The emergence of top stars like Erling Haaland is nothing new to football, it happens every season. Top clubs develop top talents almost constantly and when they don’t they go to the market to get the best possible players. What’s different in the case of Haaland and other players we’ll look at in this data analysis is that he moved several times for cheap fees so now fans of every big club are asking themselves: ‘Why didn’t we sign Haaland before?’

Reports claiming the Norwegian or any other top youngster was offered to any given big club for a bargain fee before he signed for his current clubs appear everywhere. The easy answer is to blame the decision-makers and tag them as ‘useless’. But Haaland was probably offered or mentioned to every team in the top-5 leagues before RB Salzburg decided to sign him for €8 million in January 2019, and I wouldn’t think every club in the major leagues is stupid.

So the answer must lie elsewhere. In this data analysis, we’ll look at the careers of all the U23 players valued at €35 million or more by Transfermarkt, a total of 62, and analyze all the transfers they’ve had so far. Some of the questions we want to answer are the following:

Do top young players move for less than €25 million?

At what price?

How often?

At what age?

To top clubs or taking intermediate steps?

By answering these questions, we’ll have a much clearer understanding of how possible it is for top clubs to get cheap talents and how they can adapt their decision-making processes to take advantage of the opportunities that may arise before their competitors.

Do young bargains exist?

Through this analysis, when we talk about a transfer being an ‘opportunity’, we refer to it costing less than €25 million. We’re assuming that if a player didn’t move for less than that it’s because he was either too risky or already too expensive. In the same line, if a player moved for less than €25 million we consider other clubs could have taken him too so the opportunity was obviously there.

Imagine Declan Rice’s example. If anyone had offered €20 million for him at 16 before he made his first-team debut, West Ham would have probably sold him so we can’t say strictly that the opportunity to sign him for a “low” fee has never existed. However, if we’re realistic, the risk of making an offer like that is too big for anyone to assume it so we are assuming the opportunity never existed in the real world.

