Saint-Étienne defeated Rennes 2-1 to seal a place in the final of Coupe de France, that being their first one in the competition since 1982. It was a highly surprising result considering the poor run of form that Claude Puel’s side are currently in and especially since Julien Stéphan has a good record against Saint-Étienne and his side is in impressive form lately. Nevertheless, it was a historic win for William Saliba and co. as they showed passion and determination to seal an outstanding comeback win.

In this tactical analysis, we’re going to take a closer look at both team’s tactics to see what’s happening in the game in more depth and detail.

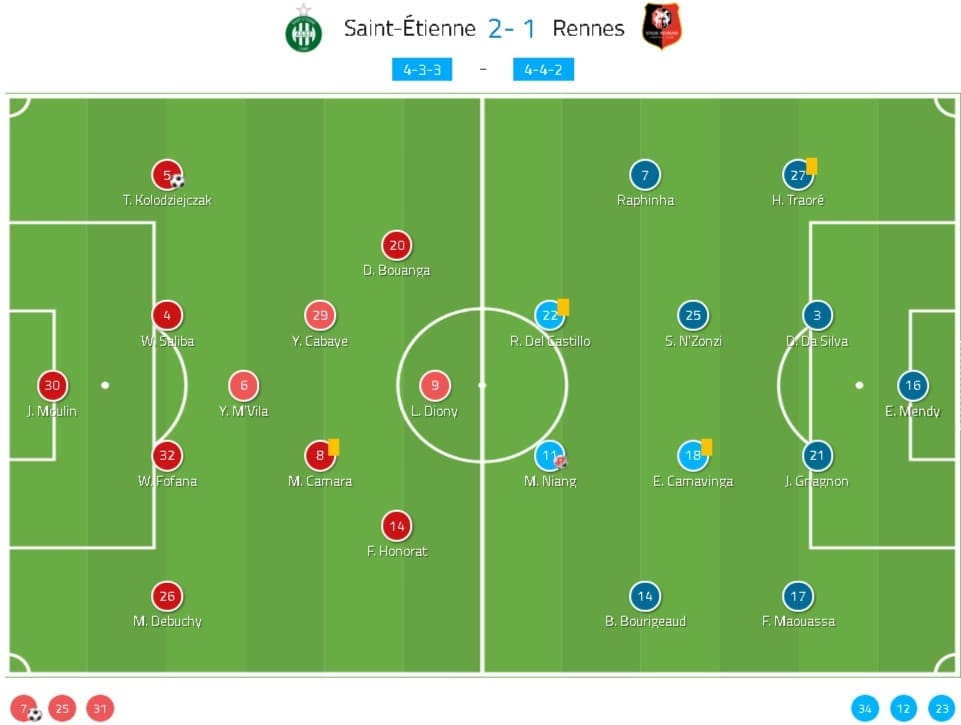

Lineups

Puel deployed his team in a 4-3-3 formation in this game which is not something we could see often this season. The former Southampton and Leicester City manager has been trying out a few different formations this season but 4-2-3-1 has been the most commonly-used system. Only one change in personnel can be seen in the lineup with Mahdi Camara coming in to replace Miguel Trauco.

Stéphan, meanwhile, opted to use his favoured 4-4-2 shape with the double pivot of Eduardo Camavinga and Steven N’Zonzi in the middle. The lineup for this game was exactly the same as in their last match against Toulouse. No changes at all.

Saint-Étienne’s positional rotations and combinations difficult to stop

Saint-Étienne’s mission was clear in this game – score a goal as quickly as possible right from the start. They tended to play from the back and preferred to use short or medium passes but they’re actually rather direct and would break forward with pace whenever they managed to exit Rennes’ high pressure.

