Debreceni VSC are hoping to build on a strong campaign from last season, which saw them climb to 3rd in the Hungarian NB I, reaching the Europa Conference League qualification phase. Since Srđan Blagojević arrived at the club, the team has found its spot at the top end of Hungarian football again after several seasons in the mid-table positions and a fall into the second tier of Hungarian football.

Debreceni have definitely flown under the radar from a set-piece point of view. Seventeen games into the league season, they are yet to score a set-piece goal from the first contact. One goal directly from a free kick and two from the second phase where a ball had been cleared away from the box before finding its way into the back of the net, show that this side hasn’t been extremely successful from set plays. However, Debreceni are one of the strongest set-piece sides in the world in terms of their creativity from a coaching perspective. They do not have access to the same quality as some of Europe’s best set-play sides in terms of aerial ability and the ability to finish chances. Still, from a tactical lens, this side is stronger than 99% of the sides competing around the world.

These set-pieces are spearheaded by Balázs Dzsudzsák’s deliveries into the penalty area. The Hungarian veteran is back at his hometown club after a tremendous career during which he became Hungary’s most-capped player of all time, as well as making a strong impression in Dutch football, helping PSV to win the Eredivisie title, making 16 assists in the title-winning season.

In this tactical analysis, we will look into the tactics behind Debreceni VSC’s offensive set-pieces, with an in-depth analysis of the different variations of corners used, with a focus on their use of screens. This set-piece analysis will also introduce the concept of screens being used for screen-setters who are marked, and some advice that can be used to increase efficiency in the future.

Different Uses of Screens

Debreceni has impressed me through their varied use of screens, but what is crucial to the execution of each screen is the positioning of the ball attacker and the screen setter. For the screen to be as effective as possible, the defending team needs to be in the dark for as long as possible. This means it should be hard to predict who the intended target is and who the person setting the screen will be. If it is obvious one player is about to set a screen, the defending team may leave them alone and use that player’s marker to double up on another player, who could be the intended target, or defend a different zone.

The V attacking shape gives Debreceni the most possible ‘attackers’ and screen setters. As seen in the example below, there are two primary zones that Debreceni aim to attack: the front and back edge of the six-yard box. The player at the bottom of the V can, whilst the players on the top of either side, are almost surely going to be setting players in the middle of both sides, giving this structure its fluidity.

The player in the middle of the three on the right side of the V has two options. He is either going to attack the ball, using the player on the top as his screen, or the player in the middle will set a screen for the player at the bottom of the V. This fluidity gives Debreceni three main attackers who are able to access either the near or far side, from a central starting position, without giving the defending side any hints as to which side will be attacked, stretching the defenders thin with so many areas to protect, as well as having to focus on their 1v1 duels.

