Each manager, player and fan has their preferred pressing system. Some love the aggression of a good high press, others like the versatility of a mid-block, while still others prefer the security of a low-block.

This data analysis is designed to look past preference and identify which teams in UEFA’s top five leagues have been the most successful at keeping the ball out of the back of the net. After identifying the teams, the goal is to then look deeper into their pressing styles.

The working idea here is that there is no one way to press. No one way is better than another, but one style will be better suited for specific teams than others.

This article is part data analysis and part tactical analysis. We will use data to identify the top defensive teams across those five leagues, then create a focus group and look at more in-depth statistics on each of the involved clubs. We will then use that data to identify the pressing style of each of these teams and look at the underlying tactics. In the end, the goal is to give some ideas on structuring pressing systems regardless of where your team likes to confront the opposition.

Identifying the top defensive teams in UEFA’s top 5 leagues

In order to dig into an analysis of Europe’s top defensive teams, we will first have to find them. To do that, we turn to Wyscout’s statistical database. Using data, we will identify the clubs in UEFA’s top 5 leagues that have had the most success keeping the ball out of their own net.

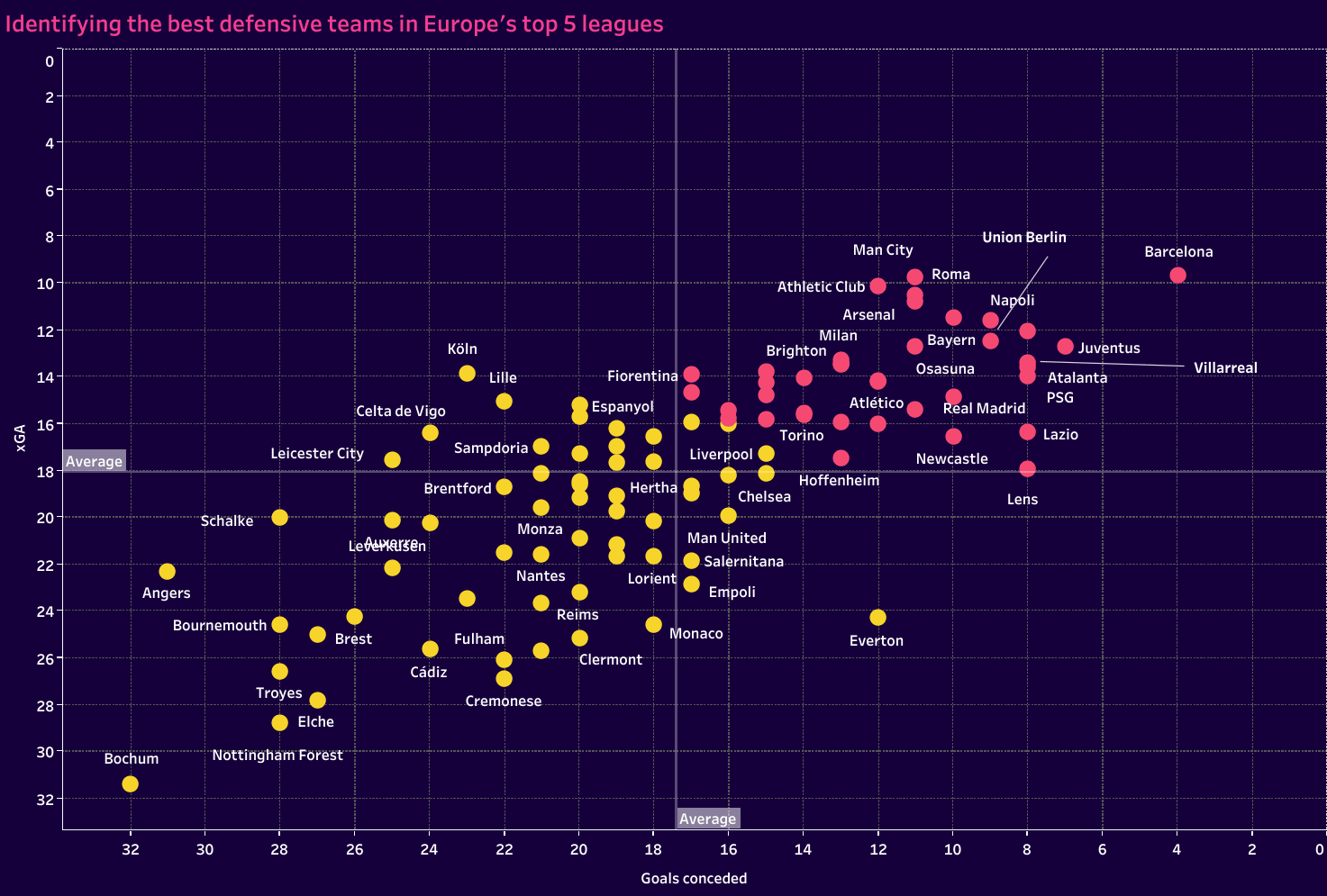

Let’s start with a simple chart plotting goals conceded by xGA. The top right quadrant represents the top defensive performers across the two metrics. Note that the statistics are based on league play as of early November, which is when the foundation of this project was laid.

Despite their Champions League catastrophe, Barcelona claims the top spot in both goals conceded and xGA. Serie A is represented by Juventus, Napoli, and Roma. From the Premier League, we have Manchester City and Arsenal, the league’s top two clubs with nearly identical numbers. Finally, over in Germany, Union Berlin’s hot start was a product of their success out of possession. They have stumbled, greatly, since these stats were collected, but we do get a sense of where their early success came from. Heading into the World Cup break, they now sit behind Bayern Munich, the Bundesliga leaders and Union Berlin’s closest German opponent on the chart.

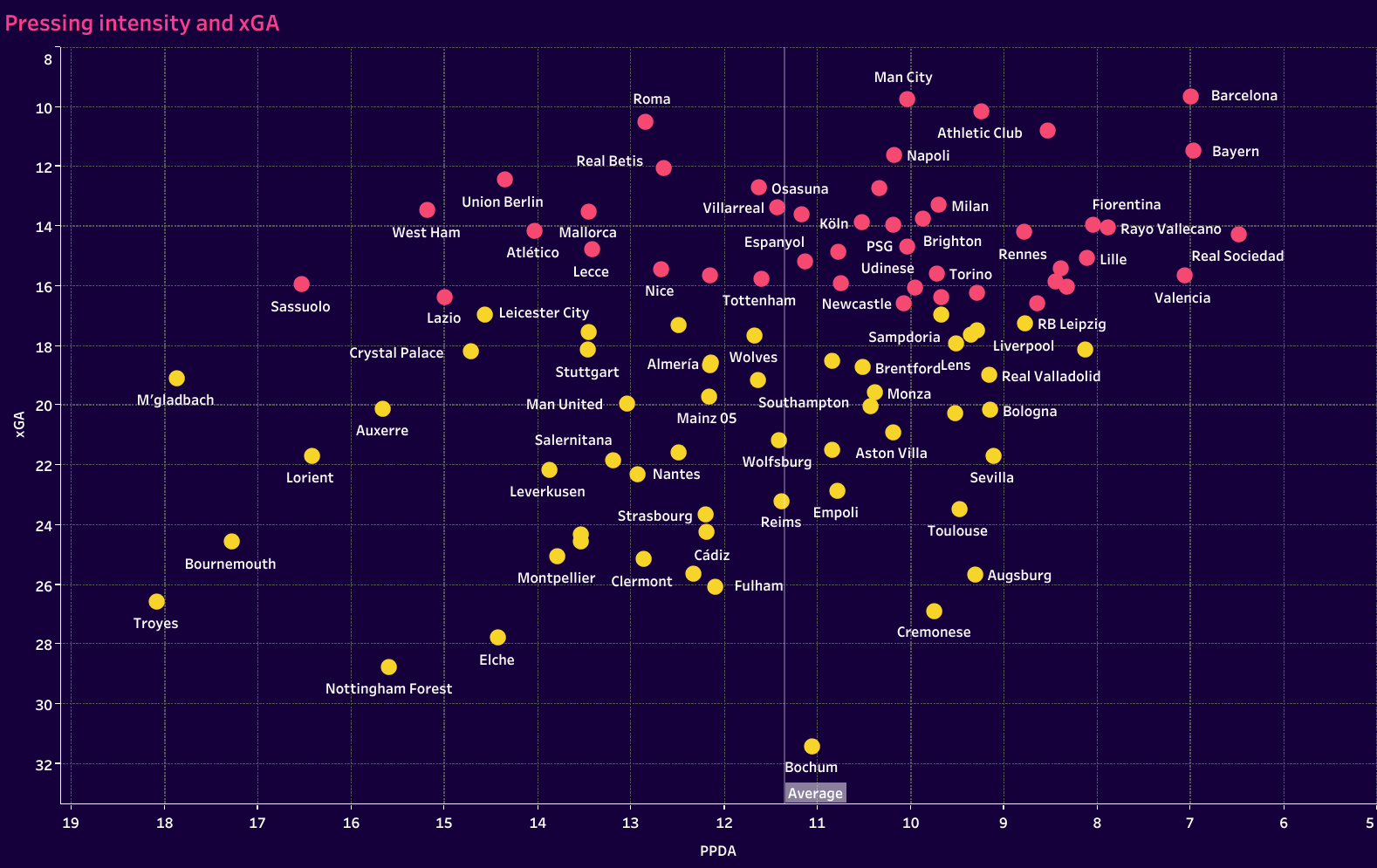

Let’s keep xGA and add in PPDA. This will give us a sense of how pressing styles translate to each club’s ability to deny goals-scoring opportunities. Again, it’s Barcelona that jumps to the most isolated position in that top right quadrant. Placement along the PPDA line isn’t necessarily important. Ultimately, the job is to keep the ball out of the back of the net. We want to identify the clubs that do it well and get a sense of what they’re pressing intensity looks like.

Spanish teams that use an aggressive counterpress have fared well this season. If you look at the top right quadrant, Barcelona, Rayo Vallecano, Real Sociedad, and Valencia have done very well in both metrics this season. Athletic Club falls closer to the mean PPDA, but they still fall in the top quarter among UEFA’s top five leagues.

The largest cluster of teams with the pink points, which represents the upper echelon of the data set, is right around a PPDA of 10. That is still slightly above the average of 11.35, but certainly not the heavy metal, aggressive counterpressing that has become synonymous with the contemporary game. Also, note the significant number of good to very good defensive teams that fall below the average PPDA. Roma and Real Betis are especially impressive, as are the German underdogs Union Berlin.