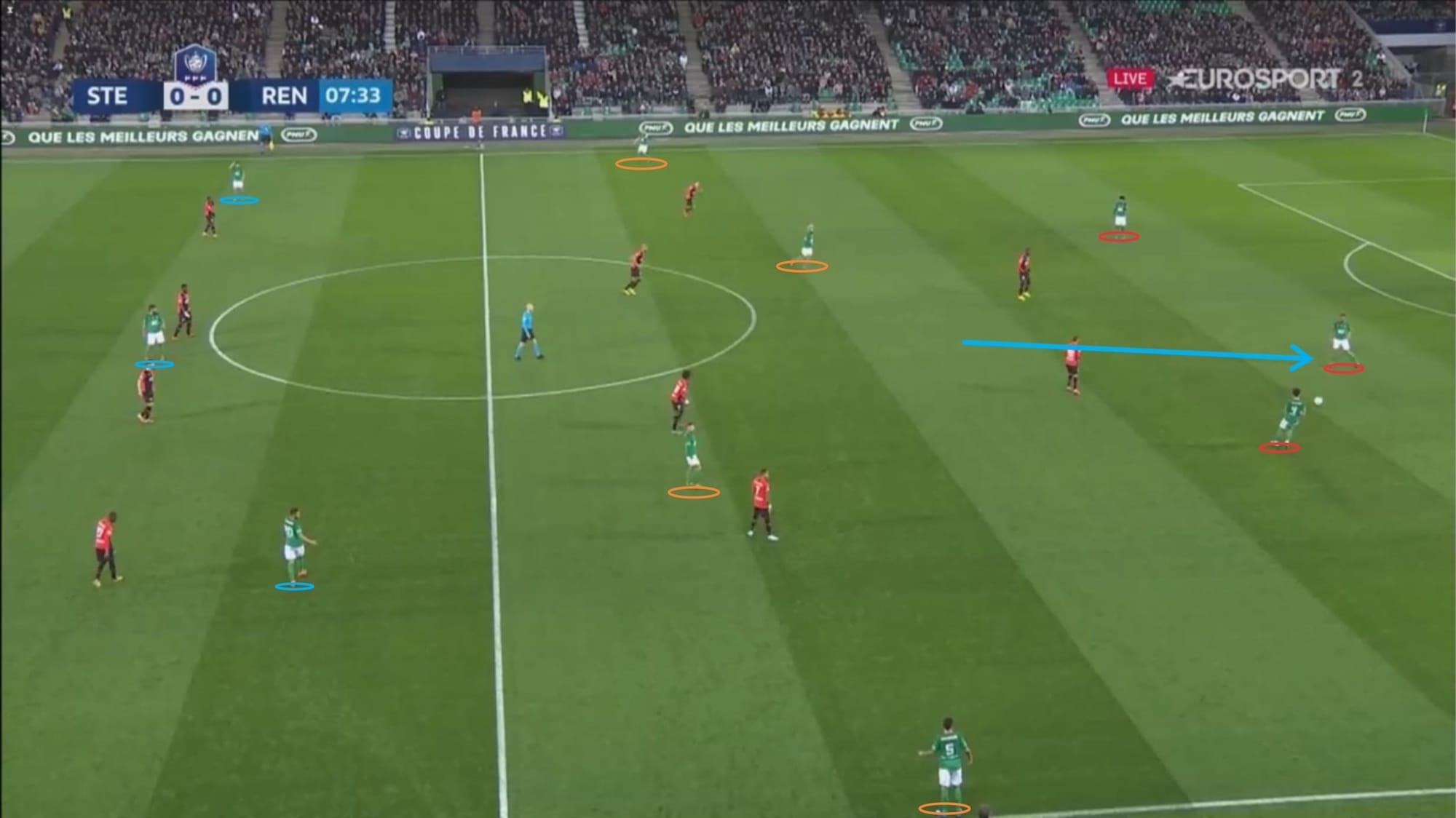

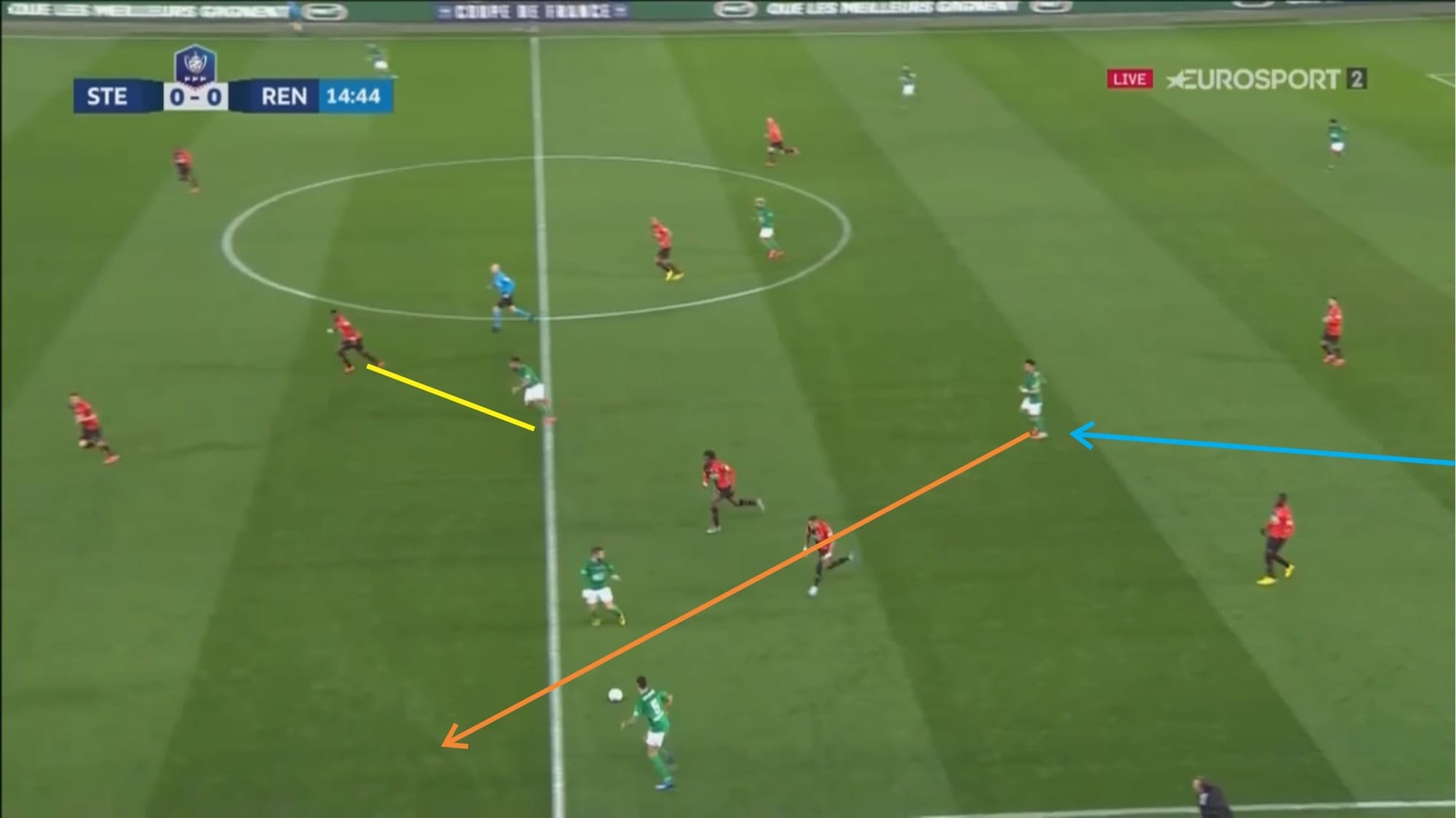

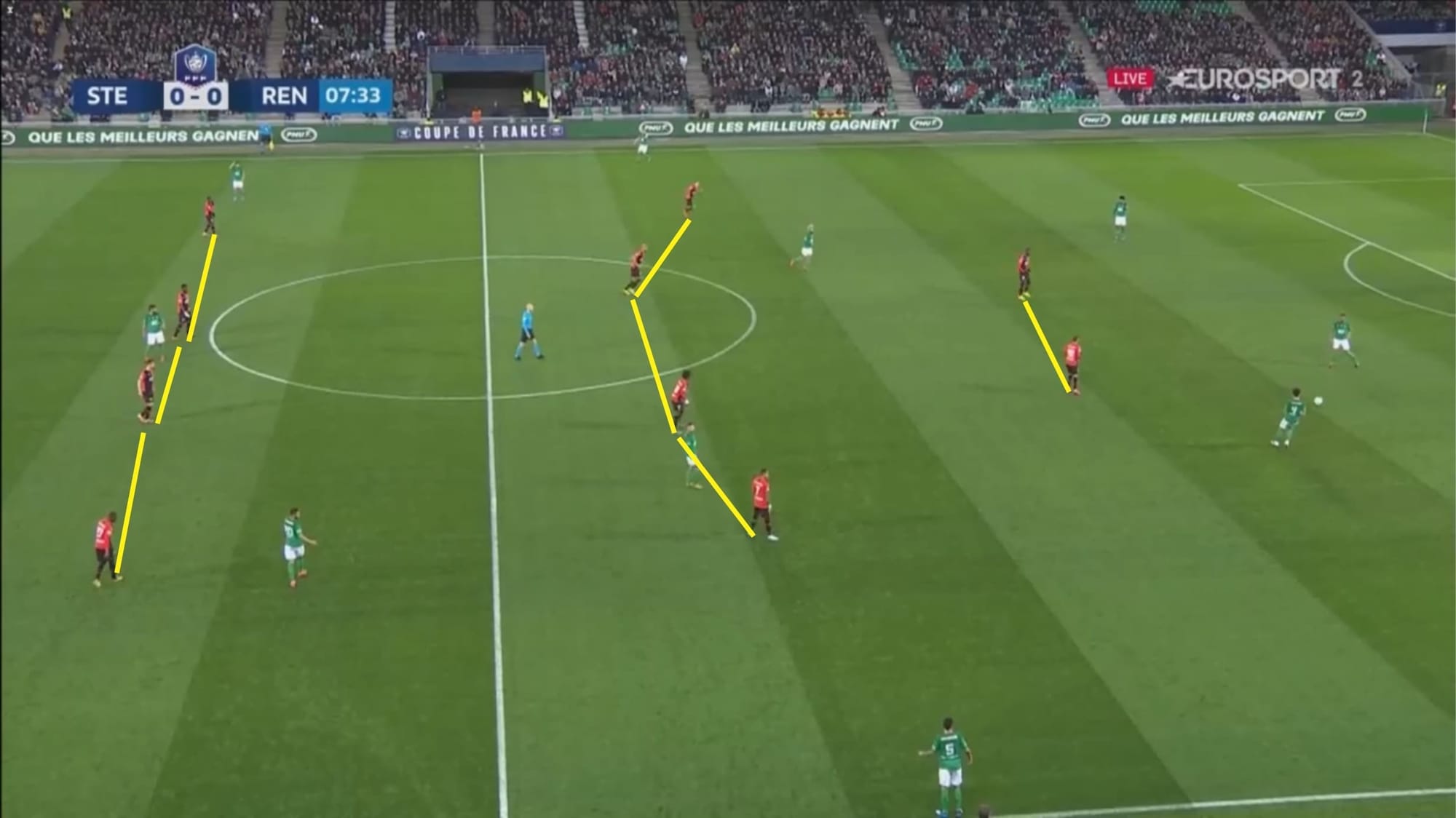

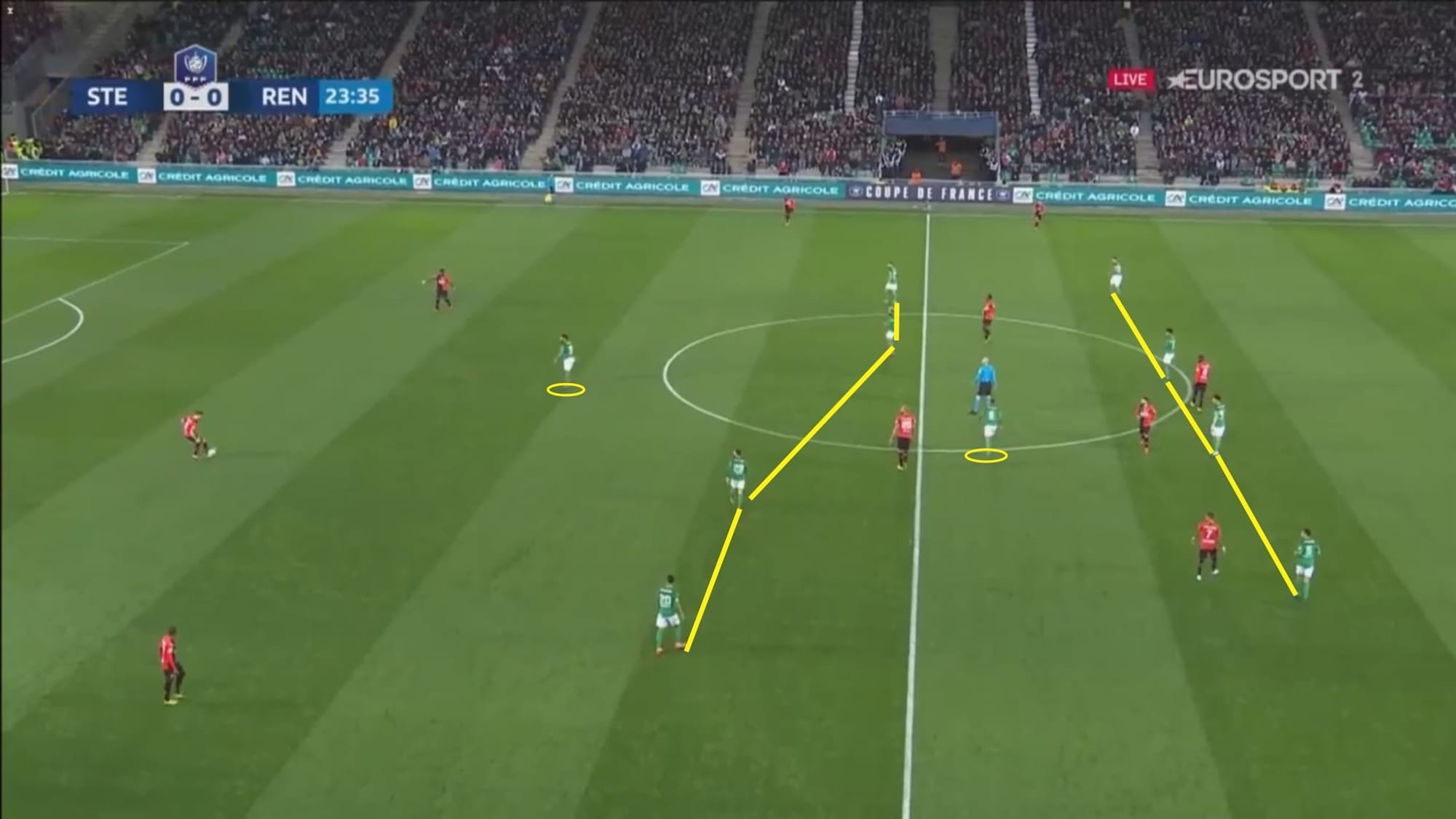

Saint-Étienne would create a three-man backline in the build-up with Yann M’Vila usually dropping to sit in between or beside the two centre-backs. This allowed them to move the ball around at the back with more ease as in the example above, the three at the back outnumbered Rennes’ front two.

The two full-backs also sat high and wide, trying to stretch Rennes’ narrow defence and occupying free space out wide. The two Saint-Étienne eights usually would sit in the half-space and occupy both the central midfielder and the wide midfielder of Rennes, allowing further freedom for the advancing full-back. Usually, if wide options were unavailable and the three at the back struggled to find near options to progress, one of the two eights would drop to offer support as well as create space by dragging his marker out. When the ball was moved wide, the ball-near eight would get closer and sit in the half-space, usually creating a triangular shape with the winger and full-back.

