Cracovia survived the relegation battle last week, with a 2-0 victory securing their place in the top-flight of Polish football for another season. Since the mid-season winter break, Cracovia’s seven set-piece goals have been crucial to their survival, which have made up 38% of their goals in the moments when the match saw both teams with an even number of players.

Cracovia stand out from a set-piece perspective due to their flexibility in being able to adapt the direction of the screen to create space in areas that are left unmarked within the opposition’s defensive structures. In the fixtures against heavy zonal setups (5+), the screen is often used to create space further away from the goal, where few man markers are present to potentially intercept the delivery. However, when the zonal presence inside the six-yard box has been thinner (3/4 players or less), screens have been used to increase the gaps between an already stretched zonal presence in front of the goal. This has made them incredibly tough to play against and score a goal roughly once every 11 corners.

In this tactical analysis, we will examine the tactics behind Cracovia’s corner kicks, with an in-depth analysis of how they are able to access different areas of the penalty box depending on the opposition structure. This set-piece analysis will also examine the details behind why they attacked each part of the box, the details behind the different screens that are utilised, and the importance of timing and coordination when using screens.

Attacking in Numbers

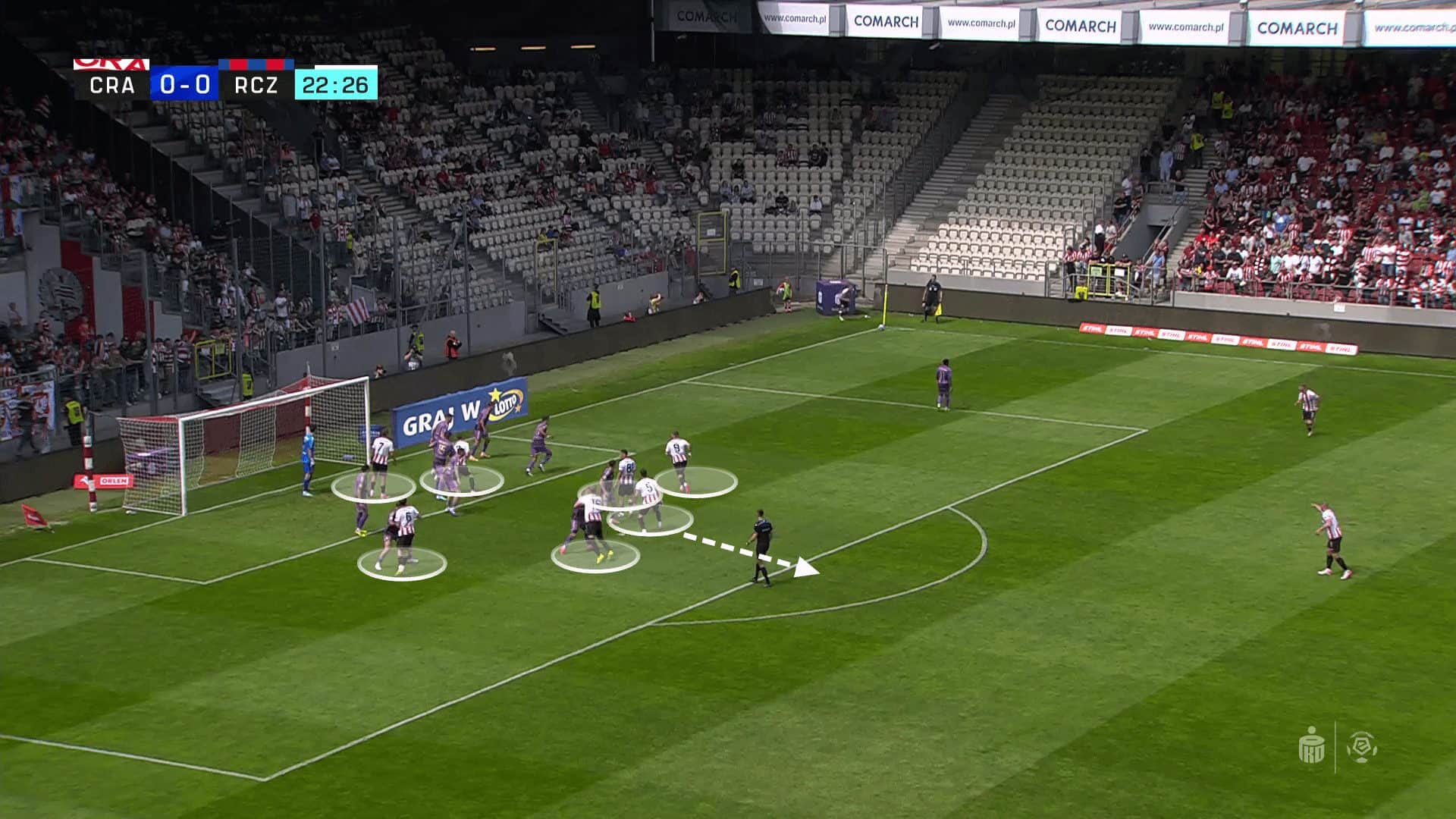

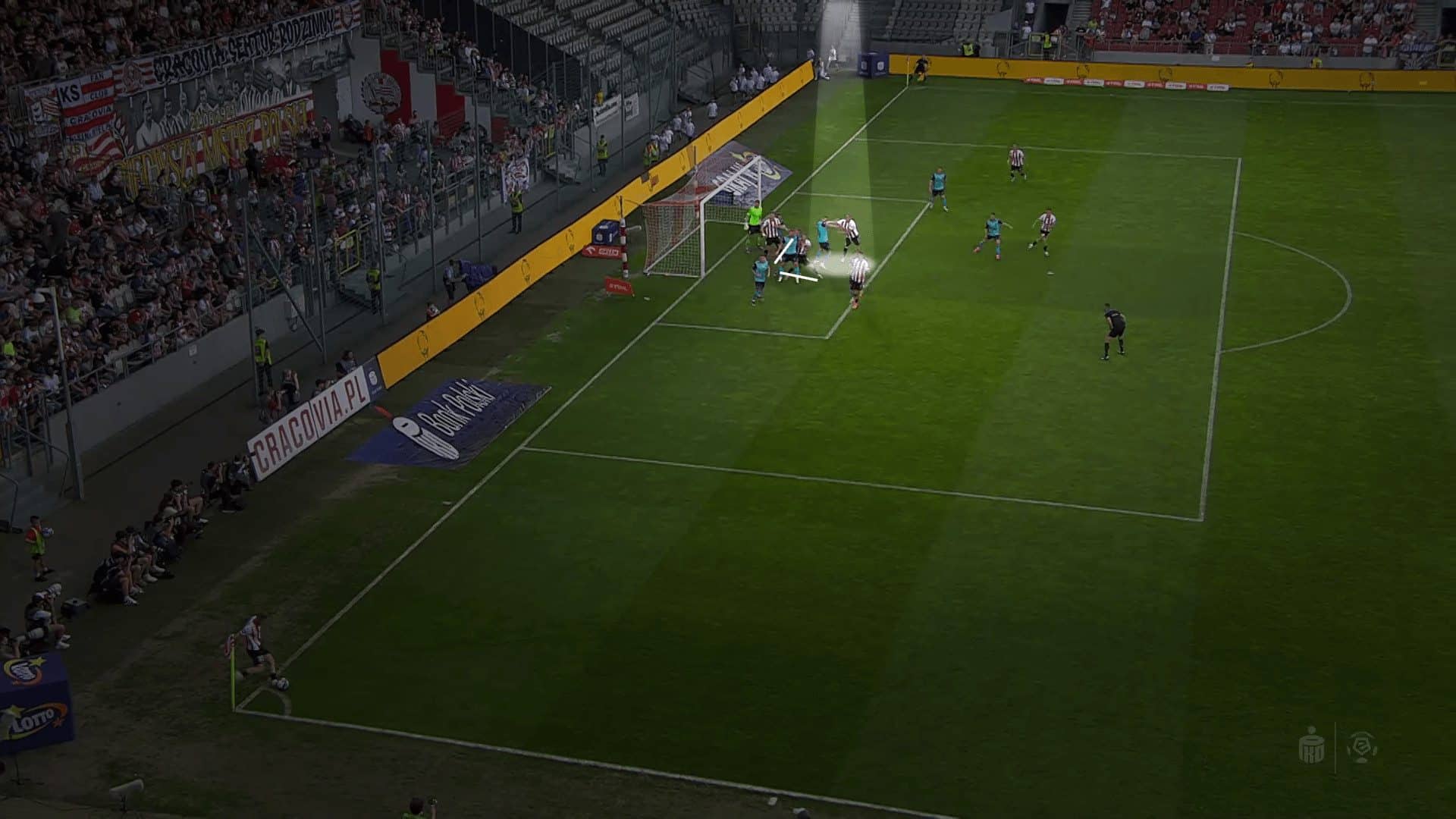

From the start, Cracovia are already at an advantage to make the first contact simply because of the number of players they use to attack the box with. Every corner kick involves six attackers, all attempting to either attack the ball or create chaos and disrupt opposition players inside the penalty area. Different routines demand different starting positions from the attacking side, but a common theme is to have a +1 overload in the area around the penalty spot, consisting of the players whose responsibility is to attack the ball. Having the +1 ensures that one player is always free to attack the six-yard box without anyone disrupting their movement toward the box so that they can use their momentum to dominate aerial duels against static zonal defenders.