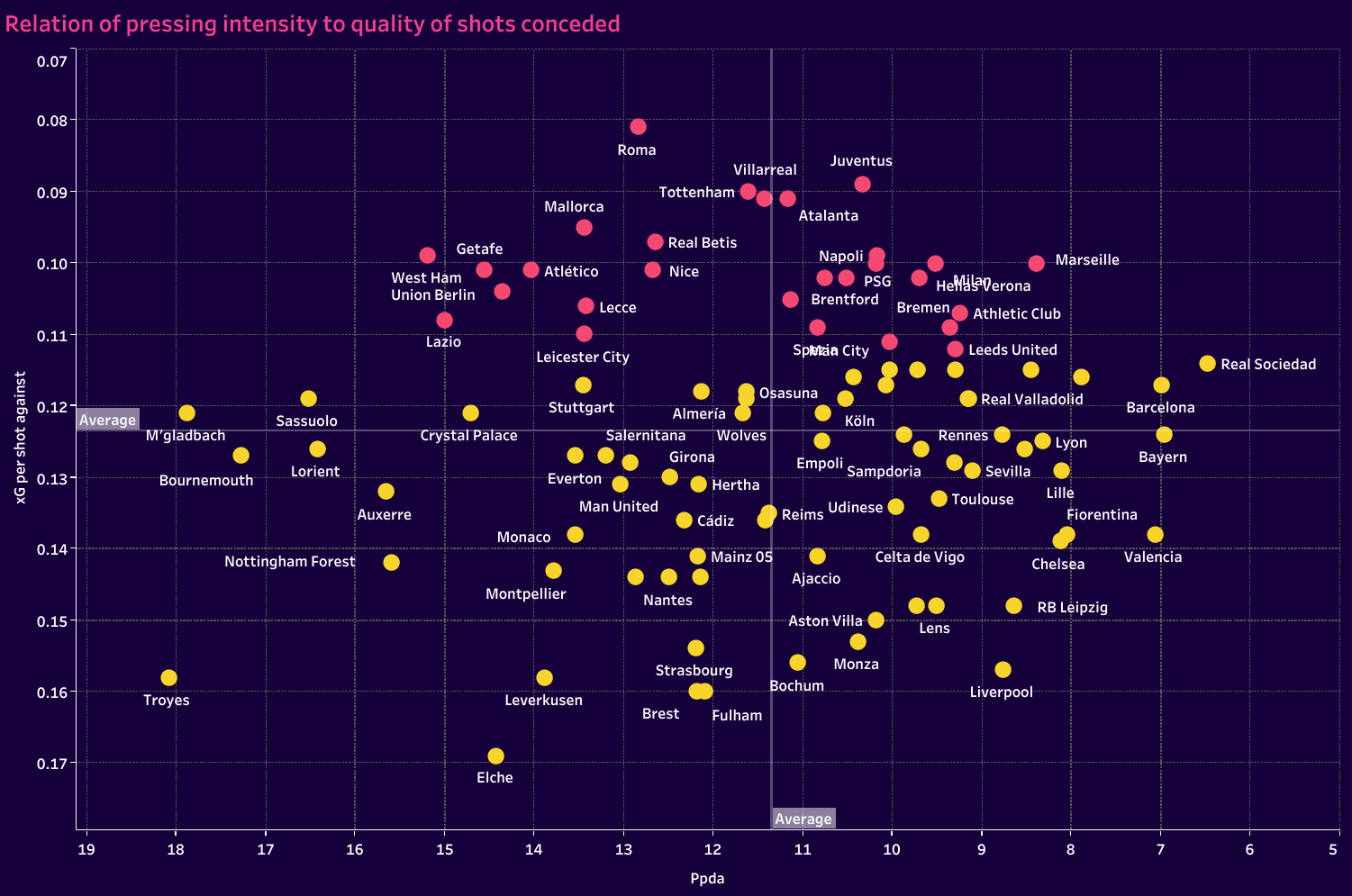

But how does that pressing intensity relate to the quality of shots conceded?

When we plot PPDA by xG per shot against, we find that teams with a lesser pressing intensity tend to allow lower-quality shooting opportunities. Very few clubs that rate highly in PPDA allow lesser-quality shots. A significant number of clubs ranging from 9 to 11 PPDA allow below-average goalscoring opportunities.

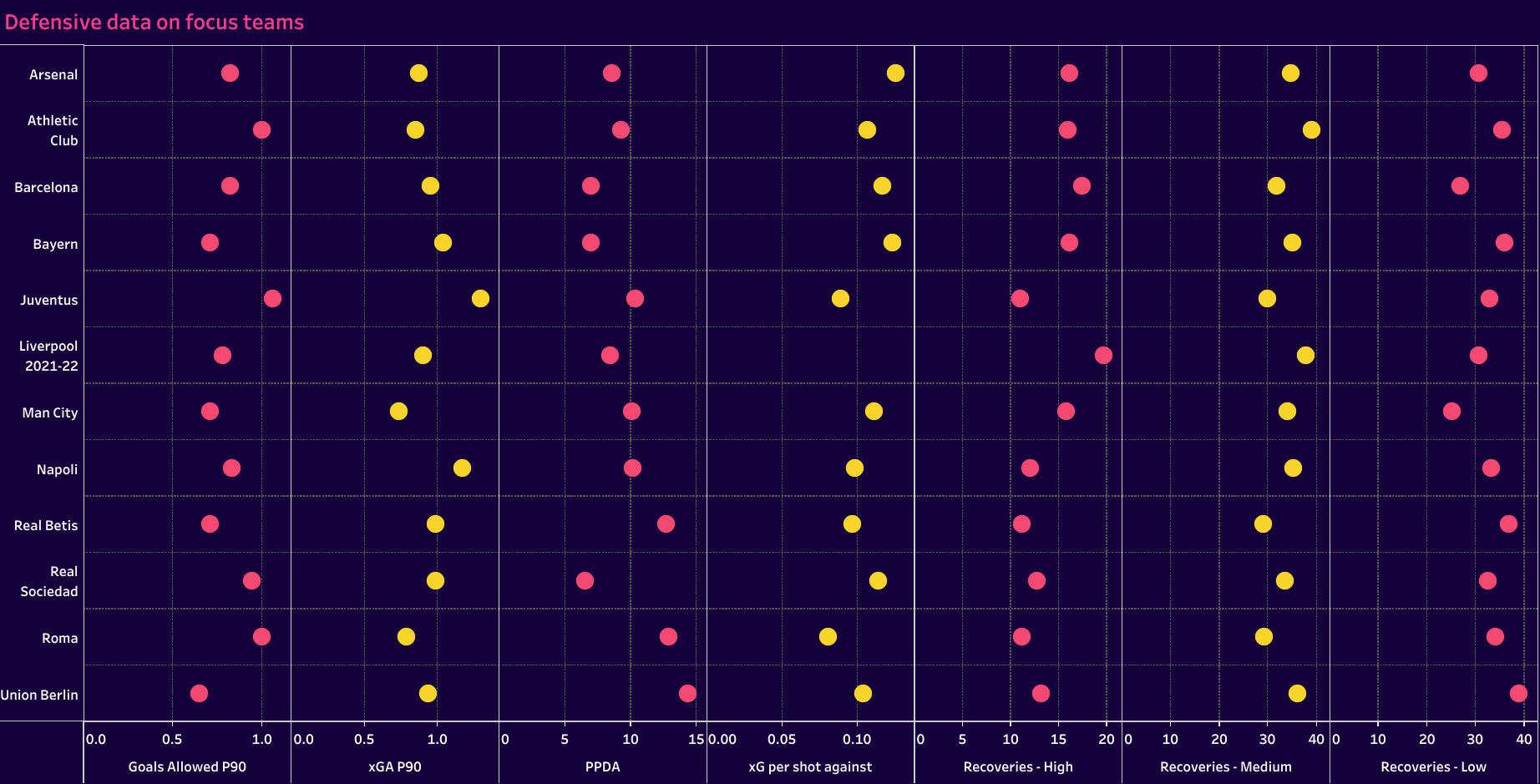

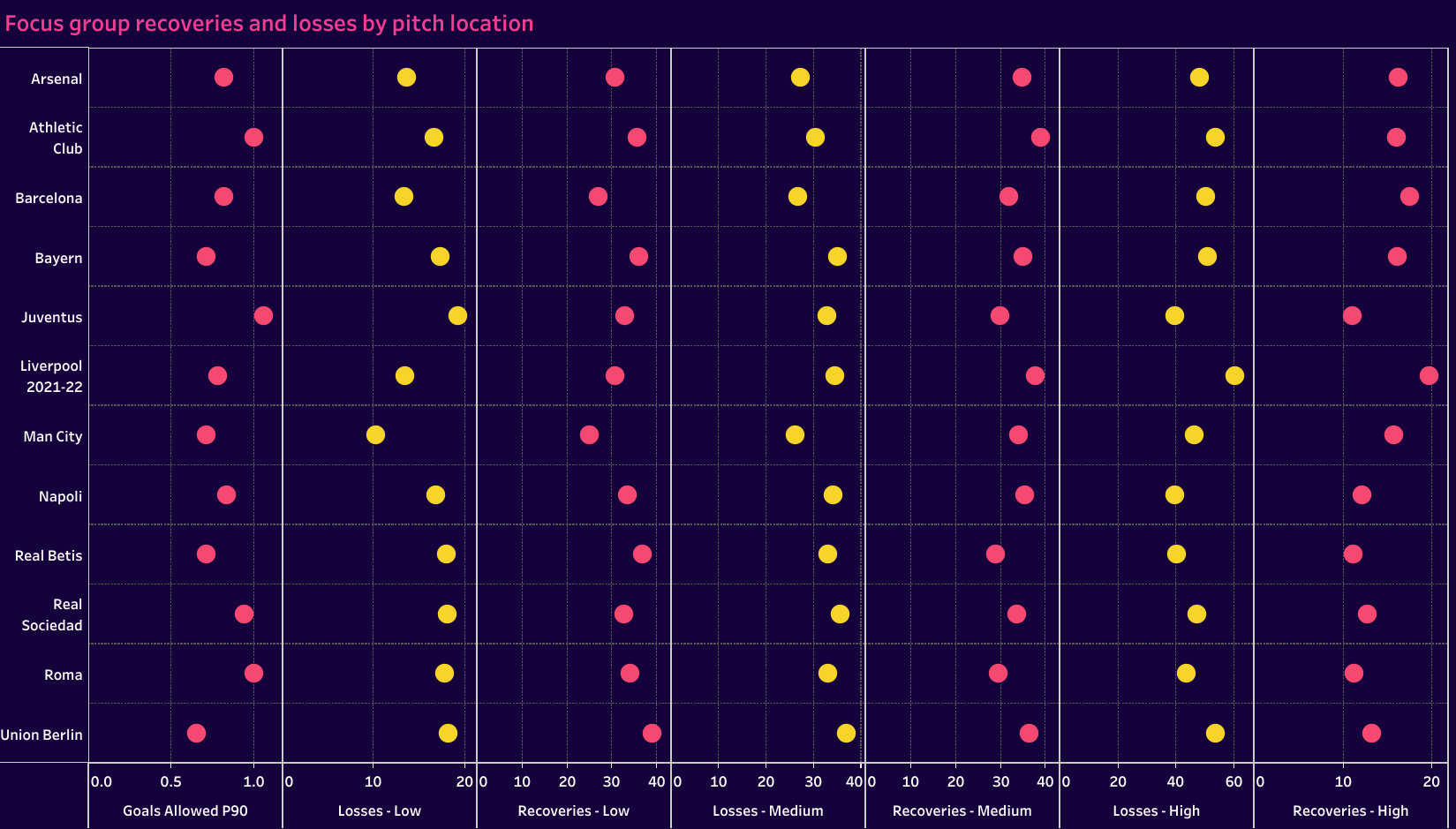

Moving beyond the first stage of the data analysis, several clubs have stood out among the group. They are represented in the final two images of this section. Their data is plotted in the four categories we have already touched upon, but the last three columns add another wrinkle. They bring two light the recovery locations for each of the teams. You will notice that we have included the 2021/22 Liverpool team in this focus group as well. Though they are struggling in 2022/23, they’re pressing was immaculate during the previous campaign. Including them in this group is more of a means of visualising the performances of clubs in 2022/23 relative to arguably the best defensive team of the previous season.

One of the interesting comparisons in the chart is to compare PPDA to the recovery locations. For example, Real Betis, Roma and Union Berlin are the three clubs with the least intense pressing schemes. That correlates to fewer high recoveries and more recoveries in their defensive third. That seems obvious, but it’s good to see the data confirm the assumption.

That allows us to look specifically at losses and recoveries in each third of the pitch, seeing the relationship between the numbers. The first column in this final chart is goals conceded P90. Oddly enough, the data points across each of the seven columns have almost an identical pattern.

Manchester City has one of the best goals-allowed P90 marks in the database and also the fewest losses and recoveries in both the defensive and middle thirds of the pitch. Their aggressive high press and counterpressing, which is tightly connected to their possession-dominant style of play, makes them one of the leaders in high recoveries and losses.