However, even when under pressure, Saint-Étienne usually still preferred to use short-medium passes to get out rather than opting for long balls. This is why they may seem a bit patient at the back as they’ll try to move the ball around while looking for gaps to exploit.

As you can see in the picture above, the structure in the build-up changed into a 3-4-3 formation. Once they worked their way up into advanced areas, the structure looked more like a 2-3-5 with the two full-backs occupying even higher areas, the two eights sitting in the half-space at the edge of the box and the six holding his position in the middle third.

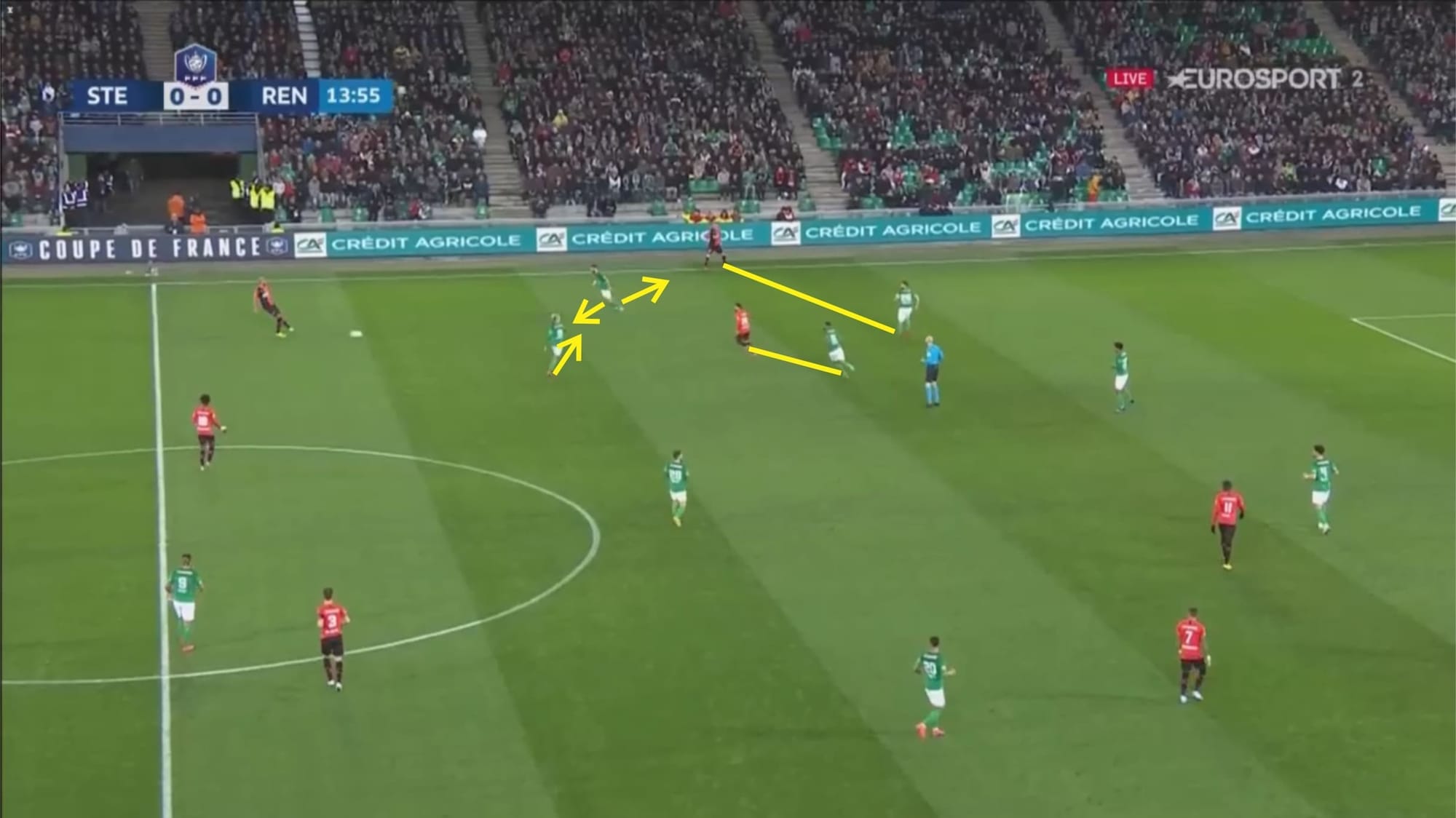

Early in the game, Rennes had this tendency to commit another player forward to mark and eventually press the right/left-sided centre-back if the ball was played towards either of them. However, by committing another player forward, this opened up the passing lane towards the full-back who sat high as you can see in the picture above.

If the Rennes right-back stepped out to press the Saint-Étienne left-back, there would be a lot of space left behind his area of defence which could have been exploited by both the opposing left-winger as well as the left-sided eight.