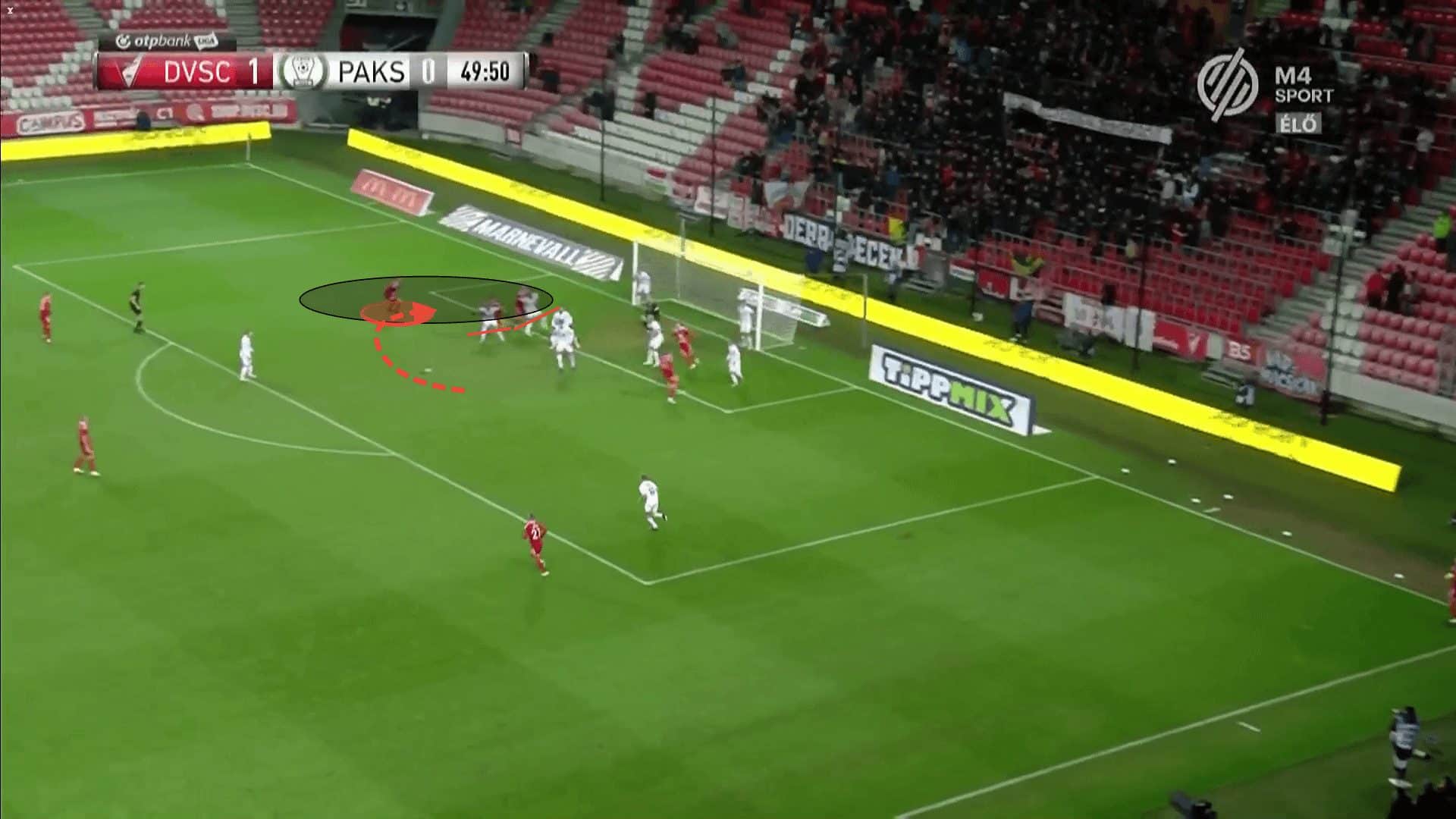

One of the more simple yet effective routines is pictured below. Screens are used on the two or three nearest zonal defenders to the target area, which is at the near edge of the six-yard box. This ensures that the ball will definitely reach the target area. In the attacking unit positioned slightly deeper, there is a 3v3 situation where players are tightly marked. The deep positioning of the attackers is important in allowing the attacker to have somewhere to escape if he does eventually gain separation from his marker. An additional screen is used inside this mini 3v3 battle to give one player the time and space to attack the ball unopposed.

In the attacking unit, which is tightly marked, it can be hard to see exactly what is going on and how defenders lose track of their markers. This close-up image below shows how only two players are needed to create separation for an attacker to move into the target area.

The image below shows number 14, who is the screen-setter, and number 94, with the role of the space attacker. As the space attacker begins his run toward the target area, the screen-setter drives a wedge in between the space attacker and his marker.

This forces the defender to give his player a yard of space, as any holding or pulling of the short will concede a penalty. It is physically impossible for the marker to run through the player, so he must give up a yard of space, giving his marker the separation he is after. An important note for the setting of the screen is to use a wide base, increasing the player’s ability to stay balanced and withstand any contact, reducing the chance of him being moved out of the way by being outmuscled.

Similarly to when they attack the near post when attacking the back post, screens are used on the nearest zonal defenders to the target area. We can see two screens used, preventing the zonal defenders from accessing the target area, whilst the attacker never had a marker in the first place so he could move into the path of the ball without any disturbance. Especially with crosses to the back side of the six-yard box, it is vital that the cross is fast-paced to prevent the goalkeeper from having enough time to readjust and claim the ball.

Against man-marking systems, it is fairly simple to manipulate the position of every defender in the box. With that being said, Debreceni can choose where they want each defender and choose which space they want to attack by moving every attacker away from it. We can see in the example below that every attacker moves up high toward the goal, which creates space around the penalty spot. From there, every player sets a screen to allow the ball to access the target area easily, with no defender being able to step up out of the six-yard box. Like before, a screen is set so that the space attacker can make his run undisturbed, where he is then able to take a shot at the goal from the penalty spot.

A slight variation of this routine is moving the attacking unit slightly away from the six-yard box deliberately to create space inside the six-yard box for an arrival at the back post for the second contact. Shooting at goal from a run from the back side of the penalty area isn’t the simplest skill, so to simplify the execution for the attackers, they have the safety at the back post for a tap-in if the shot isn’t met with precise contact.