On the flip side, Union Berlin is among the leaders in low and medium losses and recoveries, then produce one of the lower totals in high recoveries. One oddity of the chart is that Union Berlin has one of the highest numbers of high losses P90. Despite their deeper defensive orientation, they are clearly having success finding their high outlets and getting forward.

If there is a lesson in the data, it’s that no one pressing system is best. It certainly can’t be taken in isolation from the remainder of the game model. Since we have examples of highly successful teams in the high, medium and low presses, we are going to look at examples from each approach, noting how the sides have structured their out-of-possession tactics to produce the success they’ve experienced this season.

High press aggressors

The high press is typically associated with possession-dominant teams. The more possession a team has, the more likely the opponents are to sit a little deeper and restrict the space available for the attacking team to exploit. Watch virtually any Manchester City game and you’ll see a combination of mid and low-blocks as opponents try to complicate City’s final third and box entries.

Looking specifically at our focus teams, five of the top 12 teams in high recoveries also rated in the top six for possession. The one exception was Athletic Club. The La Liga side averages 53% possession whereas their La Liga counterparts, Real Sociedad, rate 8th out of 12 in the high recoveries table among our focused group, yet 6th in possession percentage. Sorting those 12 teams by high recoveries P90, we’re very close to a near-perfect descending order and possession percentage as well.

The two exceptions are Manchester City and Union Berlin. The German side is an interesting case. We will address their defensive tactics in the low-block section of this article, but if you’re looking for an article on their high-pressing approach, look no further than Marcel Seifeddine’s tactical analysis. Certainly, read the article, but the gist of the matter is that Union Berlin engages in a very intense high press from dead ball situations. In open play, they will drop off, setting a midfield line of confrontation.

The rationale behind Manchester City’s middling spot in the focus group, at least in terms of high recoveries, is simply down to the fact that they lose the ball in the final third less often than those other teams. There’s no need to win the ball if you don’t lose it.

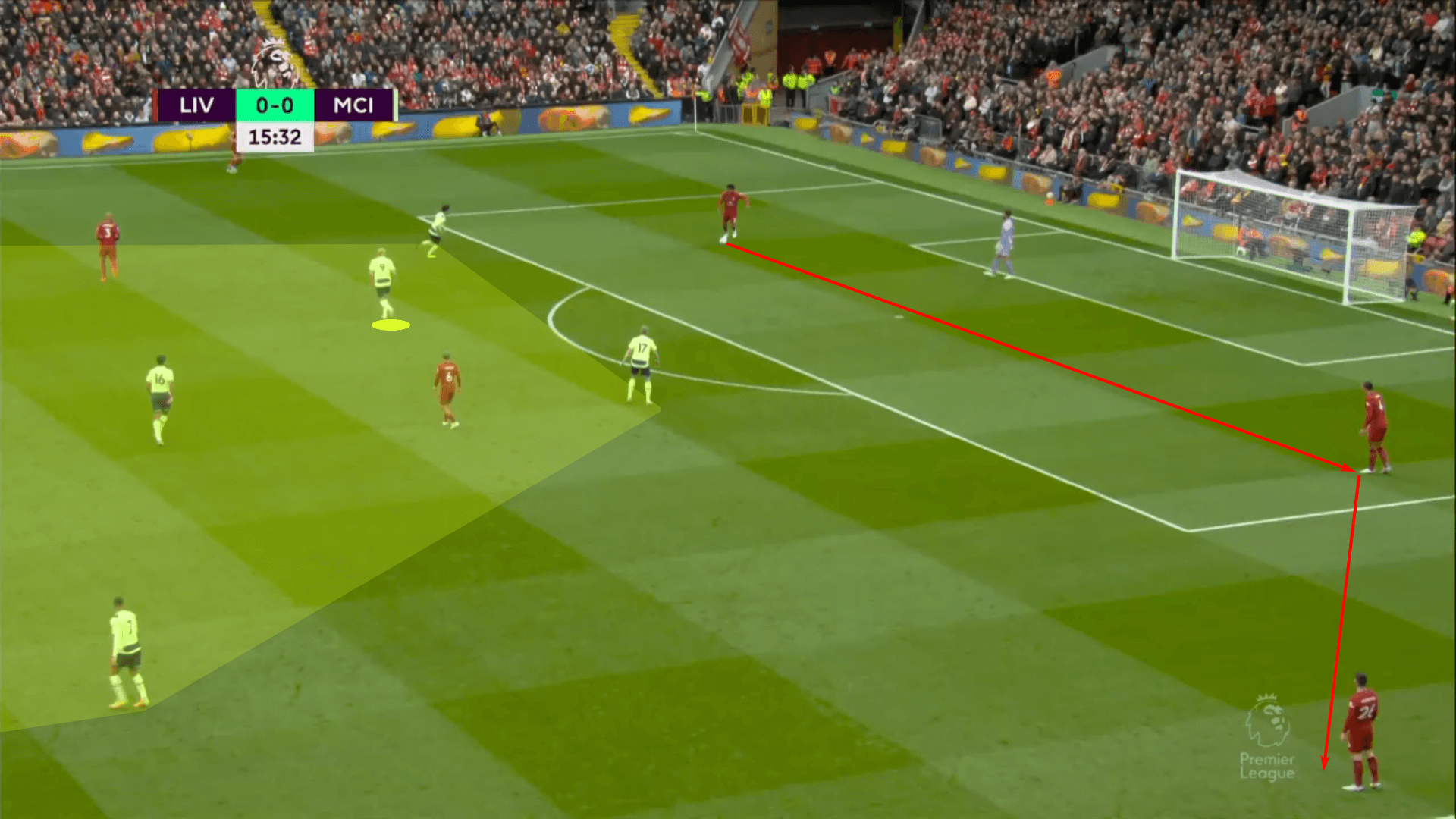

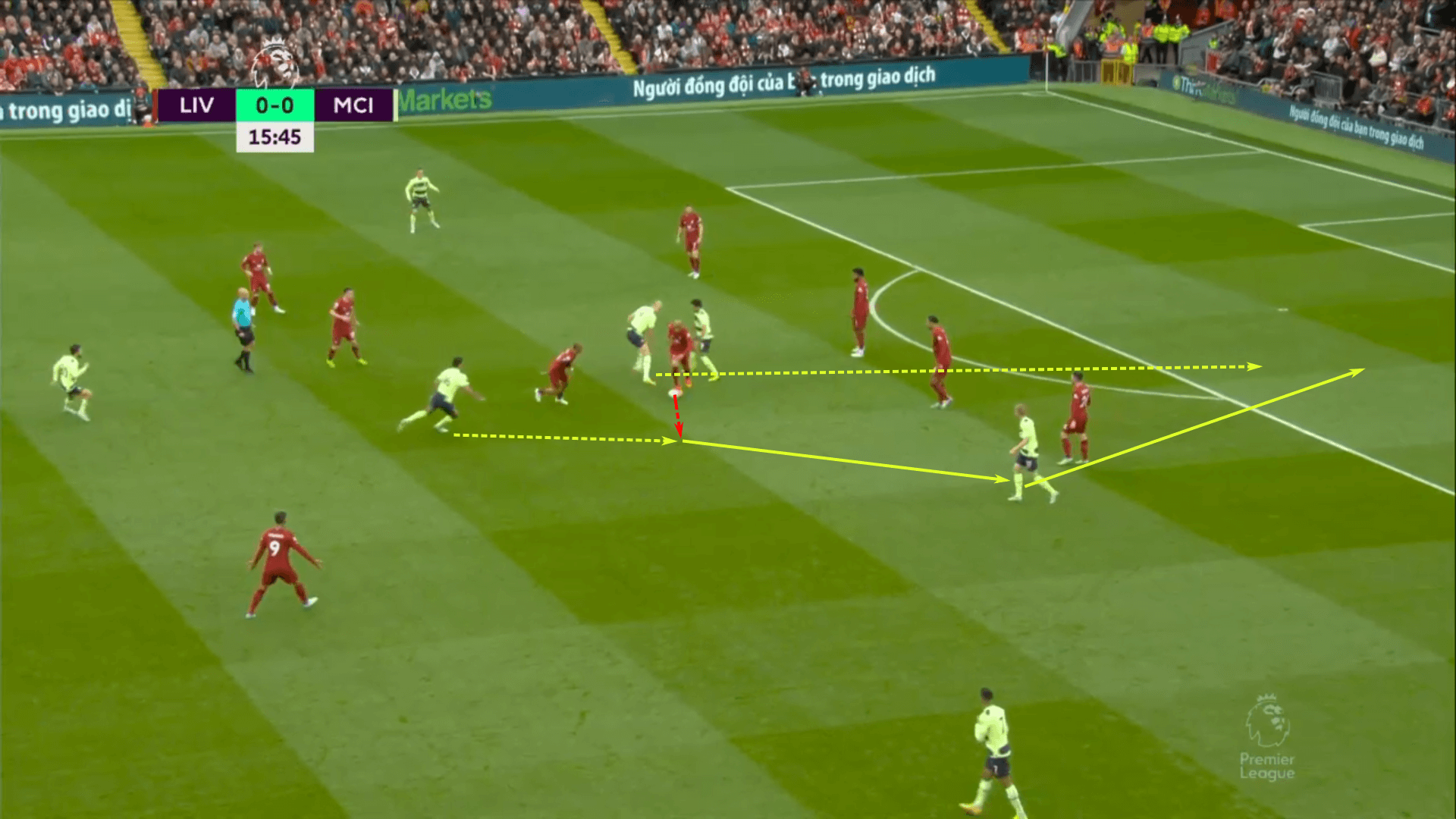

But let’s look at an example of City defending in the high press in open play. In their match against Liverpool, it was the big Norwegian, Erling Haaland, who dropped into the Liverpool midfield to offer protection against a central pass. Looking at the shaded area, we find that City is highly concentrated centrally, baiting Liverpool to play around the press.

As the ball was played into Andy Robertson on the left, City shifted their lines accordingly. Kevin De Bruyne plays a key role in the sequence, cutting off negative passes to Virgil van Dijk and Alisson. One interesting note in the sequence is that Manchester City has committed five players high up the pitch to account for Liverpool’s backline and defensive midfielder. With no short or intermediate options available, Robertson opted to play long.