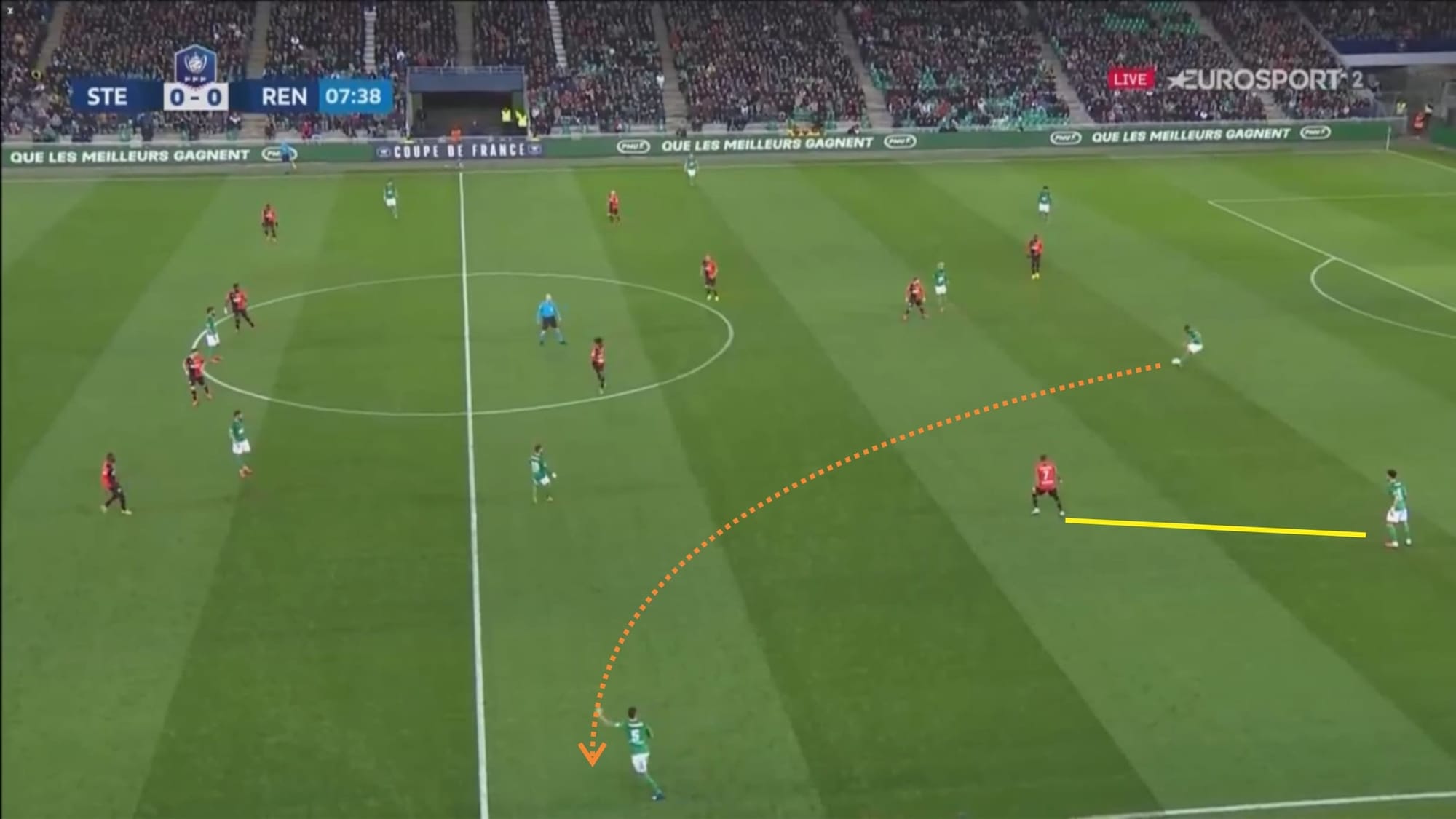

Rennes were man-oriented in pressing and usually would try to steer the ball into the flank where they would then mark the near options to isolate the ball-carrier. Saliba was pretty much isolated in this situation with no viable options near him.

Passing the ball back to the goalkeeper to restart would also be highly risky. His options, of course, would be to either launch the ball forward or drive forward with it. The Arsenal loanee chose the second option in this case.

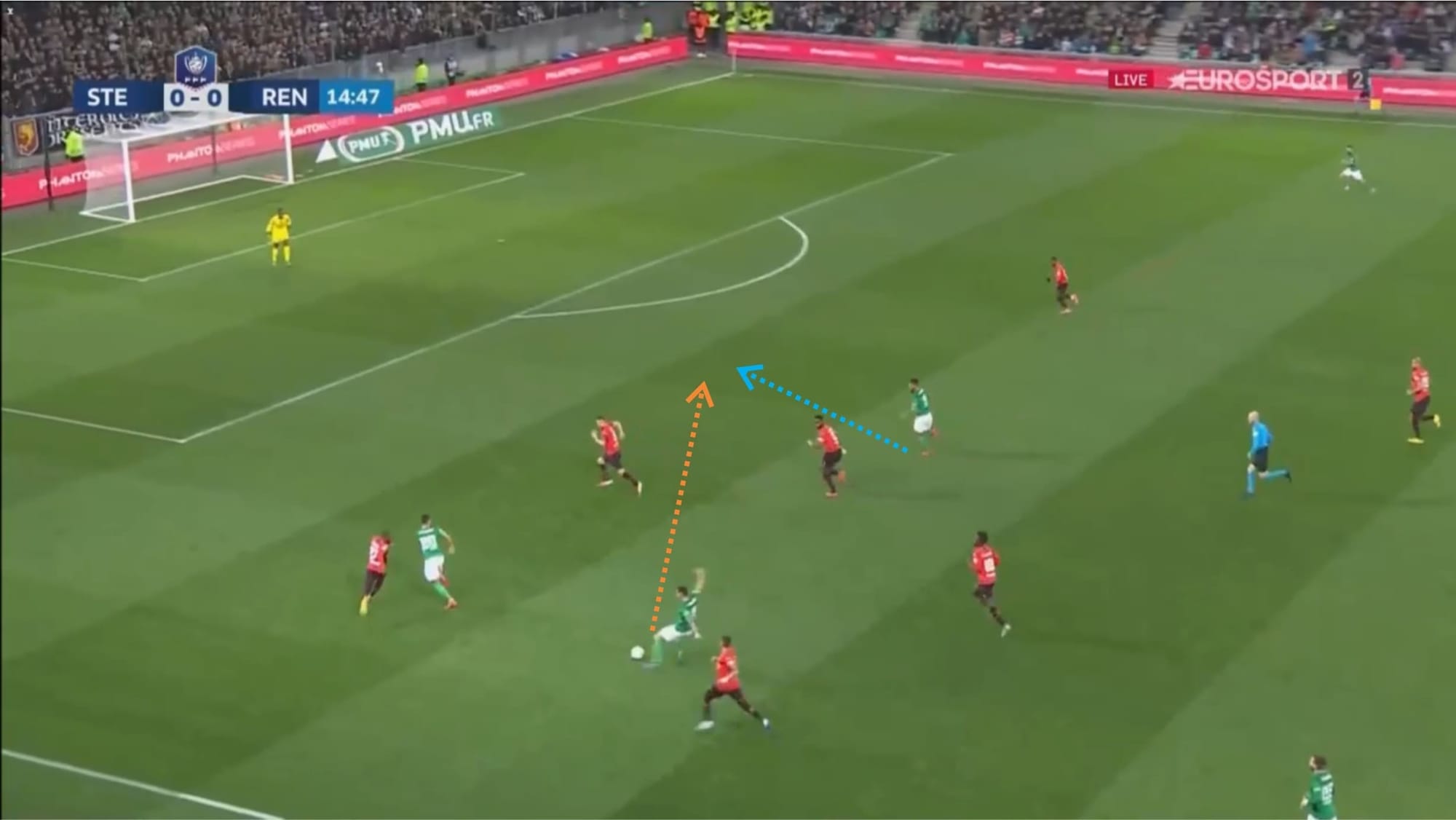

Saliba brought the ball forward and played the ball wide onto the path of Timothée Kolodziejczak on the left flank. You can also see in the picture above that Loïs Diony dropped to offer option while dragging out Rennes’ left-sided centre-back (Joris Gnagnon) in the process.

The Saint-Étienne striker would be doing this movement often throughout the game: dropping to receive and drag the marker out and then accelerating to exploit space if the ball was passed to another player.

Kolodziejczak carried the ball forward and spotted Diony’s run. The left-back then delivered a through pass onto his path and Diony found himself in a 1v1 situation with the goalkeeper albeit receiving some pressure from the Rennes defenders. The striker ultimately failed to finish the chance.

It was quite a straightforward and quick attack although Saint-Étienne had to be a bit patient at first at the back to find gaps to exploit.

