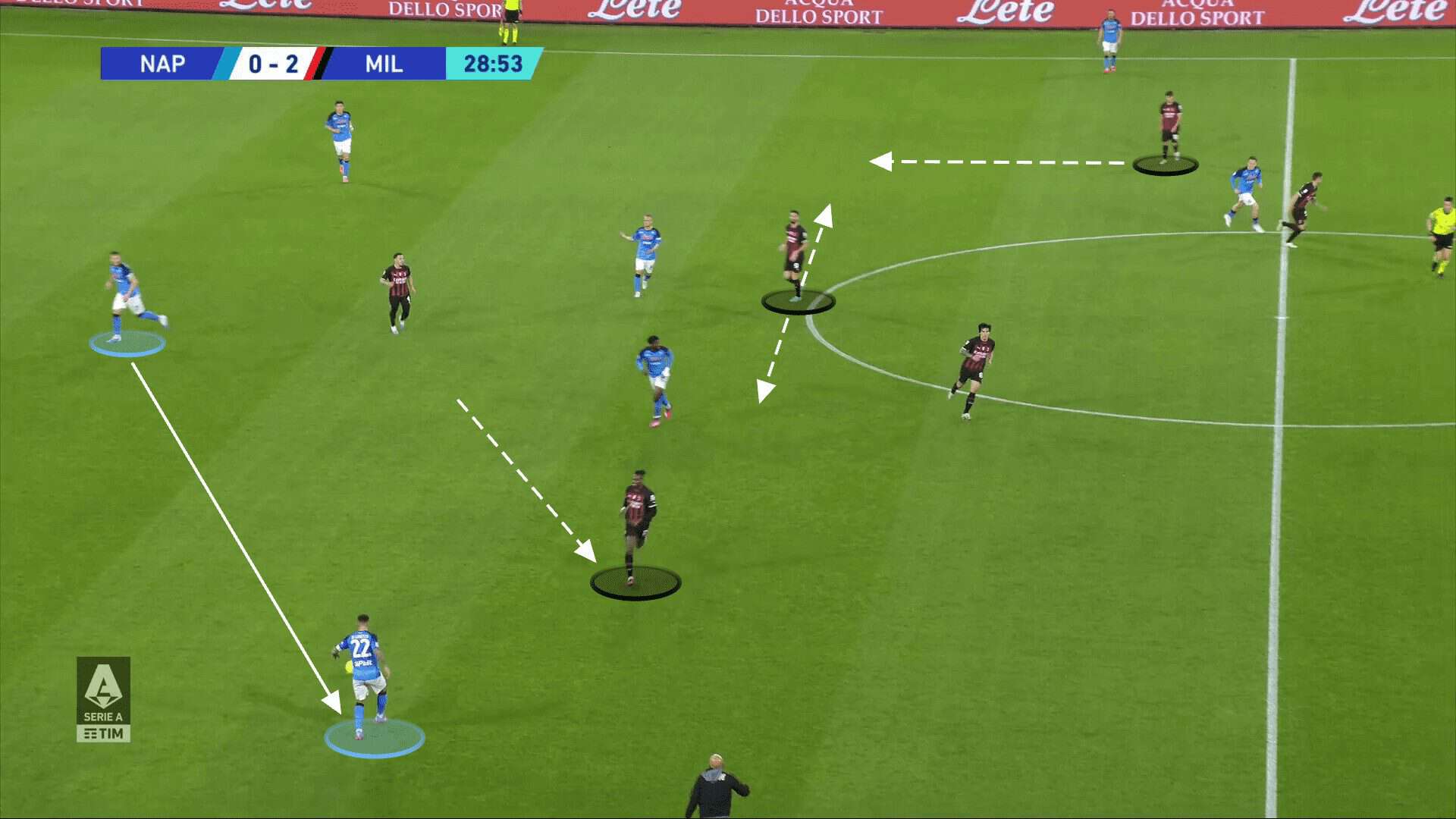

In the initial phase, AC Milan doesn’t engage in high pressing as the opposition begins their attack.

Giroud strategically cuts off central passing lanes, moving between the centre-backs, while the wingers adjust their positions to restrict direct passes to the fullbacks, often channelling play centrally.

Simultaneously, the three midfielders employ an aggressive man-to-man pressing structure, occasionally catching opponents off guard and swiftly regaining possession, placing Leao and Diaz in dangerous positions.