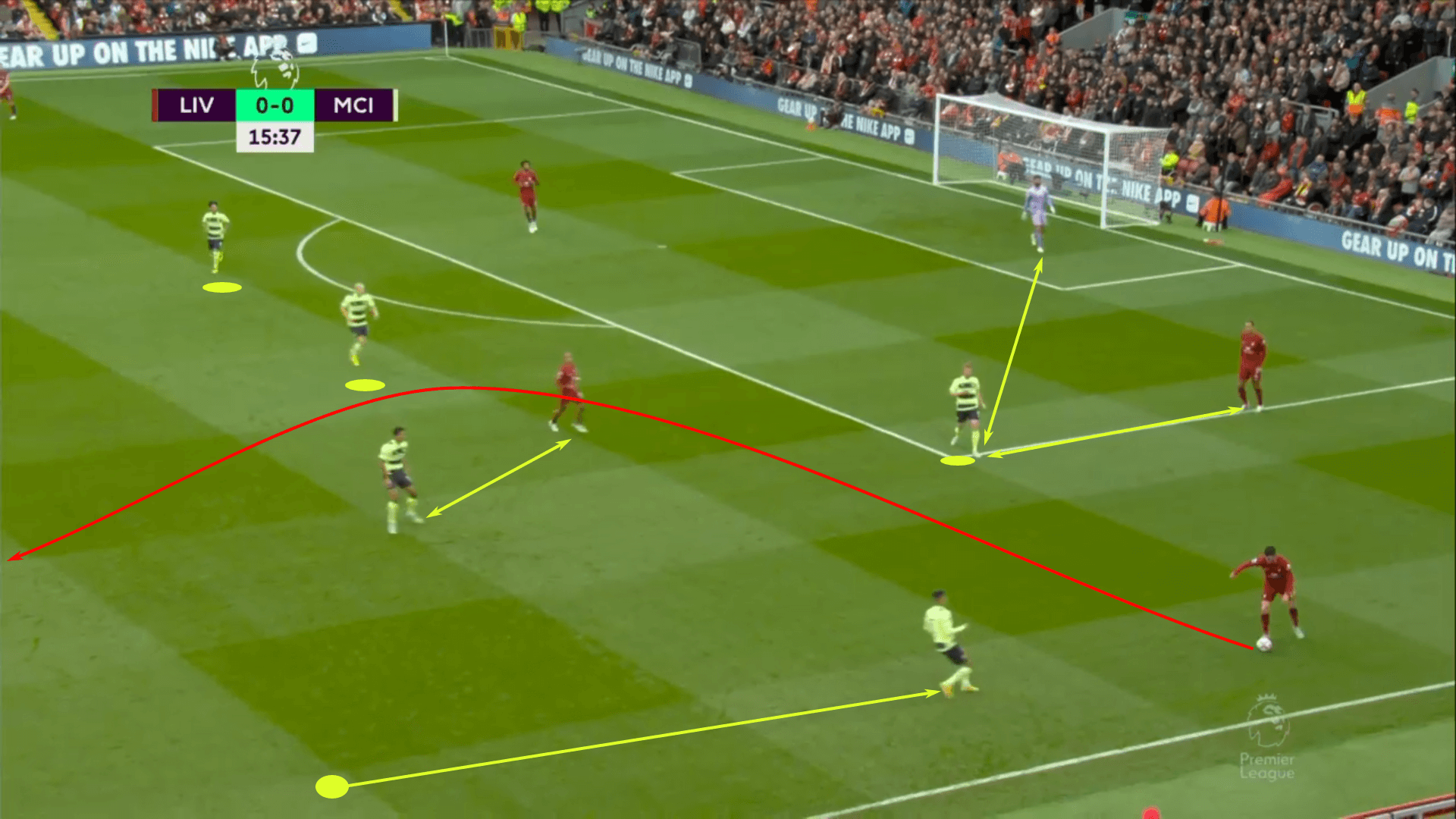

Essentially man for man near midfield, it’s imperative that City wins the first and second balls. They do so in this instance, playing the first ball into the path of Haaland. The benefit of committing so many numbers forward in the high press is that it creates a central numeric superiority for the Cityzens. The counterattack is on.

Liverpool counterpressed very well, taking the ball off Haaland. However, İlkay Gündoğan managed to recover the ball almost immediately after Haaland’s loss. He played De Bruyne, who tried to spring Haaland into the box. The weight of the pass was too strong for the Norwegian, but in the course of 10 seconds, we see Manchester City earn two recoveries, the second of which classifies as high, creating two counterattack opportunities.

Over in Spain, Pep Guardiola’s former club is experiencing comparable success, at least in league play. Barcelona is the top defending team in La Liga and is in sole possession of first place at the World Cup break. Guardiola’s student, Xavi, has incorporated much of his former teammate and coach’s philosophy. The high press has been a bright spot for Barcelona.

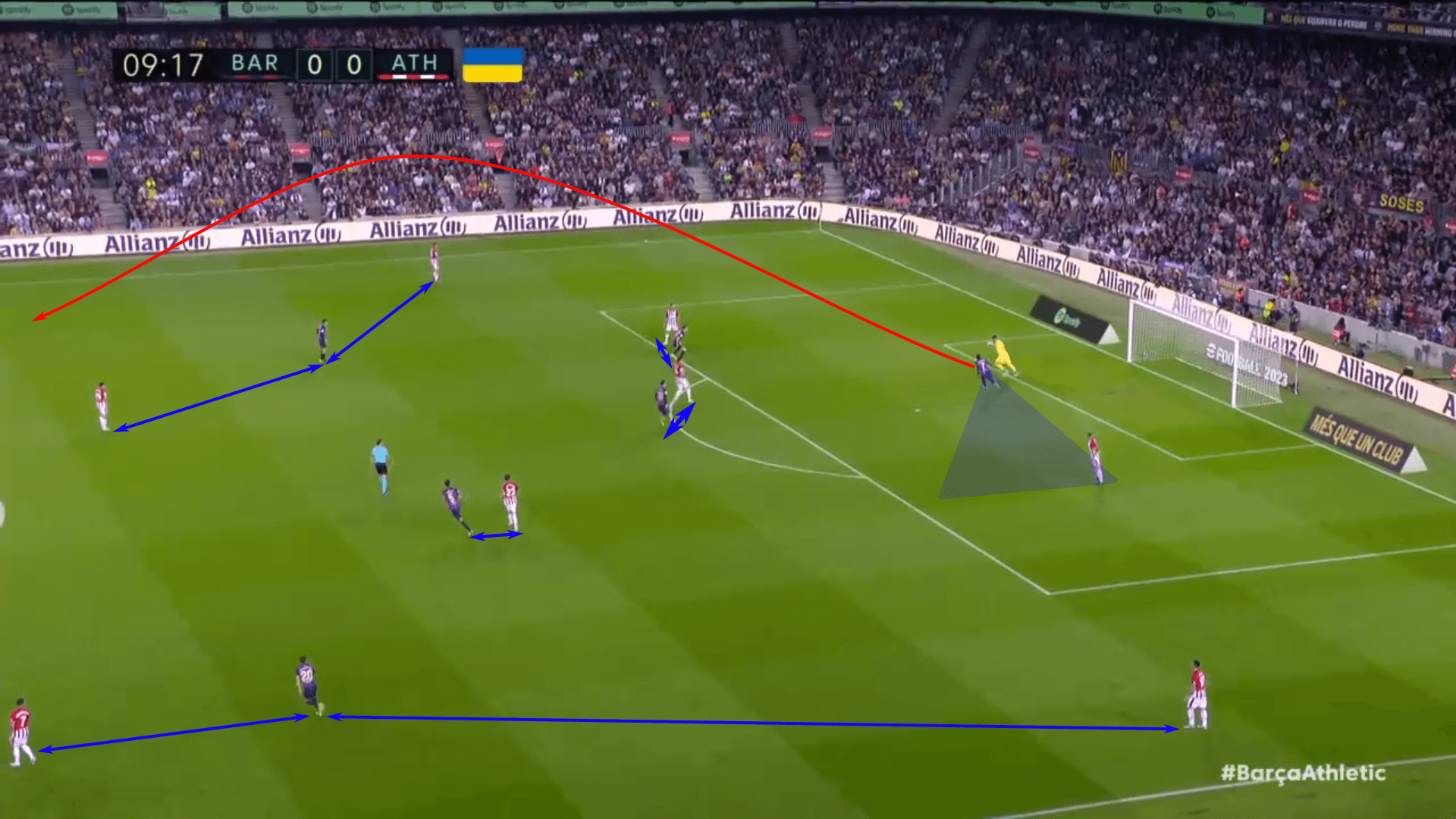

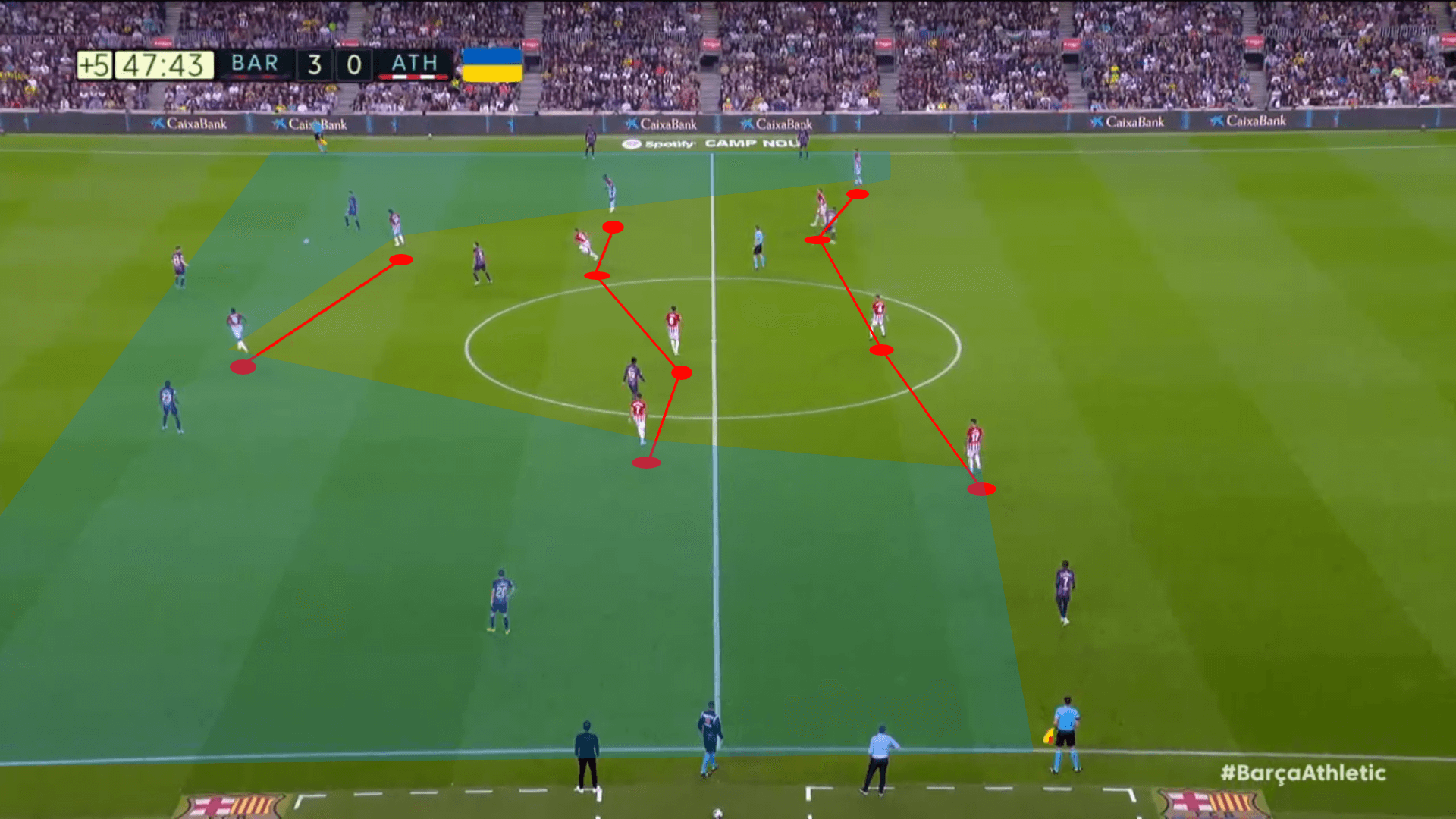

The image below shows their high press against Athletic Club. At the moment the goalkeeper was forced to play a 50/50 ball forward, we get a glimpse of the pressing structure. Short options are man-marked, as are many of the central outlets. As the ball is played to the goalkeeper’s preferred right foot, Barcelona uses their right forward, Ousmane Dembélé, to pressure the goalkeeper from his left. That pressing direction eliminated passing options to the goalkeeper’s left, making it easier for Barcelona’s deeper players to anticipate where the ball was going next. In the end, the league leaders recovered the ball and restarted their attack.

In both examples, we see the number of players the possession dominant teams have committed forward to the high press. When scenarios like these emerge from open play, the possession dominant squad typically has more numbers forward anyway, so committing to pressing in the areas of the pitch where they have more numbers makes perfect sense. But even from goal kicks and instances in which the opposition opts to restart the attack from the goalkeeper, engaging in the high press can create attacking transitions with ready-made numeric superiorities in dangerous positions.