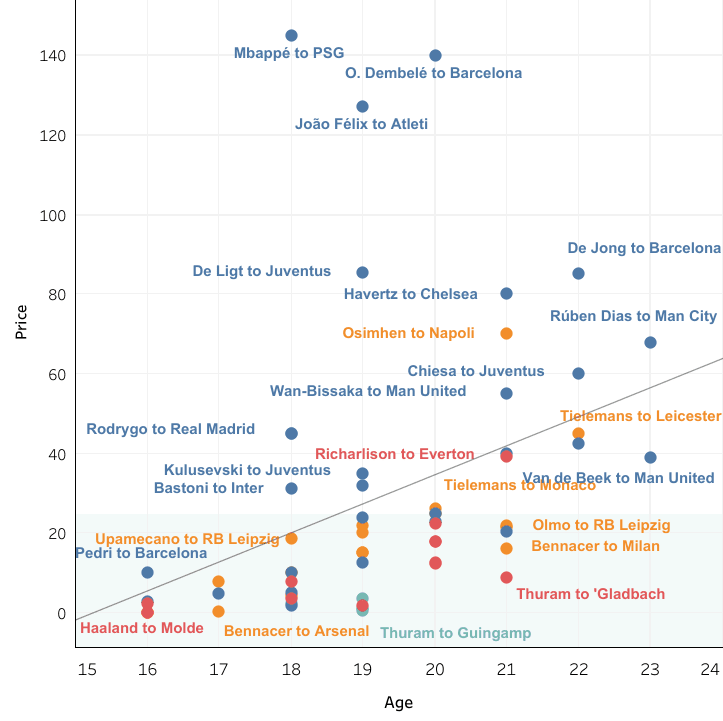

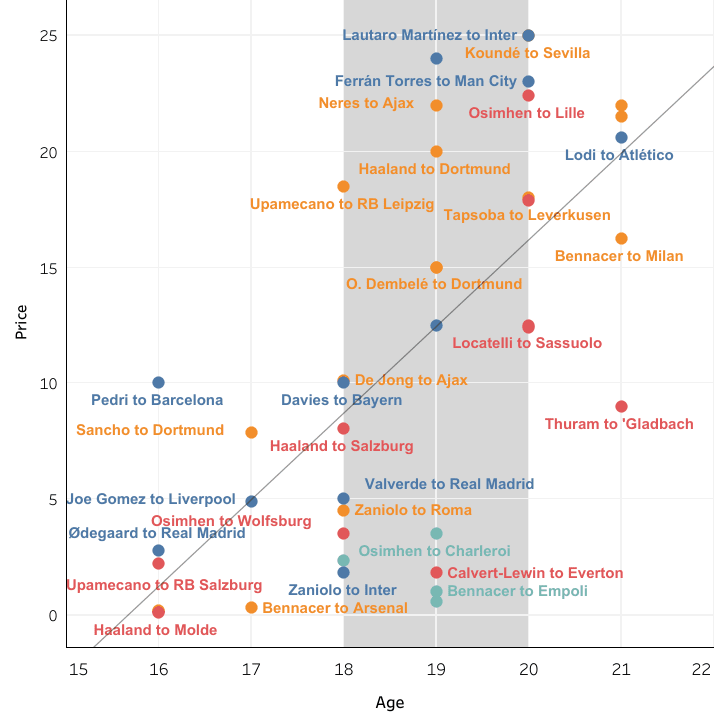

The 62 players whose careers we’re analyzing here have had a total of 69 transfers in their careers. If we don’t consider the 15 of them who haven’t moved from their youth club yet, that leaves us with 1.47 transfers per player. We can see all those transfers in the next chart.

Of those 69 transfers, 21 of them were for more than €25 million, which is the limit we have set to separate bargains and expensive transfers. Considering every player we have analyzed is valued at €35 million or more, that seemed a decent limit.

Looking again at our population of 62 players, only 33 of them have ever moved for less than 25 million. As explained before, we can assume that 46.8% of the players have never been available for a realistic fee of less than €25 million. The complete list of top U23 players who have never moved for a low fee: Tammy Abraham, Trent Alexander-Arnold, Ansu Fati, Houssem Aouar, Alessandro Bastoni, Eduardo Camavinga, Federico Chiesa, Matthijs de Ligt, Gianluigi Donnarumma, Phil Foden, Gabriel Jesus, Mason Greenwood, Achraf Hakimi, Kai Havertz, Callum Hudson-Odoi, João Félix, Kylian Mbappé, Mason Mount, Mikel Oyarzabal, Marcus Rashford, Reece James, Declan Rice, Rodrygo, Rúben Dias, Bukayo Saka, Youri Tielemans, Donny van de Beek, Vinícius Júnior and Aaron Wan-Bissaka.

Only five players (8.1%) have moved three times for low fees: Ismaёl Bennacer, Haaland, Victor Osimhen, Edmond Tapsoba and Nicolò Zaniolo. Another five moved two times before costing more than €25 million: Dani Olmo, Richarlison, Theo Hernández, Marcus Thuram and Dayot Upamecano. Lastly, 37.1% of the 62 players moved just one time for less than the stated fee.

We can conclude that opportunities do exist but not as many as it seems. For almost half of the players we’re considering, the opportunity to get them as a bargain has never existed. And just 16.2% of them have been a bargain more than one time in their careers. Almost all players who are bargains more than one time come from very low leagues so they can’t go directly to a top club and those intermediate steps aren’t usually for big fees.

A few examples. Haaland went from the Norwegian second division to the first, then to the Austrian Bundesliga and then to the German Bundesliga, with every step costing less than €25 million. Tapsoba went from Burkina Faso to the Portuguese second division, then to the first and then to the German Bundesliga, but never for a top club who fights for the league title. Others like Zaniolo or Bennacer moved quickly from one team to another at very young ages before establishing themselves as top players.