As the opposition advances, the formation transitions into a 4-1-4-1 shape.

Depending on the flank the ball is on, the wingers adopt a staggered formation.

If the opposition progresses down the left flank, Brahim Diaz drops deeper to monitor potential overloads, while Leao maintains a higher position up the pitch.

If they win back the ball, Leao is strategically positioned to initiate a quick attack.

When the centre-back rotates the ball, Leao shifts to cover the fullback, and Diaz advances, ensuring Milan constantly maintains two outlet options in the final third.

AC Milan crowds the box with up to eight players, organised in two banks of four, with Leao and Giroud consistently staying above the line of the ball.

The tenacious and aggressive play of the three midfielders and centre-backs often enables AC Milan to regain possession in this area.

Upon winning the ball, they can promptly seek a long pass forward.

Although Giroud may not be the fastest player, his exceptional hold-up play allows him to retain possession and distribute the ball out wide to the wingers, enabling Milan to advance quickly.

While these elements are vital, they are not the sole method for a team to be effective in counter-attacks.

Milan employs a more passive approach to regain possession, capitalising on Giroud’s ability to receive long passes from deep to initiate their counter-attacks.

Similarly, Real Madrid has adopted a similar blueprint, with Karim Benzema’s excellent hold-up play and pace on the wings provided by players like Vinicius Junior, Valverde, and Rodrygo.