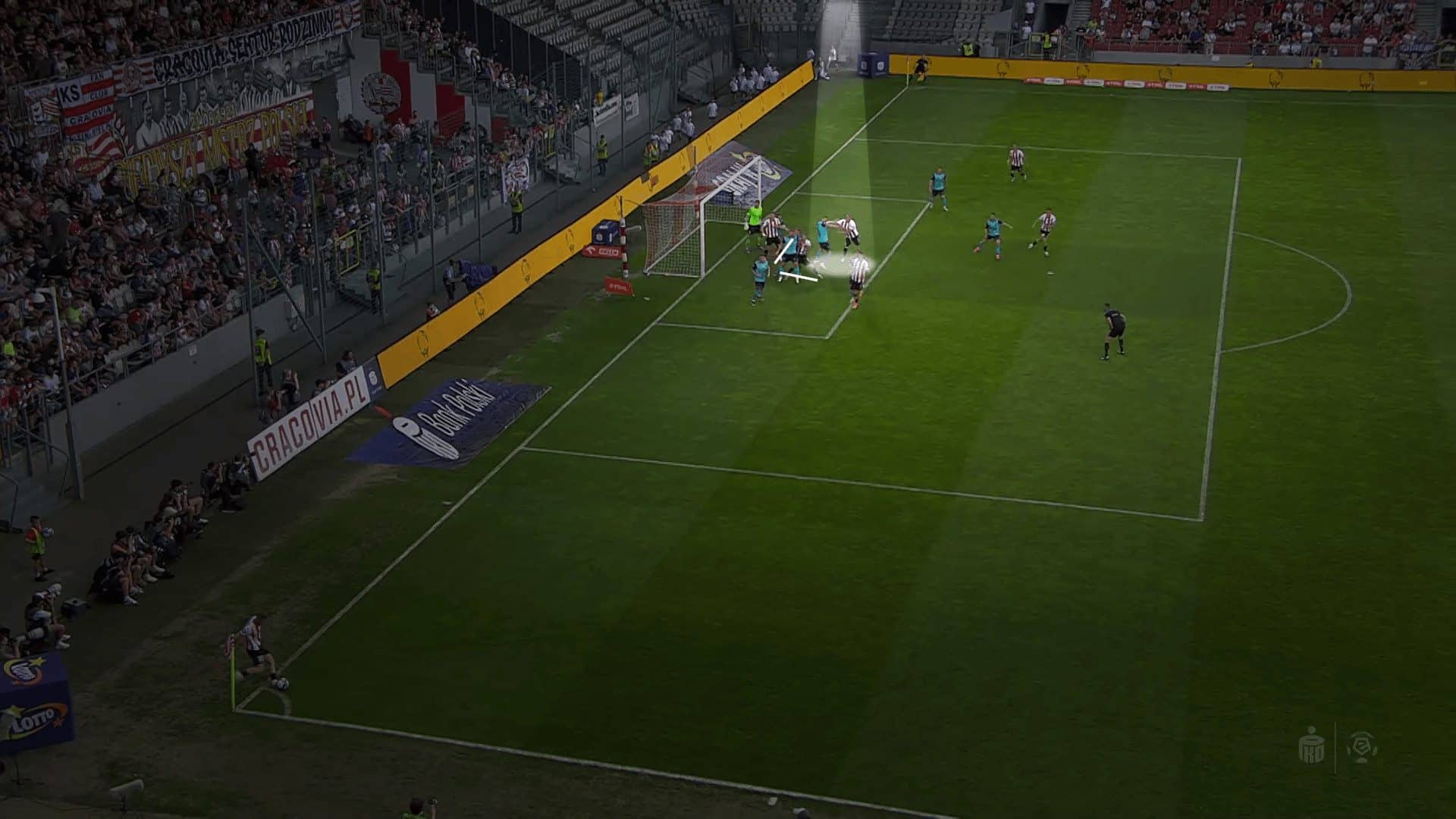

In the instance below, an original adaptation is used to free up another attacker. One player whose role is to pick up loose balls outside the penalty area starts inside the box to attract a marker to him. As the corner is taken, he retreats to his position outside of the box, leaving his marker having to scatter to pick up a different player inside the penalty box. With the correct timing, the defender has no time to mark anyone else and ends up leaving the attacking side with two attackers free to attack the six-yard box.