In other instances, against heavy zonal blocks, attackers already have the space and separation from defenders. The defending side is dominating the six-yard box numerically, but we can see a 4v2 for the attacking unit in the deeper part of the box. A goal can be scored from anywhere, and although slightly trickier, the shot from twelve yards away rather than six isn’t a massive step up.

To create space for their teammates, two of the attackers selflessly set screens on the only two defenders outside of the six-yard box. Although outnumbered, the two players inside the six-yard box also set useful screens on central zonal defenders. This leaves the deeper two attackers to roam the penalty area freely. They already have the space to receive the ball around the penalty spot, but the added screens on the zonal defenders mean they have an easy, direct path into the six-yard box. This means that wherever the ball is crossed into, as long as it clears the nearest zonal defenders, it should be won by a red shirt, as they have the advantage in the aerial duel.

Screens for Screen-Setters

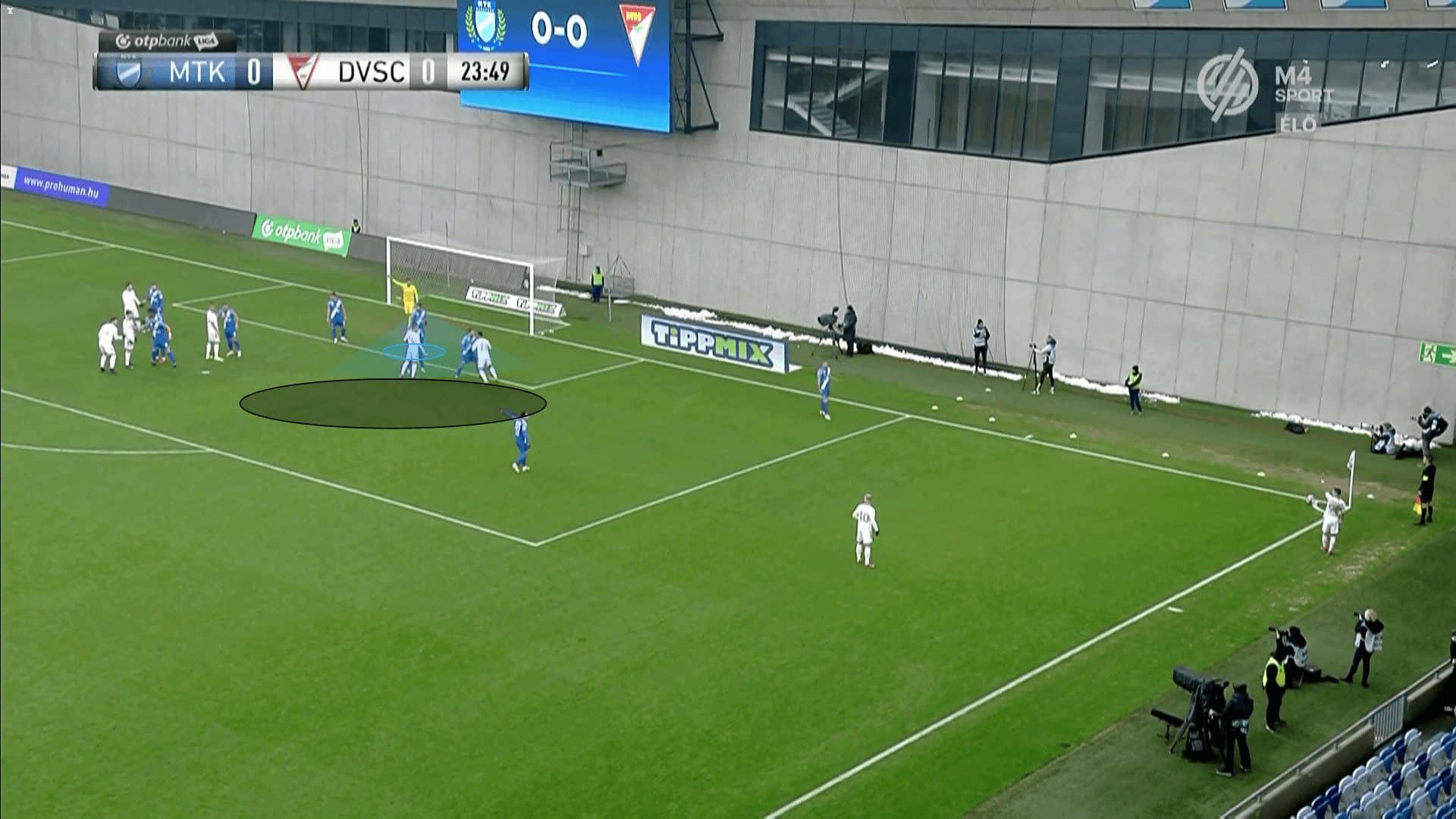

This subsequent use of screens hasn’t been seen before in football but shows the wisdom of screens that could only be found in American football or basketball. Debreceni intend to attack the space at the near edge of the six-yard box, but a zonal defender is positioned to intercept the delivery. Two attackers are ready to set a screen on him, but their markers are expecting the screens and doing all they can to stop them from being set on the zonal defender. To overcome this problem, Debreceni have started to set screens not only on the man markers of space attackers but also setting screens on the markers of screen-setters.

The player on the right of the two white shirts is supposed to screen the zonal defender but is being marked tightly. In order for him to be able to reach the zonal defender, his teammate (left of the two) sets a screen on his marker, pictured below. This gives the original screen-setter the separation needed to lose his marker and set the screen on the zonal defender. Hopefully, this hasn’t gotten too confusing!