The answer to the question in the title of this section is ‘yes’. Young bargains do exist. But not as often as it may seem. 83.8% of the top young players have moved once or not moved at all while still being opportunities. So even if the opportunities do exist, they’re scarce and most of the time they only appear once.

What’s the price of a top young player?

Having looked at all the movements these players made until now, we see that the average price clubs pay for a top talent before he’s 23 is 25.92 million euros. But the price varies a lot depending on other factors like age, selling and buying club, etc. Looking at the median of the transfer fees (the value that has half of the observations below it and half above it; the 50th percentile), we see it’s 16.2 million euros. Half of the top young talents with a top young talent involved were for less than 16.2 million euros.

If we consider a top young player to be cheap if he costs less than 25 million euros, then the statistics in the previous paragraph answer the question asked in the previous section. And the answer is again positive, there are opportunities to get relatively cheap top talents.

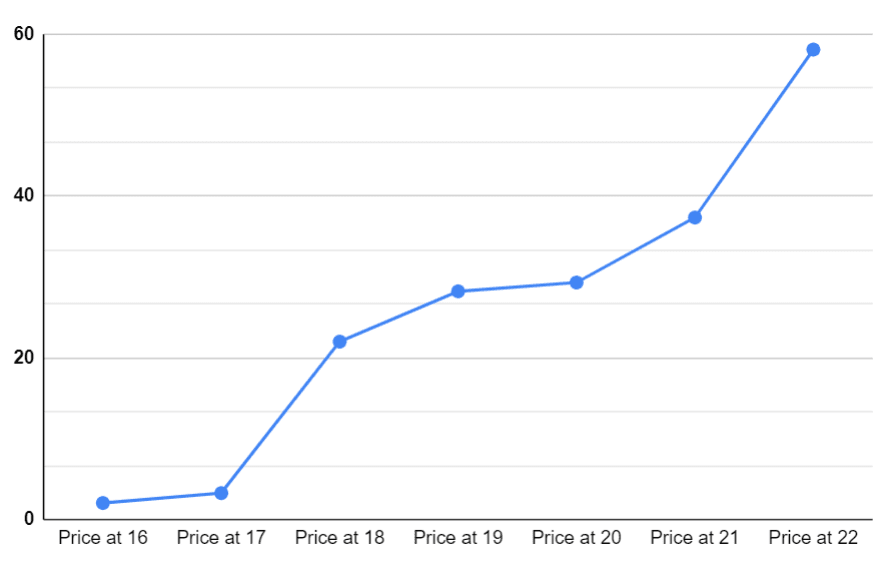

If we look at the age when these transfers happen, the average is 19.01 years old. Age itself isn’t of much help but if paired with the average price for each age, then it serves us as a measure for risk. When a team signs a 16-year-old player, the value is usually lower because the risk of that player not fulfilling his talent is much bigger. As time passes by, it’s easier to have a clearer view of what the level of a player is going to be, so it’s natural that their price increases with time.

In the preceding graph, we can see exactly that. With an average price of 2.04 and 3.26 million euros, players aged 16 and 17 respectively are accessible to lots of clubs, even if the increase in the price in just one year is 59.8%.

The big jump comes when the players turn 18 with an average price of 21.99 million euros. Apart from the decreasing risk, there’s another factor that explains this 574% increase in the value: transfer regulations. Before turning 18, players can only move within their own country or the European Union for those who apply. When they turn 18, the potential buyers increase a lot, especially for South American top talents who are usually expensive and attract interest from big clubs in Europe.

The average prices don’t increase too much from 19 to 20 years old: 28.22 and 29.3 million euros. But for slightly older players, the price again goes up a lot as some of them are already established stars in the top leagues and aren’t bought just because of their potential. Average prices at 21 and 22 years old are 37.35 and 58.13 million euros.