‘X’ v Zonal Defending

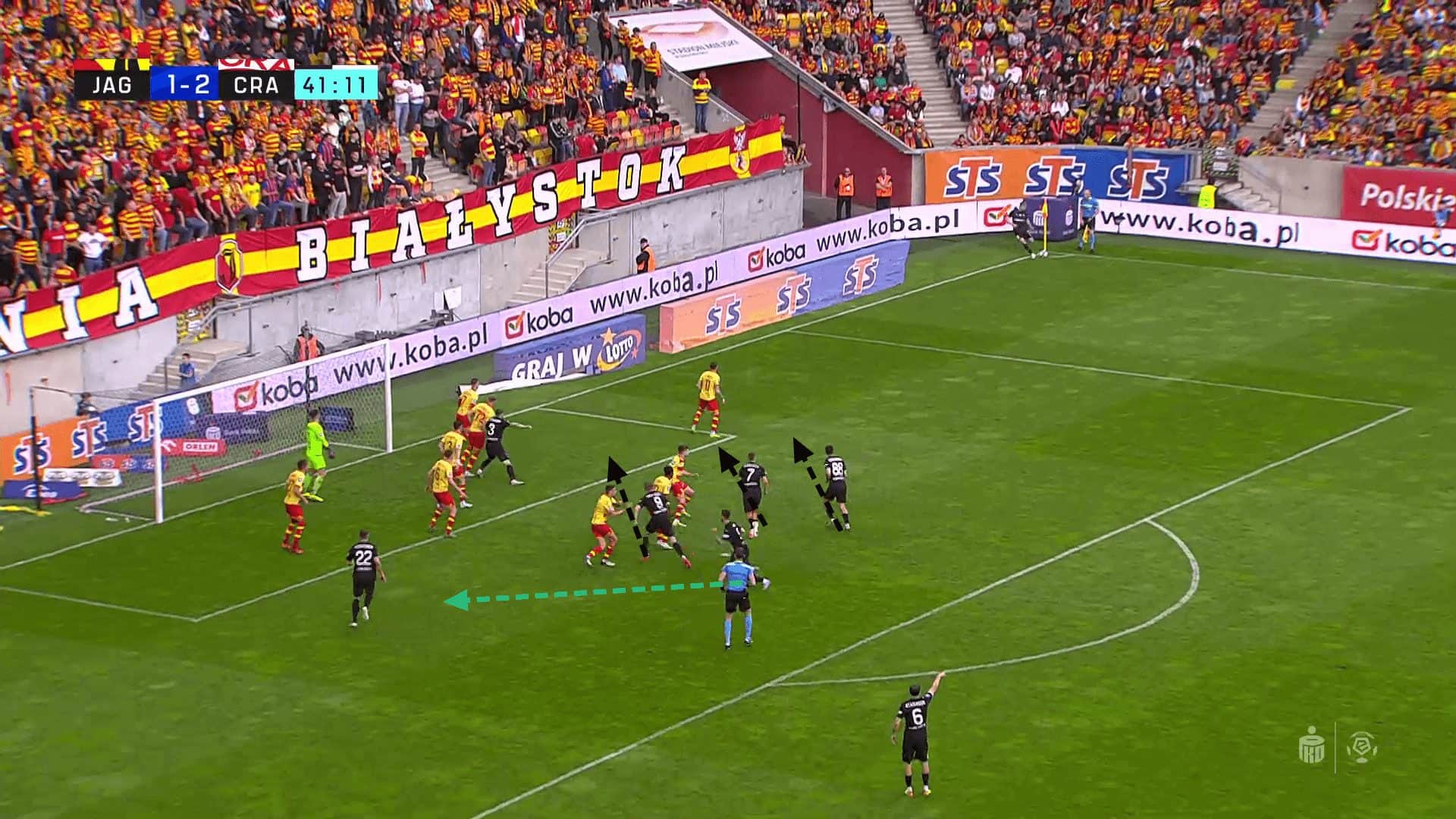

Cracovia’s encounters with heavy zonal setups, often consisting of 5 or more zonal defenders, have been a testament to their effective attacking strategies. While it may seem challenging to breach the six-yard box and make the first contact there, they have found success in the next six-yard space between the six-yard box and the penalty spot. Their routine, designed to exploit this defensive structure, involves a screen on the nearest zonal defender to the highlighted area, while the attacker, usually the +1, has a clear path into the target area. To maximize the corner taker’s delivery space, the remaining attackers make decoy runs towards the back post, where they can also pounce on rebounds or second balls.

It can be fairly simple for the opposition side to adjust and predict when this corner routine will be used as the corner taker makes the ‘x’ signal every time the routine is about to be used—something to keep in mind for other Polish sides.