Methodical middle-third recoveries

Middle recoveries are less straightforward than high recoveries. Whereas high recoveries are typically products of counterpressing or forcing mistakes along the opposition’s backline, middle recoveries are highly variable. They could be the result of an effective high press, as we saw with the first recovery in the Manchester City example. They could also emerge from a true mid-block or an errant pass as the opposition misplace negative passes from their final third. More of the game is spent in the middle third than either of the two ends, so it’s also just natural that more losses will take place in this area.

But rather than accounting for each variation, we’re going to look and specific examples from our focus teams. Each has its own pressing scheme, so we’ll have a nice variety of tactics to analyse.

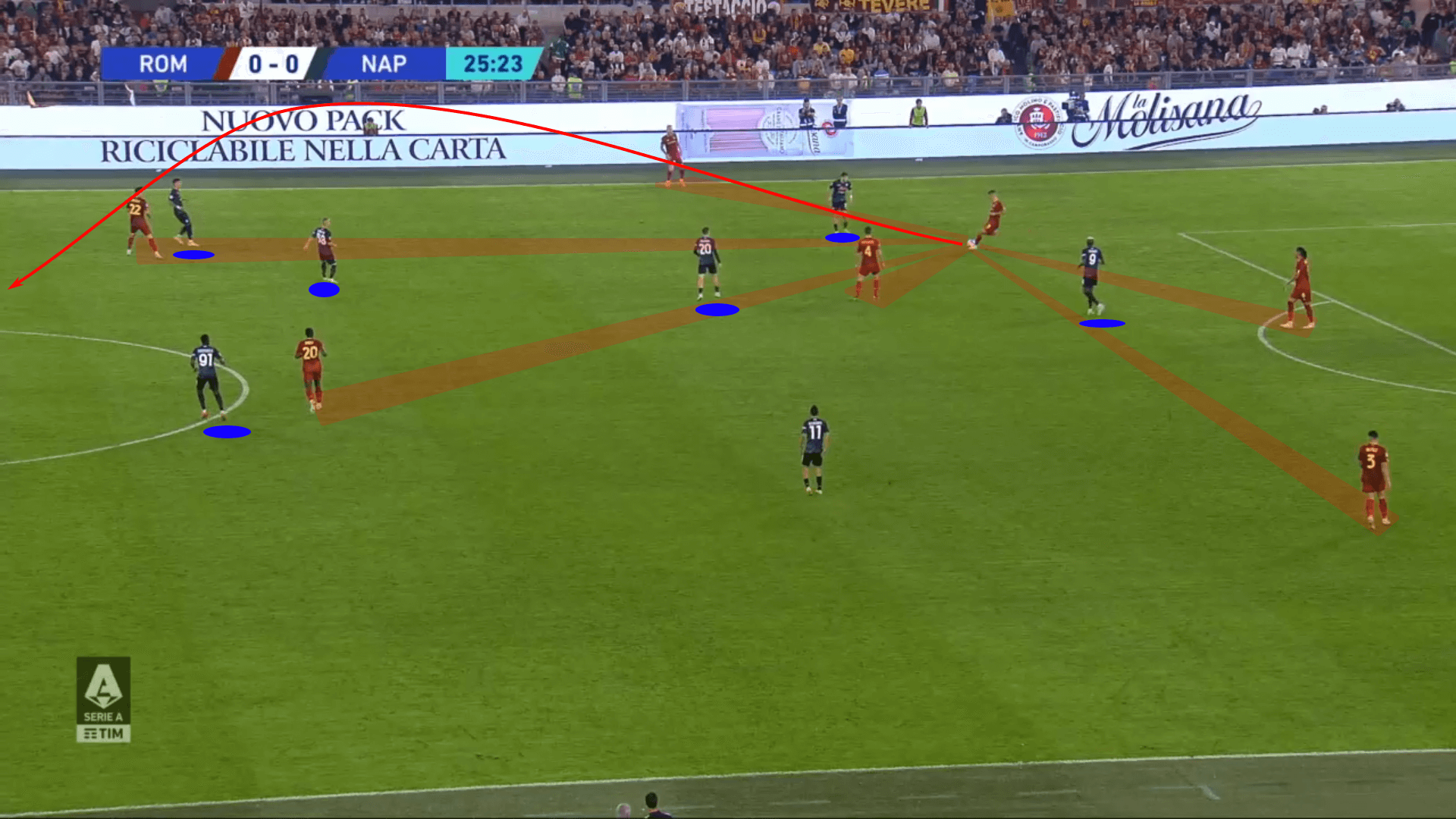

Let’s start with Napoli. During their match against Roma, it was clear that Jose Mourinho’s side would take few risks at the back. Even with their opponent’s risk-averse approach Luciano Spalletti’s Napoli was very systematic in cutting out short and intermediate passes. It was clear that if Roma was going to beat them, it was going to be through first and second balls into the forward line.

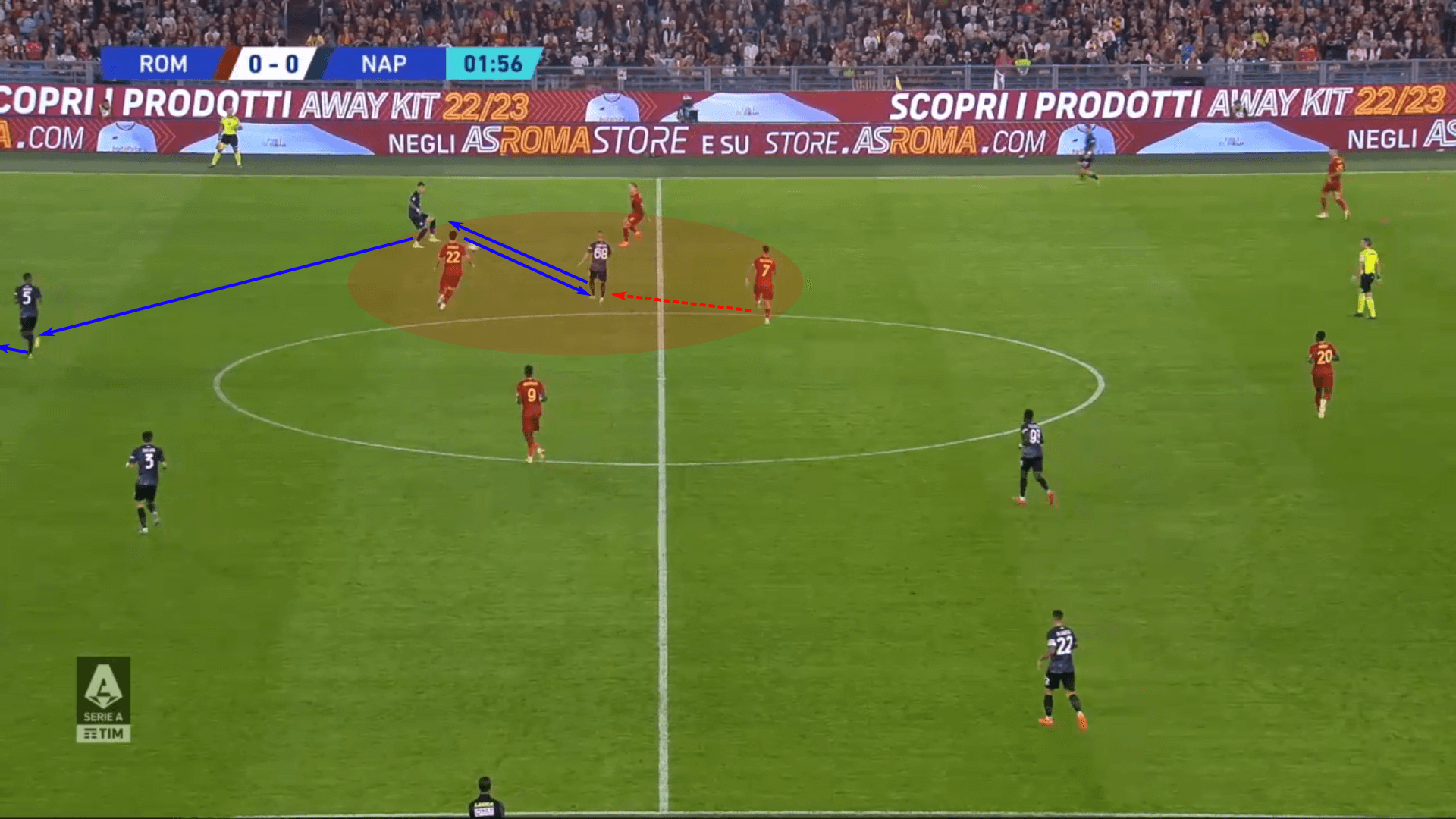

The tactical image shows the placement of the Napoli defenders, as well as the short and intermediate passing lanes available to the first attacker. “Available passing lanes” is used very loosely. There are a few options for short or intermediate passes, but even the ones available are at a very high risk of being intercepted.

Job done, at least by the high press. Much like the Manchester City example from the previous section, this sequence came down to winning the first and second balls. Making the opponent predictable through long play, especially when your team’s backline deals with those long-range passes very well, is a winning scenario for the pressing team.

In another example from that match, Napoli funnelled play into Roma’s Chris Smalling. Once he received the ball, Victor Osimhen pressured him, often leading to a lateral pass. With the next wave of pressure en route, Roma typically played long to avoid unneeded risk a the back. Those flighted passes landed right in Napoli’s numeric superiority in the mid-block.

Notice the man-marking and cutting off the left-sided passes of the right-footed first attacker. When the short and intermediate passes are taken away, as well as a side of the pitch, the defending team will typically have numeric and qualitative superiorities to deal with the long pass into the forward line.

Those two Napoli examples show how a good high press can lead to mid-recoveries. In our next example, we have Athletic Club in a true mid-block against Barcelona. While the scoreline got away from the Basque side, this was a good example of a mid-block producing a middle recovery.