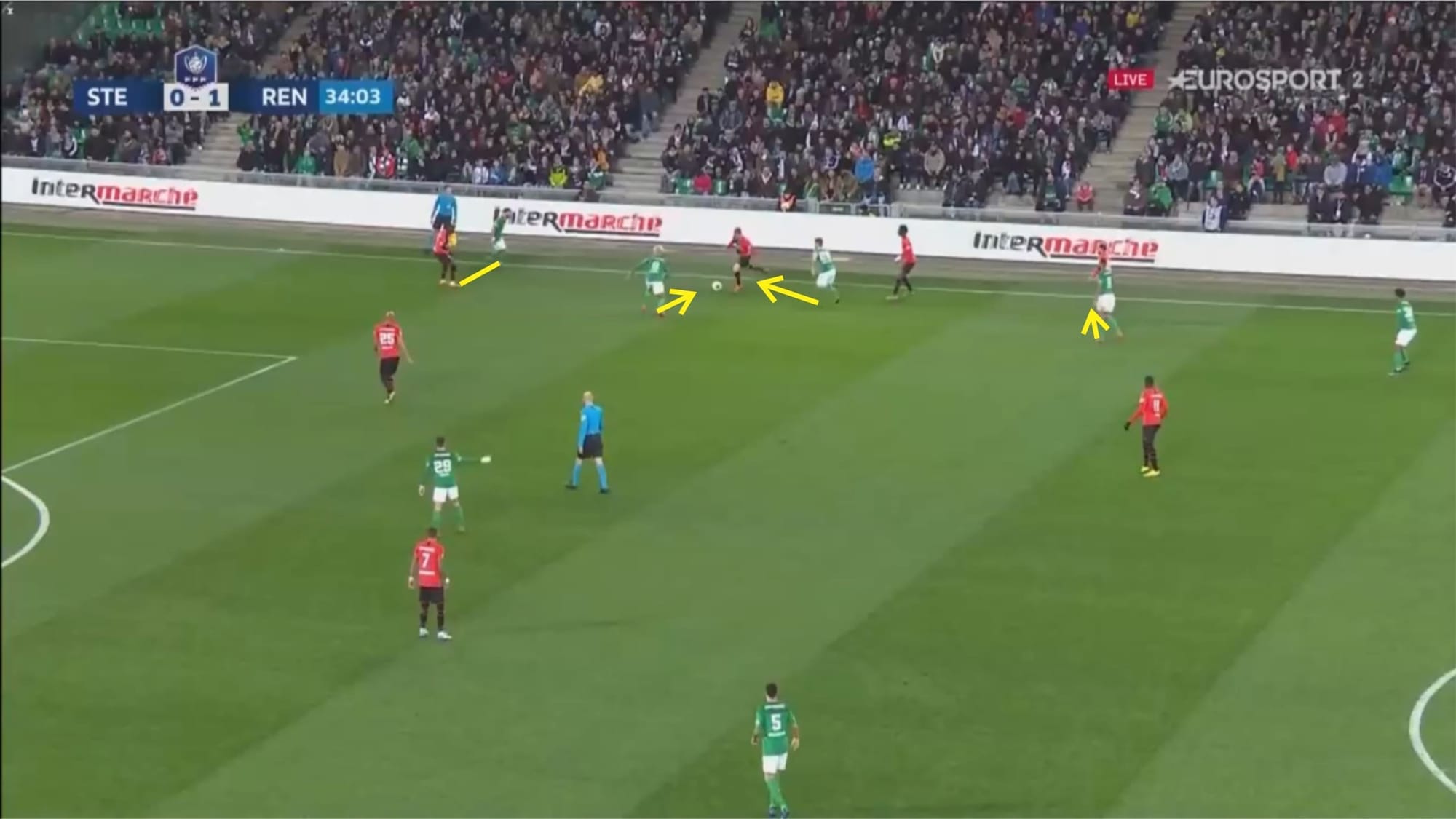

Saint-Étienne’s active positional rotations in the middle and final third as well as their use of third-man mechanisms were quite troublesome for Rennes.

The picture above is one example of Saint-Étienne’s use of positional rotations and use of third-man runs. Franck Honorat saw Camara making an outward run from the half-space. The right-winger then decided to dribble inside, skipping past the challenges of two Rennes players. Notice also Yohan Cabaye moving narrower to add a number in that area. Cabaye would then make a run into the box.

Honorat then passed the ball towards Diony who in turn continued the ball onto the path of Cabaye who made the run into the box. The former Lille central midfielder then took a shot at goal which was not successfully saved by Édouard Mendy but Damien Da Silva managed to clear the ball out before it got past the goal line.

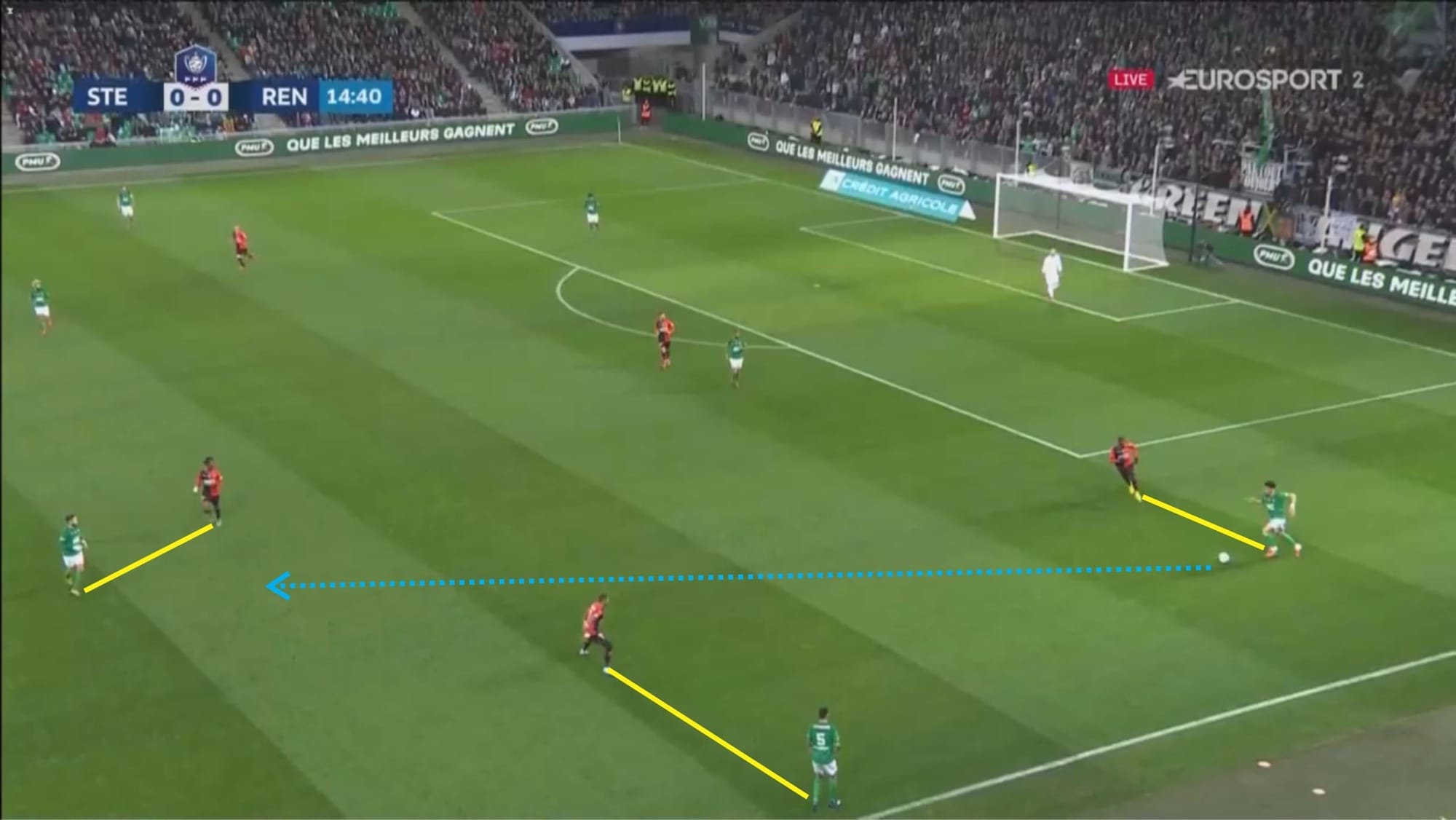

Rennes defended in a 4-4-2 shape with a medium-high block, as you can see in the picture above. As you can see, the defensive block was quite narrow but a bit lacking compactness. Though if the ball was played inside the box Rennes would quickly compress space – this tendency to get attracted to press Saint-Étienne’s backline (and create a gap between the lines) occasionally resulted in Saint-Étienne being able to exploit the space between the lines.

Rennes’ main aim was to prevent central progression and aimed to force the opposition to move the ball to the flanks where they could then execute their pressing trap and create an overload to isolate and win the ball back. Their approach in pressing was man-oriented while their marking was a bit more situational – meaning that a player was usually both option-oriented and covering space.

Rennes’ directness caused troubles

Just like Saint-Étienne, Rennes also aimed to be direct and straightforward when on the ball. Stéphan’s team are certainly known for their ability to break quickly and they did cause a lot of trouble for the opposing team with their pace on the break in this game. Rennes did create a few dangerous chances in the game through their quick breaks.

Rennes tended to play from the back but unlike Saint-Étienne, who were a bit more patient at the back, Rennes were much quicker in moving the ball forward. If under pressure, sometimes long balls forward into space behind the defence or in front of the defence would be an option.