The Reliance on Individual Quality

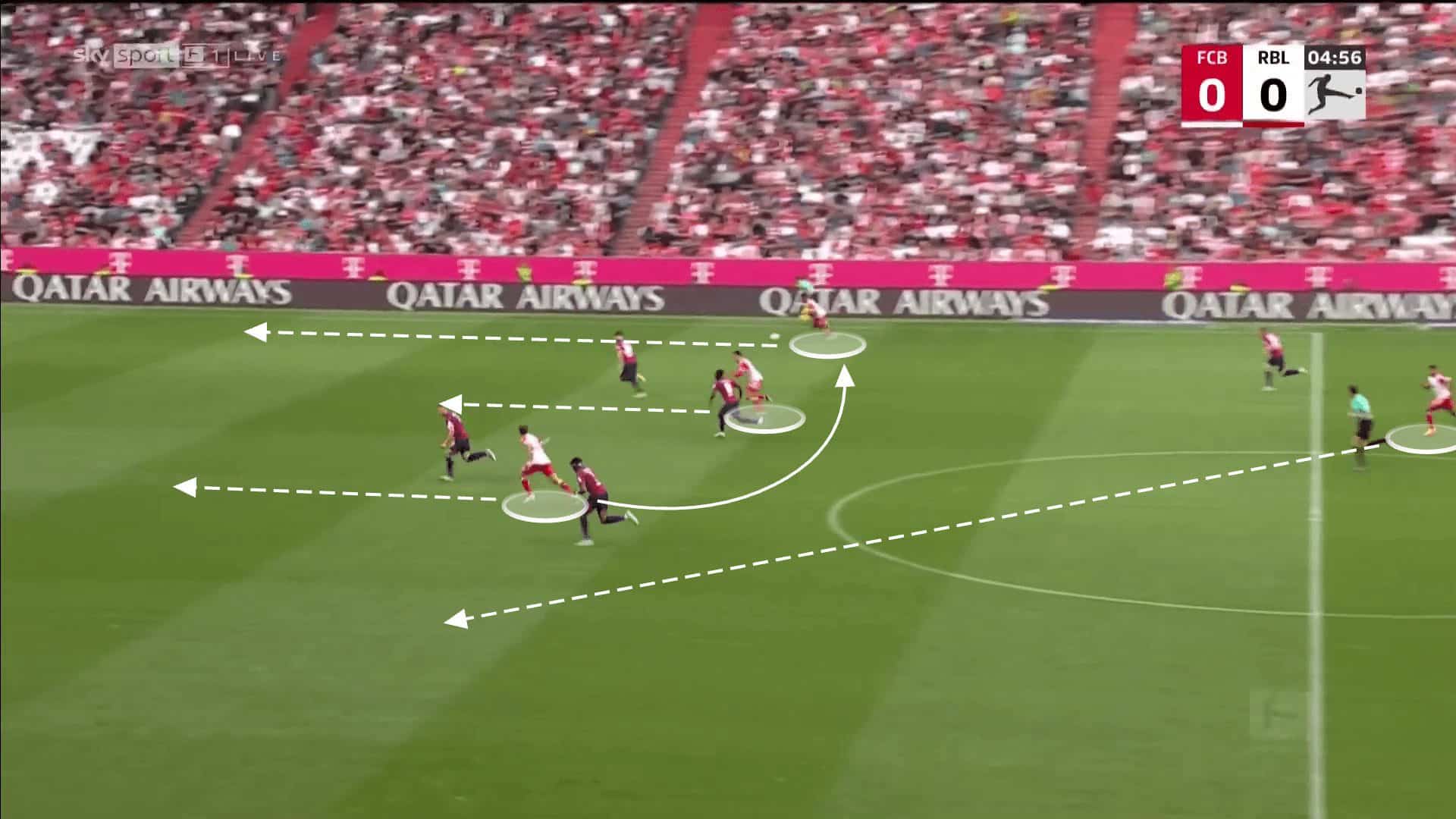

Nonetheless, teams such as last season’s Bayern Munich exhibited a different approach in their counter-attacking tactics.

They positioned their striker, Thomas Müller, to actively facilitate link-up play with the attacking midfielder, Jamal Musiala, before swiftly transitioning the ball to their lightning-quick wingers, Kingsley Coman and Serge Gnabry, operating out wide.

The critical point here is that the absence of even one essential component can render a team impotent in their counter-attacks.

A case in point was AC Milan in their semi-final encounter against Inter when Leao’s absence due to injury significantly impacted their ability to execute effective counters.

A more striking example can be found in Chelsea’s performance last season.

Despite boasting exceptionally rapid and skilful wingers and a physically robust midfield capable of regaining possession, their deficiency in a target man or central support meant that potential counter-attacks were quickly nullified.

This was because the opposing team could effortlessly regain possession in these areas, and players like Kai Havertz or Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, although talented, lacked the necessary combination of pace and physical strength.

Consequently, Chelsea’s pacey wingers often found themselves in ineffective positions to capitalise on their speed.

How to Stop Counters

Preventing and halting counter-attacks is just as crucial as orchestrating them, and it’s a facet of the game often overlooked by the cameras.

While the spotlight is typically on the attacking side when a team is on the offensive, a silent but vital defensive battle rages on at the back.