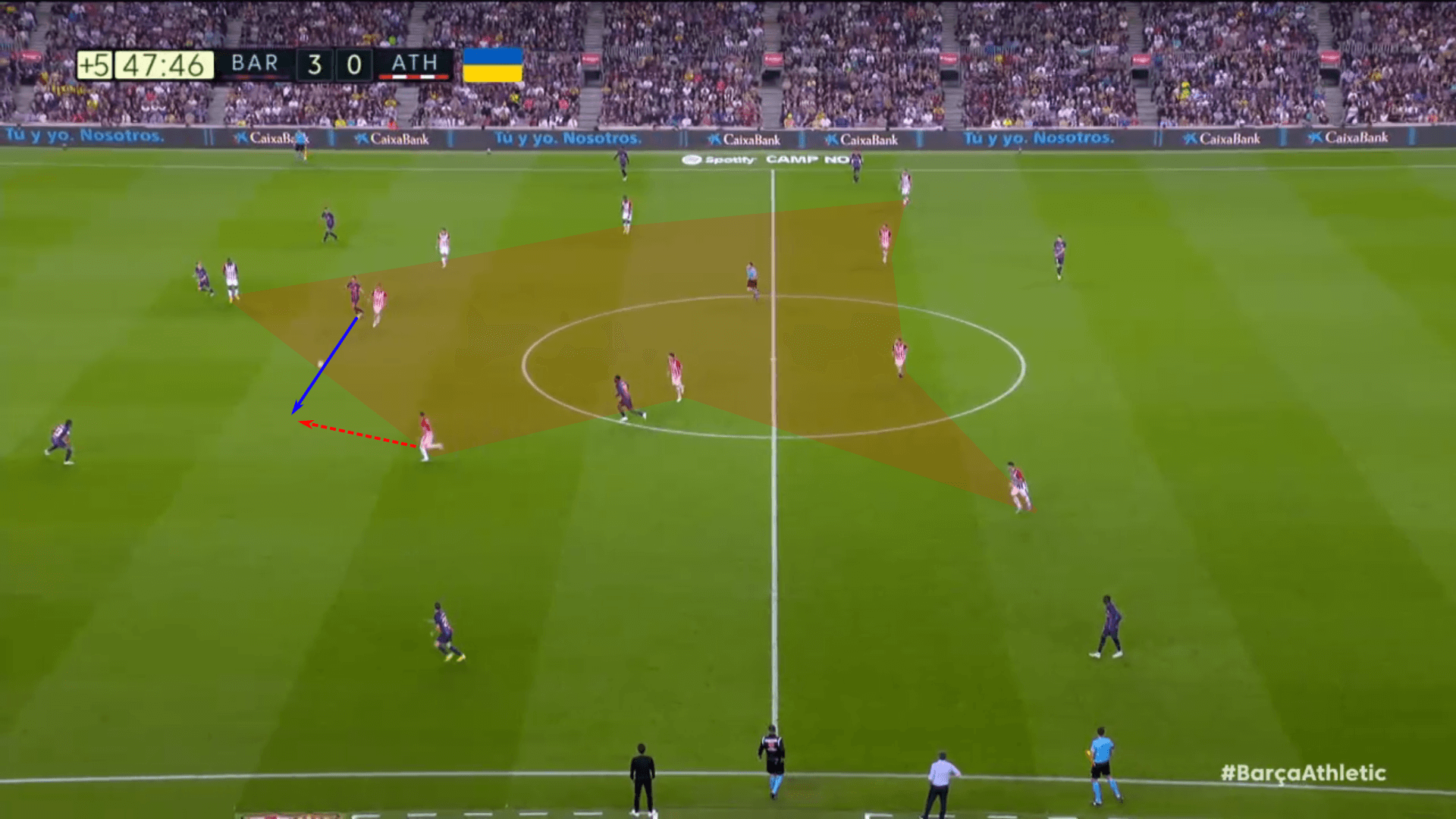

Starting with the system, we have Athletic Club in a 4-4-2 with approximately 25 m between their front and back lines in the press. They are very compact controlling the centre of the pitch while trying to funnel Barcelona into the wings.

Barcelona had an initial 3v2 advantage centrally, leading Athletic Club to push an additional midfielder forward to force numeric equality. As Barcelona combined in the central channel, poor body orientation of the checking midfielder limited his options to play outside of the press. The next pass is undoubtedly a poor one, much too far from Jules Koundé’s feet, but good pressure on the ball and the awareness to push forward and beat Koundé to the pass, leading to a mid-recovery in a dangerous spot.

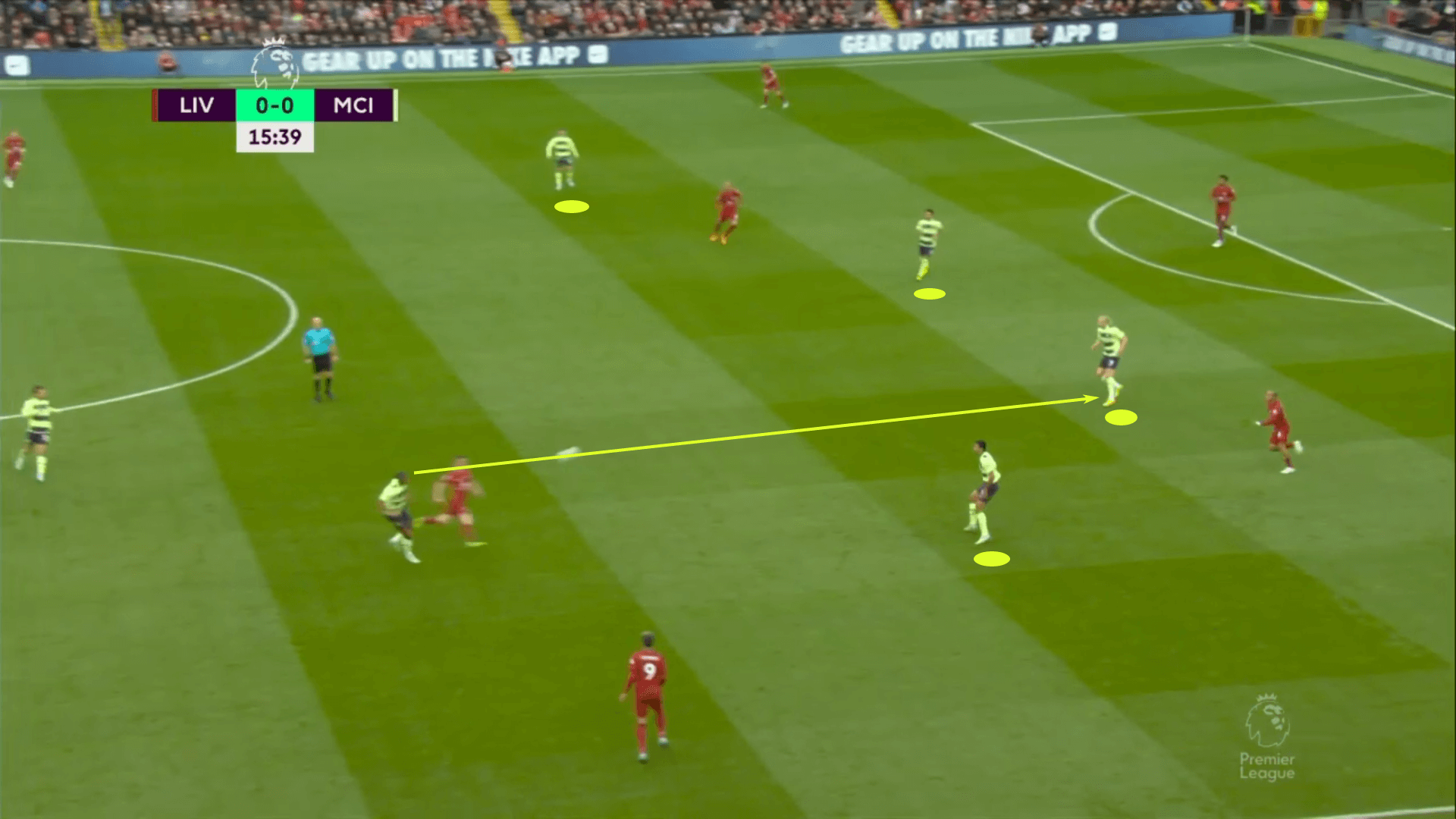

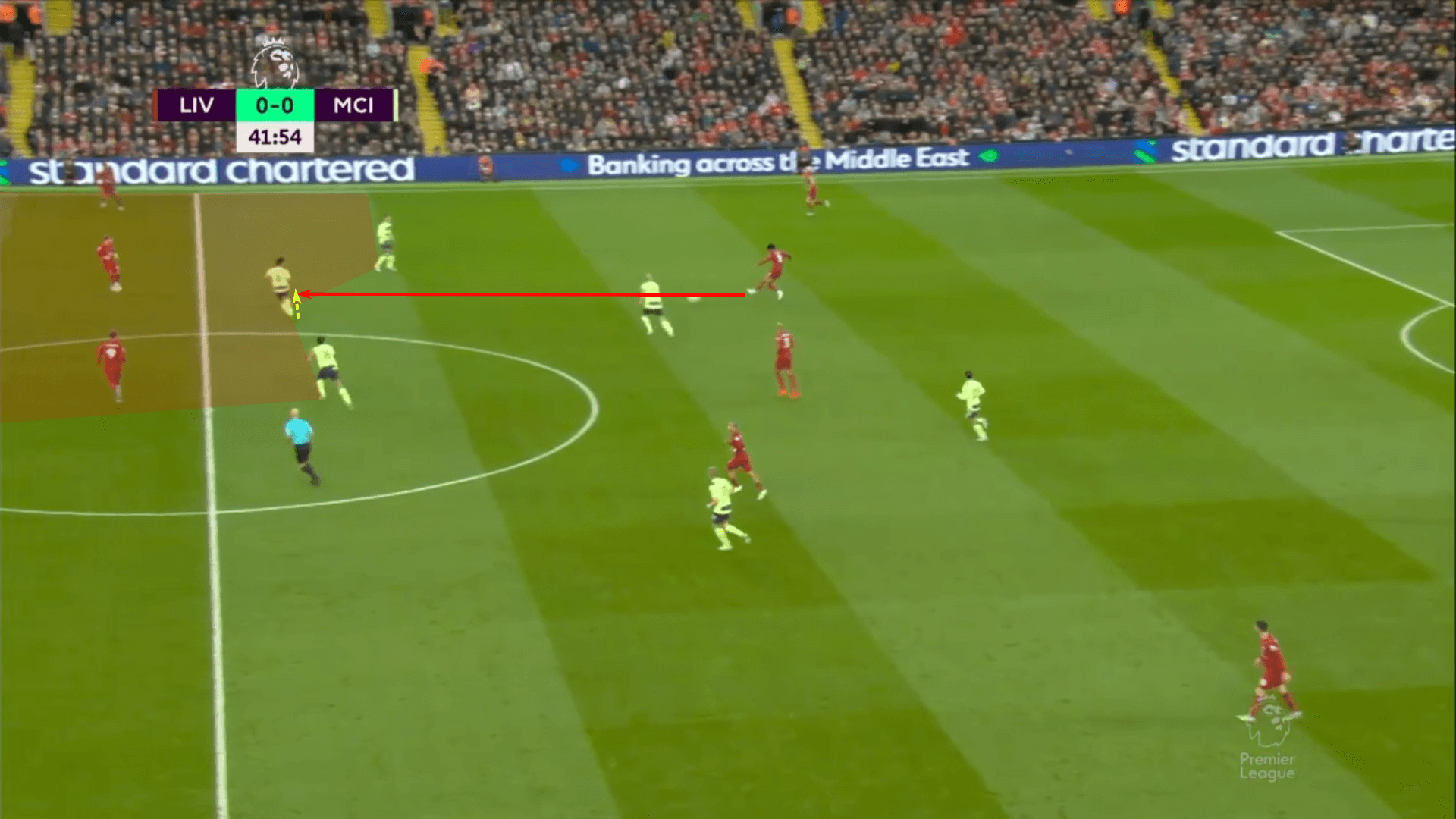

We have seen Manchester City in the high press and now we look at their mid-block. Much like the high press, many of their numbers are committed forward. City actually has more players on Liverpool’s half of the pitch than the Reds.

To some degree, this is a positive for Liverpool. They want their midfielders to get between the lines and their backline to produce line-breaking passes. This is an opportunity to bypass two lines. However, City’s compactness leaves them well-positioned to deal with those line-breaking passes. In fact, they give the appearance of baiting that specific pass. The recovery is a simple one for City, who find themselves numbers up in the attacking half of the pitch.

The mid-block is highly adaptable. Teams can funnel opponents wide, set interior pressing traps or even step their lines high enough to trigger long passes from the opposition, but with less space for the opponent to play into. With less ground to cover, the mid-block is typically easier to organise and keep numbers behind the ball than the high press. The recovery location doesn’t typically come with the same level of reward as a high recovery, but there is less risk when there is less space to defend.

Recovering the ball in the low-block

Now we move to our last area of the pitch, the defensive third. Generally speaking, low recoveries are the most difficult to convert into shots. There is simply too much ground to cover and too many variables to account for.

Though the low-block offers the lowest degree of reward, for teams that are built to defend in the low-block, that’s also the most risk-averse approach. You can’t lose if you don’t concede. If you can keep the ball out of the net and play the odds on the counterattack, you’ve got a chance in any game. That’s typically what we see from teams that excel in the low-block.

We’re going to look at two teams in this section, Union Berlin and Roma.