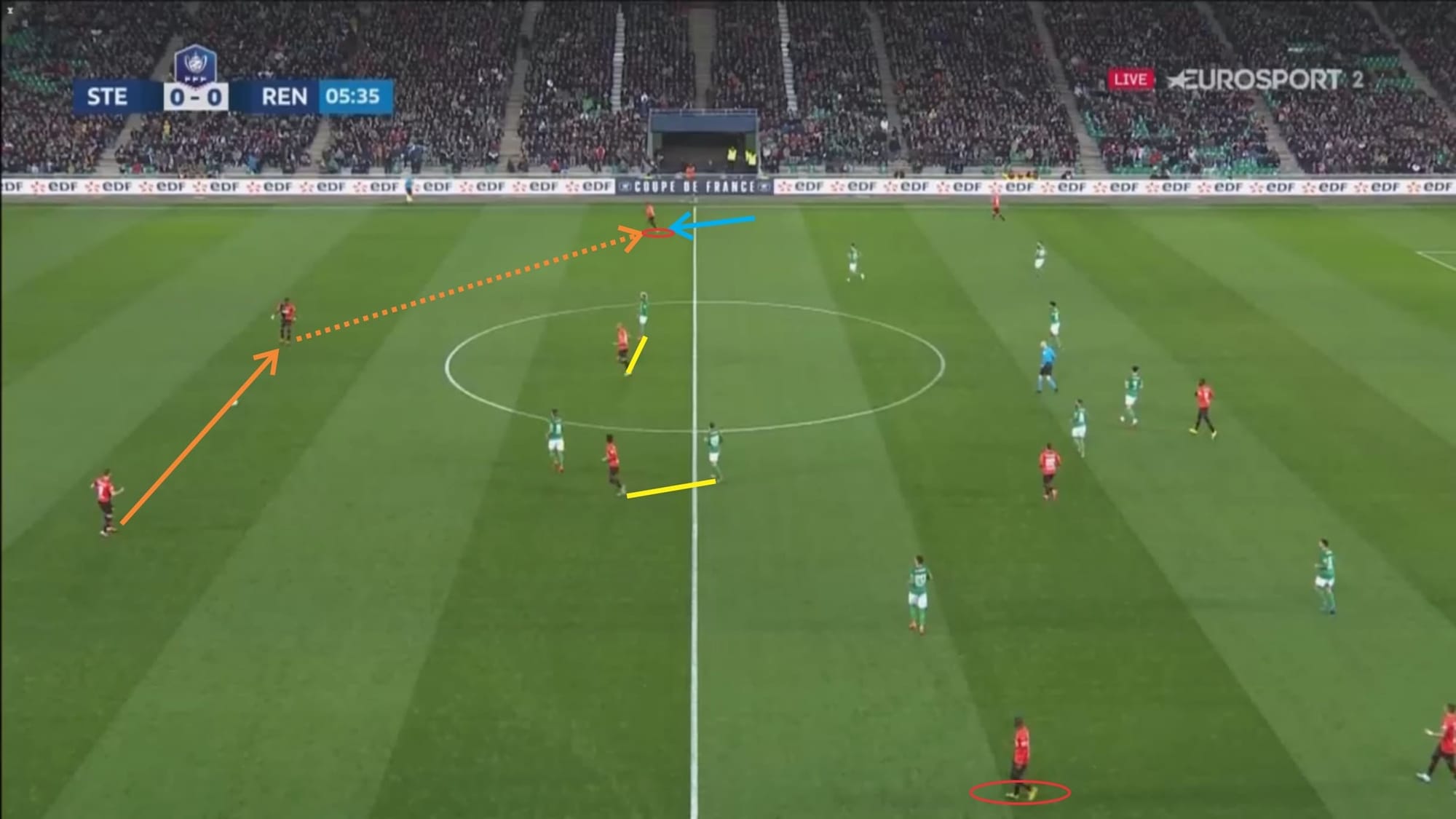

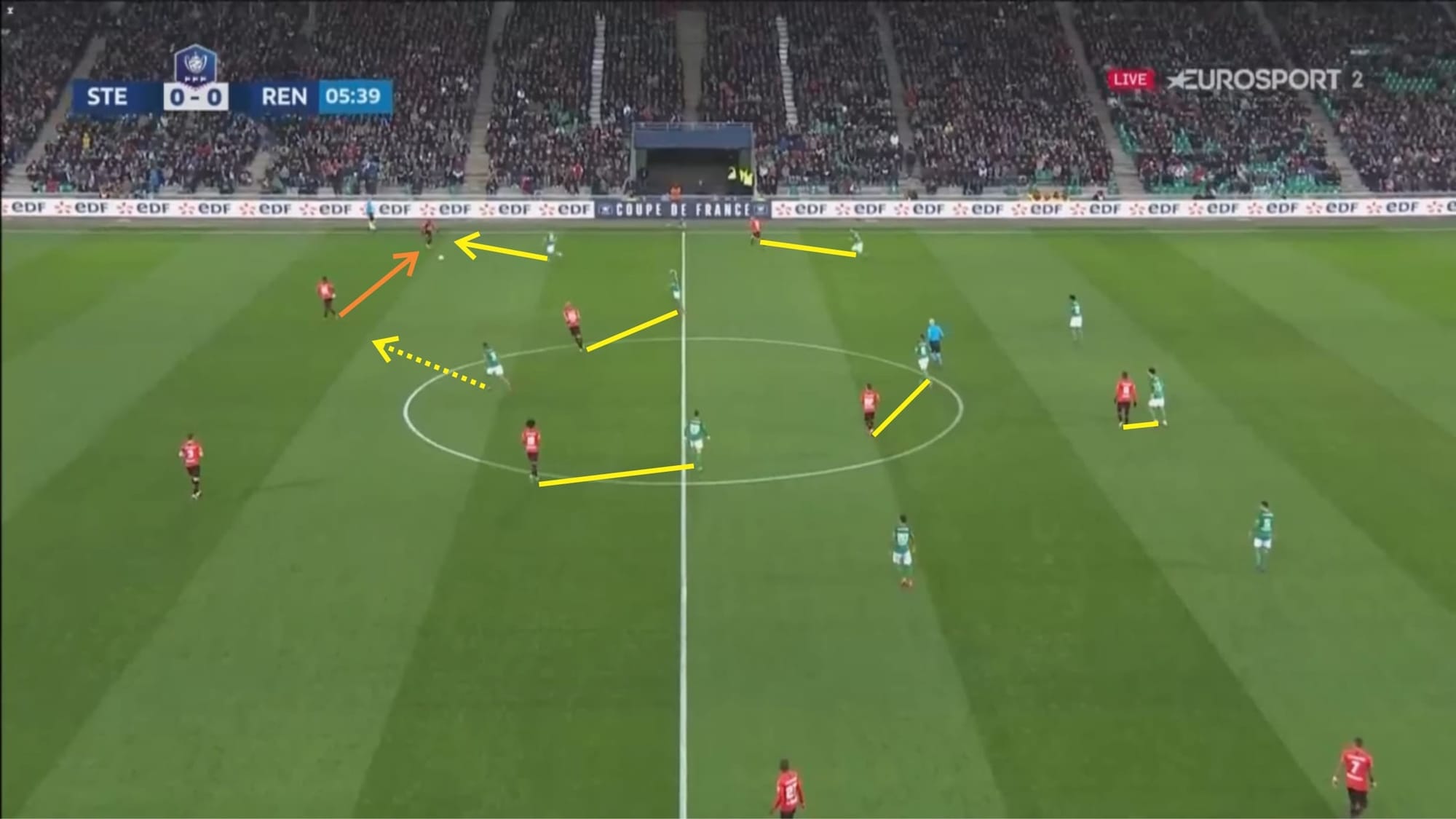

As you can see from the picture above, the two Rennes full-backs tended to be asymmetrical. While one would stay higher, the other one would drop to offer support. As you can see, progression through the middle were also rather difficult, especially with the two Saint-Étienne eights marking Rennes’ two pivots and Saint-Étienne’s six tightly marking Rennes’ free-roaming forward Romain Del Castillo who’d usually actively move between the second and third lines to try to find pockets of space to exploit.