Without looking at the statistics it already seemed logical that the older and more established a young player is the higher his price. In this section of the analysis, by looking at the average prices for different ages, we’ve come to a more specific conclusion and knowledge about how much the prices increase and at what age players start to turn very expensive.

Can top clubs get young bargains?

We’ve already seen in this data analysis that a majority of the current top youngsters have been available for less than €25 million at some point in their careers. But that doesn’t automatically mean big clubs have made a mistake by not signing them at that time. Lots of players need to take intermediate steps to continue their development and make sure they get playing time.

Again, let’s use Haaland as an example. If he had gone from Byrne in the Norwegian second division to FC Barcelona he wouldn’t have got that much playing time and maybe his growth wouldn’t have been the same. When top clubs get a young player for a low fee they take a higher risk as they usually can’t grant playing time and need to rely on loans or use a very young player in a highly competitive environment.

For this data analysis, we have considered teams who realistically fight for one of the top five European leagues to be top clubs. Our list of top clubs: La Liga – Real Madrid, FC Barcelona, Atlético de Madrid; EPL – Manchester City, Man United, Chelsea, Liverpool; Bundesliga – Bayern Munich; Serie A – Juventus, Inter Milan; Ligue 1 – PSG.

28 out of the 69 signings we’re considering have had a top club as the buying part (40.6%). But only 11 have had a fee of less than €25 million. So just 15.9% of the transfers involving one of the top young players have been to top clubs and for a low fee. Considering all the players we’re analyzing could be playing at the highest level, that’s a very low percentage and show that even if top clubs can get top young players for a small fee, they still need to spend big to reduce risks and get the best players.

Top clubs have spent an average of 46.25 million euros per transfer with top young talents involved. Transfers like Mbappé to PSG (€145 million), Ousmane Dembelé to FC Barcelona (€140 million) or João Félix to Atlético de Madrid (€127.2 million) are clear examples of top clubs spending stratospheric figures to secure the services of top young talents.

The average age of the players at the moment they are transferred to top clubs is 19.46 years old. Cheap transfers happen mostly but not exclusively for very young players signing for top clubs before they’re too well-known (Federico Valverde to Real Madrid for €5 million when he was 18, Pedri to FC Barcelona for €10 million when he was 16, Joe Gomez to Liverpool for €1.9 million when he was 17 or Alphonso Davies to Bayern for €10 million when he was 18).

If a player enters his twenties and is already regarded as a player who can perform in a top team, then his value rockets. Taking them very young is the risk top teams must take to secure low fees for top talents. Both the average price and age when top clubs are involved are much higher than the averages for the rest of the clubs (14.53 million and 18.71 years old), which shows how top teams are usually more risk-averse as they can’t secure a player’s development at some points in their careers and by taking ready-made players they pay a much higher price.