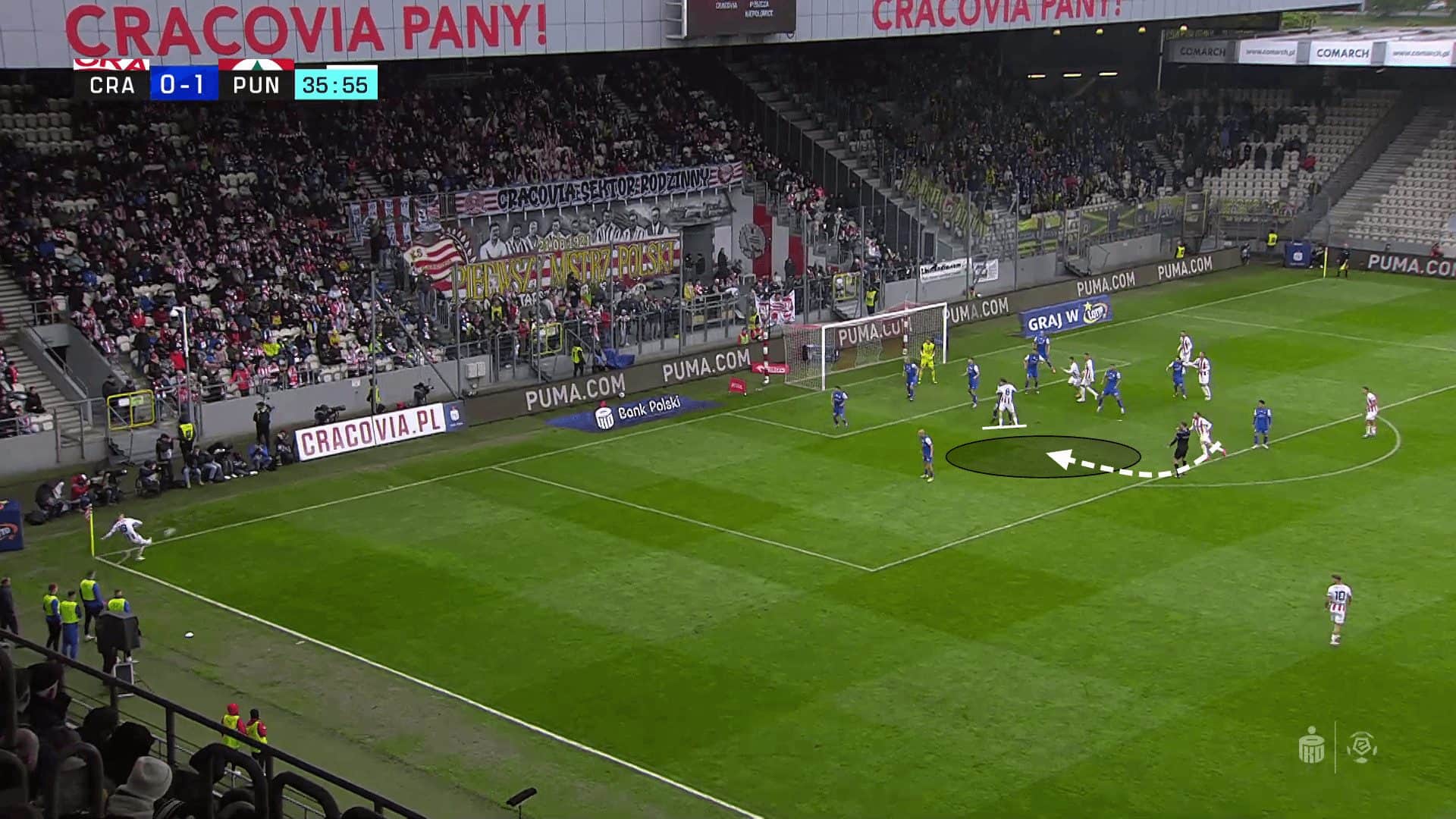

Yet again, the signal is made when there is a crowd of bodies defending the six-yard box deep. This time, because the attacker whose role is to make the first contact is marked, he must use a different tool to gain the separation necessary to attack the ball unopposed. As Arsenal have displayed consistently throughout the season, a method of creating separation when isolated is to start in the defender’s blind side. As the image shows, the attacker starts behind his marker, and when the kick is about to be taken and the defender turns to look at the ball, he makes a darting run into the space highlighted to attack the ball unopposed.

The attacker is able to arrive in the target area before anyone else, but the lack of decoy runs from surrounding teammates means that other defenders are in close proximity and attack the ball as soon as they see it is heading in their rough direction.

Other Directional Uses of Screens

As mentioned in the introduction, Cracovia are hard to defend against due to their ability to adapt depending on the opponent’s setup when the zonal defensive presence is lighter, like in the example below with three or four players in the six-yard box within the goalposts, it is easier for Cracovia to create meaningful space to attack.

What is meaningful space? When a line of six zonal defenders is present, eliminating one or two players out of that line doesn’t do much damage to the ability of the remaining four defenders to reposition themselves to cover the entirety of the six-yard box. However, when three zonal defenders are located along the six-yard box, setting a screen on just one of the defenders means that the other two defenders have too much space to cover on the near side, far side and central space of the six-yard box, and cannot support each other.

Both defenders can hold their positions to protect their zone, which leaves one of the three spaces open, or the other option is to attempt to cover two zones at once when they see runs being made towards the different spaces. When the defender jumps out of one zone to cover another, larger gaps can be formed between the defenders, and it can be simpler to find an open space to attack the ball inside the six-yard box. Furthermore, if the ball is moving towards the back side of the six-yard box, the defender at the near post cannot support the defender at the back post due to the bigger distance he has to cover.