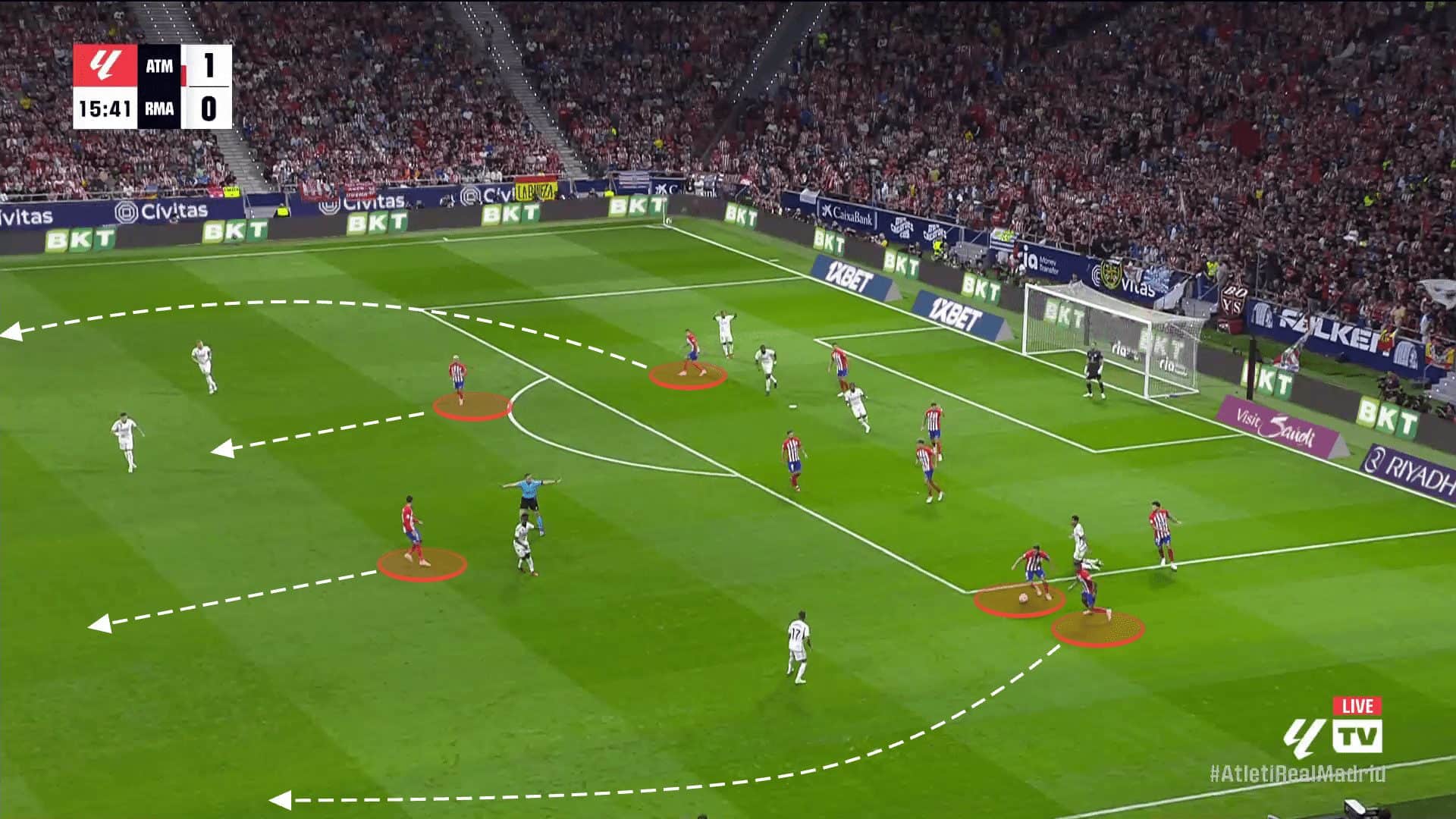

Specific positions are crucial in effectively thwarting counter-attacks, and this phase is referred to as preventative marking.

Any player not actively involved in the offensive push must be prepared to intervene if the opposing strikers launch a counter.

As attackers seek to position themselves strategically to exploit gaps, defenders must adapt their positioning to prevent the ball from reaching the forwards in the first place.

The most prevalent method employed is maintaining a plus-one advantage.

For instance, if the attacking team deploys two players up front, the defending team usually places three players at the back, with an additional player in the midfield.

This extra midfielder aims to cover any balls played forward, ensuring that even if the striker bypasses a defender, there is always another player ready to close them down.

Depending on the unique skills of each defender, the holding midfielder might cover the striker.

In contrast, the defender guards the space behind, or the centre-back could challenge in the air and initiate an offensive play.

If the opposition commences their counter, the defence’s primary objective is to block off the centre of the pitch and coerce the play out wide.

When scrutinising counter-attacks, it’s noteworthy that over 70% of these goals are scored when the ball remains within the central region.

Thus, impeding central passing routes and channelling play toward the flanks furnishes the defensive team with ample time to regroup and counteract any impending threats.

Conclusion

In conclusion, counter-attacks remain a potent and exhilarating aspect of modern football.

The art of transitioning from defence to offence in the blink of an eye represents a compelling spectacle capable of changing the course of a game with lightning speed.

Understanding the intricacies of counter-attacks is indispensable for teams aiming to excel on both ends of the pitch.

While the attackers seek to exploit gaps and capitalise on the opposition’s vulnerability, defenders must be poised to quell these rapid-fire attempts.

Preventative marking, ensuring a plus-one advantage, and steering play wide to stymie central threats are vital in denying the enemy’s counter-attacking prowess.

These lightning-quick moves are not solely a product of individual brilliance; they require intricate teamwork and tactical acumen.

Coaches, managers, and players who appreciate the complexities of counter-attacks can use them significantly, turning moments of defensive solidity into lightning-fast opportunities to score.

In a footballing landscape where the speed of thought and execution is paramount, counter-attacks embody the essence of rapid, breathtaking play.

Mastering the art of creating and preventing counter-attacks has become more crucial than ever in the modern game, and it will continue to be a defining factor in a team’s success on the pitch.

Comments