Union Berlin is an interesting team. We can’t encourage you enough to go back and read Marcel Seifeddine’s article that was linked to earlier in this analysis. Though the German side leads our focus group in low recoveries P90, averaging 39.06, they are a blend of staunch low-block defending and opportunistic high pressing. Union Berlin will high press from restarts, like goal kicks and throw-ins. The top priority is defending from a position of strength, namely, a highly organised and compact encounter with limited variables to account for.

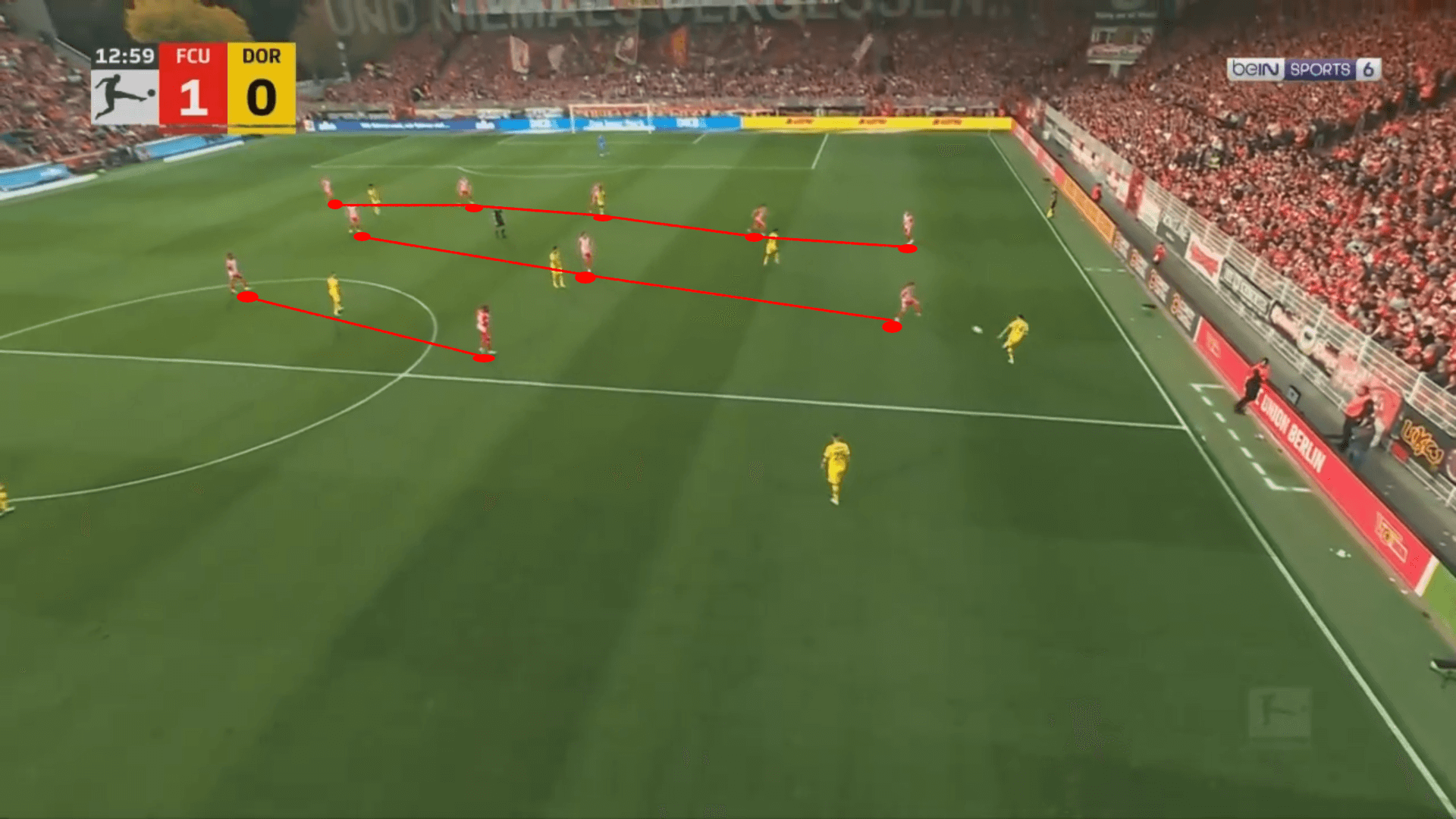

In the flow of play, they’re much more likely to drop into a mid-block with a midfield line of confrontation. One interesting note from their game against Borussia Dortmund was the positioning of the two forwards. They were typically in or near the central channel. At the vet least, they tended to play within the opposition’s two centrebacks whenever possible.

With the squad structured in a 5-3-2 out of possession and the two forwards remaining more central, there’s typically less pressure on the opposition’s backline, but also fewer options for opponents to play into. As opponents take their ground, driving Union Berlin deeper into their low block, the squad knows to immediately look for their high central outlets once they have recovered the ball.

The data for this article was collected prior to Union Berlin’s three-game slide immediately leading into the World Cup break, so there’s at least an indication that opponents are showing a better understanding of how to attack Urs Fischer’s side. That said, Union Berlin does very well to invite opponents into a more expansive attacking shape while taking away opportunities for central penetration. If they can tweak their current model to protect against some of the more recent approaches they have seen, look for them to compete for continental play once again.

We will finish with one of the most impressive low-block sides in UEFA’s top five leagues, Roma. Mourinho is known as a very pragmatic manager. His Roma side is very much of that mould.

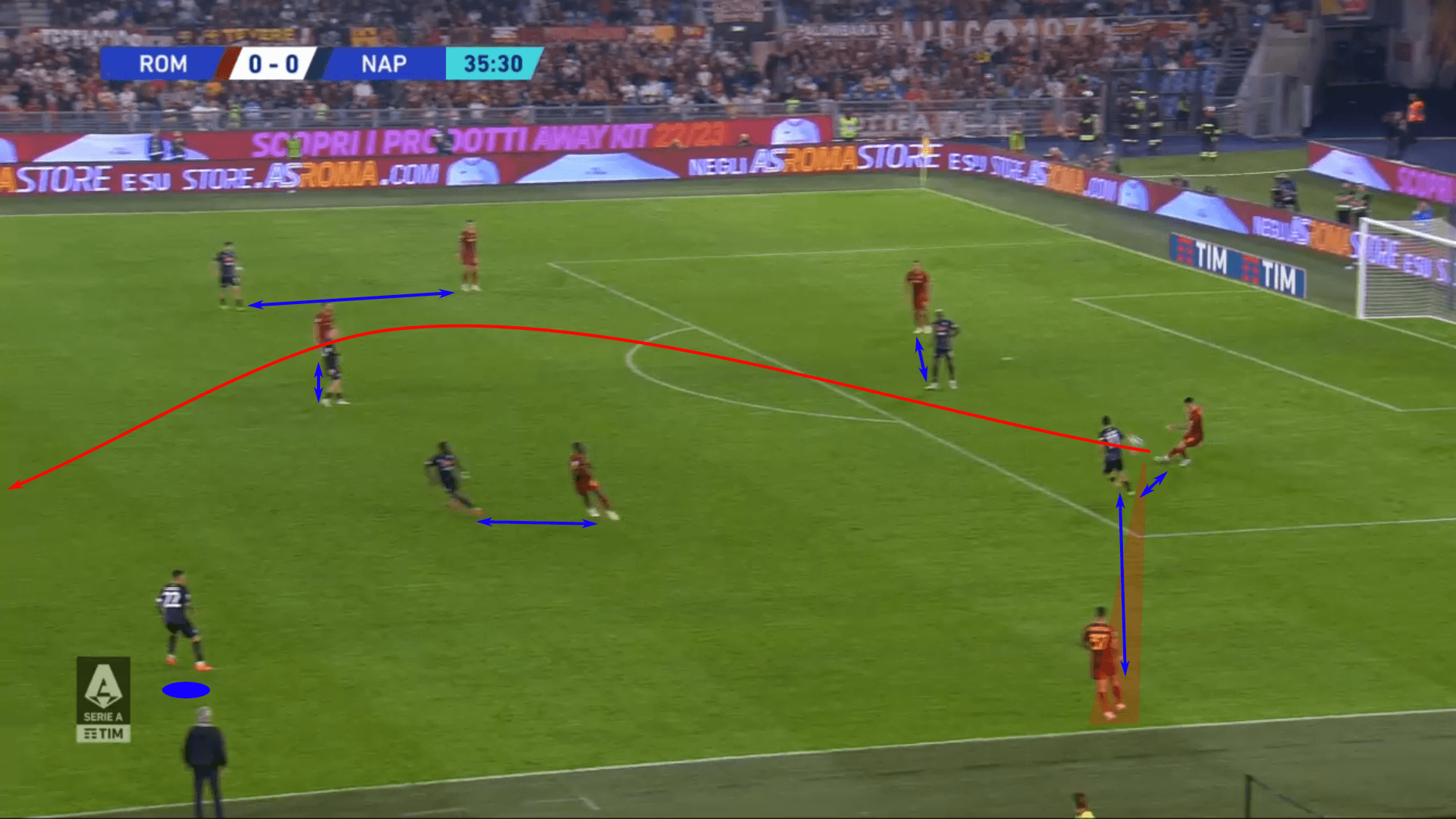

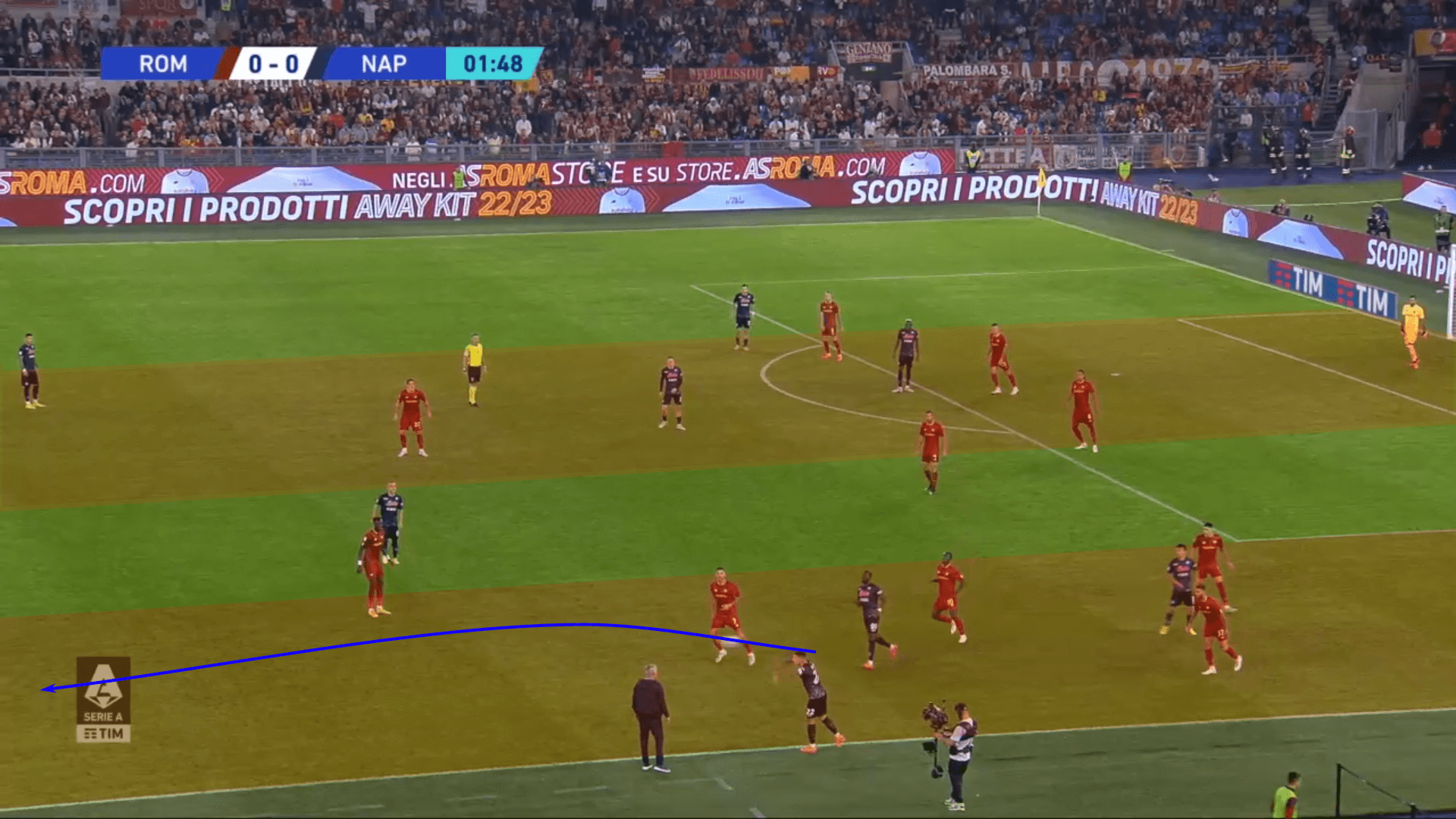

The sequence selected for this analysis starts with a low block, but really highlights Mourinho’s principles of defending. First, as Napoli looked to restart play from a throw-in, notice the placement of the Roma players. Everyone is within 40 m of the goal and the furthest player from the ball is approximately 3 m wide of the centre of the pitch. The colour shading gives an idea of three vertical channels nearest the ball. Roma is defending in each of them with half of their outfield players in the wing near the ball, two in the left half space and three centrally. Napoli doesn’t have a path forward. The only option is to throw the ball backwards.