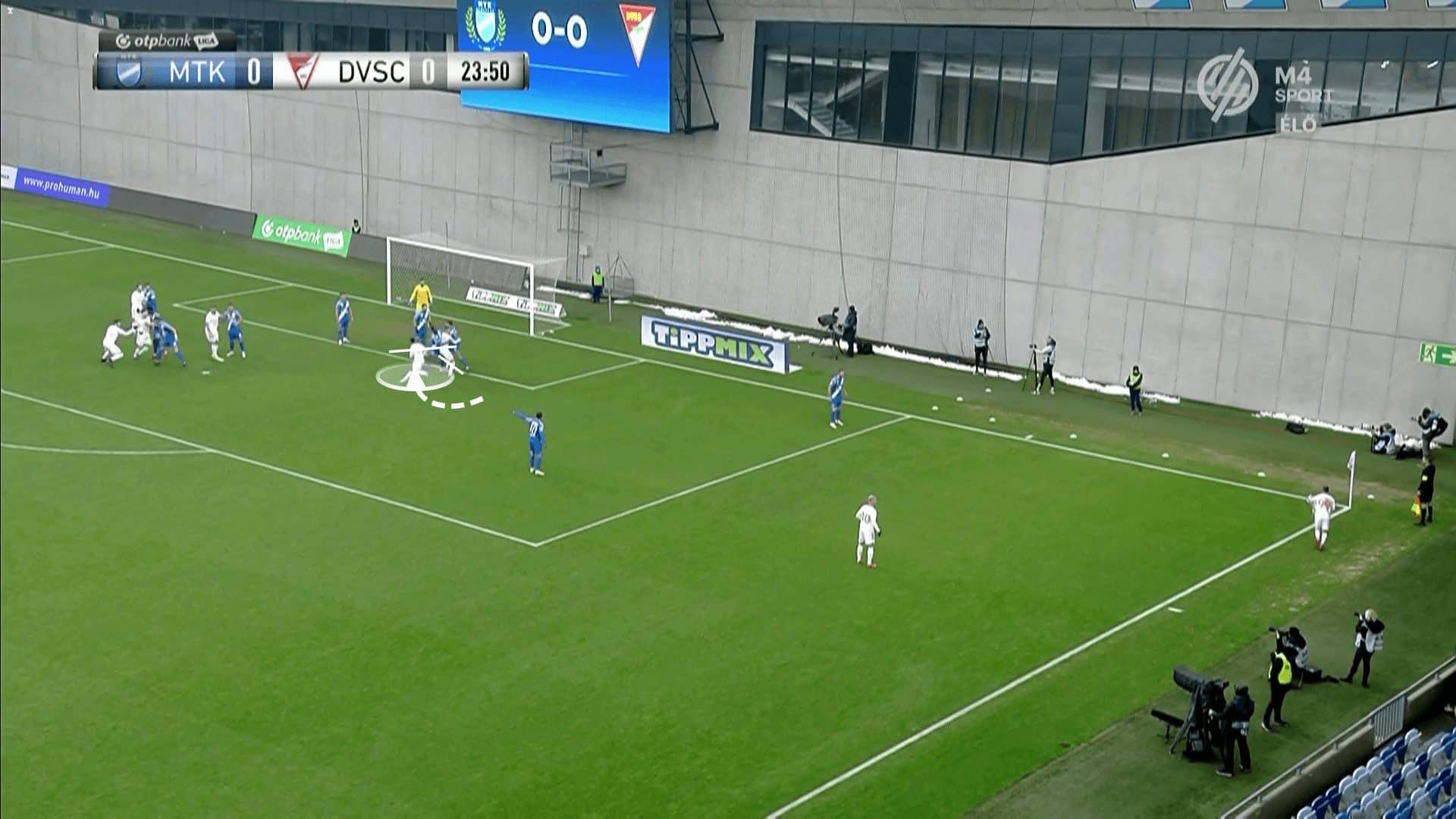

Pictured below, the original screen-setter has a clear path to the zonal defender to block him from intercepting the cross. The ball can now safely reach the near edge of the six-yard box. Due to the complexion of this method, the timing hasn’t been perfect yet, meaning that the movement wasn’t successful on this occasion. However, with more practice and experience in knowing when to make the movements and set the screens, this will make Debreceni’s screens impossible to stop.

Areas for Improvement

While Debreceni have shown immense potential from set-pieces, the end product hasn’t been good enough. No goals have been scored from over 100 corner kicks, where plenty of clear chances have been created. While some of this is down to human mistakes and poor finishing, I believe more could be done to increase their probability of scoring from corner kicks.

Firstly, it’s important to remember that Debreceni usually attacks the box with six players. This means that there is a strong attacking presence during the second phase. While the headed chance on goal may be difficult to execute, it could be worth playing the extra pass rather than a direct shot on goal. After the first contact is made from corners, it is common for defenders to lose track of their markers whilst watching the ball. In those moments, a header across the face of the goal to the back post could lead to an even easier chance on goal.

Of course, there is more room for error with an extra step in between the corner and the shot on goal, but the potential of an open goal from within three yards or so is worth taking the risk for. At the back post, we can see the defensive players with their backs to the goal, meaning they could potentially be caught on their heels and unable to recover the space that the ball is played into.

A principle that I believe is important for the majority of corners is to immobilize the nearest zonal defenders. Even when attacking the back post, preventing the nearest zonal defender from clearing the ball will ensure that the ball stays in the final third, where chances can be created during the second phase. Several of Debreceni’s well-worked corner routines have been unsuccessful following an under-hit corner where the player has managed to clear the ball out of play or into the middle third.

Similarly to the point above, goalkeepers have proven to be Debreceni’s biggest problem for set plays. It is not a problem for the attackers to lose track of their markers, but it almost feels like Debreceni have forgotten who the best defender during corner kicks is: the goalkeeper. Anytime the ball is crossed into the six-yard box, or sometimes into the back post, the goalkeeper has been able to rush off their line to either clear or claim the ball.