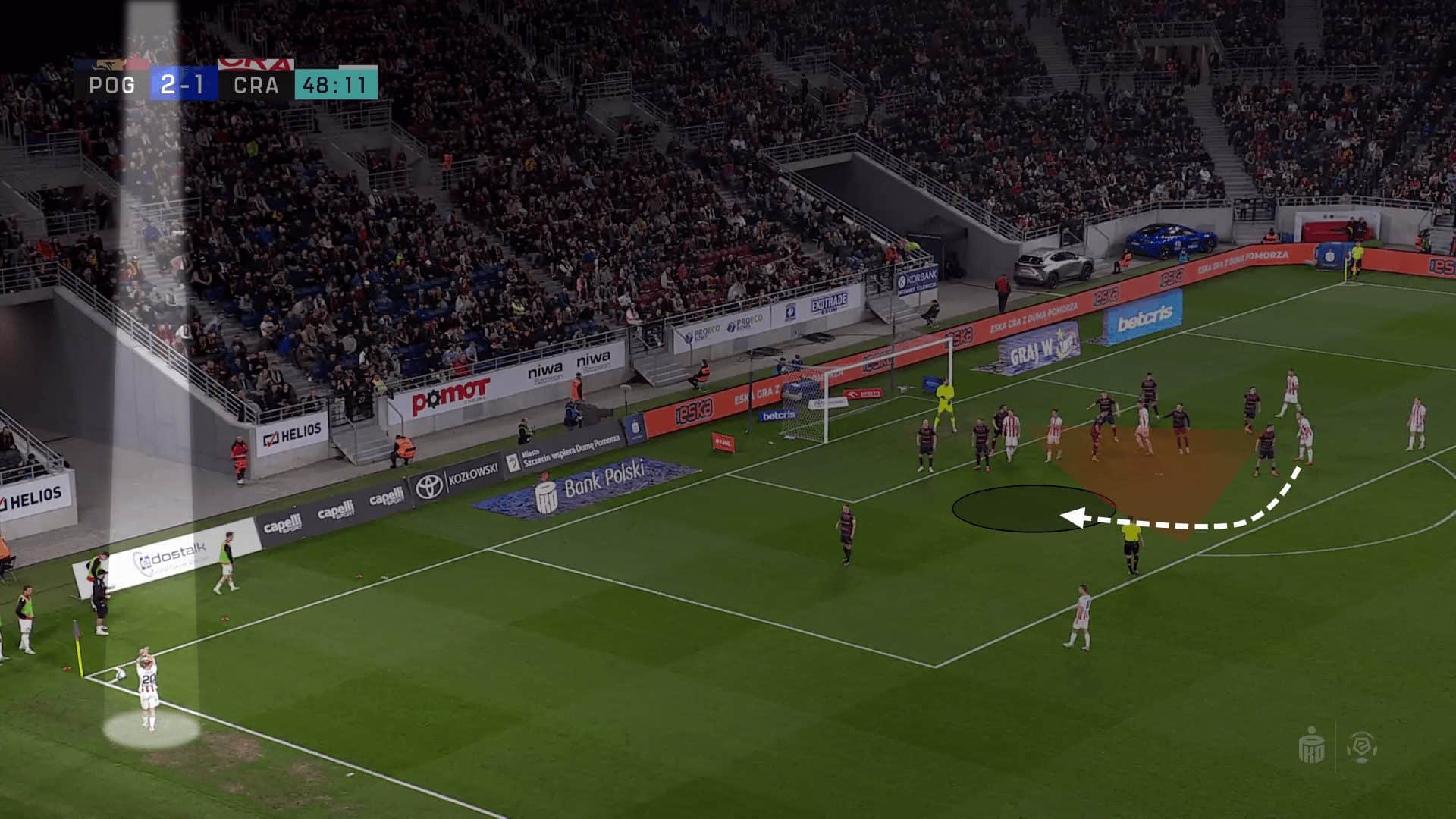

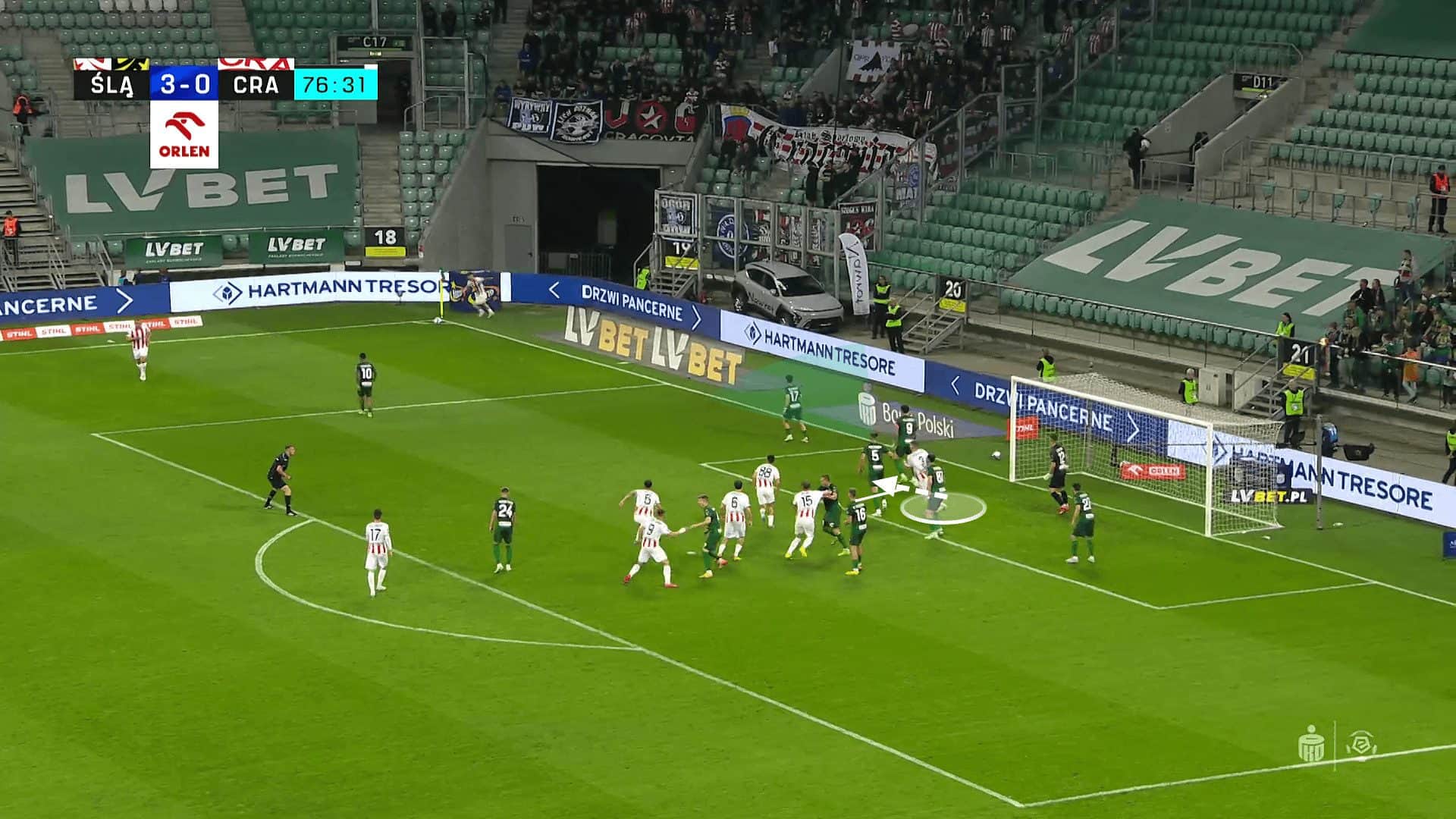

In this particular instance, two screens are made to create the central space inside the six-yard box. One screen completely cuts off the near post defender from covering the space behind him, while the second screen does the same job, just at a different angle, with the added bonus that the goalkeeper is also cut off from stepping off his line.

Michał Rakoczy’s ability to deliver quick and flat crosses into the six-yard box is key to the example below where the ball is intended for the player highlighted. Any other cross with a higher arc would likely give opponents the time to adjust their positions and prevent the 1v1 situation that occurred.

This leaves a 1v1 mismatch opportunity in the six-yard box, with Kamil Glik as the recipient.