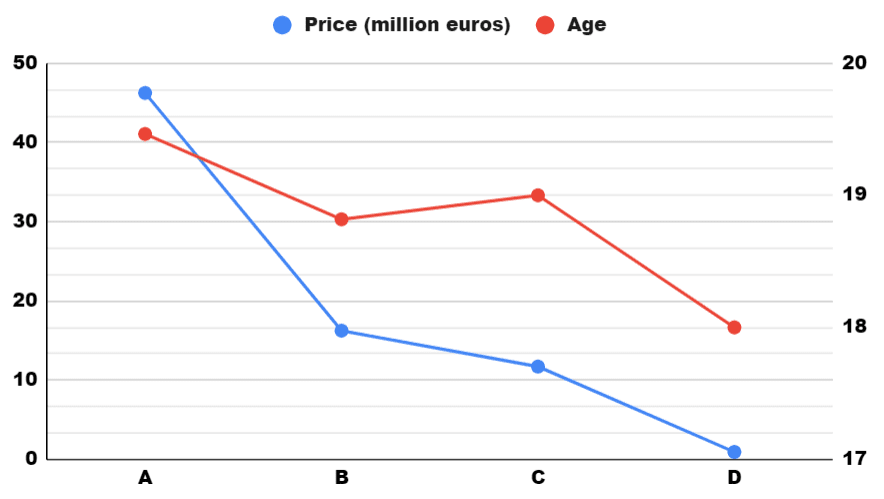

In the next chart, we can compare how much do top young players cost to teams in different categories and at what age they move there. We’ve already mentioned which teams are in the A category. For the B category, we’ve taken teams who are usually in the UEFA Champions League (Dortmund, Monaco, Arsenal, Sevilla or Ajax to name a few). For the C, top teams in minor leagues and other teams in top-5 leagues (Everton, Sassuolo, RB Salzburg, Dinamo Zagreb). For smaller teams, we have used the D, including clubs like Charleroi, Empoli or Molde.

The division is subjective but it explains the differences quite well. The lower the level of the team, the less they pay and the younger they get the players. A good explanation for this has already been mentioned previously in the analysis: smaller teams can afford to gamble with riskier players because they don’t need them to perform at the absolute highest level to benefit from their signings.

Charleroi taking Osimhen when he was 19 is a good example. They got a good young player who failed to impress at a bigger club for just €3.5 million. At that time, Osimhen qualities were there but it looked very risky to pay more for him given he had already failed at a top league. But for Charleroi, it was a much safer bet as in the worst scenario they would be getting an expensive squad player but in the best one and the one that actually happened, they got a fantastic player who performed excellently and was sold for 22.4 million euros to Lille just a year later. It’s very unrealistic to think that Napoli could have signed him for a twentieth of the price they paid for him two years later, or at least it would have required a vision and knowledge no big club had at that time.

Data overview

Let’s look at a couple of general charts to conclude this data analysis. In the next graph, we see the age and price of every transfer we’ve considered in this analysis except for the three most expensive (João Félix, Mbappé and Dembelé to Barcelona) for clarity purposes. The colours represent the team’s category and we’ve added the 25 million euros mark to separate “bargains” from expensive transfers.

We see there’s a clear tendency for the price to increase as the players get older. This is consistent with the risk explanation as clubs know better what they’re getting when the player is older and more established as a professional. It’s worth noting the three most expensive signings – João Félix, Mbappé and Dembele – aren’t the oldest ones. These three players were already impressive at 18, 19 and 20 respectively so top clubs were caught in a race to sign them.

This simple model indicates these players’ prices increased an average of 7.78 million euros every year. This can be interpreted as the cost clubs need to assume as a counterpart for the decrease in the risk they take when signing older players.

It’s also noteworthy that 90.95% of the transfers costing more than 25 million euros (17 out of 21) were made by A-category clubs. This also shows how strongly Napoli believed in Osimhen, Everton in Richarlison and Monaco and Leicester in Tielemans, as those are the four transfers of over 25 million euros that didn’t go to absolutely top clubs.