Setting a screen or two on the goalkeeper would prevent him from being able to do so, ensuring that the battle is left between the attackers and defenders, which the attackers have been easily winning thus far against almost every opposition. As seen in the example below, even though the attacker has found space in the six-yard box unmarked, he is unable to get to the ball as the goalkeeper beats him to it. The goalkeeper is the best defender on the pitch, with the biggest and tallest reach, and should, therefore, be the priority to be taken out of the contest.

Summary

This set-piece analysis has described why Debreceni are one of the best set-piece sides in the world. Many teams have attempted the use of screens, but the strategic placement of these screens is unlike almost anything else seen in Europe.

With the intended target area pre-determined, every player knows their role, so they can avoid two players making the same movement, treading on each other’s toes. Screens are only set on the defenders closest to the target area and on the marker of the attacker, whose role is to attack the target area. These two steps are the most important to a successful corner kick, yet practised by so few teams around the world. It’s impossible to set a screen on every defender, so Debreceni’s efficient placement of these screens is extremely refreshing to watch.

Most teams focus on one or the other, where, for example, a particular zonal defender is screened, but instead of also using screens for the intended attacker, two or three attackers are moving into the free zone, all tracked by their markers. In other cases, teams use screens for man-markers of attackers but leave zonal defenders alone, allowing them to attack the ball quickly.

Debreceni’s use of screens isn’t extremely complicated but instead shows signs of excellent planning and clarity amongst the staff and players.

Furthermore, the introduction of screens for screen-setters is something I haven’t experienced before, and a new way of increasing the efficiency of screens used, which hopefully will be more common in the future. The added layer of mind games causes chaos for defenders and is incredibly interesting to witness.

Finally, I believe Debreceni could increase the efficiency through the use of consistent screens on the goalkeeper and near zonal defender, not only to increase their chance of making the first contact from corners by preventing the defence from dominating their six-yard box but also to increase the likelihood of creating chances during the second phase, following unsuccessful routines. Some improvements in the timing of the runs and screens will also help increase efficiency, but this should come following the consistent practice of these routines.

Comments