Glik, the ex-Monaco Ligue 1 winner, is known as an aerial threat due to his ability to consistently dominate aerial duels even without separation. These sorts of players are usually the toughest to defend against, and the common solution is for one player to completely kill the attacker’s momentum while a second teammate attacks the ball. However, in this scenario, the defender is isolated and cannot focus on attacking the ball while engaged in a physical duel with the Polish man mountain.

When the likes of Glik seemingly have no separation from their marker and seem to be without an advantage, they regularly manufacture ways of winning the first contact. One trick that is commonly used is highlighted in the image below, where Glik uses a stiff arm to give himself a yard of space. Through pure physical strength, Glik is able to shift his marker a step away from him by extending his arm, where the likes of him and similar profiles of defenders like Harry Maguire use their broad-shouldered bodies to increase the distance between them and their markers. The bigger the distance, the more steps Glik is able to take in the run-up before the jump for a header.

Even if a marker can stay tight to Glik, players like him with wider shoulders can consistently win the first contact as they can lift their arm, using their forearm as a shield. The wider your shoulders are, the bigger the distance between your head and the defender’s body. That forearm can be used to prevent the defender from stepping towards you, so if a cross is going directly to Glik’s head, he can use his strength to stop the defender from approaching him, with his shoulders giving him some sort of separation to perform the header from a standing position.

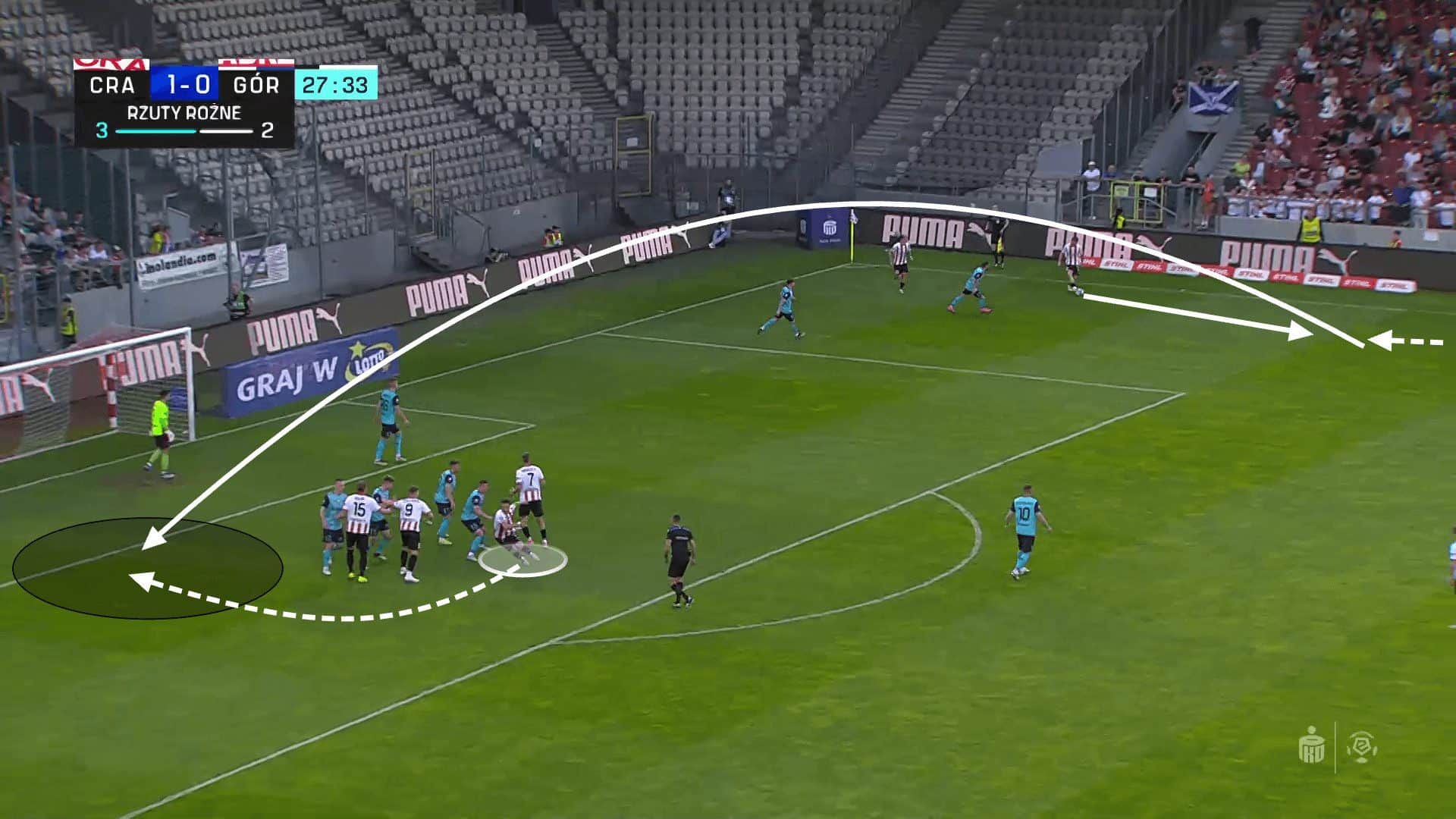

Cracovia’s use of screens is really effective due to some key steps. An effective screen is one that is less likely to be evaded by a defender. Firstly, Cracovia always executes screens from different angles. Opponents cannot feel safe at any point as they don’t know if the person standing next to them will set a screen or if they will rotate around them before setting the screen. They become unpredictable, so other defenders are unable to anticipate the location the cross is aimed at.