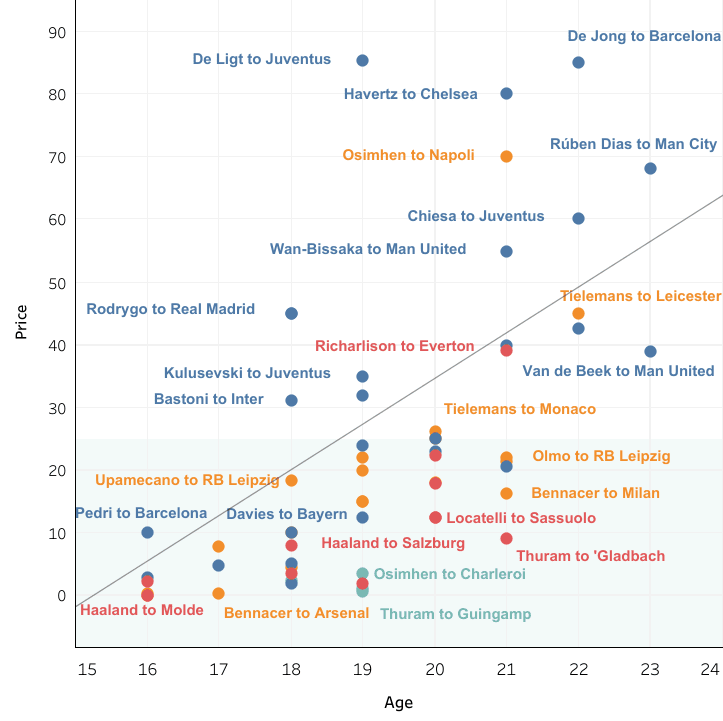

If we focus just on those transfers we consider cheap (25 million euros or less), then we get the next chart. The colour scheme is the same as in the previous one.

Here we notice a very interesting trend. Among the “bargains”, there’s only one who cost more than 11 million euros before being 19: Dayot Upamecano when he signed for RB Leipzig. On the other hand, only one player aged 20 or more cost less than 11 million euros: Marcus Thuram when he signed for Borussia Mönchengladbach.

This divides the cheap young players into two very separate categories: under-18 “top bargains” and over-20 “premium bargains”. The former is accessible to most clubs in the top-5 leagues and some of the big ones outside them, while the latter is the target of category A or B clubs as smaller teams can rarely afford them.

Conclusion

Considering all we’ve seen in this data analysis, we are in a position to suggest some ways top clubs can make sure they get the best talents before they’re too expensive.

First, it’s clear that most players need an intermediate step before joining an elite club. Playing time is crucial for their development and except for some exceptionally talented players, footballers at these ages will find it difficult to enjoy minutes in a top club.

Loans are a possible solution to this issue. If a top club gets a good player soon and then manages to make him play at a higher level every year, the player will reach a point in which he’s ready for the parent club’s first-team. A similar situation would happen with associated clubs like Salzburg and Leipzig.

Odegaard has been on loan at Vitesses, Heerenveen, Real Sociedad and now Arsenal but he’s still considered a top talent and is expected to play for Real Madrid. Upamecano was at both Red Bull teams before signing for Bayern. Osimhen played for Wolfsburg, Charleroi and Lille before costing 70 million. If clubs can replicate this kind of career with a good loan system, they’ll be able to get the players for free and then control their development and benefit from their value growth. The Chelsea trio of Abraham, Reece James and Mason Mount are a great example of this, having been on loan at a combined total of six clubs before establishing themselves at Chelsea.

Second, having a good academy setup to get the best players at a very tender age and develop them into first-team stars is a very cost-effective way of getting top players. We have already mentioned that 17.9% of the U23 players valued at more than 35 million euros haven’t moved from their first-ever team. Producing just one of these players every five years would probably justify and cover the cost of running the academy, while also adding an identity and pride that is difficult to get from bought players.

And lastly, clubs must be open to new ideas and willing to look everywhere to find top talent at a decent price. The players we’ve considered in this analysis have played in the Norwegian, Portuguese or Brazilian second divisions (Haaland, Tapsoba or Richarlison) or the English League One (Calvert-Lewin), some were still playing youth competitions in Spain, Italy or the USA (Dani Olmo, Zaniolo or Christian Pulisic and Gio Reyna) and others were at a top-5 league but weren’t enjoying enough opportunities or weren’t valued as much because they weren’t playing for top teams (Osimhen, Moussa Diaby, Bennacer or Manuel Locatelli).

Having a scouting team you can trust and not being guided just by the current situation of a player will open up new ways of seeing things that can result in better and more efficient decisions. If scouts trust what they see instead of getting carried away by everything that surrounds the player and the people making decisions trust their scouts, then the conditions are set to be able to find hidden gems.

Comments