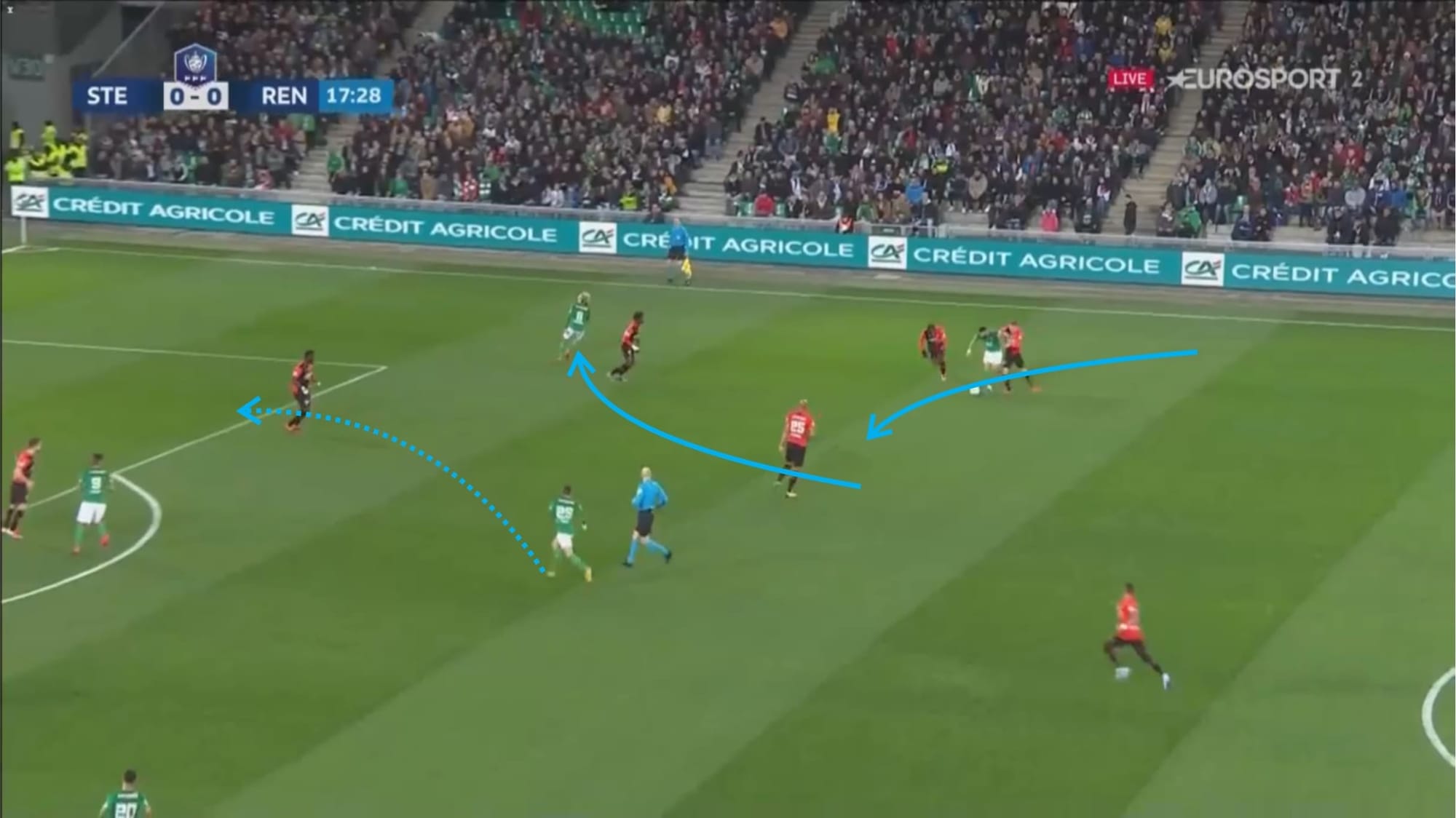

As mentioned previously in this tactical analysis, Rennes’ strength in attack is their ability to break forward very quickly after winning the ball. Stéphan’s side were very disciplined in every phase of the game. As you can see, once they managed to win the ball, everybody quickly made a run forward. In this situation, Raphinha managed to recover the ball and then spotted a run from Del Castillo.

Notice that there are already three Rennes players going against only two Saint-Étienne players. Rennes tended to break through the flanks on the counter with either of the two forwards moving wide to stretch the defence and receive the ball on the flank while one (who would be the target inside the box) would make a run centrally. However, in this particular situation, Raphinha opted to pass the ball centrally instead of wide.

Saint-Étienne was certainly aware of Rennes’ danger on the break and they reacted accordingly. After losing the ball, the team would quickly counter-press to delay Rennes’ counter-attack as well as potentially winning the ball. Saint-Étienne aimed to swarm the ball-carrier, closing down any passing lanes.

The ball-near players also marked the nearest options making it extremely hard for the ball-carrier to get out of the pressure. These counter-pressing tactics were quite effective in limiting Rennes’ threats on the counter although, at times, Rennes could still escape the press and execute their counter-attack albeit much infrequently.

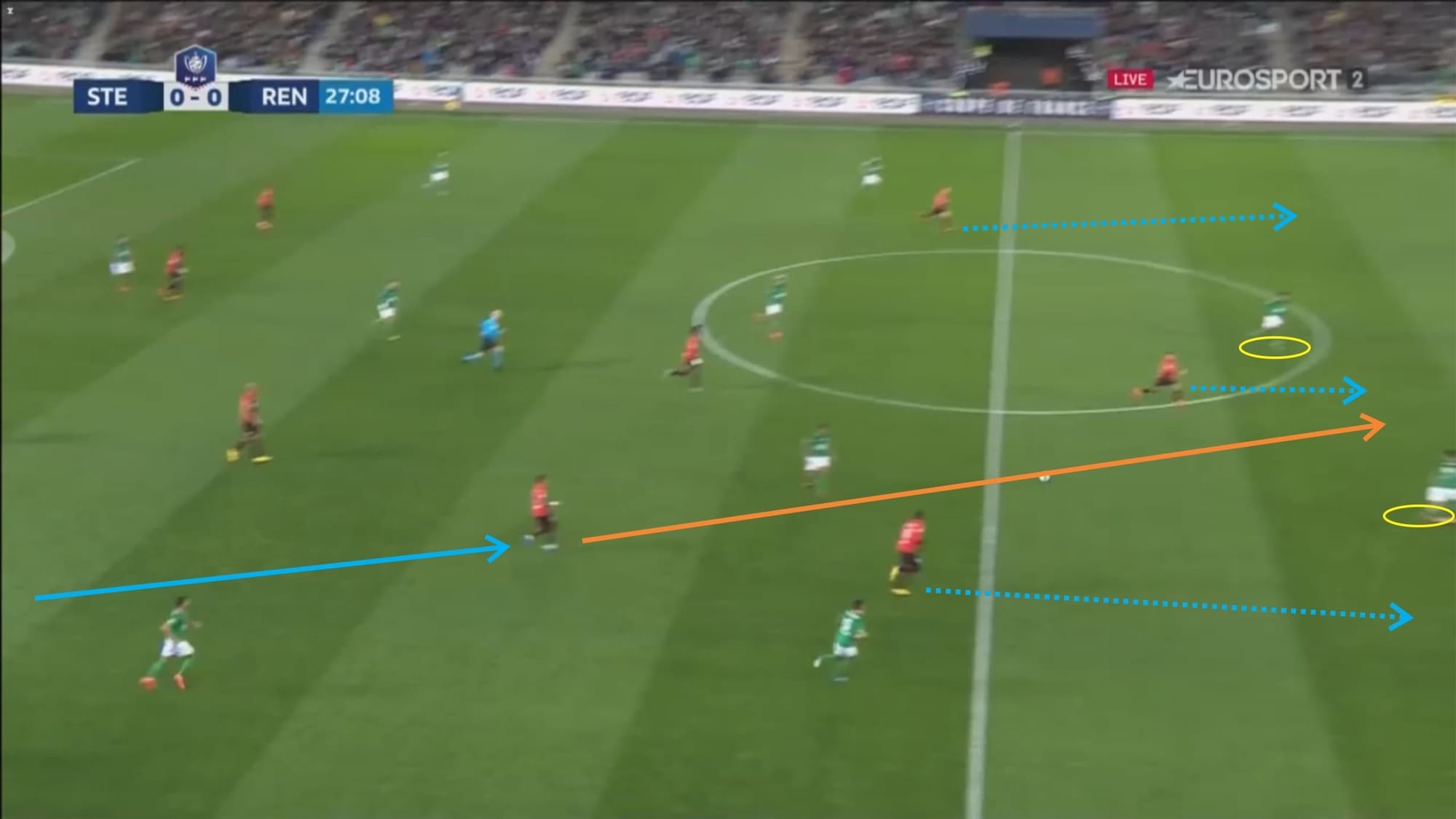

As you can see in the image above, Saint-Étienne’s block was very compact and was fairly narrow. They tended to defend with a medium block but would usually press high when Rennes were playing the ball out from the back.