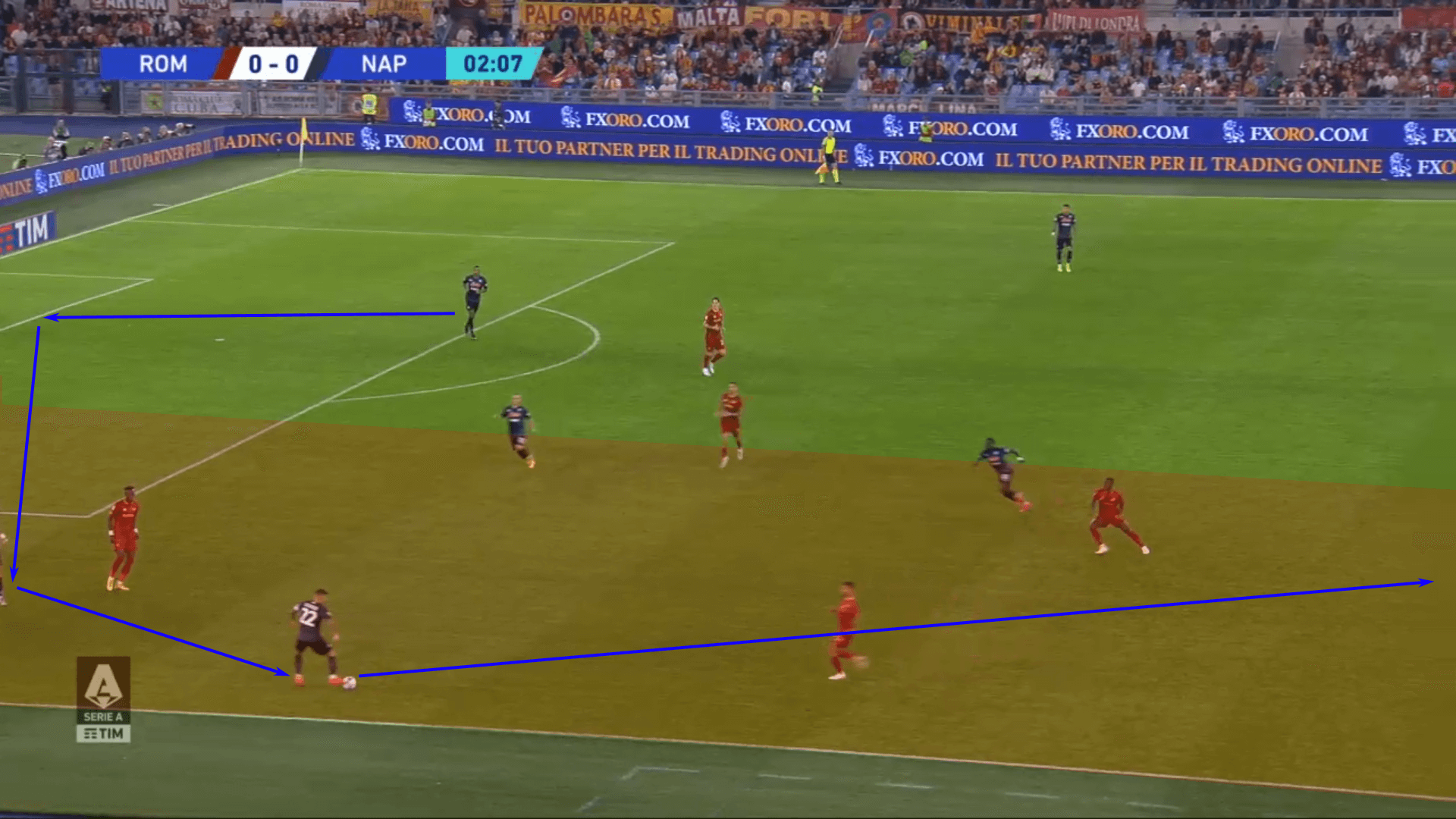

As Napoli throws the ball back and switches the point of attack, Roma has everyone behind the ball. Further, the four players who push forward to pressure the ball are tightly connected while the remaining six outfield players remain in more conservative positions. Numbers behind the ball and hunting in packs are key tenants for the Portuguese manager.

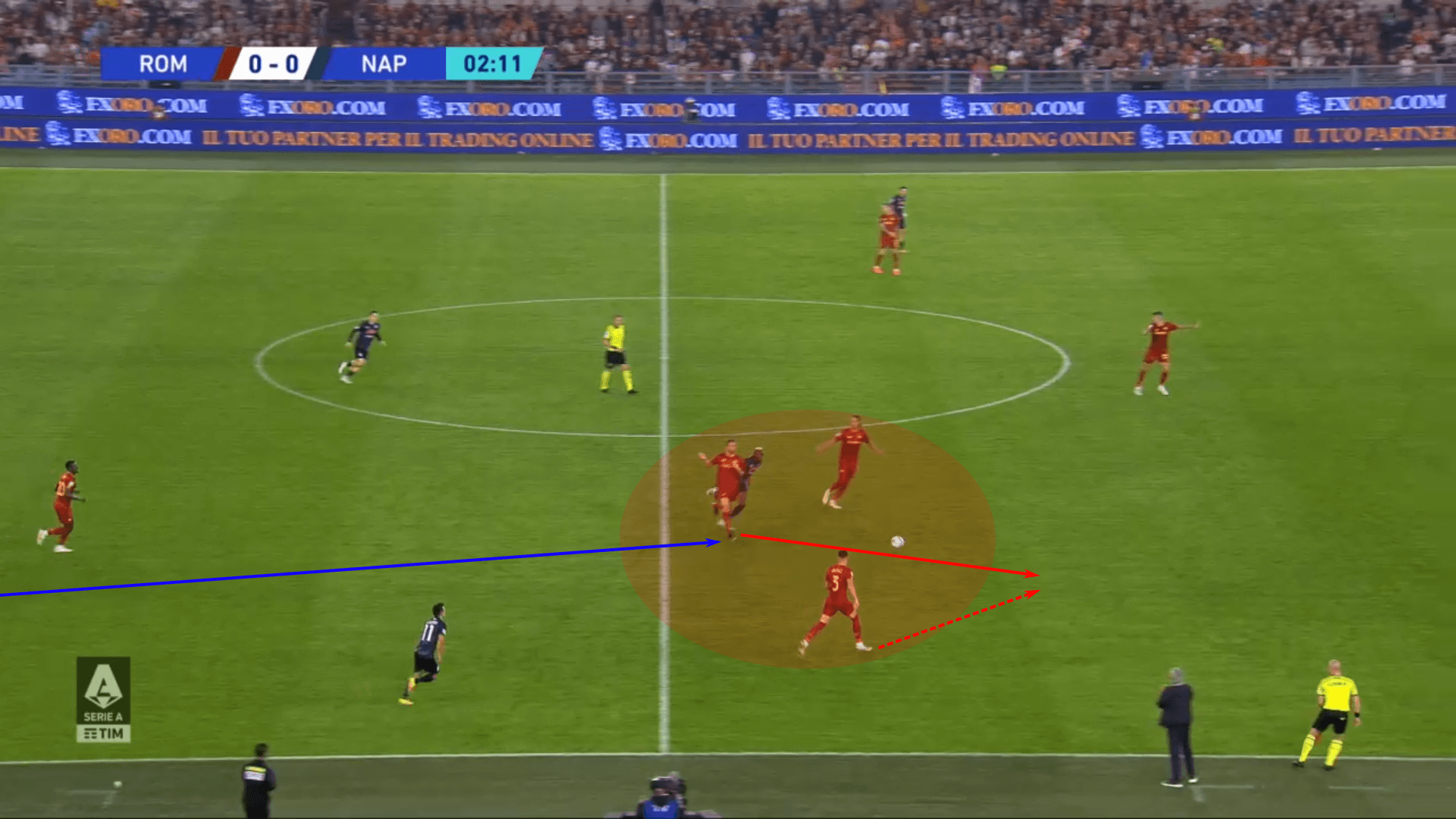

With no options to play forward, Roma progressed from an organised low-block to an opportunistic pressing scenario at midfield and push their structure high up the pitch to engage in a high press. Much like the low-block defending, Roma funnels playing to the wings and commits to numeric equality near the ball.

The result of the play is an intercepted pass near midfield leading to a Roma recovery.

We have it all in that sequence. First, a very structured and compact low-block, a high press and a middle recovery. It’s perhaps not the perfect example to showcase a recovery in a low block, but those recoveries also tend to be pretty straightforward. More defenders outnumber fewer attackers and hold an extreme positional superiority. As the fewer attacking players attempt to penetrate the low block, they try their luck at lower percentage passes or dribbling duels, leading to turnovers.

We wanted to get away from a straightforward lower recovery. Instead, the Union Berlin example showed how they’re pressing structure and lack of pressing intensity encouraged opponents to attempt low-percentage passes into their forward lines. Those are the actions that led to Union Berlin’s low recoveries.

With Roma, the low-block tactics brought Mourinho’s philosophy to the forefront. We were able to identify several tactical and structural principles that gave Roma positional superiority. With their pressing structure intact from the low block, they were simply able to drive Napoli further back while maintaining their structure. Organisation is easier to achieve in the low block with less space to defend and more numbers at your disposal, especially when the out-of-possession team commits all 10 field players behind the ball. But then, with the side highly organised and well-connected, they are in a position to take a more aggressive approach in the press. The objective is to always defend from a position of strength. As long as that advantage is maintained, the out-of-possession team can continue to ramp up their pressing intensity. That’s exactly what we saw in the Roma example.

Conclusion

Pressing is not a one size fits all kind of thing. Rather, like a good suit, it’s measured based on the user.

Managers will no doubt have their pressing preferences and typically recruit players who fit into that specific model. Ultimately, the objective is to implement a system that works given the personnel on hand and the relative quality of the opposition most commonly faced. The sign of a good pressing system is that it works, be it high up the pitch, in a mid-block or parking the bus.

This data and tactical analysis offers a sampling of the tactics and principles of play clubs implement while pressing in each third of the pitch. The diversity of our focus group showed us there’s no one way to press. The best way is whatever works best for a given squad.

Comments