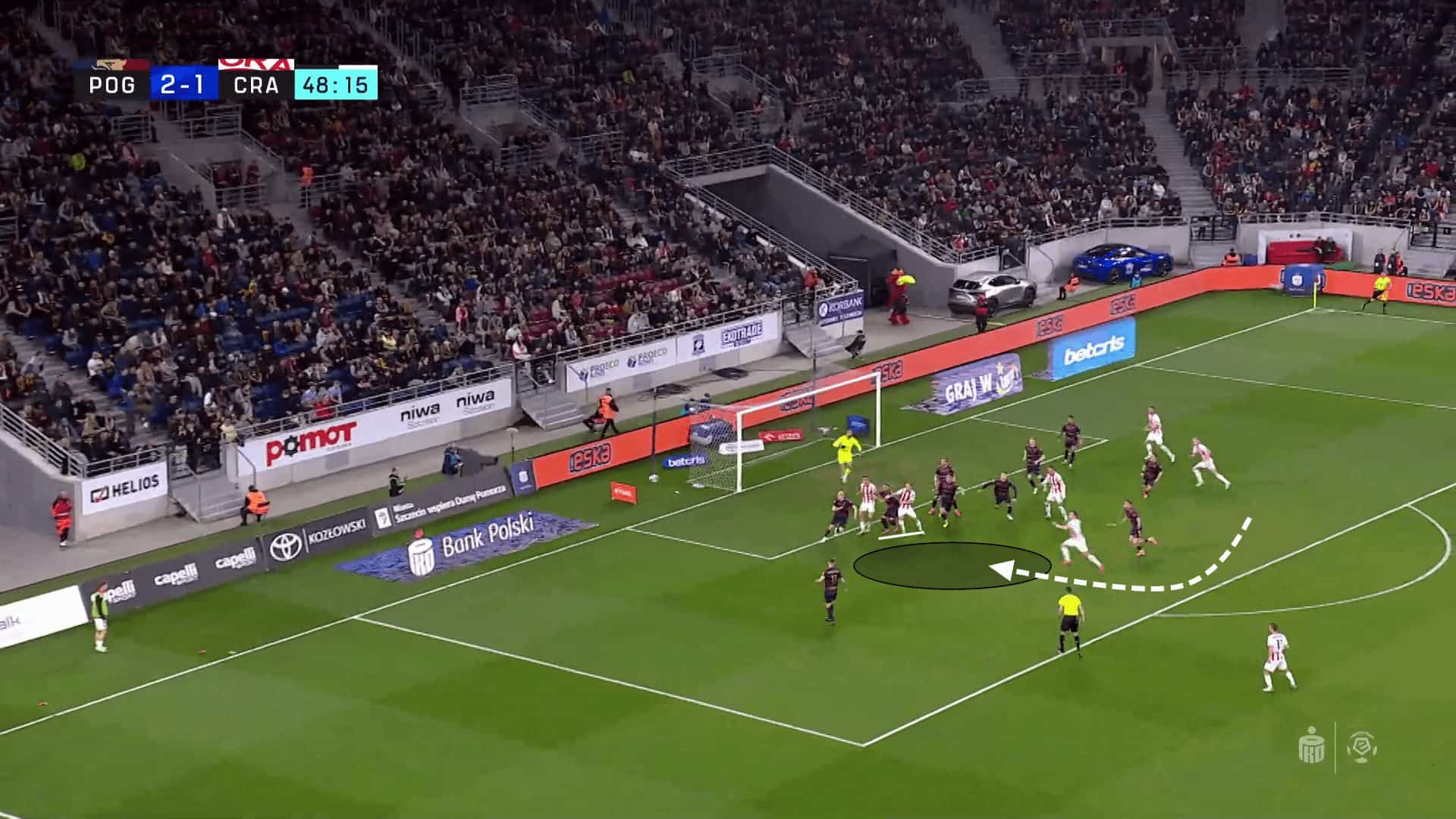

Secondly, the screen is always set last second, as the corner kick is taken. In the instance below, we can see the player arriving to set the screen from the defender’s blind side as the kick is about to be taken. Both the timing and the angle (from behind the defender) the screen is set from mean that the screen’s are highly effective, and as long as the corner kick is delivered accurately enough, Cracovia will make the first contact due to an attacker arriving in that zone without a zonal marker present.

At the start, we mentioned the use of a +1 around the penalty spot. Cracovia regularly take advantage of the overload by using decoy runs to drag the defender in one direction while the extra attacker, who is usually the target, makes a movement into a different part of the penalty area.

Cracovia have also used the short corner routine, which I recently discussed to be one of the most effective corner methods around. The short pass attracts the opposition defenders to step away from the goal, increasing the space to attack behind the last line. At the same time, a run is made towards the back post area, moving against the opposition’s momentum. This allows the attacker to arrive at the back post unmarked, although an inaccurate delivery causes the corner to come to nothing.

Summary

This tactical analysis has discussed the reasons behind Cracovia’s ability to be so effective from corner kicks. Their ability to adapt and use screens to exploit space in different directions enables them to be a threat against all sorts of defensive structures. Attackers can revolve around the defenders, causing uncertainty as to which direction the screen will come from and which space will be targeted. The revolving use of screens, coupled with the excellent timing and execution of them, means that it is tough to predict which space Cracovia are aiming to exploit, and opponents have difficulty in anticipating and intercepting the deliveries.

Comments