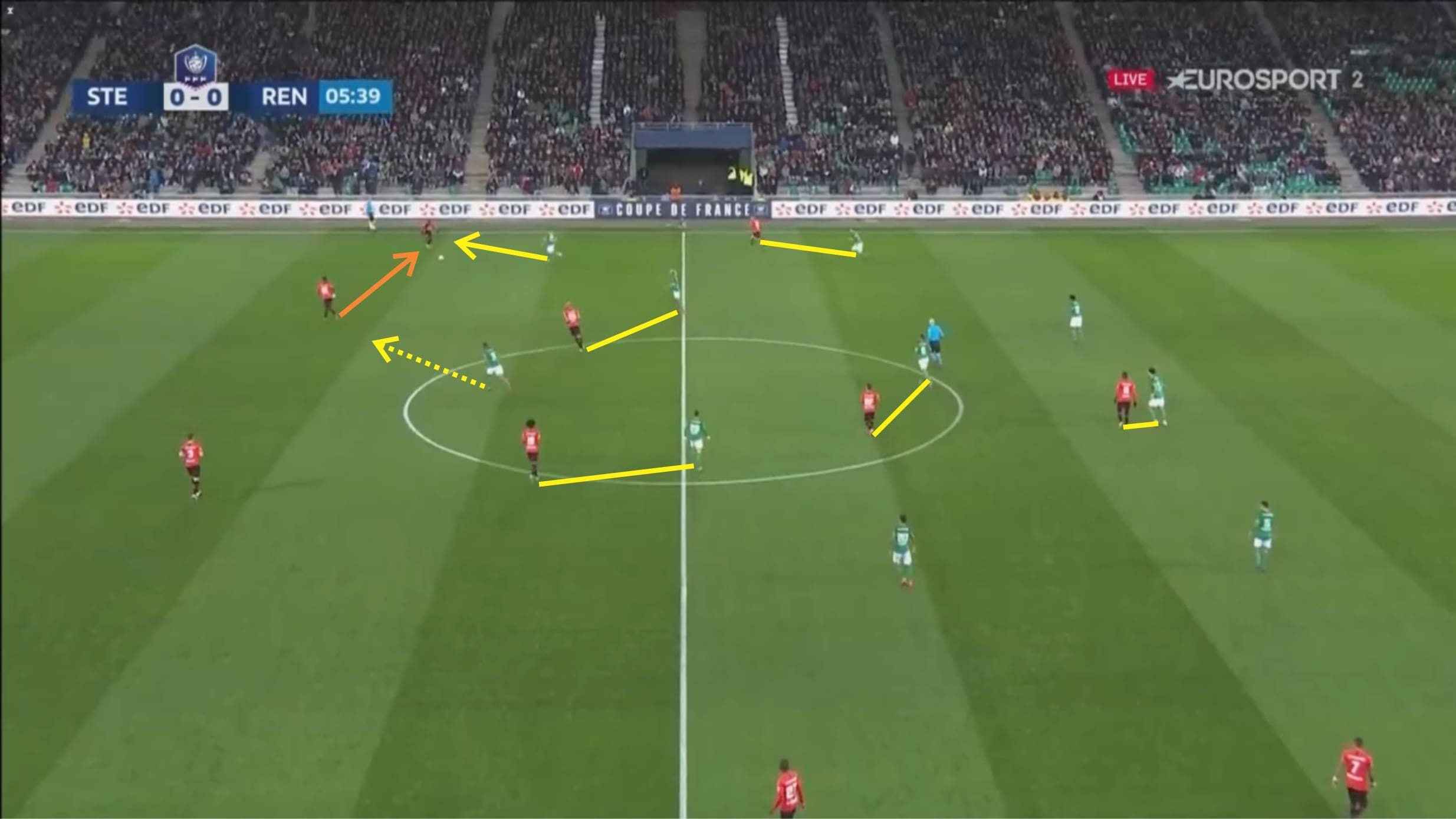

Saint-Étienne’s pressing was option-based. This means that they’d close down passing options by marking the man or passing lane but left the other option free. This forced the ball to be moved into a predictable area (the free option) which Saint-Étienne players would act quickly upon. In theory, this might sound rather similar to Rennes’ approach in pressing, however, the practice and the mission were clearly different. While Rennes mainly looked to force the ball wide and execute their pressing trap there, Saint-Étienne aimed to force the ball towards a player that was intentionally left free but would be quickly pressed once the ball was played there.

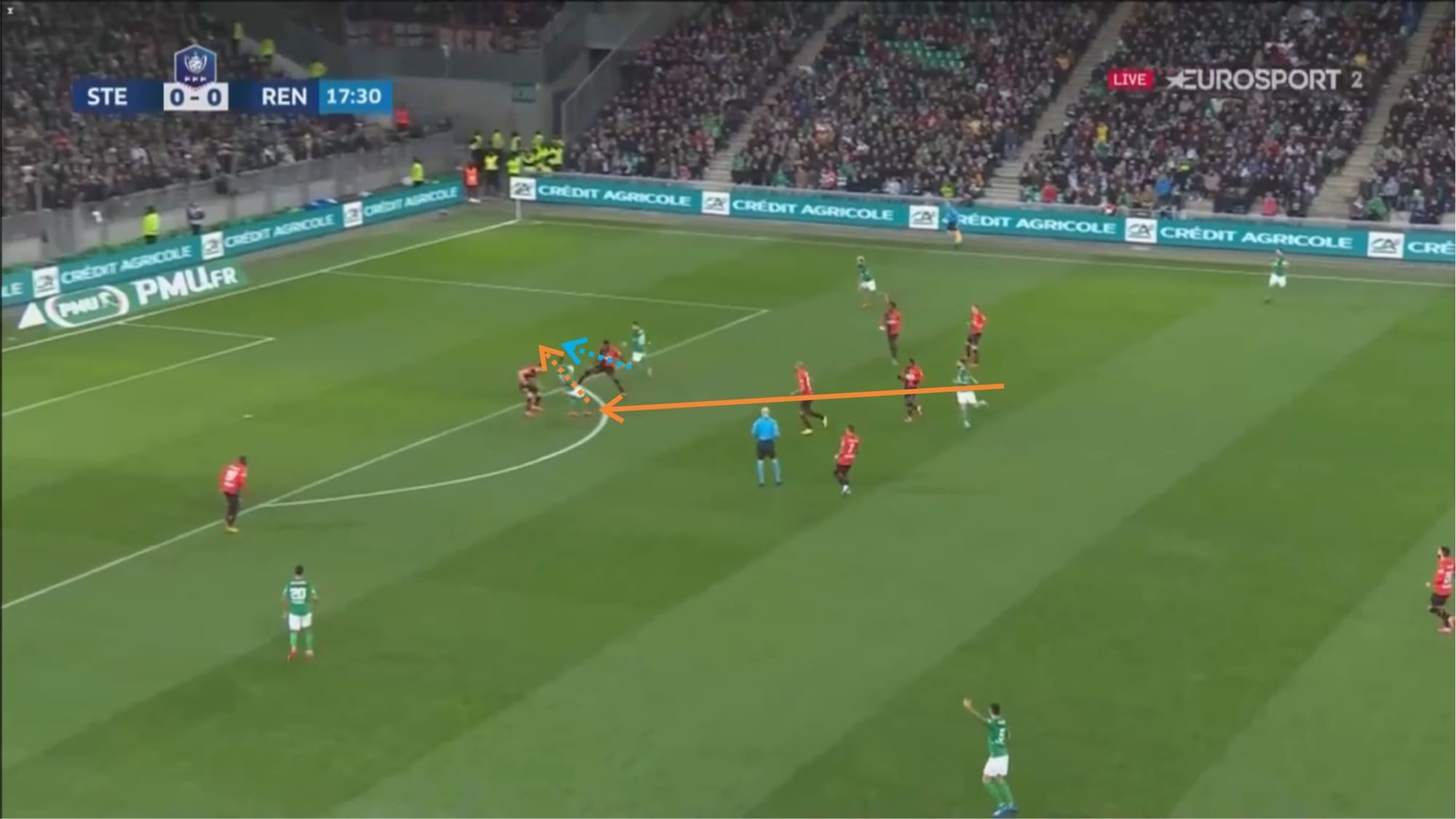

As you can see above, when the ball was played wide, the Saint-Étienne right-winger would get attracted to press the ball. Other Saint-Étienne players also marked the nearest options but the left-sided centre-back of Rennes was still free. This effectively prevented progression from Rennes.

The ball-carrier (Rennes left-back) then opted to pass the ball back to the left-sided centre-back who was immediately met with pressure from Diony (as indicated by the yellow dotted line). The centre-back then played the ball back to the goalkeeper and the latter then played it long.

Similar to Rennes, Saint-Étienne’s approach in marking was both option-oriented and passing lane-oriented. In the image above, Honorat slowly closed down N’Zonzi while keeping Benjamin Bourigeaud on his cover shadow as well as marking the passing lane towards Del Castillo alongside Camara. Notice also M’vila and Mathieu Debuchy keeping a rather close distance with the two nearest options so that they could quickly press the players if the ball was played towards either one of them.

Conclusion

Plucky Saint-Étienne earned a fantastic win in this game but their campaign in Coupe de France this season is not quite done yet as Paris Saint-Germain await them in the final.

Puel’s side defended extremely well but surely luck also played a part in the game. Rennes had an xG of 1.32 and surely they could have converted a few clear-cut chances they created in the game. Their strategy to quickly press after losing possession was highly effective to minimise Rennes’ threat on the break and their third-man mechanisms as well as fluid and flexible attack created a lot of trouble for Rennes.

Comments